ABSTRACT

Public attitudes towards the free movement of workers in the European Union vary substantially between countries and individuals. This paper adds to the small but growing research literature on this issue by analysing the role of national welfare institutions. We investigate the relationship between the degree of ‘institutional reciprocity’ in national systems of social protection and attitudes to EU labour immigration across 12 European countries. We do not find evidence of an effect of institutional reciprocity on opposition to EU labour immigration among the public at large. However, institutional reciprocity appears to matter for economically vulnerable groups. We identify an interaction effect indicating that higher degrees of institutional reciprocity in national social protection systems, and in unemployment insurance systems specifically, are associated with lower levels of opposition to EU labour immigration among unemployed people. Hence, reciprocity in welfare state institutions appears to shield free movement from opposition, at least among vulnerable groups.

The free movement of workers has in recent years become a highly contested issue in the European Union (EU), generating political debates and conflicts both between and within EU Member States. Under the current rules for free movement, EU citizens can move and take up employment in any other EU country and – as long as they are ‘workers’ – enjoy full and equal access to the host country’s welfare state.

The political leaders of a number of EU Member States that are net-receivers of EU workers have recently called for changes to the rules surrounding the free movement of workers. The United Kingdom, where free movement played a major role in the referendum vote to leave the EU, has been the only EU country to propose restricting the free movement of workers as such (Cameron, Citation2013). However, leaders of a few other EU Member States (including in Denmark, the Netherlands, and Austria – see Ruhs & Palme, Citation2018) have called for more restricted access for EU workers to national welfare states. The political leaders of many other EU countries appear to have been opposed to fundamental reform of the current rules, directly or indirectly supporting the view that the current policy of unrestricted access to labour markets and full access to welfare states for EU workers should continue.

Views about free movement have not only varied between political leaders but also among the public across and within different EU Member States (Blinder & Markaki, Citation2018). In politics, being a net-receiver of EU labour migrants appears to be a necessary condition for opposition to free movement among European countries. Research has also shown that ordinary Europeans tend to be more positive to outward mobility than to inward mobility (Lutz, Citation2020). However, opposition to free movement differs considerably even among EU Member States that are net-receivers of EU-workers (Mårtensson & Uba, Citation2018). Understanding these variations and drivers of public attitudes matters for the political legitimacy and sustainability of the current rules for the free movement of workers in the EU. While public policies do not always reflect public attitudes, research has shown that highly salient policies in Europe are responsive to what the public think (Rasmussen et al., Citation2019), and this also applies to migration policies (Böhmelt, Citation2019).

How can we explain variations in public opposition to free movement across and within European countries that are characterised by net-inflows of EU workers? In this paper, we reason that national welfare state institutions, as well as their interaction with individual-level socio-economic factors, can be vital in accounting for these differences. Existing research on attitudes to European integration suggests that both economic factors and identity will shape attitudes to free movement (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009). European integration and globalisation have sparked substantial divisions in public opinion within European countries, between groups that have come out as ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of these processes (Kriesi et al., Citation2008). For example, Hobolt (Citation2016) finds that the divide between winners and losers of globalisation was a key determinant of the Brexit vote in the UK. However, the large research literature on the determinants of attitudes to immigration (in general) has shown that attitudes are affected not only by individual factors but also by prevailing institutions, including welfare systems (e.g., Facchini & Mayda, Citation2009). Furthermore, studies of the role of welfare institutions in shaping attitudes to immigration have found that they often matter in interaction with labour markets and other individual characteristics (Hanson et al., Citation2007; Huber & Oberdabering, Citation2016; Nagayoshi & Hjerm, Citation2015). Free movement – which combines unrestricted access to labour markets and welfare states for EU workers – is an area where interactions between welfare institutions and socio-economic characteristics, especially socio-economic vulnerability, are likely to be particularly important.

The emerging literature on attitudes to free movement has not yet investigated the role of institutional factors and how they interact with individuals’ socio-economic vulnerability, in explaining variations in people’s views of intra-EU labour migration. Our paper is an attempt to fill this gap: we focus on 12 European countries that are net-receivers of EU workers, and we choose to analyse public opposition to inward free movement specifically, i.e., attitudes to what we term ‘EU labour immigration’.

The aim of our paper is to examine how public opposition to EU labour immigration is related to the degree of reciprocity embedded in national welfare institutions. We define reciprocity in terms of the degree to which (1) the social insurance system is financed by individual contributions and (2) benefits are earnings-related. We expect that greater reciprocity can lower opposition to EU labour immigration (and hence to free movement) among the host country population, for three reasons: first, EU workers will be perceived as more ‘deserving’ welfare recipients if benefits have to be ‘earned’ and are not just ‘received’; second, social protection programmes with high degrees of institutional reciprocity will be perceived as more self-funded with lower fiscal costs from immigration for the taxpayers; and third, vulnerable groups are generally better protected from economic risks such as unemployment in more reciprocal systems, and thus less threatened by labour migration (cf. Nelson, Citation2003). Considering the role of socioeconomic factors in shaping attitudes to European integration at the individual level, and the interactions between welfare institutions and individual characteristics identified in existing research on attitudes to immigration, we expect these institutional effects to be particularly relevant for economically vulnerable groups, such as the unemployed.

Theory and previous research

There are few publications that have provided a systematic analysis of the determinants of attitudes to free movement in the EU (Blinder & Markaki, Citation2019b; Larsen, Citation2020; Lutz, Citation2020; Meltzer et al., Citation2020; Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2018), and none of them have analysed the role of welfare institutions. The broader research literature on links between welfare states and attitudes to immigration and access to social rights for migrants (e.g., Sainsbury, Citation2012) is also relatively limited. A much larger body of research has explored the role of other explanatory factors such as labour market competition, i.e., the perceived consequences and ‘threats’ of immigration to the wages and employment of citizens, and sociotropic concerns, especially about identity and cultural impacts of migrants on the country as a whole (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Citation2014).

Insights and gaps in existing research

The empirical focus of our study, on the link between institutional reciprocity and attitudes to EU labour immigration in European countries that are net-receivers of EU workers, is informed by three observations about existing research: First, attitudes to free movement very much depend on whether they are viewed primarily through an immigration or emigration lens. This is illustrated by Vasilopoulou and Talving’s (Citation2018) finding that citizens in poorer EU Member States are more likely to support free movement than citizens in richer Member States. Lutz (Citation2020) highlights the double-sided nature of attitudes to free movement; people can value their own rights to outward mobility without necessarily supporting the inward mobility of citizens of other EU countries. This means there are likely to be different explanatory models for attitudes to free movement in net-sending and net-receiving countries, and for attitudes to inflows and outflows of EU workers.

Second, largely due to scarcity of relevant data, most existing research on the links between welfare institutions and attitudes to immigration and social rights for migrants has focused on analysing the role of ‘welfare regimes’ rather than specific institutional features of welfare states, such as reciprocity. For example, Van Der Waal et al. (Citation2013) analyse how welfare chauvinism varies across different welfare regimes. Their results provide empirical support for the relevance of welfare regimes to such attitudes, although they fully attributed the regime effects to regime differences in income inequality. The analysis in Nagayoshi and Hjerm (Citation2015) is a notable exception to the predominant regime approach. They reason that different types of labour market policies can affect attitudes to immigration. Nagayoshi and Hjerm’s argument is related to our study as they argue that active labour market policies imply that welfare recipients meet reciprocity criteria that the public expects, which positively affects their perceived deservingness and in turn also alleviates anti-immigration attitudes.

Third, our paper has been partly inspired by research on welfare attitudes and public preferences for restricting social rights for migrants. Reeskens and Van Oorschot (Citation2012) find that most Europeans prefer conditional access to welfare benefits for migrants, and that the most commonly preferred principle for regulating migrants’ access to social rights is ‘reciprocity’ (defined by them in a narrow way as ‘prior contribution’). Moreover, people who believe that welfare benefits should be provided based on the principle of ‘need’ (rather than ‘equality’ or ‘reciprocity’) are significantly more likely to support restrictions of the welfare benefits of migrants. Our analysis differs from that in Reeskens and Van Oorschot (Citation2012) both by focusing on the role of institutions in shaping attitudes to labour immigration, and by focusing on free movement as a specific form of labour migration.

Theorising the relationship between reciprocity in social insurance programmes and attitudes to EU labour immigration

Our analysis focuses on a particular aspect of national welfare states, namely, the degree of reciprocity built into social insurance programmes – a feature that, we argue, may be of crucial importance for attitudes to EU labour immigration. In our definition and understanding of the concept, both the financing and design of benefits affect the reciprocity of a social protection system. This means that we do not only consider the ‘contributiveness’ of the welfare system (i.e., the extent to which the receipt of benefits requires a prior contribution by the insured person) as most previous research has done but we also take account of the ‘earnings-relatedness’ of the benefits received (i.e., the extent to which benefits replace previous earnings). The link between the two sides of reciprocity is not necessarily very strong. For example, the Beveridge system introduced in the United Kingdom after World War II was built on contributory financing where the insured person made a substantial contribution to the system. However, benefits were flat rate and thus not regulated by the size of the contributions. At the same time, reciprocity in a social protection system can also be fostered by relying on strong ‘earnings-relatedness’, so that those who have earned more (and paid more contributions) also receive higher benefits. This is why we consider ‘contributiveness’ and ‘earnings-relatedness’ as at least partly separate aspects of the same underlying reciprocity factor.

‘Reciprocity’ is different, in terms of its definition and expected effects on attitudes to immigration, from other commonly used concepts such as ‘decommodification’ (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990) and ‘generosity’ (Scruggs, Citation2006). These other concepts have different theoretical foundations (decommodification) or reflect all aspects of system generosity in a ‘more is more’ way (generosity). In contrast, our definition of reciprocity captures ‘earnings-relatedness’ and ‘contributiveness’ because these specific system characteristics are directly connected to the reciprocity dimension of the social protection system.

Given this understanding, we argue that institutional reciprocity can affect attitudes and policy preferences vis-à-vis EU labour immigration in two different ways, one relating to ideas about deservingness and the other relating to perceptions of material effects. First, institutional reciprocity can play an important role in shaping people’s perceptions about the deservingness of EU migrants to receive welfare benefits and social solidarity in the host country, and about the fairness in how new migrants access the welfare state. We know from existing data and research that the preferred principles for redistribution among existing residents vary across EU countries, and that these preferences are linked to, and reflected in, the actual characteristics of national welfare systems (Mårtensson, Palme, & Ruhs, Citation2019). However, when it comes to regulating access to social protection for new migrants, there is a popular and widespread view among the populations of most net immigration EU member states that ‘reciprocity’ should be the guiding principle (see Appendix Table A1). This suggests that in these countries, entitlements based on reciprocity or ‘merit’ are seen as more legitimate for new migrants than benefits given on the basis of ‘need’ or ‘universal rights’ based on citizenship (Reeskens & Van Oorschot, Citation2012). In consequence, we argue that a high degree of reciprocity in social protection systems can help create and maintain public support for EU labour immigration, and eventually for free movement, because it regulates EU workers’ access to national welfare systems in a way that corresponds to the perception of the receiving country’s population that EU workers have to ‘earn’ their benefits.

A second way in which the degree of institutional reciprocity may affect attitudes to EU labour immigration in receiving countries is by shaping perceptions of the material effects of in-ward labour mobility for the population of the host country. While non-reciprocal national welfare institutions do not necessarily generate negative fiscal effects of free movement (Österman et al., Citation2018), public perceptions may differ from ‘real’ effects (Blinder & Markaki, Citation2019a). It is possible and, we argue, likely that social insurance programmes with high degrees of institutional reciprocity will be perceived as more self-funded and having lower fiscal costs for the taxpayers, and thus contribute to a public perception that labour immigration is less costly for the national welfare state. In addition, social protection systems based on reciprocity typically provide better benefits and more adequate protection from socio-economic risks (Korpi & Palme, Citation1998). As a consequence, in public perception, a high degree of institutional reciprocity is likely to be associated with a smaller economic threat from EU labour migration, both to the national welfare system and people’s individual socio-economic security.

Institutional reciprocity may condition attitudes to EU labour immigration differently for different groups within a country. We follow a line of reasoning developed by Mewes and Mau (Citation2013), wherein they identify the risks that globalisation entails for lower economic strata in society. We reason that EU labour migration is something that first and foremost challenges vulnerable groups in society and particularly those with a weak standing on the labour market and/or a dependence on the social protection system as their main source of income. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these vulnerable groups are stronger opponents of EU labour immigration in our sample of receiving countries (see Appendix Figures A1, A2 and A3).

Because of their engagement with and dependence on the welfare system, the unemployed and other vulnerable groups are likely to have greater concerns than the general population about the ‘deservingness’ of EU workers as welfare recipients. Similarly, vulnerable groups are likely to be more concerned about the material effects of EU labour immigration. For example, the unemployed may be particularly worried that EU labour immigration leads to increased competition for jobs. While reciprocity in access to welfare benefits does not hinder such competition, it means that EU workers are more likely to be seen to contribute to the social insurance system in the host country and thus also to the benefits that the unemployed and other economically vulnerable groups typically rely on. Similarly, in a non-reciprocal system, the unemployed may be concerned that EU workers get immediate access to benefits based on need, which could be perceived as putting additional financial pressure on unemployment insurance and the wider social protection system. A higher degree of reciprocity can help ensure that EU workers have to make contributions to these systems before they can access benefits, thus potentially lessening concern among vulnerable groups that the resources of these systems would be ‘depleted’ by EU workers.

Taken together, this theoretical reasoning leads us to expect that greater institutional reciprocity in the national social protection system will lead to lower opposition to EU labour immigration, and thus free movement, among the public at large. We expect this relationship to be particularly strong among the unemployed and other economically vulnerable groups.Footnote1

Data and methods

We focus on 12 European countries that are major receiving countries of EU migrants: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK. Switzerland and Norway are not in the European Union but they follow EU rules for the free movement of workers by belonging to the European Economic Area (Norway) or through bilateral agreements (Switzerland). Our source of data on attitudes towards EU labour immigration is the European Social Survey (ESS). We use the Social Insurance Entitlements Dataset (SIED) (Nelson et al., Citation2020) and the Social Protection in EUrope DAtabase (SPEUDA) (Palme & Ruhs, Citation2018) to construct a novel indicator of institutional reciprocity in national social protection systems. Appendix Table A2 provides the descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables included in our analysis.

Dependent variable

To analyse public attitudes with relevance for the policy regime of free movement, we rely on data from the 2014 ESS which contains the most recent ESS module on the specific theme of immigration. Our dependent variable, Opposition to EU labour immigration, is well suited to capture public attitudes to the policy of free movement because it addresses the issue of immigration of EU workers rather than adhering to the more abstract phenomenon of ‘free movement’. It is taken from an ESS survey experiment that was designed to measure normative attitudes to different types of immigration. In the experiment, respondents were randomly assigned to answer only one of four items (for details, see Table A3 in the Appendix). The questions ask to what extent workers from other countries should be allowed to come to live in the respondent’s home country. All four items are identically worded, except in two regards: the skill level (professionals vs. unskilled workers) and country of origin of the migrants (European vs. non-European) were set to vary. The specific sending country mentioned to each respondent is that European or non-European country which sends the largest number of migrants to the respondent’s home country and is significantly poorer than the respondent’s home country.

As the survey experiment was not specifically designed for the study of attitudes to EU labour migration, we have to restrict our sample. First, we focus on the two items that measure attitudes to migrant workers coming from European countries. Respondents who answered the two items about non-European migrant workers are excluded from our analysis. Second, we further delimit our sample to 12 European receiving countries where the sending country referred to in the survey question is an EU member state. We then create one variable, Opposition to EU labour immigration, that combines the two items that tap attitudes to the immigration of ‘professionals’ and ‘unskilled workers’, respectively:

Please tell me to what extent you think [country] should allow professionals from [poor European country providing largest number of migrants] to come to live in [country]?

Please tell me to what extent you think [country] should allow unskilled labourers from [poor European country providing largest number of migrants] to come to live in [country]?

The selected data are well suited for our purposes. The items are contextualised, and relate to what EU labour immigration means in the real world. In our selected countries, respondents are asked about their attitudes to the largest group of EU workers coming to their country from a poorer EU Member State. The questions refer specifically to ‘professionals’ and ‘labourers’, and thereby focus directly on labour mobility rather than other forms of immigration.

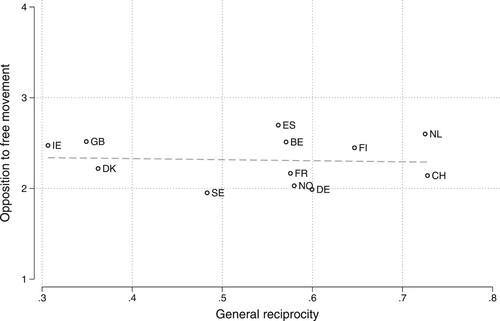

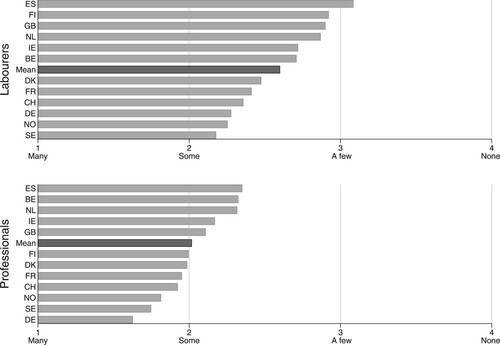

presents the average country-level opposition to EU labour immigration in our sample. Attitudes towards EU labour immigration of professionals are consistently more positive than those towards EU labour immigration of unskilled workers.

Figure 1. Opposition to EU labour immigration (labourers and professionals) in 12 European receiving countries, 2014. Source: European Social Survey Round 7 Data (Citation2014).

Independent variables at the country level

As our main independent variable, we use a novel measure of institutional reciprocity in national social insurance systems. Our index of institutional reciprocity in social insurance systems relates to both the financing and benefit sides of the system. On the financing side, we measure reciprocity as the proportion of financing that formally comes from the insured person, with the other two contributors being the employer and the state (taxation). Our data reflect the formal rules concerning contributions from these three sources. The reason for not including the employer’s contribution is our understanding of reciprocity in terms of a visible link between contributions and benefits. Arguably, the employer’s contribution is more often perceived as a tax than as an individual contribution. In addition, we want to avoid an overestimation of the contributiveness of social protection systems that rely almost exclusively on employers’ contributions in a way that resembles a (payroll) tax (notably in some Nordic countries).

The financing is measured for three social insurance programmes separately: pensions, unemployment insurance, and sickness cash benefits. Since work accident insurance programmes are typically funded exclusively by employers’ contributions, they would not add cross-national variation and are therefore not included on the financing side of our index. We first calculated three variables expressing the proportion of financing by the insured person for pensions, sickness insurance, and unemployment insurance, respectively. We then calculated the Financing index as an average of the three programme-specific financing variables (pensions, sickness, and unemployment).

On the benefit side, we use two different indicators for the four major social insurance programmes: pensions, unemployment insurance, sickness insurance and work accident insurance. The first indicator is the net replacement rate (social insurance benefit net of taxes divided by wage net of taxes) for what we have labelled a ‘full worker’, i.e., someone who fulfils all contribution requirements and earns an average wage. The second indicator is the replacement rate for the maximum benefits possible as a proportion of the average wage. We have applied a cap of 1.5 in order to avoid problems arising from outliers and influential cases caused by the fact that a few countries have very high ceilings for benefit purposes (or no ceiling at all). The benefit index was calculated in a stepwise procedure. We first take the mean of the two replacement variables by programme. In a second step, we take the mean of the four programme indices to attain the Benefits index. The index captures two aspects of earnings-relatedness. The ‘full worker’ replacement rate measures the degree of earnings-relatedness, which is an important aspect of reciprocity, and the ‘maximum benefit’ indicates how high up in the earnings distribution this principle applies.

We then computed a general Reciprocity index, calculated as the average of the Benefits index and the Financing index. We have used the same procedure to calculate a separate reciprocity index for unemployment insurance. Our choice of an additive index (of the financing and benefits indices) is guided by our understanding of reciprocity as a theoretical concept that is as much about contributiveness as earnings-relatedness.

We have access to institutional data for 2010 and 2015. Since we can expect a lagged effect of the institutional variables, we use the 2010 scores because they precede the year (2014) when the dependent variables were measured (see Appendix Figure A4). The country ranking in institutional reciprocity is reasonably stable between 2010 and 2015. Some countries score high on the financing dimension but not on the benefit dimension, whereas others score high on the benefit dimension but not on the financing side. In other words, the empirical correlation between the two components in our reciprocity index is low.Footnote2 However, our motive for adding the two components is not based on their empirical correlation but on the theoretical argument that they capture different parts of the same underlying variable (reciprocity).

Our dataset covers 12 of the 15 main European migrant-receiving countries. Although this provides a satisfactory coverage of the available cases, it leaves us with a small number of country-level observations. We, therefore, strive to include a limited number of country-level control variables. Following Vasilopoulou and Talving (Citation2018), we expect that the wealth of a country may influence both its choice of welfare policy and public attitudes to immigration, and therefore include GDP per capita as our first control variable. Even among our sample of countries that are net-receivers of EU workers, there are considerable differences in average incomes (see Figure A6 in Appendix). Moreover, the institutional underpinnings of the national economies in our sample exhibit important differences as suggested by the Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) perspective (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001). Liberal market economies have more fluid and accessible labour markets with lower levels of employment protection, whereas labour markets in coordinated market economies tend to invest in individual workers’ skills and provide higher levels of employment protection. Such institutional differences can impact welfare state design as well as attitudes to labour immigration. We thus include VoC indicators as country-level controls. Following Hall and Gingerich (Citation2009), we classify the UK and Ireland as Liberal Market Economies (LMEs); Belgium, Finland, Germany, Denmark, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland as Coordinated Market Economies (CMEs); and Spain and France as Mixed Market Economies (MMEs). MMEs constitute the reference category in our analysis.

Independent variables at the individual level

Our key independent variable at the individual level indicates whether the respondent self-identifies as unemployed (see the Appendix for details). We also include a set of standard individual-level control variables (e.g., Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2018), reflecting the respondent’s Age, Gender, Left-Right placement, Main Activity, and if the respondent is Self-Employed or has Low education. Low education is a dummy indicating that the respondent’s highest level of education is primary or secondary education. We also control for being Foreign-born and for having foreign-born parents.

Empirical model

Our data imply some challenges for the specification of the empirical model. Because of the limited variation at the country-level, with only cross-sectional data for 12 countries, we can include very few country-level variables. A common model for data with a combination of country-level and individual-level variables is a multi-level model. Even though these models are popular they offer ‘no panacea’ (Bryan & Jenkins, Citation2015) to issues of limited upper-level variation. Since multi-level models are vulnerable to a small number of upper-levels units, using such models for fewer than 25–30 upper-level units is likely to result in unreliable and biased estimates (Bryan & Jenkins, Citation2015). This is particularly the case with more complex models including cross-level interactions. Furthermore, with as few as 12 upper-level observations it is effectively impossible to include a sufficient number of upper-level variables to adequately model the country-level variation to avoid the risk of omitted variable bias (Möhring, Citation2012).

Against this backdrop we have chosen another method, using standard OLS with country-fixed effects in our more rigid specifications. However, applying country fixed effects means it is impossible to estimate any direct effects of institutions since there is no macro-level variation left. We may thus only use the country-fixed effects models for the study of cross-level interactions and individual-level variables. Country fixed effects absorb all of the average differences in the dependent variable across countries and lessen issues of omitted variables bias on the country-level. Such models, therefore, offer an attractive alternative for the study of cross-level interactions where limited upper-level variation makes the use of multi-level models questionable (Möhring, Citation2012). To account for the clustered nature of our data we apply country-clustered robust standard errors.Footnote3

Results and discussion

The scatter plot in shows the distribution of attitudes to EU labour immigration and reciprocity across our 12 receiving countries. As portrayed by the fitted line, there is effectively no relationship between the two variables in the data. However, motivated by our theoretical reasoning and expectations, we will continue with a more in-depth assessment of country- and individual-level factors that might affect attitudes to EU labour immigration.

Our regression results in allow a more thorough consideration of how reciprocity in the social protection system is related to attitudes to EU labour immigration. All models in the table include the experimental dummy Professionals that indicates if a respondent answered the item that casts EU workers as ‘professionals’ as opposed to ‘unskilled labourers’. While the random assignment behind the variation in this variable implies that it is uncorrelated with all other independent variables, we control for it to improve precision.

Table 1. Regression analysis of opposition to EU labour immigration on institutional reciprocity in 12 EU and EFTA receiving countries.

The first two models test our expectation that there is a negative relationship between institutional reciprocity and opposition to EU labour immigration among the public at large. Since the dependent variable represents opposition towards EU labour immigration, positive estimates imply an increase in opposition towards EU labour immigration. Model (1) only includes general reciprocity and the (experimental) dummy Professionals. In this specification, the effect of reciprocity is slightly negative, which is in line with our theoretical expectation, but it is far from statistically significant. The coefficient estimate for the Professionals dummy is negative and significant at the 99 per cent level, confirming that there is less opposition towards EU labour immigration of professionals than that of unskilled labourers.

In Model (2) we add GDP per capita and VoC controls to account for economic and institutional differences in labour markets across countries. Contrary to our expectation, the effect of reciprocity now becomes positive (and more sizable), but it remains statistically insignificant. Adding the individual controls makes little difference to this result (not shown). Thus, we do not find support for our expectation that general institutional reciprocity is connected to less opposition to EU labour immigration.

Model (3) shows that the unemployed are more sceptical towards EU labour immigration, significant at the 95 per cent level. The following Model (4) adds an interaction between unemployment and reciprocity to explore how reciprocity conditions the effect of unemployment on attitudes to EU labour immigration. In line with our expectation, we find that reciprocity mitigates opposition to EU labour immigration among the unemployed, as indicated by the negative interaction coefficient. In other words, the unemployed tend to be less opposed to EU labour immigration in countries where there is a higher degree of reciprocity in the social protection system. The estimate of the interaction term is not statistically significant, but the significance of interaction effects should not be assessed on the basis of the coefficient alone (Brambor et al., Citation2006). Further below, we complement the regression results with a marginal effects plot to facilitate interpretation (additional marginal effects plots are presented in the Appendix).

In Model (5) we add a set of individual-level controls, but these only marginally affect our main estimates for Reciprocity, Unemployed and the interaction between the two. The following Model (6) applies country fixed effects. As a consequence, the coefficients for the previous country-level variables can no longer be estimated. Nevertheless, the fixed effects model represents a stricter test of the cross-level interaction between unemployment and reciprocity, as general country-level differences are controlled for, whether observed or unobserved. The coefficient for the interaction actually becomes larger than in previous models and is also more precisely estimated. This results in the coefficient becoming statistically significant at the 95 per cent level (p = 0.037), which is in line with our expectations.

Finally, in Model (7) we test whether the cross-level interaction between unemployment and reciprocity is sensitive to the addition of controls at the interaction level. In these models, we interact reciprocity with all of the other individual-level controls, while still applying country fixed effects. That way, we are able to explore whether the conditional effect of reciprocity on the impact of unemployment could be a result of a relationship on the interaction-level with any of these controls. Reassuringly, the point estimate of the interaction coefficient becomes substantially larger and is still significant at the 95 per cent confidence level. This further strengthens the support for the argument that reciprocity actually conditions attitudes to EU labour immigration among the unemployed, and that this conditional effect does not appear to be due to other individual-level characteristics that are correlated with unemployment.

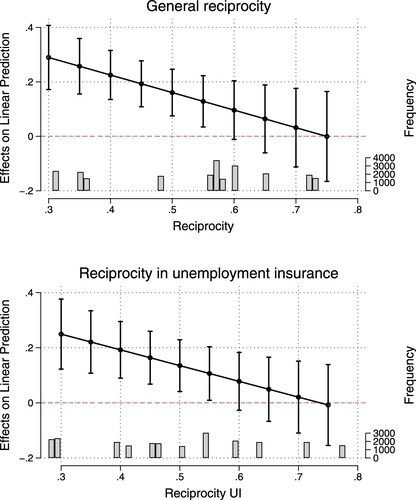

The marginal effects plot presented in the upper panel of highlights our findings in relation to our expectation about the relationship between reciprocity in the social insurance system and opposition to EU labour immigration among the unemployed. The plot is based on Model (7) in . The negative slope shows that unemployment is related to stronger opposition towards EU labour immigration in contexts where there is a lower degree of reciprocity in the social insurance system. For higher levels of reciprocity, the scepticism towards EU labour immigration diminishes among the unemployed. In our sample of countries, the degree of reciprocity is lowest in Ireland (0.31), the UK (0.35) and Denmark (0.36), whereas it is highest in the Netherlands (0.73), Switzerland (0.73) and Finland (0.65). In a minimally reciprocal country such as Ireland, being unemployed is strongly associated with opposition to EU labour immigration (the point estimate for the effect of unemployment would equal 0.28, p = 0.00). In a maximally reciprocal context such as the Netherlands or Switzerland, in contrast, unemployment has effectively no effect on attitudes to EU labour immigration (point estimate 0.01, p = 0.87).

This result supports our expectation that reciprocity in social protection systems may work against the perception of welfare policy as an area where natives and EU workers are pitted against one another in a struggle for societal resources. While the unemployed on average are more opposed to EU labour immigration, they perceive EU workers as more deserving welfare recipients and/or less of an economic threat in countries where social benefits have to be ‘earned’ by natives and EU workers alike.

The models in relate to the degree of reciprocity in the social protection system at large. As a final step in our empirical analysis, we shift our focus from the impact of general reciprocity in the social protection system to that of reciprocity in unemployment insurance specifically. The design of unemployment insurance should be especially salient for the unemployed, as it is their current source of income.

In the lower panel of , we show the marginal effect of individual unemployment on opposition towards EU labour immigration at different levels of reciprocity in unemployment insurance. We use a model corresponding to Model (7) in with country fixed effects and individual-level controls interacted with unemployment insurance reciprocity. Reciprocity in unemployment insurance has a strikingly similar conditioning effect on attitudes to EU labour immigration as general reciprocity. The interaction coefficient is also significant at the 95 per cent level. A higher level of reciprocity in unemployment insurance serves to offset opposition towards EU labour immigration among the unemployed.

Figure 3. Marginal effect of being unemployed on attitudes to EU labour immigration, varying the degree of reciprocity in the social protections system generally (upper panel) and in unemployment insurance (lower panel). Notes: 95% confidence intervals. The plot for general reciprocity is based on Model (7) in Table 1, and the plot in the lower panel is based on a corresponding model for reciprocity in unemployment insurance (included in Appendix Table A6).

We run a set of additional models to check the robustness of our results (see Appendix). First, as an alternative to our focus on the unemployed, we study economic vulnerability more directly by using a measure that reflects whether the respondents experience economic insecurity. When we rerun our interaction models with this measure, the estimates are similar to those for unemployment. Second, we use wild cluster bootstrap to test if the significance of our results is sensitive to the use of cluster-robust standard errors. This alternative procedure tends to result in slightly wider confidence intervals for our central estimates but they remain significant. Third, we confirm the linearity of the interaction between reciprocity and unemployment (Hainmueller et al., Citation2019). Fourth, we test the impact of a set of additional country-level control variables to ascertain the role of institutional reciprocity in our findings, including overall welfare generosity (e.g., Hanson et al., Citation2007), the immigrant share of the population (e.g., Braakmann et al., Citation2017), and employment protection legislation (e.g., Ruhs, Citation2017). We add these controls both at the country-level and interact them with individual unemployment. Adding welfare generosity results in less precise estimates of the reciprocity-unemployment interaction but the point estimates are similar or slightly larger and the marginal effects are comparable. The other controls barely affect the interaction or, alternatively, only make it more pronounced. The effect of reciprocity also remains insignificant among the population at large in all of these additional models.

Conclusion

In our analyses of ESS data for 12 European countries that are net-receivers of EU migrants, we find no significant direct effect of reciprocity in social protection systems on opposition to EU labour immigration among the population at large. This may be because most people are sufficiently resourceful, so that social protection, at least under normal circumstances, does not matter for their position on EU labour immigration. However, we find a significant interaction between the reciprocity of social protection and the employment status of the respondents, both for general reciprocity and for reciprocity in unemployment insurance specifically. Our results suggest that in countries where the social protection systems in general, or the unemployment insurance systems specifically, are based on higher degrees of reciprocity, the unemployed are significantly less opposed to EU labour immigration than their counterparts in countries with lower degrees of reciprocity. Moreover, this pattern appears to apply not only to people who are unemployed but also to economically vulnerable groups more generally.

Our analysis leaves room for different interpretations. One interpretation follows our ideational ‘Leitmotif’ in this paper, namely, that institutional characteristics of welfare states that have a strong normative dimension, such as reciprocity, can affect EU workers’ opportunities to ‘earn’ a status as deserving of welfare provision in the eyes of vulnerable groups such as the unemployed. Some prior findings suggest that there is an immutable ‘deservingness gap’ between natives and migrants in the eyes of the public (see e.g., Reeskens & van der Meer, Citation2019; Van Oorschot, Citation2006). Our results suggest that institutional characteristics related to reciprocity in welfare institutions may play an important role in relation to welfare ‘deservingness’ of migrants (also see Nagayoshi & Hjerm, Citation2015), and that these dynamics warrant further analysis (see Nielsen et al., Citation2020).

Our findings are also congruent with theories that stress the role of perceived fiscal burdens for the formation of attitudes to immigration since social protection based on reciprocity may be seen as self-funded and less of a fiscal threat. Moreover, the results are in line with the view that social protection systems may condition attitudes, not only to immigration but also to globalisation, especially among economically vulnerable groups, by materially protecting the population from the economic threats that these processes may entail (e.g., Gingrich, Citation2019).

Either way, our research suggests that the design of national welfare institutions may play an important role in reducing the tensions that can arise between national welfare states and unrestricted immigration (e.g., Freeman, Citation1986). High degrees of reciprocity in social protection systems can provide a ‘shield’ against opposition to EU labour immigration among vulnerable groups in EU host countries – and thus against public opposition to the politically contested issue of free movement of workers. Our work makes clear that analysing how and what precise aspects of welfare institutions reduce opposition to immigration, and among which specific groups, represents a formidable challenge for comparative research. In this endeavour, our analysis has shown that it is fruitful to go beyond the common ‘regime approach’ by exploring institutional variations with a ‘variable approach’ that focuses on specific aspects of welfare institutions that may be particularly relevant to public attitudes towards immigration. This is also relevant from a policy perspective since it is more realistic for EU Member States to reform some characteristics of their social protection programmes than to replace an entire welfare state regime.

Statistical replication materials and data

Supporting data and materials for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HTYQVK.

Supplemental Appendix

Download PDF (819.2 KB)Acknowledgements

For their helpful comments, we would like to thank three anonymous reviewers and the editors of JEPP. We are also grateful to our colleagues in the Horizon-2020 funded REMINDER project and participants in workshops at Oxford, Uppsala, and the EUI.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Moa Mårtensson

Moa Mårtensson, researcher, Department of Government, Uppsala University, Uppsala Center for Labor Studies (UCLS).

Marcus Österman

Marcus Österman, researcher, Department of Government, Uppsala University, Uppsala Center for Labor Studies (UCLS).

Joakim Palme

Joakim Palme is Professor at the Department of Government, Uppsala University, the Uppsala Center for Labor Studies (UCLS).

Martin Ruhs

Martin Ruhs is Professor of Migration Studiesat the Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute, and Associate Professor of Political Economy (on leave) at the Department for Continuing Education, University of Oxford.

Notes

1 Our expectations apply to the entire population of citizens and long-term residents in host countries, including persons with a migrant background.

2 Our data indicate that these two aspects of reciprocity are empirically distinct and hardly even correlated (Pearson’s r –0.10, see Appendix Figure A5).

3 Only 12 clusters can be an issue when using clustered robust standard errors. We follow the recommendation by Cameron and Miller (Citation2015) and use a correction for the degrees of freedom. Additionally, we run a robustness test using the wild cluster bootstrap procedure.

References

- Blinder, S., & Markaki, Y. (2018). Europeans’ attitudes to immigration from within and outside Europe: A role for perceived welfare impacts? REMINDER Working Paper, Oxford.

- Blinder, S., & Markaki, Y. (2019a). The effects of immigration on welfare across the EU: Do subjective evaluations align with estimations? REMINDER Working Paper, Oxford.

- Blinder, S., & Markaki, Y. (2019b). Acceptable in the EU? Why some immigration restrictionists support European Union mobility. European Union Politics, 20(3), 468–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116519839782

- Böhmelt, T. (2019). How public opinion steers national immigration policies. Migration Studies, Article mnz039. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnz039

- Braakmann, N., Waqas, M., & Wildman, J. (2017). Are immigrants in favour of immigration? Evidence from England and Wales. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 17(1), 2016–0029. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2016-0029

- Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpi014

- Bryan, M. L., & Jenkins, S. P. (2015). Multilevel modelling of country effects: A cautionary tale. European Sociological Review, 32(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv059

- Cameron, D. (2013, November 26). Free movement within Europe needs to be less free. Financial Times.

- Cameron, C., & Miller, D. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.50.2.317

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

- European Social Survey Round 7 Data. (2014). Data file edition 2.2. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS7-2014

- Facchini, G., & Mayda, A. M. (2009). Does the welfare state affect individual attitudes toward immigrants? Evidence across countries. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(2), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.91.2.295

- Freeman, G. (1986). Migration and the political economy of the welfare state. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 485(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716286485001005

- Gingrich, J. (2019). Did state responses to automation matter for voters? Research & Politics, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168019832745

- Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2014). Public attitudes toward immigration. Annual Review of Political Science, 17(1), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818

- Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., & Xu, Y. (2019). How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis, 27(2), 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.46

- Hall, P. A., & Gingerich, D. W. (2009). Varieties of capitalism and institutional complementarities in the political economy: An empirical analysis. British Journal of Political Science, 39(3), 449–482. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409000672

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Hanson, G. H., Scheve, K., & Slaughter, M. J. (2007). Public finance and individual preferences over globalization strategies. Economics & Politics, 19(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2007.00300.x

- Hobolt, S. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Huber, P., & Oberdabering, D. (2016). ‘The impact of welfare benefits on natives’ and immigrants’ attitudes toward immigration’. European Journal of Political Economy, 44, 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.05.003

- Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality and poverty in the western countries. American Sociological Review, 63(5), 661–687. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657333

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge University Press.

- Larsen, C. A. (2020). The institutional logic of giving migrants access to social benefits and services. Journal of European Social Policy, 30(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928719868443

- Lutz, P. (2020). Loved and feared: Citizens’ ambivalence towards free movement in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 268–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1720782

- Mårtensson, M., Palme, J., & Ruhs, M. (2019). Reciprocity in welfare institutions and normative attitudes in EU Member States. REMINDER Working Paper, Oxford.

- Mårtensson, M., & Uba, K. (2018). Indicators of normative attitudes in Europe: Welfare, the European Union, Immigration and Free Movement. REMINDER Working Paper, Oxford.

- Meltzer, C., Eberl, J.-M., Theorin, N., Heidenreich, T., Stromback, J., & Boomgarden, H. G. (2020). Media effects on policy preferences toward free movement: Evidence from five EU member states. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(15), 3390–3408. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1778454

- Mewes, J., & Mau, S. (2013). Globalization, socio-economic status and welfare chauvinism: European perspectives on attitudes towards the exclusion of immigrants. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 54(3), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715213494395

- Möhring, K. (2012). The fixed effects approach as alternative to multilevel models for cross-national analyses. GK SOCLIFE Working Paper Series, 16/2012.

- Nagayoshi, K., & Hjerm, M. (2015). Anti-immigration attitudes in different welfare states: Do types of labor market policies matter? International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 56(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715215591379

- Nelson, K. (2003). Fighting poverty: Comparative studies on social insurance, means-tested benefits and income redistribution. Dissertation Series No. 60. Swedish Institute for Social Research.

- Nelson, K., Fredriksson, D., Korpi, T., Korpi, W., Palme, J., & Sjöberg, O. (2020). The social policy indicators (SPIN) database. International Journal of Social Welfare, 29(3), 285–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12418

- Nielsen, M., Frederiksen, M., & Larsen, C. A. (2020). Deservingness put into practice: Constructing the (un)deservingness of migrants in four European countries. The British Journal of Sociology, 71(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12721

- Österman, M., Palme, J., & Ruhs, M. (2018). National institutions and the fiscal effects of EU migrants. REMINDER Working Paper, Oxford.

- Palme, J., & Ruhs, M. (2018). Indicators of labour markets and welfare states in the European Union. REMINDER Working Paper, Oxford.

- Rasmussen, A., Reher, S., & Toshkov, D. (2019). The opinion-policy nexus in Europe and the role of political institutions. European Journal of Political Research, 58(2), 412–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12286

- Reeskens, T., & van der Meer, T. (2019). The inevitable deservingness gap: A study into the insurmountable immigrant penalty in perceived welfare deservingness. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(2), 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718768335

- Reeskens, T., & Van Oorschot, W. (2012). Disentangling the ‘new liberal dilemma’: On the relation between general welfare redistribution preferences and welfare chauvinism. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 53(2), 120–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715212451987

- Ruhs, M. (2017). Free movement in the European Union: National institutions vs common policies? International Migration, 55(S1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12398

- Ruhs, M., & Palme, J. (2018). Institutional contexts of political conflicts around free movement in the European Union: A theoretical analysis. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(10), 1481–1500. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1488883

- Sainsbury, D. (2012). Welfare States and Immigrant Rights. Oxford University Press.

- Scruggs, L. (2006). The generosity of social insurance, 1971–2002. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 22(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grj021

- Van Der Waal, J., De Kosterand, W., & Van Oorschot, W. (2013). Three worlds of welfare chauvinism? How welfare regimes affect support for distributing welfare to immigrants in Europe. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 15(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2013.785147

- Van Oorschot, W. (2006). Making the difference in social Europe: Deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928706059829

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Talving, L. (2018). Opportunity or threat? Public attitudes towards EU freedom of movement. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(6), 805–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1497075