ABSTRACT

Analysing roll call votes from the energy and climate policy field in the Eighth European Parliament (2014–2019), this article asks why has the European Parliament succeeded in maintaining its relatively ambitious position and how national and partizan factors explain voting behaviour of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) on EU energy and climate legislation. We find the Eurosceptic vs. pro-EU cleavage to be the main conflict line structuring voting on energy and climate policy. Additionally, EU energy and climate policy has been supported by MEPs from member states with a track record of more ambitious climate policymaking and those with higher energy dependence. We show that increasing party fragmentation in the European Parliament has strengthened the influence of some progressive party groups, particularly the Greens, and has enhanced the European Parliament’s ability to mobilize support for a relatively ambitious energy and climate legislation.

Introduction

Despite multiple crises facing the European integration project in the recent past (see von Homeyer et al., Citation2021), the European Union’s (EU) energy and climate policy (ECP) has shown remarkable signs of vitality. Against modest expectations, the ECP framework for 2030 has brought important improvements that exceeded initial prospects regarding both the legislative scope and the level of ambition (Oberthür, Citation2019; Wettestad & Jevnaker, Citation2019). Alongside the major reform of the European Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and other important legislative acts in the area of ECP, in 2018 the EU adopted new goals for renewable energy development and energy efficiency which were notably higher than what was agreed in the European Council in 2014 (Ćetković & Buzogány, Citation2019). This article explores the role of the European Parliament (EP) in this process by unpacking the political coalitions and motives driving Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) to support (or reject) key pieces of EU energy and climate legislation.

Much of the relevant scholarship has argued that the EU has an in-built self-reinforcing mechanism facilitating ‘races to the top’ among member states and EU institutions – eventually leading to increased ambitions (Schreurs & Tiberghien, Citation2007). In this context, the EP has often been regarded as an ‘environmental champion’ and as a key facilitator of the deepening and widening of ECP not only within the EU, but also at the global level (Burns, Citation2012; Judge, Citation1992). This has been paralleled by the continuous empowerment of the EP as a co-legislator in ECP-related areas (Bocquillon & Maltby, Citation2020). More recently, however, the EU’s multiple crises, including the rise of Eurosceptic and populist parties and governments, are suspected to negatively influence the EP’s progressive role concerning ECP and to lead to policy disintegration and dismantling (Lenschow et al., Citation2020; see also Huber et al., Citation2021; Petri & Biedenkopf, Citation2021). Existing research has so far remained cautious in this regard suggesting that the EP's leadership in scaling up EU ambitions in the broader field of environmental policy has not been substantially affected (Burns, Citation2019). Less is known, however, about the ability of the increasingly fractionalized EP to build majorities and negotiate ambitious legislation in the ever more important field of energy and climate. What is known from the literature is that voting behaviour in the EP is characterized by high levels of cohesion and a consensus-seeking culture among the largest European Party Groups (EPGs) (Hix et al., Citation2007; Ripoll Servent & Roederer-Rynning, Citation2018). Despite various rounds of enlargement, EP voting continues to be shaped mainly by partizan rather than national affiliations (Raunio & Wagner, Citation2020). At the same time, next to the traditional left-right cleavage, the pro-/anti-EU conflict line has been gaining importance in various policy fields (Chiru & Stoian, Citation2019). The extent to which these cleavages found in other policy fields also apply to ECP, and the implications this has for further integration, has remained unexplored. A notable exception is a study by Zapletalová and Komínková (Citation2020) which focuses on MEPs from the four Visegrad countries and suggests that while MEPs from this region increasingly object to ECP, their cohesion appears to be weak and that ad hoc national concerns are shaping their voting behaviour.

Building on this literature, we examine the effects of socio-political divisions within and across EU member states on voting behaviour and coalition-building in the EP in the area of ECP. It is reasonable to expect that, as ECP has become more tangible in its distributive effects and as Eurosceptic and populist parties have increased their presence in the EP, the ability of EPGs to reach common positions on ECP has become increasingly difficult. However, rising polarization and fragmentation in the EP might have also facilitated more ambitious decision-making on ECP, as has been witnessed in some member states (Ćetković & Hagemann, Citation2020). Against this background, the article asks why MEPs support ECP, which coalitions among EPGs have emerged and what lessons can be learnt from this for the future role of the EP in ECP.

Focusing on major legislative acts in the Eighth EP (2014–2019), we find that although the EP's decisions on ECP have continued to secure broad cross-party support, the liberal (ALDE/ADLE) and the green (Greens/EFA) party groups have increasingly served as kingmakers providing essential majorities for contested pieces of legislation to pass. This suggests that the polarization within the EP and the declining power of the centrist political block has not hindered majority-building in support of EU ECP. Overall, while the left-right division remains relevant in voting on ECP, the pro-EU vs. anti-EU conflict line has emerged as an even more important cleavage.

Our findings hold theoretical and policy-relevant implications for the literature on the crises’ impact on ECP (see, e.g., Burns et al., Citation2018; Lenschow et al., Citation2020). In contrast to the dominant view regarding the negative impact of polarization and climate policy (Dunlap et al., Citation2016), we show that in multiparty systems polarization does not necessarily lead to policy disintegration. We also contribute to the scholarship on spatial and ideological cleavages in the EP (Otjes & van der Veer, Citation2016) and on intra-institutional decision-making in the EU (Mühlböck, Citation2012). Our work adds to these literatures an explicitly ECP-related perspective that broadens Zapletalová and Komínková’s (Citation2020) focus on Visegrad MEPs and analyses voting behaviour of all MEPs on key pieces of ECP legislation. In addition, we enrich the literature on the policy implications of the rise of populist and Eurosceptic parties for the decision-making in the EP (Behm & Brack, Citation2019) by providing an account of the increasingly prominent – and contested – field of ECP.

In what follows, we first review the literature on voting behaviour in the EP and formulate hypotheses focusing on MEPs’ national and partizan affiliations. Subsequently, we present our research design and methodology. The following section details the results of the descriptive and statistical analysis related to party group cohesion and voting behaviour. In the concluding part, we discuss the main findings as well as the theoretical and policy-related lessons which follow from our analysis.

Member states and political parties in EU energy and climate policy

A number of different explanations have been put forward in the literature as to why the EU’s ECP has progressed despite all odds during the last decades. According to the neo-functionalist explanation, the pro-active regulatory nature of the European Commission has played a central role in bringing EU policies forward in this field (Bürgin, Citation2020). In particular, the innovative framing of the ‘energy trinity’, composed of competitiveness, security and sustainability, has allowed the Commission to act as an agenda-setter and convincingly push for more integration (Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2016). By contrast, the intergovernmental explanation maintains that delegation of sovereignty to the EU level in a policy field that is so close to ‘high politics’ can only go as far as member states agree upon. This explains difficulties in policy implementation and the oftentimes fierce opposition arising from domestic vested interests against the further expansion of EU ECP, e.g., when it came to more ambitious post-2020 policy targets (Solorio & Jörgens, Citation2020). Equally, according to the ‘new intergovernmentalist’ perspective the newly found ambitiousness regarding ECP can be explained by some member states’ increasing assertiveness (Thaler, Citation2016; but see Bocquillon & Maltby, Citation2020).

While the Commission and, respectively, the Council are at the heart of these two explanations, the EP’s role is somewhat more ambivalent. MEPs represent their voters and are directly elected at the member state level. This makes them subject to a set of complex delegation and accountability chains. As the literature on voting behaviour in the EP highlights, MEPs have to balance a number of (potentially) conflicting considerations when making their voting decisions and take into account their constituencies (voters), their national parties as well as their EPGs (Mühlböck, Citation2012). Our analysis aims to understand the role of such strategic considerations influencing MEPs’ voting behaviour on ECP-related legislation. We first explore the argument about the cohesiveness of EPGs in ECP and then discuss two main sets of factors affecting MEPs’ voting behaviour – national/regional cleavages and party positions.

Party group cohesion

The literature on the EP has documented that MEPs usually vote along EPG lines, rather than national ones (Raunio & Wagner, Citation2020). This has been interpreted as a sign of the EP becoming a ‘normal’ parliament and there are different views as to why this has been the case (Hix et al., Citation2007; Judge & Earnshaw, Citation2008; Ripoll Servent & Roederer-Rynning, Citation2018). One view stresses that EPGs have strengthened their control of MEPs, while the ideological coherence of political parties forming EPGs has also increased. Institutional reforms, such as the growing powers of the EP as a co-legislator, have also contributed to more loyalty towards EPGs. Other perspectives on party group cohesion point to the lack of policy information available to individual MEPs when voting on a multitude of policy proposals upon which they lack expertise. This makes them receptive to voting instructions from their EPGs (Ringe, Citation2010). Over time, the EPGs, and the EP in general, have played an increasing role in allocating resources and controlling assignments to party offices, committees and rapporteurships (Hurka et al., Citation2015). Particularly the two largest EPGs, the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), have displayed high levels of internal cohesion. The literature also suggests that, given the rise of populist and other challenger parties in the EP, internal cohesion of the two major EPGs will additionally increase in order to secure the adoption of legislation, especially when votes are close (Ripoll Servent & Roederer-Rynning, Citation2018). We seek to test these propositions by focusing on twelve key ECP-related legislative acts that have important socio-economic implications and are thus suitable for such a test. Hence, our first two expectations are that:

H1a: MEPs follow the position of their EPG in voting on ECP legislation.

H1b: The EPP and S&D party groups demonstrate above-average cohesion on closer votes on ECP legislation.

National and regional cleavages

In contrast to studies pointing to high levels of EPG cohesion, other research underscores the importance of national-level variables to explain voting behaviour, especially when it comes to more salient policies. When national interests are at stake, political parties increase pressure on MEPs to follow the (domestic) party line (Klüver & Spoon, Citation2015). In the EU’s bicameral political system, the Council and the EP are interlinked through government parties, which are present in both bodies. While in the case of highly salient policies all MEPs may be more likely to support their government’s than their EPG’s position, this effect is stronger for MEPs from governing parties (Costello & Thomson, Citation2016). Governing parties hold direct influence over their MEPs and are thus better equipped to exert pressure on voting behaviour on legislation regarded as particularly salient. The literature also suggests that MEPs from different member states vary in how much they support their government’s position, with MEPs from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) being more likely to follow their EPG’s line (Meyerrose, Citation2018). Related to our focus on ECP, however, the literature on the Counciĺs decision-making shows that the level of conflict along the East–West divide is higher on ECP than in other policy fields (Toshkov, Citation2017). Case studies also suggest that the Visegrad countries, and Poland in particular, often act as ECP laggards opposing stricter EU goals (Skjærseth, Citation2018). Drawing on this literature, we expect that:

H2: MEPs from CEE countries are more likely to oppose ECP legislation.

H3a: MEPs from governing parties are more likely to align with the voting behaviour of their ministers in the Council.

H3b: Opposition MEPs will vote against ECP legislation when such legislation is opposed by their ministers in the Council.

Party positions

A final group of expectations regarding MEPs’ voting behaviour focuses on policy positions of parties (Carter et al., Citation2018). Much of the recently emerging literature on populist parties and climate change policies shows that right-wing populist parties are particularly prone to oppose EU ECP (Schaller & Carius, Citation2019; see also Huber et al., Citation2021; Petri & Biedenkopf, Citation2021). There are two main explanations for this rejection: (1) economic fears associated with globalization and technological change and (2) rejection of transnational elites in general and of ‘elitist’ climate science in particular (Lockwood, Citation2018).

Other explanations of voting behaviour stress the importance of three dimensions of political conflict in the EU (Hooghe et al., Citation2002). The left-right dimension is often seen to play a central role in the EP, similarly to the national level. Leftist parties often hold more environmentally friendly positions than right-wing ones (Neumayer, Citation2004). The second dimension is the so-called GAL-TAN, or ‘new politics’ dimension, which captures conflicts related to post-materialistic values, including environmental protection. Because of their support for traditional values and national economies, TAN (Traditional, Authoritarian and National) parties are usually more likely to oppose ECP than GAL (Green Alternative Liberal) ones (Hess & Renner, Citation2019). The third dimension is structured around support for EU integration. The recent literature on the EP has emphasized the increasing relevance of this cleavage, especially following the financial crisis (Roger et al., Citation2017). Related to ECP, the literature argues that Eurosceptic parties regard these policies as part and parcel of the EU’s liberal and elite-based consensus and are often particularly critical of the transfer of decision-making authority beyond the national level which most of these policies imply (Herranz-Surrallés et al., Citation2020). Based on the discussion above, our final group of expectations can be formulated as follows:

H4a: MEPs from right-wing populist parties are more likely to vote against ECP legislation than MEPs from non-populist parties.

H4b: MEPs from parties with a Eurosceptic position are more likely to vote against ECP legislation than MEPs from parties with a pro-EU position.

H4c: MEPs from parties with a TAN ideology are more likely to vote against ECP legislation than MEPs from parties with a GAL ideology.

H4d: MEPs from parties with an economic right-wing ideology are more likely to vote against ECP legislation than MEPs from parties with an economic left-wing ideology.

Research design

We test the above hypotheses by analysing the voting behaviour of MEPs from the Eighth EP using roll-call votes (RCV) of ECP legislation through descriptive and statistical methods. RCVs are a specific form of voting and have to be demanded by an EPG (or by 40 individual MEPs) to be recorded. Normally, voting in the EP is made by show-of-hands and remains undocumented; only about one third of the votes cast are RCVs. While this might lead to selection biases when analysing this data, various studies show that the influence of strategic choices on calling the roll is negligible (see e.g., Hix et al., Citation2018). We focus on major legislative acts that belong to the core of EU ECP during the Eighth EP, including those regulating renewable energy promotion, energy efficiency, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, car emissions and dealing with the governance of the Energy Union (for the full list of the legislation included, see Table A1 in the Supplementary materials). All the RCVs selected were on the final texts of binding legislative acts in the area of EU ECP. While most of the decision-making takes place before the final votes in plenary sessions (Bowler & McElroy, Citation2015), the publicness of RCVs enables an analysis of MEPs’ position-taking, which is an equally important representation-related task.

In all twelve analysed legislative acts, the EP formulated the most ambitious position and negotiated a substantial increase in targets compared to those initially proposed by the Commission and those advocated by the Council. For instance, in the case of the Renewable Energy Directive, the Commission proposed, and the Council supported, the target of 27 per cent of renewable energy sources in the EU’s energy mix by 2030. The EP demanded a target of 35 per cent, and a 32 per cent target was eventually adopted by the Council and the EP (EP Legislative Train, Citation2019a). Similarly, in the negotiations on CO₂ emission standards for new passenger cars and vans, the Commission proposed a reduction target of 30 per cent by 2030 compared to 2021 and the Council supported a reduction of 35 per cent, whereas the EP advocated a 40 per cent reduction target. Eventually, a target of 37.5 per cent was adopted (EP Legislative Train, Citation2019b). The objective of our analysis is to reveal the political majorities in the EP supporting these ambitious legislative acts and clarify the factors that explain the likelihood of MEPs’ support for these decisions.

We follow standard research practice in the field by analysing RCVs using binary logistic regression.Footnote1 Our dependent variable is dichotomous: it takes the value 1 for ‘Aye’ votes and 0 for ‘Nay’ votes and abstentions. All twelve legislative acts were adopted in the EP at first reading, which requires a simple majority. Therefore, abstentions have the same effect as voting against, but absence does not influence the number of votes needed to adopt legislation, which is why absent votes are excluded from the analysis. The data on our dependent variable (MEPs’ voting behaviour) draws on votewatch.eu, an online watchdog organization that monitors voting in the EP and the Council. We are first interested in how cohesive national delegations and EPGs are and whether the cohesion of the two largest EPGs is particularly high when the voting results are close and the majority therefore less certain. To measure cohesion of EPGs, we use the Agreement Index by Hix et al. (Citation2007), which takes into account Aye, Nay and Abstain votes. The closer the index is to 1, the more MEPs of an EPG vote in a similar way; the closer it is to 0, the more they are divided.

In a second step, we conduct a statistical analysis to reveal the motivations behind the individual votes of MEPs. Independent variables regarding MEPs’ party membership, EPG and committee affiliation were extracted from the EP’s homepage. We combined this information with datasets containing information on party positions. To capture right-wing populist parties, we relied on PopuList, a recent authoritative categorization based on expert opinions (Rooduijn et al., Citation2019). The Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) was used to identify parties’ left–right, anti-/pro-integration and GAL-TAN positions (Polk et al., Citation2017). Parties in government, and thus with representation in the Council, were identified using the Parlgov database (Döring & Manow, Citation2012). Information on voting behaviour in the Council also comes from votewatch.eu. We identified salient policies by focusing on cases where government ministers have voted against or abstained in Council voting.

We control for several country- and individual-level factors. MEPs from member states with higher energy security concerns are expected to be more likely to support EU ECP legislation, as are MEPs from member states that have already carried out far reaching reforms in reducing their emissions. For the latter, the Climate Change Performance Index is used, which combines greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy, energy use, and climate policy indicators based on expert assessments (Germanwatch, Citation2014). We account for energy security considerations using Eurostat’s energy dependence index (Eurostat, Citation2019). In both cases, we use data for 2014, which is the last year before our investigation starts.

Individual-level expectations focus on MEPs’ characteristics as policy experts. As highlighted by informational theories of legislative organization, EPGs tend to have an effective division of labour and usually delegate policy experts into the relevant committees that play an important role in preparing resolutions for voting in plenary sessions (Ringe, Citation2010). As EPGs usually follow their committee members’ positions when issuing voting instructions, we expect MEPs from Industry, Research, Telecommunications and Energy (ITRE) and on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) committees to be more likely to support these policies.

Findings

In this section, we first descriptively present the data on the ECP-relevant voting in the EP and on dissenting votes of ‘rebel’ MEPs to provide a broader view on party cohesion (Hypotheses 1a-b) and national cleavages (Hypothesis 2), and then turn to multivariate analysis of key factors driving MEP voting behaviour to test our hypotheses statistically.

Descriptive results

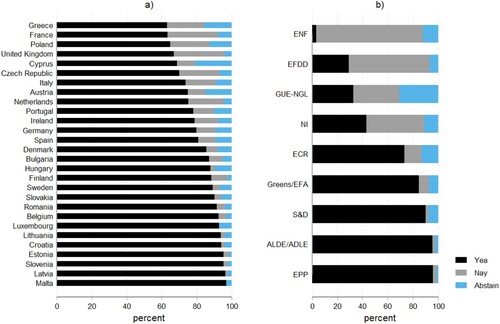

displays the distribution broken down by country and EPG, respectively. a shows that particularly MEPs from smaller EU Member States, like Slovenia, Malta, Belgium or Croatia display more than 80 percent of ‘Aye’ votes. Cypriot and Greek MEPs, together with French, British and Polish were among the most frequent ‘Nay’-sayers. There is no clear-cut East-West or North-South divide, with countries from all over the EU being quite evenly distributed among those opposing ECP. Altogether, we find high levels of support for ECP acts among MEPs. Among the CEE MEPs, Polish MEPs stand out as having supported less than 40 per cent of the examined legislative acts.

b presents the voting results broken down by EPGs. As expected, EPGs dominated by populist right-wing parties, as well as non-affiliated MEPs most frequently voted against ECP legislation. The GUE-NGL, which consists of more radical left-wing parties, such as the Spanish Podemos, has also often voted against ECP legislation, demanding more, not less, ambitious policies (see also Huber et al., Citation2021). On average, the two EPGs forming the ‘Grand Coalition’ (EPP and S&D) alongside the liberals (ALDE) and the Greens (Greens/EFA) most consistently supported ECP legislation,

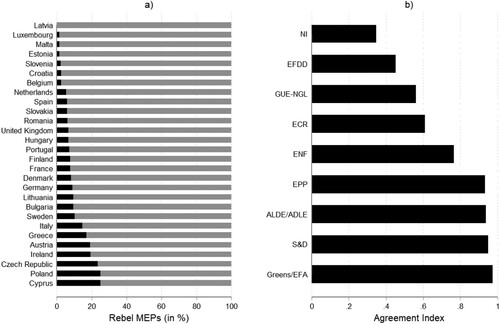

illustrates the level of dissent within the EP. From the country-level data in a, we see that there is a high internal party cohesion, with only Cypriot, Polish and Czech MEPs displaying a slightly stronger tendency to vote against their EPG’s political line. b shows high levels of cohesion across most EPGs, supporting the expectation H1a that parties will follow the position of their EPG. The share of ‘rebel’ MEPs dissenting from their EPG’s line is particularly high on the radical right-wing, with Nigel Farage’s Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) having the most dissenters. At the same time, ECP also proved to be divisive within the green GUE-NGL group, which has the second highest share of rebels. Interestingly, the Greens/EFA have exhibited the highest internal cohesion among all EPGs. This observation gains additional relevance as the two largest groups in the EP, EPP and S&D, could not provide the majorities needed for the adoption of ECP legislation and had to rely on the support of other EPGs, particularly ALDE/ADLE and Greens/EFA (see Online Appendix, Figure A1). For seven out of 12 legislative acts, the Greens provided the strongest support among all EPGs, while in two cases they provided the second strongest support. The Greens were thus instrumental in securing the majority for some of the key legislation on which the centre-right EPP was more reluctant, such asEmission Standards for Heavy-duty Vehicles (see Online Appendix, Figure A2).

We do not find evidence that the two major EPGs (EPP and S&D) exercise stronger pressure on their MEPs and secure higher internal cohesion in the case of close votes as expected in H1b. At the vote for the Effort Sharing legislation, which received the narrowest majority in the EP, the cohesion index for S&D was the lowest among all decisions in our sample (below 0.8). Likewise, EPP recorded a below-average cohesion index (slightly below 0.8) during the vote for the legislation on the Market Stability Reserve, which was the third least supported ECP legislation (see Online Appendix, Figure A3).

Who supports EU climate and energy policy?

We turn to the multivariate analysis of voting behaviour. The results are presented using odds ratios in order to ease interpretation. Odds ratios show that a one-unit increase in an independent variable leads to a change in the odds of an MEP voting ‘Aye’ equal to the odds ratio. shows the results of the binary logistic regression on determinants of MEP support for ECP resolutions. Overall, we find that populism and Euroscepticism are the most significant factors explaining the opposition of MEPs to ECP.

Table 1. Support for EU climate and energy policies in the 8th EP (Binary Logistic Regression).

H2 expected regional cleavages to play a role in the EP’s ECP-related decision-making. When comparing CEE MEPs’ voting behaviour with those from the ‘old’ Member States, we find the opposite effect, albeit not at a statistically significant level. As seen above, MEPs from the CEE states are quite evenly distributed over both supporting and opposing ECP. At closer inspection, the expected negative effect in the voting behaviour of CEE MEPs exists mainly in the case of Polish MEPs.

We find support for H3a concerning the interconnectedness of national and EU arenas in EP decision-making. MEPs from parties represented in the Council are more supportive of ECP. Furthermore, opposition voiced in the Council is often supported not only by governing party MEPs, but also by large parts of the opposition MEPs from the same country. Over 50 per cent of the opposition party MEPs in Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria and Hungary have supported their governments in rejecting ECP legislation (Online Appendix, Figure A4). This backs Hypothesis H3b and shows the existence of a broader national resistance against certain ECP legislation, albeit only in a few member states.

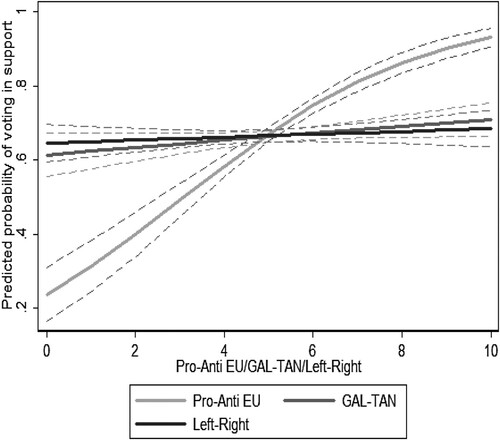

The hypotheses focusing on party positions (H4a-d) test the effect of different dimensions of party conflict on voting decisions in the EP. To start with, we find strong support for the expectation that radical right-wing populist MEPs would oppose ECP. Right-wing populist MEPs are more than three times more likely to vote against ECP legislation than other MEPs. A closer look at party positions shows that contestation is voiced predominantly by MEPs holding strong anti-EU stances. In contrast, we find that parties’ positioning on the new vs. old politics (i.e., GAL-TAN axis) and the left-right dimension is less important in explaining MEPs’ voting behaviour. To illustrate the effects of party positions on voting, we plot the predicted probabilities of support on parties’ left-right, pro- and anti-EU as well as the GAL-TAN positions. shows steeply increasing probabilities of support with increasing pro-EU positions but little influence of the economic left-right or the GAL-TAN dimension on voting on ECP matters.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of GAL–TAN, Left-Right and pro-EU/anti-EU position on the predicted probability of voting in support of EU ECP.

Our control variables concerning state-level policy differences in ECP also produce noteworthy effects. MEPs from countries with progressive climate policies are more likely to support ambitious ECP. With all other variables kept constant, we also find statistically significant support for EU ECP among MEPs representing countries with high levels of energy import dependency. By contrast, an MEP’s membership in a relevant committee does not have a significant effect on support for ECP.

Discussion and conclusions

This contribution has examined voting on ECP in the Eighth EP and asked how the EU’s polycrisis has influenced the EP's decision-making and coalition building. Focusing on the societal crisis manifested in fragmentation and polarization along national, ideological and party lines we have first shown that the EP indeed advocated ambitious goals in the negotiations with the European Commission and the Council across virtually all 12 studied ECP legislative acts. Only two legislative proposals were overwhelmingly rejected by Greens/EFA. For the remaining ten proposals Greens/EFA provided the largest or second-largest support among all EPGs, which speaks to the level of ambition of those policy proposals. Overall, our analysis shows that voting behaviour of the EP on ECP resembles what we know from other policy fields, but it also displays some unique features. It is the combination of these EP decision-making patterns and the specific nature of ECP that facilitated the EP's leadership role and holds the key to understanding the future of EU ECP. We elaborate below on the key explanatory dimensions of the EP's voting behaviour on ECP as well as their theoretical and policy implications.

Similar to other policy fields (Raunio & Wagner, Citation2020), the high internal cohesion of the major EPGs has played an important role in explaining support for ambitious ECP in an increasingly fractionalized and polarized EP. The two largest EPGs, alongside with Greens/EFA and ALDE/ADLE, have exhibited levels of internal cohesion of more than 90 per cent. Other EPGs, particularly those at more extreme right and left poles, have been much more internally divided on ECP voting. Large EPGs thus tend to mobilize support for the proposed legislation and strengthen the EP’s position vis-à-vis other EU institutions, even if they are not always fully supportive of all elements of the legislation. The high cohesion levels among the two largest EPGs, and particularly of the less ECP-enthusiastic EPP, can also be related to the fact that, although ambitious, the adopted ECP legislation constitutes a compromise and is seen by many observers as insufficient for properly addressing climate change (Climate Action Tracker, Citation2020). We also find that the two major EPGs tend to be more divided on close votes. This goes against expectations from the literature on the EP (Ripoll Servent & Roederer-Rynning, Citation2018) and suggests that high internal cohesion may be difficult to maintain as ECP becomes more ambitious in the future. At the same time, this does not necessarily threaten the EP's leadership role in the field of ECP. Following the 2014 EP elections, all mainstream EPGs, except for S&D, suffered a loss in their seat shares with EPP experiencing the largest decline. This has enabled progressive EPGs (S&D, ALDE/ADLE and Greens/EFA) to perform a more pivotal role in building majorities for ECP. This trend is likely to accelerate during the ninth EP, in which the EPP and S&D combined lost 65 seats while ALDE/ADLE (now Renew Europe) and Greens/EFA together gained 61 seats.

National concerns have influenced MEPs’ voting behaviour, but less significantly than one may expect. Our results from the EP fail to provide unequivocal support for claims of a growing East-West cleavage in EU policy-making on ECP (Wurzel et al., Citation2019). While particularly Polish and Czech MEPs have indeed been among the most frequent opponents of ECP, MEPs from other CEE states have in general remained quite supportive. This suggests that the East-West divide in ECP is more a Polish-EU, and to a lesser extent a Visegrad-EU, problem, in line with the ‘Polonization’ claim made in the implementation literature (Skjærseth, Citation2018). Importantly, however, the bicameral dynamics between the Council and the EP show that opposition voiced in the Council is connected with dissent in the EP. Opposition MEPs from Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary or Austria have often sided with government parties in contesting the ECP. This suggests the existence of a broad cross-party coalition on certain pieces of EU ECP which is likely to persist also after changes in government.

Our findings also provide evidence that MEPs’ voting behaviour on ECP is best explained by the pro-EU/anti-EU cleavage, in contrast to the GAL-TAN and the left-right cleavages, which have structured conflicts in the EP over the last decades. This corroborates recent findings highlighting the increasing relevance of sovereignty-related conflicts in the EU compared to traditional cleavages (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018). These conflicts are particularly salient in ECP which often challenge traditional conceptions of sovereignty (Lockwood, Citation2018). Contextual factors offer further explanations of why national delegations in the EP are more or less supportive of EU ECP. We find that MEPs from member states with high levels of energy dependence and progressive climate policy records are more supportive of the development of a common ECP. These findings show the lasting importance of the multilevel leader-laggard dynamics in EU climate policymaking (Schreurs & Tiberghien, Citation2007) and highlight the role of national-level variables also for the EP.

In sum, we find that even though the importance of the pro-EU vs. anti-EU conflict line shows the effects of the EU polycrisis on ECP, the EP has succeeded in mobilizing broad support for this policy field. As EU policies addressing climate change will have to become more ambitious in the future, they can count on support from socio-culturally progressive MEPs and MEPs from member states which have been leaders in decarbonization or are likely to benefit from EU climate policy efforts in the future. But the fate of increasingly ambitious EU ECP will also depend on more conservative MEPs from mainstream parties in large member states and their political will to abandon support for domestic fossil-fuel industries. Future research should address how these conflicts are settled before bills get to the EP’s floor and how changing domestic configurations of power shape MEPs’ positions. The rise of climate activism associated with the Fridays for Future movement and its support for a far-reaching and progressive Green New Deal, but also the subsequent Covid-19 crisis, call for studies that examine the policy-specific responsiveness of MEPs to their (real or imagined) constituencies.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (205 KB)Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at a workshop organized under the auspices of the Jean-Monnet Network ‘Governing the EU’s Climate and Energy Transition in Turbulent Times’ (GOVTRAN) in Rome, the ECPR’s General Conference in Wrocław and the ‘OSI-bag’ Comparative Politics Colloquium at Freie Universität Berlin. We thank participants of these events, the journal’s reviewers, the three editors of the Special Issue for their helpful comments and Lauren Goshen for her editorial assistance. Aron Buzogány acknowledges support through the Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation Visiting Fellowship at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of the Johns Hopkins University, Washington, D.C. Open access funding was generously by provided by the GOVTRAN network (600328-EPP-1-2018-1-BE-EPPJMO-NETWORK).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aron Buzogány

Aron Buzogány is a Senior Researcher at the Institute of Forest, Environmental, and Natural Resource Policy, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU), Vienna, Austria.

Stefan Ćetković

Stefan Ćetković is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Bavarian School of Public Policy at the Technical University of Munich, Germany.

Notes

1 While the data structure might call for multilevel analysis as MEPs are nested in parties, which are nested in countries, the intra-class correlation test, which shows the correlation of the observations within a cluster, showed that this is not necessary (ICC= 0.05).

References

- Behm, A.-S., & Brack, N. (2019). Sheep in wolf’s clothing? Comparing Eurosceptic and Non-Eurosceptic MEPs’ parliamentary behaviour. Journal of European Integration, 41(8), 1069–1088. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1645845

- Bocquillon, P., & Maltby, T. (2020). EU energy policy integration as embedded intergovernmentalism: The case of Energy Union governance. Journal of European Integration, 42(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708339

- Bowler, S., & McElroy, G. (2015). Political group cohesion and “hurrah” voting in the European Parliament. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(9), 1355–1365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1048704

- Bürgin, A. (2020). The impact of Juncker's reorganization of the European Commission on the internal policy-making process: Evidence from the Energy Union project. Public Administration, 98(2), 378–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12388

- Burns, C. (2012). The European parliament: The European Union’s environmental champion? In A. Jordan, & C. Adelle (Eds.), Environmental Policy in the European Union (pp. 132–152). Earthscan.

- Burns, C. (2019). In the eye of the storm? The European Parliament, the environment and the EU’s crises. Journal of European Integration, 41(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1599375

- Burns, C., Tobin, P., & Sewerin, S. (2018). The impact of the economic Crisis on European environmental policy. Oxford University Press.

- Carter, N., Ladrech, R., Little, C., & Tsagkroni, V. (2018). Political parties and climate policy: A new approach to measuring parties’ climate policy preferences. Party Politics, 24(6), 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817697630

- Ćetković, S., & Buzogány, A. (2019). The political economy of EU climate and energy policies in Central and Eastern Europe revisited: Shifting coalitions and prospects for clean energy transitions. Politics and Governance, 7(1), 124–138. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i1.1786

- Ćetković, S., & Hagemann, C. (2020). Changing climate for populists? The impact of populist radical-right parties on low-carbon energy policies in Western Europe. Energy Research & Social Science, Online First.

- Chiru, M., & Stoian, V. (2019). Liberty: Security dilemmas and party cohesion in the European parliament. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(5), 921–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12852

- Climate Action Tracker. (2020). EU summary. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/eu/

- Costello, R., & Thomson, R. (2016). Bicameralism, nationality and party cohesion in the European parliament. Party Politics, 22(6), 773–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068814563972

- Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2012). Parliament and government composition database (ParlGov). v12(10).

- Dunlap, R. E., McCright, A. M., & Yarosh, J. H. (2016). The political divide on climate change: Partisan polarization widens in the US. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 58(5), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2016.1208995

- EP Legislative Observatory. (2019a). Review of the renewable energy directive 2009/28/EC. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-resilient-energy-union-with-a-climate-change-policy/file-jd-renewable-energy-directive-for-2030-with-sustainable-biomass-and-biofuels

- EP Legislative Observatory. (2019b). CO2 Emission standards for cars and vans. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-resilient-energy-union-with-a-climate-change-policy/file-jd-co2-emissions-standards-for-cars-and-vans

- Eurostat. (2019). Energy dependence. 11.09.2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/EN/t2020_rd320_esmsip2.htm

- Germanwatch. (2014). The climate change performance index 2014, Berlin.

- Herranz-Surrallés, A. (2016). An emerging EU energy diplomacy? Discursive shifts, enduring practices. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1386–1405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1083044

- Herranz-Surrallés, A., Solorio, I., & Fairbrass, J. (2020). Renegotiating authority in the Energy Union: A framework for analysis. Journal of European Integration, 42(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708343

- Hess, D. J., & Renner, M. (2019). Conservative political parties and energy transitions in Europe: Opposition to climate mitigation policies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 104, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.019

- Hix, S., Noury, A. G., & Roland, G. (2007). Democratic Politics in the European Parliament. Cambridge University Press.

- Hix, S., Noury, A., & Roland, G. (2018). Is there a selection bias in roll call votes? Evidence from the European parliament. Public Choice, 176(1), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0529-1

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. J. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310

- Huber, R., Maltby, T., Szulecki, K., & Ćetković, S. (2021). Is populism a challenge to European energy and climate policy? Empirical evidence across varieties of populism. Journal of European Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918214.

- Hurka, S., Kaeding, M., & Obholzer, L. (2015). Learning on the job? EU enlargement and the assignment of (shadow) rapporteurships in the European Parliament. Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(6), 1230–1247. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12270

- Judge, D. (1992). ‘Predestined to save the Earth’: The environment committee of the European parliament. Environmental Politics, 1(4), 186–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644019208414051

- Judge, D., & Earnshaw, D. (2008). The European Parliament. Palgrave.

- Klüver, H., & Spoon, J.-J. (2015). Bringing salience back in: Explaining voting defection in the European parliament. Party Politics, 21(4), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813487114

- Lenschow, A., Burns, C., & Zito, A. (2020). Dismantling, disintegration or continuing stealthy integration in European Union environmental policy? Public Administration, 98(2), 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12661

- Lockwood, M. (2018). Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: Exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics, 27(4), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411

- Meyerrose, A. M. (2018). It is all about value: How domestic party brands influence voting patterns in the European Parliament. Governance, 31(4), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12327

- Mühlböck, M. (2012). National versus European: Party control over members of the European Parliament. West European Politics, 35(3), 607–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665743

- Neumayer, E. (2004). The environment, left-wing political orientation and ecological economics. Ecological Economics, 51(3-4), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.06.006

- Oberthür, S. (2019). Hard or soft governance? The EU’s climate and energy policy framework for 2030. Politics and Governance, 7(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i1.1796

- Otjes, S., & van der Veer, H. (2016). The Eurozone crisis and the European Parliament’s changing lines of conflict. European Union Politics, 17(2), 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515622567

- Petri, F., & Biedenkopf, K. (2021). Weathering growing polarisation? The European Parliament and EU foreign climate policy ambitions. Journal of European Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918216.

- Polk, J., Rovny, J., Bakker, R., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Koedam, J., Kostelka, F., Marks, G., & Schumacher, G. (2017). Explaining the salience of anti-elitism and reducing political corruption for political parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey data. Research & Politics, 4(1), Article 205316801668691. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168016686915

- Raunio, T., & Wagner, W. (2020). Party politics or (Supra-) National interest? External relations votes in the European parliament. Foreign Policy Analysis, 16(4), 547–564.

- Ringe, N. (2010). Who decides, and how: Preferences, uncertainty, and policy choice in the European Parliament. Oxford University Press.

- Ripoll Servent, A., & Roederer-Rynning, C. (2018). The European Parliament: A normal parliament in a polity of a different kind. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.152

- Roger, L., Otjes, S., & van der Veer, H. (2017). The financial crisis and the European Parliament: An analysis of the Two-Pack legislation. European Union Politics, 18(4), 560–580.

- Rooduijn, M., Van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., De Lange, S., Halikiopoulou, D., Lewis, P., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2019). The populist: An overview of populist, far right, far left and Eurosceptic parties in Europe. The PopuList. https://popu-list.org

- Schaller, S., & Carius, A. (2019). Convenient truths. Adelphi Research.

- Schreurs, M. A., & Tiberghien, Y. (2007). Multi-level reinforcement: Explaining European Union leadership in climate change mitigation. Global Environmental Politics, 7(4), 19–46. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2007.7.4.19

- Skjærseth, J. B. (2018). Implementing EU climate and energy policies in Poland: Policy feedback and reform. Environmental Politics, 27(3), 498–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1429046

- Solorio, I., & Jörgens, H. (2020). Contested energy transition? Europeanization and authority turns in EU renewable energy policy. Journal of European Integration, 42(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708342

- Thaler, P. (2016). The European Commission and the European Council: Coordinated agenda setting in European energy policy. Journal of European Integration, 38(5), 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1178252

- Toshkov, D. (2017). The impact of the Eastern enlargement on the decision-making capacity of the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(2), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1264081

- von Homeyer, I., Oberthür, S., & Jordan, A. J. (2021). EU climate and energy governance in times of crisis: Towards a new agenda. Journal of European Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918221.

- Wettestad, J., & Jevnaker, T. (2019). Smokescreen politics? Ratcheting Up EU Emissions Trading in 2017. Review of Policy Research, 36(5), 635–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12345

- Wurzel, R. K. W., Liefferink, D., & Di Lullo, M. (2019). The European Council, the council and the member states: Changing environmental leadership dynamics in the European Union. Environmental Politics, 28(2), 248–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1549783

- Zapletalová, V., & Komínková, M. (2020). Who is fighting against the EU's energy and climate policy in the European parliament? The contribution of the Visegrad Group. Energy Policy, 139, Article 111326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111326