ABSTRACT

With growing numbers of forcibly displaced people and their tendency to spatially cluster, destination countries around the world consider dispersing them over their territory. While the egocentric not-in-my-back-yard syndrome (NIMBYism) predicts that dispersion will spark a public backlash, sociotropic considerations and appeals to civic fairness predict the contrary. I theorise that the institutional set-up determines which force prevails. Although the local proximity of refugees triggers public opposition, it can be substantially countered by tighter regulation on refugee dispersion. Setting clear guiding rules, such as an upper limit or proportional allocation can enhance both burden-sharing in the accommodation of refugees and public support for their incorporation. Evidence from survey experiments conducted in Norway and Israel supports these theoretical accounts. The findings have implications for understanding how countries can mitigate public backlash against immigrants and refugees while maintaining their admission and integration.

Introduction

Every two seconds, one person is forced to flee as a result of conflict or persecution nowadays. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are 89 million forcibly displaced people worldwide. More than 27 million of them are refugees, mostly hosted in developing countries. As the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine demonstrated, the so-called 2015 refugee crisis might have been just the tip of the iceberg. Indeed, world leaders, policymakers, and international organisations forecast population movements to boom in the following decades.Footnote1

Beyond the short-term socioeconomic hardships that such developments may bring to both refugee and native populations, the political ramifications are likely to be profound and long-lasting. By now, it is clear that exposure to the refugee crisis made natives in some European countries hostile toward minority groups (Hangartner et al., Citation2019) and more likely to vote for anti-immigrant parties (e.g., Dinas et al., Citation2019; Dustmann et al., Citation2019; Tomberg et al., Citation2021).Footnote2 The upsurge of far-right populism, fuelled in part by the public backlash against immigration, has shaped some of the most significant political developments in recent years, including economic protectionism, Euroscepticism, and political polarisation. Liberal democracies seem to be in a condition of crisis, backsliding, and continuously challenged by opposing political forces from within. If future economic and political developments will indeed intensify forced migration to the west, how can liberal democracies cope with the expected public backlash?

One fact makes the political repercussions of the 2015 refugee crisis particularly puzzling: in per-capita terms, the share of asylum seekers and refugees in the European Union population was moderate. In the peak of the crisis in 2015, there were 2.6 asylum applications per one thousand residents (Eurostat, Citation2019). Without underestimating the great challenge these numbers pose – especially when forcibly displaced people and natives differ in terms of their ethnic, cultural, and religious characteristics – they seem manageable, rather than being generators of crisis. Many critics used this fact to support their claim that the refugee crisis was not a real crisis by any objective terms, but rather an imagined emergency, constructed by nativists who wished to keep foreigners out of Europe.

However, the flow and spatial distribution of asylum seekers were highly concentrated, putting much more weight on certain regions while leaving others unexposed, both within and across EU countries. Such a disproportionate burden might make many of those who bear it alienated and resentful, and those who expect to face this challenge in the future, anxious and fearful. Consequently, not-in-my-back-yard (NIMBY) opposition to refugees is likely to rise in both cases, making it harder for political leadership and policymakers to admit refugees and allocate them to local communities across the country.

What explains NIMBYism and could it be countered? Answering this question can help host-countries in dealing with the admission of refugees while maintaining social solidarity and political stability. NIMBYism represents the decreasing level of support for immigration as a function of immigrant physical proximity. The closer immigrants or refugees are (or about to be) to natives’ local communities, the stronger native opposition is. While many citizens believe that their country should help refugees, fewer are also willing to share the responsibility of refugee accommodation in their local community (Ferwerda et al., Citation2017). As such, NIMBYism appears to stem from egocentric considerations and free-riding on the contributions of fellow citizens.

However, previous work demonstrated that public attitudes toward immigration and asylum seekers are not significantly driven by natives’ individual circumstances and self-interests, but rather by sociotropic considerations on the nation as a whole (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Citation2014). Consistent with this account, a considerable body of evidence shows that most people behave like moral and emotional reciprocators with respect to civic obligations: they condition their contributions to collective goods on the contributions of others (Kahan, Citation2003).

What determines which of these countervailing forces overcomes the other? I contend that many citizens are conflicted about hosting refugees in their local communities. On the one hand, they are willing to help their fellow citizens in sharing the national burden of refugee integration. Yet they also fear that the socioeconomic burden will be too heavy and unequally shared. Anxiety about the unknown ramifications of hosting refugees underlies some of the NIMBY syndrome. Therefore, I argue, government policy can counter NIMBYism by setting clear and fair burden-sharing mechanisms, and making citizens believe that the burden of integrating refugees is being fairly reciprocated (Kahan, Citation2003).

To test this argument, I use four survey experiments conducted in Norway and Israel. The experiments reveal that citizens are more apprehensive about immigration to their local community than to their country, and that opposition to refugee incorporation rises when natives’ understand that refugees will be accommodated in their local community. This set of findings shows that NIMBYism indeed shapes public opposition to immigration and to the integration of forcibly displaced people. However, the results also demonstrate that citizens are more willing to take in refugees when doing so will help their fellow citizens. Moreover, citizens’ preferences regarding refugee incorporation are strongly affected by the policies that guide the spatial distribution of refugees. Specifically, refugee dispersal policies counter NIMBYism when they set clear allocation rules that promote reciprocity dynamics and civic cooperation.

The effects of dispersal policies are substantial and politically meaningful. Beyond the attitudinal effect, they also shape citizens’ willingness to engage and lobby their elected officials to express this position. The analysis also reveals that the impact of dispersal policies remains significant on a subset of respondents for whom moving to proportional or upper limit allocation would increase the number of refugees allocated to their own localities. This suggests that the increase in inclusionary attitudes following refugee dispersal is not driven by material self-interest, but rather stems from civic-minded, sociotropic considerations.

The paper contributes to the growing literature on interventions that can promote inclusionary attitudes toward immigrants and refugees (Adida et al., Citation2018; Kalla & Broockman, Citation2020). To date, much of this literature has focused on prejudice reduction through intergroup contact or perspective taking. The findings presented here indicate that, beyond prejudice reduction, government policies can also mitigate exclusionary attitudes toward immigrants by fixing collective action problems that relate to immigrant admission and integration. In times of rising anti-immigrant backlash, the accumulation of evidence on different strategies that can effectively reduce exclusionary attitudes toward forced migrants is valuable for the design of policy responses to immigration and global refugee crises.

Theoretical background

Immigrants tend to concentrate geographically in ethnic enclaves established by previous immigrants. Potential reasons for this spatial self-selection include the concentration of affordable housing supply, available jobs that match migrants’ skills, and an immigrant community that shares language, culture, and valuable information on how to adjust to the new living conditions in a foreign country. In line with these advantages, recent work showed that ethnic enclaves have positive effects on the economic standing of refugees (Martén et al., Citation2019). Conversely, when the ethnic enclave reduces exposure to the national culture and language, it can also hinder economic integration (Borjas, Citation2000). Even so, enclaves grant refugees higher cultural amenities. Refugees can more easily associate with persons who share a common language and culture. Therefore, even if refugees fear potential economic disadvantages ensued by living in ethnic enclaves, they are often willing to pay the price.

However, immigrant residential concentration is a major source of discontent for natives. When asked whether ethnic residential segregation is a social problem, only 3–4 per cent of native residents in Helsinki, Oslo, and Stockholm responded a definitive `no’ (Andersson et al., Citation2017).Footnote3 Those who live in refugee-receiving communities bear disproportional burdens and experience a local ethnocultural change that can be perceived as highly threatening. As the numbers of refugees increase over time, local opposition often rises, expressing discontentment from being forced to bear the socioeconomic burdens on their own. In Israel, for example, the native residents of southern Tel Aviv protested about the deterioration they experienced in terms of crime and security since the arrival of thousands of African asylum seekers to their neighbourhoods (Shechory-Bitton & Soen, Citation2016). They claimed that their fellow citizens free-ride at the expense of receiving communities. By this view, free riding allows those who live in more economically advantaged communities to enjoy the privilege of being portrayed as more tolerant and righteous when there are no real costs for holding such views. But living in proximity to immigrant or refugee enclaves is not a prerequisite for a native backlash. Natives who do not host migrants often complain about immigrant self-segregation and the creation of ‘parallel lives’ or ‘no-go zones’, which they view as harming the socioeconomic integration of voluntary and forced migrants, and posing difficulties for the police to fulfil their law enforcement missions.

Facing the local backlash (sometimes amid growing numbers of forcibly displaced people), politicians and policymakers are in a dilemma over how to address the situation. On the one hand, enacting dispersal policies in which refugees are more evenly distributed across the country can reduce the local backlash and address public dissatisfaction about residential segregation. On the other hand, once refugee dispersal is announced or enacted, NIMBY opposition is more likely to emerge and grow in multiple locations across the country, transforming the local backlash into a national one. Ex-ante, both scenarios are reasonable and rest upon well-established behavioural tendencies that are prevalent across high-income democracies.Footnote4

The first behavioural motivation is the egocentric NIMBYism. Some observers have portrayed NIMBYism as a moral struggle between civic-minded planners and self-interested local opponents (Gibson, Citation2005). Most generally, regardless of its application,Footnote5 NIMBYism describes ‘macroscale support that does not carry over to the microscale, meaning the preferences are scale-dependent’ (Hankinson, Citation2018, p. 474). Thus, NIMBYism can describe scale-dependent preferences in various geographic units of analysis. For example, Europeans’ higher level of support for the admission of refugees into Europe compared to their level of support for the admission of refugees by their own country reflects NIMBYism at the international-to-national level (Bansak et al., Citation2017). Here, I focus instead on NIMBYism at the national-to-local community level. Namely, the rise in public opposition when the incorporation of asylum seekers and refugees takes place in citizens’ local communities compared to their opposition to refugee inclusion at the national level and in others’ local communities.

In the context of refugee arrivals, NIMBYism is often interpreted as an expression of individuals’ egocentric propensity to avoid the heavy burdens that are imposed on the collective. Avoiding these burdens means that individuals are free riding on the contributions of others – those who do help filling the legal duties and moral obligations of the nation. Although many individuals feel that helping refugees is the right thing to do, they might be concerned that fellow citizens are free riding, or even prefer to let others bear the socioeconomic burdens of refugee accommodation and integration. Alternatively, rather than fear of socioeconomic burdens, the geographical proximity of refugees might trigger latent intolerance toward foreigners. Yet regardless of the reasoning, NIMBYism was found as an important source of influence: natives’ support for the admission of refugees outside of their local community is significantly higher than their support for hosting refugees in their local community (Ferwerda et al., Citation2017). Based on this theoretical account, refugee dispersal should increase public opposition to refugees at the national level – at least in the short term, before intergroup interactions intervene.

The second behavioural motivation is sociotropic and civic-minded.Footnote6 Sociotropic considerations are considerations that take into account the collective interest (Meehl, Citation1977). In the literature on immigration attitudes, they are defined as broad civic considerations not related to personal circumstances but rather to people's evaluation of the potential economic and cultural impacts of immigration on the nation as a whole (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Citation2014; Solodoch, Citation2021a; Valentino et al., Citation2017). If citizens are driven by civic motivations, refugee dispersion over the country should restrain anti-immigrant backlash for two key reasons. First, because it is broadly perceived as enhancing the socioeconomic and cultural integration of refugees, which is beneficial for the nation. And second, since shouldering the burden carried by fellow citizens' communities is perceived by many as a civic virtue (Kahan, Citation2003).

I contend that both behavioural motivations operate simultaneously. The institutional setting determines which force prevails. When the dispersion of forcibly displaced people over the country occurs spontaneously by their own choices, it is coupled with high levels of uncertainty. The potential socioeconomic burden from accommodating increasing numbers of refugees and the cultural transformations of neighbourhoods constitute significant uncertainties that threaten native citizens (Kaufmann, Citation2018). The geographic dispersion of forcibly displaced people is therefore fertile ground for NIMBYism and anti-immigrant backlash. Although self-interest is perhaps not the default, it is activated when there is no guarantee that the expected burden will be moderate and widely shared. Furthermore, such uncontrolled and non-coordinated environment might activate a race to the bottom, in which local communities across the country express stronger and stronger anti-immigrant sentiments to scare off potential immigrant residents.

Yet uncertainty can be reduced. As a coercive third party to civic cooperation, the state can monitor refugee dispersion and enforce burden-sharing mechanisms. Tighter regulation can signal to the public that the government is competent and has immigration under control (Briggs & Solodoch, Citation2021; Solodoch, Citation2021b). Furthermore, if citizens get assurance from the government that the size of the newly arrived group of refugees would be limited (and thus also limited would be the demographic change in local communities), they would feel less threatened by refugees. Consequently, I argue, not only that public opposition to refugees would be mitigated, residents of non-receiving communities should turn more willing to bear heavier burdens than before to promote refugee integration.

Note that this tells us something different about NIMBYism and the self-interest of local communities. Rather than being the default propensity, activated whenever heavier burdens are at stake, the logic of sociotropic considerations suggests that people tend to be civic minded and reciprocate even when they pay a price. Once uncertainty is high, the upper bound of this price turns too costly, however, which evokes NIMBYism.

A normative appeal to fairness might also restrain NIMBYism. By this perspective, the strong normative appeal people have to fairness, justice, equality and reciprocity shapes their policy preferences and political behaviour (Day et al., Citation2014). More relatedly to the political impact of asylum policy, dispersal policies aim to enhance equality in burden-sharing and are often based on the principle of proportional equality, where refugees are assigned across the country based on demographics and socioeconomic capacity of different municipalities. If proportional equality makes dispersal policies a countering force to anti-immigrant backlash, this counter effect should be stronger when the burden-sharing mechanism uses proportional refugee allocation. Alternatively, if citizens are motivated by the logic of reciprocity more generally (Kahan, Citation2003), then the counter-NIMBY effect of dispersal policies should be observable and similar across different burden-sharing schemes.

Research design: multi-context experiments

I test my theoretical expectations and the extent to which they are context-dependent using four survey experiments from two different cases. Norway, in which dispersal policies are in place since 1994 (Fasani et al., Citation2022), and Israel, in which dispersal has been proposed but never implemented. Thus, while both cases are high-income democracies with a roughly similar population size, they vary in many important factors: the policy used to determine refugee settlement across the country (or the lack thereof), the extent to which forced migrants are geographically scattered in practice, the ethnic and cultural characteristics of the native population, and both the source countries and official status of the forced migrant population under examination. The two cases therefore provide an opportunity to assess whether the theory of dual behavioural motivations I laid out above travels across different political and cultural environments.Footnote7.

Both in Norway and Israel, the unit of analysis is an individual citizen, not the country itself, and I use large-N cross-unit comparisons to study each case. The main aim is not to draw macro-level, cross-national inferences. Rather, each case stands on its own and the internal validity of its findings can be assessed separately, but the combination of both cases helps identifying the study's scope and of the applicability of my argument across different contexts. This cross-context experimental design that includes experiments around the same research questions in multiple country and subnational cases is increasingly used by researchers in recent years to assess the generalisability of treatment effects across contexts (Blair & McClendon, Citation2021).

Norway

Forcibly Displaced Populations. Over the years, Norway has accepted and integrated various groups of refugees, with three large waves of refugee arrivals in recent decades: The first wave followed the Balkan wars; the second was caused by the war in Iraq; and the third wave followed the Syrian civil war (Finseraas & Strøm, Citation2022). In analysing the Norwegian case, I focus on public support for refugees in the context of the Syrian refugee crisis. Out of 31,150 asylum applications lodged in Norway in 2015, 33 per cent were lodged by Syrian asylum seekers.Footnote8

Dispersal Policy. In Norway, local government autonomy is the leading principle governing refugee settlement (Hernes, Citation2017). Asylum applications are handled by the Directorate of Immigration, a national executive agency under the Ministry of Justice and Public Security. While applications are processed, asylum seekers live in reception centres. The Directorate of Integration and Diversity (IMDi) is then responsible for settling those applicants who are recognised as refugees in coordination with the local governments at the county and municipality-level. Local governments receive petitions from the IMDi asking them to settle a certain number of refugees in the following year. Each local government can decide, usually by vote in the elected council, whether to respond, accept, reduce, or reject the petition. If they choose to accept the petition, local governments receive subsidies calculated on the basis of the number of refugees they settle (Askim & Steen, Citation2020).

Capturing NIMBY opposition to refugees in Norway is challenging, since the decision to settle refugees is voluntary for Norwegian municipalities. However, in response to the sharp increase in the number of asylum seeker arrivals in 2015, there was an urgent need to provide shelter for the newcomers. To address this need, between April 2015 and March 2016 the Directorate of Immigration (UDI) commissioned 259 temporary shelters or ‘emergency facilities’ for asylum seekers and allocated them across the country. Unlike the situation with the dispersal of recognised refugees, where local governments have the autonomy to decide whether to host refugees, the establishment of asylum centres was directed by the central government. As a result, some local communities were required to host asylum seekers for the first time. Public ‘information meetings’ were hosted by the UDI to inform the residents of local communities about the forthcoming establishment of asylum centres (Bygnes, Citation2020).

Israel

Forcibly Displaced Populations. Eritrean and Sudanese nationals represent the largest groups of forced migrants in Israel. Most of them arrived in Israel between 2006 and 2013 through the border with Egypt. Eritreans and Sudanese asylum seekers received temporary group protection because of civil rights abuse in both countries. However, instead of refugee status, they received a ‘conditional release visa’ (known as the 2(a)5 visa), which they were required to renew every two or three months. They also received informal access to the labour market, meaning that the government did not grant them formal work permits, but in practice they were allowed to work.

While the Israeli government granted Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers temporal collective protection from deportation, the authorities still define them as ‘unauthorized immigrants’ or even ‘infiltrators’. Instead, I follow the terminology used by the UNHCR to describe forcibly displaced people in Israel. Specifically, I use the terms ‘refugees’ and ‘asylum seekers’ not in their official definitions under international law (most of the Eritrean and Sudanese immigrants did not apply for asylum and almost none of them received a formal refugee status) but rather interchangeably to describe forcibly displaced people who came mainly from Eritrea and Sudan.Footnote9.

Dispersal Policy. Unlike Norway, Israel has no refugee dispersal policy, although such a policy has been discussed in 2018. As a result, the vast majority of Israeli communities do not host asylum seekers. Concentrations of asylum seekers were relatively small and created only in several cities. In stark contrast, the largest group by far was clustered in the lower-income neighbourhoods of southern Tel-Aviv, reaching in its height to 25,000 asylum seekers – approximately 6.2 per cent of the population of Tel Aviv, but 38 per cent of southern Tel Aviv.

Spatial dispersion in Norway and Israel

To examine the extent to which refugees are dispersed over both countries, I use municipality-level data on the share of residents from the main source countries of refugees. For Norway, I focus on the share of Syrians in the population of each municipality, based on Statistics Norway.Footnote10 For Israel, I use the share of all asylum seekers – or, as the Population and Immigration Authority (PIA) defines them, ‘infiltrators’ – in each municipality with more than 1000 residents, based on data from the PIA and the Central Bureau of Statistics ().

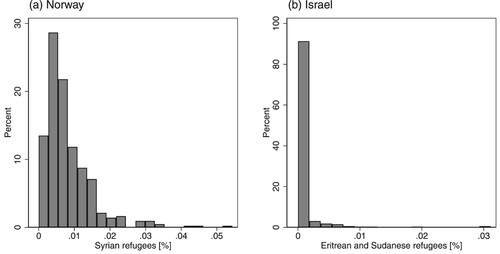

Figure 1. The distribution of forced migrants across municipalities.

Note: For Norway, the figure shows the distribution of residents from Syria in the population of each municipality, based on Statistics Norway (available at: https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank/table/09817/). For Israel, the figure presents the distribution of all refugees (91 per cent of them are from Eritrea and Sudan) in each municipality with more than 1000 residents, based on data from the PIA and the Central Bureau of Statistics.

The data show that the Norwegian dispersal policy successfully distributes Syrian refugees over the country. Only 6 per cent or 26 out of 422 municipalities do not host Syrian residents. In Israel, on the other hand, 86 per cent or 424 out of 489 municipalities had no asylum-seekers residing in them. Notably, focusing on these selected groups of forced migrants, both the average share of all forced migrants (4.1 vs. 0.07 per cent in 2017) and their total number (217,241 vs. 37,000) are considerably higher in Norway.Footnote11

Yet while public backlash in Israel against African asylum seekers residing mainly in southern Tel Aviv was intense, such opposition to forced migrants during the 2015 crisis was limited in Norway. In fact, Norwegian municipalities exhibited a sudden willingness to settle refugees (Søholt & Aasland, Citation2021).Footnote12 More generally, despite demographic changes and the increase in immigration rates, public opposition to immigration in Norway has decreased in recent decades (Hellevik & Hellevik, Citation2017). A similar pattern exists in a broader set of cases: In Figure A-5, I show that across 19 countries in the European Social Survey, including Norway and Israel, public opposition to refugees is 4 percentage-points lower in countries that use dispersal policies, controlling for various individual-level characteristics and contextual factors.

To be sure, many other national-level factors could account for these broad differences in public reactions to refugee inflows. What is clear, however, is that the burden of refugee accommodation is considerably more equally shared by municipalities in Norway, and that Israeli citizens have become aware of the unequal burden, socioeconomic distress and neglect in southern Tel Aviv and its residents’ feelings of injustice (Shechory-Bitton & Soen, Citation2016).

The NIMBY experiments in Norway

To explore the dual behavioural forces that shape public opposition to hosting forcibly displaced people, I first utilise two experiments that were designed and conducted by the Norwegian Citizen Panel (NCP). The NCP is a probability sample of the general Norwegian population above the age of 18, administered by the Digital Social Science Core Facility (DIGSSCORE) at the University of Bergen. Each round of survey constitutes a representative cross-section of the Norwegian population.Footnote13

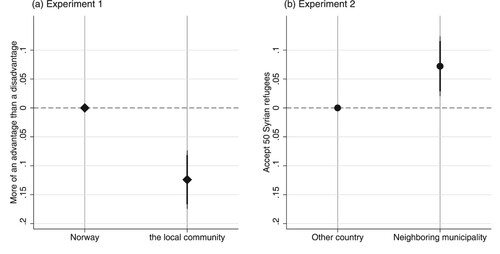

The first experiment was embedded in wave 12, which was fielded in June 2018. Respondents were asked: ‘In your opinion how great an advantage or disadvantage is it for [Norway/the local community] that immigrants come to live here?’ Half of the sample was randomly assigned to the national treatment, and the other half to the local community treatment. By randomly manipulating the geographical proximity of the place immigrants arrive in, this experiment is able to test whether proximity triggers negative sentiments toward immigration. Responses were located on a seven-point scale, from (1) ‘Very great advantage’ to (7) ‘Very great disadvantage.’ I recode the dependent variable into a dummy variable for seeing immigration as an advantage (1–3 in the original, ordinal scale).

Panel (a) in presents the results. While 43.5 per cent of Norwegians see an advantage in immigrants coming to live in their local communities, 55.9 per cent think so when asked about immigrants coming to live in Norway. Backyard proximity decreases positive sentiments toward immigration by 12 percentage points or 22 per cent. The results are in line with the NIMBY syndrome – the perceived proximity of immigrants to people's backyard triggers public discontentment.

Figure 2. The NIMBY experiments, Norway.

Note: Both panels present point estimates and confidence intervals from separate linear probability models for each experiment. Thick and thin lines denote 90 and 95 per cent confidence intervals, respectively. The outcome variables are binary indicators that equal 1 if the subject thought that admitting immigrants creates more advantages than disadvantages (Experiment 1, N = 1486), or if the subject was willing to accept 50 more Syrian refugees into her municipality (Experiment 2, N = 1247).

If citizens are primarily driven by self-interest, helping their fellow citizens should not be a significant consideration. Whether compatriots will be better- or worse-off, individuals would seek to minimise their own burdens. Alternatively, if sociotropic considerations play a meaningful role in shaping public responses to refugee arrivals, then helping their fellow citizens and sharing a national burden would make citizens more willing to host refugees.

The second experiment I present was conducted by the NCP in October and November 2015. Respondents were asked to read the following preamble: ‘Consider a proposal to accept an additional 50 Syrian refugees into your municipality and provide basic integration services, such as medical care and shelter.’ In June 2015, Norway decided to accept 8000 Syrian refugees for resettlement during 2015-2017. The experiment explicitly made clear that the 50 refugees are not included in this quota, which was completed in 2017, and randomly assigned the sample into two groups (alternative wording in brackets): ‘These refugees are not included in the 8,000 quota and would otherwise not be allowed to enter the country [be assigned to a neighboring municipality].’

Namely, in either case, respondents are asked to host 50 refugees – an identical additional burden. Yet in the neighbouring-municipality treatment, accepting the refugees would also reduce the burden from other compatriots. Finally, respondents were asked: ‘Imagine that you are personally voting in a public referendum on this proposal. Would you like to directly vote for or against this proposal?’Footnote14 Possible responses for this question were either ‘for’ (1) or ‘against’ (0).

As presented in panel (b) of , the results demonstrate the civic-minded propensity of citizens to help their compatriots. While 71.5 per cent supported the proposal in the neighbouring-municipality treatment group, 64.3 per cent were willing to accept 50 more refugees in the out-of-country treatment – a significant 7 percentage points (or 11 per cent above the baseline) treatment effect. People are more willing to bear larger burdens when they do so for their fellow citizens.

Next, I utilise data on respondents’ proximity to asylum centres in their local areas. In wave 7 (November 2016), respondents were asked whether there is an asylum seekers’ centre in their local area, and when it was established. Out of the 1247 respondents who participated in the second experiment, 896 were also interviewed in wave 7 and provided information on local proximity to asylum centres. I code two binary variables that equal 1 for respondents who reported that an asylum centre was established in their local area: (1) at any time in the past; and (2) in 2015 – when the Directorate of Immigration commissioned hundreds of temporary shelters for asylum seekers and allocated them across the country due to the sharp increase in the number of asylum seekers (Bygnes, Citation2020).Footnote15

As shows, the effect of the neighbouring municipality treatment remains large and statistically significant for the subset of respondents on which data on proximity to asylum centres are available. Furthermore, columns 3 and 4 show that respondents living in proximity to a new asylum centre are more opposed to the admission of Syrian refugees in their local community, and this association remains marginally significant when respondents’ gender, level of education, and county of residence are controlled for. As in Experiment 1, these results are also consistent with the NIMBY syndrome, showing that real proximity of new asylum centres to people's local communities might activate public opposition to refugees. Yet as column 5 shows, the effect of the neighbouring municipality treatment similarly increases support for the admission of more Syrian refugees, regardless of living in proximity to the newly established asylum centres. This suggests that even citizens whose local communities already shoulder the burden of hosting forced migrants are more willing to accept more refugees when this also helps their fellow citizens.

Table 1. Effect of the neighbouring municipality treatment and proximity to asylum centres.

Importantly, the treatment increases willingness to accept more refugees even though no other local community shares this extra burden. This suggests that the treatment effect is driven by the clear upper limit of the extra burden, regulated by the government policy, rather than a normative appeal to fair and proportional allocation. Nonetheless, the experiments were not designed to test for these different underlying mechanisms. In addition, it is possible that the validity of these results is limited to countries in which refugees are widely dispersed across the country and most citizens share some of the national burden in the first place. The following results shed light on these remaining questions.

The dispersal policy experiment in Israel

To collect data on public attitudes toward refugees in Israel, I conduct a national online survey, fielded by iPanel, the largest opt-in online panel company in Israel. I used quota sampling to match the sample to the population on several parameters: gender, age, education, religiosity and immigration from the Former Soviet Union (FSU). Summary statistics of the sample compared to the population are reported in Table A-2.

The dispersal policy experiment was embedded in the first wave of the survey. I designed it to test the impact of a newly proposed dispersal policy on inclusionary attitudes toward asylum seekers. The policy aimed to do justice – by economic compensation and geographic dispersal – with the residents of the refugee-receiving communities in southern Tel Aviv who bear heavier burdens than their counterparts. Yet the policy change presented in the experiment would directly benefit only the residents of southern Tel-Aviv, at the expense of the vast majority of citizens who have little to no contact with asylum seekers in their hometowns.

For this purpose, each respondent was first required to read a short explanation about a lawful residency status: ‘The state of Israel can grant a lawful residency status to asylum seekers residing in its territory. This status allows asylum seekers to work legally in Israel.’Footnote16 To assess the impact of dispersal and investment policies on public opposition to asylum seekers, respondents were then randomly assigned into four treatment conditions. Each treatment included information about a policy proposal comprised of three components: (1) geographic dispersal, which aims to lower the number of asylum seekers residing in the neighbourhoods of southern Tel-Aviv; (2) financial investment in the rehabilitation of southern Tel-Aviv neighbourhoods; and (3) granting lawful residency status to asylum seekers. Yet while the third component remained constant across all treatment conditions, the first two components were randomly either included in or excluded (presented in negation) from the policy proposal, as presented in .Footnote17

Table 2. The dispersal experiment, policy treatments.

To overcome social desirability biases, I use an implicit measure for attitudes toward asylum seekers.Footnote18 Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they will support or oppose the programme on a seven-point scale, ranging from ‘definitely oppose’ to ‘definitely support’. Because granting a lawful residency status to asylum seekers is the only constant policy component, differences in respondents’ support for the policy represent treatment effects on public opposition to the integration of asylum seekers as lawful residents in Israel.

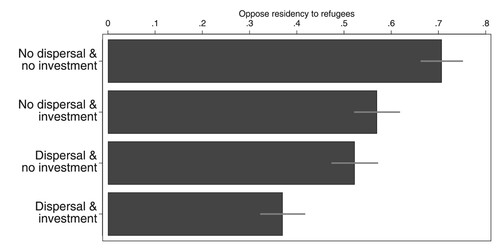

The experimental results are presented in . The first policy preserves the status quo condition – no dispersal and no investment in host-neighbourhoods. As such, it should reflect public attitudes toward refugees in Israel in the general public under no policy treatment. Indeed, the proportion of respondents opposing to the incorporation of asylum seekers (70 per cent) is close to the proportion of citizens supporting their deportation out of Israel (65 per cent) in previous opinion polls (Yaar & Hermann, Citation2018).

Figure 3. The dispersal experiment, Israel.

Note: N = 1587. Bars represent the proportion of respondents locating themselves under the mid-point on the 1 (‘definitely oppose’) to 7 (‘definitely support’) scale (with 95 per cent confidence intervals).

Consistent with the sociotropic and fairness accounts, each policy treatment reduces the baseline opposition considerably. Given a policy of investment with no dispersal, opposition to asylum seekers drops 13 percentage points, or 19 per cent under the baseline. Given a policy of dispersal with no financial investment, a decrease of 18 percentage points (or 26 per cent) in public opposition is detected. Each policy treatment independently affects the public, since both policy components reduce public opposition by 33 percentage points, or by 47 per cent. These effects are substantial and politically meaningful. They indicate that dispersal and investment policies can shape anti-immigrant backlash dramatically. Here, policy effects turned a situation of a large majority resisting the incorporation of asylum seekers into a majority in favour of it.

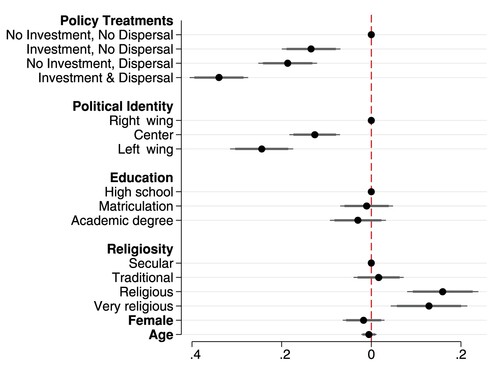

To contextualise this effect, presents the results from a linear probability model, controlling for respondents’ political identity, level of education, religiosity, age and gender. Policy effects remain highly significant (p < 0.001) and substantively large. The impact of each policy component generates a shift in preferences that is similar to the differences between right-wing and centre voters. A policy of both investment and dispersal reduces opposition to refugees in a magnitude that is even larger than the preference gap between right-wing and left-wing voters.

Figure 4. Dispersal and investment policy effects on opposition to asylum seekers, Israel.

Notes: N = 1587. Point estimates and 90 and 95 per cent confidence intervals are drawn from a linear probability model and denoted by dots and horizontal lines. The outcome is a binary variable that indicates opposition to granting lawful residency to asylum seekers (response categories located under the mid-point on the 1 (‘definitely oppose’) to 7 (‘definitely support’) scale).

Respondents’ gender or age are not significantly associated with inclusionary attitudes toward asylum seekers. Conversely, individuals with higher levels of religiosity tend to be less tolerant toward asylum seekers. Compared to secular individuals, religious and ultra-Orthodox respondents are 12–15 percentage points likelier to oppose the incorporation of asylum seekers as lawful residents. The effect of the dispersal policy treatment is 5 (3) percentage points larger than the difference between secular and religious (very religious) respondents. Notably, these results are at odds with the self-interest mechanism and the NIMBY syndrome. Citizens are more supportive of refugee integration following a policy that relocates asylum seekers across the country and, consequently, in their own local communities.

Yet this finding may be a result of either respondents’ unawareness of how dispersal will affect them or a visceral response to the normative appeal of distributive justice. It may not hold once citizens grasp the ‘backyard implications’ of geographic dispersal, or when behavioural outcomes are examined. Another concern pertains to the extent to which the dispersal experiment captures real changes in anti-immigrant sentiments, rather than compromises between policy alternatives that citizens make while still preferring to deport asylum seekers if they could. The NIMBY experiment in the following section addresses these concerns.

The NIMBY experiment in Israel

The NIMBY experiment was embedded in the second wave of the survey. Respondents were asked to carefully read two paragraphs. The first paragraph described the situation of asylum seekers and native residents of southern Tel Aviv. The second presented a potential policy to deal with the situation. In contrast to the dispersal experiment, all previous policy components – the dispersal of asylum seekers over the country, financial investment in rehabilitation of southern neighbourhoods in Tel Aviv, and status regularisation for unauthorised asylum seekers, which will make them lawful residents in Israel – were held constant.Footnote19

As presented in , the experiment then randomly assigns respondents into six treatment conditions over two dimensions – ’backyard’ and ‘allocation rule’. On the backyard dimension, half of the sample was informed that, as part of the dispersal policy, some asylum seekers would be relocated to the localities of its respondents. The other half did not receive such information. On the second dimension, the sample was divided into three groups. One group did not receive any information about the dispersal technique. A second group was told that dispersal will be implemented under an upper limit principle (not more than 0.5 per cent or 500 asylum seekers would reside within a certain municipality). The third group received information about a different technique, wherein dispersal will be implemented under a proportional allocation principle (the larger the population and the stronger the economic standing of a certain municipality, the more asylum seekers would reside in it). Notably, the proportional allocation technique is based on the principle of proportional equality but has no clear cap, while the upper limit policy creates significant disparities in burden-sharing but has a clear cap. Respondents were then asked to locate their opposition or support for this policy. Answers on a seven-point scale ranged from ‘Definitely oppose’ to ‘Definitely support.’

Table 3. Experimental design.

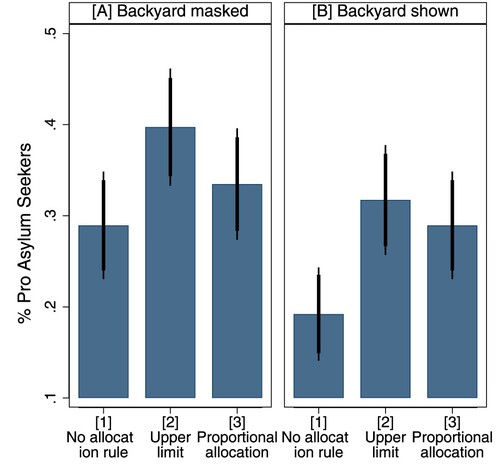

displays the treatment effects of the NIMBY experiment. Each treatment group is indexed over the two experimental manipulations: A or B for masking or explicitly telling respondents that the new policy means their local community will host refugees, and 1, 2, or 3, for the allocation rules as described beneath each bar.

Figure 5. The NIMBY experiment, Israel.

Note: N = 1360. Vertical lines represent 90 and 95 per cent confidence intervals. Bars represent the proportion of respondents supporting the refugee integration programme (i.e., located above the midpoint on a seven-point scale ranged from ‘Definitely oppose’ to ‘Definitely support’).

Firstly, as demonstrated by a comparison of groups A1 and B1, NIMBYism does shape public opposition to refugees. When no specific dispersal technique is introduced, respondents who were informed that their locality would admit asylum seekers as part of the dispersal policy were significantly more opposed to the programme that grants asylum seekers legal residency in Israel. Support for the programme drops 9 percentage points (or 33 per cent) when backyard implications are acknowledged — undoubtedly a sizable NIMBY effect.

Do the allocation rules matter? Presenting the three treatment conditions that were not reminded about backyard implications, Panel A demonstrates that proportional equality and upper limit are indeed influential. Informing respondents about allocation mechanisms decreases opposition to the programme that would allow asylum seekers to gain lawful resident status. Upper limit and proportional allocation policies increase support for the programme by 10 and 5 percentage points, respectively.

It is important to recall that the powerful treatments from the first-wave experiment are held constant in the NIMBY experiment. This means that the baseline support for refugee incorporation (the ‘no allocation rule & backyard masked’ treatment) is already heightened by the dispersal and investment policy components, and the allocation principles increase it even more. But do these positive effects overcome the conflicting NIMBY effects?

An examination of Panel B suggests they do. The panel displays the extent to which allocation procedures and tighter regulation reduce NIMBY opposition to refugee incorporation. All three treatment conditions in panel B include information on backyard implications. Yet while in treatment B1 no dispersal technique is introduced, B2 and B3 provide information about upper limit and proportional allocation procedures, respectively. The impact of each allocation technique is statistically significant and substantively large. The upper limit policy increases support for refugee incorporation by 12 percentage points (or 61 per cent). A positive impact of 9 percentage points (or 49 per cent) on support for the programme is ensued by a proportional allocation policy. Strikingly, each allocation rule eliminates the entire NIMBY effect that is derived from explicitly mentioning the backyard implications of dispersal policies.

A real attitudinal change?

One important concern about these findings is the extent to which they represent a real attitudinal change. After all, one may prefer a fair dispersal policy over no dispersal given that asylum-seekers stay in the country, but still favour their deportation over all other options. In this case, the policy effects I have presented are only a matter of compromise between two unfavourable solutions to the issue of asylum seekers.

To test this, a follow-up question was embedded in the survey. Respondents were asked: ‘and if you were able to choose each of the following possibilities, what would you choose?’ The possibilities were, in randomised order, (1) keeping the status quo; (2) Investment, no dispersal, and lawful residency to asylum-seekers; (3) Investment, dispersal, and lawful residency to asylum-seekers; and (4) Deporting asylum seekers back to their countries of origin. This allows me to examine whether people prefer granting lawful residency to asylum-seekers over deportation as a result of the policy treatments. The outcome variable for this test is binary, where ‘1’ indicates not only support for lawful residency, but also preferring the regularisation of status over deportation.

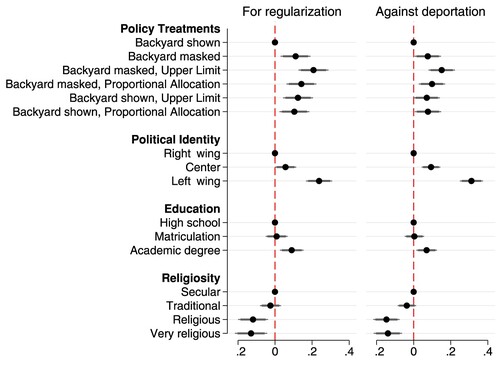

Overall, as shows, despite a slight weakening in magnitude and statistical precision, policy effects remain statistically significant and substantively large. Their magnitude resembles the attitudinal differences between right-wing and centre voters. Both upper limit and proportional allocation increase inclusionary attitudes by 7 percentage points, even when citizens can choose deportation and are aware of the fact that, if not deported, asylum seekers will be accommodated in their local communities. In addition, as I show in Appendix Table A-3, upper limit and proportional allocation policies make respondents 6 percentage points more likely to sign a petition that would include their personal information to their public representatives, in support for the incorporation of asylum seekers as lawful residents.

Figure 6. Prioritising regularisation of status for asylum seekers over deportation.

Note: N = 1360. Dots and lines represent point estimates and 90–95 per cent confidence intervals drawn from two linear probability models. The first model uses the outcome variable that simply indicates support for the regularisation of status of asylum seekers (1 if supportive, 0 otherwise). The second model uses the outcome that equals 1 only if the respondent is both supportive of regularisation of status and does not switch to supporting deportation in the follow-up question. Both models also control for respondents’ age and gender.

Mechanisms

What mechanisms might drive these counter-NIMBY effects? If it was primarily a normative appeal to fairness that generated the policy effects, then the proportional allocation policy should have exhibited a significantly stronger effect than the upper limit policy. Given dispersal, the upper limit policy clearly deepens inequality – a large city, such as Jerusalem with its 870,000 residents, will take 0.6 asylum seekers per 1000 residents, while small towns with up to 10,000 residents, will take 5 asylum seekers per 1000 residents (the maximum number for the former and maximum share for the latter). Nevertheless, the upper limit policy manages to allay NIMBYism. Also, countering NIMBYism does not depend on assuring a minor number of asylum-seekers are relocated in people's backyard. The 500/0.5 per cent cap in the upper limit policy is far from insignificant for local communities, and the proportional allocation rule has no upper bound at all.

Instead, what seems to effectively reduce NIMBY opposition to asylum-seekers is the creation of a clear allocation rule that will guide the dispersion of forced migrants over the country and ensure a certain degree of reciprocity. Having dispersal monitored and under government control makes citizens less opposed to refugee incorporation and more willing to share the burden with their fellow citizens. This underscores the capacity of governmental intervention to fix collective action problems. Even if a citizen prefers a proportional distribution of asylum seekers across the country and wants to shoulder the burden, the possibility that many citizens will manage to avoid accommodating asylum seekers would discourage her to take part in this joint action. Assuming that fellow citizens would be required to cooperate by their government, however, would encourage her to take part in this joint action and support the accommodation of asylum seekers in her local community. Once either upper limit or proportional allocation techniques were proposed, respondents were less intimidated by the backyard implications of the dispersal policy.

An open question remains, however, does the impact of dispersal policies stem from sociotropic or egocentric considerations? In Table A-4, I show that there is no interaction between policy treatments and the propensity to carry heavier burdens following refugee dispersal. Compared to the general population, policy effects are not weaker for citizens who will bear heavier burdens following the dispersal of asylum seekers.

Taken together, these results suggest that the egocentric considerations that underly the NIMBY effect are deactivated and transformed into sociotropic considerations following the burden-sharing policies. People support fair allocation policies not because they themselves will be better off under such policies, but despite the fact that they will have to carry a larger share of the burden of hosting and integrating asylum seekers in their local communities.

Discussion

In the following decades, countries may face growing numbers of forced migration from the developing world. While many countries have been fortifying their borders and taking other measures that were aimed to slow down immigration, many also kept international commitments and maintained their policy of accepting asylum seekers. When a humanitarian crisis breaks out at the border, policymakers and political leaders face a dilemma. On the one hand, they are required to follow international law and agreements. On the other hand, such situations challenge national sovereignty and spread fear that sparks a public backlash against immigration. The motivation underlying this study was to examine whether the policies that manage the geographic dispersal of refugees in destination countries can cool down this hostile atmosphere while maintaining refugee admissions at the same time.

In shaping how countries manage immigration and refugee settlement, one crucial factor is the degree to which society is capable of acting collectively, utilising the capacity of the nation to overcome challenges. A widespread problem that interferes collective action in the context of refugee accommodation is NIMBYism. Local resistance often emerges when the government aims to distribute the national burden across the country. Conversely to the conventional wisdom, however, the evidence I presented here demonstrates that sociotropic and civic minded tendencies make citizens willing to share the burden of refugee settlement and integration. The probability that they would respond that way or the other is, to an important extent, determined by the policy enacted by the government. When refugee allocation is regulated and guided by a clear allocation rule, the anti-immigrant backlash is attenuated. Citizens turn more supportive of refugee incorporation despite the heavier burdens that they are required to bear. As was argued by Schattschneider (Citation1935) more than eighty years ago, new policies create a new politics.

Dispersal policies were previously examined by their economic effect on immigrant long-term integration. Since they generate quasi-random assignment, they were used to identify the causal effect of ethnic enclaves on immigrant integration. Previous work exploiting such quasi-experimental settings found that living in locations with more co-ethnics enhances economic integration (Damm, Citation2009; Martén et al., Citation2019). This seemingly suggests that policymakers could be facing a tradeoff before enacting dispersal policies: Economically, less concentrated ethnic enclaves harm immigrant integration. But politically, the public backlash is attenuated, and political stability is reinforced.

However, this trade-off might be an illusion. Less sophisticated identification strategies produced mixed findings, showing that in many cases ethnic enclaves hinder immigrant integration (Borjas, Citation2000; Chiswick & Miller, Citation2005). While the use of quasi-random assignment produced by dispersal policies have better addressed the problem of migrants self-selecting their place of residence in a certain country (i.e., addressing concerns about internal validity), these policies might have also affected the empirical association between ethnic enclaves and immigrant integration (i.e., raising concerns about external validity). In other words, the effect revealed in such natural experiments is very likely to be a local treatment effect. It is possible that larger ethnic enclaves enhance economic integration only given dispersal policies. This might be driven by tighter regulation over immigrant integration under dispersal policies. Alternatively, this empirical relationship might be positive only when ethnic clusters are overall moderate, which is more likely to happen under dispersal policies. Therefore, the alleged trade-off pertaining to the economic and political effects of ethnic enclaves is worthy of further investigation.

Notably, the economic integration of immigrants is important not only for the well-being of immigrants, but also because it is strongly associated with more positive public attitudes toward immigration. Yet while the political implications of enhanced economic integration are a long-term investment, political leaders often search for more immediate solutions to critical social problems, such as anti-immigrant backlash and increasing polarisation, which could also have long-term ramifications. This is remarkably relevant in times of crisis when the anti-immigrant backlash is so strong it can destabilise politics in meaningful and persistent ways. The evidence I presented here demonstrated that dispersal policies and burden-sharing mechanisms can provide such solutions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (83.3 KB)Acknowledgements

For valuable feedback I thank Dominik Hangartner, Guy Grossman, Yotam Margalit, Margaret Peters, Yael Shomer, Shir Raviv, two anonymous referees, as well as the participants at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Political Science Association and the Penn Development Research Initiative's 2021 conference entitled ‘Barriers and Bridges to Immigrants’ Integration’. I am also grateful to Michal Shamir, Mark Peffley and Marc Hutchison who generously allowed me to run my experiments in their panel survey project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 ‘What we are seeing in these figures is further confirmation of a longer-term rising trend in the number of people needing safety from war, conflict and persecution.’ The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi (UNHCR, Citation2018).

2 Notably, the cross-national heterogeneity in the electoral effects of local immigration is large, suggesting that local immigration may be important for the success of anti-immigrant parties in certain settings but not in others (Cools et al., Citation2021). In Norway, for example, Sørensen (Citation2016) shows that immigration from non-Western countries has increased electoral support for the Progress Party, but these effects are modest and tend to dissipate over time.

3 Notably, ‘ethnic residential segregation’ in Scandinavian countries is a broader concept that relates not only to refugees but also includes the geographical clustering of various immigrant groups from diverse countries of origin.

4 For example, Clayton et al. (Citation2022) show that NIMBY attitudes toward refugees are ‘nearly universal, and are consistent across countries as well as subgroups of individuals with varying ideologies,’ while Bansak et al. (Citation2016) find strong evidence that sociotropic considerations shape public attitudes toward asylum seekers across 18 European countries.

5 The term NIMBYism is used to describe almost any land use opposed by local residents, including affordable housing, detention centres, drug treatment facilities, asylum centres, homeless shelters, waste facilities, industrial facilities, and energy facilities (Dear, Citation1992).

6 The literature on international burden-sharing offers a parallel distinction between interest-based and norm-based motivations in state responses to refugees (Thielemann, Citation2003). Since the units of analysis in this study are individual citizens, not states, and the political context is national rather than international, I follow the terminology used in extant research on citizens’ attitudes toward refugees (Bansak et al., Citation2016; Ferwerda et al., Citation2017).

7 Appendix A provides data on the use of refugee dispersal policies, average levels of public opposition to refugees, and other contextual factors in Norway, Israel, and other high-income democracies.

8 Statistics Norway, available at: https://www.udi.no/en/statistics-and-analysis/statistics/asylsoknader-etter-statsborgerskap-og-maned-2015/.

9 See, for example: ‘UNHCR and Israel sign agreement to find solutions for Eritreans and Sudanese.’ Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2018/4/5ac261bd4/unhcr-israel-sign-agreement-find-solutions-eritreanssudanese.html.

10 I use data on Syrian nationals instead of Syrians with official refugee status because data on the latter at the municipality level is restricted. However, since there were less than 1500 Syrian immigrants living in Norway before the Syrian civil war, data on Syrian residents after 2015 mostly captures Syrian asylum seekers and refugees (Tønnessen et al., Citation2020).

11 Statistics Norway, available at: https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/flyktninger/aar/2017-06-20.

12 However, the response of policy-makers and employees responsible for refugee housing in Norwegian municipalities do not necessarily reflect changes in citizens’ attitudes toward refugee admission.

13 This paper uses data from the Norwegian Citizen Panel waves 5 and 12 (Ivarsflaten et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The Norwegian Citizen Panel was financed by the University of Bergen (UiB). Data collection was coordinated by UiB, implemented by Ideas2Evidence, and distributed by Sikt and UiB. The Norwegian Citizen Panel 2018 methodological report is available at: https://www.uib.no/en/citizen.

14 Instead of voting in a referendum, another experimental condition randomly assigned the following: ‘Imagine that your municipal council is voting on this proposal. Would you like your municipal council to vote for or against the proposal on your behalf.’ However, this treatment has no effect on respondents’ attitudes. The effect of the Neighbouring Municipality treatment is substantively identical for respondents in the Referendum and the Municipal Council treatment groups.

15 To have a ‘clean control’ group that does not include individuals living in proximity to asylum centres, respondents who reported that there is an old asylum centre in their local area (established before 2015) are coded as missing for the ‘new asylum center in local area’ variable. However, as column 2 shows, results are substantively similar using the (either new or old) ‘asylum center in local area’ variable.

16 Unlike most asylum seekers in other host countries, Eritreans and Sudanese asylum seekers received temporary collective protection and a ‘conditional release visa’, which they were required to renew every two or three months. They also did not receive formal work permits.

17 See Appendix Section F for the complete question protocol.

18 Explicit measures are also analysed later on.

19 See Appendix Section G for the complete question protocol.

References

- Adida, C. L., Lo, A., & Platas, M. R. (2018). Perspective taking can promote short-term inclusionary behavior toward Syrian refugees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(38), 9521–9526. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804002115

- Andersson, R., Brattbakk, I., & Vaattovaara, M. (2017). Natives’ opinions on ethnic residential segregation and neighbourhood diversity in Helsinki, Oslo and Stockholm. Housing Studies, 32(4), 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2016.1219332

- Askim, J., & Steen, A. (2020). Trading refugees: The governance of refugee settlement in a decentralized welfare state. Scandinavian Political Studies, 43(1), 24–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12158

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2016). How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers. Science, 354(6309), 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag2147

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2017). Europeans support a proportional allocation of asylum seekers. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(7), 0133. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0133

- Blair, G., McClendon, G. (2021). Conducting experiments in multiple contexts. In J. N. Druckman & D. P. Green (Eds.), Advances in experimental political science (pp. 411–428).

- Borjas, G. J. (2000). Ethnic enclaves and assimilation. Swedish Economic Policy Review, 7(2), 89–122.

- Briggs, R., & Solodoch, O. (2021). Changes in perceptions of border security influence desired levels of immigration. OSF Preprints.

- Bygnes, S. (2020). A collective sigh of relief: Local reactions to the establishment of new asylum centers in Norway. Acta Sociologica, 63(3), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699319833143

- Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2005). Do enclaves matter in immigrant adjustment? City & Community, 4(1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1535-6841.2005.00101.x

- Clayton, K., Ferwerda, J., & Horiuchi, Y. (2022). The stability of not-in-my-backyard attitudes toward refugees: Evidence from the Ukrainian refugee crisis. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4126536.

- Cools, S., Finseraas, H., & Rogeberg, O. (2021). Local immigration and support for anti-immigration parties: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 65(4), 988–1006. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12613

- Damm, A. P. (2009). Ethnic enclaves and immigrant labor market outcomes: Quasi-experimental evidence. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(2), 281–314. https://doi.org/10.1086/599336

- Day, M. V., Fiske, S. T., Downing, E. L., & Trail, T. E. (2014). Shifting liberal and conservative attitudes using moral foundations theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(12), 1559–1573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214551152

- Dear, M. (1992). Understanding and overcoming the nimby syndrome. Journal of the American Planning Association, 58(3), 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369208975808

- Dinas, E., Matakos, K., Xefteris, D., & Hangartner, D. (2019). Waking up the golden dawn: Does exposure to the refugee crisis increase support for extreme-right parties? Political Analysis, 27(2), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.48

- Dustmann, C., Vasiljeva, K., & Piil Damm, A. (2019). Refugee migration and electoral outcomes. The Review of Economic Studies, 86(5), 2035–2091. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdy047

- Eurostat. (2019). Asylum and first time asylum applicants - annual aggregated data. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TPS00191/default/table

- Fasani, F., Frattini, T., & Minale, L. (2022). (The struggle for) refugee integration into the labour market: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 22(2), 351–393. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbab011

- Ferwerda, J., Flynn, D., & Horiuchi, Y. (2017). Explaining opposition to refugee resettlement: The role of nimbyism and perceived threats. Science Advances, 3(9), e1700812. pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700812

- Finseraas, H., & Strøm, M. (2022). Voter responses to refugee arrivals: Effects of settlement policy. European Journal of Political Research, 61(2), 524–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12461

- Gibson, T. A. (2005). Nimby and the civic good. City & Community, 4(4), 381–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2005.00144.x

- Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2014). Public attitudes toward immigration. Annual Review of Political Science, 17(1), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818

- Hangartner, D., Dinas, E., Marbach, M., Matakos, K., & Xefteris, D. (2019). Does exposure to the refugee crisis make natives more hostile? American Political Science Review, 113(2), 442–455. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000813

- Hankinson, M. (2018). When do renters behave like homeowners? High rent, price anxiety, and nimbyism. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000035

- Hellevik, O., & Hellevik, T. (2017). Changing attitudes towards immigrants and immigration in Norway. Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning, 58(3), 250–283. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-291X-2017-03-01

- Hernes, V. (2017). Central coercion or local autonomy? A comparative analysis of policy instrument choice in refugee settlement policies. Local Government Studies, 43(5), 798–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1342627

- Ivarsflaten, E., Andersson, M., Arnesen, S., Bjånesøy, L., Nordø, Å., & Tvinnereim, E. (2020a). Norwegian citizen panel, wave 5 (October - November 2015) [Dataset], v101. Data available from Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.18712/NSD-NSD2343-V7

- Ivarsflaten, E., Dahlberg, S., Arnesen, S., Peters, Y., Knudsen, E., Bjånesøy, L., Bygnes, S., Tvinnerheim, E., Böhm, G., Bærøe, K., Cappelen, C., & Eidheim, M. (2020b). Norwegian citizen panel, wave 12 (June 2018) [Dataset], v101. Data available from Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.18712/NSD-NSD2605-V3

- Kahan, D. M. (2003). The logic of reciprocity: Trust, collective action, and law. Michigan Law Review, 102(1), 71–103. https://doi.org/10.2307/3595400

- Kalla, J. L., & Broockman, D. E. (2020). Reducing exclusionary attitudes through interpersonal conversation: Evidence from three field experiments. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000923

- Kaufmann, E. (2018). Whiteshift: Populism, immigration and the future of white majorities. Penguin UK.

- Martén, L., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2019). Ethnic networks can foster the economic integration of refugees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(33), 16280–16285. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820345116

- Meehl, P. E. (1977). The selfish voter paradox and the thrown-away vote argument. American Political Science Review, 71(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/1956951

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1935). Politics, pressures and the tariff.

- Shechory-Bitton, M., & Soen, D. (2016). Community cohesion, sense of threat, and fear of crime: The refugee problem as perceived by Israeli residents. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 14(4), 290–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377938.2016.1187237

- Søholt, S., & Aasland, A. (2021). Enhanced local-level willingness and ability to settle refugees: Decentralization and local responses to the refugee crisis in Norway. Journal of Urban Affairs, 43(6), 781–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1569465

- Solodoch, O. (2021a). Do sociotropic concerns mask prejudice? Experimental evidence on the sources of public opposition to immigration. Political Studies, 69(4), 1009–1032. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720946163

- Solodoch, O. (2021b). Regaining control? The political impact of policy responses to refugee crises. International Organization, 75(3), 735–768. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000060

- Sørensen, R. J. (2016). After the immigration shock: The causal effect of immigration on electoral preferences. Electoral Studies, 44, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.06.009

- Thielemann, E. (2003). Between interests and norms: Explaining burden-sharing in the European Union. Journal of Refugee Studies, 16(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/16.3.253

- Tomberg, L., Stegen, K. S., & Vance, C. (2021). “The mother of all political problems”? On asylum seekers and elections. European Journal of Political Economy, 67, Article 101981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2020.101981

- Tønnessen, M., Drahus, K. M., & Dzamarija, M. T. (2020). Demographic profile of Syrians in Norway. In E. D. Carlson & N. E. Williams (Eds.), Comparative demography of the Syrian diaspora: European and Middle Eastern destinations (pp. 281–301). Springer.

- UNHCR. (2018). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2018 (tech. rep.).

- Valentino, N. A., Soroka, S. N., Iyengar, S., Aalberg, T., Duch, R., Fraile, M., Hahn, K. S., Hansen, K. M., Harell, A., Helbling, M., Jackman, S. D., & Kobayashi, T. (2017). Economic and cultural drivers of immigrant support worldwide. British Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 1201–1226. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712341700031X

- Yaar, E., & Hermann, T. (2018). Peace index January. The Israel Democracy Institute. http://www.peaceindex.org/files/PeaceIndexDataJanuary2018-Eng.pdf