ABSTRACT

The EU is still fragile after its long decade of crises since 2008, and its durability remains an open question. New capacities were created during this time. But it is not clear how robust they are and whether developing them further will encounter insurmountable obstacles, including resentment by citizens. Over time, tensions and disagreements unleashed three foundational conflicts: conflicts over sovereignty (who decides), solidarity (who gets what when and why) and identity (who we are). The crisis politics that was deployed to deal with such tensions has often constrained policy responses in scope and effectiveness. Against the odds, however, the destructive spiral stopped short of driving the Union into self-destruction: a circumstance that calls for an explanation. We summarize empirical research that shows three ways in which this unexpected resilience can be explained: public rhetorical action, externalization strategies, and the paradoxical strengths of a weak centre in achieving polity maintenance.

Introduction: the need for a new research programme

The European Union (EU) went through a long decade of crises that tested its political cohesion and economic viability to the limit. The Union survived these crises, even though some remain latent (refugee/asylum), while others are gaining momentum (cost-of-living and climate change). We know the fragility of political communities from early nation state-building, in which military conflict and economic shock could forge or destroy nations. In the tradition of Charles Tilly (Citation1975, Citation1990), Kelemen and McNamara (Citation2021) considered the pandemic as the equivalent of an external security threat for which the nascent EU polity prepares and, if it survives, consolidates as a result. Following Mancur Olson (Citation1982), one could see these crises more generally as symptoms of the EU’s economic demise, equivalent to the rise and decline of nations in the wake of institutional sclerosis (Majone, Citation2016). We choose a third option of formulating a theory in the historical-institutionalist tradition that tries to explain why the EU polity is so prone to severe crisis but also how its resilience is actively ensured.

We study the EU as a compound polity of nation-states that is historically novel (Bartolini, Citation2005; Fabbrini, Citation2007; Hix, Citation2007). Like every polity, it has boundaries that define it against the outside, authority that binds its constituent parts, and bonds that create loyalty, based on a thin, but consequential layer of transnational rights and the social acquis. Bounding, binding and bonding make it recognizable as a distinctive community in addition to those of its member states. The polity is compound, since it is a decentralized, often fragmented political system, resting on two sources of sovereignty, the member states and their citizens. In contrast to other compound polities such as federal states, these sources are quite uneven in their capacity to shape collective decisions: citizens have much less voice. Finally, the EU is a compound of robust and cohesive political entities, which resulted from the long-term process of nation-state building. Integration started in fact as the European rescue of the nation-state (Milward, Citation2000).Footnote1 The consolidation of the EU gradually became a source of de-stabilization for national state-structures, giving rise to increasing institutional and political tensions (Scharpf, Citation1999).

This compound polity has developed properties, which are historically new. They make it crisis-prone and require a constant effort at (re-)stabilization. Yet, even existential crises have not brought down the edifice. Our research approach analyses the properties that make for counter-intuitive strengths and vulnerabilities. For instance, what may look like a weakness of dispersed authority can be a source of strength in severe crises, since it incentivizes member states to uphold the centre’s monitoring capacity rather than to act as a political rival. But also, what may look like an impressive pooling of core state powers – a common currency issued by one central bank – can contribute to a systemic financial crisis for which backstops had to be improvised. We draw on the theory of Stein Rokkan et al. (Citation1999) and Albert O. Hirschman (Citation1970), as Bartolini (Citation2005) and Ferrera (Citation2005) have done before. But rather than looking for historical precedents and their long-term evolution, we re-elaborate their basic concepts and propositions to capture the specifics of compound polities.

We then take these generalizable features to characterize the EU as a political system that evolves through crises. That so much of European integration is crisis-induced, we take largely as a curse, not as a blessing in disguise. Crisis brings out power asymmetries that are normally suppressed and/or favours the exploitation of some members’ strategic advantages. Under pressure, member state representatives anticipate domestic political constraints rather than deliberate them, stressing the national advantage over the collective gains of any decisions taken. The compromises, struck as a matter of urgency, are often ‘creative’, i.e., untested, and need laborious re-engineering afterwards. In some cases, experimental solutions, based on functional assumptions, fail to deliver the expected results in diverse contexts and incite deep political divisions instead. Hence, community-building tends to proceed by stealth or through symbolic gestures which tend to remain programmatically ineffective. We see crises as a threat to sustainable EU polity-formation. However, survival and even resilience of this crisis-prone polity invite us to study the institutional resources and incentives which sustain its maintenance against the odds.

The article is organized as follows. In the next section, we revisit the tenets of the Rokkanian tradition, which we use for identifying the roots of EU fragility and for orienting our search for possible institutional and political counterpoises during crises. In section 3, we outline a theory of the EU as a distinctive form of a compound polity, a union of established national democracies. The theory provides consistent explanations for resilience as a polity despite recurrent policy crises and adds insights to other attempts at interpreting the EU through the lenses of state-building theories (Genschel, Citation2022; Kelemen & McNamara, Citation2021). The fourth section discusses a number of ways in which the EU polity was maintained when the conflict over policies escalated into a fundamental contestation of European integration. We conclude with some reflections on the advantages and pitfalls of our crisis lens.

The polity perspective: generalizing Rokkanian theory

The central proposition of the Rokkan-Hirschman model of state-building is that external closure of a polity, i.e., drawing a boundary that controls exit and entry to the political territory, triggers a process of internal political structuring. This means establishing binding authority (structures for the making of collective decisions) and developing systemic bonds of loyalty (the opening of voice channels in return for accepting authority; Ferrera, Citation2005, p. 7). Historically, the fusion between territorial control, cultural identity, democracy and social solidarity produced a virtually unique and robust political formation, the nation-state.

Bartolini (Citation2005) showed that the original Rokkan framework can also function in reverse. European integration saw a new attempt at forming a supranational authoritative centre. This reversal proceeded by opening boundaries between member states, replacing them by collectively managed functional domains and an (embryonic) outer border. This process has, however, created a master tension between opening national boundaries through supranational regulatory authority, on the one hand, and the foundations of national political structures, on the other. This tension has disrupted domestic institutional orders, often intentionally by ‘structural reformers’, but also challenged democratic representation and existing welfare state arrangements, without introducing much compensation at the supranational level (Bartolini, Citation2005, pp. 380–390; Mair, Citation2009; Scharpf, Citation2009). The gap between this national destructuring – which under the pressure of international trade and investment may have happened anyhow – and disappointed hopes for supranational restructuring is a key factor underlying the fragility of the EU polity.

The Rokkanian approach has a wider scope than the ‘bellicist’ tradition of state-building by Charles Tilly (Abramson, Citation2017). For Tilly (Citation1975), the overarching mechanism of state formation is war making: external security threats lead to the introduction of national taxation which later becomes a tax-transfer state to partly substitute, partly complement democratization. While acknowledging the role played by external threats, Rokkan’s theory shifts the attention to an endogenous logic of state development. Boundary building discourages exit by promising protection but also encourages a demand for the institutional articulation of voice and policy responses on the side of the territorial government. The fulfilment of these demands generates system loyalty, the evolution of identities and the readiness to endorse institutions of social sharing (Rokkan et al., Citation1999). But this is not an automatism and many nation-states have not succeeded. Underlying all stress tests for the EU polity is thus its capacity to replicate this logic by other means.

The application of state-building theories to EU polity-formation has led to quite pessimistic prognoses. Bellicist theories argue that in robust polities authority over the coercive apparatus must be centralized. It is thus unclear whether the EU can remain sustainable without a more complete set of state powers that goes beyond promoting markets and includes defending territorial borders (Kelemen & McNamara, Citation2021, pp. 7–8). Rokkan also considered the nation-state to be the natural endpoint of Europe’s political development: any transfer of authority to supranational institutions would encounter virtually unsurmountable obstacles. In this vein, Bartolini (Citation2005, p. 375) argued that by pursuing ‘stateless market building’, the EU had become the source of an ‘explosive mixture of problems’.

By contrast, we take seriously that the Union has survived existential crises in the long decade since 2008 and managed to build institutions that make the political-economic system more robust: a banking union and fiscal capacities to support member states when they are hit by disaster and when they recover from it.Footnote2 The EU’s demise has been over-explained while relatively little systematic research effort is spent on the resources and instruments for containing disruptive conflicts in the wake of a series of crises.Footnote3 To explain resilience, we must identify the countervailing forces to adverse dynamics that the EU is prone to. We argue that these countervailing forces must be sought in latent institutional potential and in political incentives inherent in what are sources of fragility from a Hirschman-Rokkanian perspective: porous boundaries, dispersed authority, and second-order loyalty.

The EU’s reconfiguration of bounding, binding and bonding

A polity can be a nation-state but also a composite of nation-states, i.e., a (con-)federation or association like the EU. Polities can be distinguished by different configurations of, first, boundaries that define exit and entry; second, binding authority for which voice must be granted in return; and, third, bonds of loyalty that constitute a political community among strangers. shows how the EU combines these ‘three Bs’ in a way that is unlike other historically known polities.

Table 1. Configurations of defining polity features.

The EU’s compound polity shares some features with a confederation (O’Leary, Citation2020, pp. 31–33). Its territorial borders are second order to those of the nation-states. The authority of the EU is selective, high in the domain of market integration, weak in social policy domains; and member states can opt out of the polity at their own discretion (Article 50 TFEU). But, first of all, the multi-level, formally institutionalized structure of authoritative decision-making includes two chambers of legislation, the supranational European Parliament and the intergovernmental Council, which does set it apart from confederations as relatively loose associations of states. In addition, unlike any confederation, the EU legal order has precedence over national law and has direct effect. Finally, the existence of transnational rights in case of cross-border movement, as well as some guarantees of political participation in supranational policy makingFootnote4 helps forming a European identity – at least in the sense of a status identity.

This hybrid institutional complex sustains a historically unprecedented system of sovereignty sharing. The centre takes authoritative decisions which can bind ‘all the way down’, i.e., by reaching the level of ordinary citizens or businesses. Yet the peculiar configuration of its three defining features make the EU polity susceptible to fragility and vulnerability to crises, requiring a constant effort of (re)stabilization and maintenance.

Porous boundaries

The Union’s territory is co-extensive with previously existing national territories. The EU’s borders are very different from those of its constituent member states. Ideas of homogeneous bundles of territoriality, consolidated statehood and Westphalian sovereignty marked differences from other types of polity, notably empires. The notion of national territorial sovereignty was largely a myth, which prevailed in Europe during the long nineteenth century (Ansell & Palma, Citation2004; Krasner, Citation1999; Risse, Citation2015). Like all myths, territorial sovereignty over borders had practical consequences though, most notable in the guise of bloody wars to extend or defend national borders.

The EU took off as a historically unprecedented experiment at building a polity for pacifying the relationships among its constituent units and underpinning their economic prosperity. European integration was guided by the project of market integration as the lever for peaceful political integration, providing a level playing field and realizing economies of scale. In this, the EU resembles the nation-building of small city states (Abramson, Citation2017, pp. 98–99).

This challenges the idea that resource mobilization and loyalty building can only – or even mainly – follow from the external security logic (Kelemen & McNamara, Citation2021). And even if all modern state-building provided and codified political participation and social sharing rights in order to mobilize soldiers and taxes for warfare, the post-war era turned this motivation around. NATO was another compound solution, a confederation for military defence of national democracy and welfare. The main sponsor, the United States, stationed troops on other soils, helping members to deter invasion. This was to bolster identification with ‘the West’ rather than the nation-state. The response to the invasion of Ukraine fits exactly this logic: Sweden and Finland applied for NATO membership based on the insight that they could not withstand a Russian aggressor on their own.

The EU experiment programmatically neutralizes the necessity of hard external borders and more generally of external security threats as triggers for resource mobilization. An alternative, prosperity-cum-social security logic co-evolved with national welfare states: market integration promises to produce more income and jobs but also fiscal dividends for national redistributive programmes. Once institutionalized, market integration fuels high expectations of social safety among citizens (Ferrera, Citation2020). These expectations are not necessarily fulfilled, but the prosperity-cum-social security promise is the political foundation of loyalty, tax compliance and civic responsibility. The EU’s long decade of crises has made this promise even more salient, since practically every crisis morphs into a latent or acute social crisis. The creation of a huge recovery fund by the EU in 2020 and plans for an energy union are the latest manifestations of this concern for social security driving and shaping polity-formation.

To capture the EU’s distinctive character, we therefore consider the EU as a second-order territorial space, which embeds the first-order spaces of democratic member states. EU external boundary drawing has mainly consisted in promoting and regulating geographical enlargements, i.e., accession of new member states. Individual exits from and entries into the EU territory are mainly controlled by the member states; they can freely decide how many third country nationals to admit and under what conditions. There is, however, a central system of rules as regards the equal treatment of third country nationals once they become legal residents and their secondary movements to other EU states. Collective entries (enlargements) are instead under the exclusive control of the EU.

As to internal boundaries, weakening or removing the key barriers around its member states has been a selective and nonlinear process (Scharpf, Citation2009). National boundaries still filter a significant range of intra-polity exits and entries, e.g., as regards the provision of services with a social purpose. Nonetheless, the four freedoms and the constitutional non-discrimination norm introduced increasingly stringent openings. In some domains, the EU has become the main (and even ultimate) gatekeeper, notably regarding the cross-border movement of goods, capital and persons (Ferrera, Citation2005). This is how the master tension created by the EU’s redrawing of boundaries plays out on a continuous basis. Porous and asymmetric boundaries are widely perceived to contribute to latent social crises (especially regarding intra-EU mobility, posting of workers and company relocations) and to be responsible for the refugee crisis (overburdening the capacities of frontier states, creating inhumane living conditions for refugees). These perceptions energized the ‘taking-back-control’ fervour of the Brexit campaign.

But the border regime also allows for safety valves and risk-sharing. Economic migration by unemployed young Southern Europeans, who may get vocational training and acquire skills can be helpful if they then return; sharing the responsibilities for Syrian refugees in 2015 temporarily alleviated the strain on frontier states, only to develop into an acrimonious conflict later (Kriesi et al., Citation2022). The introduction of the right to exit from the EU (Art. 50, Lisbon Treaty) – an option which is not envisaged in any democratic federation – allowed for an orderly solution to Brexit, preventing its escalation into a hugely divisive conflict among the EU-27.

Dispersed authority

Nation-states are ruled by elected governments with whom authority ultimately rests. This includes above all making and upholding the law and taking coercive action against perpetrators, implementing policies based on prior legislation. Moreover, where this authority had to be exercised to send citizens into war, political participation and social protection in the form of subjective rights had to be granted ever since the late nineteenth century (Obinger et al., Citation2018). In well-functioning democracies, a lot of power is delegated to independent authorities, however. Formally independent judiciaries and central banks have a longer history, so do charities with social care responsibilities (e.g., the church). The lines of delegation can be complex and information-asymmetric, so the idea of a clear hierarchical flow of power is too simplistic (Epstein & O’Halloran, Citation1999). But if push comes to shove, there is an institutionalized expectation that those at the top of the hierarchy should or must take responsibility.

By contrast, it is common knowledge that the EU has a weak and polycephalous (multi-headed) authority structure (Franchino, Citation2004; Pollack, Citation1997). Superimposed on a pre-existing system of established nation-states, the EU could not aspire to gain a monopolization of command at the centre, let alone a coercive one. Thus, the EU’s authority structure is characterized by a multiple separation of powers (Fabbrini, Citation2007): vertical, between different levels of authority and horizontal, between the various institutions at the centre. Binding decisions are taken without the support of a government in the traditional sense. The EU and its member states constitute a loosely coupled multi-level governance structure (Benz, Citation2010).

Our framework can overcome the long-run debate of whether the EU is a federal or a confederal polity (O’Leary, Citation2020). As Benz (Citation2010) and Fabbrini (Citation2015) have argued, the EU combines federal-like structures in the arenas of supranational policy-making, such as competition and monetary policy, and confederal structures in the arenas of intergovernmental cooperation, such as fiscal policy and cross-border policing. The EU is in this regard a unique configuration (). Contrary to Jones, McNamara and Meunier (Citation2016, Citation2021), however, the EU has not been more ‘failing forward’ than the United States (Alexander-Shaw et al., Citationin press; Rhodes, Citation2021). The EU has proved capable of autonomous and effective political production without an autonomous state-like apparatus, i.e., making collectively binding decisions followed by compliance. The authority of the weak centre has been sustained in particular by two mechanisms. There is, first, the power of a supranational legal order the norms of which have been internalized by national authorities and judiciaries and led to integration by law (Augenstein, Citation2016; Saurugger, Citation2016; Weiler, Citation1994). The role of coercion has been replaced by legal constriction. In fact, in terms of market integration the EU’s ‘law state’ has become more stringent than the US federal government (Parsons et al., Citation2021).

The second mechanism is the shared, multilevel exercise of authority that has allowed a novel type of political co-production, in which national executives participate in central policy making (including at the executive and administrative levels) along with relatively weak supranational institutions. The response to the public health crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic was a case in point (Rhodes, Citation2021; Truchlewski et al., Citation2021), as is fiscal policy coordination. In this light, the EU appears as an unprecedented case of post-coercive (and thus post-Weberian) political domination, based on the threat of exclusively legal constriction, on joint monopolization of command and on the co-production of binding decisions on the side of constituent units. We should not be surprised that achieving this is fraught with difficulties of collective action. This requires continuous (re-)stabilization in political and functional terms but it does not have to fear comparison with the United States.

The dispersed authority of the EU has indeed low democratic credentials and majoritarian accountability for its policy performance (Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006). As argued by Fabbrini (Citation2007), the compound model of democracy, based on multiple power separation, faces the structural dilemma of how to produce effective and accountable decisions without jeopardizing unity, which in turn requires the diffusion of power. The centre has only second-order input legitimacy through European elections and the confirmation process in the European Parliament. The EU quid-pro-quo of political authority, voice, is underdeveloped in terms of bottom-up individual political participation. Voice channels are selective and do not reach all the way up. The European Parliament is supposed to represent voters as Europeans and therefore to break programmatically with the national logic in political/representational terms. But it is commonly perceived as limited in transmitting popular demands. The multinational composition of Parliament that recruits disproportionately fewer representatives for voters in large member states (and vice versa in smaller members) also limits its responsiveness and accountability to voters. Executives represent the member states and their voters in the various Council formations, but the presence and influence of this chain of representation is hard to fathom by ordinary citizens. The EU level lacks a sensitive early warning system of voter discontent.

We consider the underdeveloped voice channels of the EU as a reason for why it is so susceptible to ‘backlash politics’ (Kriesi, Citation2020). The EU polity does not get continuous feedback from democratic contestation over protracted periods which can suddenly confront it with adverse referenda outcomes or obstinate governments that can bring the EU to breaking point. This has happened several times in the euro area crisis, and remains an unresolved issue in the EU regime of refugee policy.

Even so, the hybrid and weak nature of the EU centre can generate incentives for managing challenges of multi-level polity maintenance. Paradoxically, when a policy crisis escalates into a crisis of the polity itself, low democratic credentials may reduce political rivalry and free-riding on the EU’s power resources; member state representatives have incentives to stop a disintegrative dynamic (Alexander-Shaw et al., Citationin press). This does not hold for all areas of policy-making and can account for the uneven strengthening of the EU centre.

Thin bonds of loyalty and solidarity

With respect to bonding, the construction of the EU polity took place under the least favourable circumstances: mass democracy and the welfare state had greatly enhanced the bonds among their citizens and between them and their elected territorial authorities. Against this backdrop, the fundamental question thus became how the integration process could overcome the resistance against ‘system building’ (Bartolini, Citation2005, p. 386), directed against cultural standardization, hollowing out of formal political rights, and the emergence of enlarged and possibly shallower identities and social solidarity. With the end of the ‘permissive consensus’ on European integration, this kind of resistance has been increasingly politicized, as post-functionalists have pointed out (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018, Citation2019).

The evolution of bonding in the EU is ambiguous and volatile. Recent research suggests that large shares of voters would in fact support centralized forms of cross-national sharing of socio-economic adversities (Ferrera & Burelli, Citation2019; Gerhards et al., Citation2020). Solidaristic attitudes towards other member states seem to prevail over non-solidaristic ones in virtually all member states, and survey research shows that the former are not necessarily motivated by calculative expectations. However, solidarity varies by country, geographical proximity, and type of crisis (Cicchi et al., Citation2020, p. 10). Attitudes respond strongly to the institutional detail of solidaristic schemes (Beetsma et al., Citation2020). While it is difficult to establish how durable solidaristic attitudes in practice are, this research defies the stereotype of a deep cultural and social divide between a nationalist North and a solidaristic South in Europe.

Institutionally, the standard view is that the EU has real power beyond the nation-state only in the realm of regulatory market making: its capacity to affect social redistribution directly and specifically is instead very limited (Scharpf, Citation2009). This view underestimates, however, the extent to which regulation is redistributive and that transnational solidarity can work by stealth. The EU regulatory social acquis is vast. A sizeable part of regulations consists of Directives which oblige member states to introduce new social rights and standards or enhance existing ones: e.g., with respect to parental leave, employment relations, gender equality, health and safety (European Commission, Citation2016; Ferrera, Citation2005). Regulation can be used as an alternative path for pursuing distributive goals. The social security coordination regime, a set of regulations of access to and portability of social benefits for EU nationals moving across borders, is a pertinent example for this (Ferrera, Citation2005, pp. 119–124; Schelkle, Citation2017, pp. 234–251). With the increase of free movement not only of workers, but also their families, pensioners and students, the coordination regime has become de facto a system of horizontal inter-personal redistribution, whereby member states must grant resident EU citizens the same social citizenship rights as nationals. This system has served as an important mechanism of EU socialization, allowing for concrete experiences of being European (Ferrera & Burelli, Citation2019; McNamara, Citation2015a). But the identity-forming effects of EU citizenship have materialized only to a limited extent.

To a surprising extent, institutions can produce transnational ‘solidarity by stealth’, resting on relatively autonomous political-economic feedback mechanisms (Schelkle, Citation2017). The diversity of risk distributions and sensitivities within the EU increases the possibilities of reaping the benefits of risk pooling. Functional insurance mechanisms can provide promising bypasses to traditional forms of overt redistributive social protection, by pooling risks, often inadvertently, and then gradually extend its scope. The ECB’s extraordinary monetary interventions since 2007–2008 are a case in point. The political problem is that stealth solidarity may work in functional terms but fail politically because it passes unnoticed in fortunate member states and may even be resented in unfortunate recipient member states thus supported, for instance the large bailout guarantees that came with severe strings attached (Schelkle, Citation2022). The response to the Covid crisis has, however, addressed the burdensome legacy of the euro-crisis and created an openly redistributive fund to mitigate risks of the recovery from the pandemic, overcoming the political stalemate and signalling more overt loyalty and social sharing (system building).

Severe crises have repeatedly served as moments of truth about previous failed opportunities. The concrete risk of collapse of the EU polity encourages policymakers to mobilize all available institutional resources (including latent ones) for restoring or propping up the EU’s capacity to uphold system performance at the domestic level – the source of their consensus. In so doing, they also contribute to maintaining the EU as a whole (Ferrera et al., Citation2021).

The initial outputs of this strategy are typically ad hoc and/or temporary instruments: examples are the announcement of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) in Mario Draghi’s famous Whatever-it-takes speech at the height of the EA crisis, or the backup for national job retention schemes (SURE) during the pandemic. But once activated, a union of democratic welfare states mobilizes forces that push for advancements in other domains as well, especially where there already exist programmatic agendas. Thus, the European employment initiative and the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) were launched in the wake of the EA crisis. They can serve as frameworks for further measures when another emergency arises.

Between fragility and resilience: the EU as a compound polity of nation-states

All political systems are dynamic, incomplete work-in-progress, subject to ongoing political development. The state-building literature has shown that this process was indeed contested, uneven and contingent, with no master plan (Kelemen & McNamara, Citation2021, p. 20). It is always part of larger macro-social and geopolitical shifts, secularization and colonization in the case of European state-building. Similarly, European integration can be viewed as part of a larger conflict, opposing in the extreme the losers of openness or the ‘left behind’ to the winners of openness or ‘cosmopolitan elites’ (Kriesi et al., Citation2006).Footnote5

At the same time, it is ‘without rival the most ambitious and successful example of voluntary international cooperation in world history’ (Moravcsik, Citation2012, p. 64). The fact that the EU polity has been able to move beyond a confederation in a number of domains can only reinforce this judgement. Integration has been able to embed pre-existing national polities – in the absence of a founding constitution – by deploying unprecedented, creative and flexible institutional solutions. This ‘experimental’ mode of polity formation is open-ended, which can result in failures and is inherently crisis-prone. But this policymaking mode may also contribute to polity maintenance or its further strengthening. The key site of political and institutional innovation is the EU’s weak centre that forces it into political co-production with the Council and the various comitology procedures (Türk, Citation2021). The transfer of core state powers to ‘Brussels’ can be mitigated, for example, from both a functional and political viewpoint, by preserving a role for member states in the exercise of the formally transferred powers, including those of independent agencies. For instance, the ECB has proven to be surprisingly responsive to shifting priorities and needs of member states (Moschella, Citation2022, pp. 10–12).

This view shares with most scholars in the state-building tradition that EU cooperation has passed the threshold to sharing sovereignty in a polity. But their reference point is still a telos or finalité of European integration in a fiscal federation as we know it. They argue that, in contrast to the United States, the EU has too little hierarchy between centre and states (Henning & Kessler, Citation2012) and needs completion by a fiscal union (Krugman, Citation2013) and/or embedding in a political union (McNamara, Citation2015b), to take three prominent examples. The EU polity is an immature, deficient compound nation-state of which the US is the mature, complete version. And yet, it would be difficult to argue that the US can act as this ideal to which the EU must aspire. The fiscal relationship between the federal government and the states is dysfunctional (Rodden, Citation2005). Political union does not guarantee political unity as the obstructive polarization between the two mainstream parties proves. These analyses, with their benchmark of an idealized version of the nation-state, can explain why the EU has had a succession of severe crises, but not how it has pulled through. We try to explain both.

Maintaining the EU polity in crisis

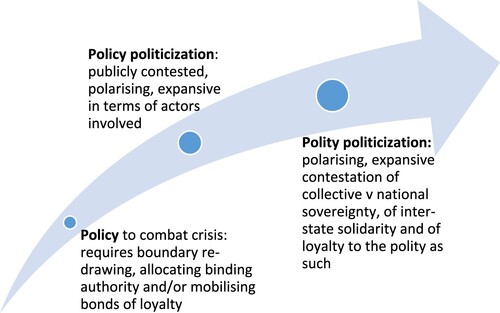

How do these elements of the EU’s compound polity relate to conflicts over sovereignty, solidarity and identity? The foundational conflicts erupt when politicization of a policy (crisis) escalates into polity politicization, meaning that conflicts about the EU’s raison d’être become salient, polarized and involve a large range of actors or venues (Hutter & Grande, Citation2014, p. 1003). The following figure distinguishes the steps ().

The potential for this escalation and the second-order loyalty on which the EU can ultimately rely is what makes the compound polity so crisis-prone. But this very constellation also produces incentives for all institutional actors to focus their attention on polity maintenance (Alexander-Shaw et al., Citationin press; Ferrera et al., Citation2021). A critical mass among member state representatives then tends to engage in endorsing policies that address the weakness and the fragility of the polity as such. They also communicate the necessity of such responses in parliaments and national media, including in other member states. If the search for ways of maintaining the polity succeeds, Rokkan’s master tension between external opening and political de-structuring requires EU-level compensation that does not ‘fix’ the EU’s weaknesses in the image of an ideal-type nation-state, but mobilizes their hidden strengths. After all, hard boundaries, centralized authority and strong loyalty to national community are all features that exclude outsiders, close minds and trigger conflict.

The contestation over who decides about a policy (sovereignty), who gets what when and how from the policy (solidarity) and who we, the addressees of a policy, are (identity) can arise over any element of the polity: boundaries, authority and loyalty. summarizes the diagnoses that follow from our perspective for four crises.

Table 2. Novel polity features and foundational conflicts.

So far our project studied four ways in which the polity has been defended and maintained when the polity as such, not any particular policy failure, comes under attack.

First, public rhetorical action was used to shore up confidence in the polity in both the EA crisis and in the pandemic, stating a commitment to the polity that was congruent with policy decisions. Speeches in particular fora and interviews in national newspapers of other countries were used to influence public opinion, legislators and market participants (Ferrera et al., Citation2021; Schelkle, Citation2021). Polity maintenance, while in essence a task to rein in political escalation, must address both the economic-functional and the political calamity that the polity finds itself in. The most notorious example for a public rhetorical action was ECB President Draghi’s Whatever-it-takes speech. While his speech stopped capital flight out of the euro and brought risk premia down, it could not stop the opening up of deep divisions between countries. Ferrera et al. (Citation2021) have shown in detail how Chancellor Merkel engaged rhetorically in polity maintenance, through a communicative strategy aimed at eliciting political and ethical commitments to ‘togetherness’ and further integration, over and above ordinary policy disagreements. This strategy legitimized the U-turn with respect to the fiscally orthodox stance that Merkel’s governments had taken during the sovereign debt crisis in the early 2010s, preparing the ground for the launch of a Franco-German proposal for a large recovery fund of grants in May 2020. While Merkel’s change of tack was crucial, there is also evidence that leaders of all five big countries (France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain) engaged in public deliberations of various policy proposals (Truchlewski et al., Citation2021).

Brexit and the refugee crisis revealed a second strategy for responding to polity conflicts: containment through externalization. The EU’s red line of ‘the integrity of the Single Market’ signalled that the jurisdiction of the European Court could not be compromised and that the Northern Ireland Peace Agreement, with its stipulation of ‘no borders on the island of Ireland’, would require the UK to give up national sovereignty over the territory in trade terms (Altiparmakis et al., Citation2022). In this case, externalization was successful, presumably because the conflict over sovereignty concerned a country that left the EU (Closa, Citationin press). This was not a foregone conclusion: Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty had introduced a clause that does not exist in other democratic federations: the right of exit from the Union. Theoretically, this clause created a breach in the closure constellation, which the Rokkan-Hirschman model deems so important for political structuring. Yet, the risk of disintegration was averted by exploiting dispersed authority: the negotiation process was centralized in a Task Force accountable to the Council as the ultimate decisionmaker which the Task Force urged to tie its hands tightly (Altiparmakis et al., Citation2022). This kept the member states together and protected the interests of the most affected countries through legal engineering and institutional innovation that dealt with transitional issues (Fabbrini, Citation2021). The Brexit process created a different political entity (‘EU27’) that immediately took steps to launch a Conference on the future of Europe and to further common foreign, security, and defence policies (CFSDPs) – steps that were previously vetoed by the UK. The EU’s porous borders also allowed preserving an international peace settlement at the cost of the integrity of the United Kingdom: the Northern Ireland protocol implies effectively that only Great Britain left the Single Market. If the EU had been a nation-state, this would have amounted to territorial annexation. In this case, a British Prime Minister signed this re-drawing of national borders voluntarily to serve his cause of ‘getting Brexit done’.

The externalization strategy worked less well in the refugee crisis (Kriesi et al., Citation2022). The outright refusal of Hungary and Poland to accept a quota regime adopted with qualified majority has led the EU to agree with Turkey’s authoritarian regime the provision of shelter for more than three million refugees. The open defiance of collective sovereignty and authority by existing member states is an unstable and politically embarrassing suppression of the crisis. All three elements of the EU’s compound polity conspire against a solution of this hard policy problem of protecting the human rights of refugees against a political backlash in national democracies (Kriesi, Citation2020).

The third strategy could be observed in the dual crisis of the pandemic and consisted in exploiting the strengths of the EU’s weak centre in polity maintenance. The dispersed and generally limited policy resources of the EU combined with the Commission’s status as a non-elected bureaucracy allows for a constructive political dynamic: member states come to rescue the centre because it is not a party-political rival. Its very fragility provides incentives to prop it up so that it can serve its essential purpose of concertation and moderation in crisis management. The establishment of the European Health Union provides an emblematic example of how, even during an emergency, authority can be rapidly reconfigured in scope and infrastructure without undermining the demands of democratic compoundness: member states maintained the right to control the delegated and administrative decisions of the Commission. The new system has proved to be rather effective in underpinning and coordinating public health measures (Quaglia & Verdun, Citation2022). The contrast with the United States was stark, both under the Trump and the Biden administration (Alexander-Shaw et al., Citationin press; Rhodes, Citation2021).

The contrast between Brexit and the refugee crisis suggests that functional polity maintenance is necessary but not sufficient to contain escalating politicization. Functionally, the EU’s unique configuration as a polity can turn into a source of strength. Brexit was a potential crisis that did not materialize. But it is questionable whether this success has improved the citizens’ political identification with the EU. This observation has wider significance. Citizens must also perceive the EU as a guarantor of their well-being, complementing the member states’ limited capacities. Crises offer opportunities for meeting or disappointing these expectations, and the very fact of a crisis stacks the cards against the perception of opportunity. A poly- or perma-crisis hardly commend a polity to its members. Moreover, the EU has to ‘produce community’ with both hands tied by the constraining dissensus regarding European integration, on one side, and the Treaties’ institutional asymmetry in favour of market rather than political integration, on the other (Scharpf, Citation2009). Even so, our empirical illustrations show that the outcome of this uphill struggle is open-ended. Between outright failure and deeper integration there is also an intermediate scenario: resilience without ostentatious change. And this can mean gradual constructive transformation or mere survival in anticipation of the next crisis. Research in the institutionalist tradition is required to find out what prevails.

Conclusion: crisis as a lens of studying polity-formation

Crises are the ‘hard times’, as Gourevitch (Citation1986) famously put it, that reveal the underlying conflicts characterizing a polity. But studying a polity during periods of crises is a particular analytical lens that needs to be justified. It may give us a distorted view of how clumsy, resolute or overbearing the supply side of EU policy-making is, depending on one’s point of view.Footnote6 It may also be biased in its assessment of the demand side of politics, depending on whether it captures the ‘rallying-around-the-flag’ phase of crisis interventions or the protest of minorities with intense preferences, typically against such interventions. Our conceptual and analytical reasons for focusing on the EU’s crises is the politics in time problem of historical-institutionalist research (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010; Pierson, Citation2004). Polities develop slowly. Their institutional staying power and own momentum makes it difficult to assess how robust or fragile their edifice is. Crises are critical junctures in which the alternative paths to the status quo – and the status quo preserving forces – become visible, even if other paths are not taken (Capoccia & Daniel Kelemen, Citation2007; Schelkle, Citation2021).

The outcome is not a foregone conclusion. Crises may end with a deep political malaise from which the polity never fully recovers, as historians may find out later; the euro area showed symptoms of this malaise. An adverse scenario was a distinct possibility: a series of national crises due to EU policy failure that would end in a full-scale ‘political attack’ on the union, to use Schimmelfennig’s (Citation2022) pertinent term. This has not come to pass and seemed a less likely prospect in 2022 than it was around 2017 shortly after the Brexit referendum and as recent as early 2020, when EU member states failed to respond to Italy’s demand for assistance in the first Coronavirus outbreak. We do not see the EU’s crises as a blessing in disguise and still think they are Monnet’s curse.Footnote7 That the delayed response in 2020, with the New Generation EU reform package, was ostentatiously solidaristic is a measure of how dismal and antagonizing the early response was. But we should also not lose sight of the fact that regularly disappointing early responses have so far not broken the process of European integration either. On the contrary. The notion of polity-formation and maintenance through various means can explain this without taking recourse to the teleology of ‘ever closer union’. It requires, however, to analyze the very same features as contingent sources of political strength that most scholars diagnose as determinants of failure.

A less orthodox reading of the Rokkan-Hirschman model can tell us that in a compound polity of democratic welfare states, we can no longer read the causality primarily from external closure to political structuring. In post-war Europe, public authority must be earned, it cannot be asserted behind hard borders. Citizens expect that their voice is heard and systems of social sharing are built for which they pay taxes after all. The three strategies illustrated above have kept the policy together despite existential challenges. They have revealed counter-intuitive strengths of an inherently crisis-prone polity structure. Community building is currently shaped by the transnational and vertical conflicts at the EU-level and by the confrontation between the supporters of integration and the supporters of demarcation in each member state, which feeds inter-state conflicts. As the most recent response to the Covid-19 pandemic has shown, however, these conflicts are not invariably divisive.

Conflict can integrate. But why this worked when a major member state decided to leave the EU but less so when the shared obligation of protecting humanitarian migrants is at stake remains somewhat of a puzzle. While the literature has provided relevant explanations for the EU’s propensity to existential crises, it is about time to also explain how the EU polity has been maintained against the odds.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maurizio Ferrera

Maurizio Ferrera has been Full Professor of Political Science at the Faculty of Political Science, Economics and Social Sciences (SPES) of the University of Milan since 2003.

Hanspeter Kriesi

Hanspeter Kriesi is part-time professor at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy, where he was the Stein Rokkan Chair holder at the Department of Political and Social Sciences from 2012 to 2020.

Waltraud Schelkle

Waltraud Schelkle holds the Joint Chair in European Public Policy at the Robert Schuman Centre and the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the European University Institute since 2022.

Notes

1 Milward (Citation2000) argues that integration was launched in order to re-legitimise the political form of the nation state: (1) show their capacity to promote growth and its fiscal dividends through free intra-EU market transactions and movements; and (2) bolster their ability to maintain internal and external political stability by joint decisions or organised collaboration in some policy areas.

2 We refer here to a contingent credit line from the sovereign bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), for health care costs, without conditionality; SURE, a fund that helped member states to introduce job retention schemes during the pandemic; and the New Generation EU funds that help with massive concessionary loans and grants.

3 There are exceptions, notably Genschel and Jachtenfuchs (Citation2014, Citation2018), Schelkle (Citation2017) and Schimmelfennig (Citation2022).

4 For instance, the right of petition and access to an Ombudsman, European citizen initiatives, the right to accessing formal documents.

5 Scholars have used different labels to refer to this new structuring conflict at the domestic level – from ‘GAL-TAN’ (Hooghe et al., Citation2002), ‘independence-integration’ (Bartolini, Citation2005), ‘universalism-communitarianism’ (Bornschier, Citation2010; cf. Zürn & de Wilde, Citation2016; Vries, Citation2017) to the cleavage between sovereignism and Europeanism (Fabbrini, Citation2019, p. 62f.). All these authors emphasize that conflicts over Europe have been transferred from the backrooms of political decision-making to the public sphere.

6 This is the topic of a recent literature on ‘crisis exploitation’ and contrived ‘emergency politics’ by member states and EU institutions (Boin et al., Citation2009; Rhinard, Citation2019 and White, Citation2015).

7 The curse is Jean Monnet’s notorious prediction that ‘Europe will be forged in crisis and will be the sum of the solutions applied in these crises’.

References

- Abramson, S. (2017). The economic origins of the territorial state. International Organization, 71(1), 97–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818316000308

- Alexander-Shaw, K., Ganderson, J., & Schelkle, W. (in press). The strength of a weak centre: Pandemic politics in the European Union and the United States. Comparative European Politics.

- Altiparmakis, A., Kyriazi, A., Miró, J., & Ganderson, J. (2022). Forging unity: Salience, politicization and the EU’s Brexit Negotiating Position. Article, under review.

- Ansell, C., & Palma, G. D., eds. (2004). Restructuring territoriality: Europe and the United States compared. Cambridge University Press.

- Augenstein, D., ed. (2016). Integration through Law revisited. The making of the EU polity. Routledge.

- Bartolini, S. (2005). Restructuring Europe: Centre formation, system building and political structuring between the nation-state and the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Beetsma, R., Burgoon, B., De Ruijter, A., Nicoli, F., & Vandenbroucke, F. (2020). What kind of EU fiscal capacity? Evidence from a randomized survey experiment in five European countries in times of Corona. CEPR Discussion Paper(DP15094).

- Benz, A. (2010). The European Union as a loosely coupled multi-level system. In H. Enderlein, S. Walti, & M. Zurn (Eds.), Handbook on multi-level governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Boin, A., Hart, P. ’., & McConnell, A. (2009). Crisis exploitation: Political and policy impacts of framing contests. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802453221

- Bornschier, S. (2010). Cleavage politics and the populist right : The New cultural conflict in Western Europe. Temple University Press.

- Capoccia, G., & Daniel Kelemen, R. (2007). The study of critical junctures: Theory, narrative, and counterfactuals in historical institutionalism. World Politics, 59(3), 341–369. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100020852

- Cicchi, L., Hemerijck, A., Genschel, P., & Nasr, M. (2020). EU solidarity in times of COVID-19. Policy briefs; 2020/34, European governance and politics programme. European University Institute.

- Closa, C. (in press). Worse than Brexit. Defiant non-compliance on rule of law and the erosion of supranationalism. West European Politics.

- Epstein, D., & O’Halloran, S. (1999). Delegating powers: A transaction cost politics approach to policy making under separate powers. Cambridge University Press.

- European Commission. (2016). The EU Social Acquis, SWD(2016) 50 final.

- Fabbrini, S. (2007). Compound democracies: Why the United States and Europe are becoming similar. Oxford University Press.

- Fabbrini, S. (2015). Which European Union? Cambridge University Press.

- Fabbrini, S. (2019). Europe’s future: Decoupling and reforming. Cambridge University Press.

- Fabbrini, F. (2021). Brexit and the future of the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Ferrera, M. (2005). The boundaries of welfare. Oxford University Press.

- Ferrera, M. (2020). Mass democracy, the welfare state and European integration: A neo-Weberian analysis. European Journal of Social Theory, 23(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431018779176

- Ferrera, M., & Burelli, C. (2019). Cross-National solidarity and political sustainability in the EU after the crisis. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(1), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12812

- Ferrera, M., Miró, J., & Ronchi, S. (2021). Walking the road together? EU polity maintenance during the COVID-19 crisis. West European Politics, 44(5-6), 1329–1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1905328

- Follesdal, A., & Hix, S. (2006). Why there Is a democratic deficit in the EU: A response to Majone and Moravcsik. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(3), 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00650.x

- Franchino, F. (2004). Delegating powers in the European community. British Journal of Political Science, 34(2), 269–293. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123404000055

- Genschel, P. (2022). Bellicist integration? The War in Ukraine, the European Union and core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(12), 1885–1900. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141823

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2014). Beyond the regulatory polity? The European integration of core state powers. Oxford University Press.

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2018). From market integration to core state powers: The eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis and integration theory. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(1), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12654

- Gerhards, J., Lengfeld, H., Ignácz, Z., Kley, F., & Priem, M. (2020). European solidarity in times of crisis. Insights from a thirteen-country survey. Routledge.

- Gourevitch, P. A. (1986). Politics in hard times: Comparative responses to international economic crises. Cornell University Press.

- Henning, R., & Kessler, M. (2012). Fiscal federalism: U.S. History for architects of Europe’s fiscal union. Bruegel.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

- Hix, S. (2007). The European Union as a polity(I). In K. E. Jørgensen, M. Pollack, & B. Rosamond (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of European union politics (pp. 141–157). SAGE.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2019). Grand theories of European integration in the twenty-first century. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1113–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1569711

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310

- Hutter, S., & Grande, E. (2014). Politicizing Europe in the national electoral arena: A comparative analysis of five west European countries, 1970–2010. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(5), 1002–1018. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12133

- Jones, E., Kelemen, D., & Meunier, S. (2016). Failing forward? The euro crisis and the incomplete nature of European integration. Comparative Political Studies, 49(7), 1010–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015617966

- Jones, E., Kelemen, D., & Meunier, S. (2021). Failing forward? Crises and patterns of European integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1519–1536. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954068

- Kelemen, R. D., & McNamara, K. R. (2021). State-Building and the European Union: Markets, War, and Europe’s uneven political development. Comparative Political Studies, 55(6), 963–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211047393

- Krasner, S. (1999). Sovereignty: Organised hypocrisy. Princeton University Press.

- Kriesi, H. (2020). Backlash politics against European integration. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(4), 692–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120947356

- Kriesi, H., Altiparmakis, A., Bojar, A., & Oana, N. (2022). Coming to terms with the European refugee crisis. Book typescript under review.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2006). Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 921–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x

- Krugman, P. (2013). Revenge of the optimum currency area. In D. Acemoglu, J. Parker, and M. Woodford (Eds.). NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 2012(27), 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1086/669188

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2010). A theory of gradual institutional change. In J. Mahoney, & K. Thelen (Eds.), Explaining institutional change. Ambiguity, agency and power (pp. 1–37). Cambridge University Press.

- Mair, P. (2009). Responsible versus responsive government. MPIfG Working Paper 09/8, Cologne: Max-Planck Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung.

- Majone, G. (2016). The limits of collective action and collective leadership. In D. Chalmers, M. Jachtenfuchs, & C. Joerges (Eds.), The End of the eurocrats' dream. Adjusting to European diversity (pp. 218–240). Cambridge University Press.

- McNamara, K. (2015a). The politics of everyday Europe. Constructing authority in the European union. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

- McNamara, K. (2015b). The forgotten problem of embeddedness: History lessons for the euro. In M. Matthijs & M. Blyth (Eds.), The future of the euro (pp. 21–43). Oxford University Press.

- Milward, A. (2000). The European rescue of the nation-state (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Moravcsik, A. (2012). Europe after the crisis. How to sustain a common currency. Foreign Affairs, 91(3), 54–64.

- Moschella, M. (2022). Breaking with Monetary Orthodoxy? Central Banks, Reputation and Monetary Regimes. Typescript under review.

- Obinger, H., Petersen, K., & Starke, P. eds. (2018). Warfare and welfare: Military conflict and welfare state development in western countries. Oxford University Press.

- O’Leary, B. (2020). The nature of the European Union. In F. Duina & F. Merand (Eds.), Europe’s malaise (pp. 17–44). Emerald Publishing.

- Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations: Economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. Yale University Press.

- Parsons, C., Matthijs, M., & Springer, B. (2021). Why Did Europe’s Single Market Surpass America’s? Conference paper, ECPR Standing Group on Europe, 10-12th June.

- Pierson, P. (2004). Politics in time: History, institutions, and social analysis. Princeton University Press.

- Pollack, M. (1997). Delegation, agency, and agenda setting in the European community. International Organization, 51(1), 99–134. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081897550311

- Quaglia, L., & Verdun, A. (2022). Explaining the response of the ECB to the COVID-19 related economic crisis: inter-crisis and intra-crisis learning. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141300

- Rhinard, M. (2019). The crisisification of policy-making in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 616–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12838

- Rhodes, M. (2021). ‘Failing forward’: A critique in light of COVID-19. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1537–1554. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954067

- Risse, T. (2015). Limited statehood: A critical perspective. In S. Leibfried, E. Huber, M. Lange, J. D. Levy, & J. D. Stephens (Eds.), Oxford handbook of transformations of the state (pp. 152–168). Oxford University Press.

- Rodden, J. (2005). Hamilton's paradox: The promise and peril of fiscal federalism. Cambridge University Press.

- Rokkan, S., Flora, P., Kuhnle, S., & Urwin, D. W. (1999). State formation, nation-building, and mass politics in Europe: The theory of Stein Rokkan. Oxford University Press.

- Saurugger, S. (2016). Politicisation and integration through law: Whither integration theory? West European Politics, 39(5), 933–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2016.1184415

- Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing Europe. Effective and democractic? Oxford University Press.

- Scharpf, F. W. (2009). The asymmetry of European integration, or why the EU cannot be a ‘social market economy’. Socio-economic Review, 8(2), 211–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwp031

- Schelkle, W. (2017). The political economy of monetary solidarity: Understanding the euro experiment. Oxford University Press.

- Schelkle, W. (2021). Fiscal integration in an experimental union: How path-breaking was the EU’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(S1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13246

- Schelkle, W. (2022). Monetary solidarity in Europe: Can divisive institutions become ‘moral opportunities’? Review of Social Economy, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2022.2042728

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2022). The Brexit puzzle: Polity attack and external rebordering. West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2132448

- Tilly, C. (1975). Reflections on the history of European state-making. In C. Tilly (Ed.), The formation of national states in Western Europe (pp. 3–83). Princeton University Press.

- Tilly, C. (1990). Coercion, capital, and European states, AD 990-1990. Basil Blackwell.

- Truchlewski, Z., Schelkle, W., & Ganderson, J. (2021). Buying time for democracies? European Union emergency politics in the time of COVID-19. West European Politics, 44(5-6), 1353–1375. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1916723

- Türk, A. H. (2021). Legislative, delegated acts, comitology and interinstitutional conundrum in EU law – configuring EU normative spaces. European Law Journal, 26(5-6), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12400

- Vries, C. D. (2017). Benchmarking Brexit: How the British decision to leave shapes EU public opinion. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(S1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12579

- Weiler, J. (1994). A quiet revolution: The European court of justice and its interlocutors. Comparative Political Studies, 26(4), 510–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414094026004006

- White, J. (2015). Emergency Europe. Political Studies, 63(2), 300–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12072

- Zürn, M., & de Wilde, P. (2016). Debating globalization: Cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as political ideologies. Journal of Political Ideologies, 21(3), 280–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2016.1207741