ABSTRACT

This article analyses the development of the mix of EU climate policy instruments and the level of climate policy integration (CPI) in the twenty-first century. Complementing established criteria of ambition and stringency, analysis of the instrument mix and CPI enables a fuller assessment of the transformational potential of EU climate governance. We argue that both have significantly advanced towards matching the ‘super-wicked’ nature of the climate challenge, although important gaps and challenges remain in addressing all relevant sectors, barriers and drivers. First, EU climate governance has ‘thickened’ through a stepwise layering of various economic, regulatory, procedural, and informational instruments. Second, this thickening has gone hand in hand with an expansion and strengthening of CPI. The European Green Deal promises to further complement the instrument mix and to universalise and prioritise CPI, but major initiatives remain to be proposed and realised for the Green Deal to propel the needed comprehensive transformation.

Introduction

After more than three decades of EU climate policy and its analysis, we are still lacking a coherent set of criteria for assessing whether EU climate mitigation governance is ‘fit for purpose’. The evolution of EU climate policy is well documented, from first attempts in the 1980s and 1990s to the stepwise development and strengthening of a fuller policy framework in the 2000s and 2010s and finally to the European Green Deal launched in 2019 (e.g., Delbeke & Vis, Citation2019; Jordan & Moore, Citation2020; Kulovesi & Oberthür, Citation2020; Oberthür & Pallemaerts, Citation2010; Skjærseth et al., Citation2016). It is also widely acknowledged that the EU has built the most advanced climate policy framework among major world actors, underpinning its role as an international climate leader (Delbeke & Vis, Citation2019; Jordan & Moore, Citation2020; Kulovesi & Oberthür, Citation2020; Oberthür & Pallemaerts, Citation2010; Skjærseth et al., 2016; Oberthür & Dupont, Citation2021). However, there has been little clarity and reflection on the criteria for assessing the adequacy of EU climate governance for effectively mitigating climate change.

The literature has so far focused on two main criteria for assessing the adequacy of EU climate governance. First, the overall ambition as apparent from the medium- and long-term greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction targets has arguably been the most prominent benchmark (e.g., references above and Boasson & Wettestad, Citation2013; Dupont & Oberthür, Citation2015). Second, the literature has investigated the bindingness and stringency of the policy framework along the hard–soft continuum to determine the chances of effective implementation (e.g., Knodt & Schoenefeld, Citation2020; Oberthür, Citation2019). It has also highlighted the importance of other aspects such as public participation, durability/flexibility, mechanisms for revising the policy framework, innovation, and policy monitoring (e.g., Huitema et al., Citation2018; Jordan & Moore, Citation2022; Leipprand et al., Citation2020; Schoenefeld, Citation2021; Torney & O’Gorman, Citation2020) without systematically integrating them into an overall assessment of the policy framework.

We aim to complement the criteria of ambition and stringency to facilitate a more comprehensive assessment of climate policy frameworks and their transformational potential. Neither ambition nor stringency capture whether a policy framework is designed to effectively address the breadth, depth, and complexity of the ‘super-wicked’ climate challenge (Levin et al., Citation2012) and to propel the comprehensive socio-economic transformation required (Rosenbloom et al., Citation2019). We therefore derive from policy studies two additional criteria: (1) the thickness/diversity of the mix of policy instruments required to address the multiple barriers to, and drivers of, the transformation, and (2) the extent of climate policy integration (CPI) across relevant areas to achieve the needed comprehensive transformation. While not necessarily exhausting the issue, we suggest that these additional criteria capture key transformational requirements.

Applying these criteria to the development of EU climate governance in the twenty-first century, we find that the EU has significantly enhanced both its climate policy mix and CPI. First, the policy mix has seen a stepwise layering of diverse economic, regulatory, procedural, and informational instruments, varying across different sectors (which we refer to as ‘thickening’). Second, the sectoral scope and strength of CPI have significantly increased. Measures under the Green Deal promise additional upgrades but so far remain incomplete. As to the climate governance models presented in the introduction to this special issue (Boasson & Tatham, Citation2022), the process can be interpreted as a stepwise evolution from ‘market failure’ (with carbon pricing being particularly prominent) to incorporating ‘socio-technological change’ (regulatory instruments and subsidies) and ‘public support’ (certain procedural instruments and social support measures).

We develop our argument in three steps. We first introduce the two assessment criteria based on the relevant literature on policy instruments and CPI. On this basis, we then analyse the evolving EU climate policy mix and CPI from the early 2000s to the Green Deal. Finally, we synthesize the main findings and discuss their implications.

Assessment criteria: instrument mix and CPI

Thickening of the instrument mix

Although there is no agreement on a single typology, three substantive types of (environmental/climate) policy instruments are commonly distinguished (e.g., Pacheco-Vega, Citation2020; Wurzel et al., Citation2013, Citation2019, pp. 72–4). First, regulatory instruments rely on a ‘command-and-control’ approach which uses the coercive power of the law. They entail a variety of prescriptive behavioural standards such as emission limits and targets; product, process/production and environmental quality standards; and prohibitions/bans. Second, economic instruments aim to guide behaviour by affecting actors’ cost–benefit calculations. They include emissions trading and environmental/carbon taxes as means of pricing, but also subsidies (e.g., financial incentives for environmentally friendly production and consumption) and aspects of monetary policy, such as asset purchases by central banks. Third, informational instruments aim to stimulate learning by, e.g., consumers and investors, through providing information, creating awareness, and generating and diffusing knowledge. Examples include disclosure obligations, product labelling and educational measures and campaigns.Footnote1

In addition to these substantive policy instruments, the literature has acknowledged the role of procedural instruments. While regulatory, economic, and informational instruments aim to directly affect outcomes, procedural instruments are ‘designed to affect how a policy is formulated and implemented’ (Bali et al., Citation2021, p. 4). They hence primarily structure and provide input into the policymaking and implementation process (see also Howlett, Citation2019). The wide array of procedural tools includes delegation of decision-making, for example to agencies, national competent authorities or even societal actors (e.g., via voluntary agreements); planning, reporting, monitoring and review procedures; expert, stakeholder, and citizen participation; impact assessments; revision clauses, and access to justice. The notion of procedural instruments hence covers several specific aspects of EU climate governance addressed in the literature as discussed in the introduction (policy monitoring, public participation, revision mechanisms, etc.).

Procedural instruments possess particular relevance in climate governance. Given the long-term character of the climate challenge and changing technological, economic, social, and political conditions, procedural instruments such as programmed policy reviews and public participation can facilitate the regular reinforcement and adaptation of measures (Gheuens & Oberthür, Citation2021; Jordan & Moore, Citation2022; Leipprand et al., Citation2020). Contemporary political turbulence and successive crises further reinforce the rationale for such adaptability and procedural guidance (Howlett, Citation2019; von Homeyer et al., Citation2021).

Types of policy instruments are analytical constructs since empirically they regularly occur in combinations or mixes (e.g., Capano & Howlett, Citation2020; Wurzel et al., Citation2019). Even individual pieces of legislation may comprise different policy instruments. For example, combinations where regulatory targets are pursued through dedicated planning, reporting and review processes are increasingly common (Capano & Howlett, Citation2020; see also Sabel & Zeitlin, Citation2010). Larger legislative packages and policy frameworks are even more likely to constitute instrument mixes (Skjærseth, Citation2021; see also below).

The policy instruments and their mixes can be related to the three ideal-typical climate governance models proposed in the introductory article of this special issue (Boasson & Tatham, Citation2022). While there is no one-to-one correspondence, carbon pricing should feature prominently in the market failure model, regulatory instruments and targeted subsidies under the socio-technological change model, and procedural instruments enhancing public participation as well as social subsidies supporting vulnerable groups under the public support model.

We consider the ‘thickness’ of a policy mix to correspond to the number and diversity of different policy instruments it comprises. As such, our conceptualisation of a policy mix’s thickness builds on existing concepts of policy density (focusing on numbers) and policy output (e.g., Schaffrin et al., Citation2014, Citation2015; Schaub et al., Citation2022). Specifically, it takes account of both the number and the diversity of types and sub-types of policy instruments. For example, prima facie, a mix of four different policy instruments is thicker than one featuring three instruments (irrespective of the instrument types), whereas a mix containing three different types (e.g., economic, regulatory and procedural policy instruments) is considered thicker than a mix composed of an equal number of instruments belonging only to two types (e.g., economic and regulatory instruments). There is little reason to believe that either the number of instruments or their diversity per se would be more important for the thickness of the mix, but diversity may be particularly important for addressing super-wicked problems such as climate change (see below). In addition, a nuanced assessment of an instrument mix’s thickness may analyse the varying ‘weight’ or ‘importance’ of the different instruments (cf. Schaffrin et al., Citation2015). As a rough guide, we consider instruments’ importance to vary with the share of the problem (e.g., the share of emissions) they directly or indirectly address. In the absence of the resources required for an in-depth assessment (Schaffrin et al., Citation2015), the relative importance assigned to instruments in the existing literature and political discourse can serve as a proxy.

To be effective, any instrument mix should fit the problem it aims to address. We assume that, prima facie, a thicker instrument mix will correlate with higher effectiveness (on the effectiveness of instrument mixes, see Capano & Howlett, Citation2020; Rogge et al., Citation2017). Prominent economists have argued that climate change is a unitary challenge that can essentially be addressed with one type of policy instrument: carbon pricing (e.g., Aldy & Stavins, Citation2012). Yet, it is widely acknowledged that climate change constitutes a ‘super-wicked’ problem characterised by conceptual, causal and normative complexity, a long-term time horizon and global scope (e.g., Levin et al., Citation2012; Peters & Tarpey, Citation2019). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has highlighted the diversity of causes and effects and the variety of barriers and solutions within and across relevant sectors (e.g., IPCC, Citation2021; Citation2022a and Citation2022b). For example, economic and non-economic barriers in the buildings and transport sectors differ from those in power generation and large industry (Cullenward & Victor, Citation2020; IPCC, Citation2022b). The complexity and diversity of the challenge call for a corresponding diversity of policy instruments and thickness of the resulting policy mix (Rosenbloom et al., Citation2019). Our expectation is also in line with findings that instrument diversity tends to increase policy effectiveness in environmental policy more generally (Fernández-i-Marín et al., Citation2021).

Under these circumstances, we may expect the EU’s climate policy mix to grow thicker over time. With the elaboration of EU climate policy since the early 2000s (see below), it might seem logical that new policy instruments would gradually be added. More generally, policy analysts referring to historical institutionalist approaches have argued that new instruments are frequently ‘layered’ on top of existing ones (rather than replacing, modifying or repurposing them) (e.g., Howlett & Rayner, Citation2007). While policy portfolio expansion does not necessarily entail an increase in instrument diversity (Fernández-i-Marín et al., Citation2021), instrument mixes may hence thicken over time. Although it seems unlikely that instrument mixes would thicken indefinitely, it is not clear when we should expect the process to stop. The extraordinary scope of the climate challenge, its continued and even growing political salience and the persistent need to upgrade mitigation efforts might suggest enduring pressure for further policy development (see discussion in Schaffrin et al., Citation2014).

Whereas instrument mixes carry risks of incoherence, inconsistency and redundancy (Howlett & Rayner, Citation2007), there are mitigating factors. To start with, especially in the context of the super-wicked problem of climate change and contemporary political turbulence, some redundancy seems desirable to enhance policy resilience and the policy framework’s overall robustness (Howlett, Citation2019; Rosenbloom et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, certain procedural instruments, such as ex-ante impact assessments and ex-post evaluation and review, promise to reduce the risk of incoherence. Similarly, incremental policymaking that may be required for addressing the super-wicked climate problem (e.g., Levin et al., Citation2012) may also facilitate responding to incoherence and redundancy. Whether the risk of incoherence is thereby effectively addressed is primarily an empirical question.

Climate policy integration: scope and strength

As a variant of the broader concept of environmental policy integration, CPI refers to the incorporation of climate policy objectives across relevant policy sectors. It can result from climate policy itself and from changes of other sectoral policies (Adelle & Russel, Citation2013; Dupont, Citation2016; Jordan & Lenschow, Citation2010; Lafferty & Hovden, Citation2003).

We consider two dimensions of CPI as central for the assessment of climate governance (see also ). First, given the climate challenge’s super-wicked and crosscutting nature, a broad scope of CPI across relevant sectors can be expected to enhance climate governance. Effective responses require involvement of key GHG-emitting sectors, such as energy, transport, industry, buildings, agriculture and forestry. In addition, the transition to climate neutrality also requires alignment of more indirectly relevant policy sectors, such as finance, trade, research, social and foreign policy. These sectors play a critical role in securing the technological, financial, social and political conditions enabling the continuous advance of the long-term climate transition (e.g., Perlaviciute et al., Citation2021; Rosenbloom et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. The assessment criteria in overview.

Second, the contribution of CPI to effective climate governance can be expected to vary with its strength. Weak CPI merely requires climate objectives to be considered in sectoral decision-making without mandating their reflection in relevant outputs and outcomes. At the other end of the spectrum, strong CPI requires that decision-making gives climate objectives ‘principled priority’ (Lafferty & Hovden, Citation2003) so that the resulting substantive measures are, overall, aligned with those objectives (Dupont, Citation2016). Hence, our assessment of CPI’s strength goes beyond a purely procedural standard since it pays particular attention to the extent to which sectoral policies incorporate substantive priority to climate policy objectives. Put differently, we consider both procedural requirements and substantive measures in assessing the strength of CPI and suggest that strong CPI is only possible with significant substantive measures. Overall, we argue that stronger CPI renders a climate policy framework more effective.

The assessment criteria in overview

provides an overview of the benchmarks and analytical categories of the two assessment criteria of instrument mix and CPI. The assessment of CPI derives from an analysis of the same policy instruments considered in the assessment of the instrument mix. However, the benchmarks and main analytical categories employed are different. In this context, we acknowledge the significance of the European Commission’s general regulatory impact assessments of its legislative proposals, which reach beyond the sectoral policies considered. However, given their comprehensive scope and general nature, we consider them to be an important part of the baseline in our investigation of the evolution of CPI.

While it seems likely that the development of the instrument mix and CPI are correlated, the extent of this correlation appears to be an empirical question. There is little reason to believe that a thickening instrument mix would necessarily entail expanding CPI since it could occur in a stable set of sectors. In contrast, we may expect that an expanding sectoral scope of CPI may entail the addition of new policy instruments to address the specific conditions in different sectors. However, it is also possible that existing policy instruments would be extended to new sectors, be it because conditions are similar or as a result of path dependence.

The evolution of EU climate governance: policy instruments and CPI

Background: targets, packages, ambition, and stringency of EU climate governance

EU climate governance has advanced through consecutive decadal targets. After an initial goal of stabilising CO2 emissions by 2000, the EU has aimed at increasingly deeper GHG emission cuts of 8 per cent by 2008-2012, 20 per cent by 2020 and 55 per cent by 2030 (upgraded from an initial 40 per cent). Furthermore, it agreed on the goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 under the 2019 European Green Deal. In addition, the EU established targets for increasing the share of renewable energy and improving energy efficiency for 2020 (20 per cent each) and 2030 (32 per cent and 32.5 per cent, respectively), with the 2030 targets under upward review at the time of writing (European Commission, Citation2021a; Oberthür & Dupont, Citation2021).

These targets have been implemented through several legislative packages, with later packages both revising existing legislation and adding new elements (and further climate policies being developed beyond the packages). The adoption of differentiated GHG emission targets across EU member states in 2002 (burden/effort-sharing) and a Directive establishing the emissions trading system (ETS) in 2003 created firm foundations for achieving the emission target for 2008-2012. Adopted in 2009, the 2020 Climate and Energy Package (2020 Package) implemented the targets for 2020 and added a Renewable Energy Directive and a Directive on carbon capture and storage, with the 2012 Energy Efficiency Directive completing the package. Finalised in 2019, the 2030 Climate and Energy Policy Framework (2030 Framework) then aimed at implementing the initial 2030 emission reduction target of 40 per cent, including through integrating electricity market rules and adding Regulations on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (Governance Regulation) and on land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF). Finally, the Commission proposed a legislative ‘Fit for 55 Package’ in 2021 to implement the strengthened 2030 emission reduction target of 55 per cent towards the 2050 climate-neutrality target (von Homeyer et al., Citation2022). Both targets are enshrined in the European Climate Law adopted in 2021 under the European Green Deal strategy (European Commission, Citation2019). The Fit for 55 Package contains several new proposals as discussed below (on the legislative packages, see Delbeke & Vis, Citation2019; European Commission, Citation2021a; Jordan et al., Citation2010; Kulovesi & Oberthür, Citation2020; Oberthür & Pallemaerts, Citation2010; Skjærseth et al., Citation2016; see also Footnote2). The Commission’s REPowerEU plan proposed in May 2022 in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine entailed modifications and a strengthening of parts of the proposed Package (European Commission, Citation2022).

Table 2. Main EU climate and energy legislation.

As mentioned in the introduction, ambition and stringency have been established as two key criteria for the assessment of EU climate policy, which this article aims to complement. As a point of reference, we therefore here synthesise the assessment of EU climate policy according to these criteria. The ambition of EU climate policy reflected in the GHG emission reduction targets has consistently been the highest among the world’s major emitters, substantiating the EU’s international climate leadership (e.g., Oberthür & Dupont, Citation2021). Nonetheless, the emission targets have consistently left a significant gap to the EU’s fair contribution to limiting the increase of global mean temperatures to below 2 °C or even 1.5 °C, as envisaged in the 2015 Paris Agreement (Climate Action Tracker, Citation2021; Gheuens & Oberthür, Citation2021).

The stringency of EU climate governance has been reasonably high and relatively stable. Overall, policies have taken the form of binding EU legislation (Regulations, Directives, Decisions) and key obligations (of EU member states and others, e.g., car manufacturers) have been precise and prescriptive. Beyond the general enforcement system of EU law (including infringement proceedings), implementation has been promoted through specific mechanisms such as financial penalties (ETS Directive; CO2 and Cars Regulation) or specific response measures for non-compliance with member states’ national emission targets (Oberthür, Citation2019; see also Knodt & Schoenefeld, Citation2020). Despite important gaps and shortcomings (e.g., regarding energy efficiency), past emission targets have generally been overachieved, with the EU having realised a reduction of more than 30 per cent by 2020. However, achieving the 55 per cent target by 2030 remains challenging (EEA, Citation2021).

Methodologically, the empirical analysis below is based on existing accounts of EU climate policy and, especially for more recent developments, on an assessment of relevant documents and EU legislation. Based on our conceptual framing introduced in the previous section, we use these sources to appraise the development of the EU’s climate instrument mix and CPI. To this end, we determine the primary policy instrument types employed in the main pieces of relevant legislation that has been adopted and proposed (see also ), and apparent in other relevant EU policies, and assess the scope and strength of CPI. In the following, we discuss the growth of the EU’s climate policy mix per main type of instrument starting with economic instruments that featured prominently early on and ending with informational instruments that acquired increased importance especially in recent years.

The mix of policy instruments

Economic instruments acquired an initially central role in EU climate governance with the 2003 ETS Directive. As an early flagship of EU climate governance, the ETS established a carbon price for large industrial and power plants and was extended to domestic aviation in 2008 (effective 2012) (Jordan et al., Citation2010; Oberthür & Pallemaerts, Citation2010; Skjærseth & Wettestad, Citation2008). The ETS has remained an enduring core element of the EU’s climate policy mix, but it has evolved significantly, including through the addition of strong regulatory elements such as a ‘market stability reserve’ (see below).

Subsequently, however, few new economic instruments addressing GHG emissions were adopted until the late 2010s. The 2020 Package merely included a modest fund fed by ETS allowances to subsidise relevant innovation. New market-based elements included in regulatory instruments addressing member states’ emission targets (effort sharing), CO2 emission standards for cars, and the promotion of renewable energy (see below) did not primarily serve to reduce emissions but to allow exchanging over- against under-achievements (Jordan et al., Citation2010; Oberthür & Pallemaerts, Citation2010). Similarly, new State Aid Guidelines enacted in 2014 that subjected support schemes for renewables to a stronger market logic were mainly driven by competition policy concerns (Boasson, Citation2019). Finally, a new target to spend 20 per cent of the EU budget for 2014–2020 on climate-related matters had limited effects on actual expenditure (Rietig, Citation2021).

Only from the late 2010s onwards, a second wave of economic instruments emerged. It added large-scale subsidies to the economic-instrument portfolio. The 2030 Framework introduced two multi-billion Euro funds using a share of ETS revenues to support climate relevant innovation and modernisation. Furthermore, climate mainstreaming into the 2021–27 budget was raised to 30 per cent (Rietig, Citation2021), while an even larger share of COVID-19 recovery spending was dedicated to climate action (Dupont et al., Citation2020). This included a new EUR 17.5 billion Just Transition Fund supporting regions and sectors particularly dependent on fossil fuels or carbon-intensive processes (European Commission, Citation2019, pp. 15–17). Furthermore, the European Investment Bank moved to become the EU’s ‘Climate Bank’ by committing to phasing out fossil-fuel financing by the end of 2020 and increasing the share of climate funding to 50 per cent by 2025 (Dupont et al., Citation2020; EIB, Citation2020). The biennial list of cross-border energy infrastructure and interconnection Projects of Common Interest (qualifying projects for financial support) has also been increasingly greened since the 2010s (Couffon, Citation2021).

Under the European Green Deal, additional measures concerning emissions trading, fiscal policy, and even monetary policy are underway to complete the second wave. The Fit for 55 Package tabled in 2021 proposes to include maritime transport in the existing ETS and to create a separate ETS for buildings and transport accompanied by a Social Climate Fund to cushion social impacts. It also suggests that the aforementioned ETS funds for innovation and modernization be expanded and all income from the ETS be invested in the energy transition. Furthermore, the Package proposes a new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism to tax the carbon-content of certain emission-intensive imports, alongside a climate-guided revision of energy tax rates (European Commission, Citation2021a). Finally, the European Central Bank (ECB) has initiated an increased consideration of climate objectives in its monetary policy framework, including its asset purchase programme (ECB, Citation2021).

Prior to this second wave of economic instruments, regulatory instruments considerably expanded over the 2000s and the 2010s. As indicates, legislation addressed member states’ emission targets (burden/effort-sharing), energy efficiency standards for products, restrictions on fluorinated GHGs, and CO2 emission standards for passenger cars, vans and heavy-duty vehicles. Directives on promoting carbon capture and storage, the energy performance of buildings, renewable energy, and energy efficiency also established, and further developed, regulatory standards and frameworks. For example, the 2009 Directive on carbon capture and storage defined criteria for site selection and operation. Especially for buildings and energy efficiency, standards have remained relatively soft, including for ‘nearly zero energy buildings’ (introduced in 2010) and indicative energy efficiency targets for 2020 and 2030 (see above). Perhaps most prominently among the period’s regulatory push, the 2009 Renewable Energy Directive established an encompassing regulatory framework for the promotion of renewable energy across different areas (electricity, heating and cooling, transport), although the 2018 revision of the Directive abolished binding national renewables targets after 2020. Even the ETS became more regulated, especially with the elaboration of benchmarks for the free allocation of emission allowances to industry in the 2010s and the adoption of a market stability reserve in 2015 to withdraw excess emission allowances from the market. Furthermore, the 2019 reform of the electricity market addressed, among others, grid access for renewable energy, cross-border electricity flows, and emission standards for generation capacity held in reserve for grid-balancing purposes. The 2021 European Climate Law then enshrined the overall 2030 emission reduction target of 55 per cent and the 2050 climate-neutrality target in law. In its Fit for 55 Package, the Commission has tabled new regulatory proposals to scale up the use of green fuel in aviation and maritime transport, address methane emissions from the energy sector, integrate hydrogen into the gas market, and to introduce national targets for the sequestration of carbon in the LULUCF Regulation (for overviews, see Delbeke & Vis, Citation2019; Dupont & Oberthür, Citation2015; Jordan et al., Citation2010; Kulovesi & Oberthür, Citation2020; Oberthür & Pallemaerts, Citation2010; Skjærseth et al., Citation2016; see also European Commission, Citation2021a and note 2; ).

Early procedural instruments were few and had relatively low salience. The monitoring mechanism, as revised over the years, established and developed reporting requirements for member states on GHG emissions and related measures from 1993 onwards. Also, some of the primarily market-based and regulatory legislation discussed above included procedural components. For example, the ETS Directive established reporting and monitoring obligations for the installations covered, and the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Directives established obligations for preparing, submitting, and reviewing national plans. Also, the Strategic Energy Technology Plan launched in 2008 took a largely procedural approach to coordinating national and EU innovation policies, albeit with modest results (Eikeland & Skjærseth, Citation2021).

Only under the 2030 Framework elaborated in the late 2010s did procedural instruments become a self-standing core part of the instrument mix. Most importantly, the 2018 Governance Regulation introduced an encompassing system of planning, progress reporting, review and deliberation, integrating various pre-existing planning and reporting obligations, including on GHG emissions, renewable energy, and energy efficiency. Besides long-term strategies, member states were required to submit, as well as review and update every five years, integrated National Energy and Climate Plans in which they specified policies and contributions to the EU-wide targets, notably for renewables and energy efficiency. The new procedures also enhanced obligations for regional consultations and the involvement of stakeholders and the public in the preparation and implementation of these plans (Delbeke & Vis, Citation2019; Kulovesi & Oberthür, Citation2020). The 2018 LULUCF Regulation established a similar system, while also obliging member states to ensure that no net emissions occur from the sector (Savaresi et al., Citation2020).

Subsequently, the European Climate Law has been a further major step advancing procedural governance. Beyond codifying the 2030 and 2050 emission targets (see above), it establishes a framework for the future determination of the emission trajectory to 2050 and accompanying measures, especially by including guidance to the Commission for proposing an emission target for 2040 and an indicative emission budget for 2030-2050. It also obliges the Commission to ensure public participation and engage in elaborating indicative sectoral decarbonisation roadmaps with relevant stakeholders. Furthermore, it establishes a European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change to provide advice on EU climate targets and their implementation and invites member states to form national scientific advisory bodies (EU, Citation2021). The Climate Law’s 2050 climate-neutrality target, moreover, strengthens existing procedural instruments, notably the Governance Regulation, by providing clearer direction for planning, review and follow-up. Finally, the Commission has initiated a European Climate Pact to foster dialogue with citizens and bottom-up engagement under the Green Deal (European Commission, Citation2020a).

Informational instruments initially operated at modest levels, with significant growth in the 2020s, developing from an early focus on consumers towards targeting investors and the corporate sector. Selective energy efficiency labelling of household goods had already existed since the 1990s and has since been further developed. This was complemented by labelling requirements for CO2 emissions of cars in 1999 and energy performance certificates for buildings introduced in the otherwise primarily regulatory Energy Performance of Buildings Directive in 2002 (both with limited effects). Only in the late 2010s did the EU adopt a major green/sustainability classification for investments through establishing a sustainable finance taxonomy (Taxonomy Regulation: Och, Citation2020 – with heated debates in 2022 over the inclusion of nuclear energy and natural gas starting in 2023). Complementing this initiative, the Commission has presented proposals for a green bond standard (European Commission, Citation2021b) and for corporate sustainability reporting (European Commission, Citation2021c). Furthermore, the ECB’s climate action plan mentioned above includes measures to enhance transparency about climate risks in the financial system, especially through disclosure requirements for banks (ECB, Citation2021).

Climate policy integration

The development of the EU’s climate policy mix analysed above also entailed a significant enhancement of both the scope and strength of CPI. Until the late 2010s, two aspects were in focus. First, newly adopted economic and regulatory instruments gradually increased the coverage of key emission sectors: the ETS addressed the industry, power and aviation sectors; the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive regulated buildings; and CO2 performance standards for cars, vans, and heavy-duty vehicles covered parts of transport. Second, by jointly promoting renewable energy, energy efficiency, and emission reductions, the 2020 Package integrated climate and energy policy (see also ).

From the later 2010s, the extension of CPI’s scope accelerated, including through the 2030 Framework. By introducing integrated National Energy and Climate Plans, the Governance Regulation reinforced integrated planning and reporting on GHG emissions, renewable energy and energy efficiency. The aforementioned regulation of the electricity market also further advanced CPI in the energy sector. The LULUCF Regulation expanded CPI to forestry (Delbeke & Vis, Citation2019; Kulovesi & Oberthür, Citation2020). Beyond the 2030 Framework, CPI expanded into more indirectly emission-relevant sectors, including infrastructure-related policies (Projects of Common Interest).

The European Green Deal has initiated a further expansion. It aspires to extend CPI to virtually all policy sectors and initiatives, including (1) emission sectors such as maritime transport, agriculture, and additional aspects of buildings and mobility; (2) indirectly emission-relevant policies such as international trade, industrial policy, finance and investment, and research and innovation; and (3) flanking policies to address side-effects of the transition through, e.g., social and foreign policy (European Commission, Citation2019). The 2021 Fit for 55 Package proposed further strengthening and expanding the coverage of emission sectors, including through a new ETS for transport and buildings, the extension of the existing ETS to maritime transport and the promotion of green fuels in aviation and maritime transport. The proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism addresses trade policy. At the same time, a number of new and proposed instruments address finance and investment (including monetary policy), including the 2020 sustainable finance taxonomy, reinforced climate mainstreaming into the EU budget and the COVID-19 recovery funding, a proposed framework for green bonds, the proposed regulation of corporate sustainability reporting, and the strengthening of climate considerations in policies of the European Investment Bank and the ECB. Finally, with the envisaged Just Transition Mechanism to ‘leave no one behind’, including the already established Just Transition Fund and the proposed Social Climate Fund, CPI makes important forays into social policy.

Overall, the European Green Deal also entails a significant two-pronged increase in the strength of CPI. First, CPI is strengthened because of the aggregate thickening of the overall policy mix across relevant sectors and the establishment of the guiding 2050 climate-neutrality target. As a result, the weight of climate objectives grows substantially. Second, the Green Deal establishes a ‘principled priority’ of climate policy objectives by seeking to ensure that ‘all other EU initiatives live up to a green oath to “do no harm”’ (European Commission, Citation2019, p. 19). Whereas the Commission has vowed that its explanatory memoranda of new initiatives will explain how this ‘green oath’ is upheld (European Commission, Citation2019, p. 19), the 2021 European Climate Law obliges the Commission to ‘assess the consistency of any draft measure or legislative proposal (…) with the climate-neutrality objective’ and the interim targets for 2030 and 2040 (Art. 6.4), and to review the ‘consistency of Union measures with the climate-neutrality objective’ every five years (Art. 6.2).

Discussion

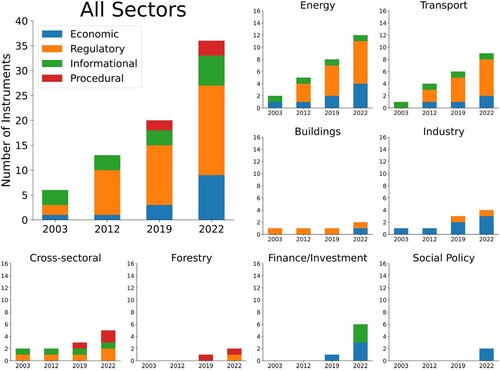

The EU’s climate policy mix has markedly thickened over time (see and Graph 1). An initial focus on emissions trading as an economic instrument was followed by a growing emphasis on regulatory instruments. Subsequently, the importance of procedural and economic instruments (including subsidies) grew considerably from the late 2010s. Informational instruments have played a smaller role that has increased in the 2020s by aiming to influence investors and the corporate sector in addition to consumers (see ). As of the early 2020s, all main types of policy instruments play a prominent role in the overall policy mix.

Graph 1. Evolution of EU climate policy mix (main legislative instruments).

Note: Derived from data in Table 2 and presented in text; for further explanation of method, see text.

This process has varied across sectors (see Graph 1). Whereas emissions trading addressed the power and industry sectors, economic instruments adopted and proposed later have targeted a growing number of directly and indirectly emission-related as well as flanking sectors, including transport, buildings, finance and investment, trade, social policy, and monetary policy. Regulatory instruments have had a focus on non-ETS emission sectors such as transport and buildings, as well as energy policy (renewable energy, energy efficiency and energy markets). Procedural instruments have especially been of a cross-sectoral scope, in addition to covering forestry. Initially, informational instruments largely targeted energy efficiency of consumer goods, before being extended to finance and investment and the corporate sector. This has resulted in varying and still evolving sectoral policy mixes, ranging from a focus on economic instruments (subsidies) in social policy to a use of all types of policy instruments in energy policy (taking into account the cross-sectoral scope of procedural instruments; see Graph 1).

This thickening of the instrument mix has entailed a considerable scope extension and strengthening of CPI. Regarding scope, specific climate-policy measures first increasingly addressed key emission sectors including industry, energy, transport, and buildings (later also LULUCF). CPI into indirectly relevant policy areas, such as finance and investment, trade, and monetary policy, subsequently gained prominence from the late 2010s, with the Green Deal aiming to capture all relevant policy fields. Ongoing CPI into social policy signals its expansion to flanking sectors to address negative side effects of climate policies. In this process, CPI has been significantly strengthened, including a potential step change in the context of the Green Deal. Beyond the strengthening inherent in the growth of policy instruments across relevant sectors, two developments under the Green Deal for the first time imply a move towards ‘principled priority’. First, the introduction of the 2050 climate-neutrality objective provides cross-sectoral guidance, supported by the obligation of the Commission to assess the consistency of all new proposals and existing measures with this objective. Second, the no-harm principle enshrined in the Green Deal also entails prioritising climate policy objectives.

Empirically, the thickening of the climate policy mix is closely linked to the expansion of CPI. Economic and informational instruments have grown from the late 2010s especially through the expanding coverage of non-emission sectors such as social policy, finance and investment, and monetary policy. Regulatory instruments have especially increased as part of the expansion of climate policy in non-ETS emission sectors such as transport, buildings, and forestry, and energy policy more broadly, including renewable energy, energy efficiency and energy markets. Key procedural instruments (such as the Governance Regulation and the European Climate Law) have themselves been cross-sectoral and have aimed at advancing CPI. Overall, CPI has hence been expanded through the addition of new policy instruments rather than the extension of existing ones.

Graph 1 illustrates the evolution of the EU’s climate policy mix, including its sectoral expansion and diversification. We distinguish four points in time, reflecting the major steps of the development of EU climate governance (2003: establishment of ETS and burden-sharing; 2012: completion of the 2020 Package; 2019: completion of the 2030 Framework; 2022: ongoing implementation of the Green Deal – see above). The graph is not exhaustive but illustrative. It reflects only the main legislative instruments of EU climate and energy governance listed in (but not other policies discussed in the text such as those pursued by the ECB, the European Investment Bank, and others). Where instruments apply to a limited number of sectors (two to three), they have been counted for each of these sectors but only once for the total covering all sectors. Instruments covering more sectors have been counted as ‘cross-sectoral’, which also means that the sectoral pictures are incomplete since not taking into account these cross-sectoral instruments. Each legislative instrument has normally been counted once, but where a piece of legislation has come to incorporate more than one key policy instrument (ETS, LULUCF Regulation, European Climate Law) it has been counted as two (or more) such instruments. This includes the case where instruments have been integrated into others. For example, the Monitoring Mechanism was incorporated into the 2019 Governance Regulation but is still counted as a separate instrument. It may also be worth noting that the graph does not reflect qualitative developments such as the substantive changes and stepwise strengthening of provisions of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive over successive rounds of revisions. Hence, the graph is illustrative of a significant part of the evolution and expansion of the EU climate policy mix.

Inconsistencies within the policy mix have been limited and have been progressively addressed in an incremental policy process, including impact assessments by the Commission. Hence, the creation of a market stability reserve to withdraw excess emission allowances under the ETS addressed downward pressure on ETS prices that was reinforced by progress on renewable energy and energy efficiency. Furthermore, the revisions of the Renewable Energy Directive have addressed potential negative effects of the promotion of biofuels on other land uses such as food production and forestry/biodiversity, although they may not have fully resolved the issue (Kulovesi & Oberthür, Citation2020; Skjærseth et al., Citation2016).

While our analysis has focused on tracing the growth, expansion and strengthening of EU climate governance, our approach in principle also lends itself to identifying remaining gaps and opportunities. The analysis of the sectoral policy mix provides a sound starting point for assessing to what extent evolving sector-specific barriers and drivers – as, for example, identified by the IPCC (Citation2022b) – have been addressed. For example, the LULUCF Regulation has arguably hardly promoted sustainable forestry practices (Savaresi et al., Citation2020). Similarly, prevalent soft regulatory standards and proposed economic instruments in the buildings and transport sectors may not yet have sufficiently addressed key aspects, such as inconsistent, ‘split’ incentives for building owners and/or tenants or modal shift and demand reduction in transport. In industry, the Green Deal explicitly acknowledges the need to complement existing economic instruments with a broader industrial strategy (European Commission, Citation2020b) and a strong focus on resource efficiency. The much-needed societal anchoring calls for the strengthening of procedural instruments for participatory mechanisms and access to justice (Kulovesi & Oberthür, Citation2020). CPI also remains to be further advanced, both in important emission sectors (e.g., agriculture: ECA, Citation2021) and other policy areas, such as international trade, foreign policy and social policy. Furthermore, the application of the ‘no (significant) harm principle’ (i.e., no harm to the objectives of the European Green Deal) in practice remains uncertain, not least because it requires action by EU member states (Bellona, Citation2021; Neuhoff & Lehne, Citation2020). Importantly, in focusing on preventing harm, the principle does not address the potential to maximise climate synergies across policy fields (e.g., in public procurement and others). A detailed gap assessment is, however, beyond the scope of this article.

Conclusions

Our analysis has shown that both the policy instrument mix and CPI have significantly advanced in EU climate governance in the twenty-first century. Over time, the EU has, with some sectoral variation, enacted an increasing number of climate policy instruments to arrive at a rich mix, including all main instrument types (economic, regulatory, informational, procedural) and diverse subtypes. EU climate governance has thereby moved from an early ‘market failure’ model prominently featuring carbon pricing towards first integrating ‘socio-technological change’ (through the roll-out of regulatory instruments and subsidies) and, more recently, elements of ‘public support’ through the strengthening of procedural governance and social subsidies (Boasson & Tatham, Citation2022). CPI has also been progressively extended and strengthened from directly emission-relevant sectors to more indirectly important and flanking policies. It may be no coincidence that both processes have gone hand in hand. After all, the expansion of CPI has entailed a sectoral differentiation and specialisation of EU climate policy that underpinned a diversification of policy instruments (e.g., the increase of economic and informational instruments in newly covered policy fields – see Graph 1).

Arguably, these developments have substantially enhanced the transformational potential of EU climate governance but would need to be further augmented to realise the required expedited transition towards climate neutrality. More specifically, the thickening of the instrument mix and the advances of CPI have improved the capacity of the policy framework to address the ‘super-wicked’, multifaceted climate challenge. The Green Deal promises further progress, not least through the expansion of economic, procedural and informational policy instruments to important indirectly relevant and flanking sectors. However, the road to climate neutrality by 2050 is still long. First, decisions already taken remain to be fully implemented by the Commission and the member states. Second, other important decisions are still awaited as part of the legislative Fit for 55 Package proposed in 2021 (as partially further strengthened by the Commission in 2022). Third, additional measures beyond this Package will be required to address remaining gaps and opportunities that will continue to evolve due to climate change’s growing urgency and dynamic socio-economic and -political nature.

Our analysis contributes to at least two scientific debates. First, it develops and operationalises two new criteria for a fuller assessment of the transformational potential of EU climate governance: the thickness of the instrument mix and the level of CPI. Our investigation demonstrates that these criteria can meaningfully complement the established criteria of ambition and stringency. Notably, they have displayed distinctive dynamics over time. As briefly discussed above, nominal increases of sequential emission targets (ambition) have followed a pattern of ‘too little too late’ and stringency has remained relatively stable. In contrast, the policy mix and CPI have both progressed stepwise towards exploiting their potential more fully. We do not claim that these two criteria necessarily complete the list of key assessment criteria, but we are confident that they constitute a valuable addition, including by enabling the systematic integration of additional governance aspects discussed in the literature, such as monitoring and procedures for policy development over time.

Second, we contribute to the debate about the effectiveness and evolution of policy mixes. Introducing the fit with the problem structure as a major criterion, we provide further support for the claim that a diversification of policy instruments (i.e., a thickening of the instrument mix) may advance climate governance (cf. Fernández-i-Marín et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, our analysis substantiates the link between increasing instrument diversity and cross-sectoral expansion. This raises interesting questions for future research, for example regarding the more precise relationship between instrument diversity, CPI and effective climate governance.

To conclude, we identify three routes for further advancing the research agenda towards a fuller understanding of the adequacy of climate policy frameworks. First, whereas this article has only been able to take a bird’s eye view, a more fine-grained analysis of the importance of individual instruments and of the fit of the instrument mix with specific sectoral, sub-sectoral and cross-sectoral conditions could further enhance the analysis. Second, an application of the proposed assessment criteria beyond the EU should be possible but may also need to reflect on whether different political and socio-economic framework conditions require different instrument mixes. Finally, a logical next step could be to identify the key factors driving and shaping the evolution of the instrument mix and CPI in the EU. Prime candidates may include the marked politicisation of climate policy since the late 2010s and the EU’s institutional set-up and competences. Such further analysis could generate important lessons for the future design of the EU’s climate policy framework.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the VUB’s Strategic Research Programme ‘Evaluating Democratic Governance in Europe’ (EDGE). They are also grateful for the comments and inputs by three anonymous reviewers, the special issue editors, and Brendan Moore.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sebastian Oberthür

Sebastian Oberthür is professor of environment and sustainable development at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, and professor of environmental policy and law at the University of Eastern Finland.

Ingmar von Homeyer

Ingmar von Homeyer is senior researcher at the Brussels School of Governance, Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Notes

1 This literature has also distinguished voluntary agreements as a separate type of policy instrument, which we subsume under procedural instruments (see below).

2 We here consider a set of legislative proposals tabled in December 2021 concerning gas markets and hydrogen, methane emissions in the energy sector, and the energy performance of buildings as part of the Fit for 55 Package; see and https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6682 (visited 6 April 2022).

References

- Adelle, C., & Russel, D. (2013). Climate policy integration: A case of déjà vu? Environmental Policy and Governance, 23(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1601

- Aldy, J. E., & Stavins, R. N. (2012). Using the market to address climate change: Insights from theory & experience. Daedalus, 141(2), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00145

- Bali, A. S., Howlett, M., Lewis, J. M., & Ramesh, M. (2021). Procedural policy tools in theory and practice. Policy and Society, 40(3), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2021.1965379

- Bellona. (2021). EU RRF ‘Do No Harm’ criteria fail to safeguard the resilience of the recovery. February 18, 2021. https://bellona.org/news/climate-change/2021-02-eu-rrf-do-no-harm-criteria-fail-to-safeguard-the-resilience-of-the-recovery.

- Boasson, E. (2019). Constitutionalization and entrepreneurship: Explaining increased EU steering of renewables support schemes. Politics and Governance, 7(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i1.1851

- Boasson, E. L., & Tatham, M. (2022). Climate policy: From complexity to consensus? Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2150272

- Boasson, E. L., & Wettestad, J. (2013). EU Climate Policy: Industry, Policy Innovation and External Environment. Ashgate.

- Capano, G., & Howlett, M. (2020). The knowns and unknowns of policy instrument analysis: Policy tools and the current research agenda on policy mixes. SAGE Open, 10(1), https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019900568

- Climate Action Tracker. (2021). EU, https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/eu/.

- Couffon, E. (2021). Is the TEN-E Regulation fit for a decarbonized future? A battle to shape the European energy transition. Briefings de l’Ifri. Ifri, June 9, 2021.

- Cullenward, D., & Victor, D. G. (2020). Making Climate Policy Work. Polity Press.

- Delbeke, J., & Vis, P. (2019). Towards a Climate-Neutral Europe: Curbing the Trend. Routledge.

- Dupont, C. (2016). Climate Policy Integration into EU Energy Policy. Routledge.

- Dupont, C., & Oberthür, S. (2015). Decarbonization in the European Union: Internal Policies and External Strategies. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dupont, C., Oberthür, S., & von Homeyer, I. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis: A critical juncture for EU climate policy development? Journal of European Integration, 42(8), 1095–1110. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1853117

- ECA. (2021). Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and climate. European Court of Auditors, Special report 16/2021.

- ECB. (2021). ECB presents action plan to include climate change considerations in its monetary policy strategy. European Central Bank press release. 8 July 2021, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2021/html/ecb.pr210708_1~f104919225.en.html.

- EEA. (2021). Trends and projections in Europe 2021, European Environment Agency, EEA Report No 13/ 2021.

- EIB. (2020). EIB climate strategy. European Investment Bank, https://www.eib.org/en/publications/eib-climate-strategy.

- Eikeland, P. O., & Skjærseth, J. B. (2021). The politics of low-carbon innovation: Implementing the European Union’s Strategic Energy Technology Plan. Energy Research & Social Science, 76), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102043

- EU. (2021). European climate law (Regulations (EU) 2021/1119).

- European Commission. (2019). The European Green Deal. COM(2019)640.

- European Commission. (2020a). European climate pact. COM(2020)788 Final.

- European Commission. (2020b). A new industrial strategy for Europe. COM/2020/102 Final.

- European Commission. (2021a). ‘Fit for 55’: Delivering the EU's 2030 climate target on the way to climate neutrality. COM/2021/550 Final.

- European Commission. (2021b). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on European green bonds. COM(2021) 391 Final.

- European Commission. (2021c). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards corporate sustainability reporting. COM(2021) 189 Final.

- European Commission. (2022). REPowerEU plan. COM(2022) 230 Final.

- Fernández-i-Marín, X., Knill, C., & Steinebach, Y. (2021). Studying policy design quality in comparative perspective. American Political Science Review, 115(3), 931–947. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000186

- Gheuens, J., & Oberthür, S. (2021). EU climate and energy policy: How myopic is it? Politics and Governance, 9(3), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i3.4320

- Howlett, M. (2019). Procedural policy tools and the temporal dimensions of policy design. International Review of Public Policy, 1(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.4000/irpp.310

- Howlett, M., & Rayner, J. (2007). Design principles for policy mixes: Cohesion and coherence in ‘New Governance Arrangements’. Policy and Society, 26(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1449-4035(07)70118-2

- Huitema, D., Jordan, A., Munaretto, S., & Hildén, M. (2018). Policy experimentation: Core concepts, political dynamics, governance and impacts. Policy Sciences, 51(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9321-9

- IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policymakers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- IPCC. (2022a). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Summary for Policymakers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- IPCC. (2022b). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Summary for Policymakers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Jordan, A., Huitema, D., van Asselt, H., Rayner, T., & Berkhout, F. (2010). Climate Change Policy in the European Union: Confronting the Dilemmas of Mitigation and Adaptation? Cambridge University Press.

- Jordan, A., & Lenschow, A. (2010). Environmental policy integration: A state of the art review. Environmental Policy and Governance, 20(3), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.539

- Jordan, A., & Moore, B. (2020). Durable by Design? Policy Feedback in a Changing Climate. Cambridge University Press.

- Jordan, A., & Moore, B. (2022). The durability-flexibility dialectic: The evolution of decarbonisation policies in the European union. Journal of European Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2042721

- Knodt, M., & Schoenefeld, J. (2020). Harder soft governance in European climate and energy policy: Exploring a new trend in public policy. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(6), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1832885

- Kulovesi, K., & Oberthür, S. (2020). Assessing the EU’s 2030 Climate and Energy Policy Framework: Incremental change toward radical transformation? Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law, 29(2), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12358

- Lafferty, W. M., & Hovden, E. (2003). Environmental policy integration: Towards an analytical framework. Environmental Politics, 12(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010412331308254

- Leipprand, A., Flachsland, C., & Pahle, M. (2020). Starting low, reaching high? Sequencing in EU climate and energy policies. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 37, 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.08.006

- Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., & Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences, 45(2), 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0

- Neuhoff, K., & Lehne, J. (2020). How ‘green’ the EU recovery is depends on member states. 24 July 2020. Climate Home News. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2020/07/24/green-eu-recovery-depends-member-states/.

- Oberthür, S. (2019). Hard or soft governance? The EU’s Climate and Energy Policy Framework for 2030. Politics and Governance, 7(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i1.1796

- Oberthür, S., & Dupont, C. (2021). The European Union’s international climate leadership: Towards a grand climate strategy? Journal of European Public Policy, 28(7), 1095–1114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918218

- Oberthür, S., & Pallemaerts, M. (eds.). (2010). The New Climate Policies of the European Union: Internal Legislation and Climate Diplomacy. VUB Press.

- Och, M. (2020). Sustainable finance and the EU Taxonomy Regulation – Hype or Hope? Jan Ronse Institute for Company & Financial Law Working Paper No. 2020/05 (November 2020), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3738255.

- Pacheco-Vega, R. (2020). Environmental regulation, governance, and policy instruments, 20 years after the stick, carrot, and sermon typology. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 22(2), 1–16.

- Perlaviciute, G., Stega, L., & Sovacool, B. K. (2021). A perspective on the human dimensions of a transition to net-zero energy systems. Energy and Climate Change, 2, 100042–100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egycc.2021.100042

- Peters, G., & Tarpey, M. (2019). Are wicked problems really so wicked? Perceptions of policy problems. Policy and Society, 38(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2019.1626595

- Rietig, K. (2021). Accelerating low carbon transitions via budgetary processes? EU climate governance in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(7), 1018–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918217

- Rogge, K. S., Kerna, F., & Howlett, M. (2017). Conceptual and empirical advances in analysing policy mixes for energy transitions. Energy Research & Social Science, 33, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.025

- Rosenbloom, D., Meadowcroft, J., & Cashore, B. (2019). Stability and climate policy? Harnessing insights on path dependence, policy feedback, and transition pathways. Energy Research & Social Science, 50, 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.12.009

- Sabel, C. F., & Zeitlin, J. (2010). Experimentalist Governance in the European Union. Towards a New Architecture. Oxford University Press.

- Savaresi, A., Perugini, L., & Chiriacò, M. V. (2020). Making sense of the LULUCF regulation: Much ado about nothing? Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law, 29(2), 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12332

- Schaffrin, A., Sewerin, S., & Seubert, S. (2014). The innovativeness of national policy portfolios – climate policy change in Austria, Germany, and the UK. Environmental Politics, 23(5), 860–883. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.924206

- Schaffrin, A., Sewerin, S., & Seubert, S. (2015). Toward a comparative measure of climate policy output. Policy Studies Journal, 43(2), 257–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12095

- Schaub, S., Tosun, J., Jordan, A., & Enguer, J. (2022). Climate policy ambition: Exploring a policy density perspective. Politics and Governance, 10(3) (Forthcoming), https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v10i3.5347

- Schoenefeld, J. J. (2021). The European Green Deal: What prospects for governing climate change with policy monitoring? Politics and Governance, 9(3), 370–379. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i3.4306

- Skjærseth, J. B. (2021). Towards a European Green Deal: The evolution of EU climate and energy policy mixes. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 21(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-021-09529-4

- Skjærseth, J. B., Eikeland, P. O., Gulbrandsen, L. H., & Jevnaker, T. (2016). Linking EU Climate and Energy Policies: Decision-Making, Implementation and Reform. Edward Elgar.

- Skjærseth, J. B., & Wettestad, J. (2008). EU Emissions Trading: Initiation, Decision-Making and Implementation. Ashgate.

- Torney, D., & O’Gorman, R. (2020). Adaptability versus certainty in a carbon emissions reduction regime: An assessment of the EU’s 2030 Climate and Energy Policy Framework. Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law, 29(2), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12354

- von Homeyer, I., Oberthür, S., & Dupont, C. (2022). Implementing the European Green Deal during the evolving energy crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13397.

- von Homeyer, I., Oberthür, S., & Jordan, A. J. (2021). EU climate and energy governance in times of crisis: Towards a new agenda. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(7), 959–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918221

- Wurzel, R. K. W., Zito, A. R., & Jordan, A. J. (2013). Environmental governance in Europe: A comparative analysis of new environmental policy instruments. Edward Elgar.

- Wurzel, R. K. W., Zito, A., & Jordan, A. (2019). Smart (and not so smart) mixes of new environmental policy instruments. In J. van Erp, M. Faure, A. Nollkaemper, & N. Philipsen (Eds.), Smart Mixes for Transboundary Environmental Harm (pp. 69–94). Cambridge University Press.