ABSTRACT

The strengthening of the populist radical right poses an important challenge for European integration. This article explores whether democratic backsliding among member states has acted as a catalyst for broader PRR cooperation at the EU level. Studying the co-sponsorship and contents of parliamentary questions and roll-call vote cohesion of PRR representatives in the European Parliament from 2009 to 2019, we examine the extent and substance of their joint polity-based contestation of European integration. Our findings indicate that overall levels of PRR cooperation remain low and concentrated within European party groups, suggesting that ideological divergences between PRR actors and their institutional fragmentation within the EP still hamper their formal cooperation at the European level. These insights feed into debates on the potential and limitations of transnational cooperation of PRR actors.

Introduction

The strengthening of populist radical right (PRR) forces across Europe, and especially in the European Parliament (EP), has triggered growing interest in their ability to cooperate and eventually shape outcomes at the European level (Caiani, Citation2018; McDonnell & Werner, Citation2019b; Usherwood & Startin, Citation2013). The bulk of existing literature is sceptical towards PRR parties’ ability to organise coherently and effectively at the European level, pointing to a general lack of coherence in their policy demands (Falkner & Plattner, Citation2020, p. 734; Startin, Citation2010, p. 431) as well as substantive disagreements and domestic constraints that have hampered the formation of a common party group to date (Brack & Startin, Citation2015, p. 248; McDonnell & Werner, Citation2019b). Still, the EP’s inherently transnational set-up offers fertile ground for the development of ties between PRR representatives from different countries, with recent studies pointing to a growing discursive cohesion of PRR actors in specific policy fields (Bélanger & Wunsch, Citation2021; Kantola & Lombardo, Citation2020) and suggesting that they wield some indirect influence upon policy outcomes (Bergmann et al., Citation2021).

In parallel to the increased presence and visibility of PRR actors at the EU level, recent years have seen a growing trend of democratic and rule of law violations among several EU member states and mounting concern over the EU’s ability to respond to such developments (Kelemen, Citation2020; Sedelmeier, Citation2017). EU-level attempts to voice criticism and even sanction the erosion of democratic quality in several member states have triggered both normative critique (Müller, Citation2015; Theuns, Citation2020) and a sharp political response from the countries concerned contesting the EU’s legitimacy to interfere and emphasising national sovereignty in matters related to the domestic polity (Bayer, Citation2020).

Bringing together the strengthening of PRR parties across Europe and the emergence of democratic backsliding, we revisit the question of EU-level PRR cooperation from an innovative angle. Whereas the role of populism as a driver of democratic backsliding has been well established (Enyedi, Citation2016; Vachudova, Citation2019), we propose to explore whether democratic backsliding – often implemented precisely by political actors belonging to the PRR camp – is inversely facilitating greater formal cooperation among PRR forces at the EU level. To what extent has the emergence of democratic backsliding among member states acted as a catalyst for more generalised contestation of European integration by PRR actors?

To answer this question, we investigate the patterns and contents of cooperation among PRR Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) over the past decade (2009–2019) via two original datasets on the co-sponsorship of parliamentary questions and roll-call vote coalitions. Our empirical analysis focuses on three distinct areas: besides initiatives directly about democratic backsliding among member states, we also probe those related to widening (EU enlargement) and deepening (constitutional questions) as the two central dimensions of European integration. Moreover, we examine several ideological and institutional factors that shape PRR cooperation at the European level.

Our empirical analysis indicates that democratic backsliding has not served to federate PRR voices at the European level. Instead, we find that overall levels of PRR cooperation on polity-related matters remain low and concentrated within European party groups (EPGs). Ideological divergences between PRR actors and their institutional fragmentation within the EP therefore still appear to hamper their formal cooperation at the European level.

The next section develops our argument regarding the expected relationship between processes of democratic backsliding and EU-level PRR cooperation and spells out our hypotheses. We then describe our research design and datasets, before presenting our empirical findings on the co-sponsorship of parliamentary questions and roll-call voting patterns. The conclusion discusses the main implications of our findings for understanding EU-level PRR cooperation and sketches how future research could further probe the impact of democratic backsliding at the European level.

From democratic backsliding to PRR polity-based contestation

Our study analyses the EU-level cooperation of PRR actors in the context of ongoing democratic backsliding among several EU member states. We are interested in examining the scope of PRR cooperation and in probing obstacles to such cooperation identified already in previous studies. We situate our analysis at the level of the EP, the arena in which many national PRR parties obtained their first electoral victories and where efforts at transnational PRR cooperation are most advanced (McDonnell & Werner, Citation2019b; Rappold & Wunsch, Citation2019). Our analysis focuses on PRR representatives’ joint polity-related contestation, rather than on their institutional cooperation or policy influence that have been the focus of previous studies. Although constitutive issues – defined as comprising ‘adhesion, enlargement, democratisation, competence definition and institutional powers’ (Bartolini, Citation2005, p. 355) – have been singled out as central to populist, Eurosceptic mobilisation (Braun et al., Citation2016, p. 587), empirical studies tend to overlook PRR’s polity-related contestation (Brack & Startin, Citation2015, p. 241). By probing patterns and substance of PRR MEPs’ activities in light of current trends of democratic backsliding, but also examining more traditional hypotheses related to the institutional and ideological obstacles to their closer collaboration, we propose a comprehensive insight into the current state of PPR cooperation inside the EP.

We study PRR collaboration at two distinct levels. First, we analyse the co-sponsorship of parliamentary questions as a measure of agenda-setting efforts by PRR MEPs: what issues do they emphasise when co-sponsoring parliamentary questions? Parliamentary questions have been used in the EP for three main purposes: executive oversight (Proksch & Slapin, Citation2011), signalling responsiveness to constituents and representing territorial interests (Brack & Costa, Citation2019) and agenda-setting (Meijers & van der Veer, Citation2019b). Adopting the latter view, we contend that PRR actors may use parliamentary questions to raise new issues on the EP’s agenda or to push specific framings of debated topics.

Second, we examine PRR MEPs’ ability to coalesce around a common agenda at roll-call votes. Whereas agenda-setting requires more coordination, roll-call votes are politically costlier since they require MEPs to express a clear position on a given policy issue either in line with or in opposition to their national and/or party group preference. MEPs’ behaviour at roll-call votes is the most studied area of legislative behaviour inside the European Parliament (Hix & Høyland, Citation2014). While there is consensus that ideological orientation on the left-right and EU integration dimensions structure party competition in the EP, scholars debate the extent to which MEPs follow the preferences of their national parties or their EPG, and how timing and differences in positions and issue salience between the two principals affect voting behaviour (Chiru & Stoian, Citation2019). We therefore use roll-call votes as an indicator of the extent to which PRR MEPs’ follow a common agenda that may directly translate into policy outcomes.Footnote1

We seek to establish whether there are shared agenda-setting efforts and cohesive voting patterns among PRR forces that suggest a deliberate attempt to wield polity-related impact at the EU level. We are particularly interested in whether the contestation of EU-level responses to democratic backsliding acts has served to federate PRR voices in the EP, enabling them to overcome the ideological and institutional barriers that have hampered their more effective cooperation to date. While we do not seek to establish a direct causal link between the erosion of democratic standards in member states and the strengthening of transnational PRR cooperation, we do expect democratic backsliding to provide a common reference point for PRR parties and thereby to potentially favour their broader cooperation around polity-based contestation at the European level.

Several reasons lead us to expect such a pattern. To begin with, there is a substantive overlap between the sets of actors engaged in processes of democratic erosion and those driving contestation of the European project, as the Polish Law and Justice Party (PiS) and Hungary’s Fidesz prominently illustrate. The Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) is another PRR party that has used its return to power since March 2020 to weaken the rule of law and media pluralism and recently joined Hungary and Poland to contest the introduction of a rule of law conditionality regime for EU funds (EurActiv, Citation2020). Certainly, the approximation of actors engaged in democratic backsliding and those with a PRR orientation is an imperfect one. Not all PRR forces support the outright dismantling of liberal democracy, nor is every instance of backsliding in the EU carried out by PRR parties, as the case of the Romanian Social Democrats shows (Iusmen, Citation2015). Nonetheless, we can expect them to be sympathetic to backsliders irrespective of their orientation, for both ideological and strategic reasons.

Populist radical right parties are defined by a combination of nativism, authoritarianism, and populism (Mudde, Citation2010). In ideological terms, their populism leads PRR actors to embrace an illiberal view of democracy and despise the rule of law constraints to which the EU’s mainstream forces appeal when attempting to address backsliding. Their nativism and authoritarianism, in turn, contribute to broader regime scepticism (de Vries, Citation2018) and a rejection of any further deepening or widening of European integration, which they perceive as diluting national identities. Perpetrators of democratic backsliding have frequently adopted the same rhetoric, leading us to expect an overlap between PRR orientation and a reluctance to support decisive EU action to criticise or sanction democratic and rule of law violations. From a strategic perspective, PRR actors have an interest in fuelling confrontation between EU institutions and national governments to signal their ‘monolithic opposition to supranationality’ (Vasilopoulou, Citation2013, p. 164) and weaken the prospects for further integration. Increased collaboration to contest EU intervention on instances of democratic backsliding may thus serve as a springboard favouring PRR’s cooperation on polity-related matters more generally.

This reasoning leads us to focus our inquiry more narrowly on PRR actors rather than on a broader group of Eurosceptic MEPs. For one, we do not examine populist radical left parties, whose Euroscepticism finds expression at the level of policies rather than of the regime as a whole (Vries, Citation2018), since members of this party family contest the EU primarily based on the perception that it promotes a neoliberal agenda (Pirro et al., Citation2018). We similarly choose to exclude non-populist radical-right parties, as their reputation, size and ideological features make them undesirable partners for the PRR MEPs who have increasingly managed to acquire respectability (McDonnell & Werner, Citation2018). Non-populist radical-right parties, in contrast, have been significantly less successful in winning seats in the EP than PRR parties and, when they do, often find themselves in a marginalised position due to their xenophobic or racist reputations or their overt rejection of democracy.

Against this backdrop, we formulate two distinct theoretical expectations regarding the scope of polity-related contestation by PRR actors. For one, we expect debates about democratic and rule of law violations to provide a focal point for increased reactive cooperation among PRR forces to challenge or even block EU criticism of instances of backsliding. Beyond this immediate response, we suggest that the emergence of backsliding and joint PRR mobilisation against perceived EU interference in domestic affairs may create a context that facilitates proactive cooperation among PRR actors seeking to challenge European integration more broadly.

Reactive cooperation hypothesis: PRR cooperation in the EP is mainly reactive, focusing on issues related to democratic backsliding that target members of their party family directly.

Proactive cooperation hypothesis: PRR cooperation in the EP indicates a broader proactive attempt to shape polity-related matters related to the deepening and widening of the EU.

Whereas the political context may drive deeper PRR cooperation at the EU level, previous studies have noted numerous institutional and ideological obstacles preventing PRR MEPs from mobilising coherently and effectively at the European level. These include diverging interests and the ensuing inability to define a common agenda (Brack, Citation2017; Startin, Citation2010, p. 431), PRR MEPs’ lack of access to input channels due to a combination of exclusion by the cordon sanitaire imposed by the mainstream party groups and self-exclusion from active policy formulation (Almeida, Citation2010, p. 248), and the lack of substantive coherence of their policy demands (Falkner & Plattner, Citation2020; Whitaker & Lynch, Citation2014, p. 250). To account for such possible countervailing factors, we study the impact of ideological distance between the national parties to which two given PRR MEPs belong as a potential obstacle to their cooperation. Moreover, we examine the role of institutional factors, most prominently PRR MEPs’ fragmentation across different EPGs, in explaining varying degrees of cooperation.

Ideological distance hypothesis: Ideological distance decreases the likelihood of PRR cooperation in the EP.

Institutional fragmentation hypothesis: Institutional fragmentation decreases the likelihood of PRR cooperation in the EP.

Research design and data

We propose to study EU-level PRR cooperation against the backdrop of democratic backsliding, which we expect not only to fuel joint opposition to EU interference in rule of law violations in member states, but also potentially to serve as a catalyst for broader polity-related contestation by PRR parties at the European level. To identify PRR representatives in the EP, we rely on PopuList (Rooduijn et al., Citation2019) (see Table A1 in online appendix for full list of parties). We focus on the EP’s 7th and 8th terms (2009–2019) and create two datasets: one of parliamentary questions co-sponsored by PRR MEPs and another containing roll-call votes on the three categories of topics we chose to examine: democratic backsliding, EU enlargement, and constitutional questions. We coded both datasets qualitatively. For parliamentary questions, we identified which substantive topics draw most cooperation and whether they qualify as reactive or proactive forms of cooperation. For roll-call votes, we established which position corresponded to polity-based contestation. In a second step, we matched the datasets with information on the programmatic positions of PRR parties and individual characteristics of their MEPs. We then ran a series of regressions on the determinants of parliamentary questions co-sponsorship and joint polity-based contestation during roll-call votes.

Patterns of co-sponsorship of parliamentary questions

To build our dataset, we trimmed an initial corpus of 6’453 co-sponsored written parliamentary questions to a sample containing only those questions co-sponsored by at least two MEPs from PRR parties, yielding a dataset of 352 questions for the 7th term and 522 questions for the 8th term. Next, we constructed a dyadic dataset combining pairwise all 91 PRR MEPs in the 7th term (4′095 pairs) and the corresponding 126 MEPs in the 8th term (7′875 pairs). We use a zero-inflated negative binomial regression model to account for the very high share of zeros in our dependent variable and the different data generation processes. Thus, while some MEPs had fewer occasions to co-sponsor a parliamentary question due to a shorter tenure (i.e., systematic zero observations), others simply chose not to do so. To predict the systematic zero observations, the model includes the MEPs’ combined total tenure in that term.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable in our analyses, Questionsij, is the count of written parliamentary questions co-sponsored by PRR MEPi and PRR MEPj. For the qualitative coding, we used the thematic focus of the EP’s different committees to assign each parliamentary question to a specific topic area. We coded as ‘reactive’ cooperation parliamentary questions relating directly to questions of democratic backsliding (contained in the broader category of ‘civil liberties, justice, home affairs’) and as ‘proactive’ those concerning widening (typically under ‘foreign and security policy’) or deepening (generally under the heading ‘constitutional and interinstitutional affairs’).

Independent variables

The substantive ideological distance variables indicate the absolute difference between the two MEPs’ national parties’ positions on EU enlargement, EU competencies, and EU power transfer, which we retrieved from the 2009 and 2014 EP election studies’ manifesto data (Schmitt et al., Citation2018). We computed the left-right and EU position distance variables in the same way, using data from ParlGov (Döring & Manow, Citation2021). We controlled for several additional factors that are likely to shape co-sponsorship probabilities. For one, we expected co-sponsorship to be more frequent when MEPs belong to the same EPG and even more so the same national party. Similarly, we expected higher rates of co-sponsorship when both PRR MEPs are backbenchers, as MEPs who hold party or committee office have less time to sponsor parliamentary questions.

Roll-call votes

A total of 95 final roll-call votes were cast across the two EP terms dealing with the three studied areas. We coded these votes based on their level of salience, distinguishing low salience (i.e., technical reports), medium, and high. 84 of the votes were on motions for resolution, whereas only 11 concerned legislative proposals. Our sample includes 6 votes on democratic backsliding from the 7th term and 15 from the 8th term, 25 and 23 votes respectively on enlargement, and nine (7th term) and 17 votes (8th term) on constitutional issues.

Previous analyses of vote cohesion of PRR MEPs have focused either on the aggregate level of cohesion between or within EPGs or on the voting similarity of PRR parties, finding an overall cohesion of the right-wing Eurosceptic bloc of below 50% (McDonnell & Werner, Citation2019b; Whitaker & Lynch, Citation2014). In substantive terms, Cavallaro et al. (Citation2018) have shown that PRR MEPs tend to vote very differently on economic matters, reflecting their ideological heterogeneity on this dimension.

Dependent variable

To assess the overall levels of vote cohesion in the two analysed terms, we coded the dependent variable in our roll-call vote analyses as 1 if the MEP voted against polity-related contestation and 0 otherwise. Our coding was based on a reading of the actual text underlying the vote obtained from the EP’s website and sought to determine support for or dissent from an agenda of polity-related contestation. For instance, we would consider a motion rejecting an initiative to expand EU competencies as an expression of support for polity-related contestation, whereas a motion criticising rule of law violations in a member state would be considered contrary to this goal.

Independent variables

Our substantive ideological distance variables indicate the absolute difference between the MEPs’ national party positions on EU integration, EU enlargement, EU competencies and EU power transfer and the mean positions on the same dimensions of all PRR parties weighted by the number of EP seats. These variables rely on the same sources as indicated above. In modelling roll-call dissent, we control for EPG loyalty, as we expect PRR MEPs to be more likely to engage in polity-related contestation when doing so does not conflict with their EPG line. The loyalty to EPG variable is a dummy coded 1 if the MEP voted like the majority of legislators in her EPG. Moreover, we control for the EPG affiliation of the MEP, given the fact that some PRR MEPs are a minority in their EPGs while others dominate them, making the latter more likely to endorse polity-related contestation. We control for the salience of the vote, since we expect polity-related contestation to be more prevalent on more salient votes, which are likely to gain greater media attention. In addition, we control for vote type: cohesion around polity-related contestation should be higher for motions for resolution than for legislative initiatives, since the former are mostly used for position-taking (Høyland, Citation2010). Another control variable indicates the affiliation of the MEP with a national party in government at the time of the vote. MEPs of governing PRR parties might have different incentives to endorse or reject polity-related contestation at RCVs depending on their own governmental priorities or national coalition politics. We also examine MEP past experience in EP as an ordinal variable indicating the number of terms served by the legislator since the fifth term. Finally, we expect backbencher PRR MEPs (those not holding office at EPG or EP level) and EP newcomers to feel freer to engage in polity-related contestation than those who hold office or who have been socialised in previous terms to follow the line of their EPG.

Empirical findings

Our study examines the extent to which the rise of democratic backsliding in several EU member states has created a context that favours greater cooperation among PRR MEPs not only to ward off EU sanctioning of rule of law violations, but to contest European integration more widely. Our empirical findings allay fears that the emergence of backsliding trends inside the EU could facilitate more generalised PRR contestation of European integration. Instead, we show that PRR actors do not agree substantively on the endorsement of backsliding, nor do they position themselves jointly on constitutional issues facing the EU. Their vote cohesion is even poorer on issues related to enlargement. Overall, cooperation remains low and largely restricted to MEPs from the same EPG or even the same national party. These findings confirm earlier scepticism that persistent internal divergences within the PRR camp hamper their collaboration at the European level (Almeida, Citation2010; Startin, Citation2010), while providing fresh evidence on the areas and extent of populist cooperation inside the EP.

Co-authorship of parliamentary questions

Our analysis of co-sponsorship patterns for parliamentary questions indicates a very limited degree of PRR cooperation: in both terms around 93% of the MEP pairs never co-sponsored a parliamentary question. Moreover, the three fields we identified as potential areas of PRR cooperation feature extremely rarely. Of the 874 questions examined, only 20 (2.3%) relate to democratic backsliding and 40 (4.6%) to ‘proactive’ collaboration on enlargement or constitutional issues. With few exceptions, parliamentary questions on these topics were exclusively submitted by MEPs sharing not only an EPG affiliation, but also coming from the same national party. We thus find little evidence for either our reactive or proactive cooperation hypotheses. Instead, as shown in Figure A1 (see online supplementary material), co-sponsored questions spread across a broad range of policy issues.

Turning to the multivariate analyses of drivers of co-sponsorship, we ran the zero-inflated negative binomial regressions separately for each of the two terms. The results in indicate that both individual characteristics and party ideological distance matter for the collaboration of PRR MEPs. At the individual level, MEPs sharing a backbencher status were significantly more likely in the 8th term to co-sponsor parliamentary questions. In both terms, most of the co-sponsorship took place between MEPs from the same national party or the same EPG, lending support to our institutional fragmentation hypothesis. In the 8th term, the co-sponsorship between MEPs representing the same national party increased substantially. This is mostly due to the high level of cooperation among MEPs from the French Front National (FN), which accounts for almost 60% of the PRR dyads that co-sponsored at least one parliamentary question. Figures A2 and A3 in the online appendix further explore the magnitude of the shared party and EPG affiliations.

Table 1. Regression analysis results.

A higher ideological distance regarding the parties’ positions on the transfer of powers to the EU results in a decreased likelihood of co-sponsorship, but the effect reaches conventional levels of statistical significance only for the 7th term. Counterintuitively, in the 8th term PRR MEPs were more likely to co-sponsor parliamentary questions with colleagues from parties with dissimilar positions on EU integration in general and EU competencies in particular.

In both samples, MEPs representing national parties with similar positions regarding EU enlargement were more likely to submit written parliamentary questions together. However, as shown in Figure A4 (see online appendix), this effect is not particularly strong. For parliamentary questions, our data thus provides mixed evidence on our ideological distance hypothesis.

Roll-call votes

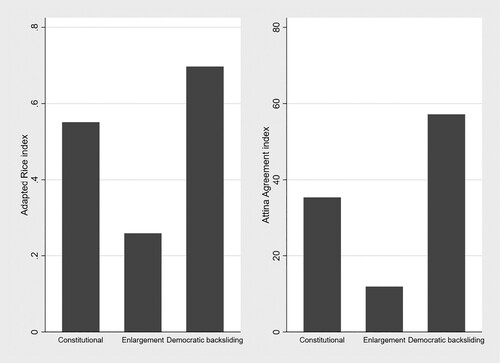

We evaluate vote cohesion of PRR MEPs using the Rice and Attina vote agreement indices (see the supplementary material for operationalisation details). indicates relatively low cohesion levels for roll-call votes on democratic backsliding and constitutional issues and very low levels for the votes on enlargement. The degree of dissent from joint polity-related contestation varies considerably between EPGs and appears dependent on the size of the PRR MEP cohort in each group. Thus, two of the groups dominated by PRR MEPs have very small levels of such dissent, with 3% for EFDD and 6.9% for Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF). Conversely, we record the highest levels of deviation from polity-related contestation where PRR MEPs represent a minority: 45.1% for the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and 74.7% for the European People’s Party (EPP).

We run our binary logistic regression first on the pooled sample, and then separately on the three categories of votes (see above). For the pooled sample, it appears that PRR MEPs most deviated from polity-related contestation on EU enlargement votes and that their degree of cohesion increased slightly from the 7th to the 8th term. The pooled model also shows that, as expected, loyalty to the EPG was a major factor making PRR MEPs vote against or abstain from supporting populist positions. The positive coefficient of the national party EU position variable indicates that MEPs representing national parties that embrace softer versions of Euroscepticism are more likely to refuse polity-related contestation compared to their colleagues affiliated with hard Eurosceptic national parties. MEPs affiliated to EPGs with a strong PRR orientation tend to deviate less from joint polity-related contestation compared with non-affiliated PRR MEPs. The effect disappears (ECR) or is reversed altogether (EPP) for those EPGs with smaller shares of PRR MEPs. Somewhat surprisingly, three of the four variables measuring the ideological distance between the weighted average positions of all the PRR parties, and the party of the MEP indicate negative effects: in contradiction to our ideological distance hypothesis, the higher the distance, the higher the probability of following populist positions. Figure A5 in the online appendix illustrates the effect of EU position distance.

The regressions run separately for the three types of votes corroborate many of the findings discussed for the pooled analysis. Again, irrespective of the vote topic, PRR MEPs from less Eurosceptic EPGs tend to vote less often in favour of polity-related contestation. Another finding corroborated across topics, with the partial exception of votes on democratic backsliding, is that MEPs belonging to PRR-led EPGs (EFD, EFDD and ENF) more often engage in polity-related contestation compared to non-affiliated PRR MEPs. Consistent with this logic, the PRR MEPs affiliated with the mainstream EPP appear four times less likely to endorse polity-related contestation than non-attached MEPs on constitutional issues. These findings lend support to our institutional fragmentation hypothesis that sees the dispersal of PRR MEPs across different EPGs as a key obstacle to their cooperation.

The greater cohesion on roll-call votes from the 7th to the 8th term observed for the pooled sample appears to be driven by the votes on enlargement, signalling an increasingly united front by PRR MEPs in this respect. EPG loyalty has a negative effect on following the populist line on enlargement but does not make any difference for the other two analyzed categories. Finally, PRR MEPs representing governing parties are almost three times more likely to vote against initiatives condemning democratic backsliding, which is logical given the involvement of some of their parties in such processes.

Overall, our findings on roll-call votes lend greater support to our reactive cooperation hypothesis, albeit even here we find low cohesion overall. We do not find any evidence for our proactive cooperation hypothesis, which expected voting patterns to indicate broader contestation of European integration by PRR MEPs. Concerning determinants of vote cohesion, in contrast to our ideological distance hypothesis, distance from the mean PRR position appears to increase, rather than lower, the likelihood of voting in favour of polity-related contestation. This counter-intuitive finding is explained by the fact that national parties that take more extreme positions also tend to adhere more strictly to an agenda of polity-related contestation. Enlargement votes provide a good illustration of this logic, with parties such as the Dutch Freedom Party (PVV), the Flemish Vlaams Belang (VB) or the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) being much more radical in their rejection of further EU enlargement in their manifestos than the average PRR party and consistently voting against any measures or reports that might move enlargement talks further.

In sum, our findings indicate a limited degree of joint polity-related contestation of PRR MEPs at the level of both agenda-setting via parliamentary questions and roll-call vote cohesion. In substantive terms, our findings lend slightly greater support to our reactive cooperation hypothesis that expected PRR collaboration to be geared towards protecting one another from EU pressure over democratic backsliding. We find little evidence for proactive PRR cooperation aimed at shaping polity-related outcomes regarding the widening (enlargement) or deepening (constitutional matters) of European integration. With respect to the co-sponsorship of parliamentary questions, our results show that this form of cooperation is rare for PRR MEPs and, where it occurs, tends to concern members of the same EPG. Substantively, we find foreign and security policy, including enlargement, to be among the more frequent topics of PRR representatives’ parliamentary questions. However, we observe neither a particular emphasis on issues relating to democratic backsliding, nor any general focus on polity-related matters. Roll-call vote cohesion around a common PRR agenda is similarly low. There is a slightly greater cohesion on democratic backsliding, but no clear indication that democratic backsliding has served as a catalyst for the broader advocacy of an alternative vision of European integration by PRR actors. Again, the failure to pursue a common agenda at roll-call votes is mainly driven by ideological differences and by PRR MEPs’ institutional dispersal across different EPGs, confirming the persistence of the two central obstacles to closer PRR cooperation that we had identified in our ideological distance and institutional fragmentation hypotheses.

Conclusion

Our study set out to revisit the question of EU-level PRR cooperation from an innovative angle, assessing whether democratic backsliding among several EU member states has served as a focal point for PRR cooperation and a catalyst for their broader polity-based contestation of European integration. Our evaluation of issue emphasis and agenda-setting efforts via the co-sponsorship of parliamentary questions and voting cohesion of PRR forces in the EP provides a comprehensive insight into PRR MEPs’ substantive priorities as well are their degree of formal cooperation over the past two EP terms (2009–2019). In essence, our empirical findings do not provide evidence for the emergence of a proactive PRR coalition pursuing a common agenda of polity-related contestation and signal only limited evidence for reactive cooperation. Instead, our findings suggest that ideological divergences within the PRR camp and the institutional dispersal of MEPs across different EPGs continue to hamper their formal collaboration. While ideological proximity enables some instances of co-sponsorship of parliamentary questions, the vast majority of questions co-authored by PRR MEPs does not cross national party, let alone EPG lines. Institutional fragmentation thus still acts as a powerful obstacle to greater PRR cooperation. Substantively, PRR parties’ agenda-setting efforts are spread broadly across multiple policy areas, rather than focusing on the polity-based contestation we hypothesised. When it comes to roll-call votes, we note a greater cohesion of PRR MEPs on votes relating to democratic backsliding, but even here, their cohesion remains low especially for MEPs from EPGs in which PRR representatives are a minority.

How may we interpret these findings? Most fundamentally, they signal that democratic backsliding has not (yet) served as a catalyst towards more successful formal cooperation among PRR parties inside the EP. Instead, our analysis lends support to earlier studies that viewed the significantly lower roll-call vote cohesion among PRR EPGs as signalling the ‘dimensionality of Euroscepticism’ (McDonnell & Werner, Citation2019a, p. 1763), whereby the shape and depth of contestation of the European project differ among PRR parties, leading to less consistent collaboration on polity-related matters. Our findings of a low degree of cohesion even regarding a reactive agenda focused on contesting EU interference in democratic backsliding seem to indicate a more general persistence of internal divergences among PRR MEPs and a reluctance on the part of many to openly endorse backsliding practices. Overall, the fragmentation of PRR MEPs over several EPGs appears not only a symptom of their internal divergences, but also acts as an enduring obstacle to their effective cooperation at the EU level.

Rather than observing any marked intensification of EU-level PRR cooperation against the backdrop of democratic backsliding, we see a much more gradual and partial development towards greater collaboration. This tends to focus on pre-election attempts to find sufficient common ground for institutionalised cooperation among PRR MEPs (Rappold & Wunsch, Citation2019), but has so far failed to culminate in the creation of a single EPG that would remove many of the enduring obstacles to more effective cooperation that our study highlights. Still, despite the ideological divergence and the institutional dispersal of PRR MEPs across several party groups, the EP has made EU-level PRR cooperation more plausible over time. Not only does it provide a platform for increased national visibility and significant financial resources, but it has become an arena that contributes to the normalisation of populists and enables them to enhance their domestic respectability (McDonnell & Werner, Citation2019b). Current trends therefore suggest that the creation of a joint group including most PRR MEPs is becoming more likely, as indicated by the publication in July 2021 of a joint manifesto of PRR parties in the EP contesting the creation of a ‘European superstate’ (Politico, Citation2021).

Our study represents a first attempt to analyse the interactions between democratic backsliding and European integration not through the lens of EU responses to such trends, but rather in terms of the impact of democratic backsliding in member states upon EU-level processes and outcomes. As democracy and the rule of law come under pressure in more member states, and backsliding deepens in those currently concerned, we can expect such trends to have an increasingly direct impact on the conduct and orientation of EU policy-making. We therefore end our article by sketching several avenues for future research on the interactions between democratic backsliding and European integration.

First, future studies could expand on our efforts to study the impact of democratic backsliding upon cooperation patterns inside the EP. Whereas we do not find evidence that the emergence of backsliding has intensified the overall level of cooperation between PRR MEPs, it may well have facilitated coalition-building among sub-groups of MEPs in different ways. One option would be the emergence of new geographic divides, rather than the ideological divisions that were the focus of our analysis. This concerns in particular the East–West divide which has recently received greater attention again (Anghel, Citation2020): do MEPs from Eastern member states come together to defend an alternative view of democracy inside the EP?

A second avenue for future research concerns a different arena, the Council, which may provide a more straightforward opportunity for proactive cooperation among backsliding governments uniting to contest specific policies – e.g., the migrant relocation scheme – or the broader design of European integration. The attempt by Poland and Hungary in autumn 2020 to block the adoption of the EU’s budget and the Covid Recovery Fund in opposition to the introduction of rule of law conditionality for EU funds provides an example of the targeted cooperation of backsliding regimes seeking to assert themselves at EU level. Again, shifting alliances may be particularly visible along geographic divides, as the growing political importance of the Višegrad group seems to suggest (Braun, Citation2020).

A final line of potential inquiry concerns the impact of democratic backsliding upon the EU’s ability to engage in coherent and credible external action. The countervailing impact of authoritarian diffusion upon international democracy promotion at the global level is becoming increasingly visible (Dimitrova & Wunsch, Citation2020). Such effects appear particularly relevant for the EU, which is already suffering from shaken credibility in candidate and neighbourhood countries and is likely to see its efforts to promote democratic reforms further undermined by the several member states’ failure to live up to the democratic standards they agreed to maintain upon accession.

In sum, whereas we find little immediate indication that democratic backsliding is driving broader efforts by PRR forces inside the EP to contest the European project at large, we nonetheless consider that the deepening and spread of democratic and rule of law violations in EU member states warrants further research on the potential impact of democratic backsliding on EU-level cooperation. Our study provides a first attempt to tease out these interactions and proposes several future avenues of research to expand upon this effort.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (364.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Caterina Froio, Emiliano Grossman, Seán Hanley, Mila Mikalayeva, Jan Rovny, Olivier Rozenberg, Frank Schimmelfennig, Matthias Thiemann and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We thank Louise Seyfried for her research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mihail Chiru

Mihail Chiru is Departmental Lecturer at the University of Oxford.

Natasha Wunsch

Natasha Wunsch is Assistant Professor at Sciences Po and Senior Researcher at ETH Zurich.

Notes

1 MEPs’ voting behaviour on democratic backsliding resolutions has received more attention recently, but the focus has been either a small number of votes (Meijers & van der Veer, Citation2019a) or a single EPG (Herman et al., Citation2021).

References

- Almeida, D. (2010). Europeanized Eurosceptics? Radical right parties and European integration. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11(3), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2010.503031

- Anghel, V. (2020). Together or apart? The European Union’s East–West divide. Survival, 62(3), 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2020.1763621

- Bartolini, S. (2005). Restructuring Europe: Centre formation, system building and political structuring between the nation-state and the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Bayer, L. (2020, August 7). Illiberal European bloc says Westerners shouldn't lecture Easterners. Politico. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from https://www.politico.com/news/2020/07/08/illiberal-european-leaders-say-westerners-shouldnt-lecture-easterners-352909

- Bélanger, M.-È., & Wunsch, N. (2021). From cohesion to contagion? Populist radical right contestation of EU enlargement. Journal of Common Market Studies. Advance online publication.

- Bergmann, J., Hackenesch, C., & Stockemer, D. (2021). Populist radical right parties in Europe: What impact do they have on development policy? Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13143

- Brack, N. (2017). Opposing Europe in the European Parliament: Rebels and Radicals in the Chamber. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brack, N., & Costa, O. (2019). Parliamentary questions and representation of territorial interests in the EP. In O. Costa (Ed.), The European Parliament in times of EU crisis: Dynamics and transformations (pp. 225–254). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brack, N., & Startin, N. (2015). Introduction: Euroscepticism, from the margins to the mainstream. International Political Science Review, 36(3), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512115577231

- Braun, M. (2020). Postfunctionalism, identity and the visegrad group. Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(4), 925–940. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12994

- Braun, D., Hutter, S., & Kerscher, A. (2016). What type of Europe? The salience of polity and policy issues in European Parliament elections. European Union Politics, 17(4), 570–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116516660387

- Caiani, M. (2018). Radical right cross-national links and international cooperation. In J. Rydgren (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the radical right (pp. 394–411). Oxford University Press.

- Cavallaro, M., Flacher, D., & Zanetti, M. A. (2018). Radical right parties and European economic integration: Evidence from the seventh European Parliament. European Union Politics, 19(2), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518760241

- Chiru, M., & Stoian, V. (2019). Liberty: Security dilemmas and party cohesion in the European Parliament. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(5), 921–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12852

- de Vries, C. (2018). Euroscepticism and the future of European integration. Oxford University Press.

- Dimitrova, A., & Wunsch, N. (2020, June 10). Competing Diffusion Forces and Domestic Elites: How the Rise of Authoritarianism Undermines International Democracy Promotion. Paper presented at the ECPR SGEU conference.

- Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2021). Parliaments and governments database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies. http://www.parlgov.org/static/data/

- Enyedi, Z. (2016). Populist polarization and party system institutionalization. Problems of Post-Communism, 63(4), 210–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2015.1113883

- EurActiv. (2020, November 18). Slovenia PM backs Hungary, Poland in EU rule of law row. EurActiv. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.euractiv.com/section/all/news/slovenia-pm-backs-hungary-poland-in-eu-rule-of-law-row/

- Falkner, G., & Plattner, G. (2020). EU policies and populist radical right parties' programmatic claims: Foreign policy, anti-discrimination and the single market. Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(3), 723–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12963

- Herman, L. E., Hoerner, J., & Lacey, J. (2021). Why does the European right accommodate backsliding states? An analysis of 24 European People’s Party votes (2011–2019). European Political Science Review, 13(2), 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000023

- Hix, S., & Høyland, B. (2014). Political behaviour in the European Parliament. In S. Martin, T. Saalfeld, & K. Strøm (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of legislative studies (pp. 591–608). Oxford University Press.

- Høyland, B. (2010). Procedural and party effects in European Parliament roll-call votes. European Union Politics, 11(4), 597–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510379925

- Iusmen, I. (2015). EU leverage and democratic backsliding in central and Eastern Europe: The case of Romania. Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(3), 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12193

- Kantola, J., & Lombardo, E. (2020). Strategies of right populists in opposing gender equality in a polarized European Parliament. International Political Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120963953

- Kelemen, R. D. (2020). The European Union's authoritarian equilibrium. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1712455

- McDonnell, D., & Werner, A. (2018). Respectable radicals: Why some radical right parties in the European Parliament forsake policy congruence. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(5), 747–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1298659

- McDonnell, D., & Werner, A. (2019a). Differently Eurosceptic: Radical right populist parties and their supporters. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(12), 1761–1778. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1561743

- McDonnell, D., & Werner, A. (2019b). International populism: The radical right in the European Parliament. Hurst & Company.

- Meijers, M., & van der Veer, H. (2019a). MEP responses to democratic backsliding in Hungary and Poland. An analysis of agenda-setting and voting behaviour. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(4), 838–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12850

- Meijers, M., & van der Veer, H. (2019b). Issue competition without electoral incentives? A study of issue emphasis in the European parliament. The Journal of Politics, 81(4), 1240–1253. https://doi.org/10.1086/704224

- Mudde, C. (2010). The populist radical right: A pathological normalcy. West European Politics, 33(6), 1167–1186. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2010.508901

- Müller, J.-W. (2015). Should the EU protect democracy and the rule of law inside member states? European Law Journal, 21(2), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12124

- Pirro, A. L. P., Taggart, P., & van Kessel, S. (2018). The populist politics of Euroscepticism in times of crisis: Comparative conclusions. Politics, 38(3), 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395718784704

- Politico. (2021, July 2). Orbán, Le Pen, Salvini join forces to blast EU integration. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://www.politico.eu/article/viktor-orban-marine-le-pen-matteo-salvini-eu-integration-european-superstate-radical-forces/

- Proksch, S.-O., & Slapin, J. B. (2011). Parliamentary questions and oversight in the European Union. European Journal of Political Research, 50(1), 53–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01919.x

- Rappold, J., & Wunsch, N. (2019). Keine Entwarnung nach der Europawahl: der Einfluss EU-skeptischer Kräfte geht über das Europäische Parlament hinaus. DGAPkompakt 12.

- Rooduijn, M., van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., Lange, S. de, Halikiopoulou, D., Lewis, P., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2019). The PopuList: An overview of populist, far right, far left and Eurosceptic parties in Europe. www.popu-list.org

- Schmitt, H., Braun, D., Popa, S. A., Mikhaylov, S., & Dwinger, F. (2018). European parliament election study 1979-2014. Euromanifesto Study.

- Sedelmeier, U. (2017). Political safeguards against democratic backsliding in the EU: The limits of material sanctions and the scope of social pressure. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(3), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1229358

- Startin, N. (2010). Where to for the radical right in the European Parliament? The rise and fall of transnational political cooperation. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11(4), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2010.524402

- Theuns, T. (2020). Containing populism at the cost of democracy? Political vs. economic responses to democratic backsliding in the EU. Global Justice: Theory Practice Rhetoric, 12(2), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.21248/gjn.12.02.220

- Usherwood, S., & Startin, N. (2013). Euroscepticism as a persistent phenomenon. Journal of Common Market Studies, 51(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02297.x

- Vachudova, M. (2019). From competition to polarization in central Europe: How populists change party systems and the European Union. Polity, 51(4), 689–706. https://doi.org/10.1086/705704

- Vasilopoulou, S. (2013). Continuity and change in the study of euroscepticism: Plus ça change?*. Journal of Common Market Studies, 51(1), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02306.x

- Whitaker, R., & Lynch, P. (2014). Understanding the formation and actions of Eurosceptic groups in the European Parliament: Pragmatism, principles and publicity. Government and Opposition, 49(2), 232–263. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2013.40