?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

It is commonplace to claim that trust is essential to effective governance in many contexts, including that of a public health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. We argue that trust is better understood as a family of concepts – trust, mistrust and distrust – and each of these may have different implications for the governance of COVID-19. Drawing on original measures tested through nationally representative surveys conducted in Australia, Italy, the UK and the USA between May and June 2020, we explore how these distinct types of trust are associated with citizens’ perceptions of the threat posed by COVID-19, and their behavioural responses to it. We show how public policy dynamics around the COVID-19 crisis are driven by each of the trust family members and that policymakers might gain more from promoting an information-seeking and mistrusting society, rather than a trusting one.

The OECD (Citation2017) argues: ‘Trust plays a very tangible role in the effectiveness of government. Few perceptions are more palpable than that of trust or its absence. Governments ignore this at their peril’. Trust-building has been a key strategy of OECD governments in the last decade or so (Bouckaert, Citation2012). The context of crisis created by the onset of a global pandemic provides a stress test for these trust-building strategies and more broadly for the governance system (Boin et al., Citation2016, p. 3; Drennan et al., Citation2015). Trust is both needed to respond to the pandemic and is under threat due to it. In May 2020, an article in the British Medical Journal captured a consensus about the importance of public trust to tackling COVID-19. It argued:

The public will need to trust the government, trust that ministers are sensitive to the fears and anxieties people are experiencing and have the right strategy to respond. In turn, the government will need to trust the public to implement the next phases of their plan. (Mahtani & Heneghan, Citation2020)

surprise in various ways; they are fundamentally ambiguous, even messy. So much happens in such a short time, so many problems appear simultaneously or in rapid succession, so many people do not know what to think and whom or what to trust, that a generalized sense of uncertainty emerges. (Boin et al., Citation2016, p. 8)

Good standing before a crisis might enable a leader or government to ride it out successfully and even build public trust (Boin et al., Citation2008; Bennister, Worthy, & ‘t Hart, Citation2017). The time horizon of COVID-19 as a crisis already stretches over more than a year and may reverberate for decades, but our focus here is on the early acute phase, and where and how trust plays a role in the immediate response to a crisis. Studies have been quick to link social and institutional trust to COVID-19 outcomes and show how the crisis led to an increase in trust in political authorities among citizens – at least initially (see Devine et al., Citation2020) – which might in turn enable success in handling the crisis. There is also evidence that in the early phase of the crisis public trust was associated with greater public compliance with government interventions (see Weinberg, Citation2020). Is the trust dilemma so easily resolved? We argue there is a more complicated dynamic even in the early stages of responding to COVID-19 as a crisis.

We propose to expand this debate through exploring distinct members of the ‘trust family’ – trust, mistrust and distrust – and how they shape citizens’ perceptions and behaviours during the early days of the coronavirus crisis. Our expectation is that trusting, mistrusting and distrusting citizens will differ in their assessments of the threat posed by COVID-19 and in the degree to which they adjusted their day-to-day behaviour in response to outbreak of the pandemic.

The relationship of COVID-19 with trust, mistrust and distrust might not be straightforward. Might it be more trusting or distrusting individuals who express greatest concern about the threat posed by COVID-19? In theory, more trusting individuals might tend to update their threat assessments in response to government warnings, while distrustful individuals could form their own evaluations and perhaps discount information from government and experts, and as a result be less compliant with social distancing and other government-promoted control mechanisms. Do mistrusting citizens respond differently, discriminating and adjusting their trust in government plans depending on the context and available information? These are important questions that may allow us to shed light on the relationship between public opinion and public policy in the context of COVID-19.

In this paper we explore how trust, mistrust and distrust are associated with (a) public perceptions of the threat posed by the virus, and (b) the adjustment of behaviours in response to the pandemic. This approach allows us to understand how trust connects public opinion and public policy in governance of the coronavirus pandemic at an early moment in the crisis. Our empirical analyses use original data from national surveys conducted online in Australia, Italy, the UK and the USA between May and June 2020. These surveys asked citizens about their views on the threat posed by COVID-19 and changes they had made to their personal day-to-day behaviour since the pandemic began, as well as a battery of survey questions designed to measure the different underlying constructs of the trust family.

The analyses are organized as follows. We firstly conduct factor analysis to identify the constructs of trust, mistrust and distrust from the latent underlying dimensions of survey responses. This provides evidence of construct validity. We next present regression models of threat perceptions of COVID-19, including the three trust constructs as predictors alongside a series of demographic and political controls. We then present models of self-reported behaviour modification since the onset of the pandemic, again determining the relationship with trust, mistrust and distrust. We consider heterogeneity of the results across countries, finding that the USA has its own COVID-exceptionalism in terms of trust. Our analyses reveal that public attitudes and behaviours in relation to the governance of COVID-19 are driven not only by the degree to which citizens trust government, but also by how much they mistrust or distrust politics.

Three types of trust

Political trust has been a longstanding subject of enquiry for political scientists (see Levi & Stoker, Citation2000; Uslaner, Citation2017; Zmerli & Van der Meer, Citation2017), with substantial discussion of the implications of lower or higher levels of trust for public policy (Hetherington, Citation2005; Marien & Hooghe, Citation2011). For citizens to have trust or confidence in government is seen as a key ingredient for good governance and its absence is viewed as likely to undermine governing capacity. However, the concept of trust or lack of trust does not exhaust the orientations of citizens towards government and reviews have qualified both the presence of trust and its absence (Sniderman, Citation2017; Citrin & Stoker, Citation2018; Karmis & Rocher, Citation2018). As Citrin and Stoker (Citation2018, p. 49) comment: ‘(p)olitical trust is one of a family of terms referring to citizens’ feelings about their government’. Trust may also take a sceptical form for example (Norris, Citation1999, Citation2011; Dalton & Welzel, Citation2014; Norris, Jennings, & Stoker, Citation2019), and a lack of trust might lead to mistrust or distrust among citizens (Citrin & Stoker, Citation2018; Lenard, Citation2008). The concept of trust may thus be more effectively perceived and analysed as a family with trust, mistrust and distrust as its members. Conceptual expansion of the trust family has been a theme in political theory and philosophy in recent decades (e.g., Hardin, Citation2006; Lenard, Citation2008; O’Neill, Citation2018) which provides useful clarity on conceptual differences. If, following Hardin (Citation2006), trust is driven by the assumption that the focus of trust has your interests at heart and will take them into account in their decisions, Lenard (Citation2008, p. 313) defines mistrust as ‘a cautious attitude towards others; a mistrustful person will approach interactions with others with a careful and questioning mindset’ whereas distrust denotes ‘a suspicious or cynical attitude towards others’. Citrin and Stoker (Citation2018, p. 50) make the distinction that whereas trust refers to a belief in the trustworthiness of others, ‘mistrust reflects doubt or skepticism about the trustworthiness of the other, while distrust reflects a settled belief that the other is untrustworthy’. Bertsou (Citation2019, p. 215) endorses this line of reasoning and defines political distrust as ‘a negative attitude held by an individual towards her political system or its institutions and agents’. This may capture suspicion or negativity towards the political elite or establishment, and as such has potential relevance to wider inquiry into the study of populism.

provides a summary of the overall orientation of each member of the political trust family, as well as associated attitudes and behaviours. This framework is neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive, since individuals may hold a combination of these viewpoints towards the same or different actors. Political trust judgements could be directed at politicians or other policymakers, government or other institutions, or the political system as a whole.

Table 1. The political trust family.

Trust is likely to be accompanied by a sense of confidence, security, perhaps even well-being, and it might inspire loyalty towards the trusted. The behaviour stimulated by the presence of trust could include a willingness to comply with regulations and laws (Marien & Hooghe, Citation2011). Distrust on the other hand carries negative affective orientations such as suspicion, antipathy and resentment. In political contexts it is often viewed as a threat to democracy; it may encourage disengagement, alienation and destructive cynicism. If distrust is the firm belief that the other is untrustworthy, then the implication for policymakers is that their recommendations or measures are likely to be ignored or resisted. It might in turn encourage the search for trusted intermediaries to carry messages that would otherwise be ignored. But distrust may have positive effects, if exploited or excluded groups mobilize distrust of their opponents to pressure for change (Lenard, Citation2008). Citizens have reason to distrust government if it is not acting in their interests or competently performing its duty to protect them in the face of crisis. In this sense, distrust shares a feature of trust. When distrust is correctly assigned (where A is right to distrust B in respect of X) it can have positive effects. If someone is acting in your interests and you perceive this, you are benefitted by that perception. When trust is incorrectly assigned (where A is wrong to trust B in respect of X, not recognizing that B is untrustworthy) it could have negative consequences for the truster and for society more widely. As O’Neill (Citation2018, p. 293) observes: ‘Trust is valuable only when directed to agents and activities that are trustworthy’.

Mistrust is a distinctive member of the trust family in that it is not based on a settled belief that the other is trustworthy or not. It involves a continuous process of feedback and updating, reconciling assessments of trust against trustworthiness, reflecting caution or scepticism concerning the expected actions of B in respect of X. The orientation of a mistruster is to be alert, informed and investigative. Mistrust will thus be manifested in a desire to assess the performance of B relative to expectations.

The three concepts of trust are abstract expressions of different orientations that citizens might take towards government. We do not assume that someone who does not trust government will inevitably distrust it. Lack of trust is not the same as positively believing the government is acting against your interests. Mistrust is similarly a distinctive orientation. Unlike trust or distrust it is not based upon a confirmed belief but rather a willingness to judge government based on assessment of its actions. Understanding these different orientations of citizens towards government could matter across many policy arenas, including that of the governance of a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theoretical expectations: the trust family and COVID-19

In the early phase of the pandemic, much of the inquiry into the relationship between trust and coronavirus related to a narrow conceptualization of trust: specifically, the traditional focus on confidence in leaders and institutions and its impact on political support and compliance (see Devine et al., Citation2020; Weinberg, Citation2020). Some studies related to trust as the dependent variable (such as in ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effects in political support) and others used it as an independent variable (such as predicting higher rates of compliance). In this section we expand our framework of analysis by expanding this investigation to different members of the trust family. In particular we ask how citizens’ orientations – of trust, distrust and mistrust – relate to their perceptions of the threat posed by COVID-19 and their behavioural adjustments in response to the pandemic. The choice of these two foci reflects their relevance to governance in a crisis, such as that provided by COVID-19. Threat defines a crisis for citizens, and it can shift their political outlook in complex ways (Albertson & Gadarian, Citation2015; Boin et al., Citation2016; Merolla & Zechmeister, Citation2009). It may make citizens more attentive, keen for information and understanding about how to respond. It may encourage increased anxiety, which in turn can lead to a coping response that looks to leadership and a decline in critical challenge. Alternatively, it could encourage the search for new insights and cues about what government is or is not doing in response. In this light, the connection between threat and the family of trust orientations we identify is worth exploring. Crises, especially pandemics such as COVID-19, also demand behavioural adjustments by citizens. They are expected to change significant parts of their everyday lives, in this case to follow public health guidelines and restrictions designed to limit the spread of the virus. The response of citizens is thus integral to how societies and governments respond to the crisis (Bavel et al., Citation2020). The connection between public compliance and the trust orientations of citizens is highly relevant, not least as compliance is often associated with citizens’ evaluations of the trustworthiness of political institutions and actors. Individuals are more likely to follow behavioural advice or restrictions if they believe government is competent, benevolent and communicatively truthful in handling crises like COVID-19 (Weinberg, Citation2020).

Drawing on the insights presented in , we can develop a range of hypotheses connecting trust orientations to threat perceptions and behavioural compliance during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. A starting hypothesis could be that those individuals with a mistrusting orientation will offer responses to COVID-19 that are most balanced and consistent with available evidence. They will perceive the threat proportionately to known risks (H1) and adjust their behaviours consistent with public health guidance and restrictions in order to protect themselves and those around them, especially in contexts where the risk is relatively high (H2). We would expect individuals with a strong trusting orientation to reflect the framing of the coronavirus threat by their government (H3). If government downplays the severity of the crisis, especially at an early stage, this may reduce threat perception among citizens (especially those supportive of the government). Since trust is associated with compliance, we expect trusting individuals to make greater adjustments to their behaviour, following guidelines and formal restrictions set by government (H4). Those with a distrusting orientation start from a deep sense of cynicism and even contempt for those in government. As such, one possibility might be that their perceptions of the threat posed by COVID-19 would simply be in opposition to the assessments of those in political authority (H5). Accordingly, distrusters might be inclined to perceive a greater threat where it is downplayed by government, and a lower threat where the crisis is emphasized by government. In a context where government is less interventionist in its response, this could lead distrusting citizens to adjust their behaviour more than trusters, who are more likely to respond to cues from government. As noted in , a classic response of those who distrust government and political leaders is defiance. We might expect, therefore, that distrusting citizens will be less compliant with COVID-related regulations imposed by governments (H6). These theoretical expectations are summarized in .

Table 2. Theoretical expectations regarding the trust family and response of citizens to COVID-19.

National varieties of the COVID-19 crisis

This study is concerned with how trust judgements influenced the public’s attitudes and behavioural responses in Australia, Italy, the UK and the US, at a particular moment in the global crisis. Our surveys were conducted after the initial ‘rally-round-the-flag’ for many incumbents had subsided (Jennings, Citation2020), and after the first peak of the pandemic had been passed – meaning that political support boosted by the crisis was deflating and transmission of the virus was in decline. The primary rationale for case selection is that three of our four cases (Italy, the US and the UK) were among the group of countries worst hit by the pandemic early on, while the fourth (Australia) represents a ‘most different’ case in terms of being a country with a very low prevalence of cases. This makes them important cases for understanding how trust, mistrust and distrust judgements influenced citizens’ threat perceptions and adjustment of behaviour in response to the crisis. These cases also offer a mix of political and party systems: one presidential versus three parliamentary; two federal versus two unitary; one fragmented party system with a coalition government led by a technocrat, another subject to intense partisan sectarianism.

In all cases, the head of national government – the president or the PM – was the primary focus of public opinion. Italy’s PM Giuseppe Conte was credited with responding quickly and dynamically to emergence of the crisis, on 23rd February 2020 initiating the first lockdown outside China in response to the coronavirus. British PM Boris Johnson was initially slow to react, introducing strict restrictions on 23rd March, but nevertheless enjoyed a boost to his approval ratings, and was himself later hospitalized with the virus. Australia’s PM Scott Morrison presided over an effective response to the pandemic (in contrast to mishandling a national bushfire crisis just months previously), enjoying considerable public support. US President Donald Trump’s handling of COVID-19 offers a stark contrast to the other leaders, at times actively denying or downplaying the pandemic, undermining scientific experts, and not offering federal leadership or coordination to assist state-level responses.

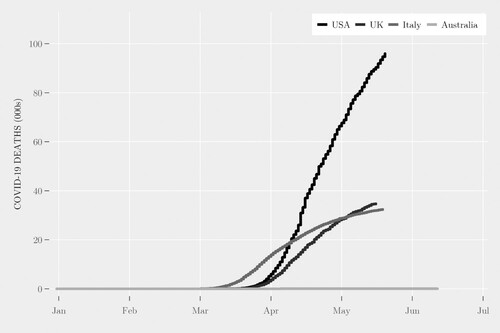

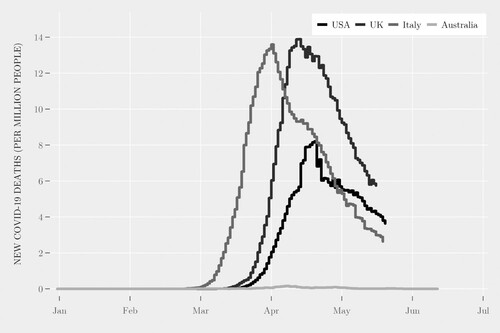

The reported number of cases and deaths offer a relative indicator of the performance of national governing systems in the immediate response to the coronavirus – measured here to the end date of the survey fieldwork in each of our four countries (see ). There are reasons to believe the trajectory of the virus and the governments’ response in those countries may have ramifications for how trust, mistrust and distrust affect threat perceptions and behavioural adjustments during the pandemic, since we expect trusters and distrusters to be especially sensitive to government framing whereas mistrusters should be especially sensitive to the actual level of risk posed by the pandemic. We use data from Our World In Data for our cases on the total number of reported deaths and the population-adjusted number of new daily reported deaths. These measures provide an indication of the relative severity of the pandemic in the countries at that point in time, plotted in and .

Table 3. National surveys on trust and COVID-19.

Here we can see that Australia barely registers in terms of number of reported deaths or new deaths per million people, with the pandemic being of a different magnitude compared to the other countries. Both figures reveal how Italy was an early casualty, with the number of recorded deaths and newly reported deaths rising fastest there initially. While the more populous USA saw its total of recorded deaths quickly soar above the other countries by mid-April, the UK’s population-adjusted number of deaths lagged and subsequently overtook Italy during this period, leaving it the worst hit country in relative terms. In terms of national varieties of COVID-19, we therefore have one case – Australia – that enjoyed comparatively good outcomes. We have one case – Italy – that experienced a poor start (reaching nearly 1000 deaths a day at one point) but had turned its fortunes around, with falling cases and deaths. We have one case – the UK – that has seen a high incidence of cases and deaths but had managed to somewhat suppress the virus by the time of our survey. And we have one case – the USA – that saw the most severe outbreak in absolute terms, even though the total number of deaths relative to its population size did not reach the level of Italy and the UK by this point.

The value of comparative analysis of how trust, mistrust and distrust impact the public’s threat perception and behaviours is that it offers insights into how these relationships vary depending on context, in terms of severity of the crisis and the nature of the government response and messaging. Comparison also enables the identification of findings that may generalize. It is to this analysis that we turn next.

Data and methods

We commissioned Ipsos to conduct online surveys of approximately 1100 adults in each of Australia, Italy, the UK and the USA in May and June 2020. The surveys were quota-controlled selections of pre-registered panel members, with population targets set to ensure representativeness of the national population. The survey asked respondents about their perceptions of the coronavirus pandemic, their self-reported behavioural adjustment since its onset and their trust judgements about governments and politics. Dates of the survey fieldwork and sample sizes of the surveys are summarized in .

Measuring trust, mistrust and distrust

To measure the different types of trust, we asked ‘To what extent do you agree, or disagree, with the following statements?’ with a series of statements (). Intended to indicate feelings of trust, mistrust and distrust towards government and politicians (with response options ‘Strongly agree’, ‘Tend to agree’, ‘Neither agree nor disagree’, ‘Tend to disagree’, ‘Strongly disagree’, ‘Don’t know’). These items were replicated from Devine et al. (Citation2020), who use them to measure these trust judgements in World Values Survey data and confirm that the items seem to approximate these three underlying constructs. The items are designed to capture the relational aspect of trust (trusting A to do B), the sceptical expression of mistrust (recognizing that A may or may not be trusted to reliably do B), and negative/affective orientations of distrust (believing that A will actively do B against my interests or preferences).Footnote1 As we will see, these measures do not perfectly map onto the three constructs of the trust family, but they do yield three underlying dimensions (factors) which appear to fit broadly with these underlying constructs.

Table 4. Survey items designed to measure trust, mistrust and distrust.

Threat perceptions

To gauge how citizens perceived the threat posed by the coronavirus pandemic, we asked ‘What level of threat, if any, do you think the coronavirus or COVID-19 poses to each of the following? You personally. Your country. Your job or business’. The response options were ‘very high threat’, ‘high threat’, ‘moderate threat’, ‘low threat’ or ‘very low threat’ (see ). The overall pattern was that responses tended to correspond to the national exposure to the virus of each country at the time of fieldwork: the highest level of perceived personal threat was observed in the UK, which at the time had the highest number of cases and deaths per capita of the four countries, and the lowest perceived threat in Australia, which had the least cases and deaths. The highest level of concern about the economic threat (to jobs and businesses) was observed in Italy and the UK – the countries that had been subject to the strictest containment measures. The highest level of concern about threat to the country is observed in the UK, with the lowest recorded in Australia – again reflecting differences in cases and deaths per capita, although it is notable that respondents in the USA seem substantially less concerned than in the UK despite the similar (and rising) deaths per capita.

Table 5. Perceptions of the threat from COVID-19.

Behavioural responses

To understand how citizens had adjusted their behaviour in response to the pandemic, we asked ‘For each of the following, please indicate how much, if at all, you have changed your behaviours on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much) compared with before the coronavirus outbreak?’. We listed a range of activities associated with reducing the spread of the disease, ranging from good hygiene to social distancing behaviours targeted by official regulations. presents the average response on the 0–10 scale for the seven activities we asked about, indicating that respondents in the UK reported the most behavioural adjustments by some margin; interestingly, respondents in the USA reported no more adjustments than respondents in Australia despite the substantial differences in case and death numbers between the two countries.

Table 6. Changes in behaviour since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis (average score).

Results

Factor analysis

So is there empirical support for distinguishing between our three types of trust? To explore the relationships between the 15 statements included in our trust battery, we start by conducting principal-component factor analysis, and rotating the factor matrix with a promax rotation, allowing the factors to be correlated to approximate a simple factor structure. The results from the rotated factor matrix are presented in . The factor loadings show a fairly clear structure of three underlying factors, albeit with overlap. The first factor seems to reflect a construct akin to political trust, correlating strongly with belief that politicians are open about their decisions (0.80), are honest and truthful (0.78), put country above personal interests (0.77), that government usually does the right thing (0.75), has good intentions (0.74) and understands the needs of my community (0.73). The second and third factors reflect two distinct types of attitude contrary to trust: the second tends to correspond with views that the government acts unfairly towards people like me (0.86), provides unreliable information (0.77), ignores my community (0.69) and doesn’t respect people like me (0.66), while the third is associated with being cautious about trusting politicians (0.79) and government (0.75) and unsure whether to believe them (0.78). Therefore, the second factor appears to capture a relatively deep-rooted distrust of the fundamental motives and moral character of politicians and government, while the third factor rather reflects a more conditional mistrust, a cautious approach to evaluating political actions and information. However, the statement ‘politicians are often incompetent and ineffective’ loads weakly and similarly to both the second and third factors, so it does not appear to distinguish between mistrust and distrust. We create scalar variables for each of these three distinct factors using predictions from the rotated factor loadings, standardized to range from 0 to 1. This means each scale uses information from every item in the battery, weighted by their factor loadings for each factor in turn, and we treat these factors as representing our concepts of trust, mistrust and distrust respectively.

Table 7. Principal-component factor analysis of measures of trust, mistrust and distrust.Table Footnotea

Of our items designed to capture these three types of trust, a small number did not load onto the dimension expected. The item suggesting ‘information provided by the government is generally unreliable’ loads most strongly onto distrust (rather than mistrust), possibly because respondents focused on the word ‘unreliable’. Similarly, the statement that ‘people in the government often show poor judgment’ is associated with distrust (not mistrust), again presumably because the item seems to pick up a negative orientation towards government officials, rather than a sceptical orientation, via the ‘often’ qualifier.

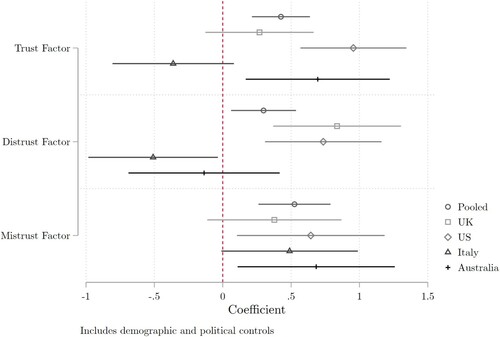

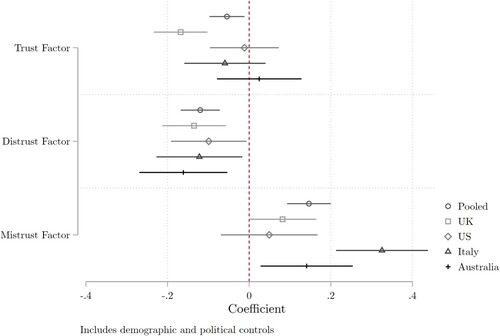

To test our hypotheses about the link between trust, mistrust, distrust and citizens’ perceptions of the threat stemming from COVID-19 and their behavioural adjustments in light of the crisis, we estimate regression models of each of these trust types (our independent variables) on our scales of threat perception and behaviour change since the onset of the pandemic (the dependent variables). In all of these models, we include country fixed effects and controls for respondents’ gender, age, employment status, income, education and left-right self-placement as well as incumbent party support and its interaction with country (to capture partisan effects associated with being a government supporter). We use coefficient plots, and , from the regressions to illustrate the effects of these trust constructs overall (pooled across countries) and in each of the four countries separately, enabling us to highlight heterogeneity by country. In the plots, the markers indicate the value of the coefficient and the horizontal bar indicates the 95 per cent confidence intervals of the coefficient.

How trust, mistrust and distrust influence perceptions of the threat of COVID-19

Starting with perceptions of the threat posed by COVID-19, we estimate linear regressions of the perceived threat to the respondents’ country as well as the threat to them personally and to their job or business on the trust, mistrust and distrust scales.Footnote2 The results of these models are presented in .Footnote3 Interestingly, these find positive effects, significant at the 95 per cent confidence level, for both the trust and distrust scales on threat perception in all three questions. The outcome variables are all measured on a five-point Likert scale from ‘very low threat’ to ‘very high threat’ and the x-axis in Figure 3 indicates the size of coefficients, where a change of one indicates a predicted change of one category on the five-point threat perception variable. The coefficients for the scalar variables indicate that for a one-unit change on the trust scale – going from lowest to highest trust (since the scales range from 0 to 1) – keeping our control variables constant, the value for personal threat perception is predicted to increase by 0.93 on the five-point threat scale, while perceptions of country threat increase by 0.43 and perceptions of threat to respondents’ job or business increase by 0.44. The coefficients for the distrust scale are similar to the above, again with the largest effect on perceived personal threat, but the only significant effect for the mistrust scale is a coefficient of 0.53 for country threat perception. Thus, our expectation that trust is related to higher threat perceptions (H3) is confirmed and the same goes for distrust (H5). Mistrusters appear less concerned about threat to themselves but more concerned about threat to the country, contrary to our expectations (H1).

Table 8. Regression models of the perceived threat from COVID-19.

presents the coefficient plots for the effects of each scale on the perceived threat of COVID-19 to the respondents’ country.Footnote4 Here we see that only the USA exhibits the counterintuitive pattern of trust, mistrust and distrust all increasing threat perception. In Australia, both the trust and mistrust scales have a positive effect on the perceived threat to the country, while distrust has a positive and significant effect in the UK as well as the USA: in Australia, people who hold greater trust in government and politicians, or are at least ‘critical citizens’, tend to view the coronavirus as a greater national threat, whereas in the UK and USA it is those who are more distrusting who consider it more of a threat (in Italy, people who are more distrusting perceive a lower national threat).

These heterogeneous findings are interesting since Australia is the country where COVID-19 posed the lowest objective threat at the time of our study, due to its relatively low incidence, while the UK and USA were suffering the highest mortality rate at the time of our surveys. This hints at effects being context-specific, with more trusting and mistrusting individuals perceiving a greater threat from the virus while it was under control (in Australia). Conversely, more distrusting individuals perceived a greater threat from the pandemic where it was most prevalent at the time (in the UK and USA), although they perceive less threat in Italy, where it was also prevalent. This may be because the pandemic was getting out of hand at this point in the UK and USA where government leaders (to different extents) seemed reluctant to tackle it effectively, whereas the gravest threat appeared to be subsiding in the Italy and the government had taken more decisive measures; which may have led those who distrusted government in Italy to be sceptical of the actual threat which the government was signalling.

How trust, mistrust and distrust influence adjustments in behaviour in response to COVID-19

Finally, we examine to what extent trust, distrust and mistrust are predictive of the extent to which citizens adjusted their day-to-day behaviour during the pandemic. For this, we created a scale based on the seven questions listed previously, which asked respondents about the degree to which they had changed their behaviour during the pandemic. As discussed, this measure may capture compliance with official guidelines and regulations on social behaviours, but at the same time could capture the actions taken by individuals to reduce their personal exposure to the virus (regardless of government policies). Of course, it could also reflect social desirability bias, where respondents claim to follow guidelines when they in fact do not, but the differences between countries on the scales at least seem to be largely consistent with what we might expect. The full regression models are presented in the online appendix, including models using both this scale and the simple mean of these measures as the dependent variable.

In , we plot the coefficients for the trust scales by country. These reveal that overall, both trust and distrust are negatively associated with behaviour change (or compliance), whereas mistrust is positively associated with it. This is consistent with our expectations for distrust (H6) but contrary to our expectations for trust (H4), as it indicates that more trusting citizens report having made fewer adjustments to their activities in response to the pandemic. The effect of trust is negative and significant at the 95 per cent confidence level in the UK, meaning that trust appears to reduce the level of behaviour change since the pandemic began, but it is not significant in the other countries. The negative effect of trust on compliance is therefore only apparent in the UK, but it is nonetheless surprising that we see no positive effect of trust in the other countries. In contrast, the plots reveal negative and significant effects for distrust in all four countries. As such, distrust consistently predicts that people will report having adjusted their behaviour less in response to the coronavirus crisis. Conversely, mistrust appears to increase behaviour change in Italy and Australia (and the UK, but only at the 90 per cent confidence level), with no significant effect for the USA. The pooled coefficient is no smaller than that for trust and distrust, which runs counter to expectations that this effect would be the most modest (H2). Citizens who are more willing to question and challenge information from government are also those who adjust their activities more in line with official guidelines and rules, at least where government appears to be handling the crisis relatively competently.

Conclusions

How citizens view the inputs and outputs of the governance of COVID-19 will matter as countries continue to deal with the pandemic and future pandemic threats, including novel variants of the coronavirus. We have argued that trust – associated with attitudes such as confidence and loyalty – may only be part of the story, and that the concepts of distrust and mistrust provide a more complete understanding of how the public will react to, and shape, government action during crises. This conceptualization of trust, mistrust and distrust has theoretical and empirical value. We have demonstrated that it approximates latent underlying dimensions of citizens’ responses to survey questions relating to politicians and government. We have shown these have significant and mainly intuitive effects on threat perception and adjustments of social behaviour in response to the pandemic during this acute phase of the crisis. Where the effects diverge from expectations, this appears to be a rational adjustment to the specific context of each country in relation to its experience of COVID-19.

With regards to threat perception, we have shown that trust is related to higher threat perception in the USA and Australia. Distrust is related to higher threat perception in the UK and USA, but lower threat perception in Italy. Mistrusters report higher threat perception in Australia and the USA. Overall, our results point to the importance of being context-sensitive: more trusting individuals perceived a greater threat from the virus while it was under control (in Australia), and more distrustful individuals perceived a greater threat where the mortality rate was highest (in the UK and USA).

Perhaps our most interesting results come in understanding behavioural adjustment, clearly key for improving health outcomes. Unlike previous research (for a review, see Devine et al., Citation2020), trust is only related to behavioural adjustment in the UK, and negatively so: trusters are less likely to adjust their behaviour, which is in line with some research which argues trust may lead to lower risk perception and greater complacency (Wong & Jensen, Citation2020). Distrust is also related to lower behaviour adjustment, potentially as those distrusters reject the severity of the pandemic and the advice of scientific experts and government. However, mistrusters, those we expect to be cautious and informed, are more likely to adjust their behaviour except in the USA. These results support the contention that trust may indeed be a double-edged sword, and it is instead mistrust that should be encouraged. Political theorists such as Onora O’Neill will be comforted to find support for their argument that democracies require mistrusting citizens who are sceptical but trust when trust is due.

Our study contributes to understanding public opinion during the COVID-19 crisis, but our intention is also to introduce and show empirically the importance of differentiating between trust, distrust and mistrust. We have shown that these can have notably distinct implications in different contexts, and that mistrust may be more desirable than trust. There are methodological limitations to the design of our study, such as its reliance on cross-sectional data, which prohibits us from making strict causal inferences. Similarly, self-reported survey measures of behaviour adjustment are imperfect, compared to observed mobility data, but enables us to link reported behaviour to citizens’ attitudes. In terms of comparative analysis, this study enables insights into how national contexts – in terms of severity of the pandemic and government responses – underpin the relationship between trust judgements and threat perceptions and changes in behaviour. However, it is limited to four countries, all liberal democracies. Different patterns might be found, for example, in autocratic states or at later points in the crisis.

Our evidence lends support to those seeking to shape responses of leaders to crises. Observe that governments ‘do not help themselves when they rely on rather crude assumptions about citizen behavior during crises in devising their crisis responses and communication strategies’. Citizen responses will be mixed as we have shown, but the best hope for policymakers is to treat citizens with respect and provide them with the information they need to come to a judgement.

Mistrusting citizens seem (reasonably) to judge the threat posed by COVID-19 as being significant. When asked to comply with a range of reasonable regulations – backed by many experts as the best options available – they are more willing than either trusting or distrusting citizens to shift their behaviour. Not just during the pandemic or other crises, we should perhaps turn our attentions to encouraging an information-seeking and mistrusting society, rather than a trusting one.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (3.9 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Will Jennings

Will Jennings is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the University of Southampton and Principal Investigator of the ESRC-funded TrustGov project exploring trust and trustworthiness of national and global governance. His research explores questions relating to public policy and political behaviour, specifically in relation to public opinion, political trust, elections, political geography, agenda-setting, and public administration. He is coauthor of Policy Agendas in British Politics (Palgrave, 2013), The Politics of Competence (Cambridge University Press, 2017), The Good Politician (Cambridge University Press, 2018) and The British General Election of 2019 (Palgrave, 2021).

Gerry Stoker

Gerry Stoker is Chair in Governance at the University of Southampton, UK and Emeritus Professor at the University of Canberra, Australia. He has authored or edited 33 books and published over 120 refereed articles. His work has been translated into many different languages. He is part of a wider team of researchers exploring the dynamics of trust, mistrust and distrust in politics and public administration (www.trustgov.net).

Viktor Valgarðsson

Viktor Valgarðsson is a Research Fellow on the TrustGov project and holds a PhD in Politics from the University of Southampton, which explored voter turnout decline in Western Europe. His broader research agenda is on changing patterns of political participation and political support in established democracies and their practical and normative implications. Previously, he worked at the University of Iceland and has also been active in politics and public debate, briefly taking a seat as a member of the Icelandic Parliament (Alþingi) in 2016. His academic research has been published in the journals Political Research Quarterly, Political Studies, Scandinavian Political Studies, Globalizations and Vaccines.

Daniel Devine

Daniel Devine is a Career Development Fellow in Politics at St Hilda's College, University of Oxford. He studies public opinion, particularly relating to political trust, policy preferences and voting. His work has been published in journals such as European Union Politics, Journal of European Public Policy and British Journal of Political Science.

Jennifer Gaskell

Jennifer Gaskell is a Research Fellow on the ESRC-funded TrustGov project exploring trust and trustworthiness of national and global governance, where she focuses on the management and analysis of the qualitative work programme. An interdisciplinary, mixed methods researcher, her work focuses on the role of information, and information and communication technologies in trust-building, political identity formation processes and effective governance across a range of political systems globally.

Notes

1 Responses to these questions in each country are summarised in Table A2 in the online appendix.

2 Our models take the general form where the dependent variable Y (threat perception or reported change in behaviour) for individual i is a function of the trust, mistrust and distrust factors, plus a number of other predictors Z (age, gender, incumbent party support, employment, income, university education, left-right self-placement) and country fixed effects K.

3 For clarity of interpretation and presentation, we present linear regression models instead of ordinal logistic regressions. The latter model specification yields highly similar results which inform identical inferences.

4 We use perceived threat to the country as the personal and job/business threat perceptions are significantly related to it, but coefficient plots and regression estimates for the other measures are presented in the online appendix, Figures A1 and A2 and Table A4.

References

- Albertson, B., & Gadarian, S. K. (2015). Anxious politics: Democratic citizenship in a threatening world. Cambridge University Press.

- Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E. J., Fowler, J. H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Alexander Haslam, S., Jetten, J., … Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

- Bennister, M., Worthy, A., & ‘t Hart, P. (Eds.). (2017). The leadership capital index. A new perspective on political leadership. Oxford University Press.

- Bertsou, E. (2019). Rethinking political distrust. European Political Science Review, 11(2), 213–230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000080

- Boin, A., McConnell, A., & ‘t Hart, P. (2008). Governing after crisis: The politics of investigation, accountability and learning. Cambridge University Press.

- Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2016). The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Bouckaert, G. (2012). Trust and public administration. Administration, 60(1), 91–115.

- Citrin, J., & Stoker, L. (2018). Political trust in a cynical Age. Annual Review of Political Science, 21(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050316-092550

- Dalton, R., & Welzel, C. (Eds.). (2014). The civic culture transformed: From allegiant to assertive citizens. Cambridge University Press.

- Devine, D., Gaskell, J., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2020). Trust and the coronavirus pandemic: What are the consequences of and for trust? An early review of the literature. Political Studies Review, 19(2), 274–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920948684

- Drennan, L., McConnell, A., & Stark, A. (2015). Risk and crisis management in the public sector (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Hardin, R. (2006). Trust. Polity.

- Hetherington, M. (2005). Declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton University Press.

- Jennings, W. (2020, March 30). Covid-19 and the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect. UK in a Changing Europe. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/covid-19-and-the-rally-round-the-flag-effect/

- Karmis, D., & Rocher, F. (Eds.). (2018). Trust, distrust, and mistrust in multinational democracies: Comparative perspectives. McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Lenard, P. T. (2008). Trust your compatriots, but count your change: The roles of trust, mistrust and distrust in democracy. Political Studies, 56(2), 312–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00693.x

- Levi, M., & Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 475–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475

- Mahtani, K., & Heneghan, S. (2020, May 5). Leadership in covid-19: building public trust is key. British Medical Journal blog. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/05/05/leadership-in-covid-19-building-public-trust-is-key/

- Marien, S., & Hooghe, M. (2011). Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance. European Journal of Political Research, 50(2), 267–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01930.x

- Merolla, J., & Zechmeister, E. (2009). Democracy at risk: How terrorist threats affect the public. University of Chicago Press.

- Norris, P. (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government. Oxford University Press.

- Norris, P. (2011). Democratic deficit: Critical citizens revisited. Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2019, May 19–21). In praise of scepticism: Trust but verify. Paper for the World Association of Public Opinion Research (WAPOR) 72nd annual conference Public Opinion and Democracy, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- OECD. (2017). Trust and public policy: How better governance can help rebuild public trust. OECD.

- O’Neill, O. (2018). Linking trust to trustworthiness. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 26(2), 293–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09672559.2018.1454637

- Sniderman, P. (2017). The Democratic faith. Yale University Press.

- Uslaner, E. (2017). The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. Oxford University Press.

- Weinberg, J. (2020). Can political trust help to explain elite policy support and public behaviour in times of crisis? Evidence from the United Kingdom at the height of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. Political Studies. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720980900

- Wong, C. M. L., & Jensen, O. (2020). The paradox of trust: Perceived risk and public compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. Journal of Risk Research, 23(7-8), 1021–1030. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1756386

- Zmerli, S., & Van der Meer, T. (2017). Handbook of political trust. Edward Elgar.