?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Televised debates represent an integral part of election campaigns and with the introduction of the Spitzenkandidaten process also became part of the European Parliament (EP) elections campaign. Various characteristics of EP elections such as a generally lower (perceived) relevance of and participation in the elections, and also the relatively unknown lead candidates running for Commission President assign TV debates a crucial role to inform European citizens and assist them in their voting decision. Focusing on the second edition of the ‘Eurovision debate’ during the 2019 EP elections campaign, this article examines the impact of debate exposure on both the decision to turn out and party choice. The study uses original flash survey data collected after the debate in five countries (DE, DK, ES, HU, NL). These data are part of a larger panel-survey study, which allows to examine immediate effects in the days after the debate and also for the eventual decision on Election Day. Although citizens' debate exposure varies considerably across countries, and watchers further differ in their evaluations of the candidate performances, the results show a surprisingly negative effect of debate exposure on turnout, especially among more interested citizens, and basically no effects on party choice.

Introduction

For the first time in the history of European Parliament (EP) elections, pan-European TV debates were aired across the European Union (EU) in 2014. The most important and most widely covered debate was the so-called ‘Eurovision’ debate. Like none of the other campaign events, this TV debate stands for the 2014 introduced Spitzenkandidaten (lead candidates) process and accompanying personalization of EU politics (Dinter & Weissenbach, Citation2015). This new process raised the expectations among EU citizens that the ‘winning’ lead candidate of the EP elections will become the new President of the European Commission. While this expectation was met in 2014, the mixed findings of the process' success to raise citizens' interest in EU politics and to mobilize EP election participation could not yet determine the overall relevance of the Spitzenkandidaten process and related activities (e.g., Hobolt, Citation2014; Schmitt et al., Citation2015; Treib, Citation2014). In fact, and due to the innovation of the Spitzenkandidaten and their participation in TV debates for the first time in 2014, scholars such as Schmitt et al. (Citation2015) expected a potentially greater effect in the following 2019 edition.

Unlike the Spitzenkandidaten process more generally, the specific Eurovision debate exerted already various effects in 2014. Voters who were exposed to the debate showed increasing interest in the campaign, gained information about EU politics and changed their attitudes towards the participating candidates (Baboš & Világi, Citation2018; Dinter & Weissenbach, Citation2015; Maier et al., Citation2018). However, none of the extant studies analysed the ultimate goal of any electoral campaign (in detail), namely citizens' decisions to vote and whom to vote. The analysis of these decisions following people's exposure to the TV debate, in combination with a potentially increased relevance of the Spitzenkandidaten in the second edition 2019, is at the core of this article. The goal is to examine whether the lead candidates' discussions in the Eurovision debate during the 2019 EP election campaign mobilized citizens to turn out and whether the debate had influence on voters' party choice. Debate influence may have occurred both as direct effects, that is, because citizens watched the debate, and as indirect effects via exposure to subsequent media coverage of the debates, and may have been moderated by political sophistication. In the context that EP elections are still characterized as ‘simultaneous national elections’ in each member state (Reif & Schmitt, Citation1980, 8), the Eurovision debate ‘provides the opportunity to compare the impact of an uniform campaign stimulus across different EU member states’ (Maier et al., Citation2018, 621). The article's consideration of five EU countries provides various (descriptive) country comparisons and a common cross-country analysis.

The article contributes to extant literature in four ways. First, it contributes to the research field of TV debates and follows the request by McKinney and Carlin (Citation2004) to enrich the literature with more research on international debates, of which the pan-European Eurovision debate is a prime example. Second, this article adds to previous research that examined the impact of debate formats other than the most common head-to-head format between two main contenders only (e.g., Goldberg & Ischen, Citation2020). The multi-candidate Eurovision debate format is similar to formats in US primaries or in various multi-party systems. For the specific research about EP elections, a third contribution is the enrichment of the scarce extant evidence by focusing on debate effects on (actual) voting behaviour, particularly relevant in the context of common short-lived effects of TV debates (Lindemann & Stoetzer, Citation2021; Palacios & Arnold, Citation2021). While debate effects have been studied extensively at the national level, they are under-explored for EP elections debates. A final fourth contribution is the provision of cross-sectional evidence of the population at large by relying on flash surveys embedded in a panel structure instead of extant experimental studies focussing on specific subgroups such as student samples.

The article relies on data from five EU countries (DE, DK, ES, HU and NL) collected around the 2019 EP elections. Original flash survey data collected right after the debate are linked to a larger panel study, with voting behaviour measured immediately after the debate (as intentions) and in the subsequent post-election wave (as self-reported actual behaviour). The accompanying contextual information of TV coverage of the Eurovision debate first shows significant differences between countries, which are translated into different levels of debate exposure among respondents. Debate watchers further differ in their perceptions of the candidates' debate performance across countries. Yet, the conducted regression models do not show the expected effects of individual differences in debate exposure on voting behaviour. While the results show surprisingly (weak) negative effects on mobilization, particularly among politically interested respondents, there are basically no effects of debate watching on party choice.

The Spitzenkandidaten process in EP elections

One of the key developments of politics in advanced democracies over the last decades is political personalization (van Aelst et al., Citation2012). In the European context, the 2014 European election campaign marked a crucial step towards (further) personalization of EU politics. Indicated by the slogan ‘this time it's different’, the European Parliament argued that, when casting their vote in the 2014 elections, European citizens would have a say in determining the next Commission President. The process of European parties appointing pan-European ‘lead candidates’ and the implicit expectation that the lead candidate of the party winning the most seats in the EP elections will become the new Commission President became known as the Spitzenkandidaten process.Footnote1 The main goal of the, in theory, indirect vote of the Commission President by the electorate was ‘to personify the EU’ and to make the EU polity ‘more palatable to voters’ (Popa et al., Citation2016, 469). The latter included to foster political competition at the EU level and to increase the legitimacy of the Commission, but also to increase the general interest and participation in EU democracy and hence to fight the often proclaimed democratic deficit of the EU (cf. Hobolt, Citation2014; Maier et al., Citation2018; Schmitt et al., Citation2015). Given citizens' little knowledge about the Spitzenkandidaten before the campaign (Popa et al., Citation2020), the media play a crucial role for the success of the process, in particular to provide information for citizens to get aware of the candidates (Gattermann & de Vreese, Citation2020).

Following the lead candidates' substantial presence during the EP elections campaign, e.g., in TV debates, rallies or interviews, Nulty et al. (Citation2016) argue that the candidates fulfilled the expectation of playing a major role during the 2014 campaign. For the 2019 edition, Richter and Stier (Citation2022) show that exposure to candidate-specific news – offline or online – helped to increase citizens' candidate knowledge, with the relatively strongest influence from TV debates, thus being the most personalized media source. The EP itself also evaluated the Spitzenkandidaten process as successful by fostering the political awareness of European citizens (Gattermann, Citation2020). In contrast, other studies paint a more pessimistic picture. Based on cross-national data from 15 EU member states, Hobolt (Citation2014) reports (very) low levels of awareness of lead candidates among the European electorate. The study by Schmitt et al. (Citation2015) equally reports low levels of citizens' recognition of the lead candidates, based on 2014 European Election Voter Study data across all 28 member states. For instance, only around 18% recognized Jean-Claude Juncker and 17% recognized Martin Schulz. However, recognizing these most well-known candidates significantly and substantively increased the person's likelihood to vote by around four to seven percentage points. The authors conclude that the growing campaign personalization by the Spitzenkandidaten had a substantial effect on turnout, but acknowledge the overall limited effect given the low levels of candidate recognition to begin with. The conclusion by Hobolt (Citation2014, 1530) is more pessimistic by stating that ‘the elections have not brought about the genuine electoral connection between voters and EU policy-making that was hoped for’.

TV debates as campaign events

For decades, televised debates represent an integral part of campaigns for national elections and are often considered as the ‘focal point’ for campaigns (Carlin, Citation1992, 263). In comparison to other campaign events, TV debates reach large audiences and attract the greatest media coverage (e.g., McKinney & Carlin, Citation2004). They are further easily accessible for the electorate and provide crucial information about important issues and the major candidates that help to inform people's voting decision (Benoit & Hansen, Citation2004; Maier et al., Citation2014; McKinney & Carlin, Citation2004). TV debates as representing more traditional media are also less demanding than online media sources due to the latter's more dynamic and unstructured nature (Richter & Stier, Citation2022). From a party or candidate perspective, TV debates are particularly interesting as debate watchers have a hard time to escape the messages of the political opponent (Maier et al., Citation2016).

In the context of EP elections and as one aspect of the newly introduced Spitzenkandidaten process, TV debates among the lead candidates competing for the position of Commission President were aired for the first time in 2014. The pan-European broadcasting of these debates is argued to be particularly important because it can serve as a common point of reference for EU citizens – and create an EU wide common public sphere – in the context of otherwise still national EP campaigns (Maier et al., Citation2018; Schmitt et al., Citation2015). TV debates may further be a crucial information source as the salience of – and potential learning about – the Spitzenkandidaten (system) was limited in/via parties' communication efforts (Popa et al., Citation2020). While various televised debates took place, the most important and most widely aired one was the so-called ‘Eurovision debate’ on 15 May 2014, in which all of the major lead candidates participated (Maier et al., Citation2016).

Generally, the influence of TV debates (on voting behaviour) can be distinguished into direct and indirect effects (Blais & Boyer, Citation1996; Goldberg & Ischen, Citation2020). Direct effects occur when a citizen watches a debate and the content of what she sees influences her voting intention/decision. While early research from the US reported limited direct effects of TV debates, mainly in the form of strengthening extant voting preference (e.g., Sigelman & Sigelman, Citation1984), a growing number of more recent studies – also outside the US – found evidence for direct effects of watching a TV debate on voters (e.g., Blais & Boyer, Citation1996; Maurer & Reinemann, Citation2013; Pattie & Johnston, Citation2011). Indirect effects stem from intermediaries, most prominently exposure to subsequent media coverage of the debates. Studies equally provide evidence of such indirect effects on voting behaviour – in particular media coverage about candidate performance, the presentation of a debate winner and discussing the potential impact on the election (e.g., Blais & Boyer, Citation1996; Maier et al., Citation2014; McKinney & Carlin, Citation2004).

The few studies examining TV debates during the 2014 EP elections campaign focused on the aforementioned Eurovision debate (Baboš & Világi, Citation2018; Dinter & Weissenbach, Citation2015; Maier et al., Citation2018, Citation2016). All studies focused on direct watching effects by relying on experimental data. Maier et al. (Citation2018) found comparative evidence that exposure to the debate resulted in a perceived higher political competition, but also an information gain about EU politics and stronger interest in the campaign (see also Palacios & Arnold, Citation2021). The German study by Dinter and Weissenbach (Citation2015) found strongest effects on attitudes toward the candidates and increased feelings among debate watchers that one can actually influence European politics through voting. By comparing the 2014 Eurovision debate with the TV debate for the 2016 national elections in Slovakia, Baboš and Világi (Citation2018)'s results support the claim that debate effects are stronger with relatively unknown candidates. Whereas watching the Eurovision debate had an effect on (candidate) preference formation in the EU, no such effect was observable for the national election context. Notwithstanding these preliminary findings, what is missing so far is empirical evidence about the influence of the Eurovision debate on electoral participation and party choice, the ultimate goal of campaign efforts by parties and candidates.

Theoretical expectations and hypotheses

In his classic piece, Chaffee (Citation1978, 342) mentioned four conditions under which TV debates may be especially influential: (a) at least one of the candidates is not well known, (b) many voters are undecided, (c) the contest appears close and (d) party allegiances are weak. European election campaigns fulfil basically all these conditions, maybe less so the closeness of the contest, speaking for strong possible TV debate effects. Especially the first condition appears relevant as information acquisition and its impact is more relevant for less known candidates (Holbrook, Citation1999). In the US context, authors such as Yawn et al. (Citation1998) argue that primary debates – in comparison to actual presidential debates – are more influential due to the audience's no or little information about the contenders and related potential for new or surprising information that may influence the voters (cf. Baboš & Világi, Citation2018). This logic for US primary elections, seen as second-order elections in the US, may equally apply to the (second-order) European context in which most of the lead candidates are relatively unknown (Gattermann & de Vreese, Citation2020; Hobolt, Citation2014). Related to Chaffee's second and fourth condition, strong partisanship is not that common in Europe and potentially even less in context of EP elections (Baboš & Világi, Citation2018). Specifically for the 2019 EP elections context, an additional argument is that the relevance of the Eurovision debate might have increased compared to 2014 due to voters' previous experience with the Spitzenkandidaten process and related TV debates – in particular seeing the successful lead candidate Jean-Claude Juncker indeed becoming the Commission president.

Yet, there are also reasons that speak against strong Eurovision debate effects. First, the debate format includes various contenders – unlike the common head-to-head format focusing on two main competitors – which increases not only citizens' required information about a larger number of candidates, but also complexity, which may weaken voting effects due to more demanding performance evaluations (e.g., Goldberg & Ischen, Citation2020). Second, the low levels of citizens' awareness and recognition of European parties' lead candidates do not indicate strong interest in the more personalized EP elections contest and respective TV debates (e.g., Hobolt, Citation2014; Schmitt et al., Citation2015). The lack of knowledge about the candidates and their (national) party representations may further prevent citizens from drawing the right conclusions, that is, linking a positive debate performance of a candidate with the respective party voting on the national electoral ballot. Following the opposing arguments of favourable (structural) conditions of strong debate effects and the findings about the weak influence of the Spitzenkandidaten process more generally, this study's overall goal is to answer whether exposure to the Eurovision TV debate influences individual voting behaviour in the 2019 EP elections.

To answer this question, I consider and examine different common debate effects. While most studies focus on debate effects on candidate or party choice, debates are said to also influence the preceding step, namely the decision to participate in an election or not. Due to the provision of information about issues and candidates, and the related attempt to engage debate viewers in the campaign, debates influence the motivations to turn out (Best & Hubbard, Citation1999; Maier et al., Citation2018). Specifically for EP elections, Schmitt et al. (Citation2015) argue that the Spitzenkandidaten process may increase voter mobilization via the aforementioned personalization. Given the comparatively low (perceived) relevance of and participation in EP elections, the authors argue that the role of lead candidates is especially important for the mobilization of voters by providing citizens the possibility to identify with the candidates and their political objectives, as presented in, e.g., TV debates (see also Maier et al., Citation2018). In addition to this direct watching effect, there may be also an indirect effect via media coverage (Pattie & Johnston, Citation2011). Post-debate coverage usually focusses on the ‘horse race’ aspects of the electoral competition including post-debate polls, presentation of a debate winner and discussion of the likely impact of the debate on the election outcome, which may motivate citizens to vote (McKinney & Carlin, Citation2004). In the first hypothesis, I examine a direct and/or indirect effect of debate exposure on the turnout decision:

H1: TV debate exposure increases the likelihood to vote in the EP elections.

The second relevant voting aspect is party choice. Having a preference for one of the debate contenders is assumed to result in the respective party choice. The mechanism on party choice runs first via information and learning effects. The debate not only makes the candidates more familiar to the audience but also highlights the differences between the candidates and their political ideas, which helps the audience to form a preference on who should be the next Commission President (Hix, Citation2008; Maier et al., Citation2018). Important is then not the sheer exposure to the debate, but the performance of the candidates and related evaluation of the viewers (Maier et al., Citation2014; Pattie & Johnston, Citation2011). The latter is the crucial aspect as better (self-)perceived performances of candidates should result in voting for this candidate:

H2: Debate watchers are more likely to vote for a party/candidate who they evaluate to have performed well in the debate.

Related, and as a result of these performance evaluations, viewers may also identify a winner or loser of the debate. Various studies have shown such winner effects on party/candidate voting (Blais & Boyer, Citation1996; Goldberg & Ischen, Citation2020; Maier et al., Citation2014; Pattie & Johnston, Citation2011). For Germany, Maier et al. (Citation2014) report an increasing voting probability for the winner of a debate by up to 30–40 percentage points. In Canada, the effect is found to be smaller, but still significant with up to 10 percentage points (Blais & Boyer, Citation1996). A third hypothesis thus expects citizens to be more likely to vote for the self-perceived debate winner.

H3: Debate watchers are more likely to vote for a party/candidate who they perceive as the winner of the debate.

Finally, debate effects are not necessarily universal, but may depend on the type of voters, e.g., related to political knowledge or information. Authors such as McKinney and Carlin (Citation2004) or Maier et al. (Citation2016) argue that debates have stronger influence on highly interested and more knowledgeable voters as only those can properly process the relevant political information. Holbrook (Citation1999) shows an indeed greater learning effect among politically engaged voters. Yet, other studies found opposing effects. For instance, Maier et al. (Citation2013) found stronger debate effects on participation among voters less interested in the campaign or politics more generally. The improvement of the objective knowledge and subjective competence by watching the debate is said to result in positive effects among less interested/competent voters, while little information gains among interested ones result in no or smaller effects. Following these opposing arguments and mixed evidence, I formulate a research question about the moderation effect of political sophistication.

RQ1: Does political sophistication moderate the relationship between debate exposure and voting behaviour, and if so how?

Research design

The 2019 Eurovision debate

Several national and pan-European TV debates took place in the run-up to the 2019 EP elections. The most important one was again the ‘Eurovision Debate’ on May, 15. In contrast to the 2014 EP elections, six – instead of five – European political parties appointed lead candidates. While some parties nominated one lead candidate (Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (ACRE), European People's Party (EPP) & Party of European Socialists (PES)), others nominated two (European Green Party (EGP) & European Left (EL)) or a whole team of seven politicians (Alliance of Liberals and Demcrats for Europe (ALDE)). The following six lead candidates participated in the debate: Nico Cué (EL, Belgium), Ska Keller (EGP, Germany), Frans Timmermanns (PES, Netherlands), Margrethe Vestager (ALDE, Denmark), Manfred Weber (EPP, Germany) and Jan Zahradil (ACRE, Czech Republic). None of them was an ‘incumbent’ candidate accountable for the past 5 years as Commission President.Footnote2 Unlike in 2014, the set of participating parties included not only (mainstream) pro-European positions but also more critical positions (ACRE), although the far-right and Eurosceptic party Identity and Democracy (ID) was again absent.

In contrast to calls for a more prominent coverage of the Eurovision debate in the main national TV channels (Maier et al., Citation2018), in most countries the debate was broadcasted on only smaller, more specialized channels, if at all (EBU, Citation2020; Presidency of the EC, Citation2019). provides an overview of (TV) coverage in the five countries under study, based on official information from the European Broadcasting Union, which is responsible for the production of the Eurovision debate (EBU, Citation2020; Presidency of the EC, Citation2019). In two countries, the debate was live broadcasted in full, while in Denmark and Hungary it was only partly broadcasted and in the Netherlands not at all. The total time of coverage, live or as snippets in other TV programmes, and the number of hits, i.e., how often the debate was covered/discussed in TV (news) items, strongly differ accordingly in these countries. Out of the five countries, Germany covered the debate most widely (also compared to rest of the EU) and the Netherlands covered it the least. Importantly, though, there were other ways how to access the live debate, e.g., the EU Parliament provided both a live YouTube feed and live stream on Facebook, and the EBU also embedded a live feed on their Eurovision debate website.

Table 1. TV coverage of the debate.

The debate was actively followed via social media, e.g., the EBU reported over 240,000 impressions linked to the official #telleurope hashtag on Twitter (EBU, Citation2019). The hashtag trended in various countries, including Germany, Spain and Denmark. In 2014, the same hashtag was used only half as often (Dinter & Weissenbach, Citation2015). As a comparison to other pan-European events, the hashtag of the popular Eurovision Song Contest achieved around 550,000 twitter impressions.

Data and methods

The analysis is based on original flash survey data focussing on the Eurovision debate, embedded in a larger panel study (Goldberg et al., Citation2021). These data were collected across five EU member states (Denmark [DK], Germany [DE], Hungary [HU], Spain [ES] and the Netherlands [NL]) that represent smaller, bigger, newer and older EU member states, and are geographically spread across Europe. The countries further differ in the extent to which the debate was covered (live) on TV (see ) and by (not) representing lead candidates participating in the debate (Keller and Weber being German, Timmermans being Dutch and Vestager being Danish), which may influence citizens' evaluation of and voting for them. The panel data collection aimed at the EP elections in May 2019 with two waves before the elections (started in December 2018; in NL it started in September 2017 with three additional waves) and one postelection wave. All surveys were conducted via Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing by Kantar, including sampling quotas to ensure representativeness on age, gender, region and education (checked against information from the National Statistics Bureaus or governmental sources). All Eurovision-specific variables were asked in the flash survey conducted right after the day of the debate (16–19 May 2019), with other used variables asked in the pre-election (5–24 April 2019) and post-election waves (27 May–10 June 2019).Footnote3 Only respondents who participated in the previous panel study were invited to participate in the flash survey. We restricted the field period of the flash survey to four days to not blur the effects with other campaign events/activities, with response rates ranging between 31 (HU) and 92 per cent (NL).Footnote4 The final numbers of respondents in the flash survey per country are: 1378,

1378,

1387,

823 and

1496.

The setup of the data collection follows the request by Maier et al. (Citation2018) to use representative surveys – instead of experiments among a specific subset of the population such as students – to examine the effects of TV debates at the European level for the general public. The downside of using a survey is the reliance on self-reported debate exposure and the common difficulty to establish causality with complete certainty (Schmitt et al., Citation2015). Yet, the used flash survey design asking debate specific questions right after the debate, instead of in the post-election survey, helps to reduce causal inference problems. Furthermore, and as explained in the following, the statistical models include various relevant variables (measured before the debate took place) to account for possible confounders and to separate the effect of debate watching as much as possible.

Operationalization

The two dependent variables are electoral participation and party choice. Electoral participation was asked using the common face-saving approach with three ‘No’ options and one ‘Yes’ option. I combined the three ‘No’ categories into abstention=0 to create a binary turnout variable with participation=1. The exact wording, recoding and wave of measurement of this and all other variables can be found in Table A1 in the online appendix. Party choice is the recoded national party voting at the European level. The survey question asked for the original national parties as written on the electoral ballot. For pooling the voting behaviour across countries, and as the lead candidates officially represent their European party belonging, I recoded all national parties into their European political groups. I focus on the six political groups represented in the Eurovision debate (EPP, S&D, Renew, Greens-EFA, ECR and GUE-NGL). All other party voting, including for the not represented ID group, for a non-affiliated party (NI) or smaller parties, was recoded into ‘other’. Party choice was both measured in the flash (as intended party choice) and post-election wave. In the former, people who were not sure yet and answered ‘don't know’ were recoded into the ‘other’ category.

For hypothesis H1, the main independent variables are first whether respondents watched the Eurovision debate. This was asked using four answer categories. I merged the three ‘Yes’ options (completely, most of it or a little bit) to create a binary debate watching variable. As robustness check, I also used the original coding. The second variable for H1 is a binary variable asking whether respondents were exposed to media coverage about the debate (in any media) after it took place. For hypothesis H2, all respondents who watched the debate (if only a little bit) were asked to evaluate the performance of each candidate during the debate on a seven-point scale (standardized to ease interpretation). In addition, they were asked to identify a winner of the debate out of the six contenders or the option of ‘no winner’, which is the relevant variable for hypothesis H3. Finally, to examine the potential moderation effect of political sophistication, I use two measures: political interest in the EU measured on a seven-point answer scale and a scale of (EU) political knowledge based on eight knowledge questions (1 out of 5 answer options correct plus ‘don't know’ option) asked over the course of the different panel waves. As these two measures are moderately correlated (r = 0.41), I test them separately.

Analyses

For estimating the binary turnout decision in the post-election wave, I run a probit regression model. To control for the possibility that people first decide to vote and subsequently watch the debate, I take into account respondent's intended participation in the election measured in the pre-election wave (on a seven-point certainty scale). Furthermore, in line with Schmitt et al. (Citation2015)'s warning to not overestimate debate watching effects, that is, that respondents who were exposed to the debate and those who were not may differ on various other factors linked to their likelihood to turn out (see also Baboš & Világi, Citation2018), I control for many common turnout determinants: general political participation, political interest in the EU, political efficacy (external), economic evaluations, satisfaction with the national government, trust in the EP, civic duty to vote, general media exposure, left–right political orientation (single and squared) and sociodemographic variables measuring age (single and squared), sex and education (all standardized except of sex and education). The model further includes country-fixed effects.

To estimate effects on party choice, I rely on multinomial logistic regression models among debate watchers. These models are run twice, first to estimate short-term effects right after the debate by looking at intended party choice in the flash survey and second to estimate the effect on party choice reported in the post-election wave. To exclude a potential partisan bias, i.e., that partisan viewers evaluate their candidates in a positive way and subsequently vote for them, I control for intended party choice in the pre-election wave. I further control for various other potential determinants of EP party choice: multidimensional EU attitudes, satisfaction with the national government, anti-immigration attitudes, general media exposure and sociodemographics (all standardized except of sex and education). The models again include country-fixed effects. To ease the interpretation of the multinomial logistic models (as all effects are relative to the base party category), I present average marginal effects (AME) plots. For the examination of moderation effects (RQ1), I interact the respective (independent) variables of interest separately with each of the two measures of political sophistication. For an overview of all used variables see Table A1 in the online appendix. I tested for potential problems of multicollinearity in both turnout and party choice models. The resulting variance inflation factors (VIF) are all (clearly) under the potential worrisome value of 5.

Results

Before turning to the regression models, and display the distribution of debate exposure among survey respondents. A bit more than a quarter of the respondents were at least partly exposed to the TV debate, albeit only few watched the complete broadcasting.Footnote5 further shows marked country differences that largely match the different coverage as displayed in . Especially the non-broadcasting in Dutch television is consequential with more than 90% of Dutch respondents having seen nothing at all of the debate. Unlike reported for the 2014 edition by Schmitt et al. (Citation2015), the presence of country fellow candidates in the debate (for DE, DK and NL) did not result in higher viewership in the respective home countries.

Table 2. Exposure to (live) TV debate among respondents (in %).

Table 3. Exposure to post-debate media coverage among respondents (in %).

The exposure to any media coverage about the debate in the day(s) after the debate follows similar patterns, again with highest exposure numbers in Hungary and Spain and lowest numbers in the Netherlands. The similar patterns in and may suggest that the same people who watched the debate were also exposed to post-debate coverage. However, the association between both measures (using the recoded binary debate watching variable) of phi = 0.17 shows basically no relationship between the two types of exposure. This means that respondents either saw the debate or heard/read about it afterwards, but not necessarily both.

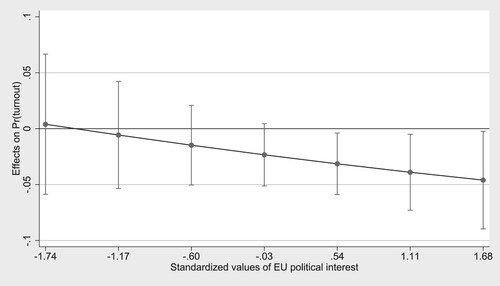

displays the results of the probit regression models to estimate turnout. Models 1 and 2 include only the (live) TV debate exposure plus basic (sociodemographic) and complete controls, Models 3 and 4 only the post-debate media exposure plus basic and complete controls, Model 5 both exposure variables and Model 6 as robustness check includes the original four category coding of TV debate watching (see Table A2 in the online appendix for the complete regression results). The more parsimonious models 1 and 3 display positive effects on turnout, but only significant for media coverage. When including the full set of controls in models 2 and 4, though, these positive effects disappear and turn into unexpected negative coefficients of debate exposure. While the respective coefficient is non-significant for the post-debate media coverage, it is significant for debate watching, in both its binary and original coding (albeit not for all three categories). Yet, the substantial size of the debate watching effect, in terms of first differences in predicted probabilities to turn out, is rather small with around −2.7 percentage points for respondents being exposed to the TV debate in Model 5.

Table 4. Regression models of Eurovision debate exposure on electoral participation.

To analyse this unexpected negative debate watching effect in more detail, the moderation with political sophistication is of interest. The interaction between political knowledge and debate watching does not result in any interesting pattern, yet the interaction with political interest does. shows that the negative debate watching effect only holds for respondents with higher levels of political interest (higher than the mean value), while we observe no debate effect for lower values. In sum, while hypothesis 1 (direct debate effect) is not supported, a moderation effect with political sophistication (RQ1) finds some preliminary support.

Turning to party choice among debate watchers, the cross-country distributions of the explanatory variables are already interesting (see Figure A1 and Table A5 in the online appendix).Footnote6 While respondents in Spain evaluated the debate performance of all six candidates in a similar way, the most noticeable patterns stem from the Netherlands and especially Denmark, where the two ‘home country’ candidates Timmermans and Vestager were evaluated higher than the others. Such a home country effect is not present for Keller and Weber in Germany. The same pattern is observable for the identification of a debate winner. Again, the Danish and Dutch respondents picked ‘their’ candidates, while no clear debate winner was identified in the other three countries. Around 40% of debate watchers could not identify any clear winner.

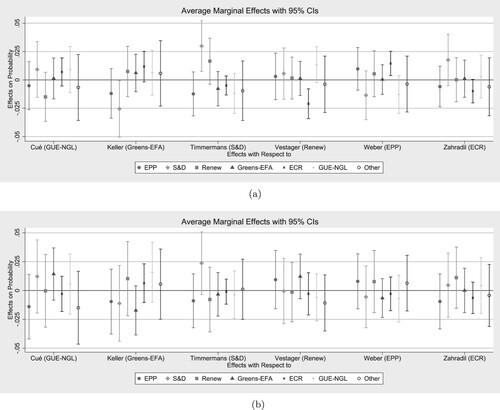

To what extent these performance evaluations translate into respondents' party voting is answered in the average marginal effect plots in and . As one example of the underlying multinomial regression models, Table A6 in the online appendix shows the performance evaluation model in the flash wave (all other model outputs available upon request). Theoretically, should show one positive evaluation effect per candidate, namely on the respective party voting. However, we can see almost none of these effects. For the short-term effects in graph (a), the only two significant positive effects stem from a more positive evaluation of Timmermans and related S&D voting intention, as expected, and positive evaluations of Weber resulting in a higher likelihood to (intend to) vote for the ECR, unlike as expected. Yet, both these effects vanish when estimating reported vote choice in the post-election wave in graph (b). Hypothesis 2 is thus not supported.Footnote7

Figure 2. Effects of performance evaluations on party choice: (a) intended party choice in flash wave and (b) reported party choice in post-election wave.

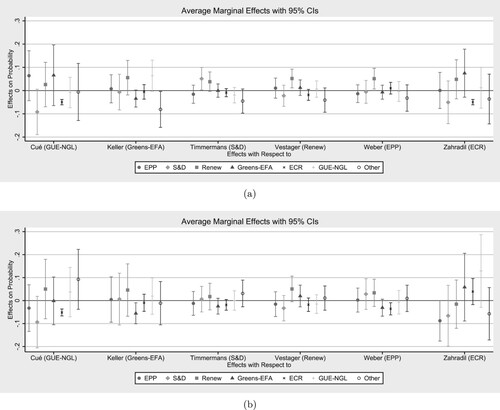

Figure 3. Effects of perceived debate winner on party choice: (a) intended party choice in flash wave and (b) reported party choice in post-election wave.

Turning to the perceived winner effect in shows some more significant relationships, particularly for intended party choice in graph (a). We find the expected positive effects for Timmermans and S&D voting as well as for Vestager and Renew voting. The equally positive effect for Weber and Renew voting runs counter expectations. However, in graph (b) we again see that none of these effects remains significant for reported party choice, albeit in the case of Vestager the effect is still marginally significant (p = 0.074). Overall, hypothesis 3 is not supported either.

In a final step, the two variables, performance evaluations and perceived debate winner, were interacted with political sophistication.Footnote8 In the absence of overall clearly different/stronger patterns, the interaction effects point to stronger debate effects among more sophisticated respondents. First, the (marginally) significant effect of positive evaluations for Timmermans and S&D voting out of the main model is highly significant (p<0.01) among knowledgeable respondents (+1SD), but not for less knowledgeable ones (−1SD) (see Figure A3 in the online appendix). Second, the interaction model with perceived debate winners displays a clearer and more meaningful pattern among respondents with higher (+1SD) compared to lower (−1SD) political interest. For the former, the marginal effect for Vestager and Renew voting out of the main model turns significant (p = 0.034) and the effect for Zahradil and ECR voting turns marginally significant (p = 0.060) (see Figure A4 in the online appendix). Hence, in combination with the previous moderation patterns for turnout, there seem to be moderation effects with political sophistication (RQ1). However, given the multitude of possible interaction effects, one should not over-interpret the importance of the found moderations.

Discussion

The main research goal of this article was to examine whether exposure to the Eurovision TV debate influenced citizens' decision to turn out and their party choice during the 2019 EP elections. The focus on voting behaviour complements the scarce extant research from the previous edition – when the Spitzenkandidaten process was introduced – which analysed information gains or attitudes towards the lead candidates. The article relied on original flash and panel survey data collected across five EU member states. These data display significant differences across countries in respondents' exposure to the debate and candidate performance evaluations. Differences in exposure levels largely match country-specific patterns in the actual broadcasting and coverage of the debate on television. As in 2014, in most countries the Eurovision debate was only broadcasted in secondary or specialized news channels, if at all, instead of in the main channels. The media thus missed another opportunity to put the EP elections in the spotlight (Maier et al., Citation2018).

The article's main finding is an overall absence of debate effects on voting behaviour. Importantly, this finding cannot be attributed to the scant coverage of the TV debate in most countries, as the respondents' debate exposure and subsequent performance evaluations of the candidates vary substantially at the individual level. Rather, the absence of effects of the Eurovision debate on voting behaviour fits with related research findings about the limited influence of the Spitzenkandidaten process more generally. Similar to studies in the 2014 EP elections context (Hobolt, Citation2014; Schmitt et al., Citation2015; Treib, Citation2014), recent studies found the same limited effects (on voting behaviour) in the 2019 elections (Gattermann & de Vreese, Citation2020; Gattermann & Marquart, Citation2020). Despite the already more familiar process due to its second occurrence in 2019, EU citizens seem to still be ill at ease with this attempt to personalize EU politics.

One of the few significant, albeit weak effects is the surprisingly negative influence of debate watching on turnout. This effect holds especially among respondents with higher interest in EU politics. One potential explanation was identified by Dinter and Weissenbach (Citation2015). By conducting qualitative group discussions after the 2014 debate, the authors identified that the ‘show’ character of the debate and the strict speaking order and times contributed to people's perceptions of a rather unreal and distant Europe. The common simultaneous translations into the respective languages may have further contributed to this impression. Following this argument and the fact that various participants in their study were disappointed by the quality of political information during the debate, it is not surprising any more that the desired positive debate effect transformed into the opposite among already highly interested citizens (ibid.). A related explanation may be a ceiling effect, as citizens who watched the TV debate already have a (very) high likelihood of voting, so that their electoral participation, if being influenced in any direction, can only go down. Evidence pointing to such ceiling effects for other campaign activities during the EP 2019 elections were found by Marquart et al. (Citation2020).

In terms of affecting party choice, more positive debate performance evaluations resulted in partly higher voting intentions right after the debate, at least for the more well-known candidates Timmermans and Vestager. However, until election day, all these effects had vanished (cf. Lindemann & Stoetzer, Citation2021). A specific reason for the weak effects on party choice may be the format of the debate including six contenders, among which most represent (mainstream) pro-Europe positions and only one contender a clearly critical position towards Europe. The lack of a polarized discussion, and also the comparatively higher complexity of the debate including six candidates and their respective positions on three main topics, makes it harder for debate watchers to properly evaluate all candidates, identify debate winners and subsequently vote for one's favourite (cf. Goldberg & Ischen, Citation2020).

Notwithstanding the presumably favourable conditions of TV debate effects in the European context, that is, less well-known candidates, many undecided voters and weak party allegiances, the article could not confirm the commonly found effects on voting behaviour from national TV debates. Hence, while EP elections are characterized as less second-order today (e.g., van Elsas et al., Citation2019), the related election campaign dynamics still are. Although the article's findings are limited as to stemming from only five of the back then still 28 EU countries, the results match well other studies' conclusions about the overall limited influence of the Spitzenkandidaten process. One potential underlying problem may be citizen's still too little knowledge about the candidates (Gattermann & de Vreese, Citation2020) and relating them to respective national party choice – despite TV debates' potential to increase such knowledge (Richter & Stier, Citation2022). As a future outlook, the fact that ultimately none of the lead candidates became Commission President most likely did not strengthen the process among citizens, rather the opposite. While this broken promise did not influence the study at hand, as at the time of surveying the respondents did not know about it, it remains to be seen how the Spitzenkandidaten process will continue in the future, if at all, and which role TV debates may play in it.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (952.3 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Linda Bos, Katjana Gattermann, Carolina Plescia and Claes de Vreese for their helpful feedback for earlier versions of the article. I further thank the two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful and constructive comments that helped to improve the manuscript.

Replication material

Supporting data and materials for this article can be accessed on the Taylor & Francis website, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2095417. The original panel data and related documentation can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13795.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andreas C. Goldberg

Andreas C. Goldberg is Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology and Political Science, NTNU – Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

Notes

1 While the EP interprets the Lisbon Treaty (TEU) in this way, the treaty does not mention a binding link between the EP elections outcome and the nomination of a candidate by the European Council, but only states that ‘Taking into account the elections to the European Parliament and after having held the appropriate consultations, the European Council, acting by a qualified majority, shall propose to the European Parliament a candidate for President of the Commission.’ (Article 17(7) TEU) (cf. Hobolt, Citation2014).

2 Yet, Timmermanns was Vice President and Vestager was Commissioner.

3 Some additional control variables were assessed in previous waves (see details in the online appendix).

4 These 4 days are sufficient to cover the bulk of the post-debate media coverage as most of this is published at the day right after the debate, that is, around 50% of all post-debate TV hits were registered on May 16 alone (Presidency of the EC, Citation2019).

5 Unsurprisingly, debate watchers are significantly more interested in EU politics, have stronger feelings of civic duty to vote and indicate a stronger intention to turn out in the elections (based on significant t-tests). Hence, the inclusion of those variables in the regression models is crucial to control for differences in group composition of debate watchers. Debate watchers also show higher levels of candidate recognition before the debate (Table A3 in the online appendix).

6 See Table A4 in the online appendix for a comparison of candidate evaluations across party support.

7 Excluding all respondents with no candidate recognition before the debate (based on Table A3), who have the least probability to correctly link the candidates with the respective party choice, does not change the results as displayed in Figure A2 in the online appendix.

8 Due to the large amount of different (sub)models, I did so only for the model on reported party choice in the post-election wave.

References

- Baboš, P., & Világi, A. (2018). Just a show? Effects of televised debates on political attitudes and preferences in Slovakia. East European Politics and Societies: and Cultures, 32(4), 720–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325418762050

- Benoit, W. L., & Hansen, G. J. (2004). Presidential debate watching, issue knowledge, character evaluation, and vote choice. Human Communication Research, 30(1), 121–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.2004.30.issue-1

- Best, S. J., & Hubbard, C. (1999). Maximizing ‘minimal effects’: The impact of early primary season debates on voter preferences. American Politics Quarterly, 27(4), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X99027004004

- Blais, A., & Boyer, M. M. (1996). Assessing the impact of televised debates: The case of the 1988 canadian election. British Journal of Political Science, 26(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400000405

- Carlin, D. P. (1992). Presidential debates as focal points for campaign arguments. Political Communication, 9(4), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1992.9962949

- Chaffee, S. H. (1978). Presidential debates–Are they helpful to voters? Communication Monographs, 45(4), 330–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757809375978

- Dinter, J., & Weissenbach, K. (2015). Alles Neu! Das Experiment TV-Debatte im Europawahlkampf 2014. In M. Kaeding and N. Switek (Eds.), Die Europawahl 2014 (pp. 233–245). Springer VS.

- EBU (2019). Eurovision debate: Web and social media performance. European Broadcasting Union.

- EBU (2020). Eurovision debate – EU elections 2019. European Broadcasting Union.

- Gattermann, K. (2020). Media personalization during European elections: The 2019 election campaigns in context. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13084

- Gattermann, K., & de Vreese, C. (2020). Awareness of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2019 European elections: The effects of news exposure in domestic campaign contexts. Research & Politics, 7(2), 2053168020915332. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168020915332

- Gattermann, K., & Marquart, F. (2020). Do Spitzenkandidaten really make a difference? An experiment on the effectiveness of personalized European Parliament election campaigns. European Union Politics, 21(4), 612–633. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520938148

- Goldberg, A. C., & Ischen, C. (2020). Be there or be square – The impact of participation and performance in the 2017 Dutch TV debates and its coverage on voting behaviour. Electoral Studies, 66, 102171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102171

- Goldberg, A. C., van Elsas, E. J., Marquart, F., Brosius, A., de Boer, D. C., & de Vreese, C. H. (2021). Europinions: Public opinion survey. Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13795

- Hix, S. (2008). What's wrong with the European Union and how to fix it. Polity Press.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2014). A vote for the president? The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(10), 1528–1540. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.941148

- Holbrook, T. M. (1999). Political learning from presidential debates. Political Behavior, 21(1), 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023348513570

- Lindemann, K., & Stoetzer, L. F. (2021). The effect of televised candidate debates on the support for political parties. Electoral Studies, 69, 102243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102243

- Maier, J., Faas, T., & Maier, M. (2013). Mobilisierung durch Fernsehdebatten: zum Einfluss des TV-Duells 2009 auf die politische Involvierung und die Partizipationsbereitschaft. In B. Weßels, H. Schoen, & O. W. Gabriel (Eds.), Wahlen und Wähler (pp. 79–96). Springer VS.

- Maier, J., Faas, T., & Maier, M. (2014). Aufgeholt, aber nicht aufgeschlossen: Wahrnehmungen und Wirkungen von TV Duellen am Beispiel von Angela Merkel und Peer Steinbrück 2013. ZParl Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen, 45(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.5771/0340-1758-2014-1

- Maier, J., Faas, T., Rittberger, B., Fortin-Rittberger, J., Josifides, K. A., Banducci, S., Bellucci, P., Blomgren, M., Brikse, I., Chwedczuk-Szulc, K., M. C. Lobo, Czesnik, M., Deligiaouri, A., Deželan, T., deNooy, W., A. Di Virgilio, Fesnic, F., Fink-Hafner, D., Grbeša, M., …Zavecz, G. (2018). This time it's different? Effects of the Eurovision debate on young citizens and its consequence for EU democracy – Evidence from a quasi-experiment in 24 countries. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(4), 606–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1268643

- Maier, J., Rittberger, B., & Faas, T. (2016). Debating Europe: Effects of the “Eurovision debate” on EU attitudes of young German voters and the moderating role played by political involvement. Politics and Governance, 4(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v4i1.456

- Marquart, F., Goldberg, A. C., & de Vreese, C. H. (2020). ‘This time I'm (not) voting’: A comprehensive overview of campaign factors influencing turnout at European Parliament elections. European Union Politics, 21(4), 680–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520943670

- Maurer, M., & Reinemann, C (2013). Schröder gegen Stoiber: Nutzung, Wahrnehmung und Wirkung der TV-Duelle. Springer-Verlag.

- McKinney, M. S., & Carlin, D. P. (2004). Political campaign debates. In L. L. Kaid (Ed.), Handbook of political communication research (pp. 203–234). Taylor & Francis.

- Nulty, P., Theocharis, Y., Popa, S. A., Parnet, O., & Benoit, K. (2016). Social media and political communication in the 2014 elections to the European Parliament. Electoral Studies, 44, 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.014

- Palacios, I., & Arnold, C. (2021). Do Spitzenkandidaten debates matter? Effects on voters' cognitions and evaluations of candidates and issues. Politics, 41(4), 486–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957211015231

- Pattie, C., & Johnston, R. (2011). A tale of sound and fury, signifying something? The impact of the leaders' debates in the 2010 UK general election. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 21(2), 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2011.562609

- Popa, S. A., Fazekas, Z., Braun, D., & Leidecker-Sandmann, M. M. (2020). Informing the public: how party communication builds opportunity structures. Political Communication, 37(3), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1666942

- Popa, S. A., Rohrschneider, R., & Schmitt, H. (2016). Polarizing without legitimizing: the effect of lead candidates' campaigns on perceptions of the EU democracy. Electoral Studies, 44, 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.07.001

- Presidency of the EC (2019). Debate 2019 – European parliament report (Audiovisual Unit report).

- Reif, K., & Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second–order national elections – A conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results. European Journal of Political Research, 8(1), 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejpr.1980.8.issue-1

- Richter, S., & Stier, S. (2022). Learning about the unknown Spitzenkandidaten: The role of media exposure during the 2019 European Parliament elections. European Union Politics, 23(2), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165211051171

- Schmitt, H., Hobolt, S., & Popa, S. A. (2015). Does personalization increase turnout? Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European parliament elections. European Union Politics, 16(3), 347–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515584626

- Sigelman, L., & Sigelman, C. K. (1984). Judgments of the Carter-Reagan debate: The eyes of the beholders. Public Opinion Quarterly, 48(3), 624. https://doi.org/10.1086/268863

- Treib, O. (2014). The voter says no, but nobody listens: Causes and consequences of the Eurosceptic vote in the 2014 European elections. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(10), 1541–1554. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.941534

- van Aelst, P., Sheafer, T., & Stanyer, J. (2012). The personalization of mediated political communication: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427802

- van Elsas, E. J., Goldberg, A. C., & de Vreese, C. H. (2019). EU issue voting and the 2014 European parliament elections: A dynamic perspective. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 29(3), 341–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2018.1531009

- Yawn, M., Ellsworth, K., Beatty, B., & Kahn, K. F. (1998). How a presidential primary debate changed attitudes of audience members. Political Behavior, 20(2), 155–181. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024832830083