ABSTRACT

Previous studies have applied theories of European integration to interpret crisis-led policymaking processes and integration outcomes in the EU. However, there has been little attempt to appraise the analytical leverage offered by major integration theories as a function of different crisis pressures. We theorize that diverse combinations of crisis pressures generate four decision-making scenarios in the EU, each of which can be ascribed to different combinations of analytical insights from neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, postfunctionalism, and federalism. We illustrate the value of our framework in relation to four EU crises concerning the euro area, refugees, Brexit and Covid-19. Overall, the paper makes a theoretical contribution to advance the debate on crisis-led integration in the EU.

Introduction

Echoing the undertones of historical optimism often associated with Francis Fukuyama’s idea of the world entering into a post-historical phase, in 2005, Andrew Moravcsik argued that the European Union (EU) had reached a stable political equilibrium, a ‘constitutional compromise’ that was going to last (Moravcsik, Citation2005). According to Moravcsik, there was an absence of opportunities for substantive expansion of EU policymaking on a scale that required to alter its institutional order. Institutional constraints rendered change, either through everyday policymaking or constitutional revision, quite unlikely.

In a radical divergence from these expectations of institutional stability, the 2010s have exposed the EU to multiple and polymorphic crises. These crises have constituted ‘moments of truth’, in which the EU has experienced a ‘return of politics’ (Van Middelaar, Citation2020). In the face of this multiplicity of crises, the Union’s institutions have evolved significantly. Jean Monnet’s prophecy that ‘Europe will be forged in crises’ turned out to be simultaneously a blessing and a curse for the EU (Zeitlin et al., Citation2019): while integration has advanced at an unprecedented rate over the past decade, this evolution has often been associated with a heightened degree of political fragmentation inside the EU.

A host of studies have attempted to interpret this crisis-induced momentum of institutional innovation in the EU through the lenses of old and new theories of European integration (e.g., Hooghe & Marks, Citation2019; Moravcsik, Citation2018; Niemann & Ioannou, Citation2015; Schimmelfennig, Citation2014; Schimmelfennig, Citation2018). The abundance of scholarly work on the topic of crisis-led European integration suggests that no single integration theory can fully account for the variety of policymaking settings generated by the crises faced by the EU over the past decade. This is also confirmed by the fact that, as noted by Smeets and Zaun (Citation2021, p. 856), there are few scholars who still cling to the idea of ‘gladiator-like tests’, in which two theories enter the arena and only one steps out. Instead, what has become more common is to recognize that neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, postfunctionalism and other theories of European integration ‘are flexible bodies of thought that resist decisive falsification’ (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2019, p. 1113). Thus, instead of performing a horse race between different theories, a more promising approach to advance the scholarly debate may be to combine theoretical frameworks to understand the complexity of crisis-induced integration (Saurugger, Citation2016, p. 948).

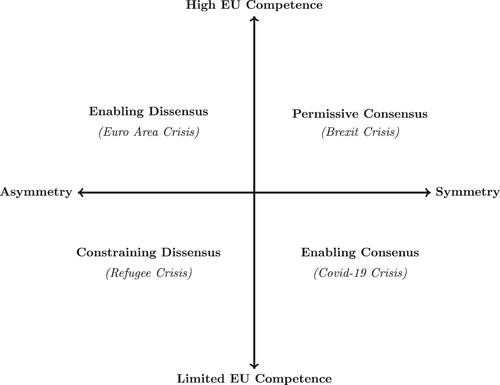

In the attempt to do so, this article aims to exploit the variation of crisis experiences in Europe over the past decade. The paper asks the following research question: what kind of policymaking processes are generated by EU crises of different nature? To address this question, the paper argues that different theories of European integration have varying power in explaining crisis policymaking in the EU depending on the specific nature of the crisis pressures to which the EU polity is subject. In our theoretical framework, we emphasize the importance of variations in the policy heritage (i.e., the degree of EU competence) and spatial distribution (i.e., the degree of symmetry) of pressures emanating from a crisis. Our conceptualization of policymaking processes focuses on the extent to which varying crisis pressures activate opportunity structures for the exercise of supranational capacity and stimulate patterns of EU politicization in crisis resolution.

Drawing on several recent studies (e.g., Börzel & Risse, Citation2020; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2021; Kuhn & Nicoli, Citation2020; Schimmelfennig, Citation2018), we theorize that diverse combinations of crisis pressures generate four ideal-typical decision-making scenarios in the EU, each of which can be best accounted for by a different combination of analytical insights from neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, postfunctionalism, and federalism. The proposed typology of crisis politics in the EU offers a synthesis of different theoretical approaches. Such a synthesis, we argue, is able to capture the essence of multilayered structures of opportunities and constraints for governments and institutional actors in the process of crisis resolution. We highlight the added value of our typology in relation to the crises of the euro area, refugees, Brexit and Covid-19.

The next section highlights the research gap we aim to address with this paper and discusses the approach we adopt to make a theoretical contribution on crisis policymaking in the EU. The third and fourth sections elaborate on the two main analytical dimensions of cross-crisis variation considered in this article. Opening up the typological space generated by these two analytical dimensions, the fifth section identifies four scenarios of crisis decision-making in the EU, which help account for patterns of policymaking in the four most disruptive crises faced by the EU since 2010. The final section summarizes our argument and points to further avenues of research.

Uncovering variation in crisis-led integration

How do different crisis situations influence the decision-making processes of the EU and the outcomes of European integration? Although the multiple crises of the 2010s seem to have validated the functionalist prediction of ‘integration through crises’, the question about the link between crises and integration remains open (e.g., Degner, Citation2019; Saurugger, Citation2016). As we discuss in detail in the Online Appendix, the four major theories of European integration we consider in this paper – i.e., neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, postfunctionalism, and federalism – have different analytical strengths and weaknesses in explaining crisis-induced integration in the EU.

There is critical variation in the success of different theoretical approaches to explain crisis-induced integration over the past decade. Importantly, the varying analytical leverage of major schools of European integration seems to be dependent on contextual features engendered by each crisis. Yet, most scholars have engaged in theoretical conversations predominantly by means of ‘competitive testing’ – namely, attempting to confirm some theories and refute others (Jupille et al., Citation2003, pp. 19–20) – without speculating on possible crisis-specific scope conditions for the applicability of each framework. While theories of European integration have been widely applied to study crisis-led integration outcomes in the 2010s, there has been little attempt to systematically theorize how heterogenous crisis situations may activate varying policymaking processes leading to different patterns of European integration. Surprisingly, we have no theory of crisis-driven integration as a function of the combinations of crisis pressures faced by the EU.

Departing from standard competitive testing, in this paper, we follow a different model of theoretical dialogue and adopt a ‘domain of application’ approach: this model of theoretical inquiry ‘works by identifying the respective turfs and ‘home domains’ of each theory’ and ‘by bringing together each home turf in some larger picture’ (Jupille et al., Citation2003, p. 21). In our framework, we leverage differences in crisis pressures to identify the domain of application of major theories of European integration in times of crisis. By defining complementary domains of application for each theory, we aim to build an additive theoretical construct that is more comprehensive than the partial representations offered by separate integration theories.

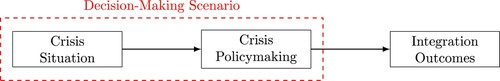

Our argument rests on the premise that different crisis characteristics provide European integration theories with heterogenous analytical leverage to explain the EU politics of crisis resolution and its ensuing integration outcomes. Our conceptualization is based on a distinction between crisis situations, crisis policymaking, and integration outcomes. provides a visualization of a simple causal pathway linking the occurrence of a crisis to crisis-induced integration outcomes.

The crisis situation corresponds to the extraordinary moment of urgency and uncertainty that poses an immediate threat to the proper functioning of the policy domain challenged by the crisis in one or more EU member states. The crisis situation, in turn, activates specific response modes and policymaking patterns. We focus on two main features of variation of policymaking processes in times of crisis. First, we examine which actors are empowered in the process of crisis resolution, distinguishing between processes in which supranational institutions play a central and autonomous role and those in which this role is retained by national governments. Second, we consider the degree of politicization of the crisis resolution process, distinguishing between contexts of low and high politicization of European integration across EU member states.

We refer to the specific policymaking context generated by a crisis situation as a ‘decision-making scenario’. In this decision-making scenario, policymakers will make decisions producing policy outputs to tackle the crisis. The (intended or unintended) consequences of these policies will determine the presence or absence of institutional innovations at the EU level, which constitute the integration outcomes and may take the form of regulatory changes and/or new capacity building.

In this paper, we focus on providing greater conceptual clarity to the first step of this causal chain. In doing so, we take inspiration from insights and perspectives provided by four major theoretical frameworks of European integration, namely neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, postfunctionalism and federalism. We claim that different theories of European integration have varying power in explaining the policymaking patterns of EU politics, depending on the diverse nature of crisis situations. To shed light on these explanatory differences, it is important to explore how crisis situations vary. This variation is the product of the different crisis pressures to which the EU polity is exposed. When employing the term ‘crisis pressures’, we refer to both functional and political challenges originating from ‘real world’ conditions which beseech policymakers’ attention.Footnote1

A crisis situation sets the stage for the further development of the crisis and is generated by specific crisis pressures. Many features of crisis pressures may characterize the crisis situation. In this paper, we propose to focus on two analytical dimensions. First, the crisis situation is policy-domain specific and is defined by the policy heritage activated by a given crisis. We distinguish between crisis pressures affecting policy domains in which the EU has high competence and crises in which the competence of the EU is low. Second, the crisis situation may differ based on the spatial distribution of the pressures prompting policymakers to engage in an out-of-the-ordinary response. We counterpose asymmetrical and symmetrical crisis pressures, based on whether all member states experience a similar crisis situation vis-à-vis a context in which some member states are hit disproportionately more than others. The next two sections conceptualize the ways in which these two dimensions of crisis pressures shape the policymaking setting of a crisis in the EU.

Policy heritage and supranational capacity

The policy heritage consists of the accumulated policies in a specific domain. As argued by a large literature, one of the principal factors affecting policy at time t + 1 is policy at time t: policy responds less directly to social and economic conditions than it does to the consequences of past policy (Heclo, Citation1974). Past policies can create a situation of path dependence that limits the available choices for policymakers to make future policy decisions; policy legacies generate institutional routines and procedures that force decision making. In particular, they impose directions by eliminating or distorting the range of available policy options (Pierson, Citation2004).

In the multi-level polity of the EU, the policy heritage may refer to the levels of both domestic and EU politics. Here, we focus on the EU level, which provides us with greatest leverage to differentiate between theories of European integration. The role of the EU in a given policy domain is characterized in terms of competences (i.e., tasks), regulatory power and core state capacities. All the crises of the 2010s required the exercise of core state powers, namely the centralized capacity to mobilize resources in policy areas that are essential for the functioning of the modern state (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2014, Citation2016). However, these crises differed with respect to the capacity of EU institutions to do so. Our analytical dimension of policy heritage hinges upon the distinction between the policy fields that fall under the direct and (quasi-)exclusive competence of the EU and those that remain within the remit of the member states.

Hence, the analytical dimension of policy heritage characterizes the vertical division of power between supranational actors and member states in a given crisis situation. This dimension corresponds to one of the two key explanatory factors put into evidence by neofunctionalism, namely the presence of a critical supranational capacity requiring ‘both autonomous decision-making powers of the supranational organizations and the resources to mitigate intergovernmental distributional conflict and transnational pressure’ (Schimmelfennig, Citation2018, p. 986). On this dimension, we distinguish between crisis-related policy domains in which the EU has high competence and the EU supranational institutions can independently mobilize resources to execute problem solving, and policy domains where the competence of the EU is low and supranational institutions have lower capacity to tackle the crisis.

By using the term ‘policy heritage’ to distinguish between policy areas of high and low EU competence, we take inspiration from the tradition of historical institutionalism and emphasize two aspects of the distribution of power in the institutional framework of the EU: (a) the policy-specificity of this distribution of power, and (b) its path-dependency. The accumulation of past policies generates specific repertoires of governance which guide the actors’ behavior telling them ‘what is going on out there’ and ‘what they should do next’ (Geddes, Citation2021). The distinction between high and low EU competence can be seen as the result of past policy failures and institutional innovations, which may be subject to interpretation and change over time. Examples of crisis-related areas in which the EU has traditionally had high competence are economic policies related to the single market (e. g. state aid and exemptions from the single market rules) and monetary policy. Instead, examples of crisis-related policy domains in which the competence of the EU has been low are immigration, public health and fiscal policy.

This distinction has important implications for crisis resolution. Indeed, in policy areas where the EU has high competence, it will be more likely for European institutions to be situated at the heart of the crisis resolution process. As suggested by Schimmelfennig (Citation2018), when the EU has high competence in a policy domain that is directly affected by the crisis, supranational organizations, most notably the European Commission and the European Central Bank (ECB), have both the autonomy and resources to preserve and expand supranational integration. Instead, where the EU competences are low, European institutions lack the capacity to make an independent impact on crisis management.

This constitutes one of the main lines of tension between neofunctionalism and intergovernmentalism. The intergovernmentalist perspective insists that member states limit the potential for autonomous supranational action and allow it to go only so far. Governments will seek to reassert their control over outcomes, when these threaten to make governments look bad in the eyes of influential constituencies (Kleine & Pollack, Citation2018, pp. 1499–1500). As argued by Moravcsik, supranational entrepreneurship is ‘rarely decisive’ (Moravcsik, Citation2005, pp. 362–363) and often ‘late, redundant, futile, and sometimes even counterproductive’ (Moravcsik, Citation1999, pp. 269–270). Instead, neofunctionalism stresses the consequential and independent role of supranational institutions in the promotion of European integration (Sandholtz & Stone Sweet Citation2012).

Therefore, we argue that the policy heritage activated by the pressures exerted by a crisis determines the relative analytical leverage of neofunctionalism vis-à-vis intergovernmentalism in the explanation of crisis-specific policymaking dynamics. Building on the argument proposed by Schimmelfennig (Citation2018), when crisis pressures affect a policy domain in which the competence of the EU is high, we expect to observe crisis policymaking processes that are more prone to enabling supranational institutions to intervene in the management of the crisis. This will be reflected in the centrality and autonomy of supranational institutions in the process of crisis resolution. This policymaking dynamic is attributable to key expectations from neofunctionalism. Instead, when crisis pressures affect policy domains in which the EU has low competence, we expect to observe a lower potential for centrality and autonomy of supranational intervention in the process of crisis resolution, with member states remaining in control of crisis management in intergovernmental fora. This policymaking dynamic is attributable to key expectations from intergovernmentalism.

Hypothesis 1a (EU Competence: Limited): Consistent with intergovernmentalism, in crisis situations characterized by pressures in policy domains of low EU competence, supranational institutions are less likely to play a central and autonomous role in the process of crisis resolution.

Hypothesis 1b (EU Competence: High): Consistent with neofunctionalism, in crisis situations characterized by pressures in policy domains of high EU competence, supranational institutions are more likely to play a central and autonomous role in the process of crisis resolution.

Spatial distribution and politicization

The second analytical dimension we focus on is the spatial distribution of crisis pressures. Crises are likely to increase interdependence among EU member states and produce particularly strong demands for policy coordination and intense preferences related to the incurred costs and losses (Schimmelfennig, Citation2018). Importantly, they may do so in an asymmetrical way. Member states may not be exposed to an EU crisis to a similar extent. An uneven exposure to a crisis creates a differential burden of adjustment. The greater the expected differential is in the EU multi-level polity, the more asymmetrical is the spatial distribution of crisis pressures. When there is high heterogeneity in the degree of crisis pressures experienced by different member states, an asymmetrical crisis scenario takes place. Instead, when all the member states are exposed to similar crisis pressures, the crisis produces a symmetrical scenario.Footnote2

We expect the spatial distribution of crisis pressures to directly affect policymakers’ perceptions of the tradeoff between the functional scale of governance and the territorial scope of community that lies at the heart of postfunctionalist theory (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009). In their recent work on the Covid-19 crisis, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs (Citation2021) have argued that ‘the direction and slope of the postfunctionalist tradeoff is issue-dependent’ and contingent factors that trigger empathy with aliens may expand the expectations of community to the transnational level. This raises the general question of what issues and contingent factors may facilitate empathy in EU crises. We posit that the presence of a common, symmetrical threat experienced by all the member states of the EU multi-level polity is a powerful driver of expanded expectations of community to the transnational level.

This argument resonates with contributions focused on the political economy of risk sharing. In particular, Schelkle (Citation2017) highlights a ‘paradox of diversity’ that can be easily translated to the context of EU crises. The diversity of member states’ exposure to a crisis makes mutual risk sharing more economically beneficial thanks to a negative correlation of risk, but also more difficult to achieve politically, as the lucky member states have an incentive to question the merit of unlucky members’ demands. Instead, a more balanced exposure to a crisis may facilitate a shared acknowledgement that the member states are part of a community of risk in which each member can identify with the situation of being unfortunate (Baldwin, Citation1990, pp. 24–31). Put differently, the effect of a symmetrical exposure to a crisis is somewhat paradoxical. In insurance terms, a symmetrical shock can only be shared with future generations, through public debt. If it has to be shared between current members, it raises distributive issues: if all are badly affected, do those who were more vulnerable before disaster struck deserve more support? Their expectation to receive support that makes up for their vulnerability may meet with resistance on the part of the better off to being asked for redistribution just when they find themselves in a dire situation. However, politically, the exposure to a symmetrical shock promotes the notion of solidarity as a kind of reciprocity among EU member states. This is especially true if the relative position of member states in the distribution of risks from a crisis shock is highly uncertain, namely in the presence of a ‘veil of ignorance’ over the benefits and costs of mutual insurance (for a theoretical account of European solidarity in these terms, see Sangiovanni, Citation2013). As a result, symmetry may increase the potential for recognition of reciprocal benefits from risk sharing, which is a powerful driver of solidarity in a union of diverse members (Cicchi et al., Citation2020).

The idea that greater symmetry of exposure to crisis pressures may reduce political contestation and polarization in the EU is also consistent with recent studies on the politics of European identities. As argued by (Börzel & Risse, Citation2020, p. 29), while collective identification with one’s nation and with Europe has remained broadly stable over the past decades, what has changed over time is the degree to which political elites have mobilized exclusive national identities to sway public opinion both in favor and against coordination and integration at the EU level. At the same time, as Kuhn and Nicoli (Citation2020, p. 5) point out, collective identities are complex, multilayered phenomena. The way in which collective identities relate to each other can vary across time and space and is context-dependent. Due to the ambivalence and context-dependence of identity politics in the European integration process, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the degree to which political actors can mobilize exclusive national identities in a crisis hinges upon the degree of symmetry and commonality of the crisis experience. Collective identification may redesign the boundaries between deserving in-groups and less deserving out-groups: as ‘bonding’ and ‘bounding’ go hand in hand (Ferrera, Citation2005), the shared experience of a crisis that hits symmetrically all EU member states may reduce the salience of the constraint posed by national identities and facilitate an extension of transnational solidarity.

These considerations are in line with a key insight from the work on federalism as a theory of regional integration by William H. Riker and David McKay, who characterize federations as a result of a bargain between central and regional elites intent on averting common existential threats.Footnote3 As McKay (Citation1999, pp. 23–28) notes, the ‘federal bargain’ among some political units does not require the presence of a pre-existent common culture or identity. By contrast, if a threat is perceived by the elites of all units involved in the supranational polity, it is possible to overcome conflict and perform collective action that involves a federal upgrading of the supranational polity. Extending the argument of Riker and McKay, we posit that the presence of symmetrical crisis pressures common to all EU member states triggers processes of de-politicization of national identities. A symmetrical crisis may expand ‘expectations of community to the transnational level as empathy with the worst affected member states le[a]d[s] to vocal calls for more EU solidarity and leadership’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2021, p. 351). These conditions generate a reversal of the postfunctionalist paradigm, for which the fragmentation of national identities plays a constraining role on the ability of policymakers to solve collective action problems in the presence of functional pressures.

Hence, we argue that the spatial distribution of crisis pressures shapes the patterns of politicization in the crisis resolution process and determines the relative analytical leverage of postfunctionalism vis-à-vis federalism. Building on the argument proposed by Genschel and Jachtenfuchs (Citation2021), when the spatial distribution of crisis pressures is symmetrical, we expect the crisis to catalyze an empathy logic, which lowers the politicization of national identities. This will be reflected in a relatively lower politicization of European integration in the crisis resolution process. This policymaking dynamic is attributable to key expectations from federalism à la Riker-McKay. Instead, when the spatial distribution of crisis pressures is asymmetrical, we expect the crisis to catalyze an identity logic, which heightens the politicization of European integration and generates greater dissensus across EU member states around the process of crisis resolution. This policymaking dynamic is consistent with key expectations from postfunctionalism.

Hypothesis 2a (Spatial Distribution: Asymmetrical): Consistent with postfunctionalism, in crisis situations characterized by an asymmetrical distribution of crisis pressures within the EU, the politicization of the process of crisis resolution is likely to be higher.

Hypothesis 2b (Spatial Distribution: Symmetrical): Consistent with federalism, in crisis situations characterized by a symmetrical distribution of crisis pressures within the EU, the politicization of the process of crisis resolution is likely to be lower.

Crisis pressures and decision-making scenarios

By cross-tabulating the two major analytical dimensions of crisis pressures identified in the previous section, we produce a novel typology of decision-making scenarios in times of crisis. provides an overview, which indicates the illustrative crisis examples we discuss in this section.

The subsequent discussion of this typology relies on descriptive case studies. We adopt a ‘diverse’ approach to case selection and aim to identify cases that exemplify common patterns of theoretical interest (Gerring, Citation2017). To select our cases, we choose four crises which, in our view, exhibit the greatest degree of variation across the two analytical dimensions identified in the previous section. In discussing these cases, we try to offer an empirical account aimed at illustrating the value of our theoretical contribution. This account rests on secondary sources. We leave a more detailed empirical assessment, which would not be possible the short space of this article, for future work.

Constraining dissensus: the refugee crisis

We start from the description of the bottom left quadrant, presenting a crisis situation characterized by limited EU competence and asymmetrical distribution of crisis pressures. The low capacity and lack of policy resources of supranational institutions in the policy domain of the crisis make crisis resolution highly dependent on decision making in intergovernmental fora. In line with intergovernmentalist predictions, we would expect supranational entrepreneurship to be ‘rarely decisive’ in this crisis situation (Moravcsik, Citation2005, pp. 362–363). At the same time, the potential for agreement, coordination and joint action at the intergovernmental level is constrained by the politicization of national identities produced by the uneven distribution of crisis pressures within the EU polity. Consistent with the predictions of postfunctionalism, the tension between the uneven distribution of costs and benefits of crisis resolution at the international level and the limited scope of community feelings at the national level will make opposition to EU policy proposals more vocal.

The joint presence of intergovernmental crisis resolution and heightened politicization of national identities will act as a powerful constraint on the crisis policymaking process, making minimum common denominator solutions based on narrowly defined member states’ preferences more likely. This decision-making scenario is consistent with the postfunctionalist notion of ‘constraining dissensus’. The highly politicized and conflictual intergovernmental setting of crisis resolution makes joint policymaking initiatives and collective action solutions harder to achieve.

This decision-making scenario fits the policymaking patterns of the 2015 refugee crisis. This crisis concerned the domain of migration and asylum policy, in which the EU’s role is still subsidiary to the decisions of its member states. Member states regulate admissions of third-country nationals and decide the amount of resources they are willing to invest in asylum policy (Geddes & Scholten, Citation2016; Schain, Citation2009). In this crisis, the member states were asymmetrically hit, with Mediterranean frontline states being stricken most directly and open destination states carrying the bulk of the burden of protecting asylum-seekers (Kriesi et al., Citation2021). In this context, radical right-wing parties, such as the Freedom Party in Austria, the AfD in Germany, the Sweden Democrats in Sweden, Fidesz in Hungary or the Northern League in Italy, had a strong opportunity to foster their anti-establishment claims, stressing the need to secure external borders and restore national sovereignty.

As a result, in line with intergovernmentalist predictions, policymaking in the refugee crisis was characterized by a purely intergovernmental process of crisis resolution. This was required by the lack of significant competence and capacity of EU institutions in the domain of the crisis. The policymaking was characterized by hard-nosed bargaining and ended up being stalled due to the perceived divergence of interests among asymmetrically exposed EU member states. Consistent with the postfunctionalist framework and the notion of ‘constraining dissensus’, irreconcilable divergences in intergovernmental fora were catalyzed by the high degree of politicization of identarian issues both between and within member states. In the absence of any joint burden sharing in the refugee crisis, the only possible joint measures concerned attempts to externalize the problem – a policy process that led to the stop-gap solution of the EU-Turkey agreement in spring 2016. Ultimately, the refugee crisis resulted in minimal advancement of the institutional architecture of the EU and no significant deepening of European integration (Schimmelfennig, Citation2018).

Enabling dissensus: the euro area crisis

The upper left quadrant presents a crisis situation in which asymmetrical pressures affect a policy domain that falls under the direct competence of EU institutions. Here, the high capacity and presence of policy resources held by supranational institutions makes the crisis management process less reliant on the decisions of EU member states in intergovernmental fora. In this setting, consistent with neofunctionalist predictions, the entrepreneurship of supranational institutions has greater potential to shape the policy outputs and integration outcomes of the process of crisis resolution. However, this process remains highly conflictual, with dissensus being catalyzed by the activation of national identities stemming from the uneven exposure of member states to crisis pressures. As predicted by postfunctionalism, public attention is liable to politicize the EU-level decision-making process, which imposes limits on the problem-solving capacity of state actors.

As suggested by Bressanelli et al. (Citation2020, p. 331), while postfunctionalists tend to see politicization as a constraint for functional problem solving, politicization may also work as an enabling mechanism for political and institutional actors to advance their substantive goals. This, we argue, is the case in this scenario: the intergovernmental impasse generated by high politicization and inter-state conflict provides supranational institutions with an opportunity to extend the scope of their competences and bolster their long-term survival. This decision-making scenario is consistent with Bressanelli et al.’s (Citation2020) notion of ‘enabling dissensus’. High politicization of crisis resolution makes it more difficult to pursue joint-action initiatives at the intergovernmental level. In turn, intergovernmental dissensus provides supranational institutional actors with greater responsibility to tackle a crisis that falls directly under the scope of their mandate.

This decision-making scenario comes closest to the policymaking patterns of the 2010–12 crisis of the euro area. The euro area crisis was characterized by pressures in the domain of fiscal, monetary and supervisory policy, with experts disagreeing about the relative importance of issues in these different domains (Ferrara, Citation2020). Due to the monetary and financial dimension of the crisis, the ECB had large stakes and competence in the process of crisis resolution. Moreover, crisis pressures were highly asymmetrical. Panic in government bond markets started in Greece at the end of 2009 and spilled over to Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy over the following months, while other member states (e.g., Germany, the Netherlands) were financially stable, but worried about the stability of the euro (Finke & Bailer, Citation2019). The uneven exposure to the crisis catalyzed domestic politicization, as Eurosceptic parties thrived on their opposition against bailouts in the North and against austerity in the South (Schimmelfennig, Citation2018, p. 979). An unprecedented degree of politicization of national identities was well expressed by the prevalence of crisis narratives about ‘northern saints’ and ‘southern sinners’ (Matthijs & McNamara, Citation2015).

Consistent with the predictions of postfunctionalism, the high degree of politicization of the crisis made it impossible to agree on resolutive crisis responses at the intergovernmental level. Intergovernmental initiatives to tackle the crisis pitted northern European surplus countries, led by Germany, against southern European deficit countries (Schimmelfennig, Citation2015) and proved manifestly insufficient to promote effective and legitimate crisis solutions (Fabbrini, Citation2013; Jones et al., Citation2016). Due to this intergovernmental impasse and in the absence of a centralized fiscal authority that could act as a lender of last resort to sovereigns, the ECB soon emerged to provide the risk-sharing solution that was needed to stop the crisis escalation and preserve the integrity of the euro area (Schelkle, Citation2017). In line with neofunctionalist predictions, the critical supranational capacity of the ECB in the policy domain of the crisis put the institution at the heart of the crisis resolution process. The dissensus among EU member states acted as an ‘enabling’ stimulus for supranational action. Indeed, the slow moving intergovernmental response to the crisis created a ‘vacuum [that] forced the ECB, the only institution in the euro area capable of intervening promptly and decisively, into territory far outside its custom and practice’ (Economist, Citation2011).

Permissive consensus: the Brexit crisis

The upper right quadrant regards a crisis exerting symmetrical pressures on a policy domain in which the competence of the EU is high. Similar to the upper left quadrant and consistent with the predictions from neofunctionalism, the high degree of competence allows supranational entrepreneurship to play a central role in crisis management. At the same time, the joint exposure to the crisis of all EU member states weakens the potential for national identities to become highly politicized in the process of crisis resolution. The perception of being part of a ‘community of fate’ by European elites and citizens is likely to be higher, thereby rendering consensus-based decision making more likely. The symmetrical exposure to crisis pressures enhances the potential for a common acknowledgement of the crisis constituting a threat for the EU polity as a whole. Consistent with the predictions advanced by federalism theory, this represents the key condition for federal unity and integrity to occur.

The joint presence of high supranational capacity and the low degree of politicization of national identities generates a scenario in which supranational elites assume a leadership role in tackling the crisis, underpinned by consensual views expressed by the heads of state. We see this scenario as one of ‘permissive consensus’: joint-action initiatives are favored by the low contentiousness of the crisis resolution process among citizens and politicians. Given the policy resources enjoyed by EU institutions in the policy domain of the crisis, the delegation to, and involvement of, supranational institutional actors is a feature of crisis policymaking in this case.

This decision-making scenario best represents EU policymaking during the Brexit crisis, triggered by the 2016 EU membership referendum in the United Kingdom. The crisis fell under the direct competence of EU institutions, as the withdrawal procedure determined by Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon involves EU institutions rather than member states (Hillion, Citation2018, p. 29). In this context, a pivotal role was played by the Commission, with its Article 50 Task Force (Laffan, Citation2019, pp. 18–21). Furthermore, Brexit exerted much more symmetrical pressures on EU member states than the euro area and refugee crises. While it is true that some countries, such as Ireland, Germany and the Netherlands, were more economically exposed to the economic costs of Brexit (Chen et al., Citation2018), the biggest risk was political. The UK referendum could provide Eurosceptic parties with momentum in the remaining member states, potentially leading to further attempts among the EU-27 to exit the EU (De Vries, Citation2017). Hence, in the immediate aftermath of the vote, Brexit was perceived as a generalized threat to the very existence of the Union (Laffan, Citation2019, p. 14).

These conditions produced an unexpectedly consensual policymaking process among the EU-27 under the leadership of the Commission. Consistent with neofunctionalist theory, the high competence and policy resources of the European Commission are an important factor in explaining the unity of the EU-27 (Jensen & Kelstrup, Citation2019, pp. 30–31). But at the same time, in line with predictions from federalism à la Riker-McKay, the sense of unity and common EU identity was reinforced by strong in-group feelings among EU-27 elites, underpinned by the idea that the single market signifies common European values in both economic and symbolic terms (Jensen & Kelstrup, Citation2019, pp. 33–34). The notion of ‘permissive consensus’ in the Brexit crisis is also consistent with the dynamics of public opinion regarding Brexit negotiation in the EU. As shown by Walter (Citation2021), a unitary stance was supported by the wider EU-27 public, which unsentimentally favored a negotiating line safeguarding the perceived common interest of the EU-27 block.

Enabling consensus: the Covid-19 crisis

Finally, the bottom right quadrant depicts a crisis situation characterized by symmetrical pressures in a domain of low EU competence. Here, the crisis-tackling capacity of EU institutions is lower, given that the policy domain of the crisis falls outside the direct focus of their mandate. Consistent with an intergovernmentalist framework, we would expect heads of state to remain in full control of the crisis resolution process, while an ancillary role is played by supranational institutions. Simultaneously, the presence of joint crisis exposure across the EU makes the activation of national identities less likely and the potential for consensus among member states much higher than in the crisis situation depicted in the bottom left corner. The common threat makes public opinion and elites more favorable to strike a ‘federal bargain’ to preserve the integrity of the EU polity.

This set of crisis-specific factors determines the presence of a highly intergovernmental process of crisis management, coupled with a high degree of public support for joint action in domains that remain at the heart of the sovereignty of EU member states. We see this scenario as one of ‘enabling consensus’. This setting offers the greatest potential for policy outputs and institutional innovations pushing federal integration to new directions, which demand the shared approval of democratically elected heads of state. This decision-making scenario captures key aspects of policymaking during the 2020 Covid-19 crisis.

This crisis had an immediate two-fold incidence, affecting both the public health and economic domain. Fighting the crisis primarily required non-pharmaceutical interventions to slow the spread of the virus and measures of fiscal support to the real economy hit by lockdowns, both being prerogatives of member states. All member states experienced a dramatic economic fallout from the lockdown measures in response to the spread of the virus, although the EU’s South suffered more in economic terms. But more importantly, in contrast to the euro area crisis, the potential for the politicization of crisis resolution remained lower and the North responded with considerable empathy. Arguably, the difference between the two crises lies in the symmetry with regard to the public health dimension of the Covid-19 crisis. This concept is well expressed by the famous letter of nine heads of state to the President of the European Council on 25 March 2020, asking for an extension fiscal solidarity in the EU and arguing the Covid-19 crisis is ‘a symmetric external shock, for which no country bears responsibility’. As a result, while an exclusive focus on debt blocked European solidarity in the euro area crisis, ‘the fusion of debt and disease unblocked solidarity’ in the Covid-19 crisis (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2021, p. 365).

Despite the initial divisions among EU member states, the common health crisis generated an extension of in-group feelings inside the EU. This was reflected and stimulated by a discursive turn towards ‘polity maintenance’ and ‘communtarian’ symbols in the public communication of EU leaders (Ferrera et al., Citation2021). The emergence of ‘we-feelings’ provided a window of opportunity for an ‘enabling consensus’ pushing EU policymaking to an unexpected direction of collective action in the fiscal domain, which had been impossible to attain in the euro area crisis. Consistent with the expectations of intergovernmentalism, the policy process in the domain of fiscal integration was driven by the Franco-German engine, with a key role played by the European Council. The strength of the leadership exerted by France and Germany in crafting intergovernmental consensus appeared to go well beyond the one documented by Degner and Leuffen (Citation2019) and Schild (Citation2020) in the euro area crisis. Contrary to what happened during the euro area crisis and consistent with federalism theory, in the presence of the common existential threat posed by the pandemic, consensus dynamics emerged relatively soon. It took member states only about five months to reach consensus around a European fiscal response to the crisis, linking the Recovery fund to the new EU budget and marking a massive expansion of EU fiscal solidarity.

summarizes the main features and illustrative crisis examples of the four outlined decision-making scenarios. In the next section, we draw conclusions and highlight potential directions for future research.

Table 1. Features of Decision-Making Scenarios.

Conclusion

Most of the literature on European integration in times of crisis has relied on ‘competitive testing’ of single theories of European integration. Different from previous studies, this paper has adopted a ‘domain of application’ approach, and has offered a theoretical synthesis yielding greater analytical leverage in the interpretation of EU crisis politics than the one provided by the partial representations of separate integration theories. The article has argued that exposure to crisis pressures of different nature generates distinct patterns of crisis policymaking in the EU. Variations in the policy heritage and spatial distribution of crisis pressures provide different theoretical approaches with varying analytical leverage to explain the policymaking dynamics of EU crises. By cross-tabulating the two highlighted dimensions of crisis pressures, we have produced an analytical space of four EU decision-making scenarios in times of crisis, each of which combines analytical insights from neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, postfunctionalism and federalism. We have discussed the added value of the proposed typology in relation to four major EU crises over the past decade. In proposing this framework, the paper has attempted to advance the theoretical debate on crisis-led integration in the EU.

Future research may extend the analysis of this paper in several directions. In our view, four are particularly interesting. First and foremost, while our framework focuses on the relationship between crisis pressures and policymaking dynamics, a natural step forward would be to link policymaking dynamics to policy outputs, institutional innovations and long-term outcomes for the EU polity. We see this paper as the first building block for a more encompassing theoretical construct linking crisis pressures and integration in the EU. Second, the empirical assessment of the validity our framework should be deepened to include a more systematic analysis of actor networks and politicization dynamics in different crisis situations. Third, our framework could be extended to consider other analytical dimensions of interest regarding crisis pressures, such as the time horizons of causes and effects of crisis shocks in the EU. Moreover, its application could span other crisis events, such as the Ukrainian crisis of 2014, the post-2008 social crisis of poverty and inequality across EU member states, and the recent crisis of liberal democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. Fourth, the proposed framework can be used as a theoretical benchmark to be compared with other potentially competing explanations of how member states deal with EU crises. For instance, our focus on crisis pressures may be fruitfully juxtaposed with other theoretical approaches centered on the role of time-dependent factors, such as policymakers’ learning across different EU crises.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (21.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Federico Maria Ferrara

Federico Maria Ferrara is a postdoctoral research officer at the European Institute at the London School of Economics, London, UK, where he works in the Synergy project SOLID, ERC-2018-SyG, 810356.

Hanspeter Kriesi

Hanspeter Kriesi is part-time professor at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy, where he works in the Synergy project SOLID, ERC-2018-SyG, 810356.

Notes

1 We remain agnostic as the extent to which crisis pressures are socially constructed. We acknowledge that political actors may have heterogenous incentives in portraying functional pressures as a crisis phenomenon, as highlighted by a burgeoning literature on ‘crisisification’ and ‘emergency politics’ in the EU (e.g., White, Citation2019; Rhinard, Citation2019). Also, our notion of ‘crisis pressures’ collapses into the same analytical construct problem pressures stemming from the functional dimension of policy issues and political pressures emanating from issue salience and political entrepreneurship. Admittedly, these are important elements that deserve greater theoretical scrutiny and development, but they go beyond the scope of this paper.

2 In our framework, the notions of symmetry and asymmetry are used in reference to crisis exposure, and not necessarily in reference to crisis consequences. We acknowledge that an ex ante symmetrical exposure to a common shock may produce ex post asymmetrical consequences in a pool of diverse members (e.g., Covid-19 crisis). Similarly, when there is high interdependence, ex ante asymmetry can translate into high ex post symmetry (e.g., euro area crisis). Yet, we see the structuring of crisis politics in the EU as primarily driven by the ex ante condition.

3 For a more encompassing discussion of Riker’s and McKay’s federalism theory, see the Online Appendix.

References

- Baldwin, P. (1990). The Politics of Social Solidarity. Cambridge University Press.

- Börzel, T. A., & Risse, T. (2020). Identity politics, core state powers and regional integration: Europe and beyond. Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12982

- Bressanelli, E., Koop, C., & Reh, C. (2020). EU actors under pressure: Politicisation and depoliticisation as strategic responses. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1713193

- Chen, W., Los, B., McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., Thissen, M., & van Oort, F. (2018). The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of the channel. Papers in Regional Science, 97(1), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12334

- Cicchi, L., Genschel, P., Hamerijck, A., & Nasr, M. (2020). ‘EU solidarity in times of Covid-19’, Policy Briefs, 2020/34, European Governance and Politics Programme.

- Degner, H. (2019). Public attention, governmental bargaining, and supranational activism: Explaining European integration in response to crises. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(2), 242–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12686

- Degner, H., & Leuffen, D. (2019). Franco-German cooperation and the rescue of the eurozone. European Union Politics, 20(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518811076

- De Vries, C. (2017). Benchmarking Brexit: How the British decision to leave shapes EU public opinion. Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(S1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12579

- Economist (2011) ‘The European Central Bank: ready for the ruck?’. https://www.economist.com/briefing/2011/10/22/ready-for-the-ruck (22 October 2011, accessed 1 March 2021).

- Fabbrini, S. (2013). ‘Intergovernmentalism and its limits: Assessing the European Union’s answer to the euro crisis’. Comparative Political Studies, 46(9), 1003–1029. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013489502

- Ferrara, F. M. (2020). The battle of ideas on the euro crisis: Evidence from ECB inter-meeting speeches. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(10), 1463–1486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1670231

- Ferrera, M. (2005). The Boundaries of Welfare: European Integration and the New Spatial Politics of Social Protection. Oxford University Press.

- Ferrera, Maurizio, Miró, Joan, & Ronchi, Stefano. (2021). Walking the road together? EU polity maintenance during the COVID-19 crisis. West European Politics, 44(5-6), 1329–1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1905328

- Finke, D., & Bailer, S. (2019). Crisis bargaining in the European Union: Formal rules or market pressure? European Union Politics, 20(1), 109–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518814949

- Geddes, A. (2021). Governing Migration Beyond the State: Europe, North America, South America and Southeast Asia in a Global Context. Oxford University Press.

- Geddes, A., & Scholten, P. (2016). The Politics of Migration and Immigration in Europe. SAGE Publications.

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2014). Beyond the Regulatory Polity? The European Integration and Core State Powers. Oxford University Press.

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2016). More integration, less federation: The European integration of core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1055782

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2021). Postfunctionalism reversed: Solidarity and rebordering during the corona-crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(3), 350–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881588

- Gerring, J. (2017). Qualitative methods. Annual Review of Political Science, 20(1), 15–36. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-092415-024158

- Heclo, H. (1974). Modern Social Politics in Britain and Sweden: From Relief to Income Maintenance. Yale University Press.

- Hillion, C. (2018). Withdrawal under article 50 TEU: An integration-friendly process. Common Market Law Review, 55, 29–56.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2019). Grand theories of European integration in the twenty-first century. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1113–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1569711

- Jensen, M. D., & Kelstrup, J. D. (2019). ‘House united, house divided: Explaining the EU’s unity in the Brexit negotiations’. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(S1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12919

- Jones, E., Kelemen, R. D., & Meunier, S. (2016). Failing forward? The euro crisis and the incomplete nature of European integration. Comparative Political Studies, 49(7), 1010–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015617966

- Jupille, J., Caporaso, J. A., & Checkel, J. T. (2003). Integrating institutions: Rationalism, constructivism, and the study of the European Union. Comparative Political Studies, 36(1-2), 7–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414002239370

- Kleine, M., & Pollack, M. (2018). Liberal intergovernmentalism and its critics. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(7), 1493–1509. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12803

- Kriesi, H., Altipamarkis, A., Bojar, A., & Oana, I.-E. (2021). Debordering and re-bordering in the refugee crisis: A case of ‘defensive integration’. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(3), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1882540

- Kuhn, T., & Nicoli, F. (2020). Collective identities and the integration of core state powers: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12985

- Laffan, B. (2019). How the EU27 came to Be. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(S1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12917

- Matthijs, M., & McNamara, K. (2015). ‘The euro crisis’ theory effect: Northern saints, southern sinners, and the demise of the Eurobond.”. Journal of European Integration, 37(2), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.990137

- McKay, D. (1999). Federalism and European Union: A Political Economy Perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Moravcsik, A. (1999). A new statecraft? Supranational entrepreneurs and international cooperation. International Organization, 53(2), 267–306. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899550887

- Moravcsik, A. (2005). The European constitutional compromise and the neofunctionalist legacy. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(2), 349–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500044215

- Moravcsik, A. (2018). Preferences, power and institutions in 21st-century Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(7), 1648–1674. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12804

- Niemann, A., & Ioannou, D. (2015). European economic integration in times of crisis: A case of neofunctionalism? Journal of European Public Policy, 22(2), 196–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.994021

- Pierson, P. (2004). Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis. Princeton University Press.

- Rhinard, M. (2019). The crisisification of policy-making in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 616–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12838

- Sandholtz, Wayne, & Stone Sweet, Alec. (2012). Neo-Functionalism and Supranational Governance. In Erik Jones, Anand Menon, & Stephen Weatherill (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Sangiovanni, A. (2013). Solidarity in the European Union. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 33(2), 213–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqs033

- Saurugger, S. (2016). Politicisation and integration through law: Whither integration theory? West European Politics, 39(5), 933–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2016.1184415

- Schain, M. (2009). The state strikes back: Immigration policy in the European Union. European Journal of International Law, 20(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chp001

- Schelkle, W. (2017). The Political Economy of Monetary Solidarity: Understanding the Euro Experiment. Oxford University Press.

- Schild, J. (2020). The myth of German hegemony in the euro area revisited. West European Politics, 43(5), 1072–1094. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1625013

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2014). European integration in the euro crisis: The limits of postfunctionalism. Journal of European Integration, 36(3), 321–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.886399

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2015). Liberal intergovernmentalism and the euro area crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(2), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.994020

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2018). European integration (theory) in times of crisis. A comparison of the euro and Schengen crises. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(7), 969–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1421252

- Smeets, S., & Zaun, N. (2021). What is intergovernmental about the EU’s ‘(new) intergovernmentalist’ turn? Evidence from the eurozone and asylum crises’. West European Politics, 44(4), 852–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1792203

- Van Middelaar, L. (2020). Alarums and Excursions. Agenda Publishing.

- Walter, Stefanie. (2021). EU‐27 Public Opinion on Brexit †. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(3), 569–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.v59.3

- White, J. (2019). Politics of Last Resort: Governing by Emergency in the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Zeitlin, J., Nicoli, F., & Laffan, B. (2019). Introduction: The European Union beyond the polycrisis? Integration and politicization in an age of shifting cleavages. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 963–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619803