ABSTRACT

This article examines gender equality policy in Britain, pre-and post-Brexit. Through a gendered analysis of European Union (EU) directives over forty years, we examine which policies have been key to Britain’s gender equality agenda. We find that the EU’s gender equality framework has been particularly integral to the advancement of ‘class-based’ policies, which seek to ameliorate inequalities that arise from the sexual division of labour. Taken together, we argue that the impact of Brexit risks directly rolling back these class-based gains. This is as a result of a shift away from a more consensual style of policymaking at the supranational level, towards a top-down, adversarial and masculinised Westminster Model, which marginalises women from decision-making fora. As it stands, advancements in gender equality policies are unlikely to be regained in the current political climate due to the absence of the stimulus of the EU for domestic gender equality reform.

Introduction

The outcome of Britain’s 2016 referendum and resulting departure from the European Union marked significant concerns among gender equality activists on the future of gender equality. Sam Smethers, then CEO of the Fawcett Society, warned that Brexit risked ‘turning the clock back on gender equality’ (The Fawcett Society, Citation2018). Elsewhere, Mary-Ann Stephenson, Director of the Women’s Budget Group (WBG), noted that ‘the overall impact of Brexit is likely to be negative … This will affect women as users of public services, as workers and consumers’ (Stephenson, Citation2018). The run-up to the referendum saw a campaign that was dominated by men, with women scarcely visible in either the Remain and Leave campaigns. Indeed, analysis conducted during the referendum campaign showed that women comprised 16% of those featured in TV coverage and just 9% of those featured in press coverage of the campaign (Deacon et al., Citation2016a). This lack of coverage partly reflected the male-dominated nature of the formal political sphere. At the time of the campaign, the three ‘mainstream’ political parties – the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats – were led by men, with women leaders representing either nationalist parties (the SNP and Plaid Cymru), or smaller parties (the Green Party). The marginalisation of women’s voices from the EU referendum campaign prompted Labour MP Harriet Harman to write a letter to the UK’s communications regulator, Ofcom, to ensure greater gender balance in EU referendum coverage. While the intervention precipitated a small increase in women’s coverage (much of which related to Harman’s letter itself), campaign coverage still failed to reach gender parity (Deacon et al., Citation2016b). More widely, the campaign reflected a lack of inclusivity in the public sphere, whereby women faced marginalisation and, in some instances, misogyny, when publicly speaking out on issues relating to EU membership (Galpin, Citation2018). More recent evidence from the 2019 General Election, for instance, showed that women Parliamentary candidates were more likely than their male counterparts to experience harassment from Brexit supporters (64% of women compared to 42% of men) (Collignon & Rudig, Citation2021).

While women’s visibility was low, much scarcer from the campaign were discussions of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union and the impact that this would have on gender equality in the future. Issues of ‘high politics’, such as the economy, immigration and security, received the highest amount of coverage from both the Leave and Remain campaigns (Haastrup et al., Citation2016). Featured much less were discussions of social policies and gender equality policies – often considered to be issues of ‘low politics’& nbsp;(Haastrup et al., Citation2016) – illustrating a widely-held belief among political actors that such issues are of low salience.Footnote1

Given this lack of coverage devoted to women’s rights and interests during the campaign, there is a need to explore the direction of gender equality policy in a post-Brexit policymaking context. Therefore, this article seeks to answer two questions. Firstly, what role has the European Union played in getting gender equality policies onto the British executive’s policy agenda? Secondly, what risk does Brexit pose to the advancements gained from these gender equality policies?

The article is structured as followed. Firstly, we examine a body of existing literature on gender equality and agenda setting. We then move on to discuss the materials and methods used in the article, and introduce Htun and Weldon’s (Citation2018) gender equality policy framework. Subsequently, we take forward Htun and Weldon’s research and examine EU Directives against this framework, exploring what type of gender equality in Britain has been advanced by the EU. Finally, we consider these findings going forward, asking what these findings mean for gender equality in Britain in light of its departure from the EU.

Getting gender equality onto the government’s policy agenda: from the national to the international level

Historically, gender equality advocates in Britain have struggled to achieve policy change at the national level (Annesley, Citation2010; Annesley & Gains, Citation2013; Himmelweit, Citation2005). Underpinning this policymaking landscape within Westminster is a closed, centralised, and adversarial system of governing – a framework otherwise known as the Westminster Model (Lijphart, Citation1999). This ‘power hoarding’ model is masculinised by its very nature. The ‘blokey and laddish’ (Annesley & Gains, Citation2010, p. 919) culture reinforced by the Westminster Model excludes women from decision-making fora, which marginalises women’s interests and voices. As Mackay (Citation2014, p. 559) notes, ‘Westminster remains an exclusionary, masculine-gendered, white, and heteronormative institutions, where women and ethnic minority newcomers are treated as “Space Invaders”.’

While gender equality advocates have struggled to advance women’s interests at the national level, existing literature points to a number of ‘window of opportunities’ where policy change can occur. A body of work has highlighted the importance of representation in drawing executive attention to gender equality policies, notably through having women representatives as advocates for gender equality (Childs & Krook, Citation2006; Childs & Withey, Citation2006; Mansbridge, Citation1999). Underpinning this argument is the assumption that there is a link between an increase in the number of women representatives (descriptive representation), and the adoption of gender equality policies, or policies that are women-friendly (substantive representation). Women representatives can form ‘advocacy coalitions’ (Sabatier, Citation1988) to strategically place items onto the executive’s agenda. In advocating for gender equality, representatives act as ‘critical actors’, who ‘initiate policy proposals on their own, even when women form a small minority, and embolden others to take steps to promote policies for women, regardless of the proportion of female representatives’ (Childs & Krook, Citation2006, p. 528).

The success of gender equality advocates to achieve change depends on power and influence. Annesley and Gains (Citation2010) argue that in Westminster-style democracies, critical feminist actors are more successful in achieving outcomes if they are placed in the core executive. By holding ministerial positions and being positioned in the site of policy-making, they are more likely to have access to resources and wield influence over outcomes. For example, Labour MP Harriet Harman noted that before being appointed Solicitor General in 2001, campaigners against domestic violence ‘never had anyone in government to bring it all together and single-mindedly take forward their cause. But now I’d been appointed and was there on the inside, I could make changes throughout the system, support victims, deter perpetrators and challenge embedded attitudes’ (Harman, Citation2017, p. 232). Such instances of policy change are rare in part because women are often excluded from core executive. As Annesley and Gains (Citation2010) note, ‘the UK core executive has a gendered disposition in relation to its recruitment, roles, access to resources, membership of networks and tactics used by core executive actors’ (p. 921).

Elsewhere, existing research has pointed to the role of party ideology, finding that social democratic governments can open up a window of opportunity to substantively represent women’s interests in government (Annesley & Gains, Citation2013; Htun & Weldon, Citation2018), with centre-right parties less likely to do so. However, even in the New Labour years, gender equality organisations were only able to ‘alter the efficiency of existing policies – rather than intervene in policy decisions if the cost of doing so was high’ (Annesley, Citation2010, p. 22). For many critical feminist actors, therefore, Westminster has been a difficult institution to navigate to achieve policy change.

As EU competences increased from the 1980s and 1990s, gender equality advocates started to look beyond the national level and instead towards the European Union to push for policy change (Mazey & Richardson, Citation2015). As power transferred away from the British state and upwards to the EU, this led to a proliferation of interest groups (Mahoney & Baumgartner, Citation2008). The expansion of EU competences led to an increase in lobbying activity from women’s rights groups, but also across other policy areas, such as the environment and animal rights (Mazey & Richardson, Citation2015). Women’s interest groups were able to move between different EU institutions in a process of ‘venue shopping’ (Baumgartner & Jones, Citation1993).

For many women’s rights advocates, the EU appeared to be a promising venue for policy change: as Fagan and Rubery (Citation2018) note, Britain introduced its laws on equal pay and sex discrimination only as a result of being offered EU membership and to align with EU legislation. The European Union’s commitment to gender equality is rooted in Article 119 of the 1957 Treaty of Rome. The Treaty incorporates the principle of equal pay for men and women for equal work. This commitment was one that was based on equality feminism: in other words, ensuring women receive the same treatment as men. Yet it was not until the 1980s that the EU began to adopt an approach towards gender equality that acknowledged differences between men and women, seen through positive action policies (Fiig, Citation2020). This was followed by a new strategy to advance gender equality based on gender mainstreaming. 1999 witnessed the Treaty of Amsterdam enter into force, which aimed to ‘promote equality between women and men in all … activities and policies at all levels’ (Commission of the European Communities, Citation1996). The approach sought to extend the scope of gender equality policy beyond employment, to which gender equality had previously been confined. In essence, it aimed to shift the framing of gender as a ‘niche’ policy issue and, instead, frame gender in a way that cuts across all policy issues. While some have been critical about the application of the EU’s gender mainstreaming approach (Nott, Citation1999; Stratigaki, Citation2005), others have been more optimistic, pointing to gender mainstreaming as having the ability to transform the policy process and eliminate gender biases (Squires, Citation2005).

As Mazey (Citation1995; Citation2012) has noted, much of this progress within the EU been attributed to women’s organisations and feminist networks, which have played a crucial role within the agenda-setting process. Women’s interest groups have long pursued a strategy of influencing negotiations through ‘insider strategies’ of formally organising and seeking to influence directly the agendas of multilateral institutions through strategies such as lobbying, providing policy-makers with information, developing media campaign, or even writing legislation (see Meyer & Prügl, Citation1999; Spalter-Roth, Citation1995). For example, women’s NGOs and feminist advocates actively work as insiders through the United Nations (UN) through the Women’s Major Group to great success (Higer, Citation1999). In the UN climate negotiations, for example, women’s NGOs have been a crucial player in ensuring women’s concerned are included in global climate policy resulting in a Gender Action Plan being adopted in 2017 to consolidate and implement the fast-growing number of gender decisions adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Flavell, Citation2023). At the EU level, women’s interest groups have had a ‘symbiotic relationship’ with the European Commission (EC) (Mazey & Richardson, Citation2006, p. 280). This relationship has allowed women’s interest groups to achieve policy success, particularly through the EC. This is due, in part, to the ‘open nature of the EC’s decision-making process’, which has provided women’s interest groups with ‘multiple access points’ (Mazey, Citation1998, p. 138). This has enabled women’s interest groups to ‘get a foot in the door’ and achieve policy change by exerting their influence. For example, women’s groups and women’s MEPs have been effective at placing women’s rights on the EC’s policy agenda (Mazey, Citation1998.). This insider approach has allowed the women’s movement to become a highly visible player at the policy table (Higer, Citation1999). At the same time, the EC has relied on women’s interest groups for ‘information, support and legitimacy’ (Mazey & Richardson, Citation2015, p. 423). Elsewhere, women’s interest groups have had success at achieving policy change in the European Court of Justice (ECJ), particularly around securing working women’s rights and effecting national change (Mazey, Citation1998; Citation2012).

The impetus of the EU as a driver for gender equality policies emphasises a need to examine the policy landscape post-Brexit. While a body of work has examined the impact of Brexit on gender equality in Britain (Fagan & Rubery, Citation2018; Guerrina & Masselot, Citation2018; MacLeavy, Citation2018), existing research has, to date, predominantly given less attention to the type of gender equality issues at risk. We argue that in order to understand and fully assess the progress made towards gender equality – and the risks to these advancements – an assessment of gender equality is needed that considers the type of gender equality being proposed: namely, whether these are based on class-based equalities, or whether they are based on equality affecting women as a group. The next section of this article introduces the theoretical framework and outlines the methods used.

Materials and methods

This article examines British gender equality policies that have stemmed from the EU using Htun and Weldon’s (Citation2010; Citation2018) gender equality policy framework. Developing a framework to analyse the adoption of gender equality policy by governments, Htun and Weldon disaggregate gender equality policy into two types. The first type of policy that Htun and Weldon identify is ‘gender status’ policies (hereinafter ‘status’ policies). These are policies which address injustices that women face as women. In other words, they seek to ameliorate harms that affect all women face on the basis of their gender. Examples of status policies might therefore include issues based on women’s bodily integrity, such as abortion legality, violence against women, or policies based on enhancing women’s descriptive representation in politics, such as quotas for women in political decision-making roles.

The second type of policy that Htun and Weldon (Citation2010; Citation2018) identify is class-based policies. These are policies which seek to address inequalities that stem from the sexual division of labour, such as those based on state-funded childcare or pensions. In so doing, class-based policies seek to shift women out of the unpaid private sphere and into the paid labour market instead. In Britain, women’s employment rate currently stands at 72.2% (Office for National Statistics, Citation2022a). While women’s employment rate has been steadily increasing over time, the average employment rate for women in Britain is 6.7 percentage points lower than that of men’s (Office for National Statistics, Citation2022b). Women in Britain also have, on average, lower incomes relative to men, making women disproportionately reliant on the state for welfare and services. Therefore, class-based policies such as those relating to childcare, social security, parental leave and pensions have the capacity to ameliorate these gendered inequalities.

There is a particular advantage in using Htun and Weldon’s framework when analysing gender equality policy. Women are not a monolithic bloc, and experience injustices to varying degrees along the lines of class, ethnicity, sexuality, disability and so on. Such injustices do not operate independently: rather, they intersect to create additional forms of discrimination (see Crenshaw, Citation1989). The framework acknowledges that gender equality policies affect women differently according to the injustices they face; namely, whether they affect women through their economic position in the labour market, or whether they affect all women by virtue of their gender. As such, the framework takes an intersectional approach, whilst acknowledging that different types of policies advance different types of gender equality. Thus, this article seeks to explore the different advancements made in gender equality according to whether they advance women’s status or women’s class.

To explore which EU directives have been key to Britain’s gender equality agenda, we examine UK government legislation, specifically directives that have originated from the EU. Directives are legal acts that set out objectives for member states to achieve. While directives are legally binding, there is some discretion for member states as to how they implement the objectives. Using directives as a proxy for attention to gender equality enables us to identify which types of issues receive policy attention. In order to explore which of these directives relate to gender equality, ‘women’, ‘gender’ and ‘sex’ were used as key search terms. This allowed us to examine directives that specifically acknowledge women and directives that identify issues as being explicitly gendered. Similar approaches have been adopted elsewhere, such as Sanders et al. (Citation2021) gendered analysis of British party manifestos. Directives were then coded manually into those which seek to address women’s class-based inequality, and those which address the status of women as a group. Not all directives mentioning women and gender were included in the analysis, as not all spoke to the theme of gender equality. For instance, the 2010/63/EU directive on the protection of animals for scientific purposes mentions gender in relation to animals. At the same time, gender is mentioned in the 2015/413 directive on facilitating the exchange of information on road-safety-related traffic offences, but only in relation to how data should be gathered. Therefore, the authors’ judgment was used, and these items were discarded from the analysis.

There are limitations to this approach because it captures only directives that explicitly mention women and gender. Indeed, women may still be beneficiaries of policies that do not mention these terms. For example, the 93/104/EC Working Time Directive set limits to weekly working hours and night shifts, and set in place provisions for weekly rest periods and paid annual leave. Such measures benefit women in particular, because flexible working makes the labour market more accessible to those who have traditionally faced barriers. However, the measures are not framed via a gendered lens – in other words, they focus on ‘workers’ more widely. Similarly, the 2013/48/EU directive calls for the right to legal aid. Provision of legal aid benefits women especially, since they are more reliant than men on legal aid as a result of their lower average incomes (Women’s Budget Group, Citation2017). We now turn to an analysis of EU gender equality directives to examine how this has influenced Britain’s gender equality agenda.

Results

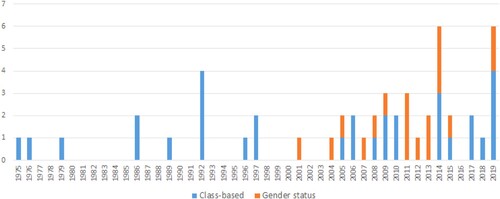

The results are displayed in , which shows the number of EU directives relating to gender equality between 1975 and 2019. The full list of policies is available in the Supplemental Material. The results show that there are few gender equality directives between 1975 and 2003. 1992 is an outlier, with four class-based directives issues in this year. The number of gender equality directives increases substantially after 2004. The growth of gender equality directives after this year may reflect the move towards gender mainstreaming from 1995, with a possibly lagged effect. 2014 and 2019 are particularly striking in terms of the number of directives introduced, with six directives in each year respectively. It is particularly interesting that many directives after this time also address women’s status as well as class-based differences. Taken together, the results show that EU gender equality directives have increased in their scale, frequency and diversity.

Figure 1 . Directives 1975–2019, according to Htun and Weldon’s (Citation2018) gender equality policy typology.

shows that, historically, directives have been based on addressing economic concerns. Of the class-based directives introduced earlier, two seek to strengthen women’s rights in relation to statutory social security. The 1978 directive on social security (79/7/EEC) removed the ban on married women, and cohabiting women, from being able to claim social security benefits. This was followed by the 1986 directive on equal treatment for men and women in occupational social security schemes. Measures to strengthen rights for pregnant women in the workplace also emerge as a clear theme in terms of where class-based directives have been issued, especially when examining directives that have been issued in earlier years. All four class-based directives in 1992 seek to strengthen women’s rights in the workplace via a series of health and safety measures. A notable example is the introduction of the Pregnant Workers Directive in 1992 (92/85/EEC), which prevents the dismissal of a pregnant worker between pregnancy and the end of maternity leave. Strengthened rights for pregnant women in the workplace continue beyond 1992. For instance, under the 1996 Posted Workers Directive (96/71/EC), employers wishing to transfer their workers to other EU member states would be required to ensure that ‘protective measures’ are in place for pregnant women and new mothers.

A closer analysis of class-based directives shows instances where UK governments have sought to block progressive legislation, and have ‘watered down’ initiatives accordingly. A notable example can be seen in 1992. The European Commission initially drafted an ‘ambitious’ version of the 1992 Pregnant Workers Directive (Guerrina & Masselot, Citation2018, p. 323). Yet the proposals within this directive were later watered down due to Britain’s opposition on the grounds that it would be too costly for employers, and as a result, pregnancy and maternity rights represented a minimum safety net (Guerrina & Masselot, Citation2018.). Similarly, the UK government sought to block the adoption of the 1996 Parental Leave Directive, which set minimum standards on parental leave. These findings resonate with wider examples, such as the 2003 Working Time Directive. While employees gained paid annual leave under this directive, the UK secured an ‘opt out’ from the provision that sets limits on a 48 working hour week, leaving it to individuals to negotiate this with their employers (Fagan & Rubery, Citation2018). In essence, these examples suggest that while the EU has been influential in pushing class-based directives forward, they have been ‘watered down’ by UK governments and met with some reluctance.

shows that a range of status directives are implemented after 2004. Many of these status directives relate to women’s bodily integrity, such as human trafficking and the protecting of fertility in marketised products. For example, directive 2004/81/EC on resident permits for victims of human trafficking to third-country nationals. The directive also acknowledges human trafficking as a gendered issue, and identifies that men and women are trafficked for different purposes. This emphasis on gender is further strengthened in the 2011 Anti-Trafficking Directive (2011/36/EU), which highlights that support and assistance for victims of trafficking should be gender-specific where possible. There are also measures to protect women’s health: directive 2014/27/EU on the classification, labelling and packaging of substances sets out protections to ensure that substances do not endanger women’s fertility or the health of pregnant women. Having identified the specific directives that were introduced around gender equality between 1975 and 2019, the next section of this article now considers what this means for gender equality going forward, in light of Britain’s departure from the EU.

A shift towards a masculinised Westminster model

The results show that the EU has played an integral role in putting forward class-based directives. Many of these directives have related to employment rights, such as strengthening employment rights for part-time workers as well as those employed in temporary work, the majority of whom are women. Other directives have also related to tackling discrimination in employment, such as setting out principles for equal treatment in the workplace, and shifting the burden of proof in sex discrimination cases. Additionally, directives have consisted of strengthening and enhancing parental leave. Other initiatives have also focused on tackling discrimination in the workplace more widely – notably, shifting the burden of proof in sex discrimination cases in 1997. In particular, a range of directives were introduced that protect the rights of pregnant women. In terms of class-based initiatives, these have largely been focused on strengthening maternity rights in the workplace, such as health and safety measures, extending maternity leave, as well as adjustments in working conditions and hours. Regarding status directives, initiatives have also focused on protecting women’s fertility via tighter regulations on marketised products. The results also show a spread and scale in the type of gender equality proposed, where the EU has, in recent years, advanced more directives pertaining to women’s status. These have included directives on women’s body integrity, such as human trafficking and the protection of fertility in marketised products. In essence, these directives protect and advance the rights of all women as a group, by virtue of their gender.

Yet the impact of Brexit risks directly rolling back these gains. Arguably, this has already taken place through a shift away from a more consensual style of policymaking at the supranational level that has channelled women’s interests, towards a top-down, adversarial Westminster Model, which is masculinised in nature and marginalises women from decision-making fora. As Mackay (Citation2014) explains, ‘the Westminster parliamentary model … can be presented as one of “hegemonic political masculinity” … [c]rudely speaking, power, sovereignty and authority are all gendered masculine at the symbolic level as well as, as a rule, at the level of presence’ (p. 559). Whereas the British state was once, at least to some degree, ‘hollowed out’ via a transfer of power upwards to the EU (Rhodes, Citation1995), the result of Brexit has seen a repatriation of powers to Westminster that has only served to strengthen it further. Brexit has worked to reinforce a pre-existing ‘impositional’ and ‘hierarchical’ style of policymaking associated with the Westminster Model – under which ‘strong government’ prevails (Richardson, Citation2018, p. 215). This is perhaps seen most clearly in the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. The Act outlines powers transferred to Ministers to amend, repeal or modify EU legislation converted into domestic law, often at the expense of parliamentary scrutiny. The loss of EU influence has opened up a ‘vacuum’ for policy entrepreneurs to push forward gender equality policies at the national level. We argue that national actors have struggled to fill this vacuum. Rather, this shift from ‘governance’ to ‘government’ has undermined the influence of actors who were once able to exert influence to advance women’s interests: namely, women’s interest groups and sub-national governments. Moreover, we argue that the progression of gender equality policy is further hindered by two contextual factors: a male-dominated, centre-right government and a stifled economy. In particular, these factors prevent class-based policies from being placed on the national policy agenda.

A limited role of interest groups

The shift from ‘governance’ to ‘government’ that has occurred with the loss of the EU as a supranational actor in Britain has profound implications for the role of women’s interest groups and feminist organisations. As noted above, the influence of these groups has been significantly undermined by the effects of Brexit in Westminster politics. Our analysis suggests that there are two important implications for women’s interest groups in Britain in the wake of Brexit. First, women’s and feminist organisations have struggled to gain access to the policy-making sphere and exert influence over the progression of gender equality policies. The second implication is that under a male-dominated, centre-right government where masculinised norms prevail, pursuing a feminist agenda has become increasingly difficult. Here, we discuss these implications demonstrating their effect through the example of trade negotiations.

Since Brexit, there has been evidence of interest groups losing access to the policy process (Richardson & Rittberger, Citation2020). Women’s interest groups have been no exception to this. This was reflected in the House of Commons Procedure Committee review, which recommended that Members of Parliament should not be allowed to bring their baby into Parliament. The outcome of the review came under criticism, due to the fact that the Committee had not consulted with anybody outside of Parliament – despite being encouraged to do so (Allegretti, Citation2022). This poses a real concern for the advancement of gender concerns in Britain since, as Hemmati and Röhr (Citation2009) highlight, ‘if women’s organisations are not actively involved, gender and women’s aspects will not be addressed’ (p. 6). In other words, getting the word on the page requires a seat at the table. Losing a feminist presence in policy-making spaces is particularly concerning in the case of Brexit given the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 transferring powers to amend, repeal or modify EU legislation into domestic law, including those relating to human rights, to Ministers without parliamentary scrutiny. Many have pointed out the potential watering down, or even complete loss, of key human rights policies as part of this process. Human rights policies are always of great concern for feminist actors since, as Keck and Sikkink (Citation1998) argue, ‘governments are the primary “guarantors” of rights, but also their primary violators’ (p. 12). When a government violates, or refuses to recognise rights, advocacy groups often have no recourse within domestic or judicial arenas. As a result, these advocacy groups often seek out international connections to help strengthen their positions. Keck and Sikkink refer to this as a ‘boomerang pattern; of influence whereby domestic NGOs bypass their state and directly search out international allies to bring pressure on their states from the outside. Britain’s departure from the EU, therefore, represents the loss of such transnational alliances for women’s networks at a time when basic human rights, including women’s rights, are in jeopardy.

One clear area where the issue of a lesser role for women’s advocacy groups and a masculinised Westminster converge is in Brexit trade negotiations, which took place behind closed doors (Richardson & Rittberger, Citation2020). Commenting during the process of the government’s trade negotiations, CEO of the WBG, Mary Ann Stephenson, noted that ‘the prospects for a meaningful gender and broader equality analysis of proposed Brexit trade deals appear unlikely … women’s and girls’ rights remain marginalised and conditional on the business of Government’ (Stephenson & Fontana, Citation2019, pp. 431–432). It is telling that the government’s Article 50 negotiations revealed that just one of the nine negotiators was a woman (Catherine Webb, Director or Market Access and Budget) (MacLeavy, Citation2018). Hannah et al. (Citation2022) note that only recently have gender clauses begun to appear in bilateral Free Trade Agreements which is the result of initiatives developed by Inter-government NGOs from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to tackle the gender-differential impacts on trade policy. The authors conclude that ‘while gender and trade initiatives tend to reproduce and further entrench the trade orthodoxy, there are openings that could lead towards a more transformative trade politics’ (Hannah et al., Citation2022, p. 1369). But, without a strong women’s lobby overseeing trade negotiations, there is little reason to believe such transformative trade policies will be realised.

Indeed, a report by the Women's Budget Group and the Fawcett Society (Citation2018) predicted that Brexit, especially a ‘hard’ Brexit, would have serious implications for women as workers, consumers and users of public services. The report predicted that if Britain’s economy were to shrink, job losses would occur, particularly in sectors highly dependent on trade with the EU that includes clothing and textiles - industries which are dominated by women workers. The report also notes that much of the current policy protecting equality - including gender equality - in the workplace either originated from or has been strengthened by EU law. These protections are ultimately at risk due to the European Union (Withdrawal Act) 2018. Ultimately, the WBG and the Fawcett Society point out that Brexit diverts political attention and increasing levels of public resources away from urgent social issues, such as the crisis in social care, housing and economic inequality - all of which disproportionately affect women.

Weak institutions

Executive power can be curbed through the devolution of power to sub-national governments, in which the state becomes ‘hollowed out’ from below (Rhodes, Citation1995). New Labour’s 1998 devolution settlement oversaw the creation of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly (now Parliament). Since their set up, the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Assembly have taken a diverging policy agenda to that of Westminster, based on a distinctive social democratic agenda that sits to the left of Westminster. Broadly speaking, both devolved governments have, traditionally, taken more ‘women-friendly’ approaches in their policymaking that can be viewed as aligning more closely to the European Union than Westminster. This is perhaps seen most clearly through gender mainstreaming. The Scottish Parliament has made a ‘sustained attempt’ to incorporate gender equality into its budgeting process through a process of ‘gender budgeting’ (O’Hagan, Citation2017, p. 17), which has been lacking in Westminster (Himmelweit, Citation2005). O’Hagan (Citation2017) argues that this approach of gender budgeting has led to key policy developments in Scotland, such as extending publicly available childcare and attempts to address gendered occupational segregation. Wales, too, has provided an ‘impressive and thoroughly mainstreamed commitment to public services provision’ (Hankvivsky et al., Citation2019, p. 156) through initiating strategies to address the gender pay gap, reducing violence against women, and monitoring diversity in public appointments. These measures have led Hankvivsky et al. (Citation2019) to argue that ‘the devolved states offer examples of innovative equality mainstreaming initiatives, having largely overtaken work in England in this regard’ (p. 144). Additionally, women’s descriptive levels of representation in the devolved institutions have been higher than that of Westminster: women comprise 45% of Members of the Scottish Parliament and 47% of Members of the Welsh Parliament (compared to 35% of Members of Parliament in Westminster). It is also notable that the creation of the Scottish Parliament was designed to move away from the traditional ‘winner takes all’, adversarial Westminster Model of government; the Parliament’s horseshoe chamber was intended to design the institution based on a consociational model encouraging cross-party agreement (Brown, Citation2000).

Under the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, the Brexit process has seen Westminster repeatedly flex its constitutional muscles to bypass sub-national governments. The 2018 European Union Withdrawal Bill saw disputes between Westminster and devolved governments over the question of whether EU competences should be repatriated to the national or sub-national level. In what the devolved governments deemed to be a ‘naked power grab’ (as cited in Baldini et al., Citation2022, p. 349) by Westminster, the Scottish Parliament refused to grant consent to the Bill. Despite the Scottish Parliament’s opposition, this was overridden by Westminster and the Withdrawal Act was passed. Yet it was the issue of transgender rights – a gender status policy – which has seen Westminster’s supremacy continue after Brexit. The Gender Recognition Bill, introduced by the Scottish Parliament in March 2022, would see Scotland as the first part of the UK to allow self-identification rights to those wishing to change their gender. As the Bill passed through Holyrood, Westminster intervened by issuing a ‘Section 35’ – a provision within the Scotland Act 1998 – enabling it to effectively block the Bill from receiving royal assent. The intervention marked the first ever use of a Section 35 from Westminster since the creation of the Scottish Parliament. While sub-national governments have appeared to offer a more women-friendly policy agenda, the increasing compulsion of Westminster to assert its power over and above devolved governments risks stifling the advancements of these women-friendly policy agendas at the devolved level.

The 'hollowing out' of the British state can also occur by ceding power away from the executive through the judicial system. As such, women’s rights risk being rolled back through a reduced role of international and national courts on UK equality law. As noted earlier in this article, the ECJ has played an integral role in protecting women’s rights (Mazey, Citation2012). Whereas the ECJ was once able to interpret EC law, which had precedence over UK law, the passing of the 2018 EU Withdrawal Act has meant that the supremacy of EU law over UK law no longer applies. Moreover, Britain’s withdrawal from the EU has meant that national courts can no longer refer matters to the ECJ. The government’s response to its consultation on EU case law notes that the UK Supreme Court will treat EU case law decisions as ‘normally binding, [but] depart from a previous decision when it appears right to do so’ (Ministry of Justice, Citation2020, p. 76). As such, there is uncertainty around which aspects of women’s rights will remain. Our findings reveal that the rights that women stand to lose will predominantly be class-based, covering maternity and employment rights. We also show that some status rights are at risk, such as those focusing on fertility and harassment. Moreover, other aspects of EU law that are not protected by primary legislation are also at risk. For example, these include rights on pay and leave for part-time workers in Britain, 72% of whom are women (Taylor et al., Citation2023). Additionally, these include rights for agency workers (provided through the Agency Workers Regulations 2010) and fixed-term contracts (provided through the 2002 Fixed-Term Employees Regulations). Again, women form the majority of those concentrated within fixed-term contracts (56%) and agency work (Taylor et al., Citation2023.). In particular, ethnic minority women are disproportionately likely to be concentrated in forms of insecure work, posing a double-jeopardy for these groups of women (Women’s Budget Group, Citation2017). The 2018 Withdrawal Act also poses a further risk to the future of women’s rights, given that the EU Fundamental Charter on Human Rights is no longer part of UK law. Drawing on multiple international agreements, such as the ECHR, the ECJ and EU Directives, the EU Charter provides provisions for equality that directly relate to women’s rights. These provisions include a right to non-discrimination (Article 21) and ‘equality between men and women’ (Article 23).

Whether national courts will protect women’s rights remains uncertain. This will, in part, depend on the ability of interest groups, who often use courts as a venue to seek change (Richardson, Citation2006), to successfully exert influence. Yet pushing for policy change at the national level has been difficult, where women’s interest groups have faced challenges. One example comprises the campaign against the government’s Self-Employed Income Support Scheme (SEISS), which was designed to provide financial support to salaried self-employees affected by the pandemic. Under the SEISS, self-employed workers would receive payments from the Treasury, calculated on the basis of their average profits between 2016 and 2019. However, in practice, the policy was ‘gender-blind’: the payment calculations did not consider employees who had taken maternity leave, resulting in approximately 75,000 women losing payment (Topping, Citation2021). This ‘gender-blindness’ saw women’s rights groups arguing that the policy was in breach of anti-discrimination provisions of the 1998 Human Rights Act and the 2010 Equality Act (Topping, Citation2021). Maternity rights group, Pregnant Then Screwed, challenged the government in court – initially unsuccessfully – on the basis that the policy indirectly discriminated against self-employed mothers. Following judicial review, the Court of Appeal ruled that the government’s SEISS did directly discriminate against new mothers. Yet it was only through sustained campaigning that the group was able to push for change. Elsewhere, women’s interest groups have been less successful. In 2010, the Fawcett Society – a leading UK charity on gender equality – campaigned against government austerity measures outlined within its 2010 Emergency Budget, which fell disproportionately on women (Annesley, Citation2010). Following the government’s failure to produce an Equalities Impact Assessment of the Budget, the Fawcett Society sought judicial review, albeit unsuccessfully, as the decision for review was quashed by the High Court (Annesley, Citation2010).

Of course, women’s human rights may continue to be protected under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), in which the UK is still a participant. The ECHR is enshrined into UK law under the Human Rights Act 1998. Provisions within the ECHR may protect women’s rights against the potential risks of the 2018 Withdrawal Act through, for example, Article 14, which forbids discrimination on the grounds of sex or gender. However, whether women’s human rights are protected rests on whether the UK will in fact remain a participant of the ECHR. While the UK’s membership of the ECHR has long been debated, its membership was once again called into question in 2022, following the government’s Rwanda asylum scheme. Under the scheme, those seeking asylum would be deported to Rwanda while their claims would be processed. However, a last-minute intervention was made by the European Court of Human Rights, preventing the first deportation of asylum seekers that was due to take place. Following the intervention, government ministers, including the Home Secretary, have called for Britain to withdraw from the ECHR (Syal & Walker, Citation2023). Withdrawal from the ECHR would serve to further reinforce the Westminster Model, seeing a further shift of power towards the British state at the expense of women’s rights. Moreover, the recent example of the government’s asylum plan serves to illustrate Britain’s diverging policy agenda from that of Europe.

A powerful (male-dominated) core executive

In the classic Westminster Model, the executive retains dominance over the legislature (Lijphart, Citation1999) Rhodes (Citation1995, p. 12) defines the core executive as ‘the complex web of institutions, networks and practices surrounding the prime minister, cabinet, cabinet committees and their official counterparts, less formalised ministerial “clubs” or meetings, bilateral negotiators and interdepartmental committees’. The core executive has been highlighted as a venue for driving forward policy change on gender equality (Annesley & Gains, Citation2010)).

Yet there is currently an absence of critical feminist actors within the core executive. Critical feminist actors within influential decision-making positions have been noted as integral to pushing gender status policies up the executive’s agenda (Annesley & Gains, Citation2010; Childs & Krook, Citation2006). Currently, women comprise 20% of Ministers in the Sunak Cabinet. Moreover, the most powerful roles in Cabinet – including the Prime Minister, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and the Foreign Secretary - are dominated by men. The only exception is the Home Secretary, Suella Braverman. Braverman’s commitment to gender equality is one that can be summarised as innately conservative. On the one hand, some commitments to gender equality have been visible: as Home Secretary, Braverman announced that violence against women would be treated as a ‘national threat’, putting the offence on an equal footing with terrorism (Burford, Citation2023). Yet Braverman’s commitment to feminism was openly questioned by her independent advisor on violence against women, Nimco Ali, who resigned during a live radio interview in December 2022, stating fundamental differences. Braverman also came under fire during her time as Attorney General, following a parliamentary exchange with Labour MP, Ellie Reeves. The exchange came during a parliamentary debate on the Internal Market Bill, which saw Braverman label Reeves’ challenge to the government as an ‘emotional approach’. Such an exchange not only illustrates an actively anti-feminist stance from those within the core executive, but depicts a masculinised discourse around debates on Brexit.

Men can, of course, act as critical feminist actors (Childs & Krook, Citation2006). But an examination of the Sunak government shows that commitments to gender equality policy from those within the Cabinet has been lukewarm. Examining the Prime Minister’s record himself shows that there have been, on one hand, rhetorical commitments towards, for example, tackling violence against women and girls. Commenting on his approach to crime, Sunak noted that being a father of two daughters made the issue of tackling violence against women ‘personally quite important’ (Smyth, Citation2022). Yet so far, rhetorical commitments to violence against women have not been complemented with concrete funding pledges. This absence of critical feminist actors poses a risk to status policies being brought forward on the government’s agenda. Yet given the short amount of time that the Sunak government has been in office and its limited record, it is perhaps too early to ascertain whether commitments to gender equality will translate into concrete policy pledges, or whether they will remain purely rhetorical. As power has increasingly shifted from the European Union towards the core executive, the lack of critical actors pushing forward feminist policies within government risks harming the advancement of gender equality.

Contextual factors: a stifled economy and a centre-right government

Here, we have argued that the overarching governance framework of the Westminster Model acts to the detriment of women’s interests. Yet there are two further contextual factors which, we argue, will risk preventing gender equality policies from being placed on the policy agenda in the future.

Firstly, the stifling of class-based gender equality policies is exacerbated by centre-right Conservative governments that have occupied office since 2010. As discussed earlier, existing research has highlighted that it is often centre-left, rather than centre-right, governments that advance redistributive class-based policies (Annesley & Gains, Citation2013; Htun & Weldon, Citation2018). Class-based policies are costly, and can often sit at odds with centre-right governments committed to lower levels of state spending. This may explain the government’s reluctancy to adopt specific class-based policies that we find in our results, such as the 1992 Pregnant Workers Directive and the 1996 Parental Leave Directive. However, while influencing the likelihood of class-based policies reaching the agenda, the role of ideology in advancing women’s interests should not be overstated. Even in the New Labour years, critical actors still faced difficulties in placing gender equality on the executive’s agenda (Annesley & Gains, Citation2010). And, despite rescinding the social chapter opt out, New Labour and all subsequent governments have continued to oppose further social legislation from the EU (Fagan & Rubery, Citation2018). Rather, social democratic governments can act as a ‘window of opportunity’ for policy reform within the confines of a gendered Westminster Model, but alone they are not sufficient to enact policy change. Simply put: institutions matter.

Secondly, the economic impact of Brexit will pose a challenge to women’s rights on multiple fronts. In the short term, women’s interest groups are likely to be further weakened, given that nearly one-third of their funding came from the EU (Stephenson & Fontana, Citation2019). There is also the long-term economic impact of Brexit itself. The Office for Budget Responsibility (Citation2020) estimated that the economic effects of Brexit will reduce productivity by 4% by the first quarter of 2025. This is set against a backdrop of what the Institute for Fiscal Studies (Zaranko, Citation2020, p. 266) describes as ‘the most severe economic downturn in centuries’, following the global Covid-19 pandemic, the cost-of-living crisis, and subsequent austerity measures pursued after the 2007/8 global financial crash. As such, the economic effects of Brexit are likely to be felt more acutely. In response to the current economic situation, the Conservative government outlined in its 2022 Autumn Statement plans to lower the level of debt and reduce public spending from 2025 onwards, labelled by the WBG, as ‘austerity 2.0’ (Women’s Budget Group, Citation2022). Pursuing a platform of fiscal retrenchment has clear gendered effects. Women are more likely than men to shoulder the burden of austerity measures due to their greater reliance on the state for employment, welfare and services. Yet these measures do not impact all women equally, and instead exacerbate existing inequalities among women. Evidence shows that it is women of colour, low-income women, women with disabilities and lone mothers who are especially more likely to bear the brunt of austerity (Women’s Budget Group, Citation2017). The economic impact of Brexit will also impact the likelihood of gendered policies reaching the policy agenda: in times of economic downturn, governments are less inclined to adopt class-based policies (Annesley & Gains, Citation2013).

Conclusion

This article has examined the role of the European Union in getting gender equality policies onto the British policy agenda and has explored the impact of Brexit on these advancements. In doing so, the article makes an empirical contribution towards understanding the direction of gender equality in a post-Brexit context. Taken together, we argue that the future of gender equality policy in Britain does not appear to be promising for women. The EU once contributed to a reduction in national sovereignty, and as such, its absence facilitates a move towards a masculinised Westminster Model that marginalises women’s interests. As we show in the results, the EU provided a stimulus for Britain’s adoption of a range of class-based policies, addressing inequalities in the sexual division of labour. EU gender equality directives have increased in their scale, frequency, and diversity, with many directives increasingly addressing discrimination that women face on the grounds of their gender. A move towards a masculinised Westminster Model risks rolling back these class-based gains. We also make an analytical contribution to existing literature on gender equality policy by highlighting the variation in the type of gender equality put forward. Progress towards gender equality stemming from the EU has differed according to whether it advances women’s bodily integrity, or women’s economic situation.

While this direction of gender equality policy poses clear implications for women in terms of their economic and social rights, there are also electoral implications for political parties. Political parties in Britain should be mindful that there are electoral benefits in adopting gender equality policies. In particular, policies advancing women’s economic and financial status have been found to be especially salient among women voters (Sanders, Citation2022). Given women comprise the majority of the British electorate (Sanders, Citation2022)), there are clear electoral incentives for political parties in appealing to this demographic.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors of this special issue, Jeremy Richardson and Patrick Diamond, for their valuable feedback and guidance on the draft manuscript. We are especially grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful and insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Sanders

Anna Sanders is a Lecturer in British Politics at the University of York.

Joanna Flavell

Joanna Flavell is a Fellow in International Political Economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Notes

1 See, for example, Gains and Lowndes (Citation2014, p. 545), in which interviews with Police and Crime Commissioners revealed the perception that domestic violence policies are ‘not vote winners’.

References

- Allegretti, A. (2022, June 30). MPs should not bring babies into Commons, says cross-party review. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/jun/30/mps-should-not-bring-babies-into-commons-says-cross-party-review.

- Annesley, C. (2010). Campaigning against the cuts: Gender equality movements in tough times. The Political Quarterly, 83(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2012.02261.x

- Annesley, C., & Gains, F. (2010). The core executive: Gender, power and change. Political Studies, 58(5), 909–929. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00824.x

- Annesley, C., & Gains, F. (2013). Investigating the economic determinants of the UK gender equality policy agenda. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 15(1), 125–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2011.00492.x

- Baldini, G., Bressanelli, E., & Massetti, E. (2022). Back to the Westminster model? The Brexit process and the UK political system. International Political Science Review, 43(3), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120967375

- Baumgartner, F., & Jones, B. (1993). Agendas and instability in American politics. University of Chicago Press.

- Brown, A. (2000). Designing the Scottish parliament. Parliamentary Affairs, 53(3), 542–556. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/53.3.542

- Burford, R. (2023, February 20). Violence against women to be treated with same seriousness as terrorism under new domestic abuse register law. Evening Standard. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/violence-against-women-domestic-abuse-register-terrorism-new-laws-hone-office-suella-braverman-b1061588.html.

- Childs, S., & Krook, M. L. (2006). Should feminists give Up on critical mass? A contingent Yes. Politics & Gender, 2(4), 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X06251146

- Childs, S., & Withey, J. (2006). The substantive representation of women: The case of the reduction of VAT on sanitary products. Parliamentary Affairs, 59(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsj003

- Collignon, S., & Rudig, W. (2021). Increasing the cost of female representation? The gendered effects of harassment, abuse and intimidation towards parliamentary candidates in the UK. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(4), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1968413

- Commission of the European Communities. (1996). Incorporating Equal Opportunities for Women and Men into All Community Policies and Activities, COM(96)67 final. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167.

- Deacon, D., Harmer, E., Downey, J., Stanyer, J., & Wring, D. (2016a). UK News Coverage of the 2016 EU Referendum. Report 1 (6-18 May 2016). https://blog.lboro.ac.uk/crcc/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2016/05/eu-referendum-media-analysis-report-1.pdf.

- Deacon, D., Harmer, E., Downey, J., Stanyer, J., & Wring, D. (2016b). UK News Coverage of the 2016 EU Referendum. Report 1 (19 May – 1 June 2016). https://blog.lboro.ac.uk/crcc/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2016/06/eu-referendum-media-analysis-report-2.pdf.

- Fagan, C., & Rubery, J. (2018). Advancing gender equality through European employment policy: The impact of the UK’s EU membership and the risks of Brexit. Social Policy and Society, 17(2), 297–317. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746417000458

- The Fawcett Society. (2018, March 27). Brexit risks “turning the clock back on gender equality” warns new report. The Fawcett Society. https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/news/brexit-risks-turning-the-clock-back-on-gender-equality-warns-new-report.

- Fiig, C. (2020). Gender equality policies and European union politics. In F. Laursen (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopaedia of politics (pp. 1–27). Oxford University Press.

- Flavell, J. (2023). Mainstreaming gender in global climate governance: Women and gender constituency in the UNFCCC. Routledge.

- Gains, F., & Lowndes, V. (2014). How is institutional formation gendered, and does it make a difference? A new conceptual framework and a case study of police and crime commissioners in England and Wales. Politics & Gender, 10(4), 524–548. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000403

- Galpin, C. (2018, October 8). Women have been excluded from the Brexit debate. UK In a Changing Europe. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/women-have-been-excluded-from-the-brexit-debate/.

- Guerrina, R., & Masselot, A. (2018). Walking into the footprint of EU law: Unpacking the gendered consequences of brexit. Social Policy and Society, 17(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746417000501

- Haastrup, T., Wright, K., & Guerrina, R. (2016, June 17). Women in the Brexit debate: still largely confined to ‘low politics’. British Politics and Policy at LSE. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2016/06/17/women-in-the-brexit-debate-still-largely-confined-to-low-politics/.

- Hankvivsky, O., Merich, D., & Christoffersen, A. (2019). Equalities ‘devolved’: Experiences in mainstreaming across the UK devolved powers post-equality act 2010. British Politics, 14(2), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-018-00102-3

- Hannah, E., Roberts, A., & Trommer, S. (2022). Gender in global trade: Transforming or reproducing trade orthodoxy? Review of International Political Economy, 29(4), 1368–1393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1915846

- Harman, H. (2017). A woman’s work. Allen Lane.

- Hemmati, M., & Röhr, U. (2009). Engendering the climate-change negotiations: experiences, challenges and steps forward. Gender and Development, 17(1), 19–32.

- Higer, A. (1999). International women’s activism and the 1994 Cairo population conference. In M. Meyer, & E. Prügl (Eds.), Gender politics in global governance (pp. 122–141). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Himmelweit, S. (2005). Making policymakers more gender aware: Experiences and reflections from the Women’s Budget group in the United Kingdom. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 27(1-2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1300/J501v27n01_07

- Htun, M., & Weldon, S. L. (2010). When do governments promote women’s rights? A framework for the comparative analysis of sex equality policy. Perspectives on Politics, 8(1), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592709992787

- Htun, M., & Weldon, S. L. (2018). The logics of gender justice: State action on women’s rights around the world. Cambridge University Press.

- Keck, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. Cornell University Press.

- Lijphart, A. (1999). Patterns of democracy. Yale University Press.

- Mackay, F. (2014). Nested newness, institutional innovation and the gendered limits of change. Politics & Gender, 10(4), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000415

- MacLeavy, J. (2018). Women, equality and the UK’s EU referendum: Locating the gender politics of Brexit in relation to the neoliberalising state. Space and Polity, 22(2), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2018.1502610

- Mahoney, C., & Baumgartner, F. (2008). Converging perspectives on interest group research in Europe and America. West European Politics, 31(6), 1253–1273. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380802372688

- Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should Blacks represent Blacks and women represent women? A contingent ‘Yes’. The Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647821

- Mazey, S. (1995). The development of EU equality policies: Bureaucratic expansion on behalf of women? Public Administration, 73(4), 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1995.tb00848.x

- Mazey, S. (1998). The European Union and women’s rights: From the Europeanization of national agendas to the nationalization of a European agenda? Journal of European Public Policy, 5(1), 131–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501768880000061

- Mazey, S. (2012). Policy entrepreneurship, group mobilisation and the creation of a new policy domain: Women’s rights and the European union. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Constructing a policy-making state? Policy dynamics in the EU (pp. 125–144). Oxford University Press.

- Mazey, S., & Richardson, J. (2006). The Commission and the Lobby. In D. Spence (Ed.), The European Commission (pp. 279–292). London: Harper.

- Mazey, S., & Richardson, J. (2015). Shooting where the ducks are: EU lobbying and institutionalised promiscuity. In S. Mazey, & J. Richardson (Eds.), European union: Power and policy-making, 4th edition (pp. 419–443). Routledge.

- Meyer, M., & Prügl, E. (1999). Gender politics in global governance. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Ministry of Justice. (2020). Government response to consultation on the departure from retained EU case law by UK courts and tribunals. HM Stationery Office.

- Nott, S. (1999). Mainstreaming equal opportunities: Succeeding when All else has failed? In A. E. Morris, & T. O’Donnell (Eds.), Feminist perspectives on employment Law (pp. 203–221). Cavendish.

- Office for Budget Responsibility. (2020). Economic and fiscal outlook: March 2020. OBR.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2022a). Female employment rate (aged 16 to 64, seasonally adjusted): %. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/timeseries/lf25/lms.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2022b). Male employment rate (aged 16 to 64, seasonally adjusted): %. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/timeseries/mgsv/lms.

- O’Hagan, A. (2017). Gender budgeting in Scotland: A work in progress. Administration, 65(3), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1515/admin-2017-0022

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1995). Understanding governance. Open University Press.

- Richardson, J. (2006). European union: Power and policy-making. Routledge.

- Richardson, J. (2018). The changing British policy style: From governance to government?. British Politics, 13(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-017-0051-y

- Richardson, R., & Rittberger, B. (2020). Brexit: Simply an omnishambles or a major policy fiasco? Journal of European Public Policy, 27(5), 649–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1736131

- Sabatier, P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences, 21(2-3), 129–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00136406

- Sanders, A. (2022). The impact of gendered policies on women’s voting behavior: Evidence from the 2015 British general election. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, [Online first] https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2022.2068118

- Sanders, A., Gains, F., & Annesley, C. (2021). What’s on offer: How do parties appeal to women voters in election manifestos? Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(4), 508–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1968411

- Smyth, C. (2022, November 18). Rishi Sunak: Daughters motivate me to make the streets safer for women. The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/daughters-motivate-rishi-sunak-to-make-the-streets-safer-for-women-3q589zc7x.

- Spalter-Roth, R. (1995). Outsider issues and insider tactics: Strategic tensions in the Women’s policy network during the 1980s. In M. M. Ferree, & P. Y. Martin (Eds.), Feminist organizations: Harvest of the new women’s movement (pp. 105–127). Temple University Press.

- Squires, J. (2005). Is mainstreaming transformative? Theorizing mainstreaming in the context of diversity and deliberation. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 12(3), 366–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxi020

- Stephenson, M. (2018, May 14). The economic impact of Brexit on women. UK in a Changing Europe. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/the-economic-impact-of-brexit-on-women/.

- Stephenson, M., & Fontana, M. (2019). The likely economic impact of brexit on women: Lessons from gender and trade research. In M. Dustin, N. Ferreira, & S. Millns (Eds.), Gender and queer perspectives on brexit (pp. 415–438). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stratigaki, M. (2005). Gender mainstreaming vs positive action. European Journal of Women's Studies, 12(2), 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506805051236

- Syal, R., & Walker, P. (2023, February 6). Suella Braverman’s Rwanda flight ‘dream’ could happen this year, sources say. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/feb/06/sunak-echr-exit-european-court-asylum-bill.

- Taylor, H., Florisson, R., & Wilkes, M. (2023). A year of uncertainty? The retained EU law bill 2022 and UK worker’s rights. Work Foundation. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/lums/work-foundation/Ayearofuncertainty.pdf.

- Topping, A. (2021, January 19). UK government accused of discriminating against maternity leave-takers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/law/2021/jan/19/uk-government-accused-discriminating-maternity-leave.

- Women’s Budget Group. (2017). Intersecting inequalities: The impact of austerity on black and minority ethnic women in the UK. Women’s Budget Group.

- Women’s Budget Group. (2022). Misguided plans for austerity 2.0: Women’s Budget Group Response to Autumn Statement 2022. https://wbg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/WBG-budget-response-Nov-2022-FINAL.pdf.

- Women’s Budget Group and the Fawcett Society. (2018). Exploring the economic impact of Brexit on women. https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=049e3458-12b0-4d0f-b0a6-b086e860b210.

- Zaranko, B. (2020). Spending review 2020: COVID-19, Brexit and beyond. IFS.