ABSTRACT

Agencification in the EU stretches the confines of the European regulatory state to the maximum by extending to policy domains that were formerly the exclusive terrain of national institutions. Although the challenge to legitimize EU-level agencies is widely acknowledged, scant empirical research has been done on the conditions under which EU-level epistemic authority prevails or fails. To fill this gap, we examine whether EU agencies are perceived as more legitimate when the scientific nature of their regulatory outputs is made explicit and whether they start facing grave legitimacy challenges when national-level stakeholders signal disapproval with their scientific recommendations. We draw on a survey experiment with Dutch local politicians to study their legitimacy perceptions about the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and its mandate to authorize vaccines in view of cross-border health security risks. Our data suggest that the EMA is regarded as a highly legitimate agency and that disapproval by national-level politicians and citizens does not undermine its epistemic authority in the eyes of local decision-makers. This study contributes to the scholarship on non-majoritarian institutions’ legitimation imperatives by introducing novel research avenues and analytical tools to continue rigorous empirical testing of the well-established theoretical and normative claims.

Introduction

Agencification in the EU stretches the confines of the European regulatory state to the maximum by extending to policy domains that were formerly the exclusive terrain of national institutions. Although the rise of the European regulatory state has long been acknowledged (Levi-Faur, Citation2011; Majone, Citation1994; Rimkutė, Citation2021), scholars have recently observed the growth of the European regulatory security state covering policy areas such as defence, cybersecurity, border control, and health security (Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Kruck & Weiss, Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023). To illustrate, in view of the recent global health crisis, EU institutions and member states have agreed to strengthen the European Health Security Union to address cross-border health risks. A new health security framework aims to build a stronger health security capacity within the EU by extending the role of already existing EU health agencies (the European Medicines Agency [EMA] and the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control [ECDC]) and by instituting a new agency (the European Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority [HERA]) to respond to public health emergencies (European Commission, Citation2022). As a result, the three EU agencies – the EMA, ECDC, and HERA – are the core pillars of the European Health Security Union. The agencies are assigned with far-reaching risk assessment, risk communication, and/or risk management responsibilities.

Delegation of epistemic authority to EU-level agencies across various policy domains, including security, is ‘profound and incessant’ (Rimkutė, Citation2021, p. 221). However, EU agencies’ ability to deliver is conditional on their legitimacy in the eyes of national-level decision-makers, citizens, and other relevant stakeholders. Indeed, scholars have observed that the European regulatory state and its core non-majoritarian institutions (i.e., EU agencies) often face grave legitimacy issues (Braun & Busuioc, Citation2020; Rittberger & Wonka, Citation2011). Recent empirical studies, for instance, suggested that the legitimacy of EU-level agencies can be challenged when they are confronted with dissent, disapproval, or rejection at the national level (Martinsen et al., Citation2022; Rimkutė, Citation2018; Schrama, Citation2022). To illustrate, while the European Food Safety Authority concluded that bisphenol A (a chemical used in plastics) poses no health risk to consumers of any age group, several EU member states restricted the use of bisphenol A in infant feeding bottles based on citizens’ concerns, political deliberations, and national epistemic authority (i.e., scientific recommendations of a national regulatory agency). However, empirical evidence on the magnitude of the so-called authority-legitimacy gap is limited, sporadic, and based on observational data. In other words, we know little if and to what extent a gap between formally delegated regulatory authority to EU agencies and actual acceptance and compliance with EU agency regulations can be empirically observed.

Furthermore, although the challenge to legitimize EU-level non-majoritarian institutions is widely acknowledged and has received significant scholarly attentionFootnote1, scant rigorous empirical research has been conducted on the conditions under which EU-level epistemic authority prevails or fails. We have an incomplete understanding of the consequences of extensive delegation of far-reaching regulatory tasks to EU agencies: Does delegation to EU agencies result in a shift from national political authority to supranational epistemic authority or does national political authority remain the only legitimizing basis on which regulatory decisions are legitimized at the national level? To start filling this void in the literature, we examine whether EU agencies are perceived as more legitimate when the scientific nature of their regulatory outputs is made explicit and whether they start facing grave legitimacy challenges when national-level stakeholders signal disapproval with their scientific recommendations. To that end, this study generates novel theoretical and empirical insights on the legitimacy of the perpetually rising European regulatory (security) state by studying the legitimacy of the core health authority in the EU, the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Theoretically, we draw on long-established literature to introduce two sets of hypotheses on the diverse legitimation sources of non-majoritarian institutions: ‘non-majoritarian standards of legitimacy’ versus ‘derived standards of legitimacy’ (Majone, Citation1998, Citation1999). The ‘non-majoritarian legitimacy’ hypotheses are built on the argument that expertise is the raison d'être and prime foundation of authority of EU-level regulatory agencies (Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Rimkutė, Citation2022). Political decision-makers and member states delegate tasks to EU agencies to generate regulatory policy solutions that are expected to be insulated from politics and based on technical data and scientific knowledge. As a result, the provision of expertise-based outputs that lead to effective policy solutions – so-called output-based legitimacy – is the key criterion for EU agency legitimacy (Majone, Citation1998; Scharpf, Citation1999). On the contrary, the derived standards of legitimacy hypotheses originate from the argument that the legitimacy of EU agencies proceeds from national democratically elected officials or directly from EU citizens. The power of each member state and its citizens to decide is the sole legitimating component of EU agencies and their regulatory outputs.

Empirically, we rely on a survey experiment with 812 Dutch local government officials to capture the multilevel nature of EU governance. Such empirical focus allows us to gauge the challenge faced by local policy implementers to reconcile supranational regulatory recommendations and national political deliberations, as well as attend to the wishes of their direct constituencies. We provided local government officials with a hypothetical but realistic scenario: a new global pandemic has emerged, a new vaccine has been developed, and the EMA has approved the new vaccine safety and recommended its use in all EU member states. In a controlled setting, participants were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions introducing the scientific aspects of EMA’s recommendations and the contradiction between the epistemic and political (or citizen) authority foundations in a short vignette. After reading a vignette, participants evaluated the legitimacy of the EMA and its authority to issue scientific recommendations that would guide national health policies.

This article makes a relevant contribution that is at the heart of the EU legitimacy and ‘democratic deficit’ debates and, in turn, the very nature of the EU polity. It follows the observation that ‘[i]t should be obvious, but it is easily forgotten, that arguments about the democratic deficit are really arguments about the nature, functions and goals of the EC [European Union]’ (Majone, Citation1998, p. 6). We find that the EMA is perceived as a highly legitimate EU agency in the sample of elected local government officials in the Netherlands. While we do not find evidence that the explicit references to the scientific nature of EMA’s authorization decisions serve as the core legitimization foundation, our data suggest that the political reservations and citizens’ disapproval do not undermine the epistemic authority of the EMA. In this way, our study generates a novel finding that challenges the long-established normative claims suggesting that EU agencies should start facing grave legitimacy deficits when national-level political and public deliberations signal disapproval with or rejection of supranational regulators and their regulatory rules, standards, or recommendations. Our findings, on the contrary, suggest that, in view of the prevalent health crisis that calls for credible and timely health security solutions, national-level contestations do not undercut the legitimacy of the EMA. This, in turn, implies that the recent global health crisis has paved the way for a stronger European Health Security Union consisting of non-majoritarian institutions providing scientific/technical expertise to address transboundary health risks. We propose future research to examine if our findings hold in different EU member states, among diverse stakeholder groups (e.g., citizens), across time (e.g., does the legitimacy of the EMA diminish when the current health crisis is contained?), and across less-established EU health agencies (e.g., ECDC, HERA) or other regulatory agencies assigned with technical/scientific responsibilities (e.g., the European Aviation Safety Agency, the European Chemicals Agency, the European Food Safety Authority).

Theoretical framework: core concepts, context, and expectations

With the delegation of authority, a demand for legitimacy arises: ‘legitimacy only becomes an issue once an institution possesses authority’ (Tallberg & Zürn, Citation2019, p. 286). Authority refers to the recognition that an institution has the right to exercise certain powers (e.g., make decisions) that results from the delegation of powers by member states to an international organization (IO). Legitimacy, on the contrary, is defined ‘as beliefs within a given constituency or other relevant audience that a political institution’s exercise of authority is appropriate’ (Tallberg & Zürn, Citation2019, p. 285). Legitimacy entails both value- and behavior-based judgements: ‘a sense of obligation or willingness to obey authorities (value-based legitimacy) that then translates into actual compliance with governmental regulations and laws (behavioral legitimacy)’ (Levi et al., Citation2009, p. 354). To that end, positive legitimacy perceptions facilitate ‘a voluntary transfer of decision-making power to authorities and institutions’ (Mazepus & van Leeuwen, Citation2020, p. 3).

Scholars focusing on international and EU governance emphasize two diverse types of authority – political and epistemic – that are regarded as core legitimating justifications in international governance (Abbott et al., Citation2020; Zürn, Citation2018). The defining feature of political authority is political perquisite and faithful adherence to democratic procedures (Majone, Citation1997; Scharpf, Citation1999). On the contrary, the core characteristic of epistemic authority is extensive reliance on (scientific) experts, data that comply with the highest scientific standards, and rigorous methodologies to assess a wealth of data (Rimkutė, Citation2022).

In the EU context, the rise of the European regulatory state refers to the extensive delegation of epistemic authority to regulatory agencies at the EU level to carry out regulatory responsibilities (Kruck & Weiss, Citation2023; Rimkutė, Citation2020a; Citation2021). However, as Majone noted, ‘[d]emocratically accountable principals can transfer policy-making powers to non-majoritarian institutions, but they cannot transfer their own legitimacy’ (Citation1999, p. 7). In other words, the legitimacy of EU-level non-majoritarian institutions does not ensue from the mere fact that authority has been formally granted. An authority-legitimacy gap may emerge if delegated authority is not regarded as rightful (value-based legitimacy) and does not translate into actual compliance with EU-level regulations (behavioral legitimacy) by relevant national-level stakeholders. On the contrary, the authority-legitimacy gap may narrow (or even close) when EU regulatory agencies’ contributions to EU-level regulatory rulemaking are widely accepted and when EU agencies can fully exercise their epistemic authority, a particular form of power that allows EU-level regulators to influence and shape regulatory behavior in EU member states.

Against this backdrop, our theoretical framework focuses on the legitimacy perceptions of relevant audiences about non-majoritarian institutions (i.e., regulatory agencies) operating within the EU polity. We draw on the European regulatory state scholarship to introduce the mainstream legitimation sources of EU regulatory agencies (Majone, Citation1998, Citation1999). Our theoretical framework posits that EU agency legitimacy can be derived from two sources that relate to either supranational epistemic authority (non-majoritarian legitimacy) or national political authority (derived/democratic legitimacy). The non-majoritarian legitimation standards entail an inclination to submit to regulatory rules made by technical/scientific authorities that draw on expertise and experts, whereas the derived legitimation standards entail an inclination to submit to regulatory rules of supranational regulators only if they do not receive any dissent, disapproval, or rejection from relevant national-level stakeholders. Against this background, we examine the following: (1) whether the authority-legitimacy gap of EU agency governance narrows when the epistemic nature of their regulatory authority is made explicit and (2) whether the gap widens when EU agencies face objections at the national level. To that end, we draw on two sets of expectationsFootnote2 about diverse legitimation sources on which non-majoritarian institutions can draw to legitimize themselves and their regulatory outputs: ‘non-majoritarian’ and ‘derived/democratic’. In the remainder, we introduce our expectations.

The non-majoritarian standards of legitimacy

The scholarship on the evolution of the EU polity and its legitimacy imperatives has argued that the EU is primarily a regulatory state in which the emphasis shifts from political to epistemic authority of non-majoritarian institutions (Levi-Faur, Citation2011; Majone, Citation1998, p. 28). In the EU regulatory model of governance, debates about political processes are replaced with considerations on how to delegate tasks to regulatory agencies, produce credible expertise-based solutions, and tackle issues that EU member states jointly face (Wonka & Rittberger, Citation2010). The very reason why political decision-makers mandate regulatory bodies to produce regulatory outputs is to restrict political interventions, which is crucial for warranting the attainment of credible commitments. Regulatory agencies are granted a certain degree of independence and autonomy from their political superiors with the very purpose of protecting agencies and, in turn, their regulatory outputs from ‘undue’ political influence. For this very reason, the legitimacy standards of regulatory agencies shift from democratic to non-majoritarian, emphasizing the depoliticized (i.e., insulated from politics) and technical nature of regulatory policymaking (Majone, Citation1997, Citation1998, Citation1999).

Epistemic authority is regarded as the core foundation of the non-majoritarian legitimacy standards that rest on the delivery of expertise-based solutions: ‘Regulation depends so heavily on scientific, engineering and economic knowledge […] expertise has always been an important source of legitimization of regulatory agencies’ (Majone, Citation1997, p. 157, emphasis added). Specifically, ‘[r]egulatory agencies’ outputs are devised to provide an analytical means for assessing scientific knowledge regarding potential hazards and risks to humans, animals, and the environment. This, in turn, implies that regulatory agencies’ duties are primarily a highly technical quest predominantly entrenched in the use of scientific knowledge and technical data to arrive at regulatory outputs that later inform (political) regulatory decisions’ (Rimkutė, Citation2022, p. 486). In particular, when we discuss the European regulatory state and its core regulatory agents – decentralized agencies – expertise-based conduct is regarded as the be-all-and-end-all legitimation source (Bunea & Nørbech, Citation2022; Busuioc & Rimkutė, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, p. 5; Fjørtoft, Citation2020; Rauh, Citation2022; Rimkutė, Citation2020a). Insulated from politics, expertise-based regulatory outputs, therefore, are regarded as the key means through which regulatory agencies justify their legitimacy, which in turn allows them to fully exercise delegated epistemic authority.

Following the non-majoritarian legitimacy reasoning, we outline our baseline expectation. As explained by Majone, ‘[i]f one accepts the ‘regulatory model’ of the EC [European Union], then, as long as the tasks delegated to the European level are precisely and narrowly defined, nonmajoritarian standards of legitimacy should be sufficient to justify the delegation of the necessary powers’ (Citation1998, p. 5). Given the initial choice of member states to delegate tasks to EU agencies, we expect that the non-majoritarian sources of legitimation are sufficient to regard EU agencies as rightful and lead to the willingness of national decision-makers to actually comply with EU agency regulatory outputs (e.g., scientific recommendations/opinions).

Further, we argue that the legitimacy of EU agencies is strengthened and even prevails over political authority when the nature of non-majoritarian regulatory decision-making is made explicit: regulatory outputs were produced following the ‘scientific gold’ standard (i.e., reliance on the highest scientific standards and the authority of [scientific] experts and expertise) (Maor, Citation2007; Rimkutė, Citation2018). More specifically, we expect that regulatory agencies who credibly convey the technical nature of their regulatory rules, first, improve their aptitude to elicit confidence in their regulatory rules as well as promote rule-following behavior. Second, regulatory agencies that successfully elucidate the scientific/technical character of their regulatory outputs are able to warrant broader support even if they face (political) resistance at the national level. As long as EU agencies are successful in conveying their adherence to the highest technical standards in their regulatory outputs, they are regarded as legitimate because the provision of evidence-based solutions is the very reason member states delegate tasks to EU-level agencies. As noted by Majone, the legitimacy of EU agencies depends on their ability ‘to engender and maintain the belief that they are the most important ones for the functions entrusted to them’ (Citation1999, p. 22). As a result, we expect that the explicit reference to the scientific/technical nature of EU regulatory outputs (i.e., adherence to the non-majoritarian standards) narrows the authority-legitimacy gap within the European regulatory state. Furthermore, following the non-majoritarian standards of legitimacy, we expect that (political) disapproval at the national level does not widen the authority-legitimacy gap as epistemic authority is sufficient to legitimise EU regulatory agencies and their regulatory outputs.

H1: The non-majoritarian sources are necessary and sufficient to legitimize EU agencies and their regulatory outputs:

H1a: The legitimacy of EU agencies increases when the non-majoritarian nature of their regulatory outputs is made explicit.

H1b: The legitimacy of EU agencies does not decrease when their regulatory outputs receive (political) disapproval at the national level.

The derived standards of legitimacy

The argument that the non-majoritarian standards are sufficient to legitimize non-majoritarian institutions has sparked vivid debates (e.g., Eriksen & Fossum, Citation2004). The rise of the European regulatory state – accompanied by extensive delegation to EU agencies – has resulted in concerns about democratic deficit that cannot be resolved by simply referring to EU agency epistemic authority and their expertise-based conduct. Following this view, epistemic authority and expertise-based conduct cannot justify the rightfulness of supranational regulatory bodies.

As a result, scholars warning about democratic deficit problems within the EU polity noted that EU agencies should be normatively justified on the basis of democratic legitimacy standards (see, for example, Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006; Holst & Molander, Citation2019). EU-level regulatory rules, thus, can only be legitimized through ‘the standards derived from the democratic legitimacy of the Member States’ (Majone, Citation1998, p. 6).

According to the derived standards of legitimacy, the legitimacy of EU regulatory agencies (or non-majoritarian institutions in general) ensues from the democratic legitimacy of the member states (Majone, Citation1998). The only route through which EU non-majoritarian institutions and their regulatory outputs could be regarded as rightful is to derive their legitimacy through democratically elected representatives or directly through EU citizens’ approval. Only democratically accountable member state representatives can approve EU non-majoritarian institutions’ regulatory outputs before they become national laws. In this way, the entire regulatory process in the EU should be steered and controlled by sovereign democratic states and their democratic representatives elected at the national level. EU member states and their political actors or citizens, therefore, should be entitled with the veto power as they are the single-most legitimating element of the European regulatory state.

Following the derived standards of legitimacy, we expect that the non-majoritarian standards of legitimacy are not sufficient to legitimize EU-level agencies (Skogstad, Citation2003). Importantly, we expect that EU agencies start facing grave legitimacy deficits when national-level political deliberations signal dissent, disapproval, or rejection of supranational regulators and their regulatory rules, standards, or recommendations. We expect that the legitimacy of EU regulatory bodies is significantly undermined – i.e., the authority-legitimacy gap grows – in situations where relevant political stakeholders and institutions express reservations about regulatory outputs produced at the EU level. In a similar vein, we expect political decision-makers to follow the wishes of their direct constituencies rather than rely on unpopular supranational regulatory rules that receive citizens’ disapproval. The causal mechanism behind this motivation is straightforward and reflects the core defining characteristic of democracy (i.e., pro tempore) (Linz, Citation1998): Political decision-making processes are defined by high responsiveness to the prevailing constituency requests and wishes as well as a focus on short-term gains. As a result, we expect that (political/citizens’) disapproval at the national level leads to a widening authority-legitimacy gap – i.e., EU agencies start facing grave legitimacy deficits – as the adherence to the non-majoritarian standards is not sufficient to legitimise EU regulatory agencies and their regulatory outputs.

H2: The majoritarian sources have a stronger effect on the legitimacy of EU agencies and their regulatory outputs than the non-majoritarian sources:

H2a: The legitimacy of EU agencies decreases when their regulatory outputs receive disapproval from national political representatives.

H2b: The legitimacy of EU agencies decreases when their regulatory outputs receive disapproval from direct constituencies.

Methodology

Research setting and sample characteristics

The hypotheses of this study are tested by means of a survey experiment among Dutch municipal council members in the context of cross-border health security risks. We are interested in examining local politicians’ perceptions about the EMA and its regulatory task to authorize medicines in Europe on the basis of scientific evaluations of marketing–authorization applications submitted by pharmaceutical companies.

The EMA case is ideal for the purposes of this study as it engenders both the non-majoritarian (epistemic) and political nature of multilevel regulatory rulemaking and implementation. The EMA is an EU regulatory agency that produces highly scientific regulatory recommendations. However, due to the recent global health crisis, it operates in a highly salient and politicized context. Such an empirical setting enables us to gauge the effects of the non-majoritarian versus derived standards on legitimacy perceptions and empirically observe if the national political authority prevails over epistemic authority of the EMA or vice versa.

More specifically, first, the EMA is an EU-level agency that scores high on regulatory independence (Wonka & Rittberger, Citation2010) and owns far-reaching epistemic authority as the European Commission often directly accepts its scientific recommendations (Groenleer, Citation2014). Second, the core tasks of the EMA are narrowly defined and highly scientific. The ‘EMA’s scientific committees provide independent recommendations on medicines for human and veterinary use, based on a comprehensive scientific evaluation of data’ (EMA, Citation2021). Third, the COVID-19 pandemic has put the EMA in the spotlight. The EMA’s regulatory activities are at the center of national experts and political decision-makers’ discussions as its vaccine authorization decisions have a direct impact on supranational health security policy directions and, in turn, on national health policies that directly affect all EU citizens. Last but not least, in view of the COVID-19 pandemic, the EMA entered the health security domain, which is a policy area that used to be the exclusive terrain of national institutions. The EMA is the core regulatory agency contributing to the European Health Security Union that has been significantly strengthened to address cross-border health risks (European Commission, Citation2022).

As legitimacy is ‘ultimately most important in the relationship between the authorities that govern and those who are governed’ (Tallberg & Zürn, Citation2019, p. 586), we focus on legitimacy perceptions of decision-makers (political elites) that are assigned with a task to follow and implement regulatory rules generated at the supranational level. Specifically, we focus on local council members in the Netherlands, which enables us to capture the multilevel governance model of the European regulatory state. Local-level decision-makers assisting the implementation of EU rules in their communities are bound by the authority of EU-level regulators, national-level political authority, and the preferences of local community members who will bear the consequences of a supranational policy.

The Dutch context is particularly suitable to test our hypotheses as the Netherlands is a decentralized unitary state in which different responsibilities are carried out at various government levels. As a result, local level political decision-makers have discretion in deciding and/or overseeing how certain policies are implemented in their municipality. In such a context, local political decision-makers are faced with multiple challenges to reconcile supranational rules and national political deliberations, as well as attend to the wishes of their direct constituencies. This setting is ideally suited to our study for a couple of reasons. First, it allows us to examine our expectations and assess if political authority of the national-level politicians and/or the wishes of community members can undermine the epistemic authority of the EMA. Second, it reflects the very nature of multilevel governance – the defining feature of EU regulatory policymaking is that EU-level regulations must jump through multiple hoops before they are implemented at the local level. Third, it strengthens our study’s ecological validity as it focuses on actual local decision-makers who have real-world substantial experience with policy-implementation decisions that reflect trade-offs between attending to scientific recommendations, political deliberations, and direct constituencies’ preferences.

An invitation to participate in the survey experiment was sent on 26 November 2021 to the valid and publicly available email addresses of 7649 Dutch local council members (Mazepus & Rimkutė, Citation2022).Footnote3 This resulted in a response of 812 participants who took part in the online survey experiment and answered questions measuring the outcome variable (response rate: 10.6%).Footnote4 Our sample consists of 23% participants who identify as female, and the average age reported by participants is 58 years (SD = 11.84). Fifty-seven percent of the participants indicated that their party is a part of governing coalition, whereas 39% indicated that their party is a part of the opposition. Over 30% of our participants represent local parties in the municipal council. In terms of representatives of the national parties in our sample, 15% represents CDA (Christian-democratic, Christen-Democratisch Appèl), 14% VVD (liberal-conservative, Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie), 9% D66 (social-liberal, Democraten ‘66), 8% GroenLinks (green, GroenLinks), 8% PvdA (social-democratic, Partij van de Arbeid), 5% ChristenUnie, 2% SGP, 2% SP, and 2% independent representatives. Other parties are each represented by less than 1% of participants. Most of our participants (43%) indicated that they completed higher professional education (HBO), followed by participants with a university degree (35%), secondary professional education (MBO, 12%), secondary education (voortgezet onderwijs, 4%), and PhD (3%). Most participants identified themselves as being in the center of the left-right political ideology scale (M = 3.82, SD = 1.2, on a 7-point Likert-type scale from ‘1: Very left’ to ‘7: Very right’). Participants were on average supportive of the EU (M = 5.41, SD = 1.54, on a 7-point scale) and highly supportive of vaccinations (M = 6.37, SD = 1.12, on a 7-point Likert-type scale).

Appendix VI reports a comparison of our sample to the population of Dutch local council members. Our sample is on average underrepresented by participants who identify themselves with the female gender, and our participants are older than the population. Participants of our survey represent the distribution across political parties well, except for underrepresentation of the local political party members.

Experimental design and procedures

We rely on a preregisteredFootnote5 survey experiment with four conditions to examine our theoretical expectations in a sample of elected national decision-makers in the Netherlands. The experimental survey method is ideal for the purpose of our study. First, our experimental design has relatively high ecological validity, as we focused on actual political decision-makers and information about a hypothetical future global pandemic that is very similar to the current COVID-19 pandemic. We asked our participants to assume ‘that yet another global pandemic has emerged. A new vaccine has been developed to tackle the new pandemic disease. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) – an EU-level regulatory agency – has approved the new vaccine’s safety and recommended its use in all EU member states, including the Netherlands.’ To increase the ecological validity of the study, we used a factual source of credible information about the likelihood of the emergence of a new global pandemic (i.e., actual WHO warning). In the invitation to take part in the survey (Appendix I), we emphasized the following: ‘Being prepared for the future health crisis is of crucial importance because the World Health Organization (WHO) warns that another global pandemic is inevitable, and the world should be prepared for it.’ Second, the design of our survey experiment facilitates high internal validity as the diverse legitimation sources are presented in a randomized controlled setting.

Our survey experiment relies on the random assignment of participants to one of the four conditions (). First, the control group aims to measure the baseline perceived legitimacy of the EMA and presents a simple scenario in which the EMA issues a vaccine recommendation in the context of a new pandemic.

Table 1. Experimental groups.

The second experimental group aims to estimate the perceived legitimacy of the EMA when the technical nature of the EMA’s regulatory activities is made explicit through information about the scientific evaluations used to arrive at the recommendation. For this purpose, the scenario adds information about scientific standards followed to arrive at scientific recommendation to the baseline scenario. To draft this condition, we relied on the actual scientific practices that the EMA followed to assess the COVID-19 vaccines (EMA, Citation2022).

In the third experimental group, we aimed to contrast the epistemic EMA authority with the national political authority. To that end, after introducing the baseline and epistemic authority texts, we added a short text signaling the disapproval of national-level politicians with the EMA’s scientific recommendations on the basis of political considerations. In a similar vein, in the fourth group, we contrasted the EMA’s epistemic authority with the wishes of direct constituencies of local politicians.

After exposure to one of the four experimental scenarios, we measured the outcome variable (i.e., perceived value-based and behavioral legitimacy of the EMA), followed by comprehension checks for the four experimental conditions.

Comprehension check. We used a comprehension check question to evaluate whether the participants understood the scenarios as intended and picked up on the relevant information manipulating the sources of legitimacy. Out of 724 participants who answered this question, 366 (51%) answered correctly. The comprehension check was relatively demanding (see Appendix V). As specified in the preregistration, we ran our tests with the full sample (presented in the main text) and with the restricted sample of participants who answered the comprehension check correctly (Appendix VIII). The results of both analyses are very similar.

Balance check. provides an overview of the experimental groups. Hypotheses will be tested by comparing legitimacy perceptions between the four groups. To this end, Appendix VII reports a balance check with regards to participants’ gender, age, and political ideology (measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘1: Strong left’ to ‘7: Strong right’). One-way ANOVA tests indicate that random assignment to experimental conditions has been successful (i.e., we can reject the hypothesis that the experimental groups differ with regards to the demographic variables).

Table 2. Overview of experimental groups.

Operationalization of the outcome variable: perceived legitimacy of the EMA

We measured our outcome variable using four survey questions that tap into legitimacy models proposed by Levi et al. (Citation2009). The questions capture two dimensions of legitimation perceptions: (1) a sense of duty and willingness to obey regulatory authorities and their regulatory outputs – value-based legitimacy – and (2) willingness to actually comply with and implement outputs of regulatory agencies – behavioural legitimacy. We adapted Levi et al.’s (Citation2009) survey statements to our research context (see Appendix IV). We measured the value-based legitimacy of the EMA with the statement: ‘The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has the right to approve new vaccines for the use in the EU Member States, including the Netherlands’. To capture behavioral legitimacy, we relied on three statements. While the first statement measuring behavioral legitimacy aims to capture the general willingness to comply (‘I would support the recommendation of the EMA to use the new vaccine in my municipality’), the second and third statements measure concrete forms of compliance – that is, encouraging and assisting the vaccination administration (‘Following the recommendations of the EMA, I would encourage the citizens of my municipality to get vaccinated’; ‘Following the recommendations of the EMA, I would contribute to the effective vaccine administration in my municipality’). All outcome variable questions are measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘1: Strongly disagree’ to ‘7: Strongly agree’.

Responses to all four legitimacy statements were strongly correlated (between .72 and .89), which allowed for creation of a reliable scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .95). Therefore, we created a legitimacy index that averaged participants’ answers across the four measures and used this index as our outcome variable in the models.

Analysis and results

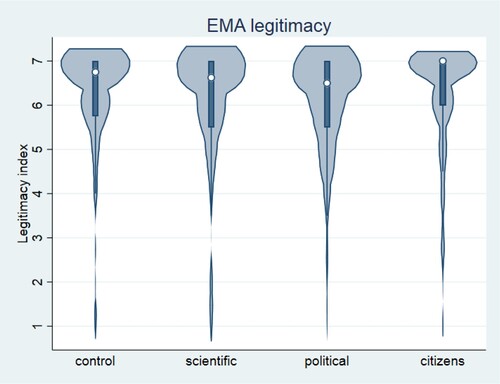

We begin our analysis by discussing the distribution of our outcome variable before moving to hypotheses testing. reports a very high level of legitimacy assigned to the EMA across experimental conditions (M = 6.04, SD = 1.41). This suggests that, overall, the EMA and its scientific recommendations are perceived as highly legitimate. On average, our participants agree that the EMA has the right to approve new vaccines. Furthermore, municipal council members, on average, are very inclined to follow the recommendation of the EMA in order to ensure public health in their community. On the basis of the EMA’s scientific evaluation, Dutch local politicians would encourage the citizens of their municipality to get vaccinated and would contribute to the effective vaccine administration in their municipality.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for the legitimacy index score per experimental group.

We tested our hypotheses by means of t-tests to compare the differences of legitimacy perceptions between different experimental conditions. Given our theoretical expectations, we should observe the following to conclude which of the two legitimation sources prevails. To support our non-majoritarian hypotheses, we should observe: (a) increased legitimacy perceptions in the epistemic authority condition compared to the control condition; (b) no difference in legitimacy assigned to the EMA in the epistemic authority condition and conditions where the EMA’s scientific recommendations are rejected by the national-level politicians or citizens. On the contrary, to support our derived legitimacy hypotheses, we should observe: (a) legitimacy assigned to the EMA in the condition where national politicians disagree with the EMA’s recommendation is lower than in the epistemic authority condition; (b) legitimacy assigned to the EMA in the condition where citizens disagree with the EMA’s recommendation is lower than in the epistemic authority condition.

We did not find support for H1a that providing information about the scientific evaluation conducted by the EMA increases the perceived legitimacy of the EMA. On average, participants who read the text stating that the EMA has approved the use of the vaccine perceived the EMA as similarly legitimate (M = 5.99, SE = 0.11) to those who read the text with more information about the scientific standards used by the EMA to arrive at its recommendation (M = 5.93, SE = .11). The difference, .05, BCa 95% CI [−0.241, 0.360], was not significant t(408) = 0.39, p = .697.

Our empirical analysis suggests that national level reservations do not undermine the legitimacy of the EMA. Specifically, first, we did not find evidence that the political reservations of national-level politicians about the EMA recommendation decrease the epistemic authority of the EMA (H2a). Participants who read the scenario in which the EMA’s scientific standards were emphasized and the national politicians rejected the recommendation regarded the EMA as highly legitimate (M = 6.03, SE = 0.09) and at a very similar level to those who read the scenario without the national politicians’ disapproval of the EMA scientific recommendations (M = 5.93, SE = .11). The difference, −0.10, BCa 95% CI [−0.380, 0.180], was not significant t(399) = −0.702, p = .483.

Second, we did not find evidence that the objection from the local constituency against the EMA recommendation decreases the epistemic authority of the EMA (H2b). Participants who read the scenario where the EMA’s scientific standards were emphasized and the local community rejected the vaccine recommendation regarded the EMA as highly legitimate (M = 6.19, SE = 0.09) and at a very similar level to those who read the scenario without the local community’s rejection (M = 5.93, SE = .11). The difference, −0.26, BCa 95% CI [−0.533, 0.018], was not significant t(410) = −1.83, p = .067. The small effect (d = 0.18) indicates that there was a 0.18 standard deviation difference in legitimacy assigned to the EMA between the groups. Contrary to our expectation, participants faced with the objection against the vaccine recommendation by the local constituency held the EMA in higher regard than those who did not face such objection. shows the distribution of legitimacy index scores across conditions.

Figure 1. Violin plots for the index of legitimacy of the EMA (averaged answers to four questions measuring legitimacy on the scale from 1- 7, where lower scores indicate lower legitimacy). The white dot shows the median, the grey bar shows the interquartile range, and the vertical line extends to the highest and lowest value. The violin shows the estimated kernel density.

We further tested whether the effect of our treatments varied across different levels of support for the EU and across left–right political orientation. Our model shows no significant interactions between our treatment and support for the EU (Table 2A, Figure 2A in Appendix IX). We found no significant effects of political orientation or interaction effects between political orientation and our experimental conditions (Table 3A, Figure 3A in Appendix IX).

Discussion and conclusion

In view of the rise of the European regulatory security state, as illustrated by the recent development in the European Health Security Union, this study aimed to examine if we are witnessing a widening authority–legitimacy gap unfold: Is the extensive delegation of regulatory authority to EU-level non-majoritarian institutions followed by legitimacy deficits that undermine supranational regulators’ ability to fully exercise their epistemic authority? Or, on the contrary, with delegation, do we observe a move from national political authority to supranational epistemic authority within the European regulatory (security) state? To that end, we examined if the non-majoritarian standards (i.e., explicit references to the scientific nature of regulatory outputs) are sufficient to legitimize EU agencies and their outputs or, on the contrary, whether the national majoritarian standards remain the core legitimizing foundations provided a confrontation between the two legitimation standards emerges. In so doing, this study contributes to the scholarship on EU legitimation imperatives that is marked by theoretical affluence but lacks rigorous empirical evidence.

Our data suggest that the EMA is highly legitimate – holds a reservoir of support leading to willingness to accept and comply with its scientific recommendations despite the national-level discussions discrediting its authority. In view of the global health crisis, our data imply that the EMA was able to gain voluntary acquiescence from the Dutch local office holders. However, contrary to our expectation (H1a), we found that emphasis on the scientific nature of the EMA’s regulatory recommendations does not increase its legitimacy. We assume that this finding might be related to the fact that the EMA is a well-known EU agency (created in 1995) that holds a solid track record as well as a positive technical reputation among political elites. Scholars have observed that the EMA engages in extensive communication activities emphasizing the technical and scientific character of its regulatory responsibilities (see Rimkutė, Citation2020a, p. 398). Furthermore, in view of the global health crisis, the EMA did its utmost in communicating about the scientific standards and procedures followed to approve COVID-19 vaccines (EMA, Citation2022). As a result, we assume that the EMA and its regulatory outputs might have been automatically associated with the scientific gold standard and excellent scientific performance during the recent pandemic by the local council members in the Netherlands. Therefore, the additional information explicating the technical nature of the EMA’s activities did not have a statistically significant effect on legitimacy perceptions. Future research should explore this tentative explanation by comparing the legitimacy of well-known and highly reputable agencies with new and less-reputable agencies.

Furthermore, we found that the presence of national level dissent (disapproval originating from the national-level political authorities (H2a) and citizens (H2b)) does not undermine the legitimacy of the EMA. The participants of the survey tend to rely on the scientific evaluation of the EMA rather than draw on Dutch national-level politicians’ deliberations that result in advice against the EMA’s scientific recommendations. In a similar vein, Dutch local council members in our sample were inclined to follow the scientific verdict of the EMA irrespective of the fact that the majority of citizens in their municipalities – direct constituencies – do not trust and do not intend to follow the EMA’s scientific recommendations. This suggests that Dutch local politicians in our sample are prone to adhere to the scientific recommendations of the EMA in order to guard public health in their community. We should be cautions, however, when generalizing our findings to the population of Dutch local politicians because the demographic characteristics of our sample – despite a random sampling strategy targeting the entire population of local decision-makers – slightly deviate from the population in terms of age, gender, and local party membership.

Our study scores high on internal validity and provides relevant observations that are in line with the existing literature. Our data suggest that the predominant sources of the EMA’s legitimacy are in line with the tenants of the European regulatory state (cf. Busuioc & Rimkutė, Citation2020a; Rimkutė, Citation2020a). EU-level non-majoritarian institutions are mandated to deliver credible and timely science-based solutions to severe societal risks, and if EU agencies successfully deliver on their core responsibility in the polity, they are expected to score high in terms of legitimacy in the eyes of relevant stakeholders (Majone, Citation1998, Citation1999). EU non-majoritarian institutions, such as EU agencies, being deprived from direct coercive regulatory powers instead draw on the indirect modes of regulation (i.e., regulation by information) (Majone, Citation1997). Provided that EU agencies hold a positive reputation for the provision of credible solutions, ‘soft’ regulation may extend to ‘hard’ regulation instruments.

Our study provides empirical support for the claim that the European regulatory security state, more specifically the European Health Security Union, is rising and transitioning from national political authority to supranational epistemic authority (Kruck and Weiss, Citation2023). In contrast to the theoretical claims and normative warnings about the widening authority–legitimacy gap, we observed the opposite: the political reservations of national-level politicians did not undermine the legitimacy of EMA’s scientific recommendations in the eyes of local-level political elites in our sample. If this empirical observation holds in different research settings (e.g., across EU member states, different regulatory agencies, diverse stakeholder groups), one could conclude that the epistemic authority of the EU polity is perceived as legitimate and that the authority-legitimacy gap of the European regulatory (security) state is closing.

However, at the same time, whereas high legitimacy levels are regarded as positive in terms of regulatory rule effectiveness that is crucial ‘during periods of scarcity, crisis, and conflict’ due to the urgent need to provide timely solutions (Tyler, Citation2006, p. 375), one should remain vigilant about the wider implications of far-reaching epistemic authority. As argued by Bertelli and Busuioc (Citation2020), reputation-sourced authority can undermine political principals’ power and incentives to oversee regulatory rulemaking. This, in turn, could be alarming because, although the independence of regulatory agencies from the ‘undue’ political influence of (supra)national majoritarian actors is within the boundaries of the European regulatory state, the inability to hold them accountable for their outputs, processes, and behavior has not been envisioned by the creators of EU agencies.

We have provided the very first empirical test of the well-established claims about the non-majoritarian versus derived legitimation sources on which EU agencies can be regarded as rightful regulators. We invite future studies to further explore if our empirical findings and conclusions hold in different empirical settings. We conducted our study in a global health crisis setting, focusing on political elite perceptions, and in a country that scores high in vaccination rates in its population. These factors may constitute favorable conditions for the high EMA’s legitimacy scores. First, scholarship focusing on International Organizations’ (IOs) legitimacy and authority in the midst of crises has convincingly demonstrated that the crisis politics of IOs can create conditions under which IOs obtain more legitimacy and authority – that is, more favorable perceptions about their roles and contribution that may even result in extended mandates (Kreuder-Sonnen, Citation2019). Second, recent studies have discovered an elite–citizen gap in terms of legitimacy perceptions of IOs; that is, political elites are inclined to consider IOs as more legitimate than the general public (Dellmuth et al., Citation2021). We expect that legitimacy perceptions across diverse stakeholder groups (e.g., professional peers, scientific experts, private interest group representatives) may also vary. Third, the Netherlands scores relatively high on institutional trust and low on vaccine hesitancy and refusal (Toshkov, Citation2022), which could have resulted in findings that are skewed towards more positive legitimacy perceptions about the EMA’s vaccine safety recommendations. Against this backdrop, we call for replication of the study among diverse stakeholder groups (e.g., citizens, professional peers, private interest groups) and in different EU member states. Furthermore, one should study if the EMA (or other [health] authorities) uphold the same legitimacy scores beyond the crisis situation: Does the legitimacy of the EMA diminish when the current health crisis is contained? Does the successful handling of the crisis leave long-lasting effects on the agency’s legitimacy?

This study opens multiple avenues for researchers to continue rigorous empirical testing of the theories of EU legitimacy using experimental methods. We only scratched the surface by empirically examining the very core claims within the scholarship of non-majoritarian institutions’ legitimacy. We invite scholars to further explore the conditions under which non-majoritarian institutions and their regulatory outputs can be legitimized in the eyes of multiple audiences. We put forward the following research avenues. First, although our study explored the interaction effect between supranational epistemic authority and national political authority, the individual effects of the national political authority were outside the scope of this study. Future studies could test if political contestations at the national level decrease regulatory agencies’ legitimacy in the cases where the scientific character of non-majoritarian regulatory decision-making is not made explicit. We also suggest strengthening the derived legitimacy treatment, for example, by matching its length and strength to the non-majoritarian legitimacy treatment employed in this study. Second, although EU-level regulatory agencies can face contestations from both supranational and national political institutions in real life, we only focused on examining whether the epistemic authority of supranational agencies can be undermined by national-level political authority. Future studies could include political contestations aimed at discrediting supranational epistemic authority at both levels to test if level-specific political objections discredit EU-level epistemic authority. Third, one additional future research line could be to contrast different levels of epistemic authority to test whether national-level regulatory agencies are regarded as more legitimate than EU-level agencies in case of disagreement between them: Does national epistemic authority prevail over supranational epistemic authority? Fourth, future studies could explore the effects of other aspects of non-majoritarian standards than those examined in this study (i.e., the scientific character of regulatory agencies’ activities). For instance, scholars could further explore if diverse degrees of independence of regulatory agencies from their political principals or the timely delivery of effective regulatory solutions are relevant factors in terms of gaining, maintaining, and enhancing legitimacy vis-à-vis a diverse set of stakeholders. Last but not least, our data suggest that bureaucratic reputation may have legitimacy-related implications. Indeed, bureaucratic reputation theory has put forward a novel hypothesis – or even an assumption – that a positive bureaucratic reputation of regulatory agencies leads to increased legitimacy vis-à-vis relevant regulatory audiences. So far, this proposition has not been put to a rigorous empirical test regardless of its theoretical and empirical potential to change the way we theorize about the European regulatory state and its core regulatory institutions.

Acknowledgements

This article was presented at ‘The Rise of the Regulatory Security State in Europe’ workshop (funded by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation) in Munich, 12–13 November 2021, ECPR General conference in Innsbruck, 22–26 August 2022, and internal research seminar at Leiden University. We would like to thank the participants of the conferences – Anke Obendiek, Timo Seidl, Catherine Hoeffler, Daniel Mügge, Sandra Eckert, Martin Lodge, Takuya Onoda, Kutsal Yesilkagit, Ken Meier, Andrei Poama, Dimiter Toshov, Johan Christensen, and Eefje Cuppen – and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. We would also like to thank the editors of the special issue, Andreas Kruck and Moritz Weiss, for their excellent suggestions and guidance. Last but not least, we thank Joris van der Voet for introducing us to the Dutch context as well as his invaluable methodological advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at osf.io/qhtg9 [doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/QHTG9]

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Reservations about extensive delegation to EU-level regulatory bodies resulted in rich theoretical, conceptual, and normative contributions on how EU non-majoritarian institutions and their regulatory authority are or could be legitimized (e.g., Busuioc & Rimkutė, Citation2020b; Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006; Majone, Citation1998, Citation1999; Schmidt & Wood, Citation2019). Furthermore, contested legitimacy debates have prompted a myriad of empirical studies. Scholars have examined how diverse accountability mechanisms and stakeholder involvement constitute a considerable source of legitimacy (e.g., Braun & Busuioc, Citation2020; Busuioc & Jevnaker, Citation2022; Fink & Ruffing, Citation2020). Scholars have also studied the efforts of EU agencies to legitimize their outputs, processes, and behaviour to relevant audiences (e.g., Busuioc & Rimkutė, Citation2020a; Fjørtoft, Citation2020; Groenleer, Citation2014; Müller & Braun, Citation2021; Rimkutė, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Wood, Citation2018, Citation2021).

2 Quite regularly the ‘non-majoritarian’ and ‘derived/democratic’ legitimacy standards are regarded as competing, however, in practice they can coexist, therefore, we treat them as potentially complementary.

3 See the dataset and code by following the link: osf.io/qhtg9

4 All participants agreed with the study’s conditions detailed in our online consent form (Appendix II). Also, see Appendix III for further details on the ethics committee approval.

5 See the pre-registration by following the link: https://osf.io/8wyhs/?view_only=3289661eb5ab49b193d22f19bacb5b5f

References

- Abbott, K. W., Zangl, B., Snidal, D., & Genschel, P. eds. (2020). The Governor’s dilemma: Indirect governance beyond principals and agents. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198855057.001.0001.

- Bertelli, A. M., & Busuioc, M. (2020). Reputation-sourced authority and the prospect of unchecked bureaucratic power. Public Administration Review, n/a(n/a), https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13281

- Bode, I., & Huelss, H. (2023). Constructing expertise: The front- and back-door regulation of AI’s military applications in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1230–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174169

- Braun, C., & Busuioc, M. (2020). Stakeholder engagement as a conduit for regulatory legitimacy? Journal of European Public Policy, 27(11), 1599–1611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1817133

- Bunea, A., & Nørbech, I. (2022). Preserving the old or building the new? Reputation-building through strategic talk and engagement with stakeholder inputs by the European Commission. Journal of European Public Policy, 0(0), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2099450

- Busuioc, M., & Jevnaker, T. (2022). EU agencies’ stakeholder bodies: Vehicles of enhanced control, legitimacy or bias? Journal of European Public Policy, 29(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1821750

- Busuioc, M., & Rimkutė, D. (2020a). Meeting expectations in the EU regulatory state? Regulatory communications amid conflicting institutional demands. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(4), 547–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1603248

- Busuioc, M., & Rimkutė, D. (2020b). The promise of bureaucratic reputation approaches for the EU regulatory state. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(8), 1256–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1679227

- Dellmuth, L., Scholte, J. A., Tallberg, J., & Verhaegen, S. (2021). The Elite–Citizen gap in international organization legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000824

- Dunn Cavelty, M., & Smeets, M. (2023). Regulatory cybersecurity governance in the making: The formation of ENISA and its struggle for epistemic authority. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1330–1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2173274

- Eriksen, E. O., & Fossum, J. E. (2004). Europe in search of legitimacy: Strategies of legitimation assessed. International Political Science Review, 25(4), 435–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512104045089

- European Commission. (2022). Health security and infectious diseases. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/security/overview_en.

- European Medicines Agency. (2021). About us. Retrieved from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/what-we-do.

- European Medicines Agency. (2022). COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring. Retrieved from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-development-evaluation-approval-monitoring.

- Fink, S., & Ruffing, E. (2020). Stakeholder consultations as reputation-building: A comparison of ACER and the German Federal Network Agency. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(11), 1657–1676. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1817129

- Fjørtoft, T. N. (2020). More power, more control: The legitimizing role of expertise in Frontex after the refugee crisis. Regulation & Governance, n/a(n/a), https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12373

- Follesdal, A., & Hix, S. (2006). Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU: A response to Majone and Moravcsik. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(3), 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00650.x

- Groenleer, M. (2014). Agency autonomy actually: Managerial strategies, legitimacy, and the early development of the European union’s agencies for drug and food safety regulation. International Public Management Journal, 17(2), 255–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2014.905416

- Holst, C., & Molander, A. (2019). Epistemic democracy and the role of experts. Contemporary Political Theory, 18(4), 541–561. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-018-00299-4

- Kreuder-Sonnen, C. (2019). Emergency powers of international organizations: Between normalization and containment. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198832935.001.0001.

- Kruck & Weiss. (2023). The regulatory security state in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1205–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172061

- Levi-Faur, D. (2011). Regulatory networks and regulatory agencification: Towards a single European regulatory space. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(6), 810–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.593309

- Levi, M., Sacks, A., & Tyler, T. (2009). Conceptualizing Legitimacy, Measuring Legitimating Beliefs. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 354–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209338797

- Linz, J. J. (1998). Democracy’s time constraints. International Political Science Review, 19(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251298019001002

- Majone, G. (1994). The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics, 17(3), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389408425031

- Majone, G. (1997). The new European agencies: Regulation by information. Journal of European Public Policy, 4(2), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501769709696342

- Majone, G. (1998). Europe’s ‘Democratic Deficit’: The question of standards. European Law Journal, 4(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0386.00040

- Majone, G. (1999). The regulatory state and its legitimacy problems. West European Politics, 22(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389908425284

- Maor, M. (2007). A scientific standard and an agency’s legal independence: Which of these reputation protection mechanisms is less susceptible to political moves? Public Administration, 85(4), 961–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00676.x

- Martinsen, D. S., Mastenbroek, E., & Schrama, R. (2022). The power of ‘weak’ institutions: Assessing the EU’s emerging institutional architecture for improving the implementation and enforcement of joint policies. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(10), 1529–1545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2125046

- Mazepus, H., & Rimkutė, D. (2022). Delegation without legitimation? [Data set and code]. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/QHTG9 available at osf.io/qhtg9.

- Mazepus, H., & van Leeuwen, F. (2020). Fairness matters when responding to disasters: An experimental study of government legitimacy. Governance, 33(3), 621–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12440

- Müller, M., & Braun, C. (2021). Guiding or following the crowd? Strategic communication as reputational and regulatory strategy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, muab008), https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muab008

- Obendiek, A., & Seidl, S. (2023). The (False) promise of solutionism: Ideational business power and the construction of epistemic authority in digital security governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1305–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172060

- Rauh, C. (2022). Clear messages to the European public? The language of European Commission press releases 1985–2020. Journal of European Integration, 0(0), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2022.2134860

- Rimkutė, D. (2018). Organizational reputation and risk regulation: The effect of reputational threats on agency scientific outputs. Public Administration, 96(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12389

- Rimkutė, D. (2020a). Building organizational reputation in the European regulatory state: An analysis of EU agencies’ communications. Governance, 33(2), 385–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12438

- Rimkutė, D. (2020b). Strategic silence or regulatory talk? Regulatory agency responses to public allegations amidst the glyphosate controversy. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(11), 1636–1656. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1817130

- Rimkutė, D. (2021). European union agencies: Explaining EU agency behaviour, processes, and outputs. In D. Hodson, U. Puetter, S. Saurugger, & J. Petersen (Eds.), The Institutions of the European Union 5th ed. (pp. 203–223). Oxford University Press.

- Rimkutė, D. (2022). Expertise and regulatory agencies. In M. Maggetti, F. Di Mascio, & A. Natalini (Eds.), The Handbook on Regulatory Authorities (pp. 486–501). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Rittberger, B., & Wonka, A. (2011). Introduction: Agency governance in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(6), 780–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.593356

- Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and democratic? Oxford University Press. https://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/21979.

- Schmidt, V., & Wood, M. (2019). Conceptualizing throughput legitimacy: Procedural mechanisms of accountability, transparency, inclusiveness and openness in EU governance. Public Administration, 97(4), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12615

- Schrama, R. (2022). Expert network interaction in the European Medicines Agency. Regulation & Governance, https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12466

- Skogstad, G. (2003). Legitimacy and/or policy effectiveness?: Network governance and GMO regulation in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 10(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000085333

- Tallberg, J., & Zürn, M. (2019). The legitimacy and legitimation of international organizations: Introduction and framework. The Review of International Organizations, 14(4), 581–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9330-7

- Toshkov, D. (2022). What Accounts for the Variation in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Eastern, Southern and Western Europe? OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/ka2v3.

- Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), 375–400. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038

- Wonka, A., & Rittberger, B. (2010). Credibility, complexity and uncertainty: Explaining the institutional independence of 29 EU Agencies. West European Politics, 33(4), 730–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402381003794597

- Wood, M. (2018). Mapping EU agencies as political entrepreneurs. European Journal of Political Research, 57(2), 404–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12232

- Wood, M. (2021). Can independent regulatory agencies mend Europe’s democracy? The case of the European Medicines Agency’s public hearing on Valproate. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 13691481211054320, https://doi.org/10.1177/13691481211054319

- Zürn, M. (2018). A theory of global governance: Authority, legitimacy, and contestation. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198819974.001.0001.