ABSTRACT

The free movement of goods is widely believed to be a prime example of the negative integration paradigm. Its defining characteristic is a strong judicial process, fuelled by – and fuelling – litigation, which eclipses the weak(er) political process. The article argues that this dominant narrative is no longer accurate. Based on a new dataset of all Article 34 TFEU cases decided by the CJEU between 1961 and 2020, it shows that goods litigation has been disappearing from the Court’s docket since the mid-1980s. The reasons for this, it is argued, lie in changing incentive structures for both litigants and national courts, which have reduced the appeal of bringing goods cases, as well as a rise in EU legislation. The consequence is a demise of negative and a turn towards positive integration.

Introduction

Few fields have had such a profound impact on European integration as the free movement of goods, and no provision within this domain has played nearly as important a role as Article 34 TFEU, which prohibits quantitative restrictions and measures having equivalent effect between Member States. How the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) interprets these notions has generated great interest among legal and political science scholars alike – so great, in fact, that it has been called a ‘fetish’ (Dougan, Citation2010, p. 165). This is anything but surprising. The case law on goods has exerted doctrinal influence across the entirety of free movement law (Enchelmaier, Citation2017) and beyond (Nicolaïdis, Citation2017); it has affected political processes at the Member State and EU level (Schmidt, Citation2018); and it has been a crucial element in the shaping of the internal market (Schütze, Citation2017) and the European economic constitution (Maduro, Citation1998).

Somewhat in contrast to this relevance, empirical work on the free movement of goods is scarce. The most prominent investigation remains Stone Sweet (Citation2004), which analysed the case law developments, the dynamics that were driving it, and its effects on internal market governance until the late-1990s. The study found a mutually reinforcing link between jurisprudence, litigation, and legislation. The CJEU’s generous interpretation of the free movement rules in a few early landmark rulings led to a sharp rise in litigation activity, as clever traders relied on Article 34 TFEU to challenge unwanted domestic regulation. This, in turn, further fuelled judicial activism and stimulated European law-making, all of which ended up triggering yet more litigation. The picture painted by Stone Sweet aligns with classical accounts of the primacy of negative integration (Scharpf, Citation1996, Citation1999) that continue to define our current understand of EU governance (Grimm, Citation2015; Davies, Citation2016; Höpner & Schmidt, Citation2020). On this view, EU governance is skewed towards judicial, not political tools (Dawson, Citation2013). Case law and litigation are the driving forces behind economic integration, with the Court of Justice acting as the lynchpin of the internal market project.

The present article sets out to challenge this vision. It draws on an original dataset containing all CJEU rulings on Article 34 TFEU from 1961 through 2020. The study offers a retrospective on the development of the free movement of goods over the past six decades. It also shows that some of the widely spread assumptions about the field have stopped being accurate. The core thesis advanced is that the free movement of goods has undergone a significant change: cases on Article 34 TFEU are vanishing, judicially-driven market integration has come to an end. Instead, the internal market in goods is increasingly determined by EU legislation, which provides a clearer and more stable alternative for all actors involved. The findings do not call into question the accuracy of the litigation and negative integration paradigm as an account of the foundational period of European market building. However, they suggest that economic integration in the EU has evolved and entered a new phase which is marked by a very different logic.

The article proceeds as follows. It will start by explaining prevalent conceptions about the role of negative integration and its connection with litigation. It will then introduce the dataset and present the main empirical findings. It will become apparent that Article 34 TFEU cases are disappearing from the Court’s docket. The following section will try to enquire into the reasons for this development, which has been gradually unfolding since the mid-1980s. It will assess to what extent Stone Sweet’s theory can help with explaining the decline and propose an alternative explanation relating to changes in the incentive structure for litigants and national courts as well as the rise of EU legislation. The final section will argue that the results indicate that the internal market has undergone a transformation, with negative integration no longer playing the central role it used to in advancing free movement, and reflect on the implications of this transformation for EU governance.

Negative integration and the logics of litigation

The internal market was designed as a two-engine project. On the one hand, national trade barriers were supposed to be removed. On the other, common European rules were meant to be created. The former process is called ‘negative’, the latter ‘positive’ integration. Drawing on previous work by Tinbergen (Citation1965), Fritz Scharpf was among the first to highlight the differences between these two modes of integration (Citation1996, Citation1999). He also posited that the European project suffers from an asymmetry: negative integration is much better developed, and more influential, than positive integration. This has, for one, to do with the activist case law of the Court of Justice, which transformed the then-Communities from a simple, if ambitious, international organisation into a constitutional legal order, often at the expense of national regulatory autonomy. For another, it is the result of the difficulties connected with reaching political agreement among the Member States, which means that progress on European legislation is difficult to achieve (Scharpf Citation1988).

The free movement of goods is widely believed to be the paradigm example of this asymmetry (Stone Sweet, Citation2004; Scharpf, Citation2010; Grimm, Citation2015). Simplifying, the classic story, which has been told many a time (Weiler, Citation1999; but see Schütze, Citation2021), goes as follows. In a series of decisions starting in the mid-1970s, the CJEU considerably broadened the scope of the EU rules on the free movement of goods. In Dassonville (Case 8/74), it went beyond traditional readings of free trade by interpreting Article 34 TFEU as including not just discriminatory laws, but any measure affecting trade, be it ‘directly or indirectly, actually or potentially’. In Cassis de Dijon (Case 120/78), it ruled that product requirements constituted restrictions on free movement, establishing what the Commission would later coin the principle of mutual recognition. Some 15 years later, the Court re-thought its position in Keck and Mithouard (C-267/91), excluding non-discriminatory ‘selling arrangements’ from judicial review, before widening the scope of Article 34 TFEU again in the late-2000s in Italian Trailers (C-110/05) by creating the new category of obstacles to ‘market access’.

Positive integration is believed to be less advanced in comparison. Famously scarce in the early days of the Communities (Armstrong & Bulmer, Citation1998, p. 147), legislative output has increased since the mid-1980s after the change to qualified majority voting in the Single European Act and the concentrated effort made as part of the 1992 programme, inspired by the Commission’s White Paper on Completing the Internal Market. This led to the adoption of EU harmonisation in a wide range of sectors as well as various flanking measures. Still, positive integration in the field of goods, as well as in other areas of free movement, is thought to lag behind negative integration. Scholars have argued that all major choices about the direction of economic integration continue to be taken by the Court (Davies, Citation2016) and that, due to the ‘over-constitutionalisation’ of the free movement rules, the case law renders legislating difficult and stifles political debate (Grimm, Citation2015; Scharpf, Citation2017; Höpner & Schmidt, Citation2020). The result is that the internal market in goods has a far stronger negative than positive dimension and is primarily judicially, not politically-led (Dawson, Citation2013; but see Dawson, Citationforthcoming). Call this the ‘negative integration bias’-thesis.

The central institution of negative integration is the CJEU, but the primary fuel it runs on – to continue the engine metaphor – is litigation (Kelemen, Citation2011). Negative integration crucially depends on legal disputes being brought, so that the Court of Justice can lay down the principles governing free movement law and subject national trade barriers to judicial review. Why and how does litigation on the free movement of goods arise? The most detailed theoretical and empirical examination of this question can be found in the scholarship of Alec Stone Sweet and his co-authors Thomas Brunell and Margaret McCown (Citation1998, Citation1998, Citation2004). As part of a broader investigation into the role of judges in European integration, Stone Sweet examined the dynamics of trade litigation and its effects on the internal market. Proposing a theoretical model based on transnational activity, governance, and law-making, he articulated and tested expectations about litigant behaviour in the EU as well as the responses it would trigger. Looking at EU law in general, Stone Sweet and Brunell found an increase in preliminary references between the 1960s and late-1990s and identified a strong positive connection with levels of trade (Citation1998). They argued that cross-border exchanges generated demand for dispute resolution as conflicts about the rights and obligations of the actors involved in these exchanges were arising.

Looking at the free movement of goods in specific, Stone Sweet found a similar upward trend. Litigants, relying on the Court of Justice’s expansive case law on Article 34 TFEU, used the provision instrumentally to remove domestic trade barriers. This created a series of feedback loops. For one, successful litigation prompted more litigation: the CJEU sent positive signals to litigants by interpreting the free movement rules broadly and striking down national laws; traders responded to these by trading and litigating more fervently; which pushed the Court to strike down even more national laws. In addition, successful litigation prompted EU legislation. The removal of national laws in legal proceedings made it costlier for Member State governments to maintain their domestic regulatory systems and put pressure on them to react, which was only possible through legislating at the European level. In the words of Stone Sweet (Citation2004, p. 129):

The Court’s case law on [Art. 34] combined with the doctrines of supremacy and direct effect to give traders rights that were enforceable in national courts. The argumentation framework produced gave very wide scope to [Art. 34], placed a heavy burden on Member State governments to justify claimed exceptions to [Art. 34], and directed national judges to enforce trader's rights where governments could neither prove reasonableness nor necessity. This structure encouraged traders to use the courts as makers of trade law. Although important, the production of favorable doctrines does not conclude the story. The more the legal system actually removes barriers to markets, the more subsequent litigation will be stimulated. That is, positive outcomes will attract more litigation, negative outcomes will deter it. Further, the more effective the legal system is at enforcing [Art. 34], the more pressure adjudication puts on the [EU's] legislative organs to harmonize market rules.

Although written in 2004, Stone Sweet’s analysis of the free movement of goods is effectively limited to the developments before mid-1998, which is when his data stop. The overall picture which emerges is that of an impressive and interconnected rise of trade, litigation, and EU legislation, which is fed by the Court of Justice’s generous interpretation of Article 34 TFEU. The Keck ruling is discussed as a factor possibly altering the status quo. Even if acknowledging the doctrinal changes brought about by the decision and the potential ramifications for the role of both the Court and the EU legislative process, Stone Sweet ultimately considers its effects to be limited. He views it as an adjustment, not ‘a doctrinal revolution’, whose ‘primary value has been to help the Court preserve the Cassis-Dassonville framework, by pruning it of its most controversial elements’ (2004, 144). All of this is in line with the ‘negative integration bias’-thesis. The Court continues to be the central actor in the economic integration process, which creates incentives for traders to litigate and, thus, contributes to a continuous deepening of the EU internal market.

The evolution of goods litigation: data and time trend

The analysis in this article builds on an original dataset of all CJEU decisions on Article 34 TFEU rendered between 1961 and 2020. For several reasons, the choice was made to create a new dataset instead of updating existing ones. Stone Sweet’s (Citation2004; together with McCown) dataset on the free movement of goods is, unlike those compiled with Brunell on preliminary references and infringement proceedings, not publicly available. Also, there are questions about the coding of some of the variables such as the case outcome, which the authors were able to identify only in half of the decisions studied.Footnote1 Kilroy (Citation1999) gathered a dataset on free movement of goods rulings rendered until 1994 but only coded a random sample of 60% of cases and, due to the focus of her enquiry, mainly focused on variables which are not relevant to this study. Egan and Guimaraes (Citation2017) focus on SOLVIT disputes and complaints submitted to the Commission, not CJEU rulings.

The present dataset consists of all decisions in which the CJEU reviewed a regulatory measure (European or national) on grounds of Article 34 TFEU (n = 509 cases). They were collected from Curia. The decisions were coded for general information about the case (type of proceedings; formation of the Court) as well as variables specifically connected with the subject area (type of regulatory measure; outcome of case; phase in doctrinal evolution). A full description of the variables is provided in the appendix. The data are presented at case level. Additional data were gathered from the IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics (on intra-EU trade), Eur-Lex (on EU legislation), and from Curia (on infringement proceedings and other free movement of goods cases). Similarly to Stone Sweet (Citation2004), the analysis here relies on descriptive statistics.

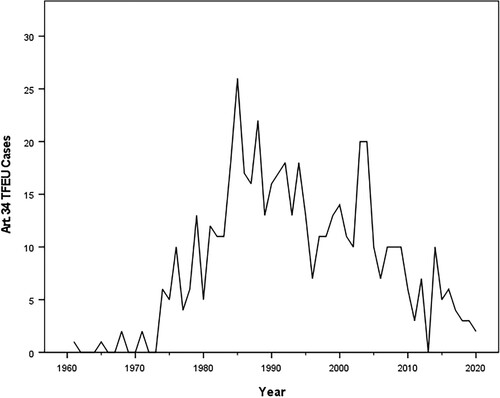

shows the evolution of litigation in the field of free movement of goods over time. We see very low annual case numbers between 1961, the year in which the first ruling on the free movement of goods was rendered, and the mid-1970s. At that point, litigation rises sharply for around a decade until 1985, where the numbers peak (26 cases). Subsequently, there is a slight and then, as of the mid-1990s, a more pronounced decline. This trend continues in the following, with cases numbers continuing to go down, except for one brief rise in the early-2000s. If we break down the data by type of proceeding (Figure 1A in appendix), we see that this temporary increase can be attributed in its entirety to the short-term spike in infringement proceedings in the years before and after the 2004 enlargement; for private litigants, case numbers have been falling since the mid-1980s. In 2013, for the first time since 1973, there was not a single case on Article 34 TFEU before the Court of Justice. The numbers since have mostly remained in the low single digits.

The data suggest that Article 34 TFEU cases are vanishing. Over the past decade, there were as many – or, rather, as few – rulings on the free movement of goods as in the early-1970s. In terms of case numbers, we have reverted back to the pre-Dassonville era. The results cast a first important doubt on the negative integration narrative, which presents the field as one marked by high litigation rates and accords the Court a correspondingly prominent role in market regulation. This is the story of the free movement of goods in the short period between the mid-1970s until the mid-1980s, perhaps even until the mid-1990s, where case numbers were still relatively high. It is much harder to reconcile with the developments that have unfolded since. There have been strikingly few goods cases and there is no indication that we are finding ourselves in an anomalous period. In fact, what we see seems to be the logical continuation of a trend which has begun over three decades ago.

Defenders of the ‘negative integration bias’-thesis might object that we are moving too fast, that sheer case numbers are not everything and that the Court’s rulings can exert an influence on the field even where there is few of them, they were rendered in the past, or they have moved to other areas of law. There is some truth in this argument, as I shall explain below. However, the conclusion that, over time, something fundamental has changed in the free movement of goods, is hard to avoid. Litigation on Article 34 TFEU, once the most important part of the Court of Justice’s docket, has faded into the background.

Why are Article 34 TFEU cases disappearing?

The developments in the case law raise the question as to what happened: why is litigation on Article 34 TFEU disappearing? Stone Sweet’s theoretical framework would suggest looking for possible reasons in the extent of transnational activity, the content of CJEU rulings, and legislative progress at the European level. It will be shown in the following that none of these factors matter, or at least not in the way in which Stone Sweet anticipated. The changes we see reflect that the incentives and needs for bringing cases on the free movement of goods before the Court of Justice have diminished, a development that started in the period between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s and deepened subsequently. This goes for all three main actors involved in the litigation process: private litigants, the Commission, and national courts.

Changing levels of trade

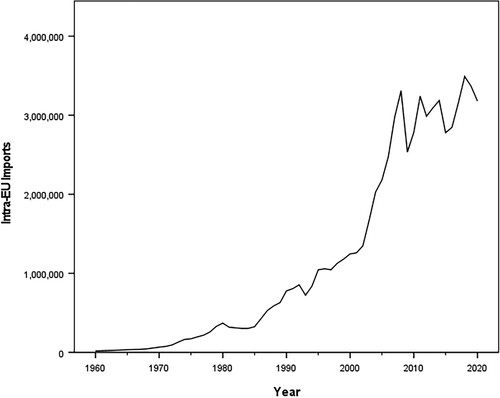

One obvious explanation for the decline in Article 34 TFEU cases could be falling levels of trade in the EU. As mentioned, Stone Sweet and Brunell (Citation1998) argued, analysing data on preliminary references until 1995, that trade in the EU had a positive causal effect on litigation before the Court of Justice. Against this backdrop, one might expect to observe the same relationship in the field of free movement of goods: the less trade between Member States, the fewer cases on Article 34 TFEU will be brought.

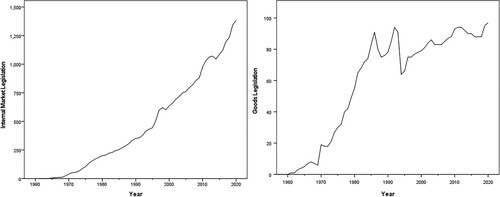

A look at the data on intra-EU imports suggests that this is implausible (). Volumes of intra-EU imports have almost steadily risen since the 1960s. There has been a small dip in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, but the numbers have recovered since. Crucially, there is no decrease after the mid-1980s. In fact, the 20 years between then and the financial crisis mark the period of the steepest growth in intra-EU trade. There is no indication that the changes in numbers of goods cases are the result of a drop in trade between Member States, confirming earlier criticisms voiced against Stone Sweet and Brunell’s findings (Alter, Citation2000, p. 500; Schmidt, Citation2018, p. 53).

Weaker incentives for litigants

A different, more plausible explanation has to do with shifts in the incentive structure for litigation. Two factors have made it less attractive for traders to bring cases based on Article 34 TFEU: doctrinal changes and better compliance at the national level.

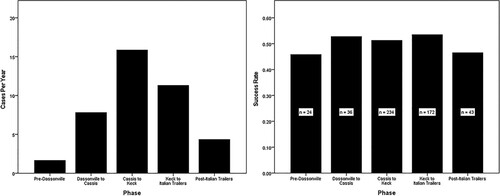

Doctrinal changes first. As explained above, the case law on Article 34 TFEU has gone through different phases. The provision was initially interpreted narrowly, its scope was then significantly broadened in Dassonville and Cassis de Dijon, limited in Keck, and, once again, broadened in Italian Trailers. The case numbers largely reflect these doctrinal turns (). If we look at litigation rates in each phase, and add a two-year period from the day of the given ruling to account for the time it takes for a new doctrine to be picked up by litigants, invoked in legal proceedings, and the possible delay connected with the processing of a preliminary reference,Footnote2 the following picture emerges: we see very few cases pre-Dassonville, a significant spike after the Dassonville and Cassis, and a decline after Keck. All this aligns with Stone Sweet’s proposition of a feedback loop between law and litigation. Expansive doctrines are received by traders as signals inviting litigation, while narrower doctrines communicate that litigation is not (as) promising and, thus, disincentivise legal challenges.

Figure 3. Annual number of Article 34 TFEU cases and success rates, broken down by phase in doctrinal development. Note: A two-year period has been added to each phase from the day of the given ruling to account for the time it takes for a new doctrine to become the basis of legal proceedings before the CJEU.

The one doctrinal turn which does not abide by this logic is the most recent Italian Trailers. We would expect the renewed widening of the scope of Article 34 TFEU to lead to a rise in litigation (Spaventa, Citation2009; Dunne, Citation2018), which it has not. Why not? Partly, this could be due to the conceptual ambiguity surrounding the ‘market access’ test that was set out in the ruling (Snell, Citation2010; Davies, Citation2010); later case law has not managed to provide clarity in this regard (Schütze, Citation2016). Consequently, it might not be apparent to litigants what exactly is gained by having this new ground for review. But it is also likely that the other, non-doctrinal developments that have taken place in the meantime – and will be discussed below – have altered the context for traders and absorbed the effects of the broadening of the scope of Article 34 TFEU. Alongside the general burden and uncertainty connected with litigation, ‘going to Luxembourg’ might no longer look like as attractive a route as it used to.

It is interesting to note in this context that the doctrinal changes have not led to significant changes in success rates of litigation. Remember that Stone Sweet theorised that litigants cared more about outcomes than abstract legal principles. If this were true, one would expect them to bring more cases in periods where the CJEU is particularly interventionist. The data do not bear this out. The likelihood of winning a case before the CJEU, i.e., the Court finding a regulatory measure to be in violation of free movement law,Footnote3 has remained fairly stable over time. Throughout all phases of litigation on the free movement of goods, and despite significant differences in the number of legal actions brought, applicants have won roughly half of their cases. There is an increase in success rates from before to after Dassonville (45.8% to 52.8%), whereas we see, surprisingly, a slight decline following Cassis (51.3%) and a further increase following Keck (53.5%). The changes do not reflect those we see in the case numbers. Litigants seem to be driven more by the abstract promise of winning, encapsulated in expansive legal doctrines, than by actual success rates.

Doctrine is the supply side of litigation, but there is also a demand side: litigants will only bring legal proceedings if there is a need for them to do so, because they have suffered (legally recognised) harm. Stone Sweet predicted that there was an inherently expansive logic in this dynamic (Citation2004, p. 132). Traders would start with challenging the ‘most obvious and direct’ obstacles to free movement, such as border inspections, licensing requirements, and other import restrictions. Spurred by the progressive case law of the Court, they would then shift their attention towards more indirect hindrances like technical standards, labelling requirements, and rules on shop opening hours. Their successes here would inspire further litigation, and so on.

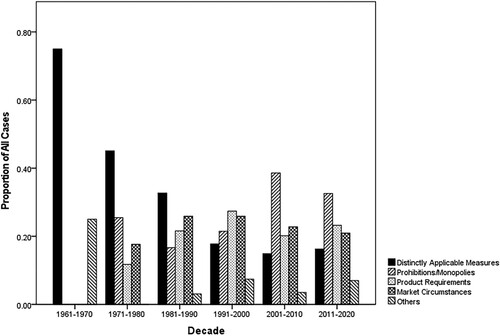

Measures challenged in goods cases can be divided into two main types: distinctly and indistinctly applicable rules. The latter can be further sub-divided into prohibitions/monopolies; rules on product requirements; market circumstances; and others. Although there is a longstanding debate about the broader objective of Article 34 TFEU – is it meant to liberalise trade or to promote economic freedom more in general (C-292/92 Hünermund, Opinion AG Tesauro)? –, it is widely accepted that distinctly applicable measures, also known as direct discrimination, constitute the ‘cardinal sin’ in free movement law. They are associated with the strongest form of protectionism and amount to Stone Sweet calls the most obvious and direct obstacles to trade. Indistinctly applicable trade restrictions can have significant economic effects too, but they are considered to be less harmful for the internal market.

The data show that there has, indeed, been a reorientation in litigant behaviour over time (). Cases directed at distinctly applicable measures were the predominant type in the first phase of goods litigation, giving rise to the majority of trade disputes between 1961 and 1990. After that, we start to see a shift. Indistinctly applicable measures become the main target for litigation, with their relative share increasing (with rules on product requirements initially taking the lead and, since 2000, prohibitions and monopolies), while disputes involving distinctly applicable measures practically disappear. However, contrary to Stone Sweet’s idea of a feedback loop, this reorientation has not led to an increase in litigation or even kept it stable. Instead, it is likely that improvements in national compliance have contributed to bringing down case numbers. Distinctly applicable measures are, on the one hand, particularly restrictive of trade as they seriously disadvantage or even exclude foreign economic operators from the domestic market. On the other, they are also particularly easy to identify for traders and hard to justify for national governments (Zglinski, Citation2020). Consequently, once distinctly applicable measures began to disappear in the Member States, litigants lost both their biggest and weakest enemy to trade. This may have lowered their appetite to bring legal challenges against national regulations.

Changing priorities of Commission

A separate note is warranted on the Commission, which is a special litigant. It has greater resources than most private litigants and has proven to be more successful in proceedings before the CJEU (Carrubba & Gabel, Citation2015). Although it is, as the guardian of the Treaties, supposed to monitor Member State compliance with EU law, it has almost unfettered discretion in how it wants to exercise this role. This, importantly, includes the power to decide whether to bring, or not to bring, infringement proceedings against Member States, a choice it makes based on its capacity and priorities.

Infringement proceedings initiated by the Commission have contributed to just under 30% of all Article 34 TFEU cases (151), which is a significant share. But the Commission’s involvement in free movement of goods litigation has varied strongly across different periods. Looking at the absolute numbers (Figure 1A), we see limited engagement throughout the 1960s and most of the 1970s, followed by a sharp increase in activity as of 1979. This phase, which lasts until 1992, has been well-documented in the literature as an attempt to push forward the internal market project in the aftermath of the Cassis ruling (Alter & Meunier-Aitsahalia, Citation1994). There is a second burst of activity around the 2004 EU enlargement. Since then, there has been a tangible decrease in goods litigation, which reflects the Commission’s general re-orientation towards informal, pre-emptive enforcement strategies (Cheruvu & Fjelstul, Citation2021; Kelemen & Pavone, Citation2022).

The more revealing figures, however, are those on the relative case numbers of goods cases among all infringement proceedings (Figure 2A). The free movement of goods was the Commission’s top priority when the internal market project was kicked off, with the vast majority of infringement proceedings throughout the 1960s and the first half of the 1970s concentrated in this area. Post Cassis, we see a renewed focus here, which peaks in 1984, when almost two-fifths of all infringement proceedings concerned goods. The share of goods cases has continuously and significantly dropped since. Over the last decade, they constituted only 1.8% of all infringement proceedings. Partly, this decrease can be attributed to the creation of procedural tools such as the prior notification mechanism (Directive 83/189, now 2015/1535), which obliges Member States to inform the Commission of new technical standards and, thus, nips potential conflicts in the bud, or the introduction of the SOLVIT mechanism, which has created an effective platform for non-judicial dispute resolution (Egan & Guimaraes, Citation2017; Kokolia, Citation2018). But partly, it also indicates that the Commission considers the free movement of goods to be sufficiently well established. The policy-driven efforts to re-launch the internal market project after the White Paper and push it forward ahead of the 2004 enlargement have contributed to the consolidation of the field. This makes it less pressing to invest precious enforcement capacities here.

Weaker incentives for national courts

It has not just become less attractive for litigants to bring goods cases, it has also become less appealing for national judges to submit preliminary references in this area. Preliminary references make up over two-thirds of the Court of Justice’s goods docket. Three reasons suggest that the willingness of domestic judges to make references for preliminary rulings on Article 34 TFEU may have decreased.

The first one was already mentioned: Keck. Stone Sweet (Citation2004, p. 140) suspected that an important factor motivating the CJEU’s decision to narrow down the scope of Article 34 TFEU in Keck was that national courts refused to apply the broad Dassonville test when reviewing domestic legislation and used a discrimination test instead. If this were true, and the CJEU only tried to accommodate what was existing practice at the national level anyway, we should not see much change in reference activity after the ruling. Given the clear downward trend in references after Keck, a different reading appears more convincing. The ruling was not just a message to overzealous litigants, but also to over-diligent national judges who were happy to abide with their requests, as perhaps most vividly illustrated by the Sunday trading saga. In fairly direct terms, the CJEU asked Member State courts to stop submitting any and every national law for review, especially not those with a tangential connection to trade only. The signal appears to have been received.

Secondly, the law on the free movement of goods has settled. Despite the doctrinal changes that were discussed, the fundamental do’s and don’ts in this area have been clarified over the years. Doctrinal problems have not ceased to arise, but they have become rarer. This is reflected in the steep drop of rulings in goods disputes – steeper than in the general case law – in which the Court sits as a Grand Chamber or equivalent, a formation which is reserved for the resolution of new and complex questions (Figure 3A).Footnote4 At the same time, domestic judges have gained a better understanding of how Article 34 TFEU works. Although this does not mean they always get it right (Jarvis, Citation1998), it does lessen the need for them to seek the CJEU’s advice.

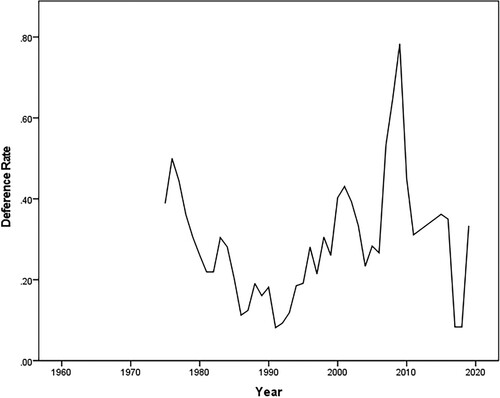

Thirdly, and partly as a result of that, the CJEU has begun to defer to national courts more frequently. When making a ruling in a preliminary reference proceeding, the Court of Justice can either decide whether a national law violates the free movement rules itself or it can delegate this assessment to the referring judge (Tridimas, Citation2011; Zglinski, Citation2020). Whereas the former option was dominating throughout the 1980s, the latter has become increasingly common between the early-1990s and late-2000s (). This notably concerns decisions on the justification and proportionality of Member State action (Zglinski, Citation2018). The rise in deference might sound good for from a perspective of domestic judicial power, since Member State judges gain decision-making autonomy, but it also makes submitting preliminary references less enticing. Qualitative studies show that national judges want to receive as detailed instructions as possible from the CJEU. In interviews, justices have articulated their discontent with being given incomplete or ambiguous answer to the questions that they posed (Krommendijk, Citation2019, p. 401; Citation2021, p. 121) and stated that their participation in the European judicial dialogue depends on whether CJEU rulings offer clear guidance on EU law (Mayoral, Citation2017, p. 562). As the Court of Justice increasingly chooses to hand decisions on various aspects of judicial review over to them, Member State courts might think: if I have to do the hard part myself afterwards, why bother submitting a reference at all?

More EU legislation

The adoption of EU legislation is the final – and perhaps most important – factor that is likely to have affected the number of Article 34 TFEU cases. As explained, Stone Sweet suggested in his work that there is a ‘virtuous cycle’ between negative and positive integration. The CJEU’s expansive interpretation of the Treaties would lead to litigation, which would inspire EU legislation, which, in turn, would lead to more litigation. If this were true, one would expect increases (or decreases) in litigation to go hand in hand with increases (or decreases) in legislation.

Looking at the data on internal market legislation in general and free movement of goods legislation in specific, we see that this relationship holds true approximately until the early-1990s (). Both legislation and litigation grow considerably during this period. After that, however, the ways of the two part. EU legislation continues its rise, in the case of goods legislation after a brief consolidation phase in the years following the White Paper on the Internal Market, whereas the number of goods cases falls. There is reason to believe that this contrapuntal movement is no coincidence. It makes doctrinal sense that more EU legislation would lead to fewer Article 34 TFEU cases. Harmonising measures remove a product or economic activity from the scope of the four freedoms (Syrpis, Citation2016; Ní Chaoimh, Citation2022). Once a domain is fully harmonised, free movement rights stop to apply and disputes in the field are resolved based on secondary law. Even where the harmonisation is only partial, the legislative measure will determine certain aspects of the legal problems at stake. In this way, parts of the Article 34 TFEU docket are ‘harmonised away’.

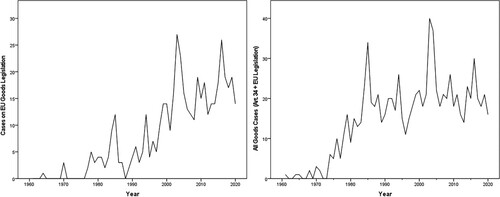

Against this backdrop, a look at disputes concerning EU goods legislation is warranted. Due to the just-described doctrinal dynamics, one might suspect that cases on the free movement of goods have simply moved from one field (primary law) to another (secondary law) and continue their rise in this new guise. The data show that there has been an uptick in proceedings on goods legislation, indeed, which starts in the mid-1980s and becomes more pronounced after the mid-1990s ().Footnote5 Yet, when we add these numbers to those on Article 34 TFEU, we see that their impact is ultimately limited. The combined number of all free movement of goods cases, i.e., disputes on both primary and secondary law, has grown until 1985 and then considerably dropped. Since the late-1980s, and with the temporary exception of the years around the 2004 enlargement, we see a plateauing of goods cases at around 20 per annum.

Figure 7. Number of cases on EU goods legislation and combined number of goods cases (Art. 34 TFEU and legislation).

The results cast doubt on both limbs of the ‘virtuous cycle’-thesis. Litigation may lead to legislation, but evidently there is also something else going on. The relative paucity and stability of goods cases over the past three decades cannot account for the dramatic expansion of EU legislation. The EU political process does not need the push from the Court of Justice to legislate; it is increasingly getting active of its own initiative. Conversely, and more significantly, legislation does not necessarily lead to more litigation. Although new European laws on goods can and do trigger some legal disputes, overall they have contributed to getting case numbers down. And this should not surprise us. One important reason for legislating is to clarify the rights and obligations of producers, traders, and states which would otherwise not be clear under Article 34 TFEU, a notoriously open-textured norm, and would require determination through the judicial process. So it is not that EU legislation only causes a ‘relocation’ of litigation from primary to secondary law, it can reduce the need for litigation in the first place by providing more precise legal guidelines about what is and what is not permitted. In other words, legislation does not just create a feedback loop that leads to more litigation, it can also break this loop.Footnote6 In hindsight, the ‘virtuous cycle’ appears not like a defining feature of the free movement of goods, but rather like a phenomenon of its early years during which the system was booting.

Governing without (European) judges: a matured internal market

The findings show that the free movement of goods has substantially evolved over the past six decades. For a short, if influential, period it constituted a prime example of the negative integration paradigm. During this period, which can be roughly dated between 1974 and 1985, it was, in line with Scharpf’s and Stone Sweet’s analyses, defined by little legislation, high litigation rates, and far-reaching judicial activity which resulted in the CJEU playing a – possibly the – central role in market integration and regulation. But the field has undergone a transformation since, which commenced in the mid-1980s and has accelerated since the mid-1990s. Case numbers started to go down, doctrinal principles were softened, and the European lawmakers spurred into action. The result is that internal market governance has come to rely less on adjudication and more on legislation. The institutional corollary to this shift is that judges preside over market regulation to a smaller extent than they used to. And where they are, we see a change from centralized to decentralized enforcement. National courts are increasingly being given discretion to settle disputes on Article 34 TFEU autonomously. As a result, the role of the CJEU has become more limited.

All of this suggests that we might be witnessing the end of negative integration in the free movement of goods. Two immediate clarifications are in order. Firstly, this is not to say that negative integration has disappeared altogether. Despite doctrinal changes like Keck which have lowered the penetrating power of Article 34 TFEU, many of the foundational principles governing the free movement of goods continue to apply. Discriminatory measures are still prima facie prohibited, as are product requirements and certain rules governing market circumstances; measures that restrict free movement must be justified; and they must comply with the principle of proportionality. This core jurisprudential acquis remains intact and relevant in areas that have not been (fully) harmonised. The enforcement of that acquis is likely to have migrated from the EU to the Member State judiciaries to some degree. Due to their growing familiarity with free movement rules and developments such as the rise of deference, national courts may apply Article 34 TFEU independently to a greater extent, i.e., without referring to the CJEU. Although there is no evidence, systematic or anecdotal, that this has led to a significant increase in domestic goods litigation or judicial activism, more research is needed to understand the application of free movement law at the national level.

Secondly, the end of the negative integration paradigm should not be conflated with a complete loss of CJEU influence over market governance. The Court is responsible for interpreting the provisions laid down in EU legislation. Even if the Court’s discretion here is more limited than in Article 34 TFEU cases, this task comes with real interpretive power that can shape important aspects of internal market regulation. Further, CJEU rulings can affect European and domestic lawmaking even from the ‘shadows’ (Schmidt, Citation2018). They have an impact on the legislative process by altering the bargaining conditions under which laws are enacted. Likewise, they can influence the substantive content of the rules that end up being adopted. EU lawmakers have been shown to codify CJEU judgments in some high-profile cases (Davies, Citation2016), although one needs to be careful to not underplay the role of the legislature and overstate that of the Court in this context (Zglinski, Citationforthcoming).

These clarifications aside, the results of this study suggest that the potential of negative integration as a route for advancing the internal market in goods may have largely been used up. Over the past three decades, case law on Article 34 TFEU has not prompted significant leaps forward. Goods cases are not only declining in quantitative terms, their qualitative relevance is declining too. Rulings on Article 34 TFEU touch on ever more detailed aspects of the free movement of goods. Even where more serious doctrinal changes are made, as in Italian Trailers, they do not leave any palpable impact on litigation or regulation. Instead, progress is increasingly made via the legislative route. Step by step, the EU has harmonised a wide range of economic sectors, covering around 80% of the market in goods (Commission, Citation2017). Although the quality of some of this legislation has been criticized (Scharpf, Citation2017), its effects on free movement are indisputable. For traders, the result is that, more and more, it is European secondary law, not case law that defines their rights and obligations.

The Cassis decision symbolises this evolution like no other. Some 10 years after the ruling, the EU adopted Regulation 1576/89 (now 110/2008) in which it harmonised standards for the definition, description, presentation, and labelling of spirit drinks in the EU, including minimum alcohol requirements. Would the facts of the dispute arise today, the case would not be resolved based on Article 34 TFEU but the Regulation. Positive integration has swallowed negative integration’s poster child. Weatherill explains that, far from being a coincidence, this illustrates the in-built weaknesses of negative integration as a tool for market governance: it is a model based on policing free movement rules ‘by ad hoc litigation’, which is ‘inapt to generate confidence in the viability of cross-border trade’ (Citation2021, p. 125).

The changes we see in the free movement of goods reflect the broader evolution of EU governance, while also challenging our understanding of it. Wallace and Reh (Citation2014) have argued that the ‘Community method’, which marked the foundational period of the European integration project, was displaced by the ‘regulatory mode’ during the 1990s as the internal market progressed (see also Majone, Citation1996). Among the hallmarks of this new form of governance are the centrality of the Commission both as the initiator of regulatory measures and their enforcer in the judicial forum; the adoption of harmonisation by the Council and Parliament as co-legislators; and the significant role played by the Court of Justice, which is supported by national courts, in interpreting and applying EU rules. The developments that have taken place in the free movement of goods provide evidence of the turn towards regulation. Since the Single European Act, but especially after the Treaty of Maastricht, there has been considerable legislative activity at the EU level, with harmonising measures covering ever more products and economic sectors. On the judicial side, the picture is more nuanced. Although the CJEU, if including cases on goods legislation, does play a meaningful role in implementing EU rules, it is certainly less significant than anticipated. This is, in parts, due to the growing disinterest of the Commission in bringing infringement proceedings in this area; in parts, due to the greater space which is given to decentralized enforcement by national courts; and, in parts, due to decreased need for litigating as a result of increased law-making. The current approach to goods governance is defined by extensive European legislation with limited European adjudication.

The foregoing suggests that the internal market in goods has entered a more mature phase of its existence. The (frantic) phase of market creation that defined the field until the mid-1980s/90s has passed and a (calmer) period of market maintenance and fine-tuning has set in (Maduro, Citation1998; Egan, Citation2001). This is not to say that the internal market has reached a stage of ‘completion’ – as, first, the Treaty of Rome and, then, the Commission’s White Paper anticipated it would by 1970 resp. 1992 – or even its final destination. There are still significant differences in trade levels between the EU and comparable federal or quasi-federal markets such as the US, even when correcting for factors like language, distance, and population (Aussilloux et al., Citation2017). It could be that attempts will be made to close this gap in the future, although it seems likelier that the EU, for political, constitutional, and socio-cultural reasons, will continue to have a comparatively more fragmented market (Snell, Citation2019). Either way, the internal market has proven to be a dynamic structure (Weatherill, Citation2017, p. 27), so changes are inevitable. But they will be a reaction to the current framework, not that from the 1970s.

Conclusion

The free movement of goods is commonly thought of as the embodiment of negative integration, with a governance structure that is defined by a strong judicial process, fuelled by – and fuelling – litigation, which eclipses the much weaker political process. This, as the article has tried to argue, is no longer true. An analysis of the CJEU’s case law on Article 34 TFEU shows that the number of goods disputes has been continuously decreasing since the mid-1980s. The drop is the result of shifting incentive structures for litigants and national courts, which have reduced the appeal of bringing goods cases, as well as a rise in EU legislation. These developments suggest that negative integration might have run its course as a tool for promoting trade and further advancing the internal market in goods.

The findings of the present study relate to goods, but it is tempting to contemplate whether the same developments could unfold in other fields of free movement and EU law more broadly. The case law on Article 34 TFEU has been a ‘pacemaker’ (Enchelmaier, Citation2017), creating path dependencies that have affected the remaining freedoms of movement and EU citizenship rules (Schmidt, Citation2012). There are some important contextual differences between the various areas of free movement: the scope of the remaining free movement rights was widened only in the 1990s and there has, so far, been no Keck moment; the level of harmonisation differs from field to field; questions concerning persons and services tend to be politically more salient than those concerning goods; the types of litigants vary. Still, it appears likely that some of the basic dynamics that can be seen in the free movement of goods will materialise elsewhere – perhaps they already are. More European legislation will be adopted, Member States will improve compliance with core EU legal principles to avoid having their laws quashed, and the doctrinal content of these principles will become clearer which, in turn, will prompt greater deference to national courts. This will diminish the appeal of litigation and, by the same token, limit the role of CJEU-driven negative integration.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (106.8 KB)Acknowledgements

I want to warmly thank Martijn van den Brink, Michal Ovádek, Urška Šadl, Susanne Schmidt, Robert Schütze, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. I have immensely profited from discussing an earlier draft of this article at the Internal Market Seminar at Católica University Porto with Hanna Eklund, Benedita Menezes Queiroz, and Miguel Poiares Maduro. The usual disclaimer applies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset for this article can be accessed via the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XJJ5N4 and the author’s institutional website at https://www.lse.ac.uk/law/people/academic-staff/jan-zglinski.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jan Zglinski

Jan Zglinski is Assistant Professor at the Law School of the London School of Economics and Visiting Research Fellow of the Oxford Institute of European and Comparative Law.

Notes

1 This could be the result of only focusing on winning and losing as possible outcomes (not deference to national courts), but it is impossible to verify this without access to the data. Further, it is unclear how the ‘type of national regulation challenged’ variable was coded.

2 Similarly, but with three-year lag, see Gabel et al., Citation2012.

3 The Court has three basic options when reviewing the compatibility of a Member State act with the four freedoms and EU law more broadly: it can rule that the act violates EU law; that the act does not violate EU law; or defer the decision to the national court (see Zglinski, Citation2020 for a more detailed explanation). Success rates have been calculated based on the first option.

4 The Grand Chamber only decides cases which are of particular ‘difficulty or importance’ (Art. 60(1) Rules of Procedure) or in which a Member State or an EU institution is party to the proceedings and requests so (Art. 16(3) Statute). Between 2016 and 2020, the percentage of Grand Chamber rulings was 10.65% overall, compared to 5.56% in goods cases.

5 The cases were gathered through Curia by searching for all CJEU decisions whose subject-matter is the ‘approximation of laws’ and which mention the words ‘goods’ and/or ‘free movement of goods’ in the text of the judgment. Cases were subsequently verified manually and rejected if they did not, in substance, concern the free movement of goods, but other areas of EU law (e.g., the free movement of services or persons).

6 I am grateful to Martijn van den Brink for helping me articulate this point.

References

- Alter, K. (2000). The European Union’s legal system and domestic policy: Spillover or backlash? International Organization, 54(3), 489–518. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081800551307

- Alter, K., & Meunier-Aitsahalia, S. (1994). Judicial politics in the European Community. Comparative Political Studies, 26(4), 535–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414094026004007

- Armstrong, K. A., & Bulmer, S. J. (1998). The governance of the single European market. Manchester University Press.

- Aussilloux, V., Benassy-Quéré, A., Fuest, C., & Wolff, G. (2017). Making the best of EU’s single market. Notes du Conseil d’analyse économique, 38(2), 1–12. doi:10.3917/ncae.038.0001

- Carrubba, C. J., & Gabel, M. J. (2015). International courts and the performance of international agreements: A general theory with evidence from the European Union. Cambridge University Press.

- Cheruvu, S., & Fjelstul, J. C. (2021). Improving the efficiency of pretrial bargaining in disputes over noncompliance with international Law: Encouraging evidence from the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(9), 1249–1267. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1945130

- Commission. (2017). Proposal for a Regulation on the Mutual Recognition on Goods Lawfully Marketed in Another Member State. SWD(2017) 475 final.

- Davies, G. (2010). Understanding market access: Exploring the economic rationality of different conceptions of free movement Law. German Law Journal, 11(7), 671–703. doi:10.1017/S2071832200018800

- Davies, G. (2016). The European Union legislature as an agent of the European Court of Justice. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(4), 846–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12353

- Dawson, M. (2013). The political face of judicial activism: Europe’s Law-politics imbalance. In M. Dawson, B. D. Witte, & E. Muir (Eds.), Judicial activism at the European court of justice. Edward Elgar.

- Dawson, M. (forthcoming). Re-visiting Europe’s ‘law-politics imbalance’. In M. Dawson, B. De Witte, & E. Muir (Eds.), Revisiting judicial politics in the EU. Edward Elgar.

- Dougan, M. (2010). Legal developments. Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(1), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02099.x

- Dunne, N. (2018). Minimum alcohol pricing: Balancing the ‘essentially incomparable’ in Scotch Whisky. The Modern Law Review, 81(5), 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12368

- Egan, M. (2001). Constructing a European market. Oxford University Press.

- Egan, M., & Guimaraes, M. (2017). The single market: Trade barriers and trade remedies. Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(2), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12461

- Enchelmaier, S. (2017). Restrictions on the use of goods and services. In M. Andenas, T. Bekkedal, & L. Pantaleo (Eds.), The reach of free movement. Springer.

- Gabel, M. J., Carrubba, C. J., Ainsley, C., & Beaudette, D. M. (2012). Of courts and commerce. The Journal of Politics, 74(4), 1125–1137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000679

- Grimm, D. (2015). The democratic costs of constitutionalisation: The European case. European Law Journal, 21(4), 460–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12139

- Höpner, M., & Schmidt, S. K. (2020). Can we make the European fundamental freedoms less constraining? A literature review. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 22, 182–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/cel.2020.11

- Jarvis, M. (1998). The application of EC law by national courts: The free movement of goods. Oxford University Press.

- Kelemen, R. D. (2011). Eurolegalism. Harvard University Press.

- Kelemen, R. D., & Pavone, T. (2022). Where have the guardians gone? Law enforcement and the politics of supranational forbearance in the European Union.

- Kilroy, B. (1999). Integration through law: ECJ and governments in the EU. PhD dissertation. Proquest.

- Kokolia, S. (2018). Strengthening the single market through informal dispute-resolution mechanisms in the EU: The case of SOLVIT. Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 25(1), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X18768680

- Krommendijk, J. (2019). The highest Dutch courts and the preliminary ruling procedure: Critically obedient interlocutors of the Court of Justice. European Law Journal, 25(4), 394–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12322

- Krommendijk, J. (2021). National courts and preliminary references to the Court of Justice. Edward Elgar.

- Maduro, M. P. (1998). We the Court: The European Court of Justice and the European economic constitution. Hart.

- Majone, G. (1996). Regulating Europe. Routledge.

- Mayoral, J. A. (2017). In the CJEU judges trust: A New approach in the judicial construction of Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(3), 551–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12488

- Ní Chaoimh, E. (2022). The legislative priority rule and the EU internal market for goods. Oxford University Press.

- Nicolaïdis, K. (2017). The Cassis legacy: Kir, banks, plumbers, drugs, criminals and refugees. In B. Davies, & F. G. Nicola (Eds.), European Law stories: Critical and contextual histories of European jurisprudence. Cambridge University Press.

- Scharpf, F. W. (1988). The joint decision trap: Lessons from German federalism and European integration. Socio-Economic Review, 66(3), 239–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1988.tb00694.x

- Scharpf, F. W. (1996). Negative and positive integration in the political economy of European welfare states. In G. Marks, F. W. Scharpf, P. C. Schmitter, & W. Streeck (Eds.), Governance in the European Union. SAGE.

- Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and democratic? Oxford University Press.

- Scharpf, F. W. (2010). The asymmetry of European integration, or why the EU cannot be a 'social market economy'. Socio-Economic Review, 8(2), 211–250. doi:10.1093/ser/mwp031

- Scharpf, F. W. (2017). De-constitutionalisation of European Law: The Re-empowerment of democratic political choice. In S. Garben, & I. Govaere (Eds.), The division of competences between the EU and the Member States: Reflections on the past, the present and the future. Hart Publishing.

- Schmidt, S. K. (2012). Who cares about nationality? The path-dependent case law of the ECJ from goods to citizens. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.632122

- Schmidt, S. K. (2018). The European Court of Justice and the policy process: The shadow of case law. Oxford University Press.

- Schütze, R. (2016). Of types and tests: Towards a unitary doctrinal framework for article 34 TFEU? European Law Review, 41(6), 826–842.

- Schütze, R. (2017). From international to federal market: The changing structure of European law. Oxford University Press.

- Schütze, R. (2021). ‘Re-constituting’ the internal market: Towards a common law of international trade?. Yearbook of European Law, 39, 250–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/yel/yeaa005

- Snell, J. (2010). The notion of market access: A concept or a slogan? Common Market Law Review, 47(2), 437–472. doi:10.54648/COLA2010020

- Snell, J. (2019). Cassis at 40. European Law Review, 44(4), 445–446.

- Spaventa, E. (2009). Leaving Keck behind? The free movement of goods after the rulings in Commission v Italy and Mickelsson and Roos. European Law Review, 35(6), 914–932.

- Stone Sweet, A. (2004). The judicial construction of Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Stone Sweet, A., & Brunell, T. L. (1998). The European Court and the national courts: A statistical analysis of preliminary references, 1961–95. Journal of European Public Policy, 5(1), 66–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501768880000041

- Sweet, A. S., & Brunell, T. L. (1998). Constructing a supranational constitution: Dispute resolution and governance in the European Community. American Political Science Review, 92(1), 63–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585929

- Syrpis, P. (2016). EU secondary legislation and its impact on derogations from free movement. In P. Koutrakos, N. Nic Shuibhne, & P. Syrpis (Eds.), Exceptions from EU Free Movement Law: Derogation, Justification and Proportionality. Hart.

- Tinbergen, J. (1965). International economic integration. 2nd ed. Elsevier.

- Tridimas, T. (2011). Constitutional review of Member State action: The virtues and vices of an incomplete jurisdiction. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 9(3-4), 737–756. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mor052

- Wallace, H., & Reh, C. (2014). An institutional anatomy and five policy modes. In H. Wallace, M. A. Pollack, & A. R. Young (Eds.), Policy-Making in the European union (7th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Weatherill, S. (2017). Internal market as a legal concept. Oxford University Press.

- Weatherill, S. (2021). Did Cassis de Dijon make a difference? In A. Albors-Llorens, C. Barnard, & B. Leucht (Eds.), Cassis de Dijon: 40 Years On. Hart Publishing.

- Weiler, J. H. H. (1999). The constitution of the common market place: Text and context in the evolution of the free movement of goods. In P. Craig, & G. De Búrca (Eds.), The evolution of EU law (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Zglinski, J. (2018). The rise of deference: The margin of appreciation and decentralized judicial review in EU free movement law. Common Market Law Review, 55(5), 1341–1385. https://doi.org/10.54648/COLA2018116

- Zglinski, J. (2020). Europe’s passive virtues: Deference to national authorities in EU free movement law. Oxford University Press.

- Zglinski, J. (forthcoming). The internal market: From judicial politics to ordinary politics. In M. Dawson, B. De Witte, & E. Muir (Eds.), Revisiting judicial politics in the EU. Edward Elgar.