?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

A rise in anti-immigrant pressure can reduce asylum recognition rates, irrespective of individuals’ protection needs. Independent courts, which often act as a safeguard of migrant rights vis-à-vis such pressures, have been subject to increasing political interference. Yet, we know very little about how variation in the level of judicial independence – especially among lower courts – affects policy outcomes. In this paper, we assess the impact of anti-immigrant pressure and judicial independence on first and final instance refugee status determination decisions across 28 European Union member states over a ten-year period (2008–2018). We find that the relative independence of courts makes the biggest difference in asylum recognition rates at first and final instance when levels of anti-immigrant pressure are particularly high. This effect can be demonstrated not just regarding asylum appeals, but also for first instance decisions, suggesting that independent courts can have a liberal ‘foreshadowing effect’ on national asylum agencies.

Introduction

Asylum policies are highly contested and can easily become politicized. Especially in times of strong anti-immigrant sentiment among the public, policymakers come under pressure to respond by adopting more restrictive policies (Hatton, Citation2017). Jennings (Citation2009, p. 847, 865–866) refers to this responsiveness of governments as the ‘public thermostat’, a concept introduced by Wliezen (Citation1995). When under pressure from an anti-immigration public, governments can be expected not only to seek to introduce more restrictive laws, but also to assert a restrictive influence on policy outcomes, such as refugee status determination. In times of high anti-immigrant sentiments, governments can be expected to try and transmit such pressures on those deciding asylum cases, in particular case workers and even judges who hear asylum appeals of first instance decisions.

This paper argues that a strongly independent judiciary can act as a ‘life buoy’ for refugee rights, in particular during times when anti-immigrant pressure is rising. Courts are non-majoritarian institutions, i.e., they are non-elected. Independent judiciaries base their decisions on legal principles rather than voter preferences or public sentiment. By design, the more independent courts are, the more insulated from political pressure one expects them to be. Several studies have shown that non-majoritarian institutions, such as courts, can constitute ‘liberal constraints’ on policymakers and protect minorities (in our case refugees) from majoritarian demands for restrictions (Hollifield, Citation1992; Joppke, Citation2001; Thielemann & Zaun, Citation2018).

Our paper seeks to contribute to this literature, both theoretically and empirically. In terms of theory, we have three expectations regarding the impact of an independent judiciary on refugee status determination. First, we focus on the relative independence of courts, in the expectation that the more independent a court is, the more likely it is to act as a counterweight to the politicization of the asylum process, i.e., the more likely it is to safeguard the rights of refugees (by overturning negative first instance decision and granting protection status to asylum-seekers when reviewing cases on appeal). Second, we expect that the more independent a court is, the more likely it is to produce a ‘liberal foreshadowing’ of first instance decisions taken by asylum agencies, i.e., we expect higher ‘first instance’ recognition rates when asylum officers work within a system of more independent courts, because the case workers can expect independent courts to overturn incorrect decisions of theirs taken in response to political pressure. And third, we expect that it is precisely in times of strong anti-immigrant pressure that the relative independence of a court will matter most in its ability to protect refugees’ rights.

Empirically, the paper also makes an important contribution to the literature on judicial independence more generally. Most of this research has so far focused on the higher courts, particularly in the context of the United States (cf. Burbank et al., Citation1995, p. 7). In contrast, this paper focuses on Europe, and assesses the impact of the independence of the lower courts, as lower courts are responsible for the majority of refugee status appeal decisions. Moreover, while scholars have frequently assessed the impact of political factors with reference to the ideological position of parties in government or the presence of an electorally relevant right-wing populist party, we define anti-immigrant pressure more broadly, which allows us to better account for ‘public thermostat’ dynamics. Finally, unlike most studies on refugee status determination, we distinguish between first instance decision-making (i.e., decisions taken by asylum agencies) and final instance decision-making (i.e., decisions taken by lower courts specializing in asylum cases); this allows for a more fine-grained assessment of causal factors than studies that lump both instances together. Using a fixed-effects OLS regression with panel data on European Union (EU) member states covering the years 2008–2018, we find support for all three of the theoretical expectations outlined above.

The findings of this paper are of particular relevance against the background of recent attacks on the judiciary – not just in Central Eastern Europe (Blauberger & Kelemen, Citation2017; Kovács & Scheppele, Citation2018; Petrov, Citation2021; Przybylski, Citation2018) but also in other countries, where judges and lawyers are sometimes accused of being ‘liberal activists’ who aim to undermine and overturn the policies of democratically elected governments (Elliott, Citation2004; Kmiec, Citation2004). At times, they have even been labelled ‘enemies of the people’ (Breeze, Citation2018). Such attacks on members of the judiciary have been particularly prominent in the area of asylum and immigration (Campbell, Citation2020; Kawar, Citation2015). While some might dismiss them as isolated phenomena in a limited number of countries, this paper demonstrates that, especially when it comes to the lower courts (which receive comparatively little public attention), judicial independence is not static, but derives from the interplay of public governments and judges. It is therefore not surprising that we do see variations in the level of independence of the courts across EU member states, including those states generally characterized as having high-quality institutions. Ultimately, the aim of this paper is to assess the extent to which such variation matters, not least for the fundamental rights of some of the most vulnerable individuals in our societies.

Variance in asylum recognition rates and insulation from political pressures

In the following, we provide an overview over the existing literature that has sought to explain variation in recognition rates. Such studies have focused on factors in refugee sending (e.g., Rosenblum & Salehyan, Citation2004; Teitelbaum, Citation1984) and in destination countries at the macro level (e.g., Holzer & Schneider, Citation2002; Neumayer, Citation2005), and individual characteristics of asylum-seekers at the micro level (Camp Keith & Holmes, Citation2009; Holzer et al., Citation2000, pp. 268–269).

Regarding, factors in destination countries, the existing literature has analyzed a range of socio-economic, political and administrative factors. Evidence in Europe suggests that an increase in asylum applications from a specific country leads to a decrease in recognition rates for applicants from that country (Neumayer, Citation2005), suggesting a trade-off between ‘numbers vs. rights’ (Thielemann & Hobolth, Citation2016; Toshkov, Citation2014; see Jennings (Citation2009) with counter-findings for the United Kingdom). Others have suggested that high levels of economic development and low levels of unemployment can increase recognition rates in Europe (Holzer & Schneider, Citation2002; Neumayer, Citation2005; Toshkov, Citation2014). For the case of Switzerland, Holzer et al. (Citation2000, p. 268) have shown that cantons with either a rather small or large population are associated with higher recognition rates. Moreover, anti-immigrant attitudes among voters and a larger foreign-born population result in lower recognition rates (Holzer et al., Citation2000). Politically, a left-leaning government in power for a long period of time and low levels of electoral support for right-wing populist parties are associated with higher recognition rates, both in Germany and in the EU as a whole (Schneider et al., Citation2020; Winn, Citation2021).

Some studies have analyzed the role of courts and asylum agencies on refugee status determination procedures using both qualitative and quantitative methods, with a focus on the US in particular (Camp Keith et al., Citation2013; Ramji-Nogales et al., Citation2011; Rottman et al., Citation2009). Hamlin (Citation2012, Citation2014) addresses the role of insulation from political pressures, focussing on the different setups of refugee status determination institutions in the US, Canada, and Australia.

However, there have been few large-N studies on the variation in the level of judicial independence and anti-immigrant pressures within countries over time. An exception is Spirig (Citation2021), who showed in the case of Switzerland that increases in the salience of immigration led to decreases in asylum recognition rates at the appeal stage. Spirig argues that immigration salience is a good proxy for anti-immigration attitudes in the population. While this may be true for Switzerland, salience and anti-immigration attitudes do not need to correlate at all (see figure SM1 in the supplementary materials). In some member states, increases in salience even coincide with increases in pro-immigrant attitudes, and indeed, refugee crises do not automatically entail an anti-immigrant backlash as the ongoing Ukrainian refugee crisis would seem to indicate.

Theorizing on the impact of anti-immigrant pressure and judicial independence on asylum recognition rates

This section of the paper seeks to theorize about the impact that anti-immigrant pressure and judicial independence have on asylum recognition rates. We start from the assumption that there are two instances of the decision-making process that can be affected by these factors: at first instance, decisions are taken by a delegated agency within the national bureaucracy; at second and final instance, decisions are taken by lower courts.Footnote1

Anti-immigrant pressure

A mere focus on partisan politics and government composition would suggest that anti-immigrant pressure only affects policymaking when a party holding such views, i.e., usually a right-wing populist or conservative party, is in power or holds a significant electoral share. This is at odds with those findings that indicate that left-leaning parties adopt restrictive positions and policies on immigration. Alonso and Claro da Fonseca (Citation2012) have shown that the manifestos of all parties across Europe, except those of the Greens, take up anti-immigrant positions. This includes Socialist and Social Democratic parties – whose electorates are split on this issue. Also outside Europe, consecutive Labour governments in Australia have adopted highly restrictive asylum policies (Crock, Citation2009). The adoption of the German Asylkompromiss in 1992 is a case in point, highlighting that anti-immigrant pressure can have an impact without the vehicle of partisan politics. This policy ended Germany’s track-record as one of the most liberal asylum countries at the time. As the law required a change in the German Constitution, it could only be adopted with the support of the Social Democrats who at the time were in opposition (cf. Minkenberg, Citation1998; Thränhardt & Miles, Citation1995). At that time in Germany, there was no electorally relevant right-wing party at the national level that was able to pass the 5 per cent vote-share threshold needed to be represented in the national parliament (Koopmans, Citation1996, p. 198; Koopmans & Statham, Citation1999, pp. 36–37), yet public attitudes were highly anti-immigrant in Germany. According to opinion polls from 1984 and 1998, more than 70 per cent of Germans felt that too many migrants lived in Germany (Abalı, Citation2009, p. 3). This suggests that anti-immigrant attitudes can affect policies at times other than at elections.

To theorize on the impact of anti-immigrant pressure outside electoral cycles, we draw on a conceptualization introduced by Hatton (Citation2017), who suggested that it has two dimensions: salience and preference. If migration is a salient topic but the public holds no clear preference for or against restrictive policies, salience does not exert any pressure. Indeed, Salehyan and Rosenblum (Citation2008) found that an increase in the salience of asylum policy explains changes in recognition rates. However, they were unable to make any precise statements on the directionality of these changes, arguably because they disregarded the dimension of preference. Likewise, strong anti-immigration preferences do not lead to pressure if the issue is not politically salient.

Four different causal mechanisms can account for the impact of anti-immigrant pressure on refugee status determination decisions. First, case workers and judges may simply change their own substantive positions, i.e., they may adopt a more restrictive attitude when society at large does so (Spirig, Citation2021, p. 13). Second, asylum agency case workers and asylum judges may feel pressured by a change towards a more securitized discourse on asylum in society at large. Here, a wish not to be considered out of touch with wider societal preferences might play an important role. Johannesson (Citation2018) found some support for the effect of societal pressure on asylum judges. She argues that, in Sweden, public and political discourse used to be quite strongly pro-refugee which put pressure on asylum judges to decide in a refugee’s favour.Footnote2 Third, the legislator can respond to anti-immigration pressure by tightening the asylum laws on which asylum determination decisions are based. Scheppele (Citation2002) suggests that executives can promote laws or issues guidelines that severely limits judges’ discretion and room to manoeuvre, largely depriving them of the ability to be ‘the authors of their own decisions’. (Informal) guidelines that can potentially restrict the room of manoeuvre of courts include safe country of origin lists which pre-define certain countries as safe, hence disqualifying any applications from nationals of that country as manifestly unfounded (Engelmann, Citation2014).

Finally, governments can respond to anti-immigrant pressure from the public by indirectly (and sometimes more directly, see Clark, Citation2011, p. 7) by pressuring case workers and judges to take a more restrictive stance. Examples of this fourth mechanism include the Australian government pressuring courts to restrict Chinese boat refugees (Crock, Citation2009), and Greek asylum officers coming under pressure for granting asylum to a claimant the government considered eligible for return under the EU-Turkey deal (Angelidis, Citation2016).

HYPOTHESIS 1: The stronger anti-immigrant pressure, the lower the asylum recognition rates.

Judicial independence

In this paper, we are specifically interested in the impact of judicial independence in asylum decision-making at first instance and final instance. According to Ríos-Figueroa and Staton (Citation2014, p. 107), autonomy is a key feature of judicial independence. Autonomy requires judges to be the ‘authors of their own decisions’ (Kornhauser, Citation2002, p. 48). In other words, autonomy refers to the court’s ability to take impartial and reasoned decisions based on the text and telos of the law, without undueFootnote3 interference from other actors – in our case, the executive. Independent courts are meant to act autonomously and ignore political concerns.

This is not the case for asylum agencies which are charged with taking first instance decisions on asylum applications. They are subordinate to ministries which themselves are subject to the political leadership provided by the elected government. As part of the executive, ministries, and by extension asylum agencies as well, are more likely to respond to public attitudes and voter preferences. In fact, in majoritarian democratic systems this is even expected.

In an asylum system where the judiciary is less autonomous, the executive may respond to anti-immigrant pressure from the public by seeking to transmit such pressures not just to first instance decision-makers but also the courts as part of the wider asylum system as well. In an environment of limited judicial independence, judges may feel a latent pressure to adopt restrictive decisions on asylum cases if they fear that doing otherwise might affect their career or the court’s finances (Vanberg, Citation2000). In such a system, high anti-immigrant pressure may therefore translate into lower recognition rates by the courts (Barry, Citation1995, p. 103). On the other hand, in a system that values judicial independence, the executive is less likely to attempt any direct or indirect interference into the judicial process and courts are more likely resist pressures that might challenge their independence (Vanberg, Citation2000, p. 346; Citation2015, p. 177). Overall, this suggests that judicial independence is sustained through the conduct of judges who resit undue interference into their work, and the conduct of members of the executive who refrain from interfering. Where this is the case, the courts are in a stronger position to decide cases impartially, focusing on the merits of a case which can be expected to result in more successful asylum appeals and higher overall recognition rates.

HYPOTHESIS 2a: The greater the independence of the courts, the higher the recognition rates at the final instance.

HYPOTHESIS 2b: The effect created by the relative independence of courts is moderated by anti-immigrant pressure, i.e., the larger the anti-immigrant pressure, the greater the difference the independence of the courts makes in last instance decisions.

HYPOTHESIS 3a: The more independent the courts, the higher the first instance recognition rates.

HYPOTHESIS 3b: The effect created by the relative independence of courts is moderated by anti-immigrant pressure, i.e., the larger anti-immigrant pressure, the greater the difference the independence of courts makes in first instance decisions.

Data and estimation model

Data

Anti-immigration pressure

We operationalize anti-immigrant pressure in line with Hatton (Citation2017) as a combination of anti-immigrant preferences and the salience of immigration as a politically important topic. Data on preferences is provided by the European Social Survey (ESS) (European Social Survey, Citation2016, Citation2018), three questions of which relate directly to preferences concerning the number of immigrants the respondents would like to see in their country: (1) To what extent do you think [country] should allow people of the same ethnic group as most [country] people to come and live here? (many/some/a few/none); (2) How about people of a different race or ethnic group from most [country] people? (many/some/a few/none); (3) How about people from the poorer countries outside Europe? (many/some/a few/none).

First, for each response we calculated a dichotomous variable, taking the value 1 if the response was ‘a few’ or ‘none’, and ‘0’ otherwise. We then calculated the average of this dichotomous variable over all responses per country and wave, which can be interpreted as the share of respondents who were relatively opposed to immigrants. In the last step, we calculated the average of all three question-related averages per country and wave.

To operationalize salience, we use the responses to one question asked in the Eurobarometer survey (European Commission, Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2012c, Citation2012d, Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020): What do you think are the two most important issues facing (OUR COUNTRY) at the moment? Respondents were provided with a list of 14 possible options, of which immigration was one. Alternatively, respondents could name additional options not provided in the list. Eurobarometer publishes the share of respondents naming immigration as one of the two most important issues.

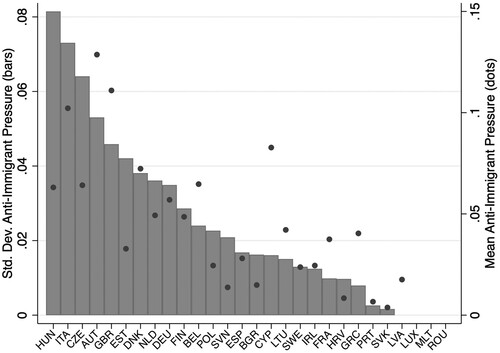

The ESS spans two years, e.g., 2002 is in fact 2002/2003. To relate these responses to those reported in Eurobarometer, we combined the responses of the autumn round of the Eurobarometer with the spring round of the following year. Our measure of anti-immigrant pressure, is the product of anti-immigrant preferences and the salience of immigration as politically important. This measure differs considerably by country, as illustrated by the bars in .Footnote5 Hungary and Italy, for instance, show high variation of anti-immigrant pressure in our data set, while other countries such as Portugal or Slovakia show only a marginal variation in anti-immigrant pressure. For Luxembourg, Malta and Romania, we did not have sufficient data to calculate anti-immigrant pressure. The variance in anti-immigrant pressure also positively correlates with its average level per country, shown as dots in .

Judicial independence

Scholars researching judicial independence usually distinguish two types of judicial independence, de jure and de facto. De jure independence refers to the formal rules that are expected to promote judges’ independence, such as life tenure and merit-based rather than political appointment (Clark, Citation2011, pp. 9–21). Research on the impact of de jure judicial independence has been inconclusive, and existing measures have been found to measure different phenomena (Ríos-Figueroa & Staton, Citation2014, p. 105). De facto judicial independence, in contrast, is a behavioural measure of how independent everyday adjudication is from government or other intervention (Ríos-Figueroa & Staton, Citation2014, p. 105).

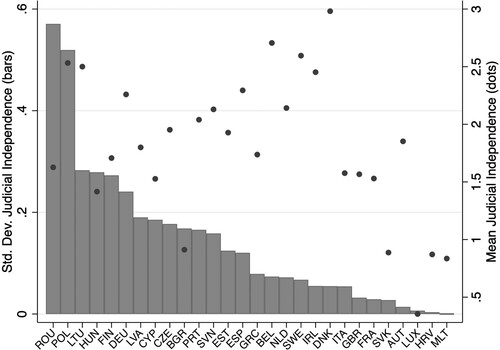

As we were interested in the effect of political intervention in de facto administrative and/or judicial procedures, we needed a de facto measure of judicial independence. Further, because judicial rulings in asylum cases are typically made by the lower courts, we needed a measure that focuses on these.Footnote6 We used the only existing measure that satisfies both criteria – the measure of lower court judicial independence provided by ‘The Varieties of Democracy Project’ (Coppedge et al., Citation2020a), which is based on surveys conducted among country experts. It is based on the following question: When judges not on the high court are ruling in cases that are salient to the government, how often would you say that their decisions merely reflect government wishes regardless of their sincere view of the legal record? (always/usually/about half of the time/seldom/never). The answers were re-scaled by V-Dem to take values from −5 (low judicial independence) to +5 (high judicial independence), with 0 approximately representing the mean for all country-years in the sample (Coppedge et al., Citation2020b, p. 30). The bars in depict the standard deviation of our measure of judicial independence by country. While Romania and Poland show the largest variances by far, all countries, except for Malta, show at least some degree of variation. Unlike the case of anti-immigration pressure, here there is no correlation between the variation in judicial independence and its average level by country, shown as dots in .

Since our aim is to statistically analyze the effect of anti-immigrant pressure and judicial independence on recognition rates, we need to consider a battery of variables that have been shown to affect these. We follow the most encompassing study to date in this regard, namely Neumayer (Citation2005), and include various macro-level factors, both at the level of destination country and country of origin. The destination country variables include: the average number of total asylum applications in the previous 2–5 years; the average number of asylum applications from country o in the previous 2–5 years; the natural log of GDP per capita in 2010 USD (World Bank, Citation2020); the unemployment rate (World Bank, Citation2020); and the share of right-wing parties in nation-wide legislative elections (from the Database on Political Institutions for 2002–2017: Scartascini et al., Citation2018; for 2018: Kollman et al., Citation2020). The country of origin variables comprise: the natural log of GDP per capita in 2010 USD (World Bank, Citation2020)Footnote7; the unweighted sum of the Political Rights and Civil Liberties Index (Freedom House, Citation2020) as a measure of autocracy; the unweighted mean of the two Political Terror Scales, one based on Amnesty International information, one on the US State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices (Gibney et al., Citation2019); threats to personal integrity stemming from events of civil and ethnic wars and the collapse of state authority, measured by the maximum of magnitude scores (0–4 scale) as coded for such events by the US State Failure Task Force Project (Marshall et al., Citation2019); annual deaths from genocide and politicide (Marshall et al., Citation2019); and the extent of external armed conflict, based on data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Project (Pettersson et al., Citation2020). Our dependent variables, i.e., asylum recognition rates at first and final instance, are taken from Eurostat (Eurostat, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Note that this data includes decisions on all applications for international protection, regardless of the specific status granted. Moreover, this dataset only covers administrative decisions and decisions of lower courts, i.e., it disregards exceptional cases where decisions were passed on to higher courts. As Eurostat has distinguished between first and final instance outcomes only since 2008, our analysis covers the years 2008–2018. We provide summary statistics for all the variables used in our analyses in the supplementary materials.

Estimation model

Countries differ in many ways for which we cannot explicitly control, most importantly in the restrictiveness of their asylum law.Footnote8 For instance, a country that systematically has more restrictive asylum laws in place or a generally more restrictive approach to the implementation of common EU laws, can be expected to have lower recognition rates even if its judiciary is more independent than that of other states. Consequently, a comparative analysis runs the risk of conflating the effects of judicial independence with other factors. A fixed-effects within analysis, on the other hand, allows us to control for country-specific effects and identify the causal effect of judicial independence. Technically, for each combination of destination d, origin o and year t, we estimate the influence of a variety of factors on recognition rates at first and final instance levels. Eurostat (Citation2020a, Citation2020b) provides data on positive (acceptances) and negative (rejections) asylum decisions per country-year, from which we calculated the respective recognition rates. For each level, we used the following model:

(1)

(1) where ydot corresponds to the recognition rates at first or final instance. The vector X contains the explanatory variables (see above), αdo represents our unit-specific fixed effects, υt represents time-fixed effects (dummy variables for each year), and ϵdot the error term.

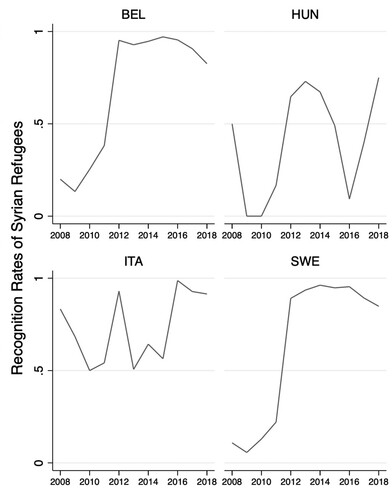

Combinations of destination, origin and year where no decisions are made afford no decision by the destination country. We therefore excluded observations where no first or final instance decisions were made.Footnote9 To illustrate the variance in recognition rates, even for applicants from the same country of origin, gives an overview of the total recognition rates of Syrians in selected European countries. Syrian asylum-seekers’ ‘deservingness’ of protection is little contested since 2011 (Smith & Waite, Citation2019). However, there is a clear variance in recognition rates, both longitudinally and cross-sectionally. Belgian and Swedish recognition of Syrians is usually high but has decreased marginally in recent years. Hungary and Italy, on the other hand, have seen dramatic swings in their recognition of Syrian refugees over time.Footnote10

Results

Before estimating our main models, we replicated the analysis of Neumayer (Citation2005) using our own data set. The results are documented in the supplementary materials. In essence, we support many of his main findings. For instance, we found that the number of past applications from a specific country of origin have a significant negative effect on the recognition rates of applications from that country. However, when we distinguished between first and final instance decisions, which Neumayer’s original analysis did not do, we found that this effect is mainly driven by first instance decisions and is statistically insignificant at the final instance. It therefore makes a difference for the effects whether first or final instance are affected, which is why we separate our analysis accordingly.

Final instance results

We assessed the impact of anti-immigrant pressure (HYPOTHESIS 1) and judicial independence (HYPOTHESIS 2a) by adding these variables, as defined above, to the model proposed by Neumayer. shows the results for final instance decisions.Footnote11 Column (1) depicts the results from the regression, including only judicial independence, column (2) those including only anti-immigrant pressure, and column (3) those when including both judicial independence and anti-immigrant pressure. To account for the possibility of a mediating effect between judicial independence and anti-immigrant pressure (HYPOTHESES 2b and 3b), in a further step we included an interaction term of the two. The results are depicted in column (4). As the inclusion of both variables and their interaction complicates the interpretation of the overall effect sizes of each variable, in column (5) we also report the marginal effects of anti-immigrant pressure and judicial independence. These combine the ‘direct effects’ of the two variables, measured via their immediate coefficients, and the indirect effect via the interaction term. Slightly simplified, the marginal effects can be interpreted similarly to the coefficients of regressions without the interaction term, i.e., as an effect of a change in one variable, holding all other variables constant at their average values.Footnote12

Table 1. Final instance.

We found statistically significant effects of both anti-immigrant pressure (HYPOTHESIS 1) and judicial independence (HYPOTHESIS 2a), as shown in (the complete regression output can be found in the supplementary materials). The effects are relatively stable across the different model specifications. We also found a positive and significant interaction effect between judicial independence and anti-immigrant pressure (HYPOTHESIS 2b), as can be seen from column (4). The positive and significant marginal effect of judicial independence (column 5) implies that, at an average level of anti-immigrant pressure, an increase in judicial independence by one standard deviation leads to an increase in the final recognition rate of approximately 3 percentage points. Given that the average final recognition rate in our data set is 0.2, this corresponds to an increase of 15 per cent. Similarly, the results imply that an increase in anti-immigrant pressure by one standard deviation reduces the recognition rate by 2 percentage points, which corresponds to a decrease of 10 per cent. In additional analyses, which we document in the supplementary materials, we also found that the higher the anti-immigrant pressure, the larger the marginal impact of judicial independence. This implies that judicial independence serves as a mediator in times of high anti-immigrant pressure.

Earlier findings had suggested that a subconscious hardening of judges’ attitudes rather than strategic considerations would explain lower asylum recognition rates in times of high levels of anti-immigrant sentiment among the public (Spirig, Citation2021, p. 13). Our findings, however, suggest that lower recognition rates cannot be explained only by such subconscious processes, but that judges also respond to external pressures. We initially posited that more restrictive adjudication could theoretically be due to either government influence or public pressure. The operationalization of judicial independence in our analysis as independence from government influence provides evidence of an indirect effect of anti-immigrant pressure via the government.

We document a range of robustness tests in the supplementary materials. Specifically, we show in those tests that the results hold even if we exclude the years 2015 and 2016, which saw a particular rise in asylum applications, or if we exclude the different states that have joined the EU since 2004, or countries having a coastline with the Mediterranean Sea, which are easier for asylum-seekers from the Middle East or Africa to reach. We also found that the results remain largely unchanged if we include first instance recognition rates from up to two years before the respective final instance recognition rate. However, when including only the same and the previous period’s first instance recognition rate, the effect decreases in absolute value and becomes insignificant. The marginal effect of judicial independence remains marginally significant. This suggests that the effects of judicial independence and anti-immigrant pressure on final instance recognition rates are at least partially ‘filtered’ by the decisions taken at the first instance.Footnote13 Given the somewhat limited variation in our main variable of interest – judicial independence – we also checked how likely it is that any effects measured might be the outcome of a random process, by using randomized inference. The results suggest that this is not the case (see supplementary materials).

First instance results

Replicating the analysis for first instance decisions, we found that the coefficients, documented in , were as expected: consistent with HYPOTHESIS 1, we found that anti-immigrant pressure negatively affects recognition rates, while judicial independence affects them positively, which is consistent with HYPOTHESIS 3a. For average levels of anti-immigrant pressure, an increase in judicial independence by one standard deviation leads to an increase in the first instance recognition rate of 3.5 percentage points. Given the average recognition rate of 0.22 at the first instance, this corresponds to an increase of about 16 per cent. An increase in anti-immigrant pressure by one standard deviation leads to a decrease in the first instance recognition rate of 2.25 percentage points, or a decrease of 10 per cent. As we argued in the case of final instance decisions, this implies that judicial independence has a ‘foreshadowing effect’ on first instance decisions that partly offsets the restrictiveness induced by anti-immigrant pressure (supporting HYPOTHESIS 3b). Again, we find that the higher anti-immigrant pressure, the larger the marginal impact of judicial independence (see the supplementary materials).

Table 2. First instance.

Again, the supplementary materials contain a series of robustness checks excluding observations from 2015 and 2016, new member states, countries with a Mediterranean coastline, and randomized inference. It should be noted, however, that in contrast to the case of final instance recognition rates, the effect of judicial independence on first instance recognition rates crucially depended on the inclusion of those member states that joined the EU in or after 2004. However, we found no meaningful subset of new member states, such as the Visegrad 4 or Central Easter European member states, which by itself triggered a loss of significance, and therefore conclude that the foreshadowing effect is in large part statistically driven by the entire set of ‘new’ member states.

Overall, the empirical results confirm most of our hypotheses: Stronger anti-immigrant pressure decreases asylum recognition rates at both the first and final instances (HYPOTHESIS 1). Independent courts, on the other hand, show a positive impact on both final (HYPOTHEIS 2a) and first instance (HYPOTHESIS 3a) recognition rates. Independent courts further moderate the negative effects of anti-immigrant pressure both at the appeal stage (HYPOTHESIS 2b) and at first instance (HYPOTHESIS 3b). This last observation supports our argument of a ‘liberal foreshadowing’ effect of an independent judiciary, and underlines that the shielding effect of independent courts is especially important when anti-immigrant pressure is high.

Conclusion

We set out to examine the extent to which an independent judiciary can act as a life buoy for refugee rights when the tide of anti-immigrant pressure is high. In particular, we sought to assess whether differences in the level of judicial independence could be shown to have a significant effect on refugee status determination outcomes. We built our investigation on existing research that has demonstrated different ways in which courts, judges and legal systems can influence refugee status determination (Camp Keith et al., Citation2013; Hamlin, Citation2012, Citation2014; Ramji-Nogales et al., Citation2011), complementing these studies through a large-N study of the impact of variations in the relative independence of courts on refugee recognition outcomes.

Our findings demonstrate that anti-immigrant pressure leads to lower asylum recognition rates at both the first and final instance decision-making stages of the asylum process, even when we control for other factors (including the protection needs of applicants). This suggests that neither asylum officers nor judges are immune to such pressure. While existing research has focused on the role of conservative parties in government or successful far-right challenger parties, we have shown that anti-immigrant pressure reduces asylum recognition rates apart from these party dynamics.

We then went on to show that the presence of courts that are relatively independent from government interference shields refugees from anti-immigrant sentiments, in two ways. Directly, by overturning – on appeal – decisions on asylum applications wrongfully rejected at the first instance (more independent courts overturn more decisions). More surprisingly, we also found empirical support for an indirect ‘judicial foreshadowing’ effect. It seems that the more independent the courts are, the less likely it is that first instance decision-makers will succumb to anti-immigration sentiment or pressure for tighter restrictions. Greater judicial independence appears to create an environment in which de-politicized decision-making is valued more highly, including at the first instance stage of the asylum process. Finally, the data analyzed here also support the claim that the effect of judicial independence is strongest when anti-immigration pressure is particularly high.

Overall, our findings suggest that, in the context of higher levels of judicial independence, asylum decisions are less likely to be influenced by political pressure and more likely to be determined by legal norms and fundamental human rights considerations. The flipside of this is that when judicial independence is under attack and more limited, this can be expected to have serious implications for refugees who, as consequence of wrongful decisions, may have to pay the price of refoulement, i.e., being sent back to a place where they could face persecution or degrading treatment.

Our findings have important implications at a time when many countries are experiencing some of the largest refugee inflows in their history and anti-immigration pressure is on the rise.Footnote14 At the very same time, judicial independence has come under populist attacks and the roles of judges and lawyers have been challenged – not just in Central Eastern Europe (Kovács & Scheppele, Citation2018; Petrov, Citation2021) and post-Brexit Britain (Breeze, Citation2018), but also more generally (Lacey, Citation2019; Prendergast Citation2019). While the cases of Poland and Hungary have attracted most of the attention in this context, this paper has demonstrated that levels of judicial independence – especially those of lower courts – fluctuate in other member states as well, which is a useful reminder that a country’s judicial independence is not a given, but something that must be cultivated and sustained through the daily actions of both judges and members of government. When the government tries to influence court decisions, or when the courts are unwilling or unable to resist political pressure, judicial independence declines. Our analysis has shown that even small fluctuations in the level of independence in the lower courts of member states, where such issues are less of a concern for the public but also in academic debates yet, can have tangible effects on the protection of fundamental rights of asylum-seekers and refugees. This paper can therefore serve as a timely reminder of the crucial role the courts play in protecting minority rights, particularly during times of heightened populism and anti-immigrant sentiment. It also reminds us that judicial independence and the rule of law cannot be taken for granted.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (806.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of the Europe@LSE seminar series and especially Vassilis Monastiriotis, the participants of the workshop on ‘New dynamics in migration policies’ at the University of Mainz and the participants of the DeZIM/WZB workshop on ‘Recognising refugees’ for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this paper. Moreover, we would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. All remaining errors are ours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Natascha Zaun

Natascha Zaun is Associate Professor in Migration Studies at the European Institute at the LSE.

Martin Leroch

Martin Leroch is Professor of Economics at the Faculty of Business and Law at Pforzheim University.

Eiko Thielemann

Eiko Thielemann is Associate Professor in Public Policy at the European Institute and the Department of Government at the LSE.

Notes

1 It is usually only in the case of serious procedural flaws can rejected asylum-seekers challenge their second instance decision at a higher court in third instance. In the case of severe human rights violations, some EU member states allow a review at their highest national court, usually a constitutional court (AIDA, Citation2020).

2 Sweden is certainly an outlier and scholars have shown that majoritarian dynamics usually are to the detriment of refugees and migrants who cannot vote (Barry, Citation1995, p. 103).

3 There are forms of interference, such as amicus curiae briefs, which are foreseen under the law.

4 In Germany, the Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge responded to an increased inflow by hiring new case workers and more than tripling its staff from 3,000 to 10,000 (Bayrischer Rundfunk, Citation2020). The newly-hired staff often had no relevant experience and were poorly trained, to the detriment of many asylum decisions: 35% of rejection decisions were overturned by the courts in 2018. This provoked heavy criticism of the work of the BAMF and parliamentary questions in the Bundestag.

5 We document the evolution of anti-immigration pressure per country over time in the supplementary materials.

6 The independence of higher and lower courts is not necessarily correlated, as the reasons for and consequences of undermining the independence of the higher and lower courts differ significantly. For instance, it has been shown that lower courts tend to be under attack much more often than higher courts (Fiss, Citation1993, p. 63), and arguably higher courts benefit from stronger public support. Encroaching on their independence is therefore considered more ‘costly’ for governments. On the other hand, actors that are seeking to make a big impact on the constitutional setup of a country tend to focus on the higher courts; having little interest in the lower courts, they leave them alone (Fiss, Citation1993, pp. 68–69).

7 The World Bank does not publish GDP per capita data in 2010 USD on Syria, so we used the corresponding estimates from the CIA World Factbook.

8 Datasets that measure the openness/restrictiveness of asylum laws such as DEMIG (DEMIG, Citation2015) or IMPIC (Helbling et al., Citation2017) do not cover our timeframe.

9 We chose additive conditions to avoid differences in the coefficients arising from different samples when comparing regressions on first or final instance decisions.

10 Approval rates are calculated as approval at both the first and final instance, divided by overall decisions in the first instance. For Sweden, this measure exceeds 1 for some years, because some cases at the final instance are pushed to the following year.

11 To facilitate a comparison of coefficients, in our statistical analysis we used standardized versions of these variables, which have a mean value of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

12 Strictly speaking, our way of calculating the marginal effect of judicial independence (or anti-immigration pressure) additionally assumes that the coefficient of anti-immigration pressure (or judicial independence) is held constant at its average level.

13 As we note in the supplementary materials, this loss in significance is mainly driven by 2 observations: Afghan applicants to the Czech Republic in 2014, and Vietnamese applicants to Poland in 2010. When excluding these observations, the coefficient of judicial independence is marginally significant.

14 Please note that the inflow of Ukranian refugees since 2022 is not part of this analysis, given our timeframe of analysis and the fact that these are currently not undergoing refugee status determination procedures but are protected under the EU’s Temporary Protection Directive.

References

- Abalı, O. S. (2009). German public opinion on immigration and integration. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/TCM-GermanPublicOpinion.pdf

- AIDA. (2020). Asylum authorities. An overview of internal structures and available resources. https://asylumineurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/aida_asylum_authorities_0.pdf

- Alonso, S., & Claro da Fonseca, S. (2012). Immigration, left and right. Party Politics, 18(6), 865–884. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810393265

- Angelidis, D. (2016). Erotimata gia tin apofasi gia paradekto aitima asyloy. https://www.efsyn.gr/ellada/dikaiomata/69592_erotimata-gia-tin-apofasi-gia-paradekto-aitima-asyloy

- Barry, B. (1995). Justice as impartiality. Oxford University Press.

- Bayrischer Rundfunk. (2020). “Wir schaffen das” und die Folgen für das BAMF. https://www.br.de/nachrichten/bayern/wir-schaffen-das-und-die-folgen-fuers-bamf,S9F0rrD

- Blauberger, M., & Kelemen, R. D. (2017). Can courts rescue national democracy? Judicial safeguards against democratic backsliding in the EU. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1229357

- Breeze, R. (2018). “Enemies of the people”: populist performances in The Daily Mail reporting of the article 50 case. Discourse, Context & Media, 25, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2018.03.008

- Burbank, S. B., Friedman, B., & Goldberg, D. (1995). Reconsidering judicial independence. In S. B. Burbank & B. Friedman (Eds.), Judicial independence at the crossroads (pp. 3–42). Sage.

- Campbell, J. R. (2020). The role of lawyers, judges, country experts and officials in British asylum and immigration law. International Journal of Law in Context, 16(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552320000038

- Camp Keith, L., & Holmes, J. S. (2009). A rare examination of typically unobservable factors in US asylum decisions. Journal of Refugee Studies, 22(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fep008

- Camp Keith, L., Holmes, J. S., & Miller, B. P. (2013). Explaining the divergence in asylum grant rates among immigration judges: An attitudinal and cognitive approach. Law & Policy, 35(4), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/lapo.12008

- Clark, T. S. (2011). The limits of judicial independence. Cambridge University Press.

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, M. S., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Lührmann, A., Marquardt, K. L., McMann, K., Paxton, P., Pemstein, D., Seim, B., Sigman, R., Skaaning, S. E., Staton, J., … Ziblatt, D. (2020a). V-Dem dataset v10” varieties of democracy (V-Dem) project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, M. S., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Lührmann, A., Marquardt, K. L., McMann, K., Paxton, P., Pemstein, D., Seim, B., Sigman, R., Skaaning, S. E., Staton, J., … Ziblatt, D. (2020b). V-Dem codebook v10 varieties of democracy (V-Dem). https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/28/14/28140582-43d6-4940-948f-a2df84a31893/v-dem_codebook_v10.pdf

- Crock, M. (2009). Judging refugees: The clash of power and institutions in the development of Australian refugee law. Sidney Law Review, 61(9), 51–73.

- DEMIG. (2015). DEMIC POLICY. version 1.3, Online Edition. Oxford: International Migration Institute. University of Oxford, https://www.migrationdeterminants.eu

- ECRE. (2019, April 5). Germany: Data on decision-making reveals BAMF short-comings. https://www.ecre.org/germany-data-on-decision-making-reveals-bamf-shortcomings/

- Elliott, R. D. (2004). Judicial activism and the threat to democracy. UNBLJ, 53, 199.

- Engelmann, C. (2014). Convergence against the odds: The development of safe country of origin policies in EU member states (1990–2013). European Journal of Migration and Law, 16(2), 277–302. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718166-12342056

- European Commission. (2012a). Eurobarometer 57.2OVR (Apr-Jun 2002). European Opinion Research Group (EORG), Brussels. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA3641 Data file Version 1.0.1. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.10951

- European Commission. (2012b). Eurobarometer 62.0 (Oct-Nov 2004). TNS OPINION & SOCIAL, Brussels [Producer]. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA4229 Data file Version 1.1.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.10962

- European Commission. (2012c). Eurobarometer 66.2 (Oct-Nov 2006). TNS OPINION & SOCIAL, Brussels [Producer]. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA4527 Data file Version 1.0.1. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.10981

- European Commission. (2012d). Eurobarometer 70.1 (Oct-Nov 2008). TNS OPINION & SOCIAL, Brussels [Producer]. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA4819 Data file Version 3.0.2. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.10989

- European Commission. (2013). Eurobarometer 74.2 (2010). TNS OPINION & SOCIAL, Brussels [Producer]. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5449 Data file Version 2.2.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.11626

- European Commission. (2015). Eurobarometer 78.1 (2012). TNS opinion, Brussels [producer]. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5685 Data file Version 2.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12061

- European Commission. (2018). Eurobarometer 82.3 (2014). TNS opinion, Brussels [producer]. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5932 Data file Version 3.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13021

- European Commission. (2019). Eurobarometer 90.3 (2018). Kantar Public [producer]. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7489 Data file Version 1.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13254

- European Commission. (2020). Eurobarometer 86.2 (2016). TNS opinion, Brussels [producer]. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA6788 Data file Version 1.5.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13467

- European Social Survey. (2016). Cumulative File. ESS 1-8. Data file edition 1.0. NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC

- European Social Survey. (2018). Round 9 data. Data file edition 2.0. NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS9-2018

- Eurostat. (2020a). First instance decisions on asylum applications by type of decision – annual data (tps00192). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00192/default/table?lang=en

- Eurostat. (2020b). Final decisions on asylum applications – annual data (tps00193). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00193/default/table?lang=en

- Fiss, O. M. (1993). The limits of judicial independence. University of Miami Inter-American Law Review, 25(1), 57–76.

- Freedom House. (2020). Freedom in the world.

- Gibney, M., Cornett, L., Wood, R., Haschke, P., Arnon, D., & Pisanò, A. (2019). The political terror scale 1976-2018. http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/

- Hamlin, R. (2012). International law and administrative insulation: A comparison of refugee status determination regimes in the United States, Canada, and Australia. Law & Social Inquiry, 37(4), 933–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.2012.01292.x

- Hamlin, R. (2014). Let me be a refugee: Administrative justice and the politics of asylum in the United States, Canada, and Australia. Oxford University Press.

- Hatton, T. J. (2017). Public opinion on immigration in Europe: Preference versus salience. Centre of Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper 12084.

- Helbling, M., Bjerre, L., Römer, F., & Zobel, M. (2017). Measuring immigration policies: The IMPIC database. European Political Science, 16(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2016.4

- Hollifield, J. (1992). Immigrants, markets and states: The political economy of post-war Europe. Harvard University Press.

- Holzer, T., & Schneider, G. (2002). Asylpolitik auf Abwegen: Nationalstaatliche und europäische Reaktionen auf die Globalisierung der Flüchtlingsströme. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Holzer, T., Schneider, G., & Widmer, T. (2000). Discriminating decentralization: Federalism and the handling of asylum applications in Switzerland, 1988-1996. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 44(2), 250–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002700044002005

- Jennings, W. (2009). The public thermostat, political responsiveness and error-correction: Border control and asylum in Britain, 1994-2007. British Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 847–870. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712340900074X

- Johannesson, L. (2018). Exploring the “Liberal Paradox” from the inside: Evidence from the Swedish Migration Courts. International Migration Review, 52(4), 1162–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318767928

- Joppke, C. (2001). The legal-domestic sources of immigrants rights: The United States, Germany and the European Union. Comparative Political Studies, 34(4), 339–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414001034004001

- Kawar, L. (2015). Contesting immigration policy in court: Legal activism and its radiating effects in the United States and France. Cambridge University Press.

- Kmiec, K. D. (2004). The origin and current meanings of ‘judicial activism’. California Law Review, 92(5), 1441–1477. https://doi.org/10.2307/3481421

- Kollman, K., Hicken, A., Caramani, D., Backer, D., & Lublin, D. (2020). Constituency-Level Elections Archive (CLEA), https://www.electiondataarchive.org/data-and-documentation.php

- Koopmans, R. (1996). Explaining the rise of racist and extreme right violence in Western Europe: grievances or opportunities? European Journal of Political Research, 30(2), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1996.tb00674.x

- Koopmans, R., & Statham, P. (1999). ‘Ethnic and civic conceptions of nationhood and the differential success of the extreme right in Germany and Italy’. In M. G. Giugni, D. McAdam, & C. Tilly (Eds.), How social movements matter (pp. 225–251). University of Minnesota Press.

- Kornhauser, L. A. (2002). ‘Is judicial independence a useful concept?’. In S. B. Burbank, & B. Friedman (Eds.), Judicial independence at the crossroads. An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 45–55). Sage.

- Kovács, K., & Scheppele, K. L. (2018). The fragility of an independent judiciary: Lessons from Hungary and Poland—and the European Union. Communist and Postcommunist Studies, 51(3), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2018.07.005

- Lacey, N. (2019). Populism and the Rule of Law. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 15(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-101518-042919

- Marshall, M., Gurr, T. R., & Harff, B. (2019). State failure problem set. University of Maryland.

- Minkenberg, M. (1998). Context and consequence: The impact of the new radical right on the political process in France and Germany. German Politics and Society, 16(3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3167/104503098782487095

- Neumayer, E. (2005). Asylum recognition rates in Western Europe: Their determinants, variation, and lack of convergence. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49(1), 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002704271057

- Petrov, J. (2021). (De-)judicialization of politics in the era of populism: Lessons from central and Eastern Europe. The International Journal of Human Rights, 26(7), 1181–1206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2021.1931138

- Pettersson, T., Högbladh, S., & Öberg, M. (2020). Organized violence, 1989–2018 and peace agreements. Journal of Peace Research, 56(4), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319856046

- Prendergast, D. (2019). The judicial role in protecting democracy from populism. German Law Journal, 20(2), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2019.15

- Przybylski, W. (2018). Explaining Eastern Europe: Can Poland’s backsliding be stopped? Journal of Democracy, 29(3), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0044

- Ramji-Nogales, J., Schoenholtz, A. I., & Schrag, P. G. (2011). Refugee roulette: Disparities in asylum adjudication and proposal for reform. New York University Press.

- Ríos-Figueroa, J., & Staton, J. (2014). An evaluation of cross-national measures of judicial independence. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 30(1), 104–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ews029

- Rosenblum, M. R., & Salehyan, I. (2004). Norms and interests in US asylum enforcement. Journal of Peace Research, 41(6), 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343304047432

- Rottman, A. J., Fariss, C. J., & Poe, S. C. (2009). The path to asylum in the US and the determinants for who gets in and why. International Migration Review, 43(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.01145.x

- Salehyan, I., & Rosenblum, M. R. (2008). International relations, domestic politics, and asylum admissions in the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 61(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907306468

- Scartascini, C., Cruz, C., & Keefer, P. (2018). The Database on Political Institutions 2017 (DPI 2017). https://doi.org/10.18235/0001027

- Scheppele, K. L. (2002). ‘Declarations of independence: Judicial reactions to political pressure’. In S. B. Burbank & B. Friedman (Eds.), Judicial independence at the crossroads. An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 227–270). Sage.

- Schneider, G., Segadlo, N., & Leue, M. (2020). Forty-eight shades of Germany: Positive and negative discrimination in federal asylum decision making. German Politics, 29(4), 564–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2019.1707810

- Smith, K., & Waite, L. (2019). New and enduring narratives of vulnerability: Rethinking stories about the figure of the refugee. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(13), 2289–2307. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1496816

- Spirig, J. (2021). When issue salience affects adjudication: Evidence from Swiss asylum appeal decisions. American Journal of Political Science, 67(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12612

- Spriggs, J. F. (1996). The Supreme Court and federal administrative agencies: A resource-based theory and analysis of judicial impact. American Journal of Political Science, 40(4), 1122–1151. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111745

- Teitelbaum, M. S. (1984). Immigration, refugees, and foreign policy. International Organization, 38(3), 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300026801

- Thielemann, E., & Hobolth, M. (2016). Trading numbers vs. Rights? Accounting for liberal and restrictive dynamics in the evolution of asylum and refugee policies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(4), 643–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1102042

- Thielemann, E., & Zaun, N. (2018). Escaping populism – safeguarding minority rights: Non-majoritarian dynamics in European policy-making. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(4), 906–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12689

- Thränhardt, D., & Miles, R. (1995). Introduction: European integration, migration and processes of inclusion and exclusion. In R. Miles & D. Thränhardt (Eds.), Migration and integration: The dynamics of inclusion and exclusion (pp. xv–xxvii). Pinter Publishers.

- Toshkov, D. (2014). The dynamic relationship between asylum applications and recognition rates in Europe (1987–2010). European Union Politics, 15(2), 192–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116513511710

- Vanberg, G. (2000). Establishing judicial independence in West Germany: The impact of opinion leadership and the separation of powers. Comparative Politics, 32(3), 333–353. https://doi.org/10.2307/422370

- Vanberg, G. (2015). Constitutional courts in comparative perspective: A theoretical assessment. Annual Review of Political Science, 18(1), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-040113-161150

- Winn, M. (2021). The far-right and asylum outcomes: Assessing the impact of far-right politics on asylum decisions in Europe. European Union Politics, 22(1), 70–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520977005

- Wliezen, C. (1995). The public as thermostat: Dynamics for preferences of spending. American Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111666

- World Bank. (2020). World development indicators.