ABSTRACT

National surveillance is often insufficient to identify transnational issues. One solution to this problem is to delegate to international organizations (IOs) the power to surveil activity in numerous states simultaneously, acting, in essence, as supranational detectives. When should we expect states to engage in such delegation? This article contends that this will depend on whether sub-state public agencies have acquired the exclusive capacity to surveil that phenomena at the national level. Those that have will actively oppose delegation to preserve the benefits afforded by that exclusivity, thereby reducing the likelihood that an IO is ultimately empowered to perform supranational surveillance. This hypothesis is tested against two case studies in which EU energy and securities regulators contemplated empowering an IO with supranational surveillance powers to detect transnational market abuse. Empirical evidence, drawing on 86 interviews, corroborates that each group’s pre-existing surveillance capabilities impacted their delegation preferences and, in turn, whether delegation occurred. These findings advance our understanding of supranational delegation and the politics of multi-level governance in the EU. Further, they shed empirical light on transnational market abuse, an understudied form of financial crime that hurts consumers, destabilizes prices, and facilitates the movement of illicit funds across borders.

Introduction

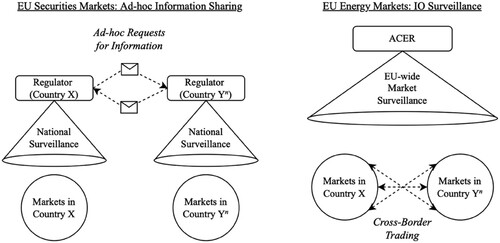

Since the early 2000s, EU securities and energy regulators have faced the same problem: detecting transnational market abuse. This refers to market manipulation and insider dealing perpetrated across borders, a method of international economic crime that cannot be identified through siloed monitoring of national markets (Austin, Citation2017). To address this problem, both sets of regulators have considered delegating supranational surveillance powers to an IO. This came to fruition in the energy sector through the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), which monitors all EU markets to identify suspicious cross-border trading. EU securities regulators, in contrast, continue to monitor their own markets and engage in ad-hoc information-sharing. Why would two sets of regulators, operating in the same states and facing the same problem, engage in such different methods of international cooperation? And, more broadly, when should we expect states to delegate to IOs the power to surveil non-state actors?

Existing theories of supranational delegation have largely ignored this question, focusing instead on IO monitoring of state compliance with international treaties. Further, these theories tend to assume states are unitary actors with fixed preferences, precluding their capacity to explain why delegation decisions may vary across and within issue areas. Missing from these perspectives is consideration of sub-state public agencies and their preferences to support or oppose delegation. These actors may not possess the legal authority to delegate; these decisions often require approval by national or regional legislatures. But in highly technical issue areas such as market surveillance, national regulatory agencies (e.g., Germany’s Federal Financial Supervisory Authority) are key players that independently initiate policy debates, meet with foreign counterparts, provide highly-influential advice to government representatives, and possess many of the resources necessary for delegation to succeed (Martinsen et al., Citation2022). We must, therefore, examine these sub-state actors to explain variation in delegation decisions.

Scholars of public policy and public administration have paid closer attention to regulatory agencies and their incentives to cooperate. It has long been observed that vested interests, such as the desire to protect ‘turf,’ can impede cooperative efforts (Wilson, Citation1989). More recent work has theorized that regulators may welcome cooperation where it improves their capacity to perform their core task or protect their bureaucratic turf (Busuioc, Citation2016; Heims, Citation2019). These perspectives do not, however, seek to explain variation between IO delegation and other institutional forms of cooperation. Further, they implicitly assume that regulators’ conception of their bureaucratic turf, and, as a result, their preference to engage in cooperative efforts, remain fixed.

What these perspectives overlook, I contend, is how the acquisition of a specific capability – exclusive national surveillance power – can alter public agencies’ delegation preferences and, in turn, the likelihood that delegation will occur. This term refers to the exclusive capability to surveil non-state actors within one national jurisdiction, a task that requires substantial resources and technical expertise. Acquiring exclusive national surveillance power will, this article contends, provide public agencies with new (or strengthen existing) anti-delegation incentives, including incentives to maintain control over information and avoid wasting sunk costs. These incentives will lead public agencies to actively oppose delegation even if they believe it is the most effective method of cooperation. Thus, in sum, public agencies’ (non-)acquisition of exclusive national surveillance power (at time T0) impacts their delegation preferences, and, in turn, the likelihood of delegation occurring in the future (T1+).

The hypothesis is utilized to explain why EU securities and energy regulators engage in divergent forms of international cooperation to detect transnational market abuse. Both groups considered delegating surveillance to an IO in similar time periods. They entered these discussions, however, under different circumstances. Namely, numerous EU securities regulators had obtained the exclusive capacity to monitor their own markets. EU energy regulators, in contrast, had not acquired this capability by the time delegation was considered. This article conducts a structured-focused comparison of these cases, drawing on 86 interviews with regulatory practitioners located in 14 countries. The empirical evidence indicates that each group’s (non-)possession of exclusive national surveillance power impacted their delegation preferences and, in turn, whether an IO was empowered to perform pan-European monitoring.

By performing these tasks, this article advances our understanding of delegation and multi-level governance. Unlike theories that assume states are unitary actors with fixed preferences, the perspective outlined here allows us to explain why state delegation decisions may vary within the same issue areas. This perspective also improves upon functionalist theories by explaining why public agencies may oppose delegation even if they believe it is the most functionally appropriate form of international cooperation. Further, this article is, to the author’s knowledge, the first to demonstrate how public agencies’ acquisition of specific capabilities can alter their preference to delegate surveillance to IOs. This insight complements recent insights in public administration (particularly Busuioc, Citation2016) by demonstrating how agencies’ obtainment of specific capabilities can alter their conception of their bureaucratic turf, and, in turn, their preference to delegate tasks to an IO or engage in other institutional forms of cooperation.

By examining these dynamics, we can help shed light on a pervasive public policy issue in the EU. As the next section discusses, European markets are vulnerable to transnational methods of abuse that hurt investors, undermine market confidence, facilitate money laundering, and, in the energy sphere, trigger disruptions to electricity and gas. It is essential, therefore, that we examine how political and historical forces may prevent EU states from engaging in what may be, from a societal perspective, more effective forms of cooperation.

The common problem: transnational market abuse

EU financial markets, where participants trade everything from stocks to commodity derivatives, are highly interconnected. Numerous European exchanges allow investors to simultaneously trade stocks listed in multiple EU states, and it is commonplace to offer derivative products in one state whose value is based on fluctuating assets in another. One can, for example, trade options contracts in Germany whose value is based on the price of an Italian stock (EUREX, Citation2022). Similarly, EU electricity and gas markets and their corresponding derivative products are integrated, the result of a concerted effort over the last few decades to create a single European energy market (Hancher & de Hauteclocque, Citation2010).

As a result, there are ample opportunities within EU financial and energy markets to engage in transnational methods of abuse. This refers to two categories of financial crime: insider dealing and market manipulation. Insider dealing is defined as any attempt to trade financial instruments on inside information (e.g., forthcoming company mergers or undisclosed disruptions to energy supply). Market manipulation encompasses a wide range of actions whose purpose is to mislead others about the supply of and/or demand for a financial instrument. One common method is the ‘pump and dump,’ in which actors artificially pump up the price of securities by spreading false positive information and then sell (dump) at a profit.

Particularly relevant here are methods of abuse that involve multiple markets (cross-market abuse) and/or products (cross-product abuse) in two or more EU member states, i.e., transnational market abuse. One could, for example, seek to manipulate the price of an individual corporate bond trading in the Netherlands to impact the price of an options contract on that bond trading in Belgium. One might also manipulate the price of gas derivatives through trades in multiple national markets to avoid detection. Though the specificities of EU securities and energy markets differ, the fundamental nature and legal definition of their abuse are identical.Footnote1

Also identical is the fundamental practical challenge of identifying transnational market abuse: informational silos. As The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO, Citation1993, p. 3) adeptly summarize, ‘The division of illegal activities among several countries may make [transnational securities fraud] more difficult to detect, particularly since, from a purely domestic point of view, parts of the scheme may appear, or even may be, legal.’ Traditionally, EU securities and energy regulators have engaged in siloed monitoring (or relied upon surveillance performed by trading venues) and exchanged ad-hoc information requests, a system long recognized as slow and inefficient. In recognition of these weakness, both considered empowering an IO to perform pan-European monitoring. This came to fruition in the energy sector via the empowerment of ACER but never went beyond informal discussions amongst securities regulators, who continue to engage in the traditional method of ad-hoc information-sharing (). What we have, in other words, are the same states, facing the same problem in two asset classes, engaging in divergent forms of cooperation. What explains this difference in institutional choice?

Figure 1. The Divergent Modes of Cooperation Used by EU Securities and Energy Regulators.

Note: These depictions are simplified. Some securities regulators continue to rely on the surveillance performed by private trading venues, adding an additional level of intermediation. And, after endowing ACER with pan-European surveillance powers, some energy regulators developed complementary national surveillance capabilities.

Existing perspectives on delegation and regulatory cooperation

Scholars of International Relations (IR) have long sought to understand why states might delegate monitoring tasks to IOs rather than engage in other forms of cooperation. Functionalist theories contend that states will outsource tasks to IOs if the practical benefits outweigh the costs.Footnote2 This perspective has, however, struggled to explain actual delegation patterns, due in part to its failure to consider how self-interest and political forces can override functionalist concerns (Eberlein & Grande, Citation2005). Later research, channeling in part functionalist logic, theorized that states might engage in transgovernmental policy networks rather than cooperate through IOs because such networks are faster, more flexible, and impose fewer sovereignty costs (Raustiala, Citation2002; Slaughter, Citation2004; Vabulas & Snidal, Citation2013). These theories do not explain, however, why states’ delegation decisions may vary when facing the same functional problem.

Other IR scholars have proposed that hegemonic power (Simmons, Citation2001) or the availability of noncompliance victims as monitors (Dai, Citation2002) will determine the mode of cooperation utilized by states. The former’s emphasis on the balance of power between hegemons and all other states precludes its capacity to explain variation within regions or issue areas. Dai’s framework proposes that interest alignment between states and victims of non-compliance, in combination with whether those victims can themselves act as monitors, will determine institutional choice. These factors do not vary, however, between EU energy and securities markets, and therefore do not explain the differences we observe. More generally, IR scholarship suffers from a widespread assumption that states are unitary actors with fixed preferences over cooperation forms, undermining its ability to explain why states might engage in divergent forms of cooperation simultaneously.

Other work in (international) political economy, public policy, public administration, and EU politics has, however, relaxed this assumption by examining how sub-state actors’ preferences impact regulatory cooperation. Scholars have long observed that public agencies, as bureaucracies, seek to protect their turf (Wilson, Citation1989). Recent work has added nuance to this literature by theorizing that public agencies may favor cooperation if it enhances the reputational uniqueness they have acquired through the performance of their core tasks (Busuioc, Citation2016). A related line of research contends that agencies are more willing to cooperate when there is high mission overlap and high resource complementarity (Heims, Citation2019). These theories implicitly assume, however, that public agencies’ conception of their core mission, turf, and reputational uniqueness (and, as a result, their preference to cooperate) is fixed. What the literature is missing, I contend, is how these agencies’ acquisition of a specific capability – exclusive national surveillance power – can impact these preferences and, in turn, the likelihood that delegation will occur.

Explaining variation in surveillance delegation

Delegating monitoring tasks to IOs offers numerous potential benefits, including efficiency gains and neutral information production (Abbott & Snidal, Citation1998). Further, performing surveillance at the supranational level may allow IOs to identify transnational connections that would be difficult or impossible to observe through siloed monitoring at the national level. It is not, however, without its risks. Delegation presents the principal-agent problem, in which states (principals) outsource tasks to an IO (agent) they cannot fully control (Hawkins et al., Citation2006). Once empowered, IOs may take on a life of their own, expanding the scope of their responsibilities or acting in contrast to the interests of their principals (Guzman, Citation2013).

Normally, it is the state – represented by the government in power – which possesses the legal authority to decide whether to engage in such delegation. These representatives respond to sub-state interests when making such decisions (Putnam, Citation1988). One particularly influential set of sub-state actors are regulatory agencies. These agencies are technical experts that independently initiate policy debates, develop rules, advise legislative representatives, and, in many cases, take unilateral enforcement actions. As independent and self-interested actors, they can be expected to weigh the costs and benefits of any prospective cooperative arrangement and subsequently seek to influence whether they come to fruition. This may involve lobbying government representatives or engaging in indirect actions to support (e.g., producing complementary research) or hinder (e.g., purposeful sabotage) the cooperative proposals. And in some cases, these proposals may originate with regulators themselves (e.g., via transgovernmental policy forums), thereby allowing them to decide if they are put in front of governmental representatives in the first place. We must, therefore, understand the formation of these sub-state actors’ preferences over cooperation forms to explain variation in state delegation decisions.

To that end, I hypothesize that public agencies’ preference to delegate surveillance to an IO will, all else equal, depend on whether they have previously acquired the exclusive capacity to perform that task at the national level. Those that have will actively oppose delegation to preserve the benefits afforded by that exclusivity, thereby reducing the likelihood that an IO is ultimately empowered to perform transnational monitoring:

The Surveillance Exclusivity Hypothesis

States are less likely to delegate surveillance to an IO where the relevant public agencies possess exclusive national surveillance power.

Intuition and causal mechanism

The exclusive capacity to perform surveillance is powerful. It allows the surveyor to exercise control, act as an informational gatekeeper, and reap the material and ideational benefits afforded by their exclusive monitoring capabilities. Allowing an IO to monitor the same data will, however, sacrifice the benefits afforded by this exclusivity. Further, it may be viewed as a waste of the substantial costs incurred to develop this capability in the first place. Phrased differently, the process of acquiring exclusive surveillance power will provide agencies with new (or strengthen existing) anti-delegation incentives (). These incentives will, the hypothesis anticipates, lead public agencies to actively oppose delegation, thereby reducing the likelihood that an IO is ultimately empowered to perform supranational surveillance.

Table 1. Anti-Delegation Incentives Created or Strengthened by Exclusive National Surveillance Power.

First, the exclusive power to perform national surveillance is a source of internal and external control (Incentives A and B). Internally, it allows public agencies to control their domestic markets, policy priorities, and investigations. That power would be reduced or eliminated if public agencies allow an IO to perform surveillance within their national jurisdictions. An IO might, for example, prioritize certain issues or actors against the public agency’s wishes. Further, an IO’s newfound surveillance capabilities may lead it to ‘mission creep’ into areas outside their original mandate (Barnett & Finnemore, Citation2004), such as commenting on local policies or specific enforcement actions. Externally, public agencies with exclusive surveillance power can act as informational gatekeepers by controlling what data is made available to foreign actors. This may allow them to protect domestic actors from unwanted scrutiny and ‘control the narrative’ about damaging events. These advantages would be eliminated if an IO was empowered to surveil the same data.

In other contexts, an IO might identify events the public agency missed or chose to ignore, creating embarrassing questions about the agency’s competence (or integrity). Further, the IO might use its surveillance powers to ‘name and shame’ public agencies as a means of encouraging them to adopt and/or alter certain policies. An example of this tactic is the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) blacklist. FATF maintains a list of states considered to have weak measures against money laundering and terrorist financing. Empirical work has found that FATF can induce states to change their policies by placing them on this list (Morse, Citation2019).

Further, public agencies with exclusive national surveillance powers may view IO delegation as a threat to their employment, expertise, and funding (Incentives C, D, and E). These concerns reflect bureaucratic organizations’ self-protective tendencies (Wilson, Citation1989). In order to protect themselves, bureaucracies will redefine their goals, use self-promotional rhetoric, and/or seek to expand the scope of their roles and responsibilities (see, e.g., Langevoort, Citation1990). Following these insights, it is anticipated that public agencies will reject IO delegation to protect the material benefits afforded by their exclusive surveillance power. Staff may fear that delegating surveillance will threaten their career prospects. Management, in turn, may be concerned that staff, expertise, and government funding will gravitate toward the IO at their expense.

Public agencies might also view IO delegation as a waste of the sunk costs they have incurred to obtain exclusive surveillance power (Incentive F). Specifically, they may succumb to the ‘sunk cost fallacy:’ the tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment has been made, even if that is economically sub-optimal, to avoid the feeling that the initial investment was wasted (Thaler, Citation1980). For public agencies, these costs include establishing a department with the staff, expertise, and resources necessary to perform surveillance. Further, this task may require the construction of a new, centralized database. The fear of wasting these investments (or allowing other agencies to indirectly free ride on those costs) may provide public agencies with yet another incentive to reject IO delegation.

Finally, public agencies will desire to maintain the ideational benefits afforded by their surveillance powers. One such ideational benefit is prestige (Incentive G). Working for the ‘top’ authority in any one field is prestigious, providing social currency and the perception of having authority (Scott, Citation1989). Another ideational benefit is the perception that the agency oversees their ‘turf,’ i.e., the breadth and depth of their bureaucratic power (Incentive H). Organizations are highly sensitive about this topic, often willing to engage in ‘turf wars’ to preserve their authority (Wilson, Citation1989). U.S. securities and commodities regulators, for example, have engaged in turf wars over the scope of financial instruments falling under their respective jurisdictions (Macey, Citation1994). Delegating surveillance to an IO sacrifices turf by allowing a foreign body to monitor domestic data; in Busuioc's (Citation2016) terminology, it would impede on the ‘reputational uniqueness’ public agencies have acquired through their exclusive surveillance powers. It also suggests there is a ‘higher’ institution governing the same space that is more authoritative/prestigious.

The hypothesis anticipates that these incentives will lead public agencies to actively oppose delegation, reducing, in turn, the likelihood that delegation occurs. There are, of course, other domestic actors such as private firms that may seek to influence this decision (see, e.g., Maggetti, Citation2019). But public agencies are states’ formal subject matter experts and thus in a unique position to comment on whether delegating surveillance would help or hinder what Busuioc (Citation2016) refers to as their core mission. Further, they possess many of the resources necessary to facilitate the implementation of IO-led surveillance and thus, as Martinsen et al. (Citation2022) write with respect to enforcement, ‘are in powerful positions to oppose supranational delegation.’ Public agencies will, for example, likely be responsible for ensuring that private firms report data to a pan-European database, and the IO may seek their technical advice on the design of their surveillance systems. Further, government representatives are likely to share anti-delegation incentives, such as fears of losing control, wasting sunk costs, and concerns about sovereignty. If public agencies reinforce these fears, communicate that delegation would hinder their core mission, or indicate resistance to providing the resources necessary for implementation, governments are unlikely to proceed. And, if the proposal originates amongst public agencies, as it may via transgovernmental policy forums or informal discussions between colleagues, they possess first mover advantage, able to, in effect, veto the initiative before it reaches governmental representatives.

Before proceeding, it is important to note that this causal mechanism is conditioned by the decision-making rules utilized by two or more states to decide on delegation. If delegation requires unanimous agreement, the opposition of one public agency – channeled through their government representatives – may be sufficient to block the initiative. If, alternatively, delegation only requires a simple or qualified majority, this opposition may be overcome by states whose public agencies do not possess exclusive national surveillance power and thus (as theorized here) possess fewer and/or weaker incentives to actively oppose delegation.

Methodology and case selection

To evaluate the hypothesis, this paper conducts a structured-focused comparison of two cases in which a group of public agencies considered delegating surveillance to an IO (George & Bennett, Citation2005). This comparison contains elements of process tracing, in which first-hand accounts and written evidence is used to reconstruct how agencies’ (non-)acquisition of exclusive surveillance led them to actively (support) oppose delegation, impacting, in turn, whether delegation occurred. It also features interviews with regulators not involved in these discussions, who therefore cannot provide first-hand confirmations of their content, but can nevertheless corroborate the presence or absence of anti-delegation incentives.Footnote4 To establish falsifiable thresholds for causal inference, the article utilizes a mix of the ‘hoop’ and ‘smoking gun’ tests (Collier, Citation2011). Here the hoop test is that public agencies with (without) exclusive surveillance power should reject (accept) delegating surveillance to an IO. The smoking gun is evidence of agencies with (without) said power (not) exhibiting and acting upon anti-delegation incentives. Contradicting evidence would suggest the hypothesis is either incorrect or substantially conditioned by other factors.

The universe of cases includes any situation in which public agencies are considering delegating surveillance to an IO. Prior research by the author identified two cases in relation to transnational market abuse. The first case involves EU securities regulators discussing, from approximately 2000-2019, whether they should empower the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) to detect transnational market abuse. The second involves EU energy regulators considering a similar delegation of surveillance power to ACER from 2005-2013. The ESMA proposition, which was revealed to the author via interview and, to the author’s knowledge, never went beyond informal discussions amongst regulators, were concentrated in two periods: 2008–12 and 2018-19. During the first period, at least two EU securities regulators had obtained exclusive national surveillance power. By the time this issue was revisited in the late 2010s, that number had grown to at least seven. In contrast, EU energy regulators had not, according to available data, obtained such power by the time they considered delegating surveillance to ACER. Because the ESMA discussions were disclosed to the author via interview, the selection of cases is purposeful rather than random, and further research on a wider set of (ideally randomly selected) cases will be necessary to fully evaluate the hypothesis’ generalizability.

Case selection, data, and alternative explanations

The cases identified allow for ‘diverse’ selection (Gerring, Citation2008). Here we have two sub-groups depending on whether the relevant public agencies had (sub-group 1: ESMA) or had not (sub-group 2: ACER) acquired exclusive national surveillance power prior to the period of discussion. This set also provides advantages of the most similar method. Namely, each involves attempts by regulators in the same states (EU members) to address the same problem (transnational market abuse) in similar time periods (approximately 2000–2019).

Here it is important to consider whether these cases vary in other characteristics that may constitute alternative explanations. Three possibilities are noteworthy: functional problem, issue salience, and IO institutional design. First, are EU energy and securities regulators dealing with the same functional problem? If detecting transnational market abuse in securities is more complex or requires more local knowledge, perhaps that is why delegation never occurred. This assumption is, however, problematic. Detecting transnational abuse in energy markets requires monitoring millions of orders and transactions per day not just in wholesale electricity and gas, but also derivative contracts in 27 member states (each of which features local idiosyncrasies). And, unlike securities, one must monitor disruptions to the production, storage, and transmission of energy to identify insider trading. Further, factors such as ‘local knowledge’ do not negate the fact that siloed monitoring of national markets precludes the identification of transnational schemes. This problem and the legal definition of abuse are identical in both markets.

Second, one might question whether the issue salience of abuse in each market, i.e., how consequential it is for citizens, differs. If, for instance, energy abuse is less salient, perhaps energy regulators would not feel the need to develop surveillance powers and therefore would not develop and act upon anti-delegation incentives. But it is problematic to assume the abuse of energy is less salient than securities. Energy manipulation directly impacts society, as demonstrated by Enron’s manipulation of California’s electricity markets which caused blackouts for millions of people, ultimately leading voters to recall the state’s governor (McLean & Elkind, Citation2004). Third, scholars have examined how the institutional design of IOs, such as their level of technical capabilities, may (dis-)courage states to provide them with sensitive information (Carnegie & Carson, Citation2019). Here, however, the question is not about ESMA and ACER’s existing technical capabilities but rather whether regulators support providing those capabilities in the first place. Despite the questionable plausibility of these alternatives, the analysis of each case will consider whether empirical data supports their significance.

These cases draw on 86 interviews conducted with practitioners located in London, Paris, Frankfurt, Berlin, Bonn, Milan, Rome, Zurich, Vienna, Oslo, Stockholm, Ljubljana, Amsterdam, The Hague, Toronto, Montreal, Auckland, Anguilla, Istanbul, New York, and Washington, D.C. These interviews, which took place either in person or via phone, were procured through email request and benefited from ‘snowball’ sampling, whereby interviewees help make introductions to other interviewees (e.g., their colleagues). This informal introduction process was important, as energy and securities regulators are hesitant to discuss their surveillance capabilities out of fear that disclosing details could help criminals evade detection. In total, interview requests were sent to 194 individuals, leading to 86 interviews, constituting a 44.3% success rate. One limitation of the EU interview data is its skew toward Northern and Western member states due to differences in response rates, network introductions, and resource constraints. The analysis also draws on reports, requests for comments, and other publications by ESMA, ACER, and informal negotiating forums. And, as discussed in the next two sections, this evidence corroborates that each group’s possession of exclusive national surveillance power (or lack thereof) impacted their preferences and, in turn, whether an IO was empowered to perform transnational surveillance.

Case study 1: ESMA and the surveillance of European equities trading

Most EU states lacked formal prohibitions of insider trading and market manipulation until the 1980s and 1990s (Bach & Newman, Citation2010). European securities exchanges, however, established their own rules against such activity long before. In 1814, for example, English traders spread rumors about the death of Napoléon Bonaparte to manipulate the price of government bonds. The London Stock Exchange deemed this fraudulent, seized their profits, and distributed the proceeds to an unrelated charity (Davis et al., Citation2004). Such detection was the responsibility of European exchanges throughout the twentieth century (Michie, Citation2006, ch. 7).

In the 1990s, however, advances in electronic trading radically altered EU markets and, in turn, the challenge of performing effective surveillance. Broker-dealers and start-ups were now able to create their own electronic markets to compete with traditional exchanges (Gorham & Singh, Citation2009). Most exchanges subsequently demutualized to remain competitive, transitioning from non-profit cooperatives to for-profit corporations. These trends raised substantial oversight concerns. Can private trading venues be relied upon to police their own customers? Interviewees expressed scepticism, best summarized by one former European compliance officer:

When I was working, if I battled with [a large hedge fund] over an instance of manipulation, is that in my commercial interests? No. It was not unheard of for someone on the business side to complain to the CEO about the surveillance activities. It’s not just an optics problem – there’s a big conflict of interest (Interview 14. Corroborated by interviews 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9).

In response, numerous EU securities regulators obtained the exclusive capacity to perform national market surveillance. The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), for example, constructed a proprietary in-house market surveillance system in the late 2000s called ‘SABRE,’ replaced by ZEN in 2011 (Sullivan, Citation2011). Developing this system was no small task; for FY 2011/12, the FCA’s operating costs ran approximately GBP 17 million over budget, due primarily to the costs of developing ZEN (FSA, Citation2012, p. 85). By 2014, ZEN was ingesting data on 13 million trades per day. And, to identify suspicious transactions, the FCA established a dedicated surveillance unit which featured, as of 2017, approximately 25 full-time staff (Interview 9). These staff design algorithms to scan UK markets for abuse and forward suspicious transactions to their enforcement colleagues (Interview 6). The FCA has since replaced ZEN with a new system, the ‘Market Data Processor,’ which allows the Authority to scan 30–35 million transactions per day to detect market abuse (Hoggett, Citation2017). Similar efforts were undertaken by France’s AMF, Germany’s Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin), and the Netherlands Authority for Financial Markets (AFM). Therefore, by the time EU securities regulators considered delegating surveillance powers to ESMA, numerous members of this group had obtained exclusive national surveillance power. And, as anticipated, this provided those regulators with various incentives to reject delegating surveillance to an IO.

Exhibited incentives of EU securities regulators

To delegate [market surveillance] is to make you naked.

– German regulator on the prospect of ESMA performing pan-European market surveillance (Interview 81)

At the time of these discussions, however, at least two EU securities regulators had obtained exclusive national surveillance power. This included the UK’s FCA, which, according to interviewees, possessed and acted upon various incentives to reject delegating surveillance powers to ESMA. Specifically, the FCA exhibits incentives to avoid the loss or reduction of Internal power over domestic market, policy, and investigations (Incentive A); employment (Incentive C); and control over ‘turf’ (Incentive H). As one interviewee directly involved summarized:

[Allocating surveillance power to ESMA] would obviously by more efficient. But national regulators want to maintain sovereignty over their markets … It’s not about efficiency, it’s politics and ingrained interests. Regulators in 28 countries don’t want to lose their jobs. And they want to be able to say that they monitor their own markets (Interview 6, emphasis added).

As a result of these anti-delegation incentives, delegating surveillance power to ESMA never went beyond informal discussions. Rather, MAR widened the scope of private firms required to surveil their own venues and/or traders (European Union, Citation2014, Article 16). But MAR did obligate the Commission to report on potential extensions of its measures by 2019, including ‘the possibility of establishing a Union framework for cross-market order book surveillance in relation to market abuse … ’ (Article 38(d)). Interviewees directly involved in these discussions corroborated that this included consideration of the agency performing cross-border surveillance for at least some types of securities (Interviews 78, 79).

By the time this review took place, numerous additional EU regulators obtained their own surveillance capabilities. And, like the FCA, their representatives exhibit an incentive to avoid the loss/reduction of Internal control over domestic market, policy, and investigations (Incentive A). One example is Germany’s BaFin, which achieved exclusive national surveillance power through its ‘ALMA’ system. This appears to have provided the agency with an incentive to reject allocating surveillance to ESMA: ‘we were against it because we have our own risk-based supervisory approach’ (Interview 81). Interviewees explained that, if ESMA were to perform surveillance, it might not prioritize certain topics important to German supervision. One example is Germany’s automobile sector, which has suffered a series of scandals connected to market abuse and violations of emissions standards (Associated Press, Citation2017). BaFin is highly concerned with such cases, but ESMA may not share this priority. This provides an incentive to reject the allocation of surveillance powers to ESMA so that they can maintain internal control of policy priorities and individual investigations (Interviews 81, 82).

Representatives of France’s AMF corroborated this concern. AMF staff members also expressed reservations about wasting sunk costs (Incentive F). The AMF has invested substantial resources into developing its surveillance capabilities and creating a dedicated department full of expert staff. The idea of allocating similar powers to ESMA is, according to interviewees, difficult, especially ‘when we think of the IT efforts we have put in … ’ (Interview 75). This interviewee also highlighted an incentive to avoid a loss/reduction of expertise (Incentive D):

Some countries want to keep surveillance. Surveillance … gives, allows [sic] authorities to understand what’s going on, to compare business intelligence with other conditions. It allows [us] to defend the marketplace. We would not be so familiar with our exchanges [without it]. It provides a lot of insight that may be good for policy aspects. Outsourcing surveillance to ESMA would deprive AMF of a valuable source of knowledge.

Case study 2: ACER and the surveillance of European energy trading

From the end of World War II to the late 1970s, most European states featured a single, state-run energy supplier (Mez et al., Citation1997). States monopolized energy infrastructure because it was considered an essential component of statehood and had direct ties to security, e.g., nuclear power. In the 1990s, however, EU states initiated widespread privatization to construct a single European energy market (Haverbeke et al., Citation2010). This was facilitated through a series of ‘packages’ legislating increased regulatory harmonization (Gouardères, Citation2019).

The details of these packages are negotiated in part through the European Forum for Electricity Regulation, often referred to as the ‘Florence Process’ due to its biannual meetings in Italy (Eberlein & Grande, Citation2005). One key participant is the Council of European Energy Regulators (CEER), which represents all EU National Regulatory Authorities (NRAs). Another key organization, until recently, was The European Regulators Group for Electricity and Gas (ERGEG), a formal advisory body to the European Commission. The ‘Third Energy Package’ introduced in 2009 established ACER in Ljubljana, Slovenia. ACER effectively replaced ERGEG and was first conceived as a coordinating actor with limited decision-making power. (Hancher & de Hauteclocque, Citation2010).

In the late-2000s, EU energy regulators began debating the potential allocation of market surveillance powers to ACER. Regulators’ primary concern was identifying transnational market abuse in Europe. The origins of this fear laid, however, 5,000 miles away in sunny California. In the early 2000s, Enron manipulated the state’s newly deregulated electricity markets, leading to rolling blackouts and, in turn, a snap election to replace the state’s governor (McLean & Elkind, Citation2004). European regulators were well aware of the California electricity crisis, and an additional scandal closer to home raised fears that EU markets were vulnerable to Enron-like manipulation schemes. In the mid-2000s, E.ON, the German electricity company, was accused of withholding energy production as a means of artificially increasing prices (Chauve et al., Citation2009). The case, which was ultimately settled, raised new concerns about whether EU energy regulators were able to identify and prosecute transnational market abuse.

In response to these concerns, EU regulators began debating the 2011 Regulation on Wholesale Energy Market Integrity and Transparency (REMIT). A European Commission (Citation2010, p. 7) impact assessment determined that EU energy prices were increasingly interconnected, but that siloed surveillance precluded regulators from identifying transnational market abuse: ‘These bids and offers are not easily visible to those charged with market oversight. Even where information can be exchanged between countries, the process is cumbersome and does not lend itself to early and efficient identification of suspicious trading patterns.’

The report details how nefarious actors might engage in transnational market abuse. For example, one might suppress energy capacity in France as a means of manipulating the price of related derivative contracts trading in Germany. Any one exchange performing surveillance would not be able to recognize this scheme. ‘Only by combining knowledge of the market participant’s actions on both the French and German markets, can the market abuse be detected’ (Ibid, 9). In other words, the EU’s siloed system of national surveillance by exchanges was no longer sufficient to oversee what was now an international market for electricity and gas. The proposed solution: empower ACER to perform pan-European surveillance of energy markets.

Empirical evidence indicates that, at the time of this debate, EU energy regulators had not obtained exclusive national surveillance power. A joint fact-finding mission by CESR/ERGEG (Citation2008) found that EU energy regulators largely left the identification of market abuse to their respective energy exchanges.Footnote5 And, for certain contracts, such as over-the-counter gas derivatives, there was often no oversight at all. An economist at the U.K. Office of Gas and Electricity Markets’ (Ofgem) Oversight department confirmed via interview: ‘before ACER, there were no rules, no obligations for firms to report … Some regulators had no experience looking at this stuff’ (Interview 61). One staff member of The Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM), speaking in a personal capacity, confirmed: ‘ … NRAs weren’t doing that yet’ (Interview 62). Surveillance capabilities had yet to be developed, according to interviewees, because energy markets were until recently largely self-regulated (Interviews 62, 63, 80). And, indeed, it was not until 2005 that each member state featured a dedicated NRA, and thus these agencies remained in an early stage of development (Haverbeke et al., Citation2010, p. 406). As anticipated, these regulators neither exhibited nor acted upon anti-delegation incentives. Rather, interview data and written evidence indicates that delegating surveillance to ACER was considered an uncontroversial solution to the problem of detecting transnational market abuse.

Exhibited incentives of EU energy regulators

After identifying faults in the EU’s system of energy market oversight, the Commission requested comments on how best to proceed. ERGEG (Citation2010, p. 7), which represented all EU energy regulators, expressed that EU-level surveillance was necessary: ‘ … ACER should perform ‘central monitoring tasks’ … ’ ERGEG also supported the idea of ACER or another EU-level institution surveilling carbon trading (Ibid, 9-10). Interviewees corroborated that allocating surveillance powers to ACER was viewed as a functional solution rather than a threat. ACER’s Director, Alberto Pototschnig, noted: ‘If you have an internal energy market with cross-border trading is seems almost obvious that you would have some kind of European-wide surveillance of market transactions’ (Interview 27). The aforementioned staff member of the ACM, the Netherlands’ energy regulator, agreed:

So, ACER was there already, it already had a role. And then REMIT came along and I think it was quite logical that because there is coordination work to be done, that ACER would take up the coordination work … it wasn’t too controversial … especially not because not everyone was doing their own surveillance (Interview 62).

This widespread support translated to the successful delegation of surveillance powers to ACER. REMIT, which was unanimously approved, obligates ACER to monitor trading in wholesale energy products to detect market abuse (European Council, Citation2011). Interviewees with direct knowledge of ACER’s work indicated that its supranational vantage point is advantageous: ‘ … if NRAs only looked at their national markets, they would not see the other side because they can’t see the cross-border aspect’ (Interview 28). One German regulator corroborated, ‘ACER can see activity that no one regulator would be able to’ (Interview 80). Thus, in sum, EU energy regulators, when presented with a choice between cooperation forms, supported the delegation of surveillance powers to an IO.

Analysis

EU energy and securities regulators considered delegating supranational surveillance powers to ACER and ESMA, respectively, from approximately 2000–2019. EU energy regulators, relatively new agencies overseeing markets that, until recently, were largely self-governed, had not obtained such powers. Interview data and written evidence (including the statements of their representative body, ERGEG) subsequently indicate that energy regulators supported the delegation of surveillance powers to ACER, leading to its unanimous approval in the European Council.

Numerous EU securities regulators, in contrast, had obtained exclusive national surveillance power by the time delegation was considered. Interviewees familiar with or directly involved in those discussions indicated that they possessed numerous incentives to reject delegation, including fears of losing control, turf, and employment. As a result, the prospect of empowering ESMA never proceeded beyond informal discussions amongst regulators. Together, these cases support the hypothesis that states are less (more) likely to delegate surveillance to an IO where the relevant public agencies (do not) possess the exclusive capacity to perform that surveillance at the national level.

The evidence does not support the aforementioned alternative explanations. Securities regulators directly contradicted the functionalism argument, noting that self-interested motivations fueled opposition despite general agreement that supranational surveillance would be more efficient. Further, energy markets also feature specific characteristics but there is no evidence that this provided regulators with a functional motivation to reject delegation. Nor was there evidence that differences in salience impacted variation in national surveillance capabilities or the decision to delegate. And, finally, the evidence does not support the idea that differences in each IO’s institutional capacity impacted the decision. If true, one would expect it more likely that surveillance be delegated to ESMA, whose budget far outstrips ACER and thus might be better prepared to undertake this function. Yet it is the opposite that occurred.

Conclusion

For many of the world’s most pressing issues, ranging from financial crime to the spread of infectious disease, the primary practical challenge is detection. Siloed monitoring at the national level is insufficient to detect these transnational issues, and thus states must cooperate. There are, however, various forms this cooperation may take. This article has concerned itself with better understanding why states might engage in one type: the delegation of supranational surveillance powers to an IO. This form of cooperation offers certain practical advantages over traditional methods of information-sharing, in which states monitor their own markets and send one another laborious requests for data. Namely, empowered IOs can, by virtue of their supranational vantage point, monitor activity in numerous states simultaneously, thereby allowing them to recognize cross-border connections. It is essential, therefore, that we understand why states may or may not choose to engage in this mode of international cooperation.

We cannot do so, this article has contended, without paying closer attention to the formation of sub-state public agencies’ preferences. These agencies are highly influential interest groups that actively advise governments on their needs and independently engage in policy development through informal forums (e.g., the Florence Process) and transgovernmental networks. They are not, of course, the only group that may seek to influence this decision. But as states’ formal subject matter experts and implementing agents, their active opposition will significantly reduce the likelihood delegation occurs. This is particularly true where discussions of delegation originate amongst public agencies themselves, thereby providing them with the power to veto the initiative before it reaches governmental representatives for formal debate.

This article has subsequently hypothesized that public agencies’ delegation preferences will depend on whether they have obtained the exclusive capacity to perform that task at the national level. Developing this capacity will, the hypothesis contends, provide public agencies with new (or strengthen existing) anti-delegation incentives, leading them to actively oppose the initiative. Thus, public agencies’ acquisition of surveillance power (T0) impacts their delegation preferences and, in turn, the likelihood that an IO will be empowered to perform supranational surveillance (T1+). A comparison of two case studies on EU securities and energy regulators considering the delegation of supranational surveillance powers to IOs, drawing on 86 interviews and documentary evidence, corroborates this expectation.

These insights demonstrate how sequencing effects impact the nature of international regulatory cooperation through preference formation. Here the decision by securities regulators to obtain exclusive national surveillance power – a rational response to domestic challenges at one moment in time – later led them to reject a form of cooperation that they themselves believed was more efficient. Energy regulators who, by chance, had not developed such power exhibited no such resistance. When asked about the difference in cooperation forms, Alberto Pototschnig, ACER’s director, reflected via interview, ‘Maybe we were just lucky, the timing worked in our favour.’ And, indeed, timing is essential. Sequences of events shape political interests, constraining the possibility of certain outcomes while making others more likely (Pierson, Citation2004). We cannot fully understand the form and effectiveness of international cooperation without paying closer attention to these temporal mechanisms.

To that end, there are numerous avenues for future research. First, the hypothesis should be tested against additional cases to assess its generalizability. Scholars might also explore whether public agencies’ acquisition of other exclusive capabilities, such as enforcement or judicial powers, impacts their preference to engage in certain methods of cooperation. We also live in a world of regime complexity. How might the dynamics explored here differ if numerous IOs are available to perform the same delegated task? Exploring these questions would further improve our understanding of EU multi-level governance and, more broadly, the international politics of global detection.

Cited interviews

Interview 3: Exchange Staff, Oxford (5 December 2017)

Interview 4: Surveillance Specialist, London (11 December 2017)

Interview 5: Surveillance Specialist, London (11 December 2017)

Interview 6: Former Regulator, London (9 January 2018)

Interview 7: Lawyer, London (9 January 2018)

Interview 9: Regulatory Professional (2 February 2018)

Interview 11: Exchange Staff, London (2 February 2018)

Interview 14: Consultant, London (1 March 2018)

Interview 27: Alberto Pototschnig, Director of ACER, Oxford (12 June 2018)

Interview 28: Regulatory Professional, Oxford (12 June 2018)

Interview 35: Regulatory Professional, Toronto (11 September 2018)

Interview 51: Regulatory Professional, Washington, D.C. (24 September 2018)

Interview 61: Regulatory Professional, Oxford (28 May 2019)

Interview 62: Regulatory Professional, The Hague (3 June 2019)

Interview 63: Regulatory Professional, The Hague (3 June 2019)

Interview 66: Regulatory Professional, Amsterdam (6 June 2019)

Interview 67: Regulatory Professional, Amsterdam (6 June 2019)

Interview 75: Regulatory Professional, Paris (5 September 2019)

Interview 78: Regulatory Professional, Paris (6 September 2019)

Interview 79: Regulatory Professional, Paris (6 September 2019)

Interview 80: Regulatory Professional, Bonn (9 September 2019)

Interview 81: Regulatory Professional, Frankfurt (10 October 2019)

Interview 82: Regulatory Professional, Frankfurt (10 October 2019)

Interview 86: Regulatory Professional, Oxford (7 February 2020)

Acknowledgements

For their guidance throughout this project, I thank Duncan Snidal and Walter Mattli. I also thank my doctoral examiners, Abraham Newman and Karthik Ramanna, for their extensive feedback on earlier versions. Thank you also to Jack Seddon, Kaisa de Bel, Jeremy Richardson, and three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and helpful suggestions. This article also benefited from comments received at the 2019 European Political Science Association Annual Meeting, 2018 Oxford Political Economy of Finance Conference, and presentations delivered at University College, Nuffield College, and the Rothermere American Institute. Finally, thank you to the interviewees, most of whom prefer to remain anonymous, who kindly agreed to participate in this study. Please note that this article solely represents the views of the author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Miles Kellerman

Miles Kellerman received his PhD in International Relations from the University of Oxford in 2020. His research has previously been published in Regulation & Governance, The Review of International Organizations, and volumes published by Oxford University Press.

Notes

1 The EU Market Abuse Regulation, or MAR, provides common definitions of abuse that apply to both securities and energy products (European Union, Citation2014).

2 For a review of this literature, see Pollack (Citation1997).

3 Note that this does not prevent public agencies from developing complementary national surveillance powers at a later stage (T1+). What we are interested in here is whether public agencies possess exclusive national surveillance power (T-1) prior to the period in which delegation is considered (T0).

4 I thank two anonymous reviewers for bringing attention to this important distinction.

5 Responses were not received from Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Ireland. Subsequent research resulted in no evidence that these countries’ NRAs were performing market surveillance prior to REMIT. The precise capabilities of France’s Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) are unclear. The CRE’s response indicates that it ‘monitors electricity and natural gas transactions between suppliers, traders, and generators … It checks that suppliers, traders, and generators’ offers are consistent with their technical and economic constraints’ (CESR/ERGEG, Citation2008, p. 28). This appears to allude to the more general goal of ensuring that market activity results in the consistent and safe delivery of electricity (i.e., monitoring ‘pricing’). The agency did not respond to the author’s repeated requests for an interview. Neither textual evidence nor interviews with other regulators indicated that the CRE exhibited incentives to reject the allocation of surveillance powers to ACER.

References

- Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (1998). Why states Act through formal international organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002798042001001

- Associated Press. (2017). Did VW’s CEO manipulate markets? German prosecutors are investigating. Los Angeles Times. Available at « https://www.latimes.com/business/autos/la-fi-hy-volkswagen-manipulation-20170517-story.html».

- Austin, J. (2017). Insider trading and market manipulation: Investigating and prosecuting across borders. Edward Elger.

- Bach, D., & Newman, A. L. (2010). Transgovernmental networks and domestic policy convergence: Evidence from insider trading regulation. International Organization, 64(3), 505–528. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000135

- Barnett, M., & Finnemore, M. (2004). Rules for the world: International organizations in global politics. Cornell University Press.

- Busuioc, E. M. (2016). Friend or Foe? Inter-agency cooperation, organizational reputation, and turf. Public Administration, 94(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12160

- Carnegie, A., & Carson, A. (2019). The disclosure dilemma: Nuclear intelligence and international organizations. American Journal of Political Science, 63(2), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12426

- CESR/ERGEG. (2008). Advice to the European commission in response to fact-finding questions of the mandate C.1-C.3 and E.12-E.17’ (Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR) and European Regulators’ Group for Electricity and Gas (ERGEG).

- Chauve, P., Godfried, M., Kovács, K., Langus, G., Nagy, K., & Siebert, S. (2009). The E.ON electricity cases: An antitrust decision with structural remedies. Competition Policy Newsletter, 1, 51–54. ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/cpn/2009_1_13.pdf

- Collier, D. (2011). Understanding process tracing. PS: Political Science & Politics, 44(4), 823–830. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096511001429

- Conceicao, C. (2006). Tackling cross-border market abuse. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 14(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/13581980610644734

- Dai, X. (2002). Information systems in treaty regimes. World Politics, 54(4), 405–436. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2002.0013

- Davis, L., Neal, L., & White, E. N. (2004). The Development of the rules and regulations of the London stock exchange, 1801-1914.

- Eberlein, B., & Grande, E. (2005). Beyond delegation: Transnational regulatory regimes and the Eu regulatory state. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176042000311925

- ERGEG. (2010). European energy regulators’ response to the European commission’s public consultation on “initiative for the integrity of traded energy markets”. European Regulators’ Group for Electricity and Gas.

- ESMA. (2020). ‘Mar review Report’ (European Securities and Markets Authority).

- EUREX. (2022). Equity Options, EUREX. Available at « https://www.eurex.com/ex-en/markets/equ/opt».

- European Commission. (1999). Financial services: Implementing the framework for financial markets: Action plan. European Commission.

- European Commission. (2010). Impact assessment accompanying proposal for REMIT. European Commission.

- European Commission. (2011). Impact Assessment of MAR and CSMAD. European Commission.

- European Council. (2011). Voting result: Regulation of the European parliament and of the council on energy market integrity and transparency. Council of the European Union.

- European Union. (2003). Directive 2003/6/EC of the European parliament and of the council of 28 January 2003 on insider dealing and market manipulation (market abuse). European Parliament and the Council of the European Union.

- European Union. (2014). Regulation No. 596/2014 of the European parliament and of the council on market abuse. Official Journal of the European Union, 57, 1–62.

- FSA. (2012). Annual Report 2011/12. Financial Services Authority.

- George, A. L., & Bennett, A. (2005). The method of structured, focused comparison. In Case studies and theory development in the social sciences (pp. 67–124). MIT Press.

- Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection for case-study analysis: Qualitative and quantitative techniques. In J. Box-Steffensmeier, H. Brady, & D. Collier (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political methodology (pp. 645–684). Oxford University Press.

- Gorham, M., & Singh, N. (2009). Electronic exchanges: The global transformation from pits to bits. Elsevier Science.

- Gouardères, F. (2019). Fact sheets on the European Union. Internal Energy Market, European Parliament. Available at « https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/45/internal-energy-market».

- Guzman, A. (2013). International organizations and the frankenstein problem. European Journal of International Law, 24(4), 999–1025. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/cht061

- Hancher, L., & de Hauteclocque, A. (2010). Manufacturing the EU energy markets: The current dynamics of regulatory practice. Competition and Regulation in Network Industries, 11(3), 307–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/178359171001100304

- Haverbeke, D., Naesens, B., & Vandorpe, W. (2010). European energy markets and the new agency for cooperation of energy regulators. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 28, 403–430.

- Hawkins, D. G., Lake, D. A., Nielson, D. L., & Tierney, M. J. (2006). Delegation under anarchy: States, international organizations, and principal-agent theory. In D. G. Hawkins, D. A. Lake, D. L. Nielson, & D. G. Tierney (Eds.), Delegation and agency in international organizations (pp. 3–38). Cambridge University Press.

- Heims, E. (2019). Why cooperation between agencies is (sometimes) possible: Turf protection as enabler of regulatory cooperation in the European union. In T. Bach, & K. Wegrich (Eds.), The blind spots of public bureaucracy and the politics of Non-coordination (pp. 113–131). Springer International Publishing.

- Hoggett, J.. (2017). Effective compliance with the Market Abuse Regulation - a state of mind. Recent Developments in the Market Abuse Regime Conference. London.

- IOSCO. (1993). Protecting the small investor: Combatting transnational retail securities and futures fraud. International Organization of Securities Commissions.

- Langevoort, D. C. (1990). The SEC as a bureaucracy: Public choice, institutional rhetoric, and the process of policy formulation. Washington & Lee Law Review, 47(3), 527–540.

- Macey, J. (1994). Administrative agency obsolescence and interest group formation: A case study of the SEC at sixty. Cardozo Law Review, 15, 909–949.

- Maggetti, M. (2019). Interest groups and the (Non-)enforcement powers of EU agencies: The case of energy regulation. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 10(3), 458–484. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2019.38

- Martinsen, D. S., Mastenbroek, E., & Schrama, R. (2022). The power of ‘weak’ institutions: assessing the EU’s emerging institutional architecture for improving the implementation and enforcement of joint policies. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(10), 1529–1545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2125046

- McLean, B., & Elkind, P. (2004). The smartest guys in the room: The amazing rise and scandalous fall of enron. Penguin.

- Mez, L., Midttun, A., & Thomas, S. (1997). Restructuring electricity systems in transition. In A. Midttun (Ed.), European electricity systems in transition (pp. 3–12). Elsevier Science Ltd.

- Michie, R. C. (2006). The global securities market: A history. Cambridge University Press).

- Morse, J. C. (2019). Blacklists, market enforcement, and the global regime to combat terrorist financing. International Organization, 73(3), 511–545. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081831900016X

- Pierson, P. (2004). Politics in time: History, institutions, and social analysis. Princeton University Press.

- Pollack, M. A. (1997). Delegation, agency, and agenda setting in the European community. International Organization, 51(1), 99–134. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081897550311

- Putnam, R. D. (1988). Diplomacy and domestic politics: The logic of Two-level games. International Organization, 42(3), 427–460. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300027697

- Raustiala, K. (2002). The architecture of international cooperation: Transgovernmental networks and the future of international Law. Virginia Journal of International Law, 43(1), 1–92.

- Scott, J. C. (1989). Prestige as the public discourse of Domination. Cultural Critique, 12, 145–166. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354326

- Simmons, B. A. (2001). The international politics of harmonization: The case of capital market regulation. International Organization, 55(3), 589–620. https://doi.org/10.1162/00208180152507560

- Slaughter, A.-M. (2004). A New world order. Princeton University Press.

- Sullivan, R. (2011). FSA unveils New market abuse detector. The Financial Times, 7 August 2011.

- Thaler, R. H. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 1(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(80)90051-7

- Vabulas, F., & Snidal, D. (2013). Organization without delegation: Informal intergovernmental organizations (IIGOs) and the spectrum of intergovernmental arrangements. The Review of International Organizations, 8(2), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-012-9161-x

- Wilson, J. Q. (1989). Bureaucracy: What government agencies Do And Why they Do It (1st edition). Basic Books.