ABSTRACT

This paper examines the impact of Brexit on UK financial services policy, explaining recent reforms to the domestic financial regulatory framework and assessing the prospects for future divergence from EU rules. Deploying the lens of de-Europeanisation, we show that the failure to include financial services in the final UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement necessitated major institutional changes. By contrast, there has been very limited change to date with respect to policy, while the government’s ambitions for a ‘Big Bang 2.0’ package of regulatory reforms have been significantly scaled back. Drawing on insights from the political economy of finance, we argue that this process has been shaped by contested adaptational pressures mediated by three key variables: business unity, financial stability, and administrative capacity. The result is an emerging pattern of differentiated de-Europeanisation in financial services, ranging from intentional regulatory divergence to active alignment with EU rules.

Introduction

The United Kingdom’s (UK) withdrawal from the European Union (EU) in January 2020 has profound implications for financial services given London’s position as a leading international financial centre. A handful of works have examined the Brexit negotiations with reference to the financial sector, highlighting the ‘battle for finance’ between London and other important financial centres, such as Frankfurt and Paris (Howarth and Quaglia, Citation2018; Lavery et al., Citation2019), explaining the financial industry’s role in shaping the UK government’s position during the Brexit negotiations (James & Quaglia, Citation2019, Citation2020; Kalaitzake, Citation2021; Thompson, Citation2017a, Citation2017b), and examining how the sector has adapted since the UK’s withdrawal (Donnelly, Citation2022; Fraccaroli et al., Citation2023; Kalaitzake, Citation2022). However, we know less about how UK policy making in finance has evolved since Brexit.

The paper addresses this gap by analyzing the impact of Brexit on UK financial regulation, and the wider domestic financial regulatory framework. Our analytical framework is rooted in scholarship on Europeanisation (Börzel & Risse, Citation2003 ; Featherstone and Radaelli, Citation2003; Graziano & Vink, Citation2006) and, more recently, de-Europeanisation (Burns et al., Citation2019; Copeland, Citation2016; Gravey & Jordan, Citation2016; Wolff & Piquet, Citation2022) and differentiated dis-integration (Leruth et al., Citation2019; Schimmelfennig, Citation2018). Specifically, we consider the importance of key causal mechanisms – namely, institutional and policy misfit, adaptational pressure, and the mobilization of domestic actors – as explanations of domestic change. We also integrate insights from the political economy of finance to understand the critical role of financial industry divisions, financial stability concerns and administrative capacity constraints in shaping post-Brexit arrangements in finance.

We argue that the failure to include financial services in the 2020 UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) necessitated important changes concerning the institutional framework for UK financial services policy. This entailed the repatriation of financial regulatory competences from Brussels to London, the delegation of substantial new rulemaking powers to regulatory agencies, and proposals to strengthen regulators’ accountability to elected officials in government and Parliament. By contrast, there has been very limited change to date with respect to policy, while the government’s ambitions for a ‘Big Bang 2.0’ package of regulatory reforms have been significantly scaled back. We argue that this process has been shaped by contested adaptational pressures mediated by three key variables: business unity, financial stability and administrative capacity. The result is an emerging pattern of differentiated de-Europeanisation in financial services, ranging from intentional regulatory divergence to active alignment with EU rules.

In addition to making an important empirical contribution to mapping the evolution of post-Brexit financial regulation, the paper makes a significant theoretical contribution to de-Europeanisation scholarship. First, we integrate insights from the political economy of finance to unpack the key mediating variables that shape the nature and pace of domestic change in this critical economic sector. Second, we provide a more fine-grained analysis of the variability of possible regulatory outcomes from de-Europeanisation in this dynamic field. The paper also contributes to several themes that inform this special issue, including the de-Europeanisation of policy, shifting modes of governance following Brexit, and prospects for regulatory divergence from EU rules.

The paper is organized as follows. The following section reviews the literature on Europeanisation and de-Europeanisation, before outlining how insights from the political economy of finance help to unpack the dynamics of policy change and continuity following the UK’s withdrawal. The next section reviews the evolution of UK financial services policy before the 2016 referendum, and maps the mobilization of key domestic actors and their preferences around Brexit. The paper then assesses the outcome of the Brexit negotiations and the reforms to the UK’s financial regulatory framework, while the penultimate section unpacks the emerging pattern of differentiated de-Europeanisation embedded in the government’s proposed ‘Edinburgh Reforms’. The conclusion reflects on our theoretical contribution to de-Europeanisation scholarship.

State of the art and theoretical framework

There is a vast scholarship on Europeanisation (Borzel & Risse, Citation2003; Featherstone and Radaelli, Citation2003; Graziano & Vink, Citation2006) concerning how European integration transforms domestic-level institutions and policies (Knill & Lehmkuhl, Citation2002). Domestic change under Europeanisation is commonly attributed to the level of compatibility or ‘goodness of fit’ between EU policies and their domestic equivalents (Borzel & Risse, Citation2003). The degree of ‘fit’ or ‘misfit’ between the two generates ‘adaptational pressures’ for domestic change: the ‘better’ the ‘fit’, the less change will occur. Borzel & Risse (Citation2003) developed this into a ‘three step’ model of Europeanisation: while misfit gives rise to adaptational pressures (steps one and two), the nature and likelihood of domestic change is determined by key mediating factors (step three). These factors relate to the differential mobilization and empowerment of domestic actors, conditioned by structural factors like the existence of veto points (which can inhibit agreement) and formal institutions (which can facilitate adaptation by providing material or ideational resources) (Borzel & Risse, Citation2003, pp. 63–64).

Work on de-Europeanisation has expanded rapidly in recent years (Gravey & Jordan, Citation2016) and is equated to a ‘progressive detachment … from the political, administrative and normative influence’ of the EU (Tomini & Gürkan, Citation2021, p. 286). De-Europeanisation relates more broadly to processes of disintegration (Gänzle et al., Citation2019) or differentiated dis-integration (Leruth et al., Citation2019; Schimmelfennig, Citation2018), as evident in national opposition to further delegation of competences to the EU level (Copeland, Citation2016), resistance to implementing EU legislation (Raagmaa et al., Citation2014), and the ‘dismantling, diminution or removal’ of EU policies (Jordan et al., Citation2013, p. 795). Numerous scholars point to the UK’s withdrawal from the EU as evidence of the desire to ‘roll back’ EU policy (Copeland, Citation2016). But more recent studies of Brexit suggest that UK policy change may also result from ‘disengagement’ – equating to failed or passive de-Europeanisation – rather than a deliberate act of dismantling (Burns et al., Citation2019, p. 273), and could even lead to ‘re-engagement’ by the UK as a third country (Wolff & Piquet, Citation2022).

Unpacking de-Europeanisation

Our contribution to this scholarship is to unpack more systematically the process of de-Europeanisation. Using the goodness of fit model as our theoretical starting point, we posit that de-Europeanisation starts from a position of ‘perfect fit’ (i.e., membership), but then leads to adaptational pressures for divergence (rather than convergence) with the explicit intention of generating greater misfit. In other words, misfit no longer serves as the necessary condition for change, but instead becomes the dependent variable we seek to explain. This has two important implications. First, it means that the politics of de-Europeanisation operates according to a different temporal dynamic: political arguments are not about misfit or adaptational pressures in the present, but, more likely, at some hypothetical future point. Second, by shifting misfit into the future, the adaptational costs involved become less immediate, more uncertain, and thus subject to greater contestation.

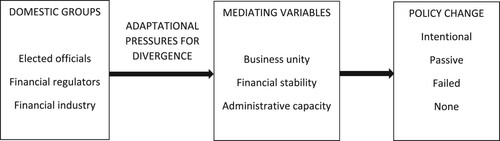

Like the goodness of fit model, we recognize the importance of domestic actors as critical mediating variables in explaining the nature and likelihood of domestic change arising from de-Europeanisation (see ). We emphasise the mobilization and balance of power between key domestic groups – elected officials, financial regulators, and the financial industry – with distinct preferences about post-Brexit arrangements. Given heightened uncertainty over the future, they play a critical role in shaping collective understandings about the adaptational costs of policy change (Dyson & Goetz, Citation2004, p. 16). Moreover, we expect these domestic actors to compete to shape the post-Brexit agenda by generating and manipulating adaptational pressures to serve their own political, bureaucratic or economic interests (Schmidt & Radaelli, Citation2004, p. 187). Drawing on insights from the political economy of finance, we highlight three key factors in shaping the dynamics of de-Europeanisation.

Figure 1. Differentiated de-Europeanisation.

First, we emphasise the importance of business unity. The degree to which organized economic interests are unified is a critical factor in lobbying success because it allows scarce resources to be pooled and signals the strength of support for a policy to external audiences (Beyers & Braun, Citation2014; Hula, Citation1999). The financial sector wields a formidable capacity for collective action (Bell & Hindmoor, Citation2015) through centralized associations (Chalmers, Citation2020) and is uniquely placed to leverage support from the wider business community (Pagliari & Young, Citation2014, p. 584). Conversely, where business is internally divided and less capable of engaging in coordinated lobbying, its collective influence will be significantly diminished (Young & Pagliari, Citation2017). Hence, we expect the extent to which the financial industry is unified or divided in its response to Brexit will be critical to shaping the government’s reform agenda.

Second, domestic change is shaped by financial stability concerns. These relate to the systemic implications of cross-border financial activity, which generate externalities and create opportunities for regulatory arbitrage (Simmons, Citation2001; Singer, Citation2007). Moreover, the size, concentration and interconnectedness of large financial institutions risk contagion effects, rendering them systemically-important and ‘too big to fail’ (Bell & Hindmoor, Citation2018). Since the 2008 crisis, financial regulators have sought to address these concerns through new prudential regulations and oversight mechanisms (Baker, Citation2013), and the adoption of tougher (non-binding) global standards, notably in banking (Quaglia & Spendzharova, Citation2019). Studies show that prudential regulators, predominantly located in central banks, are highly protective of their powers and reputation for upholding financial stability (Hungin & James, Citation2019; McPhilemy & Moschella, Citation2019), and thus we expect regulators to resist reforms that threaten to undermine them.

Third, the goodness of fit model stresses the importance of administrative capacity with respect to the ability of government to implement policy change (Borzel & Risse, Citation2003; Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, Citation2004). Broadly speaking, the Europeanisation literature points to the importance of political resources (in terms of political leadership and parliamentary time devoted to legislation) and bureaucratic resources (including financial and human resources, as well as technical expertise) as critical factors in shaping the pace and scope of domestic reform (see Goetz, Citation2001; Knill, Citation2001; Page, Citation2003). Similarly, the concept of regulatory capacity is deployed in the political economy of finance literature as a key determinant of a state’s ability to regulate its financial sector efficiently, and to shape international regulatory debates and the development of global standards (Drezner, Citation2007; Posner, Citation2009). As such, we expect capacity constraints to serve as a significant obstacle to implementing regulatory reform.

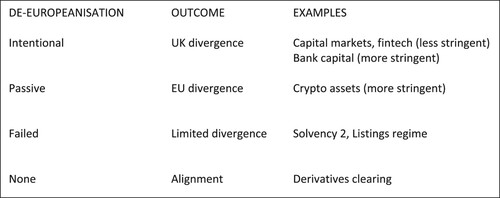

We expect adaptational pressures mediated by key variables to produce patterns of differentiated de-Europeanisation: that is, outcomes characterized by significant variation in the nature and scope of policy change. Building on existing scholarship, our framework differentiates between four outcomes corresponding with distinct modes of de-Europeanisation. Intentional de-Europeanisation refers to the deliberate dismantling of pre-existing EU rules and frameworks with the intention of generating divergence (Copeland, Citation2016, p. 1126). By contrast, passive de-Europeanisation describes a process of disengagement whereby existing rules and frameworks are not actively dismantled, nor updated or adapted to keep pace with changes at the EU level – the result of which will be divergence over time (Burns et al., Citation2019, p. 273). We use failed de-Europeanisation here to refer to cases of intentional or passive de-Europeanisation that produce limited or no divergence: for instance, a situation in which the UK and EU independently adjust their rules in an identical or similar way such that they remain (unintentionally) broadly aligned. None simply refers to the absence of de-Europeanisation: that is, the active and deliberate process of ensuring that UK and EU policies remain closely aligned, whether explicitly or tacitly.

The paper assesses the explanatory power of the framework against the empirical record regarding UK financial services policy both pre- and post-Brexit. The material was gathered through a systematic survey of public documents and press coverage over the past five years, together with the first-hand testimonies of twelve practitioners – including financial regulators, industry stakeholders and elected officials – who were interviewed on an anonymous basis between 2018 and 2022 (see List of Interviews at the end of the paper).

Finance before Brexit: a Europeanised UK in a changing Europe

The financial and related professional services industry is a critical part of the UK economy, contributing £194 billion to UK gross value added and generating an annual trade surplus of £78 billion (HMT, Citation2021a). London is also ranked as the world’s leading financial centre, just ahead of New York and significantly ahead of other EU cities. This global pre-eminence owes a great deal to domestic and European level processes of financial integration since the 1980s. In particular, the City of London has historically been well placed to exploit the UK’s access to the lucrative EU single market, together with further opportunities generated by the development of the European single currency (Thompson, Citation2017b).

Financial services regulation is a policy area that has been extensively Europeanised (Mügge, Citation2010), particularly since the 2008 global financial crisis (Mügge, Citation2014; Quaglia, Citation2014). As such, competence for financial regulatory policy making was gradually transferred to the EU level (Posner & Véron, Citation2010). The result was the development of an extensive body of EU legislation covering a vast array of financial services (banks, securities, insurance, investment funds, derivatives, payments), which is incorporated into the domestic legal framework of member states (HMT, Citation2021a).

The UK was historically a ‘pace-setter’ in shaping the development of EU financial regulation (see James & Quaglia, Citation2020). In large part, this was a reflection of the substantial ‘market power’ (Drezner, Citation2007) wielded by the UK on account of the size and importance of the UK financial sector, and London as a financial centre, for the whole of Europe (HMT, Citation2021a). UK regulators wielded extensive expertise and ‘regulatory capacity’ on financial matters, and were active participants in transnational regulatory networks and global standard-setting fora, like the Bank for International Settlements and Financial Stability Board. At the EU level, the UK authorities frequently formed coalitions with like-minded member states, notably, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Sweden (Quaglia, Citation2010), while the UK financial industry wielded significant influence through powerful transnational alliances and lobbying associations (Hopkin & Shaw, Citation2016). Key domestic groups – elected officials, regulators and industry – often had divergent preferences on the design, definition or scope of specific financial regulations. Nonetheless, a critical source of EU and international influence was the broad alignment of interests around the importance of maintaining the UK’s ‘light touch’ financial regulatory regime, and the importance of ‘market making’ regulation at the EU level to facilitate financial integration (see Quaglia, Citation2010).

The UK’s influence in shaping post-crisis EU financial regulation was more mixed. Long-standing tensions between ‘market making’ and ‘market shaping’ coalitions of member states (Quaglia, Citation2010) were exacerbated after 2010, fuelling Franco-German led efforts to adopt more stringent EU rules, particularly with respect to hedge funds. At home, divisions were also exposed as elected officials and regulators sought to impose more stringent post-crisis capital rules on UK banks than those agreed at the EU level (James & Quaglia, Citation2019, Citation2020). Tensions were compounded by the further integration of the Eurozone, and particularly moves towards Banking Union, which the UK feared would lead to ‘caucusing’ by Eurozone member states to the detriment of UK financial interests (Thompson, Citation2017a). This culminated in Prime Minister David Cameron’s renegotiation of the terms of British entry in early 2016, motivated in large part by a desire to secure an effective UK veto over all future EU financial legislation (James et al., Citation2021). The following section details how the Brexit referendum ultimately exposed the underlying fault lines over finance, not just between London and Brussels, but also between key domestic groups.

Negotiating Brexit and the UK’s financial regulatory framework

This section maps the preferences and influence of the main domestic groups before the June 2016 Brexit referendum and the subsequent UK-EU negotiations in the area of financial services; and explains the proposed reforms to the UK’s financial regulatory framework.

Brexit and the failure of finance

The position of the largest UK financial firms was strongly in favour of continued EU membership, fearing that UK withdrawal would generate substantial political and economic adjustment costs (City UK, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Thompson, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The political costs related to the UK’s loss of influence over future EU financial regulation, while economic costs would result from diminished access to the EU single market. In particular, UK firms risked losing lucrative ‘passporting rights’ which enabled them to trade across the EU without the need for further authorization (CityUK, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). UK financial regulators were also firmly opposed to Brexit, and worked closely with the Treasury and financial sector to try to quantify the adaptational costs of Brexit (see Bank of England, Citation2015; HMT, Citation2016).

Following the referendum and the formation of a new government under Theresa May, the UK swiftly rejected the possibility of maintaining a ‘perfect fit’ with EU regulation. This reflected adaptational pressures from different domestic groups, each of which favoured the possibility of future regulatory divergence for very different reasons. The first group was a significant section of Conservative MPs that favoured a decisive break from EU membership. Led by the European Reform Group, these elected officials pushed Prime Minister May to prioritize ending freedom of movement in recognition of the concerns of Leave voters, which in effect ruled out the possibility of continued single market membership (UK government, Citation2017; interviews, 10 July 2017; 18 July 2017). Beyond this, however, there was little consensus within government – let alone within the wider parliamentary party – about what the future UK-EU relationship should look like (see James & Quaglia, Citation2019).

Second, the UK financial sector itself began to show signs of internal divisions over how to respond to Brexit (interviews, 14 June 2017; 19 June 2017). Certain parts of the City, notably hedge funds and parts of the fintech sector, actively supported pro-Brexit groups, such as City for Britain, and gradually coalesced into a disparate coalition of lobby groups and think tanks calling for a decisive break with the EU (interview, 16 April 2018). In the absence of wide-ranging regulatory equivalence arrangements with the EU, for example, pro-Brexit groups called for radical deregulation to boost the City’s competitiveness and to encourage the sector to reorient towards global markets (Reynolds, Citation2016). However, these dissident voices continued to be marginalized by the largest and best resourced financial firms and associations (interview, 15 February 2018). These continued to push for regulatory continuity – either through full membership of the European Economic Area, or a ‘special deal’ for finance that would in effect preserve the UK’s passporting rights (CityUK, Citation2017).

Third, senior UK financial regulators in the Bank of England became increasingly sceptical about the possibility of a ‘soft’ Brexit option that, it was claimed, would leave the UK as a ‘rule taker’ from Brussels (interview, 23 October 2017). Indeed, the Bank Governor, Mark Carney, became increasingly outspoken in his criticism of any attempt to tie the hands of UK regulators. In particular, he argued that the size and global nature of the City of London meant that the UK needed sufficient regulatory autonomy to uphold financial stability – in other words, the freedom to impose tougher rules on UK banks compared to their EU counterparts (Carney, Citation2017). Regulators’ unity in the face of government indecision and industry divisions proved decisive in shifting the UK government’s position towards the imperative of upholding financial stability.

The politicization of (future) divergence became the key point of contention between UK and EU negotiators, contributing to the eventual failure to reach a deal in finance. But this was less to do with the immediate prospect of regulatory misfit, and more to do with the institutional process through which this would be managed. Although the UK government rejected the EEA option, it also opposed relying on existing EU third country equivalence provisions. Equivalence provisions enable firms located outside the EU to conduct certain financial activities in the EU, without being subject to EU regulation and supervision in addition to those of their home country (Quaglia, Citation2015). The UK objected that EU equivalence rules provided only partial coverage for financial services, while EU equivalence assessments tended to be complex, temporary and highly politicized. Following the 2017 general election, the main UK financial associations developed a compromise solution capable of uniting ministers, regulators, and the largest financial firms (interview, 19 June 2017; James et al., Citation2021). The result was the so-called ‘mutual recognition’ model in which UK and EU financial regulation would be recognized as equivalent, thereby guaranteeing mutual access for financial firms (IRSG, Citation2017). Moreover, formal institutional arrangements would be put in place so that potential regulatory divergence and disputes could be amicably negotiated and managed.

The priority for EU27 national governments was to preserve and maintain the integrity of the single market. This meant ruling out any form of ‘special deal’ for finance to the extent that this would entail granting a third country the same access to the EU single market as a full member (Ranking, Citation2017). The EU’s formal negotiating guidelines adopted in April 2017 explicitly ruled out ‘a sector-by-sector approach’ and that any future framework should ‘respect its regulatory and supervisory regime and standards’ (European Council, Citation2017, p. 3). The French and German governments had additional incentives to deny passporting rights as this would create opportunities to attract lucrative business away from London (Lavery et al., Citation2019). During the negotiations, the Commission warned that the prospect of UK financial regulation diverging from EU rules after Brexit would lead to reduced access to the EU single market (Donnelly, Citation2022). To bolster its negotiating position, it also proposed strengthening procedures for assigning equivalence for ‘high impact third countries’ (Howarth and Quaglia, Citation2018). EU financial regulators – located in the European Central Bank and European Supervisory Authorities – were equally resolute that, as a third country, UK financial firms would need to comply fully with EU and/or member state rules to continue accessing EU customers.

Ultimately the UK’s desire for a bespoke deal for financial services failed to overcome EU objections. This reflected a mistaken belief on the part of UK negotiators that ‘perfect fit’ at the point of Brexit would be sufficient grounds for securing maximum EU access in a post-Brexit deal. On the contrary, the EU was more concerned about the possibility of future regulatory divergence with the UK, and was unwilling to countenance being locked into any arrangement that threatened its own autonomy to determine financial regulation. Consequently, financial services were largely excluded from the EU-UK future relationship negotiations that commenced in March 2020.

The UK-EU TCA signed in December 2020 made no specific provisions for financial services, although it was accompanied by a non-binding Joint Declaration committing UK and EU regulators to ‘structured regulatory cooperation on financial services’. A four-page EU-UK Memorandum of Understanding detailing the broad outlines of the future regulatory relationship for financial services was agreed in March 2021, but this only provided for non-legally binding cooperation organized around a Joint EU-UK Financial Regulatory Forum meeting every six months (HM Treasury, Citation2021e). Crucially, it did not address the issue of market access, and so UK-based financial firms would be subject to existing EU third country rules from 1 January 2021. From the perspective of industry, the outcome was ‘a complete and unmitigated failure on the part of financial services’ (interview, 22 June 2022).

Reforming the domestic institutional framework

Brexit generated immediate adaptational pressures for domestic change by necessitating the full transposition of EU legislation into UK law, and the design of a new financial regulatory framework. The 2018 European Union Withdrawal Act incorporated all EU-derived domestic legislation (for example, legislation implementing EU directives) and directly applicable EU law (for example, regulations) onto the UK statute book, including financial services (HMT, Citation2021a). Recognizing that retained EU legislation might need to be tailored to the UK’s new post-Brexit context, the government launched a major review of the institutional framework for financial services regulation and existing financial legislation in June 2019.

The full proposals from the ‘Future Regulatory Framework Review’ were published in November 2021 (HMT, Citation2021b). They confirmed that while government and Parliament would set the broad policy framework for financial services regulation, the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) would be responsible for issuing regulation using their existing rule-making powers and newly delegated powers. This constituted a significant extension of regulators’ rule-making powers, justified on the grounds that this was necessary to enable regulators to make rules covering all areas of financial services included in retained EU law. The government therefore proposed to give regulators the power to set direct regulatory requirements for firms, requiring the government to gradually repeal parts of retained EU law so that the regulators would be able to replace it with regulatory requirements in their own rulebooks. More controversially, the government also proposed that UK regulators be given a new secondary objective for growth and competitiveness (HMT, Citation2021b). In addition, financial regulators would be subject to greater accountability through the introduction of a new ‘call-in’ power permitting the government to block or change decisions by regulators in exceptional circumstances.

The UK financial industry broadly welcomed the outcome of the review, and strongly endorsed the new growth and competitiveness objective for regulators. One interviewee noted that this recommendation had been explicitly pushed by industry and that they would seek to forge an ‘alliance’ with the Treasury to defend this ‘win’ as the legislation made its way through Parliament (interview, 24 June 2022). Lobbyists’ main concern was that, in their eyes, the government’s reforms would ‘potentially made UK regulators the most powerful financial regulators in the world’, a decision that was somewhat cynically attributed to the Treasury’s desire to ‘avoid blame’ for the next financial crash (interview, 24 June 2022). From the perspective of industry, this necessitated significantly strengthened mechanisms of accountability and scrutiny of financial regulators (IRSG, Citation2021).

To enhance Parliament’s capacity to provide more ‘systematic’ and ‘technical democratic oversight’ of new regulatory initiatives, City lobby groups called for a dedicated Treasury Select Committee sub-committee on financial services regulation (IRSG, Citation2021) – a recommendation that was eventually adopted by Parliament in June 2022. They also welcomed the proposed power for the Treasury to require regulators to review their rules and requested clarification on specific triggers by which it might be used. In May 2022, a combined statement from the largest financial associations called for specific metrics and criteria to determine if regulators are fulfilling the new competitiveness objective, and ‘public reporting duties’ which require ‘dynamic benchmarking’ against other international regulators (CityUK, Citation2022).

By contrast, financial regulators welcomed the allocation of additional powers and sought to resist potential political interference. They were sceptical of the new growth and competitiveness mandate but succeeded in ensuring that, as a secondary objective, regulators would continue to have sufficient flexibility to prioritize financial stability concerns. The Bank was particularly critical of the proposed ‘call-in’ power as a threat to its regulatory autonomy (Kleinman, Citation2022). Tellingly, Governor Bailey told the Treasury Committee in July 2022 that he opposed any changes that threatened the ‘independence of regulators’ as this would undermine financial stability (Reuters Citation2022). When the Financial Services and Markets Bill was published in July 2022, it was notable that the call-in power had been replaced by a weaker proposal enabling the Treasury to force regulators to review their rules (Griffiths, Citation2022). However, concern remained that this ‘rule-review’ power could be wielded without public or parliamentary disclosure, which still risked ‘blurring the vital distinction between the regulators and the executive’ (interview, 8 August 2022). In the face of continued opposition from the Bank of England, however, the proposal was dropped altogether from the Bill in November 2022.

Differentiated de-Europeanisation: prospects for post-Brexit divergence

Since the UK’s formal departure from the EU in January 2020, the EU has only granted regulatory equivalence in a limited number of financial services – specifically, derivatives trading by UK central clearing counterparties (CCPs) (James & Quaglia, Citation2021). This has generated increasing adaptational pressures for divergence within the UK. In particular, there have been mounting calls within government and some sections of the financial industry to support UK growth and competitiveness through a more substantive and immediate break with existing EU rules – widely heralded by ministers as a ‘Big Bang 2.0’ for the City of London (Morales, Citation2021).

In a speech at the Mansion House in July 2021, Chancellor Rishi Sunak noted that the UK now had ‘the freedom to do things differently and better, and we intend to use it fully’ and that it was the government’s intention to ‘sharpen our competitive advantage in financial services … boosting our competitiveness across both regulation and tax’ (Sunak, Citation2021). Alongside the speech, the government published its post-Brexit strategy for financial services, titled ‘A New Chapter for Financial Services’ (Citation2021a). While vague on detail, it boasted of signing a new financial services partnership with Singapore to facilitate regulatory cooperation, established a new US-UK Financial Regulatory Working Group, set out proposals to strengthen the UK’s status as a centre for Islamic finance, and aspired to deepen financial services relationships with China, India and Brazil. Longer term, the government set out a vision for UK financial services that would be a ‘global fintech hub’, harnessing the benefits of cryptoassets and stablecoins, and establishing a taskforce to explore the creation of a UK Central Bank Digital Currency.

In December 2022, the new Chancellor Jeremy Hunt published the long-awaited package of regulatory reforms, dubbed the ‘Edinburgh Reforms’, consisting of 31 regulatory proposals designed to take advantage of the UK’s post-Brexit ‘freedoms’ (HM Treasury, Citation2022). Critics were quick to complain that the ‘laundry list’ of measures were modest in scope, highly technical, and lacked prioritization. Moreover, roughly half of the measures – including plans to relax the Senior Managers Regime and UK bank ringfencing rules – had little or nothing to do with Brexit (Wright & Bierbaum, Citation2023). Nonetheless, the Edinburgh Reforms point to an emerging pattern of differentiated de-Europeanisation, characterized by significant variation in policy change ranging from intentional divergence to active alignment (see ). We cite examples of proposed financial regulatory reforms for each, albeit with the important caveat that these are potential outcomes and thus subject to change.

The area with the greatest potential for UK rules to diverge and become less stringent than EU rules relates to capital markets and non-banking financial institutions. In particular, the government has proposed to support wholesale markets by relaxing regulatory requirements as currently stipulated in the EU’s Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (Mifid II), and to undertake ‘targeted and appropriate refinement’ of the 2019 EU Securitisation Regulation (HM Treasury, Citation2021c). Consultations were also initiated on tailoring rules covering short selling, payment accounts, investment research, and tax treatment of fund management. Moreover, there is scope for significant UK divergence in those areas that are comparatively lightly regulated – notably, digital finance. Ministers have repeatedly spoken positively about the benefits of attracting fintech firms to London, and the Edinburgh Reforms pledge to introduce new rules to expand the Investment Manager Exemption for cryptoassets, to implement a new Financial Market Infrastructure Sandbox, and to consult on a UK retail Central Bank Digital Currency (HM Treasury, Citation2022). By contrast, the recent introduction of stringent new EU rules in the 2022 Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) Regulation represents an example of passive de-Europeanisation whereby the EU departs from current UK practice.

Importantly, UK divergence may be limited by parallel developments at the EU level. For example, the government heralded the replacement of the EU Solvency II Directive for insurance firms, which it described as being ‘overly rigid and rules-based’, claiming that this would unlock substantial new funds for infrastructure investment (HM Treasury, Citation2021d). It also planned to encourage overseas firms to raise capital in London by simplifying the UK Listings Regime, parts of which were derived from the EU Prospectus Directive. Yet, in both cases, plus at least another six areas covered by the Edinburgh Reforms, the EU is currently engaged in reviewing its own framework and has proposed similar reforms (Wright & Bierbaum, Citation2023). Hence, while the UK has the intention of diverging from EU rules, the outcome may be closer to failed de-Europeanisation: that is, limited or no divergence resulting from the UK and EU independently introducing similar regulatory changes.

The ability of the UK to secure a Brexit dividend in the area of banking regulation – notably rules covering bank capital, liquidity and resolution – is also likely to be tightly constrained. In large part this reflects the systemic importance attached to this sector by prudential regulators in the Bank of England and their leading role in developing tough new global standards following the 2008 crisis. In fact, UK regulators have not only committed to transposing the most recent Basel Committee capital standards in full, but may also continue ‘goldplating’ these with even higher standards at home (Noonan, Citation2022a) – a potential example of UK divergence through greater stringency. Finally, we postulate that financial activities characterized by high levels of cross-border interdependency – such as the clearing of euro-denominated derivatives by London-based central counterparties – are likely to generate significant pressures for continued regulatory alignment to underpin the continuation of the current temporary equivalence arrangements.

In short, the government’s ambition for a ‘Big Bang 2.0’ reform package has been significantly scaled back, together with the prospect of immediate regulatory divergence from the EU. We explain this as the consequence of three key mediating factors in the de-Europeanisation process. The first is financial stability: specifically, the opposition of financial regulators to regulatory changes that threaten their capacity, discretion and reputation for upholding financial stability. Senior UK regulators from the Bank of England and FCA repeatedly stated that long-term growth and competitiveness would not be achieved by lowering standards (Bailey, Citation2022). Furthermore, they appealed to the need to uphold post-crisis global standards in banking – which they played a leading role in designing – and called for these to be extended to systemically-important non-banking institutions. Following the publication of the Edinburgh Reforms, for example, the Bank Governor warned against the dangers of ‘unlearning’ the lessons of 2008 and called for ‘urgent’ international action to address systemic risks in the shadow banking sector following market turmoil in early 2020 (Noonan, Citation2022b).

The imperative of upholding financial stability fuelled repeated clashes with elected officials at home. For example, the Bank of England was reportedly in a ‘battle’ to resist government pressure for post-Brexit deregulation, noting that Prime Minister Johnson and Chancellor Sunak had grown increasingly ‘impatient’ with regulators’ resistance to their plans for divergence (Parker et al., Citation2022). Similarly, senior industry figures complained that ‘the slowness and caution [of regulators] are not helping the industry at all. They are taking a line-by-line approach. The expectation had been that the UK would take a far more free market approach’ (Parker et al., Citation2022). Others claimed that regulators were ‘inherently conservative’ and ‘have an incentive to over-regulate rather than under regulate’, prioritizing the ‘stability of the graveyard’ (interview, 4 July 2022). Further evidence comes from the PRA’s vocal resistance to the government’s plans for relaxing the Solvency II Directive (Kleinman, Citation2022). Early in the process, PRA chief executive Sam Woods intervened personally by expressing scepticism about the need for reform, insisting that there could not be a ‘free lunch’ for the industry and that simply loosening regulations would put policyholders at risk (Parker & Smith, Citation2022). This triggered a war of words with the government, with No.10 expressing frustration at the pace of change and Treasury officials claiming that the PRA was being a ‘dog in a manger’ over the issue.

The second barrier to regulatory divergence is the absence of business unity. In short, the most globally-oriented financial firms, which tend to be represented by the largest trade associations, are the most vocal in advocating continued broad alignment with EU rules. Hence, the City of London Corporation (Citation2022) noted in its response to the framework review that ‘few are calling for a fundamental change in regulation’ equivalent to the ‘1980s Big Bang’, but that instead it should be an opportunity to ‘re-regulate, rather than deregulate’. It stressed the importance of ‘continuity and certainty’ for the sector, warned against ‘change for the sake of change’, and suggested that future changes should be ‘clear, consulted on and subject to appropriate costs and benefit analysis and impact assessment’. Similarly, the main City lobby group argued that it was vital for UK regulation to remain ‘broadly in line with the global environment’, and that any decision over divergence should consider the impact on the UK’s competitiveness and market access, with particular regard to the UK’s close ties with the EU ‘built over 40 years’ (IRSG, Citation2022). By contrast, more domestically-focused financial firms tend to be more supportive of divergence, particularly where this reduces their domestic regulatory burden. In particular, some parts of the business community – notably the UK’s SME sector – have become increasingly outspoken in their demands for regulatory change and impatient at the government’s slow pace of delivery (interview, 24 June 2022). As one interviewee quipped, ‘industry can be Janus-faced – they hate regulation until you want to change it’ (interview, 22 June 2022).

Beyond the EU, the financial industry remains similarly cautious. It accepts that there is little prospect of improved relations with the EU and that the prospect of further equivalence determinations is ‘dead in the water’ and a ‘price not worth paying’ (interview, 4 July 2022). Hence, the sector is broadly supportive of the government’s strategy of acting unilaterally to strengthen ties with non-EU jurisdictions based on the G20-endorsed deference model (City of London Corporation, Citation2022). For example, a recent report produced by New Financial and the Atlantic Council calls for the UK to deepen transatlantic ties by potentially pursuing regulatory equivalence with the US, and to strengthen bilateral cooperation agreements with ‘like-minded open economies’ such as Switzerland, Canada, Japan, South Korea and Australia. But industry is ‘nervous’ about the prospect of the government negotiating full Free Trade Agreements with third countries as this risks financial services becoming politicized and ‘traded off’ against other economic interests (interview, 22 June 2022).

The third factor that affects potential regulatory divergence relates to administrative capacity. There is widespread scepticism that the government will implement the plethora of existing regulatory reforms, let alone pledge to deliver a more ambitious post-Brexit agenda. While there has been an abundance of rhetoric from ministers about the need to tailor UK rules and exploit Brexit opportunities, industry lobbyists complained that there was a ‘massive gap between government rhetoric and regulatory action’ and that it ‘talked a big game but was failing to deliver’ (interview, 24 June 2022). Another blamed ‘capacity challenges’ within the Treasury for its tendency to simply ‘cut and paste’ imperfect EU legislation into domestic law and to ‘farm everything out’ to regulators (interview, 4 July 2022). The impact of doing so is to slow the pace of reform by further ‘hollowing out’ government capabilities, resulting in the UK losing any ‘post-Brexit first mover advantage’ (interview, 4 July 2022). Industry also bemoaned the absence of a clear strategy or ‘roadmap’ for post-Brexit financial regulation which was instead filled by a series of ‘tactical decisions and piecemeal reforms’ for the ‘sake of doing something’ (interview, 4 July 2022). This was compounded by political uncertainty regarding the government’s policy agenda following the resignation of Prime Minister Johnson in July 2022 and the turmoil surrounding the short-lived premiership of Liz Truss in September 2022.

While the new Treasury sub-committee on financial regulation is an attempt to bolster parliamentary capacity, there remains ‘a massive concern that Parliament is not adequately resourced to do accountability and scrutiny’ and risked ‘major legislative gridlock’ (interview, 24 June 2022). UK regulators have also acknowledged the importance of capacity constraints. In evidence to the House of Lords, Sam Woods argued that the PRA would need to ‘staff up’ to meet its ‘bigger rule-making responsibility’ (European Affairs Committee, Citation2022). Several interviewees noted serious reservations about the FCA’s ongoing lack of capacity stemming from high turnover and unfilled posts following the appointment of a new chief executive, Nikhil Rathi (interview, 22 June 2022). In sum, de-Europeanisation in the area of financial regulation remains seriously hampered by a capability-expectations gap largely of the government’s own making.

Conclusions

This article set out to assess and explain the implications of Brexit for UK policy-making in financial services. We detail the important institutional changes regarding the UK’s future financial regulatory framework, including the repatriation of competences to Westminster and the delegation of new rulemaking powers to regulators. By contrast, there has been very limited policy change to date, while the government’s ambitions for a ‘Big Bang 2.0’ package of regulatory reforms have been significantly scaled back. Instead, we identify an emerging pattern of differentiated de-Europeanisation characterized by significant variation in domestic change, ranging from intentional regulatory divergence to active alignment with EU rules.

The paper contributes to the ongoing theoretical development of de-Europeanisation in two ways. First, we integrate insights from the political economy of finance to unpack the key mediating variables that shape the nature and pace of domestic change in this critical economic sector. The factors we identify – namely, financial industry divisions, financial stability concerns and administrative capacity constraints – echo many of the intervening variables identified in the earlier Europeanisation literature (for example, see Borzel & Risse, Citation2003; Featherstone and Radaelli, Citation2003; Graziano & Vink, Citation2006). However, applying these concepts to the goodness of fit model ‘in reverse’ also enables us to tease out important differences. In particular, the fact that de-Europeanisation relates to future ‘misfit’ between the UK and EU means that the adaptational costs and benefits involved become less immediate, more uncertain, and thus subject to greater contestation. We argue that this is a critical factor in empowering key domestic groups with the resources to shape expectations about the likelihood and desirability of divergence – namely, financial regulators and industry associations. This has served to blunt claims from elected officials about prospective Brexit dividends.

Our second contribution is to provide a more fine-grained analysis of the variability of possible regulatory outcomes from de-Europeanisation in this dynamic field. In particular, we differentiate between four main modes of de-Europeanisation which produce significant variation in the likely nature and scope of policy change. Two of our modes – intentional and passive – seek to clarify concepts that have been deployed in the existing de-Europeanisation literature (for example, Burns et al., Citation2019; Copeland, Citation2016), but which arguably lack definitional precision. We also echo Wolff and Piquet (Citation2022) in stressing the likelihood of continued engagement and active alignment in key sectors. But an important innovation we make is to distinguish these from ‘failed’ de-Europeanisation – a consequence of unintended alignment resulting from the parallel but independent adjustment of UK and EU rules. We argue that this is likely to play a significant role in thwarting UK efforts to secure post-Brexit competitive advantage through less stringent regulation in a range of key sectors. Future research could explore how this process is facilitated by processes of policy learning by UK and EU regulators acting independently, but nonetheless interacting frequently through global standard setting bodies and informal regulatory networks.

As the UK passes the third anniversary of its official departure from the EU, the implications of Brexit for financial services are becoming increasingly clear. As recent studies detail, Brexit has introduced significant barriers to cross-border trade in financial services, causing over 400 firms to relocate business, staff or legal entities to the EU27, including over £900bn in bank assets (Hamre & Wright, Citation2021). Moreover, these figures underestimate the longer-term damage to the UK financial sector as it adjusts to the political reality of no foreseeable improvement in UK firms’ access to the EU single market, contributing to a further drip-feed of business and activity out of London. Successive UK prime ministers since 2016 have looked to financial services to revive UK growth and competitiveness in response to the political imperative of addressing the UK’s poor post-Brexit economic performance. That the ambitions of elected officials have repeatedly been thwarted is also a recognition that meaningful de-Europeanisation requires more than an act of political willpower, but instead necessitates the support of powerful domestic groups and the full capacities of the British state.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the editors of this special issue Patrick Diamond and Jeremy Richardson as well as the anonymous JEPP reviewers for their constructive feedback on an earlier draft of this paper. We are indebted to the twelve practitioners whom we interviewed for this research between June 2017 and December 2022 on an anonymized basis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Scott James

Scott James is a Reader in Political Economy at King's College, London, UK.

Lucia Quaglia

Lucia Quaglia is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Bologna, Italy.

References

- Bailey, A. (2022, February 10). Speech: A resilient financial system. Bank of England. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2022/february/andrew-bailey-speech-at-thecityuk-annual-dinner.

- Baker, A. (2013). The gradual transformation? The incremental dynamics of macroprudential regulation’. Regulation & Governance, 7(4), 417–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12022

- Bank of England. (2015, October). EU membership and the Bank of England.

- Bell, S., & Hindmoor, A. (2015). Taming the city? Ideas, structural power and the evolution of British Banking Policy Amidst the Great Financial Meltdown. New Political Economy, 20(3), 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2014.951426

- Bell, S., & Hindmoor, A. (2018). Are the major global banks now safer? Structural continuities and change in banking and finance since the 2008 crisis. Review of International Political Economy, 25(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2017.1414070

- Beyers, J., & Braun, C. (2014). Ties that count: Explaining interest group access to policymakers. Journal of Public Policy, 34(1), 93–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X13000263

- Borzel, T., & Risse, T. (2003). Conceptualising the domestic impact of Europe. In K. Featherstone, & C. Radaelli (Eds.), The politics of Europeanization (pp. 57–80). Oxford University Press.

- Burns, C., Gravey, V., Jordan, A., & Zito, A. (2019). De-Europeanising or disengaging? EU environmental policy and Brexit. Environmental Politics, 28(2), 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1549774

- Carney, M. (2017, January 11). Oral evidence. Treasury Committee, House of Commons.

- Chalmers, A. W. (2020). Unity and conflict: Explaining financial industry lobbying success in European Union public consultations. Regulation & Governance, 14(3), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12231

- The City of London Corporation. (2022, March 30). Memorandum from the City of London Corporation. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/107600/pdf/

- The CityUK. (2016a, April). Leaving the EU: Implications for the UK financial services sector. https://www.pwc.co.uk/financial-services/assets/Leaving-the-EU-implications-for-the-UK-FS-sector.pdf

- The CityUK. (2016b, October). The Impact of the UK’s exit from the EU on the UK based financial services sector. https://www.thecityuk.com/assets/2016/Reports-PDF/The-impact-of-the-UKs-exit-from-the-EU-on-the-UK-based-financial-services-sector.pdf

- The CityUK. (2017, January). Brexit and UK-based financial and related professional services.

- The CityUK. (2022, May 10). Financial services trade associations common statement on financial services Bill. https://www.thecityuk.com/news/financial-services-trade-associations-common-statement-on-financial-services-bill/

- Copeland, P. (2016). Europeanization and de-Europeanization in UK employment policy: Changing governments and shifting agendas. Public Administration, 94(4), 1124–1139. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12283

- Donnelly, S. (2022). Post-Brexit financial services in the EU. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2061579

- Drezner, D. (2007). All politics is global: Explaining international regulatory regimes. Princeton University Press.

- Dyson, K., & Goetz, K. (2004). Living with Europe: Power, constraint and contestation. In K. Dyson, & K. Goetz (Eds.), Germany, Europe and the politics of constraints (pp. 3–35). Oxford University Press.

- European Affairs Committee. (2022, June 23). The UK-EU relationship in financial services. 1st report of Session 2022-23. House of Lords. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5803/ldselect/ldeuaff/21/2102.htm

- European Council. (2017, April 29). Guidelines for Brexit negotiations.

- Featherstone, K., & Radaelli, C. (Eds.). (2003). The politics of Europeanization. Oxford University Press.

- Fraccaroli, N., Regan, A., & Blyth, M. (2023). Brexit and the ties that bind: How global finance shapes city-level growth models. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2176531

- Gänzle, S., Leruth, B., & Trondal, J. (Eds.). (2019). Differentiated integration and disintegration in a post-brexit era. Routledge.

- Goetz, K. H. (2001). Making sense of post-communist central administration: Modernization, Europeanization or Latinization? Journal of European Public Policy, 8(6), 1032–1051. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760110098332

- Gravey, V., & Jordan, A. (2016). Does the European Union have a reverse gear? Policy dismantling in a hyperconsensual polity. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(8), 1180–1198. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1186208

- Graziano, P., & Vink, M. (Eds.). (2006). Europeanization: A handbook for a new research agenda. Palgrave.

- Griffiths, K. (2022, July 20). UK’s finance bill has confidential regulatory review power

- Hamre, E. F., & Wright, W. (2021, April). Brexit and the City: The impact so far. New Financial.

- HM Treasury. (2016, April). Analysis of the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hm-treasury-analysis-the-long-term-economic-impact-of-eu-membership-and-the-alternatives

- HM Treasury. (2021a, July). A new chapter for financial services. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-new-chapter-for-financial-services

- HM Treasury. (2021b, November). Financial services future regulatory framework review: Proposals for reform

- HM Treasury. (2021c, December). Review of the securitisation regulation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1040038/Securitisation_Regulation_Review.pdf

- HM Treasury. (2021d, July). Review of solvency II. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/998396/Solvency_II_Call_for_Evidence_Response.pdf

- HM Treasury. (2021e, March 26). Technical negotiations concluded on UK-EU Memorandum of Understanding. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/technical-negotiations-concluded-on-uk-eu-memorandum-of-understanding

- HM Treasury. (2022, December 9). Financial services: The Edinburgh reforms. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/financial-services-the-edinburgh-reforms

- Hopkin, J., & Shaw, K. A. (2016). Organized combat or structural advantage? The politics of inequality and the winner-take-all economy in the United Kingdom. Politics & Society, 44(3), 345–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329216655316

- Howarth, D., & Quaglia, L. (2018). Brexit and the battle for finance. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(8), 1118–36.

- Hula, K. (1999). Lobbying together. Georgetown University Press.

- Hungin, H., & James, S. (2019). Central bank reform and the politics of blame avoidance in the UK. New Political Economy, 24(3), 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1446924

- International Regulatory Strategy Group (IRSG). (2017, April 11). Mutual recognition—A basis for market access after Brexit.

- International Regulatory Strategy Group (IRSG). (2021, March 26). Response to consultation on financial services future regulatory framework. https://www.irsg.co.uk/publications/response-to-hm-treasury-financial-services-future-regulatory-framework-review-phase-ii-consultation/

- International Regulatory Strategy Group (IRSG). (2022, April 1). Response to HM Government financial services future regulatory framework: Proposals for reform. https://www.irsg.co.uk/publications/irsg-response-to-hm-government-financial-services-future-regulatory-framework-proposals-for-reform/

- James, S., Kassim, H., & Warren, T. (2021). From Big Bang to Brexit: The City of London and the discursive power of finance. Political Studies, 70(3), 719–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720985714

- James, S., & Quaglia, L. (2019). Brexit, the City and the contingent power of finance. New Political Economy, 24(2), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1484717

- James, S., & Quaglia, L. (2020). The UK and multi-level financial regulation: From post-crisis reform to Brexit. Oxford University Press.

- James, S., & Quaglia, L. (2021). Brexit and the political economy of euro-denominated clearing. Review of International Political Economy, 28(3), 505–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1699148

- Jordan, A., Bauer, M. W., & Green-Pedersen, C. (2013). Policy dismantling. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(5), 795–805.

- Kalaitzake, M. (2021). Brexit for finance? Structural interdependence as a source of financial political power within UK-EU withdrawal negotiations. Review of International Political Economy, 28(3), 479–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1734856

- Kalaitzake, M. (2022). Resilience in the City of London: The fate of UK financial services after Brexit. New Political Economy, 27(4), 610–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1994540

- Kleinman. (2022, July 2). Bailey opposes Treasury plot to overrule financial regulators. Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/bailey-opposes-treasury-plot-to-overrule-financial-regulators-12644238

- Knill, C. (2001). The Europeanisation of national administrations. Patterns of institutional persistence and change. Cambridge University Press.

- Knill, C., & Lehmkuhl, D. (2002). The national impact of European union regulatory policy: Three Europeanization mechanisms. European Journal of Political Research, 41(2), 255–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00012

- Lavery, S., McDaniel, S., & Schmid, D. (2019). Finance fragmented? Frankfurt and Paris as European financial centres after Brexit. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1502–1520. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1534876

- Leruth, B., Gänzle, S., & Trondal, J. (2019). Exploring differentiated disintegration in a Post-Brexit European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(5), 1013–1030. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12869

- McPhilemy, S., & Moschella, M. (2019). Central banks under stress: Reputation, accountability and regulatory coherence. Public Administration, 97(3), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12606

- Morales, A. (2021, January 11). Sunak sees Big Bang 2 for UK financial services industry. Bloomberg.

- Mügge, D. (2010). Widen the market, narrow the competition: Banker interests and the making of a European capital market. ECPR.

- Mügge, D. (Ed.). (2014). Europe and the governance of global finance. Oxford University Press.

- Noonan, L. (2022a, February 17). An upcoming UK investment bonanza. Financial Times.

- Noonan, L. (2022b, December 13). Bank of England warns Sunak over City deregulation drive. Financial Times.

- Page, E. C. (2003). Europeanization and the persistence of administrative systems. In J. Hayward, & A. Menon (Eds.), Governing Europe (pp. 162–176). Oxford University Press.

- Pagliari, S., & Young, K. L. (2014). Leveraged interests: Financial industry power and the role of private sector coalitions. Review of International Political Economy, 21(3), 575–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2013.819811

- Parker, G., Giles, C., Smith, I., & Thomas, D. (2022, July 17). Bank of England battle looms over plans for second “Big Bang”. Financial Times.

- Parker, G., & Smith, I. (2022, July 1). UK ministers clash with watchdog over insurance rules shake-up. Financial Times.

- Posner, E. (2009). Making rules for global finance: Transatlantic regulatory cooperation at the turn of the Millennium. International Organization, 63(4), 665–699. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818309990130

- Posner, E., & Véron, N. (2010). The EU and financial regulation: Power without purpose? Journal of European Public Policy, 17(3), 400–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501761003661950

- Quaglia, L. (2010). Governing financial services in the European Union. Routledge.

- Quaglia, L. (2014). The European Union and global financial regulation. Oxford University Press.

- Quaglia, L. (2015). The politics of ‘third country equivalence’ in post-crisis financial services regulation in the European Union. West European Politics, 38(1), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.920984

- Quaglia, L., & Spendzharova, A. (2019). Regulators and the quest for coherence in finance: The case of loss absorbing capacity for banks. Public Administration, 97(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12549

- Raagmaa, G., Kalvet, T., & Kasesalu, R. (2014). Europeanisation and de-Europeanisation of Estonian regional policy. European Planning Studies, 22(4), 775–95.

- Ranking, J. (2017, December 18). The UK cannot have a special deal for the City, says EU’s Brexit negotiator. The Guardian.

- Reuters. (2022, August 4). Bank of England says weakening regulators would undermine market reforms. Reuters.

- Reynolds, B. (2016). A Blueprint for Brexit: The future of global financial services and markets in the UK. Politeia.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2018). Brexit: Differentiated disintegration in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(8), 1154–1173. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1467954

- Schimmelfennig, F., & Sedelmeier, U. (2004). Governance by conditionality: EU rule transfer to the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 11(4), 661–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176042000248089

- Schmidt, V., & Radaelli, C. (2004). Policy change and discourse in Europe: Conceptual and methodological issues. West European Politics, 27(2), 183–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/0140238042000214874

- Simmons, B. A. (2001). The international politics of harmonization: The case of capital market regulation. International Organization, 55(3), 589–620. https://doi.org/10.1162/00208180152507560

- Singer, D. A. (2007). Regulating capital: Setting standards for the international financial system. Cornell University Press.

- Sunak, R. (2021). Speech delivered at Mansion House. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/mansion-house-speech-2021-rishi-sunak

- Thompson, H. (2017a). Inevitability and contingency: The political economy of Brexit. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117710431

- Thompson, H. (2017b). How the City of London lost at Brexit: A historical perspective. Economy and Society, 46(2), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2017.1359916

- Tomini, L., & Gürkan, S. (2021). Contesting the EU, contesting democracy and rule of law in Europe. In A. Lorenz, & L. H. Anders (Eds.), Illiberal trends and anti-EU politics in East Central Europe (pp. 285–300). Palgrave Macmillan.

- UK Government. (2017, January 17). The government’s negotiating objectives for exiting the EU: PM speech.

- Wolff, S., & Piquet, A. (2022). Post-Brexit Europeanization: Re-thinking the continuum of British policies, polity, and politics trajectories. Comparative European Politics, 20(5), 513–526. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-022-00293-6

- Wright, W., & Bierbaum, M. (2023, February). From Big Bang 2.0 to the Edinburgh reforms. New Financial.

- Young, K., & Pagliari, S. (2017). Capital united? Business unity in regulatory politics and the special place of finance. Regulation & Governance, 11(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12098

List of interviews

- 1. UK bank lobbyist, London, 14 June 2017

- 2. Financial trade association, London, 19 June 2017

- 3. UK bank lobbyist, London, 10 July 2017

- 4. Financial trade association, London, 18 July 2017

- 5. UK financial regulator, London, 23 October 2017

- 6. UK bank lobbyist, London, 15 February 2018

- 7. Financial legal professional, London, 16 April 2018

- 8. City of London official, London, 22 June 2022

- 9. Business lobbyist, London, 24 June 2022

- 10. Finance industry lobbyist, London, 4 July 2022

- 11. UK financial regulators (x 2), London, 8 August 2022