ABSTRACT

Employing new and original survey data collected in three waves (April/May and November 2020 as well as May 2021) in Germany, this paper studies the dynamics of individual-level support for additional health care spending. A first major finding is that, so far, health care spending preferences have not radically changed during the Covid-19 pandemic, at least at the aggregate level. A more detailed analysis reveals, secondly, that individual-level support for additional spending on health care is strongly conditioned by performance perceptions and, to a lesser extent, general political trust. Citizens who regard the system as badly (well) prepared to cope with the crisis are more likely to support (oppose) additional spending. Higher levels of political trust are also positively associated with spending support, but to a lesser degree. The paper concludes by discussing the implications of these findings for policy-making and welfare state politics in the post-pandemic era.

Introduction

The welfare state has been under pressure for a long time. In the ‘silver age’ of the welfare state (Taylor-Gooby, Citation2002), pressures of fiscal austerity related to globalization, population ageing and structural change as well as the various economic and fiscal crises of the past decades have severely limited the fiscal leeway of policy-makers to react to new challenges well before the Covid-19 pandemic hit and put health care systems under additional stress. Still, the social and economic aftershocks of the crisis are likely to restrict the fiscal leeway for social policy spending for years to come. At the same time, the Covid-19 pandemic has fueled new demands on the welfare state – not only, but potentially more forcefully in the domain of health care.

This is exactly where the contribution of this paper fits in. More specifically, I probe attitudes towards increasing health care spending during the Corona pandemic by making use of novel survey data for Germany collected in three waves in April/May and November 2020 as well as May 2021. The paper speaks to recent scholarship on the relationship between trust, performance perceptions and willingness to pay for social policy (Habibov et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Haugsgjerd & Kumlin, Citation2020; Roosma et al., Citation2014; Van Oorschot & Meuleman, Citation2012). It can also build on and expand existing work on determinants of individual-level attitudes towards health care (Jensen, Citation2011, Citation2012; Missinne et al., Citation2013; Naumann, Citation2014; Wendt et al., Citation2010; Wendt et al., Citation2011), which has provided a wealth of insights about the individual (self-interest, ideology) and institutional determinants of attitudes.

From an empirical perspective, the obvious empirical research gap that this paper addresses is that, to the best of my knowledge, there is no study yet that has studied the dynamics of health care attitudes during the Covid-19 pandemic (for an overview on this emerging field, see: Reeskens et al., Citation2021), even though some studies have started to explore the broader relationship between the pandemic and the welfare state (Ares et al., Citation2021; Baute & de Ruijter, Citation2021; Breznau, Citation2021). From a more theoretical perspective, this paper makes an important contribution to the broader debate about the association between political trust and the welfare state by testing whether the often proclaimed self-reinforcing feedback dynamic between high political trust and welfare state support holds under conditions of extreme stress, i.e., during a pandemic of historic proportions.

The core findings of this paper are the following: First, and somewhat surprisingly, the survey data show that support for additional health care spending in Germany remains high and relatively stable with a slight upward tick in the third survey wave. Second, probing deeper, I find that performance perceptions are strongly associated with support for additional health care spending in a pattern that Chung and Meuleman (Citation2017:, p. 58) label ‘improvement reaction’: Respondents who are critical of the health care system’s reaction to the pandemic are more likely to support additional spending to fix the system. Third, general political trust is also positively related to spending support, although to a lesser extent than performance perceptions.

Taken together, these findings are striking and have deeper implications for the politics of health care reform in the post-pandemic phase. As previous research has shown (Jensen, Citation2011, Citation2012), support for additional spending on health care is and remains high, but it does not seem to increase significantly during the crisis, even though a large share of the population thinks that the system was badly prepared for the crisis. This partial contradiction in public opinion might spell trouble for future discussions about health care reform after the pandemic is over. In this future scenario, proposals to increase spending on crisis prevention (which creates benefits in the long term, but less in the short term) are likely to compete with calls for short-term compensation of the negative consequences of the crisis for the economy and labor markets.

Performance perceptions, political trust and willingness to spend

There is a rich literature on the complex association between political trust and welfare state support that can only be briefly reviewed here (see Kumlin et al. (Citation2017) for a recent and more comprehensive overview). Generally speaking, researchers have identified a positive, self-reinforcing feedback relationship between political trust and more specific measures of welfare state performance on the one hand and individual willingness to support the welfare state and its further expansion on the other (Edlund, Citation2006; Gabriel & Trüdinger, Citation2011; Habibov et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Habibov et al., Citation2019b; Haugsgjerd & Kumlin, Citation2020; Hetherington, Citation2005; Kumlin, Citation2013; Lynch & Gollust, Citation2010; Rothstein et al., Citation2012; Rudolph & Evans, Citation2005; Svallfors, Citation2002; Wendt et al., Citation2010). Scholarship has studied both how generalized political trust might influence further support for the welfare state (Rothstein et al., Citation2012) as well as how performance perceptions of particular social policies in turn might increase general political trust (Cammett et al., Citation2016). In reality, both halves of the feedback loop are difficult to disentangle as they are reinforcing each other in a continuous process without a clearly dominating direction of causality. In the long term, these feedback mechanisms can accumulate to different equilibria: a first one, in which high levels of trust, well-performing governmental and welfare state institutions and public support for the welfare state positively reinforce each other, and second, a more detrimental one in which declining institutional performance might fuel political distrust and a declining willingness to further contribute to the collective goods of the welfare state (Haugsgjerd & Kumlin, Citation2020), potentially accompanied by richer citizens opting out of public social insurance schemes in favor of private solutions (Busemeyer & Iversen, Citation2020).

The Covid-19 pandemic is an exceptional situation which might set in motion such a ‘downbound spiral’ (Haugsgjerd & Kumlin, Citation2020) of declining trust and welfare state performance. The pandemic has put health care systems under extreme stress. Contested (and sometimes confused) political responses to the challenges of the pandemic in the form of unprecedented lockdown measures, involving restrictions on the free movement of people across borders and even within countries as well as the shutting down of businesses, hotels, restaurants and cultural institutions, and mounting levels of public debt might further fuel political distrust. Probing public support for additional health care spending during this critical period of extreme stress therefore holds significant implications for the study of the politics of health care and welfare state reform more broadly understood, essentially by testing the stability of the above mentioned feedback mechanism in times of heightened stress. In the following, I will develop a set of concrete hypotheses on (1) the impact of the crisis as it unfolds over time; (2) the association between performance perceptions and spending support and (3) the association between general political trust and spending support.

The impact of the crisis over time

So far, there is very little research on the impact of large-scale health crisis on attitudes towards health care, partly for the simple reason that crises of historic proportions such as the Covid-19 pandemic happen rarely. Previous work has shown that compared to other parts of the welfare state, citizen support for health care is much higher (Jensen, Citation2011, Citation2012; Jensen & Petersen, Citation2017), potentially because of deeply rooted biological and evolutionary mechanisms triggering a willingness to help the sick in need. This is different from other areas of the welfare state, in particular unemployment insurance or social assistance, as being unemployed or in poverty might also be attributed to individuals’ inaction to overcome these situations (Toikko & Rantanen, Citation2017; Van Oorschot, Citation2006).

Extrapolating from this literature, a first theoretical expectation would therefore imply a significant increase in willingness to spend on health care during the Covid-19 pandemic as the pandemic has clearly and obviously led to a strong increase in the number of people in need of health care (Hypothesis 1a). A contrasting perspective to this is given in Jensen and Naumann (Citation2016) who analyze the development of health care support during an influenza outbreak, which is arguably a crisis on a different scale compared to Covid-19. They find a negative effect on the crisis on support for health care investments, arguing that the outbreak as such might already be regarded as an indication of system underperformance, triggering a decline in trust and support. Hence, a competing hypothesis to H1a would be declining support for health care spending throughout the crisis (Hypothesis 1b).

Performance perceptions and spending support

A second issue is how individual willingness to support additional spending on health care depends on (perceived) performance of the system. To some extent, this may be a simple consequence of the extent of the crisis: If the crisis is severe, support for additional spending is likely to be given unconditionally. But if the crisis has not reached that threshold yet, spending support should vary across individuals and is likely to depend on the perceived performance of the system to cope with the crisis. In spite of a growing literature that demonstrates the importance of performance perceptions for the formation of welfare state attitudes (Chung & Meuleman, Citation2017; Habibov et al., Citation2019a; Haugsgjerd & Kumlin, Citation2020; Roosma et al., Citation2014, Citation2016), it is an open question whether perceived underperformance of the welfare state leads to increase in support for additional investments or a decrease in support. If citizens perceive a strong underperformance of the welfare state in a particular area (and if they remain generally supportive of the welfare state), they might support a strong increase in spending on the underperforming area in order to fix the (perceived) problem (see, e.g., Habibov et al. (Citation2019a) for the case of education). This is called an ‘improvement reaction’ in the words of Chung and Meuleman (Citation2017, p. 58). To the opposite, a ‘punishment reaction’ (ibid.: 58) amounts to a combination of low performance perceptions with a low willingness to increase public spending on a particular social policy area, which might be related to citizens opting out of public in favor of private social policy schemes (Busemeyer & Iversen, Citation2020).

Previous research on health care attitudes in Germany (Wendt et al., Citation2014) suggests that an ‘improvement reaction’ is more likely in the case of Germany than the former. Wendt et al. (Citation2014) find that although a majority of the German resident population perceive a need for significant reforms and improvements in the health care systems, only 11 percent support less spending on health care (ibid.: 338, 340). The study also finds a significant willingness of citizens to pay higher taxes for additional spending or increase private co-payments. Building on these insights, my theoretical expectation for the empirical analysis below is therefore that an ‘improvement reaction’ is more likely than a ‘punishment reaction’ in the case of Germany, i.e., more negative performance perceptions should be associated with a higher level of support for additional spending on health care (and vice versa) (Hypothesis 2a). Given the exceptional situation, a ‘punishment reaction’ might still be possible, however, in which negative performance perceptions would be associated with lower spending support (Hypothesis 2b).

In order to measure performance perceptions (more details on this below), I focus on different aspects of system performance with regard to the crisis response. A first issue in this regard is simply the (perceived) efficiency of how well the system has responded to the crisis. The second issue relates to the fairness of the crisis response, i.e., are certain parts of the population treated differently from others? This aspect might be particularly important in the German case as the health care system retains a ‘dualist’ institutional structure with richer citizens (as well as civil servants) being allowed to opt out of the public health care insurance scheme in favor of private insurance (Gerlinger & Rosenbrock, Citation2018). Finally, the third issue captures perceptions of how the system was prepared to face the Covid-19 pandemic – a more general and broader of system performance compared to the other two.

Political trust and spending support

Finally, the empirical analysis will also probe whether general political trust is associated with support for additional spending on health care as some papers in the literature have suggested (Habibov et al., Citation2018a; Habibov et al., Citation2018b). The mechanism behind the association between general political trust and support for the welfare state includes, but also goes beyond performance perceptions of particular social policies. In particular, if citizens have developed general political trust in ‘trustworthy, impartial, and uncorrupted government institutions’ (Rothstein et al., Citation2012, p. 1), they are more likely to accept the state taxing away a significant share of their income to invest in the provision of welfare state services and benefits. In the long term, however, declining political trust can also impose significant limits on citizens’ willingness to contribute to the provision and financing of public goods (Haugsgjerd & Kumlin, Citation2020). In short, I expect a positive association between general political trust and support for additional health care spending (Hypothesis 3).

Besides performance perceptions and political trust, attitudes towards health care spending are likely to be associated and influenced by other determinants as well. For instance, left-wing ideology should be positively associated with spending support. Indicators of self-interest, in particular the personal health status, should also be positively associated with support for spending since the perceived risky consequences of an underinvestment in health care should be more obvious and visible in this case. Likewise, being older should also increase support for spending. In contrast, I do not expect a strong association between spending support and income (and, by extension, educational background), following Jensen’s (Citation2011, Citation2012) insight that in the case of health care, the income-related conflict about social spending should be more muted as the risk of getting sick is related to the life-cycle rather than the individual’s socio-economic position. Finally, I control for gender and whether the respondent knows someone infected with the Corona virus (which, again, could increase spending support because the risk is more visible).

Empirical analysis

Data and methods

The survey data used in this paper was collected in three waves (the first one in April/May 2020, the second in November 2020 and the third one in May 2021) as part of a larger survey project on the implications of the pandemic for political outcomes.Footnote1 The data was collected online by a professional survey company (Kantar) via quota sampling from a large-scale online panel of the German resident population. In total, 7,431 individuals participated in the survey (2,701 in the first wave, 2,482 in the second and 2,248 in the third). The maximum number of observations is reduced in the analysis because of missing data for different variables.

The specific measure used to tap into individual-level support for health care spending (explained in detailed below) involves experimental components. The random assignment of respondents to the different treatments (four in total) was done separately for each wave, which implies that respondents can (and often are) assigned to different treatment groups across waves. Hence, for the purpose of this paper, it is not possible to study the development of spending support ‘within individuals’ as it changes over time. Instead, the analysis pools all observations, while of course controlling for individual-level characteristics (via clustered standard errors) and the overall time trend (by means of dummy variables for the second and third waves). Additional analyses of possible interaction effects between the wave dummy and the other independent variables do not reveal any strong systematic patterns.

I now introduce the measure for spending support for health care. I follow recent research that has paid more attention to potential trade-offs associated with an increase in spending (Busemeyer & Garritzmann, Citation2017; Häusermann et al., Citation2019) in order to provide more robust measures of spending support. Largely following the approach pursued by Busemeyer and Garritzmann (Citation2017) when measuring support for education spending, individual respondents were randomly assigned to four different ‘treatment’ groups. The first group received the following question: ‘Should the government invest more, the same or less as now in health care after the Corona crisis is over?’ Respondents could reply on a 5-point scale from ‘spend much more compared to before the crisis’ via ‘spend more’, ‘spend the same’, ‘spend less’ to ‘spend much less compared to before the crisis’. Respondents in the other groups were given slight modifications of this question by adding a range of different fiscal trade-offs and constraints: first, ‘ … even if it means higher taxes to pay for this’; second, ‘ … even if other areas of social spending such as pensions have to be cut back’; and third, ‘ … even if it means higher levels of public debt’. Assessing citizens’ spending preferences across these different scenarios provides a more robust estimate of their genuine willingness to increase spending and accept the necessary trade-offs than simply asking a straightforward question about this issue as previous surveys have done.

Performance perceptions are operationalized thus: Perceptions regarding the overall efficiency of the crisis response are measured as responses to the following question: ‘If you think of how the German health care system is coping with the Corona crisis, how efficient would you rate the crisis response?’ Perceptions of system fairness are captured by this question: ‘Do you think that doctors and nurses are giving privileged treatment to certain population groups or do you think that everybody is treated the same?’ Responses to both questions are given on an 11-point scale, for which high values indicate more positive (more efficient, fairer) performance perceptions. Perceptions on the previous preparedness of the system (‘How well prepared was the German health care system for the Corona crisis?’) are measured on a 5-point scale from ‘very well’ to ‘very badly’, i.e., higher values indicate more negative performance perceptions. For the analysis, the scale is reversed (to make it comparable to the other performance measures) and dichotomized (1=(very) well prepared; 0=partly or (very) badly prepared) to ease interpretation. The measure of political trust is constructed from a factor analysis of a series of items probing respondent’s level of trust in a range of political institutions and actors (the federal government, the federal parliament (Bundestag), the state government and political parties; Cronbach’s alpha=0.93).

The remaining control variables are operationalized in a straightforward manner: gender (1=female), household net income in six categories derived from the distribution of incomes in Germany (less than 900 Euros, 900-1.500 Euros, 1.500-2.600 Euros, 2.600-4.000 Euros, 4.000-6.000 Euros, more than 6.000 Euros), educational background in three categories low = basic school leaving certificate (Hauptschulabschluss) or less, middle = middling school leaving certificate (Realschulabschluss), high (academic school leaving certificate (Abitur)), and age (operationalized in three categories: 18–39 years, 40–59 years, more than 60 years old). Individual ideology is measured as self-placement on the common scale from ‘left’ (0) to ‘right’ (10), i.e., higher values indicate support for a more right-wing ideology. Personal health status is a self-reported assessment on a 5-point scale (from ‘I am doing very well health-wise’ to ‘I have a serious illness’ with intermediate categories in between). A dummy variable captures whether the respondent knowns someone with a Corona infection in her circle of family, friends and work-related connections.

Regarding methods, I transform the original 5-point Likert scales for the spending measures and the preparedness performance measure into a binary variable and recode the fairness and efficiency perceptions into a summary variable with three categories to ease interpretation. As the dependent variable is binary, I use straightforward logit models with standard errors clustered on individuals.

Descriptive statistics

Before I present the results from the multivariate analysis, I would like to start with some descriptive statistics on the development of spending support across the three survey waves responding to the first hypothesis mentioned above. Table A1 in the online appendix displays the shares of respondents supporting more or much more additional spending on health care in the different groups across the three waves. Here, it is important to emphasize a central limitation of this study: As the first wave of the survey took place after the onset of the first Corona wave earlier in March of 2020, the survey itself does not contain information on pre-crisis levels of spending support. The last reliable pre-crisis estimate of spending support for health care stems from the 2016 wave of the ISSP ‘Role of Government’ survey. Using a very similar question wording as I do, this survey identifies a share of 75.3 percent supporting more or much more spending on health care. Our initial estimate is slightly above that level (80.22 percent), but still roughly in the same region (similar data is given in the earlier study by Wendt et al. (Citation2014)). Given data limitations, it is impossible, however, to verify whether this small increase in support is already due to the onset of the crisis, generally changing support over time or simply measurement error.

Regarding the development of spending support throughout the different phases of the Covid-19 pandemic itself, spending support tends to be very stable between the first and the second waves, but ticks upward in the third wave. Notably, it is in particular in the trade-off scenarios (cutting back other spending or increasing public debt) that spending support increases. This might already be indicating an ‘improvement’ rather than a ‘punishment’ reaction and is tentative support for Hypothesis 1a.

Comparing simple means of spending support across the different treatment groups as defined above shows that the high support for additional spending in the first group, when no fiscal constraints are mentioned, is significantly reduced once respondents are confronted with a range of fiscal trade-offs and constraints. Summing up across waves, 80.83 percent would support more or much spending on health care if there are no constraints. When faced with the requirement to increase taxes, only 67.63 percent of respondents are still in favor of additional health care spending. 76.68 percent would still support spending increases if these were financed by increasing levels of public debt. Spending cutbacks are the least popular: In this case, only 55.77 percent are still in favor of more government spending in health care. This pattern is very similar in the case of education spending (Busemeyer & Garritzmann, Citation2017), but there are important differences: In the case of education spending, support for additional spending in exchange for cutbacks is much lower than in the case of health care (about half). The other fiscal constraints (increasing taxes or public debt) also have a more negative impact in the case of education compared to health care spending. Whether this is indeed related to spending pressures in the context of the Corona pandemic or an inherent difference between education and health care cannot be answered here, since the available surveys only include the one or the other, but it would be an interesting question to pursue in future research (with new survey data).

When it comes to the main independent variables of interest, i.e., performance perceptions and political trust, descriptive statistics for the aggregate level also indicate more stability than change, although there is a significant drop in some of these measures between the second and the third wave. This is likely related to the development of the pandemic over the winter months of 2020/21. Shortly after the second survey wave was done, the second and later the third Corona wave hit Germany (like many other countries) with full force. Public accounts of the crisis response have turned more critical over the winter and spring, talking of policy breakdown and ‘Corona chaos’Footnote2 related to the slow start of the vaccination campaign, confusing and changing regulations regarding lockdown measures, the delayed payout of economic aid and several scandals involving members of the federal parliament acting as paid brokers in the sale of protective gear (masks) to federal and state ministries.

In concrete numbers, the performance perceptions of the German resident population changed significantly across the three survey waves. In April/May, 52 percent of respondents held a positive view (scoring 7–10 on the 11-point scale) regarding the efficiency of the crisis response, which increased to 57 percent in November, but then dropped significantly to a mere 29 percent. Perceptions were somewhat more positive regarding the fairness of the crisis response. In April/May 2020, 59 percent held a positive view on this issue, slightly decreasing to 58 percent in November and to 53 percent in May 2021. In contrast, only a relative minority of about 35 percent stated that the system was well (or very well) prepared to handle the crisis. Positive preparedness perceptions declined somewhat to 34 percent in November, and again dropped precipitously to 12 percent in May 2021. Hence, the German resident population is much more skeptical regarding the previous preparedness of the system compared with the efficiency and fairness of the crisis response (so far). Regarding general political trust, the patterns look similar, but the drop is less pronounced (from around 4.1 in the first and second survey waves to 3.7 in the third survey wave). This is not as significant a decline as in the case of performance perceptions, but it could indicate that low performance perceptions may contribute to an erosion of general political trust in the long run as argued by Haugsgjerd and Kumlin (Citation2020).

Multivariate analysis

As a first step in the analysis, includes regression models using the pooled sample with all observations () and different combinations of control variables; further below I run separate models for the different treatment conditions. In , a categorical variable is included to indicate to which treatment condition particular respondents were exposed to (the first group for which there was no spending constraint mentioned is the reference category).

Table 1. Determinants of individual-level support for additional health care spending, pooled model.

The most important finding that emerges from the analysis is that preparedness perceptions are negatively associated with support for additional spending on health care, i.e., individuals who regarded the system as well (badly) prepared are more likely to oppose (support) additional spending. This is a clear indication of an ‘improvement reaction’ in the sense of Chung and Meuleman (Citation2017) and therefore strong support for Hypothesis 2a. Relatedly, the analysis reveals a positive association between general political trust and support for additional health care spending, supporting H3 from above. However, in this case, the association is less robust compared to the one between preparedness perceptions and spending support. Other dimensions of performance perceptions (efficiency and fairness perceptions) are not strongly related to spending support with the partial exception of fairness perceptions, indicating that individuals who regard the crisis reaction of the health care system as fair and balanced tend to be more supportive of additional spending on health care.

Model 4 in includes an interaction term between general political trust and preparedness perceptions. It might be possible that the ‘improvement reaction’ among individuals with negative performance perceptions is stronger when these individuals express a high level of general trust in political institutions and actors. The model, however, shows that this expectation is not borne out in the data since the interaction term is insignificant and does not affect the coefficient estimates of the other two variables.

The magnitude of the effect of preparedness perceptions on spending support is about twice the size as the effect associated with general political trust. To derive these estimates, I use the model with the unconstrained question for the simulation as well as the more fine-grained (5-point scale) operationalization of preparedness perceptions to be able to derive similar effect size estimates. The predicted change in the probability of supporting more or much more spending on health care when simulating an increase in preparedness perceptions of about one standard deviation is a reduction in support of about 7 percentage points. In contrast, the predicted increase in spending support associated with an increase of general political trust by one standard deviation amounts to 3.3 percentage points.

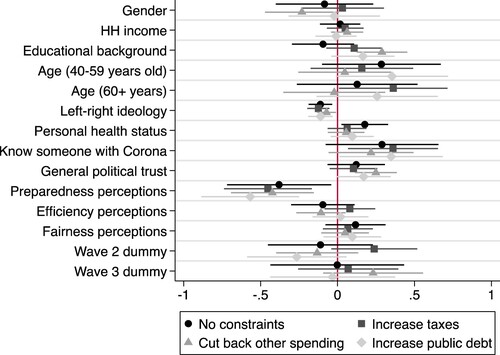

In the next step and to probe the robustness of my findings, I re-run the analyses for the different sub-groups. plots the coefficient estimates of four regression models (one for each treatment group); the full regression models can be found in Table A2 in the Appendix. I include the different dimensions of performance perceptions (general political trust, efficiency, fairness and preparedness perceptions) in the same model. Additional analyses (Table A3 in the appendix) confirm that the selective inclusion or exclusion of these variables does not change the findings. Most importantly, the ‘improvement reaction’ identified above holds across the different treatment conditions, whereas the positive association between general political trust and spending support holds only in a sub-set of models and is particularly strong in the condition that involves cutbacks in other spending areas. This is in line with previous research that argues that general political trust is particularly important in situations when policy decisions involve significant fiscal or ideological costs (Gabriel & Trüdinger, Citation2011; Rudolph & Evans, Citation2005).

Regarding the other determinants of spending support, the non-association between income and spending support was to be expected given the findings in the pertinent literature. Equally expected is the positive association between personal health status (i.e., being more ill) and support for additional spending. What is more surprising is the clear positive association between educational background and spending support, which also holds when fiscal constraints are introduced. This may be related to the fact that highly educated individuals are more likely to value the importance of additional investments in the health care infrastructure, adopting a more long-term oriented perspective rather than giving in to short-term urges to ramp up spending on other, more directly compensating forms of social spending. As was expected above, I find a positive association between left-wing ideology and support for additional spending, which is also robust across all the different sub-groups. Furthermore, being in bad health as well as knowing someone with a Corona infection increases support for additional spending on health care, but these effects are not very strong and robust across the sub-groups. Similarly, neither age, nor gender are strongly related to spending support.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper has provided an analysis of public support for additional spending on health care during the Covid-19 pandemic in the case of Germany. Different from what could have been expected, my analysis indicates stability of attitudes rather than radical changes, although support for additional spending seems to be increasing slightly in the most recent phase of the pandemic. This chimes well with a similar finding by Laenen and van Oorschot (Citation2020) reviewing the impact of the economic and financial crisis of 2008/09 on Europeans’ welfare attitudes. Furthermore, my findings show that performance perceptions and political trust matter with regard to support for health care spending, the former more than the latter. Individual perceptions regarding the preparedness of the German health care system to deal with the Corona crisis are strongly associated with spending support in the pattern of a typical ‘improvement reaction’ as individuals who rate the preparedness of the system as particularly low express strong support for additional spending. Spending support is reinforced by higher levels of general political trust, i.e., when individuals are convinced that additional spending on health care will be used effectively to improve the performance of the system. My data also revealed a significant drop in performance perceptions during the last phase of the pandemic (i.e., between the fall of 2020 and early summer of 2021), which might spill over to trigger an erosion of general political trust in the shape of a ‘downbound spiral’ of decreasing performance perceptions, mounting political distrust and a limited willingness to support additional spending on health care. Given the improvement of the Corona situation during the summer months of 2021, it is too early to tell whether this might happen, but it remains a possibility.

Regarding the contribution of the paper to the literature discussed at the beginning of this paper, my analysis confirms the strong feedback effects between performance perceptions, political trust and support for the welfare state identified in this work. It seems that this feedback cycle works even under the extreme conditions of a historic crisis, although it may be exactly in these kinds of crisis situations that political trust matters most (de Blok et al., Citation2020). Related to this issue, a significant limitation of this study is that it does not allow for a direct comparison of attitudinal patterns before, during and after the crisis, since the first wave of the survey took place after the onset of the pandemic. Still, even though this may delimit the generalizability of my findings to some extent, I believe the analysis of spending attitudes and their relationship to perceptions of the performance of the health care system in dealing with the crisis and how they evolve throughout the different phases of the crisis holds value.

Finally, what are the implications of this study for policy-making more broadly? For one, my analysis shows that even though increasing public spending on health care is hugely popular among citizens, confronting individuals with fiscal constraints that might go along with spending increases can significantly reduce public support for additional spending, providing in a sense a preview of which policy trajectories are more or less feasible to implement. For instance, the analysis clearly confirms previous research that citizens very much dislike direct trade-offs, when spending increases would have to be compensated by cutbacks in other parts of the welfare state. To the contrary, the analysis also indicates a certain willingness of citizens to pay for additional spending via higher taxes or higher levels of public debt. Thus, the dynamic of public opinion for the post-pandemic phase rather points towards a further expansion of the welfare state rather than retrenchment.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.2 KB)Acknowledgements

I thank Claudia Diehl, Julian Garritzmann, Carsten Jensen, Staffan Kumlin, and Elias Naumann as well as the anonymous reviewers of this journal for extremely helpful comments and suggestions. I would also like to thank Philipp Kling, Konstantin Mozer and Thomas Wöhler for their support in administering the survey. Funding was generously provided by the Excellence Cluster ‘The Politics of Inequality’, DFG Grant EXC 2035/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marius R. Busemeyer

Marius R. Busemeyer is Professor of Political Science and Speaker of the Excellence Cluster ‘The Politics of Inequality’ at the University of Konstanz. He is also a Senior Research Fellow at the WSI, Düsseldorf.

Notes

1 Further details and documentation can be found here: https://www.exc.uni-konstanz.de/en/inequality/research/covid-19-and-inequality-surveys-program/ (accessed August 30, 2021).

2 See, for instance, this commentary in the SPIEGEL: https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/corona-chaos-in-deutschland-multiples-staatsversagen-kommentar-a-2647f186-883e-4823-8cc4-9a0b3de38af9 (accessed March 30, 2021).

References

- Ares, M., Bürgisser, R., & Häusermann, S. (2021). Attitudinal polarization towards the redistributive role of the state in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 31(sup1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924736

- Baute, S., & de Ruijter, A. (2021). EU health solidarity in times of crisis: Explaining public preferences towards EU risk pooling for medicines. Journal of European Public Policy Online, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1936129

- Breznau, N. (2021). The welfare state and risk perceptions: The novel Coronavirus pandemic and public concern in 70 countries. European Societies, 23(sup1: European Societies in the Time of the Coronavirus Crisis), S33–S46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1793215

- Busemeyer, M. R., & Garritzmann, J. (2017). Public opinion on Policy and budgetary trade-offs in European welfare states: Evidence from a New Comparative survey. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(6), 871–889. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1298658

- Busemeyer, M. R., & Iversen, T. (2020). The welfare state with private alternatives: The transformation of popular support for social insurance. Journal of Politics, 82(2), 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1086/706980

- Cammett, M., Lynch, J., & Bilev, G. (2016). The influence of private health care Financing on citizen trust in government. Perspectives on Politics, 13(4), 938–957. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592715002248

- Chung, H., & Meuleman, B. (2017). European parents’ attitudes towards public childcare provision: The role of current provisions, interests and ideologies. European Societies, 19(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2016.1235218

- de Blok, L., Haugsgjerd, A., & Kumlin, S. (2020). Increasingly connected? Political distrust and dissatisfaction with public services in Europe, 2008-2016. In T. Laenen, B. Meuleman, & W. van Oorschot (Eds.), Welfare State Legitimacy in Times of Crisis and Austerity: Between Continuity and Change (pp. 201–221). Edward Elgar.

- Edlund, J. (2006). Trust in the capability of the welfare state and general welfare state support: Sweden 1997-2002. Acta Sociologica, 49(4), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699306071681

- Gabriel, O. W., & Trüdinger, E.-M. (2011). Embellishing welfare State Reforms? Political trust and the support for welfare State Reforms in Germany. German Politics, 20(2), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2011.582098

- Gerlinger, T., & Rosenbrock, R. (2018). Gesundheitspolitik. In P. Kriwy & M. Jungbauer-Gans (Eds.), Handbuch Gesundheitssoziologie (pp. 1–26). SpringerVS.

- Habibov, N., Auchynnikava, A., & Luo, R. (2019a). ‘How does the quality of public education influence the citizens’ willingness to support it? Evidence from a comparative survey of 27 countries’. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 22(2), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-04-2019-0029

- Habibov, N., Auchynnikava, A., Luo, R., & Fan, L. (2018a). Who wants to pay more taxes to improve public health care? International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 33(4), e944–ee59. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2572

- Habibov, N., Cheung, A., & Auchynnikava, A. (2018b). Does institutional trust increas willingness to Pay More Taxes to support the welfare state? Sociological Spectrum, 38(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2017.1409146

- Habibov, N., Luo, R., & Auchynnikava, A. (2019b). The effects of Healthcare quality on the willingness to Pay More Taxes to improve public Healthcare: Testing Two alternative hypotheses from the research literature. Annals of Global Health, 85(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2411

- Haugsgjerd, A., & Kumlin, S. (2020). Downbound spiral? Economic grievances, perceived social protection and political distrust. West European Politics, 43(4), 969–990. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1596733

- Häusermann, S., Kurer, T., & Traber, D. (2019). The Politics of trade-offs: Studying the dynamics of welfare state reform With conjoint experiments. Comparative Political Studies, 52(7), 1059-1095. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018797943

- Hetherington, M. J. (2005). Why Trust Matters: Declining Political Trust and the Demise of American Liberalism. Princeton University Press.

- Jensen, C. (2011). Marketization via compensation: Health care and the Politics of the right in advanced industrialized nations. British Journal of Political Science, 41(4), 907–926. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123411000159

- Jensen, C. (2012). Labour market- versus life course-related social policies: Understanding cross-programme differences. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(2), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.599991

- Jensen, C., & Naumann, E. (2016). Increasing pressures and support for public healthcare in Europe. Health Policy, 120(2016), 698–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.015

- Jensen, C., & Petersen, M. B. (2017). The deservingness heuristic and the Politics of health care. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12251

- Kumlin, S. (2013). Dissatisfied democrats, policy feedback and European welfare states, 1976-2001. In S. Zmerli & M. Hooghe (Eds.), Political Trust: Why Context Matters (pp. 163–185). ECPR Press.

- Kumlin, S., Stadelmann-Steffen, I., & Haugsgjerd, A. (2017). Trust and the welfare state. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust (pp. 386–408). Oxford University Press.

- Laenen, T., & van Oorschot, W. (2020). Change or Continuity in Europeans’ welfare attitudes? In T. Laenen, B. Meuleman, & W. van Oorschot (Eds.), Welfare State Legitimacy in Times of Crisis and Austerity: Between Continuity and Change (pp. 249–266). Edward Elgar.

- Lynch, J., & Gollust, S. E. (2010). Playing fair: Fairness beliefs and Health Policy preferences in the United States. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 35(6), 849–887. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2010-032

- Missinne, S., Meuleman, B., & Bracke, P. (2013). The popular legitimacy of European healthcare systems: A multilevel analysis of 24 countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 23(3), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928713480065

- Naumann, E. (2014). Increasing conflict in times of retrenchment? Attitudes towards healthcare provision in Europe between 1996 and 2002. International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(3), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12067

- Reeskens, T., Muis, Q., Sieben, I., Vandecasteele, L., Luijkx, R., & Halman, L. (2021). Stability or change of public opinion and values during the coronavirus crisis? Exploring Dutch longitudinal panel data. European Societies, 23(sup1: European Societies in the Time of the Coronavirus Crisis), S153–SS71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1821075

- Roosma, F., Van Oorschot, W., & Gelissen, J. (2014). The preferred role and perceived performance of the welfare state: European welfare attitudes from a multidimensional perspective. Social Science Research, 44, 200–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.12.005

- Roosma, F., Van Oorschot, W., & Gelissen, J. (2016). ‘The achilles’ heel of welfare state legitimacy: Perceptions of overuse and underuse of social benefits in Europe’. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(2), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1031157

- Rothstein, B., Sammani, M., & Teorell, J. (2012). Explaining the welfare state: Power resources vs. The quality of government. European Political Science Review, 4(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773911000051

- Rudolph, T. J., & Evans, J. (2005). Political trust, ideology, and public support for government spending. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 660–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00148.x

- Svallfors, S. (2002). Political trust and support for the welfare state: Unpacking a supposed relationship. In B. Rothstein & S. Steinmo (Eds.), Restructuring the Welfare State: Political Institutions and Policy Change (pp. 184–205). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Taylor-Gooby, P. (2002). The silver Age of the welfare state: Perspectives on resilience. Journal of Social Policy, 31(4), 597–621. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279402006785

- Toikko, T., & Rantanen, T. (2017). How does the welfare state model influence social political attitudes? An analysis of citizens’ concrete and abstract attitudes toward poverty. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 33(3), 201–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/21699763.2017.1302892

- Van Oorschot, W. (2006). Making the difference in Europe: Deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928706059829

- Van Oorschot, W., & Meuleman, B. (2012). Welfare performance and welfare support. In S. Svallfors (Ed.), Contested Welfare States: Welfare Attitudes in Europe and Beyond (pp. 25–57). Stanford University Press.

- Wendt, C., Kohl, J., Mischke, M., & Pfeifer, M. (2010). How Do Europeans perceive their Healthcare system? Patterns of satisfaction and preference for state involvement in the field of Healthcare. European Sociological Review, 26(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp014

- Wendt, C., Mischke, M., & Pfeifer, M. (2011). Welfare States and Public Opinion: Perceptions of Healthcare Systems, Family Policy and Benefits for the Unemployed and Poor in Europe. Edward Elgar.

- Wendt, C., Naumann, E., & Klitzke, J. (2014). Reformbedarf im deutschen gesundheitssystem aus sicht der bevölkerung. Zeitschrift für Sozialreform, 60(4), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1515/zsr-2014-0404