ABSTRACT

Recent studies provide evidence that income inequality is a relevant driver for the electoral success of populist parties all over Europe. In this article, we aim to understand how exactly increasing income inequality can lead to support for populist parties. More specifically, we discuss four different attitudinal mechanisms from previous research: economic insecurities, trust in political elites, social integration, and national identity. We rely on eight waves of the European Social Survey and find that economic insecurities, trust in political elites, and national identity are linked to rising income inequality and populist support as expected. However, a causal mediation analysis shows that these mechanisms are not sufficient to fully understand the impact of income inequality on support for populists. This finding raises questions regarding the empirical support of existing theories to explain how macroeconomic changes in inequality became a pre-condition for the rise of populist parties.

Most democratic societies have experienced a rapid increase in income inequalities over the last decades. Across OECD countries the average share of disposable income that is earned by the top 10% earners has increased and is now around 9.5 times higher than the income of the bottom 10%. In the same period, liberal democracies find themselves challenged by populist parties, which separate society into two homogeneous groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’ and who want to implement the general will of the people irrespective of existing liberal democratic institutions. While mainstream parties suffer dramatic electoral losses, right-wing and left-wing populist parties are on the rise all over Europe (Spoon & Klüver, Citation2019). In 1990 populist parties received around 10% of the vote in democracies, in 2016 they received around 25% of the votes.

Previous research suggests that increasing income inequality is a major driver for the rise of populist and radical parties in recent years (Coffé et al., Citation2007; Engler & Weisstanner, Citation2021; Han, Citation2016; Jesuit et al., Citation2009). Engler and Weisstanner (Citation2021), for example, find evidence that a long-term increase in income inequality has a positive effect on support for radical right parties. Han (Citation2016) similarly finds that income inequality increases radical right-wing support among manual workers and routine non-manual workers. The literature suggests four potential mechanisms that could explain why rising levels of inequality draw voters towards populist and radical right parties. First, one line of thought suggests that economic insecurities that are generated by larger income inequalities either via relative deprivation (Betz, Citation1994; Runciman & Baron, Citation1966) or increasing risks (Moene & Wallerstein, Citation2001; Rehm, Citation2016) are the major channel through which inequality affects populist support. Second, others see a central role in the stratification effect of inequality and the resulting process of social disintegration (Gidron & Hall, Citation2017, Citation2020). Third, Rooduijn (Citation2018) suggests that inequality results in reduced trust in political elites which explains why voters abandon established parties and turn to populist and radical challengers. Finally, it has been suggested that the social (national) identity shifts that result from more unequal distributions of income are a key driver of the populist vote (Han, Citation2016; Shayo, Citation2009).

In this study, we provide a comprehensive empirical test of the four proposed theoretical mechanisms to better understand how income inequality affects support for populist parties all over Europe. While the outlined arguments, economic insecurities, social integration, trust in political elites, and national identity, have been tested by studying if they influence support for radical and populist parties(see e.g., Gidron & Hall, Citation2017; Rooduijn, Citation2018) and if income inequality affects those channels the results have been conducted largely in isolation from each other. Prior studies do not empirically evaluate which of the different channels are at work when relating income inequality to the rise of populist parties. To do so, we focus on attitudinal changes that are central implications of the different arguments. If income inequality, for example, generates larger economic insecurities and deprivations which leads to support for populist parties, people should negatively evaluate their income situation and turn to populists because of it.

We use data from fourteen West European countries from the European Social Survey (ESS) and merge it with the Standardized World Income Database (SWIDD) (Solt, Citation2016). Our data covers the period from 2002 to 2016, in which both support for populist parties has risen from 13% to above 20% and the market income inequality Gini increased from 45 to 49 on average. The ESS contains survey questions that map into the different theoretical mechanisms and allow us to evaluate the mediation role of the different channels.

Using multilevel models we find that disposable income inequality increases the support for populist parties. A one-unit increase in the GINI increases the support by one percentage point. The different concepts further predict populist vote. Respondents are more likely to support populist parties if they face economic insecurities, distrust elites, are socially disintegrated, and hold national identities. Income inequality further affects distrust in political elites, economic insecurities, and national identity, making them potential explanations for the positive effect of inequality. We further analyze the mediation role of the different concepts using controlled direct effects and find no evidence that holding the attitudinal channels constant completely reduces the effect of inequality on support for populists. There is some indication that trust in political elites can serve as a partial explanation of the effect. Overall, this implies that the attitudinal implications of the theories are not sufficient to explain the relationship between income inequality and support for populist parties.

Our findings thereby raise a set of important questions regarding the empirical relevance of existing theories that researchers have used to explain how changes in inequality became a pre-condition for the rise of populist parties all over Europe. The findings do not promote the view that changes in the allocation of income affect economic attitudes and those fuel support for actors that bring about internal contestations to liberal institutions. Nor do they establish the interpretation that higher levels of inequality raise distrust in political elites, paving the way for populist platforms. With this, the finding calls for further research to get a clearer understanding of how income inequality creates electoral demand for populist parties.

Income inequality and support for populist parties

In this section, we review the literature on how changes in inequalities influence the support for populist parties. We focus on populist parties, as they have been portrayed as one of the central challenges to representative democracies in Europe (Kriesi, Citation2014). We work with the ‘ideational’ definition of populism. According to this definition, populism is ‘a thin-centred ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, the pure people versus the corrupt elite, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde, Citation2004, p. 543). Populism can have different ‘host ideologies’ that are often found at the radical ends of the political spectrum (Loew & Faas, Citation2019; Rooduijn & Akkerman, Citation2017). Right populist parties put forward programs based on nationalism, authoritarianism, and cultural conflicts (Mudde, Citation2007). Left populists focus on issues of economic allocations and inequalities as a source of their radicalization (March & Mudde, Citation2005) Most previous research focuses on important micro-level features of support for populist parties, such as the effects of occupational groups, education, and income (see e.g., Bornschier & Kriesi, Citation2012; Rooduijn, Citation2018).

Despite the severe political implications that rising inequality carries, only a handful of studies have investigated how inequality is linked to the support of populist parties. The existing studies focus on how inequality impacts the success of populist parties focus on the radical right. Coffé et al. (Citation2007) finds that income inequality is negatively associated with support for the Vlaams Blok in Belgium. Jesuit et al. (Citation2009) draw upon the results of 14 national election results of populist radical right parties held in eight countries between 1992 and 2000 and find no direct evidence for the effect of income inequality, but can show that inequality moderates the relationship between immigration and support for this party family. Han (Citation2016) suggest that socioeconomic inequality moderates the link between individual-level income and radical right voting. While income inequality increases radical right-wing support among manual workers and routine non-manual workers, the opposite is true among managers/professionals. Most recently, Engler and Weisstanner (Citation2021) ‘argue that rising inequality not only intensifies relative deprivation but also signals a potential threat of social decline’ (Engler & Weisstanner, Citation2021, p. 153). They show that, especially, long-run changes in income inequality increase the support for radical right parties among individuals with high subjective social status and lower-middle incomes. Most of the outlined studies analyze radical right parties that combine three main features: nativism, authoritarianism and also populism (Mudde, Citation2004), making the results informative to our study on populist parties. Our research deviates from those prior studies by focusing explicitly on populist parties in general, extending the existing perspective.

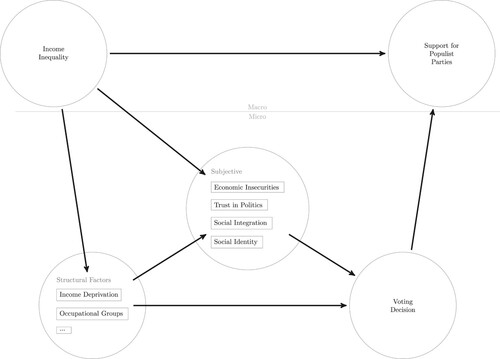

What is still missing in the debate is empirical evidence of how exactly the increasing inequalities drive people to populist parties. The aforementioned studies refer to different arguments why we should observe a relationship between inequality and support for populists but do not evaluate the suggested causal mechanisms empirically. A clear understanding of the pathways would strengthen the existing evidence and provide a more pronounced picture of how macroeconomic changes affect voters’ decisions to support populist and radical challenger parties. To study this, we work with a conceptual framework that links income inequality to the support for populist parties on the macro-level and breaks it down to different paths on the micro-level. shows the framework.

The first link between income inequality and the micro-level are structural factors, such as occupational groups and income deprivation. Higher inequality lead to more people with lower incomes, which increases income deprivation. It also influences occupational groups as the stratification between occupational groups and the attached social status broadens as a consequence of larger inequalities. This relationship is mechanical and both factors are known to increase the vote for populist parties (see e.g., Bornschier & Kriesi, Citation2012; Rooduijn, Citation2018). What we are particularly interested in, however, is to test different attitudinal mechanisms how these structural and macro changes in the distribution of income bring about support for populists. These intermediate subjective factors are found in the figure in between structural changes and voting decisions.

How does income inequality lead to support for populist parties?

Reviewing the literature we condense four attitudinal mechanisms that could explain a positive effect of inequality on the support for populists: Economic insecurities, social integration, trust in political elites, and social (national) identity.Footnote1

First, the most prominent mechanisms are economic insecurities and deprivations that are found in the study of radical right parties. Studies that evaluate the impact of inequality and other macroeconomic factors argue, for example, that ‘rising income inequality is an important indicator not only of the extent to which some groups have fallen behind compared to others but also of the potential decline in society that people higher up in the social hierarchy could face.’ (Engler & Weisstanner, Citation2021, p. 153). Arguments along those lines build on theories of ‘relative deprivation’ (Betz, Citation1994; Runciman & Baron, Citation1966), according to which stronger economic inequality leads a larger share in the population to feel that they have fallen behind and as a result turns to radical or populist parties. Or they are based upon ‘risk theories’ (Moene & Wallerstein, Citation2001; Rehm, Citation2016) that argue that in presence of higher inequalities people fear the strong potential societal decline and therefore turn towards radical and populist alternatives. The second mechanism recently received attention with studies showing that especially voters who can expect to lose income and social status turn to radical right parties (Kurer, Citation2020). Inequality then either increases the risks or the income deprivation relative to others in society. On the attitudinal level, this should result in economic insecurities that make people more likely to vote for populist parties. For this mechanism, it is important to differentiate the radical platforms (nativism and authoritarianism) from populism. While the above-mentioned studies focus on the radical right, we contest that this mechanism can also explain support for populist parties in general. With increasing economic insecurities voters are attracted by the populist appeal to represent their interest against mainstream politics, either via nativist appeals on the right or strong redistributive platforms on the left (see e.g., Ramiro & Gomez, Citation2017).

Second, the social integration argumentation has recently been put forward by Gidron and Hall (Citation2020). It is more focused on the cultural determinants for the support of populist parties. The central argument states that particular people who are socially marginalized ‘are more likely to be alienated from mainstream politics and […] support radical parties’ Gidron and Hall (Citation2020, p. 1027). Socially integration then refers to a sense that people hold up valuable relations with other members of their community. The link to inequality is straightforward. Higher-income inequality and social stratification result in a larger share of voters who feel socially-marginalized and as a result, turn their back to mainstream politics and towards populist challengers. Turning their backs to mainstream politics should benefit both left and right-wing populists. On the attitudinal level, the idea of social integration should manifest itself in subjective social status and distrust in social relationships and equally influence support for populist parties on both side of the aisle.

Third, recent work argues that social (national) identity can play a central role when understanding the link between inequality and support for populist right parties. Shayo (Citation2009) presents a theoretical model in which income inequality increases the attractiveness of national over class identity for the low-income segments, making particular nativist parties more appealing. Han (Citation2016) used this theoretical argument to show that particular low-income segments in society turn towards the populist right. In how far social identity works as a mediator for the relationship between inequality and populism has not been studied. It should show that under higher levels of inequality people turn to national identities and as a result vote for populist right parties. This channel is suited to explain support for right-wing populist parties in conjunction with nativist appeals and is expected to be less important for left-wing populist parties.

Fourth, another channel that is more directly linked to the key conceptualizations of populism is trust in political elites. Trust in political elites is a central aspect of populist ideology in portraying current representation by mainstream parties as corrupt and biased. Accordingly, respondents who do not trust established parties and politicians are more likely to vote for populist parties on both sides of the ideological spectrum (Rooduijn, Citation2018). What is missing for trust to be a central mediator is that inequality also substantially impacts trust in political elites. It can be argued that observing unequal outcomes and going through economic deprivations can reduce trust in the actors responsible for the policies, which are established parties and parliaments. For example, research finds evidence inequality is related to trust in governing institutions (Lipps & Schraff, Citation2020). With this, we should observe that inequality reduces trust in political elites and that people who distrust the elite are more likely to support populist parties. The mechanism should increase the appeal of both populist parties on the left and right of the political spectrum.

The mechanisms can work for different segments of society. For example, with increasing inequality less affluent parts of the society could experience relatively more insecurity than the rich. This type of insecurity might further be more pressing and behavioral consequential. Economic insecurity should then especially explain the effect for the less affluent parts. Occupational groups and income segments play a central role in this type of moderated mediation. For example, Han (Citation2016) identifies differential effects between occupational classes and Engler and Weisstanner (Citation2021) between income segments. To consider the possibility that it also matters for the mediation role, we will analyze if the different channels apply to different income segments and occupational groups.

To sum up, previous studies indicate that income inequality influences the support for populist parties. The literature further builds on a set of theoretical argumentations why this link should exist. Some of the mechanisms have only been linked to the support for populist right parties (e.g., social identity), but as discussed especially trust, social marginalization and economic insecurities should play a central role in understanding the positive effect on populist support in general.

Data and methods

The European social survey & the standardized world income database

Our analysis relies on data from nine waves of the European Social Survey (ESS) fielded between 2002 and 2017. We focus on 14 West-European countries that faced similar structural changes in the economy but experienced slightly different trends in the success of populist parties and the increase of income inequality over the period under study.Footnote2

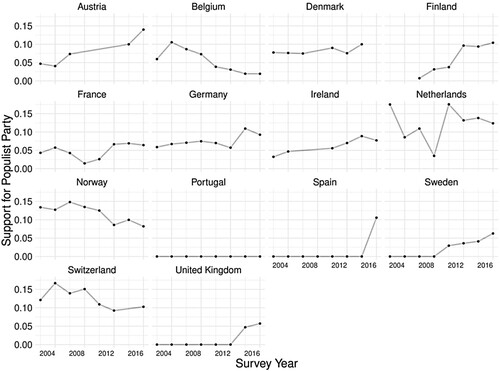

The dependent variable of our analysis is the support for populist parties in a country. We rely on the PopuList to identify parties in the ESS sample that are categorized as populist (Rooduijn et al., Citation2019). The PopuList is compiled by a team of country experts that identify parties as populist, far right, far left, and eurosceptic in Europe since 1989.Footnote3 The ESS includes a vote recall question. Given that the ESS is fielded irrespective of the election dates every two years the concerning election can be up to 4 years in the past or even during the field period. The fact that we work with a vote recall question allows us to either study the effect of inequality on the election year or the survey year. In the main analysis, we report on the election year. As part of the robustness checks, we report on the results when merging on the survey year. To get an idea of the evolution of support for populist parties in our countries, shows the respondents’ support of populist parties in the different ESS survey waves. We observe different patterns over the period under study. In Switzerland, we observe a high level of support for the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) over the entire period. Portugal registers no support for populist parties, as none of the parties is categorized as populist. We also observe increases in countries like France (especial support for the Front National), Germany (with the support for the and AFD and die Linke), or Austria with increasing support for the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ).

To obtain a measure of our main independent variable, we merge the ESS with the Standardized World Income Database (SWIID) (Solt, Citation2016). The SWIID combines information about income inequality from different published sources, such as the Luxembourg Income Study, and harmonizes these sources over time. It contains both gini measures of the market (before taxation and transfers) and disposable (after taxes and transfers) income inequality. For our analysis, we employ disposable income inequality, as it reflects inequality that people experience more closely than market inequality.Footnote4 While on average the disposible gini in our study rather stagnates (28.8 in 2002 and 29.6 in 2016), in some countries, like Spain or Denmark, income inequality has increased since 2002 (See Figure 5 SM). In our main analysis, we focus on the impact of one-year changes in the Gini indicator on the support for populist support. While studies have argued that long-turn changes are the dominant driver of radical-right support (Engler & Weisstanner, Citation2021; Pontusson & Weisstanner, Citation2018), our argumentation here is focused on evaluating the effect a different distribution of income would have on the mediators and support for populist parties. We return to the question of long-term effects as part of the robustness session.

Our theoretical discussion identifies four channels of how income inequality affects support for populist parties: economic insecurities, trust in political elites, social integration, and social (national) identity. The ESS includes a set of questions that map on these different attitudinal concepts. Economic insecurities is measured using one item: ‘Feeling about household’s income nowadays’. The variables is consistently included in the ESS study. In contrast to other studies in the field, we do not rely on an objective experience that trigger insecurities (see e.g., Hacker et al., Citation2014), but attitudinal reactions. Our measure is close to Inglehart and Norris (Citation2016) who rely on the same ESS question about difficulties to live on a household’s income.Footnote5 We measure trust in political institutions and elites based on three questions that focus on trust in the national parliament, political parties, and politicians.Footnote6 The measure creates a reliable scale of general trust in political elites.Footnote7 Social Integration is measured with three questions about social trust in people, implying that people with low social trust are rather socially marginalized.Footnote8 These set of questions tap into one dimension of social integration and are consistently available in all waves of the ESS.Footnote9 For social (national) identity we find two questions about immigration in the ESS. The first asks if a ‘country’s cultural life undermined or enriched by immigrants’ and the second focuses on multiculturalism in terms of immigration (‘Allow many/few immigrants of different race/ethnic group from the majority’). While this is arguably not a direct measure of national identity is likely to work as a reliable proxy of strong national identities (Blank & Schmidt, Citation2003). For the concepts with multiple indicators, we combine the survey questions using a one dimensional exploratory factor analysis and use the standardized factor scores as our measure.

Methods

We use the data to analyze the relationship between income inequality, the different mechanisms and vote for populist parties. Our theoretical argumentation splits the relationship into three separate paths that we intend to investigate in the following. First, income inequality should affect the support for populist parties. Second, income inequality affects the mediators, it could reduce trust in political elites, increase economic insecurities, socially marginalizes people and strengthen national identity. Third, the mediators should increase the propensity to support populists.

We work with multilevel models to take the nested data structure into account. For the main analysis, the independent variable is our measure of disposable income inequality that is linearly related to populist support. Country-specific factors, for example, different welfare state systems or cultural and historical norms, and common developments, like the financial crisis or general trends, play a central role as they potentially both influence income inequality and populist support. To consider these aspects we include random intercepts for both countries and the ESS waves. This does not, however, take into account factors on the macro level that varies over time. We, therefore, add a set of variables that potentially affect income inequality and populist support at the same time: Education expenditures, Unemployment Rate, Openness of the Economy, Social Security Transfers, and Union Density. Countries with a high union density, for example, probably have a more equal distribution of income (see e.g., Herzer, Citation2016) and unionist are less likely to support populist parties (Oesch, Citation2008), making this a relevant macro confounder. However, the controls should not be a clear consequence of income inequality to prevent post-treatment bias. We, for example, do not include economic growth as economist shows that inequality influences economic growth (see e.g., Banerjee & Duflo, Citation2003). We take the macro-control variables from the Comparative Political Data Set (CPDS).Footnote10

On the individual level, the theoretical discussions reveal two important variables: occupational groups and household income. In our conceptualization, these two aspects work as intermediate confounders, as they are influenced by income inequality, affect the mediators and influence support for populist parties. We refrain from controlling for them in the analysis where we study the effect of inequality (as this could induce post-treatment bias) but control for them when looking at the effects of the mediators on support for populist parties (where they are confounders). For occupational groups, we rely on the European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC) of 9 groups in the ESS. We further control for income as the standard deviation from the median income level within each country and year. An additional factor that could be an intermediate confounder is political preferences. Income inequality could drive people to become more extreme, which will make it more likely that they vote for populist parties, as their host ideologies are often found at the end of the political spectrum. We include left-right position of the respondent and the squared term in the analysis. We furthermore add a set of additional factors to all specifications that are potentially important composition factors for our comparative analyses, including sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, education in years, and religiosity. We estimate the models using design weights and weights for population size.

From the different model results, we can investigate if the different argumentation steps find empirical support. But can we also analyze if the enhancing effect of inequality on populist support is due to the mediators? Recent developments in causal mediation analysis make it clear this can be a tricky question to answer (Acharya et al., Citation2016; Imai et al., Citation2011). Footnote11 In our analysis, we turn to an alternative methodology to study mediation and focus on the controlled direct effects. This is the effect of inequality when taking the changes of the mediators into account (Acharya et al., Citation2016). Comparing the controlled direct effects to the direct effects we can infer about the role of the mediators. In case that we find that the controlled direct effect is significantly smaller compared to the total effect, we can conclude that part of the effect of inequality on support for populist parties can be attributed to the mediator. If the effect estimates are similar, the mediator does not block parts of the direct effect and thereby plays little to no role in explaining the relationship. We can estimate the average controlled direct effect using sequential g estimation (Acharya et al., Citation2016). The estimation of controlled direct effects requires a sequential unconfoundedness assumption for the different paths. In our application, this means that there are no omitted variables for the effect of income inequality on the outcome and no omitted variables for the effect of the mediators on the populist vote. We include the same control variables as in the analysis above. In case that this selection-on-observables approach fails the controlled direct effects can be biased just like the estimates above.Footnote12

Results

Main findings

We first investigate the direct effects of inequality on the support of populist parties and the mediators. reports on the estimates.Footnote13 We estimate that a one-unit increase in disposable income inequality increases the support for populist parties by around one percentage point (See first column ). This appears to be a rather subtle change, but if we consider the increases in some countries like Spain with 4 Gini points this makes this a factor to consider. Simulations based on the model show that an increase of the disposable Gini from 24 (5%-Quantile of observed Gini in our Sample) to 34 (95%-Quantile of observed Gini in our Sample) predicts an increase from 9% to 20% probability to support a populist party. Footnote14

Table 1. The effect of inequality support for populist parties. Results from European social survey.

further provides evidence that inequality is related to trust in political (third column) elites. The effect estimate can be interpreted in terms of standard deviations: A one-point increase in the Gini decreases the trust index by 0.072 standard deviations. This is a small effect, which we still estimate precisely enough to statistically reject the null hypothesis. A modest increase in income inequality results in medium erosions of political trust. Trust, hence, can have a mediation role when understanding the effect of income inequality on support for populist parties. The results further point out that inequality is related to economic insecurities. A one-point increase in the market Gini increases economic insecurities by 0.027 standard deviations. We further estimate a positive effect of inequality on social integration. The estimate is at odds with the expectations, according to which we would expect that inequality leads to stratification and lower integration. It puts doubt on the argumentation that social integration is a theoretical link between inequality and populism. We also find a positive association between inequality and national identity, making it a potential channel to consider.

As a next step, we analyze if the mediators also explain the support for populist parties. presents the model estimates and highlights that all concepts influence the support for populist parties as expected. Economic insecurities increase the support for populist parties, trust in political elites decreases the support, social integration decreases the support, and national identity positively affects the support. The effect is standardized and of different magnitude. E.g. one standard deviation higher trust in political elites decreases the support for populist by around 2 percentage points. National identity increases the support by 2 percentage points. This makes the effects quite substantial and confirms that the literature identifies reliable explanations for populist support on the micro-level.

Table 2. The effect of economic insecurity, trust in political elites, social integration, and social identity on the support for populist parties. Results from European social survey.

The combined finding that inequality affects trust in politics, economic insecurity, and national identity as expected and that the concepts also relate to populist vote choice makes them potential mediators for the effect of income inequality and support for populist parties. However, how relevant the factors are in explaining this relationship, can not be directly be read off from these two regression results.

Mediation analysis

Are the proposed channels relevant explanations for the effect of inequality on populist support? In this section, we aim to address the question by studying the controlled direct effect of inequality on populism holding the mediators constant. As discussed above, we use income deprivation, occupational groups and ideology as intermediate confounders. As mediators, we use the measures of economic insecurities, trust in political elites, social integration and national identity. We further include sociodemographic and macro controls in the estimation.

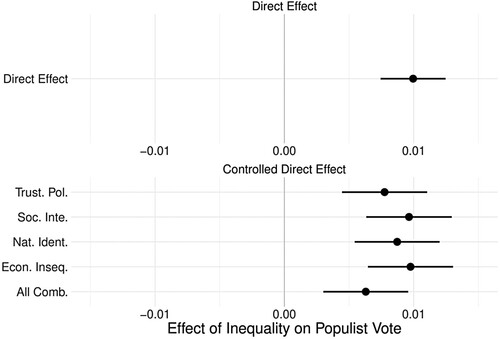

We do not find clear evidence that the theorized channels explain the influence of income inequality on populist support entirely. Trust in political elites is the only channel for which we find some indication that it can partially explain the association. shows the direct effect of inequality on populism and the controlled direct effect based on the different mediators. The effect estimates are almost identical when estimating the controlled direct effects for economic insecurities, national identity, and social integration. The effect decreases when controlling for trust (from 0.099 to 0.077), but given the uncertainty around the point estimates the change is not statistically significant. A similar decrease is observed when combining all attitudinal factors (to 0.063). Hence holding all theorized attitudinal aspects constant, we estimate a smaller effect of inequality on support for populist parties. But the sampling uncertainty can not rule out that these effects are identical. Overall, the channels do not explain the relationship sufficiently, which might be related to the weak relationship between income inequality and the mediators. Combining the two paths from the previous analysis is not sufficient to explain the overall effect.

Additional analysis

There are additional aspects we would like to evaluate before discussing the results in more detail. First, the theoretical discussion reveals that some of the mechanisms potentially work differently for left and right populist parties. In SM C.1, we estimate a positive effect of income inequality for right and left populist parties. The results also indicate that the mediators influence support for parties as expected, but we again do not find evidence that the mediators sufficiently explain the effect of income inequality for left- or right- populist parties.

Second, we analyze the role of occupational groups and income segments in more detail. Prior research found that the effects of income inequality are moderated by the occupational groups and income segments (Engler & Weisstanner, Citation2021; Han, Citation2016). While we are interested in explaining the average effect that inequality has on support for populists, it is certainly possible that different channels are at work for different parts of the population. The results we present in SM C.2 and C.3 highlight that the effect in our sample is strongest among the income segments in the middle half and relatively stable for different occupation groups. We still do not observe evidence of a clear mediation role of the different constructs.

Third, in the main analysis we evaluate the contemporaneous effects of income inequality, but it might be that only the long-term changes matter. In SM C.4, we report on the results that the long-term changes affect support for populist parties. This analysis shows some support of trust in political elites as a mediator for the support of populist parties.

Fourth, we evaluate some of the decisions we made for the analysis to probe the robustness of the results. We analyze the data using market income inequality instead of market income inequality (see SM C.5) and report on the results when using income inequality in the ESS year instead of the election year (see SM C.6). For both specifications, the results are comparable to the original results. We further re-estimate the model without the macro-level controls to consider potential sources of misspecification (see SM C.7) and when estimating effects based on respondents who report that they voted (see SM C.9). Finally, we study if the results change if we only include countries with populist parties and still find no clear mediation role of the different constructs (see SM C.8). The results are stable across these different specifications and deliver no sufficient mediation role of the central mechanism.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to explain how exactly increasing inequalities can lead to support for populist parties. We studied nine waves of the European Social Survey and found that especially trust in political elites are linked to populist support. However, causal mediation analysis showed that none of these mechanisms is sufficient to understand the impact of income inequality on support for populists. We find some indication that trust in political elites might work as a partial explanatory factor, making it a path that research could further explore to understand how increasing inequality can result in support for populist parties.

Our finding adds to the ongoing debate on what explains populist support. There is some scepticism in the literature if economic factors are a central driver of populism. Studies have pointed out that cultural aspects, shifts in values or immigration, might be more important to explain the surge of populist parties all over Europe (Margalit, Citation2019; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019). Our study focuses explicitly on understanding the mechanisms of one central economic factor: income inequality. In this, we also study ‘cultural’ mechanisms, such as social integration and nationalist appeals, that could be triggered by changes in allocation of income. This argument builds on the idea that even cultural mechanisms can have economic roots (see e.g., Carreras et al., Citation2019). But not finding clear support for the proposed mechanisms, puts doubt on this line of argumentation.

While our study is an important first step in identifying the mechanisms that link inequality and the rise of populist parties, there are important avenues for future research. First, we start with some research design considerations. Our research design is the first to evaluate the mechanisms linking inequality and populist support based on observational data from ESS. But it has a set of limitations that might impair the power to detect different channels. We suggest three aspects that might improve upon our empirical analysis. First, better measurements of the attitudinal factors could improve the analysis. More fine-grained measurement construct could help to reduce measurement error and increase the power to detect effects. Measurement error could also explain why the controlled direct effects are not reduced further. Second, the analysis relies on observable data. While we carefully outline how we believe the different aspects are connected and include the appropriate control variables, it might be that we missed relevant factors.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (265.8 KB)Acknowledgement

We want to thank Anselm Hager, participants of workshops at SCRIPTS, internal Humboldt University Seminar and three anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions and helpful feedback. We also thank Johannes Lattman and Violeta Haas for excellent research support. Research for this contribution is part of the Cluster of Excellence “Contestations of the Liberal Script†(EXC 2055, Project-ID: 390715649), funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lukas F. Stoetzer

Lukas F. Stoetzer is Post-Doc at the SCRIPTS Cluster of excellence of the Humboldt University of Berlin. His research focuses on comparative political behaviour and political methodology.

Johannes Giesecke

Johannes Giesecke is Professor of Empirical Social Research at Humboldt University of Berlin. His research focuses on sociology of labor markets, social inequality, and methods of empirical social research.

Heike Klüver

Heike Klüver is Comparative Political Behavior at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her research interests include comparative european politics, political parties, coalition governments, interest groups, political representation as well as quantitative text analysis

Notes

1 The condensation of four separate mechanisms is made for the sake of the argumentation. Most of the papers in this section speak about multiple mechanisms that can be related to each other.

2 The countries in our study are: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom. We exclude East-European countries as the structural relationship between inequality, representation, and rise of populist parties is characterized by transitions to the market economy and difficult to compare to West-European countries.

3 We present the parties in our sample that are classified as populist in the supplementary materials (SM).

4 As a robustness check the SM reports on the effects of market inequality.

5 Other studies rely on responses to a specific question about job security (see e.g. Scheve & Slaughter, Citation2004).

6 The questions are asked on an 11-pt scale. The wording reads "how much you personally trust each of the institutions I read out".

7 The trust measure in political elites is conceptually and empirically different from populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Geurkink et al., Citation2020).

8 The questions are asked on an 11-pt scale. The wording reads "Most people can be trusted or you can’t be too careful", "most people try to take advantage of you, or try to be fair", "Most of the time people helpful or mostly looking out for themselves".

9 For testing their argument Gidron and Hall (Citation2020) rely on a different question that asks respondents about subjective social status. The measure is only available in one wave of the ESS, but it correlates positively with our measure "trust in people". Gidron and Hall (Citation2020) also describe "trust in people" as one measurement indicator for social integration.

10 For a more detailed description of the variables please refer to the SM. For the control variables, we interpolate missing country years using splines.

11 While we would prefer to explain how much of the total effect of inequality is due to changes in the mediators (Imai et al., Citation2011), making such inferences would require a strong assumption that there are no intermediate confounders. In our context those exist: Inequality potentially affects the distribution of income and social class, which have both an effect on the mediators and support for populism. Even if we observe those intermediate confounder we cannot address the issue and meet the required assumptions (Acharya et al., Citation2016). Moreover, the different channels might influence each other. E.g. economic insecurities might reduce trust in political elites. This could create an additional confounder structures that a classic mediation analysis would need to consider.

12 We rely on the R-package DirectEffects to carry out the estimation.

13 For a table with all estimates please refer to SM B.2

14 We predict values varying the main covariate, income inequality, and trust in political elites, and hold the other covariates at mean values in our sample.

References

- Acharya, A., Blackwell, M., & Sen, M. (2016). Explaining causal findings without bias: Detecting and assessing direct effects. American Political Science Review, 110(3), 512–529. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000216

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2003). Inequality and growth: What can the data say? Journal of Economic Growth, 8(3), 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026205114860

- Betz, H. (1994). Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. Springer.

- Blank, B., & Schmidt, T. (2003). National identity in a united Germany: Nationalism or patriotism? An empirical test with representative data. Political Psychology, 24(2), 289–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00329

- Bornschier, S., & Kriesi, H. (2012). The populist right, the working class, and the changing face of class politics. In J. Rydgren (Ed.), Class Politics and the Radical Right (pp. 28–48). Routledge.

- Carreras, M., Irepoglu Carreras, Y., & Bowler, S. (2019). Long-term economic distress, cultural backlash, and support for brexit. Comparative Political Studies, 52(9), 1396–1424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019830714

- Coffé, H., Heyndels, B., & Vermeir, J. (2007). Fertile grounds for extreme right-wing parties: Explaining the vlaams blok’s electoral success. Electoral Studies, 26(1), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2006.01.005

- Engler, S., & Weisstanner, D. (2021). The threat of social decline: Income inequality and radical right support. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1733636

- Geurkink, B., Zaslove, A., Sluiter, R., & Jacobs, K. (2020). Populist attitudes, political trust, and external political efficacy: Old wine in new bottles? Political Studies, 68(1), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719842768

- Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. The British Journal of Sociology, 68(S1), 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12319

- Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2020). Populism as a problem of social integration. Comparative Political Studies, 53(7), 1027–1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019879947

- Hacker, J. S., Huber, G. A., Nichols, A., Rehm, P., Schlesinger, M., Valletta, R., & Craig, S. (2014). The economic security index: A new measure for research and policy analysis. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(S1), S5–S32. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12053

- Han, K. J. (2016). Income inequality and voting for radical right-wing parties. Electoral Studies, 42, 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.02.001

- Herzer, D. (2016). Unions and income inequality: A heterogeneous panel co-integration and causality analysis. Labour, 30(3), 318–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/labr.12075

- Imai, K., Keele, L., Tingley, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2011). Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. American Political Science Review, 105(4), 765–789. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055411000414

- Inglehart, R. F., & Norris, P. (2016). Trump, brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. HKS Woking Paper No. RWP16-026.

- Jesuit, D. K., Paradowski, P. R., & Mahler, V. A. (2009). Electoral support for extreme right-wing parties: A sub-national analysis of Western European elections. Electoral Studies, 28(2), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2009.01.009

- Kriesi, H. (2014). The populist challenge. West European Politics, 37(2), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887879

- Kurer, T. (2020). The declining middle: Occupational change, social status, and the populist right. Comparative Political Studies, 53(10-11), 1798–1835. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020912283

- Lipps, J., & Schraff, D. (2020). Regional inequality and institutional trust in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, First View(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12430

- Loew, N., & Faas, T. (2019). Between thin-and host-ideologies: How populist attitudes interact with policy preferences in shaping voting behaviour. Representation, 55(4), 493–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2019.1643772

- March, L., & Mudde, C. (2005). What’s left of the radical left? The european radical left after 1989: Decline and mutation. Comparative European Politics, 3(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110052

- Margalit, Y. (2019). Economic insecurity and the causes of populism, reconsidered. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.152

- Moene, K. O., & Wallerstein, M. (2001). Inequality, social insurance, and redistribution. American Political Science Review, 95(4), 859–874. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400400067

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge University Press.

- Oesch, D. (2008). ‘Explaining workers’ support for right-wing populist parties in Western Europe: Evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland. International Political Science Review, 29(3), 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512107088390

- Pontusson, J., & Weisstanner, D. (2018). Macroeconomic conditions, inequality shocks and the politics of redistribution, 1990–2013. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310280

- Ramiro, L., & Gomez, R. (2017). Radical-left populism during the great recession: Podemos and its competition with the established radical left. Political Studies, 65(1S), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716647400

- Rehm, P. (2016). Risk Inequality and Welfare States: Social Policy Preferences, Development, and Dynamics. Cambridge University Press.

- Rooduijn, M. (2018). What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties. European Political Science Review, 10(3), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773917000145

- Rooduijn, M., & Akkerman, T. (2017). Flank attacks: Populism and left-right radicalism in Western Europe. Party Politics, 23(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815596514

- Rooduijn, M., Van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., De Lange, S., Halikiopoulou, D., Lewis, P., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2019). The populist: An overview of populist, far right, far left and eurosceptic parties in europe.

- Runciman, W. G., & Baron, R. (1966). Relative Deprivation and Social Justice: A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England. University of California Press.

- Scheve, K., & Slaughter, M. J. (2004). Economic insecurity and the globalization of production. American Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 662–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00094.x

- Shayo, M. (2009). A model of social identity with an application to political economy: Nation, class, and redistribution. American Political Science Review, 103(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409090194

- Solt, F. (2016). The standardized world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly, 97(5), 1267–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12295

- Spoon, J., & Klüver, H. (2019). Party convergence and vote switching: Explaining mainstream party decline across Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 58(4), 1021–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12331