?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The identification of problem information is an important driver of political attention in parliament. This is widely acknowledged in the literature on party competition but there has been surprisingly little empirical research on the extent and when it matters. By relying on an extensive cross-country data set matching data on the policy content of parliamentary oral questions from ten European parliamentary democracies with well-established problem indicators (economy, immigration, and terrorism), this study sets out to answer these important questions. Our time series analysis reveals that not all problem indicators drive political attention in parliament to the same extent and that responsiveness varies based on differences in how government and opposition parties strategically take up problems as well as a partisan logic between left and right parties. While real world problem indicators can be a strong driver of parliamentary attention, that drive is still filtered through political and institutional processes.

Political parties play a key role in democratic representation by acting as the main transmission belt between society and political institutions. To respond to public priorities under conditions of limited attention resources, they must be constantly on the lookout for cues on what the public cares about the most. Signals can be found in the media, in public opinion polls, by interacting with constituents and various forms of interest groups, as well as by monitoring protest events. That said, parties are not merely tracking and reflecting societal demands. Once politicians are elected in decision-making positions, they also fulfil the role of problem solvers, by either detecting or anticipating a possible deterioration in an issue area. In this regard, the development of problem indicators measuring changes in the status quo is of fundamental importance (Green-Pedersen, Citation2019, Citation2020; Kingdon, Citation2011, p. 90). If, for instance, extant statistics point to surges in unemployment or immigration flows in the country, parties can represent public priorities by focusing their attention on those issues (Mansbridge, Citation2003; Pitkin, Citation1967). This is a basic yet often overlooked type of representation that exists along other more researched lines of representation such as the representation of public preferences (Elsässer et al., Citation2021; Gilens, Citation2005; Wlezien, Citation1995).

The linkage between problem indicators and party issue attention has been widely acknowledged both in the policy agenda and party competition literatures. The former has had the merit of drawing attention to how political organisations process (collect, interpret, and prioritise) the constant flow of information from the environment (e.g., Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005; Kingdon, Citation2011). The latter used this insight to study parties’ issue selection strategies, especially during electoral campaigns, and showed that parties are constantly factoring in changes in indicators related, for example, to the state of the economy (Calca & Gross, Citation2019; Greene Citation2016; Pennings, Citation1998; Traber et al., Citation2020), immigration (Grande et al., Citation2019; Green-Pedersen & Krogstrup, Citation2008; Green-Pedersen & Otjes, Citation2019; Wouters et al. Citation2021), the environment (Green-Pedersen & Wolfe, Citation2009; Spoon et al., Citation2014) and inequality (Tavits & Potter, Citation2015). On the contrary, only a few studies have analysed the extent to which parties in parliament also react systematically to societal problems (e.g., Bevan et al., Citation2019; Borghetto & Russo, Citation2018).

Studying party responsiveness to problems through their parliamentary activities is crucial to understanding their overall strategic behaviour. According to the vast literature on party issue competition, parties are constantly involved in a struggle to control the party-system agenda, the overall hierarchy of issues dominating political discussions in a country, since winning some of those battles increases the chances that their policy proposals are adopted and, eventually, give them an edge in the electoral race (Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Citation2010). Parliamentary assemblies represent a particularly relevant venue to engage in the issue competition game (Otjes & Louwerse, Citation2018). First, they provide a regulated and institutionalised battleground where even smaller competitors are granted some floor time and visibility – which can make up for disadvantages in terms of resources and prominence. Second, parliamentary agendas have wider political effects, as they constantly interact with other key agendas, such as government, media, and public agendas. Finally, the issue of debate correlates with the issue eventually put to a vote on the floor. Parliamentary debates are an opportunity for parties willing to both bring attention to problems and discuss solutions. What is missing from the overall picture is a systematic cross-country analysis of the impact of exogenous signals about multiple societal problems on party attention in parliament.

We capture parliamentary agendas by mapping the issue content of oral parliamentary questions to the government submitted by political parties in parliamentary democracies. While so-called ‘question time’ is regulated differently across political systems (Borghetto & Chaqués-Bonafont, Citation2019; Serban, Citation2022), they all allow MPs to press the Prime Minister or another cabinet member to address a particular issue. Analysing these debates presents three advantages for our analysis of problem responses in parliament. First, they fit with our focus on parliamentary attention. Since parliamentary debates receive some degree of media coverage, and they are conducted according to a tight time schedule, party elites normally strategize questions asked by their group members. Second, although the prevalent perspective is that these activities are mainly used for oversight purposes to extract information from the executive as well as to hold the executive to account (Bailer, Citation2011; Bundi, Citation2018; Höhmann & Sieberer, Citation2020; Martin & Whitaker, Citation2019; Zittel et al., Citation2019), studies show that parties also use them to put issues onto the political agenda (Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Citation2010; Seeberg, Citation2013).

In this paper, we study the extent to which signals about potential societal problems in three issue areas – unemployment, immigration, and terrorism – are picked up by legislators in ten European countries and influence the content of their parliamentary questions. Although the importance of indicators as drivers of political agendas has already been acknowledged in the agenda-setting literature (Kingdon, Citation2011, ch.5), the diffusion of constantly updated statistical indicators due to the digital revolution and the monitoring work of public and private actors justifies a renewed attention for this topic (Kelley & Simmons, Citation2015). While acknowledging that politicians might try to use or portray problems in certain ways (Rochefort & Cobb, Citation1993; Stone, Citation2002; Kingdon, Citation2011, p. 94) and that policymaking can influence problem severity (a tight monetary policy can increase the unemployment rate), the social construction of societal problems should not be exaggerated. No responsible politician can deny or neglect terrorism or unemployment (Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Citation2010). As Kingdon eloquently puts it, a ‘countable problem acquires a power of its own unmatched by problems that are less countable’ (Citation2011:, p. 93; see also Jones and Baumgartner, Citation2005, p. 209; DeLeo & Duarte, Citation2022; Kristensen, Citation2020).

To ease the language, in the following we will refer to these as problems rather than statistical indicators. We focus on these three issues since they have been central and enduring concerns for parties and voters alike in Europe. Importantly, these issues provide a fertile ground for generalisations based on their variation in terms of party issue ownership: left-wing parties are usually deemed more competent on unemployment issues, right-wing parties on immigration, while no side can boast an advantage as far as the response to terrorism is concerned.

Our findings show that not all problem indicators equally drive political attention in parliament. Statistics on unemployment rates, immigration rates, and terrorism trigger a general party responsiveness in our analyses. Secondly, our findings suggest that, as expected, those actors that respond more readily to changes in political indicators are mainly groups in the opposition. However, the response of left and right parties to issues based on competency is mixed, although a clear partisan effect on responsiveness is found. By unpacking the agenda decisions of parliamentary groups, we show that, at least in part, parties tend to strategically use information flows about problems to their advantage in the issue competition game.

Problems drive party attention in parliament

Problem-solving is a first-order interest of political parties (Heclo, Citation1974; Petrocik, Citation1996; Stokes, Citation1963; Strom, Citation1990). Indeed, most parties formed more than a century ago to address the problems of their reference social groups such as, social democratic parties and workers’ labour market risks (Hibbs, Citation1977). On the other hand, a profound transformation in party system competition paralleled the progressive shift in European electoral politics from class-based voting towards issue-based voting (Thomassen, Citation2005). For the last thirty to forty years, parties have been competing for votes not only by taking positions on specific ideological dimensions but also, and increasingly, by forcing other parties to focus on the proposer’s preferred issues that they would rather disregard. ‘Issue competition […] is about getting the issues that a party prefers to dominate the party political agenda’ (Green-Pedersen, Citation2007, p. 609).

In order to capture this complementary logic, scholars developed concepts such as issue ownership (Petrocik, Citation1996), competence (Green & Jennings, Citation2012), and valence (Abney et al., Citation2013; Green, Citation2007). All underline the relevance of problem-solving credibility for both parties and voters: voters (e.g., environment-minded citizens) tend to vote for the party (e.g., the green party), which is most competent to handle the problems (e.g., forest protection) that the voters are concerned about.

Even if parties are already intrinsically motivated to tackle problems, the central tenet of representative democracy, the accountability mechanism, provides strong incentives. Voters elect parties to office based on the expectation that the parties address problems that emerge or remain unresolved, and the voters hold them to account on election day (Fiorina, Citation1981; Key, Citation1966, p. 196). This means that it can be difficult – if not dangerous – for an election-motivated party to ignore societal problems. Under certain circumstances, ‘inaction is a decision’ (Kingdon, Citation2011, p. 96), so much that ignoring focusing events like shark attacks or football results may affect the incumbent vote (Achen & Bartels, Citation2017; Healy et al., Citation2010). Research on especially the economy and economic voting shows how well this mechanism operates (e.g., Marsh & Tilley, Citation2010). If unemployment soars, for instance, the government is likely to be held responsible and punished at the polls (Lewis-Beck & Paldam, Citation2000). Punishment does not always lead to electoral defeat just as a good economy is not a guarantee of electoral victory (Froio et al., Citation2017), but ignoring the problem entirely is likely to make any outcome worse for the government.

Hypothesis 1: Parties attend to problems. When a problem status indicator indicates a negative development on an issue, parties attend more to that issue.

Hypothesis 2: Parties attend more to problems when they are in opposition.

Hypothesis 3: Parties attend more to problems on issues on which they have issue ownership.

In summary, our focus is first to ascertain if parties generally attend to problems (H1), and second to unpack the variation underlying this general trend by contrasting a government-opposition logic (H2) with a partisan left-right logic (H3).

Data and methods

To test our arguments, we make use of data from the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP; www.comparativeagendas.net) across ten countries on parliamentary questions asked by multiple parties. We selected our issues due to their relevance in modern politics and because they can be tracked by means of relevant statistical indicators measured regularly over time and across countries. This means that we do not cover very slow-moving statistical indicators that are measured less often such as life expectancy (health), literacy (education), the number of elderly or children (that creates pressure on either elderly care or childcare), or poverty (social issues). We use three problem indicators that are measured regularly and are publicly available from international sources across nations. These data sources allow long cross-national time series. Moreover, we selected issues over which the EU does not have exclusive authority, (e.g., monetary policy in the Eurozone), and that are not explicitly delegated to the local level of governance (e.g., education policy in the UK or health policy in Italy).Footnote2

For each of our countries, we aggregate the monthly unemployment rate and the annual rate of immigrants (in millions) collected by the OECD as well as the monthly count of casualties from terrorism attacks in each country collected by the Global Terrorism Database to match our quarterly parliamentary questions data. We focus on quarterly data to help avoid gaps in the data due to the nature of parliamentary calendars. As the immigration rate is only available annually, we repeat this measure in each quarter which matches how total immigration is normally discussed throughout the year.Footnote3 To ensure a high level of comparability, we only use indicators collected consistently by an international body and refrain from combining data from separate national sources. Our three problem indicators are arguably central indicators for each issue area at the national level in most advanced democracies. If they indicate a negative development (marked by a higher level for each of the three indicators), voters and the media can be expected to focus on them, and parties will be more pressured to address the problem. The ubiquity and generally wide publicisation of these measures by the media and relatedly broad knowledge of these measures by the public further reinforces that pressure. These measures also reflect the selection of established indicators that are used in previous studies (Bevan et al., Citation2019; Seeberg, Citation2020).

Problem indicators that change a lot during a short period of time pose a challenge when studying party attention to indicators. Many commonly used data sources on party attention are ill-suited to reveal how parties attend to fluctuations in indicators because they are either annual, such as the government’s executive speeches (Mortensen et al., Citation2011), or published only at elections, such as the party manifesto data (Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Citation2014; Volkens et al., Citation2014). Hence, in line with much previous research (e.g., Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Citation2010; Vliegenthart & Walgrave, Citation2011), we rely on parliamentary questions that are asked typically on a weekly or bi-weekly basis.

Our data include all parliamentary questions asked for extended time periods in Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. We selected this large number of countries to ensure variation in institutional settings, thus enhancing the possibility to infer our findings to other advanced democracies. In terms of the institutional setting, most countries are parliamentary democracies (except for France which features a semi-presidential system) but present important variations in terms of party fragmentation, the presence of niche parties, the length of the electoral cycle as well as a mixture of majority, coalition, and even minority governments (see ). Moreover, the countries feature considerable variation in terms of institutional rules and norms of parliamentary agenda-setting (discussed below), which should limit the possibility that our findings are dependent on a certain parliamentary setup.

Table 1. Available country data sets.

While the varying time periods for each series do prevent direct comparisons, by including as much data as was available at the time this study was carried out, we are able to offer the most comprehensive view of the problem response through parliamentary questions to date. The online Appendix includes plots of the distributions for both parliamentary questions and the main indicators by country.

In terms of the institutional rules and norms of parliamentary agenda-setting, scholars in general note that party discipline is imposed to a much lower extent in non-legislative activities compared to, for instance, roll-call votes or bill introductions where individual members are expected by the party leader to abide by her instructions (Martin, Citation2011, p. 263). Even so, parliamentary groups still play a gatekeeping role because they are given limited question time (particularly in the Netherlands, see Louwerse & Otjes, Citation2019). MPs therefore must make trade-offs, and attention to a problem always comes at a price. That said, even a cursory look at procedures regulating parliamentary questioning across countries reveals some significant variation (Serban, Citation2022). In countries like Denmark, for instance, oral as well as written parliamentary questions offer members of parliament a great deal of freedom to promote an individual agenda (Garritzmann, Citation2017). In other countries such as Italy, each parliamentary group is allowed only one question during each weekly session, so – in light of the tight agenda – decisions about the content of the questions have to be coordinated at the party level (Russo & Cavalieri, Citation2016). In countries like Portugal, only frontbenchers are allowed to take the floor and address the Prime Minister during the bi-weekly question time, and time is distributed proportionally to the size of the parliamentary group (Belchior & Borghetto, Citation2019). Finally, there are countries, like Spain in the 1990s and early 2000s, where government parties also had a strong incentive to participate in question time (Chaques-Bonafont et al., Citation2015). The online Appendix presents an overview of the procedures in force in our ten countries.

Another distinction drawn by most scholars is between written and oral questions. Studies point out that parliamentarians have a greater leeway when they use written questions than when they use oral questions, which are not constrained by time limits and are not discussed on the public stage (televised sessions), so they are not as salient for the party image. The expectation is that these instruments present a rare opportunity for individual members to signal their positions to their constituents (Russo, Citation2011; Saalfeld, Citation2011). Our empirical analysis incorporates these important insights by focusing, firstly, only on oral parliamentary questions (other studies already showed how oral parliamentary questions function in similar enough ways in general for meaningful pooled analyses; e.g., Garritzmann, Citation2017; Vliegenthart et al., Citation2016; see also Borghetto & Chaqués-Bonafont, Citation2019). Second, we control for the size of each party and therefore the number of questions available to each party since the former generally influences the latter in most parliaments. To accomplish this, we include a measure of party seat share at the beginning of the legislature provided by the ParlGov database (Döring et al., Citation2022). In addition, we control for the quarter immediately before an election to account for the changes in the activity that is often noted in the run up to an election (e.g., Sagarzazu & Klüver, Citation2017; Seeberg, Citation2022).

We use two additional variables to test the problem-to-question correspondence across institutional and political lines in H2 and H3. Since we know the party affiliation of each question asker, we can distinguish questions asked by members of opposition from those asked by members of government using information from the ParlGov database (Döring et al., Citation2022). We use this information to create a government/opposition dummy variable to split our analyses and test H2. We further use the oft-used left-right party position on economic issues from the Chapel Hill data set (LRECON) to gauge the party stance on the role of government in the economy.Footnote4 The LRECON-score ranges from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right). We interact this variable with our problem measures as a test of the conditioning effect presented in H3. presents the descriptive statistics for our dependent and independent variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Comparative agendas project coding

As part of the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP; Baumgartner et al., Citation2019), the coding of the parliamentary questions has been carried out by trained research assistants in each country. In practice, each parliamentary question is coded to show whether it is about fisheries, psychiatry, domestic violence, etc. using the more than 200 issue subcategories in the CAP codebook (Baumgartner et al., Citation2019; Bevan, Citation2019). To overcome uncertainties in exactly which subcategory to use for a parliamentary question and to match the content of the parliamentary question to the problem indicators, we group the parliamentary questions that are topically closely related (the online Appendix provides an overview of the subtopics for each issue area of the analysis). Importantly, by using a common coding system across nations, we can analyse problems and parliamentary questions from parliament to parliament and cabinet to cabinet.

This coding procedure does not identify if a parliamentary question explicitly refers to a statistic. The procedure therefore only allows us to analyse whether a change in a statistical indicator sparks more party attention to the issue area to which the indicator belongs. Such an analysis comes close to the argument; statistics that reveal more immigrants for example encourage party attention to various questions on the issue, such as immigrant rights, immigrant discrimination, welfare to immigrants, etc. The point is that attention does not have to be specifically about the statistic in order to build on it or spur from it.

Estimation

To conduct our analyses, we make use of Error Correction Models (ECMs) models with panel-corrected standard errors and fixed effects by country. The unit of analysis is party-quarter within country for each issue. The use of ECMs allows us to account for changes in the number of questions asked by a party within each country from quarter to quarter. It further allows us to look at long-term effects from the level of each problem measure as well as short-term effects based on the change in these measures from the previous quarter. Across our three issues and ten countries, we have varying numbers of observations based on available data as of Spring 2022 (see also ). The use of panel-corrected standard errors for time series analyses is common with CAP data due to the partial dependence between issues through the use of CAP coding which assigns a single topic/issue to each observation. Only parties with more than four years (16 quarters) in parliament are included in our analyses. While time in parliament certainly affects the professionalism of parties, this restriction helps us exclude very short panels and remains fairly inclusive compared to the norm of 30+ time points for most time series analyses.

The ECMs in this paper take the following common form:

(1)

(1) where changes in the number of questions asked by a particular party in a quarter (

) are a function of the long-run level of problems (

), and short-run changes in problems (

), and the interaction of both with the Chapel Hill Left/Right economy measure (

). In the model, the lagged dependent variable (

) measures the speed of re-equilibration (

) back to the status quo level of questioning on the issue. The coefficient for the lagged dependent variable is expected to be negative and take a value between 0 and – 1. If the value was over 0 or below – 1 that would indicate an explosive process of unchecked continuing reactions or a cycling of under and over reactions. In other words, increasingly more and more questions or alternating periods of no and very high numbers of questions, something that is not seen in the data. The model also includes controls for the share of seats held by the party (

) and if the previous quarter included an election (

). Finally, the models are split by a government/opposition dummy variable that indicates if the observation is of a government or non-government political party at time t.

Analysis

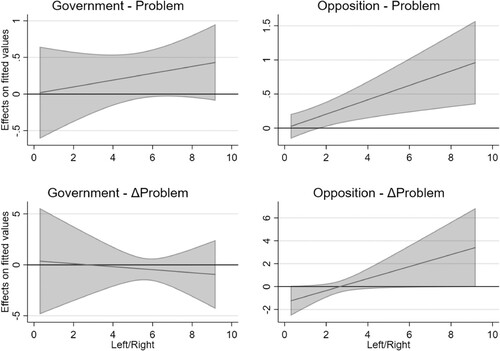

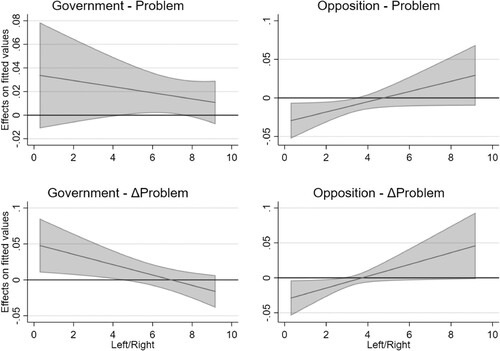

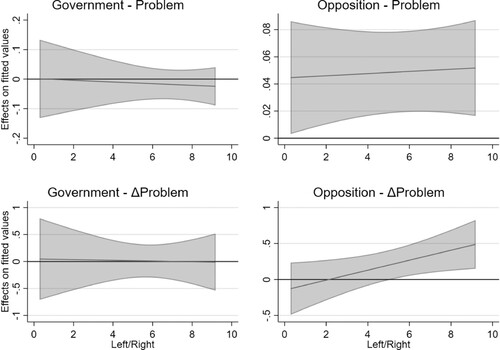

To test our hypotheses, reports regressions of parliamentary questions asked respectively by government and opposition parties across our ten countries on the immigration rate, terrorism incidents, and the unemployment rate (thus the table includes six models in total). One government and one opposition model for each of the three issues allows us to test H2, namely whether parties attend more to problems when in opposition. All models include interactions between our problem indicators and the party’s left-right position, our controls, and country-fixed effects. The interaction terms allow us to test H3, namely whether parties attend more to problems on issues on which they have issue ownership. Three sets () of four marginal effects plots were used to ease the visualisation of the effects of problems on our dependent variable conditional on a party’s left-right position.Footnote5 In the plots, we distinguish long-run level effects from short-term change effects. We turn to these plots first, before discussing the direct results for our error correction term and control variables later in this section.Footnote6

Table 3. Parliamentary questions on immigration, terrorism, and employment.

Hypothesis 1 anticipates that parties ask more parliamentary questions if the problem indicators suggest a worsening situation. Our findings in large part offer support for Hypothesis 1. Opposition parties generally respond to the level of problem measures in immigration and employment denoted by the estimated marginal effects being generally greater than 0 in the upper-right corner of and . They also react with a positive marginal response to changes in problem measures for immigration and terrorism (lower-right corners of and ). Regarding questions asked by government parties, there are significant positive effects for changes in terrorism (the line is above zero in most parts of the lower-left corner of ). All in all, the results offer varying degrees of support for Hypothesis 1 in all three issues, suggesting that parties use parliamentary questions to respond to problems. In terms of generalizability, we analyse issues that are often salient to the public, and our findings might therefore indicate an upper bound compared to less salient issues, which politicians might be less concerned about (cf. Busemeyer et al., Citation2020). We discuss the clear institutional and partisan variation through our remaining two hypotheses.

Hypotheses 2 and 3 extend our previous question to ask to what extent party responsiveness by way of parliamentary questions varies in government or opposition (H2) and by party ideology (H3). As demonstrated from the previous discussion, the majority of significant and marginally significant positive results for both the level and change in problems are for opposition parties. These findings offer clear support for H2: opposition parties use parliamentary questions more than government parties to attend to rising problems. The fact that we control for seat share, elections, use country fixed effects, and employ panel corrected standard errors reassures us that these effects are not driven by factors like large mainstream parties or by countries with a particular institutional structure.

The interpretation of Hypothesis 3 is more complex. Starting from immigration (), the significant and marginally significant effects for opposition parties are clearly stronger or only become significant (or marginally significant) as we consider parties toward the right end of the ideological spectrum. As expected by H3, rightwing parties are swifter to react to worsening immigration statistics – an issue on which they are seen as relatively more competent – and drive attention to the issue by means of parliamentary questions.

Right wing opposition parties also tend to be more responsive to increases of terrorist actions (), although the effects are only marginally significant in relation to short-term problem changes. The reverse is true in government though, which offers conflicting support for H3. While no parties are viewed as inherently competent on terrorism as an issue, we would expect these results to at worst be party neutral or if terrorism was viewed as a law-and-order concern, potentially right leaning.

The effects for employment in are also somewhat mixed. Both left and right opposition parties clearly respond to the level of the problem (upper right corner of ), but the effect slightly increases at higher left/right values. A similar pattern applies when we consider the effects for a change in employment (lower-right corner of ), which become positive and statistically significant for right-leaning opposition parties. However, the effect on questions asked by government parties is not conditioned by their left-right ideological profile. Overall, this finding runs counter to Hypothesis 3, based on the argument that parties from the left should own employment-related issues. On the other hand, it could be argued that the detected patterns are supportive of Hypothesis 3 if the measure of unemployment rate simply works as a proxy for the economy and not just for distress in the job market making it a right-owned issue. Overall, the results for Hypothesis 3 are supportive of differing left/right effects, but do not cleanly fit our expectations about how issues are owned which may in part be due to the comparative nature of our analyses.

A complete test of our hypotheses also requires a discussion of effect sizes. Importantly, the directly calculable effect sizes are for a single opposition or government party and therefore only represent a part of the full effect. For the immigration models, the inflows are measured in millions of immigrants within the year. In (upper right), 1 million immigrants entering the country in a year would be expected to lead to approximately one additional question per quarter for the farthest right party. In the case of terrorism in (lower left), the most left leaning party in government would be expected to ask one additional question if the number of terrorist caused deaths increased 20-fold. The effect of the level of employment in (upper right) is similar across all parties with approximately 20 per cent unemployment expected to lead to an additional question for all parties on both the left and right. In all cases, the full effects on the number of questions depends on the positions and the number of parties in government/opposition and within the significant region on the left/right scale. For example, if there were 4 parties in the opposition, 5 per cent unemployment would lead to an average of one additional question from the opposition as a whole.

Our error correction rates are represented by the coefficient for the lagged questions measure in the model (see ). As noted above, this value represents how quickly the series returns to equilibrium (the average number of questions on the issue) following a shock, such as a response to a problem measure. All of these values are significant in and take on values between – 0.583 and – 0.878, fitting with expectations. This represents relatively quick equilibrations with a value near – 1 being an instantaneous return to normal, and a value near 0 being a fairly long-lasting effect.

The models in also include two important controls. The first is a seat share variable for each party at time t. In all six models, this control is positive and significant indicating that parties with more seats, generally increase their number of questions from quarter to quarter although the size of this effect is small. With the highest seat share at 63.58 per cent, the biggest effect increase would be approximately 3.2 questions (63.58% × 0.050). The results for the other control in the model, ‘Election’ at time t−1 is insignificant in all models.

Conclusion

The idea that political parties have preferred issues and are constantly striving to get their opponents to focus on them has long been studied by agenda-setting and issue competition scholars. On the other hand, it is surprising how little research has been conducted on the impact of problem indicators over issue competition dynamics. Parties do not shift their issue focus on a whim or talk about issues in the abstract but are constantly scanning the world looking for evidence of problems they could use to push their preferred issues in the political agenda. Or problems might force them to address an unwanted issue. Ultimately, ‘political attention to policy issues is always about something, and that something is policy “problems”’ (Green-Pedersen, Citation2019, p. 174).Footnote7 While seemingly an obvious statement, our study offers a comprehensive (in regard to the number of countries, political parties, and issues) empirical analysis about the extent to which political parties respond to problem information, as well as the impact of mediating factors such as their position in government or opposition and their ideological profile. Our second contribution is to shift the focus from electoral campaigns to the day-to-day parliamentary debates conducted through questions to the government, another important stage where parties engage in issue competition.

We find that parties indeed respond to problems across our large sample of comparative data. Yet, variation in responsiveness to problems is also a very important finding. Whereas a rise in unemployment is correlated with a substantial surge of attention for the issue in the party system agenda, the evidence is not as strong with immigration and was generally marginal in the terrorism response. These results suggest that unemployment comes closer to the idea of valence issue in which the majority of parties have an interest in showing some concern when indicators worsen. Terrorism can also be deemed a typical valence issue, but its occurrence is more occasional and normally stirs a lot of public attention (especially in the immediate aftermath of an attack). Attacks do seem to drive political attention as focusing events, but the size of those effects is relatively small (Birkland, Citation1997). Finally, the partisan nature of immigration makes it more likely to become the object of strategic calculations by party actors: only some will pick it up while others will prefer to ignore it. In our analyses, we use the inflow of immigrants to measure the problem, but this depends on a generally rightwing framing of immigration, namely that higher numbers are a problem. Overall, these findings reveal that the political interpretation of indicators is not always straightforward (Kingdon, Citation2011) and warrant further investigation into the impact of issue characteristics for political agenda-setting dynamics (Green-Pedersen, Citation2019).

Secondly, we tested to what extent the government position of parties and their ideology affects the way they attend to changes in problem indicators. As expected, we found opposition parties were more likely to respond to problem status than government parties. The test of the partisan left-right logic generally showed that parties further to the right responded more to our different problem measures. The exception was changes in immigration for left wing parties in government. While all these results support partisan differences in responsiveness, our expectations of how different problems would be responded to on the left and the right were not met. Overall, the findings lend support to the argument that government and opposition use different agenda-setting strategies, although some caution is warranted as these patterns may originate, in part, from our empirical focus on a parliamentary institution, questions to the government, which is traditionally an agenda-setting tool of opposition parties.

With that being said, future analyses should put into sharper focus at least three other related aspects. On the one hand, it is worth exploring the impact of problem indicators measured in neighbouring countries or at the level of regional organisations, such as in the European Union. This should hold particularly true for issues like climate change, whose political resonance is usually felt across national boundaries, affecting more than one country simultaneously (for international drivers of national agendas see, for instance, Green-Pedersen, Citation2020). On the other hand, other party attributes could be incorporated to better understand why certain party actors can simply ignore certain problem indicators while others are forced to deal with them. For instance, it is likely that the incentives of big mainstream parties to pick up an issue – which depend on domestic dynamics of party competition and coalition tactics – has a deep impact on the overall composition of the party system agenda. This work likely requires smaller scale analyses on single or smaller collections of countries due to data availability and the increasing complexity of party system agendas as they are investigated more closely. Finally, we need to start investigating variation in problems. We focus on very visible, widely recognised, constantly changing indicators and our study therefore cannot tell how/if parliaments respond to, e.g., more slow-moving problems such as mental health (Bernardi, Citation2021), more contested problem indicators such as measures of climate change, or less salient issues. Part of this should also be to investigate temporal dynamics since the responsiveness might depend on the distance to the next election.

With an increasing amount of data available at our fingertips, analysing the political impact of problem indicators and how they are strategically used by party actors to advance their agendas represent relevant avenues for future research. By relying on an extensive cross-country dataset, this study provides important insights that, conceivably, encourage a more systematic use of problem information in models of party competition.

Acknowledgment

We kindly thank the Comparative Agendas Project community for the support and open access data they provide for making this cross-national research effort possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 At the same time, research also reveals that such divergence occurs on top of a common base-line problem-responsiveness across all parties, regardless of their position in or out of government (see also Seeberg, Citation2017, Citation2020).

2 It is difficult to draw clear and static dividing lines between what belongs to the European and local level and what belongs to the national one. With that being said, national government authority is likely greater for terrorism than for immigration and economic policy that might also be affected also by policymaking at other levels of governance.

3 The use of yearly data leads to more conservative estimates for our change effects as there are no changes within each year. Despite this our analyses still show marginally significant effects for the opposition as later demonstrated in the analyses and through .

4 We chose the economic rather than general left/right measure as both immigration and unemployment are clearly and consistently tied to the economy. Terrorism could arguably relate to either dimension. We also ran our analyses using the general measure which led to the same inferences; however, this led to a declining although still insignificant effect for immigration in government moving to the political right.

5 Note: Due to the significant differences in scale between issue areas as well as level and change effects each figure is scaled separately to better indicate effect sizes.

6 Due to the interaction between problems (levels and changes) and left-right position that we specify in , the coefficients for problems are in many instances negative in . This does not mean that problems exert a negative effect on questions in general as these effects cannot be interpreted directly. Margins plots, which we report in –, make the interpretation of such interaction terms possible.

7 On a similar note, Kingdon states that: ‘While the emergence of a widespread feeling that a problem exists out there may not always be responsible for prompting attention to a subject, people in and around government still must be convinced somewhere along the line that they are addressing a real problem’ (Citation2011, p. 115).

References

- Abney, R., Adams, J., Clark, M., Easton, M., Ezrow, L., Kosmidis, S., & Neundorf, A. (2013). When does valence matter? Heightened valence effects for governing parties during election campaigns. Party Politics, 19(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810395057

- Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2017). Democracy for realists. In Democracy for realists. Princeton University Press.

- Bailer, S. (2011). People's voice or information pool? The role of, and reasons for, parliamentary questions in the Swiss parliament. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17(3), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2011.595123

- Baumgartner, F. R., Breunig, C., & Grossman, E. (2019). Comparative policy agendas: Theory, tools, data. Oxford University Press.

- Belchior, A. M., & Borghetto, E. (2019). The Portuguese policy agendas project. In Comparative policy agendas: Theory, tools, data (pp. 145–151). Oxford University Press.

- Bernardi, L. (2021). Mental health and political representation: A roadmap. Frontiers in Political Science, 2, 587588.

- Bevan, S. (2019). The creation of the comparative agendas project master codebook. In . Comparative policy agendas: Theory, tools, data (pp. 17–34). Oxford University Press.

- Bevan, S., Jennings, W., & Pickup, M. (2019). Problem detection in legislative oversight: An analysis of legislative committee agendas in the UK and US. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1560–1578. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1531910

- Birkland, T. A. (1997). After disaster: Agenda setting, public policy, and focusing events. Georgetown University Press.

- Bonafont, L. C., Baumgartner, F. R., & Palau, A. (2015). Agenda dynamics in Spain. Palgrave.

- Borghetto, E., & Chaqués-Bonafont, L. (2019). Parliamentary questions. Comparative policy agendas: Theory, tools, data. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 282-299.

- Borghetto, E., & Russo, F. (2018). From agenda setters to agenda takers? The determinants of party issue attention in times of crisis. Party Politics, 24(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817740757

- Budge, I., & Farlie, D. (1983). Party competition. Selective emphasis or direct confrontation? An alternative view with data. In H. Daalder, & P. Mair (Eds.), West European party systems. Continuity & change. Sage Publications.

- Bundi, P. (2018). Varieties of accountability: How attributes of policy fields shape parliamentary oversight. Governance, 31(1), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12282

- Busemeyer, M., Garritzmann, J., & Neimanns, E. (2020). A loud but noisy signal?: Public opinion and education reform in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Calca, P., & Gross, M. (2019). To adapt or to disregard? Parties’ reactions to external shocks. West European Politics, 42(3), 545–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1549851

- Carmines, E. G. (1991). The logic of party alignments. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 3(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692891003001005

- DeLeo, R. A., & Duarte, A. (2022). Does data drive policymaking? A multiple streams perspective on the relationship between indicators and agenda setting. Policy Studies Journal, 50(3), 701–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12419

- Dolezal, M., Ennser-Jedenastik, L., Müller, W. C., & Winkler, A. K. (2014). How parties compete for votes: A test of saliency theory. European Journal of Political Research, 53(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12017

- Döring, H., Huber, C., & Manow, P. (2022). Parliaments and governments database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in established democracies. Development Version. https://www.parlgov.org/about/

- Elsässer, L., Hense, S., & Schäfer, A. (2021). Not just money: Unequal responsiveness in egalitarian democracies. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(12), 1890–1908. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1801804

- Fiorina, M. (1981). Retrospective voting in American national elections. Yale University Press.

- Froio, C., Bevan, S., & Jennings, W. (2017). Party mandates and the politics of attention: Party platforms, public priorities and the policy agenda in Britain. Party Politics, 23(6), 692–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815625228

- Garritzmann, J. L. (2017). How much power do oppositions have? Comparing the opportunity structures of parliamentary oppositions in 21 democracies. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 23(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2017.1283913

- Gilens, M. (2005). Inequality and democratic responsiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69(5), 778–796. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfi058

- Grande, E., Schwarzbözl, T., & Fatke, M. (2019). Politicizing immigration in Western Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1444–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1531909

- Green-Pedersen, C. (2007). The growing importance of issue competition: The changing nature of party competition in Western Europe. Political Studies, 55(3), 607–628.

- Green-Pedersen, C. (2019). The reshaping of West European party politics: Agenda-setting and party competition in comparative perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Green-Pedersen, C. (2020). Issue competition in a globalized world: The causes of cross-national similarities and differences in the issue content of party politics. In Globalizing issues: How claims, frames, and problems cross borders (pp. 73–94.

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Krogstrup, J. (2008). Immigration as a political issue in Denmark and Sweden. European Journal of Political Research, 47(5), 610–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00777.x

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Mortensen, P. B. (2010). Who sets the agenda and who responds to it in the Danish parliament? A new model of issue competition and agenda-setting. European Journal of Political Research, 49(2), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01897.x

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Mortensen, P. (2014). The dynamics of issue competition: Avoidance and engagement. Political Studies, 63(4), 747–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12121

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Otjes, S. (2019). A hot topic? Immigration on the agenda in Western Europe. Party Politics, 25(3), 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817728211

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Wolfe, M. (2009). The institutionalization of environmental attention in the United States and Denmark: Multiple-versus single-venue systems. Governance, 22(4), 625–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01456.x

- Green, J. (2007). When voters and parties agree: Valence issues and party competition. Political Studies, 55(3), 629–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00671.x

- Green, J., & Jennings, W. (2012). The dynamics of issue competence and vote for parties in and out of power: An analysis of valence in Britain, 1979–1997. European Journal of Political Research, 51(4), 469–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02004.x

- Greene, Z. (2016). Competing on the issues: How experience in government and economic conditions influence the scope of parties’ policy messages. Party Politics, 22(6), 809–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068814567026

- Healy, A. J., Malhotra, N., & Mo, C. H. (2010). Irrelevant events affect voters’ evaluations of government performance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(29), 12804–12809. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1007420107

- Heclo, H. (1974). Modern social politics in Britain and Sweden. ECPR Press.

- Hibbs, D. A. (1977). Political parties and macroeconomic policy. American Political Science Review, 71(4), 1467–1487. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961490

- Höhmann, D., & Sieberer, U. (2020). Parliamentary questions as a control mechanism in coalition governments. West European Politics, 43(1), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1611986

- Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2005). The politics of attention: How government prioritizes problems. University of Chicago Press.

- Kelley, J. G., & Simmons, B. A. (2015). Politics by number: Indicators as social pressure in international relations. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12119

- Key, V. (1966). The responsible electorate: Rationality in presidential voting, 1936–1960. Harvard University Press.

- Kingdon, J. W. (2011). Agendas, alternatives and public policies (2nd ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Kristensen, T. (2020). The politics of numbers: How problem indicators and party competition influence political attention [Doctoral dissertation]. Politica.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Paldam, M. (2000). Economic voting: An introduction. Electoral Studies, 19(2-3), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(99)00042-6

- Louwerse, T., & Otjes, S. (2019). How populists wage opposition: Parliamentary opposition behaviour and populism in Netherlands. Political Studies, 67(2), 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321718774717

- Mansbridge, J. (2003). Rethinking representation. American Political Science Review, 97(4), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000856

- Marsh, M., & Tilley, J. (2010). The attribution of credit and blame to governments and its impact on vote choice. British Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409990275

- Martin, S. (2011). Parliamentary questions, the behaviour of legislators, and the function of legislatures: An introduction. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17(3), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2011.595120

- Martin, S., & Whitaker, R. (2019). Beyond committees: Parliamentary oversight of coalition government in Britain. West European Politics, 42(7), 1464–1486. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1593595

- Mortensen, P. B., Green-Pedersen, C., Breeman, G., Chaqués-Bonafont, L., Jennings, W., John, P., Timmermans, A., et al. (2011). Comparing government agendas: Executive speeches in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and Denmark. Comparative Political Studies, 44(8), 973–1000. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011405162

- Otjes, S., & Louwerse, T. (2018). Parliamentary questions as strategic party tools. West European Politics, 41(2), 496–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1358936

- Pennings, P. (1998). Party responsiveness and socio-economic problem-solving in western democracies. Party Politics, 4(3), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068898004003007

- Petrocik, J. (1996). Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. American Journal of Political Science, 40(3), 825–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111797

- Pitkin, H. (1967). The concept of representation. University of California Press.

- Rochefort, D., & Cobb, R. (1993). Problem definition, agenda access, and policy choice. Policy Studies Journal, 21(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.1993.tb01453.x

- Russo, F. (2011). The constituency as a focus of representation: Studying the Italian case through the analysis of parliamentary questions. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17(3), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2011.595122

- Russo, F., & Cavalieri, A. (2016). The policy content of the Italian question time. A new dataset to study party competition. Rivista Italiana di Politiche Pubbliche, 11(2), 197–222.

- Saalfeld, T. (2011). Parliamentary questions as instruments of substantive representation: Visible minorities in the UK House of commons, 2005–10. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17(3), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2011.595121

- Sagarzazu, I., & Klüver, H. (2017). Coalition governments and party competition: Political communication strategies of coalition parties. Political Science Research and Methods, 5(2), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2015.56

- Seeberg, H. (2013). Parties and policies on the opposition’s influence on policy through issue politicization. Journal of Public Policy, 33(1), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X12000190

- Seeberg, H. (2017). How stable is political parties’ issue ownership? A cross-time, cross-national analysis. Political Studies, 65(2), 475–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716650224

- Seeberg, H. (2020). The impact of opposition criticism on the public’s evaluation of government competence. Party Politics, 26(4), 484–495.

- Seeberg, H. (2022). First avoidance, then engagement: Political parties’ issue competition in the electoral cycle. Party Politics, 28(2), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820970353

- Serban, R. (2022). How are prime ministers held to account? Exploring procedures and practices in 31 parliamentary democracies. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 28(2), 155–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2020.1853944

- Spoon, J. J., Hobolt, S. B., & De Vries, C. E. (2014). Going green: Explaining issue competition on the environment. European Journal of Political Research, 53(2), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12032

- Stokes, D. (1963). Spatial models of party competition. American Political Science Review, 57(2), 368–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952828

- Stone, D. (2002). Policy paradox. The art of political decision making. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Strom, K. (1990). A behavioral theory of competitive political parties. American Journal of Political Science, 34(2), 565–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111461

- Tavits, M., & Potter, J. D. (2015). The effect of inequality and social identity on party strategies. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 744–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12144

- Thesen, G. (2013). When good news is scarce and bad news is good: Government responsibilities and opposition possibilities in political agenda-setting. European Journal of Political Research, 52(3), 364–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02075.x

- Thomassen, J. (2005). The European voter: A comparative study of modern democracies. Oxford University Press.

- Traber, D., Schoonvelde, M., & Schumacher, G. (2020). Errors have been made, others will be blamed: Issue engagement and blame shifting in prime minister speeches during the economic crisis in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 59(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12340

- Vliegenthart, R., & Walgrave, S. (2011). Content matters: The dynamics of parliamentary questioning in Belgium and Denmark. Comparative Political Studies, 44(8), 1031–1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011405168

- Vliegenthart, R., Walgrave, S., Baumgartner, F. R., Bevan, S., Breunig, C., Brouard, S., Tresch, A., et al. (2016). Do the media set the parliamentary agenda? A comparative study in seven countries. European Journal of Political Research, 55(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12134

- Volkens, A., et al. (2014). The manifesto data collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR).

- Wlezien, C. (1995). The public as thermostat: Dynamics of preferences for spending. American Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111666

- Wouters, R., Sevenans, J., & Vliegenthart, R. (2021). Selective deafness of political parties: Strategic responsiveness to media, protest and real-world signals on immigration in Belgian Parliament. Parliamentary Affairs, 74(1), 27–51.

- Zittel, T., Nyhuis, D., & Baumann, M. (2019). Geographic representation in party-dominated legislatures: A quantitative text analysis of parliamentary questions in the German Bundestag. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 44(4), 681–711. doi:10.1111/lsq.12238