ABSTRACT

The use of gestational surrogacy as a means of family construction is on the rise, and several legislatures and governments across the globe are currently considering repealing prohibitions on the process. Little is known about the public's attitudes towards this means of conception used by both opposite-sex and same-sex couples. In this paper, I present original experimental evidence from Britain to demonstrate the prevalent role of homonegativity in shaping preferences for surrogacy. Empirically, I leverage a pre-registered experiment to model the independent and combined effects of homonegativity and parasocial (celebrity) contact on support for commercial gestational surrogacy. On average, citizens are largely supportive of the practice. Experimental manipulations, however, provide robust causal evidence that homonegative discrimination exhibits a sizeable negative effect on support for the policy, while exposure to celebrity reliance on surrogacy provides mixed effects. Isolating the underlying causal mechanisms via which treatment assignment shapes outcomes, quantitative text analysis of open-ended survey responses establishes that assignment to different treatment conditions actively influences survey respondents’ explicit reasoning for their revealed preferences, providing additional purchase to causal interpretations of the experimental exposure

Introduction

On 17th August 2021, former Democratic Presidential candidate and sitting US Transportation Secretary in the Biden administration, Pete Buttigieg, announced he and his husband had just become parents to two twin girls. Responses to the announcement were mixed and included praise from those pleased to see one of the most high profile LGBT + politicians become a parent, as well as opposition from conservative pundits who asked, satirically, if the same-sex couple were still trying to work out how to breastfeed their children (Feinberg, Citation2021). One feature of the public discourse surrounding the news focused on the nature of how the two men came to be parents: where did the children come from? Since the couple, initially, did not disclose this information, media reporting speculated the children could have been the result of a surrogacy agreement (Porterfield, Citation2021).

Although the Buttigiegs became parents via adoption as opposed to surrogacy, the widespread negative media speculation regarding their potential reliance on a surrogate is noteworthy. Surrogacy agreements have been used by well-known celebrity couples, including most recently by the international footballer Cristiano Ronaldo, as well as reality TV personality Kim Kardashian and her then-spouse Kanye West, without symmetrical negative reporting. These illustrative examples, therefore, point towards a broader question, and that is to what extent individuals’ views on relying on a surrogate – as detailed below, an increasingly utilized means of conception – are the product of homonegative biases?

To answer this question, I fielded an original, pre-registeredFootnote1 survey experiment among a representative sample of British citizens testing to what extent public support for surrogacy is shaped by (i) homonegative biases, and (ii) parasocial contact (celebrity effects). Empirically, the results of the pre-registered experiment demonstrate that homonegativity exhibits a significant and sizeable negative effect on support for surrogacy. Parasocial contact, however, does not, on average significantly shift preferences. Instead, these effects are conditioned by the sexuality of the surrogate parents. To add causal purchase to the underlying mechanisms behind the support-reducing effect of the experimental manipulation, I also present the results of a quantitative text analysis of open-ended survey responses that solicited individuals to explain the rationale behind their policy preferences in relation to surrogacy. The results demonstrate that random allocation to exposure to same-sex couples, in addition to reducing overall support for using surrogates, also induced an uptake in sexuality-based explanations among those who reject surrogacy.

These results speak to several different literatures. First, they provide a robust causal insight into the persistent influence, despite changing attitudes to LGBT + rights in Western societies (Abou-Chadi & Finnigan, Citation2019; Dotti Sani & Quaranta, Citation2020), of homonegative biases in shaping individuals policy preferences. A wide body of work looks at the determinants of negative preferences towards LGBT + individuals (Jones, Citation2022) and political candidates (Magni & Reynolds, Citation2021) but little work has sought to assess if these biases have downward effects on influencing support for concrete policies. Assessing the presence homonegativity is hard and constrained by social desirability bias and preference falsification. This experimental setting seeks to overcome these methodological limitations and innovates by moving away from asking about concrete support for an apparently socially marginalized group, by instead asking if respondents would express a comparable endorsement for certain policies independently of the sexuality of those prone to benefit from the reform.

Second, the findings speak to a wider body of scholarship that seeks to explore evolving attitudes to policy areas that fall within the remit of ‘morality politics’ (Arzheimer, Citation2015; Engeli et al., Citation2012; Engeli et al., Citation2013) by establishing how an issue of contention in terms of bioethics, similar to that of genetic screening (Arzheimer, Citation2020), is actually an issue that enjoys high levels of public support. Finally, this study adds to the empirical literature that seeks to analyse, and causally identify (Alrababa’H et al., Citation2021; Klüver, Citation2021), the role of exposure to parasocial contact and celebrity effects on attitude-formation (Driessen, Citation2022; Kosenko et al., Citation2016; Merivaki & Mann, Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2020).

Surrogacy: a changing global policy landscape

Birth rates in developed countries are on the decline (Lutz, Citation2006). Birth rates in industrialized nations, at present, have passed the point of equilibrium by becoming lower than the rate required for the ‘quantum of fertility’ which ensures minimum organic replacement levels (Lutz, Citation2006). Whilst a fall in the birth rate can be attributed to a catalogue of factors such as social and economic change (Engelhardt & Prskawetz, Citation2004), the transformation in cultural values (Guetto et al., Citation2015), and economic shocks (Matysiak et al., Citation2021); an additional contributing factor is the rise in infertility (Levine et al., Citation2017; Mascarenhas et al., Citation2012; Rossen et al., Citation2018). Evidence of rising involuntary infertility is evinced in the rising demand for reproductive health and for artificial reproductive treatments. In the UK alone, the annual number of assisted reproduction treatments administered has more than doubled between 2000 and 2019 (see appendix Figure A2).

Amongst the medical remedies for infertility for couples that are unable to conceive their own biological children, regardless of the sexual orientation of the aspiring parents, is surrogacy. Of the twenty-seven member states of the European Union (EU) – and neighbouring Norway, Switzerland and the UK – only eight countries do not expressly prohibit surrogacy (see appendix Table A9). Of the three states that have a concrete legislative framework to regulate surrogacy – Greece, Portugal and the UK – the UK is the only country that permits surrogacy use by same-sex couples. Whilst surrogacy has been legally recognized in the UK since the 1985 Surrogacy Arrangement Act, the process was only opened to same-sex couples in 2010 following the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act. Crawshaw et al. (Citation2012), relying on data provided by the General Register Offices of England and Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland, show that the (re)regulation of surrogacy laws to liberalize the process to include both single individuals and same-sex couples resulted in a sizeable spike in the number of Parental Orders – the legal process that transfers parentage from surrogate mothers to the commissioning parents in the UK (Latham, Citation2020). Between 2010 and 2011, when the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act (2008), amended the eligibility criteria to facilitate surrogacy for same-sex couples, the number of granted parental orders increased by 77 per cent. Crawshaw et al. (Citation2012) attribute this drastic shift in the uptake in surrogacy use by gay men and lesbians which has been further facilitated by the emergence of concrete non-profit agencies like the British Surrogacy Centre, which were set up specifically to cater to the demand of same-sex couples aspiring to become commissioning parents.

As in the case of all other EU states that do not prohibit surrogacy use, the UK only permits surrogacy on an altruistic basis. The UK does not permit commercial surrogacy and during the process when parental orders are sought, the court appraising the application assesses whether the surrogate has been provided with financial competition beyond that which might be considered ‘reasonable expenses’ (Latham, Citation2020). Within the current legislative framework there is no concrete definition of what constitutes ‘reasonable expenses’ and a 2020 All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) recommended greater transparency on this issue as part of the government's current ongoing reform of surrogacy legislation.

Contemporary debate in surrogacy policy & regulation

Most states do not currently provide legal means via which aspiring parents can commission surrogacy agreements. Several states are, however, actively engaged in ongoing debates related to the issue. In the UK, for example, where altruistic surrogacy has been facilitated since 1985, the House of Commons recently debated surrogacy reform, and, at present, the UK Law Commission is working on a draft Bill in response to a 2019 consultation paper. In Spain, the country's right-wing self-penned ‘liberal’ party, Ciudadanos [Citizens] proposed a bill in 2017, and then again in 2019, that would introduce regulated surrogacy access. In 2021, a Member's Bill was tabled in New Zealand's House of Representatives that sought to simplify surrogacy processes and make surrogacy agreements enforceable. Political debate over the liberalization of surrogacy prohibitions and/or regulations are not, therefore, without consequence as these debates are actively taking place in state legislatures and, consequently, have real-world policy implications.

Opponents to liberalizing regulations to either remove the prohibitions on surrogacy or to introduce a compensation component come from a unique coalition made up of socially conservative and religious organizations, as well as certain – and typically left-wing – feminist groups. Alongside their opposition to the legal recognition of trans women (Turnbull-Dugarte & McMillan, Citation2022), support for maintaining and/or introducing a prohibition on surrogacy use represents one of a minute collection of policy areas where the political inclinations of certain feminist groups and religious organizations coalesce (Ventura et al., Citation2019).

Policy preferences related to surrogacy fall within the heterogeneous category of issue concerns that Engeli et al. (Citation2012) pen ‘morality politics’. Political issues of this kind, which include contemporary concerns such as stem-cell research or reproductive rights (Arzheimer, Citation2015, Citation2020), are distinct from conventional policy matters as an individual's views on such issues are often less amenable to political party cues and more prone to be formed by a set of fundamental moral and ethical values established via early life processes and socialization (Engeli et al., Citation2012; Putnam & Campbell, Citation2010). Conservative opposition to surrogacy is often framed via moralistic concerns that are read as the product of religiously motivated reasoning. The conservative critique essentially posits that the process disrupts the sanctity of traditional (read heteronormative) family structure; interferes with the ‘organic’ reproductive process; and, as a human intervention that has life-creating potential, is ethically reprehensible.

Distinct from conservative opposition to surrogacy, the central tenant of those feminists that express opposition to surrogacy – be that altruistic or commercial – is that the process can be detrimental to women's welfare. Primarily, these feminists view surrogacy as indicative of the commodification of women's bodies and a product of capitalism's pursuit to source rental revenue from empty wombs. This opposition, one that opposes the commodification of women as mere ‘breeders’, is accompanied by concerns for women's individual welfare. An underlying concern is that, given it is apparentlyFootnote2 incomprehensible that a women would voluntarily give up their child, then entering a surrogacy agreement must be the result of external coercion, financial necessity, or a combination of the two, which reduces surrogacy to an exploitative process where women engage without free will.

Empirical data on the demographic profile of surrogates in the United States, however, is at odds with the critique presented by these feminist arguments. Busby and Vun (Citation2010) show that the average US surrogate mother is white, 30 years old, of average psychological disposition and falls within the median range on the income distribution. The white-leaning racial profile of domestic surrogate mothers in the US is of note as part of the debate over surrogacy is the potential for exploitation of race-based social and economic inequalities that might result in the bodies of non-white women being commodified to facilitate childbearing for white women.Footnote3 Ethnographic evidence based on surrogate mothers’ experiences in Israel also challenges the narrative of exploitation. Teman (Citation2010), for example, finds that surrogate mothers have far more active agency than feminist critiques of surrogacy would assume and Bromfield (Citation2016) demonstrates that women who elect to be surrogate mother's often highlight the decision as an example of their independent decision-making power over their own bodies not dissimilar from the autonomy that feminists proclaim when advocating for liberal regulations regarding abortion.

The desirability of surrogacy is, ultimately, a normative question. My empirical concern is ascertaining: (i) who supports the policy, and (ii) what factors can influence shifts in preferences.

Public opinion & surrogacy

Empirical research on public opinion related to surrogacy is limited. Tremellen and Everingham (Citation2016) provide evidence of high levels of support for surrogacy use in Australia where legislation currently includes provisions for altruistic surrogacy. Their survey found that 88 per cent of respondents support access to surrogacy for married couples, 64 per cent for (unmarried) heterosexuals and 62 per cent for homosexuals. Despite Australia's ban on commercial (compensated) surrogacy, of those respondents who held an opinion on this prohibition, 58 per cent believed that this ban was unjustified suggesting that Australians hold a majority position in favour of commercial surrogacy. As far as I am aware, there has yet to be any empirical analysis of public opinion on the policy in Europe despite the increasingly salient political nature of this debate.

Theoretical expectations

I argue that homonegativity and parasocial contact can exhibit significant preference-shaping effects on individuals’ expressed support for surrogacy. In popular discourse over surrogacy, the practice is often presented with contextualized examples based on surrogacy use by (often male) same-sex couples. A simple online search using the search term ‘surrogacy’, shows that a majority of the stock images accompanying the leading news stories present same-sex couples. Media reporting of surrogacy focuses disproportionately on surrogacy commissioning by same-sex couples. Robust empirical assessments of media reporting in both the UK (van den Akker et al., Citation2016) and Spain (Ventura et al., Citation2019), for example, highlight how televised reports of surrogacy often conflate the process as being something of a ‘gay issue’ as they tend to provide anecdotal accounts that systematically and disproportionately centre on surrogacy use by gay (male same-sex) couples despite the process remaining dominantly used by aspiring heterosexual parents. Importantly, and given the salient role that the media play in informing public opinion (Happer & Philo, Citation2013), the effects of this disproportionate focus on same-sex couples’ use of surrogacy is likely to engender associations between the policy and the LGBT + collective. When soliciting respondents’ views regarding surrogacy among members of a focus group exposed to media reporting on surrogacy in Spain where ‘[t]he homosexual is […] represented as an oppressor of vulnerable [female] subjects’, Ventura et al. (Citation2019) find that the overwhelming majority were opposed to surrogacy.

A wealth of evidence demonstrates that, across different states, attitudes towards same-sex parenting are still constrained (Ioverno et al., Citation2017), even in those countries where support for same-sex marriage rights has actually increased (Dotti Sani & Quaranta, Citation2020). In Britain, where same-sex adoption has been in place since 2002Footnote4, acceptance towards homosexuality has increased over time and the traditional distinction between the voting constituents of the main political parties on these issues has significantly weakened in recent years (Turnbull-Dugarte, Citation2022). Nevertheless, homonegativity remains a discriminatory bias that, when activated in an individual, is likely to influence their policy preferences on issues involving non-heterosexual individuals. As demonstrated by (Dotti Sani & Quaranta, Citation2020) negative preferences related to LGBT + rights are often more salient and active when it comes to issues related to children. Although individuals may express tolerance of homosexuality, per se, or equal marriage rights, they are far less inclined to express support for the right of same-sex couples to adopt. Conservative actors have also exercised vocal opposition to LGBT + topics in the classroom – such as Florida's recent Don't Say Gay Bill – in order to, according to their rationale, ‘protect’ children (Goldstein, Citation2022; Philips, Citation2022). My first hypothesis, therefore, assumes that homonegativity – activated via exposure to same-sex couple use of a surrogate – will negatively impact support for surrogacy:

H1: Individuals exposed to the use of a surrogate by a same-sex couple will become less supportive of the use of surrogacy.

As discussed above, debates about surrogacy involve multiple dimensions. As with many other socio-political issues, the debate often involves multifaceted components including concerns regarding morality, desirability, participant welfare and the economic exploitation of women. When faced with policy questions that involve multiple facets and complex arguments that are beyond their own experience and/or relevance to their everyday lives, citizens often rely on shortcuts to form their political preferences (Zaller, Citation1992). Typically, partisanship – affective loyalty or association with a certain political party or issue-based group – acts as an information heuristic that informs individuals of what people who vote ‘like them’ think about a certain issue.

In addition to partisanship, and other information shortcuts, individuals often rely on their personal experience to form their preferences towards certain policies or certain groups. One of the prevalent theories that help understand preferences towards socially dissimilar individuals – or out-groups – is Allport (Citation1954)'s social contact theory. Contact theory assumes that, under certain conditions, interpersonal contact between individuals can engender greater cross-group tolerance, acceptance and understanding. Tests of Allport's contact hypotheses have shown, for example, how interpersonal interactions with ethnic out-groups can reduce discriminatory prejudices based on religion (Mousa, Citation2020) or ethnicity (Finseras & Kotsadam, Citation2017).

In the absence of real or lived personal contact, however, individuals may form preferences based on parasocial contact. The parasocial contact thesis, as theorized by Schiappa et al. (Citation2006), coalesces Allport's contact theory with the idea of parasocial interaction (Horton & Richard Wohl, Citation1956). As Horton and Richard Wohl (Citation1956, p. 215) argue, individuals’ exposure to media personalities, regardless of whether these personalities are fictional or real, facilitates ‘the illusion of a face-to-face relationship’ with the personality. Parasocial contact then serves as a ‘functional alternative’ to direct interpersonal contact (Rubin & Rubin, Citation1985) and allows us to understand how exposure to media personalities – such as celebrities – can catalyze an updating in a person's attitudes towards concrete groups or specific policy issues.

Empirical support for the parasocial contact thesis is provided by Schiappa et al. (Citation2006) who, analysing exposure to the US sitcom Will & Grace which focused on gay male protagonists, demonstrated that parasocial contact has a significant prejudice-reducing effect on attitudes towards gay men.Footnote5 The observed effect is, in terms of its magnitude, comparable to that of direct interpersonal contact. Whilst Schiappa et al. (Citation2006)'s test of parasocial contact relied on contact where the personalities that individuals interacted with were fictional (the gay male characters of Will & Grace), successive empirical contributions have also demonstrated the influential role of parasocial contact with celebrities. Alrababa’H et al. (Citation2021), for example, leverage observational data in the UK based on reported hate crimes and social media posts to demonstrate that parasocial contact with Mohammed Salah – an openly expressive publicly-practicing Muslim and popular football player for Liverpool Football Club – significantly reduced hate crimes and hate speech on social media. The authors argue that Salah, as a ‘celebrit[y] with role model-like qualities’ is able to influence social attitudes and behaviours.

Celebrities can exhibit parasocial contact effects via their role as personalities in the public eye that individuals are likely to enjoy a sense of familiarity with without knowing the celebrity on an individual level. A wide catalogue of cross-disciplinary work demonstrates that celebrity endorsements and associations can trigger significant alterations in individuals’ behaviour. Celebrity-led advertising campaigns are more effective at increasing consumer spending compared to those without celebrities (Elberse & Verleun, Citation2012; Erdogan, Citation1999), public awareness campaigns utilizing celebrities can catalyze increased attention towards matters of public interest such as issues related to health (Noar et al., Citation2014), and explicit celebrity political endorsements can influence voter registration (Merivaki & Mann, Citation2019), feelings of political efficacy (Austin et al., Citation2008), and even preferences at the ballot box (Klüver, Citation2021).

Celebrity influence on individuals’ preferences via parasocial contact need not, however, come in the form of explicit political endorsements or concrete promotional activity or advocacy. Given their presence in the public eye and their prevalent role in popular culture, celebrities are also able to indirectly endorse positions on controversial or salient issues ‘by practice’. The case of Mohammed Salah considered above represents one such example. The negative effects of exposure to Salah on the prevalence of hate crimes and hate speech were not the result of any vocal advocacy or endorsement of Islam, but rather football fans, who became aware of the religious practice of an individual they admire, becoming less inclined to engage in prejudicial activity.

Miller et al. (Citation2020) present a similar argument to help understand public attitudes towards transgender rights. Focusing on the case of Caitlyn Jenner – an Olympic gold medallist and widely successful reality TV star who came out as a trans woman in 2015 – the authors argue that ‘when Jenner revealed her transgender identity, she was neither a candidate nor was she endorsing a candidate. Rather, her political act was to be open about her identity’ (Miller et al., Citation2020, p. 623). Relying on survey data from the US fielded at the time of the news story, the authors demonstrate that those following the news became more supporting of transgender rights in response to their parasocial contact with Jenner. Importantly, Miller et al. (Citation2020) highlight that part of the reason the parasocial effects were able to exhibit an attitude-shaping effect on the public's attitudes towards transgender rights is because the average US citizen has not had any personal or direct exposure with a trans individual. In this situation where a lack of interpersonal contact restricts the ability of individuals to make assessments based on personal exposure and experience, individuals are inclined to rely on media cues and parasocial contact to make up their minds.

In both the Salah and Jenner examples, parasocial contact involved identity-based practice: religious identity and (trans)gender identity, respectively. Parasocial contact or ‘by practice’ endorsements need not, however, be identity based. Hollywood actor – Angelina Jolie – provided a by-practice endorsement of preventative hysterectomies and preventative mastectomies when she publicly announced that she had undergone the procedures after genome screening revealed she was at risk of developing cancer. Kosenko et al. (Citation2016) use original survey data to show that parasocial contact with the Jolie case increased self-reported intentions for gene testing, and Desai and Jena (Citation2016), leveraging observational data on private health insurance claims from the US, evince that in the days following the Jolie news story there was an immediate uptake in requests for genome testing. Parasocial contact is influential: not only can it engender attitude change, as the Salah and Jenner cases illustrate, but it can also change individual behaviour.

I expect a similar relationship to play out in the case of attitudes towards surrogacy. Given a context where individuals are not commonly exposed to same-sex parenting (Costa et al., Citation2015) and a lack of knowledge and understanding regarding the medical and/or legal processes surrounding gestational surrogacy (Bruce-Hickman et al., Citation2009), individuals are far more inclined to rely on media cues and parasocial contact to form their opinion about surrogacy.

In seeking to understand the rising social tolerance towards the use of surrogacy (Poote & Van Den Akker, Citation2009), Crawshaw et al. (Citation2012) makes the argument that the increasing use of the process by high profile celebrities has likely contributed to shifts in public attitudes. Recent notable cases of celebrities relying on surrogates include, to name just some examples, the Portuguese footballer Cristiano Ronaldo, reality TV star Kim Kardashian and her (then) rapper husband Kanye West, Hollywood actress Nicole Kidman, Latin singer Ricky Martin, and Star Wars creator George Lucas. Surrogacy has also become further normalized via its representation in popular culture. In the hit 90s sitcom Friends – one of the most successful and widely watched television series of all time – one of the show's protagonists took on the role of surrogate mother. In the episode titled ‘The One with the Embryos’, which originally aired in January 1998, Phoebe agrees to become a gestational surrogate for her brother and his (heterosexual) partner who are unable to conceive children on their own. Given the mainstreaming and influential role of celebrity endorsements and celebrity examples in driving and shaping public preferences and electoral behaviour, my second hypothesis posits:

H2: Individuals exposed to the use of a surrogate by a celebrity couple will become more supportive of the use of surrogacy

Research design

To test the theoretical hypotheses posited above, I rely on data collected via an original survey fielded to a representative sample of online panel respondents in the UK during March 2021. The sample (N = 2000) was compiled via four-way stratification of the UK population based on gender, race, age and education. A comparison of the distribution of these strata identifiers within the sample and the weighted sampled of the British Social Attitudes Survey is reported in Table A2 and confirms that the demographic composition of respondents is reflective of population parameters. Full summary statistics are reported in appendix Table A1 and covariate balance across treatment assignment is detailed in Table A3. The target sample N of 2000 was sought in order to provide the necessary power for the experiment's factorial design. Power calculations (based on α < 0.05) included in the pre-registration and pre-analysis plan are demonstrated in Figure A10 and Figure A11.

The UK is taken as an appropriate case to test the hypotheses for two reasons. First, self-reported tolerance towards LGBT + individuals among citizens in the UK (92 per cent) is comparable to that in other Western European countries. The proportion of LGBT+ individuals who feel anxiety about public displays of affection, although high at 62 per cent, is not dissimilar to proportions reported by neighbouring European states (see appendix Figure A3). Moreover, expert evaluations of the UK's provision of LGBT + inclusive policy provisions, such as that of ILGA-Europe, provide the UK with an inclusion score comparable to that of the country's west European peers. In other words, the UK is not an outlier in terms of its social tolerance or institutional recognition of LGBT+ individuals and, as a result, one can expect the presence of homonegativity to be observed here to replicate in comparable states. Second, the UK actively permits surrogacy use and as such is a case where treatment texts exposing respondents to surrogacy use are externally valid and do not communicate examples of commissioning surrogates in states where the process is prohibited, the illegality of which may induce more negative responses. At the same time, however, given that surrogacy has been legalized in the UK for close to forty years, it is also likely that the top-line level of support for the policy will be greater than one might expect to observe in states where the process remains subject to prohibitions.

Treatment allocation & messages

The identification strategy relies on an experimental design that randomly assigned individuals to one of five treatment groups. The experimental design includes an untreated control group and a fully factorial 2 × 2 design with treatment heterogeneity present on both the dimension of sexuality and parasocial contact.

The first treatment group (T1) was exposed to a message that informed respondents of the use of surrogacy by a same-sex celebrity couple: Olympic Champion Tom Daley and his screen-writer husband Dustin Lance Black. The second treatment group (T2) was informed of the use of surrogacy by an opposite-sex celebrity couple: the actor Sarah Jessica Parker and her actor husband Mathew Broderick.Footnote6 Treatment group three (T3) were informed of surrogacy use by a fictitious same-sex couple (Tom Smith and his husband) whereas the fourth treatment group (T4) were presented a fictitious opposite-sex couple (Jessica Smith and her husband). The control group (C) was asked about their preferences related to surrogacy without being informed of surrogacy use by any concrete couple. Images of the treatment messages and accompanying text are presented in the online appendix (Figures A6–A9).

A potential limitation to this factorial comparison of treatment messages is that respondents could, potentially, infer additional information from the manipulation. For example, respondents might assume that the opposite-sex couples were not in ‘stable’ relationships or that the celebrity couples likely relied on commercial surrogacy whilst the ordinary couples may have opted for altruistic surrogacy. The treatment messages were, therefore, explicitly designed using the ‘covariate control’ approach recommended by Dafoe et al. (Citation2018) which aims to provide explicit information signals to respondents in order to limit the potential for additional inferences. Considering the risk of the adjacent inferences suggested above, for example, all treatment messages made it clear that the couples were married by making explicit reference to ‘husbands’ and all the of the surrogate mothers were described as ‘paid surrogates’. I focus concretely on paid surrogacy given that the issue of commercializing the process is one of the areas of contention around the debate. As concerns over monetization and potential economic exploitation are likely to suppress support for paid surrogacy, it is probable that the top-line levels of support reported in the analysis that follows masks higher levels of support for altruistic surrogacy.

Outcome measure

The outcome of interest is individual-level support towards the use of commercial surrogacy as a means of having children. The outcome is measured via the following survey instrument and responses: To what extent to do you agree that couples who are unable to conceive biological children on their own, should be allowed to pay a surrogate to help them have biological children?

Responses are measured on an ordinal 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The order of the ordinal response scale was randomized for individual respondents so that neither ‘Strongly agree’ or ‘Strongly disagree’ was constantly first placed. As per the pre-analysis plan, I also dichotomize support for surrogacy, comparing those individuals who adopt a supportive position, ‘Strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ (1), versus all others (0). The model specification relies on a basic linear OLS regression model (alternatives in appendix) in which δ1TreatmentConditioni is a categorical indicator of the assigned treatment condition. I model the effects of homosexual and parasocial contact against the control group baseline, as well as vis-à-vis the heterosexual and civilian treatment groups.

Results

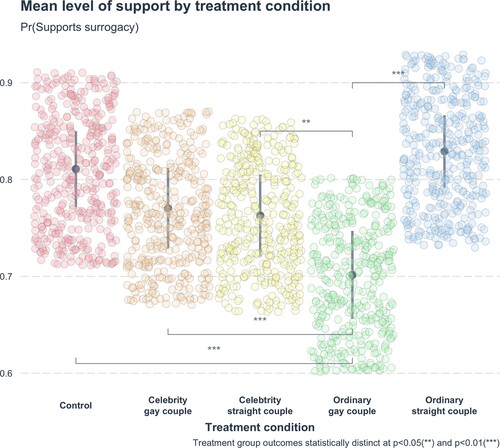

The results of the experimental manipulation are summarized in and . reports the average treatment effect (ATE) of assignment to one of the four treatment conditions vis-à-vis control. Model 1 reports the unadjusted ATE on support for surrogacy as measured via our 5-point Likert scale. Model 2 includes socio-demographic covariates and Model 3 incorporates political controls. Models 4–6 replicate the specification reported in Models 1–3 and estimate the ATE of treatment allocation on the probability of supporting surrogacy use via our dichotomous (support vs. does not support) indicator.

Table 1. Average effect of treatment condition vs control group.

For ease of interpretation, I focus on discussing the predicted levels of support for surrogacy between the four treatment groups and control visualized in . A first notable finding is that the aggregate level of support for surrogacy is very high. On average, just over three in four individuals (77.5 per cent) report that they either strongly agree or agree with the use of surrogacy. This substantively high level of support is of note. Surrogacy use is on the rise both in the UK, where the experimental data comes from, but also across several developed and developing countries. Here, I show that the public are very much in agreement with the use of surrogacy as a means of starting a family. Current UK legislation mandates that surrogacy agreements must be limited to altruistic participation. The strong level of support recorded here – where wording makes explicit reference to commercial surrogacy suggests that the British public, much like that of Australia (Tremellen & Everingham, Citation2016), is not opposed to this financial and compensatory element.

There are, however, some notable differences in the level of support between individuals assigned to each of the different treatment conditions as also reported in . When it comes to understanding what influences public support, attitudes are significantly influenced by discriminatory homonegative biases. Among the five treatment groups, the lowest level of support for surrogacy is observed among respondents in treatment group 3: those presented with an example of surrogacy use by a non-celebrity same-sex couple. When asked whether they agree with the use of surrogacy after exposure to a non-parasocial same-sex couple, 30 per cent of respondents indicated a lack of support. The highest level of support, on the other hand, is reported amongst those respondents assigned to treatment group 4. Respondents presented with the case of a non-celebrity opposite-sex couple, only 17 per cent openly expressed a lack of support for using a commercial surrogate.

In comparison to the control group, the effect of treatment assignment to each of the four treatment messages is indistinguishable from zero except for those exposed to the ordinary gay couple. Vis-à-vis control, individuals primed on the use of surrogacy by a non-celebrity gay couple became 11 percentage-points (β = 0.109 | t = −3.58) less likely to support surrogacy. In contrast to our expectation regarding the support-inducing role of parasocial contact of surrogacy use, the treatment effect of exposure to either of the conditions with a celebrity is insignificant. The insignificant effects of exposure to celebrity use of surrogacy vis-à-vis control does, however, mask significant and important variation in the role of parasocial exposure in comparison to the other treatment groups. A direct comparison between heterosexual and homosexual civilian couples captures the concrete effect of homonegativity. In this comparison, those in receipt of the homosexual couple treatment are 13 percentage-points less likely to support surrogacy vis-à-vis those in receipt of the heterosexual couple treatment.

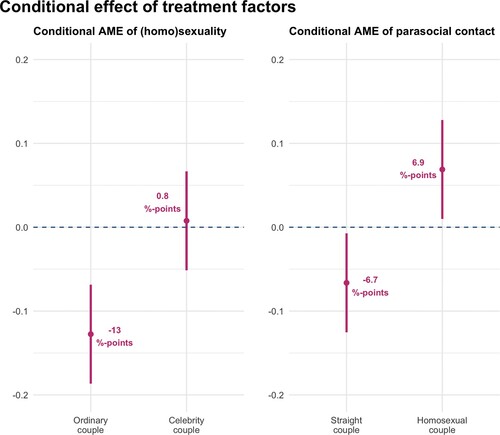

In , I assess the asymmetric effect of each of the treatment factors (e.g., sexuality and parasocial contact) for each of the possible values of the other factor, excluding individuals in the control condition. In other words, is the effect of (homo)sexuality (0–1) conditional on whether the presented couple are celebrities (1) or not (0)? The left-hand panel of illustrates the ATE of the ‘gay couple’ factor when the presented couple are ordinary civilians and, subsequently, when the treatment couple are celebrities. Signalling respondents about the (homo)sexuality of the surrogate users only introduces a significant discriminatory penalty when the presented couple is not based on parasocial contact. Whilst exposing respondents to a same-sex couple depresses support for surrogacy by 13 percentage-points in comparison to an ordinary opposite-sex couple, varying the sexuality of celebrity couples exhibits no effect of significance on support for surrogacy.

The right-hand panel of considers the ATE of the parasocial contact factor when the presented couples are straight (heterosexual) or gay (homosexual). When the couples presented in the treatment message are opposite sex, introducing the parasocial factor significantly decreases support for surrogacy by 6.7 percentage-points. This finding is significant as it at odds with the theoretical claims assuming that increasing exposure to reports of surrogacy commissioning by well-known celebrities can drive support for liberalizing the policy among the general population (Crawshaw et al., Citation2012). The results of this experimental test suggest that, at least when the presented couples are constituted by individuals of the opposite sex, parasocial exposure to celebrity commissioning parents inimically influences positive opinions on surrogacy. The effect of parasocial contact is reversed when the presented couple is gay. When the treatment couple is of the same-sex, introducing the celebrity factor significantly increases support for surrogacy by 6.9 percentage-points. This suggests that exposure to gay celebrities has the potential to partially dilute the discriminatory biases of homonegative attitudes. An alternative interpretation of these results could be that the homosexual (Tom Daley) and heterosexual (Sarah Jessica Parker) celebrities enjoy systematically different levels of public support. Data from YouGov's online approval rating tracker (visualized in Figure A5), however, suggests that this is not obviously the case. At the time of fielding the experiment (March 2021), the mean likeability of Daley was 47 per cent which is a figure comparable to that of Jessica Parker at 44 per cent.

Exploratory analysis

Some of these results are at odds with the pre-registered hypotheses. One finding of note is that the inimical penalty on support for surrogacy when respondents are primed with same-sex couples is only observed in when ordinary (non-celebrity) couples are presented. An exploratory analysis demonstrates under what conditions these effects may be moderated. I identify these analyses as exploratory given they were not part of the pre-registered analysis plan.

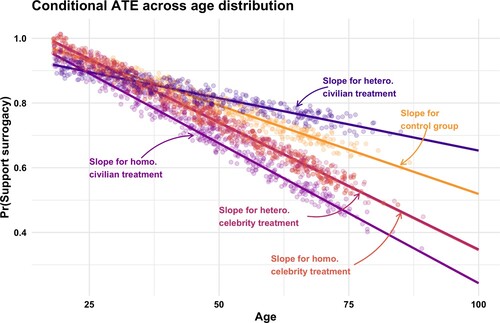

demonstrates the moderating effect of age. As visualized, regardless of respondents’ age, varying the sexuality of the presented celebrity couple does not exhibit any influence on support for surrogacy – the slopes for the two celebrity treatments (straight and gay) overlap perfectly. One the other hand, however, the results suggest that the substantive negative effects of (homo)sexuality on those presented with civilian couples is substantially greater amongst older respondents. Tests of the linearity assumption of multiplicative linear interactions do not condition these significant interaction effects (see Figure A15). Young individuals’ attitudes towards surrogacy use appear to be unbiased by discriminatory homonegative attitudes whilst the same is not true of older voters who, when exposed to surrogacy use by ordinary same-sex couples, become significantly and substantively less supportive of the policy compared to those exposed to ordinary opposite-sex couples. The significant moderating role of age that results in asymmetric treatment effects for the (homo)sexuality factor is not surprising. Older citizens tend to be more socially conservative and, as a result, are more inclined to view engagement in homosexual activity as both socially and morally reprehensible vis-à-vis younger cohorts in the population. Part of age's role in conditioning treatment effects may be the result of age serving as an indirect measure of social conservatism. Testing for asymmetric responses to treatments amongst social conservatives confirms that this is indeed the case (see Figure A12).Footnote7

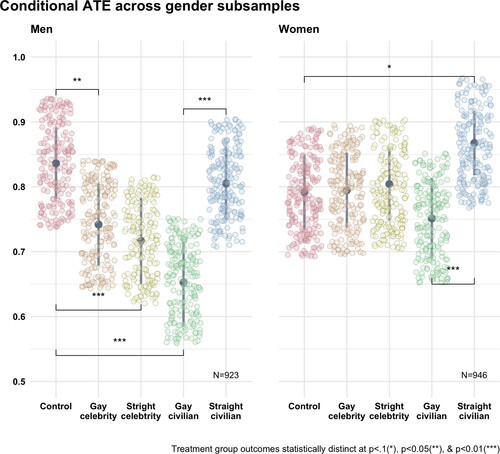

Among the observational correlations observed among the individual-level covariates (Table A4), the results demonstrate that, on average, women are far more inclined to be supportive of surrogacy than men. Consistent with this finding, testing asymmetric responses to treatment between men and women finds that, whilst overall support is lower among men, the effect of homonegativity bias is prevalent in both groups when comparing support between treatment conditions three and four. In terms of parasocial contact, the effect is significantly negative among men, but women respondents’ evaluations of surrogacy do not appear amenable to the parasocial treatment condition. The significantly negative effect of parasocial contact among men – in addition to the negative effects of exposure to a homosexual civilian couple – may be the result of men being less positively pre-disposed to the celebrities under consideration (). One may well expect, for example, that exposing heterosexual men to news of the use of a surrogate by a fellow heterosexual and more explicitly masculine-presenting male, like the footballer Cristiano Ronaldo, could result in positive effects.

Understanding opposition: a QTA test of the mechanisms

Experimental manipulation provides strong causal evidence that individuals’ approval of surrogacy is influenced by discriminatory homonegativity. Randomly assigning respondents to receive information regarding the use of surrogacy by same-sex couples, the mean level of support for the policy is significantly and substantively lower than if they were presented with an opposite-sex couple, or no couple at all (control). An assumption of the inferences from this experimental design is that differences in the outcome resulting from random assignment to the sexuality condition are because of the activation of latent homonegative biases. To test this mechanism and to enrich the causal purchase of the design, I rely on the quantitative text analysis (QTA) of respondents’ self-reported rationales for their policy preferences. Within the survey, I included an open-ended response question to permit respondents the opportunity to elaborate on the reasoning behind their decision. The question, presented immediately following post-treatment outcome measurement, asked: Thinking about the previous question, what mattered most to you when considering your answer?

Leveraging this data, and advancing the causal interpretation of the findings by isolating the underlying mechanism at play, I ask: does treatment assignment increase the prevalence of sexuality-based reasoning in preferences?

An initial qualitative exploration of the responses from those who opposed surrogacy also provides illuminating insight into respondent reasoning. A common theme among the presented rationales, for example, was concern over surrogacy use by same-sex couples that highlighted, amongst other features, homophobic concerns that reflect traditional views in line with moral panic arguments (Wise, Citation2000) and those related specifically to children (Dotti Sani & Quaranta, Citation2020) and their welfare:

I have mixed feelings about surrogacy but, overall, I think it’s not desirable especially if it opens the door to gay men having children.

74-year-old Labour-voting white woman

Their sexual orientation mattered to me, and I don’t think it’s not natural for these people to care for children.

43-year-old non-voting Black man from London

It's a no from me. Same sex couples can't give a child a natural home. Children need a mother.

46-year-old white woman from East Midlands

Type of parents matters the most. Gay parents are dangerous.

54-year-old Black woman non-voter from West Midlands

I am against gays having children.

69-year-old Liberal Democrat-voting white woman from East Midlands

How suitable the couple are and it’s not just a fashion item for gays on Instagram.

64-year-old Conservative-voting white man from Wales

Concerns about the exploitation of women by gay men.

68-year-old Labour-voting white woman

Disquiet about the potential exploitation of women, as highlighted above in the theoretical discussion, are common in debates surrounding surrogacy use. Issues of inequality in access to, and reliance on, surrogacy between individuals at different ends of the socio-economic distribution, may also explain the negative effects of celebrity status among individuals exposed to heterosexual couples. Apprehensions regarding the transactional nature of surrogacy do indeed emerge in respondents’ self-reported reasoning:

The idea of using a woman as an incubator and a baby as a commodity.

39-year-old Labour-voting white woman from Essex

The fact that the more affluent in society can BUY a child seems wrong.

62-year-old Liberal Democrat-voting white man from Northwest England

The pay bit. That part doesn't sit right with me.

38-year-old Labour-voting mixed-race man from Northwest England

I am strongly opposed to surrogacy and wanted to say that women’s bodies and children should not be regarded as commodities to be bought and sold.

63-year-old non-voting white woman from London

The idea of payment: some may not be able to afford it and that’s not really fair in my eyes.

21-year-old Labour-voting white woman from London

I don’t like the payment element.

46-year-old Green party-voting white man from Southwest England

Commodification of the pregnant mother’s womb.

38-year-old Labour-voting Asian man from London

There are too many people on the planet. Don't SHOP-adopt!

50-year-old Green party-voting white women from Southwest England

Quantitative text analysis

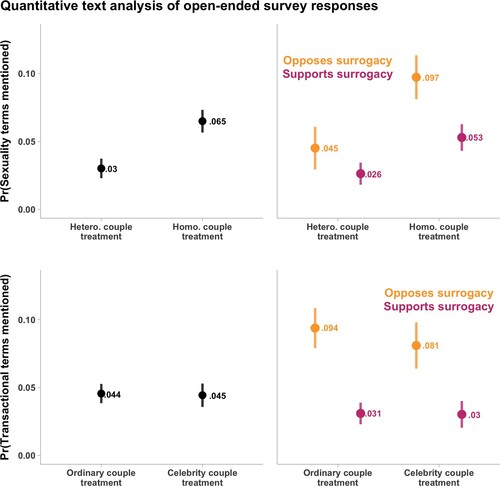

To build on these qualitative insights, I apply quantitative text analysis tools to the experimental respondent's open-ended survey responses. A simple assessment of the relative ‘keyness’ of core terms (Bondi & Scott, Citation2010) used by individuals in their responses by treatment condition is reported in Figure A16. The overall frequency of core terms by treatment condition is also provided in Figure A17. Empirically, I test to what extent treatment allocation (i) engenders sexuality-based or transactional-based self-reported reasonings for treated subjects, and (ii) whether the prevalence of these themes can help explain opposition to surrogacy. To do this, I rely on an automated dictionary-based approach whereby the corpus of open-ended response terms is quantitatively matched against pre-defined word lists designed to capture the topics of interest. Two dictionaries are applied: one capturing sexuality terms, and another capturing transactional terms. With the automatically coded corpus of 5525 items, I estimate a model predicting the congruence with items from each of the dictionaries.

In , I report the effect of the different treatment factors on the probability of open-ended responses referencing issues related to sexuality (upper panel), and the transactional nature (lower panel) of gestational surrogacy. As expected, and depicted in the top-left panel, individuals in receipt of the homosexual treatment factor are significantly more inclined to explicitly reference sexuality terms in the self-reported rationale for their views on surrogacy. The difference is, in real terms, an increase in excess of 100 per cent: 3 per cent in the heterosexual treatment and 6.5 per cent in the homosexual treatment. Significant variation is observed, however, between those who oppose and support the policy. The top-right panel of depicts the effect of the sexuality treatment factor conditioned by dichotomous support for surrogacy. Individuals opposed to surrogacy are significantly more inclined to reference concerns related to sexuality than those who support the policy. Among those in receipt of the (homo)sexuality treatment, the increase in the probability of citing concerns related to the treatment condition is 4.4 percentage-points: an 83 per cent elevation vis-à-vis the baseline of individuals who express support. Sexuality terms are both significantly more likely to be cited when the sexuality treatment factor is present but even more so for those who oppose surrogacy. This suggests that concerns over sexuality and homonegativity are triggered by the experimental manipulation that, subsequently, serves as the mediating mechanism that drives respondents’ overall opposition to the policy.

The lower panels in analyse the propensity of respondents to refer to concerns regarding the potential transactional nature of gestational surrogacy by assignment to the parasocial contact treatment factors. The predicted means exhibited in the lower left-hand panel do not evince any divergence in respondents’ transactional concerns. Individuals exposed to the ordinary/civilian couple are equally likely (4.4 per cent) to voice transactional issues compared to those assigned to the celebrity couple (4.5 per cent). What is evinced, however, is that independent of exposure to the parasocial treatment factor, those opposed to surrogacy were significantly more inclined to cite transactional concerns in the self-reported rationale for their preferences. The lack of significant effects between the parasocial treatment factor values is noteworthy as it suggests that any inimical effects of celebrity use of surrogates on support for the practice is not the result of cues regarding the potential for economic inequalities and/or exploitation by individuals with a greater pool of resources.

Discussion

Homonegative prejudices significantly influence public support for gestational surrogacy. The illustrative example of the Pete Buttigieg case, where speculation alone resulted in salient critical public commentary of gay men's reliance on surrogacy, is not an isolated case. In this article, I present the results of a pre-registered factorial survey experiment to understand to what extent both homonegative prejudices and parasocial contact can shape public attitudes towards gestational surrogacy. Empirically, the findings illustrate that homonegative biases have a significant, negative causal effect on support for the policy. Exploratory tests of the conditional nature of this effect show that the inimical effect is present among both men and women, as well as among social conservatives and social liberals. The causal effect of exposure to parasocial contact in the form of celebrity surrogacy commissioning does little to shape public preferences.

On average and vis-à-vis the control condition, the effect is close to zero. When comparing differences between treatment conditions, however, I find that when parasocial contact is interacted with the sexuality of the couple, the results evince that these primes can, in fact, have significant asymmetric effects when the couple is comprised of individuals of the same (positive effect) or opposite (negative effect) sex.

Beyond the experimental design, the paper innovates by using quantitative text analysis to understand the underlying causal mechanisms at play. The experimental set up in survey experiments assumes that researcher-led manipulations in characteristics drive changes in output measures but testing whether individuals’ own reasoning is influenced by treatment conditions, the missing link in the causal chain, is difficult. I attempt to isolate treatment-induced variation in self-reported rationales for respondents’ preferences by leveraging a quantitative text analysis of open-ended survey responses. Congruent with the homonegative penalty in support for surrogacy, I also observe that treatment allocation induced a significant uptake in reasoning focused concretely on themes related to sexuality, particularly among those opposed to the policy. This ancillary analysis provides increased causal purchase to the experimental design and provides a concrete test of the underlying biases that treatment primes.

The findings of this pre-registered experimental study have significant implications. First, the study has implications how we understand homonegative dispositions in society. In the UK, a county which has enjoyed access to equal marriage laws for close to a decade, I demonstrate that homonegativity remains a significant prejudice that shapes individuals’ views towards concrete public policies. When policy innovations that seek to respond to public needs, in this case increasing (involuntary) infertility rates, the public is, on average, opposed to these reforms when non-heterosexual individuals are among the beneficiaries. Policymakers who like to keep their finger on the pulse of public opinion when deciding on which side of a debate to invest their political capital would do well to remember that doing so should be done with caution given that the pulse of public opinion can often mask prejudices that lead to the continuation of social exclusion and systemic inequalities. The results also speak to pro-surrogacy activists and campaigners. The mixed and asymmetric effects of celebrity examples (conditioned by sexuality) are particularly important. Campaigners seeking to sway public opinion on certain issues often rely on both celebrity endorsements and/or celebrity examples of the benefits of policy reform. In the case of understanding support for surrogacy, however, our results suggest that such efforts that focus on heterosexual couples (by far the largest community reliant on surrogacy) are likely to play no role and, if anything, may even be detrimental to the cause.

Replication material

Supporting data and replication materials for this article can be accessed on the Harvard Dataverse at: https://dxoi.org/10.7910/DVN/PDOXJD

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at seminars at the University of Reading and the University of Southampton. I am grateful to Daniel Devine, Jessica Smith, Will Jennings, Michal Grahn, John Boswell, Rafael Mestre, Matt Ryan, Paolo Spada, Alberto López and Roosmarijn de Geus for their helpful comments in revising iterations of the paper.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (5.3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte

Dr. Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte is an Assistant Professor in Quantitative Political Science in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Southampton. He received his PhD in Political Science from King's College London.

Notes

1 Ethical approval for experiment was provided by the University of Southampton’s Faculty Ethics Committee (ID: 64315). A pre-analysis plan was registered on the Open Science Framework and is available for consultation at: https://osf.io/x45gk/?view only=58624fdabd4a449b89f10bf2ecf5ef8e.

2 Both (Andrews, Citation1988) and (Sherwin, Citation1992) are critical of the interpretation of the seemingly unnatural nature of a women’s decision to not being a parent, arguing that such a view undermines the feminist view of women wielding independent agency over their life.

3 Whilst this evidence challenges the narrative of exploitation of racial inequalities domestically, it is worth noting that the potential for this exploitation is still present in the transnational setting.

4 Given the devolved competences related to adoption within the UK nations, same-sex adoption was not legalized in Scotland until 2009.

5 Ayoub and Garretson (Citation2017) empirically expand upon this theory leveraging cross-national variation in mass media density and press freedom – which facilitate access to a media diet that exposes individuals to LGBT+ content – correlates with a significant rise in positive attitudes towards non-heterosexual individuals.

6 Parker and Daley were selected as celebrity examples given both are familiar household names in the UK, both tend to enjoy widespread popular support (Figure A5), and neither has been associated with any salient scandals. Research from the US demonstrates that feelings towards queer individuals are not negatively influenced by issues of “respectability politics” in the form of deviations from heteronormative norms of relationships (Jones, Citation2022). Nevertheless, Daley’s relationship with his spouse is an example of a same-sex marriage that, as far as I am aware, does not deviate from the heteronormative norm in another salient way other than that of the individuals’ (shared) gender.

7 Partisanship, measured via retrospective vote recall, significantly influences support for surrogacy (see Figure A13) and conditions the effects of treatment (Figure A14).

References

- Abou-Chadi, T., & Finnigan, R. (2019). Rights for same-sex couples and public attitudes toward gays and lesbians in Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 52(6), 868–895. doi:10.1177/0010414018797947

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Alrababa’H, A., Marble, W., Mousa, S. A., & Siegel, A. A. (2021). Can exposure to celebrities reduce prejudice? The Effect of Mohamed Salah on Islamophobic Behaviors and Attitudes. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1111–1128. doi:10.1017/S0003055421000423.

- Andrews, L. B. (1988). Surrogate motherhood: The challenge for feminists. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 16(1-2), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-720X.1988.tb01053.x

- Arzheimer, K. (2015). Strange bedfellows: The Bundestag’s free vote on pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) reveals how Germany’s restrictive bioethics legislation is shaped by a Christian Democratic/New Left issue-coalition. Research and Politics, 2(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015601130

- Arzheimer, K. (2020). Secular citizens, pious MPs: Why German attitudes about genetic testing are much more permissive than German laws. Political Research Exchange, 2(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2020.1765693

- Austin, E. W., van de Vord, R., Pinkleton, B. E., & Epstein, E. (2008). Celebrity endorsements and their potential to motivate young voters. Mass Communication and Society, 11(4), 420–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430701866600

- Ayoub, P., & Garretson, J. (2017). Getting the message out: Media context and global changes in attitudes toward homosexuality. Comparative Political Studies, 15(8), 1055–1085. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0010414016666836

- Bondi, M., & Scott, M. (2010). Keyness in texts. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Bromfield, N. F. (2016). ‘Surrogacy has been one of the most rewarding experiences in my life’: A content analysis of blogs by U. S. Commercial Gestational Surrogates. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 9(1), 192–217. https://doi.org/10.3138/ijfab.9.1.192

- Bruce-Hickman, K., Kirkland, L., & Ba-Obeid, T. (2009). The attitudes and knowledge of medical students towards surrogacy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 29(3), 229–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610802712926

- Busby, K., & Vun, D. (2010). Revisiting the handmaid’s tale: Feminist theory meets empirical research on surrogate mothers. Canadian Journal of Family Law, 26(1), 13–93. https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/can-j-fam-l/vol26/iss1/3/

- Costa, P. A., Pereira, H., & Leal, I. (2015). ‘The contact hypothesis’ and attitudes toward same-sex parenting? Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(2), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178014-0171-8

- Crawshaw, M., Blyth, E., & van den Akker, O. (2012). The changing profile of surrogacy in the UK – Implications for national and international policy and practice. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 34(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2012.750478

- Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., & Caughey, D. (2018). Information equivalence in survey experiments. Political Analysis, 26(4), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.9

- Desai, S., & Jena, A. B. (2016). Do celebrity endorsements matter? Observational study of BRCA gene testing and mastectomy rates after Angelina Jolie’s New York Times editorial. British Medical Journal, 355(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6357.

- Dotti Sani, G. M., & Quaranta, M. (2020). Let them be, not adopt: General attitudes towards gays and lesbians and specific attitudes towards adoption by same-sex couples in 22 European countries. Social Indicators Research, 150(1), 351–373. doi:10.1007/s11205-020-02291-1

- Driessen, S. (2022). Look what you made them do: Understanding fans’ affective responses to Taylor Swift’s political coming-out. Celebrity Studies, 13(1), 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2021.2023851

- Elberse, A., & Verleun, J. (2012). The economic value of celebrity endorsements. Journal of Advertising Research, 52(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-52-2-149-165

- Engelhardt, H., & Prskawetz, A. (2004). On the changing correlation between fertility and female employment over space and time. European Journal of Population, 20(1), 35–62. doi:10.1023/B:EUJP.0000014543.95571.3b

- Engeli, I., Green-Pedersen, C., & Thorup Larsen, L. (2012). Morality politics in Western Europe. Parties, agendas and policy choices. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Engeli, I., Green-Pederson, C., & Larsen, L. T. (2013). The puzzle of permissiveness: Understanding policy processes concerning morality issues. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(3), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.761500

- Erdogan, Z. B. (1999). Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 37–41. doi:10.1362/026725799784870379

- Feinberg, A. (2021). Tucker Carlson faces backlash over homophobic comments about Pete Buttigieg’s paternity leave. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/tucker-carlson-pete-buttigieg-homophobia-paternity-leaveb1939258.html.

- Finseras, H., & Kotsadam, A. (2017). Does personal contact with ethnic minorities affect anti-immigrant sentiments? Evidence from a field experiment. European Journal of Political Research, 56(3), 703–722. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12199

- Goldstein, D. (2022). Opponents call It the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill. Here’s what it says. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/18/us/dont-say-gaybill-florida.html.

- Guetto, R., Luijkx, R., & Scherer, S. (2015). Religiosity, gender attitudes and women’s labour market participation and fertility decisions in Europe. Acta Sociologica, 58(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699315573335

- Happer, C., & Philo, G. (2013). The role of the media in the construction of public belief and social change. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v1i1.96

- Horton, D., & Richard Wohl, R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

- Ioverno, S., Carone, N., Lingiardi, V., Nardelli, N., Pagone, P., Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Simonelli, A., & Baiocco, R. (2017). Assessing prejudice toward two-father parenting and two-mother parenting: The beliefs on same-sex parenting scale. Journal of Sex Research, 55(4-5), 654–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1348460

- Jones, P. E. (2022). Respectability politics and straight support for LGB rights. Political Research Quarterly, 75(4), 935–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129211035834

- Klüver, H. (2021). The effect of social influences on electoral outcomes: Evidence from a natural experiment. EPSA 2021 Conference Proceedings.

- Kosenko, K. A., Binder, A. R., & Hurley, R. (2016). Celebrity influence and identification: A test of the Angelina effect. Journal of Health Communication, 21(3), 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1064498

- Latham, S. R. (2020). The United Kingdom revisits its surrogacy law. Hastings Center Report, 50(1), 6–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1076

- Levine, H., Jorgensen, N., Martino-Andrade, A., Mendiola, J., Weksler-Derri, D., Mindlis, I., Pinotti, R., & Swan, S. H. (2017). Temporal trends in sperm count: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Human Reproduction Update, 26(6), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmx022

- Lutz, W. (2006). Fertility rates and future population trends: Will Europe’s birth rate recover or continue to decline? International Journal of Andrology, 29(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00639.x

- Magni, G., & Reynolds, A. (2021). Voter preferences and the political underrepresentation of minority groups: Lesbian, gay, and transgender candidates in advanced democracies. Journal of Politics, 83(4), 1199–1215. https://doi.org/10.1086/712142

- Mascarenhas, M. N., Flaxman, S. R., Boerma, T., Vanderpoel, S., & Stevens, G. A. (2012). National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: A systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLOS Medicine, 9(12), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001356

- Matysiak, A., Sobotka, T., & Vignoli, D. (2021). The great recession and fertility in Europe: A subnational analysis. European Journal of Population, 37(1), 29–64. doi:10.1007/s10680-020-09556-y

- Merivaki, T., & Mann, C. (2019). Beyonce—Taylor Swift effect? Impact of online voter registration on voting. APSA 2019 Conference Proceedings.

- Miller, P. R., Flores, A. R., Haider-Markel, D. P., Lewis, D. C., Tadlock, B., & Taylor, J. K. (2020). The politics of being “Cait”: Caitlyn Jenner. Transphobia, and Parasocial Contact Effects on Transgender-Related Political Attitudes. American Politics Research, 48(5), 622–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X20906460

- Mousa, S. (2020). Building social cohesion between Christians and Muslims through soccer in post-ISIS Iraq. Science, 369(6505), 866–870. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb3153

- Noar, S. M., Willoughby, J. F., Myrick, J. G., & Brown, J. (2014). Public figure announcements about cancer and opportunities for cancer communication: A review and research agenda. Health Communication, 29(5), 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.764781

- Philips, A. (2022). Florida’s law limiting LGBTQ discussion in schools, explained. The Washington Post.

- Poote, A. E., & Van Den Akker, O. B. (2009). British women’s attitudes to surrogacy. Human Reproduction, 24(1), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/den338

- Porterfield, C. (2021). Pete Buttigieg reveals he and husband Chasten are parents. Forbes.

- Putnam, R. D., & Campbell, D. (2010). American grace: How religion divides and unites us. Simon; Shuster.

- Rossen, L. M., Ahrens, K. A., & Branum, A. A. (2018). Trends in risk of pregnancy loss among US women, 1990–2011. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 32(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12417

- Rubin, A. M., & Rubin, R. B. (1985). Interface of personal and mediated communication: A research agenda. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 2(1), 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295038509360060

- Schiappa, E., Hewes, D. E., & Gregg, P. B. (2006). Can one TV show make a difference? Will grace and the parasocial contact hypothesis. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(4), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n0402

- Sherwin, S. (1992). No longer patient. Feminism, ethics & healthcare. Temple University Press.

- Teman, E. (2010). Birthing a mother. The surrogate body and the pregnant self. University of California Press.

- Tremellen, K., & Everingham, S. (2016). For love or money? Australian attitudes to financially compensated (commercial) surrogacy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 56(6), 558–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12559

- Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J. (2022). Who wins the UK lavender vote? (Mostly) labour. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 10(3), 388–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2020.1838304

- Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., & McMillan, F. (2022). “Protect the women!” trans-exclusionary feminist issue framing and support for transgender rights. Policy Studies Journal. Online First, https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12484

- van den Akker, O., Fronek, P., Blyth, E., & Frith, L. (2016). “This neo-natal ménage à trois”: British media framing in transnational surrogacy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 34(1), 15–27. doi:10.1080/02646838.2015.1106454

- Ventura, R., Rodríguez-Polo, X. R., & Roca-Cuberes, C. (2019). Wealthy gay couples buying babies produced in India by poor womb-women: Audience interpretations of transnational surrogacy in TV news. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(5), 609–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1422947

- Wise, S. (2000). ‘New right’ or ‘backlash’? Section 28, moral panic and ‘promoting homosexuality’. Sociological Research Online, 5(1), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.452

- Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press.