ABSTRACT

While all European democracies have been subject to the ‘stress test’ of the global rise of illiberal populism, institutional erosion has occurred mainly in the East. Several qualitative analyses have claimed that the weakness of liberalism explains democratic vulnerability in the region. Seeking inspiration and quantitative data, we turn to the research field of global support for democracy, which has always started from the assumption that it is through cultural change rather than institutional reform that democracy takes root. By melding empirical strategies from this field with insights from democratic theory, we present a new and more exacting measure of cultural liberalism. We extract individual-level data from the European Social Survey to measure the effect of the ‘Proportion of Cultural Liberals’ (PCL) within national cohorts on levels of (de)democratization between and within East and West Europe 2012–2021. We find that PCL is positively correlated with increasing democracy levels (and resistance to democratic backsliding) across Europe. More significantly, this relationship holds independently for both Eastern and Western Europe, with the PCL effect being stronger in the East.

Introduction

The past decade has been a turbulent one in modern European politics, both for the older, more longstanding democracies of the West and the more recently democratized post-Communist states of the East. While an earlier period of democratization in those parts of post-Communist Europe destined for EU membership was assessed to be successful on the basis of institutional criteria (Ekiert et al., Citation2007, p. 20), the factor most often blamed for these subsequent democratic stresses – illiberal populism – is an essentially ideational force (Müller, Citation2013) of a kind neither anticipated nor easily addressed in the legal-institutional sphere. To address such challenges, scholars are increasingly examining the deliberative socio-cultural spheres in which political identities are forged in ways that either chime or conflict with liberal democratic norms.

Most existing cultural-discursive accounts of (de)democratization in Europe are qualitative in orientation (Dawson & Hanley, Citation2016, Citation2019; Rechel, Citation2008; Sasse, Citation2008). To explore whether quantitative support may be found for cultural-discursive understandings of democratization, we turn for inspiration to recent research on global support for democracy, a paradigm that has always started from the assumption that it is through cultural change rather than institutional reform that democracy takes root. Much of this research is global and macro-historical in scope (Cho, Citation2014; Dalton et al., Citation2007; Shin & Kim, Citation2018; Welzel, Citation2013), helping to explain why it is seldom cited in attempts to understand why democracy has held up somewhat better in, say, Slovenia than Hungary. It is for this reason that we have sought to recalibrate this research agenda, both theoretically and empirically, to explore whether levels of cultural support for liberal democracy have measurable effects in Europe over the short-to-medium term.

The aim of this paper is two-fold. In the first instance, it seeks to theoretically justify, then construct and operationalize a measure to identify cultural liberals as individuals from the European Social Survey, a pan-European dataset. Broadly congruent with the new cleavages literature, we conceptualize Cultural Liberals as ‘supporters of the new social movements’ (Bornschier, Citation2010), noting that many of these causes – ethnic and sexual minority rights in particular – have subsequently been codified as part of the liberal democratic template. In the second instance, it tests the relationship between the ‘Proportion of Cultural Liberals’ (PCL) within national cohorts and levels of democratization/democratic regression between and within East and West Europe 2012–2021 as measured by V-Dem and Freedom House.

We find that PCL is strongly positively correlated with democracy levels in the pooled pan-European sample. This is relatively unsurprising given that Europe may be divided into a Western half where the gradual triumph of social movements in societies has led to the institutionalization of corresponding liberal democratic institutional forms and an Eastern half where the adoption of these same culturally liberal institutional forms was more recent and was more driven by external forces. The strength and direction of the relationship in the pooled sample is mostly driven by the differential performance of West European cases on the one hand – where PCL and democracy levels are high – and East European cases on the other – where PCL is lower and levels of democracy generally either remain middling or fall over the period of analysis.

When examining Eastern and Western Europe as separate regions, however, we find that the positive and statistically significant relationship between the percentage of cultural liberals and democratization holds in both. In Western Europe, the effect, as befits a region consisting of long-standing democracies, is smaller than in the newer and more volatile democratizing states of Eastern Europe, where the PCL effect is larger and stronger. Over a decade characterized by many political scientists as one of ‘democratic backsliding’ and explained by some in terms of the loss of ‘EU leverage’ after the Accession of most of that region into the EU during the 2000s, we argue that larger proportions of committed cultural liberals among national populations help to explain where democracy has held up better and that smaller proportions of cultural liberals correspond to where it has collapsed more dramatically.

This article is structured as follows. First, we review existing literature on the link between culture and democracy in Europe. After that, we consider the possibility that recent developments in survey research on global support for democracy could add empirical grist to this hitherto mainly qualitative research paradigm. Taking inspiration from both the emancipative values thesis and agonistic democratic theory, we present a new and more exacting measure of cultural liberalism. After presenting our findings, the discussion considers the relevance of the findings to debates about the East–West democracy divide in Europe.

Could cultural liberalism help explain the East–West democracy divide in Europe?

While democracies in both halves of the continent have been touched by a ‘global rise in illiberal populism’ (Müller, Citation2013), it is among the Eastern members of the European Union that democracy scores have been regressing fastest (Sedelmeier, Citation2023). Following on from a strand in the democratic transitions scholarship cautioning that institutions are only as strong as their support in wider society dictates (Alexander, Citation2001), we explore whether at least part of the explanation for both this East–West gap and intra-regional variation lies in cultural support for the dimensions of liberal democracy most likely to conflict with majoritarian interests.

Starting with Bornschier’s (Citation2010) definition of ‘cultural liberalism’ as ‘support for the goals of the New Social Movements’, advocating peace, gender equality, opposition to racism and so on, it is evident from survey analyses that these kinds of political identities have much deeper roots in the Western half of Europe (Pew, Citation2018). The starkness of this divide may be illustrated nowhere better than by a mapped data visualization showing the spread of the Twitter hashtag #RefugeesWelcome on 3rd September 2015. Western Europe up to the old Iron Curtain was a thousand points of light; Eastern Europe was dark (Hanley, Citation2015; Differential East–West political responses to European Refugee Crisis are covered in Schweiger, Citation2023).

While the label ‘cultural liberalism’ emerges from ‘new cleavages’ research on West European politics, the impetus for considering the role of these kinds of political identities in upholding democracy comes from the democratization literature focussed on East-Central Europe (ECE).Footnote1 Despite significant analytical differences, both rationalist and cultural-discursive traditions typically attribute parts of the causal story to cultural factors.

In outline terms, the influential rational institutionalist account ran as follows. By offering the carrot of incentives (ultimately adding up to membership, known to bring financial rewards) and the stick of sanctions (pushing a candidate further back in the queue), the EU was successfully able to manipulate the utility calculations of domestic East Central-European politicians and publics to the extent that convergence upon a common liberal democratic institutional settlement was achieved (Börzel & Risse, Citation2012; Grabbe, Citation2006; Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, Citation2005; Vachudova, Citation2005).

Despite this analytical emphasis on formal institutional structures, these accounts do not exclude the possibility that cultural-ideal factors may constitute some part of the analytical model. In fact, the importance of cultural factors was very frequently affirmed. Ekiert, Kubik and Vachudova’s oft-cited account of the success of EU-led democratization is haunted by repeated exhortations that these democratized states still need to develop ‘a proper democratic culture’ (Ekiert et al., Citation2007). With respect to the question of how democratic institutions would endure absent EU leverage after accession, many borrowed from the culturalist lexicon, as with frequent invocations of elite and mass ‘socialization’ (Levitz & Pop-Eleches, Citation2010). In this vein, Schimmelfennig envisaged a shift over time from liberal-democratic norm-compliance based on cost–benefit calculation towards a more thoroughgoing commitment, ultimately adding up to identity change (Citation2007).

Cultural-discursive accounts actually foregrounded socio-cultural and experiential elements of democratization where rationalist accounts saw these elements as secondary to EU-leverage-induced institutional reforms. In general, this approach led to much greater scepticism with respect to the extent of democratization achieved (Alexander, Citation2001; Hughes et al., Citation2004). For example, Sasse’s account of minority rights reform in the Baltic states highlighted that the optimistic hopes of rationalist authors for elite socialization were contradicted by available evidence (Sasse, Citation2008). More emphatically, Rechel reported that while formal compliance with the EU’s minority rights regime had proved enough to achieve accession, it was not noticeably altering the conditions under which the region’s minorities lived (Rechel, Citation2008).

In recent years, authors in the rationalist tradition have tended to recognize that some degree of democratic backsliding has taken place, but to stress that the region presents a mixed picture beyond the two most dramatic backsliding cases of Hungary and Poland (Börzel & Schimmelfennig, Citation2017; Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, Citation2020; Sedelmeier, Citation2023).

Among cultural-discursive accounts, on the other hand, there is widely shared agreement on the region-wide character of democratic malaise. The key point of debate concerns whether to describe this malaise as ‘backsliding’, which many do, stressing key weaknesses in spheres such as civic participation (Greskovits, Citation2015) and deliberation (Gora & de Wilde, Citation2022). Others have argued that the shared assumption behind both rationalist scholarship and the EU’s conditionality model of democratization – that voters and elites in the East were only wedded to liberal democratic norms to the extent that they were externally constrained to do so – brings into question the very notion that these states had successfully democratized in the first place (Dawson & Hanley, Citation2016; Herman, Citation2016).

Despite this widespread invocation of ‘culture’ as a causal variable across these theoretical divides in research on ECE democratization, there has been little cross-fertilization of ideas with the mainstream literature on ‘global support for democracy’, a mostly quantitative research paradigm that is already closely trained on the socio-cultural sphere of democratizing societies. We feel it is representative, for example, that none of the authors in the cultural-discursive tradition cited above make reference to survey research on support for democracy.

Part of this reluctance is likely to stem from a clash between the constructivist philosophical commitments of cultural-discursive democratization scholars and the positivist roots of much ‘values survey’ research in modernization theory (after Inglehart, Citation1971). Despite this, it is undeniable that there remains a certain ‘family resemblance’ between the philosophically inspired assumption that democracy needs to be ‘reflected in the ideas that people hold and value’ (Blokker, Citation2009, p. 4) and the statistically supported claims of values survey scholars like Christian Welzel that democracy is a ‘culture-bound phenomenon’ (Brunkert et al., Citation2019). At the very least then, it would seem to be worth investigating whether this branch of inquiry can yield hard data to support cultural-discursive claims about democratic resilience/ vulnerability in Europe.

Research on cultural support for liberal democracy

Recent research on support for democracy, we argue, provides some tools to help us understand the extent to which ideal and cultural factors may impact upon the stability of European democracies. However, while techniques designed to produce global and macro-historical claims about democracy might be useful for identifying divergences between East and West Europe, they need to be recalibrated, both theoretically and empirically, if they are also to be of use in helping us to understand why democracy might be holding up better in say, Slovenia rather than Hungary.

Since an earlier generation of values research stressed near universal support for democracy even in authoritarian countries (Klingemann, Citation1999; Norris, Citation1999), increasing attention has been paid by values researchers to subjective understandings of democracy. In this vein, values researchers now often find that citizen’s declared support for democracy is much less substantive than previously thought (Ananda & Bol, Citation2021; Shin, Citation2017); citizens of non-democratic countries, while generally professing support for democracy, are either ‘unable to differentiate democracy from its alternatives’ (Shin & Kim, Citation2018, p. 243), more likely to associate it with ‘a prospering economy and social control’ (Zagrebina, Citation2020), or simply liable to revert the meaning of support for democracy to support for authoritarianism (Cho, Citation2014; Ulbricht, Citation2018).

One attempt to grapple with subjective meanings of democracy has been the inclusion, since early this century, of an open-ended question on the World Values Survey that presents respondents with the incomplete sentence ‘Democracy means … ’, allowing them fill in up to three concepts that they associate with democracy. Very frequently, it seems, respondents have chosen to fill in this section with ideas like ‘liberty’, ‘freedom’ and ‘saying whatever you want’ (Canache, Citation2012, p. 8). Thus, some of the early findings from analyses of this questionnaire item echoed earlier democratic optimism in reporting that liberal understandings of democracy predominate even in authoritarian corners of the globe (Canache, Citation2012, p. 1; Dalton et al., Citation2007).

However, the association of terms like ‘freedom’ and ‘liberty’ with liberal understandings of democracy establishes a very imprecise standard (Schaffer, Citation2014). Such findings are of limited use for understanding whether citizens in a given part of the world could or could not live with minority rights or judicial restraints on elected leaders.

One strand of values study research that does seriously engage with the liberal philosophical dimension as a determinant of democratization is the ‘emancipative values’ thesis of Christian Welzel and his collaborators (Brunkert et al., Citation2019). The authors’ key finding is as follows: positive liberal democratic change is not predicted simply by citizens declaring an aspiration for ‘democracy’ but only when this aspiration is matched with a ‘cultural foundation’ that is grounded in support for ‘universal freedoms’ (Brunkert et al., Citation2019, p. 423). Without this ‘cultural foundation’, they find – similar to some studies cited above (Cho, Citation2014; Ulbricht, Citation2018) – that ‘support for democracy frequently reverts its meaning, indicating the exact opposite of what intuition suggests: namely, support for autocracy’ (422).

This ‘cultural foundation of liberal democracy’ is approximated by measuring people’s emphasis on universal freedoms based on World Values Survey questions. What results is the ‘emancipative values index’ (EVI), a national-level mean generated from 12 questions in total relating to four themes: child autonomy, gender equality, voice (freedom of expression) and sexual emancipation. The time series analyses, regressing EVI against democracy indicators, are made more powerfully predictive by the fact that the authors used ‘cohort effects’ to simulate EVI scores going back to 1960 based on a WVS dataset that only actually goes back to 1981.

As can be inferred from this description, the scope of this research programme – targeting the effect of macro-cultural change on democratization across the entire globe over a period from 1960 onwards – is enormous. To facilitate an analysis on the more proximate scale of (de)democratization in Europe would require a recalibration of both the empirical tests and the theoretical assumptions on which they depend.

Cultural liberalism: a more exacting measure of cultural support for liberal democracy

Given the more geographically – and time-limited scope of this investigation relating to short-term (de-)democratization in Europe, we find it necessary to conceptualize ‘cultural’ support for democracy more concretely in terms of support for specific liberal-democratic norms. In short, we seek to find citizens who support and can potentially uphold those institutional elements of liberal democracy which, though already codified as part of the template and measured by most institutionally focussed databases, may be seen as vulnerable because they conflict with majoritarian political and social norms.

We use European Social Survey’s 2012 special section on ‘Understandings of Democracy’, the most theoretically sophisticated battery of questions on the topic to date (Quaranta, Citation2018, p. 7). In choosing the questions, we have sought to be as parsimonious as possible, limiting ourselves to six questions by avoiding ‘valence’ questions that target such overwhelmingly popular features of democracy as elections. We further take for granted that even Post-Communist Europe appears near the top of the global table on dimensions such as support for female leaders and rejection of ‘strong [authoritarian] leadership’ (Anderson et al., Citation2022). Accordingly, we focus in particular on anti-majoritarian norms that usually turn out to be the aspects of democracy that are often hard to institute where absent and likely to require energetic defence where present (Dawson & Hanley, Citation2016).

As such, five of the six ESS items we have chosen to identify individuals as ‘Cultural Liberals’ (CL) – protection of LGBT (1) and minority rights (2), protection of opposition (3) and media freedom (4), support for the court’s role as a checking mechanism against the state (5) – are chosen so as to demonstrate support for the potentially anti-majoritarian liberal institutional norms most likely to lapse. Another way to express this is that all these items serve to guarantee the core liberal democratic norm of pluralism, a norm is assailed on several fronts in the wave of illiberal populism that has driven democratic volatility in the early decades of this century.Footnote2 Furthermore, by insisting on emphatic support for each of these norms to qualify as CL, which is to say fulfilment of all criteria rather than using the items to generate means, we guard against the likelihood that CL support for democracy melts away when it is needed most. Given this imperative for mobilization-readiness, the sixth ESS item that completes our criteria for Cultural Liberalism is ‘Interest in Politics’, which we use as our ‘activity’ filter because it is the least imperfect fit with the Aristotelian notion of political action underpinning deliberative theory (see Arendt, Citation2013 [Citation1958]).Footnote3

We further diverge from the emancipative values programme in that we do not share many optimistic, semi-teleological assumptions arising from its grounding in modernization theory (after Inglehart, Citation1971). So long as economies are growing and more citizens are being freed from preoccupations with ‘survival’, this line of thinking goes, then a growth in diffuse emancipative values must lead to a growth, following a generational lag, of liberal democracy (Brunkert et al., Citation2019). Against this, we note that the economies of Hungary and Poland had been booming for some time when illiberal populist governments were elected, who have subsequently eroded democratic institutions. The Hungarian case in particular suggests that citizens’ experience of escaping economic precarity, leading to a growing middle class, can actually cement support for authoritarian leadership (Szikra & Orenstein, Citation2022). Thus, we do not think the expansion of economic security will necessarily foster emancipative values or restore democracy in these countries.

By contrast, theories of change rooted in deliberation pay more attention to which ideas are being spread through practices of public sphere deliberation. When the ideas being spread are emancipatory ones, as in the post-war period in Western Europe, we are liable to see a growth in democratization. However, as Peter Stamatov notes with reference to Bulgaria in the 1990s, illiberal publics may also be formed because the terms of public debate are not always rational, critical, or liberal (Stamatov, Citation2000). The spread of ideas, if one follows this deliberative logic, can equally presage the expansion of liberal rights or their reversal (as in democratic backsliding), depending very simply, on whether the prevailing ideas themselves support or conflict with liberal-democratic norms.

The key model of emancipatory mobilization that is sometimes referenced in relation to the current predicament of ECE is West Germany between the late 1960s and early 1970s (Krastev, Citation2007). In short, we read the social tumult that shook the foundations of a society that had already largely succeeded against most benchmarks of institutional democratization as an absolutely necessary phase in the democratization of West Germany in the cultural sense. The key fact is that an oppositional public bearing emancipatory and (usually also) pro-democratic ideas challenged and ultimately defeated the socially conservative (and historically amnesiac) political consensus upon which Post-War West Germany functioned. Good things would also follow in the legal-institutional sphere: V-Dem records piecemeal improvement at the timeFootnote4 and, looking further ahead, it is hard, for example, to imagine Germany’s gradual abandonment by the end of the century of its once illiberal ‘guest worker’ immigration system (Walzer, Citation1983, pp. 52–63) without the steps taken towards the wider transformation of society decades earlier.

This understanding of pro-democratic political change is inspired by the ‘agonistic’ branch of normative democratic philosophy. Chantal Mouffe’s influential account postulates, in outline terms, that a healthy democratic society is not one that achieves consensus, which is liable to ‘mask the frustrations of a diverse society’ but one of ‘agonistic pluralism’ in which ‘meaningfully differentiated positions’ that cannot be ‘negotiated away’ are represented (Mouffe, Citation1999). The foundational assumptions underpinning this account depart from those that prevail in rationalist political science in at least two important respects. First, rather than political ideas and the party systems they give rise to functioning as a ‘natural system of channelment’ for the [pre-existing] interests in society (Sartori, Citation2005 [Citation1976]), citizens’ political identities are seen as being formed primarily in response to available political discourses. By Mouffe’s account, ‘radical democratic citizenship’ – a type of political identity closely related to what we call cultural liberalism – is liable to emerge when creative political actors articulate diverse causes together in the public sphere, making possible forms of political solidarity that did not exist before (Laclau & Mouffe, Citation2014 [Citation1985]). Second, and relatedly, agonism does not seek ‘moderation’ in the form of ‘party system institutionalization’ or fear polarization. Indeed, as in the cited exemplar of post-1968 West Germany, the polarization and conflict that arises as a result of radical democrats/ cultural liberals rejecting compliance with the (usually socially conservative) norms that previously defined the parameters of political competition may be seen as a necessary phase in the realization of ‘fully’ liberal democracy.

The medium-term success of the mobilization in West Germany did not depend on majoritarian support, still less on electoral victory; in this sense it was analogous to other historical instances in which ‘oppositional counterpublics’ often representing marginalized social groups such as ‘women, workers, and people of colour’ formulated oppositional ‘interpretations of their identities, interests and needs’, and successfully drove the expansion of the public sphere (Fraser, Citation1990). However, as with other causes such as women’s suffrage in the UK and black civil rights in the US, the size of mobilization does matter. We do not dispute that a range of factors must be present to support democracy, so we do not claim that there is any ‘magic number’ beyond which ‘democratic consolidation’ is assured. Our assumption in using survey data to generate a national ‘Proportion of Cultural Liberals’ (PCL) is simply that a society in which 30 per cent are ready to mobilize in support of the anti-majoritarian liberal norms will exert stronger upward pressure upon the level of democracy (and stronger resistance to regression) than one with 3 per cent.Footnote5

We also do not deny the fact of an endogeneity loop in the relationship between liberal culture and liberal institutions. Clearly, just as rises in liberal values can be found to predict democratization (Brunkert et al., Citation2019), so support for liberal values will tend to diminish over time in contexts where authoritarian political regimes seek to suppress them (Ulbricht, Citation2018). In the European context at least, however, we can say with some confidence that this is not a simple chicken-and-egg conundrum. Liberal ideas triumphed first in the public sphere and only later did that triumph lead to the construction over centuries of legally binding institutions (Habermas, Citation2015 [Citation1992]). The EU’s modus operandi of mandating institutional form couched in the language of ‘technical’ reforms ignored the fact that institutions like the separation of powers and minority rights were the ‘historical realization’ of norms such as pluralism and civic tolerance that had been publicly validated through discussion and contestation (Blokker, Citation2009, pp. 1–4). Where the EU’s conditionality policies rested on a bet that culture follows institutions, our scepticism on this point seems to find support in survey research projects that have identified the opposite causal relationship between cultural-ideal values and institutional quality (Brunkert et al., Citation2019; Canache, Citation2012; Norris, Citation1999). We also note the still relatively low proportion of cultural liberals in in our data for ECE states that had achieved institutional democratization a decade earlier (see below).

It is on these theoretical and empirical bases that we wager that the antidote to democratic backsliding in ECE – and in the longer term, the route to a more liberal democracy in the cultural sense – runs through the emergence of culturally liberal counterpublics that challenge the often tacitly illiberal discourses that occupy the mainstream of political competition (Dawson & Hanley, Citation2016), which we see as the ultimate reason why anti-majoritarian institutions so often lapse. Such mobilization-ready counterpublics were perhaps evident, albeit on a smaller and less decisive scale, in the waves of mobilization in places as diverse as Slovenia in 2013 and Bulgaria in 2013–2014 (Bieber & Brentin, Citation2018). Do culturally liberal counterpublics advance or else aid the durability of democratic institutions? This study aims at uncovering whether the available survey data confirms this link or not.

Hypotheses

Our main research question is as follows: Does the proportion of cultural liberals (PCL) in a national population affect democratization over the course of the past decade (2012–2021)? In our use of the terms democratization and its derivatives like de-democratization (or democratic backsliding), we are following usage that is common in research on comparative European politics, less so in research on global support for democracy. By democratization, we mean any increase in democracy levels, even at the incremental level that does not involve crossing a threshold from one regime-type to another. By de-democratization (or democratic backsliding), we mean any decrease in democracy levels. We argue that there is a positive relationship between the proportion of committed cultural liberals within a population and levels of democracy. We tested the following hypothesis:

H1: The higher the proportion of cultural liberals (PCL) in European societies, the higher the level of democracy

H2: Having a higher proportion of cultural liberals (PCL) would have a larger and stronger effect on increasing democracy levels in Eastern Europe compared to Western Europe

Methods

The ESS dataset contains nationally representative samples for 29 countries, inclusive of those both inside and outside the EU in 2012. Of these Turkey is excluded as it does not reasonably fit into our categories of ‘Eastern’ (Post-Communist) or ‘Western’ Europe, while Iceland and Kosovo are excluded because of substantial missing data. Thus, 15 Western and 11 Eastern (Post-Communist) cases are included in the analyses.

One key limitation of the data used in this study is that, although the ESS is collected biannually, the ‘Understandings of Democracy’ Special Section has only so far appeared in 2012, meaning that the measurement of Percentage of Cultural Liberals by country shown in below – and regressed against various democracy measurements further on – is based on a single data collection point. Consistent with Welzel and his co-authors (Brunkert et al., Citation2019), we expect that cultural orientations, while mutable, change only gradually, unlike say, democracy scores which can rise or fall rapidly after events like elections, especially at the aggregate country level. Our measurement of the effect of PCL in 2012 on changes in democracy covers the past decade (2012–2021).

Democracy in Europe under a period of stress: 2012–2021

The ending of the main period of the EU’s democratic leverage prior to the beginning of our period of observation has the effect of equalizing the external context against which the effects of PCL on levels of democracy can be measured. Over the past decade, the whole continent – Western Europe, the newer Eastern members of the EU and Eastern non-members – can be understood as sharing a common context in which liberal democracy is experiencing a global stress test arising from the fallout of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 (inclusive of the ensuing Eurozone crisis) and the related wave of illiberal populism. It is for this reason – relatively equal external context – that we do not constrict our dataset to omit non-EU cases; thus, Switzerland and Norway fit into the West category while Russia, Ukraine and Albania fit into the East.

Independent variable: proportion of cultural liberals (PCL) – an individual-level metric derived from the European social survey

The Special Section on ‘Understandings of Democracy’ in the 2012 European Social Survey (ESS) asks respondents to answer ‘how important’ certain norms are to democracy, allowing an individual-level scale to be constructed. In essence, we seek to find citizens who support and can potentially uphold those institutional elements of liberal democracy which, though already codified as part of the template and measured by most institutionally focussed databases, may be seen as vulnerable because they conflict with majoritarian political and social norms.

In formulating a country-level PCL measurement, we implemented three steps. First, we select six individual-level components to identify cultural liberals as individuals: protection of LGBT and minority rights, protection of opposition and media freedom, support for the court’s role as a checking mechanism against the government, and interest in politics (α = 0.71).Footnote6 As described above, we insist on (emphatic) agreement with each item to qualify as CL. In formulating ‘cultural liberalism’ this way, we include some who would not self-identify as ‘liberals’ and exclude many who would. We prioritize citizens’ function relative to (de)democratization over self-ascribed labels or, for that matter, voting patterns, which often, in the European context, reflect economic policy orientations.

Second, we transform the variables, which use different measures, into binary variables: 1 represents individuals who indicate strong preference or agreement with the item statement while 0 represents the remaining individuals. We then multiply all six binary variables to create a cultural liberalism scale with 1 representing individuals who show strong preference or agreement on every component and 0 representing all other preferences. We then divide the total number of culturally liberal individuals by the total number of sampled respondents per country to estimate the proportion of cultural liberals within the population of each country. For example, we took the number of cultural liberals in Albania (n = 147) and divide it by the total number of Albanians sampled (n = 1,087), which gives us an (unweighted) estimation of 13.52 per cent proportion of cultural liberals (PCL). The calculation is repeated for the remaining 25 countries. The overall mean of PCL in the pooled sample is 19.88 per cent.

Overall, our sample confirms our assumption that PCL levels will be higher in West Europe compared to the Post-Communist East. Scandinavian states like Denmark (46.32) and Sweden (38.43) as well as Germany (40.14) cluster at the most culturally liberal end of the pooled sample while Post-Communist states Ukraine (3.68) and (perhaps surprisingly) Lithuania (1.65) are found to be least culturally liberal. There is a substantial and significant difference in PCL between the two regions. T-tests further confirm that the 16.72-point inter-region difference is statistically significant at p < 0.001. The focus on this East–West divide however, masks substantial intra-regional variation, some of which is noteworthy – for example, Bulgaria, Poland and Slovenia record close to the pan-European mean while Portugal and Cyprus report significantly below. Indeed, it is the fact of this substantial intra-regional variation that allows us to consider the relationship of cultural liberalism with intra-regional variation in democratic performance, that is particularly pronounced in ECE (Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, Citation2020). below shows the distribution of PCL per country and region.Footnote7

Table 1. Distribution of PCL in European countries (weighted).

Dependent variable: levels of democracy

We focused on country-level democratic scores spanning 2012–2021 from two datasets (see ). The first dependent variable is the Liberal Democracy Index from Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), which consists of polyarchy and liberal democracy components. The second DV is Freedom House’s (FH) expert evaluation of political rights and civil liberties.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of V-Dem and Freedom House indices.

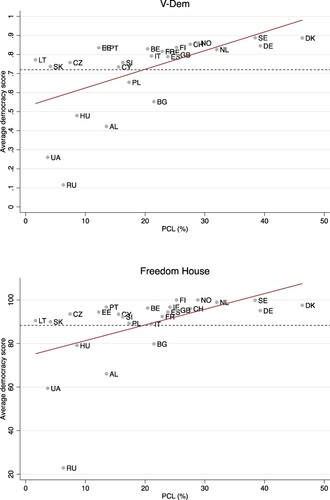

Overall, there are significant differences in the mean democracy scores between East and West Europe across the two indices, with West European countries scoring higher on average in democracy levels than East European countries, which are significant at p < 0.001 (see online appendix B). Furthermore, there is a positive correlation between PCL and democracy quality, suggesting that increases in PCL levels corresponds with increases in democracy scores on both the V-Dem and FH measurements. below shows the correlation between PCL and democracy levels.

Control variables

To test the robustness of our estimations, we also included measures of socioeconomic and institutional variables to control for systemic differences between countries and regions. Our models acknowledge this because studies have shown that socioeconomic variables like GDP per capita and inequality (GINI) are strong determinants of democratic stability. We also included a measure of public perception of corruption within state institutions, which has been associated with lowered democracy ranking and diminished regime support and institutional trust (Mishler & Rose, Citation2007) .

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of control variables.

Results

In our analysis of the effect of PCL on levels of democracy, both our hypotheses are confirmed: PCL has a significant and positive effect on democracy levels among European countries, and a greater effect in East Europe than in West Europe. below shows that a one percent increase in PCL corresponds to a 0.016 increase in the democracy level on the V-Dem (0–1) scale and a 0.681 increase in the democracy level on the FH (0–100) scale. For V-Dem, the effect holds with the introduction of control variables, reducing the effect size slightly while maintaining a positive relationship between PCL and democracy levels. Using the FH scale, the effect is larger but becomes insignificant. We suspect that this is driven by a variation in PCL effect between regions, which is the underlying assumption of our second hypothesis.

Table 4. OLS regression analysis of the effect of PCL on democracy quality in Eastern and Western Europe.

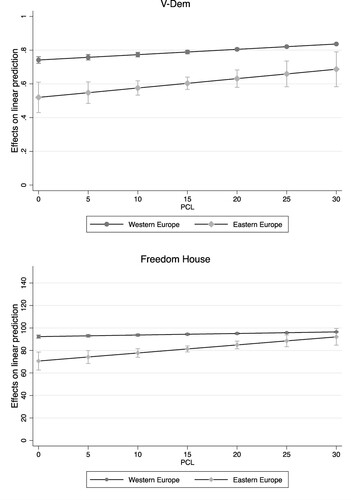

To test H2, we interacted PCL with region to get an estimate of the differential effect of PCL on democratic growth. confirms our expectations that PCL effect is indeed larger for Eastern Europe than for Western Europe, and that the effect is robust to the inclusion of control variables. A percentage increase of PCL corresponds to an additional increase of the democracy level by .004 points on the V-Dem scale and .764 points on the FH scale higher in Eastern Europe relative to Western Europe.

Table 5. OLS regression analysis of the effect of PCL on democracy quality with regional interaction effects.

more clearly illustrates the regional difference of the effect of PCL on democracy levels. Specifically, how higher PCL more substantially increases democracy levels in Eastern relative to Western Europe – though the marginal effect observed on the V-Dem scale is smaller compared to the FH scale. This would suggest that Eastern European countries could potentially match the democracy levels of Western European countries given a high enough PCL.

Discussion and conclusions

In outline, the theoretical rationale for quantifying the Proportion of Cultural Liberals (PCL) in a country was as follows. The democratic template most often applied in contemporary Europe references some majoritarian and overwhelmingly popular institutions such as elections. However, it also mandates a set of liberal institutions that are partly designed to check majoritarian impulses: judicial independence, media independence, and the rights of ethnic and sexual minorities. If one starts from the proposition that democratic institutions are only liable ‘to enjoy stability and longevity’ to the extent that people identify with the norms embodied by them (Blokker, Citation2009, pp. 1–4), then liberal democracy really ought to hold up better where a higher proportion of citizens are ‘cultural liberals’ in the exacting sense that they are ready to uphold its anti-majoritarian elements. The statistical analyses described above suggest that this intuition is basically correct.

This analysis reveals a positive and statistically significant relationship between the proportion of cultural liberals in a given national population and democracy levels across Europe. Furthermore, our results show differential effects of PCL on democracy levels, with Eastern Europe benefiting more from increasing PCL than Western Europe. The effects are statistically significant and robust to the introduction of control variables. This suggests that this relationship is not merely an artefact of the different historical trajectories of the Western and Post-Communist regions of Europe. These results allow for some elaboration with respect to how cultural support bolsters liberal democracy in general and how this impacts upon debates surrounding an East–West divide in Europe.

Though our database covers only Europe, we consider it is very likely that cultural liberals – understood in the exacting activist and anti-majoritarian terms identified in this project – do not form an absolute majority in any country. However, this does not mean they cannot triumph – especially in the West after World War II, social movements in favour of causes such as gender equality, civil rights, and environmental action have successfully expanded ‘the democratic horizon’ (Brunkert et al., Citation2019) despite not enjoying the support of electoral majorities. Despite the gradual growth in support across the West for these basic ideas, it remains an activist minority that effectively guarantees the gains won by these movements in the face of opposition that often has the weight of majoritarian electoral support behind them. According to this model then, and in stark opposition to a political science orthodoxy stressing the perils of polarization (after Sartori, Citation2005 [Citation1976]), it is the culturally liberal ‘counter-public’ that both makes and keeps liberal democracy ‘liberal’ in the ‘advanced democracies’ in our study like Denmark, Germany and, to a lesser extent, the UK.Footnote8

Do our results suggest that the East–West democracy gap in the EU is liable to continue widening? The answer for the short term is probably yes. As partisans of the cultural-discursive school of democratization, we are not surprised by the scale of democratic erosion recorded in the EU’s Eastern member states. The considerable gap between the proportions of cultural liberals in East and West in our data corresponds to Bohle and Greskovits’ observation that while Western Europe’s democracies were built on a core of mass political and civic engagement, Post-Communist democracies were ‘born with a hollow core’ (Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012, p. 239). This effect was compounded by the superficial nature of the latter region’s democratization that was driven by the pragmatic responses of domestic governments to the rationalist ‘stick and carrot’ mechanisms at the heart of the EU’s conditionality processes. Liberal institutions are tending to lapse in the post-EU Accession absence of external constraint because they were implemented on the basis of elite calculation in the absence of wider societal support. This unravelling process may have some years yet to run.

Yet all is not lost. An extension of this logic would stake the future of democracy in the region on the emergence of liberal counter-publics willing to directly confront illiberal nationalist and socially conservative forces that shape the parameters of politics in the region (Dawson & Hanley, Citation2016). Given that our data shows the positive effect of the growth of cultural liberalism on improvements in democracy levels, we should take heart from the increasing audibility and visibility of such movements. While street-based mobilisations have taken place with increasing regularity across the region since the early 2010s (Bieber & Brentin, Citation2018), Poland deserves a special mention. The country continues to experience democratic backsliding under the rule of the religious-right Law and Justice Party, but it is also now notable for the vehemence and organization of its unbowed and proudly feminist opposition (Gwiazda, Citation2021). Where the region’s liberals once opted to accommodate rather than oppose illiberal and socially conservative actors, a younger generation is not afraid to mobilize in a way that is analogous in attitude if not yet in scale to the West German student protesters of 1968.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.3 KB)Data availability

An online appendix has been submitted along with this paper. Beyond that, the raw data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to several colleagues who read and provided comments on earlier drafts, resulting in a much improved paper. These colleagues include Damien Bol, Tanja Börzel, Eleanor Brooks, Licia Cianetti, Seán Hanley, Andrew Hunter, three anonymous reviewers and several of the co-editors and contributors to the special issue “The East-West Divide: Assessing the Growing Tensions within the European Union”, among whom particular thanks are due to Clara Volintiru.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest relating to this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term ‘cultural liberalism’ (and other overlapping concepts) has already been applied to European politics (Bornschier, Citation2010; Kriesi et al., Citation2012; Koopmans & Zurn, Citation2019). However, while this ‘new cleavages’ research is pioneering in its use of survey instruments to model emerging political conflict structures under conditions of democracy, its aim is generally not to gauge the health of those democracies. Koopmans and Zurn, for example, explicitly disavow any attempt to ‘moralise’, viewing normatively loaded scholarship as being part of the political claims-making process (Citation2019, pp. 3–4).

2 In the context of democratic backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe, for example, leaders known for employing illiberal populist rhetoric declaring various categories of person – say ‘homosexuals’, or ‘Communists’ – as outside the national community have used the same anti-pluralist logic in presenting ‘the idea of distorting the democratic playing field by stripping away institutional checks and balances of constitutional liberalism thinkable, acceptable, even necessary’ (Dawson & Hanley, Citation2019, p. 8). By this account, it is the antipathy to pluralism that explains why a ratcheting up of exclusivist rhetoric (referenced in items 1 and 2 on our scale) is so often accompanied by institutional power grabs (items 3,4,5), ultimately leading to democratic backsliding in the form of ‘executive aggrandizement’ (Bermeo, Citation2016).

3 We reject ‘participation’ as it is itself usually a composite of individual items that do not, we feel, improve upon ‘political interest’. Statistically speaking, the alpha score and eigenvalue are also higher with the inclusion of ‘interest in politics’ (see online appendix A).

4 West German Liberal Democracy Index (LDI) score rose from 0.8 in 1968 to 0.82 by 1970 (V-Dem).

5 By this account, the gradual orientation of ‘mainstream publics’ away from illiberal opposition to anti-majoritarian liberal democratic norms (or ‘mass socialisation’) is conceptualized as the by-product of the activities of a committed (liberal) counterpublic. It is for this reason that we opt to focus analytically on cultural liberals only, rather than on the attitudes of national populations at large.

6 Full statements, descriptive statistics, and detailed coding process are included in Online Appendix A.

7 For weighted distribution, see Table A3 in Online Appendix A. Our estimations use unweighted calculation of PCL.

8 We accept that an application of this framework beyond European (and other Western) contexts would not be straightforward. Further research would be required to ascertain this point.

References

- Alexander, G. (2001). Institutions, path dependence, and democratic consolidation. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 13(3), 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/095169280101300302

- Ananda, A., & Bol, D. (2021). Does knowing democracy affect answers to democratic support questions? A survey experiment in Indonesia. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 33(2), 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edaa012

- Anderson, C., Bol, D., & Ananda, A. (2022). Humanity’s attitudes about democracy and political leaders. Public Opinion Quarterly, 85(4), 957–986. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab056

- Arendt, H. (2013). The human condition. University of Chicago Press.

- Bermeo, N. (2016). On democratic backsliding. Journal of Democracy, 27(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0012

- Bieber, F., & Brentin, D. (Eds.) (2018). Social movements in the Balkans: Rebellion and protest from maribor to taksim. Routledge.

- Blokker, P. (2009). Multiple democracies in Europe: Political culture in new member states. Routledge.

- Bohle, D., & Greskovits, B. (2012). Capitalist diversity on Europe’s periphery. Cornell University Press.

- Bornschier, S. (2010). The new cultural divide and the two-dimensional political space in Western Europe. West European Politics, 33(3), 419–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402381003654387

- Börzel, T., & Risse, T. (2012). From Europeanisation to diffusion: Introduction. West European Politics, 35(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.631310

- Börzel, T., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2017). Coming together or drifting apart? The EU’s political integration capacity in Eastern Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(2), 278–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1265574

- Brunkert, L., Kruse, S., & Welzel, C. (2019). A tale of culture-bound regime evolution: The centennial democratic trend and its recent reversal. Democratization, 26(3), 422–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1542430

- Canache, D. (2012). Citizens’ conceptualizations of democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 45(9), 1132–1158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011434009

- Cho, Y. (2014). To know democracy Is to love It. Political Research Quarterly, 67(3), 478–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912914532721

- Dalton, R., Sin, T., & Jou, W. (2007). Understanding democracy: Data from unlikely places. Journal of Democracy, 18(4), 142–156.

- Dawson, J., & Hanley, S. (2016). What's wrong with east-central Europe?: The fading mirage of the”. Liberal Consensus. Journal of Democracy, 27(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0015

- Dawson, J., & Hanley, S. (2019). Foreground liberalism, background nationalism: A discursive-institutionalist account of EU leverage and ‘democratic backsliding’ in east central Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(4), 710–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12845

- Ekiert, G., Kubik, J., & Vachudova, M. (2007). Democracy in the post-communist world: An unending quest? East European Politics and Societies, 21(1), 7–30.

- Fraser, N. (1990). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Social Text, 25/26(25/26), 56–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/466240

- Gora, A., & de Wilde, P. (2022). The essence of democratic backsliding in the European Union: Deliberation and rule of law. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(3), 342–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1855465

- Grabbe, H. 2006. The EU's transformative power. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Greskovits, B. (2015). The hollowing and backsliding of democracy in East Central Europe. Global Policy, 6, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12225

- Gwiazda, A. (2021). Feminist protests, abortion rights and Polish democracy. Femina Politica–Zeitschrift für Feministische Politikwissenschaft, 30(1), 31–32. https://doi.org/10.3224/feminapolitica.v30i1.15

- Habermas, J. (2015). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hanley, S. (2015). East Central Europe: Liberalism gone missing—or just never there? Dr Sean’s Diary. http://seanhanley.org.uk/uncategorized/east-central-europe-liberalism-gone-missing-or-just-never-there/#more-2714.

- Herman, L. (2016). Re-evaluating the post-communist success story: Party elite loyalty, citizen mobilization and the erosion of Hungarian democracy. European Political Science Review, 8(2), 251–284. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773914000472

- Hughes, J., Sasse, G., & Gordon, C. (2004). Conditionality and compliance in the EU's eastward enlargement: Regional policy and the reform of Sub-national government. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 42(3), 523–551. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9886.2004.00517.x

- Inglehart, R. (1971). The silent revolution in Europe: Intergenerational change in post-industrial societies. American Political Science Review, 65(4), 991–1017. https://doi.org/10.2307/1953494

- Klingemann, H. (1999). Mapping political support in the 1990s: A global analysis. In P. Norris (Ed.), Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government (pp. 31–56). Oxford University Press.

- Koopmans, R., & Zurn, M. (2019). Communitarianism and cosmopolitanism: How globalization is reshaping politics in the twenty-first century. In P. De Wilde, R. Koopmans, W. Merkel, O. Strijbis, & M. Zürn (Eds.), The struggle over borders: Cosmopolitanism and communitarianism (pp. 1–34). Cambridge University Press.

- Krastev, I. (2007). Is East-Central Europe backsliding? The strange death of the liberal consensus. Journal of Democracy, 18(4), 56–64.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Dolezal, M., Helbling, M., Höglinger, D., Hutter, S., & Wüest, B. (2012). Political conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (2014). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics. (Vol. 8). Verso Books.

- Levitz, P., & Pop-Eleches, G. (2010). Why no backsliding? The European Union’s impact on democracy and governance before and after accession. Comparative Political Studies, 43(4), 457–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009355266

- Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2007). Generation, age, and time: The dynamics of political learning during Russia's transformation. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 822–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00283.x

- Mouffe, C. (1999). Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism? Social Research, 66(3), 745–758. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40971349

- Müller, J. (2013). Defending democracy within the EU. Journal of Democracy, 24(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2013.0023

- Norris, P. (Ed.) (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government. Oxford University Press.

- Pew Research Center. (2018). Eastern and Western Europeans differ on importance of religion, views of minorities, and key social issues. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/.

- Quaranta, M. (2018). How citizens evaluate democracy: An assessment using the European social survey. European Political Science Review, 10(2), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773917000054

- Rechel, B. (2008). What has limited the EU’s impact on minority rights in accession countries? East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 22(1), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325407311796

- Sartori, G. (2005). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. ECPR press.

- Sasse, G. (2008). The politics of EU conditionality: The norm of minority protection during and beyond EU accession. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(6), 842–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802196580

- Schaffer, F. (2014). Thin descriptions: The limits of survey research on the meaning of democracy. Polity, 46(3), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2014.14

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2007). Strategic calculation and international socialization: Membership incentives, party constellations, and sustained compliance in Central and Eastern Europe. In J. Checkel (Ed.) International institutions and socialization in Europe (pp. 31–62). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511618444

- Schimmelfennig, F., & Sedelmeier, U. (Eds.) (2005). The Europeanization of central and Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press.

- Schimmelfennig, F., & Sedelmeier, U. (2020). The Europeanization of Eastern Europe: The external incentives model revisited. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(6), 814–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1617333

- Schweiger, C. (2023 forthcoming). Migration as a contentious issue in German-ECE relations. Journal of European Public Policy, this issue.

- Sedelmeier, U. (2023 forthcoming). Contradictory east-west divides in the European Union? Democratic backsliding and compliance with EU law. Journal of European Public Policy, this issue.

- Shin, D. (2017). Popular Understanding of Democracy. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-80.

- Shin, D., & Kim, H. (2018). How global citizenries think about democracy: An evaluation and synthesis of recent public opinion research. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 19(2), 222–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109918000063

- Stamatov, P. (2000). The making of a” bad” public: Ethnonational mobilization in post-communist Bulgaria. Theory and Society, 29(4), 549–572. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007060203212

- Szikra, D., & Orenstein, M. (2022). Why Orban won again, Project Syndicate https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/orban-victory-in-hungary-reflects-popular-economic-policies-by-dorottya-szikra-and-mitchell-a-orenstein-2022-04.

- Ulbricht, T. (2018). Perceptions and conceptions of democracy: Applying thick concepts of democracy to reassess desires for democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 51(11), 1387–1440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018758751

- Vachudova, M. (2005). Europe undivided: Democracy, leverage, and integration after communism. Oxford University Press.

- Walzer, M. (1983). Spheres of justice: A defense of pluralism and equality. Basic Books.

- Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising. Cambridge University Press.

- Zagrebina, A. (2020). Concepts of democracy in democratic and nondemocratic countries. International Political Science Review, 41(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118820716