ABSTRACT

Prior literature points to the importance of party power and ideology for interest group-party contacts in the legislative arena. But interest groups do not often have ideologies – they are typically active in a small number of policy domains and there may be different parties that share more similar preferences across different policy areas. Therefore, we examine whether and how party power and proximity in policy preferences predict the existence of party-interest group ‘lobby routines’ in specific policy domains, using a novel survey of representative samples of interest groups in seven long-established democracies. We find that groups often form routines with different parties in different policy areas and that preference proximity on relevant policy dimensions is positively associated with having such area-specific lobby routines. However, the results also suggest that powerful parties are more likely allies and that the effect of policy proximity on routines is positively conditioned by power.

Introduction

Every day interest groups try to influence public decision-making in democracies all over the world. One way they may succeed, is by structured interaction with political parties, because parties directly make policy and have a high capacity to influence the behaviour of elected officials (Klüver, Citation2020). But even if scholars have long recognised the importance of interaction between parties and organised interests (Key, Citation1964; Schattschneider, Citation1948), we know relatively little about these topics (Allern, Hansen, Marshall, et al., Citation2020; Hojnacki et al., Citation2012).

Much of the lobbying literature has focused on why groups choose to interact with individual decision-makers (Austen-Smith & Wright, Citation1994; Baumgartner & Leech, Citation1996; Hojnacki & Kimball, Citation1998), while the literature on party-interest group relationships has concentrated on examining general organisational ties (Allern & Bale, Citation2017). It is only recently that scholars have begun to systematically theorise about and analyse less formal but still structured party-interest group interactions, across issues and institutions (e.g., Berkhout et al., Citation2019; Eichenberger & Mach, Citation2017; Koger et al., Citation2009; Marshall, Citation2015; Otjes & Rasmussen, Citation2017; Rasmussen & Lindeboom, Citation2013; Witko, Citation2009).

Our contribution is to examine what we call interest groups’ ‘lobby routines’ vis-à-vis political parties in different policy domains. Rather than trying to target individual legislators regardless of party, some groups seek to regularly talk to a particular party or parties, in a particular policy area, over time. They may regard particular parties as more valuable in helping them solve specific policy problems or simply aim at reducing transaction costs (Klüver, Citation2020). These domain-specific interactions are important to understand because policy subsystems are essential for policymaking (Gronow et al., Citation2019; Sabatier, Citation1998). While groups may avoid such routines due to uncertainty regarding benefits, or limited organisational capacity, we ask: how do interest groups pursuing a lobby routine strategy choose their party targets?

Resource exchange theory would suggest that powerful parties are attractive partners for interest groups because they have a greater ability to shape policy (Fouirnaies & Hall, Citation2014; McLean, Citation1987). However, studies have also shown that interest groups lobby legislators who are their presumed allies rather than likely opponents (Baumgartner & Leech, Citation1996; Hojnacki & Kimball, Citation1998) and rather than attempt to change minds provide subsidies to allies to help achieve mutually preferred policy outcomes (Hall & Deardorff, Citation2006). These types of findings have led Berkhout et al. (Citation2019, p. 1) to define the ‘standard model’ of interaction between parties and interest group as resting on ‘power and ideological proximity as two main explanatory factors’ (see also Brunell, Citation2005; De Bruycker, Citation2016; Fraussen & Halpin, Citation2018; Heaney, Citation2010; Klüver, Citation2020; Marshall, Citation2015; Otjes & Rasmussen, Citation2017).

We think that power is a critical factor shaping lobby routines but are less certain about the utility of ideological proximity in explaining lobby routines in specific policy domains. Though the literature on organisational party ties also suggests ideological kinship is important (e.g., Allern & Bale, Citation2017), in contemporary politics most interest groups are intense policy demanders on one or a small number of issues and do not clearly have an ideology per se. Instead, they have policy preferences on specific issues and in particular policy domains and may have preferences closer to different parties in different domains. Therefore, we consider policy position proximity in different policy areas and examine how this, along with power considerations, shapes lobby routines. We argue that policy position proximity makes lobby routines with particular parties more likely, but also that it still matters how powerful specific parties are and that the importance of policy proximity for lobby routines should matter more if parties are powerful.

To test our arguments, we use data from a novel survey of representative samples of interest groups in seven Western democracies. We develop a new measure of the domain-specific proximity of party-interest group policy preferences by calculating the distance between the Chapel Hill expert estimate of a party’s position on the most relevant policy dimension and the interest group’s self-placement on the same policy dimension. The findings provide support for our predictions and have important implications for the study of representation and public policy outcomes.

Theorising interest group and party lobby routines

Parties and interest groups are mutually dependent on each other to reach their goals (Witko, Citation2009). Parties’ office- and policy-seeking rely on interest groups to mobilise financing, volunteers and voters (Allern & Bale, Citation2017). Moreover, interest groups are one of several important sources of expert information that help parties’ craft policy (Ainsworth & Sened, Citation1993; Austen-Smith, Citation1993; Bouwen, Citation2004; Chalmers, Citation2013; Dür et al., Citation2019). As groups transmit political input and support from civil society, they may also boost the legitimacy of party decision-making. Interest groups, for their part, are dependent on parties to advance their policy goals because in many countries parties exercise considerable control over the legislative agenda and voting in parliament (Quinn, Citation2002; Warner, Citation2000). While interactions between parties and groups in the policy process can result from general organisational ties (Allern, Otjes, Poguntke, et al., Citation2020), probably more common are interest group ‘lobby routines’ of the type we examine here: situations where a group usually talks to a specific party across issues in a given policy domain. Working with the same party repeatedly reduces transaction costs, increasing efficiency in pursuit of policy goals.

That said, interest groups do not have to establish routines with parties in legislatures to shape policy. They can instead target executive branch officials, civil servants or the courts, for example. Within legislatures, interest groups might work with individual legislators regardless of party. Of course, these activities require resources, so groups with limited capacity will have less opportunity to pursue any one of them. Even for groups with abundant resources, however, some may prefer to avoid lobby routines with parties because they involve costs, tradeoffs and uncertainty. For instance, establishing routines with one or a few parties can mean forgoing access to multiple parties. Additionally, parties arguably have the upper hand in such interactions because there are many potential groups that can provide parties information through interaction but relatively few party partners for interest groups (Witko, Citation2009). Thus, interest groups need parties more than parties need groups, and groups risk investing time in routines and getting little in return. Given these downsides and other possible means of shaping policy why do groups choose lobby routines with particular parties?

As noted above, we agree that both power and proximity in policy goals are likely to stimulate groups to interact with parties in line with the ‘standard model’. However, we think that policy proximity is more useful to explain lobby routines than general ideological kinship because modern interest groups are distinctive for not having wholesale ideological profiles in the partisan sense. More typically, they have issue preferences in a small number of domains in which they focus limited resources to be effective (Bernhagen et al., Citation2015). Yet, there might be connections between issue positions enabling groups to place themselves in a partisan policy space defined by separate dimensions (Beyers et al., Citation2015). It is exactly this type of positioning we think is of relevance for groups’ choice of establishing lobby routines, which is a meso-level concept that does not take place in highly centralised interactions between party and interest group leaders, nor at the micro-level of the legislator. Groups may prefer different parties in different policy areas. In sum, this suggests that we should think in terms of key conflicts and agreements in different policy areas rather than think about general ideological profiles.

If the general policy goals of parties and interest groups in a particular domain are shared, there is a good chance that the party will consistently pursue the interests of the group (Connelly et al., Citation2011; Veit & Scholz, Citation2016). If this policy agreement exists, lobby routines can help both parties and groups achieve their specific goals by subsidising party efforts in particular policy areas with the systematic provision of information through regularised contact (Hall & Deardorff, Citation2006). Thus, we expect that:

The Policy Distance Hypothesis (H1): the smaller the policy position distance between an interest group and a political party’s position in a given policy area, the higher the probability of a lobby routine with that party.

It is also clear that powerful parties are an attractive partner for interest groups attempting to influence policy on specific issues (Berkhout et al., Citation2019; Fouirnaies & Hall, Citation2014; Marshall, Citation2015; Quinn, Citation2002; Warner, Citation2000). Even if the party is distant in terms of policy preferences, it might be willing to give policy concessions and since it is powerful, these are likely to materialise as public policy. Moreover, as Berkhout et al. (Citation2019) note, ‘relatively powerful parties are also more likely to need particular types of policy-related information offered by interest groups’ (p. 2). Studies confirm that organised interests do seek to interact with powerful parties in many different legislatures (Brunell, Citation2005; De Bruycker, Citation2016; Marshall, Citation2015; Otjes & Rasmussen, Citation2017). Since lobby routines can be established with more than one party, it is possible for organisations to address the most proximate party and the most powerful party if this is not the same, especially in multiparty systems. Thus, all other things being equal, we expect that:

The Party Power Hypothesis (H2): the more powerful a party is, the higher the probability of a group establishing a lobby routine with that party in a given policy area.

That said, groups that, due to capacity constraints, will have to prioritise one strategy, when party qualities do not overlap, will probably emphasise policy proximity. First, because powerful parties have more leverage to extract resources without providing much in return, enduring lobby routines may be difficult to maintain (cf. Lowery et al., Citation2005). Second, the long-term horizon of routines allows groups to also take into account whether proximate opposition parties are likely to end up in power next time. Thus, we expect policy proximity to be a more important factor than party power.

Finally, we argue that the effect of policy proximity differs depending on the level of party power. Both factors are relevant for the same group incentive: prospects of influencing public policy. First, power is likely to strengthen the effect of policy proximity because powerful parties are better able to affect public policy and thus pursue group interests more efficiently. When parties are powerful, the value of shared interests increases. Second, preference proximity will probably matter less for establishment of lobby routines if the party is less powerful since such a party is less likely to influence public decision-making anyway. The value of pursuing shared interests is reduced when parties are weak. Hence, we suggest that the effect of policy proximity is positively conditioned by party power:

The Reinforcing Hypothesis (H3): the relationship between policy proximity and the probability of the group establishing a lobby routine with that party is stronger when the party is more powerful.

Research design

To test our expectations, we primarily use a novel survey data set on interest groups in seven long-established democracies: Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States.Footnote1 While this number of countries is too small to systematically examine country-level variation, we aim to cover interest groups operating in systems with relatively similar historical and economic preconditions but that vary in their institutional settings to produce more generalisable findings. The seven countries differ in terms of party finance regimes, corporatism vs. pluralism and separation of powers. These are all aspects that might stimulate or dampen groups’ incentives to establish routines.

An interest group was defined as any non-party and non-governmental formal association of individuals or organisations that, based on one or more shared concerns, advocates a particular interest/cause in public and usually attempts to influence public policy in its favour in one way or another. The surveys conducted in 2017–2018 combined two different sampling strategies. First, a random sample of interest groups was drawn in each country from sampling frames based on available sources of national interest group populations. Second, we supplemented this with a small, purposive sample of the ‘most important interest groups’ within eight different categories, active in different policy areas, to make sure that a significant number of key groups were covered. Thus, the total sample mirrors the general group population, but with a certain ‘over-sampling’ of major actors (see Allern, Hansen, Røed, et al., Citation2020 for details on sampling strategy).

857 out of 2944 interest groups responded across countries (29 percent). In line with recent cross-national interest group surveys the response rates across countries vary (e.g., Dür & Matteo, Citation2013; Marchetti, Citation2015; Rasmussen & Lindeboom, Citation2013), ranging from nearly 60 percent in Norway to just below 10 percent in the United States. Response rates do not differ significantly in terms of group types (see for Allern, Hansen, Røed, et al., Citation2020 for details on response rates). Due to the low US response rate we also estimated models without it (see Online Appendix Table A2.7), and we control for heterogeneity between the countries by including country fixed-effects in the models.

Dependent variable

The survey asked groups a series of questions about connections with individual parties represented in their national legislatures, ranging from only two in the United States to ten in the Netherlands. Our dependent variable indicates whether an interest group has what we refer to as a ‘lobby routine’ with the party in question in a specific policy area. First, we presented groups with a list of 24 policy areas (listed in Table A.1.1) and asked them to mention up to three of them in which they had been most active during the last two years. 11 percent of groups indicated that they were not active in any of the policy areas included in the survey,Footnote2 22 percent were active in one area, 19 percent two and, 48 percent three. Then for each active area we asked,

When trying to give input to a public decision-making process on a major policy issue, an organization might as a ‘standard procedure’ talk to a particular party/parties and/or their representatives first, independent of whether they are in government or not. Does your organization usually talk to any of the following parties in particular when trying to give input into the decision-making process on a major issue within the policy areas you are most active?

Thus, the question refers to both the party as a collective unit and individuals acting on behalf of the party in the legislature. In this way, we capture the party both at the individual and organisational level and exclude contact with politicians acting without ‘the party hat’ on. The measure is not context-sensitive and should thus work well across the political systems we are studying.Footnote3

For every area a group is active within, we can thus see whether they routinely lobby particular parties or not. After transforming the data structure, our observation is no longer of individual interest groups, but the triad of group-party-policy area. Lobby routines are reported in about a quarter of these party-group-policy area triads, and approximately half of the interest groups report having a lobby routine in at least one policy area. This means that triads involving those reporting to have no such routines at all (in any of the three policy areas), are included in the analysis. By including these cases, we have a more conservative test: if we include groups that have zeros on the dependent variable for all parties irrespective of their power or policy proximity, the associations with these factors should be lower than if they were excluded. Moreover, as will become clear below, we account for factors that are associated with not having lobby routines: we exclude groups with no issue positions from the analysis and control for the groups’ capacity to lobby in general. In the Online Appendix (Table A2.1) we show that these factors are strongly associated with not having a lobby routine at all.

Independent variables

To test The Policy Distance Hypothesis (H1), we developed a novel measure based on our survey and party policy position placement from an expert survey. The construction of this variable is slightly complicated since we have various policy areas, but conceptually it is straightforward. We calculated the distance between the expert estimate of a party’s position on relevant policy dimensions and the interest group’s self-placement on the same policy dimensions.

First, we asked groups to position themselves on six eleven-point scales concerning the environment, immigration, social lifestyle, government intervention in the economy, redistribution and the choice between lower taxation and better public services. These eleven-point scales come from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al., Citation2015; Polk et al., Citation2017). We also provided our key informants with the party positions from the latest round of the CHES so that they had a common baseline and could position their group relative to the parties (see Online Appendix, Section 1) for an illustration). For each interest group that took a position on a given policy dimension, we calculate the absolute distance between the CHES positioning of the party and the interest groups’ self-positioning. An interest group was removed from the analysis if it did not have a position on any of the six dimensions in question.

Second, in order to measure policy distance in a given policy area where groups could indicate they had a lobbying routine, we deductively matched each of our policy areas to one of the CHES dimensions included in the survey (see Table A1.1). This was done by assigning a policy area to the CHES scale expected to be the closest fit for measuring attitudes towards the policy area in question. For example, we matched healthcare and social affairs policy to the redistribution CHES dimension. Note that the same CHES policy dimension might be relevant for more than one of our policy areas in which groups could have lobbying routines. Moreover, for five policy areas in the international sphere no comparable dimension was available. In Online Appendix (Table A2.6) we show that our analysis is robust to switching each match to the second-best alternative. Hence, our policy distance measure reflects the proximity in policy preferences of groups and parties and the distance can differ between specific policy dimensions.

The Party Power Hypothesis (H2) states that interest groups are more likely to establish a routine with powerful parties. To measure party power, we collected data on seat shares and government participation at the time of survey launch (Armingeon et al., Citation2018; Döring & Manow, Citation2018). We constructed an additive scale that combines the share of seats parties have in the present term and whether they are in government. The benefit of doing so is that we can include both measures in the same model even though they are highly correlated. This measure matches the enduring nature of routines: it captures who is in government now and who has a reasonable probability of being in government tomorrow because of their large current seat share, even if they are not currently in power (either as majority party or coalition partner). That said, a party not in government always scores at the lower half of the scale.

Finally, we included the interaction between distance and power to test The Reinforcing Hypothesis (H3).

Controls

We control for several factors. Groups with more resources will have a greater ability to form relationships in the first place because resources make interest groups more attractive partners for parties.

First, money can help groups establish a lobby routine because for parties it is essential to organisational survival (e.g., paying for staff and facilities) and other party goals (Allern & Bale, Citation2017). However, other forms of support from groups are also important (Klüver, Citation2020). Therefore, we use a five-item scale – group donations – constructed from items in the interest group survey where we asked groups whether they provided a direct financial contribution, an indirect financial contribution, whether they contributed labour, material resources or their organisation’s premises during election campaigns to particular parties.Footnote4 To test validity of this item we compared the survey responses on direct financial contributions with publicly available information. There were only a few mismatches and these could be explained by ambiguity of reporting rules.

We also include a dummy variable for whether the group has members. Our expectation is that organisations without members (for instance, organisations representing governments) are less likely to have lobby routines with parties because they cannot provide votes. For parties, groups that can provide high-quality information and expertise will also be more attractive partners (Ainsworth & Sened, Citation1993). Therefore, we use a dummy variable to control for whether groups have regular employees monitoring and commenting on public affairs (policy staff). Fourth, we control for group origin by including a dummy variable that differentiates between interest groups representing specialist economic interests (e.g., trade unions, business) and others. Such groups have been prominent players in some of the classic examples of interest group-party collaboration (e.g., between unions and labour parties) and it is possible that historical legacies have a positive impact on the likelihood of establishing current lobby routines. This variable can also be argued to capture the possible effect of actually having a broad ideological (left-right) profile. To ensure that the associations with the different independent variables are easily comparable they are all recalculated, so their minimum is zero and their maximum is one.Footnote5

Method of data analysis

First, we simply examine descriptive statistics to understand how common it is to have a lobby routine with a party, and whether this is typically with a party that is policy proximate or powerful. Next, we estimate cross-classified mixed logistic regressions accounting for the fact that our dependent variable is dichotomous, and our data has a multi-level structure with possible dependencies between the cases within groups, political parties, policy areas and countries. In order to determine which multilevel structure is necessary, we ran a number of empty models (in Table A2.2 in the Online Appendix). These showed that most variance is at the party and the group level, leading us to ultimately use a cross-classified model with party and group random effects. We use country dummies to control for unobserved heterogeneity between the political systems.

Descriptive results

We begin with some descriptive results ( and ). First, the extent to which groups are active in policy areas varies. One in ten groups are not active in any areas and one of five is active on only one. About the same share of groups is active in two areas and half of groups are active in the maximum number of policy areas they could indicate (three).

Table 1. Group activity by number of areas groups are active on.

Table 2. Descriptives.

The extent to which these groups have a lobby routine with parties also differs. About half of the groups indicate that they have no lobby routine with specific parties at all. shows that the more policy areas a group is active in, the more likely it is they have lobby routines involving parties: out of the groups that are active in a single area, 28 percent have a lobby routine. Out of the groups that are active on three areas, 62 percent have a lobby routine. On average 59 percent of groups that have a lobby routine in more than one area, focus on different parties in those areas. Overall, there is considerable diversity within the groups that we are examining in the number of policy fields in which they are active, in whether they have a lobby routine and in whether they have the same routine partner in different areas.

As can be seen in , on average, a group reports having a lobby routine with approximately one in four parties per policy area. If we disregard the groups that have no routine, groups report having a routine with about half of the parties in a country or two parties per policy area on average. This means that groups with a routine tend to report contacts with on average four parties. Most groups are not focused on a single party, which again suggests the utility of examining interactions by policy domain and that some might follow a ‘dual strategy’ of pursuing proximity and power.

Before we turn to the direct effect of policy distance, we have to mention that the extent to which groups were able to identify their own position on the policy scales differs: 34 percent of the groups cannot position themselves on any dimension, 22 percent of groups position themselves on each of the six dimensions. Between those two extremes, the remaining 50 percent of groups are evenly divided. All in all, though, most groups are not active in many policy domains but are able to place themselves on at least one policy dimension.Footnote6

Multivariate results

To evaluate the importance of policy distance compared to power and controlling for a number of other relevant factors we look at five multivariate models (see ). We first present a model with only policy distance (Model 1), a model with power (Model 2), and one including both variables (Model 3). Model 4 combines the two variables with a number of controls. Model 5 adds the interaction, which allows us to test the third hypothesis. The models show very consistent results for policy distance and party power and there are only minor differences for our control variables. The number of cases is fixed in the different models in order to make sure that we can compare the coefficients and AIC statistics between models, since the AIC is dependent on sample size (Burnham & Anderson, Citation2004, p. 271).

Table 3. Logistic regression models.

First, we find strong evidence that the policy distance between parties and groups decreases the likelihood of a routine lobby connection (The Policy Distance Hypothesis, H1). There is a strong and significant relationship in the expected direction in each of the models in . In each of these, the effect is similar in strength, direction and level of significance. In Model 4 in , which includes party power and all control variables, the likelihood of lobbying ties decreases from 41 percent to 21 percent when moving from the party-organisation dyads that are closest to each other in a policy area to those that are furthest from each other the. It is thus clear that policy proximity plays a role in the development of lobby routines.

We also see that The Party Power Hypothesis (H2) is supported: 53 percent of the most powerful parties (parties that have more than fifty percent of the seats and are in government) are predicted to be part of an interest group’s lobby routine, compared to 28 percent for the least powerful.

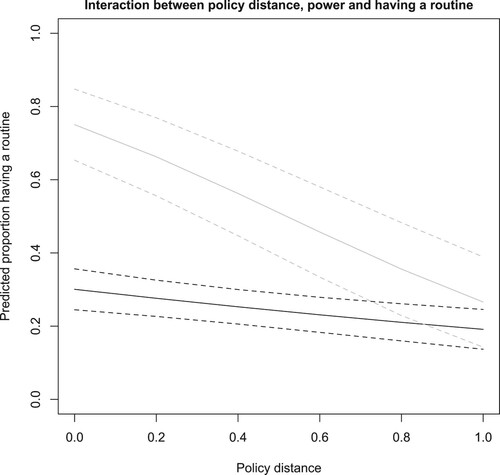

We furthermore expected that power and policy distance have a multiplicative effect beyond these simple additive effects (The Reinforcing Hypothesis, H3). The results are shown in Model 5 and displayed graphically in . These show a significant interaction effect between policy distance and power. When a party is powerful, the effect of policy distance is strong while the effect of policy distance is weaker for parties with little power. Routines are most likely to occur when policy distance is small, and power is high. The likelihood of having a lobby routine in that case is about three in four for the powerful parties and only three in ten for the least powerful parties. As distance increases the likelihood of having a routine decreases; but for the least powerful parties it decreases by 36 percent, while for the most powerful parties, this likelihood decreases by 65 percent. The decrease is smaller for the least powerful parties (from three in ten to three in twenty). While the difference in having a routine between powerful and non-powerful parties is significant when they are close, the difference is no longer significant beyond a distance of 0.8.

Figure 1. Predicted proportion having a routine as function of policy distance. Grey lines: high power (power = 1); black lines: low power (power = 0). Predicted proportion with 90 percent confidence intervals. Based on Model 5.

While policy distance also affects the likelihood of having a lobby routine for powerless parties according to Model 5, its effect is much smaller for such parties. This is consistent with the Reinforcing Hypothesis (H3): the more powerful a party is, the stronger the effect of policy distance on the probability of the group establishing a lobby routine with that party. Likewise, the value of policy proximity is clearly reduced for less powerful parties.

The effect of the control variables are generally as expected. 96 percent of the triads where groups actively donated all the different resources to a party have a lobby routine. But these are only exceptional cases (1 percent of the cases). In the cases without any donations the likelihood of lobby routines is low (33 percent). We also find a strong positive effect of staff resources. 44 percent of the groups that have any policy workers are predicted to have a lobby routine involving particular parties compared to 31 percent for the groups that have no policy workers. Whether a group has members is also associated with whether they include a party in their lobby routine, albeit not in the expected direction: 32 percent with members and 40 percent without. Groups representing economic interests are not significantly more likely to have a lobby routine than the remaining groups. Overall, the controls suggest that abundant resources enhance the ability to form lobby routines. All these results are visualised in Online Appendix (Figure A2.3 to A2.6). Finally, we see that all countries tend to score higher than France, especially groups in Denmark and the Netherlands, which might suggest that institutional differences like the degree of corporatism play a part, although further study is needed to disentangle this.

How should we evaluate the relative importance of policy distance versus power? Moreover, do the two theoretical models reinforce each other? In order to answer these questions, we compare the AIC scores, which is a relative measure of model fit with lower scores indicating a better fit. Any model with an AIC 10 points higher than the AIC of another model, has ‘essentially no support’ to be a better model than the other (Burnham & Anderson, Citation2004, p. 271). Comparing Model 1 to Model 2, we observe that the AIC is more than 10 points lower in Model 1: this means that when considered alone policy distance has, as assumed, more explanatory power than political power. We further observe that AIC values drop by more than 10 points when we add both policy distance and power; when we add the control variables the fits improve by another ten points. The interaction provides the best fit of the models in , but in terms of strength it is comparable to the model without the interaction. Finally, extensive robustness tests are included in Online Appendix (Section 2), and the results generally hold.

Conclusion

This article adds to the literature on the interactions between parties and interest groups. While previous studies have often focused on either issue-oriented lobbying of individual politicians or general organisational party-group ties, we address interest group-party lobby routines in different policy domains. These are important because in increasingly pluralistic politics this is where much influence takes place. Moreover, while those studies of party-group contacts that actually exist posit that power and ideology best predict these interactions, we argue that most groups do not have an ideology, and that it is more useful to think in terms of policy proximity and distance along specific policy dimensions. Our descriptive statistics showing that many groups do not position themselves on more than one or two policy dimensions bore this out. In this way, we are able to account for cross-area party variation in the groups’ lobby routines. Empirically, we contribute by analysing data from a novel survey of representative samples of interest groups across seven established democracies.

Generally, we find support for our predictions. Interest groups select parties with proximate general policy positions to work with in the policy areas that they care most about. The results could similarly indicate that parties are more willing to regularly talk to groups who share their policy orientation in a given area. Thus, even if shorter-term power considerations play a part, it seems as if groups apply at least a medium-term perspective when trying to establish a lobby routine. We also saw that policy distance has more explanatory power alone than party power. At the same time, the results suggest that power and policy distance are not necessarily competing explanations: they explain more together than they do apart. In addition, there is an interaction effect between the two, where the effect of policy proximity is particularly strong for the most powerful parties. Parties that are both powerful and proximate on a relevant dimension, in a given policy area, are more attractive than one would expect merely on the basis of their power and proximity. The two factors reinforce each other making this combination particularly attractive.

A question for future research is why certain groups do not form lobby routines with political parties at all. Future research should also consider the implications of the lack of lobby routines for policy influence. It seems clear that group resources help in the establishment of lobby routine, which explains some of the absence of routines. Another possible explanation for the absence of lobby routines is that some groups may not be able to position themselves, or relate to, the predominant dimensions in particular policy areas either because they pursue interests of limited party-political relevance/controversy or they may have fundamentally different policy preferences than any existing parties. How such differences affect patterns of political influence, are possible avenues for future studies.

A key goal for future research is also to improve the analysis of causality. We have identified correlations in line with expectations, but it is indeed possible that the relationship between lobby routines and issue positions goes both ways: that establishment of a lobby routine will, in turn make it more likely that parties and groups are issue proximate in the future due to contact and (mutual) influence. Our study does not delve into these particular causal questions, but if data on interest group behaviour over time becomes available, it will become possible to examine these dynamics in more detail.

Clearly, interest group influence attempts go beyond single issues and the short-term perspective of who is currently in power. Our findings suggest that policy-based group-party structures, and perhaps even alliances, exist in different fields. The revealed group-party routines might constrain party decision-makers but also group leaders. How this affects parties, and groups, as vehicles of representation is a key issue for future research. Taking into account the possible existence of lobby routines and thus relations when trying to explain both policy inputs and outcomes in legislative politics can advance our understanding of how representative democracy and the policy process work.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (997.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank PAIRDEM’s data manager, Vibeke Wøien Hansen, for all her efforts and Eirik Hildal, plus, above all, Lise Rødland and Maiken Røed, for excellent research assistance. We are also thankful to the rest of the PAIRDEM core research group, Tim Bale, Thomas Poguntke and Paul Webb, and the locally recruited research assistants, who helped when preparing and fielding the PAIRDEM interest group survey. We are grateful for feedback from participants at the ECPR General Conference in 2018, the 2018 APSA Annual Meeting, the 2019 PAIRDEM project conference and EPSA’s annual conference in 2020. We would in particular like to thank Mihail Chiru, Kaare Strøm and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elin Haugsgjerd Allern

Elin Haugsgjerd Allern is Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Oslo.

Heike Klüver

Heike Klüver is Professor and Chair of Comparative Political Behavior at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

David Marshall

David Marshall is Associate Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Reading.

Simon Otjes

Simon Otjes is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Leiden University and Researcher at the Documentation Centre Dutch Political Parties of Groningen University.

Anne Rasmussen

Anne Rasmussen is a Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen. In addition, she is a Professor II at the Department of Comparative Politics, University of Bergen and affiliated to the Institute of Public Administration, Leiden University.

Christopher Witko

Christopher Witko is Associate Director and Professor in the School of Public Policy at Pennsylvania State University.

Notes

1 ‘Party-Interest Group Relationships in Contemporary Democracies’ (PAIRDEM), see https://pairdem.org/pairdem/

2 These were not included in the analysis.

3 Importantly, we refrain from asking interest groups to indicate the ‘intensity of their interaction’ given that talking to a party as a ‘standard procedure’ already refers to regularised interaction of a high intensity.

4 These items scale very well according a Mokken scaling analysis (Loevinger’s H=0.60).

5 The strongest bivariate relationship between the independent variables in our analysis belongs to the robustness tests (see Online Appendix): a correlation between ‘party challenger status’ and ‘the year a party obtained parliamentary representation’ of 0.36. All other bivariate correlations are well below that level. We do not include these two variables in the same analysis.

6 Interestingly, the extent to which groups have lobby routines involving parties at all closely follows this: out of those who cannot place themselves on any dimension 36% report having a lobby routine, this increases over to 74% for the groups that can place themselves on each dimension. One of the explanations of why groups do not have lobby routines may reflect whether they have positions along the same policy dimensions as parties, or seek other types of policy goals. In the Online Appendix (Table A2.1), we study this issue in greater detail by also including the units without any positions on the six policy dimensions.

References

- Ainsworth, S., & Sened, I. (1993). The role of lobbyists: Entrepreneurs with two audiences. American Journal of Political Science, 37(3), 834–866. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2111576

- Allern, E. H., & Bale, T. (2017). Left-of-centre Parties and Trade Unions in the Twenty-First Century. Oxford University Press.

- Allern, E. H., Hansen, V. W., Marshall, D., Rasmussen A., & Webb, P. (2020) ‘Competition and interaction: Party ties to interest groups in a multidimensional policy space’, European Journal of Political Research 60, 2, 275–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12403

- Allern, E. H., Hansen, V. W., Røed, M., & Rødland, L. (2020). ‘The PAIRDEM Project: Documentation Report for Interest Group Surveys’. Department of Political Science, University of Oslo. Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://pairdem.org/codebooks-and-survey-documentation-reports/

- Allern, E. H., Otjes, S., Poguntke, T., Hansen, V. W., Marshall, D., & Saurugger, S. (2020). Conceptualizing and measuring party-interest group relationships. Party Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820949393

- Armingeon, K., Wenger, V., Wiedemeier, F., Isler, C., Knöpfel, L., Weisstanner, D., & Engler, S. (2018). Comparative political data set 1960-2016. Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Accessed at: https://cpds-data.org/.

- Austen-Smith, D. (1993). Information and influence: Lobbying for agendas and votes. American Journal of Political Science, 37(4), 799–833. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2111575

- Austen-Smith, D., & Wright, J. R. (1994). Counteractive lobbying. American Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 25–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2111334

- Bakker, R., de Vries, C., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2015). Measuring party positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill expert survey trend file’, 1999–2010. Party Politics, 21(1), 143–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812462931

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Leech, B. L. (1996). The multiple ambiguities of counteractive lobbying. American Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 521–542. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2111636

- Berkhout, J., Hanegraaff, M., & Statsch, P. (2019). Explaining the patterns of contacts between interest groups and political parties: Revising the standard model for populist times. Party Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819856608

- Bernhagen, P., Dür, A., & Marshall, D. (2015). Information or context: What accounts for positional proximity between the European commission and lobbyists? Journal of European Public Policy, 22(4), 570–587. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1008556

- Beyers, J., De Bruycker, I., & Baller, I. (2015). The alignment of parties and interest groups in EU legislative politics. A tale of two different worlds? Journal of European Public Policy, 22(4), 534–551. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1008551

- Bouwen, P. (2004). The logic of access to the European Parliament: Business lobbying in the committee on economic and monetary affairs. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 42(3), 473–495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9886.2004.00515.x

- Brunell, T. L. (2005). The relationship between political parties and interest groups: Explaining patterns of PAC contributions to candidates for congress. Political Research Quarterly, 58(4), 681–688. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290505800415

- Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2004). Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods Research, 33(2), 261–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644

- Chalmers, A. W. (2013). Trading information for access: Informational lobbying strategies and interest group access to the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(1), 39–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.693411

- Connelly, B. L., Certo, T. S., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310388419

- De Bruycker, I. (2016). Power and position: Which EU party groups do lobbyists prioritize and why? Party Politics, 22(4), 552–562. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068816642803

- Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2018). Parliaments and governments database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies (Development Version). http://www.parlgov.org/

- Dür, A., Marshall, D., & Bernhagen, P. (2019). The Political Influence of Business in the European Union. University of Michigan Press.

- Dür, A., & Matteo, G. (2013). Gaining access or going public? Interest group strategies in five European countries. European Journal of Political Research, 52(5), 660–686. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12012

- Eichenberger, S., & Mach, A. (2017). Formal ties between interest groups and members of parliament: Gaining allies in legislative committees. Interest Groups Advocacy, 6(1), 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-017-0012-2

- Fouirnaies, A., & Hall, A. B. (2014). The financial incumbency advantage: Causes and consequences. The Journal of Politics, 76(3), 711–724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381614000139

- Fraussen, B., & Halpin, D. R. (2018). Political parties and interest organizations at the crossroads: Perspectives on the transformation of political organizations. Political Studies Review, 16(1), 25–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929916644868

- Gronow, A., Ylä-Anttila, T., Carson, M., & Edling, C. (2019). Divergent neighbors: Corporatism and climate policy networks in Finland and Sweden. Environmental Politics, 28(6), 1061–1083. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1625149

- Hall, R. L., & Deardorff, A. (2006). Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review, 100(1), 69–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055406062010

- Heaney, M. T. (2010). Linking political parties and interest groups. In S. L. Maisel & J. M. Berry (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of American Political Parties and Interest Groups (pp. 568–587). Oxford University Press.

- Hernandez, E. (2018). Democratic discontent and support for mainstream and challenger parties: Democratic protest voting. European Union Politics, 19(3), 458–480. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518770812

- Hojnacki, M., & Kimball, D. C. (1998). Organized interests and the decision of whom to lobby in congress. American Political Science Review, 92(4), 775–790. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2586303

- Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D. C., Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., & Leech, B. (2012). Studying organizational advocacy and influence: Reexamining interest group research. Annual Review of Political Science, 15(1), 379–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-070910-104051

- Key, V. O. (1964). Politics, Parties and Pressure Groups (5th ed.). Thomas Y. Crowell Company.

- Klüver, H. (2020). Setting the party agenda: Interest groups, voters and issue attention. British Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 979–1000. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000078

- Koger, G., Masket, S. E., & Noel, H. (2009). Partisan webs: Information exchange and partisan networks. British Journal of Political Science, 39(3), 633–653. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409000659

- Lowery, D., Gray, V., & Fellowes, M. (2005). Organized interests and political extortion: A test of the fetcher bill hypothesis. Social Science Quarterly, 86(2), 368–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2005.00308.x

- Marchetti, K. (2015). The use of surveys in interest group research. Interest Groups and Advocacy, 4(3), 272–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/iga.2015.1

- Marshall, D. (2015). Explaining interest group interactions with party group members in the European Parliament: Dominant party groups and coalition formation. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(2), 311–329. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12163

- McLean, I. (1987). Public Choice: An Introduction. Basil Blackwell.

- Otjes, S., & Rasmussen, A. (2017) The collaboration between interest groups and political parties in multi-party democracies: Party system dynamics and the effect of power and ideology. Party Politics, 23(2): 96–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068814568046

- Polk, J., Rovny, J., Bakker, R., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Koedam, J., Kostelka, F., Marks, G., Schumacher, G., & Steenbergen, M. (2017). Explaining the salience of anti-elitism and reducing political corruption for political parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey data. Research & Politics, 5(1), 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168016686915

- Quinn, T. (2002). Block voting in the Labour Party: A political exchange model. Party Politics, 8(2), 207–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068802008002004

- Rasmussen, A., & Lindeboom, G.-J. (2013). Interest group–party linkage in the twenty-first century: Evidence from Denmark, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research, 52(2), 264–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02069.x

- Sabatier, P. A. (1998). The advocacy coalition framework: Revisions and relevance for Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 5(1), 98–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501768880000051

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1948). Pressure groups versus political parties. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 259(1), 17–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000271624825900104

- Veit, S., & Scholz, S. (2016). Linking administrative career patterns and politicization: Signalling effects in the careers of top civil servants in Germany. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82(3), 516–535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852314564310

- Warner, C. M. (2000). Confessions of an Interest Group: The Catholic Church and Political Parties in Europe. Princeton University Press.

- Witko, C. (2009). The ecology of party-organized interest relationships. Polity, 41(2), 211–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2008.30