ABSTRACT

Several studies have investigated the variety of governance strategies adopted by European countries to cope with the Covid-19 pandemic. Some nations relied on a more liberal approach, based on recommendations and a lack of mandatory constraints; others trusted more top-down regulations and long-lasting restrictions. The feasibility and success of the different strategies also depend on the way in which policy-takers react. The article uses this exemplary policy case to propose a novel theoretical framework which maps the variety of policy-taking styles applying March and Olsen’s (2006) logics of conditionality and appropriateness. Using mobility data, it then employs the new typology to explore the diverse styles adopted by policy-takers reacting to anti-Covid workplace regulations in 29 European countries. The categories proposed can be applied also in different contexts, especially where policy success crucially depends on countless individual behaviours, and policy-makers need to choose the most effective mix of enforcement tools.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic hit Europe countries almost simultaneously at the beginning of 2020. While the threat was common, the policy reactions were more varied (Capano et al., Citation2020; Toshkov et al., Citation2022). Especially during the first months, due to its decentralised and voluntary approach, Sweden was an ‘outlier’ with respect to most other European countries, which adopted a more regulatory style based on lockdowns and strictly enforced restrictions (Petridou, Citation2020). Anders Tegnell, the now-famous Swedish state epidemiologist, explained in an interview the preconditions for the more liberal stance taken by his country in its anti-Covid regulations:

That was the tradition, it could be done voluntarily, and people are also listening to that because there is a high level of both respect and trust between the population and the government and the agencies. That’s why we could get quite a lot of impact on doing things on a voluntary basis. (Sayers, Citation2021)

The extent to which the Swedish policy actually diverged from that of other European countries has probably been exaggerated. While avoiding lockdowns and complete school closures were the cornerstones of the Swedish approach, the country partially off-set this strategy with other targeted regulations, so that, especially after the onset of the second wave of the pandemic, the overall stringency of its regulations was not so dissimilar from the average European level, and even greater than that of its Nordic neighbours.Footnote1

Nevertheless, there is a more important concern in the above quotation: the fact that certain types of policies and approaches can only be implemented in certain types of responsive environments, with policy-takers willing to cooperate with policy-makers to accomplish a shared desirable goal. Recommendations work better if citizens trust that they have been formulated for their own good, so that voluntary compliance substitutes the need for sticks or carrots. This cooperative style of policy reception is not necessarily exclusive to Sweden; rather, it is often recognised as being common to most Nordic countries, contributing to their good governance performance and well-being, and could possibly extend even elsewhere (Martela et al., Citation2020; Veggeland, Citation2020). Whether or not this civic attitude is the key to understanding the behavioural effects of country or regional anti-Covid policies is a matter that warrants empirical investigation.

Most importantly, this empirical task is an opportunity to conduct theoretical reflection on the central importance of considering policy-taking attitudes and behaviours when designing enforceable policies. The effectiveness of the mix of tools used by policy-makers also depends on the characteristics of the environment in which policies are to be implemented (Howlett, Citation2018). This is crucial for the implementation of many regulatory policies that, for a variety of reasons, would otherwise require costly enforcement strategies if not unfeasible control of the micro-behaviours of citizens.

By employing and fine-tuning the concept of policy style from the perspective of policy-takers (Richardson et al., Citation1982), we shall explore if some countries took advantage of people’s voluntary compliance in tackling the spread of the virus more than others, and if it is possible to identify systematically different styles of reacting to the restrictive policies implemented because of the pandemic. Methodologically speaking, the concept of policy style has been subject to mostly qualitative applications at the national or sectorial level. Instead, this study exploits the availability of community mobility data to analyse and systematically map the policy-taking styles of citizens in 29 European countries, comparing quantitatively their reactions to anti-Covid regulations. In so doing, this research also contributes to the growing body of literature that uses mobility information to explore the compliance with non-pharmaceutical interventions during the pandemic (Bargain & Aminjonov, Citation2020; Giuliani, Citation2022; Yarmol-Matusiak et al., Citation2021).

This article is organised as follows. It first reviews the recent resurgence in the use of the concept of policy style and of its application to the study of anti-Covid policies. Next, it explains why this approach should also include the behavioural responses of policy-takers, and proposes a theoretically-founded typology of those reactions. Finally, the study uses mobility data and regression models to identify the prevalent attitudes of policy-takers in the various European regions and countries, locating them within the above-mentioned typology of policy-taking styles. The conclusion reflects on the generalisability of the theoretical proposal, the potential origins of the different styles of policy-taking, and the limitations of the present empirical application.

Policy styles and Covid-19

In the book edited by Jeremy Richardson (Citation1982), the concept of policy style was conceived mostly as a national ‘way of doing things’. It was accordingly organised into six European national chapters, plus an introduction and a conclusion. Its theoretical framework identified two major dimensions: the government’s approach to problem-solving, which may be anticipatory or reactive, and its relationship with other actors, characterised by consensus rather than imposition. This gave rise to a loose typology, or a two-dimensional space, in which each prevalent national policy style could be roughly located.

Nordic countries, also due to an implicit institutional anchorage to Lijphart’s (Citation2012) consensual model of democracy, were most likely to appear in the quadrant characterised by inclusive and active problem-solving. Yet a rationalist consensus was believed to be embodied also in the prevalent (West) German style, and normative elements of negotiation, though with more reactive policy-making habits, were to be found in the United Kingdom, in spite of its Westminster democracy in which power is usually conceived to be hierarchically concentrated in the cabinet. A pluralistic notion of the national way of doing policies, with multiple actors involved, was not extraneous even to France, despite its ‘reputedly assertive (and technocratic) style of policy-making’ (Hayward, Citation1982), thus explicitly suggesting the existence of a dual policy style. Another dual style seemed to characterise the Netherlands, whose active-reactive policy-making depended on the political leaning of the cabinet, and exhibited sometimes a preference for negotiations, and sometimes more conflictual dynamics.

The prudence, if not ambiguity, that was present in the different national contributions to Richardson’s edited book should not come as a surprise. A more precise empirical application of the original framework was prevented by the fact that, at least at this level of analysis, the typology could not be mutually exclusive, with different policy processes that were to be classified in opposite types, or presented an inextricable mix of features traversing the proposed boundaries of the classification. The idea of distinctive national policy-making patterns was later extended beyond Western Europe (Howlett & Tosun, Citation2019b), taking stock of the limitations of the original framework and looking for a more operationalisable notion of policy style. Howlett and Tosun (Citation2019a) started by distinguishing the unit of the analysis – the behaviour of policy agents and the structural constraints imposed by institutions – and the level of the analysis – from the constitutional rules to lower-level procedures – and this helped them to link the original concept to that of political regimes. Their refined typology, built on the identification of the key policy actors and on the inclusiveness of decision-making, enabled them to extend Richardson’s exploration not only beyond Europe, but also beyond democratic regimes, while maintaining the focus on the prevalent national style.

The original proposers of the concept, as well as those who applied it to different countries, did not deny the possibility of sectorial, if not problem-specific styles, and explicitly recognised that the analysis should not be limited to the phase of policy formulation but include the execution phase as well. Thereafter, this idea was further extended, with the exploration of distinct styles for each phase of the policy process, from the agenda-setting to the implementation, to the evaluation stage (Howlett & Tosun, Citation2021; Tosun & Treib, Citation2018). The flourishing of style concepts for different moments and actors of the policy process was partially favoured by a different classification methodology. Compared to the original stylised top-down typology, some authors started to use bottom-up taxonomies, which, by clustering empirically similar dynamics and raising them to the status of ‘class’, made it possible to overcome the difficulties of operationalising the original dimensions, and their ambiguity in regard to the criteria of mutual exclusion (Smith, Citation2002).

One underdeveloped topic in that literature is the inclusion also of different patterns of policy-takers’ behaviour, whose consent, reluctance, opposition or compliance has only recently started to be recognised as a relevant factor in the choice of the appropriate mix of policy tools (Howlett, Citation2018; Howlett et al., Citation2020). The attitudes, propensities and behaviours of policy-takers – in a word their ‘style’ – 'feedback' on the feasibility and effectiveness of the instruments selected by policy-makers, contributing to the success or failure of the solution chosen.

More recently, the concept of policy style has been employed in the analyses of national responses to the common threat of the Covid-19 pandemic. What the institutional framework (Kuhlmann, Hellstrom, et al., Citation2021), partisan preferences (Toshkov et al., Citation2022), cultural orientation (Yan et al., Citation2020), and different forms of policy emulation (Givens & Mistur, Citation2021) could not directly explain, has been attributed to governmental and administrative capacities related to national policy-making styles. In fact, in front of the uncertainties and ambiguities of the emergency, resorting to the conventional repertoire and toolkit (Capano et al., Citation2020), and to traditional ‘ways of doing things’, could be a sensible response to the unprecedented challenge, and even an opportunity to consolidate or, conversely, change pre-existing governance patterns (Kuhlmann, Bouckaert, et al., Citation2021).

Zahariadis et al. (Citation2023, Citation2022) have been the first to adapt the original classification of policy-making styles, and then systematically employ the refined categories to survey the national responses to the pandemic in ten different political systems. Their updated typology still has two main dimensions. The pattern of administrative arrangement, operationalised as high or low administrative policy capacity, reformulates the original anticipatory-reactive dimension, while the inclusiveness of state-society relations takes the place of the consensus-imposition dimension. Intersecting the new axes produces four different styles – managerial, accommodative, adversarial, and administrative – whose policy effects in crisis situations like the pandemic are believed to depend on the level of political trust. The evidence provided in the national chapters of Zahariadis et al.’s edited volume mostly corroborates their comparative expectations, providing indications for further conceptual and empirical advances (Tosun, Citation2022). In particular, the inclusion of the perspective of policy takers – what Zahariadis et al. (Citation2023) call the ‘demand side’ of crisis response – is an important theoretical novelty.

Trust is relevant since it allows policy-makers to rely more on ‘carrots’ than on ‘sticks’ to enforce their public health decisions, and it has been often recognised as a crucial factor in boosting compliance and coping with the pandemic (Bargain & Aminjonov, Citation2020; Charron et al., Citation2022). However, in the proposed framework, trust is used mostly as an intervening variable between policy style and national strategy, and it would not be appropriate to employ it as the exclusive proxy for policy-takers’ behaviours. First, while there are relevant cross-country differences, trust varies also longitudinally, not least as a consequence of the successes and failures of the implemented policies: a feature which does not make it a good operationalisation for a national policy style (Esaiasson et al., Citation2021; Nielsen & Lindvall, Citation2021). Secondly, different types of trust may be relevant for inducing confidence in citizens behaviour. Institutional and political trust are already two different variables, but societal and interpersonal trust also affects compliance with public norms, and trust in health authorities and science was certainly relevant during the pandemic (Bengtsson & Brommesson, Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2021). Finally, trust has been found not to play a direct role in compliance, but to be conditional on other factors such as perceived risk, competence and information (Kestilä-Kekkonen et al., Citation2022; Seaton et al., Citation2020; Seyd & Bu, Citation2022). In sum, if the focus is directly on citizen’s behaviour with respect to policy implementation, in a bottom-up perspective, a different approach is needed.

Policy-taking styles

There are multiple ways in which policy-takers can react to policies. For the present analysis, we focus on two major dimensions of their responses. The first one refers to the possibility that citizens comply with the policy because they want to avoid the sanctions connected to non-conforming behaviours. Margaret Levi (Citation1997), in her four-category taxonomy of compliance/non-compliance, calls this attitude ‘opportunistic obedience’, which happens whenever the marginal benefits of compliance exceed the marginal costs.

The second behavioural dimension, on the contrary, assumes that citizens comply because they understand and share the aim of the policy itself, anticipating the actions necessary to achieve the desired outcome. Whereas in the former case, utility and the fear of the consequences of non-compliance guide citizens’ rational behaviours, in the latter case, their compliance derives from perceiving the policy as appropriate and from accepting its aims and procedures. This attitude resembles Levi’s ‘contingent consensus’, although it also comprises some elements of her ‘habitual conformity’, which does not require any rational evaluation of the policy and of its consequences (Levi, Citation1997, p. 19).Footnote2

The two dimensions broadly refer to the two institutional logics identified in a series of works by March and Olsen (Citation1989, Citation1995): the logic of consequentiality, and that of appropriateness. The former has a rational and individualistic foundation, with social actors deciding to pursue certain courses of action because of their expected utility, as a sort of optimisation exercise. The latter is characterised by the understanding of the social and policy situation, whose cognitive and normative components necessitate predefined reactions as appropriate responses. In a different tradition, Samuel Bowles (Citation2016, p. 91) refers to a similar distinction between deliberative and affective conducts: ‘deliberative processes are outcome based (in philosophical terms, “consequentialist”) and utilitarian, while affective processes support nonconsequentialist judgments (termed “deontological”) such as duty or the conformity of an action to a set of rules’.

These two dimensions are important for understanding policy-takers’ styles precisely because they reflect the different outlooks of citizens with respect to institutions like public norms and policies.

There is a great diversity in human motivation and modes of action. Behavior is driven by habit, emotion, coercion, and calculated expected utility, as well as interpretation of internalised rules and principles. [There is a] potential tension between the role- or identity-based logic of appropriateness and the preference-based consequential logic. (March & Olsen, Citation2006, p. 701)

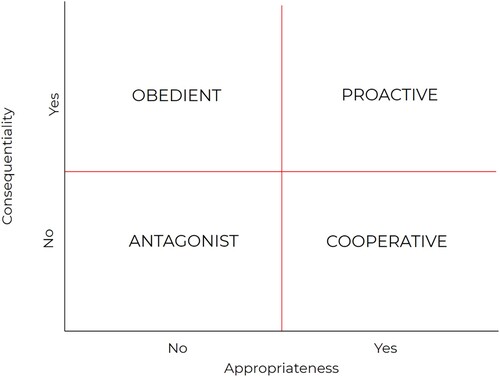

In the upper-left quadrant of , citizens obey for utilitarian reasons, rationally choosing to respect the norms in order to avoid the negative consequences of their infringement. In the opposite bottom-right quadrant, a cooperative style characterises the voluntary compliance with the policy, which is recognised as appropriate and normatively correct.Footnote4 The pragmatic combination of the two logics produces what we call a ‘proactive style’ of policy-taking, with pre-emption magnified by compliance with the rules and vice versa. In the bottom-left corner, non-compliant antagonistic behaviours oppose the policy as such and seek to avoid the sanctions entailed by its transgression.

This framework has features in common with some literature on compliance with EU policies, and in particular with those studies that identify several ‘worlds of compliance’ populated by different clusters of countries depending on their ‘typical modes of reacting to adaptation requirements’ due to EU directives and recommendations (Falkner et al., Citation2005, Citation2007). The logic of their ‘world of law observance’ resonates with the cooperative policy style proposed in ; the ‘world of domestic politics’, with its utilitarian bases, echoes some characteristics of the obedient style; and the ‘world of neglect’ is clearly similar to the antagonist style leading to lack of compliance. However, in that literature, the policy-takers are not citizens but states, adapting or otherwise to common EU policies, and their macro-cultural taxonomy has limited connections with the institutional dimensions used in the proposed framework. Nonetheless, it is interesting how similar issues and dynamics emerge whenever the focus is on the final stage of the policy process and considers the behavioural adaptations of those confronted by the choice among absorbing, respecting, or reacting to the aim of certain policies.

According to the initial quotation from the interview with Tegnell, Nordic countries, and Sweden in particular, should be placed in the right-hand side of the proposed typology, and more precisely in the cooperative pre-emptive quadrant. Apart from some stereotypes, and referring to the institutional logics described above, it is unclear which could be the prevalent policy-taking style of other regions or countries. While several studies have contrasted the diverse governance approaches to the pandemic, to our knowledge the same comparative perspective has not been systematically applied to the compliance side of the policy process. One possible way to fill this knowledge gap is to use mobility data, revealing how citizens reacted to the restrictions applied in different contexts and periods.

Compliance and mobility

One way to examine the reactions of policy-takers to anti-Covid non-pharmaceutical measures is to look directly at how they modified their behaviours, especially in regard to their mobility habits. After controlling for a set of relevant covariates, and since geographic response patterns cannot be attributed to consistent policy mixes, which tend to vary both cross-sectionally and longitudinally (Ceron et al., Citation2021), any behavioural difference compared to the pre-pandemic period should help revealing regional or country-specific styles.

Mobility data have been increasingly used during the pandemic to test a range of interesting aspects, such as the effectiveness of stay-at-home orders (Brodeur et al., Citation2021), the mediating role of political trust in compliance (Bargain & Aminjonov, Citation2020), or the drivers of economic slowdowns (Goolsbee & Syverson, Citation2021). However, to our knowledge, they have not been used to explore and map regional or national policy-taking styles.

We collected Google daily anonymised data that compared the number of visitors or the duration of presences in specific places like residential areas, transit stations, workplaces, retail areas, grocery markets and parks compared to their respective median value five weeks before the onset of the pandemic (Google, Citation2021). The focus is thus on change of movement habits, so that our measure already discounts different cross-country patterns of mobility.Footnote5 The period covered by the analysis extended from the beginning of the pandemic until the end of 2021, corresponding to almost 20,000 observations evenly divided for the 29 European countries for which mobility data were available.Footnote6

We decided to focus exclusively on the regulation of in-person work, and thus on the reduction in the number of people in workplaces. In this regard, Hale et al. (Citation2021) distinguish contexts without any regulation from those in which working from home is only recommended, cases in which some sectors or categories are required to shut down or work from home, and finally situations in which all non-essential workplaces are closed. We preferred to investigate the effects of that specific component of the stringency index, instead of the aggregated measure, for a series of reasons. First, because it perfectly matched the corresponding Google mobility measure concerning the presence in workplaces; secondly, because smart-working has been probably one of the most innovative features brought by the pandemic; thirdly, because working is a necessity, and the mobility in workplaces is less affected by environmental or geographical factors compared to transportation or mobility in blue–green spaces.

In general, workplace mobility is expected to be reduced by more stringent anti-Covid work regulations. This effect is driven by the logic of consequentiality, with mobility reductions proportional to the intensity of the restrictions. However, the logic of appropriateness may also condition that behavioural response, with decreases in mobility that cannot be attributed to the stringency of the policies or to the likelihood of sanctions, but which depend on the voluntary acknowledgement of the importance of reducing the chances of being infected and of spreading the virus. Thus, on controlling for the level of work restrictions, countries characterised by cooperative and pro-active policy-takers should have systematically less mobility in workplaces.

To explore these options empirically, we ran a series of panel regressions using the policy and behavioural data described above, and whose results are presented in .Footnote7 Using daily observations, the dependent variable was the reduction in mobility in workplaces measured by Google, while the main independent variable was the component of the stringency index concerning workplace restrictions, whose 100-point scale incorporated the possibility of differential sub-national regulations. Model 1 controlled only for the day of the week, to avoid the confounding effects of weekends. For this variable, the baseline was workplace attendance during Sundays, which should not have been particularly affected by the pandemic. In fact, all weekdays showed a relative decrease in mobility compared to this baseline, although the magnitude of the effect was considerably smaller for Saturdays. Estimating the decrease in workplace attendance at average levels of policy restrictions revealed that also Sundays experienced a mobility reduction around 6 per cent, so that the drop during weekdays ranged from 28 per cent on Wednesdays to 31 per cent on Mondays.

Table 1. Determinants of mobility in workplaces.

Moving to the covariate of interest, the stricter the anti-Covid work regulations, the larger the decrease in people going to their workplace: for each point increase in the index, there was an average loss of 0.28 per cent in workers’ presence in offices and firms. Considering that, in the two years covered by the analysis, the mean work regulation index was around 53 points, all other things being equal the coefficient corresponded to an average decrease in workers attendance of another 15 per cent. While this estimate reflects the utilitarian compliance driver, it is only an average effect that does not directly help in classifying the importance of the logic of consequentiality in different regions and countries. We will return to this task after considering the other two models in .

Model 2 included the regional differences, using South-European countries as the baseline. The leverage of work regulations was confirmed; but most importantly, the geographical dummy variables revealed that some regions – the Nordic countries as well as Ireland and the United Kingdom – had an over-reduction in workplace mobility that cannot be explained by the utilitarian logic of policy compliance. For the two former regions, one may surmise that policy-takers – citizens, as well as employers – opted for working from home not simply because of the restrictions of anti-Covid regulations, but because it was the appropriate course of action in those circumstances, combining in their cooperative behaviours safety with freedom of choice. West, East, and South-European countries did not have, relatively speaking, the same surplus of mobility reduction, and the average behaviours of their workers is explained better by their adaptation to the anti-Covid policy restrictions, i.e., by the logic of consequentiality.

The regional effects that are revealed by model 2 may, however, not only depend on policy-takers who autonomously decided to privilege working from home; they may also depend on other systemic or contingent elements characterising the different countries, economies and populations. This is what the third model controlled for by introducing a series of proxies representing potentially confounding factors.

Firstly, the reduced presence in the workplace may depend on other containment policies. Whilst general lockdowns also entail not going to work, so that the component of the stringency index regarding workplaces would be automatically modified in the case of stay-at-home orders, the same does not apply, for example, to school closures (Giuliani, Citation2023). However, any decision regarding children’s mandatory distance learning may possibly also affect their parents’ behaviours. The same applies to the other components of the stringency index (apart from the direct effect of work regulations). For this reason, we used the same procedure as adopted by Hale et al. (Citation2021) for their overall index by applying it to the remaining components, and then introduced into the third model the newly computed ‘other containment’ index to summarise the indirect effect on workplace mobility of those different containment policies.

Covid-related economic support, as again measured by the corresponding index formulated by Hale et al. (Citation2021), may also include incentives for smart working or compensations for any productivity loss. Thus, what model 2 interprets as appropriate national cooperative behaviours could in fact have been driven by utilitarian considerations dependent on the economic benefits decided by the respective governments. To avoid that misunderstanding, the index of economic support is included in the right-hand side of the equation.

On moving from policy concerns to socio-economic country attributes, it is clearly easier to opt for smart-working in the case of some occupations rather than others. Switching to working from home is relatively easier for administrative and service jobs, whereas it is almost impossible for blue-collar work and other occupations. Including the size of the service sector in each country, as measured by its share of the GDP estimated by the World Bank, highlights the different options available to the tertiary sector compared to the manufacturing and agricultural ones. Other socio-economic characteristics have been presumed to impact on the pandemic dynamics. Hence the third model included as standard controls the size of the country measured by the logarithm of the population, the percentage of inhabitants at risk of poverty and social exclusion who were supposed to have greater constraints, estimated on the eve of the pandemic by Eurostat, the demographic density, and a measure of urbanisation (the percentage of citizens living in the capital).

Finally, the spread of emotions and attitudes such as fear and trust has also been found to affect voluntary mobility restraints and, more generally, support for the restriction of liberties during the pandemic (Bargain & Aminjonov, Citation2020; Clark et al., Citation2020; Goolsbee & Syverson, Citation2021; Vasilopoulos et al., Citation2022). As a macro proxy for fear, which was presumed to induce self-restraint autonomously, we used the incidence of new cases, and more precisely the smoothed value of new certified Covid cases per thousand people estimated within the Coronavirus project ‘Our World in Data’ (Ritchie et al., Citation2020). Trust in government, which should facilitate a positive reaction to simple recommendations, was measured using Eurobarometer and OECD surveys. As the last control variable, a time measure accounted for the fact that restrictions may become increasingly intolerable and disobeyed with the passage of weeks and months.

The inclusion of this set of covariates increased the explained variance of the third model, although not all these factors turned out to be statistically significant. Different containment and support policies contribute to the reduction of workplace mobility, but work regulation is still highly significant, although its coefficient now has a smaller magnitude. Having a larger service sector favours working from home, while the larger the size of the country, the less mobility restrictions are observed. Instead, density and urbanisation, the share of the population at risk of poverty, and also trust in government, do not contribute to workplace mobility changes in one direction or another. Finally, keeping policies constant, peaks of infections boosted working from home to a highly significant extent, whereas the duration of the pandemic gradually eroded that positive disposition, marginally restoring the usual work habits.

However, most important for the analysis of policy-taking styles is that geographical dummies continue to appear, or become, highly significant even after keeping constant all the newly introduced potentially confounding covariates. In Nordic countries there remains a systematic excess of voluntary reduction in workplace mobility, with the gap separating those nations from Ireland and the United Kingdom becoming smaller. West-European countries, too, had in model 3 a systematically higher rate of working from home compared to South-European countries, but the magnitude and the statistical significance of that fixed effect were smaller than in the other two regions. Only the dummy variable comparing Eastern to Southern Europe remained insignificant, confirming that, in those regions, policy-takers’ behaviours are determined more by utilitarian compliance with the norms than by voluntary support for their aims.

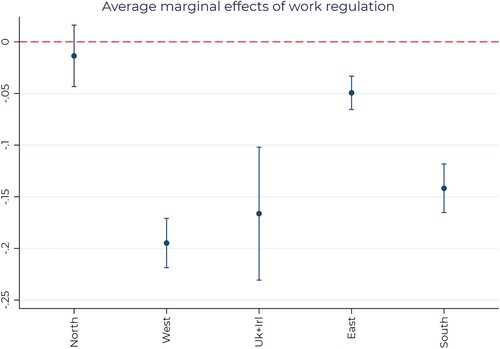

While these regional dummy variables, i.e., the average effects on mobility for constant levels of policy restrictions, can be interpreted as proxies for the logic of appropriateness described in the theoretical section, interacting them with the policies yielded the varying marginal effect of constraints on mobility for each different region, proxies for the rational logic of consequentiality. In the case of interaction models, methodological good practices suggest not commenting on the coefficients but directly plotting the marginal effects of the covariate of interest at the appropriate values of the conditional variable, as is done here in .

Put briefly, the marginal effects plotted in reveal the extent to which policy-takers changed their behaviours because of the containment regulations, i.e., following an utilitarian logic of consequentiality. The empirical evidence shows that, in this case, Nordic citizens did not behave differently because of more restrictive policies; the marginal effect of workplace restrictions did not directly affect their choices once the effect of all the other covariates is discounted. Rather, they most likely did so because they had already voluntarily interiorised the recommendations, as displayed earlier by their surplus change in mobility habits. By contrast, West-European citizens complied with work restrictions more than others, while in the other regions, already characterised by very different degrees of voluntarism, citizens assumed intermediate policy-taking attitudes.

A country perspective

From the analyses above, and attributing an average type of policy-taking to each region, it seems confirmed that Nordic countries are characterised by a cooperative style, while the UK and Ireland exhibit more a pro-active one, mixing the two institutional logics: proportionally reacting to the constraints as well as showing some extra, non-policy-explained reduction in workplace mobility. No region can be considered to have antagonistic policy-takers, although Eastern countries are probably closer to that type, while Southern and Western Europe can be placed close to the obedient quadrant, with less voluntary cooperation than forced compliance.

It would have been possible to further detail the combination of the two logics guiding the policy-taking styles in the different European regions, but, having now clarified the empirical research strategy, it is preferable to shift the analysis to the country level. The effects described above represent only regional averages, while it is possible to replicate the same research design using country dummies for the fixed and the interaction effects. Instead of reporting all the models, which can be easily replicated with the dataset and code provided, we directly plotted the coefficients of interest, together with their confidence intervals, on the proposed typology of policy-taking.

Because of the collinearity between some of the time-nonvarying controls included in the analysis and the country fixed-effects, we had to exclude the first one from our models. However, it is still possible that those factors exercised some differential impact on some of the changes in mobility that here we directly attribute to consequentiality and appropriateness. In the online appendix we propose a slightly more elaborate research design to overcome this limitation, showing that the map plotted below remains mostly unaffected by the different control strategy.

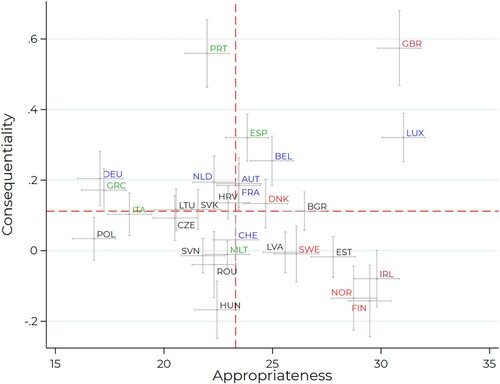

On the x-axis of , representing appropriateness, there are the expected country reductions in workplace mobility computed after the panel regression with country fixed effects: higher values represent larger reductions in mobility. Plotted on the y-axis, representing consequentiality, are the marginal effects on workplace mobility of a one-point increase in workplace regulations: again, higher values represent larger reductions. The red reference lines are located at the median values for each dimension, so that each country’s position should be interpreted as relative to that benchmark more than in absolute terms.

When unpacking the regional averages starting with the Nordic countries, three of them – Sweden, Norway, and Finland – are confirmed to be located in the quadrant representing a cooperative policy-taking style. Denmark is characterised by slightly less voluntaristic behaviours and a more elastic reaction to work regulation; and although it does belong to the upper right quadrant, it is not far from its Scandinavian neighbours. On the one hand, this confirms that Nordic citizens tended to cooperate with anti-Covid recommendations without stricter obligations being necessary. On the other hand, this is not their exclusive feature, and Sweden is not really the champion of those behaviours, as the initial Tegnell quotation seemed to imply. Several other, also unexpected, countries are characterised by such a pre-emptive style, or belong to the right panel of the graph in which voluntarism can be magnified by a more active compliance with any stricter regulation. Amongst them, for example, are two Baltic countries, Estonia and Latvia, plus an East-European one, Bulgaria. Irish policy-takers followed this prototype of cooperative attitude, while the United Kingdom turned out to be the clearest example of proactive style.

Western Europe is certainly very heterogeneous on the x-axis, with Luxembourg being similar to the United Kingdom – its small size being already controlled for in the regression model – Germany and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands characterised by an obedient style of policy-taking, and Switzerland, France and Austria with median levels of appropriateness and also a close-to-median amount of consequentiality. Southern Europe, on the contrary, is mostly differentiated on the y-axis, with a high utilitarian and obedient logic for Portugal, the opposite for Malta, and the other countries somewhere in between, but with Greece and Italy with low levels of appropriateness, while Spain shows relatively higher levels of pro-activism. Finally, compared to the other regions, the policy-taking behaviours of East-European citizens seem less determined by policy constraints – they are mostly located in the bottom part of the plot – and mix attitudes in terms of cooperation.

Because of the construction of the plot, with positions relative to the respective median values on each dimension, each portion of the graph is populated by some countries, including the antagonistic quadrant, which contains countries like Poland, Slovenia and Hungary. However, this does not mean that in those nations there has not been any reduction in mobility, either as consequence of containment policies or as self-decision; rather, it means that the magnitudes of those reactions were systematically lower than elsewhere, as highlighted also by the confidence intervals close to the respective country labels. At the same time, while there are clear examples of the prototypes of cooperative and pro-active policy-taking – Finland and the United Kingdom, respectively – this does not happen for the other two quadrants, which comprise a range of countries, but not one of them neatly in the corner of the respective quadrant.

Conclusion

Policy-taking affects the final implementation and performance of public policies. As suggested already by Levi (Citation1997, p. 17), ‘compliance represents a behavioural response of citizens that is likely to have an effect on the substance of government policy’, with different compliance dynamics affecting backwards the choice of policy instruments in different contexts. At the same time, the effectiveness of similar policy tools crucially depends on the environment in which they are applied, and this also because of the different responses of policy-takers. Whilst this claim should not be overstated, leaving no steering capacities to policy-makers, it is evident that, in many circumstances, counting or otherwise on the cooperation of the final target population of a policy can make a large difference.

In its decision not to rely on more coercive means, the Swedish Public Health Agency was probably aware of what it could expect in terms of adherence to its recommendations, with the national political culture and public trust furnishing the appropriate environment for a more liberal anti-Covid strategy. While ‘nudging’ turned out to be insufficient (Gordon et al., Citation2021; Pierre, Citation2020), our analysis confirmed that the cooperation of policy-takers was an important component of Swedish and, more generally, Nordic policy dynamics. On a more general note, other scholars recognise that little ‘is known about how compliant citizens have been with specific government policies, and why, during the pandemic’ (Anderson & Hobolt, Citation2023, p. 302). While a comprehensive understanding of compliance dynamics cannot avoid an in-depth investigation of different policy interventions in different contexts, the comparative design of our research helps move beyond any idiosyncratic understanding of specific country studies, locating each nation’s response model within the wider European context.

This analysis fits into the broad field of governance studies investigating the importance of the web of relationships linking public and private subjects. More specifically, it contributes to the recent revival in the study of policy-making styles, combining Richardson’s original intuition with the different phases of the policy process and of its multiple protagonists (Howlett & Tosun, Citation2021). In that recent literature, which has also made an important contribution to the analysis of national responses to the Covid-19 emergency (Zahariadis et al., Citation2022), there was still a gap concerning policy-taking styles during the implementation stage. In this regard, this article has first proposed a typology solidly based on March & Olsen’s (Citation2006) institutional logics, and then, taking advantage of Google mobility data, empirically mapped the styles with which policy-takers have reacted to anti-Covid work regulations in 29 European countries.

Mobility data have been used for many different purposes in studies on the pandemic’s dynamics, but to our knowledge this is the first time that they have been employed to investigate policy-taking styles within a new coherent framework. Policy styles are usually approached using a qualitative and interpretative approach, while here we have operationalised the dimensions of our typology by profiting from the coefficients of a series of panel regressions. This has enabled us to estimate the average policy-takers’ styles, together with the confidence intervals of that national position. One limitation of this empirical approach is that it is very much policy-specific, and while the typology as such can be applied to other sectors and situations, its operationalisation would require a different research design. Furthermore, although the research reported in this article depended on the measurement of a series of micro-individual behaviours, the analysis is clearly situated at the macro-level, as required by the same conceptualisation of a national style of policy-taking.

Reflecting on the origins of the diverse approaches shown by policy-takers in different contexts goes clearly beyond the scope of this work, and represents an interesting research avenue for future research. For the moment, we can only speculate about the range of potential causes and circumstances that have favoured the emergence of different styles of policy taking. Starting from the macro-level and proceeding towards more specific or micro-founded approaches, it is possible to identify, in abstract terms, three different explanatory scenarios.

The first scenario refers to a set of broad cultural predispositions, with policy-taking styles been rooted in some persistent characterising trait of a society. It is possible to date back this approach to the works of Alexis de Tocqueville (Citation1835), in which the self-governing democratic capacities of the North-Americans also relied on what he called the ‘habits of the hearts and minds’, which echoes the two dimensions – appropriateness and consequentiality, affective and utilitarian – that originate our typology. Within the field of public policy, a cultural turn has been advocated, amongst others, by Aaron Wildavsky, who took stock from his previous work on risk perception in different societies to advance a theory of preference formation (Douglas & Wildavsky, Citation1982). Preferences and attitudes are endogenously produced through continuous social interactions, so that ‘when individuals make important decisions, these choices are simultaneously choices of culture-shared values legitimating different patterns of social practice’ (Wildavsky, Citation1987, p. 5). Without conjecturing further around the possible overlaps between his fourfold cultural categorisation and our typology, this approach posits that ‘culture matters’ for many different political interactions, including the relationship between citizens and norms (Ellis & Thompson, Citation1997).

This perspective allows very limited space for longitudinal cultural changes (Inglehart & Baker, Citation2000), and thus finds many difficulties in accommodating the idea of some, even slow-moving, transformations of policy styles (Richardson, Citation2022). A more flexible scenario could assume that the approach to policy-taking somehow mirrors the style of policy-making. For example, cooperative attitudes could be elicited by a more inclusive policy-making, while utilitarian reactions could be fostered by the lack of any anticipatory problem-solving. In fact, in the field of anti-Covid policies, there is a certain match between the quantitative results of our policy-taking analysis and the qualitative exploration of policy-making in the four European countries covered by the work of Zahariadis et al. (Citation2022). Greece’s reactive impositional style (Zahariadis & Karokis-Mavrikos, Citation2022) seems to be the other side of the coin of the obedient and instrumental attitudes reported in . The British adversarial centrifugal style (Exadaktylos, Citation2022) has relied on a mix of consequentiality and appropriateness in its alternating fortunes in curbing the pandemic. The comparatively high average level of trust in the Nordic countries is reflected in their shared cooperative policy-taking style depicted in , and in the inclusiveness of their policy-making, which however coexists with a differentiated approach to the pandemic: centripetal in the case of Norway (Sparf, Citation2022), and decentralised in the case of Sweden (Petridou, Citation2022).

A third explanatory scenario draws on a large set of experimental analyses that demonstrate that unrelated individuals do not exclusively follow the maximisation of their self-interest, but are capable of making altruistic contributions to the production of public goods even when it is a costly behaviour (Bowles & Polanía-Reyes, Citation2012). However, altruism, ethical preferences and other social motivations are not fixed or exogenously given, but can expand or shrink depending on how policies are framed. For example, incentives can counterintuitively reduce cooperative behaviour and compliance by ‘crowding out’ social preferences and not being able to substitute them with a sufficient amount of utilitarian conducts. While ‘putting a price on every human activity erodes certain moral and civic goods worth caring’ (Sandel, Citation2013, p. 121), strict regulations as well risk to produce the same effect, with mandatory behaviours reducing the willingness to comply voluntarily (Schmelz & Bowles, Citation2022). The reactions of citizens to certain policies, the balance between consequentiality and appropriateness, thus depends on how those policies combine incentives and ethical guides. But even for the same type of mix there could exist systematically different reactions depending on the context in which the policy is implemented. Experimental studies seem to confirm that countries characterised by civic culture and rule of law are those in which citizens are more likely to react cooperatively to the same kind of stimulus (Bowles, Citation2016; Herrmann et al., Citation2008), and in the online appendix we offer some evidence that also the coordinates of our map of policy styles are partially associated to those factors.

The relevance of the focus on policy-takers extends well beyond the specific case of anti-Covid policies. It is crucial for a large number of policy measures whose success strategically depends on a series of micro-behavioural adaptations that are difficult to monitor, expensive to supervise, and often inconvenient to enforce systematically. Sorting household garbage, respecting speed and parking limits, obeying smoking bans, paying bus fares, and a myriad of other individual actions are dictated by policy prescriptions typically associated with specific control measures and economic sanctions. However, the specific balance between fines and moral suasion, between reliance on monitoring activities or public reprobation is a delicate choice of which any national or local policy-maker is well aware.

The sensitivity to different mixes of enforcing instruments has a lot to do with the logics of conditionality and appropriateness on which we have based the proposed typology of policy-taking styles, and it says a great deal about the feasibility and effectiveness of the varying combination of policy tools. Furthermore, also the fine-tuning of one single measure is not extraneous to those logics. Consider information, for example: survey and experimental data have shown that the spread of more information increased compliance with the mask mandate in the United Kingdom during the pandemic (Anderson & Hobolt, Citation2023). Yet the content and type of the evidence provided may trigger diverse reactions in different social environments. Increasing the awareness of individual risks may be the purpose of providing information where consequentiality characterises policy-taking behaviours, whereas preserving collective wellbeing and the health of the community could be the focus of public campaigns where appropriateness prevails.

These types of concern help reflect on the behaviours of European citizens in a period in which most democratic countries have lifted mandatory constraints. The necessity to enter a new phase of normalcy, in which citizens will have to cohabit with the virus without policy-makers imposing lockdowns, strict regulations and sanctions, requires widespread awareness of the consequences of non-cooperative behaviour. Past experiences seem to indicate that policy-takers will react differently to the freedoms that they have regained.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (616.7 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors and the three anonymous reviewers for their challenging comments. I may have not been able to accommodate all of their requests, but their suggestions have been invaluable in broadening my perspective even beyond the present paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The overall average of the Swedish daily stringency index of anti-Covid policies for the whole of 2020 and 2021 was equal to 51.6, and ranged on the 100-point scale from a minimum of 5.6 to a maximum of 69.4. For Norway the average was 48.8, for Denmark 50.1 and for Finland 43.6 (Hale et al., Citation2021).

2 The two rationales were well exemplified in a political exchange that happened in Westminster in September 2020. During a debate on Covid-19, Prime Minister Boris Johnson was criticized regarding the inefficiency of the British ‘test and trace’ anti-Covid policy compared to the German and Italian one. He answered that ‘there is an important difference between our country and many other countries around the world: our country is a freedom-loving country. (…) It is very difficult to ask the British population uniformly to obey guidelines (…). What we are saying today is that collectively, the way to do that is for us all to follow the guidelines’ (Hansard, House of Commons, 22 September 2020, vol. 680, col. 814). There is a subtle but important difference between the two words in italics, which echo our understanding of March & Olsen’s (Citation2006) institutional logics.

3 The coexistence of multiple institutional logics has been recently discussed also by Michel et al. (Citation2022), although in their analysis the interplay of separate logics depends on the possibility that multiple actors have different understandings of their role in the policy process.

4 This attitude is the precondition for any effort of ‘collaborative governance’ (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007; Emerson et al., Citation2011), whose theoretical framework usually focuses on political and administrative actors up to street-level bureaucrats, but only marginally includes citizens-state interactions (Jakobsen et al., Citation2019).

5 When we refer to mobility habits, our only concern is the overall level of movements, and we cannot discriminate between different means of transport. Where possible, many citizens have probably modified also the latter during the pandemic, but that alone would not affect the overall permanence at the workplace, which is the quantity captured by Google data and sufficient for our research design.

6 The list of 29 European nations comprises Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

7 A Hausman test confirmed that random effects were to be preferred over fixed effects, while a Breusch and Pagan test showed that they were also to be preferred over a standard OLS regression. Similar results were obtained also using panel-corrected standard errors.

References

- Anderson, C. J., & Hobolt, S. B. (2023). Creating compliance in crisis: Messages, messengers, and masking up in Britain. West European Politics, 46(2), 300–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2091863

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Bargain, O., & Aminjonov, U. (2020). Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics, 192, 104316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316

- Bengtsson, R., & Brommesson, D. (2022). Institutional trust and emergency preparedness: Perceptions of Covid 19 crisis management in Sweden. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 30(4), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12391

- Bowles, S. (2016). The moral economy. Why good incentives are no substitute for good citizens. Yale University Press.

- Bowles, S., & Polanía-Reyes, S. (2012). Economic incentives and social preferences: Substitutes or complements? Journal of Economic Literature, 50(2), 368–425. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.2.368

- Brodeur, A., Grigoryeva, I., & Kattan, L. (2021). Stay-at-home orders, social distancing, and trust. Journal of Population Economics, 34(4), 1321–1354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00848-z

- Capano, G., Howlett, M., Jarvis, D. S. L., Ramesh, M., & Goyal, N. (2020). Mobilizing policy (in)capacity to fight COVID-19: Understanding variations in state responses. Policy and Society, 39(3), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1787628

- Ceron, M., Palermo, C. M., & Grechi, D. (2021). Covid-19 response models and divergences within the EU: A health dis-union. Statistics, Politics and Policy, 12(2), 219–268. https://doi.org/10.1515/spp-2021-0003

- Charron, N., Lapuente, V., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2022). Uncooperative society, uncooperative politics or both? Trust, polarization, populism and COVID-19 deaths across European regions. European Journal of Political Research, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12529

- Clark, C., Davila, A., Regis, M., & Kraus, S. (2020). Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: An international investigation. Global Transitions, 2, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003

- Douglas, M., & Wildavsky, A. B. (1982). Risk and culture. An essay on the selection of technological and environmental dangers. University of California Press.

- Ellis, R. J., & Thompson, M.1997). Culture matters. Essays in honor of Aaron Wildavsky. Westview Press. https://archive.org/details/culturematterses0000unse/page/n5/mode/2up.

- Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., & Balogh, S. (2011). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur011

- Esaiasson, P., Sohlberg, J., Ghersetti, M., & Johansson, B. (2021). How the coronavirus crisis affects citizen trust in institutions and in unknown others: Evidence from ‘the Swedish experiment’. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 748–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12419

- Exadaktylos, T. (2022). Of “heard immunity” and inoculation investment: The British response to Covid-19. In N. Zahariadis, E. Petridou, T. Exadaktylos, & J. Sparf (Eds.), Policy styles and trust in the age of pandemics. Global threat, national responses (pp. 157–172). Routledge.

- Falkner, G., Hartlapp, M., & Treib, O. (2007). Worlds of compliance: Why leading approaches to European Union implementation are only ‘sometimes-true theories’. European Journal of Political Research, 46(3), 395–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00703.x

- Falkner, G., Treib, O., Hartlapp, M., & Leiber, S. (2005). Complying with Europe. EU harmonisation and soft law in the member states. Cambridge University Press.

- Giuliani, M. (2022). Complying with anti-COVID policies. Subnational variations and their correlates. Italian Journal of Public Policy, 17(2), 241–268. https://www.rivisteweb.it/doi/10 .1483/104976.

- Giuliani, M. (2023). COVID-19 counterfactual evidence. Estimating the effects of school closures. Policy Studies, 44(1), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2022.2103527

- Givens, J. W., & Mistur, E. (2021). The sincerest form of flattery: Nationalist emulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 26(1), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09702-7

- Google, L. L. C. (2021). Google COVID-19 community mobility reports. Retrieved November 15, 2021 from https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/.

- Goolsbee, A., & Syverson, C. (2021). Fear, lockdown, and diversion: Comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020. Journal of Public Economics, 193, 104311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104311

- Gordon, D. V., Grafton, R. Q., & Steinshamn, S. I. (2021). Cross-country effects and policy responses to COVID-19 in 2020: The Nordic countries. Economic Analysis and Policy, 71, 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2021.04.015

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Majumdar, S., & Tatlow, H. (2021). A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behaviour, 5(4), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8

- Hayward, J. (1982). Mobilising private interests in the service of public ambitions: The salient element in the dual French policy style? In J. Richardson (Ed.), Policy styles in Western Europe (pp. 111–140). George Allen & Unwin.

- Herrmann, B., Thöni, C., & Gächter, S. (2008). Antisocial punishment across societies. Science, 319(5868), 1362–1367. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1153808

- Howlett, M. (2018). Matching policy tools and their targets: Beyond nudges and utility maximisation in policy design. Policy & Politics, 46(1), 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557317(15053060139376

- Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., & Capano, G. (2020). Policy-makers, policy-takers and policy tools: Dealing with behaviourial issues in policy design. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 22(6), 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2020.1774367

- Howlett, M., & Tosun, J. (2019a). Policy styles. A new approach. In M. Howlett, & J. Tosun (Eds.), Policy styles and policy-making. Exploring the linkages (pp. 3–21). Routledge.

- Howlett, M., & Tosun, J. (Eds.). (2019b). Policy styles and policy-making. Exploring the linkages. Routledge.

- Howlett, M., & Tosun, J. (Eds.). (2021). The Routledge handbook of policy styles. Routledge.

- Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657288

- Jakobsen, M., James, O., Moynihan, D., & Nabatchi, T. (2019). JPART virtual issue on citizen-state interactions in public administration research. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(4), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muw031

- Kestilä-Kekkonen, E., Koivula, A., & Tiihonen, A. (2022). When trust is not enough. A longitudinal analysis of political trust and political competence during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Finland. European Political Science Review, 14(3), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1755773922000224

- Kuhlmann, S., Bouckaert, G., Galli, D., Reiter, R., & Van Hecke, S. (2021). Opportunity management of the COVID-19 pandemic: Testing the crisis from a global perspective. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 87(3), 497–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852321992102

- Kuhlmann, S., Hellstrom, M., Ramberg, U., & Reiter, R. (2021). Tracing divergence in crisis governance: Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in France, Germany and Sweden compared. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 87(3), 556–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852320979359

- Levi, M. (1997). Consent, dissent and patriotism. Cambridge University Press.

- Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of democracy. Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. Yale University Press.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions. The organizational basis of politics. Free Press.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1995). Democratic governance. Free Press.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (2006). The logic of appropriateness. In M. Moran, M. Rein, & R. E. Goodin (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public policy (pp. 689–708). Oxford University Press.

- Martela, F., Greve, B., Rohstein, B., & Saari, J. (2020). The Nordic exceptionalism: What explains why the Nordic countries are constantly among the happiest in the world. In J. F. Helliwell, R. Layard, J. Sachs, & J.-E. De Neve (Eds.), World happiness report 2020. Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

- Michel, C. L., Meza, O. D., & Cejudo, G. M. (2022). Interacting institutional logics in policy implementation. Governance, 35(2), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12596

- Nielsen, J. H., & Lindvall, J. (2021). Trust in government in Sweden and Denmark during the COVID-19 epidemic. West European Politics, 44(5-6), 1180–1204. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1909964

- Petridou, E. (2020). Politics and administration in times of crisis: Explaining the Swedish response to the COVID-19 crisis. European Policy Analysis, 6(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1095

- Petridou, E. (2022). Following the public health agency’s guidelines: The Swedish approach to the Covid-19 pandemic. In N. Zahariadis, E. Petridou, T. Exadaktylos, & J. Sparf (Eds.), Policy styles and trust in the age of pandemics. Global threat, national responses (pp. 211–228). Routledge.

- Pierre, J. (2020). Nudges against pandemics: Sweden’s COVID-19 containment strategy in perspective. Policy and Society, 39(3), 478–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1783787

- Richardson, J. (Ed.). (1982). Policy styles in Western Europe. George Allen & Unwin.

- Richardson, J. (2022). The study of policy style: Reflections on a simple idea. In P. Graziano & J. Tosun (Eds.), Elgar encyclopedia of European union public policy (pp. 337–346). Edward Elgar.

- Richardson, J., Gustafsson, G., & Jordan, G. (1982). The concept of policy style. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Policy styles in Western Europe (pp. 1–16). George Allen & Unwin.

- Ritchie, H., Mathieu, E., Rodés-Guirao, L., Appel, C., Giattino, C., Ortiz-Ospina, E., Hasell, J., Macdonald, B., Beltekian, D., & Roser, M. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus.

- Robinson, S. E., Ripberger, J. T., Gupta, K., Ross, J. A., Fox, A. S., Jenkins-Smith, H. C., & Silva, C. L. (2021). The relevance and operations of political trust in the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration Review, 81(6), 1110–1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13333

- Sandel, M. J. (2013). Market reasoning as moral reasoning: Why economists should re-engage with political philosophy. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(4), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.27.4.121

- Sayers, F. (2021). Anders Tegnell: Sweden won the argument on Covid. Unheard. https://bit.ly/3AJZdKy.

- Schmelz, K., & Bowles, S. (2022). Opposition to voluntary and mandated COVID-19 vaccination as a dynamic process: Evidence and policy implications of changing beliefs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(13), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2118721119

- Seaton, J., Sippett, A., & Ben, W. (2020). Fact checking and information in the age of Covid. Political Quarterly, 91(3), 578–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923x.12910

- Seyd, B., & Bu, F. (2022). Perceived risk crowds out trust? Trust and public compliance with coronavirus restrictions over the course of the pandemic. European Political Science Review, 14(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1755773922000078

- Smith, K. B. (2002). Typologies, taxonomies, and the benefits of policy classification. Policy Studies Journal, 30(3), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2002.tb02153.x

- Sparf, J. (2022). Norwegian corporatism: A centripetal national response to the pandemic. In N. Zahariadis, E. Petridou, T. Exadaktylos, & J. Sparf (Eds.), Policy styles and trust in the age of pandemics. Global threat, national responses (pp. 119–132). Routledge.

- Tocqueville, A. D. (1835). Democracy in America (2010 ed.). Liberty fund.

- Toshkov, D., Carroll, B., & Yesilkagit, K. (2022). Government capacity, societal trust or party preferences: What accounts for the variety of national policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe? Journal of European Public Policy, 29(7), 1009–1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1928270

- Tosun, J. (2022). Different governments, different responses to the Covid-19 pandemic? Concluding remarks and the way forward. In N. Zahariadis, E. Petridou, T. Exadaktylos, & J. Sparf (Eds.), Policy styles and trust in the age of pandemics. Global threat, national responses (pp. 231–249). Routledge.

- Tosun, J., & Treib, O. (2018). Linking policy design and implementation styles. In M. Howlett, & I. Mukherjee (Eds.), Routledge handbook of policy design (pp. 316–330). Routledge.

- Vasilopoulos, P., McAvay, H., Brouard, S., & Foucault, M. (2022). Emotions, governmental trust and support for the restriction of civil liberties during the covid-19 pandemic. European Journal of Political Research, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12513

- Veggeland, N. (2020). Democratic governance in Scandinavia. Developments and challenges for the regulatory state. Springer.

- Wildavsky, A. B. (1987). Choosing preferences by constructing institutions: A cultural theory of preference formation. The American Political Science Review, 81(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1960776

- Yan, B., Zhang, X. M., Wu, L., Zhu, H., & Chen, B. (2020). Why do countries respond differently to COVID-19? A comparative study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. American Review of Public Administration, 50(6-7), 762–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942445

- Yarmol-Matusiak, E. A., Cipriano, L. E., & Stranges, S. (2021). A comparison of COVID-19 epidemiological indicators in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 49(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820980264

- Zahariadis, N., & Karokis-Mavrikos, V. (2022). Centralization and lockdown: The Greek response. In N. Zahariadis, E. Petridou, T. Exadaktylos, & J. Sparf (Eds.), Policy styles and trust in the age of pandemics. Global threat, national responses (pp. 79–99). Routledge.

- Zahariadis, N., Petridou, E., Exadaktylos, T., & Sparf, J. (Eds.). (2022). Policy styles and trust in the age of pandemics. Global threat, national responses. Routledge.

- Zahariadis, N., Petridou, E., Exadaktylos, T., & Sparf, J. (2023). Policy styles and political trust in Europe’s national responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Policy Studies, 44(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2021.2019211