ABSTRACT

In this paper, we investigate how different types of right parties affect immigrant welfare rights across 14 countries (1980–2018) in a comprehensive mixed-method study. We argue that populist radical right parties (PRRPs) support retrenchment, liberals and conservatives oppose expansions, and Christian democrats rather protect or expand rights. Accordingly, we expect conservatives and liberals to be more receptive to both direct and indirect influence of PRRPs than Christian democrats. We apply balanced panel regressions, and also include interactions with immigration indicators. Changes in immigrant welfare rights are measured using a new and encompassing dataset (MigSP), that maps immigrant welfare rights in 14 countries over 38 years. Furthermore, we qualitatively assess model-based selected cabinets in Denmark. Our evidence confirms pronounced differences between different right-wing parties. PRRPs are systematic propellers of cutting rights and affect all mainstream right parties when governing together. Christian democrats are the least likely to conduct retrenchments. We find no quantitative evidence for the indirect effects of PRRPs (contagion) and immigration dynamics. The case study evidence, however, points to the importance of both factors and discusses why indirect partisan effects (contagion) and the politicisation of immigration are very difficult to address in the standard regression framework.

Introduction

Immigrants have been found to be more strongly exposed to the different life-course risks that modern welfare states intend to mitigate. Yet, immigrant welfare rights (IWRs) have rarely been completely at par with and typically below the rights of citizens. In the literature, changes in IWR have been predominantly rationalized from a structural perspective (Koning & Banting, Citation2013; Joppke, Citation2007; Soysal & Soyland, Citation1994) or by emphasizing the role of existing welfare (Banting, Citation2000; Boräng, Citation2015; Römer, Citation2017), immigration, and integration regimes (Sainsbury, Citation2012). We complement the state of the art with a party-focused perspective for two reasons. First, immigrant welfare rights vary empirically more widely across time and countries than a perspective on structural shifts or welfare and immigration regimes would lead us to expect. Second, we know relatively little from systematic comparative research about the role political parties play in changing the welfare rights of immigrants, although party arguments have dominated research on welfare state provision for citizens (e.g., Huber & Stephens, Citation2001; Korpi & Palme, Citation2003; Häusermann et al., Citation2020; Beramendi et al., Citation2020).

Some previous results have pointed to the importance of social democratic parties (Sainsbury, Citation2012; Schmitt & Teney, Citation2019) or have referred to the role of populist radical right parties (PRRPs; see Chueri, Citation2021), but the precise role of mainstream right parties and their interaction with PRRPs remains unclear. In this study, we thus investigate the role all types of right-wing parties play in the process of changing and reshaping IWR. We argue that we need to understand these parties’ policy positions towards immigrant welfare rights as derived from how they expect the retrenchment or expansion of these rights to affect both the welfare state and integration but also the link between immigration and labour markets. For two subtypes within the right-wing party family, we maintain that there is a consistent position. PRRPs will have a clear preference for retrenchment, whereas Christian democrats tend to be hesitant to cut IWR. For liberals and conservatives, on the other hand, cuts are in line with their general stances on immigration, integration, and the welfare state, but unlike for PRRPs, these cuts do not serve an important strategic position.

We employ a mixed-method design to rigorously scrutinize our expectations using a dataset that covers cabinets in 14 European countries from 1980 to 2018. To facilitate an adequate comparison, we distinguish between the effects of all types of right-wing parties (radical right, Christian democrat, conservative, and liberal) on immigrants’ welfare entitlements in comparison to ‘pure left-wing’ governments (governments without the participation of any of the right-wing parties listed above). We also include interactions with immigration indicators to test whether parties are differently affected by changing immigration dynamics. Furthermore, we use entropy balancing to adjust the most important confounders in panel regressions. Finally, based on the quantitative models we selected cabinet-cases from Denmark for a complementary qualitative comparison.

Our evidence supports the claim that PRRPs in government are the predominant drivers of IWR retrenchment. Regardless of who they govern with, PRRPs are significantly associated with cuts. Christian democrats appear to be the least likely mainstream right party to reduce immigrant rights, and are also the least responsive when governing with PRRPs, whereas conservatives are the sub-party type that reduces immigrants’ welfare rights the most when in government with PRRPs. The influence of electoral pressure from PRRPs and the role of immigration dynamics is not systematically visible in the large-n analyses. Our case study evidence however substantiates the hypotheses that PRRPs affect mainstream parties’ policy making even when they are not part of the government, and also points to the importance of immigration dynamics.

Right parties and immigrant welfare rights

In the 1970s and 1980s, many democracies experienced gradual equalization between immigrant and non-immigrant welfare entitlements and started to grant certain rights to immigrants, such as family benefits, or minimum income schemes (Sainsbury, Citation2012). This reflects a principle of welfare community inclusion in line with the post-war human rights discourse (Soysal & Soyland, Citation1994) and marked the transition from the citizenship model to the post-national welfare state model (Brubacker, Citation1989; Koning & Banting, Citation2013). Since the 1980s, the concept of ‘civic integration’ has however increasingly become a guiding principle in several countries. This shift entails the emphasis on duties rather than rights (Joppke, Citation2007, pp. 5–9). ‘Integration’ became a condition for residence rights. This meant for example that benefits turned into a prerequisite for the right to family reunification, or that residence rights and the renewal of permits depended on employment status (Boräng, Citation2015; Schmitt & Teney, Citation2019).

These broader developments, however, should not mask the fact that there is substantive variation within and between countries that cannot be explained by the aforementioned theoretical approaches. In this paper, we thus focus on the key actors that drove these policy changes, concentrating on the different subtypes of right-wing party families. To understand how parties will commit themselves to either extending or retrenching IWR, we argue that one has to analyse how they position themselves in regard to immigration, integration, labour market, and welfare policies. These policy fields follow very distinct logics (Duncan & Van Hecke, Citation2008; Givens & Luedtke, Citation2005; Lutz, Citation2019). Integration policy, and at least to some extent welfare policy, tends to reflect party competition on the left-right continuum, but the same cannot be said for the nexus between immigration and labour market policy. In fact, immigration as labour supply is a cross-cutting issue for the mainstream right (Lutz, Citation2019, p. 522).

Generally speaking, the mainstream right is more likely to be anti-immigrant than the (centre) left (Abou-Chadi et al., Citation2021; but see Schmidt & Teney, Citation2019). Compared to left-wing parties, mainstream right-wing parties are also rather opposed to government redistribution (Jensen, Citation2014). Furthermore, the mainstream right is particularly confronted with incentives to reduce spending on welfare, as welfare states have been under increased pressure since at least the 1980s and mainstream right-wing parties in government are at the forefront of implementing such cuts (Röth et al., Citation2018). A closer look reveals however that mainstream right-wing parties differ substantially in their positions on welfare, immigration, and integration (Gidron & Ziblatt, Citation2019; Hadj Abdou et al., Citation2022; Jensen, Citation2014; Van Kersbergen, Citation1995). Furthermore, whereas Christian democrats tend to have a rather consistent set of preferences across the three domains, liberal and conservative parties face trade-offs (Hadj Abdou et al., Citation2022; Lutz, Citation2019). In the following, we will discuss for each of the four subtypes,Footnote1 namely PRRPs, Christian democrats, liberals, and conservatives how their positions on these policy fields align into a position on IWR.

Different stances on immigrant welfare rights within the right

The party that has the most unified position on IWR are PRRPs. These parties embrace the negative effects that cuts in IWR have on immigration,Footnote2 in regard to integration they emphasize immigrants’ duties instead of their rights, and in regard to welfare policies they increasingly support (selective) generous welfare rights for citizens. This has however changed over time. Whereas the initial winning formula of PRRPs (Kitschelt & McGann, Citation1995) stressed general support for retrenchment across the board, now they emphasize differences in welfare deservingness between natives and immigrants. Welfare chauvinism by now has become an essential part of most populist radical right-wing parties’ agendas (Andersen & Bjørklund, Citation1990, p. 212; Minkenberg, Citation2001; Schumacher & Van Kersbergen, Citation2016). Welfare chauvinism allows PRRPs to pursue a nativist agenda in the domain of welfare that combines cutbacks in social spending for immigrants with generous provisions for selected ‘natives’. Once the protection of ‘natives’ as a ‘deserving group’ has been established, purportedly generous entitlements of immigrants can be problematized, and cutting the welfare rights of immigrants can be framed as relative improvement of the ‘deserving natives’ (Engler & Weisstanner, Citation2021; Gidron & Hall, Citation2017). Limiting IWR has thus become a core demand of PRRPs to reduce purported incentives for immigration, foster ‘assimilation’, and increasingly also promote the recognition of their core voter groups as the more deserving part of the population. We therefore expect PRRPs in office to have a negative impact on immigrant welfare rights (Hypothesis 1).

In contrast, Christian democrats are likely to protect or even expand IWR. This partly stems from their more positive stance towards the welfare state in general. Christian democrats in fact played an important role in welfare state expansion until the 1970s (Allan & Scruggs, Citation2004) and are generally more accepting of social spending (Jensen, Citation2014). Similarly, Schumacher et al. (Citation2013) classify Christian democrats as holding a ‘positive’ welfare image.Footnote3 Also, in the domains of immigration and integration, Christian democrats tend to have more positive positions. Cutting the rights of immigrants – especially regarding family reunification and/or asylum – is likely to be perceived by the church and part of the electorate as compromising on ‘Christian values’ (Van Kersbergen, Citation1995; see also Arzheimer & Carter, Citation2009; Bale, Citation2008). Case study evidence from Germany, Italy and Austria equally demonstrates that catholic organizations and Christian democrats were the strongest opponents of reduced immigrant rights (Arzheimer & Carter, Citation2009; Zaslove, Citation2004). It is important to note that we do not conceptualize Christian democracy as a solid bulwark against anti-immigrant policy making. There have been instances where Christian democrats have indeed collaborated with PRRPs, and also have exhibited anti-immigrant positions and policy making (compare Bale & Krouwel, Citation2013, pp. 35–36). However, we argue that in comparison with other mainstream right parties, Christian democratic parties will be less inclined to cut immigrant welfare rights, both because they tend to have more pro-immigrant as well as pro-welfare attitudes. Overall, we thus expect Christian democrats in government to expand or at least maintain the level of immigrant welfare rights (Hypothesis 2).

Conservatives and liberals finally both tend to support welfare retrenchment and support a workfare approach on integration, which combined would amount to a negative stance towards IWR. However, both parties might face cross-cutting pressures in regard to immigration policies. Liberals tend to be more open towards immigration (Duncan & Van Hecke, Citation2008; see also Bale, Citation2008), whereas conservatives have been found to be more authoritarian and nationalist, pushing for restrictive immigration policies (Akkerman, Citation2012). Bale (Citation2008) and Lutz (Citation2019) however emphasize that conservatives are close to business interests (see also Bale, Citation2003; Green-Pedersen & Odmalm, Citation2008)Footnote4 and comparative case studies indicate that both liberals and conservatives assess immigration policies predominantly from a perspective of labour market supply (Green-Pedersen & Odmalm, Citation2008; Zaslove, Citation2004; Zaslove, Citation2006). Keeping in mind that generous rights are often perceived as a pull factor for migration, both parties might thus also hesitate to conduct cuts. Overall though, liberals and conservatives more likely will be opposed to than supportive of generous welfare rights. Furthermore, for these parties, as both oppose generous provisions for natives, retrenching immigrant welfare rights does not take a pivotal strategical position as it does for PRRPs. We thus do not expect a systematic effect of government participation by conservatives or liberals on immigrant welfare rights (Hypothesis 3). We however do expect that when governing with PRRPs, conservatives and liberals will support PRRP demands to cut IWR to a larger extent than Christian democrats (Hypothesis 4).

The influence of PRRP electoral pressure and rising immigration

As we have outlined above, we expect PRRPs in government to be the main driver of cuts in immigrant welfare rights. Previous literature has shown that to affect mainstream parties’ positions and policymaking, PRRPs do not necessarily have to be in government though (Abou-Chadi, Citation2016; Lutz, Citation2019; Schain, Citation2008; Van Spanje, Citation2010). PRRPs’ electoral weight affects mainstream parties via ‘contagion’ (see Van Spanje, Citation2010) when mainstream parties adopt their position in response to PRRP electoral threat. PRRPs may thus also indirectly influence policymaking, if mainstream parties act upon their shifted position and turn pledges into legislation. Yet, it remains unclear whether different subtypes within the mainstream right are affected equally by the PRRP challenger. There is evidence for a lower likelihood of religious people to support the radical right anti-immigrant platform (Arzheimer & Carter, Citation2009; Siegers & Jedinger, Citation2021; Marcinkiewicz & Dassonneville, Citation2021; Montgomery & Winter, Citation2015) which suggests that the electoral pressure of PRRPs should be stronger for conservative and liberal parties in comparison to Christian democrats. We thus hypothesize that Christian democrats are less likely to respond to electoral pressure from PRRPs with cuts in immigrant welfare rights than liberal and conservative parties (Hypothesis 5).

While electoral pressure from PRRPs constitutes an important context factor for mainstream right policy making, we also want to consider the role of immigration dynamics. We hypothesize that both immigrant flows and stocks may impact mainstream right policy making, although the mechanisms slightly differ between the two measures. Rising rates of immigrant inflows may raise the salience of the topic, and thus pressure political parties to respond to the issue. In line with the reasons described in the previous section, we expect that in times of high salience, Christian democrats are even more likely to be bound by pro-immigrant and pro-welfare norms than the other mainstream parties. Furthermore, in the face of rising numbers of immigrants the relative importance of maintaining a steady labour supply, which is the only factor that makes liberals, and to a lesser extent, conservatives, take pro-immigration positions, becomes less pressing. We thus expect them to respond to rising flow with cuts. To some extent, similar dynamics might be triggered by increases in immigrant stocks. As changes in stocks tend to fluctuate to a lesser extent though, we hypothesize that it is less an increase in salience than a potential change in deservingness perceptions that will lead parties to respond. Again, we would expect that compared to conservatives and liberals, Christian democrats will be less inclined to view immigrants as undeserving. With a growing immigrant population, cutting rights however also furthers cost containment, which is important for all mainstream right parties. Accordingly, we hypothesize that liberals and conservatives should reduce IWR in light of rising immigration flows and stocks whereas Christian democrats should remain resilient. The difference between the three parties should however be more pronounced for the influence of flows than stocks (Hypothesis 6).

Data and methods

Based on data for 14 countriesFootnote5 from 1980 until 2018, the identification of the effects right parties have on IWR follows a straightforward solution to tackle the three key dimensions of causal identification (compare Pearl, Citation2009). (1) We address the problem of asymmetry (ensuring the precedence of the cause to the effect) by using changes of IWR as the dependent variable.Footnote6 (2) We apply entropy balanced panel regressions to reduce the problem of confounding. (3) Based on the model results, we select all cabinets in Denmark as a combination of pathway and control cases to investigate with more causal depth how the different compositions of governments have affected the welfare rights of immigrants. Thus, short of any means to randomize the composition of governments, we follow a second-best strategy to assess the link between the partisan composition of governments and changing immigrant welfare rights.

Dependent variable

To measure the extent to which immigrants are excluded from welfare benefits, we use items from the Migration Social Protection (MigSP) database, which builds on the Immigration Policies in Comparison database (IMPIC). These newly collected original data make it possible to systematically assess how rights to social assistance differ from citizens’ rights over time and across a larger number of different countries (Bjerre et al., Citation2015; Helbling et al., Citation2017; Römer et al., Citation2021, for a description of the data collection process see Online Appendix I). They depict the welfare rights of non-EU immigrants and allow differentiating between the rights of temporary and permanent labour migrants, asylum seekers, refugees, and also account for rights to family reunification. Our conceptualization of IWR looks at four dimensions, namely access to benefits, types of benefits, consequences of benefit receipt, and preventive measures. The latter two dimensions capture the effects of job loss and benefit receipt for residency status and the right to family reunification. Such consequences can be thought of as indirect restrictions that are unique to immigrants (in the sense that citizens will not be required to leave the country if lose their job) and have often been overlooked by previous studies on IWR. In total there are thus nine items that measure both direct and indirect restrictions of IWR (see Table AI in the Online Appendix).

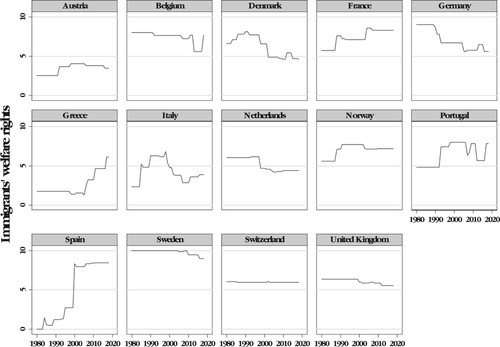

In the main analyses, we rely on Overall Welfare Rights of Immigrants which is the average of the four dimensions, and is standardized from 0 to 10, with higher scores denoting more rights for immigrants. Taking an unweighted average assumes that all dimensions are of equal weight, but is an easily replicable and accessible methods of index construction (see also Bjerre et al., Citation2019). depicts how Overall Welfare Rights of Immigrants varies between countries and over time. In the robustness section, we however also use the two sub-indices ‘direct restrictions’ and ‘indirect restrictions’, as well as indicators based on item response models (see Appendix VII). Throughout our analysis, we use the change in IWR as the dependent variable because we want to avoid endogeneity problems associated with the usage of levels (see Appendix VIII).

Main independent variables: right-wing parties in government

We define governments with right-wing participation as being governments where either conservative, Christian democrat, liberal or populist radical right parties participate either alone or in combination with each other. As a benchmark for comparison, we define ‘pure’ left-wing governments as governments without any right-wing party. Government participation of the defined party families is taken from the CPDS and ParlGov datasets (Armingeon et al. Citation2020; Döring & Manow, Citation2020). Our classification of PRRPs is based on Röth et al. (Citation2018) following the definition provided by Mudde (Citation2007) with nativism being their core ideological feature. We include formal cabinet members as well as informal coalition partners (see Bale & Bergman, Citation2006). A list of cabinets and their party composition is presented in the Online Appendix (Table AIIa). To measure electoral pressure and immigration dynamics we use (1) the strength of populist radical right parties in parliament (measured by the PRRPs’ share of parliamentary votes; compare the list of selected parties in the OA, Table AIIb) as well as (2) the number of immigrants (as a percentage of the overall population) and (3) the immigration rateFootnote7 as moderators in separate balanced panel regression models. Here, we are interested in the conditional effect of different mainstream parties and accordingly exclude all cases with PRRPs in cabinets from the models.

Before we turn to the descriptive association of cabinet compositions and changing IWR, we would like to point to some manual adjustments of the data. We became aware of two types of problems. First, reforms on IWR are coded yearly but in some years more than one cabinet exists. In such cases, we qualitatively sorted changes of IWR to the cabinet that implemented the reform. A second issue concerns the Organic Law 4/2000 in Spain. This law package reflects the biggest positive change of IWR in our sample. However, case knowledge indicates that it was rushed through in the last days of the Aznar I government with the approval of all left and regionalist opposition parties but expressively rejected by the conservative minority government (Delgado, Citation2000, p. 52). In this case, both types of measurement problems, temporal assignment and the link between cabinet composition and reform are present. We coded the cabinet for that specific year as ‘pure’ left to attribute the right partisan composition to the reform. Similarly, the 1983 Aliens Act in Denmark was pushed through by the left-wing opposition parties.

Balance and selection of potential confounders

In the Online Appendix III, we discuss theoretical and empirical reasons to control for potential confounders and list the potential confounders and their means in the control group (‘pure’ left-wing governments) and the ‘treatment’ group (right-wing parties in government). Governments with right-wing party inclusion have on average higher shares of immigrants in the population, lower GDP growth, and substantially more open economies than the control group. We balance all controls with systematic differences across treatment and control groups to achieve higher similarity in the comparison. The higher similarity is achieved by obtaining weights from the entropy balancing (Hainmueller & Xu, Citation2013) which we use as analytical weights in the panel regressions.

Results

provides a descriptive representation of cabinet participation and (adjusted) changes in immigrant welfare rights. All types of right parties have engaged in expanding as well as reducing immigrant welfare rights. Acknowledging the different number of years that the party families were in government, we calculate a descriptive yearly change in immigrant rights across party family and government participation. We find that on average, governments of mainstream right parties without PRRP participation have all conducted cuts,Footnote8 with liberals and conservatives being relatively similar, and Christian democrats being associated with the smallest reduction in IWR. PRRP participation in government corresponds to the strongest yearly reduction of immigrant rights. A closer look at the different coalitions including PRRPs reveals that PRRPs tend to reduce immigrant rights most strongly when governing with conservatives, and the least when having Christian democrats as coalition partners. These findings lend support to our Hypotheses 1–4. However, we should be careful not to over-interpret this descriptive statistic. A systematic comparison not only needs to address the differentiation of party families but to reduce potential confounding as described in the previous section.

Table 1. Change in the index of immigrant welfare rights and government participation of party families.

shows the results for our multivariate models. In the first model, we compare the effect right-wing governments have on immigrant welfare rights compared to ‘pure’ left-wing governments. We find that right parties systematically decrease immigrant welfare rights. In model 2, we show that once we split the right cabinets into governments with and without PRRPs, the negative effect of the right on IWR is considerably stronger for cabinets including PRRPs. Further differentiation of mainstream right parties indicates that none of the mainstream right party families alone systematically affect IWR in comparison to ‘pure left’ governments (model 3). This observation holds even when we balance all potential confounders and include model country-fixed effects (model 4). In line with our hypotheses, in model 4 the coefficient for the Christian democrats is positive, albeit not significant. The results of models 1–4 indicate that mainstream rights parties contribute to the systematic reduction of IWR predominantly in coalitions with the radical right (compare also ). These findings are robust to a series of alternative specifications and model choices (compare Online Appendix Parts V–VII). These robustness checks also entailed excluding countries from the analysis (see Table AVIb).Footnote9 The only exception were models in which Portugal is excluded. In these models, Christian democrats tend to have a significant positive association with changing IWR, which is in line with our hypotheses.

Table 2. Regression models for right-wing parties in government and changes in immigrants’ welfare rights.

We observe very similar estimates for the PRRPs across all model choices. Based on the average effect, the yearly difference between a cabinet including a PRRP in comparison to a government including solely left parties would amount to roughly −0.20 units of change in the index of IWR in a single year. Since the average cabinet duration is 2.55 years, the effect of PRRPs in comparison to left governments would amount to −0.51 during a cabinet term. Using a cabinet periodization instead of country-years leads to a very similar effect of PRRPs (0.55; compare Appendix V). The multivariate analyses thus support the hypothesis that PRRPs are the strongest drivers of reforms, and to some extent also underline differences between the mainstream parties.

The sensitivity section in the Online Appendix reveals a negative and significant effect for PRRPs even if we change the benchmark of comparison from ‘pure left’ to mainstream right (see OA Table AVIc). We also tested for differences between the dimensions of the index immigrant welfare rights. Overall, the results of the sensitivity section in the Online Appendix indicate that PRRPs are more effective in the reduction of direct access to welfare rights for immigrants and we find no significant effect on consequences, types of benefits or preventive measures although the coefficients are all negative. Disaggregating the index into sub-components also revealed that Christian democrats appear to defend cash benefits for asylum seekers whereas liberals seem eager to tighten consequences of welfare receipt for immigrants (compare Table AVIIc of the OA).

Turning to the conditional effects (models 5–7), we observe a tendency that the mainstream right responds with cuts in IWR to rising voter support for the radical right. However, none of those effects are significant. We also find no support for the immigration hypotheses. In fact, in contrast to our expectations only for Christian democrats the migration rate has a significant negative effect on changes in IWR. Noteworthy, and also running counter to our hypothesis is the positive and significant interaction of conservatives and the immigrant stock.

What might explain the lack of consistent finding for the interaction terms in the quantitative models?Footnote10 It is important to point out that although we observe changes in immigrant rights in 129 country-years out of a sample of 546 country-years, the isolation of conditional effects for individual mainstream parties suffers from few observations across the moderator. Furthermore, any effect of electoral pressure of PRRPs might not show up in the quantitative analyses for at least two reasons. First, electoral pressure of PRRPs might affect all parties, not just the mainstream right. This will not be captured by the interaction terms we are using in the analyses. Second, an effect of electoral pressure likely takes time to manifest. It is possible that electoral pressure first affects party positions, and only in subsequent years also has an effect on policy making. Similarly, there are reasons why the dynamics that are set off by rising immigration are not captured in the quantitative analyses. The politicization of immigration does not necessarily correspond to absolute numbers of immigrants. In contrast, specific events can trigger massive attention of the public although the numbers of immigrants involved might be negligible. We thus now turn to a qualitative assessment to substantiate both the significant and non-significant findings.

Case study Denmark

Our case selection aims at an assessment of the role different right parties play in changing IWR. Furthermore, we are interested how immigration and the rise of the radical right affects mainstream right parties. To select our cabinet-cases we build on the quantitative analysis, using the approach by Weller and Barnes (Citation2016) to identify so-called ‘pathway cases’. A pathway case can statistically be detected by comparing the residuals of a full model with the reduced model, i.e., a model where the key independent variable(s) are omitted (in our case, the cabinet composition variables). Thereby one can observe if the predictions are improved by incorporating the main explanatory variables. We calculate the sum of reduced residuals for all cases within one country over the entire period. The results indicate that Denmark is a country which fits the requirements of pathway cases very well (see Online Appendix IX for more details on the case selection).

It is however important to note that the generalization of the relationship between Christian democrats and IWR from the Danish case might be limited. The Kristendemokraterne never received more than 5.3 percent of the vote and thus cannot be considered a decisive player in the policy making process. Furthermore, there is some debate whether the party should be classified as Christian democracy. The Scandinavian Christian democratic parties are historically seen to be both more religious and more leftist than their counterparts elsewhere in Europe (Kalyvas & Van Kersbergen, Citation2010, p. 188). Madeley however shows that the successful Nordic Christian democrats have toned down their religious message and are thus approaching the mainstream Christian democratic model (Citation2004). Nevertheless, Danish cabinets are ideal to compare a large number of different types of right-wing coalitions over time. depicts the cabinet composition for all governments that ruled between 1980 and 2018. Those governments that were informally supported by the PRRP are set in italics (see also Appendix AIIa for more details).

Table 3. Cabinet Composition for seventeen governments in Denmark 1980–2018.

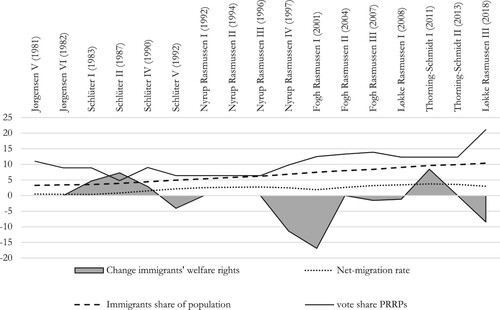

depicts an overview of the changes in immigrant welfare rights in Denmark from 1980 to 2018 and also traces the development of the PRRP vote share as well as immigrant flows and stocks over time. At the beginning of the time period, we consider in this paper (1980s), Denmark can be characterized as one of the most liberal systems in terms of immigrants’ welfare rights in Europe. At the end of our investigation period (2018), Denmark has become one of the most restrictive system in Europe. What has happened?

Figure 2. Immigrant welfare rights, immigration dynamics and PRRP electoral pressure in Denmark 1980–2018. Notes: Net-migration rate, immigrant and vote share of PRRPs are all depicted in percentages (0–100). Change in IWR is recalled and can range from −100 (withdrawal of all rights) to 100 (granting all possible rights).

We argue, the transformation of immigrant rights in Denmark can be seen as a development in three steps: (1) The early politicization of immigrant welfare rights, (2) shifted partisan stances, and (3) outbidding on the restrictions of immigrant rights.

The politicization of immigration in Denmark

The 1983 Aliens Act offered very extensive liberal residence conditions and access to rights. Despite this act being pushed through by the left-wing opposition parties, a broad majority – including the ruling coalition of Christian democrats, liberals and conservatives – embraced the liberalization of the immigration law in general (see also Brøcker, Citation1990; taken from Green-Pedersen & Odmalm, Citation2008). However, in 1983 Denmark also experienced a ‘considerable’ refugee inflow from the Middle East (Green-Pedersen & Odmalm, Citation2008, p. 371). The populist radical right Progress Party, but also prominent figures in the conservative party (Konservative Folkeparti) and liberal party (Venstre)Footnote11 used the opportunity to launch xenophobic campaigns. In autumn 1985, the Social Democratic Party moved to more skeptical positions too. Social Democrat mayors had expressed concern over problems with integration, especially in areas of social housing in the municipalities surrounding Copenhagen. In December 1985, the four parties of the government, together with the Social Democratic Party and the Progress Party, agreed that further restrictions to the lenient provisions in the Aliens Act were necessary. The majority held by the political parties which had originally carried the liberal Aliens Act had collapsed.

During the early 1990s, the question of how to deal with Palestinian asylum-seekers increased the salience of immigration again. The church, with the Christian Democratic Party’s support, granted around 100 rejected asylum seekers ‘church asylum’ despite this not being a legal category in Denmark. Like in 1983 for the immigration reform, left-wing parties again organized a majority granting all 321 rejected Asylum seekers special and permanent permits. The debate about church asylum moved substantial public attention to the issue of immigration. In short, the 1980s and early 1990s brought about a politicization of immigration in general and IWR in particular.

Shifted partisan stances

The political landscape had started to shift. In 1995, the populist radical right Progress Party was splintered and the Danish People’s Party (DF) emerged. The DF almost exclusively focused on immigration issues but at the same time managed to present themselves as a reliable partner to the mainstream right (Rydgren, Citation2005). The electoral support for the DF increased (7.4 percent in the 1998 election) and the liberals and conservatives substantially changed the emphasis from immigrant rights to duties and started to reopen the question of naturalization (Jensen, Citation2000). This resulted in the centre-left governments (Nyrup Rasmussen I–IV) from 1993 to 2001 facing constant confrontations on the matter of immigration from the respective PRRP,Footnote12 the liberals and conservatives.

In this period the Social Democrat-led government had turned to propose and implement general welfare state retrenchment (Jønsson & Petersen, Citation2012, p. 123), which weakened their support in the working-class electorate. The DF was able to successfully take this opportunity to present itself as a party concerned with workers’ interests. Whereas its predecessor, the Progress Party, was known for its tax-reduction platform, the DF voiced welfare state protecting positions and argued that the main threat to the Danish welfare state was continued immigration (Jønsson & Petersen, Citation2012; Rydgren, Citation2004). Moreover, it positioned itself as an alternative to the Social Democrats, whose leadership were attacked by the DF party as being far removed from working-class realities (see Rydgren, Citation2004, p. 487). Due to that electoral pressure, the Social Democrat-led cabinet under Nyrup Rasmussen designed a law that parliament passed in 1998 and which reduced benefits for refugees and asylum seekers (Green-Pedersen & Odmalm, Citation2008, p. 375).

The opposition was successful in turning immigration into the dominant issue for the 2001 election, too. The social democrats experienced a historic defeat losing executive power to a coalition of the liberals and the conservatives (Blomqvist & Green-Pedersen, Citation2004, p. 593). Yet, liberals and conservatives did not command a parliamentary majority, which was provided informally by the DF. In the end of the 1990, we observe the finalization of partisan stances on immigrant rights. Unambiguous supporters of immigrant rights from 1980 to 2018 have been the social liberals, the socialist and the Christian democrats. Liberals and Conservatives started out as supporters of immigrant rights but gradually shifted to adversarial positions during the 1980s. Equally with a bit of delay social democrats moved from unambiguous support to ambiguous positions during the 1980s and started to support restrictive measures since the late 1990s. The populist radical right (PP and later DF) always and unambiguously mobilized against immigrant welfare rights. Combined with the raising electoral support for the populist right and the decline of support for social democrats, support for immigrant rights never again obtained parliamentary majority support in Denmark. On the contrary, Denmark entered a phase of outbidding on ever more restrictions on immigrant welfare rights.

Outbidding on the restrictions of immigrant rights

As an important supporter of the government, many of the Danish People’s Party’s demands for a stricter immigration policy became law. For example, the 2002 reform entailed that newly arriving immigrants’ benefits were lowered (‘starting help’), and getting access to the regular social assistance benefit was made dependent on having resided in Denmark for seven yearsFootnote13 (Mouritsen & Olsen, Citation2013). Furthermore, several restrictions regarding family reunification were introduced: Family reunification was denied to sponsors who had received Danish social assistance within a year of their application. The sponsor was furthermore required to show bank documentation that they could provide financially for their partner (Andersen, Citation2007, p. 258). Family unification before the age of 24 became virtually impossible and married couples had to document a closer connection to Denmark than to the homeland of the foreign spouse (Green-Pedersen & Odmalm, Citation2008).

After the election in 2007, the liberal–conservative Løkke Rasmussen I cabinet was again supported by the Danish People’s Party (which received 13.9 percent of the vote). The government enacted Law No. 982 in October 2009, five months after being inaugurated into government. The act substantially increased the residence requirements for eligibility to pensions for all types of immigrants (minimum of 10 years legal residence to receive a pension at all and 40 years for a full pension). The same cabinet adopted further laws in December 2010 and January 2011 which effectively restricted newly arrived immigrant families from the child and youth benefits until they had resided in Denmark for two years (Laws No. 1609 and No. 1382).

In the 2015 parliamentary election, the DF received almost 21 percent of the vote. After the 2015 election, the cabinet of Løkke Rasmussen II (constituted by the Liberal Party and supported by the Danish People’s Party) has lowered social entitlements for immigrants once again (Jørgensen & Thomsen, Citation2016, p. 331). DF’s electoral rise stopped in 2019 when the Danish Social Democrats adopted several of the core immigration positions of the DF. On that ticket, social democrats made it back into government. One of the controversially discussed issues which became law is the so-called ‘action plan’ to get rid of ‘ghettos’.Footnote14 It links non-compliance with the requirement that immigrant children must be separated from their families for at least 25 hours a week to a stoppage of welfare payments.

Summarizing the case study evidence

When linking the Danish case back to the six hypotheses that were formulated in the theoretical section of the paper we can summarize as follows. The Danish example confirms that PRRPs in government play a crucial role in the retrenchment of immigrant rights. In all instance that they participated in government, substantial restrictions were introduced. Conservatives and liberals on the other hand have a very volatile track record, having been both represented in governments that conducted expansions as well as in governments that conducted restrictions. Christian democrats finally were never part of a government that retrenched immigrant welfare rights. It is however important to point out that due to the low electoral support, the Christian democrats never played a crucial role in the organization for or against legislation that affected immigrant welfare rights, but we discussed an instance where Christian democrats supported the Church’s attempts to protect the rights of immigrants. Christian democrats’ position on immigrant rights in fact have remained very liberal even until 2021.Footnote15 The set of Hypotheses 1–3 thus is corroborated by the qualitative findings.

In Hypothesis 4, we also expected that when governing with PRRPs, conservatives and liberals would support PRRP demands to cut IWR to a larger extent than Christian democrats. Indeed, being in coalition with a PRRP led conservatives and liberals to support anti-immigrant policy making. In the time span we investigate, there was no coalition between Christian democrats and a PRRP. On the one hand, this makes it harder to fully test Hypothesis 4. However, we would argue that the fact that Christian democrats refrained from participating in such a coalition can be read as support of the assumption that they are less inclined to collaborate with the PRRP than the other two mainstream parties.

We now turn to Hypothesis 5 which concerns the impact of PRRP’s rising vote share. In the quantitative analyses we did not find support for this hypothesis. The case of Denmark however indicates that indeed, through their electoral rise PRRPs exercise pressure that create cracks within the liberals, conservatives, and to a lesser extent within the Social democrats. In contrast, there is less evidence that Socialists, social liberals, and Christian democrats give up on their more liberal and humanitarian perspective that informed their support for immigrant welfare rights in Denmark. The case study also sheds light on why these processes can hardly be captured in a quantitative design. First, not only the mainstream right parties seem to be affected by the pressure PRRPs exert. Also, social democrats have reacted to populist radical right parties in Denmark. Furthermore, even though most parties very early on were conscious of the fact that the PRRP had entered the arena it took time until this had translated into shifting partisan positions and even more time to trigger mainstream parties to support or even enact legislation that restrict immigrant welfare rights. In short, the time that unfolds between the emergence of a successful PRRPs and visible policy reactions is long. In Denmark it took PRRPs about 16 years until the majorities for liberal immigrant rights have been turned into majorities for more restrictions. Only about after these 16 years a phase of outbidding on the discrimination of immigrants has started and runs until today.

Hypothesis 6 finally dealt with the role rising immigration, both in regard to stocks and flows, plays for mainstream right policy making. The evidence from the quantitative models was mixed, and to some extent ran counter to our hypotheses. The case study again helps to shed light on these findings. First, key events of the politicization of immigrants’ rights can hardly be captured with comparable immigration data. The ‘wave’ of asylum seekers that started considerable political debate in Denmark involved several thousand refugees. In the case of the ‘church asylum’ discussion in 1991 it concerned about 300 Palestinians. For a comparative measures of immigration stock and flow as we employ it in the quantitative analyses, these numbers are too small to make a difference. The case study evidence however showed that such levels of immigration were big enough to trigger fierce debates. In short, absolute numbers of immigration may not be a good measure to capture the politicization of the issue. Second, the politicization of immigration rights is accelerated by its instrumentalization of the populist radical right.

Conclusion

In this paper we have argued that a thorough understanding of changes in immigrant welfare rights needs to consider a partisan perspective. We hypothesized that PRRPs are the main drivers of retrenchment, whereas Christian democrats tend to be supporters of more generous rights. Liberals and conservatives tend to lean towards retrenchment, but the issue does not take a pivotal strategic position for them. Accordingly, we also hypothesized that liberals and conservatives will more likely succumb to both direct and indirect PRRP pressure. Finally, we also formulated hypotheses on how increases in immigrant stocks and flows will affect the three mainstream right parties differently.

To scrutinize these hypotheses, we employed a mixed-method design. Our evidence from the quantitative and qualitative analyses consistently supports the claim that PRRPs in governments are the predominant drivers in the retrenchment of immigrants’ welfare rights. We also found some evidence that PRRPs retrenchment efforts are most successful when they are governing with conservatives and liberals. In regard to the effects of electoral pressure and immigration dynamics the quantitative evidence was however mixed and did not clearly support or refute our hypotheses. The qualitative evidence from several cabinet cases in Denmark showed that PRRPs do exert indirect influence on positions and policy making of mainstream parties though. Furthermore, the qualitative evidence underlined that such contagion effects are in fact not limited to the mainstream right. The case study also illustrated that immigration matters, albeit not necessarily objective, absolute numbers.

The study thus contributes to the literature in a number of ways. We show that the rise of PRRPs has a notable effect on policy making at the intersection of immigration and welfare policies. The results, however, also underline that partisan stances differ not only across left and right but also within the different party families of the right, and that PRRP influence on policy making is dependent on their respective coalition partners. Furthermore, the paper shows that the effects of PRRP electoral pressure and immigration dynamics are complex and might not always be fully captured by quantitative designs. What is more, the case study indicates that it might be the pressure PRRPs exercise through their electoral rise in combination with immigration dynamics that create cracks within the liberals, conservatives, and to a lesser extent within the Social democrats. It thus seems worthwhile to further investigate how PRRPs might use immigration related events to successfully implement their policy preferences when in government.

In this vein, while our results contribute to the literature in a number of ways, we also see several avenues for further research. In regard to the role of immigration, we would encourage further research to differentiate between types of immigration flows, notably from within and from outside the EU. Second, merging EU migration with third country national (TCN) migration may induce bias, as the rights of EU migrants are not solely governed at the national level. Methodological nationalism might be misleading for a second reason. In some cases, policy authority lies with regions (Garritzmann et al. Citation2021; Zuber Citation2022). Third, further analyses could help to unveil whether immigration affects parties on the right – and left – differently. Fourth, in this paper we could not study in detail factional differences within parties. Future research could thus be directed at uncovering to what extent immigration and the electoral rise of PRRPs influences the balance of power of different factions within mainstream right parties. Finally, it seems worthwhile to delve deeper into the multi-dimensionality of the construct ‘immigrant welfare rights’. The robustness checks have indicated that there indeed seem to be some difference between parties in regard to which aspects of rights they are likely to cut, respectively expand. We thus encourage a more fine-grained analysis of partisan differences on different elements of welfare rights of immigrants in future research.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (107.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Eloisa Harris and Jakob Henninger as well as the team of student assistants supporting the data collection for the indicators on immigrant welfare rights. We also thank the editors, and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive and critical comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Friederike Römer

Friederike Römer is a Principal Investigator at the Collaborative Research Centre 1342 ‘Global Dynamics of Social Policy’ at the Unversity of Bremen, Germany.

Leonce Röth

Leonce Röth is a senior researcher at the University of Cologne and the University of Siegen (both Germany).

Malisa Zobel

Malisa Zobel was a senior advisor at the Humboldt-Viadrina Governance Platform. She is now a guest researcher at the European University Viadrina and works at the German Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth.

Notes

1 Compare also Bale and Kaltwasser (Citation2021).

2 Even though there is no clear empirical evidence that cuts in immigrant welfare rights will decrease immigrant inflows, the so called ‘welfare magnet’ hypothesis features prominently in the public debate and has been used to justify cuts in IWR (see e.g., Carmel & Sojka, Citation2021).

3 Religion, however, influences their conception of the appropriate balance between the welfare state and the market (Jensen, Citation2014). Their emphasis is on security rather than redistribution (Huber et al., Citation1993, p. 741).

4 Duncan and Van Hecke (Citation2008) find few differences between mainstream right-wing parties in this regard.

5 These are: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and United Kingdom. The logic of country selection is driven by most-similar systems design, all countries being established democracies with relevant welfare states.

6 We demonstrate in the Online Appendix VIII that we would have come to very different results using levels as the dependent variable.

7 We have opted for UN immigration data because they have the closest temporal and geographical overlap with the scope of our analysis. The data however do not allow to differentiate between intra-EU and third country national migration flows/migrants.

8 ‘Pure’ left governments have on average a positive effect on IWR which supports choosing this cabinet type as a benchmark for comparison.

9 This seemed especially relevant in the case of Switzerland, where in line with the consociational governance approach of the country, the so called ‘magic formula’ granted virtually every party participation in voluntary grand coalitions, including the SVP. However, since 2007 the magic formula was repeatedly suspended, for example when SVP leader Blocher was denied a seat in the Federal Council. Because the SVP is considered to be a PRRP only since 1999 and the SVP has not always been part of the Federal Council after 2007, we have variation over time within Switzerland. Omitting Switzerland also does not affect our results.

10 For a discussion of why there is often only limited evidence of partisan influence see also Hampshire and Bale (Citation2015).

11 The Danish Social Liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) aligned clearly with the left on these issues and remained very liberal on immigrant rights throughout the entire period of our investigation.

12 In the first years the progress Party and since 1995 the DF since 1995.

13 This applies to both Danish citizens and immigrants that do not hold the Danish citizenship.

14 A legal term used by Danish authorities for districts in which a large proportion of inhabitants are of lower socio-economic status, and where the majority population is of non-Western ethnicities.

15 Compare official documents of the KD (2021; https://kd.dk/politik-flygtninge-integration/).

References

- Abou-Chadi, T. (2016). Niche party success and mainstream party policy shifts–how green and radical right parties differ in their impact. British Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123414000155

- Abou-Chadi, T., Cohen, D., & Wagner, M. (2021). The centre-right versus the radical right: The role of migration issues and economic grievances. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 366–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853903.

- Akkerman, T. (2012). Comparing radical right parties in government: Immigration and integration policies in nine countries (1996–2010). West European Politics, 35(3), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665738

- Allan, J. P., & Scruggs, L. (2004). Political partisanship and welfare state reform in advanced industrial societies. American Journal of Political Science, 48(3), 496–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00083.x

- Andersen, J. G. (2007). Restricting access to social protection for immigrants in the Danish welfare state. Benefits, 15(3), 257–269.

- Andersen, J. G., & Bjørklund, T. (1990). Structural changes and new cleavages: The progress parties in Denmark and Norway. Acta Sociologica, 33(3), 195–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169939003300303

- Armingeon, K., Wenger, V., Wiedemeier, F., Isler, C., Knöpfel, L., Weisstanner, D., & Engler, S. (2020). Comparative political data set 1960-2018. Institute of Political Science, University of Berne Falls. https://www.cpds-data.org/index.php/data.

- Arzheimer, K., & Carter, E. (2009). Christian religiosity and voting for West European radical right parties. West European Politics, 32(5), 985–1011. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380903065058

- Bale, T. (2003). Cinderella and her ugly sisters: The mainstream and extreme right in Europe’s bipolarising party systems. West European Politics, 26(3), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380312331280598

- Bale, T. (2008). Turning round the telescope. Centre-right parties and immigration and integration policy in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701847341

- Bale, T., & Bergman, T. (2006). Captives no longer, but servants still? Contract parliamentarism and the new minority governance in Sweden and New Zealand. Government and Opposition, 41(3), 422–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2006.00186.x

- Bale, T., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2021). Riding the populist wave: Europe’s mainstream right in crisis. Cambridge University Press.

- Banting, K. (2000). Looking in three directions: Migration and the European welfare state in comparative perspective. In M. Bommes (Ed.), Immigration and welfare: Challenging the borders of the welfare state (pp. 13–33). Routledge.

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082979

- Beramendi, P., Häusermann, S., Kitschelt, H., & Kriesi, H. (Eds.). (2020). The politics of advanced capitalism. Cambridge University Press.

- Bjerre, L., Helbling, M., Römer, F., & Zobel, M. (2015). Conceptualizing and measuring immigration policies: A comparative perspective. International Migration Review, 49(3), 555–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12100

- Bjerre, L., Römer, F., & Zobel, M. (2019). The sensitivity of country ranks to index construction and aggregation choice: The case of immigration policy. Policy Studies Journal, 47(3), 647–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12304

- Blomqvist, P., & Green-Pedersen, C. (2004). Defeat at home? Issue-ownership and social democratic support in Scandinavia. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 587–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00137.x

- Boräng, F. (2015). Large-scale solidarity? Effects of welfare state institutions on the admission of forced migrants. European Journal of Political Research, 54(2), 216–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12075

- Brøcker, A. (1990). Udlændingelovgivningi Danmark 1983–1986: Faktorer i den politiske beslutningsproces. Politica, 22(3), 332–345. https://doi.org/10.7146/politica.v22i3.69227

- Brubaker, W. R. (Ed.). (1989). Immigration and the politics of citizenship in Europe and North America. University press of America.

- Carmel, E., & Sojka, B. (2021). ‘Beyond welfare chauvinism and deservingness. Rationales of belonging as a conceptual framework for the politics and governance of migrants’ rights’. Journal of Social Policy, 50(3), 645–667. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279420000379

- Chueri, J. (2021). Social policy outcomes of government participation by radical right parties. Party Politics, 27(6), 1092–1104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820923496.

- Delgado, C. N. (2000). Reforms and Counter - Reforms in spanish law on aliens. Spanish Yearbook of International Law, 7(1), 51–77.

- Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2020). Parliaments and governments database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies. Development version.

- Duncan, F., & Van Hecke, S. (2008). Immigration and the transnational European centre-right: A common programmatic response? Journal of European Public Policy, 15(3), 432–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701847705

- Engler, S., & Weisstanner, D. (2021). The threat of social decline: Income inequality and radical right support. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1733636

- Garritzmann, Julian L, Röth, Leonce, & Kleider, Hanna. (2021). Policy-Making in Multi-Level Systems: Ideology, Authority, and Education. Comparative Political Studies, 54(12), 2155–2190. http://doi.org/10.1177/0010414021997499

- Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. The British Journal of Sociology, 68(1), 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12319

- Gidron, N., & Ziblatt, D. (2019). Center-right political parties in advanced democracies. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-090717-092750

- Givens, T., & Luedtke, A. (2005). European immigration policies in comparative perspective: Issue salience, partisanship and immigrant rights. Comparative European Politics, 3(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110051

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Odmalm, P. (2008). Going different ways? Right-wing parties and the immigrant issue in Denmark and Sweden. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(3), 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701847564

- Hadj Abdou, L., Bale, T., & Geddes, A. P. (2022). Centre-right parties and immigration in an era of politicisation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853901 .

- Hainmueller, J., & Xu, Y. (2013). Ebalance: A stata package for entropy balancing. Journal of Statistical Software, 54(7), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v054.i07

- Hampshire, J., & Bale, T. (2015). New administration, new immigration regime: Do parties matter after all? A UK case study. West European Politics, 38(1), 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.925735

- Häusermann, S., Picot, G., & Geering, D. (2013). Review article: Rethinking party politics and the welfare state – Recent advances in the literature. British Journal of Political Science, 43(1), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000336

- Helbling, M., Bjerre, L., Römer, F., & Zobel, M. (2017). Measuring immigration policies: The IMPIC database. European Political Science, 16(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2016.4

- Huber, E., Ragin, C., & Stephens, J. D. (1993). Social democracy, Christian democracy, constitutional structure, and the welfare state. American Journal of Sociology, 99(3), 711–749. https://doi.org/10.1086/230321

- Huber, E., & Stephens, J. (2001). Development and crisis of the welfare state: Parties and policies in global markets. University of Chicago Press.

- Jensen, B. (2000). De fremmede i dansk avisdebat. Spektrum.

- Jensen, C. (2014). The right and the welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jønsson, H. V., & Petersen, K. (2012). A national welfare state meets the world. In: Immigration policy and the scandinavian welfare state 1945–2010. Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship Series. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Joppke, C. (2007). Beyond national models: Civic integration policies for immigrants in Western Europe. West European Politics, 30(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380601019613

- Jørgensen, M. B., & Thomsen, T. L. (2016). Deservingness in the Danish context: Welfare chauvinism in times of crisis. Critical Social Policy, 36(3), 330–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018315622012

- Kalyvas, S., & Van Kersbergen, K. (2010). Christian democracy. Annual Review of Political Science, 13(1), 183–209. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.021406.172506

- Kitschelt, H., & McGann, A. J. (1995). The radical right in Western Europe: A comparative analysis. University of Michigan Press.

- Koning, E. A., & Banting, K. G. (2013). Inequality below the surface: Reviewing immigrants’ access to and utilization of five Canadian welfare programs. Canadian Public Policy, 39(4), 581–601. https://doi.org/10.3138/CPP.39.4.581

- Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (2003). New politics and class politics in the context of austerity and globalization: Welfare state regress in 18 countries, 1975-95. The American Political Science Review, 97(3), 425–446.

- Lutz, P. (2019). Variation in policy success: Radical right populism and migration policy. West European Politics, 42(3), 517–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1504509

- Madeley, J. (2004). Life at the northern margin. Christian democracy in Scandinavia. In S. van Hecke & E. Gerard (Eds.), Christian democratic parties in Europe since the end of the cold war (pp. 217–242). Leuven University Press.

- Marcinkiewicz, K., & Dassonneville, R. (2021). Do religious voters support populist radical right parties? Opposite effects in Western and east-central Europe. Party Politics, 28(3), 444–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820985187.

- Minkenberg, M. (2001). The radical right in public office: Agenda–setting and policy effects. West European Politics, 24(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380108425462

- Montgomery, K. A., & Winter, R. (2015). Explaining the religion gap in support for radical right parties in Europe. Politics & Religion, 8(2), 379–403. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048315000292

- Mouritsen, P., & Olsen, T. V. (2013). Denmark between liberalism and nationalism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(4), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.598233

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Pearl, J. (2009). Causality. Cambridge University Press.

- Römer, F. (2017). Generous to all or ‘insiders only’? The relationship between welfare state and immigrant welfare rights. Journal of European Social Policy, 27(2), 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717696441

- Römer, F., Henninger, J., Harris, E., & Missler, F. (2021). The migrant social protection data set (MigSP). Technical Report. SFB 1342 Technical Paper Series 10. https://www.socialpolicydynamics.de/sfb-1342-publikationen/sfb-1342-technical-paper-series

- Röth, L., Afonso, A., & Spies, D. (2018). The impact of populist radical right parties on socio-economic policies. European Political Science Review, 10(3), 325–350. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773917000133

- Rydgren, J. (2004). Explaining the emergence of radical right-wing populist parties: The case of Denmark. West European Politics, 27(3), 474–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/0140238042000228103

- Rydgren, J. (2005). Is extreme right-wing populism contagious? Explaining the emergence of a new party family. European Journal of Political Research, 44(3), 413–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00233.x

- Sainsbury, D. (2012). Welfare states and immigrant rights: The politics of inclusion and exclusion. Oxford University Press.

- Schain, M. A. (2008). The politics of immigration in France, Britain, and the United States: A comparative study. Springer.

- Schmitt, C., & Teney, C. (2019). Access to general social protection for immigrants in advanced democracies. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718768365

- Schumacher, G., & Van Kersbergen, K. (2016). Do mainstream parties adapt to the welfare chauvinism of populist parties? Party Politics, 22(3), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068814549345

- Schumacher, G., Vis, B., & Van Kersbergen, K. (2013). ‘Political parties’ welfare image, electoral punishment and welfare state retrenchment.’. Comparative European Politics, 11(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.5

- Siegers, P., & Jedinger, A. (2021). Religious immunity to populism: Christian religiosity and public support for the alternative for Germany. German Politics, 30(2), 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2020.1723002

- Soysal, Y. N., & Soyland, A. J. (1994). Limits of citizenship: Migrants and postnational membership in Europe. University of Chicago Press.

- Bale, T., & Krouwel, A. (2013). Down but not out: A comparison of Germany's CDU/CSU with christian democratic parties in Austria, Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands. German Politics, 22(1-2), 16–45.https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2013.794452.

- Van Kersbergen, K. (1995). Social capitalism: A study of Christian democracy and of the welfare state. Routledge.

- Van Spanje, J. (2010). Contagious parties: Anti-immigration parties and their impact on other parties’ immigration stances in contemporary Western Europe. Party Politics, 16(5), 563–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068809346002

- Weller, N., & Barnes, J. (2016). Pathway analysis and the search for causal mechanisms. Sociological Methods & Research, 45(3), 424–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114544420

- Zaslove, A. (2004). Closing the door? The ideology and impact of radical right populism on immigration policy in Austria and Italy. Journal of Political Ideologies, 9(1), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356931032000167490

- Zaslove, A. (2006). The politics of immigration: A new electoral dilemma for the right and the left? Review of European and Russian Affairs, 3(2), 10–36. https://doi.org/10.22215/rera.v2i3.172

- Zuber, Christina Isabel. (2022)). Ideational Legacies and the Politics of Migration in European Minority Regions. Oxford University Press.