?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Scholars link the electoral success of right-wing populist parties to a programmatic crisis of representation for mainstream parties, which arguably do not put their voters’ most important issues on the agenda. We have little knowledge about whether these two assumptions hold: To what extent is there a low agenda-responsiveness of mainstream parties, and in how far is their agenda-responsiveness related to the electoral success of right-wing populist parties in Europe? We conceptualize the programmatic crisis of representation as a lack of mainstream party agenda-responsiveness due to dwindling linkage, changing lines of political conflict, and the tension between responsiveness and responsibility. We develop a novel measure of issue-based agenda-responsiveness comparing voters’ most important problems with salient issues in party manifestos. For 109 elections in 26 member states of the European Union (EU) from 2004 to 2019, we find no lack of issue-based agenda-responsiveness between mainstream parties and average citizens, but a lower degree of responsiveness towards the so-called ‘losers of globalization’, especially compared to ‘winners of globalization’. This lower responsiveness, however, is not systematically related to the electoral success of right-wing populist parties whose mobilization contexts are arguably more complex.

Introduction

Right-wing populist parties (RWPPs) are considered a threat to liberal democracy and pluralist values. In recent decades, they have made substantial electoral gains across Europe challenging the existing balance of power in European party systems. They are present in national parliaments, the European Parliament, and have even assumed governing responsibility in some countries. Against this background, scholars identify ‘the crisis of representation (…) at the root of any populist, anti-institutional outburst’ (Laclau, Citation2005, p. 137). Where mainstream parties fail to represent, populist parties can successfully mobilize supporters (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2019). This seeming lack of representation has sparked an ever-growing body of literature on party responsiveness and party-voter congruence in Europe (e.g., Ibenskas & Polk, Citation2022; O’Grady & Abou-Chadi, Citation2019). Results on the degree and drivers of party responsiveness for European countries are mixed not least due to problems with measuring the concept beyond ideological congruence between parties and public opinion. We know there is a mismatch between (certain groups of) voters and their representatives (e.g., Rosset & Stecker, Citation2019; Traber et al., Citation2022), but, surprisingly, there has been less attention on whether RWPPs in Europe thrive electorally in this context, let alone from a cross-country and longitudinal perspective. While some insightful case studies exist (e.g., van Kessel, Citation2011 on the Netherlands), there are only few large-scale cross-country and over time comparisons (e.g., Castanho Silva, Citation2019; Elsässer & Schäfer, Citation2018; van Kessel, Citation2015). Therefore, this article asks: To what extent is there a low agenda-responsiveness of mainstream parties, and in how far is their agenda-responsiveness related to the electoral success of right-wing populist parties in Europe? In doing so, we provide a systematic analysis of the thesis that mainstream parties’ poor responsiveness has opened opportunities for right-wing populist success in Europe.

Based on a threefold conceptualization of the ‘crisis of representation’ – dwindling linkage (van Biezen & Poguntke, Citation2014), changing lines of political conflict (Kriesi et al., Citation2006), and the tension between responsiveness and responsibility (Mair, Citation2009) – we define responsiveness as agenda-responsiveness (Alexandrova et al., Citation2016) or thematic congruence between voters and parties. This conceptualization combines insights from party research, representation research and political sociology that often stand disconnected. We link this to literature on populism that acknowledges this programmatic crisis of representation with mainstream parties ‘missing or ignoring the issues that their voters would like to see on the public agenda’ (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2019, p. 8). In this context in Europe, especially RWPPs may mobilize support (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2019).Footnote1

Against this theoretical background, our aims are threefold: First, we do not have a demand side perspective on (populist) radical right voters and do not want to uncover the determinants of right-wing populist success, which others have done comprehensively (e.g., Arzheimer, Citation2009; Rooduijn, Citation2015). Here, the main attitudinal factor is nativism (Ivarsflaten, Citation2008; Mudde, Citation2007). We are interested in the understudied relationship between poor responsiveness by mainstream parties and the electoral success of RWPPs. We test this relationship not for ideological congruence, i.e., policy positions on the left-right axis, but for thematic congruence, i.e., policy priorities for different voter groups on a variety of issues. This considers the multidimensionality of political competition and the distribution of views among citizens (Kübler & Schäfer, Citation2022, p. 4). We cannot only say whether RWPPs thrive in a context of incongruence, but with regard to which topics.

Second, we develop a new measure of this salience-based agenda-responsiveness between voters and parties at the aggregate level. The index is based on an issue salience approach comparing voters’ most important problems with electoral programmes (similar logic Traber et al., Citation2022).Footnote2 This approach does not only allow us to go beyond existing measures that focus on policy positions on the left-right scale (e.g., Costello et al., Citation2012; Dalton, Citation2017) and oftentimes overestimate representation (Kübler & Schäfer, Citation2022, p. 4). We can also more directly measure an essential part of responsiveness, while others capture related (recent exception Kübler & Schäfer, Citation2022), yet different concepts such as trust in political parties, satisfaction with democracy (van Kessel, Citation2015) or external efficacy (Elsässer & Schäfer, Citation2018).

Finally, we take a longitudinal cross-sectional approach, investigating the relationship between low agenda-responsiveness of mainstream parties and the electoral success of RWPPs in 109 elections in 26 member states of the European Union (EU) from 2004 to 2019 using data from the Eurobarometer (European Commission, Citation2020) and Manifesto Project (Volkens et al., Citation2020). This way we can see whether there are general patterns in Europe or more case-specific mobilization contexts.

Notably, we find quite a high degree of issue-based agenda-responsiveness between mainstream parties and average citizens (over time). Yet, our results indicate a lower degree of responsiveness towards so-called ‘losers of globalization’ (Kriesi et al., Citation2006, p. 921), especially when compared to ‘winners of globalization’. The programmatic crisis of representation is more acute for citizens with lower formal education, and who are currently unemployed or have a job as manual workers. This lack of responsiveness is, however, not systematically linked to the success of RWPPs in the member states of the European Union.

Representation, responsiveness and right-wing populism in the European Union

Responsiveness is essential for representative democracy. The Responsible Party Model (RPM) (APSA, Citation1950) holds that ideally parties offer distinct policy programmes, and citizens make an informed vote choice based on their policy preferences. Votes translate to seats in parliament, and ultimately governing responsibility. Governing parties are committed to their policies and try to enact them. They strive to be responsive to what citizens want.

Further, responsiveness is a multi-step process (Powell, Citation2004). Past studies have focused on policy responsiveness, i.e., whether and to what extent the needs of citizens are implemented through policy outputs (e.g., Dalton, Citation1985). Recently, attention has shifted to rhetorical responsiveness (e.g., Hobolt & Klemmensen, Citation2008). Here, parties publicly articulate and signal policy priorities and positions. While policy responsiveness is the last step in the chain of responsiveness, rhetorical responsiveness happens at the beginning. It is essential for substantive representation because parties’ policy priorities and positions need to be articulated publicly first to enter the process of political will-formation. In other words, being responsive in the first step of the RPM is a precondition for policy responsiveness. Parties can be rhetorically responsive in at least two ways: They can respond to changes in political preferences or they can demonstrate agenda-responsiveness, that is ‘the public’s issue priorities are translated into political priorities’ (Alexandrova et al., Citation2016, p. 606). Parties exhibit substantive representation by setting policy priorities and putting issues on the agenda while ignoring others. It is high, when what citizens consider high on their agenda corresponds to what parties prioritize on their agenda. Agenda-responsiveness becomes a precondition for policy responsiveness (Traber et al., Citation2022).Footnote3

There is an ever-growing body of literature on party responsiveness and party-voter-congruence in Europe. Overall, many (e.g., Adams et al., Citation2004; Clark, Citation2014), but not all (O’Grady & Abou-Chadi, Citation2019) find a high degree of responsiveness towards shifts in public opinion. Diverging results are not only due to how responsiveness is measured, but also due to the question of ‘responsiveness to whom?’ (Lupu & Warner, Citation2022; Traber et al., Citation2022). Few studies look at agenda-responsiveness (e.g., Traber et al., Citation2022), and fewer analyze the connection between responsiveness, representation, and the success of populist parties, with mixed results.

While case studies on Austria, the Netherlands and Switzerland attribute the success of RWPPs to mainstream parties’ lack of responsiveness in the policy fields of immigration and cultural integration (Helms, Citation1997; van Kessel, Citation2011, p. 80), a general relationship could not be confirmed (van Kessel, Citation2015). In a study on how the lack of responsiveness towards socio-economically disadvantaged voter groups influences voting for populist parties for 15 European countries, Elsässer and Schäfer (Citation2018) show that people with a lower external efficacy are more likely to vote for RWPPs. Case studies on Latin American and Western European countries identify the lack of responsiveness (Bornschier, Citation2019; Castanho Silva, Citation2019) and representation crises (Betz, Citation2019) as an essential condition for populist success.

But what is this ‘crisis of representation’, how does it relate to poor representation and lack of responsiveness, and why may this be the ideal breeding ground for right-wing populist success? According to Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser populist ideas at the citizen level are ‘a latent demand that must be activated through context and framing’ (Citation2019, p. 7, emphasis in original). Populist parties successfully use well-known frames to activate such ideas and mobilize support in a context of ‘intentional failure of democratic representation’ (Citation2019, p. 7, emphasis in original). In economically developed countries, this failure manifests itself in a programmatic crisis of representation which essentially is a potential lack of agenda-responsiveness by mainstream political parties (Citation2019, p. 8). We follow the authors’ ideational approach defining populism as a set of ideas consisting of a cosmic struggle between the corrupt elite and the pure and homogenous people (Citation2019, p. 3). Populism expresses itself in Europe mainly in the form of a segmented right-wing populism (Bornschier, Citation2019, p. 202). While, of course, also left-wing populism exists in Europe (e.g., Podemos, Syriza), we focus on right-wing populist parties as the protagonists in mobilizing the so-called crisis of representation (Kriesi et al., Citation2008, pp. 18–19).

Mainstream parties and the programmatic crisis of representation

We can identify three interrelated reasons behind the programmatic crisis of representation: dwindling linkage, the tension between responsiveness and responsibility and changing lines of political conflict (Mair, Citation2009, Citation2013). Political parties should be important linkage actors between society and state through collateral organizations such as trade unions. Those tight links promote responsiveness between party elites and party members (Widfeldt, Citation1999, pp. 15–16) providing input of preferences and problems (Andeweg & Farrell, Citation2017, p. 76).

With a steady decline in members in parties and collateral organizations (van Biezen & Poguntke, Citation2014), mainstream parties are losing their important societal roots. This weakening organizational linkage may lead to a decline in responsiveness between mainstream parties and their supporters. The former have responded with forms of direct linkage through mass communication (Tan, Citation2019, p. 80). While this may ensure some responsiveness between parties and the median voter, such instruments including public opinion surveys may create a bias in favour of majorities resulting in poorer representation for certain minorities (Traber et al., Citation2022). Additionally, parties’ ‘catch-all’ strategies focus on the median voter to the detriment of other voter segments.

The second factor is the tension between responsibility and responsiveness (Mair, Citation2009; Citation2013). Responsive political parties ‘sympathetically respond to short-term demands of voters (…)’ (Bardi et al., Citation2014, p. 237). Parties should be responsive to their supporters and to public opinion. Simultaneously, responsible parties honour internal and external commitments (e.g., coalition agreements, trade regimes, international treaties). Coalition agreements can prevent a party from implementing certain election promises; the same applies to binding international law. Parties have always struggled to reconcile responsiveness with responsibility, yet the dilemma has intensified during globalization and supranationalization (Bardi et al., Citation2014, p. 243). Climate change, migration and pandemics are transnational problems. The gap between responsiveness and responsibility is arguably not only becoming larger, but parties also increasingly lose the means to fill it (Bardi et al., Citation2014). Mair (Citation2009, p. 17) attests ‘a growing bifurcation in European party systems between parties which claim to represent but don’t govern and those which govern but no longer represent’. The former tend to be mainstream political parties, the latter populist challenger parties (Karremans & Lefkofridi, Citation2020, p. 273; Mair, Citation2009, p. 17).

Finally, underlying the programmatic crisis of representation are changing lines of political conflict as a result of well-studied structural developments like the educational expansion, secularization, the tertiarization of industry and individual value changes (Kriesi et al., Citation2006, p. 923). The traditional economic left-right divide is increasingly superimposed by a new cultural cleavage, which scholars have assigned different labels to (Hooghe et al., Citation2002; Inglehart, Citation1990; Kriesi et al., Citation2006). Essentially, the ‘more combustible issue of the boundaries of the political community (“who is one of us”) increasingly displaces the re-distributive conflict over policy outputs (“who gets what”)’ (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2008, p. 16).

This new conflict is considered a symptom of globalization (Kriesi et al., Citation2006, Citation2008). Due to the interconnectedness of transnational, supranational and international actors, political competition is becoming more complex, and increasingly focused on the issues of political integration, migration, and cultural demarcation (Bornschier, Citation2010, p. 420; Kriesi et al., Citation2006, p. 926). This conflict forms new groups of so-called ‘losers and winners of globalization’. The ‘winners’ include entrepreneurs and skilled employees working in sectors adaptive to international competition, and cosmopolitan-minded citizens. The ‘losers’ are people who identify strongly with their national community and/or are employed in traditional sectors, sometimes as low-skilled workers in precarious occupational situations with lower educational attainment (Dancygier & Walter, Citation2015; Kriesi et al., Citation2006, p. 925).

Mainstream parties struggle to fit new political attitudes into their existing ideologies and thus leave a representational gap for new political competitors (Kriesi et al., Citation2006, p. 922). Converging on issues like European integration, mainstream parties tend to provide programmes proposing deeper economic and cultural integration, which benefit the ‘winners of globalization’ (Kriesi et al., Citation2008, p. 16). Consequently, mainstream parties’ agendas are less likely to represent ‘losers of globalization’ and their issue priorities, while – especially RWPPs in Europe are able to mobilize this representational deficit (Bornschier, Citation2019, p. 219; Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2019, p. 9). Overlapping conflicts on the demand side of politics and withdrawing parties on the supply side of politics create a problematic situation for democratic representation, which is further exacerbated by globalization and supranationalization (Mair, Citation2013, p. 115).

Against this background, we first hypothesize that mainstream parties have a lower degree of agenda-responsiveness to the so-called ‘losers of globalization’ (LoG) than the ‘average citizens’ (H1a), and the ‘winners of globalization’ (WoG) (H1b) respectively. LoG differ from both ‘average citizens’ and ‘winners of globalization’ regarding their most important problems, and mainstream parties respond to the latter two rather than the former. We borrow the concept of the mean voter from positional competition theory (Downs, Citation1957) and apply it to issue-based competition. We assume that parties with vote-maximizing strategies, usually mainstream parties and especially catch-all parties, focus on the largest share of the population (‘average citizen’) regarding the distribution of issue priorities as much as they do for policy positions (‘mean voter’).

The pressure of international competition and the flow of labour is high for low-skilled workers with low educational attainment who fear the loss of jobs and driving down of wages (Mudde, Citation2007, pp. 222–224; Rooduijn, Citation2016, p. 53). Given their lower capacity to adapt and higher exposure to negative consequences of economic transformations, they will prioritize economic issues differently compared to average citizens and especially WoG. Research finds evidence for this ‘priority gap’ between low- and high-status citizens with the former prioritizing welfare-state policy issues (Traber et al., Citation2022, p. 355).

At the same time, low-skilled workers are also generally more concerned about immigration than high-skilled workers and more educated individuals (Dancygier & Walter, Citation2015, p. 141). People with a low level of education are more likely to have traditional attitudes viewing such transformation processes more strongly as a problem (Galland & Lemel, Citation2008, p. 175). Due to changing lines of conflict, new cultural issues are established (universalism, equality, environmental protection), for which LoG do not particularly care. This cultural opening of European societies disadvantages LoG, who tend to have a strong national identity.

The aforementioned loss of linkage affects LoG more adversely than the other two groups. The former have less social and cultural capital (Spier, Citation2010, pp. 71–80), which makes it more difficult for them to organize and assert their political priorities. In the past, for example, workers could rely on their unions’ links to social democratic parties to organize their labour policy priorities and preferences. Today’s mainstream parties tend to focus more on average citizens and their priorities, while in the past, they saw themselves as representing different population segments (e.g., industrial workers). The aforementioned instruments mainstream parties use to gauge priorities reinforces the bias against ‘losers of globalization’.

Hypothesis 1a: Mainstream parties exhibit a lower agenda-responsiveness towards the ‘losers of globalization’ than the average citizens.

Hypothesis 1b: Mainstream parties exhibit a lower agenda-responsiveness towards the ‘losers’ than the ‘winners of globalization’.

Poor mainstream agenda-responsiveness and right-wing populist success

In a second step, we link (poor) agenda-responsiveness of mainstream parties to the electoral success of right-wing populist parties. The main driver is the mobilization of nativist attitudes within the electorate (e.g., Ivarsflaten, Citation2008; Rydgren, Citation2008). RWPPs target immigrants as a ‘criminal threat’ (Mudde, Citation2016) thereby emphasizing anti-immigration issues connected to an authoritarian law and order policy. Other factors include the crisis impact (Caiani & Graziano, Citation2019; Moffitt, Citation2015), populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Citation2014), economic and cultural insecurity or (subjective) deprivation (Cena et al., Citation2022; Spruyt et al., Citation2016). At the macro-level, the latter are connected to the ‘losers of modernization’ thesis as an explanatory factor for populist success with varying results (Mudde, Citation2007; Spier, Citation2010).

Finally, a strand of literature connects representation and populism. In this view, populist parties mobilize voters by exploiting allegedly poor responsiveness of mainstream parties as an important discursive frame (Hawkins et al., Citation2020). They portray mainstream parties as the unresponsive elite, and stage themselves as responsive to the people and their common will (van Kessel, Citation2015). In a kind of ‘populist twist’ (Diehl, Citation2019) to representative democracy, populist parties construct an antagonism between a pure, homogenous people that they claim to truly represent, and the mainstream parties as elites who fail to do so (Mudde, Citation2004). In that sense, they ‘simultaneously exacerbate and sidestep the tension between verticality and horizontality’ (Diehl, Citation2019, p. 130) or responsibility and responsiveness. (Right-wing) populist parties emerge in the wake of troubled representative democracy and gain strength when mainstream parties neglect salient issues (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2012, p. 17).

We expect that a lack of mainstream party responsiveness to the ‘losers of globalization’ fosters the electoral success of RWPPs (H2). In line with Bornschier’s ‘segmented populism’ (Citation2019, p. 219), Spier (Citation2010) and Arzheimer (Citation2011) show that workers with a low formal education are more likely to vote for right-wing populist parties. Due to the decrease in linkage between mainstream parties and society, mainstream parties depend more and more on surveys and media reports to gauge public opinion (Poguntke, Citation2000, p. 265). This focusses on average citizens to the detriment of marginalized population groups (Mair, Citation2013, p. 94). Right-wing populists use this lack of responsiveness and stage themselves as representatives of these groups in particular.

Hypothesis 2: The lower the agenda-responsiveness of mainstream parties to the ‘losers of globalization’ in a country, the higher the share of votes for right-wing populist parties in that country.

Data and methodology

Case selection

We investigate mainstream agenda-responsiveness and RWPP electoral success in 109 elections in 26 member states of the European Union from 2004 to 2019.Footnote4 First, we classify both right-wing populist and mainstream parties in these countries. Based on van Kessel’s qualitative classification of populist parties in Europe from 2000 to 2013 (van Kessel, Citation2015), and supplemented with information from other studies (e.g., Leininger & Meijers, Citation2021, for the full list see Online Appendix A.1), we distinguish RWPPs based on their ideological orientation. Populism is a gradual phenomenon, and parties can lose their populist status over time (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2019, p. 5).Footnote5

Mainstream parties are conceptualized in different ways. Some classify mainstream parties as large, electorally dominant party families situated in the centre (Meguid, Citation2005), while others refer to their coalition potential (Abedi, Citation2004) or nicheness (Meyer & Miller, Citation2015). The difficulty with these conceptualizations is that many populist parties are now electorally dominant and in government (e.g., FPÖ), new parties have emerged that do not necessarily fit all categories (e.g., Greens in Germany), and measurements based on thematic or positional distance fail to classify moderate populist parties correctly (e.g., M5S) (Moffitt, Citation2022, p. 388). In line with Moffit, we argue that the label mainstream parties is a discursive act used to mobilize voters. This discursive act is used by mainstream parties to exclude other parties (the ‘pariahing’ Moffitt, Citation2022, p. 389). Populist parties equally use it to exploit their mobilization context of the ‘corrupt elite’ (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2019, p. 8). Mainstream becomes a label, used by populists, for the corrupt, non-responsive elite (often also ‘established parties’). Therefore, we classify all non-populist parties in the sample as mainstream.Footnote6

The 26 EU member states share similar political and economic influences within a common supranational system of governance. Concurrently, there are country differences in agenda-responsiveness and right-wing populist success. Populism has been prevalent in Western Europe since the 1970s, but it became electorally successful only in the 1990s and in the European Union as a whole in the twenty-first century (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, p. 42). Our investigation period therefore runs from 2004 (the year of the EU’s Eastern enlargement) to 2019. The period ends in 2019 because of the political impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The units of observation are national elections. Because we do not have balanced observations for every year in our time span, we use pentadic time intervals in the descriptive analysis (see also Zons, Citation2015, p. 923, for details, see Online Appendix A.2).

Data and operationalization

We estimate the demand side salience of issues within the electorates of the EU using the ‘Most Important Problem’ (MIP) variable from Eurobarometer surveys (European Commission, Citation2020). Response options are closed lists, which enhances the consistency of answers over time and observations, but also limits them. For example, ‘European integration’ is not a response option in the MIP variable. This limits our analysis because agenda-responsiveness on the issue of European Integration may influence RWPP success. Online Appendix A.3 displays response items we used.

The supply side issue salience in election manifestos, and the vote share of RWPPs are calculated using data from the Manifesto-Project (Volkens et al., Citation2020), the most comprehensive dataset for analyzing election programmes (Somer-Topcu & Zar, Citation2014, p. 886).

Our dependent variable is the vote share RWPPs received at national elections. We have two main independent variables: The degree of agenda-responsiveness of mainstream parties towards average citizens and towards ‘losers of globalization’. In a first step, we measure issue salience in the electorate and the mainstream parties. In the manifesto project, issue salience is measured as the share of quasi-sentences of the whole manifesto that any issue category receives (Budge, Citation2001, p. 76). We operationalize issue salience in the electorate as the mean share of each issue category in responses to the MIP question. The same is done for issue salience for ‘losers and winners of globalization’. The higher the percentage share, the greater the salience of an issue. We operationalize thematic congruence in three variants of ‘many-to-many congruence’ (Golder & Stramski, Citation2010, pp. 95–97) by comparing the mean share of issue priorities of several population groups (average voters, ‘losers’ and ‘winners’) with the saliences mainstream parties attribute to these issues.

Agenda-responsiveness is measured as the difference between the most salient issues in the electorate (‘losers of globalization’ respectively) and the most salient issues in the manifestos of mainstream parties in their respective national elections. Our index of agenda-responsiveness is based on the index of programmatic dissimilarity originally developed by Hennl and Franzmann (Citation2017), which goes back to Duncan and Duncan (Citation1955), to compare party programmes across parties and time. We use this measure to calculate ‘programmatic dissimilarity’ between the electorates and the election manifestos. A value of 100 implies total agenda-responsiveness, while a value of 0 implies no agenda-responsiveness. For each national election, we calculate three configurations of our agenda-responsiveness measure: first agenda-responsiveness between mainstream parties and average citizens, second agenda-responsiveness between mainstream parties and LoG and third agenda-responsiveness between mainstream parties and WoG. The formulas for agenda-responsiveness between the electorates and the mainstream parties are:

A more detailed notation is in Online Appendix A.4.

stands for the congruent proportion of salience between the mean saliences in the electorates (SW ‘mean voters’, SWL ‘losers’, SWW ‘winners’) and the saliences in the election programmes of mainstream parties (SP). The following numbers indicate responsiveness to the different groups:

average voters,

globalization losers and

globalization winners.

indicates the index of the respective thematic category and

each mainstream party within a country.

We identified LoG and WoG via two demographic characteristics. Kriesi et al. conceptualize the ‘losers’ as people working in traditional industrial sectors threatened by globalization with a low educational attainment and a strong nationalist identity (Citation2006, Citation2008). Others also characterize them as older men with a low educational level and low social status (Betz, Citation1994, p. 156; Lachat & Dolezal, Citation2008, p. 265). For individuals, however, education and occupational class describe their potential to deal with globalization. A high level of education enables an adaptive and mobile response to structural change (Teney et al., Citation2014, p. 577). The occupational class shows how susceptible one’s occupational position is to such change. People working in classic blue-collar occupations are particularly threatened by the changes of globalization, while white-collar or other high-skilled individuals in competitive sectors tend to benefit from globalization (Walter, Citation2010, p. 410). The group of ‘losers’ is not to be equated with all RWPP voters. Research has shown that the electorates of RWPPs are more heterogeneous than a simplistic configuration of blue-collar workers with low education (Mudde, Citation2016; Rooduijn, Citation2018). However, people who are unemployed or manual workers and people with low formal education have a higher probability to vote for a right-wing populist party (Spier, Citation2010, p. 270f.).

For the two components, education and occupational class, we use the Eurobarometer items ‘Age when finished full-time education’ and the ‘Respondent Occupation Scale’ as proxy-variables to classify individuals as LoG or as WoG. All individuals with a low level of formal education, and who are currently unemployed or have a job as manual workers are identified as LoG. Individuals with a high level of formal education, and who are white-collar workers or managers are identified as WoG. As levels and duration of education vary between European countries, we estimated education in the context of the respective country. Here, we assign the value ‘low education’ to individuals if their respective education duration is located in the lower quartile of the country distribution and the label ‘high education’ for the higher quartile of the country distribution (see Online Appendix A.5).

For this measure to be valid, we link the salient issues in election programmes with the most important problems in the electorate. To achieve this, we have used the common policy areas ‘Economic policy’, ‘Law and order’, ‘Labour policy’, ‘Foreign and security policy’, ‘Welfare state Policy’, ‘Education Policy’, ‘Environmental Policy’ and ‘Immigration’ (Alexandrova et al., Citation2016; Klüver & Spoon, Citation2016). Issues that could not be classified in any of the categories are assigned to a residual category. ‘Foreign policy’ had to be excluded from the analysis because the Eurobarometer included this issue only until 2011. Online Appendix A.6 displays an overview of matched categories and the result of our intercoder reliability test.

For our regression analyzes, we use the following control variables: As economic controls, we include the gross-domestic product per capita in euro (Eurostat, Citation2020a), the total rate of unemployment (Eurostat, Citation2020c) and the harmonized inflation rate (Eurostat, Citation2020b). We control for immigration by including the inflow of immigrants per year as a share of the total population (OECD, Citation2020). The disproportionality of the party system is measured by Gallagher’s least squares disproportionality index (Gallagher & Mitchell, Citation2005, p. 603). The age of democracy is measured as the number of years since the last significant change in the respective regime has taken place (Marschall & Gurr, Citation2020, p. 17). To measure the fragmentation of the party system, the effective number of parties (ENP) is used as an indicator (Laakso & Taagepera, Citation1979). Additionally, parties’ programmatic similarity is included based on the Nicheness index by Meyer and Miller (Citation2015, p. 262). We also include RWPP age to control for individual establishment processes. Finally, we include the ratio of LoG as a control variable.

To account for RWPPs’ most important ideological traits, we did robustness checks that only analyze the connection between congruence in the issue domains immigration and law and order with the success of RWPPs. There is also no statistically significant effect for both issue domains (see Appendix A.9.4).

Empirical results

Agenda-responsiveness in the European Union

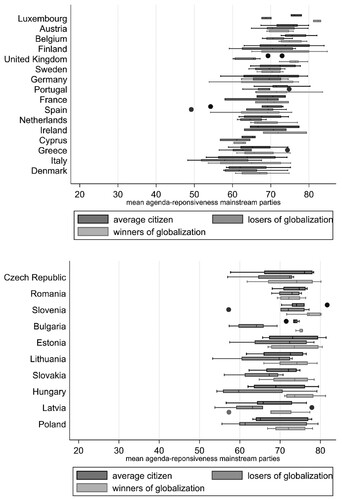

First, we turn to the descriptive analysis of agenda-responsiveness.Footnote7 (a, b) shows the degree of agenda-responsiveness across different countries, Western Europe on the left, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) on the right. First, we see interesting differences between agenda-responsiveness of mainstream parties to average citizens (dark grey), to WoG (light grey) and to LoG (medium grey) that confirm our hypotheses 1a and 1b: The mean agenda-responsiveness to average citizens is 70.62 with a minimum of 53 and a maximum of 84. The responsiveness to LoG is lower with a mean of only 67 (min. 48, max. 80). The responsiveness to WoG is the highest with a mean of 71.66 (min. 54, max. 85).

In other words, on average, mainstream parties share the highest degree of similarity in issue priorities with WoG even higher compared to average citizens, while LoG share the lowest degree of similarity with mainstream parties.

Second, there are no significant differences (t-test, p = 0.256) between mean agenda-responsiveness towards average citizens in CEE (mean 71.50) and Western Europe (mean 70.04). The same is true for agenda-responsiveness towards LoG (t-Test, p = 0.756). The mean in Western Europe is 66.54; the mean in CEE is 66.97. Agenda-responsiveness towards WoG is significantly higher in CEE than Western Europe (t-test, p = 0.024, mean in Western Europe 70.59, in CEE 73.28).

The highest level of agenda-responsiveness (average citizens) can be found in Luxembourg (mean 76.54), closely followed by Belgium (mean 76.51) and Slovenia (mean 75.02). The lowest level of agenda-responsiveness towards average citizens is observable in Italy (mean 63.76), followed by Cyprus (mean 64.57) and Denmark (64.68). The highest values of agenda-responsiveness towards LoG show Romania (mean 72.28) and Austria (mean 72.07). The lowest values appear in Italy (57.93), followed by Cyprus (mean 60.82). The highest levels of agenda-responsiveness towards WoG are again in Luxembourg (mean 82.24) and Slovenia (mean 77.15), while the lowest values appear in Cyprus (mean 62.18) and Italy (mean 64.72).

Overall, mainstream parties are most responsive to WoG followed by average citizens and then only LoG. Across all three groups, they are especially responsive in Belgium, Luxembourg and Slovenia, while they are relatively unresponsive in Cyprus, Denmark and Italy. There are, however, a few interesting exceptions. In Ireland, mainstream parties display a higher responsiveness towards ‘losers’ as well as towards ‘winners’ compared to average citizens. Ireland has one of the highest shares of LoG compared to the whole population (about 10 per cent, see Online Appendix A.5) which may be an electoral incentive for mainstream parties to be more responsive towards them. Furthermore, the country’s very liberal economic policies may be beneficial for WoG (Riain, Citation2018). In Spain, Cyprus and Romania, mainstream parties are most responsive towards average citizens, but at the same time, they are more responsive towards LoG than towards WoG.

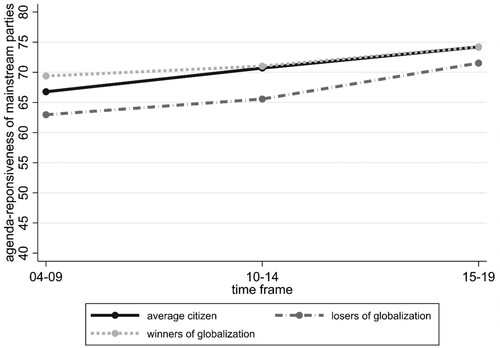

We find a similar pattern, when turning to agenda-responsiveness over time (). The observable gap between ‘winners’, average citizens and ‘losers’ remains consistent in size over time. Quite surprisingly given the notion of an ever-worsening crisis of representation, we see a steady increase of agenda-responsiveness towards all voter groups from 2004 until 2019. This indicates an improvement of representation for recent years. Furthermore, the gap between the groups seems to close from 2015 to 2019. This may be a result of the ending financial crisis in Europe.

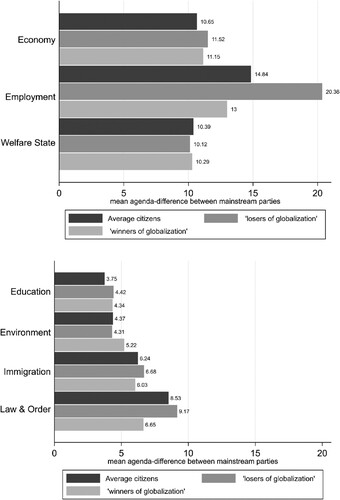

We now turn to the analysis of agenda-responsiveness in the different policy domains. (a, b) displays the degree of dissimilarity between mainstream parties and the three groups of voters on economic issues and socio-cultural ones. Here it is important to note that higher values indicate higher dissimilarity (i.e., lower levels of responsiveness).

Figure 3. (a/b) Mainstream party agenda-responsiveness in economic issues and socio-cultural issues.

We see two relevant findings. First, again, mainstream parties overall are least responsive to ‘losers of globalization’. This is the case in five of the seven issue areas examined. For two issue areas ‘losers’ are slightly better represented compared to the other two groups of voters (welfare state and environment), although the differences are not significant. The greatest differences between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ are found in the areas of ‘Law & Order’ and ‘Employment’ (a difference of 7.36 per centage points). This makes sense because our group of LoG is composed of blue-collar workers in vulnerable industries or individuals who are without employment. The low share of responsiveness is especially troublesome for LoG, as employment issues are their most important ones. However, in most policy fields, the difference is not as large as expected.

Second, main drivers of low responsiveness are in fact traditional economic issues and not issues of the new cultural dimension, like immigration, environment and law and order. This is surprising, as many scholars tie the success of (right-wing) populist parties to the emergence of this new salient conflict dimension (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Bornschier, Citation2010; Kriesi, Citation2014). Our observation fits with recent research which links the support for RWPPs to deprivation experiences and changes in economic structure (Burgoon et al., Citation2019; Rodrik, Citation2018).

Overall, based on the descriptive analysis, we conclude that the programmatic crisis of representation understood as agenda-responsiveness does not tend to exist for average citizens and WoG. Mainstream party agenda-responsiveness to average citizens and WoG as a key element of substantive representation is high over time and across countries. At the same time, agenda-responsiveness to LoG is lower. Their policy priorities are less well represented by mainstream parties in their election programmes than those of average citizens and ‘winners of globalization’. This confirms our initial hypotheses (H1a and H1b) and is in line with existing scholarly assumptions on (not) representing ‘losers of globalization’ (Grande et al., Citation2012; Kriesi, Citation2014).

Agenda-responsiveness and right-wing populist success

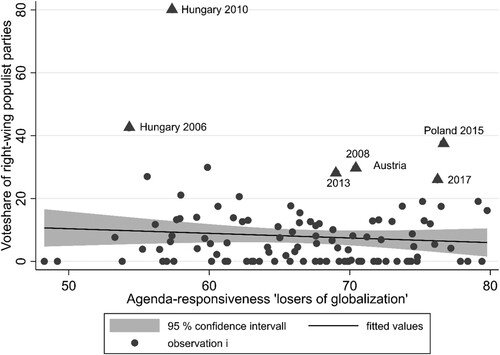

Turning first to the descriptive relationship between a low level of agenda-responsiveness towards ‘losers of globalization’ and the electoral success of RWPPs (H2), shows a weak negative correlation (r = −0.093). There are many observations that have a right-wing populist vote share of 0. However, most of these observations also exhibit a high degree of agenda-responsiveness. Some indicate a high level of agenda-responsiveness and, at the same time, a high right-wing populist vote share. These are in particular observations in Austria (in 2008, 2013, 2017). Several observations have a (very) high share of right-wing populist votes, and show low mainstream party agenda-responsiveness towards LoG: Hungary in 2006 (42.5 per cent) and 2010 (80.06 per cent) as well as Poland in 2005 and 2011. The reverse is true for Slovenia in 2009 or Germany in 2013 with a low right-wing populist vote share and a high degree of agenda-responsiveness.

Figure 4. Mainstream party agenda-responsiveness to the ‘losers of globalization’ and right-wing populist success.

The regression results () confirm this. We build up our models in six steps. With each stage, the model is extended by a group of control variables. We do not find any statistically significant correlation between a low level of agenda-responsiveness towards ‘losers of globalization’ and the electoral success of RWPPs. We therefore reject H2.

Table 1. Regression of mainstream party agenda-responsiveness towards the ‘losers of globalization’ on right-wing populist success.

We have a time-series cross-section design (TSCS) with national elections in different countries at different points in time. While this allows for causal inferences beyond simple time-series or cross-sectional designs (see Fortin-Rittberger, Citation2015, p. 392), the conclusions drawn here are not generalizable beyond the 25 member states from 2004 to 2019. The national elections are nested in a specific country context and are affected by a temporal path dependence. That is, elections at time t0 are always influenced by elections in the past (Wooldridge, Citation2016, p. 427). The data structure is unbalanced with a varying number of observations in the different years due to varying election dates. To estimate the time dependence of observations, a balanced panel is preferred (Wooldridge, Citation2016, p. 468), and we therefore, estimate observations using chronological election numbers (see also Zons, Citation2016, p. 1211).

Due to our unbalanced data structure, we found proof of autocorrelation. Thus, we include lagged dependent variables and estimate additional models using panel corrected standard errors (Beck & Katz, Citation1995). Our data revealed signs of heteroscedasticity. Therefore, we estimate country clustered standard errors in each model. We analyze the data using fixed effect models because, despite homogeneous case selection, country-specific heterogeneity is high, and we are interested in the time-varying aspects of agenda-responsiveness and the electoral success of RWPPs. Our decision is also confirmed by the Durbin-Wu-Hausman test (see Online Appendix A.8). As robustness checks, we estimated pooled OLS and random effect models as well as different sample configurations (e.g., Western Europe vs. CEE) which confirm our original results (Online Appendix A.9.1 & A.9.2).

Discussion and conclusion

Many researchers take a ‘crisis of representation’ as given and view a corresponding lack of representation by mainstream parties as the mobilization context for successful populist parties (e.g., Taggart, Citation2002; van Kessel, Citation2015). Conceptualizing such a programmatic representation crisis caused by dwindling linkages, changing lines of conflict, and the tension between responsiveness and responsibility, we proposed a new measure of responsiveness beyond positional congruence. Using a salience-based approach, we investigated agenda-responsiveness of mainstream parties to detect a possible gap between their issue priorities and those of average citizens, ‘winners’ and ‘losers of globalization’.

Such shared issue priorities are the first essential step in the process of responsiveness, and contrary to common perception (Hayward, Citation2012; Laclau, Citation2005; Mair, Citation2013), we did not detect a universal ‘crisis of representation’ with regard to mainstream parties’ agenda-responsiveness. First, the degree of agenda-responsiveness is relatively high for average citizens and ‘winners of globalization’ across most EU countries and elections in the past 15 years. Second, contrary to the narrative of ever-worsening representation, agenda-responsiveness is steadily rising. What we did detect, however, is that mainstream parties are systematically less responsive to ‘losers of globalization’ than they are to average citizens and ‘winners of globalization’ when it comes to shared issue priorities. Surprisingly, this is especially the case for economic rather than cultural issues.

Overall, ‘losers of globalization’ are left more in the void than others. Not least, this tells us something about how well our democracies provide (equal) representation for all of their citizens. While this is of course problematic in and of itself, it is not systematically related to the electoral success of RWPPs across Europe. RWPPs do not automatically thrive on poor mainstream party agenda-responsiveness. This finding is very well in line with previous research into the link by van Kessel (Citation2015), even though he operationalizes responsiveness differently.

More substantially, this has implications for democratic theory, specifically for the narrative of a crisis of representation as a universal mobilization context for the populist right in Europe. While it may well be the case that disenchanted voters support RWPPs, the individual country and electoral context, as well as path dependencies in each party system are essential to explain the varying success of RWPPs throughout Europe. In some cases, we did find a relationship (e.g., Hungary 2006, Germany 2013, Poland 2010). Yet, in many others, we did not. A case in point is Austria, which has one of the highest levels of agenda-responsiveness by mainstream parties, but also one of the strongest right-wing populist parties. As an old and electorally successful populist party, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) may build up sufficient competitive pressure in the party system to force mainstream parties to be more responsive. Here, future research could conduct in-depth case studies for party systems with successful populist parties over longer time periods such as Austria, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands or Poland.

What our results also clearly show is that – albeit being a vital part of representation – agenda-responsiveness is not the be-all and end-all of representation. Poor agenda-responsiveness as a sign of representation in crisis is rooted in the Responsible Party Model and the assumption of rational, policy-oriented voting behaviour. Ultimately, forms of symbolic representation and the subjective feeling of (not) being represented (Brader, Citation2005, p. 388; Kinski, Citation2021, p. 33) may be decisive especially when it comes to right-wing populist mobilization strategies. Very recent research has started to investigate these mechanisms (Vik & de Wilde, Citation2022). In the end, representation, its crisis and right-wing populist success are multi-dimensional and complex.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.4 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, and John Erik Fossum, Elena García-Guitián and Thomas Poguntke for their helpful feedback at the ECPR Virtual General Conference 2021. The authors are thankful to Pauline Marquardt and Aaron Schlütter for their assistance in data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data for this article can be accessed via Taylor and Francis.

These data were partially derived from the following resources available in the public domain:

Manifesto Project data: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/datasets.

Eurobarometer data: https://www.gesis.org/en/eurobarometer-data-service/search-data-access/data-access.

Notes

1 This mobilization context exists not only for right-wing populist parties, whose ideological profile centres on nativism. We focus on them because of their electoral success in Europe, and because of mixed results in how far they claim issues and positions that mainstream parties ignore (Plescia et al., Citation2019; Kübler & Schäfer, Citation2022).

2 We acknowledge that MIP not always accurately measures the prominence of issues, and changes in MIP mentions may be unrelated to responsiveness for some policy domains. However, for quantitative analyses, this is the best option to capture citizens’ policy priorities (Jennings & John, Citation2009; Spoon & Klüver, Citation2014).

3 While we focus on thematic congruence between parties and citizens, it is important to note that parties do not only prioritize issues because their voters find them important. They also react to issues articulated by other parties. This interplay forms the party system agenda, which in turn influences the issue priorities each individual party articulates (Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Citation2010, pp. 260–261).

4 Due to missing values, Malta is excluded from all analyses; Cyprus is only part of the descriptive analysis. Croatia is not part of the analyses because it has only been an EU member since 2013.

5 We did not include any extreme parties in the dataset. Those parties do show common characteristics with populist parties, but they differ in their relationship to democracy (e. g. Golden Dawn in Greece; Pappas, Citation2019, p. 65).

6 We also calculated our measurements using a mainstream party definition based on party families. See Online Appendix A.9

7 For further descriptive overviews, including agenda-responsiveness for the start of our observation period, see Online Appendix A.7.

References

- Abedi, A. (2004). Anti-political establishment parties: A comparative analysis. Routledge.

- Adams, J., Clark, M., Ezrow, L., & Glasgow, G. (2004). Understanding change and stability in party ideologies: Do parties respond to public opinion or to past election results? British Journal of Political Science, 34(4), 589–610. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123404000201

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Alexandrova, P., Rasmussen, A., & Toshkov, D. (2016). Agenda responsiveness in the European council: Public priorities, policy problems and political attention. West European Politics, 39(4), 605–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1104995

- Andeweg, R., & Farrell, D. M. (2017). Legitimacy decline and party decline. In C. van Ham, J. J. A. Thomassen, K. Aarts, & R. B. Andeweg (Eds.), Myth and reality of the legitimacy crisis: Explaining trends and cross-national differences in established democracies (pp. 76–94). Oxford University Press.

- APSA. (1950). Foreword. American Political Science Review, 44(3), v–ix. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1950996

- Arzheimer, K. (2009). Contextual factors and the extreme right vote in Western Europe, 1980–2002. American Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00369.x

- Arzheimer, K. (2011). Electoral sociology - who votes for the extreme right and why - and when? In D. Art, K. Arzheimer, T. Bar-On, J.-Y. Camus, S. François, T. Grumke, U. Heß-Meining, S. de Lange, M. Mares, & M. Meznik (Eds.), The extreme right in Europe: Current trends and perspectives (pp. 35–50). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Bardi, L., Bartolini, S., & Trechsel, A. H. (2014). Responsive and responsible? The role of parties in twenty-first century politics. West European Politics, 37(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887871

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082979

- Betz, H.G. (1994). Radical right-wing populism in Western Europe. Springer.

- Betz, H.-G. (2019). Populist mobilization across time and space. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), Routledge studies in extremism and democracy: Vol. 42. The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis (pp. 181–201). Routledge.

- Bornschier, S. (2010). The new cultural divide and the two-dimensional political space in Western Europe. West European Politics, 33(3), 419–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402381003654387

- Bornschier, S. (2019). Populist success in Latin America and Western Europe: Ideational and party-system-centered explanations. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), Routledge studies in extremism and democracy: Vol. 42. The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis (pp. 202–237). Routledge.

- Brader, T. (2005). Striking a responsive chord: How political ads motivate and persuade voters by appealing to emotions. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 388–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00130.x

- Budge, I. (2001). Theory and measurement of party policy positions. In I. Budge, H.-D. Klingemann, A. Volkens, J. Bara, & E. Tanenbaum (Eds.), Mapping policy preferences: Estimates for parties, electors, and governments, 1945-1998 (pp. 75–90). Oxford University Press.

- Burgoon, B., van Noort, S., Rooduijn, M., & Underhill, G. (2019). Positional deprivation and support for radical right and radical left parties. Economic Policy, 34(97), 49–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiy017

- Caiani, M., & Graziano, P. (2019). Understanding varieties of populism in times of crises. West European Politics, 42(6), 1141–1158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1598062

- Castanho Silva, B. (2019). Populist success: A qualitative comparative analysis. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), Routledge studies in extremism and democracy: Vol. 42. The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis (pp. 279–293). Routledge.

- Cena, L., Roccato, M., & Russo, S. (2022). Relative deprivation, national GDP and right-wing populism: A multilevel, multinational study. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2636

- Clark, M. (2014). Does public opinion respond to shifts in party valence? A cross-national analysis of Western Europe, 1976–2002. West European Politics, 37(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.841067

- Costello, R., Thomassen, J., & Rosema, M. (2012). European parliament elections and political representation: Policy congruence between voters and parties. West European Politics, 35(6), 1226–1248. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.713744

- Dalton, R. J. (1985). Political parties and political representation: Party supporters and party elites in nine nations. Comparative Political Studies, 18(3), 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414085018003001

- Dalton, R. J. (2017). Party representation across multiple issue dimensions. Party Politics, 23(6), 609–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815614515

- Dancygier, R. M., & Walter, S. (2015). Globalization, labor market risks, and class cleavages. In P. Beramendi, S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt, & H. Kriesi (Eds.), The politics of advanced capitalism (pp. 133–156). Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Diehl, P. (2019). Populist twist: The relationship between the leader and the people in populism. In D. Castiglione, & J. Pollak (Eds.), Creating political presence: The new politics of democratic representation (pp. 118–144). The University of Chicago Press.

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper & Row.

- Duncan, O. D., & Duncan, B. (1955). A methodological analysis of segregation indexes. American Sociological Review, 20(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.2307/2088328

- Elsässer, L., & Schäfer, A. (2018). Unequal representation and the populist vote in Europe. Paper Prepared for the Workshop “Political Equality in Unequal Societies”, Villa Vigoni.

- European Commission, B. (2020). Eurobarometer 86.2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13467

- Eurostat. (2020a). GDP per capita in PPS. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tec00114/default/table?lang=en

- Eurostat. (2020b). HICP - inflation rate. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/product?code=tec00118

- Eurostat. (2020c). Total unemployment rate. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/tps00203

- Fortin-Rittberger, J. (2015). Time-series cross-section. In H. Best, & C. Wolf (Eds.), The sage handbook of regression analysis and causal inference (pp. 387–408). Sage.

- Gallagher, M., & Mitchell, P. (2005). The politics of electoral systems. OUP.

- Galland, O., & Lemel, Y. (2008). Tradition vs. Modernity: The continuing dichotomy of values in European society. Revue Française De Sociologie, 49(5), 153–186. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfs.495.0153

- Golder, M., & Stramski, J. (2010). Ideological congruence and electoral institutions. American Journal of Political Science, 54(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00420.x

- Grande, E., Kriesi, H., Dolezal, M., Helbling, M., Hoglinger, D., Hutter, S., & Wuest, B. (2012). The transformative power of globalization and the structure of political conflict in Western Europe. In H. Kriesi (Ed.), Political conflict in Western Europe (pp. 3–35). Cambridge University Press.

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Mortensen, P. (2010). Who sets the agenda and who responds to it in the Danish parliament? A new model of issue competition and agenda-setting. European Journal of Political Research, 49(2), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01897.x

- Hawkins, K. A., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2019). Introduction: The ideational approach. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), Routledge studies in extremism and democracy: Vol. 42. The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis (pp. 1–24). Routledge.

- Hawkins, Kirk A, Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal, & Andreadis, Ioannis. (2020). The Activation of Populist Attitudes. Government and Opposition, 55(2), 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.23

- Hayward, J. (2012). The crisis of representation in Europe. Taylor and Francis.

- Helms, L. (1997). Right-wing populist parties in Austria and Switzerland: A comparative analysis of electoral support and conditions of success. West European Politics, 20(2), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389708425190

- Hennl, A., & Franzmann, S. T. (2017). The effect of manifesto politics on policy change. In S. E. Scarrow, P. D. Webb, & T. Poguntke (Eds.), Organizing political parties: Representation, participation, and power (pp. 259–284). Oxford University Press.

- Hobolt, S. B., & Klemmensen, R. (2008). Government responsiveness and political competition in comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 41(3), 309–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006297169

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2008). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. J. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310

- Ibenskas, R., & Polk, J. (2022). Party responsiveness to public opinion in young democracies. Political Studies, (4), 919–938. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321721993635

- Inglehart, R. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton University Press.

- Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Comparative Political Studies, 41(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006294168

- Jennings, W., & John, P. (2009). The dynamics of political attention: Public opinion and the queen's speech in the United Kingdom. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 838–854. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00404.x

- Karremans, J., & Lefkofridi, Z. (2020). Responsive versus responsible? Party Democracy in Times of Crisis. Party Politics, 26(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818761199

- Kinski, L. (2021). European representation in EU national parliaments. Springer Nature.

- Klüver, H., & Spoon, J.-J. (2016). Who responds? Voters, parties and issue attention. British Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 633–654. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123414000313

- Kriesi, H. (2014). The populist challenge. West European Politics, 37(2), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887879

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2006). Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 921–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2008). Globalization and its impact on national spaces of competition. In H. Kriesi, E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, & T. Frey (Eds.), West European politics in the age of globalization (pp. 3–22). Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Kübler, M., & Schäfer, A. (2022). Closing the gap? The populist radical right and opinion congruence between citizens and MPs. Electoral Studies, 80, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102527

- Laakso, M., & Taagepera, R. (1979). “Effective” number of parties: A measure with application to West Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 12(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041407901200101

- Lachat, R., & Dolezal, M. (2008). Demand side: Dealignment and realignment of the structural political potentials. In H. Kriesi, E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, & T. Frey (Eds.), West European politics in the age of globalization (pp. 237–266). Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso.

- Leininger, A., & Meijers, M. J. (2021). Do populist parties increase voter turnout? Evidence from over 40 years of electoral history in 31 European democracies. Political Studies, 69(3), 665–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720923257

- Lupu, N., & Warner, Z. (2022). Affluence and congruence: Unequal representation around the world. The Journal of Politics, 84(4), 276–290. https://doi.org/10.1086/714930

- Mair, P. (2009). Representative versus responsible government. https://www.mpifg.de/pu/workpap/wp09-8.pdf

- Mair, P. (2013). Ruling the void: The hollowing of Western democracy. Verso Trade.

- Marschall, G. M., & Gurr, T. R. (2020). POLITY5: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800-2018. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

- Meguid, B. M. (2005). Competition between unequals: The role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success. American Political Science Review, 99(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051701

- Meyer, T. M., & Miller, B. (2015). The niche party concept and its measurement. Party Politics, 21(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812472582

- Moffitt, B. (2015). How to perform crisis: A model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Government and Opposition, 50(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.13

- Moffitt, B. (2022). How do mainstream parties ‘become’ mainstream, and pariah parties ‘become’ pariahs? Conceptualizing the processes of mainstreaming and pariahing in the labelling of political parties. Government and Opposition, 57(3), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.5

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Mudde, C. (2016). Populist radical right parties in Europe today. In J. Abromeit, Y. Norman, G. Marotta, & B. M. Chesterton (Eds.), Transformations of populism in Europe and the Americas: History and recent tendencies (pp. 295–307). Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2012). Populism and (liberal) democracy: A framework for analysis. In C. Mudde, & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or corrective for democracy? (pp. 1–26). Cambridge Univ. Press.

- OECD. (2020). Migration, available under: https://data.oecd.org/migration/permanent-immigrant-inflows.htm#indicator-chart, as consulted: 02.07.2020.

- O’Grady, T., & Abou-Chadi, T. (2019). Not so responsive after all: European parties do not respond to public opinion shifts across multiple issue dimensions. Research & Politics, 6(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/20531680198913

- Pappas, T. S. (2019). How to distinguish populists from non-populists? In T. S. Pappas (Ed.), Populism and liberal democracy (pp. 40–78). Oxford University Press.

- Plescia, C., Kritzinger, S., & de Sio, L. (2019). Filling the void? Political responsiveness of populist parties. Representation, 55(4), 513–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2019.1635197

- Poguntke, T. (2000). Parteiorganisation im Wandel: gesellschaftliche Verankerung und organisatorische Anpassung im europäischen Vergleich. Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Powell, G. B. (2004). The chain of responsiveness. Journal of Democracy, 15(4), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2004.0070

- Riain, SÓ. (2018). Tracing Ireland’s ‘liberal’ crisis and recovery. In O. Parker, & D. Tsarouhas (Eds.), Building a sustainable political economy. Crisis in the eurozone periphery: The political economies of Greece, Spain, Ireland and Portugal (pp. 31–50). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rodrik, D. (2018). Populism and the economics of globalization. Journal of International Business Policy, 1(1), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-0001-4

- Rooduijn, M. (2015). The rise of the populist radical right in Western Europe. European View, 14(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12290-015-0347-5

- Rooduijn, M. (2016). Closing the gap? A comparison of voters for radical right-wing populist parties and mainstream parties over time. In T. Akkerman, S. L. de Lange, & M. Rooduijn (Eds.), Extremism and democracy. Radical right-wing populist parties in Western Europe: Into the mainstream? (pp. 53–69). Routledge.

- Rooduijn, M. (2018). What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties. European Political Science Review, 10(3), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773917000145

- Rosset, J., & Stecker, C. (2019). How well are citizens represented by their governments? Issue congruence and inequality in Europe. European Political Science Review, 11(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000043

- Rydgren, J. (2008). Immigration sceptics, xenophobes or racists? Radical right-wing voting in six West European countries. European Journal of Political Research, 47(6), 737–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00784.x

- Somer-Topcu, Z., & Zar, M. E. (2014). European parliamentary elections and national party policy change. Comparative Political Studies, 47(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013488552

- Spier, T. (2010). Modernisierungsverlierer? die Wählerschaft rechtspopulistischer Parteien in Westeuropa. Springer.

- Spoon, J.-J., & Klüver, H. (2014). Do parties respond? How electoral context influences party responsiveness. Electoral Studies, 35, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2014.04.014

- Spruyt, B., Keppens, G., & van Droogenbroeck, F. (2016). Who supports populism and what attracts people to it? Political Research Quarterly, 69(2), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912916639138

- Taggart, P. (2002). Populism and the pathology of representative politics. In Y. Mény, & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 62–80). Springer.

- Tan, A. C. (2019). Members, organizations and performance: An empirical analysis of the impact of party membership size. Routledge.

- Teney, C., Lacewell, O. P., & de Wilde, P. (2014). Winners and losers of globalization in Europe: Attitudes and ideologies. European Political Science Review, 6(4), 575–595. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773913000246

- Traber, D., Hänni, M., Giger, N., & Breuning, C. (2022). Social status, political priorities and unequal representation. European Journal of Political Research, 61(2), 351–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12456

- van Biezen, I., & Poguntke, T. (2014). The decline of membership-based politics. Party Politics, 20(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813519969

- van Kessel, S. (2011). Explaining the electoral performance of populist parties: The Netherlands as a case study. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 12(1), 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2011.546148

- van Kessel, S. (2015). Populist parties in Europe: Agents of discontent? Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vik, A., & de Wilde, P. (2022). Re-conceptualizing feeling represented: A new approach to measure how citizens feel represented through representative claims. Paper prepared for ECPR General Conference, Innsbruck.

- Volkens, A., Lehmann, P., Matthieß, T., Merz, N., Regel, S., Weßels, B., & Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. (2020). The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2020b. Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://doi.org/10.25522/MANIFESTO.MPDS.2020B

- Walter, S. (2010). Globalization and the welfare state: Testing the microfoundations of the compensation hypothesis. International Studies Quarterly, 54(2), 403–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00593.x

- Widfeldt, A. (1999). Linking parties with people? Party membership in Sweden 1960-1994. Ashgate.

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2016). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Zons, G. (2015). The influence of programmatic diversity on the formation of new political parties. Party Politics, 21(6), 919–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813509515

- Zons, G. (2016). How programmatic profiles of niche parties affect their electoral performance. West European Politics, 39(6), 1205–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2016.1156298