ABSTRACT

This paper studies the determinants of support for future generations, using novel survey data for the case of Germany. I find significant, but not overwhelming support for prioritizing the needs of future generations vs. the acute needs of present-day citizens. Moreover, individual-level and contextual factors matter too. High-income and highly educated citizens are on average more supportive of the needs of future generations, the elderly and women less so. Left-wing supporters are equally more supportive of future generations, especially supporters of the Greens and those subscribing to ‘green-alternative-liberal’ values. Supporters of the right-wing populist AfD are most strongly opposed. General political trust boosts support for future generations, and economically thriving local economies are associated with higher levels of support for future generations as well.

Introduction

Addressing a long neglected issue in comparative public policy research, a recent body of scholarship has started to explore the temporal dimension of (re-)distributive policies, i.e., issues such as individual-level preferences regarding long-term investment policies and policy-makers’ actions in dealing with inter-temporal distributional conflicts (Armingeon & Bürgisser, Citation2021; Christensen & Rapeli, Citation2021; Jacobs, Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2016; Jacobs & Matthews, Citation2012, Citation2017; Jacques, Citation2021; Kraft, Citation2018). At the root of many discussions in these literatures is the question of whether the supposed short-termism of policy-making is a consequence of individual ‘presentism’, i.e., a ‘natural human tendency’ to care more about the present than about the future (Thompson, Citation2010, p. 17) or whether instead political institutions and perhaps the nature of democracy itself is to blame (Jacobs, Citation2016; MacKenzie, Citation2016). The first part of this question is at the focus of this paper.

Using novel survey evidence for the case of Germany, I explore public attitudes towards long-term oriented policies, which could – if sufficiently salient – overcome the inherent short-termism of democratic policy-making. At least, some studies have found that preferences for long-term policies have been found to have a meaningful impact on policy-making (see e.g., Schaffer et al. (Citation2022) for the case of climate change policy and Busemeyer et al. (Citation2020) for education policy). To preview my findings: A first descriptive finding is that the notion of ‘presentism’ (Thompson, Citation2010) cannot be dismissed entirely as the majority of citizens indeed expresses support for policies that are more focused on the needs of present-day rather than future generations. However, I find significant support for future-oriented policies as well as a notable degree of variation across individuals and local contexts: More specifically, support for future generations is higher among individuals who are well-endowed with various resources, i.e., those with higher incomes and more education, whereas the elderly and women are more in favor of present-day oriented policies. A strong local economy is also associated with higher levels of support for future-oriented policies. Furthermore, partisan ideology matters as well with left-leaning individuals being more supportive of future-oriented policies, particularly supporters of the Greens as well as the Left Party. My analysis also confirms a positive association between political trust and support for future generations.

Literature review

Broadly speaking, most research on distribution and redistribution within the welfare state focuses on present-day struggles about ‘Who wants what?’ (Rueda & Stegmueller, Citation2019, see also the recent review of the expanding literature on public attitudes towards the welfare state by Kumlin et al. (Citation2022)). As argued by Jacobs (Citation2016, p. 434): ‘Students of the politics of policy making have principally examined policy choice as a distributive decision about who gets what, rather than an intertemporal decision about when they get it’. In line with Jacobs (Citation2011, Citation2016) and others (Armingeon & Bürgisser, Citation2021; Christensen & Rapeli, Citation2021; Jacobs & Matthews, Citation2012, Citation2017; Jacques, Citation2021; Kraft, Citation2018), this paper addresses the question of public support for intertemporal (re-)distribution between current-day and future generations head-on. While noting the recent upsurge in studies on the politics of the long-term on the part of political elites (Cronert & Nyman, Citation2022; Sheffer et al., Citation2018), the focus of this paper is rather on the micro level of attitudes and preferences of individuals. Even though there is relatively little research on this particular issue as such, I can draw on a number of insights from related literatures that help to derive plausible theoretical expectations.

To start, the paper builds on a growing literature in welfare state research that has studied public attitudes towards social policies that are more oriented towards the future, thereby addressing the issue of long-term investment policies in an indirect manner. This is, for instance, research on public attitudes on education policy (Busemeyer, Citation2012; Busemeyer et al., Citation2020; Lergetporer et al., Citation2018) or social investment policies more broadly conceived (Bremer & Bürgisser, Citation2022; Busemeyer et al., Citation2022; Ferrera, Citation2017; Garritzmann et al., Citation2018; Kurer & Häusermann, Citation2022). One important finding in this literature is that support for future-oriented policies such as social investment is generally high, but particularly vulnerable to fiscal trade-offs: When faced with a choice between prioritizing social policies with a stronger focus towards present-day needs such as pensions or when confronted with the need to cut back other parts of the welfare state in exchange for increasing social investment, support for the latter drops significantly (Bremer & Bürgisser, Citation2022; Häusermann et al., Citation2019; Neimanns et al., Citation2018). Hence, as the majority of benefits resulting from social investment policies materialize in the long term, they are particularly vulnerable to intertemporal trade-offs (Ferrera, Citation2017). Another important finding is that supporting coalitions for social investment oriented policies are primarily to be found among highly-educated, left-leaning and younger individuals (Garritzmann et al., Citation2018; Häusermann et al., Citation2015) as well as those individuals that express high levels of political trust (Busemeyer & Lober, Citation2020; Garritzmann et al., Citation2023).

Relatedly, the influential work of Jacobs and Matthews (Citation2012, Citation2017; Jacobs, Citation2011) adopts a broader perspective on long-term social investment policies which they define as ‘policies that extract resources from a wide swath of the population in exchange for a promise to use those resources to deliver a broadly valued social benefit’ (Jacobs & Matthews, Citation2017, p. 195). In their earlier empirical analysis (Jacobs & Matthews, Citation2012), the focus is on pensions (which is commonly not regarded as ‘social investment’, but consumptive spending in the literature cited above). In the latter study (Jacobs & Matthews, Citation2017), they analyze an issue in public investment (investing in road infrastructure) rather than social policy. Nevertheless, in both studies, the findings are quite similar in the sense that political trust is identified as a crucial variable that matters for support for long-term oriented policies.

A second distinct strand of literature that remains so far disconnected from the previously mentioned work is scholarship on attitudes towards climate change policies and, in particular, the relationship between social policy and ecological attitudes. Regarding attitudes towards climate change and the environment, recent research shows that attitudes are not only determined by socio-economic factors such as education or income, but also by psychological dispositions towards the needs of future generations (Beiser-McGrath & Huber, Citation2018). Interestingly and in parallel to the research on social investment cited above, there is also evidence that general political trust is positively related to support for climate change policies (Kulin & Johannson Sevä, Citation2021), suggesting the existence of an underlying dimension of support for future-oriented policies.

More mixed evidence is found for the relationship between social policy and ecological attitudes. On the one hand, there is considerable evidence that the supporting coalitions for progressive social policy and ambitious climate change policies overlap, in particular in the Nordic countries (Fritz & Koch, Citation2019; Jakobsson et al., Citation2018; Otto & Gugushvili, Citation2020; Spies-Butcher & Stebbing, Citation2016). And again, political trust and ideology seem to matter the most in shaping attitudes on these issues (Otto & Gugushvili, Citation2020, p. 13). On the other hand, however, other studies have found the relationship between support for progressive social policy and ecological transformation to be more complex and less clear-cut (Fritz et al., Citation2021; Koch & Fritz, Citation2014). Jakobsson et al. (Citation2018), for instance, find varying degrees of complementarity between social policy and environmental attitudes across welfare state regimes and some evidence for small-scale crowding out effects in the sense that potential trade-offs between the two might exist after all. Employing a more rigorous experimental research design in the case of Switzerland, Armingeon and Bürgisser (Citation2021) find strong evidence for a hard trade-off between redistribution and environmental protection and expect it to become even ‘more salient and politicized in the future’ (Armingeon & Bürgisser, Citation2021, p. 490). They find attitudes to be driven largely by ideology and ‘myopic self-interest’ (Armingeon & Bürgisser, Citation2021, p. 491).

Lastly, the paper may connect indirectly to a third strand of literature in economics on time discount preferences (Harrison et al., Citation2002; Lawrance, Citation1991; Read & Read, Citation2004; Wang et al., Citation2016). This literature focuses on individual time discount rates, i.e., how strongly individuals discount future pay-offs (to themselves). Scholarship on time discount rates has found a significant degree of variation of discount rates at the individual level with higher levels of income and education being associated with a stronger long-term orientation (Harrison et al., Citation2002; Lawrance, Citation1991). The effect of age, in turn, could be non-linear with younger and older individuals being less future-oriented compared to the middle-aged (Read & Read, Citation2004). Furthermore, there is evidence that time horizons also vary systematically at the country level, indicating that the ‘[p]erception of time is a part of culture’ (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 116). In a more recent contribution to the study of economic voting, Wang (Citation2017) finds that individual ‘patience’ is related to individuals paying more attention to the state of the national economy rather than their own personal economic situation when making voting decisions (see also Wang (Citation2018) for an application of this argument to the case of redistribution).

Even though research on individual time horizons is certainly of relevance for this paper, its contribution is rather indirect as I am concerned with preferences about policies (not individuals’ decision-making rationales) and their pay-offs to future generations, i.e., going beyond the individual time horizons that are typically tested in the above mentioned literature. Nevertheless, it can be plausibly argued that there should be some association between individual discount rates and support for future-oriented policies (see e.g., Beiser-McGrath & Huber, Citation2018 for the case of climate change attitudes), even though this is a matter for empirical investigation. The recent contribution of Christensen and Rapeli (Citation2021) is a nice example of how the two can be connected. They analyze in a conjoint experiment to what extent the manipulation of the timing of the pay-offs from different policies matters for their support (similar to Jacobs and Matthews (Citation2012)). They find that individuals are indeed willing to accept pay-offs that go beyond the immediate short term, but support drops significantly once the time horizon turns towards the long term (20-30 years). In my analysis below, the focus on ‘future generations’ goes even beyond that in terms of the time horizon and the implicit fact that pay-offs would not accrue to themselves, but different (future) generations. Interestingly, though, Christensen and Rapeli (Citation2021) also find evidence that education levels and political trust tend to increase support for more long-term oriented policies.

Theoretical expectations

In the following, I will develop a number of theoretical expectations about the determinants of individual-level support for the needs of future generations broadly defined, building on the insights from the above mentioned literatures. As mentioned briefly in the introduction, the ultimate motivation for this research question is to better understand the political dynamic of long-term investment policies seen from the perspective of public opinion, i.e., individual level-attitudes and preferences. Furthermore, the focus is on preferences for policies that benefit future generations broadly conceived and not individual time discount rates or time horizons related to different intertemporal pay-offs for policies. The latter issues have been more at the center of existing scholarship, which is why I focus on the former.

Why is this focus relevant and interesting? A common element between the above mentioned approaches to measuring support for long-term investment policies is that they ultimately explain support for long-term investment policies with some form of enlightened material self-interest, i.e., to what extent does the individual herself benefit from particular policies. This support can be influenced by the intertemporal distribution of pay-offs or the nature of the policy itself (social policy, infrastructure investment, environmental policy etc.). In this paper, in contrast, the focus is on genuine preferences for intergenerational redistribution, i.e., the (re-)distribution of policy benefits between different generations, thereby excluding (or at least downplaying) the possibility that the individual herself will directly benefit. Furthermore, I deliberately abstract from particular policies in order to avoid potential feedback effects from the particular policy characteristics in order to derive a measure for genuine, albeit somewhat generalized and vague, support for policy investments that primarily benefit future generations.

Expectations regarding the degree of short-termism in the population

Many scholars have pointed out a significant degree of short-termism democratic policy-making (Jacobs, Citation2016), i.e., a tendency among policy-makers to pay more attention to the needs of present-day citizens rather than future generations, believed to be caused and reinforced by the timing of the election cycle (Sheffer et al., Citation2018; but see Cronert & Nyman, Citation2022 for a different view). In the case of climate change, for instance, research has pointed to the influential role of powerful interest groups representing the fossil fuel industry, but also to politicians concerned about short-term electoral losses related to the unpopularity of climate mitigation policies, in particular if the latter lead to higher energy costs, as explanations for a lack of commitment (Finnegan, Citation2020, Citation2022; Geels, Citation2014; Meckling & Nahm, Citation2022). In the case of education policy, scholars have pointed to the significant gap between strong public support for further investments in education on the one hand and a continued lack of actual spending increases on the other, noting that the role of public opinion in driving education policy is contingent on party politics and interest groups as well as the salience of particular issues in education reform (Busemeyer et al., Citation2020).

The latter example, however, also hints at a potentially positive role of public opinion in driving support for long-term investment policies. Or put differently, the crucial question that is at least partly addressed in this paper is whether the supposed and observed short-termism of democratic policy-making is primarily due to inherent characteristics of citizens or whether it is in fact due to political institutions (Jacobs, Citation2016), personal characteristics of political elites (Sheffer et al., Citation2018), state capacity (Meckling & Nahm, Citation2022), powerful interest groups (Finnegan, Citation2022) or a combination of these. One position in this debate is represented by Thompson (Citation2010), who argues that:

Most citizens tend to discount the future, and to the extent that the democratic process responds to their demands, the laws it produces tend to neglect future generations. The democratic process itself amplifies this natural human tendency. These characteristics of democracy lead to what I call its presentism – a bias in the laws in favor of present over future generations. (Thompson, Citation2010, p. 17)

The contrasting case is made by MacKenzie (Citation2016), among others. He argues that the concern of individuals for the future is rather malleable than fixed, or in his words: ‘moderate but adjustable’ (MacKenzie, Citation2016, p. 27). In line with this idea, the economics literature on time horizons mentioned above has found early on that time preferences are not constant across individuals, but vary in line with socio-demographic characteristics. But where could support for future generations come from – against all odds? One argument is influenced by Wang’s (Citation2017) study of patience and its link to socio-tropic voting. In his reading, ‘patient’ individuals realize the long-term benefits of particular policies for the economy as a whole and adjust their voting choices accordingly. Put more broadly, it could be argued that some individuals pay more attention to the long-term effects of present policy choices on the society as a whole, independent of policy effects on their own personal situation.

Taken together, this two sides of the argument about presentism suggests that even though short-termism is widely distributed in the population, it should not be the only game in town, i.e., I expect to find a significant minority of the population that is willing to privilege the interests of future generations in policy-making (Hypothesis 1).

Individual socio-economic determinants of support for future generations

Regarding potential individual-level determinants of support for future generations, I start with socio-economic and demographic variables. The literature discussed above commonly finds a positive association between income and educational background on the one hand and support for social investment and climate change policies on the other, although the underlying theoretical mechanism remains somewhat unclear. Equally, I expect both income and educational background to be positively associated with support for future generations (Hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2). The reasoning behind this argument is that for one, high-income citizens are less likely to be distracted by immediate short-term needs as they enjoy a secure economic position. In line with Inglehart’s (Citation1977) theory of post-materialism, individuals with a rich endowment of material resources can better afford to pay attention to issues (and policies) from which they derive no immediate material rewards. A similar logic applies to highly educated citizens, although in this case one might add the particular role of education in sensitizing citizens to the potentially harmful consequences of present-day short-termism and the long-term benefits of policies that also benefit future generations.

Regarding age, the initial theoretical expectations are ambivalent. On the hand, elderly individuals might be more concerned with the needs of future generations as they are closer to bequeathing their individual and ‘societal’ wealth to their children (and hence might think of their children when thinking about future generations). On the other hand, the young might associate the needs of ‘future generations’ with their own future needs as they themselves might still be affected by the actions of present-day governments. Given the strong role of self-interest as a determinant of welfare state attitudes and preferences, I rather expect the latter effect to dominate and hence hypothesize a negative association between age and support for future generations (Hypothesis 2.3).

With regard to gender, research on social policy attitudes has shown that women tend to be more supportive of expansive compensatory social policies than men, even prioritizing social insurance over social investment policies (Garritzmann & Schwander, Citation2021; Häusermann et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, given that women still shoulder more care duties than men, they are also likely to demand further support from the welfare state in this respect, and thereby less likely to support redistribution towards future generations. Women also are, on average, in structurally weaker labor market positions; hence they should be more supportive of short-term policies addressing present-day concerns. Some of the gender effect is likely controlled away by income and education (which are correlated with labor market success), but I expect an additional effect of gender above and beyond these controls due to socialization effects of women into these positions and particular roles in society more broadly. In short, I hypothesize that women are less supportive of the needs of future generations (Hypothesis 2.4).

Ideology, norms and support for future generations

Next, I discuss the role of ideology and related attitudinal variables. Here, it is important to emphasize that due to the cross-sectional and observational nature of the data, I can merely show correlations rather than causality. Nevertheless, it is plausible to assume that deeper lying ideological predispositions as typically captured by indicators of partisan ideology are more likely to shape attitudes towards future generations rather than the other way around. In a first step, I consider general left-right ideology. Again inspired by the above mentioned literature, the theoretical expectation is that left-leaning individuals are more likely to support future generations (Hypothesis 3.1) as green and other left parties are typically also found to promote social investment and ecological policies (Röth & Schwander, Citation2021).

However, when digging deeper, the association between ideology and support for future generations is actually more complex than it looks at first sight. In welfare state and party politics research, it is by now increasingly recognized that the party political space is defined by (at least) two dimensions rather than merely one. The first of these dimensions refers to the traditional class cleavage centered on issues of material distribution and redistribution with one pole of this dimension being defined as support for market-based policy approaches and the other by support for statism (economic left-right dimension). In contrast, the second dimension centers on social values related to issues such as globalization, liberalism, multiculturalism and environmentalism. Different conceptions of the second dimension can be found in the literature, but I largely follow Hooghe et al. (Citation2002) here in defining one pole of the social values dimension as support for ‘green-alternative-liberal’ (GAL) values vs. ‘traditional-authoritarian-nationalist’ (TAN) values on the opposing pole.

In line with work on the ideological determinants of support for social investment policies (Garritzmann et al., Citation2018), I hypothesize that the second dimension is a more important determinant of support for future generations than the first. The first dimension of economic redistribution focuses on present-day distributive conflicts between rich and poor and should therefore be less relevant for considerations of intertemporal trade-offs. The second dimension in contrast pits supporters of values such as environmentalism and globalism against supporters of nationalism and authoritarian values. The support for ‘green’ values in particular is clearly associated with support for policies that benefit future generations as present-day actions are (currently) likely to threaten the environment for future generations. In contrast, sympathizers for nationalism and authoritarian values are likely to be more focused on pay-offs in the immediate future as Busemeyer et al. (Citation2021) have shown with regard to the social policy preferences of right-wing populist voters.

Hence, I posit that GAL values should be positively associated with support for future generations, whereas TAN values are associated with the opposite (Hypothesis 3.2). Relatedly, I expect that support for future generations is likely to vary across different partisan constituencies, depending on where exactly the respective party is located in the two-dimensional space of party competition.

Furthermore, I hypothesize that general political trust should be positively associated with support for future generations (Hypothesis 3.3). This is because high-trusting individuals are more likely to accept short-term costs (i.e., paying less attention to the acute needs of present-day generations) in favor of pursuing long-term investment policies that benefit future generations (Gabriel & Trüdinger, Citation2011; Garritzmann et al., Citation2023). They are also more likely to accept the uncertainty that comes along with the long-term benefits of investment policies (Jacobs & Matthews, Citation2012, Citation2017).

Local economic context

Lastly, I also consider the potential influence of the local economic context. Recent work in comparative political economy (Iversen & Soskice, Citation2019) has revitalized research on the role of local knowledge economies in shaping individual perceptions of upward social mobility and related political outcomes. In line with this idea, I hypothesize that strong local economies should be associated with more support for the needs of future generations (Hypothesis 4), because these thriving economies provide sufficient resources in order to be able to invest in the long term. Again, some of these effects should be captured by the individual-level variables, in particular income and education, but there are likely to be contextual spillover effects as well. This is because thriving local knowledge economies also generate resources that allow policy-makers to finance local public goods such as high-quality social services and infrastructure. Furthermore, economic problems that might draw attention (and resources) to present-day needs such as high levels of unemployment or poverty are less severe in thriving local economies. These better overall resource endowments should also increase support for future generations among those who lack individual resources, resulting in a positive association between the strength of local knowledge economies and support for future generations. Potentially, this positive association could set in motion self-reinforcing feedback cycles, where prospering regions are associated with more support for long-term investment policies, which in turn help these regions to grow further in the future at the cost of growing disparities between thriving and declining localities.

Empirical analysis

Data and methods

The empirical analysis focuses on the case of Germany, using novel survey data that was collected as part of the ‘Inequality Barometer’, a survey of the German resident population on perceptions of inequality, social mobility and related policy preferences, financed with support from the Cluster of Excellence ‘The Politics of Inequality’ at the University of Konstanz. The case of Germany is selected largely for pragmatic reasons due to the availability of suitable survey data, but several arguments can be made for why the findings might be generalizable to other countries as well. For one, Germany is the largest economy on the European continent, which makes it a relevant case to study to begin with. Due to its federalist nature, Germany displays a high degree of cultural, political, economic and social variation across its different regions. The high number of observations of the survey data (see below) allows to make use of this variation, both on the individual as well as on the contextual level.

To come back to the specifics of the survey, the total number of observations is 6147. However, the question that serves as dependent variable for this analysis (see below) was only given to half of the sample, resulting in a maximum number of 3173 observations for the regression models, which is reduced to about 2300 observations for most models due to missing values.

The dependent variable in my analysis is the following question:

The government sometimes has to weigh the needs of future generations against the acute present-day concerns and needs of people. In your opinion, how should these different needs be balanced out? Please think about the time after the current Corona pandemic.

The wording of this question is deliberately vague on what exactly constitutes the ‘needs of future generations’, hence different individuals might and are in fact likely to associate different things with this question. As discussed above, the underlying reasoning behind this question wording is to provide a measure of genuine support for policies benefiting future generations independent of particular policy characteristics and independent of whether the individual herself believes to benefit directly from the policy, even if only in the long term.

Regarding socio-economic variables, income is measured in deciles of monthly household net income, based on the distribution of incomes in Germany. Education is measured as highest educational degree obtained, distinguishing between those with a higher education (university) degree (1), which is about a third of the sample, and those without such a degree (0).Footnote1 Age and gender (female = 1) are defined in a straightforward manner.

Ideological and attitudinal variables are operationalized as follows: The measure of general left-right ideology is based on this question: ‘In politics, people sometimes talk of ‘left’ and ‘right’. Where would you place yourself on this scale, if 0 stands for left and 10 for right?’ Besides general left-right ideology, I use a two-dimensional measure of partisan ideology that distinguished between positions on the economic left-right scale and positions on a second dimension based on social values – from green-alternative-liberal (GAL) to traditional-authoritarian-nationalist (TAN) values (Hooghe et al., Citation2002).Footnote2 The scales are adjusted so that higher values indicate more right-leaning/conservative positions on both scales. The models below also include measure of Party ID, where respondent are asked for which party they would vote if a federal election were to take place the following Sunday. The measure of general political trust uses responses to this question: ‘How much trust do you have in the political institutions in Germany?’, recoded into a dummy variable to ease interpretation.

Finally, the analysis includes a measure of the strength of local economies.Footnote3 This measure is based on a factor analysis of range of economic background factors measured at the local level of Kreise, i.e., local administrative units of which there are 400 in Germany. More specifically, the measures used are the net balance of educational and job migrants into a particular locality, employment shares in the construction, creative, knowledge-intense and crafts sector, employee shares with vocational and academic degrees, local unemployment rate and the average local household income. All of these variable strongly load on one underlying factor, which is used to measure the strength of the local economy.

As the dependent variable is measured on an 11-point scale, the analysis employs OLS estimation. Individuals are modeled to be nested in districts (Kreise), applying multi-level random effects estimation. I also include state (Länder) fixed effects in all models and regularly use robust standard errors. In all models, variables are standardized (except for the dummy variables) in order to calculate standardized coefficients to facilitate the comparison of estimated effects.

Results

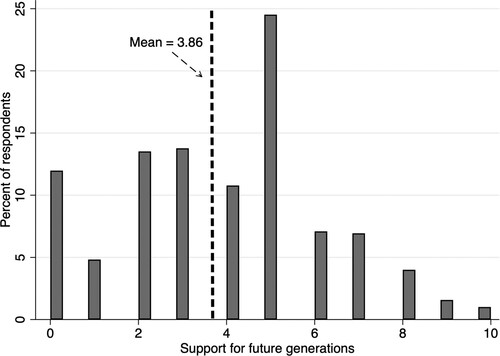

shows the distribution of responses across the 11-point response scale of the dependent variable. As a reminder, higher values indicate a stronger willingness to give more weight to the needs of future generations in governmental policy-making. Not unexpectedly, the value 5 is the modal response covering almost 25 percent of respondents. This could be partly a statistical artefact, but it could also indicate meaningful preferences of individuals to equally weigh the needs of present-day and future generations. Nevertheless, the average value on this scale across all respondents is 3.86 (SD = 2.36), indicating a certain degree of ‘presentism’ in that most citizens would rather weigh the needs of present-day generations higher than the needs of future generations. Ultimately, it is a matter of individual interpretation whether one regards this finding as the glass being half full or half empty, i.e., whether this is the dominance of ‘presentism’ in line with Thompson (Citation2010) or rather a moderate degree of support for the needs of future generations (MacKenzie, Citation2016). In any case, shows that there is a sizable minority of respondents who are willing to prioritize future generations, confirming Hypothesis 1.

displays the results of multi-level OLS regression analyses of support for future generations. A first significant finding is that socio-economic background significantly shapes attitudes towards future generations. More specifically, individuals with higher incomes and better education are more likely to take the needs of future generations into account (in line with Hypothesis 2.1 and 2.2). Using the standardized coefficient estimates of model 1 in , an increase in income of one standard deviation is associated with an increase of 0.10 points on the response scale (i.e., about a tenth of a standard deviation om the dependent variable).Footnote4 In contrast, having a university degree is associated with an increase of about 0.27 point on the response scale, i.e., almost a third of a standard deviation. As expected in Hypothesis 2.3, age is negatively associated with support for future generations: a standard deviation increase in age is predicted to be associated with a reduction in support of about −0.09 standard deviations on the response scale. This confirms the expectation that the young are more likely to prioritize future generations, potentially due to enlightened self-interest. Being female is associated with a drop in support for future generations by about −0.2 SDs (confirming Hypothesis 2.4). As mentioned above, the negative gender effect could be explained by women’s stronger demand for (social) policy support in the present-day.

Table 1. Individual-level determinants of support for future generations.

Second, also includes some attitudinal and ideological variables. The latter will be explored further below, but already reveals a clear and highly significant association between general left-right ideology and support for future generations with individuals self-identifying with the political right being more oriented towards the acute needs for present-day generations (in line with Hypothesis 3.1). Again, this is partly surprising since one could assume that left-wing party supporters could be more concerned with the immediate and present-day needs of poorer citizens – and less with the needs of future generations. The more detailed analysis below will partly explain this puzzling finding. For now, suffice it to say that the simulated effect size of left-right ideology is on the same scale as those of the socio-economic indicators discussed above (about 10 percent of a SD on the response scale).

In line with existing research (Garritzmann et al., Citation2023), confirms a positive association between general political trust and support for future generations (Hypothesis 3.3). The effect size is similar compared to the above discussed variables (0.15, based on model 2 in ).

Finally, the analysis also reveals a statistically significant association between local economic contexts and support for future generations (confirming Hypothesis 4). Interestingly, citizens in more prosperous local economies are also more likely to support the needs of future generations, but the magnitude of the effect is rather small, likely also because of the inclusion of state fixed effects (effect size of 0.05, implying that a one SD increase in the strength of local economies is associated with a change of about 5 percent of a SD on the dependent variable). Thriving local economics could increase individuals’ willingness to support long-term investment policies such as research and development, education and environmental policies, which would – in a positively self-reinforcing feedback loop – further boost the economic prospects of thriving localities. Vice versa, citizens in less prosperous areas tend to prioritize present-day needs and – as a corollary – social consumption rather than investment policies, circumscribing the long-term prospects of these regions.

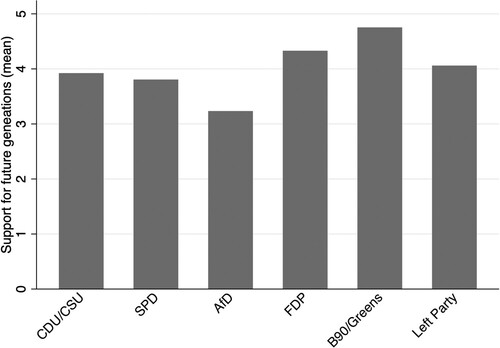

In the next step, I present a more detailed analysis of the associations between partisan ideology and support for future generations. To start, shows the variation in support for future generations across different groups of partisan supporters (excluding those that do not strongly self-identify with a particular party and those that do not vote). As could be expected given their ideology, support for future generations is highest among supporters of the Green party. Vice versa, support for the needs of present-day generations is lowest among supporters of the right-wing populist AfD (Alternative für Deutschland). This mirrors previous findings in the literature on the strong negative association between support for right-wing populist parties and social investment policies (Busemeyer et al., Citation2021). The centrist main-stream parties (the Christian democratic CDU/CSU and the social democrats (SPD)) are in between these extremes, whereas supporters of the liberal FDP and the left-wing Left Party are on average more supportive of future generations, which again is in line with previous research by Kraft (Citation2018) on the link between centrist parties and public investment policies.

The regression analysis in presents more detailed findings. Model 1 is basically a replication of Model 1 in , but adds dummies for responses to the question of who respondents would vote for if an election was happening on the following weekend (i.e., a measure of partisan identification (party ID)). Model 1 only includes the Party ID dummies as measures of ideology, confirming the significantly above average support for future generations among Green and Left Party supporters and the significantly lower support among AfD supporters. Model 2 adds general left-right ideology. Compared to , the negative effect of general left-right ideology weakens in terms of effect size as could be expected, but it remains statistically significant.

Table 2. Support for future generations and partisan ideology – more detailed results.

Models 3 and 4 split the one-dimensional general left-right ideology variable into two separate dimension as is now common in party politics and welfare state research (Häusermann & Kriesi, Citation2015): As discussed above, the first dimension captures positions on the economic left-right, whereas the second one refers to social values (green-alternative-liberal (GAL) vs. traditional-authoritarian-nationalist (TAN), cf. Hooghe et al., Citation2002). The analysis clearly shows that it is the second dimensions that matters more with regard to support for future generations compared to the first one (Hypothesis 3.2). The difference between models 3 and 4 is simply whether to additionally include party ID dummies (model 3) or not (model 4). In both cases, the social values indicator remains statistically significant even though the effect size increases when party dummies are dropped, as could be expected. The findings confirm a strong positive and significant association between TAN values and lower support for future generations, or put differently: social liberals are more supportive of future generations, whereas traditional conservatives tend to prioritize the needs of present day generations. The effect sizes (calculated as above) are −0.15 (Model 3) and −0.18 (Model 4), i.e., somewhat larger than the effect sizes associated with socio-economic variables. Compared to the social values dimension, the effect sizes associated with the economic left-right dimension are smaller (about half), even though the coefficient estimate remains statistically significant. This indicates, somewhat against expectations, that present-day conflicts about redistribution do spill over to some extent into the realm of intertemporal redistribution. Again, it is economic left-wing individuals who are more supportive of supporting future generations.

The fact the association between left-right ideology and support for future generations seems to be driven by the social values dimension rather than the economic left-right dimension can at least partly explain the above potentially puzzling observation that left-wing supporters are more supportive of future generations. Supporters of traditional mainstream left parties (in particular the SPD) as well as the more radical Left Party (as evidenced by the less significant and smaller effects in Models 2 and 3 in ) are in fact less keen on supporting future generations compared to supporters of the new left, i.e., the Greens whose positioning is determined by values rather than economic self-interest. This could indicate different responses to the latent trade-off between ecological and social policy concerns as hinted at by Jakobsson et al. (Citation2018) as well as Armingeon and Bürgisser (Citation2021), but further research is needed here.

Robustness

In the following section, I report the results of a range of robustness tests (see ). First, I include a measure of parental background in the models in order to test whether individuals who grew up in an academic household might be more inclined to support politics that benefit future generations due to their privileged upbringing. The survey only provides a rough measure of parental background, namely an indicator whether the respondent’s father or mother has a university degree. As could be expected, I find a positive association with support for future generations, but the statistical significance of the coefficient estimate is less strong compared to the other indicators of socio-economic status. The latter also remain robust to the inclusion of the parental background variable.

Table 3. Robustness tests and further analyses.

Further, I include a measure of individual time preferences in the models (starting with model 2 in ). This variable captures responses to the question ‘To what extent would you be willing to relinquish something of value today in order to reap additional profits in the future?’. Above, I speculated that individual time preferences (which are at the focus of the economics literature referred to above) might still be related to my measure of support for future generations. The results in confirm a positive association between the two, but the estimate fails to reach statistical significance. This finding confirms my above stated hunch that individual time preferences are inherently different from support for policies benefiting future generations.

In model 4 of , I add a categorical measure of employment status. Ideally, it would be possible to test for the influence of occupations on support for future generations. However, partly missing information in the survey prevents me from implementing the widely known class scheme by Oesch (Citation2013). Hence, I employ the indicator of labor market status as proxy. It turns out that labor market status has little to no effect on support for future generations above and beyond the effects of other socio-economic indicators, the only exception being long-term sick or disabled individuals who are likely to prioritize present-day needs over the future.

Model 5 in replaces the factorial indicator of the strength of the local knowledge economy with a categorical variable. As a consequence, the level-2 unit for the multi-level model is no longer defined as the district, but rather the state (Bundesland). This is done as there might be concerns that there might not be sufficient level-1 units (respondents) in each of the level-2 units (districts) due to the relatively high number of districts (almost 400). Broadly speaking, multi-level models are well suited to this kind of data structure as the model borrows statistical strength from neighboring level-2 units of analysis or the general pool of observations in case of low numbers of cases within the level-2 units. Still, there might be concerns that the number of observations per level-2 unit are systematically related to variation in the variable as rural districts might also have weaker economies. In order to deal with this concern, I construct a categorical variable of the strength of the local knowledge economy (low, medium, high), based on the distribution of cases along this scale. Model 5 shows that these categorical indicators remain positively and significantly associated with support for future generations, confirming the findings from above.

Finally, it is plausible to think about potential interaction effects between the ideological variables on the one hand and socio-economic and demographic indicators on the other. For instance, it might be the case that young individuals subscribing to left values might be even more likely to support future generations compared to older left-wing individuals. Several potential interaction effects of this kind were tested; presents a short summary of the main results (the models also include the further control variables from above). No statistically significant interaction effects can be observed, suggesting that the influence of socio-economic and ideological variables are largely independent of each other.

Table 4. Interaction effects.

Conclusions

This paper has studied the determinants of support for policies benefiting future generations, using novel survey data for the case of Germany. A first important finding is that if not the majority, it is at least a significant minority of individuals that supports policies for future generations. Secondly, the analysis revealed a significant degree of variation across individuals as well as local contexts in support for future generations, and this variation can be partly explained by the individuals’ resource endowments: High-income and highly educated citizens are on average more supportive of the needs of future generations, the elderly and women less so. Hence, reminiscent of post-materialist theory (Inglehart, Citation1977), individuals well-endowed with resources can better ‘afford’ to prioritize the needs of future generations compared to individuals who lack these resources in the present day. A third important finding, however, is that ideology matters as well. Left-wing supporters are more supportive of future generations, especially supporters of the Greens and those subscribing to ‘green-alternative-liberal’ values. Supports of the right-wing populist AfD are most strongly opposed. General political trust boosts support for future generations, and economically thriving local economies are associated with higher levels of support for future generations as well.

What are the broader implications of these findings? First of all, the paper confirms Jacobs’ (Citation2016) thesis that political struggles about the intertemporal distribution of costs and benefits are distinctly different from conflicts about (re-)distribution in the present day. At least this is suggested by the fact that attitudes towards future generations are less determined by economic left-right ideology, but rather by social value orientations on the GAL-TAN dimension. This confirms similar findings in the literature on education and social investment policies. Furthermore, while it is a common finding in the welfare state attitudes literature that high-income and highly educated individuals are less likely to support redistribution from rich to poor in the present day, they are more supportive of redistribution from present-day generations to future generations – again highlighting different political dynamics.

Taken together these findings have implications for the role of economic self-interest vis-à-vis value orientations in shaping attitudes towards intertemporal policies. It seems that economic self-interest narrowly defined may rather be a determinant of redistributive preferences in the present day, but hold less explanatory power when it comes to the question of how policy payoffs are distributive along the temporal scale. In the latter case, general ideological predispositions, but also general political trust as well as more specific attitudes (in this case: concerns about inequality), seem to have a stronger bearing on individual views.

Second, the analysis also shows that individual time preferences are distinctly different from generic support for policies benefiting future generations. Since the former are at the focus of most of the existing scholarship on intertemporal trade-offs in economics and political science, this paper adds a novel perspective to the debate by focusing on the latter. Thus, it is not necessarily the individual ‘patience’ (Wang, Citation2017, Citation2018) that determines the individuals’ willingness to privilege future generations, but rather her ideological predispositions and her socio-economic resource endowment. Further research is clearly needed on how this finding might change in hard trade-off scenarios as in Armingeon and Bürgisser (Citation2021) or Christensen and Rapeli (Citation2021). Still, the analysis provides food for thought.

A third important implication is the finding of a self-reinforcing positive feedback loop between prospering local economies and support for future generations. Again, my analysis could not establish a clear direction of causality here (which is likely to run in both directions anyway), but this feedback loop could explain growing regional disparities between thriving and declining regions. As shown by Bremer et al. (Citation2022), political factors matter in determining the level of local public investment in Germany. Hence, higher levels of local public investment could be partly driven by general popular support for the prioritization of the needs of future generations, even though this could entail short-term costs in the form of higher taxes for investment. In the long term, the positive impact of investment on economic growth is likely to reinforce these preferences and attitudes. Even though more detailed research is clearly needed here, my analysis provides at least some indication as to the plausibility of this feedback loop.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This measure also counts respondents with an advanced vocational degree on the tertiary education level as 1. This is a peculiarity of the German education system with its strong focus on vocational education. Quantitatively, this is relatively small group, so the majority of respondents coded as 1 are likely to have a university degree (the data does not allow to provide exact numbers here).

2 The six items used to construct this measure are: 1. ‘Public service enterprises and important industrial companies should be owned by the state’. 2. ‘Rank differences [in income] between people are acceptable because they essentially indicate what one has achieved given the chances one has’. 3. ‘Income differences in our society are too large’. 4. ‘People breaking the law should be punished much harder than they are today’. 5. ‘Cultural life in Germany is generally enriched by people coming here from other countries’. 6. ‘Women should be willing to reduce employment to support their family’. The first three items related to the economic left-right dimension, whereas the second three items refer to social values. This grouping of items is confirmed by a factor analysis. Predicted factor loadings are used as measures.

3 I thank Kattalina Berriochoa for matching the survey data with administrative data from the INKAR dataset.

4 When calculating effect sizes in the following, I use a similar approach, i.e., estimated the predicted change in the dependent variable associated with an increase of one standard deviation in the respective independent variable. In the case of dummy variable, I report the predicted change associated with a move from 0 to 1 in the independent variable.

References

- Armingeon, K., & Bürgisser, R. (2021). Trade-offs between redistribution and environmental protection: the role of information, ideology, and self-interest. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(4), 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1749715

- Beiser-McGrath, L., & Huber, R. A. (2018). Assessing the relative importance of psychological and demographic factors for predicting climate and environmental attitudes. Climatic Change, 149(3–4), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2260-9

- Bremer, B., & Bürgisser, R. (2022). Public opinion on welfare state recalibration in times of austerity: evidence from survey experiments. Political Science Research and Methods, FirstView. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.78.

- Bremer, B., Di Carlo, D., & Wansleben, L. (2022). The constrained politics of local public investment under cooperative federalism. Socio-Economic Review, FirstView. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwac026.

- Busemeyer, M. R. (2012). Inequality and the political economy of education: An analysis of individual preferences in OECD countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928712440200

- Busemeyer, M. R., Gandenberger, M., Knotz, C., & Tober, T. (2022). Preferred policy responses to technological change: Survey evidence from OECD Countries. Socio-Economic Review, FirstView Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwac015.

- Busemeyer, M. R., Garritzmann, J. L., & Neimanns, E. (2020). A loud, but noisy signal? Public opinion and the politics of education reform in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Busemeyer, M. R., & Lober, D. (2020). Between solidarity and self-interest: The elderly and support for public education revisited. Journal of Social Policy, 49(2), 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279419000382

- Busemeyer, M. R., Rathgeb, P., & Sahm, A. H. J. (2021). Authoritarian values and the welfare state: the social policy preferences of radical right voters. West European Politics, 45(1), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1886497

- Christensen, H. S., & Rapeli, L. (2021). Immediate rewards or delayed gratificfation? A conjoint survey experiment of the public’s policy preferences. Policy Sciences, 54, 63–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09408-w

- Cronert, A., & Nyman, P. (2022). Electoral opportunism: Disentangling myopia and moderation. APSA Preprints. https://doi.org/10.33774/apsa-2021-s7h95-v2.

- Ferrera, M. (2017). Impatient politics and social investment: the EU as ‘policy facilitator’. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(8), 1233–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1189451

- Finnegan, J. J. (2020). Varieties of de-carbonization? Comparative political economy and climate change. Socio-Economic Review, 18(1), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwz026

- Finnegan, J. J. (2022). Institutions, climate change, and the foundations of long-term policymaking. Comparative Political Studies, https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211047416

- Fritz, M., & Koch, M. (2019). Public support for sustainable welfare compared: Links between attitudes towards climate and welfare policies. Sustainability, 11(4146), 4146–4115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154146

- Fritz, M., Koch, M., Johansson, H., Emilsson, K., Hildingsson, R., & Khan, J. (2021). Habitus and climate change: Exploring support and resistance to sustainable welfare and social-ecological transformations in Sweden. The British Journal of Sociology, 72(4), 874–890. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12887

- Gabriel, O. W., & Trüdinger, E.-M. (2011). Embellishing welfare state reforms? Political trust and the support for welfare state reforms in Germany. German Politics, 20(2), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2011.582098

- Garritzmann, J., Busemeyer, M. R., & Neimanns, E. (2018). Public demand for social investment: New supporting coalitions for welfare state reform in Western Europe? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(6), 844–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1401107

- Garritzmann, J. L., & Schwander, H. (2021). Gender and attitudes toward welfare state reform: Are women really social investment promoters? Journal of European Social Policy, 31(3), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928720978012

- Garritzmann, J., Neimanns, E., & Busemeyer, M. R. (2023). Public opinion towards welfare state reform: The role of political trust and government satisfaction. European Journal of Political Research, 62(3), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12501

- Geels, F. W. (2014). Regime resistance against Low-carbon transitions: Introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(5), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414531627

- Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Williams, M. B. (2002). Estimating individual discount rates in Denmark: A field Experiment. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1606–1617. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802762024674

- Häusermann, S., & Kriesi, H. (2015). What do voters want? Dimensions and configurations in individual-level preferences and party Choice. In P. Beramendi, S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt, & H. Kriesi (Eds.), The politics of advanced capitalism (pp. 202–230). Cambridge University Press.

- Häusermann, S., Kurer, T., & Schwander, H. (2015). High-skilled outsiders? Labor market vulnerability, education and welfare state preferences. Socio-Economic Review, 13(2), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwu026

- Häusermann, S., Kurer, T., & Traber, D. (2019). The politics of trade-offs: Studying the dynamics of welfare state reform With conjoint experiments. Comparative Political Studies, 52(7), 1059–1095. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018797943

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. J. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310

- Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution. Princeton University Press.

- Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2019). Democracy and prosperity: Reinventing capitalism through a turbulent century. Princeton University Press.

- Jacobs, A. M. (2008). The politics of when: Redistribution, investment and policy making for the long term. British Journal of Political Science, 38(2), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000112

- Jacobs, A. M. (2011). Governing for the long term: Democracy and the politics of investment. Cambridge University Press.

- Jacobs, A. M. (2016). Policy making for the long term in advanced democracies. Annual Review of Political Science, 19(1), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-110813-034103

- Jacobs, A. M., & Matthews, J. S. (2012). Why do citizens discount the future? Public opinion and the timing of policy consequences. British Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 903–935. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000117

- Jacobs, A. M., & Matthews, J. S. (2017). Policy attitudes in institutional context: Rules, uncertainty, and the mass politics of public investment. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12209

- Jacques, O. (2021). Austerity and the path of least resistance: How fiscal consolidations crowd Out long-term investments. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(4), 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1737957

- Jakobsson, N., Muttarak, R., & Schoyen, M. A. (2018). Dividing the pie in the eco-social state: Exploring the relationship between public support for environmental and welfare policies. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(2), 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654417711448

- Koch, H. K., & Fritz, M. (2014). Building the Eco-social state: Do welfare regimes matter? Journal of Social Policy, 43(3), 679–703. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727941400035X

- Kraft, J. (2018). Political parties and public investments: a comparative analysis of 22 Western democracies. West European Politics, 41(1), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1344012

- Kulin, J., & Johannson Sevä, I. (2021). Who do you trust? How trust in partial and impartial government institutions influences climate policy attitudes. Climate Policy, 21(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1792822

- Kumlin, S., Goerres, A., & Spies, D. C. (2022). Public Attitudes. In D. Béland, K. J. Morgan, H. Obinger, & C. Pierson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the welfare state (2nd ed., pp. 329–345). Oxford University Press.

- Kurer, T., & Häusermann, S. (2022). Automation risk, social policy preferences, and political Participation. In M. R. Busemeyer, A. Kemmerling, P. Marx, & K. Van Kersbergen (Eds.), Digitalization and the welfare state (pp. 139–156). Oxford University Press.

- Lawrance, E. C. (1991). Poverty and the rate of time preference: Evidence from panel data. Journal of Political Economy, 99(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1086/261740

- Lergetporer, P., Schwerdt, G., Werner, K., West, M. R., & Woessmann, L. (2018). How information affects support for education spending: Evidence from survey experiments in Germany and the United States. Journal of Public Economics, 167(November), 138–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.09.011

- MacKenzie, M. K. (2016). Institutional design and sources of short-Termism. In I. González-Ricoy & A. Gosseries (Eds.), Institutions For future generations (pp. 24–46). Oxford University Press.

- Meckling, J., & Nahm, J. (2022). Strategic state capacity: How states counter opposition to climate policy. Comparative Political Studies, 55(3), 493–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211024308

- Neimanns, E., Busemeyer, M. R., & Garritzmann, J. (2018). How popular are social investment policies really? Evidence from a survey experiment in eight Western European countries. European Sociological Review, 34(3), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy008

- Oesch, D. (2013). Occupational change in Europe: How technology and education transform the Job structure. Oxford University Press.

- Otto, A., & Gugushvili, D. (2020). Eco-Social divides in Europe: Public attitudes towards welfare and climate change policies. Sustainability, 12(404), 1–18.

- Read, D., & Read, N. L. (2004). Time discounting over the lifespan. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2004(94), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.01.002

- Röth, L., & Schwander, H. (2021). Greens in government: the distributive policies of a culturally progressive force. West European Politics, 44(3), 661–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1702792

- Rueda, D., & Stegmueller, D. (2019). Who wants what? Redistribution preferences in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Schaffer, L. M., Oehl, B., & Bernauer, T. (2022). Are policy-makers responsive to public demand in climate politics? Journal of Public Policy, 42(1), 136–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X21000088

- Sheffer, L., Loewen, P. J., Soroka, S., Walgrave, S., & Sheafer, T. (2018). Nonrepresentative representatives: An experimental study of the decision making of elected politicians. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000569

- Spies-Butcher, B., & Stebbing, A. (2016). Climate change and the welfare state? Exploring Australian attitudes to climate and social policy. Journal of Sociology, 52(4), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783315584209

- Thompson, D. F. (2010). Representing future generations: political presentism and democratic trusteeship. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 13(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230903326232

- Wang, A. H.-E. (2017). Patience as the rational foundation of sociotropic voting. Electoral Studies, 50(December 2017), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2017.08.004

- Wang, A. H.-E. (2018). Patience moderates the class cleavage in demand for redistribution. Social Science Research, 70(February), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.10.005

- Wang, M., Rieger, M. O., & Hens, T. (2016). How time preferences differ: Evidence from 53 countries. Journal of Economic Psychology, 52(February 2016), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2015.12.001