ABSTRACT

Scholars have paid increasing attention to how questions of multi-level governance have become politicized in the domestic political arena. Issues surrounding democratic government itself have received surprisingly little attention in this debate. In this article, we ask how political parties politicize the principles of liberal democracy within advanced democracies. We expect that challenger parties are most likely to question existing principles. The targets of their criticism, however, should vary according to their ideological origins. Conducting automated quantitative text analysis of Swiss, German and Austrian party press releases between 2006 and 2018 using a multidimensional dictionary of liberal democracy, we confirm that left-libertarian and populist radical right parties are the main challengers of the democratic status quo. The foundation of criticism, however, differs fundamentally. While left-libertarians focus on principles that strengthen individual autonomy in politics, populist radical right parties demand more forms of participation and fewer constraints by liberal elements of democracy.

Introduction

Democratic competition in Europe has fundamentally changed in the last 30 years. While the post-war years were dominated by questions around state intervention in the economy and redistributive policies, new dimensions of political conflict now dominate elections in Europe. Questions of multi-level governance constitute a core dimension in this changing political space (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009, Citation2018). Most prominently discussed in the context of European integration, scholars have demonstrated that decisions that were mostly elite driven, have now entered the arena of mass politics (Hobolt & de Vries, Citation2016). The central question surrounding these issues is how institutions of democratic governance can be extended to address transnational political, social and economic questions. Political challengers such as eurosceptic and radical right parties have been able to successfully mobilize against the expansion of the scope of multi-level governance (de Vries & Hobolt, Citation2012; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009).

While questions of European integration and transnational governance constitute the prime focus of this post-functionalist perspective on multi-level governance, a core question is surprisingly absent in this line of research: how democratic governance itself can become the object of political competition. This is even more puzzling, as we have seen an increase in public debate and scholarly attention concerning the potential erosion of liberal democracy (e.g., Diamond et al., Citation2015; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Citation2018). While it seems evident that the rise of populism has placed into question some democratic principles, we know comparatively little about how actors, and particularly political parties, within advanced democracies challenge democratic norms and procedures.

The aim of this paper is to contribute to a better understanding of the nature of the politicization of democratic governance by different actors. We argue that by focusing on the politicization of democracy per se, we might overlook the strategic dynamics of political actors competing over the nature of their political system. Democratic governance encompasses several dimensions, and challenging the status quo does not necessarily imply that political parties display anti-system rhetoric that questions democracy as such (Sartori, Citation1967). Rather, liberal democracy includes liberal and participatory principles, and depending on which are the main targets of the parties’ rhetoric, debates surrounding democratic governance have different implications for the future state of democracy. Hence, if we understand the different ways to politicize democratic principles instead of focusing on the threat that single parties might pose for democracy, we can also better assess more hidden (rhetorical) attacks on democracy.

In this paper, we propose a theoretical framework to explain why certain political parties politicize different aspects of democratic governance. We argue that challenger parties have strong incentives to campaign on issues that place into question the status quo of party consensus (de Vries & Hobolt, Citation2020). Challenging the rules of the game allows new parties to generate support outside the dominant dimensions of political conflict. In this regard challenges to existing democratic principles are not new to European politics. In his influential work on green and left-libertarian parties, Kitschelt (Citation1989) argues that parties can create appeals in the electoral market that go beyond programmatic offers and provide people with a new idea of how democratic politics can work. We suggest that the recent success of populist radical right parties can be understood from a similar perspective.

Our argument is twofold. As the main challenger parties in Western Europe, green/left-libertarian and populist radical right parties have an incentive to politicize the principles of liberal democracies. However, the exact nature of this politicization should differ between these two party families. The left-libertarian criticism of political processes is grounded in postmaterialism and thus, in the belief that individual autonomy needs to be at the core of economic and political processes (Inglehart, Citation1977; Kitschelt, Citation1989). Populist radical right parties, in contrast, derive their demand for political renewal from their populist and authoritarian ideology. While we argue that both logics lead to the demand for a strengthening of participatory principles of democracy, we expect only populist radical right parties to challenge the status quo of the liberal elements of democracy. Liberal principles, such as separation of powers, the rule of law or an independent judiciary, are opposed to the absolute power of the people. If left-libertarians mention liberal principles in current-day politics this is in reaction to and in defense of these very principles. Hence, in order to understand the different ways in which political parties challenge the status quo of democratic processes, we need to distinguish different elements of liberal democratic rule.

We investigate the politicization of democratic principles by conducting automated content analysis of political communication in three advanced Western European democracies (Austria, Germany, Switzerland). Employing a multi-dimensional concept of liberal democracy, we measure the salience of democratic principles in all press releases published by the major political parties in these countries between January 2006 and March 2018. For this, we developed a nested dictionary that considers participatory and liberal principles of democracy. In addition, we analyze differences in parties’ tone (general or specific, positive or negative) when mentioning a democratic principle, making use of the keyness statistics of surrounding words.

We find that when looking at the more general patterns in Switzerland, Germany and Austria, left-libertarians and populist radical right parties politicize democratic principles more than the other party families. Although some other individual parties, such as the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) in Germany, The New Austria and Liberal Forum NEOS (which is also a new challenger party) or the Social Democrats (SPS) in Switzerland also politicize some aspects of democracy more than others, we do not find such cross-sectional patterns for mainstream parties, hence confirming that from a strategic perspective, challenger parties have stronger incentives to talk about democratic principles. The Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) and the Alternative for Germany (AfD) clearly dominate the debate about participation and they refer to direct democratic institutions as a way to improve democracy in all three countries. The Green parties, the main left-libertarian parties in our three countries, do so far less frequently. Rather, they emphasize the importance of the liberal dimension of democracy in particular when it comes to one principle that they mention more than all other parties: individual liberties. Finally, we find that populist radical right parties in the German-speaking countries are critical towards the status quo of another liberal principle – freedom of the press – facing similarly strong opposition from the Greens (and social democrats in Switzerland and Germany) defending it.

Our findings make an important contribution to the literature on political transformations and challenges to democracy as they provide a first systematic analysis of how the most important political actors in advanced democracies – political parties – question the status quo of liberal democracy. From a strategic perspective, all challenger parties have incentives to do so. However, left-libertarian parties with their individual-centered ideologies pose little threat to the idea of liberal democracy. On the contrary, we find left-libertarian parties to take the opposite site of populist radical right parties when politicizing liberal principles of democracy, in particular with their strong emphasis on individual liberties. It follows that challenger parties of different ideological origins are usually the main actors in the politicization of democracy on both ends, and not challenger parties on one side and mainstream parties on the other side. Thus, we confirm the expectations of previous scholars that populist radical right parties question liberal principles of democracy (but may enhance participatory principles, Mudde and Kaltwasser (Citation2017)), but also show that without taking into account strategic and ideological considerations of the other parties, we cannot understand who stands up against them.

These findings also show that debates surrounding the politicization of multi-level governance and democratic governance itself are not as far apart as initially suspected. Populist radical right parties pose not only a threat to the European Union (EU) as opponents to multi-level governance, but also by questioning some elementary parts of its member states’ democratic governance. We can already observe this in Hungary and Poland, where populist radical right parties have consolidated their power and attacked the EU and democratic institutions alike (Kelemen, Citation2020).

Strategic and ideological perspectives on democracy

The literature on new party success has generally focused on two ways new parties can challenge the dominance of established actors in multi-party systems: (1) positional differentiation and (2) challenging the existing political structures and processes. Downs (Citation1957) already points to the potential that new parties can successfully enter political competition by providing a distinct position in the electoral marketplace. When and how new parties can be successful with what Kitschelt (Citation1994) labels ‘product differentiation’ has indeed become a prime object of political science investigation.

A second way for political parties to challenge the dominance of established actors does not focus on policies but on changing politics or more precisely the mechanisms of a political system to assign political power. An extreme form of this is anti-system parties that promote a complete overhaul of the political system such as fascist or communist parties in the interwar period. However, this type of opposition to existing political processes does not need to be as extreme as in the case of anti-system parties. Instead of attacking democracy as such, challenger parties can also criticize the workings of the democratic process. Previous literature on challenger parties, and particularly the recent surge of studies on populism, has focused on the use of anti-establishment rhetoric in which challenger parties portray the established parties as self-serving and the main beneficiaries of the political institutions in place (de Vries & Hobolt, Citation2020, p. 147). Most prominently, de Vries and Hobolt (Citation2020) argue that in order for challenger parties to be successful, delivering an anti-establishment message is necessary so that dominant parties cannot simply appropriate the challenger party’s main issues (e.g., immigration or the environment). While some attention has been dedicated to the question of which elites are criticized by anti-establishment parties, there is much less focus on the question of what aspects of the way of doing politics are politicized by challenger parties and how their critique is related to the concept of liberal democracy.

Based on this second logic of party competition, we argue that in order to appeal to voters, challenger parties have strategic incentives to politicize principles of liberal democracy. Importantly then, this means that not only anti-system parties challenge democratic principles, but other new parties have also incentives to mobilize based on these ideas. In this paper, we explicitly focus on left-libertarian and populist radical right parties that have formed the two largest groups of challenger parties in Western Europe (de Vries & Hobolt, Citation2020). However, we do not follow the literal definition of challenger parties by de Vries and Hobolt (Citation2020), which only includes parties that have never formed part of national governments, but adjust it to the concept of party families. We consider all members of party families as challenger parties that do not belong to the traditional party families of post-war Europe, even when some of them already participated in government coalitions. We do so, because we argue that the democratic discourse cannot be looked at detached from the parties’ overall platform. Left-libertarian and populist radical right parties have provided ideological innovation in a set of topics and created a second dimension that structures party competition next to the traditional left-right dimension (de Vries & Hobolt, Citation2020; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018). We expect them to politicize democratic principles in line with the other topics of this new cultural divide. Hence, it is unlikely that the politicization of democratic principle disappears once the challenger party enters government for the first time, but rather it forms part of its electoral appeal also afterwards; particularly as long as mainstream parties are still the dominant forces in the national executives.

The challenger parties’ ideology is particularly important to explain how and which democratic principles populist radical parties and left-libertarian parties politicize. Politicizing democratic principles is only sustainable as long as it is congruent with their main ideology: postmaterialism and authoritarian populism (Inglehart, Citation1977; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019), respectively. As a result, while we expect that both party families have stronger incentives to politicize democracy due to their challenger status, we do not expect them to politicize democracy the same way.

At first sight, their criticism of political procedures still looks remarkably similar. Left-libertarian parties blame representative democracy to circumvent self-autonomy by giving too much power to political parties and interest groups (Kitschelt, Citation1989, p. 10). Instead, they want democratic procedures that allow for more citizen involvement. Similarly, populist radical right parties criticize that political processes are dominated by a liberal consensus of mainstream parties and do not represent the ‘will of the people’ (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2018).

The ideological foundations of their understanding of democratic principles and processes, however, are diametrically opposed to each other. Left-libertarian parties focus on individual autonomy – which is at the core of postmaterialism (Inglehart, Citation1977) – when criticizing the functioning of politics. Hence, their criticism is based on an ‘individual-centered notion of democracy’ and may ask for more and better forms of participation, but it does not target liberal principles that are part of most modern democracies and protect individual freedom and minorities from a too powerful majority (Pappas, Citation2019).

The criticism by populist radical right parties in contrast is linked to populism and authoritarianism, both contradicting the liberal foundation of democracy (Mudde, Citation2007). In a populist understanding of democracy, there is only one legitimate will of the people, as society consists of only two homogeneous groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’ (Mudde, Citation2004, p. 543). This anti-pluralist view is reinforced by their belief in a hierarchically ordered society where rules must be strictly followed (Mudde, Citation2007, p. 22ff.) Populist radical right parties see therefore no need for the institutions of liberal democracy that constrain the will of the people, on the contrary (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017). When populist radical right parties criticize the status quo of democracy, they may thus ask for more and better forms of participation, but are also very likely to attack liberal principles of democracy that contradict their ‘people-centred notion of democracy’. While we thus expect populist radical right and left-libertarian parties to politicize democratic principles more than the traditional party families, our expectations diverge with regard to which principles they focus on.

Principles of democracy

In advanced democracies in Western Europe, only the most extreme actors directly attack democracy as a form of government per se (Capoccia, Citation2002). If we want to empirically assess the differences between the populist radical right ‘people-centred’ and the left-libertarian ‘individual-centred’ notion of democracy, we need to use a more fine-grained concept that reflects the multidimensional nature of democracy.

Scholars have referred to liberal democracy as a core concept to discuss the tensions between these different notions of democracy (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017; Pappas, Citation2019; Riker, Citation1982). Despite the theoretical debate on the liberal idea within democracy, which contrasts the populist belief in the wisdom of majoritarian rule (Rousseauistic view) with the liberal fear that the majority can abuse its power to oppress other opinions (Madisonian view), most studies lack a clear set of democratic principles that constitute a liberal democracy. Dahl’s polyarchy (1971, p. 3) comes close to the liberal ideal that individuals must be protected in their fundamental rights by integrating principles such as freedom of expression or freedom of assembly. However, the concept lacks some crucial elements of the contemporary status quo in European liberal democracies such as the separation of powers or the rule of law that guarantee this protection (Coppedge et al., Citation2011; Pappas, Citation2019).

We apply a more fine-grained and multidimensional definition of liberal democracy that first, distinguishes more clearly between the principles that guarantee the rule by the people (participatory principles) and principles that constrain it (liberal principles) and second, assesses all elements of a liberal democracy. The concept of embedded democracy serves as a starting point for such a multidimensional concept, where the electoral regime builds the core of democratic rule and is embedded in a system that guarantees pluralism and the protection of individual freedom through a free marketplace of ideas, the rule of law and mutual institutional control (Merkel, Citation2004). In a further development of this conceptual base, one can derive eight principles of democracy from the participatory and liberal ideas of democracy (Bühlmann et al., Citation2012).

shows how these eight different principles of democracy fall into either the participatory or the liberal dimension. The participatory dimension of democracy is captured by three principles that emphasize the rule by the people. Competition refers to the sovereignty of the people and thus the importance of free elections and electoral competition as a way to translate citizens’ preferences to policies. This principle builds the minimalist condition of the large majority of definitions of democracy (Coppedge et al., Citation2011; Dahl, Citation1971; Merkel, Citation2004). Participation takes into account the possibility to expand electoral participation to institutions of direct democracy such as popular initiatives and referendums. Finally, representation embraces the ideal of politics reflecting the interest of the people. The principle transparency includes the absence of corruption and transparent political processes and party finances. This principle cannot be assigned unambiguously to the ideal of liberal or participatory democracy as it is a tool for monitoring the compliance of the state with other democratic (liberal or participatory) principles. The remaining principles mirror the liberal dimension of democracy. Constraints include the separation of powers and constitutional jurisdiction, rule of law the independence of the judiciary and equality before law, and individual liberties fundamental rights, such as physical integrity, property rights, human rights or the freedom of religion. Finally, fundamental rights such as freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of assembly are covered in the principle of public sphere. All four liberal principles ensure that the majority that won the elections or a popular vote cannot abuse its power and disregard fundamental rights and constitutional provisions which is the core idea of liberal democracy (Coppedge et al., Citation2011; Riker, Citation1982).

Table 1. Democratic principles.

Based on this multidimensional concept of democracy, we are able to derive more specific expectations about the politicization of democratic principles by different party families. First, from a strategic perspective, we expect a higher salience of democratic principles in the political rhetoric of left-libertarian and populist radical right parties than of other party families that have dominated politics for a long time (social democrats, liberals, conservatives/Christian democrats). As elaborated in the previous section, we argue that both party families have strategic incentives to criticize the political establishment and procedures due to their challenger status. Second, the detachment of politics from society can be criticized from an individual-centered and people-centered notion of democracy. Hence, in line with their ideological foundation, we expect both left-libertarian and populist radical right parties to emphasize the participatory principles of competition, representation and participation. Third, whether individual autonomy or ‘the people’ are at the core of the ideological foundation matters for the liberal principles of democracy. While left-libertarians are likely to promote and defend liberal principles, as they are in place to protect individual and minority rights within the political system, we expect that populist radical right parties oppose liberal principles of democracy because they constrain the power of ‘the people’. Specifically, we expect (i) that populist radical right parties are likely to attack the principles constraints and rule of law that set boundaries for the implementation of the will of the people, and the principle public sphere that allows the media to reflect a variety of opinions and not just the populist view. (ii) We do not expect much emphasis of left-libertarians on any liberal principle, as they share the ideal of liberal democracy that individual liberty must be protected. If they do nevertheless, they do so to promote individual liberties even more or to protect liberal principles against attacks from other parties.

Data and methods

To test which parties politicize which democratic principles and whether our expectations hold, we measure the salience attached by parties to the eight democratic principles in their political communication and the context in which they politicize those principles. Our sample includes all parties with parliamentary representation from Switzerland, Austria and Germany.

We selected these three countries because they have similar party systems with the same traditional party families, i.e., social democratic, conservative and liberal parties on the one hand, and the left-libertarian greens and populist radical right parties on the other.Footnote1 Furthermore, we have variation for two confounding factors. Age and government experience vary largely among the populist radical right, with a relatively young AfD with no government experience; the FPÖ, which has been successful for almost three decades despite experiencing painful party splits; and the SVP which participated in almost every Swiss cabinet since its transition from an agrarian to a populist radical right party in the 1990s. This allows us to explore differences between party families detached from the individual party’s age and status.

The selection of three neighboring and (mostly) German-speaking countries, however, sets some boundaries when it comes to the generalization of our results. In particular, the type of challenger parties can vary across countries. This is mainly the case in the countries of Southern and Eastern Europe with more challenger parties from the ideological center and the radical left (Kriesi & Pappas, Citation2015). Furthermore, our dictionary of liberal democracy might need some adjustments when applying it to different national contexts. The range of topics covered in the politicization of democracy and the words parties use for it, might be different in other countries. We discuss the limitations of our study in more detail at the end of the result section.

Press releases

To provide a measure of party attention that lends itself to an analysis over time, we rely on a comprehensive dataset of press releases from political parties published between January 2006 and March 2018 (Gessler & Hunger, Citation2022). Press releases are an ideal corpus for this study as unlike manifestos, they are published on a regular basis by all parties. They report on the activities of a party and have been previously used to study how politicians communicate with their constituents (e.g., Grimmer, Citation2010) as well as the issue attention of parties in response to voters (Klüver & Sagarzazu, Citation2016). In contrast to parliamentary debates and media coverage, press releases allow parties to choose what issues they want to speak to. Different from social media data, their length allows parties to discuss more complex issues. Finally, previous work has highlighted their relevance to voters (Klüver & Sagarzazu, Citation2016), media outlets (Haselmayer et al., Citation2017) and party competition (Gessler & Hunger, Citation2021). For each country, we include all parties that poll above the parliamentary threshold for most of our period of study and exist to the current day. presents the overall number of press releases by party.

Table 2. Number and time period of press releases.

To pre-process the press releases for analysis, we remove URLs, punctuation, numbers, and symbols and convert everything to lowercase. We also remove a list of German language stopwords and the names of ministers and members of parliament in each of the countries to retain only meaningful features. For some of the analysis described below that aims to reveal differences between parties, we remove additional features including party names, words for party groups and procedural words and offices that are only used by a single party.

A dictionary approach to the salience and context of democratic principles

We translate the eight principles into a nested dictionary, which we include in Table A1 in the Online Appendix. The entry words were at first derived deductively from the principles. For this purpose, two authors separately compiled lists of entry words. Words were included if both authors agreed, otherwise the inclusion was discussed. After constructing our initial dictionary, we also used latent semantic scaling (Watanabe, Citation2020) to expand our dictionary with additional terms. Additionally, we validated our keywords against the inclusion of false positives on a smaller set of documents. While we necessarily include some false positives, we attempt to reduce this bias by excluding words that have additional meaning in any of the countries (e.g., ‘Propaganda’ which also signifies any advertisement in the Swiss context). This procedure leaves us with between 7 and 55 dictionary entries for each principle.Footnote2

To measure the salience of the eight democratic principles, we apply the dictionary to the corpus of press releases using quantitative text analysis software (Benoit et al., Citation2018). We are not interested in the frequency of total mentions, but how often democratic principles are part of a press release. Therewith we divide the documents into those that mention a specific democratic principle and those that do not. Then, we calculate the salience of these principles by dividing the number of documents that mention the principle by the total number of documents. This procedure equally lends itself to the calculation of salience within shorter time periods, which we use for the statistical analysis.Footnote3

To assess how political parties specifically address these democratic principles, we rely on the same dictionary as used above. Instead of scoring documents on whether they mention a specific principle, we now analyse the context of these mentions by extracting the ten words that precede and the ten words that follow our dictionary entry. This way, we generate a new text corpus with context words for each principle. To contrast populist radical right from left-libertarian parties, we calculate the keyness of these context words for each party. That is, we look at which words are within a 10-word window including the entry words we use to identify democratic principles (Stubbs, Citation2010) and use a χ2-test to measure whether we find a statistically significant difference between the word frequency among populist radical right and left-libertarian parties. This tells us more about the thematic context in which the parties embed their democratic critique, and in some cases, allows us to grasp differences in the parties’ tone (general or specific, positive or negative) when mentioning a democratic principle.Footnote4

Results

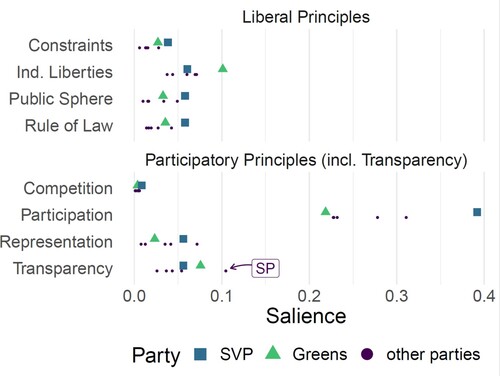

Starting with the results for the Swiss parties, illustrates the salience of each of the eight principles of democracy in the press releases of all major parties in Switzerland. Looking at the participatory principles (participation, representation and competition) we see that only participation has been mentioned frequently. As expected, the radical right SVP is leading the discourse. The Greens, other than predicted, do not mention participation more than the other mainstream parties. With regard to the liberal principles of democracy, the parties mostly follow our predictions. The SVP has the highest share of press releases referring to the rule of law, constraints and public sphere, while the Greens emphasize individual liberties much more than all other parties in their communication.Footnote5 Finally, transparency is more salient in press releases of the Greens than those of the SVP. Surprisingly, a traditional party – the Social Democratic Party (SP) – refers to transparency the most.

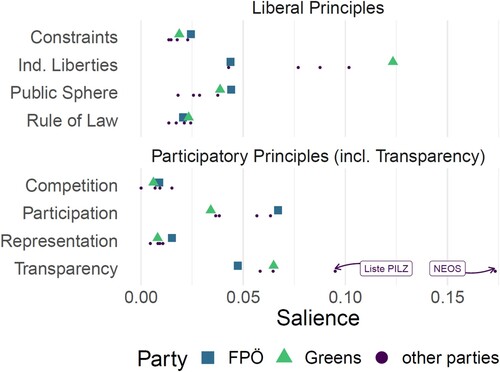

If we take a look at the democratic discourse in Austria displayed in , we have a similar picture as in Switzerland. Of the participatory principles, only participation stands out; and again, the populist radical right FPÖ is talking most about it. Regarding the liberal principles, the Greens are again clearly leading the discourse on individual liberties, while the FPÖ is putting slightly more emphasis on public sphere and constraints than the other parties. Finally, the transparency discourse is dominated by the new challenger parties Liste Pilz and NEOS for which we did not formulate any expectations since they do not belong to the two main families of challenger parties under focus.

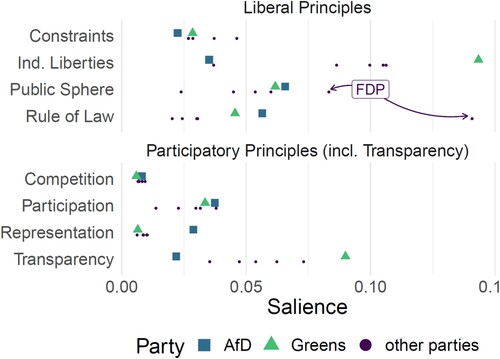

Turning to Germany, shows that the patterns are mostly in line with our expectations. Although participation is less politicized than in the other two countries – where voters have more direct democratic options – the AfD has (together with Die Linke), as expected, the highest score of salience. The distance to the Greens and the other mainstream parties is smaller than in the other two countries. Representation is also clearly more salient for the AfD than for all other parties. The Greens strongly emphasize transparency and individual liberties in their press releases and, other than in Switzerland and Austria, they are the leading party in both dimensions. When we look at the liberal principles that constrain the power of the majority – rule of law, public sphere and constraints – the AfD refers more to them than most other mainstream parties (with the exception of constraints). Another party, however, namely the liberal FDP has surprisingly high values on the dimension of rule of law and public sphere and surpasses the AfD.

In sum, we see in all three countries that the populist radical right parties AfD, FPÖ and SVP are at the top of politicizing the participatory dimension and liberal elements that constrain majoritarian rule. Greens are surprising in that they less often refer to participatory principles, but rather focus on the dimension of individual liberties.

These patterns are also confirmed in our next analysis where we group each national party into a party family (Radical Left, Social Democrats, Left Libertarian, Liberal, Conservatives and Populist Radical Right, see ) and analyze which party families refer to which principles most often. We rely on a data set where each party per 6 months is the unit of analysis. We then estimate a linear regression for each principle where we include country and time fixed effects as well as indicators for the party family. The Conservatives form the reference category. summarizes the results and shows the coefficients of all party families in comparison to the conservatives (dashed line). Full regression tables are in the Online Appendix (see Table A2).Footnote6

Figure 4. Party families and the salience of democratic principles (linear regression model, baseline category: conservatives). The full model is displayed in Table A2 in the Online Appendix.

Three findings stand out immediately when looking at the more general pattern in . First, we find evidence for the claim that populist radical right parties talk more about participation than all other parties. This is also true, but less striking, for the second participatory element representation, but not for competition. While different from our expectations, but as already seen when examining country figures, left-libertarians do not emphasize these elements more than the other party families. Either they did so in the past but stopped when they became more established (Burchell, Citation2014) or the participatory element of their political discourse was never that strong. The fact that the party family patterns hold despite the large country differences in the overall salience of participation – in line with the availability of direct democratic institutions on the countries’ national level – strengthens the claim that populism favors participatory democracy.

Second, transparency does not find much attention among populist radical right parties, but does among left-libertarians, social democrats and liberals. The latter stems from the fact that in Germany and Switzerland the transparency discourse is dominated by the greens and the social democrats, and in Austria the new parties NEOS and Liste Pilz speak most about transparency. We did not have explicit expectations with regard to transparency, but the criticism of political processes would suggest that challenger parties are more critical of non-transparent procedures. While we can confirm this for green parties, and the new parties in Austria, we must clearly reject it with regard to the populist radical right.Footnote7

Finally, we see that left-libertarian parties score the most references to individual liberties, which corresponds with their core beliefs of individual autonomy. In line with the expectations, populist radical right parties are indifferent to individual liberties, as they do not play an important part in the populist and authoritarian view.

The remaining liberal principles – constraints, rule of law and public sphere – have generally received less attention from all parties than the just mentioned principles. Nevertheless, looking at we still find interesting patterns. Public sphere and rule of law are strongly politicized by populist radical right parties, which in all three countries expose the highest salience in one or both dimensions (when excluding the FDP in Germany). Different than expected, left-libertarians also score high on these dimensions.

In the context of political competition, it is possible that parties mention liberal principles not to attack but to defend them. In this case, we would expect that the left-libertarians defend liberal principles and populist radical right parties attack them. To know more about the tone of the discourse, we calculate the keyness statistics of words that surround the mentions of democratic principles. This tells us more about the thematic context in which parties embed their democratic critique. In the following, we focus on the principle public sphere, which both left-libertarians and the populist radical right emphasize in their press releases. In the Online Appendix A3, we also discuss the remaining salient principles.

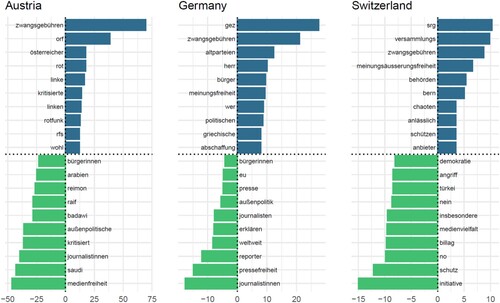

shows all relevant keywords that are collocated with the principle of public sphere. We provide the translation of these German keywords in the Online Appendix A3.1. The Figure provides evidence for the idea that the Greens mention liberal principles to defend them, while populist radical right parties attack them. Looking at the most relevant words in , we see that the FPÖ, the AfD and the SVP parties score high in the public sphere because of their attacks on public service broadcasting. They criticize the ‘zwangsgebühren’ (mandatory fees), talk about the ‘rotfunk’ (red broadcast) in Austria or associate public broadcasting with the ‘altparteien’, i.e., the established parties and their elites (Germany). The Green parties, on the other hand, explicitly name freedom of the press (‘Pressefreiheit’) and the plurality of media (‘Medienvielfalt’, ‘Medienfreiheit’) in all three countries which is, in the Swiss case, explicitly framed as under attack (‘angriff’). We see similar patterns in Figure A4 to Figure A6 in the Online Appendix with left-libertarian parties defending, and populist right parties attacking, liberal principles. However, our previous analysis of salience shows that we do not detect a bipolar discourse in the other two dimensions, as usually only one party dominates the discourse, while the topic is less salient for the other.

Our analyses reveal three important findings. First, populist radical right parties and left-libertarian parties are the main protagonists in the politicization of democratic principles. Second, direct forms of participation are highly salient in the discourse of populist radical right parties, in particular the Swiss SVP and the Austrian FPÖ but not (anymore) in the discourse of left-libertarian parties. Third, we find a bipolar partisan divide on issues regarding the public sphere – a core principle of liberal democracy. This finding is important, as it shows that the divide about liberal components of democracy runs mainly between different types of challenger parties rather than mainstream parties defending the status quo against the populist radical right, although with some exceptions. In the case of Switzerland, and to some extent Germany, the social democrats are joining the Greens in their defense.

We should of course be cautious when generalizing these findings to other contexts. Public broadcasting is a salient topic in all three countries, but this might vary across countries depending also on how the state regulates and finances public broadcasters. Furthermore, our dictionary is case sensitive as we included words that are very particular for the German-speaking context. Hence, if researchers want to apply the dictionary to different contexts to see whether the results travel, it is important to adjust it to the national context. Finally, countries in which other challenger parties than the populist radical right and the left-libertarians are the main drivers of political transformations might display different patterns in the politicization of democracy (see, e.g., Italy and the rise of the Five Star Movement).

Conclusion

In this paper, we argue and empirically demonstrate that parties in advanced democracies politicize different dimensions of liberal democracy. Challenger parties generally have a higher incentive to strategically put issues of democratic governance onto the agenda. Which principles exactly they challenge is determined by their political ideology.

We show that left-libertarian and populist radical right parties dominate the debate about democratic principles in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Left-libertarians, which are the Swiss, Austrian and German Greens, focus on principles that enhance individual autonomy within the political sphere, such as individual liberties and to some extent also transparency, while the populist radical right parties SVP, FPÖ and the AfD seek more direct forms of political participation and weaker liberal principles that restrain majoritarian rule. Against our theoretical expectations, we find that left-libertarians do not talk more about participatory principles than the traditional party families. However, we find that they defend liberal principles, particularly freedom of the press, against the attacks of the populist radical right. We also find some country-specific variation when it comes to the politicization of democratic principles by other party families. In particular, we find that other (challenger) parties such as the NEOS and Liste Pilz in Austria, the Social Democrats in Switzerland or the German FDP emphasize some democratic principles more than other parties.

In this study, we have limited our analyses to explore differences between party families. We argue that the differences between the traditional party families, and the populist radical right and green parties, are due to strategic incentives for the latter, while the reason for the different nature of their democratic discourse lies in the distinct ideological foundations. Postmaterialism leads to the emphasis of individual autonomy and hence embraces liberal principles of democracy, while authoritarian populism weighs participatory and majoritarian principles over the protection of individual liberties and minority rights. While the empirical findings mostly support our theoretical expectations for the different party families, we cannot empirically test if the strategic and ideological considerations are the reason for these patterns.

To empirically disentangle the impact of strategic and ideological considerations on the politicization of democracy, future research should not only cover more countries to account for varying political contexts, but also look at the variation over time to assess the effect of other potential strategic incentives, such as the government-opposition status of parties, the impact of external events on the politicization of democracy, or the behavior of other parties.

This article demonstrates the importance of the issue of democratic governance for the structure of party competition in a changing European political space. This issue so far has received much less scholarly attention than for example the question of European integration. Our first analysis of this topic speaks for the fact that questions of democratic governance could play an important and yet under-investigated role for the development of a transnational cleavage in European politics. Questioning fundamental principles of democracy often implies a confrontation with European ideals. As the example of Hungary (and the increasingly Eurosceptic party Fidesz) illustrates, once a party is involved in a democratic recession the discourse about transnational and democratic governance converges even more.

Our findings also contribute to a better understanding of populist and anti-elite politics. While theoretical work on populism and the radical right has discussed the importance of different dimensions of democratic governance for their ideology, we are the first to systematically demonstrate this empirically. We show that it is necessary to disentangle different dimensions of democracy in order to understand the appeal of the radical right on this dimension. This differentiation should help scholars of the demand side of radical right politics to analyze how, when and why populist appeals are successful.

Finally, we contribute to the debate on democratic erosion by methodologically developing and illustrating an approach that allows us to investigate how parties challenge liberal democracy. While previous work has used press releases to study salient issues such as immigration or the economy (Gessler & Hunger, Citation2021; Klüver & Sagarzazu, Citation2016), we show that democratic principles are also discussed in party’s press releases. Substantively, this paper provides a first analysis of which elements are challenged by parties and we are able to show how this is related to their ideological foundations. We thus demonstrate that it is necessary to distinguish different principles of liberal democracy if we want to adequately assess how democracy is challenged – and potentially – eroded through a process endogenous to democratic competition. Simply put, not all critique of liberal democracy is the same. Politicization of some of its elements might be desirable or even necessary to sustain democratic practices. Hence, in order to understand the potential threat that populist radical right parties pose to liberal democracy, it is necessary to distinguish the different elements of democracy that they are trying to attack – not only in our theoretical accounts but also in our empirical analyses.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (452.6 KB)Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 2019 EUROLAB authors’ Conference in Cologne, 2019 ECPR General Conference in Wrocław, the IPZ Publication Seminar at the University of Zurich, the 2020 Annual Meeting of the SPSA in Lucerne and the 2021 Virtual Conference of Europeanists (CES). The authors have received valuable comments from three anonymous reviewers, Matthew E. Bergman, Paula Ganga, Ralph Schroeder, Simon Bornschier, Stijn van Kessel and Matthias Enggist. The authors are thankful to Nadine Golinelli for impeccable research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Supporting data and materials for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8F8FKP (Harvard Dataverse).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sarah Engler

Sarah Engler is a Guest Professor for Direct Democracy and Political Participation at the Department of Political Science and the Centre for Democracy Studies, University of Zurich.

Theresa Gessler

Theresa Gessler is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at the European University Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder). She is also an affiliated researcher at the Department of Political Science, University of Zurich.

Tarik Abou-Chadi

Tarik Abou-Chadi is an Associate Professor of European Union and Comparative European Politics at Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

Lucas Leemann

Lucas Leemann is an Associate Professor for Comparative Politics and Empirical Democracy Research at the University of Zurich.

Notes

1 The liberal party NEOS is an exception, as there is no traditional liberal party in Austria. NEOS is a new party that emerged in 2012 and can be considered a challenger party. We label it according to its ideology as liberal (Döring & Manow, Citation2016), but discuss its democratic positions separately. Robustness checks excluding NEOS from the liberal party family are included in the Online Appendix (see Table A3). The same procedure has been applied with regard to another liberal party, the green-liberal party GLP in Switzerland, which promotes ecological positions and liberal economic stances.

2 The varying number of entries for each principle does not imply that our measurements are more accurate for one principle than for another. Often, the number of entries is simply higher because we have to include different words for each country (e.g., ‘freunderlwirtschaft’, ‘vetternwirtschaft’, ‘vetterleswirtschaft’) or different notations (e.g., ‘freie Presse’, ‘freie Preße’).

3 To assess how well our dictionary can classify democratic principles, we also asked a research assistant to manually code whether press releases touch on one of the democratic principles for a stratified random sample of 760 party statements (see Online Appendix A4).

4 An alternative approach would be the use of sentiment analysis to measure positions. We consider an analysis of the context more suitable than sentiment given the character of democratic principles where we expect parties to differ in their framing more than in the polarity of their statements.

5 Figure A1–Figure A3 in the Online Appendix provide party labels for each party and confidence intervals.

6 As a robustness test, we also look at overall accuracy and whether it differs systematically by party family. We present these results in the Online Appendix A4. There is no sign of systematic measurement error.

7 Table A3 in the Online Appendix shows the coefficients of all party families when excluding the new liberal parties greenliberals and NEOS from the model. It shows that the positive effect of the liberal party family was mostly driven by new liberal parties.

References

- Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., & Matsuo, A. (2018). Quanteda: An r package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

- Bühlmann, M., Merkel, W., Müller, L., & Weßels, B. (2012). The democracy barometer: A new instrument to measure the quality of democracy and its potential for comparative research. European Political Science, 11(4), 519–536. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2011.46

- Burchell, J. (2014). The evolution of green politics: Development and change within European Green Parties. Routledge.

- Capoccia, G. (2002). Anti-system parties. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 14(1), 9–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/095169280201400103

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, S., Hicken, A., Kroenig, M., Lindberg, S. I., McMann, K., Paxton, P., Semetko, H. A., Skaaning, S.-E., Staton, J., & Teorell, J. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: A new approach. Perspectives on Politics, 9(2), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711000880

- Dahl, R. A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition. Yale University Press.

- de Vries, C. E., & Hobolt, S. B. (2012). When dimensions collide: The electoral success of issue entrepreneurs. European Union Politics, 13(2), 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116511434788

- de Vries, C., & Hobolt, S. B. (2020). Political entrepreneurs: The rise of challenger parties in Europe. Princeton University Press.

- Diamond, L., Plattner, M. F., & Rice, C. (2015). Democracy in decline? Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2016). Parliaments and governments database (parlgov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies. Development Version.

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper & Row.

- Gessler, T., & Hunger, S. (2021). How the refugee crisis and radical right parties shape party competition on immigration. Political Science Research and Methods, 10(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.64

- Gessler, T., & Hunger, S. (2022), Party press releases – Austria, Germany, Switzerland. doi:10.7910/DVN/TXKO19

- Grimmer, J. (2010). A Bayesian hierarchical topic model for political texts: Measuring expressed agendas in senate press releases. Political Analysis, 18(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpp034

- Haselmayer, M., Wagner, M., & Meyer, T. M. (2017). Partisan bias in message selection: Media gate-keeping of party press releases. Political Communication, 34(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1265619

- Hobolt, S. B., & de Vries, C. E. (2016). Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science, 19(1), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles among Western publics. Princeton University Press.

- Kelemen, R. D. (2020). The European union’s authoritarian equilibrium. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1712455

- Kitschelt, H. (1989). The logics of party formation: Ecological politics in Belgium and West Germany. Cornell University Press.

- Kitschelt, H. (1994). The transformation of European social democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Klüver, H., & Sagarzazu, I. (2016). Setting the agenda or responding to voters? Political parties, voters and issue attention. West European Politics, 39(2), 380–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1101295

- Kriesi, H., & Pappas, T. S. (2015). European populism in the shadow of the great recession. ECPR Press.

- Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies die. Penguin Random House Audio.

- Merkel, W. (2004). Embedded and defective democracies. Democratization, 11(5), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340412331304598

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1667–1693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018789490

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press.

- Pappas, T. S. (2019). Populism and liberal democracy: A comparative and theoretical analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Riker, W. H. (1982). Liberalism against populism: A confrontation between the theory of democracy and the theory of social choice. Waveland Press.

- Sartori, G. (1967). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis (Vol. I). Cambridge University Press.

- Stubbs, M. (2010). Three concepts of keywords. In M. Bondi & M. Scott (Eds.), Keyness in texts (pp. 21–42). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Watanabe, K. (2020). Latent semantic scaling: A semisupervised text analysis technique for new domains and languages. Communication Methods and Measures, 0(0), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1832976