ABSTRACT

Can policy entrepreneurship training affect policy entrepreneurship behavior among street-level bureaucrats? The current research aims to expand our understanding of how and when street-level bureaucrats might use entrepreneurial strategies to directly influence policy design. We suggest that managers and decision makers can increase street-level bureaucrats’ willingness and ability to act as policy entrepreneurs through specific training. To test this argument, we conducted a randomized field experiment with 158 nurses in a community-based network of maternal and child healthcare clinics in Israel. Our findings suggest that policy entrepreneurship training has a significant positive effect on street-level policy entrepreneurship behavior. We also find that it reduces the need of street level bureaucrats to have policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy in order to engage in policy entrepreneurship behavior. We discuss our findings in detail, proposing new avenues in theory and practice.

Introduction

Promoting informed policy making is important for improving the efficacy and responsiveness of government (Jones & Baumgartner, Citation2012; Workman, Citation2015; Workman et al., Citation2009). Inaccurate or partial information, leaving important dimensions of problems unattended, or poor implementation can lead to policy failures and inconsistency in governance outcomes (Jones & Baumgartner, Citation2005). Recent research underscores the importance of bureaucracies in policy making, and specifically their role in providing feedback on existing policies, helping in the detection of problems, and proposing possible solutions for the design of new policies (Workman, Citation2015). This approach joins a stream of work (e.g., Peters & Pierre, Citation2004) challenging the classic top-down approach that calls for a clear dichotomy between politics and administration (Wilson, Citation1887, p. 210).

In a quest to explain policy change, John Kingdon’s (Citation1984) influential work considers the role of the individual in shaping the policy process. His model is based on three distinct, yet complementary processes or streams in policymaking: the problem, the policy and the politics. Processes related to problems seek to identify those requiring the greatest attention. Processes related to policies present possible solutions to these problems. Indeed, many times it is the solution that searches for a problem. Finally, processes related to politics deal with the political atmosphere in the policy community and the national mood (Zahariadis, Citation2008). Thus, it is the uniting of these streams at a given time and in a given context that allows a particular issue to be turned into a policy. Given a window of opportunity (a limited time frame for action), policy entrepreneurs play a key role in connecting the streams by linking the problem and the solution. They are skilled and resourceful actors who unite the three streams together – problems, policies and politics – during open windows of opportunity (Ackrill et al., Citation2013). This process may explain why the literature on policy entrepreneurs has focused mainly on high-level decision makers and has rarely dealt with street level bureaucrats (Frisch-Aviram et al., Citation2018).

Whereas previous work on street-level bureaucrats focused on their involvement in the policy implementation stage (Arnold, Citation2015), when a policy already exists, recent studies have provided examples of cases in which street-level bureaucrats not only shaped policy by deciding how to implement it, but also tried to change the formulation of the policy (Cohen, Citationin press; Frisch-Aviram et al., Citation2018). They coined the phrase ‘street-level policy entrepreneurship’ to describe this phenomenon (Lavee & Cohen, Citation2019). The main challenge of street-level policy entrepreneurs is that they are ranked low in the organizational hierarchy, and thus, in most cases, they do not possess the formal authority or justification to engage in policy design. Moreover, they have heavy workloads, are tasked with realizing numerous policy objectives and usually have insufficient resources (Tummers et al., Citation2009). However, their low position in the organizational pyramid can be an advantage, as they have an intimate knowledge of the field, interact with different groups and have professional expertise.

For these reasons, scholars investigating street-level bureaucrats such as nurses, teachers and social workers have recently called for the expansion of their role in policy making from the formulation stage up through implementation, evaluation, and reform (Cohen, Citationin press; Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2013). Using the metaphor of knowledge flow, street-level bureaucrats are asked to evaluate and give feedback on the successes and limitations of the policies they are asked to implement. By doing so, they help bridge the gap between policy implementation and policy reform (on the policy cycle, see Howlett et al., Citation2009).

If indeed street-level policy entrepreneurship is an important part of policy making (Arnold, Citation2015; Cohen, Citationin press; Lavee & Cohen, Citation2019), public organizations should invest in training in this area. The effect of entrepreneurship training on entrepreneurship intentions is the focus of recent research in the literature on business (Fayolle & Liñán, Citation2014) and social entrepreneurship (Hockerts, Citation2018). However, these studies focus mainly on intentions, not on the effect of training on actual behavior. Mintrom (Citation2000) suggests that policy entrepreneurs are not a small number of heroic figures, but rather can be found among many actors in the policy domain, implying that entrepreneurship can be taught (Fayolle & Liñán, Citation2014).

In this paper we tested how policy entrepreneurship training affects the entrepreneurial behavior of street-level bureaucrats. In doing so, we contribute to an emerging body of work showing that training is a critical soft tool that can be used by public managers to increase policy entrepreneurship among these frontline workers (Jakobsen et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the main research question we address is: What impact does the policy entrepreneurship training of street-level bureaucrats have on the extent of their policy entrepreneurship?

This study is a first-of-its-kind attempt to map and analyze the training of street-level policy entrepreneurship. In doing so, it demonstrates that training in this area is effective and underscores the role that individuals can and do play in bottom-up policy making. It also shows how an abstract policy theory can be concretely translated into a field experiment that produces real-world insights. Our focus on training street-level bureaucrats to act as policy entrepreneurs introduces a potentially valuable theoretical lens for understanding the benefits of training in the public sector as a whole, and in street-level work in particular (Jakobsen et al., Citation2018).

Methodologically, to ensure the generalizability of our findings, we utilized a randomized field experiment with 158 nurses in the community-based network of maternal and child healthcare clinics in Israel. In doing so, we address calls to strengthen the internal and external validity of public policy research by utilizing experimental designs in field settings (Shadish et al., Citation2002).

Lessons from the literature on entrepreneurship education

Within the public administration literature there is little research that addresses the on-the-job training of public personnel in general, and specifically entrepreneurship training (Jakobsen et al., Citation2018). In policy research, this topic is even more rare. However, studies in business management have extensively investigated the effect of entrepreneurship education and training on workers and students in the private sector and underscored the positive impact of entrepreneurship education, reflecting a widespread belief in the positive impact of such training on entrepreneurship intentions (Tkachev & Kolvereid, Citation1999).

The theory of planned behavior

We use the theory of planned behavior as the basic theory for the proposed model. According to this well-known theory, the strength of an intention is an immediate antecedent of behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991, Citation2011). This theory has been widely used in the private entrepreneurship literature (Kolvereid, Citation1996). A behavioral intention is a person’s plan to engage in a behavior, encompassing both direction (to do X vs. not to do X) and intensity (the time and effort the person is prepared to invest in doing X) (Ajzen, Citation1991). The actual behavior comprises the action steps that are taken.

Intentions are shaped by attitudes towards the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, Citation1991). Attitudes are determined by beliefs that a certain behavior will lead to a favorable outcome. Subjective norms are determined by the beliefs of important others about a certain behavior and the degree to which one tends to comply with these beliefs. Finally, perceived behavioral control reflects perceptions regarding the ease or difficulty of initiating a behavior, past experiences, and the availability of resources and opportunities.

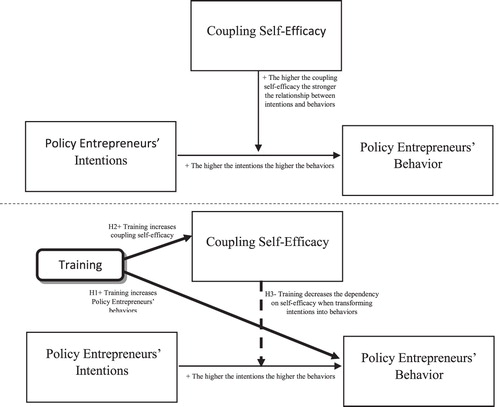

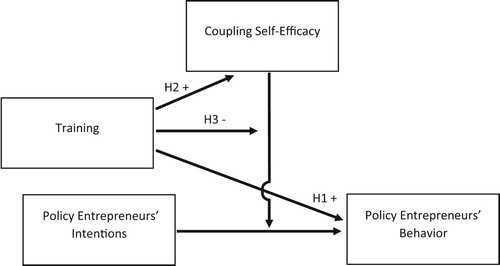

The model proposed here focuses on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy as an antecedent of street-level policy entrepreneurship behavior. Policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy is defined as one’s perceived ability to act as a policy entrepreneur (Zahariadis, Citation2008). The model proposes that training will affect both behavioral control in the form of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy and the behavior itself. Therefore, the model focuses on the moderating role of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy on the relationship between policy entrepreneurship intentions and actual behavior.

Research has shown that practical guidance and making specific plans increase the likelihood of behavioral change (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, Citation2009). Within the realm of policy entrepreneurship, training can facilitate this process by helping people plan specific aspects of entrepreneurial behavior, such as forming coalitions; working with teams; networking within policy circles and at different stages of the policy cycle; interacting effectively with other players in the policy arena; and leading by example (Mintrom & Norman, Citation2009). In terms of practical guidance, training can influence behavior by providing information about how to access resources (Van Gelderen et al., Citation2008) and strengthening trainees’ knowledge about policy problems, policy solutions, and political actors, so that they are positioned to recognize and seize on a window of opportunity when one opens (Kingdon, Citation1984). We therefore hypothesize that:

H1: Policy entrepreneurship training increases policy entrepreneurial behavior among street-level bureaucrats.

Figure 1. Theoretical model- The indirect effect of training and policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy on the relationship between policy entrepreneurs’ intentions and behavior.

Besides the practical help and guidance provided by street-level policy entrepreneurship training, such training can improve trainees’ confidence in their abilities by, for example, providing positive experiences in entrepreneurship-related tasks (Kuehn, Citation2008) or by using modeling. As such, training can enhance policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy, improving people’s sense of their capacity to link Kingdon’s three streams (problems, policies and politics). Thus, we posit that:

H2: Policy entrepreneurship training increases policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy among street-level bureaucrats.

Building on this rationale, we assume that training street-level bureaucrats in policy entrepreneurship reduces their dependency on their initial level of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. In other words, practical hands-on training can compensate for an initial lack of self-efficacy. We therefore hypothesize that:

H3: Policy entrepreneurship training weakens the dependency on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy for turning policy entrepreneurship intentions into actual behavior.

compares the expected effects of training on trained and untrained street-level bureaucrats’ intentions, self-efficacy, and behaviors.

Research design

Despite the growing body of research on entrepreneurship education, the research to date has several limitations. The most prominent theoretical limitation is the focus on how training affects intentions, while neglecting the effect of training on actual behavior (Kautonen et al., Citation2015). This omission is important because we know that, while intentions inevitably precede behavior, behavior does not inevitably follow intentions. It is therefore not enough to focus the training on intentions. It must revolve around changing actual behavior and improving the trainees’ self-efficacy.

We conducted a randomized field experiment among street-level bureaucrats to measure the effect of policy entrepreneurship training on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy and policy entrepreneurship behavior. Participants were 158 nurses working in a public community-based network of maternal and child healthcare clinics in Israel run by the Israeli Health Ministry.

Experimental setting

Israel is a child-oriented society, where children comprise 33 per cent of the population (demographically, 70 per cent of Israel’s children are Jewish, 26 per cent are Arab, and 4 per cent come from other ethnic backgrounds) (Rubin et al., Citation2017). Since the creation of the Israeli state, this orientation has translated into a policy in which every child in Israel is entitled to comprehensive preventive and curative healthcare services. These services are guaranteed by the National Health Insurance Law and provided in a community-based network of maternal and child healthcare clinics known as Tipat Chalav (literal translation: ‘A Drop of Milk’). These nationwide, neighborhood-based centers provide free healthcare services for pregnant women, babies and children up to 6 years old and their families (Rubin et al., Citation2017). Ninety-five percent of all babies in Israel receive preventive health services in the clinics (Kagan et al., Citation2017). Care is provided according to national guidelines produced by Israel’s public health services and includes the prevention of infectious diseases through vaccinations; early identification of developmental problems through routine checkups; the prevention of health problems in the community through health education and health promotion; and breastfeeding support and screening for postpartum depression (Rubin et al., Citation2017). Qualified public health nurses are the primary care providers in the clinics, with support from pediatricians. These nurses are all women from diverse backgrounds. The policy of free service has led to important social and health outcomes. For example, Israel boasts high immunization rates among both Arab and Jewish children despite the absence of mandatory immunization laws.

We chose this community-based network of maternal and child healthcare clinics as the setting for our random field experiment for three main reasons. First, public health provides a good example of a domain where policy making typically takes place at the national or societal level, but services are provided at the street level (Grunseit et al., Citation2018). Second, the clinics are at a critical policy juncture. Since 2007, there has been a move to privatize these services and transfer control to local municipalities and large health insurers (Knesset Report, Citation2007). This trend places pressure on the clinics to innovate and become more flexible. Third, all the nurses are women, and women are in general less active in entrepreneurship than men (Van Ewijk & Belghiti-Mahut, Citation2019). Therefore, establishing that training in policy entrepreneurship increases participants’ involvement in policy entrepreneurship behavior would be a welcome finding for both the system and the individuals involved in it.

The experimental design

Our objective was to design an intervention tool to evaluate the effects of a policy entrepreneurship training program on policy entrepreneurship behavior and policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. With that goal in mind, we contacted the Israeli Health Ministry and offered a free 8-hour active policy entrepreneurship training program for nurses involved in preventive health. To assess the impact of our training, we randomized the recruits for the training program. Of the 158 nurses, 130 were included in the experimental group and 28 in the control group. We agreed to this division because the Israeli Health Ministry invested extensive resources in the program. In return, they wanted 80 per cent of the participants to be trained. While unequal group sizes in randomization is a common weakness of field experiments, it is still a limitation and concern. Properly reporting the randomization process helps avoid misinterpretation (Schulz & Grimes, Citation2005).

The control group did not receive any treatment. The experimental group was divided into seven groups of 17–21 nurses for the training sessions. Two of the groups received training in January 2019 and the other five in February 2019. All sessions were led by the same training coordinator, an organizational psychologist working for a professional development company that specializes in the public sector. The coordinator was blind to the specific research hypotheses. All training sessions used the same curriculum and materials.

The policy entrepreneurship training intervention

We developed the curriculum for the training using several insights from the policy entrepreneurship literature. First, Zahariadis (Citation2008) noted that the ‘analysis of entrepreneurial activity is normally divided in two parts: attributes and strategies’ (p. 521). Second, in a recent systematic review, Frisch-Aviram et al. (Citation2020) identified and classified policy entrepreneurship strategies. Their analysis confirmed Kingdon’s (Citation1984) and Mintrom and Norman’s (Citation2009) claim that networking and team building are the strategies that policy entrepreneurs most rely on to form diverse teams with many actors. They also identified three key elements of the policy entrepreneurship strategy – the power of persuasion, ability to build trust, and social acuity.

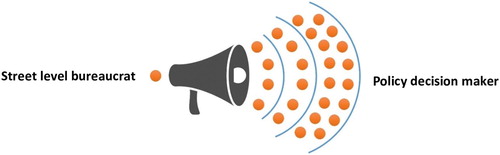

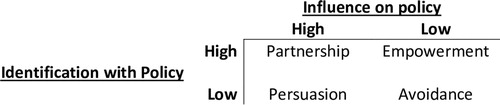

The workshop was divided into four two-hour sessions, each covering one unit of the training. Sessions took place on a university campus. In the first unit, the only theoretical unit, the training coordinator outlined the policy circle (Howlett et al., Citation2009), and emphasized the role of street-level bureaucrats in closing the policy circle by evaluating implemented policies using the street-level policy entrepreneurship literature. The second unit dealt with a policy problem from the nurses’ everyday work (Rochefort & Cobb, Citation1993). The third unit covered the ‘amplifier effect’ (see ). Using this metaphor, we demonstrated how small steps could lead to a major policy change if constructed well. In addition, we emphasized the effect of networking in promoting a policy change (Cairney, Citation2018). The trainees, with guidance from the coordinator, also identified the stakeholders (Carlsson, Citation2000) involved in the policy problem and ranked them in an influence and involvement matrix (). They then devised a practical strategy for approaching each of the stakeholders.

Finally, in the fourth unit, the trainees planned five practical, small-scale actions for promoting their policy ideas. They learned how to formulate SMART (Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, and Time-bound) requests for appropriate stakeholders. We hoped that, armed with these tools, the nurses would feel empowered to engage in entrepreneurship behaviors, and would be less dependent on their initial level of self-efficacy.

The class sessions were organized to maximize hands-on learning activities. At the start of each session, the coordinator lectured for approximately 20 min. During the remainder of the class (70 min), trainees worked one-on-one with assigned partners to put the lesson into practice, with guidance from the coordinator. We adopted this approach because training has been shown to be more effective when multiple instructional strategies – information, demonstration and practice – are used together (Bandura, Citation1977).

Following Hauser et al. (Citation2018), we ensured effective manipulation using several manipulation checks. Manipulation checks are tests of validity that ensure that the intended effects of the operations used to manipulate the variables are successfully tied directly with the concept the experimenter has in mind. Put differently, they check the success of the experimental manipulations. First, in order to check attention, we conducted presence tracking and forbad smartphone use during the sessions. Our goal was to ensure the nurses’ active participation and attentiveness, not just their presence in the training session. Our tracking revealed that 98 per cent of the participants attended all of the sessions. In addition, 70 per cent of them were verbally involved with the coordinator and their colleagues. Those who were less active in class were encouraged to participate. Second, in order to check the effectiveness of the manipulation we assessed the nurses’ completions of the assignments. We evaluated their success in defining the problem, filling out the matrix and asking SMART questions. Eighty-five percent of the participants accomplished their assignments in a satisfactory manner. We provided additional explanations, guidance and examples to the nurses who were less successful. Ultimately, 70 per cent of the students said they were satisfied or very satisfied with the course.

Pre and post data collection

All participants filled out two questionnaires, one before and one after the intervention. For the experimental group, the pre-intervention (T1) questionnaire was distributed in paper format at the start of the training, and the post-intervention (T2) questionnaire was distributed via email one month after the training ended. Participants were assured that their responses would be handled confidentially and would be used only in aggregate form without identifying personal information. All participants were assigned a recognition code that allowed us to match the data from the two surveys. The two questionnaires were identical, except that demographic information was collected only at T1.

Among the 158 nurses who participated at T1, 117 returned T2 questionnaires. Fourteen of these were discarded, as they did not include a valid recognition code. The final sample was thus 103 participants, of whom 19 were in the control group and 84 in the experimental group.

Measures

Answers to all measures were provided on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not agree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Policy entrepreneurship behavior

Following Ajzen (Citation2011), we asked respondents to what degree they had engaged in eight policy entrepreneurship behaviors derived from policy entrepreneurship theory (Frisch-Aviram et al., Citation2020; Mintrom & Norman, Citation2009). Items were framed using the phrase ‘In the past, I have … ’.

Policy entrepreneurship intentions

Following Ajzen (Citation1991), who argued that the predictor (intention) and the criterion (behavior) should be measured at the same level of specificity (see also Kautonen et al., Citation2015), we used the same list of activities and tasks to assess policy entrepreneur behavior for the intentions scale. Respondents were asked to indicate their intentions to engage in these activities and tasks.

Policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy

Captures the extent to which respondents felt confident that they had the skills and abilities to perform policy entrepreneurship tasks. Following Zhao et al. (Citation2005), we measured self-efficacy with regard to the specific policy entrepreneurship tasks described above. Items were framed using the phrase ‘I am able to … .’.

Control variables

To ensure sufficient internal validity, we included a number of micro- and macro-level control variables that are considered important in the public administration literature: age, which might affect risk-taking and entrepreneurship and ethnicity, which might have implications for street-level bureaucracy and public policy; education and the size of their specific unit in the organization.

Statistical analysis

Using the software package IBM SPSS Statistics 23, we first conducted an exploratory factor analysis to ensure the validity of the scales and the uniqueness of the constructs investigated. We then tested H1 and H2 by comparing the means of the data using t-tests of paired samples. In order to test H3 we first created panel data by coding the observations according to time (T1 = 0; T2 = 1) and group (control group = 0, experimental group = 1). This data yielded 274 observations. We then used the regression-based bootstrapping approach described in Hayes (Citation2015) PROCESS macro. It is recommended and preferred over other tests, because it is more powerful and based on realistic assumptions. We used two models #1, one for the control and one for the experimental group.

Findings

Reliability and validity

Self-reported measures are generally susceptible to common method bias. To reduce this effect, we assured respondents that their data would remain anonymous, checked that they fully understood the terms, and explained the importance of providing accurate answers. We also performed several statistical procedures to detect potential bias.Footnote1 Our findings demonstrate that there is diversity in the data despite the common method used.

presents the results for the exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotated factor loadings. All items loaded only on the expected four-factor model.Footnote2 For our reliability tests, we examined internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. The usual threshold is .7 for developed measures (Liñán & Chen, Citation2009). In our constructs, the values ranged from .80 to .94. The Cronbach’s alpha and confirmatory factor analysis results ensure that our measurement tools are reliable and valid. We can now turn to our findings.

Table 1. Survey questions – before and after the intervention (with exploratory factor analysis loadings and Cronbach’s α).

presents the Pearson’s coefficient correlations among the variables by condition, at T1 and T2. The zero-order correlations between these measures indicate the general relationships between the main research variables. Note that for the sample as a whole, many of the research variables at T1 were significantly and positively correlated with the variables at T2 (r = .293 to .813, p < .01). These findings were particularly true regarding the pre- and post correlations of intentions, self-efficacy and behaviors (marked with a gray background; r = .371 to .583, p < .001), which revealed consistency but not derivativeness.

Table 2. Pearson’s coefficient correlations by condition, at T1 and T2.

Testing the effect of training on policy entrepreneurs’ behavior and policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy (H1, H2)

An independent sample t-test revealed no significant differences between the experimental and control groups at the baseline. Thus, we can conclude that the groups were indeed randomized.

Bootstrap paired-sample t-tests were conducted in order to compare the research variables before (T1) and after the training (T2) (see ). The results showed a significant difference (95 per cent [LLCI = −.790, ULCI = −.399], p < .001) between the policy entrepreneurship behavior of the participants in the intervention group before the training (mean = 1.87, SD = .94) and a month after the training was completed (mean = 2.46, SD = 1.05). This finding suggests that the intervention had a positive effect on the participants’ policy entrepreneurship behavior, confirming H1.

Table 3. Bootstrap t-tests of paired samples for the experimental group vs. control group pre- and post-intervention.

The results showed slightly higher levels of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy for the intervention group at T1 (M = 3.03, SD = .83) than at T2 (M = 2.96, SD = .90), though this difference was insignificant (95 per cent [LLCI = −.138, ULCI = .278], p = NS). Therefore, the intervention had no direct effect on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy, and H2 must be rejected.

Interestingly, the results indicated that the standard deviations, which measured the dispersions of the variables, uniformly grew larger between T1 and T2 for the experimental group but uniformly became smaller between T1 and T2 for the control group. This finding might suggest that the training helped the nurses and affected their behaviors in various ways, creating variety in their styles of policy entrepreneurship. In the case of the control group, it might be the case that filling out the questionnaires twice created some shared expectations that increased uniformity of thought.

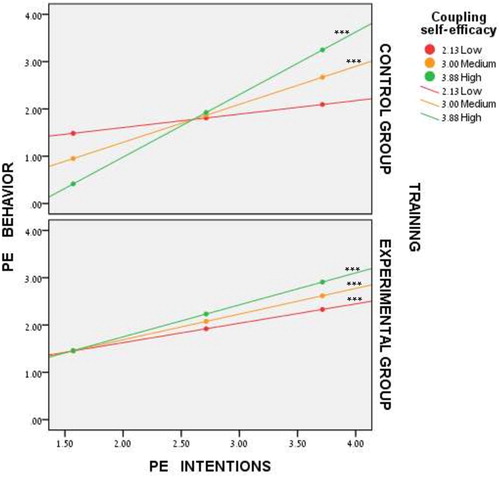

The weakening effect of policy entrepreneurship training on the dependency on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy (H3)

H2 was rejected, indicating that the training had no direct effect on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. Nevertheless, we still tried to determine whether the training had any other effect on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. To test H3, the weakening effect of policy entrepreneurship training on the dependency on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy, we used Hayes (Citation2015) PROCESS model #1 twice, once for the control group and once for the experimental group. In both models, the interaction between intentions and self-efficacy was positive and significant (control: b = .549, p < .01; 95 per cent [LLCI = .243, ULCI = .864]; experiment: b = .149, p < .01; 95 per cent [LLCI = .051, ULCI = .247]), indicating that for both groups, participants with higher levels of self-efficacy were generally more able to turn strong intentions into increased policy entrepreneurship behavior. However, there was a significant positive relationship between intentions and actual policy entrepreneurship behaviors only in the experimental condition for the participants who had low levels of self-efficacy (b = .407, p < .001; 95 per cent [LLCI = .228, ULCI = .587]). In other words, the more the participant had strong intentions, the more likely he/she was to turn them into policy entrepreneurship behaviors (b = .407, p < .001; 95 per cent [LLCI = .228, ULCI = .587]). In contrast, in the control group such a relationship was not found. For the participants who had low levels of self-efficacy there was no significant relationship between intentions and policy entrepreneurship behaviors (b = .178, p = NS; 95 per cent [LLCI = −.285, ULCI = .642]). These findings confirm H3 ().Footnote3

Table 4. Moderation of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy on the relationship between policy entrepreneurs’ intentions and behavior (H3).

plots the conditional effects (simple slopes) of the training condition for the values of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. As the figure shows, the training weakened the dependency on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. Only within the experimental group did the participants report that the stronger their policy entrepreneurship intentions, the more they engaged in entrepreneurship behaviors. This result was true regardless of their level of self-efficacy. After the training, even trainees with low levels of self-efficacy indicated that they had greater intentions of engaging in entrepreneurship behaviors. Within the control group, only those who indicated that they had medium to high levels of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy initially reported greater intentions of engaging in entrepreneurship behaviors.

Discussion and conclusion

This study explores the effect of policy entrepreneurship training on street-level policy entrepreneurship behavior. We found that a training intervention significantly increased policy entrepreneurship behavior among those who were trained. In contrast, those in the control group exhibited no significant change in their entrepreneurship behavior.

Interestingly, we found no direct effect of the training on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. This result is surprising because in the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991), self-efficacy is considered an antecedent of intentions and behavior. Here, we found a behavioral change without an increase in perceived capabilities. There is a longstanding debate in psychology about whether cognitive processes produce behavior, or vice versa, whether performance-based behavior creates psychological change (Bandura, Citation1977). According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1977), self-efficacy can be increased through enactive mastery – that is, the experience of completing a challenge successfully. Similarly, Vancouver et al. (Citation2001) argued that success and achievement might create increased self-efficacy over time. Therefore, it is possible that the perceptions and behaviors we measured at T2 – only a month after the training intervention – could represent only the start of a long process, in which small successes in policy entrepreneurship behavior among our training group might lead to stronger feelings of capability in the long run.

To better understand the significant change we found in the behavior of the training group, we also used a two-way interaction analysis to test whether the intervention would affect policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy’s moderation of the relationship between intentions and behaviors. We posited (H3) that policy entrepreneurship training would reduce the dependency on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy in the interaction between policy entrepreneurship intentions and the participants’ actual behavior. Indeed, we found that policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy moderated this relationship in the control group, but not among those who participated in the training intervention. This means that among trained street-level bureaucrats, transforming intentions into behavior does not depend on policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. More importantly, the training compensated for lower levels of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. In other words, no matter what degree of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy participants had before the training, after the training they were able to turn their intentions into behavior. This finding correlates with current social psychology research on ways to minimize the gap between intentions and behavior through practical interventions (Sheeran & Webb, Citation2016). Its practical implication is that the training is the most effective with street-level bureaucrats with low levels of self-efficacy and should be aimed at them.

There are several theoretical implications of our findings. First, our findings add to the public policy literature by discussing and modeling street-level policy making. They extend Kingdon’s multiple streams approach (1984), which is centered on the role of the individual in policy making. While Kingdom used a more top-down approach of policy making, we focus on how low-level policy implementers may also affect policy formation.

Street-level policy entrepreneurship improves the knowledge flow and gathering of information, an important input into policy processes (Fyall, Citation2016). Indeed, the term ‘knowledge flow’ is often used as a metaphor to describe the process of gathering information from different stakeholders, which increases the sources utilized and provides a better overview of the problem and possible solutions (Grant, Citation1996; Gupta & Govindarajan, Citation2000). We propose a way to overcome the obstacles facing street-level bureaucrats who do not possess the formal authority or justification to engage in policy design, but have valuable and intimate knowledge of their field, extensive experience interfacing with different groups and professional expertise. Through street-level policy entrepreneurship, they can put these advantages to work in improving the design of policy.

Second, our study extends the public administration literature by highlighting the role of policy entrepreneurship training as a means of responding to street-level bureaucrats’ alienation from the policies they are expected to implement (Tummers et al., Citation2009). The literature has noted that this sense of being psychologically disconnected from one’s work responsibilities has a range of negative consequences for both organizations and employees. On the organizational level, it can reduce the effectiveness of implemented policies or lead to divergence between organizational policies and those implemented on the ground. On the personal level, it can lead to stress, burnout, or decisions to leave the organization (Gofen, Citation2013). The intervention suggested here sheds light on how training can produce positive outcomes from street-level bureaucrats’ alienation, by encouraging their involvement in policy making. It also points to training as a soft tool that public managers can use to enhance skills such as entrepreneurship and innovation (Jakobsen et al., Citation2018). Moreover, it suggests that training can bypass low levels of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy. It can provide the tools needed for street-level policy entrepreneurship even to those who feel less capable of engaging in such behaviors. Thus, the training does not need to improve their sense of self-efficacy in order to make them street-level policy entrepreneurs.

In the public sector, Koski and Workman (Citation2018) recently pointed out that the engines of information processing in policy systems are sub-governments. These units emerge through the delegation of authority to smaller groups in order to focus attention on specific problems. We argue that frontline bureaucrats, those who interact daily with the public, are important players in these smaller groups, comprising an underutilized resource for policy feedback, problem detection, and possible solutions for the design of new policies (Lipsky, Citation1980). It is therefore crucial to answer the question raised in this paper. Future questions on policy entrepreneurship training that should be addressed are: When compared with training for professional ethics, organizational values and policies, how important is training for policy entrepreneurship? What are the costs and benefits of entrepreneurial street-level bureaucrats? If entrepreneurship is about new and out-of-the-box thinking, will training hurt or help? How does training compare with other interventions like competition and incentives? Moreover, future research should consider the possibility that there could be malicious, destructive policy entrepreneurism, that may not advance societal best interests, and for whom training in entrepreneurism would also be socially destructive.

Third, the field experiment research design introduced here has advantages over quasi-experimental laboratory studies in that our research setting and sample, nurses in a working environment, match the target setting and potential users of the interventions (Dipboye & Flanagan, Citation1979). Policy theorists can, and should, engage in experimental fieldwork to draw clearer causal inferences and determine the generalizability policy theory. Future research can also build on our study by exploring possible conditions of the reported intervention effects, including the effects of the organizational context. It can address the following questions: Is policy entrepreneurship training effective in different types of street-level organizations? How do different policy entrepreneurship training interventions affect street-level policy entrepreneurship? What are the effects of continued policy entrepreneurship training interventions on street-level policy entrepreneurship?

Finally, our study has practical implications. Street-level bureaucrats may have information that public policy bodies can use in their struggle to innovate and respond to thorny policy problems (Koski & Workman, Citation2018). Our findings point to a rather easily implementable intervention to improve street-level bureaucrats’ involvement in policy making.

Despite the important theoretical and practical implications of our findings, they should be interpreted considering a main limitation of our study which is that due to the Israeli Health Ministry’s confidentiality policy, we had to use self-reported questionnaires for data collection. Although we employed several procedural and statistical methods for controlling and minimizing common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), we cannot completely rule out its possibility. Future studies that combine our measures with supervisor ratings, peer evaluations, or other forms of external measurement may be helpful in determining the robustness of our study’s results. Using qualitative evidence about the trainees’ behavioral changes could also add to the validity of the findings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Neomi Frisch-Aviram

Neomi Frisch-Aviram, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the department of Public Administration & Policy, University of Haifa, Israel.

Itai Beeri

Itai Beeri is a senior lecturer (associate professor) and the head of the department of Public Administration & Policy, University of Haifa, Israel.

Nissim Cohen

Nissim (Nessi) Cohen is the head of The Center for Public Management and Policy (CPMP) at the University of Haifa in Israel.

Notes

1 First, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test, loading 29 self-reported items on one factor and using exploratory principal axis factoring without rotation. One factor explained only 40.3 per cent of the variance; hence, it did not indicate potential common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Next, we ran a single-factor model based on confirmatory factor analysis. The model had an unacceptable fit (Chi2 = 1050.4, df = 371, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.088, NNFI = 0.837).

2 The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was high and significant (KMO = .928, p < .001) and the total variance explained was 69.5 per cent.

3 In addition, in order to test H3, we also used Hayes (Citation2015) PROCESS model #3. The model proved significant and revealed that the training weakened the effect of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy on the relationship between policy entrepreneurship intentions and behavior. The overall three-way interaction model indicated that for participants who received the training, higher levels of policy entrepreneurship self-efficacy were not a precondition for turning policy entrepreneurship intentions into actual behavior, and H3 was confirmed. These results are available upon request from the authors.

References

- Ackrill, R., Kay, A., & Zahariadis, N. (2013). Ambiguity, multiple streams, and EU policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(6), 871–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.781824

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology and Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- Arnold, G. (2015). Street-level policy entrepreneurship. Public Management Review, 17(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.806577

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Cairney, P. (2018). Three habits of successful policy entrepreneurs. Policy & Politics, 46(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230056771696

- Carlsson, L. (2000). Policy networks as collective action. Policy Studies Journal, 28(3), 502–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2000.tb02045.x

- Cohen, N. (in press). Policy entrepreneurship at the street level: Understanding the effect of the individual. Cambridge University Press.

- Dipboye, R. L., & Flanagan, M. F. (1979). Research settings in industrial and organizational psychology: Are findings in the field more generalizable than in the laboratory?. American Psychologist, 34(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.2.141

- Fayolle, A., & Liñán, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 663–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.024

- Frisch-Aviram, N., Cohen, N., & Beeri, I. (2018). Low-level bureaucrats, local government regimes and policy entrepreneurship. Policy Sciences, 51(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9296-y

- Frisch-Aviram, N., Cohen, N., & Beeri, I. (2020). Wind(ow) of change: A systematic review of policy entrepreneurship characteristics and strategies. Policy Studies Journal, 48(3), 612–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12339

- Fyall, R. (2016). The power of nonprofits: Mechanisms for nonprofit policy influence. Public Administration Review, 76(6), 938–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12550

- Gal, J., & Weiss-Gal, I. (2013). The ‘why’ and the ‘how’ of policy practice: An eight-country comparison. British Journal of Social Work, 45(4), 1083–1101. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct179

- Gofen, A. (2013). Mind the gap: Dimensions and influence of street-level divergence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(2), 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut037

- Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2009). Self-regulation of consumer decision making and behavior: The role of implementation intentions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(4), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.08.004

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171110

- Grunseit, A., Richards, J., & Merom, D. (2018). Running on a high: Parkrun and personal well-being. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4620-1

- Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge flows within multinational corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 21(4), 473–496. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200004)21:4<473::AID-SMJ84>3.0.CO;2-I

- Hauser, D. J., Ellsworth, P. C., & Gonzalez, R. (2018). Are manipulation checks necessary? Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00998

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Hockerts, K. (2018). The effect of experiential social entrepreneurship education on intention formation in students. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 9(3), 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1498377

- Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., & Perl, A. (2009). Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems (Vol. 3). Oxford University Press.

- Jakobsen, M., Jacobsen, C. B., & Serritzlew, S. (2018). Managing the behavior of public frontline employees through change-oriented training: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(4), 556–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy080

- Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2005). The politics of attention: How government prioritizes problems. University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2012). From there to here: Punctuated equilibrium to the general punctuation thesis to a theory of government information processing. Policy Studies Journal, 40(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00431.x

- Kagan, I., Shachaf, S., Rapaport, Z., Livne, T., & Madjar, B. (2017). Public health nurses in Israel: A case study on a quality improvement project of nurse’s work life. Public Health Nursing, 34(1), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12261

- Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12056

- Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little, Brown.

- Knesset Report. (2007). Maternal and child healthcare clinics in Israel: 2007–1997. https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/caee6d8d-f1f7-e411-80c8-00155d01107c/2_caee6d8d-f1f7-e411-80c8-00155d01107c_11_9581.pdf [in Hebrew].

- Kolvereid, L. (1996). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879602100104

- Koski, C., & Workman, S. (2018). Drawing practical lessons from punctuated equilibrium theory. Policy & Politics, 46(2), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230061413778

- Kuehn, K. W. (2008). Entrepreneurial intentions research: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 11, 87. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/jeevol112008.pdf

- Lavee, E., & Cohen, N. (2019). How street-level bureaucrats become policy entrepreneurs: The case of urban renewal. Governance, 32(3), 475–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12387

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Sage Foundation, 71.

- Mintrom, M. (2000). Policy entrepreneurs and school choice. Georgetown University Press.

- Mintrom, M., & Norman, P. (2009). Policy entrepreneurship and policy change. Policy Studies Journal, 37(4), 649–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2009.00329.x

- Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (Eds.) (2004). The politicization of the civil service in comparative perspective: A quest for control. Routledge.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Rochefort, D. A., & Cobb, R. W. (1993). Problem definition, agenda access, and policy choice. Policy Studies Journal, 21(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.1993.tb01453.x

- Rubin, L., Belmaker, I., Somekh, E., Urkin, J., Rudolf, M., Honovich, M., Bilenko, N., & Grossman, Z. (2017). Maternal and child health in Israel: Building lives. The Lancet, 389(10088), 2514–2530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30929-7

- Schulz, K. F., & Grimes, D. A. (2005). Sample size calculations in randomised trials: Mandatory and mystical. The Lancet, 365(9467), 1348–1353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61034-3

- Shadish, W., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

- Sheeran, P., & Silverman, M. (2003). Evaluation of three interventions to promote workplace health and safety: Evidence for the utility of implementation intentions. Social Science & Medicine, 56(10), 2153–2163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00220-4

- Sheeran, P., & Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention–behavior gap. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12265

- Tkachev, A., & Kolvereid, L. (1999). Self-employment intentions among Russian students. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 11(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/089856299283209

- Tummers, L., Bekkers, V., & Steijn, B. (2009). Policy alienation of public professionals: Application in a new public management context. Public Management Review, 11(5), 685–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030902798230

- Vancouver, J. B., Thompson, C. M., & Williams, A. A. (2001). The changing signs in the relationships among self-efficacy, personal goals, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.4.605

- Van Ewijk, A. R., & Belghiti-Mahut, S. (2019). Context, gender and entrepreneurial intentions: How entrepreneurship education changes the equation. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship.

- Van Gelderen, M., Brand, M., van Praag, M., Bodewes, W., Poutsma, E., & Van Gils, A. (2008). Explaining entrepreneurial intentions by means of the theory of planned behaviour. Career Development International, 13(6), 538–559. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810901688

- Wilson, W. (1887). The study of administration. Political Science Quarterly, 2(2), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/2139277

- Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychological Review, 114(4), 843–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.843

- Workman, S. (2015). The dynamics of bureaucracy in the US Government: How congress and federal agencies process information and solve problems. Cambridge University Press.

- Workman, S., Jones, B. D., & Jochim, A. E. (2009). Information processing and policy dynamics. Policy Studies Journal, 37(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00296.x

- Zahariadis, N. (2008). Ambiguity and choice in European public policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(4), 514–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760801996717

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1265