ABSTRACT

Organising effective policy coordination has become a key principle of EU policymaking in recent decades. Within the European Commission, interservice consultations (ISCs) play an important role to coordinate between the different directorate-generals. In spite of this importance, ISCs have so far not been analysed in a systematic way. This paper addresses this gap by systematically analysing the numbers, types and content of comments made in ISCs around climate change adaptation. Our analysis shows that ISCs were primarily used to provide substantive comments, related to problem analyses, objectives or instruments, as well as to strengthen or weaken connections with policy efforts in adjacent domains. Institutional comments, related to mandates or resources, proved rare. Moreover, we find that the types of comments given in ISCs are mediated by institutional factors that shape the temporal dynamics of policy processes. Rather than reflecting the ideal types of ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ coordination, the overall pattern of policy coordination in the ISCs typifies an in-between form of ‘incremental policy coordination.’

Introduction

Due to the increased complexity of many of today’s societal problems, organising effective policy coordination has become a key challenge to policymakers across the globe. Coordination is particularly needed for issues that are affected by policy efforts that originate from across different compartmentalised policy domains. In these cases, some form of coordination is needed to make sure the efforts under one policy programme do not cancel out the efforts under another policy programme (‘negative coordination’), or, more ambitiously, to create synergies between policies (‘positive coordination’) (Scharpf, Citation1994).

In the context of the European Union (EU), policy coordination and policy coherence have become subject to a distinct body of literature (Candel & Biesbroek, Citation2018; Egenhofer et al., Citation2006; Hartlapp et al., Citation2014; Hustedt & Seyfried, Citation2016; Kassim et al., Citation2017; Selianko & Lenschow, Citation2015; Stroß, Citation2017; Trondal, Citation2011). Because of its central role in policy formation, these studies usually focus on coordination processes within the European Commission. This literature has used a range of sources to study coordination, predominantly interviews. Few studies have looked at the formal stage of coordination within the Commission: the interservice consultation (ISC).

The ISC is a formalised procedure in which a Directorate General (DG) that is in charge of developing a given Commission proposal (the ‘lead DG’) receives input from other DGs. Because of its set-up as a consultation process between DGs, the ISC is a central arrangement for the formal coordination of policies that affect multiple DGs. Although informal and formal forms of exchange occur both before and after ISCs, the latter play a pivotal role within this entire process, as they focus on concrete draft proposals and allow interested DGs to give specific, written input. ISCs therefore offer an excellent opportunity to study coordination within the Commission. To date, however, the input given in ISCs has not been analysed in a systematic way and both the type and substance of policy coordination within ISCs largely remain unexplored (although some studies have used it as supportive evidence; see e.g., Hartlapp et al., Citation2014).

This paper aims to identify the patterns of positive and negative coordination within the Commission, specifically looking at the different types of coordination processes, and how these patterns of coordination may have shifted over time. Moreover, we aim to explore the potential of using the internal documents produced during ISCs as a new data source for studying coordination within the Commission. In doing so, our paper seeks to develop and apply a systematic approach to analysing the comments in ISCs. This creates possibilities for future studies into the policy formation process within the Commission, alongside existing approaches such as interviews and surveys.

Empirically, we use the documents submitted by DGs in four ISCs around climate change adaptation policy, as well as supportive evidence from qualitative interviews, to map the types of comments given and what they reveal about patterns of coordination in the Commission. Climate change adaptation offers a useful case for such an analysis because of its crosscutting nature and increasing social and political attention in Europe. Climate change adaptation revolves around the actions to manage the impact of climate change, reduce vulnerability or enhance adaptive capacity (IPCC, Citation2018). As such, it complements efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (climate mitigation). Climate change adaptation is a crosscutting issue in that it concerns a range of societal and economic activities and policies, including agriculture, biodiversity, human health, and water management. The Commission can only rely on soft legislation to steer climate change adaptation actions, which requires the mainstreaming of climate change adaptation objectives into domains where the EU has a stronger competence (Biesbroek & Swart, Citation2019).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we outline our theoretical framework for studying policy coordination in the European Commission. In section 3 we concisely set out the development of EU climate change adaptation policy over time. In section 4, we present our systematic approach to analysing the ISCs around climate change adaptation policy, followed by the results of our empirical analysis in section 5. The paper ends with a concluding section, in which we discuss the main findings, identify the implications from our analysis, and propose pathways forwards.

Understanding patterns of coordination in ISCs

Fragmentation and coordination in the European Commission

In the academic literature on the internal working of the European Commission, the Commission is often portrayed as a relatively fragmented institution, in which DGs mainly work in isolated ‘silos’ and are eager to protect their turf against other DGs (Hartlapp et al., Citation2014; Kassim, Citation2018; Stroß, Citation2017). Over the past 10–15 years, several scholars have noted a tendency towards greater central coordination, in particular through the stronger and more active roles of the Commission President, Vice-Presidents and the Secretariat General (SG) (Jordan and Schout, Citation2006; Kassim, Citation2018; Kassim et al., Citation2017). Trondal (Citation2011) observes a dual logic in this regard: whereas a ‘logic of hierarchy’, which relies on top-down coordination, has taken hold at the top of the Commission, individual DGs still largely operate along the lines of a ‘logic of portfolio’, which emphasises divergent agendas and loyalty to DGs rather than the Commission as a whole.

Within this context, ISCs are meant to function as a means of policy coordination among the various DGs. An ISC is a formalised procedure in which the DG that is in charge of developing a given Commission proposal (the ‘lead DG’) receives input from other interested DGs (Nugent & Rhinard, Citation2015). Although the formal requirements for ISCs (e.g., which other DGs need to be consulted) have been strengthened in recent decades, the lead DG still has some leeway in determining the precise set-up of the ISC (Hartlapp et al., Citation2014; Nugent & Rhinard, Citation2015).

ISCs are not the only coordination mechanism in place within the Commission. Preceding a formal ISC, DGs often engage in informal exchanges of viewpoints, which may affect the content of proposed policies (Nugent & Rhinard, Citation2015). Moreover, for many issues, permanent Interservice Groups exist, which bring together officials from different DGs on a regular basis (Hartlapp et al., Citation2014). In addition, after an ISC has taken place, draft proposals are discussed among the cabinets of commissioners and eventually in the College of Commissioners. Within this entire process, however, ISCs play a pivotal role, as they focus on concrete draft proposals and allow interested DGs to give specific, written input.

Observers differ in their assessment of the impact ISCs have on policy coordination. On the positive side, Candel et al. (Citation2016) claim that ISCs lead to greater reflexivity and compromise on the part of DGs, because they ‘stimulate approaching issues from various perspectives and thus enhance mutual understandings’ (Ibid., p. 798) and ‘forc[e] units [and] services to reach agreements’ (Ibid., p. 804). By contrast, Hustedt and Seyfried (Citation2016) argue that coordination within the Commission is characterised by ‘negative coordination’, a term they borrow from Fritz Scharpf (Citation1994). Under negative coordination, ‘the formal responsible organisational unit initiates the co-ordination process by providing a draft, which is sent to the other affected units for comments and amendments. Those affected units check the draft exclusively for the negative effects on their own area of competence’ (Hustedt & Seyfried, Citation2016, p. 892; references omitted). The central purpose of negative coordination, so Scharpf (Citation1994, p. 39) explains, is ‘to ensure that any new policy initiative designed by a specialised subunit within the ministerial organisation will not interfere with the established policies and the interests of other ministerial units.’ This stands in contrast to positive coordination, which ‘is an attempt to maximise the overall effectiveness and efficiency of government policy by exploring and utilising the joint strategy options of several ministerial portfolios’ (Scharpf, Citation1994, p. 38). According to Hustedt and Seyfried (Citation2016, p. 892), this implies that ‘all affected units are involved from the very beginning by discussing all policy alternatives jointly across all actors, and the effects of all alternatives are simultaneously checked for all affected units.’

Types of issues in coordination processes within the European Commission

Coordination is meant to align DGs that (potentially) differ on a Commission policy initiative. Two main types of issues may come up in this regard: institutional and substantive issues (cf. the typology of conflicts within the Commission in Nugent & Rhinard, Citation2015).

Institutional issues concern the scope of DGs’ responsibilities. Institutional issues may emerge when a DG attempts to acquire additional tasks and leadership within policy areas (Stevens & Stevens, Citation2001). Other DGs may then challenge that DG’s remit over these issues, as well as its claim over the resources associated with the new task. This type of issue is particularly likely to come up when it concerns ‘high profile areas which bring increased influence or prestige’ (Ibid.). Institutional issues are even more likely to arise when these high-profile areas concern relatively new issues, which potentially affect multiple DGs – as in the case of climate change adaptation.

Substantive issues relate to the range of possible framings and associated policy approaches surrounding a policy issue (Dupuis & Biesbroek, Citation2013). Because DGs have different remits and responsibilities, are part of different policy communities and (therefore) also attract people with different types of backgrounds, considerable differences may exist between DGs over problem definitions, objectives to be prioritised and the instruments to be used in a domain. To the extent that these substantive approaches are affected or challenged by an initiative from another DG, they may trigger calls for reformulating that initiative.

Explaining patterns of coordination: stakes and policy cycles

The existence of (potential) institutional and substantive issues may be a reason for a DG to give input into another DG’s policy initiative. However, whether or not a DG decides to participate in an ISC and to give comments also depends on whether it is willing (or feels pressed) to become active. In this way, latent sources of participation are turned into actual patterns of coordination. Arguably, several types of institutional dynamics shape this participation.

First, one may expect that the stakes in a given policy proposal are important. These stakes are not only determined by the content of the proposal, but also by the status of the proposal within the entire policy-making process. For instance, it may be assumed that more is at stake in a proposal for binding legislation (a directive or regulation) than in a Green Paper or other document that merely explores an issue. Although it is important for actors to be involved from the beginning, when initial decisions are made, such initial decisions are less likely to trigger concrete interests than proposals for more specific and potentially binding decisions. This means that one may expect, first, participation in ISCs to increase and, second, conflicts to become more pronounced, as the stakes in the proposal rise (cf. Stokman et al., Citation2000). Stakes can also be affected by the perceived urgency or the political salience of an issue. When an issue is perceived to be more pressing and becomes subject to ‘high politics’ between political leaders, this is likely to raise attention and stakes at lower levels of decision-making (Princen & Rhinard, Citation2006). In a recent study, Senninger et al. (Citation2020) found that leading civil servants in the Commission indeed use highly salient policies to boost their DG’s profile.

Second, coordination dynamics may change over time, as a policy matures. Partly, this overlaps with the previous factor, as the stakes in the policy process increase as the policy develops from initial idea to concrete proposals. However, the maturation of policies may partly also have an effect independent from what is at stake in a specific proposal. The policy studies literature has identified a pattern in which policies tend to crystallize and become more firmly established after their initial creation, only to be disrupted at specific moments of more fundamental debate (Baumgartner & Jones, Citation1993; Sabatier, Citation1998). Institutionally, this pattern is underpinned by the fact that established policies are usually monopolised by (relatively closed) policy communities, in which actors agree on the basic policy approach and attention focuses on the specifics of policies. Therefore, we may expect policy development around EU climate change adaptation policy to undergo a gradual development from initial exploration of the issue to the development of specific policies.

This line of argument has two implications. To begin with, one may expect issues of authority and remit to become clearer over time. Whereas in the initial stages, the authority of the lead DG to deal with a new issue may be contested (particularly when that issue affects other, already established issue areas), this authority is likely to become more firmly established as the lead DG becomes a more credible participant on the issue. In that case, the focus in ISCs should move from institutional to substantive issues. In addition, with the maturation of a policy, discussions are likely to focus more on the specifics of that policy. Whereas initially, it needs to be established what the nature of the issue is and what objectives should be formulated, as time progresses one may expect debates to shift from a focus on policy objectives to the specific instruments that are being used and their calibrations (cf. Hall, Citation1993).

Third, the timing of a policy proposal in relation to other policy cycles may affect the patterns of coordination that occur. Developments in other policy cycles may highlight certain issues, while suppressing others. Moreover, when choices made in the policy proposal under discussion affect choices made elsewhere, the timing of decision-making may either block or facilitate those choices. This point ties in with the recent literature on the role of time and timing in (EU) policy processes. This literature has shown that policy (as well as political) processes are deeply influenced by the way they are temporally organised through formal and informal rules on what can or should be done when. Within the Commission, this is exemplified by its institutionalised planning and programming cycle for the definition of policy priorities on an annual basis (Tholoniat, Citation2009) as well as the multi-annual financial frameworks. However, policy domains also have institutionalised multiannual time cycles. Examples of these include the adoption of multi-annual Environmental Action Programmes, Framework Programmes for Research, and the evaluation or revision of policies at set points in time.

These cycles do not run in parallel. As Goetz (Citation2009, p. 203) has observed, in the Commission ‘different policy fields are characterised by (…) distinct temporal frameworks’. As a result, policy processes in the European Commission are not subject to one overarching timeframe, but show ‘temporal plurality’ (Ibid., p. 206), making the Commission a ‘heterotemporal organisation’ (Goetz, Citation2014). This is complicated even further by the timing of policy cycles outside of the Commission and the EU, for instance in the series of global negotiations following the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Within these overlapping and interacting policy cycles, some actors may act as ‘time-setters’, who can influence the timing of certain decision, while others are ‘time-takers’, who are constrained by the time frameworks set elsewhere (Goetz, Citation2014). Particularly in an issue area such as climate change adaptation, which relies heavily on policies adopted in other, longer-established issue areas, we may expect the temporal decisions taken elsewhere to have a clear effect. As a consequence, the dynamics of climate change adaptation policy coordination is likely to be strongly affected by the timing of other, related policy cycles. Budgetary cycles are particularly influential in this respect, as these more or less set in stone the budgetary allocations to a domain for a certain period of time and therefore hamper possibilities for intermediate reforms. In addition, the tedious and long-lasting European Council negotiations on the multi-annual financial frameworks have been shown to cause delays and decreased ambition levels in sectoral policy reforms, such as that of the Common Agricultural Policy (Candel, Citation2019).

Fourth, coordination dynamics may change as a result of institutional reform. In a recent study, Finke (Citation2019) showed that considerable competition over administrative turf takes place within the Commission. The creation of new services, such as DG CLIMA (out of DG Environment) and the European External Action Service (EEAS) in 2010, generally involves a reshuffling of such turf, including mandates and resources. As DGs that ‘lose out’ in such reforms may experience their core competences to be at stake, we expect that reforms increase the likelihood of institutional conflict in ISCs.

In summary, the literature yields a range of possible expectations regarding coordination dynamics in ISCs. These theoretical expectations are summarised in .

Table 1. Theoretical expectations.

Climate change adaptation policy at EU-level

The EU has for a long time played a leadership role in international negotiations on climate change mitigation (i.e., reducing greenhouse gas emissions), but arrived relatively late in discussions on climate change adaptation (Biesbroek & Swart, Citation2019). Climate change adaptation refers to the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects in order to moderate harm or exploit opportunities (IPCC, Citation2014). Adaptation has been on the European Commission’s radar since the early 2000s, when the Second European Climate Change programme reported on the potential impacts of climate change on the ambitions formulated in the EU’s Lisbon Strategy. Its Communication ‘Winning the battle against Climate Change’ marked a key moment, as it explicitly called for improved adaptation across the EU (COM(2005)35 final). Until then, the Commission had largely avoided references to adaptation, out of fear that this would give the impression that mitigation policies had failed.

The attention to adaptation was partly driven by the growing scientific consensus that, even with strict emission reductions, some climate impacts would be unavoidable (IPCC, Citation2020). Several impacts that were observed, such as the 2003 heat wave in most of Europe, raised climate change on the political agenda (EEA, Citation2017). DG Environment started an EU-wide public debate and consultation through its Green Paper (COM/2007/0354 final) in 2007 to identify priority areas and options, including intensifying climate research, mainstreaming adaptation across existing EU external actions, and exploring the role of Community funds.

The first EU policy ambitions were formulated in the EU White Paper (COM(2009)147 final), in which the contours of an EU-wide adaptation framework were proposed. The strategy aimed to improve the EU’s resilience to deal with the impacts of climate change, recognising that most of the adaptation actions would have to take place at national and local levels. Following the principle of subsidiarity, the EU envisioned its role as supporting and empowering member states through an integrated and coordinated approach at EU level.

Shortly after the White Paper was launched, a new DG, DG CLIMA, was established (2010), which led the development of the EU Adaptation Strategy Package (COM (2013) 216). Adopted in 2013, the EU strategy centred around three objectives: strengthening responses of member states, ‘climate proofing’ policy efforts at EU level, and better-informed decision making. The package contained multiple impact assessments and sectoral guidance documents to support the strategy. The strategy emphasised the facilitative role of the Commission, noting its limited set of tools to formulate new legislation, and stressed the importance of mainstreaming adaptation into areas in which the EU has formal competences.

With the adoption of the Paris Agreement (2015), and further evidence on increased climate impacts across Europe, climate change adaptation in the Commission continued to grow in importance. The period after the adoption of the strategy was important for adaptation as several actions were implemented at EU-level, including information portals such as Climate Adapt, innovative financing schemes such as the Natural Capital Funding Facility, and new collaborative networks such as the Mayors Adapt initiative. Five years after the strategy was adopted, a formal evaluation showed the strategy had played an important role in mobilising adaptation responses within Europe. Still, it also argued that additional efforts were needed to strengthen Europe’s internal and external responses to climate impacts and to strengthen links with sustainable development and disaster risk reduction (COM(2018)738).

The current Von der Leyen Commission (2019-) has further raised the ambitions, resulting in various new policy developments. For example, the new European Green Deal includes a proposal for a European Climate Law (COM/2020/80 final) which focusses primarily on emission reduction, but also captures adaptation in Article 4 to ensure that member states ‘develop and implement adaptation strategies and plans that include comprehensive risk management frameworks, based on robust climate and vulnerability baselines and progress assessments’. Moreover, ‘Adaptation to climate change including societal transformation’ is one of the five Mission Areas in the EU’s research and innovation framework programme ‘Horizon Europe’. The European Climate Pact aims to promote broad social mobilisation to reduce climate change impacts beyond governmental responses. Finally, the Commission developed a new, more comprehensive European Climate Change adaptation strategy which was published in early 2021 (COM(2021) 82 final).

Studying coordination in ISCs on climate change adaptation

To identify patterns of coordination in ISCs, we developed a systematic approach to analyse the type and substance of the comments given by DGs which participated in four ISCs on EU climate change adaptation policies. All documents related to these ISCs were obtained through an official request to Commission documents (on the basis of Regulation 1049/201). These documents were subsequently coded using a standardised coding scheme. In addition, we conducted five interviews with key participants in the ISCs around climate change adaptation policy to interpret and verify our results. Below, we will discuss these steps in greater detail.

Operationalisation and codebook

In order to map patterns of negative and positive coordination in ISCs, a coding scheme was developed that distinguishes between various types of comments. The two main categories in the coding scheme build on the two types of issues that were discussed above. For the purposes of our coding scheme, these types needed to be operationalised more precisely, as it is more difficult to discern them empirically than conceptually.

Within the two main categories of comments relating to substantive and institutional issues, further distinctions can be made. First, substantive comments may focus on various elements of the proposed policy, relating to problem definitions, objectives, the choice of instruments or the specification/calibration of those instruments (for the latter three categories, see Hall, Citation1993). Second, institutional and substantive comments may support a policy proposal, criticise it or be neutral. If a comment is critical of a proposal, a further question is whether the comment seeks to expand or limit the position taken in the document. This ties in with Knill et al.’s (Citation2012) distinction between ‘expansion’ (i.e., expanding the proposal by making it more ambitious or broader, by including more and stricter or more generous instruments, or explicitly calling for the integration of objectives or instruments in different policy programmes) and ‘dismantling’ (i.e., limiting the proposal, for example by relaxing ambitions, narrowing objectives or limiting the scope or ambit of instruments, with ‘dismantling’ being the extreme version of this).

Based on these distinctions, we defined a range of codes to capture different types of institutional and substantive comments. In addition to the two main categories of institutional and substantive issues, we defined codes for comments that urged the lead DG to include, take out or clarify references to existing policy initiatives. Finally, we included codes for comments that contained a more general endorsement or rejection of the proposal or the procedure taken in relation to the document. The online supplementary material provides an overview of our codebook.

Organisation of coding

All three authors were involved in two rounds of test coding, which included three and four documents from various ISCs, respectively. Based on these rounds, the coding scheme was modified and a common interpretation of each code was established. After that, the lead author coded all documents in all ISCs, with the exception of comments that raised doubts as to the correct code. These ‘hard’ cases were discussed and resolved between the three authors.

Cases and documents

The analysis focuses on the ISCs about proposals for four key documents in the development of the EU’s climate change adaptation policy: the Green Paper ‘Adapting to climate change in Europe’ (COM2007 354), which aimed to stimulate discussions on the need for EU level action on climate change adaptation; the White Paper ‘Adapting to climate change: Towards a European framework for action’ (COM2009 147), which presents the outline for a European wide framework to reduce the EU’s vulnerability to the impacts of climate change; the Communication ‘An EU Strategy on adaptation to climate change’ (COM2013 216), which presents how the EU will promote actions by Member States, their efforts of climate proofing EU actions, and stimulate better informed decision making; and the Report ‘on the implementation of the EU Strategy on adaptation to climate change’ (COM2018 738), which evaluates the progress in achieving these objectives (Biesbroek & Swart, Citation2019; Dreyfus & Patt, Citation2012; Remling, Citation2018). The Commission’s new strategy (2021) was published after data collection and analysis had taken place and is not included in the current study.

Each ISC contains various types of documents: i) the draft proposal and accompanying documents, such as draft staff working documents or documents related to the impact assessment, ii) DGs’ opinion letters in which they indicate whether they are supportive of the proposal, and iii) the proposal and accompanying documents with individual DGs’ track changes (see the online appendix for a full overview of documents). There is a large variety between DGs, or even individual officers, in what types of documents they submit to the ISC and how they structure their remarks. For example, some DGs include most of their comments in the opinion letter, while others provide detailed track changes in the proposal. Comments entail remarks relating to the status of the document or procedure, a text block, or the insertion or deletion of a word, phrase, sentence, bullet point or paragraph.

Interviews

After coding and analysing the documents, we conducted five interviews with (former) Commission officials from various DGs who had been involved in the ISCs around climate change adaptation. These interviews provided further background and context to our findings and allowed us to better put our findings into perspective. The interviews were semi-structured, generally took 60 min, and were all recorded with consent of the interviewees. The main topics discussed included: their own experience with coordination in the Commission around climate change adaptation; reflection on our findings; and specific clarifying questions emerging from our initial round of data analysis.

Results

General patterns

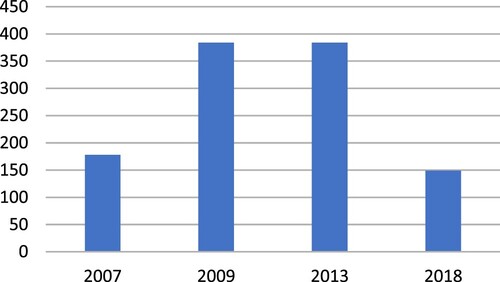

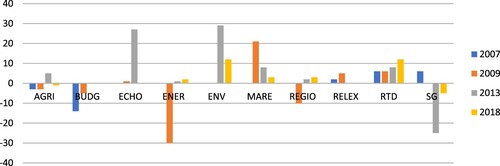

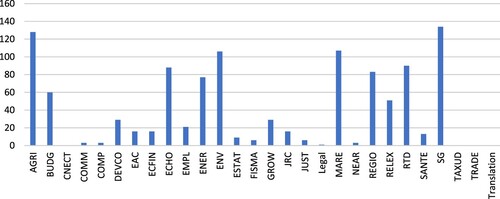

Our results show that the numbers of comments made differ between the four ISCs. shows the total numbers of comments made during each of the interservice consultation rounds. The figure shows that in 2009 and 2013 the proposals received more than double the number of comments compared to the 2007 and 2018 ISC rounds.

When looking at the total numbers of comments per DG, major differences can be observed between services (see ). As with total numbers, these frequencies provide some indication of DGs’ activity, but should be treated with caution due to differences in ISC response styles. Moreover, as is shown in the online appendix, considerable differences can be observed across years. With the exception of the SG and DGs AGRI, RTD and REGIO, most DGs’ comments show clear peaks in one or two of the ISC rounds. DG ENVI’s comments are limited to 2013 and 2018, since DG ENVI was the lead DG until 2010. Similarly, the DG for External Relations (RELEX) only gave inputs in 2007 and 2009, as it lost its climate mandate to the new DG for Climate Action (CLIMA) in 2010 and was embedded in the European External Action Service (EEAS), which is not involved in Commission ISCs ().

Figure 2. Total number of comments per DG for all ISCs. DGs Taxud, Trade and Translation gave their approval without substantive comments.

Based on these data we can distinguish between three groups of DGs in terms of participation: (i) persistent players, which were significantly active in (almost) every ISC (AGRI, MARE, REGIO, RTD, SG); (ii) occasional players, which were active in one or two ISCs (BUDG, DEV, EAC, ECHO, EMPL, ENER/TREN, GROW, RELEX) and (iii) background players, which only offered a few comments in one or more ISCs. Respondents indicated that the SG is a persistent player in every ISC, due to its formal mandate to coordinate policy initiatives across sectors. One respondent, for example, stated:

The SG is the watchdog of the Commission, they need to keep the equilibrium. So normally they are quite tough in their comments, because they make very procedural and institutional kinds of comments.

Effects of stakes in the proposal

The first set of explanatory factors concerned the stakes in a proposal. As the stakes in a proposal rise, both participation and conflict were expected to increase. In terms of participation, we find mixed evidence. On the one hand, the number of DGs participating in the ISCs declined from 23 in 2007–19 in 2009, 17 in 2003 and 13 in 2018. This is contrary to what one would expect given the higher political weight of the 2013 Strategy vis-à-vis the 2007 Green Paper (and also the growth of the overall number of Commission DGs). On the other hand, as above showed, the numbers of comments were greatest for the two ISCs in which arguably most was at stake (the 2009 ISC on the White Paper and the 2013 ISC on the Strategy). The two ISCs in which least was at stake (the 2007 ISC on the Green Paper and the 2018 ISC on the evaluation of the Strategy) drew about half as many comments. At the same time, based on this logic, one would perhaps have expected higher numbers of comments in the 2013 than in the 2009 ISC, whereas both attracted exactly the same number of comments.

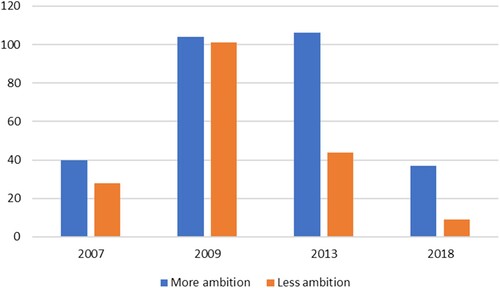

We obtain a proxy for the level of conflict by focusing at comments that ask for more and less ambition, respectively. More ambition is indicated by comments asking for making problem definitions broader or more severe, objectives more ambitious, adding instruments, or increasing the intensity of instruments. Less ambition is indicated by their negative counterparts. Overall, comments asking for more ambition (287) are more frequent than comments asking for a lower ambition (182), although in the ISC of 2009 numbers are almost equal (104 more ambition, 101 less).

shows the numbers of comments calling for more and less ambition in each ISC. The data show clear peaks in calls for more ambition in 2009 and 2013. Calls for less ambition were voiced most often in 2009. Combining the two categories, the 2009 ISC clearly stands out with 205 comments asking for a different level of ambition. The 2013 ISC comes in second with 150 comments, while the 2007 and 2018 ISCs score considerably lower at 68 and 46 comments, respectively. Percentage-wise, the 2009 ISC also stands out, with 53% of all comments asking for a different level of ambition. The 2013 ISC comes in second with 39%, but is closely followed by the 2007 ISC with a combined total of 38%. In the 2018 ISC, only 31% of all comments called for a different level of ambition.

The peaks in comments calling for a different level of ambition in 2009 and 2013 suggest a relation between increasing stakes and levels of conflict, although the lower number of comments asking for less ambition in 2013 does not conform to our expectation. From a qualitative angle, respondents indicated that there was considerable debate about the level of ambition in the 2013 Strategy. One respondent indicated that the SG ‘sometimes pushed us to be more down to earth’, as a too ambitious policy would imply considerable commitments at international level and for member states. Additionally, various respondents indicated that in the period before the 2015 Paris Agreement, investments in adaptation were considered to result in trade-offs with resources available for climate change mitigation, which received priority. The low numbers in the 2018 evaluation, in which the stakes were arguably lower than in the previous two ISCs, support the notion that the level of conflict is at least partly driven by the stakes involved in the ISC.

Based on our current data it is difficult to distinguish between the influence of increasing stakes following from the status of the proposal or from broader political and societal salience, which also increased over the period of analysis (see e.g., Ovádek et al., Citation2020 on EU issue attention). Still, the relatively lower level of conflict in the (relatively less consequential) 2018 ISC suggests that the stakes in a proposal do play a role in their own right.

Effects of policy maturation

The second set of explanatory factors was related to the possible effects of policy maturation. As a policy matures, one may expect the emphasis to shift from institutional to substantive comments and, within the category of substantive comments, from objectives and underlying problem definitions to policy instruments and their calibration.

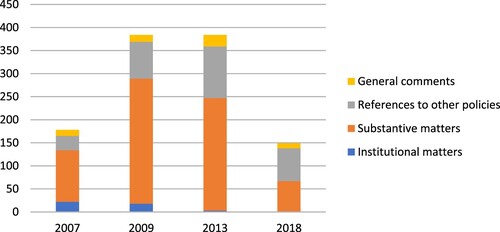

Starting with main types of comments, shows the number of comments by main coding category for each ISC. Across all ISCs, a large majority of comments concern substantive matters (63% of the total) and, to a lesser extent, references to other policy efforts (27%). By contrast, comments about institutional matters (4%), such as turf or control over material resources, and more general comments about the documents or procedure (6%) proved to be rare.

The pattern over time does not show strong support for the expectation that emphasis would shift from institutional to substantive comments. The number of institutional comments does indeed decrease, but was already low in 2007 and 2009. The relative number of substantive comments does not increase. Instead, the category of codes showing most growth involves references to other, existing policy initiatives, suggesting an increase of coordination between climate change adaptation policy and sectoral efforts.

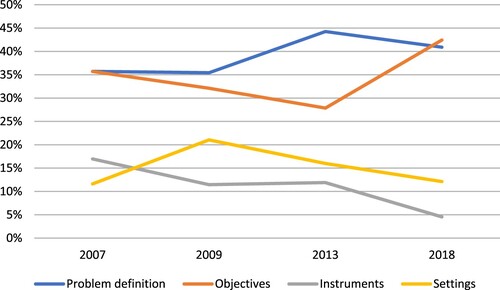

zooms in more closely on the types of comments made within the main category of substantive comments. It shows that, in all ISCs, a relatively large part of these comments relate to either the problem definition (39% average across all years) or objectives (32%) in the proposals (or accompanying documents). Comments about types of instruments (12%) or calibrations of instruments (17%) are less frequent. The following comment illustrates a call for broadening objectives:

Although it is accepted that the main focus of this White Paper is on EU Domestic policy, an External Dimension section is also important when considering the EU response to the global threat of climate change (which knows no borders).

DG RELEX, 2009

Effects of policy cycles

In our theoretical section, we expected to find a link between the ISCs on climate change adaptation and other policy cycles. To explore possible links, shows the balance between comments urging for more and less ambition for the ten DGs that made most comments in the four ISCs. Some DGs consistently give comments urging for more or less ambition in most ISCs (DG Research being an example of the former, DG Agriculture of the latter). However, most DGs are particularly active in some years. For instance, DG Budget only participated in the 2007 and 2009 ISCs, DG ECHO made almost all of its comments in 2013, DG REGIO was both more active and pressed strongly for less ambition in 2009, while the Secretariat General became more active in 2013 and 2018.

When looking into the reasons for DGs to urge for more or less ambition, this often relates to developments in other policy cycles. Most of the comments requiring lower levels of ambition in 2007 and 2009 involved arguments that no new budgetary commitments or allocations should be made under the current 2007–2013 multi-annual financial framework. This was the reason for DG BUDGET to reject the 2009 proposal.

Similarly, various DGs objected to introducing new objectives or financial commitments to ongoing multi-annual sectoral policies. All of our respondents confirmed this to be a key motivation behind requests for lowering ambition levels. This applies to DG AGRI (Common Agricultural Policy, 2007 and 2009), DG TREN (Trans-European Transport Network, 2009) and DG REGIO (structural funds guidelines, 2009). DG TREN, for example, stated:

It is easy to associate financial mechanisms with financial means, and it risks raising expectations that TEN-T support will be available to support this activity when in fact much of the 2007–2013 budget is already earmarked as a result of the multi-annual commitments made at the start of the current Financing Period (FP). DG TREN would ask that the paper avoid any implication that TEN-T funds will be available – at least in the short term – especially when pressures on the budget are already so great.

DG TREN, 2009

Respondents indicated that the new Green Deal proposed by the Von der Leyen presidency has provided momentum to more ambitious climate change adaptation objectives in the new adaptation strategy that is expected in 2021, by increasing the willingness of other DGs to integrate climate change adaptation concerns in their sectoral policies. Although we cannot (yet) substantiate this with quantitative data, this suggests a further confirmation of the expectation.

Effects of institutional reform

Our final expectation was that the creation of new DGs would lead to an increase in institutional conflict. As institutional conflict was very low and even decreased, we do not find evidence for this expectation. During the period of analysis, two new relevant services were founded, DG CLIMA and the EEAS, while DG TREN was split up in DG ENER and DG MOVE. As the EEAS’ mandate on international climate negotiations was transferred to DG CLIMA, the DG for external action (previously RELEX) was no longer involved. DG ENVI lost its status as lead DG due to the creation of CLIMA, but none of the DG’s comments in 2013 and 2018 related to institutional matters. We do, however, observe considerable comments about substantive issues by DG ENVI after it lost its climate action mandate to CLIMA. Various respondents confirmed that the relationship between both DGs started off unaccustomedly, as ENVI lost people, resources and mandates, and had to reposition itself with respect to climate change efforts.

Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, we analysed the patterns of coordination within the European Commission using the ISCs around climate change adaptation policy. Our analysis allows for a number of conclusions and reflections. To start with, we observed that ISCs were primarily used to provide substantive comments, related to problem analyses, objectives or instruments, as well as to strengthen or weaken connections with policy efforts in adjacent domains. Institutional comments, related to mandates or resources, proved rare.

Of the theoretical factors we considered, the dynamics of other policy cycles seems to have had the largest impact on the types of comments made in ISCs. The dominant external cycle for climate change adaptation policy seems to be the financial (MFF) cycle, which also has a large impact on a number of other policy cycles (e.g., regarding the CAP and structural funds). The evidence regarding the creation of new DGs and the stakes involved is mixed, with the data providing partial support for our expectations.

We found little support for an impact of policy maturation. Apparently, processes in which a policy gradually crystallises around a shared set of ideas and moves to more specific, instrument-related debates did not occur in this case. The reason for this may be that all ISCs still belonged to the stage of policy development. In addition, dynamics of policy maturation are closely linked with the existence of (relatively closed) policy communities, whereas EU climate change adaptation policy primarily relies on instruments in other issue areas and therefore is not determined by a single policy community.

Our findings suggest that the underlying question on ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ coordination in the Commission requires nuance as we find a combination of two main forms of coordination in the ISCs we studied. On the one hand, we see elements of negative coordination, where DGs try to shield policy processes in their own domain from commitments made (or implicit) in climate change adaptation documents. Examples of this can be found in the comments made by DG Agriculture and DG Budget in 2007 and 2009 to the effect that the climate change adaptation documents should not introduce new budgetary commitments.

On the other hand, we see an ‘in-between’ form of coordination, in which DGs try to contribute to the overall outcome, but (only) from the point of view of their own policy responsibilities. Examples of this include DG ECHO calling for the mainstreaming of climate change adaptation policies with ongoing disaster risk reduction efforts, and various DGs highlighting initiatives taken in their own domains. Some of these contributions can be interpreted as ‘defensive’ (or: ‘negative’), in the sense that by highlighting initiatives taken under their responsibility, DGs may want to ward off pressure to do more. However, others can also be seen as attempts to strengthen the overall approach, by adding elements that were missing or underestimated.

This ‘in-between’ form of coordination includes elements of negative coordination, as DGs focus almost exclusively on the effects a proposal has on their own remit and do not engage in joint problem-solving (cf. the definitions of negative and positive coordination in Hustedt & Seyfried, Citation2016). However, it goes beyond merely ‘check[ing] the draft for the negative effects on their own area of competence’ (Ibid.) and is aimed at combining the insights and approaches of various DGs (cf. the description of positive coordination by Scharpf, Citation1994). Overall, then, the type of coordination we find resembles less the synoptic/rational ideal of integrated policy coordination, but more Lindblom’s (Citation1959, Citation1979) notion of piecemeal ‘muddling through’, in which each actor contributes from its own, limited, remit. In the end, this type of ‘incremental coordination’ may be a more realistic ideal than ‘pure’ positive coordination, but also a more pro-active and joint enterprise than the rather defensive negative coordination.

Our results also speak to the debate on fragmentation and hierarchy in the European Commission and, more specifically, the role of the SG in the ISC process. A ‘logic of portfolio’ (Trondal, Citation2011) still underlies much of the input of DGs, as may be expected in a relatively large and complex organisation. However, the role of the SG in the ISCs we studied also shows a clear role for top-down coordination. This role seems to have become stronger over time in the four ISCs, with the SG more actively guarding the coherence of proposals with other areas of EU policy-making. We would expect this role to have become even more pronounced under the Von der Leyen (2019–2024) Commission and its overarching ambitions for a European Green Deal (cf. Brooks & Bürgin, Citation2020).

In terms of generalisability to other issue areas, a number of key characteristics of climate change adaptation policies should be noted. Foremost among these is the relatively low salience of the issue of climate change adaptation in the period we studied. This affects the stakes that DGs have in an ISC. As noted in this study, lower stakes may reduce the level of conflict in ISCs. If so, we would expect higher overall levels of conflict in other issue areas that are (politically) more salient. This may even the case for climate change adaptation policies in recent years, as the issue has become more prominent under the Von der Leyen Commission.

Another important factor in our study is the link between policy development on climate change adaptation policy and policy cycles in other issue areas, in particular the MFF. These links are likely also to occur in other issue areas. An important distinction here may be between dominant policy cycles, which shape the timing of developments elsewhere, and policy cycles that follow developments elsewhere (Goetz’s (Citation2014) ‘time-setters’ and ‘time-takers’). The development of climate change adaptation policy is a clear example of ‘time-taking,’ which is likely to affect the dynamics we observe in this regard.

As a final note on generalisability, climate change adaptation is an issue area with relatively few policy instruments of its own. Rather, it relies to a great extent on existing policy instruments in other issue areas, which fall under the remit of other DGs than the lead DG. This leads to particular patterns of interservice coordination, as climate change adaptation policy is almost intrinsically about coordinating initiatives in other areas. This may be different in issue areas in which coordination primarily takes the form of other DGs commenting on the instruments the lead DG wants to put in place.

In addition to these substantive conclusions, our study also allows for conclusions about the use of ISC documents to study coordination in the Commission. Although ISCs offer a good opportunity to study coordination processes, the relationship to other stages in the coordination process is not fixed. Broadly speaking, ISCs are used for three types of comments. The first type concerns issues that were raised before but were not taken up by the lead DG. The second concerns the formalisation of points that were agreed upon with the lead DG earlier but need to go ‘on the record’. The third type of comments relates to new issues that have come up as a result of changes made in earlier rounds of redrafting or due to policy developments in adjacent domains. Which types of comments are made depends on the way the prior (informal) consultation processes went and the extent to which specific DGs were active in them. Although it is generally considered bad form for a DG to come up with major comments at the ISC stage without having raised them before, the extent to which DGs have the capacity and interest to be involved throughout the entire coordination process varies. This prior involvement is reflected in the document that becomes the starting point of the ISC and the comments made by various DGs. Therefore, ISCs need to be seen within the larger context of coordination processes, especially those preceding the ISC. Interviews are an important complement to the data that can be derived from ISC submissions, in order to obtain more insight into the context and background of these submissions.

Future research on this topic could advance along three routes. The first is to combine data from ISCs with more in-depth qualitative data about coordination within the Commission. This would also lead to a better understanding of how ISCs relate to other stages in the coordination process. The second route is to compare our findings around climate change adaptation with other issue areas. In terms of our findings and the theoretical background to our study, the issue areas in these comparative studies should vary in particular in terms of the salience of issues and the stakes that are involved in the policy proposals. This would show to what extent certain patterns of coordination hold across issue areas and what factors are important determinants in that respect. Finally, comparing ISC documents with final legislative output could provide a deeper insight into the impacts of comments made during coordination phases. Ultimately, coordination ought to improve the quality of policy outputs, but the extent to which this is the case remains underexplored.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (35.2 KB)Acknowledgements

Previous versions of the paper were presented at the ECPR General Conference, 24–28 August 2020, and the International Conference on Public Policy, 6–8 July 2021. We acknowledge helpful feedback from Miriam Hartlapp, Philipp Trein and three anonymous reviewers on previous drafts. Dr. Biesbroek’s contribution was financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO-VENI grant no: 451-117-006 4140).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jeroen J. L. Candel

Jeroen Candel is associate professor at the Public Administration and Policy Group, Wageningen University, the Netherlands.

Sebastiaan Princen

Sebastiaan Princen is associate professor at the Utrecht School of Governance, Utrecht University, the Netherlands

Robbert Biesbroek

Robbert Biesbroek is associate professor at the Public Administration and Policy Group, Wageningen University, the Netherlands

References

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. (1993). Agendas and Instability in American Politics. The University of Chicago University Press.

- Biesbroek, R., & Swart, R. (2019). Adaptation policy at supranational level? Evidence from the European Union. In E. C. H. Keskitalo, & B. Preston (Eds.), Research Handbook on Climate Change Adaptation Policy (pp. 194–211). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Brooks, E., & Bürgin, A. (2020). Political steering in the European Commission: A comparison of the Energy and health sectors. Journal of European Integration, 43(6), 755–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1812063

- Candel, J. (2019). EU budgetary Politics and Its implications for the bioeconomy. In L. Dries, W. Heijman, R. Jongeneel, K. Purnhagen, & J. Wesseler (Eds.), EU Bioeconomy Economics and Policies: Volume I (pp. 51–67). Macmillan.

- Candel, J. J. L., & Biesbroek, R. (2018). Policy integration in the EU governance of global food security. Food Security, 10(1), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-017-0752-5

- Candel, J. J. L., Breeman, G., & Termeer, C. (2016). The European Commission’s ability to deal with wicked problems: An In-depth case study of the Governance of Food security. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(6), 789–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1068836

- Dreyfus, M., & Patt, A. (2012). The European Commission White Paper on adaptation: Appraising its strategic success as an instrument of soft law. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 17(8), 849–863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-011-9348-0

- Dupuis, J., & Biesbroek, R. (2013). Comparing apples and oranges: The dependent variable problem in comparing and evaluating climate change adaptation policies. Global Environmental Change, 23(6), 1476–1487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.022

- EEA. (2017). Climate Change, Impacts and Vulnerability in Europe 2016: an Indicator-Based Report, EEA Report No 01/2017. European Environment Agency.

- Egenhofer, C., Van Schaik, L., Kaeding, M., Hudson, A., & Ferrer, J. N. (2006). Policy Coherence for Development in the EU Council: Strategies for the Way Forward. Centre for European Policy Studies.

- Finke, D. (2019). Turf wars in government administration: Interdepartmental cooperation in the European commission. Public Administration, 98(2), 498–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12633

- Goetz, K. H. (2009). How does the EU tick? Five propositions on political time. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802589214

- Goetz, K. H. (2014). Time and Power in the European commission. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 80(3), 577–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852314543436

- Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of Economic policymaking in britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

- Hartlapp, M., Metz, J., & Rauh, C. (2014). Which Policy for Europe? Power and Conflict Inside the European Commission. Oxford University Press.

- Hustedt, T., & Seyfried, M. (2016). Co-ordination across internal organizational boundaries: How the EU Commission Co-ordinates climate policies. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(6), 888–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1074605

- IPCC. (2014). Annex II: Glossary.

- IPCC. (2018). Annex I: Glossary. In V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor & T. Waterfield (Eds.) Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, IPCC.

- IPCC. (2007). Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A.(eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 104 pp.

- Jordan, A., & Schout, A. (2006). The Coordination of the European Union: Exploring the Capacities of Networked Governance. Oxford University Press.

- Kassim, H. (2018). The European Commission as an administration. In E. Ongaro, & S. van Thiel (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Public Administration and Management in Europe (pp. 783–804). Palgrave.

- Kassim, H., Connolly, S., Dehousse, R., Rozenberg, O., & Bendjaballah, S. (2017). Managing the house: The presidency, agenda control and policy activism in the European commission. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(5), 653–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1154590

- Knill, C., Schulze, K., & Tosun, J. (2012). Regulatory policy outputs and impacts: Exploring a complex relationship. Regulation & Governance, 6(4), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2012.01150.x

- Lindblom, C. E. (1959). The science of “Muddling through”. Public Administration Review, 19(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/973677

- Lindblom, C. E. (1979). Still muddling, not yet through. Public Administration Review, 39(6), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.2307/976178

- Nugent, N., & Rhinard, M. (2015). The European Commission (2nd ed). Palgrave.

- Ovádek, M., Lampach, N., & Dyevre, A. (2020). What’s the talk in Brussels? Leveraging Daily News coverage to measure issue attention in the European Union. European Union Politics, 21(2), 204–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520902530

- Princen, S., & Rhinard, M. (2006). Crashing and creeping: Agenda-setting dynamics in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(7), 1119–1132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760600924233

- Remling, E. (2018). Depoliticizing adaptation: A critical analysis of EU climate adaptation policy. Environmental Politics, 27(3), 477–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1429207

- Sabatier, P. A. (1998). The advocacy Coalition framework: Revisions and relevance for Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 5(1), 98–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501768880000051

- Scharpf, F. W. (1994). Games real actors could play. Positive and negative coordination in embedded negotiations. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 6(1), 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692894006001002

- Selianko, I., & Lenschow, A. (2015). Energy policy coherence from an intra-institutional perspective: Energy security and environmental policy coordination within the European commission. European Integration Online Papers, 19(2). DOI:10.1695/2015002

- Senninger, R., Finke, D., & Blom-Hansen, J. (2020). Coordination inside government administrations: Lessons from the EU commission. Governance, 34(3), 707–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12525

- Stevens, A., & Stevens, H. (2001). Brussels Bureaucrats? The Administration of the European Union. Palgrave.

- Stokman, F. N., van Assen, M. A. L. M., van der Knoop, J., & van Oosten, R. C. H. (2000). Strategic decision making. Advances in Group Processes, 17, 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0882-6145(00)17006-7

- Stroß, S. (2017). Royal roads and dead ends. How institutional procedures influence the coherence of European Union policy formulation. Journal of European Integration, 39(3), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2017.1281260

- Tholoniat, L. (2009). The temporal constitution of the European Commission: A timely investigation. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(2), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802589230

- Trondal, J. (2011). Bureaucratic structure and Administrative behaviour: Lessons from international bureaucracies. West European Politics, 34(4), 795–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.572392