ABSTRACT

Previous research shows that Differentiated Integration (DI) in areas of core state powers works according to a postfunctional logic, in response to concerns about national autonomy and sovereignty. Against this backdrop, scholars usually expect that the policies and practices ensuing from formal DI are equally differentiated. This article presents theoretical and empirical evidence to suggest otherwise. It argues that, while postfunctionalism explains the emergence of formal DI, its practical consequences are driven by functional pressures. The interdependencies produced by the integration process create functional incentives for states with opt-outs to work towards ‘reintegration’ by converging with EU policies. The result of this process is a decoupling between differentiated rules and similar practices. The plausibility of this argument is tested by applying process tracing techniques to the case of Denmark in Justice and Home Affairs.

Introduction

In its most common definition, the term Differentiated Integration (DI) refers to the differential validity of formal rules (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2014), established to overcome treaty negotiation deadlock caused by increasing heterogeneity across countries (Bickerton, Citation2019; Schimmelfennig, Citation2019b, p. 177). Formal DI can be either ‘instrumental’ (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2014), consisting of transitional arrangements negotiated between the EU and candidate countries for economic reasons (Leruth et al., Citation2019b) or ‘constitutional’, i.e., durable and ‘reflecting concerns over identity, sovereignty, and the nature and powers of the EU’ (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2014, p. 363). While instrumental DI is ‘made’, in effect, to disappear with time, the latter represents the essence of long-lasting differentiation and relates to ‘core state powers’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2016) including monetary policy, defence and home affairs (Winzen, Citation2020). The ‘multi-speed’ and ‘à la carte’ integration settings resulting from constitutional DI imply that once opt-outs are established, ‘laggards’ are left on the sidelines, while the rest of states proceed with further integration (Jensen & Slapin, Citation2012). The EU grows more and more diverse (Schmidt, Citation2019) as the processes of differentiated integration replace unified integration (Neve, Citation2007).

Against this backdrop, treaty-level DI is usually expected to be followed by DI at the policy level (Duttle et al., Citation2017; Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020; Zhelyazkova, Citation2014). However, upon closer inspection, the policies enacted by countries with an opt-out can vary greatly and, eventually, be closer to EU norms than what the characterization of the EU as a durably differentiated system might suggest (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020; Schmidt, Citation2019). To name a few examples, the United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland have contributed financially to the European Border Agency Frontex for over a decade, although they opted out from the Frontex regulation. Denmark, which enjoys a full opt-out from Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) has a far-reaching agreement with Europol and Eurojust to compensate for its recent loss of membership in the EU law-enforcement agencies. Similarly, during the Brexit negotiations, the UK attempted to obtain preferential treatment in police cooperation through Europol (Gutheil et al., Citation2018; Oltermann & Boffey, Citation2020). How can these practices be explained? The article provides theoretical insights concerning the different dynamics producing treaty DI and ensuing policies, and makes a thorough empirical sketch of the causal mechanisms involved in the decoupling between the attainment of differentiated rules and the subsequent adoption of similar practices.

Starting from the observation that ‘constitutional’ treaty-level differentiation is largely explained by postfunctional dynamics (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2014), it is argued that the policies and practices adopted after the acquirement of formal differentiation may be rather driven by functional logics. On the one hand, national governments respond to publicly-driven sovereignty concerns by negotiating formal opt-outs. On the other, they find practical ways to pursue convergence with EU policies. They do so in response to functional pressures from the increasing interdependence produced by the integration process itself. In summary, while postfunctional pressures lead to formal differentiation (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2014, Citation2020), functional ones drive practical ‘reintegration’, by generating a decoupling between differentiated rules and similar practices. The argument is illustrated in a ‘pathway’ case study (Gerring, Citation2016) – reconstructed through process tracing – of the EU country enjoying the highest number of ‘constitutional’ opt-outs, Denmark, in the area of Justice and Home Affairs (JHA). The contribution this article makes is twofold. Theoretically, by arguing that formal DI might not produce as much diversity as commonly thought, it reverts the traditional focus of research on the consequences of DI and opens a debate on the material impact of DI on both EU policy making, and EU integration. Empirically, it provides a detailed causal reconstruction of the phenomenon in a highly meaningful case, providing the basis for further investigation.

The causes and consequences of DI

While research on the causes of DI has reached its scientific maturity, there has been much less research on the consequences of DI (Burk & Leuffen, Citation2019; Gänzle et al., Citation2019). Recently, Brexit gave a new momentum to this strand of research, as the UK’s decision to exit the EU in spite of the opt-outs it enjoyed (Holzinger & Tosun, Citation2019) may suggest that DI paves the way to (differentiated) disintegration (Leruth et al., Citation2019b; Schimmelfennig, Citation2018). So far, existing empirical evidence has shown that treaty law and secondary legislation follow similar differentiation logics (Duttle et al., Citation2017; Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020). Moreover, studies focusing on implementation have concentrated on the number of opportunities that states have to diverge from common rules beyond the treaties. Not only can they negotiate exemptions through secondary law (Duttle et al., Citation2017; Franchino, Citation2007; Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020), they can also interpret rules in different ways and, consequently, implement them differently (Andersen & Sitter, Citation2006; Chebel d’Appollonia, Citation2019). Even with regards to legislation they opt in to, countries enjoying exemptions perform, on average, worse in comparison to full members (Zhelyazkova, Citation2014). As a way to counterbalance these multiple roads to diversity, it has been shown that Brussels-based officials seek to circumvent their countries’ opt-out in everyday decision-making by getting involved in EU policy-making, although their countries do not formally participate in those areas (Adler-Nissen, Citation2009, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Naurin & Lindahl, Citation2010).

The above contributions provide a multi-faceted picture of what ensues from formal DI at different levels – secondary law, (differentiated) policy implementation, bureaucratic politics – and suggest that the practices stemming from formal DI are characterized by deep differentiation. Even when ‘circumventing’ opt-outs, bureaucrats work under severe constraints caused by their states’ decision to opt out. Thus, an explanation is needed as to why the effect of formal DI might be less pervasive (and not more) than one might think. How do we account for the adoption of practices that lean towards reintegration, rather than differentiation? The next section provides an overview of the article’s theoretical approach and expectations.

Function vs identity? From differentiated rules to similar practices

According to several contributions, constitutional DI follows a postfunctional logic (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009, p. 13; Leuffen et al., Citation2013; Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2014, Citation2020). If issues connected to core state powers undergo public scrutiny, governmental elites – while on average more supportive of EU integration than public opinion (Hobolt & de Vries, Citation2016; Müller et al., Citation2012) – are more likely to find themselves constrained by domestic politicization and, hence, negotiate opt-outs. Whereas the above argument has been widely tested and corroborated by empirical evidence (Schimmelfennig, Citation2018; Schimmelfennig et al., Citation2015; Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2014), explaining the connection between formal DI and the policies adopted after states obtain opt-outs, requires a different theoretical angle.

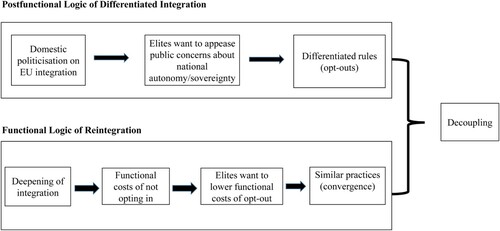

Negotiating exemptions is considered, especially in treaty reforms (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020), rather uncostly: countries with an opt-out are mainly concerned with national autonomy, and they are not subjected to negative externalities, as ‘they are not in need of the club good of the insiders’ (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020, p. 41). At the same time, opt-outs are politically rewarding vis-à-vis domestic public opinion, as they ‘preserve’ national sovereignty while enhancing the public’s perception of democratic legitimacy in the EU (Schraff & Schimmelfennig, Citation2020). However, the pragmatic consequences of opting out might become costly over time: the deepening of the integration process progressively produces unforeseen externalities and/or functional spillovers affecting also selective non-members. To name a few examples, the creation of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) had a substantial impact on all European financial markets (Howarth & Quaglia, Citation2020), Europol’s work significantly contributed to shaping the EU counterterrorism strategy (Kaunert, Citation2010), and the flawed common EU asylum system produced high systemic inefficiencies and great disparities between northern and southern EU states (Trauner, Citation2016). The argument presented here is that, in reaction to these path-dependent dynamics, political elites may act in a way that is ‘decoupled’ (Heidbreder, Citation2013, p. 136) from the objectives they pursued during the negotiation of opt-outs. Notably, the EU normative framework is rather flexible (Dawson & Durana, Citation2017; Witte et al., Citation2017). For example, directives leave considerable discretion to member states to interpret and implement rules, and groups of member states can cooperate beyond the institutional formats of the EU (De Witte, Citation2020; Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020, p. 4). Thus, as much as states can find flexible ways to understand and implement EU laws when law constrains them (Andersen & Sitter, Citation2006; Versluis, Citation2007), they can arguably do the same when law exempts them. DI is emblematic in this context: whereas states with an opt-out are supposedly unconstrained by formal rules, the integration process advances and produces interdependences (Leuffen et al., Citation2013) that grow deeper and deeper as member states affect each other’s actions by pooling decision making, adopting common policies, building supranational capacities (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2016) and participating in hybrid administrative structures (Everson et al., Citation2014). Functional pressures produced by interdependence increase the cost of opt-outs, and push the national policies of states with an opt-out towards convergence (Holzinger & Knill, Citation2005), even if the treaties do not oblige them to do so. In summary, national policy makers, moved by pragmatic reasons, might enact a behaviour that is inconsistent with existing formal rules (Heidbreder, Citation2013, p. 138) as they seek to converge towards EU norms in spite of the opt-outs. The result of this process, illustrated in , is a decoupling between differentiated rules (opt-outs) and similar practices (convergence).

Research design: tracing the pathway to decoupling

As noted earlier in this article, ‘instrumental’ DI is by definition meant to disappear with time and be replaced by uniform integration (Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2014), thus, the empirical focus of the study is ‘constitutional’ DI’. The population of cases displaying constitutional DI includes Eurozone non-membership of the UK, Denmark, Sweden; the Schengen non-membership of the UK and Ireland, Denmark’s opt-out from the common defence policy and exemptions from Justice and Home Affairs for Denmark, the UK, and Ireland (Hvidsten & Hovi, Citation2015; Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020, p. 53). While studying each of these cases would ensure the assessment of the applicability of the theory to all instances of constitutional DI, this would come at the price of internal validity gained by the detailed reconstruction of the causal mechanisms leading from differentiated rules (opt-outs) to similar practices (convergence). For this purpose, the analysis of a ‘pathway’ case provides a ‘uniquely penetrating insight into causal mechanisms’ (Gerring, Citation2016, p. 121). Following the logic of the crucial case, the pathway case is one ‘where the causal factor of interest […] correctly predicts Y’s positive value’ (Gerring, Citation2007, p. 240). The case of Denmark in the area of JHA is particularly suitable, as it possesses strong empirical features suggesting a positive causal connection between the variables of interest (Welle & Barnes, Citation2014). In fact, Denmark is considered as a model of ‘(quasi)-permanent’ differentiation (Leruth et al., Citation2019a) and, especially in JHA policies, the Danish opt-outs represent the major long-term consequences of a negative integration referendum in the history of the EU (Schimmelfennig, Citation2019a). On top of this, JHA is one of the policy areas subject to the most impressive development in the post-Maastricht era (Monar, Citation2012), which makes it likely to produce high levels of interdependence between member states.

Through an application of ‘theory-testing process tracing’ techniques (Beach & Pedersen, Citation2019), the analysis reconstructs the theorized causal connections between growing interdependence, functional pressures on governmental preferences and policy convergence, providing a plausibility probe of the hypothesized process, backed by within-case evidence. By applying the same method to other ‘positive cases’ (Beach, Citation2018) through further research, it will be possible to establish whether the same dynamics hold out in other similar contexts (Beach, Citation2018, p. 7; Gerring, Citation2016).

A thorough case reconstruction requires the detection of ‘observable manifestations’ of the hypothesized phenomena (Bennett, Citation2014), explaining how the main concepts of the theoretical framework are measured in order to maximize their content validity (Gschwend & Schimmelfennig, Citation2011). To avoid the pitfalls of storytelling, process tracing should be based on causal mechanisms that are derived ex-ante from theories, and diagrammed in an explicit way (Schimmelfennig, Citation2014; Waldner, Citation2014). Moreover, ‘each predicted observable has to be evaluated using existing knowledge for whether they have to be found in the given case (certainty), and if found, whether there are any plausible alternative explanations for finding them (uniqueness)’ (Beach, Citation2018, p. 16). Going back to , the theoretical framework draws the following causal steps. First, the process leading to the negotiation of an opt-out is expected to follow a postfunctional logic: governments negotiate opt-outs to maintain national sovereignty and autonomy in response to public pressure. Empirically, this would be supported by the observation that an opt-out is negotiated while elites (especially the government) are on average in favour of more integration, and the public is less so. The mechanism would not be corroborated if the government were visibly opposed to further integration for reasons other than domestic politicization. Second, the process leading from increasing interdependence to convergence is theorized as being path-dependent: the more the integration process advances, the more policy areas are subject to pooled decision-making and the influence of EU institutions. Interdependence is fostered by the process of EU integration, as each integration step brings about additional transnational exchange and externalities for additional policy areas, which in turn produces demand for additional integration (Leuffen et al., Citation2013; Schimmelfennig et al., Citation2015). Therefore, EU policies increasingly affect national ones, and national policies affect each other (Gilardi, Citation2014). In response to the functional pressures caused by such interdependence, states opting out are expected to progressively adopt legal and policy instruments that are similar (or even the same) to those of the EU. According to Holzinger and Knill’s typology (Citation2005), convergence can take place for several reasons. These can range from imposition (whenever an external political actor forces a government to adopt a policy), to regulatory competition (bound to market-related competitive pressure to mutually adjust their policies), to international harmonization (when governments are legally required to adopt similar policies as part of their membership of international institutions), and, finally, to transnational communication (e.g., by adopting the same or similar national policies). In this context, the mechanism leading to convergence should come down to the observation of rule harmonization outside the treaties through, for example, parallel agreements (De Witte, Citation2020; Schimmelfennig & Winzen, Citation2020), and/or through the adoption of similar (or the same) national policies (Holzinger & Knill, Citation2005; Knill, Citation2005). As DI is supposed to ‘protect’ states’ autonomy from imposition in the areas where they opted out, and the areas we are dealing with – core state powers – do not concern market regulation, both imposition from above and regulatory harmonization seem unlikely to occur. Moreover, the mechanism leading to convergence would not be corroborated if policies did not converge at all, or if they did, but for reasons other than functional ones.

The empirical analysis relies on both primary and secondary sources, including media outlets, scholarly contributions, think-tank reports and survey data, EU and Danish official documents and politicians’ statements, as well as background conversations with experts.Footnote1 The preferences of elites about integration are drawn from political manifestoes and campaigns (Leruth, Citation2015), while the degree of domestic politicization is found in electoral polls and secondary sources. The ‘deepening’ of EU integration and increase in interdependence are detected, respectively, by treaty amendments and a shift to the community method (Börzel, Citation2005), and by the increase of transnational exchange/economies of scales/externalities in specific policy areas (Leuffen et al., Citation2013). The outcome, decoupling between rules and practices, results from the combination of two dimensions. On the one hand, the primary legal framework illustrates the exemptions negotiated by the country of interest. On the other hand, policy convergence is measured as the ‘increase in the similarity between one or more characteristics of a certain policy (e.g., policy objectives, policy instruments, policy settings) across a given set of political jurisdictions […] over a given period of time’ (Knill, Citation2005, p. 768). Decoupling, in turn, results from the dissimilarity between the primary legal framework and the characteristics of the policies pursued by governments in practice.

In the next section, the case study is reconstructed. In order to flesh out the main steps of the causal process, the sections are organized chronologically and accompanied by ‘causal graphs’ (Waldner, Citation2014) illustrating the causal mechanisms and their corresponding observable manifestations.

Opting out from JHA: the story of Denmark

Maastricht and Edinburgh (1992–1993): a postfunctional logic of DI

In Denmark, the debate on EU integration became controversial in the mid-80s, after the Danish Parliament voted against the ratification of the Single European Act (Friis, Citation2002). Although the Treaty was eventually ratified through a referendum, this event opened the way to higher parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs (Arter, Citation1995), as well as to a ‘heated debate in Denmark about what exactly the European Community was and was not’ (Sørensen, Citation2004, p. 13). The actual history of Danish DI started under these premises, with the failed ratification of the Maastricht Treaty, which was opposed by 50.7 per cent of Danish voters. As a consequence, the following year the government negotiated a series of opt-outs which would grant Denmark exemptions in several areas, including all JHA policies decided through qualified majority voting (QMV). The new referendum passed with 57 per cent voting in favour.

The exemptions negotiated in Edinburgh (European Council, Citation1992) were largely reflected in the preferences of the electorate, rather than in those of political elites. In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty was supported by an overwhelming majority of Parliament, by nearly all groups concerned and unanimously by the press (Worre, Citation1995) and yet, the result was negative. The unexpected outcome virtually forced Poul Schlüter’s government (Marti Font, Citation1992) to re-negotiate the Maastricht terms through the Edinburgh Agreement. Several media outlets and secondary sources suggest that the majority of Danish political elites agreed to negotiated opt-outs precisely to make the Treaty more palatable to the electorate (Howarth, Citation1994; Siune et al., Citation1994) and give Danes ‘an alibi for changing their vote’ (MP Erling Olsen, quoted in Kinzer, Citation1992). This tactic was reflected in the communication strategy used by Danish parties. On the one hand, they put a strong accent on the negative consequences of a ‘no’. The conservatives in particular insisted on the importance of not being ‘at the mercy of the decisions of others’ (Conservative manifesto, quoted in Worre, Citation1995), while the Liberal Party’s slogans changed from a simple ‘Vote Yes!’ in 1992 to ‘Go for the safe choice, you will not get another chance’ in the second referendum (Atikcan, Citation2015). On the other hand, they stressed how the new agreement substantially differed from Maastricht in terms of preserving national sovereignty. As reported by Worre (Citation1995), slogans included ‘The Edinburgh agreements extract the teeth of the Union for Denmark’ (Socialist People’s Party), and ‘Denmark participates in those aspects of the Maastricht Treaty which do not indicate a European Union’ (Christian People’s Party).

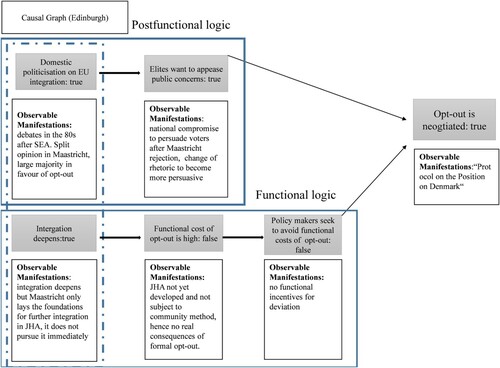

The causal process-graph () depicts the mechanisms just reconstructed, together with the observable manifestations of the phenomenon: at the time of the Edinburgh agreement, formal opt-outs did not affect the participation of Denmark in JHA policy-making. As the exemptions would apply only under QMV and this was not (yet) the case, the practical consequences of this formal arrangement were almost non-existent (Adler-Nissen, Citation2009; Peers, Citation2011, Citation2016). Hence, the opt-out clause in the early 90s – ‘an exercise in imprecision aimed at reassuring domestic public opinion’ (Financial Times, October 10; 1992. Quoted in Howarth, Citation1994, p. 61) was, as previously argued, rather uncostly at the functional level, and rewarding at the political one.

The Amsterdam Treaty (1997): growing interdependence and the functional costs of opt-outs

The tendency of Danish elites to appease citizens’ concerns over the opt-outs emerged again very clearly during the Amsterdam Treaty negotiations. At the time, the majority of Danish parties were wary of a rejection, mindful of the Maastricht ‘defeat’ and aware that polls since 1993 had regularly shown a majority for upholding the exemptions (Petersen, Citation1998, p. 12). Against this background, Danish representatives purposely focused on themes including employment, the environment, consumer protection and the fight against fraud (Petersen, Citation1998, p. 17), while they left the Edinburgh exemptions aside. Their decision to take the opt-out off the negotiating table was made precisely to ensure that the public acceptance of the revised Treaty would improve. According to Petersen: ‘there is little doubt that most Government members would have preferred to do without the exemptions, but a demonstrated willingness to give them up […] would have weakened its position vis-à-vis its own voters […]. So the Government’s position became […] that “the exemptions stand – before, during and after the IGC”' (Citation1998, p. 16). The referendum to ratify the Amsterdam TreatyFootnote2 passed with 55.1 per cent voting in favour (Folketing, Citation2020). The opt-out was formalized in a protocol on the position of Denmark attached to the Treaty.

After the Amsterdam Treaty was ratified, several JHA policies were moved from intergovernmental decision-making to the community method, and this not only implied a great change to the EU architecture, but also a great change for Denmark. As the Edinburgh exemptions remained untouched during the Treaty negotiations, the shift of most of JHA policiesFootnote3 to the first pillar produced by Amsterdam provoked a ‘deepening’ of the Danish opt-out (Peers, Citation2016). In practice, Amsterdam’s unlocking of the opt-out clause enshrined in the Edinburgh agreement was, under a functional perspective, highly problematic considering that Denmark was going to enter the Schengen area in 2000. To solve this issue, instead of trying to abolish the opt-out, a special arrangement was entered via Protocol No 22 (Stubb, Citation2002, p. 137). Article 4 of the Protocol included a compromise, known as the ‘Schengen technicality’, allowing Denmark in the Schengen acquis in spite of the opt-out. It stipulated that within a period of six months – after the Council had decided that the adopted text should build upon the Schengen acquis – Denmark should decide whether it will implement the legislation in domestic law. The six-months clause is nothing more than ‘a diplomatic way of saying that Denmark will be thrown out of Schengen if it does not implement a Council initiative’ (Adler-Nissen, Citation2014a, p. 70). In fact, the Schengen technicality is virtually non-existent, as Denmark has implemented all legislation building on the Schengen acquis to date.Footnote4 Moreover, Denmark has been an active participant in Schengen-related activities. For example, although the regulation establishing Frontex states that Denmark does not partake in its adoption, Denmark is effectively a member. Danish police have maintained their Seconded National Experts in Warsaw since the agency’s launch in 2005, and Danish police regularly provides staff for Frontex Joint Support Teams (Stevnsborg, Citation2013).

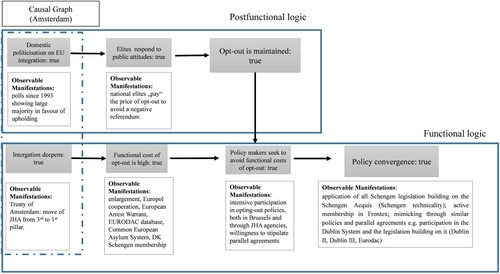

Schengen policies, however, were not the only ones Denmark sought to converge with. Since the Amsterdam Treaty, JHA became ‘one of the most dynamic and expansionist areas of EU development in terms of generating new policy initiatives, institutional structures and its impact on European and national actors’ (Monar, Citation2001, p. 748), and the costs of opting out became all the more clear. Hence, Danish decision-makers pursued a ‘pragmatic and permissive understanding of the opt-outs’ (Wivel, Citation2019, p. 7). Briefly, their attitude was to maintain the opt-out formally but to minimize it informally and on different fronts. They sought to influence EU every-day decision-making (Adler-Nissen, Citation2009), to protect Danish values in all issue-areas covered by the opt-outs (Adler-Nissen, Citation2014a; Marcussen, Citation2014; Olsen, Citation2011) and to ensure that they were ‘unofficially fused’ into EU decision-making (Miles, Citation2014, p. 217). Most importantly, however, they started adopting policies that were converging with the EU, beyond formal impediments imposed by the opt-outs. In particular, Denmark progressively acquired the practice of copying EU legislation into the Danish legal system also beyond Schengen legislation, by acting as a ‘copycat’ (Adler-Nissen, Citation2014a), as well as by mimicking EU policies through intergovernmental arrangements. Instead of risking to put an opt-in clause under public scrutiny,Footnote5 they negotiated parallel agreements on important matters including the jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters, on the Dublin System and the participation to the Eurodac Database (Council Decision 2006/188/EC).Footnote6 Even in the area of immigration and asylum, in which Denmark has traditionally been less prone to converge with EU norms (Gammeltoft-Hansen, Citation2017, p. 97), triggered by the EU’s moves in the field of reception and qualification of asylum seekers, Denmark has gradually introduced similar laws to its domestic legislation (Kreichauf, Citation2020, p. 51). shows the causal mechanisms and their observable manifestations: unlike in the case of Maastricht, the opt-out became costly. This, however, did not push policy-makers to abolish the opt-out, because domestic politicization was still high. Hence, the opt-out was preserved as a result of a postfunctional logic, while convergence was pursued in parallel, but by other means, as a result of functional pressures.

Lisbon and its aftermaths (2009–2019): looking for a backdoor entrance

Unlike the Maastricht and Amsterdam treaties, the Lisbon Treaty of 2009 was not subject to a referendum, as it was not considered to be causing a breach of national sovereignty (McLaughlin, Citation2007). Yet, the new protocol attached to the Treaty officially committed Denmark to work towards an opt-in clause in JHA, in view of the fact that the abolition of the pillar structure would place the remaining JHA policies, policing and criminal law rules, under the community method, and Denmark would be fully excluded from JHA cooperation (Peers, Citation2016). To abide by this commitment, the government led by PM Rasmussen launched a referendum in 2015. Had it been successful, Denmark would have opted into 21 legislative JHA provisions (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Citation2015) ranging from criminal law and police cooperation to civil, family and commercial law (Peers, Citation2014). Moreover, Denmark would have acceded to the forthcoming Europol regulation and would continue to participate in Eurojust and the EU Passenger Name Record (PNR). Yet, the referendum failed, as 53.11 per cent rejected the flexibility option.

The decision to launch the JHA referendum in 2015 had been triggered by the EU plan to replace the current rules establishing Europol, the EU police agency, with new legislation (Peers, Citation2016). Moreover, according to two Yougov surveys performed on behalf of Think Tank Europa, policy makers were less ‘worried’, as Danish public opinion appeared, this time, quite favourable to a selective opt-in. In 2014, 81 per cent of respondents believed that Denmark should continue to be a part of the EU’s cooperation to fight organized crime, under Europol’s coordination. Moreover, 60 per cent believed that there should be common rules on consumer protection and data security, and 57 per cent wanted the EU member states to establish a prosecution authority to combat financial crime (Møller, Citation2014). Alongside this favourable public leaning, the desire of Danish elites to avoid exclusion in JHA echoed in politicians’ statements: at the end of 2014, Justice Minister Hækkerup stated that ‘Denmark will end up being stuck outside’ without an opt-in clause (quoted in Møller, Citation2014). In December 2014, the five main Danish parties signed an agreement on Danish-EU politics, stating that they wanted to move Denmark ‘as close to the core of the EU’ and to reduce the number of opt-outs (Kluger Dionigi, Citation2016). In total, the parties supporting the ‘yes’ front represented more than 60 per cent of the parliamentary mandates and were backed by all trade unions and industry organizations (Ibolya, Citation2015). However, according to Sørensen, ‘the emotional discussion about sovereignty’ (Citation2015) pursued by the Dansk Folkeparti prevailed over the technical argument about the benefits of cooperation presented by the majority of Danish elites. In this regard, Lessing observes that ‘politicization seems to have outweighed interdependence, pushing for a limited loss of sovereign rights in a policy area traditionally considered as a core competence of the nation-state’ (Citation2017, p. 9).

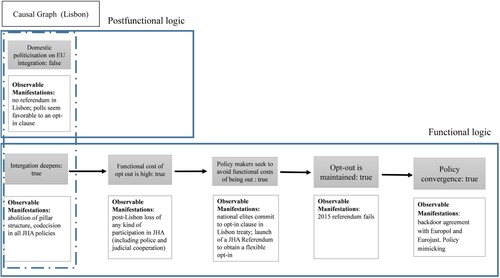

Hereafter, Denmark lost its membership in the two agencies and could not opt in to several legislative acts adopted after Lisbon. The inability to opt in to secondary legislation is partially compensated by the usual ‘copycat’ activities. For example, with the Act 275 of 27 March 2012 on the amendment of the Penal Code, Danish criminal legislation was brought into line with the Directive on ‘Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings’ (Danish Ministry, Citation2015), and the ‘Market Abuse Directive’ is partly implemented in the Danish Criminal code (Zwaan et al., Citation2016). Concerning police and judicial cooperation, Danish policy-makers have sought to minimize the post-Lisbon effect through parallel agreements. In particular, the 2017 agreement with Europol allows far-reaching cooperation despite the Danish opt-out from the Europol Regulation.Footnote7 Many referred to the arrangement as an ‘entry from the backdoor’ (Maurice, Citation2017), suggesting that cooperation will remain the same in practice, although arrangements are different from a legal standpoint. As Curtin argues, ‘Denmark as a voluntary Europol outsider may in practice and informally be granted (much) more liberal access to relevant data, also from other Member States, than its legal position would warrant’ (Curtin, Citation2018, p. 151). A similar arrangement was taken with Eurojust in 2019. In both cases, Denmark agreed to give the agencies additional membership quotas. The causal graph () illustrates the mechanisms just reconstructed, together with their observable manifestations. This time, domestic politicization was lower than in the past, hence Danish elites attempted to pursue convergence formally, by changing the treaty through a referendum to establish a flexible opt-out. As the referendum failed, they were forced to pursue policy convergence by means of parallel agreements, while the opt-out was maintained.

Discussion: postfunctional differentiation, functional reintegration

The above analysis of the case study largely supports the mechanisms developed in the theoretical section. The Edinburgh agreement was an obvious response to public rejection of further integration, which did not bear immediate and practical implications. The ensuing functional consequences are, as theorized, path-dependent. Since Amsterdam, given the rapid advancement of EU cooperation in JHA matters, policy convergence was pursued by Danish governments through several means, including international harmonization – through parallel agreements and the obtainment of ‘exemptions to the exemptions’ (Adler-Nissen, Citation2014a, p. 71) – and by essentially mimicking EU laws. These practices went hand in hand with a keen attitude towards transnational cooperation through EU agencies, the latest example being the negotiation of a ‘backdoor’ entrance to police and judicial cooperation through Europol and Eurojust. With the Lisbon Treaty, Danish policy makers attempted to escape the traditional postfunctional pressures, confident that the public would be less hostile to a JHA referendum. When the attempt failed, convergence was pursued nevertheless.

Previous scholarly contributions have studied the Nordic and, in particular, Danish, ‘exceptionalism’ (Grøn, Citation2015; Ingebritsen, Citation2000; McCallion & Brianson, Citation2017; Wivel, Citation2019). The relationship between Denmark and the EU has been defined as ‘ambivalent’ (Adler-Nissen, Citation2014a) and underlined a dilemma between influence and autonomy (Miles et al., Citation2013). The within-case evidence provided in this article shows how Denmark’s ambivalent relationship can be explained by a pattern of divergence between a postfunctional logic of formal differentiation (in response to public opinion’s attachment to national autonomy), and a functionalist logic of reintegration (in response to concerns about policy effectiveness). This is exemplified by the consistent attempts of Danish governments to ‘escape’ the limits imposed by the opt-outs in place, given the losses associated with them. The result of these attempts is a growing decoupling between rules and practices. Against this background, the ‘great flexibility from the EC side’ (Kelstrup, Citation2014, p. 18) towards Danish differentiation is matched by a similar flexibility of Denmark’s implementation of the opt-outs. In 1993, Gert Petersen, a Danish MP who campaigned against the Edinburgh compromise, argued that just adding ‘some notes at the bottom [of a treaty] saying that Denmark will not have to accept certain parts of it’ (quoted in Kinzer, Citation1992) would not be enough to ensure DI. In line with Mr. Petersen’s intuition, the reconstruction speaks in favour of a symbolic protection of sovereignty ensued by an active endeavour to align with the EU in major JHA policies.

A look beyond Denmark

At first sight, the Danish experience could be considered as a classic example of how elites construct legal and pragmatic ways out of clear political dilemmas (Curtin, Citation2018, p. 155). Beyond this rather straightforward observation, this study suggests that the practices stemming from formal DI might be more modest than traditionally expected: even when rules are very (and durably) differentiated, policies and practices adopted by states with an opt-out can be very similar to EU ones. In fact, in spite of the challenges posed by politicization to uniform integration, interdependence is a driver of alternative, or ‘covert’ (Héritier, Citation2015) channels of (re)integration. Formal DI remains a way to overcome gridlock and avoid stagnations, but allows for a number of undetected deviations to occur.

Within the limits of a single-n case study, this article questions what the real boundaries between membership and non-membership, between opt-ins and opt-outs, between integration, disintegration and ‘reintegration’, might be. In Eriksen and Fossum’s (Citation2015) analysis as to the implications for Norwegian democracy of membership of the European Economic Area, Norway’s rejection of formal membership (whether in a particular policy regime or the EU as a whole) turns it into a de facto rule-follower, without a full voice in decision-making. Even in the extreme case of Brexit, the self-imposed disintegration process has been accompanied by the possibility to be re-included in several policy areas (see Brexit Agreement, Citation2020). This could imply that, at least in cases where the pragmatic/functional pressures for participation in EU policy regimes are compelling, formal DI (and formal non-membership) are matters deeply rooted in domestic politics, rather than authentic barriers to uniform policy-making in the EU. In order to expand the external validity of this study, a systematic assessment of the extent of this phenomenon in the EU requires further empirical investigation. In particular, future contributions might want to expand the focus of this research by looking at whether the same mechanisms apply to other positive cases.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Markus Jachtenfuchs for his invaluable help and constant feedback during the writing process. Moreover, many thanks to Christian Freudlsperger, Philipp Genschel, Adina Maricut-Akbik, Maria Uttenthal and my interviewees for sharing their precious knowledge and insight with me. A special thanks to Frank Schimmelfennig and to the whole InDivEU consortium for making this research possible. Finally, many thanks to JEPP editors and two anonymous reviewers for providing detailed and constructive comments on previous drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marta Migliorati

Marta Migliorati is a postdoctoral researcher at the Jacques Delors Centre, Hertie School, Berlin.

Notes

1 A Europol specialist, a Danish Attaché based in Brussels, and a Think-Tank member specialized in Danish-EU affairs.

2 According to Art 20 of the Danish constitution, it is necessary to hold a referendum to ratify treaties implying a transfer of sovereignty.

3 Asylum, immigration, external borders, combating fraud, customs cooperation and judicial cooperation in civil matters.

4 Inquiry to Danish Attache, 21/11/2019.

5 Inquiry with Think-Tank expert, August 26, 2020.

6 Inquiry with Think-Tank expert, August 26, 2020.

7 Inquiry to Europol expert, February 2, 2020.

References

- Adler-Nissen, R. (2009). Behind the scenes of differentiated integration: Circumventing national opt-outs in Justice and Home Affairs. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(1), 62–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802453239

- Adler-Nissen, R. (2014a). Justice and home affairs: Denmark as an active differential European. In L. Miles & A. Wivel (Eds.), Denmark and the European Union (pp. 65–79). Routledge.

- Adler-Nissen, R. (2014b). Opting out of the European Union: Diplomacy, sovereignty and European integration. Cambridge University Press.

- Andersen, S. S., & Sitter, N. (2006). Differentiated integration: What is it and how much can the EU accommodate? Journal of European Integration, 28(4), 313–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036330600853919

- Arter, D. (1995). The Folketing and Denmark’s “European policy”: The case of an “authorising assembly”? The Journal of Legislative Studies, 1(3), 110–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13572339508420440

- Atikcan, E. O. (2015). Asking the public twice: Why do voters change their minds in second referendums on EU treaties? EUROPP. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/10/19/asking-the-public-twice-why-do-voters-change-their-minds-in-second-referendums-on-eu-treaties/

- Beach, D. (2018). Process tracing methods. In C. Wagemann, A. Goerres, & M. Siewert (Eds.), Handbuch Methoden Der Politikwissenschaft (pp. 1–21). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. Retrieved October 6, 2020, from http://link.springer.com/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-16937-4_43-1

- Beach, D., & Pedersen, R. B. (2019). Process-tracing methods: Foundations and guidelines (2nd ed.). University of Michigan Press.

- Bennett, A. (2014). Process tracing: From metaphor to analytic tool. Cambridge University Press.

- Bickerton, C. J. (2019). The limits of differentiation: Capitalist diversity and labour mobility as drivers of Brexit. Comparative European Politics, 17(2), 231–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00160-x

- Börzel, T. A. (2005). Mind the gap! European integration between level and scope. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(2), 217–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500043860

- Brexit Agreement. (2020). Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community. Retrieved February 23, 2020, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:22020A0131(01)

- Burk, M., & Leuffen, D. (2019). On the methodology of studying differentiated (dis)integration: Or how the potential outcome framework can contribute to evaluating the costs and benefits of opting in or out. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(6), 1395–1406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12958

- Chebel d’Appollonia, A. (2019). EU migration policy and border controls: From chaotic to cohesive differentiation. Comparative European Politics, 17(2), 192–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00159-4

- Council Decision 2006/188/EC. Retrieved January 28, 2021, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32006D0188&from=EN

- Curtin, D. (2018). The ties that bind: Securing information-sharing after Brexit. In B. Martill & U. Staiger (Eds.), Brexit and beyond, rethinking the futures of Europe (pp. 148–155). UCL Press. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt20krxf8.22

- Danish Ministry. (2015). The Danish government’s action plan to combat human trafficking. Retrieved April 1, 2020, from http://lastradainternational.org/doc-center/1331/the-danish-governments-action-plan-to-combat-trafficking-in-women

- Dawson, M., & Durana, A. (2017). Modes of flexibility: Framework legislation v ‘soft’ law’. In B. De Witte, A. Ott, & E. Vos (Eds.), Between flexibility and disintegration (pp. 92–117). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- De Witte, B. (2020). Overcoming the single country veto in EU reform? European Papers - A Journal on Law and Integration, 2020(5), 983–988. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15166/2499-8249/408

- Duttle, T., Holzinger, K., Malang, T., Schäubli, T., Schimmelfennig, F., & Winzen, T. (2017). Opting out from European Union legislation: The differentiation of secondary law. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(3), 406–428. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1149206

- Eriksen, E. O., & Fossum, J. E. (2015). The European Union’s non-members: Independence under hegemony? Routledge.

- European Council. (1992). Denmark and the treaty on European Union. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:41992X1231

- Everson, M., Monda, C., & Vos, E. (2014). EU agencies in Between institutions and member states. Wolters Kluwer.

- Folketing. (2020). EU referenda. EU Information Centre - Home. Retrieved May 15, 2020, from https://english.eu.dk/en/denmark_eu/eu-referenda

- Franchino, F. (2007). The powers of the union: Delegation in the EU. Cambridge University Press.

- Friis, L. (2002). The battle over Denmark: Denmark and the European Union. Scandinavian Studies, 74(3), 379–396.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. (2017). Refugee policy as “negative nation branding”: The case of Denmark and the Nordics. In F. Kristian & H. Mouritzen (Eds.), Foreign Policy Yearbook (Vol. 2017, pp. 97–119). DIIS.

- Gänzle, S., Leruth, B., & Trondal, J. (2019). Differentiated integration and disintegration in a post-Brexit era. Taylor & Francis Ltd.

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2016). More integration, less federation: The European integration of core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1055782

- Gerring, J. (2007). Is there a (viable) crucial-case method? Comparative Political Studies, 40(3), 231–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006290784

- Gerring, J. (2016). Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge University Press.

- Gilardi, F. (2014). Methods for the analysis of policy interdependence. In I. Engeli & C. R. Allison (Eds.), Comparative policy studies: Conceptual and methodological challenges, Research Methods Series (pp. 185–204). Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137314154_9

- Grøn, C. (2015). The Nordic countries and the European Union: Still the other European community? (1st ed.). Routledge. Retrieved January 13, 2020, from https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315726335

- Gschwend, T., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2011). Research design in political science: How to practice what they preach. Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved January 28, 2021, from http://www.dawsonera.com/depp/reader/protected/external/AbstractView/S9780230598881

- Gutheil, M., Liger, Q., Heetman, A., Henley, M., & Heyburn, H. (2018). The EU-UK relationship beyond Brexit: Options for police cooperation and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, 110.

- Heidbreder, E. G. (2013). European Union governance in the shadow of contradicting ideas: The decoupling of policy ideas and policy instruments. European Political Science Review. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from http://core/journals/european-political-science-review/article/european-union-governance-in-the-shadow-of-contradicting-ideas-the-decoupling-of-policy-ideas-and-policy-instruments/6370A685935A5DE3187ED9DE58DF881E

- Héritier, A. (2015). Covert integration in the European Union. European Union: Power and Policy-Making, 351–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315735399-15

- Hobolt, S. B., & de Vries, C. E. (2016). Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science, 19(1), 413–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157

- Holzinger, K., & Knill, C. (2005). Causes and conditions of cross-national policy convergence. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(5), 775–796. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500161357

- Holzinger, K., & Tosun, J. (2019). Why differentiated integration is such a common practice in Europe: A rational explanation. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 31(4), 642–659. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0951629819875522

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Howarth, D. (1994). Compromise on Denmark and the treaty on European Union: A legal and political analysis. Common Market Law Review, 31, 765. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036339408429014

- Howarth, D., & Quaglia, L. (2020). One money, two markets? EMU at twenty and European financial market integration. Journal of European Integration, 42(3), 433–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1730346

- Hvidsten, A. H., & Hovi, J. (2015). Why no twin-track Europe? Unity, discontent, and differentiation in European integration. European Union Politics, 16(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116514557964

- Ibolya, T. (2015). A vote of no confidence: Explaining the Danish EU referendum. openDemocracy. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/vote-of-no-confidence-explaining-danish-eu-referendum/

- Ingebritsen, C. (2000). The Nordic states and European unity. Cornell University Press.

- Jensen, C. B., & Slapin, J. B. (2012). Institutional hokey-pokey: The politics of multispeed integration in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(6), 779–795. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.610694

- Kaunert, C. (2010). Europol and EU counterterrorism: International security actorness in the external dimension. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 33(7), 652–671. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2010.484041

- Kelstrup, M. (2014). Denmark’s relation to the European Union: A history of dualism and pragmatism. In L. Miles & A. Wivel (Eds.), Denmark and the European Union (pp. 14–29). Routledge.

- Kinzer, S. (1992). Decision for Europe; Danes will vote again on Europe, but treaty may see some changes. The New York Times. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/23/world/decision-for-europe-danes-will-vote-again-europe-but-treaty-may-see-some-changes.html

- Kluger Dionigi, M. (2016). Denmark and the EU: Support for a sober and pragmatic membership | think tank EUROPA. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from http://english.thinkeuropa.dk/politics/denmark-and-eu-support-sober-and-pragmatic-membership

- Knill, C. (2005). Introduction: Cross-national policy convergence: Concepts, approaches and explanatory factors. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(5), 764–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500161332

- Kreichauf, R. (2020). Legal paradigm shifts and their impacts on the socio-spatial exclusion of asylum seekers in Denmark. In B. Glorius & J. Doomernik (Eds.), Geographies of asylum in Europe and the role of European localities (pp. 45–67). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25666-1_3

- Leruth, B. (2015). Operationalizing national preferences on Europe and differentiated integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(6), 816–835. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1020840

- Leruth, B., Gänzle, S., & Trondal, J. (2019a). Differentiated integration and disintegration in the EU after Brexit: Risks versus opportunities. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(6), 1383–1394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12957

- Leruth, B., Gänzle, S., & Trondal, J. (2019b). Exploring differentiated disintegration in a post-Brexit European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(5), 1013–1030. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12869

- Lessing, G. (2017). Police and border controls cooperation at the EU Level: Dilemmas, opporotunities and challenges of a differentiated approach. Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

- Leuffen, D., Rittberger, B., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2013). Differentiated integration. Macmillan Education UK. Retrieved May 13, 2019, from http://link.springer.com/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-28501-0

- Marcussen, M. (2014). Denmark and the Euro opt-out. In L. Miles & A. Wivel (Eds.), Denmark and the European Union (pp. 47–65). Routledge.

- Marti Font, J. M. (1992, June 3). Denmark rejects the Maastricht Treaty and disrupts the process of European Unity, from El País. 3.

- Maurice. (2017). Denmark clinches europol “backdoor” deal. EUobserver. Retrieved January 23, 2020, from https://euobserver.com/institutional/137730

- McCallion, M. S., & Brianson, A. (2017). How to have your cake and eat it too: Sweden, regional awkwardness, and the European Union strategy for the Baltic Sea Region (EUSBSR). Journal of Baltic Studies, 48(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2017.1305194

- McLaughlin, K. (2007). UPDATE 2-Denmark to ratify EU Treaty without referendum-PM. Reuters. Retrieved May 13, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/denmark-eu-idUSL1153810420071211

- Miles, L. (2014). Not quite a painful choice: Reflecting on Denmark and further European integration. In L. Miles & A. Wivel (Eds.), Denmark and the European Union (pp. 217–227). Routledge.

- Miles, L., & Wivel, A. (2013). Justice and home affairs: Denmark as an active differential European. Denmark and the European Union. Retrieved January 23, 2020, from https://www.taylorfrancis.com/.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2015). One step closer to a referendum on the JHA opt-out. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://um.dk/en/news/newsdisplaypage/?newsid=85867e49-b075-4425-97d5-d6fcf73f4bf4

- Møller, B. (2014). Large majority wants Danish participation in EU police cooperation | think tank EUROPA. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from http://english.thinkeuropa.dk/node/140

- Monar, J. (2001). The dynamics of Justice and Home Affairs: Laboratories, driving factors and costs. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 39(4), 747–764. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00329

- Monar, J. (2012). Justice and Home Affairs: The treaty of Maastricht as a decisive intergovernmental gate opener. Journal of European Integration, 34(7), 717–734. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2012.726011

- Müller, W. C., Jenny, M., & Ecker, A. (2012). The elites–masses gap in European integration. The Europe of Elites. A Study Into the Europeanness of Europe’s Political and Economic Elites, 167–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199602315.003.0008

- Naurin, D., & Lindahl, R. (2010). Out in the cold? Flexible integration and the political status of Euro opt-outs. European Union Politics. Retrieved January 21, 2020, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510382463

- Neve, J.-E. d. (2007). The European onion? How differentiated integration is reshaping the EU. Journal of European Integration, 29(4), 503–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036330701502498

- Olsen, G. R. (2011). How strong is Europeanisation, really? The Danish defence administration and the opt-out from the European security and defence policy. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 12(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2011.546141

- Oltermann, P., & Boffey, D. (2020). UK making “impossible demands” over Europol database in EU talks. the Guardian. Retrieved October 6, 2020, from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/uk-making-impossible-demands-over-europol-database-in-eu-talks

- Peers, S. (2011). Mission accomplished? EU Justice and Home Affairs Law after the treaty of Lisbon. 33.

- Peers, S. (2014). EU law analysis: Denmark and EU Justice and Home Affairs Law: Really opting back in? EU Law Analysis. Retrieved January 15, 2020, from http://eulawanalysis.blogspot.com/2014/10/denmark-and-eu-justice-and-home-affairs.html

- Peers, S. (2016). EU Justice and Home Affairs Law: EU Justice and Home Affairs Law: Volume I: EU Immigration and Asylum Law. Oxford University Press.

- Petersen, N. (1998). The Danish referendum on the treaty of Amsterdam Europas? ZEI-Zentrum Fur Europaische Ingegrationsforschung.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2014). Efficient process tracing. In A. Bennett & J. T. Checkel (Eds.), Process tracing: From metaphor to analytic tool, Strategies for Social Inquiry (pp. 98–125). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved October 21, 2020, from https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/process-tracing/efficient-process-tracing/F74FE495B6DE465ED77E0A2D5177A9E5

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2018). Brexit: Differentiated disintegration in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(8), 1154–1173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1467954

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2019a). Getting around no: How governments react to negative EU referendums. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 1056–1074. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619191

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2019b). The choice for differentiated Europe: An intergovernmentalist theoretical framework. Comparative European Politics, 17(2), 176–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00166-5

- Schimmelfennig, F., Leuffen, D., & Rittberger, B. (2015). The European Union as a system of differentiated integration: Interdependence, politicization and differentiation. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(6), 764–782. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1020835

- Schimmelfennig, F., & Winzen, T. (2014). Instrumental and constitutional differentiation in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(2), 354–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12103

- Schimmelfennig, F., & Winzen, T. (2020). Ever looser union?: Differentiated European integration. Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2019). The future of differentiated integration: A “soft-core,” multi-clustered Europe of overlapping policy communities. Comparative European Politics, 17(2), 294–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00164-7

- Schraff, D., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2020). Does differentiated integration strengthen the democratic legitimacy of the EU? Evidence from the 2015 Danish opt-out referendum. European Union Politics. Retrieved December 7, 2020, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520949698?icid=int.sj-full-text.citing-articles.1

- Siune, K., Svensson, P., & Tonsgaard, O. (1994). The European Union: The Danes said “no” in 1992 but “yes” in 1995: How and why? Electoral Studies, 13(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-3794(94)90028-0

- Sørensen, C. (2004). Danish and British popular euroscepticism compared. DIIS WORKING PAPER, 2004(25), 31. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from DIIS. https://www.diis.dk/en/research/danish-and-british-popular-euroscepticism-compared

- Sørensen, C. (2015). To be in, or to be out: Reflections on the Danish referendum. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from CEPS. https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/be-or-be-out-reflections-danish-referendum/

- Stevnsborg, H. (2013). Frontex and Denmark. Journal of Police Studies/Cahiers Politiestudies, 1(2).

- Stubb. (2002). Negotiating flexibility in the European Union: Amsterdam, nice, and beyond. Palgrave.

- Trauner, F. (2016). Asylum policy: The EU’s “crises” and the looming policy regime failure. Journal of European Integration, 38(3), 311–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1140756

- Versluis, E. (2007). Even rules, uneven practices: Opening the “black box” of EU law in action. West European Politics, 30(1), 50–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380601019647

- Waldner, D. (2014). What makes process tracing good? In A. Bennett & J. T. Checkel (Eds.), Process tracing: From metaphor to analytic tool, Strategies for Social Inquiry (pp. 126–152). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved February 23, 2021, from https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/process-tracing/what-makes-process-tracing-good/98834CC8C99284171CAAA00FE174F01C

- Welle, N., & Barnes, J. (2014). Finding pathways: Mixed-method research for studying causal mechanisms. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved April 12, 2021, from http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ref/id/CBO9781139644501

- Winzen, T. (2020). Government euroscepticism and differentiated integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(12), 1819–1837.

- Witte, B. D., Ott, A., & Vos, E. (2017). Between flexibility and disintegration: The trajectory of differentiation in EU law. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Wivel, A. (2019). Denmark and the European Union. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. Oxford University Press. Retrieved January 20, 2020, from https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1103

- Worre, T. (1995). First no, then yes: The Danish referendums on the Maastricht Treaty 1992 and 1993. Journal of Common Market Studies, 33(2), 235–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1995.tb00529.x

- Zhelyazkova, A. (2014). From selective integration into selective implementation: The link between differentiated integration and conformity with EU laws. European Journal of Political Research, 53(4), 727–746. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12062

- Zwaan, J. D., Lak, M., Makinwa, A., & Willems, P. (Eds.). (2016). Governance and security issues of the European Union: Challenges ahead (1st ed.). T.M.C. Asser Press.