ABSTRACT

Both proponents and critics of the regulatory state thesis view the creation of non-majoritarian institutions, such as independent regulatory agencies, as a process of ‘depoliticisation’. This article problematises this assumption by proposing an analytical framework for better understanding the link between politicisation, depoliticisation, and the delegation of powers to non-majoritarian institutions, based on a study of drug rationing policies in England and France. A greater delegation of decision-making powers to a regulator enables policy decisions that are likely to prove politically costly, but such decisions are also likely to attract greater counter-mobilisation, undermining policy stability over time. By contrast, in a less delegated setting, elected politicians can prevent unpopular policy choices from being taken, which contributes to policy continuity. The article further argues that, where decision-making powers are highly delegated, the regulator’s autonomy and the visibility of losses imposed by policy decisions condition the politicisation process. These findings suggest that, far from depoliticising policy problems, delegated policymaking insulated from politics can undermine itself by becoming a source of subsequent politicisation; they thus question the prevailing notion that delegation to non-majoritarian institutions contributes to policy stability.

Introduction

In the past few decades, independent regulatory agencies, independent central banks, and other delegated policymaking bodies have spread across capitalist economies (Gilardi, Citation2009; Jordana et al., Citation2011; Thatcher & Stone Sweet, Citation2002). Broadly labelled as ‘non-majoritarian’ institutions – government entities organisationally separate from the executive government, neither directly elected by the people nor managed by elected officialsFootnote1 – the implications of such bodies for democratic governance have been hotly debated. Their proponents contend that they contribute to policy stability and effectiveness (Majone, Citation1999). Their critics argue that their spread results in the erosion of democracy and shields politicians from responsibility and public scrutiny (Hay, Citation2007; Mair, Citation2013). Regardless of one’s view, however, it has become received wisdom that the creation of non-majoritarian institutions represents a shift towards ‘depoliticisation’, a process whereby a particular political issue becomes less the subject of the governmental and public arenas, thereby removing the potential for debate, choice, and action associated with politics.Footnote2

Yet, growing attention given to political struggles over regulatory decision-making calls this assumption into question. Recent scholarship has explored contestations against sectoral regulators (Koop & Lodge, Citation2020), central banks (McPhilemy & Moschella, Citation2019), and the European Union (EU) as a non-majoritarian institution (Zürn, Citation2019); and, more generally, the repoliticisation of supposedly depoliticised institutions (Fawcett et al., Citation2017; Zürn, Citation2022). Collectively, these observations highlight the need for an analytical framework with which to understand the conditions for, and mechanisms behind, the repoliticisation of the regulatory state.

This article proposes such a framework by highlighting its endogenous drivers, that is, the forces generated by the regulatory institutions themselves. Drawing on the historical institutionalist literature on institutional and policy development (Jacobs & Weaver, Citation2015; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010), I argue that policy change that is politicisation-driven, following the creation of independent regulators, depends on the degree of initial delegation; specifically, the extent to which the decision-making powers are transferred from the elected official to a regulator. A highly delegated setting, taking away the decision-making powers from politicians, makes it possible to produce policy outputs that are likely to prove politically costly. But these policy choices, once made, create a greater magnitude of counter-mobilisation in the public arena, undermining policy stability over time. By contrast, in a less delegated setting where elected politicians hold the decision-making powers in their hands, they can prevent unpopular policy choices from being taken. By blocking the opportunity to expand political conflicts, the actions of such politicians contribute to policy continuity.

I develop this argument through an analysis of drug rationing policies, or the restriction of funding of pharmaceutical products by health care systems. The case is illustrative of the politicisation of the regulatory state, attributable to both the strong functional imperative for non-majoritarian institutions and its deep political consequences. The functional demand for independent regulators has been at its greatest in this sector: technological advances and demographic change have presented governments with often contradictory pressures around funding drugs, including controlling costs, ensuring citizen access, and rewarding innovative industries. In response, since the 1990s many European countries have created regulatory agencies tasked with assessing the clinical and/or cost effectiveness of medical technologies.Footnote3 Such a reform was justified on the grounds that it would base rationing decisions more on evidence and technical expertise and would achieve a rational resource allocation.Footnote4 Yet, rationing, by its nature, is a political act, setting priorities on which treatment is funded, and which is not, generates losses among sections of society. A policy decision to exclude a drug from the public health care system imposes clearly identifiable losses on organised interests such as drug companies and patient groups; the decision could also be deemed controversial, drawing public attention. Policy makers who choose to impose the losses are thus likely to face mobilisation by those affected groups. Understanding the role of these two forces, the functional and the political, in policy trajectories has important implications for the development of the regulatory state. I compare trajectories of drug rationing policies, after the creation of independent regulators, in England and France. As I shall show below, contrary to what the delegation theory would expect, despite its highly delegated decision-making locus England followed a conflict-ridden path that undermines its policies, while the less politically insulated French setting exhibits greater policy continuity. Given these puzzling outcomes that contradict the existing theory, I use process tracing to elucidate an alternative mechanism that links delegation of decision-making powers with politicisation-induced policy change.

By examining political struggles following the creation of regulators, this article makes two main contributions. First, it identifies a novel mechanism that endogenously drives the politicisation of the regulatory state. While the recent literature has explored effects of politicisation on organisational or policy change (e.g., Koop & Lodge, Citation2020; Maor & Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Citation2013), I point to one of its origins, i.e., where (re)politicisation came from. Second, my analytical framework departs from the dominant, functional logic of the regulatory state and instead highlights its political logic. Consequently, my case study questions the prevailing notion that the delegation of powers to an independent regulator leads to policy stability (cf. Majone, Citation1997, Citation1999). On the contrary, it suggests that a greater degree of the delegation of decision-making powers to independent regulators – the very institutional design that is seen to enable a credible commitment and is therefore crucial for policy stability – can in practice provoke a greater political conflict that ultimately undermines policy stability.

Studying the post-reform political struggles: an analytical framework

The outcome this article examines is politicisation-induced policy change following the creation of regulatory agencies. Politicisation can be understood as the increasing awareness of, and mobilisation around, regulation by non-majoritarian institutions (de Wilde & Zürn, Citation2012; Koop & Lodge, Citation2020). Policy change is assessed by the introduction and use of rules that set the parameter of regulatory decisions. In the case of drug rationing policies, such rules imply regulatory criteria that define whether a drug should be funded by, or excluded from, public health care systems.

Independent regulators are commonly considered instrumental for policy stability (Cukierman et al., Citation1992; Majone, Citation1997, Citation1999; Miller & Whitford, Citation2016). Such stability is often hard to attain, because of electoral turnover and temporal shifts in politicians’ preferences (Rogoff, Citation1985). Delegating powers to independent regulators, it follows, enables politicians to credibly commit to long-term policy goals beneficial for society. In his seminal work on the regulatory state in Europe, Majone (Citation1999, p. 4; cf. Majone, Citation1997, pp. 153–154) argued that credible commitment is ‘the main reason today for delegating policymaking powers to [non-majoritarian] institutions’. Credible commitment makes it possible to attract private investment (Levy & Spiller, Citation1994) and to secure policy solutions beyond electoral cycles (Majone, Citation1997, Citation1999; Miller & Whitford, Citation2016). On this functional account, delegation of powers is hence expected to yield greater policy stability.

Yet, empirical records of post-reform policy trajectories contradict such expectations. Despite creating a highly insulated regulator, England experienced non-negligible fluctuation in its subsequent policies, where, despite the initial line of policies making substantial rationing decisions, later periods saw measures introduced to make certain types of new, expensive drugs available. By contrast, the French trajectory, while delegating less powers to the regulator than its English counterpart, exhibited greater policy continuity, where, despite the arrival of new drugs putting the health care system under pressure, few measures were introduced to change the occurrence of rationing decisions.

These gaps between theory and reality suggest that the successful enactment of a reform hardly guarantees policy continuity from then on (Patashnik, Citation2008). If a new regulator is successfully created, once in operation, regulatory policies will inevitably bring about significant distributive consequences; they are thus likely to provoke counter-mobilisation from those who bear the cost of regulation. The counter-mobilisation triggered by these losses can, in turn, pose a threat to the existing policies (Jacobs & Weaver, Citation2015). We thus cannot safely assume policy continuity after the regulator-creating reforms.

To better understand the post-reform political dynamics, I draw on an alternative, power-centred reading of institutions (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010; Moe, Citation2005). My key premise is that institutions are inherently conflictual and contain power struggles within them. A major source of change, on this account, lies in shifts in the relative power balance between the coalitions of actors supporting the existing policies and those opposing them. The focus of analysis from which to follow this is, therefore, on how features of institutions can expand or contain the coalition of counter-mobilisers. I place a particular emphasis on a feedback mechanism endogenous to existing policies; specifically, how policies amplify counter-mobilisation to a level that shifts the coalitional balance (Jacobs & Weaver, Citation2015; Weaver, Citation2010; cf. Pierson, Citation1993).

Delegation of decision-making powers has an important role in this endogenous process. I focus here on the extent to which decision-making powers in a given issue are transferred from elected politicians to regulators when creating a regulatory agency. Where decision-making powers are highly delegated, elected politicians have no say in regulatory decisions. Following its creation, it is the agency that makes decisions; its outputs, once decided, are irrevocable, elected officials cannot make changes to them. By contrast, where the degree of delegation of decision-making powers is low, elected officials hold decision-making powers even after the creation of an agency. The agency’s outputs can be overridden by an elected official vested with formal decision-making powers. In practice, low delegation may take the form of an ‘informal’ or ‘advisory’ status of a regulator’s output, a requirement of ministerial approval, or final decision-making powers resting with the minister. The varying levels of delegation of powers thus make a difference to elected politicians’ remaining powers, after the creation of a regulatory agency.Footnote5

The degree of delegation matters for the post-reform political struggles because it shapes the ability of the decision maker to impose losses on society. Elected politicians have a strong incentive to avoid the likely blame arising from significant policy losses (Hood, Citation2011; Weaver, Citation1986) . Delegation of powers constrains politicians’ strategic options around the likely imposition of loss that a controversial decision will yield. In particular, whether or not the option to block such a decision before it arises is available to elected politicians affects their blame-avoiding behaviours.Footnote6

If the varying degrees of delegation of decision-making powers shape the ability to make loss-imposing policy choices, the differing choices create the subsequent political struggles. Research on policy feedback has shown how past policies affect actors’ preferences and capacities (Pierson, Citation1993). Of particular relevance here is that policies often generate negative, self-undermining feedback effects that, over time, erode actors’ own political base. A loss-imposing regulation is prone to trigger strong negative feedback effects because the losses can be highly visible (cf. Jacobs & Weaver, Citation2015; Pierson, Citation1994). The visible, easily identifiable losses enable those who seek to challenge policies to draw the attention of the wider public. A broadened political base through such mobilisation will thus put policy makers under pressure. In short, the varying policy choices, anchored by delegation of powers, affect the opportunities available to the cost-bearers of regulation to expand their coalition via the public arena.

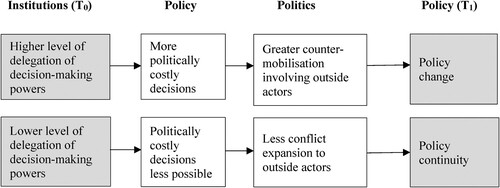

Building on the preceding discussion, summarises the main argument linking the delegation of decision-making powers and subsequent policy development. It presents (1) how different levels of delegation of decision-making powers affect policy choices; and (2) how policy choices, in turn, affect subsequent political conflicts and policy development.

First, delegation of powers has important implications for policy choices, especially when a regulator’s outputs are likely to impose significant policy losses. Where the locus of decisions is moved to the regulator, since the minister has no say on the regulators’ output, it is possible to produce policy choices that are otherwise politically too costly. Where, in contrast, the degree of delegation of decision-making powers is low, elected politicians, with decision-making powers in their hands, can choose to prevent a policy choice by overriding the regulator’s output if they consider the likely policy losses too politically significant.

Next, policy choices involving the imposition of loss affect, in turn, the subsequent political conflicts and policy development. In a highly delegated setting, the loss-imposing policy generates counter-mobilisation channelled through public and electoral arenas. Actors who seek to change rules exploit the visibility of the loss. Political campaigns to ‘raise awareness’ enable actors to build a broader base of mobilisation that is not limited to narrow ‘stakeholders’. The heightened level of public awareness may draw the attention of vote-seeking politicians who are otherwise not interested in the issue (cf. Baumgartner & Jones, Citation2010; Culpepper, Citation2010). These politicians may, then, join the coalition of actors advocating policy change. As the pressure rises, incumbent elected officials may also adjust their policy positions, for fear of being punished by voters. In sum, regulatory decisions in highly delegated settings are prone to generate negative, self-undermining feedback through the public and electoral arenas.

If, on the other hand, the decision-making locus is less delegated, the magnitude of this dynamic should be relatively limited. The regulator’s negative recommendations may still arouse a counter-mobilisation because of the potential loss it is likely to trigger. But since the minister, who has the final decision-making powers, is receptive to such a counter-mobilisation when the losses of proceeding make the choice too high, the regulatory outputs should be less likely to result in actual losses that counter-mobilisers can exploit to broaden their coalitional base in the public arena. As a result, political conflicts are channelled less through the public and legislative arenas and operate more in the existing decision-making arenas for drug funding.

This pathway to policy change through politicisation via the public arena does not deny other strategies actors can use for counter-mobilisation against regulatory decisions. Such strategies include seeking to forge an alliance with government actors, via informal lobbying of, and formal consultation by, regulatory agencies, ministries, and parliamentary committees. Yet, a key difference between actors’ strategies in a highly delegated setting and those in a less delegated setting is that, in addition to those strategies operating behind closed doors, the former can expand the conflict in the public arena by exploiting the visibility of the loss-imposition. As Schattschneider (Citation1975, p. 16) once noted, expanding social conflicts is a strategy deployed by the losing side in a conflict.

Under what conditions does delegation of decision-making powers trigger politicisation and policy instability? Each constitutive step of the mechanism in is expected to occur only under certain conditions. First, a regulator with decision-making powers can actually produce politically costly decisions only where it has unique preferences that are irreducible to those of elected officials and organised interests. It must also have capacities necessary to translate its preferences into policy outputs. In other words, a politically costly choice is more likely to take place when a regulator acts autonomously (cf. Carpenter, Citation2001; Maggetti, Citation2007). Contextual factors also matter for the link between policy choices and counter-mobilisation. A politically costly choice is more likely to trigger the expansion of conflict in the public arena, where the imposition of concentrated losses is made visible to the public. Such a concentration is likely to occur when the loss is imposed on a well-defined and tightly linked group in a society; and the imposition of loss becomes visible when it is felt through ‘focusing events’, or dramatic events that quickly capture public attention (Jacobs & Weaver, Citation2015). In these contexts, the group who bear the losses imposed can expand its coalition by mobilising a broad political base via the public arena.

Case selection, methods, and shared initial conditions

This article uses comparative case studies and process tracing to examine the role of delegation in post-reform policy development in England and France.Footnote7 Several similarities make the two countries excellent cases to compare. First, the two countries share several background conditions that have put them under pressure regarding drug funding. Both are developed democracies with similar demographic trends.Footnote8 Moreover, with the creation in 1995 of the European Medicines Evaluation Agency, the drug approval regulator at EU level, ‘innovative’ medicines became subject to the same, Europeanised approval process. These common characteristics allow me to hold both demographic changes and new medical technologies – two major sources of challenge for the health care state – largely constant. Second, despite the different public health care financing models (health service in England and health insurance in France), in both countries the power over drug coverage decisions rests with the state. Policy makers in both countries thus have held the responsibility – and the blame – for making a drug (un)available through the health care systems. Third, both countries’ constitutional structures are marked by a strong executive and a majoritarian electoral system that tends to generate fewer parties in government. Fourth, both countries are a home to a major pharmaceutical industry that is considered to be strategically important. Thus, both national and sectoral institutions in the two countries were endowed with similar structures of political pressure on incumbent policy makers facing drug funding decisions.

Between the late 1990s and early 2000s both countries set up regulatory agencies that assess the clinical and/or cost effectiveness of drugs – an event that is in line with the broader trend towards the growth of the regulatory state in Europe. The UK is generally seen both as a frontrunner and as a paradigmatic case of the regulatory state (Moran, Citation2003). In France, the creation of the independent regulatory agency in this area was considered to be a convergence towards the British regulatory state model (Hassenteufel & Palier, Citation2007). Policy makers in France have, in fact, often made an explicit reference to the English experience, both as a model and as a source that lessons can be drawn from.

Yet, the ostensible convergence to the regulatory state model conceals important differences in the decision-making locus over drug funding. In England, with the creation of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in 1999, decision-making powers over drug funding were taken away from elected politicians. Thus, once NICE issued its Technology Appraisal guidance – a recommendation about whether a drug should be funded by the National Health Service (NHS) – it became the final decision for the NHS. This institutional feature was reinforced during the early years of operation; since 2002 Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) and Health Authorities (the local purchasing bodies of the NHS) have had the statutory obligation to fund technologies recommended by NICE’s Technology Appraisals.Footnote9 NICE’s guidance was published directly throughout the PCTs, and once it was issued there were few powers granted to ministers to overturn it.

By contrast, drug funding decisions in France were less delegated, with the final decision-making powers remaining in the hands of elected politicians. Created in 2004, the independent regulatory agency the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) enjoyed considerable formal independence from the health minister in terms of its statutory base and appointment rules. However, in terms of decision-making rules, both before and after the creation of HAS, it was the health minister who made the final decision on whether a drug would be included in the reimbursement list. The Transparency Committee, an expert committee inside HAS, issued an Avis (opinion), which included evaluation about a drug’s clinical benefit; the minister, then, made the final reimbursement decision based on these opinions.Footnote10 Thus, while both countries created regulators, there were important differences in the remaining powers of the health ministers to affect drug funding decisions.

Some readers may wonder whether the observed variation in post-reform dynamics could simply reflect prior differences in the healthcare systems and be unrelated to the delegation reform. They might think, for example, that with a traditionally smaller pharmaceutical spending per capita, and with a national health service, which, unlike a social health insurance, does not allow for partial reimbursement, drug rationing could be a policy problem in England but not in France.Footnote11 A cursory look at the prior policy history, however, reveals that, in both countries, controversies over rationing had been prominent in debates leading up to the creation of the agencies. In England, following the 1990 introduction of the NHS ‘internal market’ by the Conservative government, controversies grew, during the course of the 1990s, over the refusal of treatment by local health authorities and the resulting geographical unevenness in access to treatment. One of the main rationales that the subsequent Labour government gave for the creation of a regulator was, hence, to tackle this so-called ‘post-code lottery’ through uniform guidance applied across the nation. In France, since the 1970s, both left- and right-wing governments have used changes in the reimbursement status of drugs, and sometimes total de-reimbursement, i.e., removal of drugs from the reimbursement list, as a tool for cost control, policies that were much contested. Consequently, the government framed the agenda for an independent regulator as a response to a proposal by the Mutualité, the federated body of the mutual insurers and a major cost-bearer of the reduction of the reimbursement rate.Footnote12 In both countries, the creation of agencies was thus expected to increase the power of experts in a hotly contested area.

I now turn to post-reform policy development. This article is primarily a theory-building exercise: I start with an empirical contradiction of the existing, functional theory of delegation which expects that delegation leads to depoliticisation and policy stability; then, using a comparative case study and process tracing, I develop an alternative mechanism linking the degree of delegation with subsequent policy trajectories.Footnote13 The analyses start at the inception of agencies in the respective countries and end at around 2016. The article draws on a variety of materials, including: government documents and policy reports, parliamentary minutes and reports, statements made by various societal actors; newspapers, trade journals, and other secondary materials; and semi-structured interviews with actors in the policy process, including government and regulator officials, the pharmaceutical industry, and academic experts.

England: high delegation, public controversies, and a partial policy change

The post-reform trajectory in England was characterised by high-profile conflict and prominent political battles between the regulator and actors aligned with drug manufacturers, channelled through public and electoral arenas. The political conflicts and public controversies, in turn, led to a partial policy change that favoured certain types of new, expensive drugs.

With the locus of decision making insulated from elected politicians, English policy makers produced policy choices that would have been otherwise politically costly. NICE restricted a considerable number of the technologies it appraised. Between 2000 and 2015, approximately 40 per cent of the drugs (232 of 571 technologies) NICE appraised resulted in some form of restriction compared to its approved usage.Footnote14 The negative decisions often provoked contestations;Footnote15 drug manufacturers and patient groups criticised NICE as the ‘fourth hurdle’ to drug access. Despite the contestations, however, little evidence indicates that the Health Secretary attempted to ignore or overturn NICE’s guidance.Footnote16 By leaving ministers little room for manoeuvre the highly delegated locus of decision making enabled the production of otherwise politically costly choices.

Yet, such tough policy choices, once made, were subject to intense counter-mobilisation. Drug companies actively mobilised themselves, seeking to change rules via different routes with varying success. Some counter-mobilisation involved lobbying policy makers via business and government fora. These included the Pharmaceutical Competitiveness Task Force, a forum created in response to the lobbying by the pharmaceutical industry of the Prime Minister Tony Blair, following NICE’s negative guidance, and the Bioscience Innovation & Growth Team, a group launched in 2003 by the Department of Trade and Industry, in partnership with the BioIndustry Association. While these fora were vocal in challenging NICE’s practices throughout the 2000s, they resulted in few changes in NICE’s policy orientations.

If counter-mobilisation through these business-friendly arenas yielded little policy change, however, counter-mobilisation did result in policy change when it broadened its political base in the public and electoral arenas; the availability of cancer drugs exemplifies such dynamics. Cancer is among the most politically salient disease areas, with powerful organised interests; large charities such as Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support are among the best-resourced organisations in the UK non-profit sector.Footnote17 In addition to drug companies, these charities and patient groups were mobilised to participate in publicity campaigns, which helped to raise public awareness of the issue. Media played an important role in the process of the mobilisation by extensively covering NICE’s negative decisions on cancer drugs and patient groups’ reactions against them.Footnote18

Throughout the mobilisation against negative decisions, the cost-effectiveness criteria NICE used in its guidance was a major focal point. NICE uses quality-adjusted life years (QALY) to estimate how much a given medical intervention adds to a person’s length and quality of life. Cost per-QALY, or the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), then indicates the cost-effectiveness of the drug. During its early years of operation, it emerged that NICE tended to use an ICER of £20,000–£30,000 per QALY as a threshold to judge whether a drug was considered an appropriate use of NHS resources.Footnote19 As NICE tended to reject a drug with an ICER higher than the cost-effectiveness threshold, the threshold became the subject of intense discussion.

The debate over NICE’s cost-effectiveness threshold translated into greater political pressure through a controversy over the NHS ‘top-up’ payments. In the NHS, based on its founding principle of ‘free at the point of delivery, regardless of the ability to pay’, a patient was prohibited from paying privately for a part of treatment on top of free treatments with the NHS, i.e., making ‘top-up’ payments (House of Commons Health Committee Citation2009, p. 14). The prohibition, however, received growing criticism among patient groups and physicians, who pressed for reform in order to obtain drugs that NICE had not yet appraised or had rejected. Public pressure increased in 2008, following media coverage of the death of a bowel cancer patient, who had been refused further NHS treatment because she privately purchased a drug rejected by NICE. Both the Department of Health and the Health Secretary Alan Johnson initially denied the possibility of reform, but, facing mounting pressure, Johnson soon changed position and asked National Cancer Director Mike Richards for a review of top-up payments.Footnote20 The resulting report recommended measures to improve the availability of drugs for patients nearing the end of their lives. NICE tended to judge such drugs as not cost-effective, but the review advocated a ‘greater flexibility’ based on a ‘common perception’ that society places special value on supporting end-of-life patients (Richards Citation2008, p. 42). In response, NICE introduced the End of Life (EoL) criteria; applied to life-prolonging drugs for a small patient population with a short life expectancy, the criteria, if they were met, would allow NICE to recommend treatments that exceed the threshold of £20,000–£30,000 per QALY (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Citation2009). The distributive implications of the criteria were hardly lacking in controversy: in the following year, the House of Commons Health Committee inquiry concluded that the EoL criteria were ‘both inequitable and an inefficient use of resources. By spending more on end-of-life treatments for limited health gain, the NHS will spend less on other more cost-effective treatments’ (House of Commons Health Committee Citation2009, para 119).

The heightened public controversies over the availability of cancer drugs further shaped politicians’ strategies for the 2010 General Election. The Conservative leader David Cameron and the shadow Health Secretary Andrew Lansley pledged to set up a specialised fund within the NHS, which would cover the cost of cancer drugs rejected by NICE. Following the Conservatives’ electoral victory and the establishment of the Coalition Government, the government announced that a £50 million ‘emergency fund’ would be injected before the launch of the Cancer Drugs Fund in the following year. Starting as a £200 million fund, the Fund’s budget was subsequently expanded to £280 million a year in 2014 and £340 million in 2015; by March 2015 it had spent £968 million (National Audit Office Citation2015, 7ff). The Fund effectively overrode the NICE guidance and – since it came from a ring-fenced budget within the NHS rather than an additional money – prioritised cancer drugs over other treatments and services.

Thus, the policy trajectory in England involved political battles channelled by the public and electoral arenas, which led to a partial policy change. The highly delegated decision-making locus made NICE’s outputs the final policy decisions for the NHS. Yet, over time, as NICE kept producing negative policy decisions, they generated counter-mobilisation. Drug companies and patient groups broadened their base of counter-mobilisation, calling on support from the public and politicians, by drawing public attention to the losses imposed by the policy decisions. The rise in public awareness and pressures on the incumbent government resulted in measures to improve availability of the cancer drugs that NICE would have judged not cost-effective, but at the expense of other treatments in the NHS.

France: low delegation, conflict containment, and policy continuity

In France, the post-reform period was characterised by the prevention of controversial decisions and policy continuity. With decision-making powers in their own hands, health ministers prevented unpopular policy decisions from taking place. The resulting absence of opportunities to expand coalitions contributed to policy continuity.

De-reimbursement of drugs with insufficient clinical benefit exemplifies the consequences of low delegation for policy choices. The Transparency Committee’s evaluation in 1999 of all the reimbursable drugs concluded that of 4,490 reimbursable drugs, 835 (18.3 per cent) were judged to be insufficient in clinical benefit.Footnote21 However, contrary to an initial announcement by the Socialist government and the health minister, Martine Aubry, de-reimbursing these products proved difficult. In addition to pressure from the domestic pharmaceutical industry – especially small and medium-sized firms, which would be affected the most – the industry minister was opposed, emphasising the impact on employment, while some medical professional associations also resisted.Footnote22 In the end, the Socialist health ministers, including Aubry and her successor Élisabeth Guigou, decided not to resort to total de-reimbursement, and instead opted to reduce the reimbursement rate for a certain category of products and for price reduction. This dynamic did not fundamentally change after the Transparency Committee was transferred to the newly created HAS in 2004. When HAS recommended de-reimbursement of 145 drugs with insufficient clinical benefit in 2006, the Gaullist health minister Xavier Bertrand refused to follow the HAS opinion, noting that his role was ‘to take into account the social reality’, as opposed to HAS’s ‘scientific assessment’.Footnote23 Successive ministers remained reluctant to implement de-reimbursement: the reimbursement rate for 150 products with low or insufficient clinical benefit was reduced from 35 to 15 per cent to avoid total de-reimbursement.Footnote24 In sum, both before and after the creation of an independent agency, elected officials prevented an unpopular policy choice, such as total de-reimbursement.

Ministers’ avoidance of unpopular choices operated not only at the level of policy choices over individual drugs but also at the level of rules defining those policy choices; we can see such a dynamic in the politics of changing reimbursement rules. It was relatively rare for the HAS Transparency Committee to give a negative opinion on drugs; 80–85 per cent of the drugs it examined each year received the rating ‘substantial’ actual benefit, usually reimbursed at 65 per cent. As the pressure to rationalise spending continued, however, from the mid-2000s, debate grew over HAS’s evaluation criteria. Often explicitly referring to NICE, its focal point was whether France should incorporate economic evaluation to achieve greater prioritisation in care. In addition to the Court of Audit, a long-term critic of the lack of economic evaluation, obligatory and complementary insurers and bureaucrats in the Ministry of Health supported the incorporation of economic evaluation, a call that was echoed by Haut Conseil pour l’Avenir de l’Assurance Maladie, a government-led agenda-setting forum.Footnote25 The Social Security Financing Law (LFSS) for 2008 thus gave HAS a mission to produce ‘medico-economic recommendations and opinions on the most efficient strategies for treatment, prescription or care management’.Footnote26 HAS set up the Commission Evaluation Economique et de Santé Publique (CEESP), which, in subsequent years, actively advocated the use of economic evaluation.

The debate over reimbursement criteria gained further momentum following a drug scandal. It was revealed that Mediator, a diabetes drug produced by the second-largest French manufacturer Servier, and one of the drugs the Transparency Committee judged insufficient in clinical benefit, was alleged to have caused from 500 to 2,000 deaths since 1976, before it was withdrawn in 2009. Following the scandal, in 2011 Health Minister Bertrand declared an overhaul of pharmaceutical regulation. This time, in addition to HAS and others advocating changes in the pre-scandal period, the Inspection Générale des Affaires Sociales, the grand corps investigating the scandal, proposed creating ‘NICE à la française’Footnote27, replacing the reimbursement criteria with a new version that integrated economic evaluation. The minister would still retain decision-making powers but would have to explain to the public the reasoning behind not following the evaluation.Footnote28 Such a far-reaching reform, however, did not take place; in the following year, a ministerial order gave CEESP’s economic evaluation some limited roles in pricing but none in reimbursement. Despite the favourable conditions for those advocating policy change – bureaucrats seeking to achieve policy innovation, a major scandal that drew public attention, and a minister who was eager to introduce a high-profile reform –change in reimbursement rules did not occur.

Why did the proposal fail to materialise? A major hurdle faced by actors seeking to change the rules was the ministers’ reluctance to take up a reform that might make a more unpopular policy possible. Throughout the policy debate, ministers distanced themselves from the use of economic evaluation in the reimbursement decision. For instance, during the National Assembly debate leading up to the 2008 LFSS that expanded HAS’s missions to medico-economic evaluation, the Gaullist health minister, Roselyne Bachelot, noted that ‘I am against integrating the concept of quality-adjusting life-years into the indicators of medico-economic efficiency, like NICE,’ because ‘it does not match the culture that HAS draws inspiration from’.Footnote29 The minister’s reluctance did not change after the Mediator scandal. In 2012, when HAS proposed replacing its evaluation criteria with a new version that would provide fuller comparative assessment, the Socialist minister was not in favour; again referring to the example of NICE, she considered a proposal such as this that might limit access to medicines would be ‘politically unacceptable’ in France.Footnote30 In subsequent years, the HAS Board Chair made multiple attempts to put into practice the new evaluation method; the continuous arrival of expensive drugs put health care systems under even greater pressure; and a 2015 report by the director of the National Health Insurance Fund (Caisse nationale de l’assurance maladie) recommended replacing the current criteria with a comparative evaluation similar to the HAS proposal (Polton Citation2015). Yet, during its tenure, the Socialist government never took up the proposals. With the decision-making powers in their hands, ministers were not keen on enacting a change in rules that could lead to more controversial decisions.

Thus, in France, a less delegated locus of decision making prevented unpopular policy choices from being taken. We have seen two different pathways of low delegation affecting ministers’ behaviours. First, low delegation allowed ministers to avoid de-reimbursing the drugs that the Transparency Committee judged as insufficient in clinical benefit. Another effect of the low delegation concerned ministers’ response to policy debate over changing drug funding rules. If the Mediator scandal helped those who advocated changes in the rules to put forward their agendas, the low delegation, whereby the final decision-making powers lay with the minister, meant that ministers had a strong incentive not to create political controversies surrounding HAS’s evaluation and reimbursement decisions. Any changes in criteria that would increase the chances of unpopular choices thus entailed the resistance of ministers.

Conclusion

Despite the common assumption that the spread of non-majoritarian institutions indicates a depoliticisation process, regulation by non-majoritarian institutions has increasingly become the subject of open contestations. This article has presented an analytical framework with which to understand political struggles after the creation of independent regulators, with a focus on their endogenous drivers and based on a study of drug rationing policies in England and France. In contrast to the existing literature emphasising the functional logic behind the regulatory state, here I have explored an alternative, political logic that stresses the role of the emerging losses that regulation imposes in operation. In doing so, the article has demonstrated how a greater delegation of powers to a regulator in England led to a more conflictual, unstable path than its French counterpart where the locus of the decision was less delegated. I here highlight two further findings.

First, delegation of powers to independent regulators had consequences for the subsequent political dynamics because it shaped whether politicians were able to avoid politically costly policy choices. Where the politicians had decision-making powers, such as in France, they were able to block unpopular policy choices, such as de-reimbursement and proposals for changing reimbursement rules. Such an option was not available for the English ministers. With few decision-making powers left in their hands, elected politicians did not overturn NICE’s loss-imposing decisions. The losses, in turn, provoked the counter-mobilisation of affected actors, resulting in policy change favouring cancer drugs where the counter-mobilisation was the greatest.

Second, my case study has highlighted the role of different arenas in policy change. Facing a loss-imposing regulatory decision, whether or not policy makers were able to contain conflicts in the existing decision-making locus had implications for coalition expansion via the public arena. In England, even if actors did not successfully challenge policy through lobbying via business and government fora, controversies in the public arena played an important role in policy change by expanding the base for mobilisation. The dynamic showed a stark contrast to France, where ministers were able to accommodate societal interests using their powers in the regulatory arena. The key role of the public arena in this mobilisation process means that in the highly delegated regulatory state the source of endogenous change is more likely to come from outside the existing locus of regulatory decisions – a finding that is somewhat missing from the recent literature’s focus on ‘hidden’ change by elites manipulating institutions from within (e.g., Hacker et al., Citation2015).

It is also worth noting two limitations of the study. First, while this analytical framework focuses on the effects of different levels of delegation of decision-making powers, their origins are outside its scope. Second, the discussion on endogenous change here is primarily about policy challengers. But whether challengers’ mobilisation results in policy change can depend also on its defenders. Continuity and change, then, may be a product of the relative balance between negative and positive feedback effects (Weaver, Citation2010). To gain a complete picture of these dynamics, future study could examine how independent regulators, by channelling positive feedback from existing policies and institutions, respond to counter-mobilisation.

Finally, returning to the opening question of the regulatory state and politicisation, contrary to the dominant view that delegating powers to non-majoritarian institutions is crucial for policy stability, my findings suggest that it can actually result in policy instability by becoming the subject of politicisation itself. Of course, we need to be cautious about the generalisability of the findings from a two-country, single-sector case study. Nevertheless, the mechanism of the politicisation of the regulatory state identified here should be applicable to the policy sectors where regulation imposes losses on societal groups to achieve policy goals. Two further key factors that condition the mechanism include: (a) a regulator's autonomy, which makes it possible to make politically costly decisions; and (b) the visibility of the losses, which triggers counter-mobilisation. Where decision-making powers are highly delegated, these conditions fuel a politicisation process, eroding the base for policy stability that the regulatory state is claimed to achieve.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Philippe Bezes, Jared Finnegan, Corinna Funke, Philipp Genschel, Colin Hay, Ellen Immergut, Christel Koop, Bilyana Petrova, Mark Thatcher, Matia Vannoni, David Woodruff, conference or seminar participants at the 2022 International Conference for Europeanists, the 2021 World Congress of Political Science, the 2021 ECPR Standing Group on Regulatory Governance Biennial Conference, the 2019 Public Policy Research Network Graduate Workshop, the European University Institute, and the London School of Economics, and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Takuya Onoda

Takuya Onoda is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow in the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics at Sciences Po, Paris, France.

Notes

1 This definition is modified from Thatcher and Stone Sweet (Citation2002, p. 2).

2 This understanding of depoliticisation is based on Fawcett et al. (Citation2017, p. 6); Hay (Citation2007, Chapter 2).

3 16 out of the 28 (12 out of the 15 pre-2004) EU member states had established an agency by 2011 (Löblová, Citation2016, p. 257).

4 These rationales are partly informed by international policy trends such as health technology assessment, which involves a systematic evaluation of impacts of health care technologies from medical, economic, ethical, and social perspectives (Velasco-Garrido et al., Citation2008, pp. 31ff).

5 It is worth noting that delegation of decision-making powers, which this article focuses on, is analytically distinct from a regulator's independence, a much-discussed concept in the literature; the latter refers to a regulator’s ability to make policy outputs without political interference. A regulator that is independent may or may not possess decision-making powers for a given issue. For the distinction between the two, see Hanretty and Koop (Citation2012).

6 This preventive action is consistent with what recent scholars have called the ‘anticipated’ form of blame-avoidance behaviour, as distinct from the ‘reactive’ one (Sulitzeanu-Kenan & Hood, Citation2005; Hinterleitner & Sager, Citation2017).

7 Due to the jurisdiction of the National Health Service this study focuses on England and not the UK.

8 The share of persons >65yo in the total population (2016): 17.9 per cent (UK), 18.8 per cent (FR), EU-28 average = 19.2 per cent; Life expectancy at birth for total population (2015): 81.0 (UK), 82.4 (FR), EU-28 average = 80.9. Source: Eurostat (online data code: demo_pjanind, demo_gind).

9 In 2012, the Primary Care Trusts were replaced by the Clinical Commissioning Group and the Health Authorities were abolished. NICE was later renamed as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in2005 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in2013, as its remit expanded.

10 In its opinion on drugs, the Transparency Committee assesses the drug’s absolute clinical benefit (Service médical rendu or SMR), which informed the reimbursement decision. The SMR consisted of five ratings and was connected with the reimbursement rate. The drugs given ‘major’ (majeur) or ‘substantial’ (important) SMR ratings would normally be covered for 65 per cent of the cost, while the drugs with ‘moderate’ (modéré) and ‘low’ (faible) SMR would be covered for 35 per cent, and drugs with ‘insufficient’ (insuffisant) SMR would not be reimbursed.

11 The 2015 retail pharmaceutical expenditure per capita (including both prescription and over-the-counter medicines): $497 (UK), $637 (FR) (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)-31 average = $553 PPP). Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017. https://doi.org/10.1787/888933605388.

12 Le Figaro 16 June 2003; Le Monde 16 June 2003.

13 For an inductive use of process tracing, George and Bennett (Citation2005, Chapter 10); Falleti (Citation2016); Beach and Pedersen (Citation2019, Chapter 9).

14 This is based on the total number of the technologies falling into one of the following categories of NICE’s guidance: ‘Not recommended’, ‘Only in Research’, ‘Optimised’, or ‘Terminated’. The last category means the appraisal was terminated before its completion as the manufacturer did not submit evidence. The categories of decision are based on NICE’s own descriptions. The full list of guidance is available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-technology-appraisal-guidance/data/appraisal-recommendations.

15 Among the 401 technologies appraised from 2000 to 2011, appeals were submitted in 86 cases. Source: The author’s elaboration based on the guidance mentioned above.

16 Cf. Interviews with civil servants, 18 April 2018; 18 March 2021; Interview with a NICE official, 12 July 2018.

17 As of writing, both are within the top 30 charities in total income. Source: The Charity Commission. http://apps.charitycommission.gov.uk/Showcharity/RegisterOfCharities/SectorData/Top10Charities.aspx

18 Media extensively covered NICE’s decisions on cancer drugs. Of 800 articles mentioning NICE in The Times and The Guardian, two national broadsheet papers considered centre-right and centre-left respectively, in the period 2005–2009, 315 articles mentioned NICE and cancer, amounting to 39 per cent of the total coverage on NICE. (In the peak year 2006, it reached 48 per cent.) This was far greater than the number of articles mentioning NICE and other disease areas in the same period, such as Alzheimer’s disease (97 articles) and multiple sclerosis (14 articles). The author’s elaboration based on LexisNexis.

19 Rawlins and Culyer (Citation2004, p. 224); the House of Commons Health Committee (Citation2008, pp. 58–59).

20 Hansard 17 June 2008. Columns 787–790. The Independent 18 June 2008.

21 Le Monde 21 July 2001; 2 June 2001; Le Figaro 8 June 2001. The figures indicated here are the final results of re-evaluation, which was completed in 2001. The drugs with insufficient SMR mainly consist of vasodilators, magnesium-based products, and bronchial fluidifiers.

22 Les Echos, 11 July 2000. Personal communication with a health policy scholar, 30 September 2016. Interview with a civil servant, 10 November 2016.

23 Les Echos, 26 October 2006. Cf. Les Echos, 20 October 2006.

24 Le Monde, 17 April 2010.

25 See, respectively, Le Cour des Comptes (Citation2004, p. 315); Les Echos 21 March 2005; Hermange and Payet (Citation2006, p. 279); Benoît (Citation2020, p. 135); HCAAM (Citation2006, p. 18; Citation2007, p. 76).

27 Bensadon et al. (Citation2011, pp. 88–89). Italics for NICE in the original document.

28 Ibid., p. 88.

29 L’Assemblée nationale, Compte rendu analytique officiel. Séance du jeudi 25 Octobre 2007, 3ème séance. http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cra/2007-2008/026.asp

30 Interviews with former members of HAS, 28 June 2021; 12 March 2021; 29 January 2021.

References

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (2010). Agendas and instability in American politics (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Beach, D., & Pedersen, R. B. (2019). Process-tracing methods: Foundations and guidelines. University of Michigan Press.

- Benoît, C. (2020). Réguler l’accès aux médicaments. Presses Universitaires de Grenoble.

- Bensadon, A.-C., Marie, E., & Morelle, A. (2011). Rapport sur la pharmacovigilance et gouvernance de la chaîne du médicament (RM2011–103P). Inspection Générale des Affaires Sociales.

- Carpenter, D. P. (2001). The forging of bureaucratic autonomy: Reputations, networks, and policy innovation in executive agencies, 1862–1928. Princeton University Press.

- Cour des Comptes. (2004). La Sécurité Sociale.

- Cukierman, A., Web, S. B., & Neyapti, B. (1992). Measuring the independence of central banks and its effect on policy outcomes. The World Bank Economic Review, 6(3), 353–398. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/6.3.353

- Culpepper, P. D. (2010). Quiet politics and business power: Corporate control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- de Wilde, P., & Zürn, M. (2012). Can the politicization of European integration be reversed? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 50(s1), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02232.x

- Falleti, T. G. (2016). Process tracing of extensive and intensive processes. New Political Economy, 21(5), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2015.1135550

- Fawcett, P., Flinders, M. V., Hay, C., & Wood, M. (2017). Anti-politics, depoliticization, and governance. Oxford University Press.

- George, A. L., & Bennett, A. (2005). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. MIT Press.

- Gilardi, F. (2009). Delegation in the regulatory state: Independent regulatory agencies in Western Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hacker, J. S., Pierson, P., & Thelen, K. (2015). Drift and conversion: Hidden faces of institutional change. In J. Mahoney, & K. Thelen (Eds.), Advances in comparative-historical analysis (pp. 180–208). Cambridge University Press.

- Hanretty, C., & Koop, C. (2012). Measuring the formal independence of regulatory agencies. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(2), 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.607357

- Hassenteufel, P., & Palier, B. (2007). Towards neo-Bismarckian health care states? Comparing health insurance reforms in Bismarckian welfare systems. Social Policy & Administration, 41(6), 574–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00573.x

- Haut Conseil pour l’Avenir de l’Assurance Maladie (HCAAM). (2006). Avis sur le médicament.

- Haut Conseil pour l’Avenir de l’Assurance Maladie (HCAAM). (2007). Rapport du Haut conseil pour l’avenir de l’assurance maladie.

- Hay, C. (2007). Why we hate politics. Polity.

- Hermange, M.-T., & Payet, A.-M. (2006). Rapport d’information: Les conditions de mise sur le marché et de suivi des médicaments (n° 382). Sénat.

- Hinterleitner, M., & Sager, F. (2017). Anticipatory and reactive forms of blame avoidance: Of foxes and lions. European Political Science Review, 9(4), 587–606. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773916000126

- Hood, C. (2011). The blame game. Princeton University Press.

- House of Commons Health Committee. (2009). Top–up fees (Fourth Report of Session 2008–09. HC 194-I).

- House of Commons Health Committee. (2008). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (First Report of Session 2007–08. HC 27-l)

- Jacobs, A. M., & Weaver, R. K. (2015). When policies undo themselves: Self-undermining feedback as a source of policy change. Governance, 28(4), 441–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12101

- Jordana, J., Levi-Faur, D., & Fernández-i-Marín, X. (2011). The global diffusion of regulatory agencies: Channels of transfer and stages of diffusion. Comparative Political Studies, 44(10), 1343–1369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011407466

- Koop, C., & Lodge, M. (2020). British economic regulators in an age of politicisation: From the responsible to the responsive regulatory state? Journal of European Public Policy, 27(11), 1612–1635. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1817127

- Levy, B., & Spiller, P. T. (1994). The institutional foundations of regulatory commitment: A comparative analysis of telecommunications regulation. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 10(2), 201–246. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592705050176

- Löblová, O. (2016). Three worlds of health technology assessment: Explaining patterns of diffusion of HTA agencies in Europe. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 11(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133115000444

- Maggetti, M. (2007). De facto independence after delegation: A fuzzy-set analysis. Regulation & Governance, 1(4), 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2007.00023.x

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2010). A theory of gradual institutional change. In J. Mahoney & K. Thelen (Eds.), Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power (pp. 1–37). Cambridge University Press.

- Mair, P. (2013). Ruling the void: The hollowing of Western democracy. Verso Books.

- Majone, G. (1997). From the positive to the regulatory state: Causes and consequences of changes in the mode of governance. Journal of Public Policy, 17(02), 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00003524

- Majone, G. (1999). The regulatory state and its legitimacy problems. West European Politics, 22(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389908425284

- Maor, M., & Sulitzeanu-Kenan, R. (2013). The effect of salient reputational threats on the pace of FDA enforcement. Governance, 26(1), 31–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2012.01601.x

- McPhilemy, S., & Moschella, M. (2019). Central banks under stress: Reputation, accountability and regulatory coherence. Public Administration, 97(3), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12606

- Miller, G. J., & Whitford, A. B. (2016). Above politics: Bureaucratic discretion and credible commitment. Cambridge University Press.

- Moe, T. M. (2005). Power and political institutions. Perspectives on Politics, 3(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592705050176

- Moran, M. (2003). The British regulatory state: High modernism and hyper-innovation. Oxford University Press.

- National Audit Office. (2015). Investigation into the Cancer Drugs Fund: Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General (HC 442 Session 2015-16).

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2009). Appraising life-extending, end of life treatments. Revised in July 2009.

- Patashnik, E. M. (2008). Reforms at risk: What happens after major policy changes are enacted. Princeton University Press.

- Pierson, P. (1993). When effect becomes cause: Policy feedback and political change. World Politics, 45(4), 595–628. https://doi.org/10.2307/2950710

- Pierson, P. (1994). Dismantling the welfare state? Reagan, Thatcher and the politics of retrenchment. Cambridge University Press.

- Polton, D. (2015). Rapport sur la réforme des modalités d’évaluation des médicaments. Ministère des Affaires sociales, de la Santé et des Droits des femmes.

- Rawlins, M. D., & Culyer, A. J. (2004). National Institute for Clinical Excellence and its value judgments. BMJ, 329(7459), 224–227. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7459.224

- Richards, M. (2008). Improving access to medicines for NHS patients. Department of Health.

- Rogoff, K. (1985). The optimal degree of commitment to an intermediate monetary target. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 100(4), 1169–1189. https://doi.org/10.2307/1885679

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1975). The semi-sovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Sulitzeanu-Kenan, R., & Hood, C. (2005). Blame avoidance with adjectives? Motivation, opportunity, activity and outcome. ECPR joint sessions, blame avoidance and blame management workshop, Granada, Spain.

- Thatcher, M., & Stone Sweet, A. (2002). Theory and practice of delegation to non-majoritarian institutions. West European Politics, 25(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/713601583

- Velasco-Garrido, M., Kristensen, F. B., Busse, R., & Nielsen, C. P. (2008). Health technology assessment and health policy-making in Europe: Current status, challenges and potential. WHO Regional Office Europe.

- Weaver, R. K. (1986). The politics of blame avoidance. Journal of Public Policy, 6(04), 371–398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00004219

- Weaver, K. (2010). Paths and forks or chutes and ladders?: Negative feedbacks and policy regime change. Journal of Public Policy, 30(2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X10000061

- Zürn, M. (2019). Politicization compared: At national, European, and global levels. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 977–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619188

- Zürn, M. (2022). How non-majoritarian institutions make silent majorities vocal: A political explanation of authoritarian populism. Perspectives on Politics, 20(3), 788–807. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721001043