ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to identify the most vaccine-hesitant groups in a contemporary democratic state, Sweden. We rely on two representative surveys that were conducted in 2020 and that asked Swedish citizens how likely they were to accept immunization with a Covid-19 vaccine if one were offered to them. Using clustering methods, we find a wide variety of vaccine-hesitant groups, with the highest levels of vaccine hesitancy among individuals who combine low personal health risks with political orientations and ideological convictions that are associated with antivaccinationist attitudes. The paper's findings have important implications for public-health policy and, more broadly, for theories of how governments can convince individual citizens to play their part in achieving important social goals.

Many people are reluctant to get vaccinated, or let their children be vaccinated, against communicable diseases. This widespread vaccine hesitancy has important consequences for public-health policy and public health. In this paper, we use clustering methods to identify the most vaccine-hesitant groups in a contemporary democratic state, Sweden. We then discuss the implications of our empirical findings for public-health policy and explain how the methods we use can improve scholarship on vaccine hesitancy and public policy.

There is a large and growing literature on vaccine hesitancy, which is a ‘delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services’ (MacDonald, Citation2015). Numerous empirical studies, especially in the public-health field, have sought to identify the demographic, social, psychological, and political factors that contribute to vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccine attitudes. Nevertheless, vaccine hesitancy remains an elusive phenomenon—there seem to be many different groups of citizens who are vaccine-hesitant, with different motives for their hesitancy.

This paper takes a different empirical approach than most other quantitative studies of vaccine hesitancy. It is based on two representative surveys that were conducted in Sweden in 2020 and that asked Swedes aged 16–85 to indicate how likely they were to agree to be vaccinated with a Covid-19 vaccine if one were offered to them. Instead of conducting multivariate regression analyses that jointly estimate the partial correlations between vaccine hesitancy and potential explanatory variables—as many other studies do—we follow a two-step procedure that is common in data analysis and that is especially useful for analyzing the prevalence of different types of individuals in the population. We begin by using cluster-analysis methods to identify distinct groups of citizens who resemble each other on a combination of variables that are likely to be associated with attitudes to vaccinations; we then use the results from the cluster analysis to examine the differences in vaccine hesitancy between the groups.

We find some vaccine-hesitant groups that have certain political views in common: they have little faith in Sweden’s democratic system, vote for the radical-right-populist Sweden Democrats, or both. We also find groups whose vaccine hesitancy is associated with low levels of inter-personal trust. Moreover, we find groups in which a combination of political attitudes, personal health risks, and media-consumption habits seems to explain vaccine hesitancy. We also note, however, that the largest group of vaccine-hesitant individuals appear to be reluctant to take the vaccine for the simple reason that they are young and therefore run a low risk of serious illness. In this group, politics does not play a major role.

These findings have important implications for public-health policy since they suggest that no single policy instrument can increase vaccine uptake across the board; many different policy instruments are likely to be required. The findings also have important implications for broader questions about the ability of modern democratic states to convince citizens to join in a collective effort to achieve important social goals.

Vaccination as an example of co-production

There are many policy areas in which governments can only achieve their goals if they convince citizens to make changes in their own lives (Alford, Citation2009; Ostrom, Citation1990, Citation1996). As Alford (Citation2009, p. 2) puts it, ‘the realization of some of the purposes of providing [a] public service’ is often ‘partly performed by the client.’ The health-care system is one example given by Alford since it depends on citizens to exercise and eat healthily. Recycling is another example since it depends on citizens to separate out different types of garbage and place them in different containers.

As Alford (Citation2009) notes, a key question for scholarship is ‘[w]hat induces clients to contribute their time and effort’ when they’re asked to do so (Steen, Citation2021 provides a recent overview of the literature on this topic). The goal of our paper is to address this important question on the basis of an empirical study of vaccination policy. By describing the most vaccine-hesitant groups in a contemporary democratic country, our paper identifies some of the main challenges for public-service delivery in the public-health field.

As the Covid-19 pandemic has shown, with its inherent complexity, uncertainty, and high impact on society, the transmission of communicable diseases is a ‘wicked problem’ (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973). Wicked problems are ‘not amenable to top-down general solutions’ (Head & Alford, Citation2015), and the public sector cannot produce an effective and legitimate response without the voluntary and active participation of citizens. While many countries have managed to reach vaccination-coverage rates of up to 90 percent of the adult population, the ‘wickedness’ of vaccinations against Covid19 is manifested by the fact that even this high level of uptake was not enough to halt the transmission of the most contagious strands of the virus.

The enforcement of strict regulations to halt disease transmission, such as curfews and lockdowns, comes with both known and unknown political and social costs. What is more, many social services that are vital to the societal response to a pandemic simply cannot be regulated and governed in a coercive, top-down manner. Informal care, mutual self-help among neighbors, and volunteering are examples of how citizens co-produce public goods and services that are necessary for a socially and economically sustainable pandemic response. During the Covid-19 pandemic, scholars have observed widespread coproduction of important public services (Steen & Brandsen, Citation2020) and the pandemic is expected to result in a greater emphasis on co-production in health-care provision in the future (Turk et al., Citation2021).

To our knowledge, vaccination has not previously been discussed as an example of co-production in the literature on public administration and public policy. But vaccination is a quintessential example of how the effective delivery of public services requires cooperation between public authorities and citizens: public bureaucracies can finance and deliver the vaccine and provide incentives to promote vaccine uptake, but a successful vaccination program requires a massive mobilization of citizens who are willing to contribute to herd immunity by getting vaccinated.

The main political question, then, is how to convince people outside the primary risk groups to contribute to the protection of the whole population. As the history of vaccinations teaches us, this is no mean task. The world’s first vaccine, against smallpox, was discovered in England in the late 1790s. Within two decades, most countries in Western Europe had put in place some form of vaccination program; a few countries, including Sweden and its neighbor Denmark, even made smallpox vaccinations compulsory (Ansell & Lindvall, Citation2021, Chapter 8). But it was also a policy that immediately became controversial, and it has remained controversial into our own time. For as long as there have been vaccines, there has been vaccine hesitancy.

By learning about the main challenges for public-service delivery when it comes to vaccinations, we can learn more about the challenges for public-service delivery in the public-health field and beyond.

Vaccine hesitancy: A segmentation approach

Vaccine hesitancy is the result of a complex decision-making process that is influenced by numerous contextual and individual-level factors. Scholars have sought to organize those factors in coherent conceptual models, of which the ‘3 Cs’ model is the most well-known. In the 3 Cs model, vaccine hesitancy is a function of complacency, convenience, and confidence. Complacency is the unwillingness of those who do not believe they are at risk to take preventive measures against infection. Convenience is the accessibility of a vaccine in terms of costs, physical distance, and information availability. Confidence, finally, is about trust in the vaccine, the provider of the vaccine, and the political decision-makers (MacDonald, Citation2015).

The objective of this section is to identify explanatory factors that are likely to be associated with vaccine hesitancy.

We consider five types of variables, which are linked to complacency, convenience, or confidence: (a) individual-level risk factors, (b) socioeconomic and demographic background variables, (c) information and knowledge, (d) confidence in political institutions and trust in other people, and (e) political ideology.

Beginning with individual-level risk factors, several studies of vaccine uptake and vaccine hesitancy have found the willingness to vaccinate to be greater among members of risk groups for whom immunization has been recommended (Rodríguez-Rieiro et al., Citation2010). Higher vaccination willingness has also been found among people with chronic medical conditions (Gaygısız et al., Citation2017) and a higher perceived risk of becoming infected or seriously ill (Rubin et al., Citation2009). Several studies have also found a link between vaccine hesitancy and the perceived risk of side effects (Lau et al., Citation2009). The work that already exists on attitudes to the Covid-19 vaccine suggests that risk factors for severe Covid-19 infection are associated with a greater willingness to vaccinate (Head et al., Citation2020). Those who are less worried about the consequences of contracting Covid-19 have also been found to be less willing to vaccinate (Schwarzinger et al., Citation2020).

Vaccine hesitancy has also been linked to various socioeconomic and demographic factors. For example, in the (A)H1N1 pandemic of 2009, there was more vaccine hesitancy among the less well-educated and among young females who belonged to ethnic minorities than among other groups (Velan et al., Citation2011). During the Covid-19 pandemic, vaccine coverage has been comparatively low among members of ethnic minorities (Khubchandani et al., Citation2021) and among people living in areas with higher levels of economic deprivation (MacKenna et al., Citation2021). Moreover, vaccine hesitancy has been linked to low education and female gender in the Covid-19 epidemic, just as in the (A)H1N1 epidemic a decade earlier (Schwarzinger et al., Citation2020).

Another long-standing theme in empirical research on vaccine hesitancy and antivaccinationism is information. In the nineteenth century, antivaccinationist ideas were disseminated via leaflets and pamphlets. Today, similar ideas spread easily via the internet (Attwell et al., Citation2021; Puri et al., Citation2020). Several studies on Covid-19 vaccinations highlight the role of information. Loomba et al. (Citation2021) found that exposure to online misinformation around Covid-19 had a negative effect on the willingness to vaccinate. Another study found higher hesitancy among people who rely on unmonitored media platforms (Ebrahimi et al., Citation2021). Using a latent-class-analysis approach, Tan et al. (Citation2022) found that trust in formal sources of information is linked to Covid-19 vaccine status.

Several studies also point to the relevance of trust in political institutions, politicians, and other people. For example, Velan et al. (Citation2011) show that distrust in the government is associated with low vaccine uptake. Prati et al. (Citation2011) make the same observation in Italy. Similarly, Rönnerstrand (Citation2013) finds that trust in health care and trust in other people are associated with a greater willingness to vaccinate in Sweden. During the Covid-19 pandemic, a global survey found that high trust in government was associated with positive attitudes to the Covid vaccine (Lazarus et al., Citation2020). Many studies have confirmed this finding in relation to trust in different institutions and groups such as health care professionals (Szilagyi et al., Citation2021), decision-makers (Prati, Citation2020), and scientists (Sturgis et al., Citation2021). There are also studies that find a positive correlation between social trust and vaccination willingness (Sekizawa et al., Citation2022).

Mesch and Schwirian (Citation2015) analyze the role of political attitudes and find a greater willingness to vaccinate among Democrats and people with liberal views in the United States. A recent study of Covid-19 by Latkin et al. (Citation2021) also highlights the role of political ideology: they report that people with conservative beliefs tend to have less faith in the vaccine. Several other studies from the same period have found lower vaccine intent among people with conservative political beliefs (Reiter et al., Citation2020). Based on the results from a study of the uptake of and attitudes toward the smallpox, MMR, and A(H1N1) vaccines, however, Krupenkin (Citation2021) argues that vaccination hesitancy is associated with support for the party not currently in office, not any one ideological orientation. The well-documented political divide in attitudes towards Covid-19 vaccinations in the United States (Attwell et al., Citation2021; Killgore et al., Citation2021; Milligan et al., Citation2021; Ruiz & Bell, Citation2021) has had serious public health consequences. Albrecht (Citation2022) note that vaccine uptake is lower and Covid-19-related death rates are higher in US counties with a higher share of Republican voters. Results from a survey in France demonstrate that Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy has political underpinnings also in the European context; the authors found prospective willingness to vaccinate against Covid-19 to be lower among both far-left and far-right supporters (Ward et al., Citation2020).

What are we to make of this array of findings? As our literature review has demonstrated, many studies have sought to identify explanatory factors that are associated with vaccine hesitancy, typically using multivariate regression methods. Although such studies are useful for identifying and quantifying the relationship between individual variables and attitudes, there are two downsides with this approach. First, the explanatory variables we have discussed in this section are likely to be associated with each other in complicated ways, and without a strong theory of the origins of vaccine hesitancy, those interdependencies are very difficult to analyze using standard methods. Second, although the independent effects of individual explanatory variables are relevant to consider, that is only the beginning of the discussion—both from a public-health perspective and from a broader political perspective, the ultimate question is how vaccine hesitancy emerges in different social groups.

What is needed, therefore, is an approach to studying vaccine hesitancy that improves our understanding of the types of citizens that are vaccine-hesitant: groups that may well combine many of the individual characteristics on which existing work has concentrated. If it is possible to identify particular groups that are especially vaccine-hesitant, it may be possible to devise targeted policy interventions that are adapted to the distinct forms of hesitancy that are prevalent in the population. This sort of holistic approach is more common in qualitative work on vaccine hesitancy than in quantitative work (one recent example being Larson, Citation2020). In this paper, we rely on a survey-based quantitative approach, but we take inspiration from this line of qualitative research—and from research on consumer segmentation, in which scholars investigate differences and similarities between clusters in the population.

In the public-health field, cluster-based analyses have been used to identify segments of the population characterized by different kinds of health-related behaviors (Engl et al., Citation2019), but despite the advantages of such methods for the problem at hand, segmentation techniques have rarely been used to identify vaccine-hesitant groups (Vulpe & Rughiniş, Citation2021). There are a few exceptions, however, including one study of segments of vaccine hesitance in relation to the A(H1N1) virus in the United States (Ramanadhan et al., Citation2015), one study of attitudes to childhood vaccination among groups of parents (also in the United States) (Gust et al., Citation2005; Keane et al., Citation2005), and one study of beliefs about vaccine risks and vaccine hesitancy in European countries (Recio-Román et al., Citation2021; Vulpe & Rughiniş, Citation2021). In the case of Covid-19, the only example we are aware of is a report on clusters of vaccine-hesitant groups in the United States that was released by the non-profit organization Surgo Ventures (Citation2021). With the help of a k-medoid clustering algorithm, Surgo Ventures identified four hesitant clusters: the ‘Watchful,’ the ‘Cost-Anxious,’ the ‘System Distrusters’ and the ‘Covid Skeptics.’

What our paper adds to previous work on the composition of vaccine-hesitant groups is that it pays particularly close attention to the role of political explanatory factors and to how political factors combine with other background variables.

Data, design, and methods

The quality of empirical analyses that rely on clustering methods depends greatly on the number of observations. To avoid suboptimal clustering solutions, a ratio of approximately 70–100 observations per variable in the segmentation base is often recommended (Dolnicar et al., Citation2016). To improve the precision of our estimates of vaccine hesitancy within relatively small population segments, we have opted for including as many observations as possible in the analysis. The dataset we rely on in this paper therefore combines observations from two nationally representative Swedish cross-section postal-survey questionnaires that were administered by the SOM Institute at the University of Gothenburg.

The two surveys were identical in terms of sample characteristics (people residing in Sweden in the ages 16–85) and similar in terms of the relevant survey items. The Corona SOM Survey was fielded between April 14 and June 28, 2020. The AAPOR5 response rate was 42 percent. The number of respondents who answered the question about Covid-19-vaccination intent was 2514. This survey concentrated on questions regarding the pandemic, but it also contained questions about broader societal and political issues as well as the demographic and socioeconomic background of the respondents. The regular National SOM Survey was fielded in the autumn of the same year, between September 14 and December 21. The AAPOR5 response rate was 49 percent and the number of respondents who answered the question about Covid-19 vaccination intent was 3628.

The interval between the two surveys is a slight concern since the infection rate and the nature of the epidemic changed during 2020, but crucially, all surveys were completed before Sweden’s first vaccinations against Covid-19 were carried out on December 27 that year. In other words, all respondents answered a prospective question about their willingness to receive a vaccine against Covid-19 if one were offered to them. This means that the question taps into more general attitudes to vaccination, as opposed to concerns about the specific vaccine that was eventually developed for Covid-19. But it also comes with problems. One limitation is that the level of vaccine hesitancy in the segments we describe might have changed during the vaccine campaign because of fluctuations in disease transmission, new variants of the virus emerging, or observations of vaccine uptake in different groups. Risk-related factors are likely to be especially sensitive such changes. For example, low-trust groups with low hesitancy due to risk factors might change their mind once a milder version of the virus starts to circulate.

The field work was carried out in a similar but not identical manner in the two surveys. The field period was shorter and the number of respondents fewer in the Corona SOM Survey, as compared with the National SOM Survey. Another difference was that respondents who participated in the National SOM Survey were given a lottery ticket. No such incentives were used in the Corona SOM Survey. For both the Corona SOM Survey and the National SOM Survey, men and younger people participated slightly less than women and the elderly. However, there were no significant differences between the survey respondents and Sweden’s general population in their geographical distribution across the country.

The first step in our analysis is to use a clustering algorithm to identify distinct groups in the Swedish population from observations on a wide range of variables that are likely to be associated with attitudes to vaccinations. The second step is to use the resulting clustering solution to create group dummies that can be used as right-hand-side explanatory variables in a regression analysis of the variation in vaccine hesitancy among the surveyed respondents. The outcome variable in the second part of the analysis is based on the survey question ‘How likely is it that you will vaccinate yourself against the coronavirus if given the opportunity?’ The response alternatives were ‘very likely,’ ‘somewhat likely,’ ‘neither likely nor unlikely,’ ‘somewhat unlikely,’ and ‘very unlikely.’

We use two different operational definitions of the outcome variable, vaccine hesitancy. We define hesitancy as being neither ‘very’ nor ‘somewhat’ likely to vaccinate, to get a broad group of vaccine-hesitant individuals that includes those who do not define themselves as ‘unlikely’ to vaccinate. Second, we concentrate on respondents that responded they are ‘very unlikely’ to vaccinate. The reason for this dual measurement approach is that we consider it likely that vaccine-hesitant clusters differ in the intensity of their hesitancy. For example, there may be clusters with many weakly hesitant respondents but few die-hard vaccine skeptics. Due to space constraints, the results from the analysis of strong hesitancy are presented in the Online Appendix.

At the cluster-analysis stage, we follow the earlier literature by including variables from the five categories we discussed in the previous section. For detailed variable definitions and discussion, see the Online Appendix.

Vaccine hesitancy in Sweden

The first part of our analysis relies on hierarchical clustering methods. There are two important advantages of hierarchical methods for our purposes. First, unlike other commonly used methods such as k-means clustering, hierarchical methods do not require the researcher to specify the number of clusters beforehand, which is an advantage in our case since we have no strong prior expectations about the number of clusters. Second, using hierarchical cluster-analysis methods allows us to use a dissimilarity measure, proposed by Gower (Citation1971), that is appropriate for datasets with both continuous and binary variables, such as ours. The specific type of hierarchical cluster analysis that we have chosen is commonly known as the ‘average-linkage’ method; it is best thought of as a compromise between the ‘single-linkage’ and ‘complete-linkage’ methods (both of which have important advantages but also important disadvantages).

There are different criteria that can be used to determine the optimal number of clusters after a hierarchical cluster analysis. In our preferred model, the Duda score and the Calinski/Harabasz pseudo-F score suggest a 16-cluster solution. Among the 16 clusters, we will only pay attention to 10, however, since six of the clusters are very small (18, 11, 9, 9, 6, and 4 observations). describes the composition of the ten main clusters. As will become clear later, for clarity of exposition, we have sorted the clusters from low to high vaccine hesitancy. The numbers in the table are the mean values of the explanatory variables within each cluster. The last row contains the means for the entire sample, allowing for simple comparisons that reveal how the average member of each cluster differs from the average respondent in the survey.

Table 1. The Ten Main Clusters.

Cluster 1, which we call older, high-trust, is made up of people aged 70 and older who consume quality news, have higher-than-average levels of social trust and faith in democracy, are slightly left-of-center, and do not vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Clusters 2 and 3, like Cluster 1, are made up of older individuals. We label these two clusters low-trust older women and low-trust older men since the most significant difference between these clusters and Cluster 1 is the low faith in democracy among the respondents (98 and 78 percent, as opposed to 4 percent in Cluster 1) and their low trust in other people (on average 5.8). The respondents in Clusters 2 and 3 also have slightly worse self-reported health than Cluster 1, and they are on the right, although the women in Cluster 2 are less likely than the men in Cluster 3 to support the Sweden Democrats. It is interesting to note that the respondents in Clusters 2 and 3 consume regular news media almost as much as the respondents in Cluster 1. As makes clear, media use is highly correlated with age, with younger respondents being much less likely to consume quality news (probably reflecting their higher use of social media and online news).

The respondents in Cluster 4 (working-age, high trust) are healthy, well-educated people aged 36–69 with high levels of social trust and high faith in democracy. Politically, they are close to the middle of the left-right scale, and they do not vote for the Sweden Democrats. Their level of quality media consumption is on par with the average of the sample. In other words, we can think of Cluster 4 as a slightly younger version of Cluster 1, with slightly higher education, more city dwellers, slightly better health, and a slightly different media diet.

Both Cluster 5 and Cluster 7 are made up of people born outside Europe. But the two groups are nevertheless quite different from each other. The respondents in Cluster 7, which we call working-age, female immigrants, have a high level of education, and most of them are women. They live in large cities, are somewhat less satisfied with how Swedish democracy works than the average respondent and have relatively low levels of social trust. They score low on quality-news consumption. Many of them are religious, and they are slightly left of center. The respondents in Cluster 5, which we call the religious, low-trust immigrants, have the highest level of religiosity, the lowest level of education, the lowest self-rated health score, and the lowest level of social trust among all the clusters. In contrast, their faith in democracy is on par with the average respondent. Most of them are men.

Cluster 6, which we call urban youth, are young and in good health and put faith in democracy. Their level of social trust, however, is somewhat lower than that of the average respondent. People in this cluster lean to the left politically and do not vote for the Sweden Democrats. What stands out among the respondents in Cluster 6—apart from their youth and their health—is their media diet: they rarely read morning newspapers and do not watch the big TV news programs.

Clusters 8 and 10, which we call rural, female SD and working-age, male SD, are made up of respondents who all vote for the Sweden Democrats and who have, on average, a right-leaning political ideology. Both groups also have low levels of education. But the two groups still differ in several interesting ways. Cluster 8 are women who live outside large cities and who have a lot of faith in democracy. Their social trust is below average. But it is still higher than among the respondents in Cluster 10, who have the second-lowest level of social trust out of all the clusters. The respondents in Cluster 10 also lack faith in democracy, and they are much less likely to consume quality news than the respondents in Cluster 8, whose quality-news consumption is higher than the average respondent’s.

Like the respondents in Clusters 8 and 10, the respondents in Cluster 9—the rural, low-educated with low faith in democracy—stand to the right politically. They also resemble the respondents in Cluster 10 in that they have low faith in democracy and do not consume much quality news. But they differ from the respondents in Cluster 10 in three important ways. They are in slightly worse health. Their level of education is even lower (the lowest out of all the clusters). And they do not vote for the Sweden Democrats.

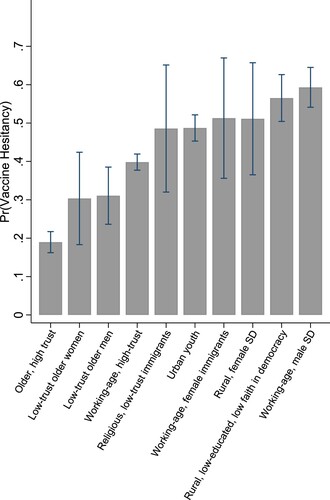

We are now ready for the final stage of the analysis, where we examine the level of vaccine hesitancy in each group in . To do so, we run a simple logit analysis with vaccine hesitancy as the outcome variable and the full set of cluster dummies as explanatory variables; we then calculate the predicted likelihood of vaccine hesitancy for each cluster. summarizes the predicted probabilities of vaccine hesitancy that we derive from our analysis of this outcome variable. The bars represent predicted probabilities; the thin lines represent 95-percent confidence intervals around those probabilities.

As shows, the level of vaccine hesitancy is lowest in Cluster 1 (n = 780), which is the group that consists of older Swedes with a lot of faith in democracy and trust in other people. The proportion of vaccine-hesitant respondents in this group—19 percent—is significantly lower than the average hesitancy in the whole sample, which is 40 percent (using our first, broad definition of vaccine hesitancy).

Clusters 2 (n = 54) and 3 (n = 148) consist of people who face a fairly high risk of severe Covid-19 illness: older people in rather poor health. But unlike the respondents in Cluster 1, the respondents in Clusters 2 and 3 lack faith in democracy and tend to distrust other people. Both these groups have a level of hesitancy of about 30 percent. For the larger of the two clusters—the men—this is significantly higher than the level of vaccine hesitancy in Cluster 1. As we will see later, a lack of faith in the democratic system and low levels of trust in other people are factors that tend to be associated with high vaccine hesitancy. The fact that vaccine hesitancy is nevertheless relatively low in Clusters 2 and 3 is likely a result of the countervailing effect of personal health-risk factors and perhaps more consumption of quality news sources.

The average level of hesitancy in the very large Cluster 4 (n = 2084), about 40 percent, is twice as high as the average level in Cluster 1. This group of working-age people are thus on par with the sample average when it comes to vaccine hesitancy, despite being a group characterized by very high trust and faith in democracy. Again, the findings suggest it is important to consider the interaction of political orientations and beliefs and personal risk factors.

Clusters 5 and 7 are made up of immigrants born outside Europe. Both these groups are relatively small (n = 35 and n = 39), which explains the large confidence intervals around the estimated probability of hesitancy in these groups. In both clusters, we find a level of vaccine hesitancy that is approximately 10 percentage points higher than the sample average, but there is a lot of uncertainty around those estimates. It is important to keep in mind that people born outside Sweden are under-sampled in the SOM surveys: in our sample, approximately 3 percent of the respondents were born outside of Europe, which is less than a third of the proportion of foreign-born outside Europe in the Swedish population. It is likely that those who responded to the survey are less vaccine-hesitant than those who did not, so our findings probably underestimate the level of vaccine hesitancy among immigrants from outside Europe. Considering the differences in the composition of the two immigrant groups, it is somewhat surprising that their levels of hesitancy are rather similar. They differ in terms of education (low in Cluster 5, high in Cluster 7), place of residence (outside large cities versus in large cities) and gender composition (predominantly male versus predominantly female).

Respondents who end up in Cluster 6 (n = 821) are all young, and they reside in cities more often than the average respondent. Moreover, they do not consume high-quality media (they do not read morning newspapers and do not watch the main TV news programming). Perhaps because of their young age and their different media habits, the hesitancy in this group (49 percent) is significantly higher than the sample mean.

The respondents in Clusters 8 (n = 45) and 10 (n = 344), among whom we find right-wing supporters of the Sweden Democrats, are more vaccine-hesitant than the average for the population, but only significantly so for the larger of the two clusters. The highest proportion of vaccine-hesitant respondents (59 percent) is found in Cluster 10. This group consists of men with low faith in democracy and very low levels of social trust. Interestingly, the respondents in Cluster 8 have high faith in democracy, but they are nevertheless likely to be vaccine-hesitant (51 percent). This is a small group, however, so we cannot be confident in the comparisons.

Finally, almost all the predominantly male members of Cluster 9 have low education, live outside larger cities, and lack faith in democracy. One important difference between Cluster 9 and Clusters 8 and 10 is worth noting: the respondents in Cluster 9 do not support the Sweden Democrats. Vaccine hesitancy is still high in this group, at 57 percent. It seems unlikely that the common explanation for the high level of hesitancy in Clusters 9 and 10 is ideological beliefs associated with voting for the populist radical right. As in Cluster 3, the explanation is more likely their exceptionally low level of faith in Sweden’s democratic system—which is not counteracted by the effect of personal risk factors.

Discussion and conclusions

As the analyses in the preceding section have demonstrated, there are several different types of vaccine-hesitant individuals in the Swedish population.

The variation in vaccine hesitancy among older respondents is associated with political divisions. We found three clusters of individuals aged 70–85, with two of them being more vaccine-hesitant. This difference is likely not a result of differences in personal risks, for the mean age in all three clusters is 75 and self-rated health is lower, not higher, in the two high-hesitancy clusters. Instead, the respondents in Cluster 2 and 3 both differ from Cluster 1 in their lack of faith in democracy and their low trust in other people. They are also on the right politically. Since vaccine hesitancy in Clusters 2 and 3 appears to be motivated by political beliefs and attitudes, it is difficult to tell what policy measures might increase vaccine uptake in those groups. The respondents in Clusters 2 and 3 are likely aware that they run a high risk of severe Covid-19, so information campaigns are not going to be effective. Nor are travel restrictions or monetary incentives (Largent & Miller, Citation2021).

The relatively high level of hesitancy in Cluster 4 is somewhat peculiar. Why is this group of working-age, well-educated Swedes with high faith in democracy and high levels of social trust not more willing to get vaccinated? Individual risk factors are likely to play a role. Members of this group are all younger than 70 and their self-rated health is high. Another factor could be media use: respondents in Cluster 4 tend to rely less on quality news media than the older respondents in Clusters 1–3. This group is likely to be responsive to policy interventions such as monetary benefits (Savulescu, Citation2021) and rules that make vaccination a requirement for international travel (Dye & Mills, Citation2021). It is also likely to be responsive to communications that highlight the other-regarding benefits of vaccinations since the respondents in Cluster 4 have high social trust (Rönnerstrand, Citation2015).

Now, let us consider the young respondents in Cluster 6, who stand out in two important ways: their youth makes them much less likely to become seriously ill and they consume different sorts of media than the older Swedes in the first four clusters. Since these two variables are highly correlated, it is difficult to separate them, but it seems likely that both help to explain why the level of hesitancy in Cluster 6 is higher than in Cluster 4 (and, of course, Cluster 2). Just like the respondents in Cluster 4, the respondents in Cluster 6 are likely to be responsive to incentives and information.

The next category of relatively vaccine-hesitant respondents is immigrants from outside Europe, who cluster in two groups: the low-educated and religious immigrants in Cluster 5 and the well-educated immigrants in Cluster 7. If the vaccine hesitancy in these groups is a result of the outsiderness that comes with being an immigrant, financial or other incentives are unlikely to increase vaccine uptake much; the availability of information about vaccines in different languages and the use of communication channels that reach into the immigrant communities are likely to matter more (Razai et al., Citation2021).

We find two different groups (8 and 10) that stand out because of the high level of support for the Sweden Democrats. Both groups have high levels of hesitancy; in fact, Cluster 10 has the highest level of hesitancy out of all clusters (59 percent). It is likely to be especially difficult to promote vaccination in Cluster 10. Many of the individuals in this group are intensely vaccine-hesitant, and their lack of social trust and low faith in democracy likely makes them less susceptible to communications concerning the other-regarding or societal consequences of vaccine refusal.

Finally, the respondents in Cluster 9 have a high level of hesitancy, at 57 percent. They have low education, low faith in democracy, and low social trust. Politically, they are on the right, but they do not support the Sweden Democrats. They also lack risk factors for severe Covid-19 infection: most of them are young or working-age. The existence of this group serves as a reminder that politically motivated mistrust is not isolated among the supporters of Sweden’s radical-right party. These individuals are unlikely to respond to financial or other incentives. Personal communications with trusted health-care professionals may be the best way to lower hesitancy among respondents in Cluster 9 (Warren & Lofstedt, Citation2021).

Low compliance among those who are motivated by ideological beliefs is likely to be a more intractable problem than low compliance in other groups. The respondents in Clusters 8–10 either have low faith in democracy, distinct ideological orientations, or both. Those are deep causes of low compliance with public-health policies that are likely the result of long-term processes of political disaffection.

The results from the segmentation analysis have important implications for the literature on the relationship between social trust and vaccine hesitancy. The finding that the group with the lowest level of hesitancy (Cluster 1) is characterized by high trust in other people is in line with results demonstrating a negative relationship between social trust and vaccine hesitancy in relation both to 2009 (A)H1N1 vaccinations (Rönnerstrand, Citation2013) and Covid-19 vaccinations (Ahorsu et al., Citation2022; Sekizawa et al., Citation2022).

Horizontal trust—social trust in other people—is different from vertical trust in institutions, politicians, and officials. The latter kind of trust is directly related to ‘confidence’ in the ‘3Cs’ model, and it is fundamental since vaccine acceptance requires that people trust a vaccine to be safe and to provide effective protection against the disease (Larson, Citation2018). But most people are not themselves capable of assessing the safety and effectiveness of a vaccine. Instead, they use trust in the provider of the vaccine as an information shortcut. Trusting the provider, they infer that they can trust the vaccine (Larson, Citation2018). Social trust in other people operates through other mechanisms. People are often motivated by the other-regarding consequences of vaccinations against transferable diseases, and social trust may trigger prosocial motivations, which is one of the mechanisms that link social trust to vaccine acceptance (Rönnerstrand, Citation2015). This is one way of interpreting the relatively low levels of hesitancy found in Cluster 4, which consists of individuals with high social trust but with low risk of severe Covid-19 infection in terms of their age and health status.

However, the main contribution of this paper to the literature on the relationship between trust and vaccine hesitancy is the finding that in several groups, low hesitancy goes hand in hand with low trust. Cluster 2 and 3 are characterized by low levels of social trust, but also rank low in hesitancy. One likely explanation is that these clusters consist of risk groups in terms of age and self-rated health. This suggests that the social trust factor may be deactivated by risk-related factors, which is not something that is already established in the trust-and-vaccine-hesitancy literature. Few studies empirically test hypotheses about the interaction between trust and risk factors. This is one way of understanding why not all studies find that social trust is linked to vaccine acceptance (Edwards et al., Citation2021; Jennings et al., Citation2021; Kerr et al., Citation2021).

There are also signs in our data that personal risks deactivate the other political factors that otherwise contribute to vaccine hesitancy. Two of the clusters where hesitancy is among the highest consist solely of supporters of the Sweden Democrats (Cluster 8 and 10), but the level of hesitancy is much lower among the older male Sweden Democrats found in Cluster 3.

As these examples show, the cluster-analysis methods we rely on in this paper generate new findings that were not previously established in the literature and that help put earlier findings in new light.

What are the general conclusions that can be drawn from the results reported in this paper? There are some aspects of the composition of vaccine-hesitant groups that are specific to Sweden’s social and political landscape. For example, while resistance to vaccines is a phenomenon that is common among supporters of radical-right parties in many other European countries, the observations we make concerning the Sweden Democrats and their supporters may not be directly transferable to radical-right parties elsewhere. Sweden also stands out in terms of certain variables that are used in the segmentation analysis—one example being comparatively high levels of social trust.

Moreover, generalizing the findings to other kinds of vaccines must be done with caution, if it is even possible. There are obvious differences between childhood vaccines and pandemic vaccines in terms of the development and approval process (slow v. fast) and the target groups (children v. the total population/adults). Empirically, the categories that are used in the cluster analysis are based on the literature on pandemic vaccination and include factors that are irrelevant for parents’ hesitancy about vaccinating their children—such as facing a high risk of severe Covid-19 infection. We would encourage future research to use a segmentation approach to better understand vaccine hesitancy among parents, as we have tried to do for pandemic vaccinations in this paper.

But many of the findings do have relevance across space and time. The basic finding that vaccine hesitancy can be found in many different segments of the population is likely not a unique feature of the context of our study, and the findings reported in this paper can therefore be used to develop and test hypotheses about the composition of vaccine-hesitant groups in other contexts. As mentioned above, the observation that low trust matters less to vaccine hesitancy when individual risk factors are present is something that is likely to be generalizable across space, and it is thus worth testing in other settings.

Replication materials

The data used in this article can be accessed via the Swedish National Data Service (SND). To access the data, see the Corona SOM survey 2020 (https://snd.gu.se/en/catalogue/study/2020-72) and the National SOM survey 2020 (https://snd.gu.se/en/catalogue/study/2021-21). A Stata do-file with all the code necessary to replicate the results reported in the article can be accessed via the Taylor & Francis website, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2123024.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (193.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Thomas Brambor, seminar participants at the University of Gothenburg, the editor of Journal of European Public Policy, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johannes Lindvall

Johannes Lindvall is a professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg.

Björn Rönnerstrand

Björn Rönnerstrand is a researcher in political science at the SOM Institute, University of Gothenburg.

References

- Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C. Y., Yahaghai, R., Alimoradi, Z., Broström, A., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2022). The mediational role of trust in the healthcare system in the association between generalized trust and willingness to get COVID-19 vaccination in Iran. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1993689

- Albrecht, D. (2022). Vaccination, politics and COVID-19 impacts. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12432-x

- Alford, J. (2009). Engaging Public Sector Clients: From Service-Delivery to Co-Production. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ansell, B. W., & Lindvall, J. (2021). Inward Conquest: The Political Origins of Modern Public Services. Cambridge University Press.

- Attwell, K., Betsch, C., Dubé, E., Sivelä, J., Gagneur, A., Suggs, L. S., Picot, V., & Thomson, A. (2021). Increasing vaccine acceptance using evidence-based approaches and policies: Insights from research on behavioural and social determinants presented at the 7th annual vaccine acceptance meeting. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 105, 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.007

- Dolnicar, S., Grün, B., & Leisch, F. (2016). Increasing sample size compensates for data problems in segmentation studies. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 992–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.09.004

- Dye, C., & Mills, M. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccination passports. Science, 371(6535), 1184–1184. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi5245

- Ebrahimi, O. V., Johnson, M. S., Ebling, S., Amundsen, O. M., Halsøy, Ø, Hoffart, A., Skjerdingstad, N., & Johnson, S. U. (2021). Risk, trust, and flawed assumptions: Vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.700213

- Edwards, B., Biddle, N., Gray, M., & Sollis, K. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: Correlates in a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the Australian population. PloS One, 16(3), e0248892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248892.

- Engl, E., Smittenaar, P., & Sgaier, S. (2019). Identifying population segments for effective intervention design and targeting using unsupervised machine learning: An end-to-end guide. Gates Open Research, 3, 1503. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.13029.2

- Gaygısız, U., Lajunen, T. and Gaygısız, E. (2017). Socio-economic factors, cultural values, national personality and antibiotics use: A cross-cultural study among European countries. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 10(6), 755–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2016.11.011

- Gower, J. C. (1971). A general coefficient of similarity and some of Its properties. Biometrics, 27(4), 857–871. https://doi.org/10.2307/2528823

- Gust, D., Brown, C., Sheedy, K., Hibbs, B., Weaver, D., & Nowak, G. (2005). Immunization attitudes and beliefs among parents: Beyond a dichotomous perspective. American Journal of Health Behavior, 29(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.29.1.7

- Head, B. W., & Alford, J. (2015). Wicked problems. Administration & Society, 47(6), 711–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399713481601

- Head, K. J., Kasting, M. L., Sturm, L. A., Hartsock, J. A., & Zimet, G. D. (2020). A national survey assessing SARS-CoV-2 vaccination intentions: Implications for future public health communication efforts. Science Communication, 42(5), 698–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547020960463

- Jennings, W., Stoker, G., Bunting, H., Valgarðsson, V. O., Gaskell, J., Devine, D., McKay, L., & Mills, M. C. (2021). Lack of trust, conspiracy beliefs, and social media use predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines, 9(1), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9060593

- Keane, M. T., Walter, M. V., Patel, B. I., Moorthy, S., Stevens, R. B., Bradley, K. M., Buford, J. F., Anderson, E. L., Anderson, L. P., Tibbals, K., & Vernon, T. M. (2005). Confidence in vaccination: A parent model. Vaccine, 23(19), 2486–2493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.026

- Kerr, J. R., Schneider, C. R., Recchia, G., Dryhurst, S., Sahlin, U., Dufouil, C., Arwidson, P., Freeman, A. L., & Linden, S. v. d. (2021). Correlates of intended COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across time and countries: Results from a series of cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open, 11(8), e048025.

- Khubchandani, J., Sharma, S., Price, J. H., Wiblishauser, M. J., Sharma, M., & Webb, F. J. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccination hesitancy in the United States: A rapid national Assessment. Journal of Community Health, [online] 46(2), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x

- Killgore, W. D., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., & Dailey, N. S. (2021). The COVID-19 vaccine is here—now who is willing to get it? Vaccines, 9(4), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9040339

- Krupenkin, M. (2021). Does partisanship affect compliance with government recommendations? Political Behavior, 43(1), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09613-6

- Largent, E. A., & Miller, F. G. (2021). Problems with paying people to Be vaccinated against COVID-19. JAMA, 325(6), 534–535. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.27121

- Larson, H. J. (2018). Politics and public trust shape vaccine risk perceptions. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(5), 316–316. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0331-6

- Larson, H. J. (2020). Stuck: How Vaccine Rumors Start–and Why They Don't Go Away. Oxford University Press.

- Latkin, C. A., Dayton, L., Yi, G., Konstantopoulos, A., & Boodram, B. (2021). Trust in a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S.: A social-ecological perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 270, 113684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113684

- Lau, L., Lau, Y., & Lau, Y. H. (2009). Prevalence and correlates of influenza vaccination among non-institutionalized elderly people: An exploratory cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(1), 768–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.006

- Lazarus, J. V., Ratzan, S. C., Palayew, A., Gostin, L. O., Larson, H. J., Rabin, K., Kimball, S., & El-Mohandes, A. (2020). A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine, [online] 27(2), 225–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9

- Loomba, S., de Figueiredo, A., Piatek, S. J., de Graaf, K., & Larson, H. J. (2021). Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nature Human Behaviour, [online] 5(3), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1

- MacDonald, N. E. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, [online] 33(34), 4161–4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

- MacKenna, B., Curtis, H. J., Walker, A. J., & Goldacre, B. (2021). Trends and clinical characteristics of 57.9 million COVID-19 vaccine recipients: A federated analysis of patients’ primary care records in situ using OpenSAFELY’. British Journal of General Practice, 72(714), e51–e62.

- Mesch, G. S., & Schwirian, K. P. (2015). Social and political determinants of vaccine hesitancy: Lessons learned from the H1N1 pandemic of 2009-2010. American Journal of Infection Control, 43(11), 1161–1165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.031

- Milligan, M. A., Hoyt, D. L., Gold, A. K., Hiserodt, M., & Otto, M. W. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: Influential roles of political party and religiosity. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 27(9), 1907–1917. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2021.1969026

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons. Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development, 24(6), 1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

- Prati, G. (2020). Intention to receive a vaccine against SARSCoV-2 in Italy and its association with trust, worry and beliefs about the origin of the virus. Health Education Research, 35(6), 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyaa043

- Prati, G., Pietrantoni, L., & Zani, B. (2011). Compliance with recommendations for pandemic influenza H1N1 2009: The role of trust and personal beliefs. Health Education Research, 26(5), 761–769. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyr035

- Puri, N., Coomes, E. A., Haghbayan, H., & Gunaratne, K. (2020). Social media and vaccine hesitancy: New updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 16(11), 2586–2593. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1780846

- Ramanadhan, S., Galarce, E., Xuan, Z., Alexander-Molloy, J., & Viswanath, K. (2015). Addressing the vaccine hesitancy continuum: An audience segmentation analysis of American adults Who Did Not receive the 2009 H1N1 Vaccine. Vaccines, [online] 3(3), 556–578. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines3030556

- Razai, M. S., Osama, T., McKechnie, D. G. J., & Majeed, A. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among ethnic minority Groups. BMJ, [online] 372(8283), 1–2.

- Recio-Román, A., Recio-Menéndez, M., & Román-González, M. V. (2021). Global vaccine hesitancy segmentation: A cross-European approach. Vaccines, 9(6), 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9060617

- Reiter, P. L., Pennell, M. L., & Katz, M. L. (2020). Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated?. Vaccine, 38(42), 6500–6507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043

- Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, [online] 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Rodríguez-Rieiro, C., Domínguez-Berjón, M. F., Esteban-Vasallo, M. D., Sánchez-Perruca, L., Astray-Mochales, J., Fornies, D. I., Ordoñez, D. B., & Jiménez-García, R. (2010). Vaccination coverage against 2009 seasonal influenza in chronically ill children and adults: Analysis of population registries in primary care in Madrid (Spain). Vaccine, 28(38), 6203–6209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.013

- Rönnerstrand, B. (2013). Social capital and immunisation against the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 41(8), 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494813494975

- Rönnerstrand, B. (2015). Generalized Trust and the Collective Action Dilemma of Immunization. Göteborgs Studies in Politics 139.

- Rubin, G. J., Amlot, R., Page, L., & Wessely, S. (2009). Public perceptions, anxiety, and behaviour change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: Cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ, 339(jul02 3), b2651–b2651. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2651

- Ruiz, J. B., & Bell, R. A. (2021). Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine, 39(7), 1080–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010

- Savulescu, J. (2021). Good reasons to vaccinate: Mandatory or payment for risk?. Journal of Medical Ethics, 47(2), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106821

- Schwarzinger, M., Watson, V., Arwidson, P., Alla, F., & Luchini, S. (2020). COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy in the French population of working Age: A randomized experiment of vaccine characteristics. SSRN Electronic Journal, 6(4), e210–e221.

- Sekizawa, Y., Hashimoto, S., Denda, K., Ochi, S., & So, M. (2022). Association between COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and generalized trust, depression, generalized anxiety, and fear of COVID-19. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12479-w

- Steen, T. (2021). Citizens’ motivations for Co-production’. In E. Loeffler, & T. Bovaird (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes (pp. 507–526). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Steen, T., & Brandsen, T. (2020). Coproduction during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Will It last?. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 851–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13258

- Sturgis, P., Brunton-Smith, I., & Jackson, J. (2021). Trust in science, social consensus and vaccine confidence. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(11), 1528–1534. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01115-7

- Surgo Ventures. (2021). U.S. General Population COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Survey’. Report from Surgo Ventures.

- Szilagyi, P. G., Thomas, K., Shah, M. D., Vizueta, N., Cui, Y., Vangala, S., Fox, C., & Kapteyn, A. (2021). The role of trust in the likelihood of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine: Results from a national survey. Preventive Medicine, [Online] 153, 106727.

- Tan, M., Straughan, P. T., & Cheong, G. (2022). Information trust and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst middle-aged and older adults in Singapore: A latent class analysis approach. Social Science & Medicine, 296, 114767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114767

- Turk, E., Durrance-Bagale, A., Han, E., Bell, S., Rajan, S., Lota, M. M. M., Ochu, C., Porras, M. L., Mishra, P., Frumence, G., McKee, M., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2021). International experiences with co-production and people centredness offer lessons for COVID-19 responses. BMJ, 372, m4752. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4752

- Velan, B., Kaplan, G., Ziv, A., Boyko, V., & Lerner-Geva, L. (2011). Major motives in non-acceptance of A/H1N1 flu vaccination: The weight of rational assessment. Vaccine, 29(6), 1173–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.006

- Vulpe, S.-N., & Rughiniş, C. (2021). Social amplification of risk and “probable vaccine damage”: A typology of vaccination beliefs in 28 European countries. Vaccine, 39(10), 1508–1515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.063

- Ward, J. K., Alleaume, C., Peretti-Watel, P., Peretti-Watel, P., Seror, V., Cortaredona, S., Launay, O., Raude, J., Verger, P., Beck, F., Legleye, S., L’Haridon, O., & Ward, J. (2020). The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue’. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113414

- Warren, G. W., & Lofstedt, R. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine rollout risk communication strategies in Europe: A rapid response. Journal of Risk Research, 24(3-4), 369–337. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1870533