ABSTRACT

The European Union (EU) faces two parallel trends of growing polarization. Externally, ambitious climate action has become more contested and global power relations are shifting. Internally, European elections brought more Eurosceptics to Parliament, altering its political majorities and making it more difficult for mainstream parties to continue the European Parliament’s (EP) long-standing policy positions such as ambitious climate policy. We analyze the impact of growing internal and external polarization trends on Members of European Parliament (MEPs) and political group’s positions on EU foreign climate policy ambitions between 2009 and 2019. Using an original dataset of plenary debates, we find that the EP as a whole has remained surprisingly stable in its support of ambitious foreign climate policy. Yet, when looking at the qualitative details of MEPs’ positions, we uncover significant variance in the ways in which MEPs from various political groups perceive the EU’s global role over time.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) faces two parallel trends of growing polarization and fragmentation: At the international level, great power competition has re-emerged and multilateral cooperation has changed towards the increasing contestation of Western liberal norms (Ikenberry, Citation2018). Within the EU, the rise of Eurosceptic and right-wing political parties challenges traditional mainstream parties (Hodson & Puetter, Citation2019; Huber et al., Citation2021; von Homeyer et al., Citation2021). The European Parliament (EP) is at the intersection of both trends. The 2014 European elections brought more Eurosceptics and populists to Parliament (Hobolt, Citation2015), making it more difficult for mainstream parties to continue the EP’s long-standing policy positions. External contestation of the very same policy positions by, for example, former United States (US) President Trump, and re-emergent (norm) competition in multilateral cooperation add a second challenge. In climate policy, growing external and internal polarization are aligned since external and internal contesters pursue low climate ambitions, challenging the norms and goals enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. This development clashes with the EP’s traditional position as ‘champion’ among EU institutions in pushing for climate ambition, though less radically over the past two decades than in the early 1980s and 1990s (Burns, Citation2019; Burns et al., Citation2013). The intertwined polarization trends point towards growing pressure on the EP, suggesting less ambitious climate policy positions in times when more ambition is needed to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goals.

This article analyzes the impact of the growing dual polarization trend on foreign climate policy (FCP) ambitions of Members of European Parliament (MEPs), both individually and aggregated at political group level. We focus on FCP since this is a likely case for the dual polarization trend to influence MEPs’ positions: Climate change is a collective action problem, which the EU alone cannot solve, making it dependent on the international context. Additionally, its increasingly politicized nature suggests internal changes of climate policy ambitions. Our study spans the 2009–2014 and 2014–2019 legislative terms. This time frame allows us to both establish whether the political changes heralded by the 2014 European elections influenced MEPs’ FCP ambitions and to investigate the impact of growing external polarization. Our study analyzes the qualitative changes in how MEPs justify their positions in support of high and low climate ambition and what drives their FCP stances.

The analysis contributes to existing EP literature with its qualitative in-depth analysis of plenary speeches and its focus on FCP. Most studies of the EP political dynamics use roll call votes (e.g., Buzogány & Ćetković, Citation2021; Raunio & Wagner, Citation2020), which only allow a binary analysis of whether MEPs are in favour of or against a certain provision. Justifications of votes cannot be captured. Qualitatively analysing speeches helps disentangle and understand the various positions and dynamics within the EP. Furthermore, studies on EP climate ambition and leadership have mostly focused on internal policies (Burns, Citation2019) with a few recent exceptions (e.g., Delreux & Burns, Citation2019). Our analysis adds to the emerging literature on the EP’s foreign (climate) policy, defined as a policy ‘directed at the external environment with the objective of influencing that environment and the behaviour of other actors within it, in order to pursue interests, values and goals’ (Keukeleire & Delreux, Citation2014, p. 1).

Existing studies on the EP’s FCP use EP resolutions and similar documents, thereby often treating it as a unitary actor (Biedenkopf, Citation2019; Delreux & Burns, Citation2019; Wendler, Citation2019). Our study explores the political debate within the EP, providing insights into the different perceptions on international climate action across Europe. Moreover, analyzing MEPs’ and political groups’ FCP positions over time enhances our understanding of the EP as an increasingly relevant, yet so far understudied foreign policy actor (Raube et al., Citation2019; Stavridis & Irrera, Citation2015). Recent studies have demonstrated that with growing powers to shape EU internal climate policies, the EP has also increasingly influenced the EU’s foreign climate policies, for example, through the consent procedure, sending delegations to United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations and producing own initiative reports (Biedenkopf, Citation2015; Delreux & Burns, Citation2019; Wendler, Citation2019). Further, in climate policy, the link between internal and external policy is stronger than in many other areas, as the EU’s external credibility essentially builds on its internal ambition (Oberthür & Dupont, Citation2021), giving the EP a growing role in EU FCP.

Our results show that internal and external polarization trends have not significantly impacted MEPs’ overall level of climate ambition, while it has shaped their perceptions and explanations of EU ambition. This demonstrates the interplay between external and internal dynamics. In this way, we can establish a link between the polarization trends and MEPs’ positions. Between 2009 and 2019, MEPs and political groups increasingly accepted EU international responsibility for climate action and used this as one of the main justifications for high EU climate ambition. While MEPs saw the EU as internationally side-lined after the failed 2009 Copenhagen climate conference (Groen & Niemann, Citation2013), this discourse faded and disappeared after 2017. Our data shows an increase in geopolitical leadership ambition, which confirms that the EU found its international role as a ‘leadiator’, leading and mediating among countries (Bäckstrand & Elgström, Citation2013; Oberthür & Dupont, Citation2021). Nevertheless, MEPs who support high ambition are weary of the EU losing competitiveness, which has led to growing calls for conditionality and border measures to coerce other countries into following the EU’s lead. All in all, MEPs and political groups have remained stable in their support for ambitious FCP. This complements findings that the EP continues to be a ‘strategic environmental advocate’ (Burns, Citation2019, p. 324) despite an overall ‘less radical’ tone and tempering policy ambition towards other EU institutions (Burns et al., Citation2013, p. 949; Burns & Tobin, Citation2020). Yet, we find polarization among EP political groups in their qualitative justifications of foreign climate ambitions.

The next section further discusses the dual polarization trends that could impact individual MEPs’ and political groups’ FCP positions. Based on this, we develop a framework that, on the one hand, disentangles responses to international polarization into economic, emissions-related and geopolitical shifts and, on the other, differentiates ‘low ambition’ and ‘high ambition’ positions on EU FCP. This is followed by a discussion of our research design and the qualitative content analysis. We then present our results, delving into the details of MEPs’ justifications and positions with a focus on the dynamics among the different political groups. The concluding section places our findings in a broader context.

Global shifts, polarization and European Parliament responses

Internal and external polarization trends – defined as a process of positions drifting apart towards more extremes (de Wilde et al., Citation2016) – shape MEPs’ positions on the EU’s role and ambition in international climate policy and discursive justifications thereof. Our analysis focuses on two of the five crisis trends identified in the introduction to this special issue (von Homeyer et al., Citation2021): First, growing socio-political divisions within Europe have driven political changes in the EP’s composition. Second, geopolitical shifts have led to growing contestation of ambitious climate action. These two trends are highly intertwined. Especially, the rise of climate-sceptic leaders could align with and reinforce similar developments within the EP, where political groups associated with climate scepticism have grown in size. However, this polarization could also provoke a counter-reaction by MEPs who support ambitious (foreign) climate policy to contain the influence of external and internal contesters of long-standing EP policy positions. This section first describes the shifts in global climate politics, based on which six arguments are distinguished. Expectations regarding these arguments and the growing parliamentary fragmentation are discussed in the second part.

Shifting global climate politics and MEPs’ justifications

Shifts in global climate politics take place against the backdrop of broader changes, most notably (a) changes in the economic world order, (b) shifts in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emission shares, and (c) challenging external relations and geopolitics. Those three interlinked global developments could shape MEPs’ positions on EU FCP. Each of those shifts could give rise to a ‘high-ambition’ and a ‘low-ambition’ position, resulting in six argumentative patterns, as summarized in .

Table 1. Typology of arguments.

The economic world order has shifted towards emerging economies, particularly China. Europe’s share of global gross domestic product dropped from 28.73 percent in 1990 and 24.35 percent in 2009 to 19.68 and 17.78 percent in 2014 and 2019 respectively (World Bank, Citationn.d.). This decline in the EU’s relative economic weight – over the past decade in particular – reduces its market power and capacity to shape global regulation (Vogel, Citation2012), which makes it more vulnerable to competitiveness concerns. If the EU imposes ambitious climate requirements on its domestic economy while other countries do not, European companies could lose market shares since their production is likely to be more expensive. This could lead to the relocation of companies to outside Europe, a process called carbon leakage since emissions still occur, just not in the EU (van Asselt & Brewer, Citation2010). Some countries’ abandonment of the Paris Agreement’s goals, leading to growing international polarization, could be perceived by MEPs as a justification to lower EU climate ambition in order to remain globally competitive. Contrariwise, the increasing domestic and international demand for low-carbon technologies could lead MEPs to argue for high climate ambitions to spur innovation and gain competitiveness.

Global shares of GHG emissions have substantially changed. In 1990, the EU had the second highest share of annual global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions with 19.68 percent, only second to the US (22.54 percent). In 2009, the EU accounted for 12.14 percent of global emissions and in 2019 for only 8 percent. The EU now ranks third after China (27.92 percent) and the US (14.50 percent) (Global Carbon Atlas, Citationn.d.). Taking a historical perspective, however, the EU’s cumulative emissions from 1751 to 2017 account for 22.61 percent of global emissions, whereas China is responsible for only 12.82 percent (Ritchie & Roser, Citationn.d.). With China’s growing and Europe’s declining GHG emissions, their historical responsibility will converge over the coming years. Responsibilities based on current and historical emissions have long been a core contention in international climate politics (Petri & Biedenkopf, Citation2020). Focusing on current figures, MEPs could claim that the EU’s share of global GHG emissions is relatively low, which is why it cannot make a difference internationally, thereby justifying low ambition. Contrarily, MEPs could justify high ambitions based on the EU’s responsibility for historical emissions and perceptions of the EU’s current share as significant.

Geopolitical shifts based on growing populations, increasing economic power and expanding military capabilities have altered the dynamics of international politics. This shift is an overarching trend that encompasses more specific economic and emission shifts and also a number of other factors that influence a country’s power. In climate negotiations, no single country can impose action on others and consensus among all parties is required. Up until 2016, the US and China collaborated on climate policy and the EU successfully reached out to many climate-vulnerable countries, among numerous other diplomatic activities (Biedenkopf & Walker, Citation2016). The election of Donald Trump as US President shook international climate politics to the core. Contestation of the system of ever-more ambitious national climate policy pledges that builds the core of the Paris Agreement grew from 2016 onwards, spearheaded by President Trump but also Brazil’s and Australia’s leaders. Growing international polarization in combination with geopolitical shifts to a multipolar world could lead MEPs to justify the lowering of EU climate ambition, arguing that today other powers shape global climate policy and are more influential than the EU. In contrast, high ambition could be justified by MEPs’ aspiration to contain any contestation impact, perceiving the EU as an influential actor.

Parliamentary polarization and fragmentation

The global shifts could give rise to different, opposing argumentations within the EP, as described in the previous section. Since actors do not easily change their fundamental beliefs (Sabatier, Citation1993), it seems more likely that MEPs who already support or oppose ambitious FCP will keep these beliefs and use either the respective high or low ambition arguments. Changes in fundamental values and beliefs either occur over a longer period of time or in the case of sudden dramatic perturbations. The global shifts have occurred rather gradually, with the exception of political changes such as the election of former President Trump. For this reason, and following the party cohesion literature, we assume that MEPs from the same political group support relatively cohesive levels of climate ambition and use similar argumentative patterns. We expect stronger cohesion among the centre, mainstream groups than among smaller groups (Bowler & McElroy, Citation2015; Hix et al., Citation2009).

A political shift marked the 2014 European elections, which set the 2009–2014 and 2014–2019 legislative terms apart. The difference in group shares was not dramatic but noteworthy, reflecting growing socio-political divisions (von Homeyer et al., Citation2021). According to Hobolt (Citation2015, pp. 12–14), the 2014–2019 EP was comprised of as much as 29 percent of MEPs from Eurosceptic parties. In the 2014 elections, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) lost seven percentage points, down to 29 percent, and the centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) remained at 25 percent. The liberals (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE)) lost two percentage points and the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) remained at seven percent. The winners were the Eurosceptic groups on the right and left extremes of the political spectrum: the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR, 9 percent), the Europe of Freedom and (Direct) Democracy (EFD(D), 6 percent), and the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL, 7 percent). The number of non-attached members (NIs) increased significantly from 26 to 52 (7 percent). In 2015, the group Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF) was formed, building a new coalition of previously fragmented right-wing parties.

Since, generally, most right-wing political parties are relatively sceptical towards climate change (Huber et al., Citation2021; Lockwood, Citation2018), the growing EP polarization could suggest a change of the overall EP’s FCP ambition. Moreover, shares of Eurosceptic members have increased not only among left and right-wing but also within mainstream parties (Forchtner, Citation2019). Conservative political parties generally are committed to climate mitigation policy but sometimes support fossil fuel development (Hess & Renner, Citation2019). Citizens who identify with centre-left political ideology tend to be more supportive of climate mitigation than those who identify with the centre-right (McCright et al., Citation2016). The growing number of right-wing MEPs would thus suggest that the voices advocating low EU climate ambition became proportionally louder. This position is further strengthened by international trends that could be interpreted as supporting their position. Consequently, we expect differences across the EP’s political groups and MEPs’ argumentative patterns and support for (un)ambitious FCP.

Research design and methodology

Our qualitative analysis focuses on the plenary debates that were dedicated to FCP in the 2009–2014 and 2014–2019 legislative terms. It is based on 1,427 MEP speeches held in a total of 22 plenary sessions (11 debates per legislative term, for a detailed overview, see Appendix I). Plenary debates are most representative of the EP as a whole, since speaking time is strictly regulated among groups (Rule 171, EP Rules of Procedure), best mirroring MEPs’ overall policy position and each political group’s argumentation. While most of the debates were prior to or shortly after the annual UNFCCC meetings, MEPs go beyond specific negotiation strategies and provide broader insights into their perceptions of the EU’s role in global climate politics. As opposed to technical debates in specialized committee settings, MEPs also state policy positions in a more general and overarching way. This makes plenary debates an excellent data source to analyze arguments used to justify policy positions, revealing MEPs’ motivations. Such insights cannot be gained based on roll-call vote analysis (e.g., Buzogány & Ćetković, Citation2021; Raunio & Wagner, Citation2020) or the analysis of outcome documents, such as EP resolutions, which reflect a compromise among MEPs (Delreux & Burns, Citation2019; Wendler, Citation2019). Since the EP administration stopped offering translated transcripts of plenary debates in 2012, we hired student assistants to translate MEP speeches from their mother tongue into English.

Using the software NVivo 12 (Jackson & Bazeley, Citation2019), we coded both MEPs’ advocated level of ambition for EU FCP and their arguments justifying their position. First, we coded all 1,427 MEP speeches to identify those that explicitly referred to FCP. A number of MEPs used their speaking time for other issues, for example domestic climate policy, and were excluded. This initial coding resulted in a dataset of 769 speeches. Second, the speeches were further analyzed according to the six arguments identified above. This produced 2,879 units of observation (arguments used to justify high/low ambition positions). Since qualitative coding always contains subjective judgement, we closely followed the Qualitative Content Analysis approach, specifically a structuring technique of ‘deductive category assignment’ (Mayring, Citation2014, pp. 63–65, 95–103) (for an overview of coding categories, see Appendix II). In line with best practices of qualitative coding, we asked a third party who previously was not involved in our research to code 11.6 percent of the speeches to ensure inter-coder reliability. The inter-coder agreement was high (86.5 percent), confirming the rigorousness of our analysis and reliability of our coding. While linguistic nuances could get lost in translated MEP speeches, our analysis is resilient to this, since we did not analyze semantics but rather whole arguments.

MEPs’ foreign climate policy ambitions and their justifications, 2009–2019

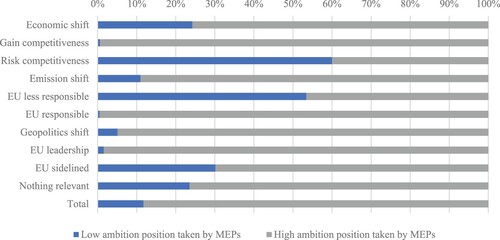

Cumulatively, MEPs weathered growing polarization and maintained strong discursive support for ambitious FCP. MEPs who argued for low climate ambition used economic arguments of losing competitiveness most frequently, while those advocating high ambition most often used emissions-related justifications and referred to the EU’s responsibility. Almost all MEPs, regardless of their advocacy for high or low ambition, perceived the EU as a global climate leader. This section presents the findings of the qualitative analysis of MEP speeches in the EP plenary between 2009 and 2019. We start by presenting MEPs’ low and high ambition positions and then discuss how the three global shifts are reflected in MEP speeches and their role in shaping MEPs’ perceptions of the EU as a global climate player.

MEPs’ foreign climate policy ambitions

The growing internal and external polarization has not significantly impacted MEPs’ overall strong support for ambitious FCP. We coded all 769 MEP speeches in the dichotomous policy position variable ‘high ambition’ and ‘low ambition’ of FCP (Appendix III, Table 6). Ambitions were not interpreted relative to the status quo or the Council or Commission position but rather in absolute terms, judging whether the MEP advocates high or low climate ambition. There were few cases of doubt, but the qualitative coding allowed us to deduce levels of ambition based on the content of the speech. Some MEPs harshly criticized specific EU climate policies but generally supported ambitious climate policy, just designed differently. Those speeches were coded as ‘high ambition’.

The large majority of MEPs spoke out in favour of ambitious FCP (88.3 percent), while a minority voiced low ambitions (11.7 percent). We did not find considerable variation between the two legislative terms, yet significant annual variation among the shares of ‘low-ambition’ MEPs, ranging between zero/five (2013, 2019) and 17 percent (2010, 2011) (Appendix III, Graph A3).

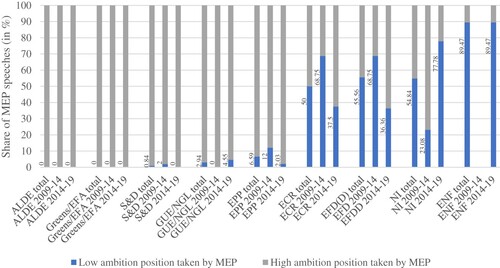

A clear bifurcation between low and high ambitions could be noticed among the political groups (). No single MEP from the ALDE and Greens/EFA and only very few S&D, GUE/NGL and EPP MEPs advocated low ambitions. This is in stark contrast with ENF MEPs who almost entirely and ECR, EFD(D) and non-attached MEPs who mostly advocated low ambitions. The latter three groups revealed the highest fragmentation of positions and thereby lowest cohesion. While MEPs’ cumulative policy positions remained stable, individual groups increased their support for ambitious FCP: ECR and EFD(D) from 31.3 to 62.5/63.6 percent, the EPP from 88.0 to 98.0 percent. This was counterbalanced by a stark increase of non-attached MEPs advocating low climate ambitions and the addition of the ENF, which also predominantly pursued low ambitions. This development corroborates the expectation that especially right-wing political groups hold climate-sceptic policy positions (Forchtner, Citation2019; Lockwood, Citation2018).

Figure 1. Comparison of low ambition and high ambition positions per political group (2009–2019) (in %).

When comparing the shares of speeches per political group in our dataset with the actual EP composition in each legislative period (Appendix III, Graphs A1-2), we identified three trends. First, the two largest political groups were overrepresented (S&D +5.72, EPP +3.42 percent). This can partly be explained by a high number of written statements by these two resourceful groups, which can be seen as an attempt to compensate for seat losses (in particular by the EPP following the 2014 elections). Second, the smaller groups with high FCP ambitions were slightly under-represented (Greens/EFA −0.86, GUE/NGL −1.44, ALDE −2.25), which suggests that these smaller groups focus their activities less on the plenary and more on committee debates. Third, the smaller groups with low ambition varied in their activity levels. While EFD(D) and ENF were relatively under-represented (−1.18 and −0.43), MEPs from ECR and NIs were comparatively more vocal (+1.04 and +0.52). The ECR group was considerably more vocal in the second legislative period (−2.68 vs. +4.75), a relevant trend considering that its MEPs, at the same time, became more ambitious (see above).

Economic arguments

Delving into MEPs’ specific justifications of advocated climate ambition, they use economic arguments least frequently. 290 out of the 769 MEP speeches relied on economic arguments to explain their policy positions. The majority of these arguments were used by MEPs advocating international competitiveness gains through ambitious climate policy (60 percent), in accordance with the ecological modernization narrative (Bäckstrand & Lövbrand, Citation2019). An example was MEP Zorrinho’s (2017-10-03) description of the Paris Agreement as ‘creat[ing] new opportunities for sustainable growth and quality employment’. The opposite argument was made by MEP Obermayr (2011-11-15): ‘We must not allow Europe to impose restrictions on its own industry and, at the same time, to help finance coal-fired power stations in China and India’. Comparing the two legislative terms, the use of economic arguments remained stable (2009–2014: 60.2 percent vs. 2014–2019: 59.9 percent ‘gain competitiveness’) (Appendix III, Graph A4).

Overall, we found a bifurcation between ALDE, EPP, Greens/EFA, GUE/NGL and S&D who used arguments of competitive advantages through climate policies opposed by ECR, EFD(D), ENF and NI who justified low ambitions with the concern to risk competitiveness (Appendix III, Graphs A5, A7). The latter groups also used economic arguments most often of all three global shift arguments (Appendix III, Graph A6). In comparison to the other two shifts, the EP was most evenly split (60 percent ‘gain’ vs. 40 percent ‘risk’) on the topic of economic competitiveness (Appendix III, Graph A8).

It comes as little surprise that the ‘risk competitiveness’ argument was mostly used by MEPs calling for low ambition of EU global climate action (60.3 percent, see ). The other almost 40 percent of MEPs expressing competitiveness concerns, however, called for ambitious EU climate action globally. As such, they did not reject ideas of ecological modernization but were wary of international competition by countries less ambitious than the EU, making ambitious policy conditional on international climate cooperation. For example, MEP Urutchev (2015-01-28) stated: ‘This calls for the Paris 2015 roadmap to at least pay equal attention to successfully making realistic and comparable commitments from major global polluters, and also to protecting EU interests from undue burden on the industry’.

Emissions-related arguments

Overall, arguments referring to GHG emissions and responsibility for climate action were most prevalent (67.6 percent) among the three global shifts. The dominant argument was that the EU is responsible to act (80.2 percent), while 19.8 percent of MEPs argued that other global players are more responsible. Among those MEPs who stressed the EU’s responsibility to act, two lines of argumentation were found. MEPs argued for the EU to act because of its ‘historic responsibility’ (2012-11-21 Lepage) and independently of other countries, while other MEPs emphasized that EU action should be contingent on the action of other countries. On the emissions-related arguments, MEPs’ policy positions slightly changed over time with 76.9 percent of MEPs in the 2009–2014 term and 82.7 percent in the 2014–2019 term perceiving the EU as responsible for acting on climate change (Appendix III, Graph A9). This continuity despite the electoral changes is due to changes in the ECR, EPP and GUE/NGL political groups: More members of those political groups perceived the EU as responsible in the 2014–2019 term than in 2009–2014 (Appendix III, Graphs A9-11). Electoral changes were cushioned by moves within the political groups, which led to more continuity than expected and even a slight increase in ambitions.

Among the political groups, we again found a substantial bifurcation along the same lines as for the economic arguments. ECR, EFD(D), ENF and non-attached MEPs perceived the EU as less (or not) responsible for acting on climate change due to its GHG emissions, while ALDE, EPP, Greens/EFA, GUE/NGL and S&D perceived a clear responsibility for the EU to act on climate change (Appendix III, Graph A10). The EPP slightly stands out as more fragmented and the least cohesive group on this matter. 21.4 percent of EPP MEPs questioned whether the EU is primarily responsible to act; however, this percentage decreased in the 2014–2019 legislature (Appendix III, Table 12, Graph A11). An example for such arguments is EPP MEP Seeber (2010-01-20) stating: ‘[W]e are always emphasising the fact that we are the ones who want to take a leading role in the global fight against climate change. Why should this be? […] [W]ith our 14% CO2 emissions, we are not among the largest emitters’.

Confirming our expectations, MEPs who used the ‘EU less responsible’ argument more often call for low FCP ambitions (53.4 percent), whereas the ‘EU responsible’ argument was used to call for more EU ambition (99.5 percent), as illustrates. Surprisingly, 46.6 percent of those MEPs perceiving the EU as less responsible than others still called for high ambition. MEPs stressing conditionality of EU action used this argument, as for example MEP Zanicchi (2009-11-24): ‘Europe has always taken a leading role (…) the United States, China, India, Russia and Brazil must also assume their responsibilities, as countries that are major polluters’. The explanation is similar to the economic arguments made by ‘high ambition’ MEPs, who argue that the EU alone cannot address climate change and therefore emphasize conditionality. In conclusion, we found arguments pertaining to emissions-related responsibility – as the most prevalent theme in the debates – to substantially shape MEPs’ positions on EU FCP ambitions. Argumentative divides could be found across party lines as well as within the EPP.

Geopolitical arguments

The second most prevalent global shift in MEPs’ arguments (63.9 percent) relates to the extent to which the EU is influential in global climate politics. MEPs either perceived the EU as being a side-lined global player (e.g., ‘the EU was virtually inaudible during the final negotiations’, 2010-01-20 Grossetête) or as a leader (e.g., ‘Europe plays a strong leading role’, 2009-11-24 Gerbrandy).

Contrary to the other global shifts, the geopolitics arguments were not used in a bifurcated manner, polarizing among MEPs. The variance across political groups did not split them in two clear camps; instead, positions aligned towards the perception of the EU as a leader (91.9 percent). The only exception is the ENF group, which consistently used the ‘side-lined’ argument to justify their predominant position of low EU ambition. All other political groups emphasized the EU’s leadership and only occasionally perceived the EU as internationally side-lined (Appendix III, Graphs A12-13). MEPs from these groups seemed to agree on the ideal that the EU is relevant in global (climate) politics – be it by simply sitting at the table or by leading through ambitious action.

In contrast to the two other global shifts, there were disparities between the 2009–2014 and 2014–2019 legislative terms pertaining to the geopolitics arguments (Appendix III, Graphs A13-14). MEPs’ perceptions of the EU as a leader clearly increased. This reflects the substantive advancements in EU climate diplomacy and EU FCP since applying a more successful outreach strategy starting in the 2010s (Bäckstrand & Elgström, Citation2013; Oberthür & Dupont, Citation2021; Walker & Biedenkopf, Citation2018). Furthermore, the growing reference to EU leadership coalesced with the growing external polarization trend (Appendix III, Graph A14). This could be a counter-reaction by MEPs to international developments that contest the norms and goals set by the Paris Agreement, such as the election of US President Trump.

According to our expectations, the argument that the EU is side-lined was most prevalent among MEPs calling for low EU ambition, whereas the EU leadership argument clearly dominated among those calling for high EU ambition (see ). Yet, 69.8 percent of those MEPs perceiving the EU as side-lined in global geopolitics, still promoted an ambitious FCP. This argumentative pattern was used by MEPs who criticized the EU for not being able to play a significant-enough role in climate politics and called for it to play a more central role – for example by MEP Gerbrandy (2010-01-20): ‘[U]nfortunately, the giants – the United States, China, India, Brazil – were not joined by a European giant in Copenhagen’. While we found support for our expectation that geopolitics impact MEPs’ FCP ambitions (due to its overall prevalence in the dataset), we found less polarization across party lines than expected. Instead, our findings indicate a surprising consensus on the EU’s significant geopolitical role, which has grown between 2009 and 2019.

Discussion

When considering all MEPs together, we found surprising stability in their FCP ambition between 2009 and 2019, despite the 2014 European election results and changing international politics. Yet, through our qualitative analysis, we observed changes in MEPs’ argumentation and justifications linking international polarization trends to their support for (un)ambitious FCP. While the influence of other factors outside the scope of this study cannot be entirely excluded, evidence from MEP speeches showed that ambition changes correspond to the dual and intertwined polarization trends. The overall stability of MEPs’ FCP ambition emerged from the two largest political groups being more active in FCP debates, while the right-wing and Eurosceptic political groups that gained seats in the 2014 election were less vocal (EFD(D) and ENF) or more vocal but had changed to more support for high ambitions (ECR). Overall, MEPs have thus far weathered growing polarization.

Our findings show that in foreign policy, MEPs follow the tradition of advocating ambitious climate policy. In contrast to the analysis of votes or resolution texts, our qualitative analysis of speeches offers further nuance to the EP’s changing environmental/climate championship (Burns et al., Citation2013, p. 953). While the EP’s increased inter-institutional cooperation with the Council and Commission can explain why its resolutions and tabled amendments, over time, have taken a more moderate tone (Burns, Citation2019; Burns et al., Citation2013; Burns & Tobin, Citation2020; Delreux & Burns, Citation2019), plenary speeches represent the opportunity for MEPs to make public declarations, attract attention and profile themselves. They reflect individuals’ positions rather than the collective compromises found in joint EP resolutions.

Despite the overall stability, our analysis reveals significant polarization across political groups: ALDE, EPP, Greens/EFA, GUE/NGL and S&D build a discursive group that advocates high EU FCP ambition. ECR, EFD(D), ENF and NIs form a second discursive group pursuing low ambition. This discursive divide can also be found in the arguments based on economic and emissions-related global shifts, though no clear bifurcation can be identified in arguments based on geopolitical shifts (Appendix III, Graphs A5, A10, A12). Perception of the EU’s relevance in the global arena rather transcends almost all political groups. The low-ambition discursive group argues fundamentally different from the high ambition group in relation to the global shift in emissions. They perceive the EU to have little responsibility for global emissions and, hence, climate action. On this aspect, the EPP partially breaks out of its discursive group due to fragmentation on the question of who is responsible to act on climate change, illustrating a lack of cohesion on this matter. This could mean that in FCP debates, which strongly relate to responsibility for causing and addressing climate change, mainstream groups could struggle finding a majority.

International polarization spurred the fear that non-EU countries will fail to increase their climate ambitions and, as a consequence, negatively affect EU competitiveness. As expected, this argument is used by those MEPs who advocate low EU ambition. Contrary to our expectations, it is also used by MEPs who argue in favour of high EU ambition and shaping international climate politics. Consequently, external polarization gave rise to two opposing argumentations. First, the low-ambition group justified its position by arguing for aligning with international dynamics. Inversely, the high-ambition group remained supportive of an actively leading EU role in international climate policy, but they would not maintain EU ambition at any cost, given growing international polarization.

Our findings show that, in response to international polarization, MEPs increasingly demand harder measures in EU FCP. We detect the addition of a coercive perspective to the portrayal of the EU as a ‘leadiator’ (Bäckstrand & Elgström, Citation2013), as MEPs call for the use of conditionality and border measures as a coercive tool. One example is MEP De Veyrac (2009-11-24, emphasis added): ‘That is why, if other industrialised and emerging countries do not wish to assume their share of the responsibility, they will have to accept the full consequences of this in the form of the introduction of a tax at our borders’. The harsher context of international polarization seems to trigger a stronger EU response in the form of not only persuading non-EU countries through discursive, but also through conditional means.

Conclusions

MEPs were surprisingly stable in their overall support for ambitious FCP during the 2009–2019 timeframe, despite the increased shares of climate sceptic and Eurosceptic MEPs. Yet, discourses and perceptions that underlie this position have changed. Our study provides new qualitative insights into the impact that internal and external polarization trends have had on individual MEPs’ ambitions and, by extension, the political groups’ and the overall EP’s FCP position between 2009 and 2019.

Increased socio-political divisions within Europe reflected in the 2014 election results did not translate into significantly lower support for ambitious FCP. Yet, within the EP there are substantial differences in the way MEPs across political groups perceive FCP, with the exception of EU geopolitical leadership. Regardless of political group and support for high or low ambitions, a great number of MEPs perceive the EU as a global (climate) leader, a perception that has increased over the studied 2009–2019 period. International climate polarization, which we disentangled into global economic, emissions-related and geopolitical shifts, impacted MEPs’ justification of their FCP position. High ambition is generally justified by the EU’s responsibility to act on climate change, given its significant carbon footprint. Fears about losing competitiveness are voiced by MEPs to justify both reactive low ambition and proactive high ambition behaviour. Concern for negative impacts of external polarization led to growing calls for conditional FCP and border measures among those MEPs who support high ambition, reflecting a changing vision on the policy measures the EU should take.

In 2019, a new Parliament was elected, which increased fragmentation even more, continuing the internal polarization trend. Losses by the EPP and S&D were partially compensated by the Greens/EFA and Renew Europe’s (formerly ALDE) gains, suggesting a continuation of the trend that we identified. Yet, the EPP’s relative fragmentation on the EU’s international responsibility for addressing climate change points to a potential weak spot of the high-ambition group. During the 2009–2019 period, the low-ambition group was relatively silent, explaining why the majority of high ambition speeches remained stable. Yet, these dynamics could change: Increasing salience of climate policy in public discourse could lead to growing vocalness of the climate-sceptic groups.

While we find stable support for ambitious FCP, the EU’s current ambition is not sufficient to achieve the Paris Agreement's goals. Support of ambitious FCP by individual MEPs, political groups and, by extension, the entire EP has therefore failed to result in the level of ambition that is required. Yet, the von der Leyen Commission’s European Green Deal, the EP’s October 2020 push for a 60 percent GHG reduction target by 2030 and the December 2020 European Council endorsement of a binding 55 percent reduction target are steps towards addressing this ambition gap.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (635.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all 15 student assistants who helped us translate the plenary speeches and Elke Cloetens for helping us with the inter-coder reliability of our analysis. We also are very grateful for the valuable comments and support by the special issue editors. Moreover, we want to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. We tremendously benefitted from discussions at the 2019 GOVTRAN workshop in Rome, the 2019 ECPR General Conference and the 2020 ECPR Joint Sessions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Franziska Petri

Franziska Petri is a FWO doctoral fellow at the Leuven International and European Studies (LINES) at the University of Leuven.

Katja Biedenkopf

Katja Biedenkopf is Associate Professor of Sustainability Politics at the Leuven International and European Studies (LINES) at the University of Leuven.

References

- Bäckstrand, K., & Elgström, O. (2013). The EU’s role in climate change negotiations: From leader to ‘leadiator’. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(10), 1369–1386. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.781781

- Bäckstrand, K., & Lövbrand, E. (2019). The road to Paris: Contending climate Governance discourses in the post-Copenhagen Era. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1150777

- Biedenkopf, K. (2015). The European Parliament in EU external climate governance. In S. Stavridis, & D. Irrera (Eds.), The European Parliament and its international relations (pp. 92–108). Routledge.

- Biedenkopf, K. (2019). The European Parliament and international climate negotiations. In K. Raube, M. Müftüler-Baç, & J. Wouters (Eds.), Parliamentary cooperation and diplomacy in EU external relations. An essential companion (pp. 449–464). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Biedenkopf, K., & Walker, H. (2016). Playing to one’s strengths: The implicit division of labor in US and EU Climate Diplomacy (AICGS Policy Report No. 64). Johns Hopkins University.

- Bowler, S., & McElroy, G. (2015). Political group cohesion and ‘hurrah’ voting in the European parliament. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(9), 1355–1365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1048704

- Burns, C. (2019). In the eye of the storm? The European Parliament, the environment and the EU’s crises. Journal of European Integration, 41(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1599375

- Burns, C., Carter, N., Davies, G. A. M., & Worsfold, N. (2013). Still saving the Earth? The European Parliament's Environmental record. Environmental Politics, 22(6), 935–954. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2012.698880

- Burns, C., & Tobin, P. (2020). Crisis, climate change and comitology: Policy dismantling via the backdoor? Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(3), 527–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12996

- Buzogány, A., & Ćetković, S. (2021). Fractionalized but ambitious? Voting on energy and climate policy in the European parliament. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918220

- Delreux, T., & Burns, C. (2019). Parliamentarizing a politicized policy: Understanding the involvement of the European Parliament in UN climate negotiations. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2093

- de Wilde, P., Leupold, A., & Schmidtke, H. (2016). Introduction: The Differentiated politicisation of European governance. West European Politics, 39(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1081505

- Forchtner, B. (2019). Climate change and the far right. WIRES Climate Change, 10(5), e604. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.604

- Global Carbon Atlas. (n.d.). Global and country level CO2 emissions (2019). http://www.globalcarbonatlas.org/en/CO2-emissions.

- Groen, L., & Niemann, A. (2013). The European Union at the Copenhagen climate negotiations: A case of Contested EU actorness and effectiveness. International Relations, 27(3), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117813497302

- Hess, D. J., & Renner, M. (2019). Conservative political parties and energy transitions in Europe: Oppositions to climate mitigation policies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Review, 104, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.019

- Hix, S., Noury, A. G., & Roland, G. (2009). Democratic politics in the European Parliament. Cambridge University Press.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2015). The 2014 European Parliament election: Divided in unity? Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(S1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12264

- Hodson, D., & Puetter, U. (2019). The European Union in disequilibrium: New intergovernmentalism, postfunctionalism and integration theory in the post-Maastricht period. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1153–1171. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1569712

- Huber, R., Maltby, T., Szulecki, K., & Ćetković, S. (2021). Is populism a challenge to European energy and climate policy? Empirical evidence across varieties of populism. Journal of European Public Policy . https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918214

- Ikenberry, G. J. (2018). The end of liberal international order? International Affairs, 94(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix241

- Jackson, K., & Bazeley, P. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. SAGE Publications.

- Keukeleire, S., & Delreux, T. (2014). The Foreign Policy of the European Union (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lockwood, M. (2018). Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: Exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics, 27(4), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. SSOAR. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

- McCright, A. M., Dunlap, R. E., & Marquart-Pyatt, S. T. (2016). Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Environmental Politics, 25(2), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2015.1090371

- Oberthür, S., & Dupont, C. (2021). The European Union’s international climate leadership: Towards a grand climate strategy? Journal of European Public Policy . https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918218

- Petri, F., & Biedenkopf, K. (2020). Common but differentiated responsibility in International climate negotiations: The EU and its contesters. In E. Johansson-Nogués, M. C. Vlaskamp, & E. Barbé (Eds.), European Union contested: Foreign policy in a changing world (pp. 35–54). Springer International Publishing.

- Raube, K., Müftüler-Baç, M., & Wouters, J. (2019). Parliamentary cooperation and diplomacy in EU external relations. An essential companion. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Raunio, T., & Wagner, W. (2020). Party politics or (Supra-)national interest? External Relations votes in the European parliament. Foreign Policy Analysis, 16(4), 547–564. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/oraa010

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (n.d.). CO2 emissions. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions#cumulative-co2-emissions.

- Sabatier, P. A. (1993). Policy change over a decade or more. In P. A. Sabatier, & H. C. Jenkins-Smith (Eds.), Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach (pp. 13–39). Westview Press.

- Stavridis, S., & Irrera, D. (2015). The European Parliament and its International Relations. Routledge.

- van Asselt, H., & Brewer, T. (2010). Addressing competitiveness and leakage concerns in climate policy: An analysis of border adjustment measures in the US and the EU. Energy Policy, 38(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.08.061

- Vogel, D. (2012). The Politics of Precaution. Regulating Health, Safety, and Environmental Risks in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press.

- von Homeyer, I., Oberthür, S., & Jordan, A. J. (2021). EU climate and energy governance in times of crisis: Towards a new agenda. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918221

- Walker, H., & Biedenkopf, K. (2018). The historical evolution of EU climate leadership and four scenarios for its future. In S. Minas, & V. Ntousas (Eds.), EU Climate Diplomacy: Politics, Law and Negotiations (pp. 33–46). Routledge.

- Wendler, F. (2019). The European Parliament as an arena and agent in the politics of climate change: Comparing the external and internal dimension. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2156

- World Bank. (n.d.). GDP (current US$), World and European Union. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=EU.