ABSTRACT

Cross-country variation in the outcomes of public sector wage-setting (PSWS) persists in Europe. Received wisdom from the neo-corporatist scholarship attributes it to the presence/absence of centralized or co-ordinated wage-setting regimes. This article challenges the conventional view by analysing PSWS through the lens of the common-pool problem of public finance and special-interest politics. Given the structure of political incentives and the use of fiscal money by public employers, PSWS tends to be inherently inflationary. Yet, the article posits that the extent to which wage inflation occurs in the public sector hinges on the institutional properties of PSWS governance systems. Systematic wage restraint occurs within systems where PSWS authority is delegated to a state actor – either the Finance Ministry or an independent agency – with an organizational mandate and powers to ensure PSWS be conducted in the general interest rather than in response to public sector groups’ narrow interests. The argument is demonstrated by leveraging an original combination of most-similar and most-different case studies combined with archival research and elite interviews. The findings advance our understanding of the political economy of wage restraint in Europe and highlight the key role state actors and institutional structures play within growth regimes.

Introduction

While steady public sector expansion went undisputed during Europe’s Trente Glorieuses (Rose et al., Citation1985), since the 1980s there has been a major shift from the active Keynesian state to New Public Management (NPM) and regulatory governance (Hood, Citation1995; Majone, Citation1994). Central to this shift was the need to install the market mechanism into public sector employment relations, hitherto mainly subjected to public law status (Bach et al., Citation1999). Moreover, due to falling growth/productivity rates and intensifying austerity pressures (Pierson, Citation1996), governments have begun containing public sector wage growth to shore up public finances and ensure competitiveness in global markets (Oxley & Martin, Citation1991). Despite these common challenges, however, states have not converged toward the neoliberal night-watchman state (Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2011) and public sector wage-setting systems remain hardwired into the state’s path-dependent legal and administrative systems (Bach & Bordogna, Citation2011). As a result, cross-country variation in the outcomes of public sector wage-setting (PSWS) persists in Europe: some countries feature expansionary public sector wage trajectories while others systematic wage restraint (Holm-Hadulla et al., Citation2010; Müller & Schulten, Citation2015). How do we account for cross-country variation in PSWS outcomes across Western Europe?

Drawing on classic neo-corporatist theory, scholars have largely treated PSWS as a problem of inter-sectoral wage co-ordination between exporting and sheltered sectors (Garrett & Way, Citation1999; Hancké, Citation2013; Johnston, Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2016; Traxler & Brandl, Citation2010). The literature maintains that restrictive/expansionary PSWS depends on the presence/absence of neo-corporatist wage bargaining regimes, which constrain public sector unions’ capacity to extract inflationary wage increases due to centralized or co-ordinated wage-setting institutions.

These insights remain important today. However, this article questions their applicability to PSWS by showing that neo-corporatist institutions are neither necessary nor sufficient institutional prerequisites for public sector wage restraint. Hence, by borrowing insights from public economics scholarship, I advance a new state-centred theoretical framework for the study of PSWS. Instead of the wage co-ordination problem, I highlight the fiscal nature of PSWS, which I analyse through the lens of the classic common-pool problem of public finances (Von Hagen & Harden, Citation1995) and special-interest politics (Persson & Tabellini, Citation2016). Thus, I contend that cross-country variation is better explained by variation in the institutional configuration of PSWS governance systems, which minimize the scope for special-interest politics in PSWS differently across countries.

PSWS is in fact fundamentally different from private sector wage-setting due to the common-pool problem. Public wages are funded by political employers spending general taxpayers’ money on benefits targeted to a specific social group: the public employees. This gives rise to special-interest politics: public sector narrowly-based interest groups are well-organized and have clear incentives to act as ‘distributional coalitions’ (Olson, Citation1986) to appropriate the maximum share of public resources in PSWS. Since the conflict of interest between ‘capital’ and labour is absent in the provision of not-for-profit public services, political employers have strong incentives to grant generous wage increases in exchange for public employees’ votes and public sector unions’ political support. Given this inherently inflationary structure of incentives in PSWS, I investigate the conditions under which wage restraint emerges in the public sector.

Through a combination of most-similar (France and Italy) and most-different (Germany and Portugal) case studies – and a shadow case (Greece, presented in online Appendix II) – the article demonstrates that public sector wage restraint occurs within PSWS systems where key powers are delegated to a state actor with an institutional mandate to ensure wage policy be adopted in the collectivity’s general interest as opposed to being responsive to special-interest politics. I identify three models of authority delegation conducive to wage restraint in PSWS: direct, indirect and external delegation. In PSWS systems characterised by direct delegation, wage restraint occurs because PSWS authority is centralized under the remits of the finance ministry – the bulwark of the state’s fiscal responsibility. Similarly, within models of indirect delegation, the finance ministry oversights PSWS by holding agenda-setting and/or veto powers in PSWS. Under external delegation, PSWS authority is instead delegated to an independent state agency with a mandate and powers to ensure ‘de-politicized’ PSWS. Systems characterized by the lack of institutionalized delegation in PSWS are instead conducive to volatile cycles of wage expansion and restraint, depending on governments’ budgetary resources.

The article makes three contributions to comparative political economy scholarship. First, it advances the established literature on the political economy of wage restraint in Europe. It shows that, differently from standard assumptions held in neo-corporatist scholarship, PSWS is independent from the dominance of export-sector interests and co-ordination institutions. Hence, PSWS should be studied for its own sake; it also yields broader insights into the study of countries’ fiscal policymaking and distributive politics. Second, the article advances our understanding of states’ role as public employers. It shows that states are neither neutral industrial relations actors – captured by export-sector interests – nor monolithic blocs. Rather, state actors can actively define economic policy choices independently of social groups. Third, the article points at the importance of states’ institutions and practices for structuring state actors’ policy choices with noteworthy implications for countries’ growth strategies (Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2016; Hassel & Palier, Citation2021).

The argument develops as follows. In Section Two, I discuss the shortcomings of the neo-corporatist approach. In Section Three, I present the alternative state-centred theoretical framework to then discuss, in Section Four the logic of case selection. In Section Five, I present the comparative case studies and then conclude by discussing briefly the importance of PSWS for burgeoning debates on growth models.

Neo-corporatism: the institutional pre-conditions for public sector wage restraint

The study of PSWS has loosely concerned three different literatures. Labour economists tend to focus on estimating the wage gap between public and private sector employees in comparable professions (Lucifora & Meurs, Citation2006; Postel-Vinay, Citation2015). Industrial relations experts study public sector employment regimes and provide insightful descriptions of the legal and institutional features of PSWS systems together with the patterns of institutional change over time (Bach et al., Citation1999; Bach & Bordogna, Citation2018). To my knowledge, it is mostly the structuralist variantFootnote1 of the neo-corporatist scholarship that has investigated the determinants of PSWS (Crouch, Citation1990; Garrett & Way, Citation1999; Traxler & Brandl, Citation2010).

Neo-corporatist studies have shown that a country’s capacity for wage restraint depends on the presence of particular institutional prerequisites, i.e., centralized or co-ordinated wage bargaining regimesFootnote2 (Scharpf, Citation1991; Soskice, Citation1990). In the former, encompassing unions are forced to moderate their wage claims within confederal agreements because expansionary wage policy across-the-board generates inflation spillovers, thereby jeopardizing their members’ purchasing power and export-sector jobs. In the latter, wage restraint pursued by the export-sector – interested in international cost-competitiveness – is imposed on sheltered sectors through mechanisms of inter-sectoral co-ordination.

Drawing on this logic, scholars have thus argued that cross-country variation in PSWS outcomes hinges on the presence of neo-corporatist wage bargaining regimes preventing public sector unions from extracting ‘unmerited wage increases’ (Johnston, Citation2012). These institutional regimes range from pattern bargaining systems of inter-sectoral co-ordination (e.g., Germany), to centralized incomes policies (Finland) and export-oriented wage co-ordination by the state (France) (Hancké, Citation2013; Johnston, Citation2016; Johnston & Hancké, Citation2009). At closer scrutiny, however, neo-corporatist wage bargaining regimes appear neither necessary nor sufficient institutional conditions for public sector wage restraint. To see why, consider these observations.

Germany is the most representative case of inter-sectoral wage co-ordination through pattern bargaining. Yet, recent scholarship has disproven this thesis (Di Carlo, Citation2020) and has shown that public sector wage restraint was instead part of a broader strategy of fiscal consolidation during Germany’s fiscal crisis at the turn of the century (Di Carlo, Citation2019). Therefore, although pattern bargaining may be sufficient to generate public sector wage restraint in theory, it becomes unnecessary when governments face budgetary problems. This is, in fact, the lesson learned after the Eurozone crisis when – regardless of neo-corporatist institutions – virtually all European governments imposed fiscal austerity through freezes/cuts in public sector wages via their legislative powers (Bach & Bordogna, Citation2018; Vaughan-Whitehead, Citation2013).

Moreover, consider the Irish and Italian experiences during the Eurozone’s first decade. Ireland had for long time institutionalized a centralized wage-setting regime based on social partnership (Regan, Citation2012). During the 1990s, Italy had recentralized wage-setting in a neo-corporatist fashion (Regalia & Regini, Citation1998). Yet, both countries experienced a marked trajectory of public sector-specific inflationary wage growth (Müller & Schulten, Citation2015). Hence, neo-corporatist institutions seem insufficient to ensure public sector wage restraint if the government is willing to pursue expansionary PSWS.

In all, neo-corporatist accounts of PSWS seem excessively focused on the institutional structures that best constrain sheltered sector unions’ ‘rent-seeking’ behaviour. While insightful, this approach overlooks that PSWS is fiscal policy enacted by political employers (Beaumont, Citation1992). In PSWS the government ‘occupies two seats at the table’ (Hyman, Citation2013). It represents management but it is also the state’s political and fiscal authority with the sovereign capacity to impose its preferences unilaterally (Traxler, Citation1999). In fact, even where collective bargaining exists in PSWS, negotiations always occur under a ‘shadow of hierarchy’ (Scharpf, Citation1997) because the state maintains the ultimate power to enforce its ‘will’ unilaterally and does not require neo-corporatist institutional prerequisites.

The relevant puzzle in the political economy of PSWS thus becomes why governments fail to pursue restrictive PSWS despite having the powers to do so. This behoves us to make sense of PSWS’s sui generis nature.

Beyond neo-corporatism: the special-interest politics of public sector wage-setting

The special-interest politics of PSWS

Moving beyond the neo-corporatist approach, this article posits that PSWS is better comprehended as fiscal policymaking characterized by the classic common-pool problem of public finance. The core of fiscal policymaking in democracy is that politicians receive a mandate from voters to spend other people’s money. The common-pool problem arises anytime politicians spend general taxpayers’ money on policies which are, instead, targeted to specific groups of beneficiaries (Hallerberg et al., Citation2007). Since the costs of funding these policies are diffused – i.e., paid by all the taxpayers – while the benefits are concentrated – i.e., enjoyed only by the group members –, a mismatch emerges between those who pay for public policy and those who benefit from it. In other words, while a targeted group (e.g., the public sector employees) internalizes the full benefits of spending bids (e.g., on public sector wage increases), the additional burden on the public budgets is externalized onto the collectivity.

This divergence in public spending’s net benefits appropriation leads to budgetary expansion and excessive spending due to special-interest politics: narrow-interest groupsFootnote3 and the politicians representing them have clear incentives to expand spending bids to appropriate the maximum amount of societal resources from the common pool while bearing only limited direct costs (Persson & Tabellini, Citation2016; Ch. 7). Fiscal spending for PSWS is particularly prone to special-interest politics because it shares the characteristics of club goods (i.e., excludability and non-rivalry) which make it highly effective for redistributing resources from the collectivity to the targeted social groups, as characteristic of clientelist exchanges (Hicken, Citation2011; Kitschelt & Wilkinson, Citation2007).

In extreme cases – e.g., Greece – politicians may unashamedly exchange public sector wage increases and benefits for clientelist political support by public sector employees and unions (Trantidis, Citation2016). But politicians’ use of public money in PSWS implies the in-built logic of budgetary/wage expansion in PSWS remains, even in the absence of clientelism. In fact, it is perfectly rational for office-seeking politicians to prefer expansionary public sector wage policies, for two reasons. First, the conflict of interest between ‘capital’ and labour is absent in the not-for-profit provision of public goods and services, which are not for sale. Second, wage restraint imposes direct and visible costs to a large constituency with high sanctioning capacity. In fact, differently from the private sector, public employees can sanction their employers at the ballot box while well-organized trade unions can disrupt the provision of public goods,Footnote4 causing a broader backlash against the government. Arguably, given the large size of today’s public sectors, public sector employees remain a hefty electoral constituency political entrepreneurs cannot easily afford to alienate (Beramendi et al., Citation2015).

Hence, PSWS tends to be expansionary as a result of a ‘political exchange’ (Pizzorno, Citation1978) between politicians in government and the public sector workers/unions. Expansionary PSWS then creates negative fiscal and inflation externalities (Calmfors, Citation1993). Expansionary PSWS induces higher debt/taxes or cuts in other types of public expenditures and generates inflation spillovers that worsen the country’s terms of trade, eliciting internal or external devaluations (Johnston, Citation2011; Johnston et al., Citation2014). By exchanging political support for generous wage increases, both politicians and public sector groups internalize the full benefits of fiscal spending for PSWS while externalizing its costs on society. However, the extent to which these dynamics occur varies across systems of PSWS governance.

Limiting the common pool problem: the three models of delegation in public sector wage-setting

Public economics scholarship shows that fiscal policy’s deficit bias due to the common-pool problem can be mitigated by specific state institutions governing budgetary decisions. Thus, cross-country variation in fiscal policy hinges on variation in the formal and informal rules constraining politicians’ opportunistic pursuit of special-interest politics (Poterba & Von Hagen, Citation1999). Among others, the institutional configuration of relevance here is the delegation of authority in the adoption of budgetary policy to a state actor – either within or outside the executive – with a mandate to ensure the soundness of public finances. The literature envisages two models of delegation: the centralization of strategic powers in budgetary policymaking within a strong finance ministry insulated within the executive (Von Hagen, Citation2008) and the delegation of policy authority to independent fiscal agencies outside the executive (Debrun, Citation2011; Wyplosz, Citation2005).

The delegation of powers aims to ensure responsible budgetary decisions be taken in the general interest rather than in response to narrow groups’ demands. The common-pool problem is minimized by centralizing the authority on budgetary decisions within a state unit with an organizational mandate to guarantee sound public finances, i.e., the Finance Ministry whose officials’ careers and credibility hinge on their success in enforcing restrictive budgetary policies (Jochimsen & Thomasius, Citation2014; Moessinger, Citation2012). Delegation involves the centralization of policy authority within the finance ministry or the institutionalization of agenda-setting, monitoring and/or veto powers during the budgetary process. Centralization refers not only to the locus where decisions are taken, but also to the capacity of the finance ministry to overcome competing claims on the public purse by politicians or other units of the public administration. Deviations from this model result in fragmented budgetary decisions, which tend to generate larger deficits. This occurs, for instance, when policymakers other than the finance ministry (e.g., in spending ministries or in subnational governments) can use off-budget funds for spending bids targeted at narrow groups without being challenged by the central budgetary authority, or when the finance ministry lacks the formal capacity to impose its agenda or veto budgetary decisions in the executive (Von Hagen, Citation2008).

In the second delegation model, the authority to adopt budgetary policies is outsourced to an independent, yet accountable, state agency disposing of the necessary fiscal resources to achieve its mandate’s goals. Delegation to non-majoritarian institutions has become widespread in monetary policymaking with the rise of independent central banks (McNamara, Citation2002) as well as in the regulation of economic sectors requiring high technical competences (Thatcher & Sweet, Citation2002). However, due to the highly salient and distributive nature of budgetary decisions, no such agencies exist in fiscal policymaking (Debrun, Citation2011).

Given the fiscal nature of PSWS, these insights dovetail with extant literature on public sector wage-setting regimes highlighting the important role finance ministries and independent wage-setting agencies play in PSWS (Bordogna, Citation2007; Ozaki, Citation1987). I thus theorize three equivalent models of authority delegation designed to limit the pursuit of special-interest politics in PSWS (see ).

Table 1. Models of authority delegation in PSWS conducive to public sector wage restraint.

In the first model, i.e., direct delegation, the conduct of PSWS is centralized under the authority of the finance ministry, which acquires the direct competence for wage negotiations (if collective bargaining exists) or unilateral wage determination. Here, the conflict of interest between public management and employees is reinstated ‘artificially’ by delegating PSWS powers to a state actor with a vested interest in ensuring the conduct of fiscally responsible wage policies in contrast to elected officials’ temptation to be responsiveFootnote5 to public sector groups’ demands.

In the second model, indirect delegation, the finance ministry lacks the competence for wage determination but oversights PSWS by holding formal strategic powers to set ex ante budgetary limits for aggregate spending on PSWS and/or to veto decisions deviating from them.

In the third model, external delegation, PSWS authority is outsourced to an extra-governmental actor, i.e., an independent state agency with a legal mandate to negotiate and/or set wage policy according to ‘objective’ parameters (e.g., inflation targets or private sector wage comparators), thus substituting political decision-makers in PSWS (Ozaki, Citation1987). Here, however, the mandate must grant the agency funding authority to disburse fiscal resources for PSWS autonomously. Otherwise, when agencies have only bargaining competences, but politicians control the fiscal resources for PSWS, there remains scope for special-interest politics because wage policy can be expanded by enlarging fiscal funding through additional spending bids, as the Italian case demonstrates (see Section 5.2).

The remainder of the article is geared towards testing the following theoretical expectation:

public sector wage restraint occurs systematically within wage-setting systems where policy authority over PSWS is delegated directly to the finance ministry – or an independent state agency with funding authority – or where the finance ministry oversights PSWS by formally holding the authority to set ex ante budgetary limits to fiscal aggregates for PSWS and/or veto decisions over PSWS.

Logic of case selection

The outcomes to be explained are operationalized as two alternative trajectories of PSWS: expansionary versus restrictive. Expansionary/restrictive wage policies depend on whether real wage growth in the public sector systematically outstrips/lags total labour productivity in the economy. Such operationalization is derived from macroeconomics scholarship (Marglin & Schor, Citation1992) and is generally accepted as a benchmark for wage policies because real wage growth in line with labour productivity ensures a stable wage share in the economy while simultaneously keeping up workers’ purchasing power and preventing wage-setting inflation spillovers.

Based on most-similar and most-different systems designs (Gerring, Citation2006), I selected two case-study pairs (see ) plus a shadow case (presented in online Appendix II). France and Italy are most-similar cases sharing weak neo-corporatist structures, pluralist systems of interest representation and other important similarities. Yet, the French state systematically pursues restrictive public sector wage policies thanks to indirect delegation of PSWS authority to the finance ministry. Italy, instead, suffers inflationary cycles of PSWS because incomplete delegation of PSWS authority allows for the recurrent pursuit of special-interest politics in times of good fiscal conditions. Germany and Portugal are most-different cases that, despite substantial institutional differences, feature public sector wage restraint thanks to direct and indirect delegation of PSWS authority to finance ministers. The Greek shadow case is presented in the online appendix II to further corroborate the argument that, similar to Italy, the lack of delegation of PSWS authority is conducive to inflationary cycles in good times.

Table 2. Institutional characteristics of the cases selected for the comparative analysis.

The empirical analysis relies on the triangulation of descriptive statistics, secondary sources from two historical archives (see Table 1, online Appendix I) and elite interviews with decision-makers involved in PSWS processes (see Table 2, online Appendix I).

The state-centred political economy of public sector wage-setting in Western Europe

France: from dirigisme to competitive disinflation ‘in the shadow of hierarchy’

France features a centralized system of indirect delegation of PSWS authority based on strong agenda-setting and veto powers governed by the ministry of finance. Collective bargaining in the public sector was introduced in 1983 but agreements lack legal status and do not bind the government (Mossé & Tchobanian, Citation1999). Thus, PSWS occurs in the shadow of hierarchy: the government sets wage policy unilaterally when unions fail to accept the conditions set by the finance ministry. The state is represented in wage negotiations by the civil service minister. But the minister of finance sets ex ante the budgetary margins within which the minister operates, monitors the bargaining process and holds a formal veto on all decisions related to the civil service (Document 1). The strength and autonomy of the finance ministry is further enhanced by the appointment of an independent senior civil servant as head of the central budget authority. Differently from Italy and Greece, where this figure is a political appointee, the civil servant responsible for the central budget in France is neither changed nor reconfirmed when the government changes (OECD, Citation2012).

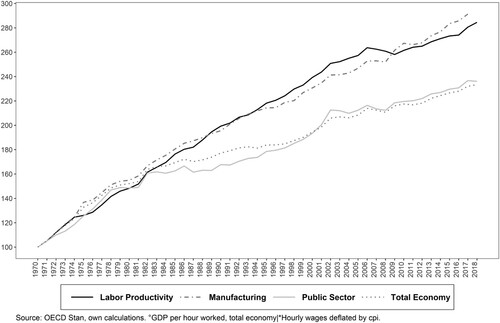

shows that such regime is conducive to systematic restraint in PSWS. The figure also points at 1982 as the starting point of this trajectory. This is no coincidence; this governance regime was purposefully engineered by the then Finance Minister Jacques Delors as a central component of the shift from dirigisme to competitive fiscal/wage disinflation in the European Monetary System (EMS) (Document 2).

Figure 1. France. Real* hourly wages in selected sectors and total labour productivity° (Indexes, 1970 = 100).

Economic governance in France is led by an insulated and hierarchical bureaucracy (Zysman, Citation1977) coordinated by the Treasury, the authority ultimately responsible for the country’s macroeconomic governance (Hall, Citation1994). In fact, the finance ministry has historically been the ultimate source of power over the direction of the French economy (Eck, Citation1986). In the post-war period, the French dirigiste state steered economic development via industrial policies (Hall, Citation1986; Shonfield, Citation1965; Zysman, Citation1984), deficit spending and lax monetary policy whose inflationary effects were counteracted via competitive devaluations (Levy, Citation2005). With the collapse of Bretton Woods and growing economic integration, inflationary fiscal policies became ineffective and inflation-importing devaluations problematic (Hall, Citation1994). In the 1970s, conservative liberals – dominant in the ministry of finance, the Bank of France and the grand corps – embraced Germany’s model of monetary and fiscal stability and backed Prime Minister Raymond Barre’s initiative to take France into the European Monetary System (EMS). Participation in the EMS – and the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) later – in turn reinforced the finance ministry’s clout over economic policy (Howarth, Citation2001).

In 1981, the strategy of redistributive Keynesian expansion attempted by Mitterrand’s socialist government failed under speculative pressures against the Franc. Mitterrand’s decision to keep France in the EMS led to a shift in economic policymaking from dirigisme to competitive disinflation and a strong currency (franc fort) through public deficit reduction, wage discipline and reforms to reduce the government’s scope in the economy (Amable et al., Citation2012; Lordon, Citation1998).

In industrial relations, the French state has historically played a central role to compensate for social partners’ weakness and fragmentation. Failed attempts to nurture the social partners induced extensive state regulation of labour markets and social protection (Howell, Citation2011). But, while the Auroux Laws fostered private sector wage-setting decentralization and employment flexibility in the 1980s, in the public sector the state moved in the opposite direction: the finance ministry stepped up its unilateral governance of PSWS, imposing restrictive wage policies as the central component of competitive disinflation.

Until the 1970s, it had been unusual for the French government to resort to incomes policies. Under normal circumstances, an index point (point d’indice) was used to adjust the wages of French public employees, indexing growth to changes in the consumer price index (Document 3). In 1982, Finance Minister Jacques Delors devised the reform of the indexation system by anchoring wage increases to a future inflation rate targeted by the finance ministry (Document 3). Concomitantly, the finance ministry froze incomes for one year through an emergency act without parliamentary debate (Document 4). The deindexation of pay and the state’s unilateral determination of PSWS were hailed as such a success that Finance Minister Balladur, under Chirac’s new conservative government, imposed another unilateral public sector pay freeze in 1986 (Document 5) and very moderate wage increases in 1987 (Document 6) and in 1988 (Document 7), despite inflation running high. Throughout the 1990s, the finance ministry continued the path of rigueur in PSWS, imposing pay freezes or very moderate increases below inflation (Document 8). With the advent of EMU, the strategic governance of PSWS has remained key to ensuring wage restraint. Thus, for instance, the government imposed moderate wage increases in both 2001 and 2002 (Document 9). When the financial crisis hit, the government again froze wages unilaterally to curtail budget deficits (Bordogna & Pedersini, Citation2013).

In all, the French system of PSWS governance, structured around the indirect delegation of PSWS authority to the finance ministry, has resulted in a steady trajectory of real wage growth below productivity. This has been key to supporting the strategy of competitive disinflation throughout the process of European monetary integration.

Italy: from clientelism to technocratic disinflation, and back

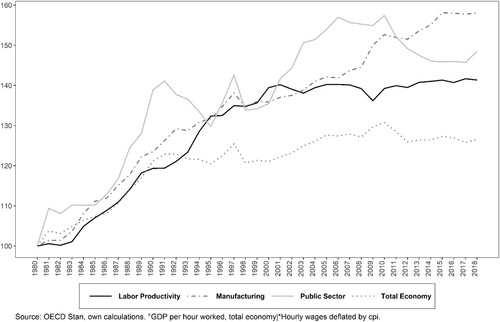

Italy features a system of PSWS governance characterized by incomplete delegation to an independent state agency. This peculiar system leads to volatile wage-setting outcomes (). Cycles of opportunistic wage expansions during times of fiscal bonanza (1980s & 2000s) give way to unilateral wage cuts in hard times when technocratic governments become empowered by external constraints (1990s & 2010s).

Figure 2. Italy. Real* hourly wages in selected sectors and total labour productivity° (Indexes, 1980 = 100).

In Italy, the public sector has historically been used strategically by politicians; the bureaucracy has long been captured by the political parties that ruled the first republic (1948–1994) (LaPalombara, Citation1966; Ranci, Citation1987). Public employment was expanded strategically to absorb the mass of unemployed, especially in the backward South (Santoro, Citation2014). Uniform national wage increases have served to distribute fiscal resources to the public sector constituency in the South, where living costs are much lower compared to the North (Alesina et al., Citation2001). In PSWS, virtually all parties had their public sector clienteles to which they granted wage increases as handouts ad hoc (Ricciardi, Citation2010; Santagata, Citation1995). By the 1980s, clientelist PSWS had reached a point that it jeopardized unity within the trade union confederations: confederal leaders could no longer justify these privileges to workers in exposed manufacturing sectors where these opportunistic choices could not be replicated (Interviews 2, 3).

As a result, union leaders started to ask the government to ‘privatise’ public sector employment relations and ‘de-politicize’ PSWS (Interviews 2, 3). The signing of the Maastricht Treaty, the crisis of the Italian Lira in 1992 and the Bribesville political scandal all forced budgetary restraint and ushered in a series of institutional reforms (Ferrera & Gualmini, Citation2004). During 1993, the Ciampi technocratic government reformed the wage-setting regime together with the social partners to introduce a centralized wage-bargaining system. Wages were negotiated by the social partners at the sectoral level but centralization was to be achieved by targeting the expected inflation rate agreed with the social partners in the yearly budget law. A second pillar then allowed for decentralized wage increases based on local productivity levels (Bordogna et al., Citation1999). Collective bargaining was extended to most public sector employees, who lost their public law status as civil servants. The representation of the state in PSWS was delegated to an independent agency (ARAN)Footnote6 with the aim of ensuring wage moderation within a system hitherto plagued by clientelism. Public sector wage freezes were imposed by the technocratic government and wage moderation followed throughout the 1990s (Dell’Aringa, Citation1997), not least because of a general consensus on the need to join the EMU (Regalia & Regini, Citation1998).

Special-interest politics returned under Silvio Berlusconi’s centre-right coalition and is symptomatic of the broad-ranging flaws of incomplete delegation of PSWS authority. Aided by deputy Prime Minister Gianfranco Fini, Berlusconi orchestrated political exchanges with the unions to sabotage ARAN’s newly established independent role in PSWS.

Under the new system, ARAN was mandated to negotiate with the trade unions during the biannual renewals of the collective agreements. However, the government had kept the power to establish the budgetary resources for PSWS. De facto, this implied that the government earmarked fiscal resources for PSWS in the budget laws preceding ARAN’s negotiations with the unions. ARAN’s mandate simply consisted in negotiating how to distribute resources across the various public sector compartments (Talamo, Citation2009). Thus, unions knew the quantum of government funding before wage negotiations started and, by refusing to sign collective agreements, shifted negotiations back to the political arena. In other words, they used the earmarked resources as wage floors to bid up and lobbied their political referents to expand fiscal funds for PSWS in the next budget law (Interviews 3, 4, 5).

Ahead of the 2002–2003 round, for instance, the government had earmarked resources equivalent to a 4.5 per cent increase against unions’ demand for 6 per cent (Document 10). The unions refused to enter negotiations with ARAN and called for various public sector strikes. At the time, Berlusconi had enraged the left-leaning CGILFootnote7 trade union confederation by launching a labour market liberalization programme, which led to sizeable strikes. To divide the unions and prevent a general backlash against the government’s agenda, Berlusconi urged a political mediation by Gianfranco Fini where more generous wage increases were to be exchanged for political support by the centrist CISLFootnote8 trade union confederation. In fact, Fini’s political party (Alleanza Nazionale) had found its main electoral constituency in the public employees – especially rooted in Southern Italy – and maintained strong ties with the CISL as the most representative organization in the public sector (Baglioni, Citation2011). Thus, Fini met privately with CISL’s leader Savino Pezzotta during winter 2002 (Interview 6) and worked out an agreement to increase the fiscal endowments for PSWS (Interview 7). Eventually, the government met the trade unions' demands, enlarging resources in the subsequent budget law, and then mandated ARAN to sign the collective agreements (Document 11). The CGIL remained isolated in demonstrating against the government and the labour reform passed at the end of 2002 (Document 12).

A similar dynamic of political exchange occurred in the following 2004–2005 bargaining round when unions opposed the government’s initial offer, circumvented ARAN and, again, obtained generous wage increases thanks to Fini’s political mediation with the CISL (Di Carlo, Citation2018). However, the Finance Minister Giulio Tremonti strongly opposed expensive public sector wage increases. Repeated confrontations between the two led Tremonti to eventually resign due to Berlusconi’s support for the public sector cause before the European elections (Interview 6).

Simultaneously, expansionary wage growth occurred also at the decentralized level where local administrations increasingly made use of off-budget funds as top-ups over the national agreements (Bordogna, Citation2002). Decentralized and fragmented PSWS, beyond the reach of a central budgetary authority, resulted in further inflation spillovers, which contributed to expansionary PSWS in the mid-2000s (ARAN, Citation2007).

In all, despite the attempted de-politicization of PSWS, incomplete delegation in the Italian system has left scope for the return of special-interest politics during good times. However, similar to the 1990s, after Italy’s sovereign debt crisis finance ministers have had to rectify previous excesses through a series of unilateral freezes/cuts (Bordogna & Pedersini, Citation2013).

Germany: from centralization to organized-decentralization

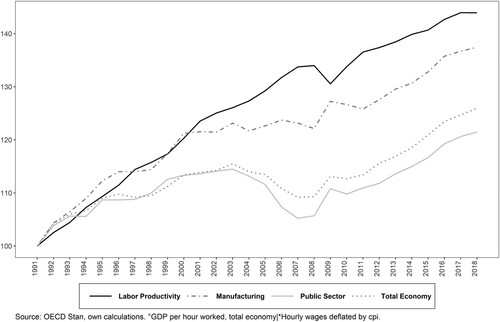

Germany’s federal polity features a hybrid system of PSWS governance where direct and indirect delegation of key PSWS powers to finance ministers occurs at various state levels. shows this model to be conducive to systematic public sector wage restraint. However, the peculiar trajectory of remarkable public sector restraint must be understood also considering Germany’s post-reunification fiscal crisis.

Figure 3. Germany. Real* hourly wages in selected sectors and total labour productivity° (Indexes, 1991 = 100).

Given the federal structure, the state is represented in PSWS at three different levels. The federal Ministry of the Interior represents the federal government. The Länder are organized collectively in the Association of German States (TdL),Footnote9 grouping together the states’ finance ministers.Footnote10 Municipal governments organize collectively through the Association of Municipal Employers (VKA).Footnote11 Until the mid-2000s, Germany’s PSWS system was centralized and co-ordinated across the two different employment categories: public employees (Tarifbeschäftigte) subjected to collective bargaining and civil servants (Beamte) whose wages were set via federal legislation (Keller, Citation1999). State employers from the three levels bargained jointly at the national level under the aegis of the Ministry of the Interior. Once collective contracts were signed with the unions, similar provisions were usually extended to the civil servants with a federal law.

In this centralized system, wage restraint was ensured by finance ministers in multiple ways. At the federal level, the Minister of the Interior acts in liaison with state secretaries in the finance ministry who must approve formally the provisions of collective agreements to ensure budgetary restraint (Interview 1). At the states’ level, PSWS is the direct responsibility of regional finance ministers who first coordinate horizontally within the TdL to reach a unitary position in PSWS, and then coordinate vertically with the federal finance ministry ahead of negotiations with the unions. During the 1990s, the Finance Minister Theo Waigel orchestrated restrictive PSWS and civil servant wage freezes (in 1994) to bring the budget deficit below the 3 per cent limit imposed by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). Waigel had a savings package approved in 1996 which severely curtailed funds for PSWS, against which unions eventually caved in to safeguard other accessory benefits (Di Carlo, Citation2019).

Once in EMU, Germany’s fiscal crisis deteriorated (Streeck, Citation2007), not least because of missing revenues due to Gerard Schroeder’s tax reforms. In dire straits, the states’ finance ministers pulled out of the public employers’ bargaining coalition to impose meagre wage increases. Negotiations then began with the unions on how to reform the whole collective bargaining framework.

In 2005, the federal and municipal employers launched a new joint bargaining framework, i.e., the TVöD contractFootnote12 (Interviews 11, 12). The states, instead, created their own bargaining framework in 2006 – i.e., the TV-L contractFootnote13 – not least to gain independence from the municipal level where unions’ strike capacity remained high. Concomitantly, with the 2006 constitutional reform – under the leadership of rich Länder spearheaded by Bavaria – the states obtained the competence to legislate on the wages of their respective civil servants (Interviews 9, 13, 14).

Ever since, the new system combines elements of organized-decentralization in collective bargaining (now on two levels) and competitive federalism where states now set their civil servants’ wages independently. Yet, wage restraint remains in-built in PSWS due to the delegation of PSWS authority to finance ministers.

In states’ level collective bargaining, the regional finance ministers represented in TdL conduct PSWS with the unions. This implies consensus-based agreements are only possible if they reflect the interests of all participant finance ministers. For this to happen, the TdL must represent the general interest of all states in PSWS, leaving no room to accommodate the special-interest politics of states’ local politicians (Interview 8). Moreover, the need to reach negotiated agreements within TdL leads to moderate PSWS due to marked differences in fiscal capacity between rich and poorer German states. In fact, states have very large wage bills due to the decentralization of administrative competencies within Germany’s federal polity (Benz, Citation1999). However, states cannot adjust their revenues discretionally because tax policy is a federal competence and requires high-consensus constitutional changes to be altered. At the same time, subnational governments remain chronically underfunded despite the system of fiscal equalization (Heinz, Citation2016). Thus, given the mismatch between high administrative expenditures and constrained fiscal capacity, states’ finance ministers (and municipalities) are pressured to impose restrictive PSWS (Benz & Sonnicksen, Citation2017). While expansionary PSWS is generally not a problem for rich states (e.g., Bavaria) – with vibrant local economies and higher fiscal capacity –, for poorer states (e.g., Saarland) it becomes instead a matter of financial survival. Negotiated compromises on wage policies require PSWS to be set as a ‘lowest common denominator’, i.e., around meagre wage increases poor states (and municipalities) can afford to pay (Di Carlo, Citation2019). Otherwise, as occurred in the early 2000s, poorer states would start quitting the employers’ association, leading to the collapse of state-level coordinated bargaining. For analogous reasons, moderate wage policies must be reached in the TVöD contract where the federal and municipal levels bargain collectively. Here, negotiated wage policies are only possible to the extent to which they incorporate the financial concerns of the many cash-stripped municipal treasurers across Germany (Interview 10).

In all, despite Germany’s highly decentralized polity, PSWS remains restrictive due to direct and indirect delegation of PSWS authority to finance ministers at various state levels. Wage moderation is further hardwired into the German system because the need for negotiated compromises within national coordination institutions forces the public employers to conduct fiscally responsible PSWS, leaving no room to accommodate special-interest politics.

Portugal: from authoritarianism to state-led rigour ‘in the shadow of Europe’

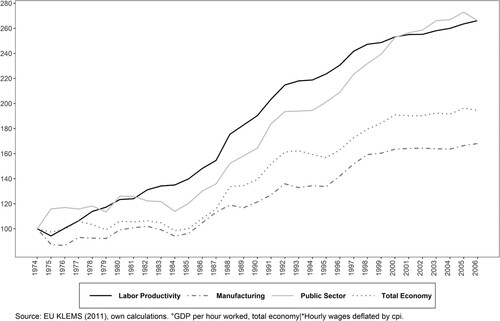

Portugal features a centralized system of PSWS governance where wage-setting is the direct responsibility of the minister of finance who negotiates nationally within three separate tables based on trade-union affiliation (Document 15). Other ministers negotiate on various aspects specific of their ministries’ employment terms. But wage determination is centralized under the sole responsibility of the finance minister who sets PSWS for the whole public sector to ensure coherent incomes policies and sound public finances (OECD, Citation1997, p. 45). Since Portugal’s democratization in 1974, this system of direct delegation has produced moderate real wage increases below or in line with labour productivity (). Like France, the finance ministry plays a pivotal role in centralized PSWS. This reflects both Portugal’s authoritarian past and the need to compensate for social partners’ weakness in a fragmented system of interest representation.

Figure 4. Portugal. Real* hourly wages in selected sectors and total labour productivity° (Indexes, 1974 = 100).

Until 1974, Portugal was under the conservative authoritarian regime established with Salazar’s Estado Novo. Within the corporatist system, the social partners were subdued to the regime and wage-setting was subordinated to the state’s priorities. With the new democratic constitution in 1976, independent trade unionism was established but, initially, the state continued to set incomes policy unilaterally (Document 16) by decreeing wage ceilings (tectos salariais) and wage rates across the economy (Barreto & Naumann, Citation1998). In the 1980s, the Grand Coalition government supported by the socialists (PS) and the conservatives (PSD) established the Standing Committee for Social Concertation (SCSC) as a forum to promote concertation with the social partners aimed at deflating the economy ahead of Portugal’s entry into the European Economic Community (Campos Lima & Naumann, Citation2011). After a series of successful social pacts (Dornelas, Citation2010) concertation begun to fail repeatedly, inducing the government to take a more activist stance in national wage policy (Document 16).

In this context, the ministry of finance initiated the practice of governing the process of wage formation across the economy via PSWS. Although collective bargaining was introduced in 1998, it is not binding for the government and, similar to France, PSWS occurs in the shadow of hierarchy because the finance minister defines PSWS unilaterally when unions fail to accept its conditions (Document 15). Generally, the finance ministry would propose a wage rate at the end of the year to then enter negotiations with the unions based on the government’s pre-determined budget constraints (Document 15). If, by February, no agreement could be reached, wage increases would be set unilaterally by the finance ministry and establish the wage norm for the whole economy. This practice of public sector-led pattern bargaining became institutionalized during the 1990s (Document 17).

However, restrictive PSWS became pronounced in the mid-2000s due to mounting budget deficits and the threat of sanctions from the European Council under the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) of the SGP. Despite the European Council failing repeatedly to enforce the SGP in the early 2000s, Portuguese governments still considered the SGP as a hard external constraint (Stoleroff, Citation2007) for fear of losing access to Europe’s structural funds (Magone, Citation2017, p. 34). Thus, during the years before the financial crisis, restrictive wage policy in the public sector was repeatedly imposed unilaterally under both the centre-right coalition government and the following Socialist majority government.

In 20002, José Manuel Barroso was elected on a liberal platform centred on fiscal/administrative reforms and tax cuts (Campos Lima & Naumann, Citation2011). Manuela Ferreira Leite – known as the iron lady for her hard-headed approach to public finances – was chosen to bring the budget deficit below the 3 per cent ceiling (Document 18). With the finance ministry committed to austerity, wage negotiations soon failed and unions organised strikes to paralyse essential services (Document 19). Yet, the finance ministry ignored unions' demands and advanced a non-negotiable 3.6 per cent pay rise and a cost-effective rationalization of the civil service. Lack of agreement with the unions eventually led the finance ministry to impose a below-inflation 2.75 per cent wage increase in 2003 (Document 20). In 2004, a meagre 2 per cent was granted only to workers in the lower pay grades and a unilateral freeze was imposed for the remaining categories (Document 21). Restrictive PSWS remained the game in town with the new socialist government led by Sócrates from 2005. Due to budgetary concerns, Finance Minister Fernando Teixeira dos Santos imposed a 1.5 per cent increase in both 2005 and 2006 justified as a ‘national imperative’ (Stoleroff, Citation2007, p. 645), against unions’ demands for 3.5–5.5 per cent. When the sovereign debt crisis hit, pursuant to the Memorandum of Understanding signed with the Troika, the Portuguese government went on unilaterally imposing a combination of further wage freezes and cuts (Rato, Citation2013).

Overall, Portuguese finance ministers directly in charge of PSWS have traditionally adopted restrictive PSWS as an instrument of economic governance to shore up public finances and ensure Portugal’s continuing access to Europe’s structural funds.

Conclusions

This article argues that, contrary to received wisdom from the neo-corporatist scholarship, PSWS is not primarily a problem of inter-sectoral wage co-ordination between sheltered and exposed industries. In fact, cross-country variation in PSWS cannot be explained fully by the presence/absence of neo-corporatist wage-setting regimes. Although insightful, due to its excessive focus on ‘rent-seeking’ trade unions, extant neo-corporatist literature fails to capture the fiscal nature of PSWS and the political incentives of public sector wage-setters. The state-centred theoretical framework proposed in this article aims at incorporating these specific traits of PSWS rather than treating it as an appendix of export-sector interests.

Without the need to embrace full-fledged public choice accounts of malevolent politicians, highlighting the common-pool problem of PSWS simply helps us to focus on dynamics of special-interest politics, which are central in processes of PSWS. I have argued that public sector wage restraint hinges on the delegation of PSWS authority to state actors charged with a mandate to ensure fiscal/wage moderation in PSWS. Delegation occurs by delegating key PSWS powers to the finance ministry or an independent state agency with a mandate and powers to ensure ‘de-politicised’ PSWS. Thus, variation in PSWS outcomes ultimately depends on differences in the institutional capacity of PSWS systems to minimise the common-pool problem in-built in PSWS.

These findings yield interesting insights for the burgeoning literature on growth models (Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2016; Hassel & Palier, Citation2021). Wage-setting regimes shape both the demand and supply side of an economy because they determine workers’ disposable incomes and the emergence of inflation externalities that may jeopardize export-oriented growth strategies. Therefore, the characteristics of PSWS systems affect the functioning of growth regimes as much as policy choices in PSWS shape governments’ growth strategies through the simultaneous determination of fiscal and wage policy. This article’s findings urge us to pay closer attention to PSWS and the independent role state actors and states’ institutional configurations play in the definition of growth strategies.

However, the article makes no plea for public sector wage restraint. In fact, trajectories of wage restraint and inflation are equally problematic, for opposite reasons. Systematic wage restraint erodes the consumption capacity of the large public sector bourgeoisie, weakening domestic demand and wage-led growth. Conversely, sustained wage inflation generates negative externalities which must eventually be redressed through drastic measures, as the Italian and Greek cases demonstrate. This article suggests the need for governments to act as ‘model employers’ and ensure real wage growth aligned to the economy’s labour productivity. As sovereign employers, states are in a unique position to stabilize wage-setting across the economy through PSWS and partially compensate for organized labour’s weakness in today’s industrial relations systems.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.3 MB)Acknowledgments

I am particularly indebted to Timur Ergen and Anton Hemerijck for their insightful feedback on early drafts of this article. I would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Donato Di Carlo

Donato Di Carlo is Senior Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG) in Cologne.

Notes

1 Neo-corporatist theory is multifaceted (Molina & Rhodes, Citation2002; Streeck & Kenworthy, Citation2005) and its empirical applications vary (Jahn, Citation2014; Kenworthy, Citation2003; Siaroff, Citation1999). In the CPE literature, it describes both a distinctive structure of interest representation (Schmitter, Citation1974) and an inclusive mode of economic governance, i.e., concertation (Baccaro, Citation2003; Grant, Citation1985; Schmitter, Citation1982). While acknowledging this distinction, I engage only with the structuralist variant for scholars have explained cross-country variation in PSWS mostly through differences in wage-bargaining institutions.

2 Calmfors and Driffill (Citation1988) demonstrated that fully decentralized wage-setting systems would be functionally equivalent to centralized ones.

3 Mancur Olson famously termed these narrow interest groups ‘distributional coalitions’ (Citation1986).

4 Public employees generally enjoy the right to strike but limitations often exist for civil servants engaged in the provision of essential public services (Bordogna, Citation2007).

5 On the distinction between responsible and responsive governments see Mair (Citation2009).

6 Agenzia per la rappresentanza negoziale delle pubbliche amministrazioni.

7 Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro.

8 Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Lavoratori.

9 Tarifgemeinschaft deutscher Länder.

10 Hesse pulled out of TdL in 2004 and is no longer represented there.

11 Vereinigung der kommunalen Arbeitgeberverbände.

12 Tarifvertrag für den Öffentlichen Dienst.

13 Tarifvertrag für den öffentlichen Dienst der Länder.

References

- Alesina, A., Danninger, S., & Rostagno, M. (2001). Redistribution through public employment: The case of Italy. IMF Economic Review, 48(3), 447–473. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451858853.001

- Amable, B., Guillaud, E., & Palombarini, S. (2012). Changing French capitalism: Political and systemic crises in France. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(8), 1168–1187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.709011

- ARAN. (2007). Rapporto trimestrale sulle retribuzioni dei pubblici dipendenti, 1/2006. Agenzia per la Rappresentanza Negoziale delle Pubbliche Amministrazioni. https://www.aranagenzia.it/attachments/article/2972/A9n34.pdf

- Baccaro, L. (2003). What is alive and what is dead in the theory of corporatism. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 41(4), 683–706. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-8543.2003.00294.x

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, H. J. (2016). Rethinking comparative political economy: The growth model perspective. Politics & Society, 44(2), 175–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329216638053

- Bach, S., & Bordogna, L. (2011). Varieties of new public management or alternative models? The reform of public service employment relations in industrialized democracies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(11), 2281–2294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.584391

- Bach, S., & Bordogna, L. (2018). Public service management and employment relations in Europe: Emerging from the crisis. Routledge.

- Bach, S., Bordogna, L., Della Rocca, G., & Winchester, D. (1999). Public service employment relations in Europe: Transformation, modernization or inertia? Routledge.

- Baglioni, G. (2011). La lunga marcia della CISL: 1950-2010. Il Mulino.

- Barreto, J., & Naumann, R. (1998). Portugal: Industrial relations under democracy. In A. Ferner & R. Hyman (Eds.), Changing industrial relations in Europe (pp. 395–425). Blackwell.

- Beaumont, P. B. (1992). Public sector industrial relations. Routledge.

- Benz, A. (1999). From unitary to asymmetric federalism in Germany: Taking stock after 50 years. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 29(4), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a030052

- Benz, A., & Sonnicksen, J. (2017). Advancing backwards: Why institutional reform of German federalism reinforced joint decision-making. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 48(1), 134–159. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjx055

- Beramendi, P., Häusermann, S., Kitschelt, H., & Kriesi, H. (2015). The politics of advanced capitalism. Cambridge University Press.

- Bordogna, L. (2002). Contrattazione integrativa e gestione del personale nelle pubbliche amministrazioni: un'indagine sull'esperienza del quadriennio 1998-2001. Franco Angeli.

- Bordogna, L. (2007). Industrial relations in the public sector. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working conditions. Eurofound. www.eurofound.europa. eu/eiro/studies/tn0611028s/tn0611028s.html

- Bordogna, L., Dell’Aringa, C., & Della Rocca, G. (1999). The reform of public service employment in Italy: A case of coordinated decentralization. Routledge.

- Bordogna, L., & Pedersini, R. (2013). Economic crisis and the politics of public service employment relations in Italy and France. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 19(4), 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680113505035

- Calmfors, L. (1993). Centralisation of wage bargaining and macroeconomic performance. A survey. OECD Economic Studies. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). https://www.oecd.org/social/labour/33945244.pdf

- Calmfors, L., & Driffill, J. (1988). Bargaining structure, corporatism and macroeconomic performance. Economic Policy, 3(6), 13–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/1344503

- Campos Lima, d. P. M., & Naumann, R. (2011). Portugal: From broad strategic pacts to policy-specific agreements. In S. Advagic, M. Rhodes, & J. Visser (Eds.), Social pacts in Europe (pp. 147–173). Oxford University Press.

- Crouch, C. (1990). Trade unions in the exposed sector: Their influence on neo-corporatist behaviour. In R. Brunetta & C. Dell’Aringa (Eds.), Labour relations and economic performance: Proceedings of a conference held by the International Economic Association in Venice, Italy (pp. 68–91). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Debrun, X. (2011). Democratic accountability, deficit bias, and independent fiscal agencies. IMF Working Papers, 11(173), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781462313327.001

- Dell’Aringa, C. (1997). La contrattazione e le retribuzioni pubbliche nel periodo 1994-1997: una breve (e parziale) cronistoria. In F. Carinci & M. D'Antona (Eds.), Il lavoro alle dipendenze delle amministrazioni pubbliche (pp. 6–23). Giuffrè.

- Di Carlo, D. (2018). The political economy of public sector wage-setting in Germany and Italy. In J. Hien & C. Joerges (Eds.), Responses of European economic cultures to Europe's crisis politics: The example of German-Italian discrepancies (pp. 48–62). European University Institute.

- Di Carlo, D. (2019). Together we rule, divided we stand: Public employers as semisovereign state actors and the political economy of public sector wage restraint in Germany [Doctoral dissertation]. Universität zu Köln. Köln.

- Di Carlo, D. (2020). Understanding wage restraint in the German public sector: Does the pattern bargaining hypothesis really hold water? Industrial Relations Journal, 51(3), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/irj.12288

- Dornelas, A. (2010). Social pacts in Portugal: Still uneven. In P. Pochet, M. Keune, & D. Natali (Eds.), After the Euro and enlargement: Social pacts in the EU (pp. 109–136). European Trade Union Institute.

- Eck, F. (1986). La direction du trésor. Presses Universitaires De France.

- Ferrera, M., & Gualmini, E. (2004). Rescued by Europe? Amsterdam University Press.

- Garrett, G., & Way, C. (1999). Public sector unions, corporatism, and macroeconomic performance. Comparative Political Studies, 32(4), 411–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414099032004001

- Gerring, J. (2006). Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge university press.

- Grant, W. (1985). Political economy of corporatism. Macmillan.

- Hall, P. (1986). Governing the economy: The politics of state intervention in Britain and France. Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P. (1994). The state and the market. In P. Hall, J. Hayward, & H. Machin (Eds.), Developments in French politics (pp. 171–187). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hall, P., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of capitalism : The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Hallerberg, M., Strauch, R., & Von Hagen, J. (2007). The design of fiscal rules and forms of governance in European Union countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 338–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2006.11.005

- Hancké, B. (2013). Unions, central banks, and EMU: Labour market institutions and monetary integration in Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Hassel, A., & Palier, B. (2021). Growth and welfare in advanced capitalist economies: How have growth regimes evolved? Oxford University Press.

- Heinz, D. (2016). Politikverflechtung in der Haushaltspolitik. In A. Benz, J. Detemple, & D. Heinz (Eds.), Varianten und Dynamiken der Politikverflechtung im deutschen Bundesstaat (pp. 246–289). Nomos.

- Hicken, A. (2011). Clientelism. Annual Review of Political Science, 14(1), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220508

- Holm-Hadulla, F., Kamath, K., Lamo, A., Pérez, J. J., & Schuknecht, L. (2010). Public wages in the euro area: Towards securing stability and competitiveness. ECB Occasional Paper, 112.

- Hood, C. (1995). The “new public management” in the 1980s: Variations on a theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(2-3), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0001-W

- Howarth, D. (2001). The French state in the Euro zone: ‘Modernization'and legitimizing dirigisme. In K. Dyson (Ed.), European states and the Euro: Europeanization, variation, and convergence (pp. 145–172). Oxford University Press.

- Howell, C. (2011). Regulating labor: The state and industrial relations reform in postwar France. Princeton University Press.

- Hyman, R. (2013). The role of government in industrial relations. In J. Heyes & L. Rychly (Eds.), Labour administration in uncertain times (pp. 95–124). Edward Elgar.

- Jahn, D. (2016). Changing of the guard: Trends in corporatist arrangements in 42 highly industrialized societies from 1960 to 2010. Socio-Economic Review, 14(1), 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwu028

- Jochimsen, B., & Thomasius, S. (2014). The perfect finance minister: Whom to appoint as finance minister to balance the budget. European Journal of Political Economy, 34, 390–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2013.11.002

- Johnston, A. (2011). The revenge of Baumol’s cost disease?: Monetary Union and the rise of public sector wage inflation. LEQS Paper. London School of Economics.

- Johnston, A. (2012). European Economic and Monetary Union’s perverse effects on sectoral wage inflation: Negative feedback effects from institutional change? European Union Politics, 13(3), 345–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512439114

- Johnston, A. (2016). From convergence to crisis: Labor markets and the instability of the Euro. Cornell University Press.

- Johnston, A., & Hancké, B. (2009). Wage inflation and labour unions in EMU. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(4), 601–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760902872742

- Johnston, A., Hancké, B., & Pant, S. (2014). Comparative institutional advantage in the European sovereign debt crisis. Comparative Political Studies, 47(13), 1771–1800. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013516917

- Keller, B. (1999). Negotiated change, modernization and the challenge of unification. In S. Bach, L. Bordogna, G. D. Rocca, & D. Winchester (Eds.), Public service employment relations in Europe: Transformation, modernization or inertia? (pp. 56–93). Routledge.

- Kenworthy, L. (2003). Quantitative indicators of corporatism. International Journal of Sociology, 33(3), 10–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/15579336.2003.11770269

- Kitschelt, H., & Wilkinson, S. I. (2007). Patrons, clients and policies: Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition. Cambridge University Press.

- LaPalombara, J. (1966). Italy: The politics of planning. Syracuse University Press.

- Levy, J. (2005). Economic policy and policy-making. In A. Cole, P. L. Gales, & J. Levy (Eds.), Developments in French politics 3 (pp. 170–195). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. Yale University Press.

- Lordon, F. (1998). The logic and limits of desinflation competitive. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 14(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/14.1.96

- Lucifora, C., & Meurs, D. (2006). The public sector pay gap in France, Great Britain and Italy. Review of Income and Wealth, 52(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2006.00175.x

- Magone, J. (2017). The developing place of Portugal in the European Union. Routledge.

- Mair, P. (2009). Representative versus responsible government. (MPIfG working paper series 2009/08). Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Majone, G. (1994). The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics, 17(3), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389408425031

- Marglin, S. A., & Schor, J. B. (1992). The golden age of capitalism: Reinterpreting the postwar experience. Oxford University Press.

- McNamara, K. (2002). Rational fictions: Central bank independence and the social logic of delegation. West European Politics, 25(1), 47–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/713601585

- Moessinger, M. D. (2012). Do personal characteristics of finance ministers affect the development of public debt? ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper, 12(68).

- Molina, O., & Rhodes, M. (2002). Corporatism: The past, present, and future of a concept. Annual Review of Political Science, 5(1), 305–331. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.5.112701.184858

- Molina, O., & Rhodes, M. (2007). The political economy of adjustment in mixed market economies: A study of Spain and Italy. In B. Hancké, M. Rhodes, & M. Thatcher (Eds.), Beyond varieties of capitalism: Conflict, contradictions, and complementarities in the European economy (pp. 223–252). Oxford University Press.

- Mossé, P., & Tchobanian, R. (1999). France: The restructuring of employment relations in the public services. In S. Bach, L. Bordogna, G. D. Rocca, & D. Winchester (Eds.), Public service employment relations in Europe: Transformation, modernization or inertia? (pp. 130–163). Routledge.

- Müller, T., & Schulten, T. (2015). The public-private sector pay debate in Europe. (ETUI working paper 2015.08). European Trade Union Institute.

- Olson, M. (1986). A theory of the incentives facing political organizations: Neo-corporatism and the hegemonic state. International Political Science Review, 7(2), 165–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251218600700205

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (1997). Budgeting and monitoring of personnel costs.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2012). OECD budget practices and procedures survey.

- Oxley, H., & Martin, J. P. (1991). Controlling government spending and deficits: Trends in the 1980s and prospects for the 1990s. OECD Economic Studies, 17, 145–189.

- Ozaki, M. (1987). Labour relations in the public service. International Labour Review. International Labour Office.

- Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2016). Political economics. MIT press.

- Pierson, P. (1996). The new politics of the welfare state. World Politics, 48(2), 143–179. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.1996.0004

- Pizzorno, A. (1978). Political exchange and collective identity in industrial conflict. In C. Crouch & A. Pizzorno (Eds.), The resurgence of class conflict in Western Europe since 1968. Vol.2 Comparative analyses (pp. 277–298). Macmillan.

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform: A comparative analysis-new public management, governance, and the neo-weberian state. Oxford University Press.

- Postel-Vinay, F. (2015). Does it pay to be a public-sector employee? IZA World of Labor. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA).

- Poterba, J. M., & Von Hagen, J. (1999). Fiscal institutions and fiscal performance. University of Chicago Press.

- Ranci, P. (1987). Italy: The weak state. In F. Duchene & G. Shepherd (Eds.), Managing industrial change in Western Europe (pp. 111–144). Frances Pinter.

- Rato, H. (2013). Portugal: Structural reforms interrupted by austerity. In D. Vaughan-Whitehead (Ed.), Public sector shock. The impact of policy retrenchment in Europe (pp. 411–448). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Regalia, I., & Regini, M. (1998). Italy: The dual character of industrial relations. In A. Ferner & R. Hyman (Eds.), Changing relations in Europe (pp. 459–503). Blackwell.

- Regan, A. (2012). The political economy of social pacts in the EMU: Irish liberal market corporatism in crisis. New Political Economy, 17(4), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2011.613456

- Ricciardi, M. (2010). La parabola: ascesa e declino della contrattazione collettiva in Italia. CLUEB.

- Rose, R., Page, E., Parry, R., & Peters, B. G. (1985). Public employment in Western nations. Cambridge University Press.

- Santagata, W. (1995). Economia, elezioni, interessi: una analisi dei cicli economici elettorali in Italia. Il Mulino.

- Santoro, P. (2014). Deboli ma forti. Il pubblico impiego in Italia tra fedeltà politica e ammortizzatore sociale: Il pubblico impiego in Italia tra fedeltà politica e ammortizzatore sociale. Franco Angeli.

- Scharpf, F. W. (1991). Crisis and choice in European social democracy. Cornell University Press.

- Scharpf, F. W. (1997). Games real actors play: Actor-centered institutionalism in policy research. Westview Press.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2002). The futures of European capitalism. Oxford University Press.

- Schmitter, P. C. (1974). Still the century of corporatism? The Review of Politics, 36(01), 85–131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034670500022178

- Schmitter, P. C. (1982). Reflections on where the theory of neo-corporatism has gone and where the praxis of neo-corporatism may be going. In G. Lehmbruch & P. Schmitter (Eds.), Patterns of corporatist policy-making (pp. 259–279). SAGE.

- Shonfield, A. (1965). Modern capitalism. The changing balance of public and private power. Oxford University Press.

- Siaroff, A. (1999). Corporatism in 24 industrial democracies: Meaning and measurement. European Journal of Political Research, 36(2), 175–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00467

- Soskice, D. (1990). Wage determination: The changing role of institutions in advanced industrialized countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 6(4), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/6.4.36

- Stoleroff, A. (2007). The revolution in the public services sector in Portugal: With or without the unions. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 13(4), 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/102425890701300408

- Streeck, W. (2007). Endgame? The fiscal crisis of the German state (MPIfG Discussion Paper No. 07/7). Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Streeck, W., & Kenworthy, L. (2005). Theories and practices of neocorporatism. In T. Janoski, R. Alford, A. Hicks, & M. A. Schwartz (Eds.), The handbook of political sociology. States, civil societies, and globalization (pp. 441–460). Cambridge University Press.

- Talamo, V. (2009). Gli interventi sul costo del lavoro nelle dinamiche della contrattazione collettiva nazionale ed integrativa. Il Lavoro Nelle Pubbliche Amministrazioni, 3(4), 1–38.

- Thatcher, M., & Sweet, A. S. (2002). Theory and practice of delegation to non-majoritarian institutions. West European Politics, 25(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/713601583

- Trantidis, A. (2016). Clientelism and economic policy: Hybrid characteristics of collective action in Greece. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(10), 1460–1480. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1088564

- Traxler, F. (1999). The state in industrial relations: A cross-national analysis of developments and socioeconomic effects. European Journal of Political Research, 36(1), 55–85. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007023807441

- Traxler, F., & Brandl, B. (2010). Collective bargaining, macroeconomic performance, and the sectoral composition of trade unions. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 49(1), 91–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2009.00589.x

- Vaughan-Whitehead, D. (2013). Public sector shock: The impact of policy retrenchment in Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Von Hagen, J. (2008). Political economy of fiscal institutions. In D. A. Wittman & B. R. Weingast (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political economy (pp. 464–478). Oxford University Press.

- Von Hagen, J., & Harden, I. J. (1995). Budget processes and commitment to fiscal discipline. European Economic Review, 39(3-4), 771–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(94)00084-D

- Wyplosz, C. (2005). Fiscal policy: Institutions versus rules. National Institute Economic Review, 191, 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027950105052661

- Zysman, J. (1977). The French state in the international economy. International Organization, 31(4), 839–877. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300018695

- Zysman, J. (1984). Governments, markets, and growth: Financial systems and the politics of industrial change. Cornell University Press.