ABSTRACT

Under what conditions do citizens consider external sanctions against their country to be appropriate? Based on the literature on blame shifting, we argue that citizens should become less likely to support external sanctions if their government defends itself, especially if it seeks to shift the blame to the external actors (blame effect). However, this effect may be moderated by which actor identifies and claims the norm violation (source effect) and by whether citizens trust their government (trust effect). We test our expectations by conducting a survey experiment on EU sanctions against democratic backsliding in six countries (n = 12,000). Our results corroborate the blame and source effects, but disconfirm the trust effect. These findings have important implications for the literatures on blame shifting and external sanctions as well as for how the EU and other International Organizations should design their sanctioning mechanisms.

Introduction

Over the past decade, scholars and politicians alike have increasingly addressed the question of what the European Union (EU) could do to counteract tendencies towards democratic backsliding in the member states. While the discussion already started when the Austrian right-wing populist Freedom Party (FPÖ) joined a coalition government led by the Christian Democratic chancellor Wolfgang Schüssel in 2000, the debate became more salient as a consequence of the political developments toward more autocratic rule in Hungary and Poland since 2010. This has led scholars like Kelemen to note that ‘[t]oday, clearly, the greatest threats to democracy in Europe are found not at the EU level, but at the national level in the EU’s nascent autocracies’ (Kelemen, Citation2017).

As a result, legal scholars and political scientists have explored which sanctions could and should be deployed by EU authorities to make these countries return to liberal democracy and the rule of law (e.g., Blauberger & van Hüllen, Citation2021; Closa, Citation2020; Closa & Kochenov, Citation2016; Kochenov & Pech, Citation2015; Pech & Grogan, Citation2020; Scheppele, Citation2016), while others have warned that such sanctions – by means of autocratic governments seeking to shift the blame to the EU – may actually backfire and strengthen rather than weaken the rule of these governments (Schlipphak & Treib, Citation2017; see also Sedelmeier, Citation2017).

Interestingly, while this debate seems to be concentrated on the European case, it speaks to two so far rather separate but theoretically and empirically related questions in the International Relations literature. Under what conditions may supranational or international actors influence the domestic politics of states by imposing external sanctions? And under what conditions are domestic governments able to shift the blame for political shortcomings onto the international level?

In this article, we contribute to both of these literatures by aiming to answer the following research question: Under what conditions do citizens consider external sanctions against their own government to be appropriate? While using the EU as an empirical example, we will develop our arguments in a way that makes them applicable to other instances of external sanctions and domestic citizens’ acceptance of these sanctions as well.

Drawing on the insights of previous research, we argue, first, that governmental blaming of external sanctions as illegitimate interference into domestic politics will decrease the acceptability of such sanctions among citizens (the blame effect). Second, however, we expect that this delegitimizing effect can be moderated by the source that accuses the respective member state of the kind of misbehavior that results in external sanctions and by whether or not respondents have trust in their government in general. That is, the negative effect of governmental blame efforts should become weaker if the claim of the respective government’s misbehavior on which external sanctions are based comes from groups of its own citizens (the source effect). In addition, the negative effect of governmental blame efforts should be stronger among citizens having trust in their government (the trust effect).

We test the two parts of our argument by a self-administered survey experiment in six European countries with about 12,000 respondents. Our empirical findings provide support to both parts of our argument but with an important limitation. We find empirical evidence in support of the blame effect, indicating that a domestic government’s blaming of external sanctions – in contrast to the hypothesized moderating trust effect – also is successful among citizens who are skeptical toward the government. Hence, the EU, and international actors capable of imposing external sanctions more generally, should continue to be very cautious about applying their standard enforcement tools against countries that are considered to violate their rules. Instead, and based on the empirical confirmation of the moderating source effect, the EU, or International Organizations more generally, should work towards an alternative bottom-up enforcement mechanism. Such a mechanism should be independent of existing institutions and, most importantly, should be built around a citizen-centered complaint mechanism. This would make it harder, if not impossible, for accused governments to shift the blame to the EU or any other external organization.

Literature review

Researchers working on external sanctions and scholars addressing governmental blaming strategies have in recent years increasingly analyzed similar dynamics and mechanisms, but their work is still somewhat unconnected. In this review section, we will first sketch how the recent external sanctions literature has come to concentrate on the varying effects of external sanctions on autocratic incumbents. We show that this literature has in parts indicated the effectiveness of a mechanism that research focusing on political communication and EU politics has coined the blame-shifting mechanism. At the end of this review, however, we note that the effectiveness of this mechanism has not been empirically tested, nor have institutional configurations to prevent this mechanism from working found adequate theoretical and empirical consideration. In the theoretical part, we therefore turn to these two gaps in the literature that speak to both, the external sanctions and the blame-shifting research communities.

External sanctions are an instrument by powerful actors in the international setting to force weaker actors to comply with rules that are either unilaterally imposed by the more powerful actors or that the weaker actors have agreed to but fail to comply with. At times, objectively differentiating between these two situations is not an easy task, which provides room for the politicization and political contestation of external sanctions, as we will highlight in the next section. In general, however, external sanctions should be considered an instrument to make states – i.e., their governments – comply with rules. At the international level, external sanctions are most often employed to enforce rules in three domains: economic rules, rules relating to the use of certain weapons, and rules on human rights and democracy. Regarding the first domain, external sanctions are deployed to make states comply with economic and trade rules by international organizations like the World Trade Organization or the International Monetary Fund (Charnovitz, Citation2001). In the second domain, external sanctions are employed to prevent states from developing or acquiring weapons of mass destruction, such as nuclear bombs, or to force states to destroy such weapons (see, e.g., Solingen, Citation2012).

In the third domain, on which we focus in this article, external sanctions serve to make governments respect the principles of democracy, including human rights and the rule of law. In this domain, which also seems to stimulate most external sanction research by political scientists, the question of the effectiveness of external sanctions is – understandably – abundant (for recent critical reviews, Özdamar & Shahin, Citation2021; Peksen, Citation2019). Recent literature has analyzed whether such sanctions correlate with changes in institutional quality (Thanh Le et al., Citation2021) or has effects on human rights (Gutmann et al., Citation2020; Yu-Lin Liou et al., Citation2021), poverty and income (in)equality (Afesorgbor & Mahadevan, Citation2016; Kelishomi & Nisticò, Citation2022; Mun Jeong, Citation2020; Neuenkirch & Neumeier, Citation2016), and internal domestic and ethnic conflict (Hultman & Peksen, Citation2017; Lv & Xu, Citation2017; Peksen, Citation2016). The most important question, however, still is whether democratic sanctions – ‘those that explicitly aim to promote democracy’ (von Soest & Wahman, Citation2014, p. 957) – are actually effective in changing the democratic or autocratic situation and the stability of governmental actors in the targeted country. More than a decade ago, Wood (Citation2008) as well as Peksen and Drury (Citation2010) argued to the contrary, indicating that economic sanctions tend to result in a restriction of political liberties in the targeted countries. This finding has been echoed by more recent research on the effect of sanctions on civil liberties (Adam & Tsarsitalidou, Citation2019).

This negative view on the effectiveness of sanctions has been challenged by other authors, who argue that previous research has looked at the effect of all kinds of sanctions in general while one should focus only on sanctions employed to foster democracy. Such democratic sanctions do seem to affect the democratic situation positively in the targeted countries (von Soest & Wahman, Citation2014). However, the mechanism of why this should be the case has only recently been explored in more detail. Grauvogel et al. (Citation2017) argue that external sanctions may be seen as a signal to domestic opposition groups to increase protest activities. In addition, Park (Citation2018) argues that sanctions negatively influence the incumbent’s electoral performance in the targeted countries and that this effect is greater for autocratic than for democratic leaders. Yet, these findings have been contrasted by others, as Licht (Citation2017, p. 143) demonstrates a very modest if at all existent effect of sanctions on the stability of political leadership, arguing that ‘[s]anctions rarely destabilize their targets’. And when it comes to the effect of sanctions on protest activities, Hellmeier (Citation2021) shows that external (threats to employ) sanctions actually inspire pro-governmental mobilization. Hellmeier argues that this is because external sanctions provide domestic (autocratic) leaders with the opportunity to ‘fuel nationalist sentiments and frame foreign interventions as an attack on the nation as a whole’ (Hellmeier, Citation2021, p. 450). The same mechanism was already indicated to take place by Peksen and Drury (Citation2010, p. 240), who consider economic sanctions as creating ‘new incentives for the political leadership […] to undermine the challenge of sanctions as an external threat to their authority’. Interestingly, Hellmeier (Citation2021) even uses the term blame in elaborating on this mechanism but none of the contributions reviewed so far explicitly link their analyses to the obviously connected research on blame-shifting, which has also become more relevant over the past ten years.

The literature on blaming, blame avoidance, blame shifting and blame games provides a bridge between external sanctions and the reactions of governments to such pressures. This literature has greatly proliferated in recent years (see, e.g., Heinkelmann-Wild et al., Citation2020; Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, Citation2020; Hinterleitner, Citation2020; Traber et al., Citation2020; Vasilopoulou et al., Citation2014; Vis, Citation2016). Yet, the origins of the argument date back to the works of Weaver (Citation1986) and McGraw (Citation1990, Citation1991), with the works of Hood (Citation2002, Citation2010; Hood et al., Citation2016), Rudolph (Citation2003) and Boin et al. (Citation2009, Citation2010) also making important contributions to the field.

This line of research mostly focuses on the factors inducing political actors to use blaming strategies and to counteract public responsibility attributions (Rittberger et al., Citation2017), which makes it relevant for understanding how governments may react to external sanctions. Scholars studying government communication in times of crises and external interventions have shown that governments tend to use blame avoidance strategies in such situations (Kriegmair et al., Citation2021). Moreover, different governmental actors seem to use different blame strategies, depending on the context of the crisis and on a country’s political and institutional context (see, e.g., Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, Citation2020; Traber et al., Citation2020). What has received comparatively little attention in the previous literature is the effect of such blaming strategies on public attitudes.

In our view, governmental blaming strategies and the public reactions to these blaming strategies provide the missing link between external sanctions and the – positive or negative – domestic impact of these sanctions. This is the starting point of our theoretical argument.

Effective blame shifting and the role of prosecutors

Governmental actors pursue blaming strategies to shift blame for an evident problem – a financial, economic or political crisis – away from themselves and onto other actors. Governmental actors employ such strategies in order to prevent the public from holding them responsible for the crisis and, as a consequence, punishing them in future elections. By shifting blame for a given problem onto others, governmental actors may not only prevent the public from holding them accountable for the crisis situation, but may, in addition, portray themselves as shield against those actors onto which they have shifted the blame.

Such a blame shifting endeavor seems to be most effective in cases of external interventions, as these external interventions – especially in a multilevel setting such as the European Union (Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, Citation2020) – provide much more leeway for governmental actors to blame external actors intervening into domestic politics. In essence, shifting blame onto international actors seems highly effective to governmental actors for two reasons. First, domestic publics are often less familiar with international actors as opposed to other domestic actors. Therefore, blaming these outside actors is likely to be more effective due to the public’s lack of knowledge about these actors. Second, blaming domestic (oppositional) actors might be dangerous for governments. While governmental actors should have the ability to influence politics in the domestic context, this is less credible for the opposition, which is – by definition – not in power. Hence, shifting blame for domestic failures to the opposition does not really work well for governmental actors: they would either be caught for the implausibility of the blame shifting or would be considered as politically weak. None of this should seem beneficial to governmental actors.

Applied to the political effects of external interventions, this implies that external sanctions, even if they may seem normatively well-founded, are likely to result in adverse domestic reactions as governmental actors using blame shifting strategies may be able to sustain or even gain further public support. This mechanism was spelled out by Schlipphak and Treib (Citation2017) for the reactions of member state governments to EU interventions against democratic backsliding. They argue that governmental actors are likely to blame the EU for interfering with domestic politics in order to convince their domestic audience that the EU’s intervention is illegitimate and, by implication, that it does not constitute an adequate reaction to the government’s activities. Governmental actors hence not only try to avoid responsibility for a problem, they also seek to place doubt on the very existence of a problem in the first place. In addition, this shifting of blame further intends to delegitimize the EU as the actor responsible for the illegitimate intervention into domestic affairs. Finally, the government will try to present itself as the only defender of national sovereignty against the illegitimate intervention of the EU.

While this argument has been repeatedly cited in very different strands of the literature,Footnote1 it has to our knowledge not been empirically tested or confirmed. Following Schlipphak and Treib, we hence first argue that governmental actors facing external interventions will shift blame to the external actors to shed doubt on the appropriateness of the intervention and hence to delegitimize the external actor. Formulated as an expectation:

H1 (blame effect): Governmental actors blaming an external actor for illegitimately interfering with domestic politics make a country’s citizens more skeptical about the appropriateness of the external actor’s behavior.

However, there may be moderating effects that may curb the effect of governmental blame shifting. The first moderating effect refers to a mechanism that has already been outlined in the writings of legal scholars and the political science literature focusing on the political consequences of EU sanctions but was also never empirically tested: the effect of the sources claiming that a government or member states breaches democratic and rule of law standards. The second moderating effect can be derived from political communication research on the effect of frames, narratives, and blame attempts more generally: the moderating effect of citizens’ trust in the sender of a message.

The role of prosecutors and governmental trust

Besides the two benefits of blaming actors from the international level that we outlined above, there is a third benefit that has so far received less attention: Shifting blame onto international actors perfectly feeds into the narrative of threats from the outside, which are typical for populist and authoritarian actors. It also makes the claim more credible that such outside actors can be portrayed as failing to understand the country’s political context and culture and, hence, can be claimed to see a problem where none exists, seen from an ‘inside’ perspective.

In the case of the EU, such storylines have been used by Polish and Hungarian actors in the past, claiming that the EU did not understand the specific characteristics of Polish and Hungarian conceptions of democracy, civil rights, media freedom, and the rule of law. As a result, governmental actors framed the EU’s criticism of Polish and Hungarian reforms as being based on alien ‘European’ values that contrast with the domestic culture. In essence, this framing then results in the argument that the EU imposes its own value system onto the domestic value system in a neo-colonial or even imperial way.

To prevent governments from using such storylines and thus to thwart the blame shifting mechanisms, a number of researchers have proposed to take the role of the prosecutor, i.e., the actor who claims that an intervention is needed due to the breach of international laws or rules, out of the hands of the respective international actor responsible for implementing the intervention. Instead, two options may limit the effect of governmental blame shifting. First, citizens from the countries in which such breaches take place should be allowed to file complaints against their own government’s actions (e.g., Schlipphak & Treib, Citation2017). This should make it much harder for the country’s government to shift blame for illegitimate interventions onto actors from the outside. In the examples mentioned above, Polish officials could easily argue that neither the European Commission nor any of the pro-interventionist member states may understand the Polish rule of law culture, but defending this argument against claims coming from Polish citizens is much less viable.

Second, others have argued that creating an institution composed of independent experts with a high degree of epistemic legitimacy and entrusting it with the role of the prosecutor may also be a tool to prevent governmental actors from successfully shifting the blame (e.g., Grabowska-Moroz, Citation2020; Müller, Citation2015). While the second approach emphasizes the role of experts instead of citizens and hence focuses more strongly of the effect of independence while the citizen approach highlights the role of internal (instead of external) criticism, the assumed mechanism of both proposals can be considered to be the same. The more distant the prosecuting actor is from the intervening actor, the harder it should become for governmental actors to effectively shift the blame onto the latter actor.

H2 (source effect): The effects expected in H1 become weaker if the breaches of international rules are reported by a country’s citizens or by a group of independent experts.

Following the political communication research here, we expect a moderating effect of citizens’ levels of trust in governmental actors for the effect of governmental blame shifting. Formulated as a hypothesis:

H3 (moderating trust effect): The effects expected in H1 are stronger among those citizens having trust in governmental actors.

Research design

To test our theoretical expectations, we chose first to limit ourselves to the case of EU interventions in member states that have been accused of breaching EU rules regarding the rule of law and democracy. While we discuss in more detail the implications of our empirical findings for interventions by external actors more generally in the conclusions, using the case of EU interventions in member states has three main benefits. First, in doing so we connect to the recent literature on the strategy of blame shifting and blame avoidance, which has focused heavily on the EU context. Second, focusing on EU interventions against democratic backsliding in the member states allows us to use experimental stimuli that are closely connected to real-world empirical phenomena, which increases the external validity of our experimental findings. And third, regarding the generalizability of our findings, we consider the EU to be a least-likely case for effective governmental blame shifting. If an EU member state becomes the target of EU sanctions, citizens will be much better informed about the external actor – that is, the EU – than if a country is confronted with external interventions by another regional organization or a powerful state. As the external actor in our case is more well-known to citizens than in other settings, it should become harder for governmental actors to successfully shift the blame.

To test our three hypotheses, we administered an online survey experiment in six countries, Germany, France, Poland, Hungary, Spain, and Denmark. The case selection covers a range of macro-level conditions that have generally been found to be of relevance for EU-related attitudes. It includes countries from Western, Eastern, Northern and Southern Europe; it encompasses founding member states as well as countries that have joined the EU in the 1970s, 1980s, and 2000s; it involves larger and smaller member states; and it covers richer net contributor as well as poorer net beneficiary countries.

We opted for 2,000 respondents per country to increase the power of the experimental conditions and interactions with potential moderators, such as citizens’ trust in government. The survey was fielded in September and October 2020 by KANTAR Germany in cooperation with the respective KANTAR offices in the respective countries. We double-checked the translations using native speakers and ran a pretest (with 25 respondents per country) so as to secure the highest standards of translation and survey quality.

Modelling strategy and test of hypotheses

In our survey experiment, we provided respondents with the following statement: ‘Finally, we are interested in what you think about violations of EU rules. Imagine that the European Union claims that [COUNTRY] has violated EU rules regarding democracy and the rule of law [A] The [COUNTRY’s] government defended its actions [B] Still, [COUNTRY] may now face sanctions’. [COUNTRY] stands for the respondent’s own country. A has four conditions and B has three conditions, with the first condition for both being a full stop (A1, B1). This results in one group (with the combination B1 and A1) that receives no substantive condition but only gets to read the text as provided above.

To test H1, we need to focus on the B conditions. The control group received B1 = ‘.’ as the baseline condition. We then test H1 by comparing the control group to the group receiving condition B2 = ‘and accused the EU of illegitimately interfering in [COUNTRY]’s domestic affairs.’. We also implemented another experimental condition that revolves around the familiar argument that the Coronavirus pandemic required the (temporary) suspension of civil rights and the rights of parliaments vis-à-vis the executive: B3 = ‘as having been necessary to safeguard its population against the detrimental effects of the Coronavirus’ (not plotted in ). This condition was added to check the robustness of the effect of B2. Given that this type of argument was used frequently in all countries in our sample, we expected this control condition to yield significant effects. In the remainder of this article, however, we focus on the test of our theoretical expectations by comparing the means of B2 and the baseline condition B1. The effects of the Coronavirus treatment are reported in the appendix (see models 4–6 in Table A3).

Table 1. Overview of experimental conditions relevant to test our hypotheses.

To test H2, we further explore the interactions between different combinations of A and B conditions. More specifically, we focus on differences between B1 and B2 varying over the conditions A1, A2, A3 and A4. In all conditions, the EU is claiming a breach of rules but the source informing this claim varies over the conditions. The conditions to measure the effects expected in H2 are A2 = ‘. This claim is based on a complaint by a group of [COUNTRY’s] citizens.’ and A3 = ‘. This claim is based on an assessment by an independent expert committee.’, which we compare to the baseline condition (A1 = ‘.’ – that is, no source informing the claim is mentioned). Besides, we also implemented a further condition in our experiment: A4 = ‘. This claim is based on an assessment by the European Commission.’

To analyze a potential moderating effect of citizens’ level of trust in government, which we expect in H3, we ran additional models including the proxy of citizens’ governmental or oppositional support, measured by the propensity to vote for a governing party compared to all other parties. First, respondents were asked to indicate on a scale from 0 to 10 how likely they are to cast a ballot for each of the main parties in their country. Second, if the likelihood of voting for any of the governing parties was higher than the likelihood of voting for any other main party, we attributed the value 1. In all other cases, respondents were attributed the value 0.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is respondents’ support of EU sanctions. After reading the experimentally varied statement, respondents were asked to answer the following question: ‘In your opinion, to what degree should the action of [COUNTRY] be sanctioned by the EU’. Possible answers range from 1 = ‘There should be no sanctions by the EU’ to 6 = ‘There should be severe sanctions by the EU’.

Potential context effects and control variables

Regarding potential context effects, we assume that especially the actual affectedness by EU accusations of democratic backsliding and the experience with blaming strategies by the domestic government may moderate the effect of the experimental conditions related to the blaming conditions. We may hence observe different effects of these conditions for Polish and Hungarian respondents compared to respondents from the four other countries. While we have no straightforward theoretical assumptions, the most plausible effect may be connected to what has been called pretreatment effects. Respondents from Poland and Hungary are likely to already factor in the familiar blaming strategies of their governments when making up their minds about EU sanctions. Therefore, they are less likely than respondents from other countries to react to the experimental stimulus of B2.

Furthermore, we asked citizens about their sociodemographic details, including age, gender, and education, in order to scrutinize whether the randomization of the experimental groups has actually worked. In addition, we checked whether citizens’ previous attitudes toward the external actor influenced the effect of the blame shifting mechanism by including an item measuring citizens’ attitudes toward the transfer of power to the European Union. Finally, we controlled for a potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by asking citizens whether they were suffering financial losses from the COVID-19 crisis.

Empirical findings

When looking at the descriptives and the distribution of demographics over experimental conditions, we do not observe any sign of problematic distributions that may influence the experimental setting and effects (see Table A2 in the appendix). We test H1 by analyzing the differences in means between B1 as the control condition and B2 as the blaming condition. and the first column of demonstrate that H1 is corroborated by our data. The government defending itself by blaming the external actor – in our case the EU – for illegitimately intervening into domestic politics makes respondents less favourable towards external sanctions against their country compared to a situation in which the government does not offer such a defense frame. The substantive size of the effect may seem relatively small, amounting to about 0.1 on a 6-point scale. As we will discuss in the conclusions in more detail, however, we still consider this effect to be meaningful if we extrapolate the experimental conditions to more authentic settings in real-world politics.

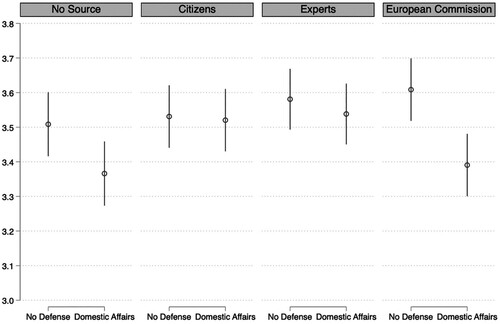

Figure 1. Comparing the effect of governmental blame shifting dependent on different sources of accusations.

Table 2. The effect of governmental blame shifting.

Moving to our second hypothesis, expecting the effect of governmental blaming to disappear if citizens or a group of independent experts are the source of the accusations against their own government, the second and third columns of demonstrate that H2 is actually confirmed by the data.Footnote3 These rows depict the effect of the governmental defense treatment among respondents who received the text in which the source of the accusations against the government was either a group of fellow citizens or a group of independent experts. Among the respondents receiving one of these two source cues, the governmental blame effect is no longer statistically significant. In addition, we observe that making the top executive representative of the external actor – in our case, the European Commission – the source of the accusations makes the effect of government blame shifting even more pronounced. These findings suggest that governmental blame shifting does not work if the source of the accusations is a group of fellow citizens or a group of independent experts.

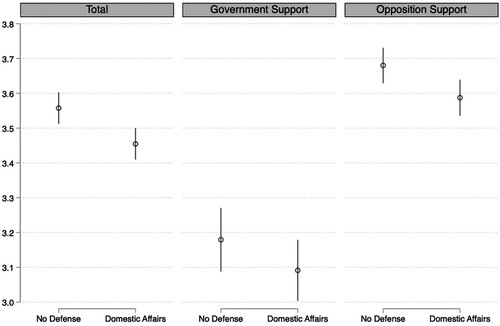

Moving to H3, we tested the expectation that respondents’ attitudes toward the government moderate the effect of governmental blame shifting. In we observe that supporters of government parties are much more skeptical of EU interventions than supporters of opposition parties, regardless of whether the government tries to shift the blame or not. However, the effect of the governmental blaming strategy is significant among supporters of opposition parties, while it is not significant among supporters of parties in government.Footnote4 This is contrary to the expectations of the political communication literature but it confirms the rally ‘round the flag-effect assumed by scholars like Schlipphak and Treib (Citation2017). Despite their expected lack of trust in governmental actors, supporters of opposition parties still follow the governmental blame frame and become more skeptical toward EU sanctions.

Figure 2. Comparing the effect of governmental blame shifting dependent on government or opposition support.

Robustness checks

*To provide transparent and reliable findings, we ran a number of additional analyses, which we plot in the appendix (see Table A3 for the empirical findings). When looking at our third B condition (Covid-19 vs. Control), which covers the governmental defense based on the need to combat the COVID 19 pandemic, the models show an even greater effect of this governmental framing compared to the blaming strategy (Models 4–6 in Table A3). This suggests that shifting the blame is not the only effective government strategy to defend itself. It might even be more effective to use other strategies, or to combine blaming with more policy-oriented defenses. Still, blame shifting alone has a significant effect on respondents’ support of EU sanctions.

Interestingly, we also find significant direct effects for the ‘Citizens’ and ‘Experts’ source treatments (the A condition). Although these results are not part of our main theoretical argument, they show that claims coming from experts and citizens are more accepted regardless of the defense from the government.

When looking at our control dimension of context effects, we observe some interesting differences across contexts. The effect of the governmental blame frame is strong and significant for respondents in the four western countries, but not for Polish and Hungarian respondents (see Table A4). We assume that this is due to respondents in Poland and Hungary automatically factoring in their governments’ EU blame frame when they hear about accusations of democratic backsliding and when they are asked to decide upon the severity of sanctions that they consider appropriate. This finding is in line with what has been called the pre-treatment effect, meaning that respondents have experienced the experimental stimuli in real life before the experiment. When looking at the differences of the source effect between Western and Eastern European countries, we observe the same patterns: First, citizens and independent experts being the source prevent governmental blame shifting from having a significant effect in both Western and Eastern Europe (Figures A3 and A4). Second, in the Eastern European countries, blame shifting does not have a separate effect on citizens’ attitudes if no specific source is provided. Third, however, specifically mentioning the European Commission as the source then results in a greater acceptance of the external sanctions among those who have not received the governmental blame shifting cue. We will come back to these findings in the conclusions.

Furthermore, when we connect the context dimension with our third hypothesis on the moderating effect of governmental trust, we find major differences between supporters of the government and supporters of the opposition – that is, those not trusting the government – in Poland and Hungary in their support of EU sanctions. The difference in means between these two groups adds up to more than one scale point on a scale from 1 to 6 (Figure A5). This picture is different in the remaining four countries. In the Western European member states, supporters of the opposition seem to be slightly more critical of EU interventions than government supporters (Figure A6). This observation may have to do with the fact that the group of opposition supporters is made up of higher numbers of Euroskeptics favouring right-wing populist parties in Denmark, France, and Germany.

In addition, in the appendix, we provide the classic ANOVA of our experimental conditions and their interaction (Table A5). In addition, we ran an OLS regression with both governmental defense conditions and source conditions and some control variables (age, gender, education) (Table A3). In doing so, we wanted to exclude the possibility that our findings are influenced by imbalances in the distribution of these basic socio-demographics in our experimental groups. We also checked whether prior attitudes toward EU authority have an influence on the effects of the blame shifting mechanism. The findings in Figure A7 demonstrate that this is only the case for strong Euroskeptics but not for all other respondents.

Finally, we tested whether respondents’ perception regarding the COVID 19 pandemic’s impact on their personal life alters the effects of governmental blame shifting, or the moderating effect of source and trust. As Figures A8 to A11 demonstrate, we do find similar results for those not affected by the pandemic as well as for those feeling slightly or even more severely affected. In sum, therefore, we find confirmatory results for a large number of robustness checks and hence consider our results to be reliable and valid.

Conclusions

Under what conditions do citizens consider external sanctions against their country to be appropriate? Linking two different strands of literature on external sanctions and the effects of governmental blame shifting, we derived two arguments that we tested in this article. First, we argue that governments can successfully shift blame for external sanctions to the external actor. In the case of the EU, we expected that blaming the EU for illegitimately interfering with domestic affairs should make citizens more skeptical regarding the appropriateness of EU sanctions. Second, we hold that the effect of blame shifting is likely to be moderated by the source of the accusations and the degree to which citizens trust the sender of the blaming message. Governmental blaming strategies should fail if the accusations do not emanate from the sanctioning actor, but are made by citizens from the respective country or a group of independent experts. In addition, governmental blame shifting should be moderated by the degree to which citizens have trust in their government. Using a self-administered survey experiment fielded in six EU member states, we find general empirical support for the blame effect and for the moderating source effect but not for the effect of governmental trust among citizens.

Analyzing an important control dimension indicates one further substantial finding that we will tackle in more detail in future research. We observe that our experimental stimuli concerning governmental blame shifting do not work in those countries that have primarily been confronted with EU allegations of democratic backsliding and (threatened or actual) EU sanctions: Hungary and Poland. In our view, however, this does not invalidate our theoretical argument. Instead, we argue that our experimental findings in these countries are biased by what has been called pretreatment effects (Slothuus, Citation2016). As the Polish and Hungarian governments have over the past years engaged in exactly the blaming strategies we envision in our argument, respondents in these countries are familiar with these blaming arguments and take them into account even without an experimental stimulus.

Our findings have important implications for current debates on external sanctions, governmental blame shifting, and more specifically, the literature on EU interventions. Regarding the external sanctions literature, our findings provide more credence to recent claims that external sanctions may actually strengthen rather than weaken domestic (autocratic) rulers (e.g., Hellmeier, Citation2021; Licht, Citation2017; Peksen & Drury, Citation2010). While some may find the EU a rather peculiar case to test a more general argument regarding sanctions imposed by external actors, we argue that the EU is a least-likely case for effective governmental blame shifting regarding external sanctions. As we outlined in the theoretical section, governmental blame shifting should work best if the sanctioning actor is rather unknown or unfamiliar to citizens. In the case of the EU, this condition is only partially fulfilled as EU citizens know comparably more about the EU than citizens know about other international organizations that may confront their country with sanctions. Hence, the EU context should make it particularly difficult for governments to blame the EU compared to a plentitude of other actors and cases of external sanctions. As our findings indicate that the governmental blaming strategies even work in the adverse EU context, we should expect blame shifting of governments to be even more successful in other contexts.

Our findings also lend support to the basic assumption underlying the research on (multilevel) blame shifting, blame avoidance, and blame games: that shifting blame actually works when it comes to sustaining public support for governmental policies (e.g., Heinkelmann-Wild et al., Citation2021; Kriegmair et al., Citation2021). There are some limits to the generalizability of this claim given the relatively small substantive size of our findings and the specific type of sanction that we employed in our empirical analysis. Nevertheless, our analysis sheds some first light on the topic and we are looking forward to delving more deeply into these questions in future research.

Finally, our research provides relevant knowledge to the more specific debate among EU scholars about whether the EU should sharpen its sanctioning toolbox and employ these sanctions against member states that violate EU norms with regard to democracy and the rule of law (Blauberger & van Hüllen, Citation2021; Closa, Citation2020; Gormley, Citation2017; Kochenov & Pech, Citation2015; Scheppele, Citation2016). The main lesson of our findings is that applying standard enforcement procedures involving EU institutions as prosecutors is vulnerable to successful government blame shifting. While the substantive size of the experimentally stimulated effects might seem rather small, there are three reasons why we nonetheless consider such blame frames to work even more effectively in reality.

First, we used a rather neutral tone for framing the experimental condition of the blame effect. In reality, as the communication by Viktor Orbán and the Polish PiS has demonstrated, such blame attributions are conveyed in a very emotional manner. In addition, such blame narratives are often accompanied by threat-inducing communication and attempts at sparking patriotic sentiments, for example by recalling collective memories of foreign domination during the Second World War or under Soviet reign (Notes from Poland, Citation2021). Our experiment avoids affective communication like this and still finds effects in line with the theoretical argument. Second, as our data show, these blame shifting mechanisms also work for respondents that support opposition parties – a group that is least likely to react to such blame attributions. Third, our (non-)findings for Hungary and Poland indicate that the argumentation in our experimental setup is so close to what goes on in reality that respondents no longer react to the experimental condition. Instead, hearing about the government defending itself against European-level accusations automatically triggers the familiar EU blaming mechanism – even if this is not explicitly spelled out. For us, this indicates that what we designed in the experiment is actually very close to what happens in reality – albeit in a much more drastic form.

In a nutshell, then, our survey experiment demonstrated that people can be convinced by the argument that EU intervention constitutes an illegitimate interference with domestic affairs if the accusations emanate from the EU. Following the advice of those scholars who urge the Commission to make full use of its available enforcement tools in order to rectify cases of democratic backsliding is thus likely to backfire politically. The successful blame shifting of the accused governments is likely to further decrease citizens’ support of the EU and instead increase the domestic public support of the governments that are the target of EU interventions.

This does not mean that the EU needs to stand on the sidelines while authoritarian governments curb media freedom, dismantle the independence of the judiciary, and clamp down on their political opponents. Our results also show that governments’ blaming strategies against Brussels become ineffective if the accusations of democratic backsliding emanate not from the EU or its institutions but are based on a complaint by a group of domestic citizens or an independent expert committee. These moderating effects apply to respondents in all countries and are grist to the mills of scholars who have suggested alternatives to the standard enforcement mechanism for the special case of democratic backsliding. Our results lend support to the idea of drawing up an independent institution that collects and analyzes citizens’ complaints about government actions that seem to undermine democracy or the rule of law (Grabowska-Moroz, Citation2020; Müller, Citation2015; Schlipphak & Treib, Citation2017). Delegating the task of establishing whether a government has violated EU values to such an independent authority, whose assessment would be based on a bottom-up procedure involving citizen complaints, would make it harder for an accused government to shift the blame to the EU.

Replication materials

Supporting data and materials for this article can be accessed on the Taylor & Francis website, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2102671. The data for this article can be accessed at the Austrian Social Science Data Archive, doi: https://doi.org/10.11587/D3PZEA (data access requires registration)

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (707.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Isabel Hoffmann, Luisa Kunze, Elena Otto-Erley, Maike Pollmann and Simon Vöhringer for competent research assistance at various stages of putting together the dataset and the manuscript. We are also grateful to the four anonymous referees and the editors for their insightful comments, which have helped to improve the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bernd Schlipphak

Bernd Schlipphak is professor of social science research methods at the University of Münster, Germany.

Paul Meiners

Paul Meiners is a Ph.D. student in political science at the University of Münster, Germany.

Oliver Treib

Oliver Treib is professor of comparative policy analysis and research methods at the University of Münster, Germany.

Constantin Schäfer

Constantin Schäfer works as consultant and project manager for citizen participation at ifok GmbH, Germany, and he is an affiliated researcher at KU Leuven, Belgium.

Notes

1 E.g., Adler-Nissen & Zarakol, Citation2021; Blauberger & van Hüllen, Citation2021; Heinkelmann-Wild et al., Citation2021; Kriegmair et al., Citation2021; Kreuder-Sonnen, Citation2018; Turnbull-Dugarte & Devine, Citation2021; van der Brug et al., Citation2022.

2 This also seems in line with more recent observations in the external intervention literature that external sanctions promote the creation of increasing numbers of pro-governmental groups (Hellmeier, Citation2021).

3 A direct test of the differences in means can be found in Figure A1.

4 A direct test of the differences in means can be found in Figure A2.

References

- Aaroe, L. (2012). When citizens go against elite directions: Partisan cues and contrast effects on citizens’ attitudes. Party Politics, 18(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810380093

- Adam, A., & Tsarsitalidou, S. (2019). Do sanctions lead to a decline in civil liberties? Public Choice, 180(3-4), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-00628-6

- Adler-Nissen, R., & Zarakol, A. (2021). Struggles for recognition: The liberal international order and the merger of its discontents. International Organization, 75(2), 611–634. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000454

- Afesorgbor, S. K., & Mahadevan, R. (2016). The impact of economic sanctions on income inequality of target states. World Development, 83, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.03.015

- Blauberger, M., & van Hüllen, V. (2021). Conditionality of EU funds: An instrument to enforce EU fundamental values? Journal of European Integration, 43(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708337

- Boin, A., t Hart, P., & McConnell, A. (2009). Crisis exploitation: Political and policy impacts of framing contests. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802453221

- Boin, A., t Hart, P., McConnell, A., & Preston, T. (2010). Leadership style, crisis response, and blame management: The case of Hurricane Katrina. Public Administration, 88(3), 706–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01836.x

- Charnovitz, S. (2001). Rethinking WTO trade sanctions. American Journal of International Law, 95(4), 792–832. https://doi.org/10.2307/2674626

- Closa, C. (2020). Institutional logics and the EU’s limited sanctioning capacity under Article 7 TEU. International Political Science Review, 42(4), 501–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120908323

- Closa, C., & Kochenov, D. (2016). Reinforcing rule of law oversight in the European Union. Cambridge University Press.

- Druckman, J. N. (2001). On the limits of framing effects: Who can frame? The Journal of Politics, 63(4), 1041–1066. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00100

- Dür, A., & Schlipphak, B. (2021). Elite cueing and attitudes towards trade agreements: The case of TTIP. European Political Science Review, 13(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577392000034X

- Gormley, L. (2017). Infringement proceedings. In A. Jakab, & D. Kochenov (Eds.), The enforcement of EU law and values: Ensuring member states’ compliance (pp. 65–78). Oxford University Press.

- Grabowska-Moroz, B. (2020). The systemic implications of the vertical layering of the legal orders in the EU for the practice of the rule of law. RECONNECT Europe Deliverable 8.3.

- Grauvogel, J., Licht, A. A., & von Soest, C. (2017). Sanctions and signals: How international sanction threats trigger domestic protest in targeted regimes. International Studies Quarterly, 61(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqw044

- Gutmann, J., Neuenkirch, M., & Neumeier, F. (2020). Precision-guided or blunt? The effects of US economic sanctions on human rights. Public Choice, 185(1-2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-019-00746-9

- Heinkelmann-Wild, T., Kriegmair, L., & Rittberger, B. (2020). The EU multi-level system and the Europeanization of domestic blame games. Politics and Governance, 8(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i1.2522

- Heinkelmann-Wild, T., & Zangl, B. (2020). Multilevel blame games: Blame-shifting in the European Union. Governance, 33(4), 953–969. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12459

- Heinkelmann-Wild, T., Zangl, B., Rittberger, B., & Kriegmair, L. (2021). Blame shifting and blame obfuscation: The blame avoidance effects of delegation in the European union. European Journal of Political Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12503

- Hellmeier, S. (2021). How foreign pressure affects mass mobilization in favor of authoritarian regimes. European Journal of International Relations, 27(2), 450–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120934527

- Hinterleitner, M. (2020). Policy Controversies and Political Blame Games (Cambridge Studies in Comparative Public Policy). Cambridge University Press.

- Hood, C. (2002). The risk game and the blame game. Government and Opposition, 37(1), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-7053.00085

- Hood, C. (2010). The Blame Game: Spin, Bureaucracy and Self-Preservation in Government. Princeton University Press.

- Hood, C., Jennings, W., & Copeland, P. (2016). Blame avoidance in comparative perspective: Reactivity, staged retreat and efficacy. Public Administration, 94(2), 542–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12235

- Hultman, L., & Peksen, D. (2017). Successful or counterproductive coercion? The effect of international sanctions on conflict intensity. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(6), 1315–1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715603453

- Kelemen, R. D. (2017). Europe’s other democratic deficit: National authoritarianism in Europe’s democratic union. Government and Opposition, 52(2), 211–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.41

- Kelishomi, A. M., & Nisticò, R. (2022). Employment effects of economic sanctions in Iran. World Development, 151, 105760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105760

- Kertzer, J. D., & Zeitzoff, T. (2017). A bottom-up theory of public opinion about foreign policy. American Journal of Political Science, 61(3), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12314

- Kochenov, D., & Pech, L. (2015). Monitoring and enforcement of the rule of law in the EU: Rhetoric and reality. European Constitutional Law Review, 11(3), 512–540. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1574019615000358

- Kreuder-Sonnen, C. (2018). An authoritarian turn in Europe and European studies? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(3), 452–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1411383

- Kriegmair, L., Rittberger, B., Zangl, B., & Heinkelmann-Wild, T. (2021). Dolce far niente? Non-compliance and blame avoidance in the EU. West European Politics, 45(5), 1153–1174. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1909938

- Licht, A. A. (2017). Hazards or hassles: Modeling the effect of economic sanctions on leader survival with improved data. Political Science Research and Methods, 5(1), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2015.25

- Lv, Z., & Xu, T. (2017). The effect of economic sanctions on ethnic violence of target states: A panel data analysis. The Social Science Journal, 54(1), 102–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2016.11.005

- McGraw, K. M. (1990). Avoiding blame: An experimental investigation of political excuses and justifications. British Journal of Political Science, 20(1), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400005731

- McGraw, K. M. (1991). Managing blame: An experimental test of the effects of political accounts. American Political Science Review, 85(4), 1133–1157. https://doi.org/10.2307/1963939

- Mueller, J. E. (1970). Presidential popularity from Truman to Johnson. American Political Science Review, 64(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1955610

- Müller, J.-W. (2015). Should the EU protect democracy and the rule of law inside member states? European Law Journal, 21(2), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12124

- Mun Jeong, J. (2020). Economic sanctions and income inequality: Impacts of trade restrictions and foreign aid suspension on target countries. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 37(6), 674–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894219900759

- Neuenkirch, M., & Neumeier, F. (2016). The impact of US sanctions on poverty. Journal of Development Economics, 121, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.03.005

- Nicholson, S. P. (2012). Polarizing cues. American Journal of Political Science, 56(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00541.x

- Notes from Poland. (2021, September 10). “We will fight Brussels occupier” as we did the Germans and Soviets, says Polish official. Notes from Poland. Retrieved September 24, 2021, from https://notesfrompoland.com/2021/09/10/we-will-fight-brussels-occupier-as-we-did-the-germans-and-soviets-says-polish-official/

- Özdamar, Ö, & Shahin, E. (2021). Consequences of economic sanctions: The state of the art and paths forward. International Studies Review, 23(4), 1646–1671. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab029

- Park, B. B. (2018). How do sanctions affect incumbent electoral performance? Political Research Quarterly, 72(3), 744–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918804102

- Pech, L., & Grogan, J. (2020). Meaning and scope of the EU rule of law. RECONNECT Europe Deliverable 7.2.

- Peksen, D. (2016). Economic sanctions and official ethnic discrimination in target countries, 1950–2003. Defence and Peace Economics, 27(4), 480–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2014.920219

- Peksen, D. (2019). When do imposed economic sanctions work? A critical review of the sanctions effectiveness literature. Defence and Peace Economics, 30(6), 635–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2019.1625250

- Peksen, D., & Drury, A. C. (2010). Coercive or corrosive: The negative impact of economic sanctions on democracy. International Interactions, 36(3), 240–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2010.502436

- Rittberger, B., Schwarzenbeck, H., & Zangl, B. (2017). Where does the buck stop? Explaining public responsibility attributions in complex international institutions. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(4), 909–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12524

- Rudolph, T. J. (2003). Who’s responsible for the economy? The formation and consequences of responsibility attributions. American Journal of Political Science, 47(4), 698–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5907.00049

- Scheppele, K. L. (2016). Enforcing the basic principles of EU law through systemic infringement action. In C. Closa, & D. Kochenov (Eds.), Reinforing rule of law oversight in the European Union (pp. 105–132). Cambridge University Press.

- Schlipphak, B., & Treib, O. (2017). Playing the blame game on Brussels: The domestic political effects of EU interventions against democratic backsliding. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(3), 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1229359

- Sedelmeier, U. (2017). Political safeguards against democratic backsliding in the EU: The limits of material sanctions and the Scope of Social pressure. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(3), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1229358

- Slothuus, R. (2016). Assessing the influence of political parties on Public Opinion: The challenge from pretreatment effects. Political Communication, 33(2), 302–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1052892

- Solingen, E. (2012). Of dominoes and firewalls: The domestic, regional, and global politics of international diffusion. International Studies Quarterly, 56(4), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12034

- Thanh Le, H., Phuong Hoang, D., Ngoc Doan, T., Hong Pham, C., & Trung To, T. (2021). Global economic sanctions, global value chains and institutional quality: Empirical evidence from cross-country data. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 31(3), 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2022.2047218

- Traber, D., Schoonvelde, M., & Schumacher, G. (2020). Errors have been made, others will be blamed: Issue engagement and blame shifting in prime minister speeches during the economic crisis in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 59(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12340

- Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., & Devine, D. (2021). Can EU judicial intervention increase polity scepticism? Quasi-experimental evidence from Spain. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(6), 865–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1901963

- van der Brug, W., Gattermann, K., & de Vreese, C. H. (2022). Electoral responses to the increased contestation over European integration. The European Elections of 2019 and beyond. European Union Politics, 23(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165211036263

- Vasilopoulou, S., Halikiopoulou, D., & Exadaktylos, T. (2014). Greece in crisis: Austerity, populism and the politics of blame. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(2), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12093

- Vis, B. (2016). Taking stock of the comparative literature on the role of blame avoidance strategies in social policy reform. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 18(2), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2015.1005955

- von Soest, C., & Wahman, M. (2014). Are democratic sanctions really counterproductive? Democratization, 22(6), 957–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.888418

- Weaver, R. K. (1986). The politics of blame avoidance. Journal of Public Policy, 6(4), 371–398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00004219

- Wood, R. M. (2008). “A hand upon the throat of the nation”: Economic sanctions and state repression, 1976-2001. International Studies Quarterly, 52(3), 489–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2008.00512.x

- Yu-Lin Liou, R., Murdie, A., & Peksen, D. (2021). Revisiting the causal links between economic sanctions and human rights violations. Political Research Quarterly, 74(4), 808–821. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912920941596