?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

How does the politicisation of trade policy affect the lobbying strategies chosen by interest groups? Several studies have shown that business associations tend to focus more on inside lobbying and citizen groups more on outside lobbying. We argue that politicisation makes this difference in lobbying strategy even more pronounced. Facing an issue that is contested and publicly salient, we should see business actors move even more toward inside lobbying and citizen groups move even more toward outside lobbying. We test this argument using a unique combination of evidence from a survey with 691 interest groups and an analysis of Twitter usage with respect to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) by 993 interest groups. The empirical evidence largely supports our argument. By making and testing this argument, we contribute to the literatures on the politicisation of trade policy and interest group strategies.

Introduction

In February 2013, the United States and the European Union (EU) announced the start of negotiations for a transatlantic trade agreement, soon called Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Five months later, the first round of negotiations between officials from both sides took place in Washington, DC. Business interests closely followed these negotiations from the beginning, with most of them backing a broad and comprehensive agreement between the two sides (Dür & Lechner, Citation2015; Young, Citation2016). Initially, many of them also publicly expressed their support for the negotiations, for example via the creation of the Business Alliance for TTIP in May 2013. After a couple of citizen groups managed to raise the public salience of the negotiations across several European countries by mid-2014 (Eliasson & Garcia-Duran Huet, Citation2018), however, business voices largely drowned in the public debate (Bauer, Citation2016). In the face of politicisation, it seems that business interests went into hiding.

This sequence of events begs the following, general question: how does politicisation – defined as contestation and high public salience (De Bièvre et al., Citationin press) – affect lobbying on a specific policy? In answering this question, we rely on the common distinction between inside and outside lobbying (Beyers, Citation2004; Dür & Mateo, Citation2016; Kollman, Citation1998). Inside lobbying refers to a strategy that is directly aimed at decision-makers, including tactics such as direct contacts with them or participation in governmental committees. Outside lobbying, by contrast, refers to a strategy that relies on public pressure to influence public policies. We argue that politicisation makes outside lobbying in favour of a policy opposed by many citizens potentially costly. This argument leads us to expect that politicisation pushes supporters of a policy toward relatively more inside lobbying and the opponents toward relatively more outside lobbying.

We develop our argument for and test it on the case of trade agreements. Business associations are the key constituency supporting agreements that liberalise and regulate trade. For them, we expect the cost–benefit analysis of outside lobbying to gradually turn negative as politicisation increases. For citizen groups, by contrast, many of which tend to oppose trade agreements, outside lobbying should become more attractive in the face of politicisation. The overall expectation hence is for politicisation to accentuate differences across group types in terms of choice of lobbying strategy.

Using a unique combination of both survey and Twitter data, we find support for this expectation. The survey covers interest groups from across the globe that engaged in lobbying on a variety of trade agreements, some of which (concretely TTIP and the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the EU) were politicised in some countries. Questions on the tactics used in lobbying on these trade agreements allow us to create an index of relative outside lobbying. The Twitter data relate to tweets sent by European business associations and citizen groups over the period 2012-2016. We calculate the share of tweets sent by these groups that relate to TTIP. As expected, for both the survey and the Twitter data, we find that the difference in lobbying strategies between business associations and citizen groups increases in the context of politicisation. Contrary to the causal mechanism outlined below, however, this is mainly driven by citizen groups’ reorientation towards outside lobbying and less by business associations’ greater focus on inside lobbying.

In making and testing this argument, the paper makes two key contributions to the existing literature. On the one hand, the findings speak to research on contestation and politicisation (De Bièvre & Poletti, Citation2020; De Vries et al., Citation2021; Kay & Evans, Citation2018; Zürn et al., Citation2012), particularly to this special issue's theme of actors’ reactions to politicisation (De Bièvre et al., Citationin press). Concretely, we show that politicisation does not simply move a debate from outside the public view into the public realm, but can also make the arguments of one side more prominent in this debate. This can be seen as normatively desirable in the sense that it strengthens voices that otherwise may not be heard; but it can also be objectionable from a normative point of view as the public does not have the chance to hear both sides of a debate.

On the other hand, we speak to the large literature on interest group strategies (Beyers, Citation2004; Dür & Mateo, Citation2016; Kollman, Citation1998). We confirm existing findings of the strong impact of group type on the choice of interest group strategy. The novel aspect of our paper in this respect is to show that the group type effect is particularly pronounced under conditions of politicisation. This is not an obvious point (for partly alternative views, see for example Baumgartner et al., Citation2009, p. 150; Dür & Mateo, Citation2016, pp. 99–100; Hanegraaff et al., Citation2016, p. 574; Willems, Citation2022). In the face of politicisation, one could also expect strategies to converge (because politicisation makes all groups realise the need to engage in outside lobbying) or stay stable (because factors internal to organisations such as their relative resource endowments make them more or less prone to engage in outside lobbying independent of politicisation). The finding that the effect of group type on lobbying strategies indeed gets stronger when the public gets involved in an issue highlights that groups’ strategy choice is influenced by more than just considerations of how to best influence specific policy outcomes. The choice of lobbying strategy is also shaped by concerns about organisational survival (in the case of citizen groups) and avoiding a public backlash (in the case of business actors).

Lobbying strategies in the face of politicisation

Business actors, including business associations and firms, have long been lobbying on trade policy (Bauer et al., Citation1972; Dür, Citation2010; Schattschneider, Citation1935). Some non-business interests, such as consumer groups, labour unions, and environmental organisations, have also been involved in trade policy lobbying (Dür & De Bièvre, Citation2007; Jarman, Citation2008). This lobbying can take place in the form of inside lobbying or outside lobbying. Inside lobbying refers to direct contacts with decision-makers and participation in government committees (Beyers, Citation2004; Dür & Mateo, Citation2016; Junk, Citation2016; Schlozman & Tierney, Citation1986) and mostly works via the transmission of expertise from interest groups to decision-makers. By contrast, outside lobbying refers to attempts at influencing public policy via public opinion (Kollman, Citation1998). Tactics commonly associated with outside lobbying are social media campaigns, demonstrations, TV or newspaper ads and so on. Common to these tactics is the aim to either change (some) citizens’ views on an issue or increase the salience of that issue for citizens.

At any time, most interest groups engage in both inside and outside lobbying. Nevertheless, interest groups vary in their relative focus on these two broad lobbying strategies. A large literature discusses the determinants of this variation. Among the factors discussed are group type (Dür & Mateo, Citation2016; Kollman, Citation1998; Kriesi et al., Citation2007), political institutions (Beyers, Citation2004; Weiler & Brändli, Citation2015), whether groups are in the defensive on an issue (Kollman, Citation1998), the resources that groups possess (Chalmers, Citation2013), the extent to which a group needs to compete for resources (Hanegraaff et al., Citation2016), and the type of policy – distributive or regulatory – concerned (Dür & Mateo, Citation2016).

We argue that the extent to which a policy is politicised also matters for interest groups’ choice of strategy. Much of the time, trade policy lobbying takes place with only little public attention. This makes sense as for citizens, the direct material consequences of trade policy choices often are relatively small. Nevertheless, sometimes trade policy does garner significant public attention. Mostly, this is the case for trade agreements rather than other trade policy decisions. Illustratively, in 1999 the meeting of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle was met by heavy protests (Aaronson, Citation2001). More recently, the Anticounterfeiting Trade Agreement (Dür & Mateo, Citation2014), the TTIP negotiations (Duina, Citation2019; Gheyle & De Ville, Citation2019), and the EU–Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) (De Bièvre & Poletti, Citation2020; Hübner et al., Citation2017) were heavily contested in Europe. In all these cases, a broader public got involved in the trade policy debate.

How does this variation in public salience and contestation matter for the lobbying strategies that interest groups opt for to influence political decisions? In earlier research, we argue that the ‘difference between group types in relative focus on inside lobbying persists independent of the public salience of the issue’ (Dür & Mateo, Citation2016, p. 100). Concretely, we focus on business associations (that is, groups that have either firms or associations of firms as members) and citizen groups (that is, groups that defend interests that do not directly reflect the professions or vocations of their members or supporters, see Berry, Citation1999, p. 2). Our argument is that because of factors internal to them, business actors should focus relatively more on inside lobbying than citizen groups, independent of public salience. Similarly, Baumgartner et al. (Citation2009, p. 150) argue that groups’ policy goals matter more for their choice of strategy than the public salience of the issues they are active on. Finally, Hanegraaff et al. (Citation2016, p. 574) expect all interest groups independent of type to rely more on outside lobbying in the context of politicisation. In the present article, we go one step further than these existing studies in expecting the difference in lobbying strategy to become even more pronounced the more a policy becomes politicised.

The starting point for this argument is that citizen groups can be expected to generally rely relatively more on outside lobbying than firms or business associations, as many of them depend on public support for organisational maintenance (Dür & Mateo, Citation2016). For them, outside lobbying serves a double purpose. On the one hand, it increases their chances to influence public policy in line with their convictions via ‘conflict expansion’ (Schattschneider, Citation1960). The broader public then may be a power resource that allows citizen groups to offset other advantages that business interests possess. This is so because the higher the salience of a policy, the more likely that politicians listen to public opinion (Culpepper, Citation2011). On the other hand, outside lobbying offers an opportunity to showcase their lobbying to potential supporters among the broader public. Doing so is important as citizen groups rely on broad support for organisational survival (see also Hamilton, Citationin press).

Business associations have less to gain from outside lobbying. They can influence policies in the absence of conflict expansion. What is more, they are less dependent on outside lobbying in their pursuit of organisational survival. They have no need to showcase their lobbying because their members – firms or other business associations – have the capacity to observe the impact of the lobbying directly (in terms of policy outputs favourable to the firms they represent). This reasoning applies even more strongly to firms that decide to lobby without acting through business associations. In short, at any time we can expect business actors to be less focused on outside lobbying than citizen groups.

The politicisation of a policy – in this case trade policy – should make this difference even more pronounced. Politicisation means that both the salience and contestation of an issue increases (De Bièvre et al., Citationin press; Zürn et al., Citation2012, p. 74). For citizen groups, this has the double benefit of making it more likely that an outside strategy is successful in shaping a policy outcome and making outside lobbying more effective in gaining members or supporters. Politicisation hence can be expected to push citizen groups even more towards outside lobbying.

It might be expected that also business actors respond to politicisation by increasing their reliance on outside lobbying. In the end, they might find it necessary to counteract citizen groups’ influence on the public or at least defend themselves when publicly challenged, if the two take opposite stances on the issue (Willems, Citation2022). In modern trade policy, indeed, business actors often find themselves pitched against citizen groups (Young, Citation2016). Most business actors tend to support trade liberalisation and by extension trade agreements that aim at liberalising trade, as import-competing firms have increasingly disappeared (Hathaway, Citation1998). The remaining import-competing firms now are opposed by exporting and import-dependent firms, and firms that engage in both exports and imports, all of which support trade agreements. Once aggregated to the level of business associations, it is thus rare for the preferences of the import competitors to prevail (except for a few sectors, see below). By contrast, many citizen groups have been heavily critical especially of trade agreements, as they see them as harmful for the environment, democracy, labour rights and so on.

Consequently, one could imagine business actors to increase their use of outside lobbying to defend their position vis-à-vis the public in parallel to citizen groups’ enhanced efforts in that respect. This is particularly so as business actors can be expected to have the (financial) resources to engage in comprehensive campaigns to shape public opinion (Willems, Citation2022).

We argue, however, that in the face of politicisation business actors tend to (relatively) retreat from outside lobbying. For one, they always need to balance the potential gains from a successful lobbying campaign against the potential costs from taking a position that is unpopular. These costs arise because consumers may reduce purchases from businesses seen as going against the public interest. In fact, consumer boycotts – so-called buycotts – were successful in making large companies such as Nestle, Mitsubishi, and Nike change specific practices (Holzer, Citation2010).

What is more, two factors should make it difficult for business actors to sway the public. First, citizen groups enjoy greater trust among the public than business associations. Dür (Citation2019, Supplementary information), for example, shows that in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, citizens indicate more trust towards specific citizen groups (Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth) than (peak) business associations. In the absence of trust, persuasion is difficult. The relative lack of trust also makes it easy for business actors’ antagonists to portray any policy favoured by the former as only serving business interests (as opposed to citizen groups that can plausibly claim to represent interests that go beyond those of their members). Second, the frames that citizen groups can use in such a campaign are likely intrinsically more powerful than those that business actors can use (for a discussion of which arguments are most likely to win, see for example Keck & Sikkink, Citation1998, pp. 26–28). For example, in the TTIP debate the argument that this agreement would create jobs turned out to be far less effective in shaping public opinion than the argument that TTIP might allow companies to sue states for compensation (Dür, Citation2019). The frame used by opponents of TTIP that the agreement would pose a danger to European standards also was frequently referred to in mainstream mass media (Conrad & Oleart, Citation2020).

In short, we expect the politicisation of trade agreements to push citizen groups more toward outside and business associations more toward inside lobbying. In the public sphere, the consequence is similar to what in the case of public opinion (Noelle-Neumann, Citation1974) called the ‘spiral of silence’, namely the silencing of opposition to what is perceived as a majority opinion. The following hypothesis summarises this argument: The greater the politicisation of a trade agreement, the more distinct the lobbying strategies of citizen groups and business actors, with the former showing a greater focus on outside and the latter a greater focus on inside lobbying.

So far, we have assumed that all business actors support trade agreements. While at present in highly developed countries most indeed do, some tend to come out in opposition. In Europe, this mainly concerns farmers’ associations, as parts of the European agricultural sector fear competition from farmers in third countries. In line with the logic set out above, we do not expect these actors to reduce their reliance on outside lobbying in the face of politicisation. As their demands are consistent with the demands voiced by citizen groups and other actors contesting a trade agreement, they do not need to fear a public backlash to their lobbying efforts. We take up this issue in the empirical analysis below.

In this analysis, we rely on both survey and Twitter data, thus combining a subjective (because self-reported) and an objective (because directly observed) measure of interest group strategy. To the extent that the results from the two data sources coincide, their plausibility increases significantly. Alternatively (or in addition), we could have looked at news coverage of interest groups across topics. For our purposes, however, media prominence has the disadvantage that it reflects both groups seeking coverage and media seeking out interest groups (Willems, Citation2022). By contrast, the Twitter data that we use only reflect interest groups’ decisions to tweet more or less on a topic.

The empirical tests only consider business associations – which represent firm interests – rather than the firms themselves. The reason for this is that the survey we draw upon did not include any firms. What is more, individual firms mostly do not use Twitter to convey their positions on trade policy issues. If we had data for firms, we would expect the findings to be even more pronounced for them. When thinking about business actors overall, therefore, we see our results as conservative estimates.

Testing the argument using survey evidence

We use survey data from Dür et al. (Citation2019) for a first test of our argument.Footnote1 The survey aimed to include interest groups from across the world with an interest in trade policy. To arrive at such a sample, the sampling frame encompassed interest groups a.) attending one of the WTO's ministerial meetings; b.) indicating an interest in trade policy in the EU's Transparency Register; c.) participating in Civil Society Dialogue meetings between the EU and third countries; or d.) organising the ASEAN Civil Society Conference. In terms of types of interest groups, the survey covered business associations, professional associations, citizen groups, and labour unions. The resulting sample comprised 2841 organisations. In spring 2019, these groups were contacted by email and invited to participate in an online survey.

Following two reminders, 691 groups answered the survey. The resulting response rate is 24.3 per cent, which is decent given the heterogeneous nature of the sample. indicates the continent in which the headquarters of the groups that responded are located and the type of group. As can be seen, a large majority of the respondents stems from Europe, which is in line with the sampling frame. A majority of the groups are business associations, which also reflects the distribution of groups in the sampling frame.

Table 1. Composition of the sample.

For this study, we use the subsample of all groups that responded to a question on the trade agreement or trade negotiation that their organisation had been most active on.Footnote2 As it is possible that a group never lobbies on a trade negotiation or agreement, groups could abstain from answering the question and then did not see a set of follow-up questions. A valid response was provided by 494 groups (71 per cent). With 54.5 per cent, the share of business associations in this subsample is nearly the same as in the overall sample.

Among the follow-up questions was one concerning the importance of seven distinct lobbying tactics for their efforts to influence the agreement or negotiation.Footnote3 Three of them clearly form part of inside lobbying (direct personal contact with decision-makers, carry out or commission research, and serve on governmental advisory commissions or boards), whereas four form part of outside lobbying (organise or participate in protests or demonstrations, distribute press releases, use social media, and organise an info event or workshop). For each tactic, groups could indicate their importance for them on a five-point scale from not important at all (value of 0) to very important (value of 4).

To test our hypothesis, we need a dependent variable that captures the relative importance of outside to inside lobbying. We therefore first calculated the mean response across the three inside and the four outside tactics and then calculated the share of outside lobbying as:

(1)

(1) This formula gives a value between 0, if a group only engages in inside lobbying, and 100, if a group fully focuses on outside lobbying. The resulting variable takes on values across its full theoretical range and has a mean of 44, indicating a slight dominance of inside lobbying. The standard deviation of 12 implies some variation across the mean, but also that many groups divide their efforts quite evenly across inside and outside lobbying. This variable is equivalent to the one used by (Hanegraaff et al., Citation2016), who asked interest groups to indicate the percentage of their lobbying efforts that they invested in outside lobbying. The mean that they obtained (39) is very close to ours, but they found more variation across groups than we do (the standard deviation in their sample is 28).

We need to operationalise two predictors to test our argument. For one, this concerns the type of interest groups. The variable we use distinguishes between business associations (Business association), professional associations (Professional association), labour unions (Labour union), and citizen groups (Citizen group). It was manually coded by two coders working independently of each other, with a third person adjudicating in case of disagreement. In one model below, we also use a question included in the survey on whether the groups supported or opposed the agreement that they lobbied on to distinguish between Business favourable (i.e., business associations that support the agreement) and Business unfavourable (i.e., business associations that oppose the agreement or are indifferent). As expected, a clear majority of business associations support the trade agreement they lobbied on, but about a quarter is coded 1 on Business unfavourable.

The second predictor that we need to operationalise is the politicisation of trade agreements. The respondents indicated a variety of agreements or negotiations that they were primarily active on, including TTIP, CETA, the WTO, the EU's Economic Partnership Agreements with various countries, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement and so on. Ideally, we would have established the degree of politicisation of each on a continuous scale. Because of a lack of comparable data, however, this proved impossible. Instead, we opted to rely on a dichotomous measure that considers TTIP and CETA as politicised. In fact, these two agreements were clearly politicised in at least some countries (De Bièvre & Poletti, Citation2020). They also stand out in terms of the frequency with which they were mentioned by interest groups as the agreements they were primary active on (136 mentions of TTIP and 60 mentions of CETA). As none of the other agreements mentioned stand out in terms of politicisation (e.g., contemporary WTO negotiations hardly feature in public discourse), we decided to treat all of them as non-politicised.Footnote4

The politicisation of TTIP and CETA, however, did not encompass all countries involved in their negotiation. For CETA, Hurrelmann and Wendler (Citationin press) establish politicisation using qualitative evidence. According to their coding, the agreement was politicised in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Spain. We follow this coding, as it broadly concurs with our reading of the evidence (including from Google Trends, see below).

For TTIP, we relied on several sources to establish a 6-point index. For each of the following indicators, we gave a point to a country that fulfilled the condition:

– Was the country among the top 15 countries in the EU in terms of Google search queries to TTIP? For this, we used Google Trends, which offers relative search volume on Google by country (queried using the gtrendsR package in R, see Massicotte & Eddelbuettel, Citation2022). Using ‘TTIP’ as search term, we first established that the relative search volume across all countries was highest in Austria. We then used Austria as comparison when querying all other countries, allowing us to arrive at data that indicates the importance of the TTIP search term in all EU member countries relative to the one in Austria.

– Was public support for TTIP in the country lower than 50 per cent in either 2014 or 2016? For this we used responses to a question on support for a ‘free trade and investment agreement between the EU and the USA’ from Eurobarometer polls in fall 2014 and fall 2016 (European Commission, Citation2015, Citation2017).

– Did public support for TTIP in the country decline between 2014 and 2016?

– Did public support for TTIP in the country decline between 2014 and 2016 by more than 10 per centage points?

– Did the number of citizens signing the European Citizens’ Initiative on TTIP and CETA exceed the necessary country quorum by at least the double (Stop TTIP, Citation2015a)?

– Were more than 10 citizen groups from the country listed as supporting the STOP TTIP campaign (Stop TTIP, Citation2015b)?

We then classified TTIP as politicised in all countries with at least 3 points (i.e., the mid-point) on the six-point index. This applies to Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Section A.2 in the Appendix provides more information on this coding.

In total, across the two agreements, this approach led us to classify 158 associations as having lobbied in a politicised environment (Politicised environment). This concerns 114 groups lobbying on TTIP and 44 groups lobbying on CETA. The proportion of associations is relatively similar across the four group types included in the study (between 26 and 36 per cent).

In some of our models, we control for groups from outside the EU (based on the groups’ headquarters); their number of full-time employees as a measure of their resources (the data for this variable result from a question in the survey); and whether they have an office outside of their home country as a further measure of resources (which was coded manually for all groups in the sample relying on publicly available information). offers summary statistics for all these variables.

Table 2. Summary statistics (Survey analysis).

We use ordinary least squares regression to estimate the model. The following equation reflects our main model:

(2)

(2) where i is the individual group, Group type is a categorical variable distinguishing between business associations, citizen groups, labour unions, and professional associationsFootnote5, Ci refers to a vector of control variables, and

is the error term. Given our argument, our focus is on the coefficient

, as the interaction between group type and the politicisation variable allows us to test our hypothesis.

Given that the survey data that we use do not have a time dimension, it is possible that our results reflect the impact of groups’ outside focus on politicisation rather than (or in addition to) the impact of politicisation on groups’ outside focus. Such reverse causality would be present if for exogenous reasons in some countries (but not in others) many citizen groups had increased their relative outside lobbying on TTIP and CETA leading to greater politicisation of these agreements in these countries. It is indeed likely that interest groups’ outside lobbying contributed to their politicisation. The available evidence, however, suggests that initially only few groups contested these agreements (for the case of TTIP, see Gheyle & De Ville, Citation2019), which then made other groups join the lobbying effort. Reverse causality thus is unlikely to explain the results that we present here. The analysis of Twitter data below can further address the concern of reverse causality, as these data contain a temporal dimension that allows for a before and after comparison.

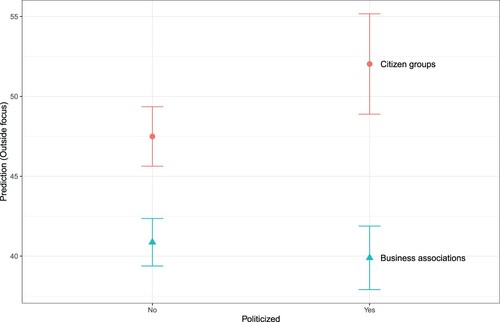

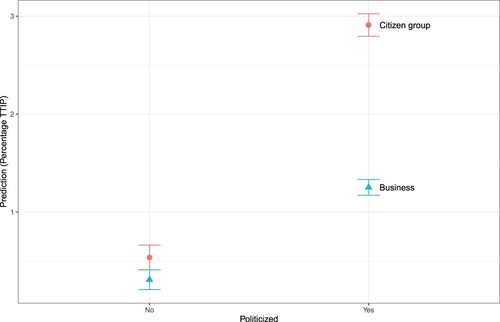

shows the results from our main models. In Model 1, we only include the key predictors (group type and Politicised environment) and their interaction. The baseline for the interpretation of the group type effects are citizen groups. The results indicate that even in a non-politicised environment, business and professional associations rely less on outside lobbying than citizen groups.Footnote6 This finding is in line with existing research (Dür & Mateo, Citation2016). At the same time, a politicised environment increases citizen groups’ reliance on outside lobbying (this can be derived from the positive and statistically significant coefficient for Politicised environment). The key coefficient for our analysis is the one for the interaction Politicised × Business association. This coefficient is negative and statistically significant. allows us to interpret the meaning of this coefficient. As indicated before, even in a non-politicised situation, business associations rely relatively less on outside lobbying than citizen groups. Importantly, this gap increases in a politicised environment from about 6.6 points on a scale from 0 to 100 to about 12.1 points. Both the gap and the increase in the gap are substantively important. Contrary to what we expected, however, the widening of the gap is driven nearly solely by citizen groups moving towards outside lobbying, with business associations’ move away from outside lobbying not statistically significant.

Figure 1. Politicised environment × Business association (Survey data).

Note: The figure is based on the results reported in Model 1 in . The dependent variable ranges from 0 (only inside lobbying) to 100 (only outside lobbying). The whiskers indicate the 90% confidence intervals.

Table 3. Models explaining outside focus.

In Model 2, we add the control variables mentioned above. Doing so slightly increases the effect size of the interaction. According to this model, an original gap of 5.7 points increases to 12.4 points in a politicised environment. Only one of the coefficients for the control variables is (weakly) statistically significant. Associations from outside the EU focus slightly more on outside lobbying than associations from inside the EU.

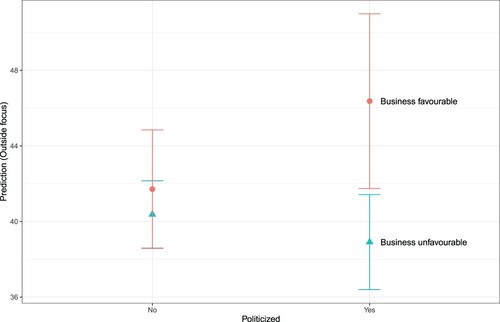

So far, we have assumed that the main difference is between citizen groups and business associations. As briefly discussed in the argument section, however, some business associations may oppose a trade agreement, for example because they fear import competition or dislike specific provisions in a trade agreement. In our sample, among those business associations for which we can establish this, 26 per cent opposed the agreement they lobbied on. For example, 23 business associations indicated that they opposed TTIP and 4 indicated so for CETA.

In Model 3 in , we account for the possibility that business associations favourable to a politicised agreement opt for a different strategy than those not favourable to the agreement. As explained above, this is indeed what we expect based on our argument, as business groups whose preferences are in line with the citizen groups that contest the agreement have no reason to hide even in the face of politicisation. We test this expectation by replacing Business association with the two variables Business favourable and Business unfavourable. The results strongly support our argument: the interaction between Politicised environment and Business favourable remains negative and statistically significant. The substantive effect of this interaction is even larger than the one of Politicised environment × Business association in the previous models. Even more interestingly, the coefficient for the interaction between Politicised environment and Business unfavourable is not statistically significant and close to zero. helps interpret this finding. As can be seen, business associations opposed to TTIP responded to politicisation in a similar manner as citizen groups, that is, by shifting resources towards outside lobbying. By contrast, Business favourable shows a slight move towards inside lobbying. While these shifts themselves fail to reach statistical significance (largely because the number of observations used to estimate the effects is small), the evidence still adds plausibility to our argument.

Figure 2. Allowing for favourable and unfavourable business (Survey data).

Note: The figure is based on the results reported in Model 3 in . The whiskers indicate the 90% confidence intervals.

As robustness checks, we also ran the analysis separately for each of the four outside tactics included in the survey. In each of these four models, the coefficient for the interaction between Politicised environment and Business association is negative as expected, but none of these coefficients reaches statistical significance. This indicates that the shifts that we see in the previous models is a combination of reduced outside and increased inside lobbying. The results for these models are available in the online appendix (see Table A2). Moreover, we implemented a jackknife test, dropping one country at a time. Across all models, the coefficient of the key interaction term remains similar in size to the ones reported (Figure A2 in the online appendix shows a histogram of the resulting coefficients).

Overall, this evidence supports our argument that citizen groups and business associations – or, more concretely, business associations favourable to a trade agreement – tend to exhibit greater differences in terms of lobbying strategies in the context of politicisation.

Testing the argument using Twitter data

We complement the previous analysis with a test of our hypothesis relying on Twitter data. Twitter is one of many tools that interest groups use in their lobbying activity (Chalmers & Shotton, Citation2016). While Twitter usage does not tell us how much outside relative to inside lobbying groups engage in on a specific topic, it can tell us about a group's relative focus on a specific topic in their overall outside lobbying. That is, the question we can address with this data is whether citizen groups and business associations react differently to the politicisation of an issue in terms of their focus on that topic relative to their overall Twitter usage. Based on our argument, we would expect citizen groups to strongly increase their focus on the politicised topic, whereas we would not expect such an increase for business associations.

To test this expectation, we looked up the Twitter handles of all the (EU-based) business associations and citizen groups in the sample used for the survey. This concerns a total of 1682 organisations, 1245 of which are business associations and 437 are citizen groups. Of these, 1226 have a Twitter handle. The share of business associations and citizen groups that have a Twitter handle is very similar in our sample (74% and 72%, respectively). We also lose all groups who joined Twitter after 2016, when the TTIP debate largely ended. This leaves us with a final number of 993 unique groups (705 business associations and 288 citizen groups). This sample includes associations from all EU member countries besides Estonia and Malta and from the EU level, but Central and Eastern European countries are underrepresented relative to their population sizes (e.g., 12 groups come from Poland, but 152 from Germany).

For each of the Twitter handles, we scraped all tweets sent between 1 January 2012, and 31 December 2016.Footnote7 Overall, we downloaded nearly 3 million tweets, about evenly split across business associations and citizen groups. Given that we have fewer citizen groups in our sample, this shows that citizen groups send more tweets on average than business associations.

We then searched the tweets for mentions of TTIP using a full text search of ‘TTIP’, ‘TAFTA’, and ‘EU-US trade deal’ (always ignoring case). The ‘TTIP’ search does not only capture tweets that simply mention TTIP, but also those that use (one or several of) the #TTIP, #noTTIP or #stopTTIP hashtags. The ‘TAFTA’ string allows us to capture tweets in the early stages of the negotiation, when the TTIP label was not yet fully established. We included ‘EU-US trade deal’ in our search for completeness's sake, but without this adding many new tweets. The TTIP acronym is well-established across languages. To be on the safe side, we still searched for versions in other languages, such as PTCI (French) and ATCI (Spanish), but manually inspecting the resulting (brief) lists of tweets showed that they do not relate to the trade agreement.

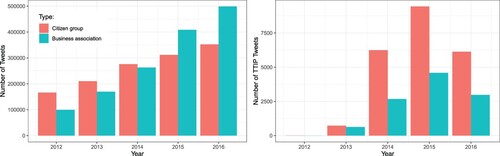

Just over one per cent of all tweets sent by the groups in our sample over this five-year period turn out to mention TTIP. In , we show both the overall number of tweets per year and type of actor (left pane) and the number of tweets on TTIP per year and type of actor (right pane). The former illustration shows that overall, the actors in our sample increased the number of tweets they sent over time. This is not astonishing as Twitter generally became more popular over this period. An interesting observation is that the growth is much more rapid for tweets sent by business associations than those sent by citizen groups. Clearly, business associations discovered Twitter later, but then found it useful as a means of communicating. Even in 2016, however, at least among the actors in our sample, citizen groups on average tweeted more than business associations. Concretely, the mean number of tweets sent in that year by a citizen group is 1223, whereas the mean number sent by a business association is 748. These average numbers hide much variation across groups, with some groups hardly sending any tweets and others sending around 1000 tweets per month.

The plot in the right pane shows that TTIP was completely absent from the groups’ Twitter debate in 2012 and only slowly emerged as a topic in 2013. Both types of groups, but especially citizen groups, then sent a large number of tweets on TTIP in 2014 and 2015, before the topic again declined in prominence in 2016. This development is in line with other indications of the timing of the politicisation of TTIP in some European countries (Eliasson & Garcia-Duran Huet, Citation2018).

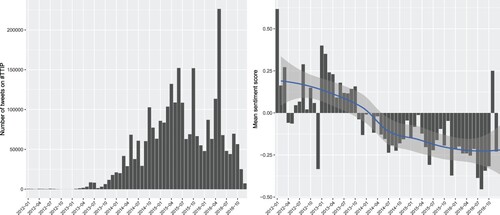

To put the data for the groups in our sample in the broader context, we also downloaded all tweets sent over this period using the Twitter hashtag #TTIP. The resulting 2.7 million tweets do not encompass all tweets sent on TTIP, as especially opponents also used the #stopTTIP and #noTTIP hashtags, but clearly illustrate how TTIP became a topic on Twitter (see the left pane of ). In fact, the development here is similar to the one shown in the right pane of . Again, we see that TTIP did not exist as a topic on Twitter prior to 2013. Especially from fall 2014 onwards, however, do we witness a large number of tweets on TTIP. What sets this figure apart from is the strong peak in May 2016, which was driven by Greenpeace's release of up to then secret TTIP negotiation documents.

Figure 4. Number of tweets using #TTIP as hashtag over time and mean sentiment.

Note: The trend line in the right pane is fit using LOESS.

For the right pane of , we analysed the sentiment of these tweets. We did so using the dictionary of positive and negative words produced by Hu and Liu (Citation2004), complemented by a few terms with important connotation for the TTIP debate (e.g., ‘corporate’ as negative because of complaints about ‘corporate power’), after implementing a standard pre-processing of the tweets (lower casing, removing numbers and URLs, etc.).Footnote8 What we show in the figure is the mean sentiment score of all TTIP tweets sent by month. As can be seen, the mean sentiment started out positive but then turned negative from late 2013 onwards. From mid-2014, it was consistently negative, with a single exception in November 2016. Together, the two graphs how TTIP became more salient and at the same time contested.

We operationalise our dependent variable as the percentage of an organisation's tweets per month that are on TTIP. Specifically, we divided the number of tweets on TTIP in a month by the overall number of the organisation's tweets in that month and multiplied the result by 100 (Percentage TTIP). Having organisation-month as unit of analysis has the advantage that this allows us to also make use of over-time variation in politicisation of TTIP.Footnote9 With few exceptions, these percentages are very small (Figure A3 in the Online Appendix shows the distribution of this variable). In fact, most actor-month percentages are zero, for both citizen groups (a bit less so) and business associations. Only 455 actors in our sample (so just less than half) ever sent a Tweet on TTIP across the 60-month period, which includes 289 business associations and 166 citizen groups. Among the few exceptions with a heavy focus on TTIP are the Seattle to Brussels Network, with 18 months in which 50 or more percent of tweets were on TTIP, Friends of the Earth Hungary, ATTAC Germany, but also Business Europe, and the American Chamber of Commerce in the EU.

As before, we need two predictors to test our hypothesis. On the one hand, we have the type of actor variable, which distinguishes between business associations and citizen groups. This is once more taken from the survey used in the previous section. On the other hand, we operationalise TTIP politicisation as having taken place in the same countries as indicated above, but only in the period after April 2014, where the left pane of shows a first peak in the Twitter debate and the right pane shows a consistently negative average sentiment (Politicised environment).Footnote10 The variation over time, which is also confirmed by data on protest events related to TTIP (Caiani & Graziano, Citation2018), is important as we have few groups from countries that exhibited little TTIP politicisation and thus relatively little cross-sectional variation. Overall, we consider 21,870 actor-months as politicised (58 per cent) and 15,986 actor-months as non-politicised (42 per cent). The proportions for business associations and citizen groups are similar.

In full models, we add four control variables. For one, this concerns a variable capturing the number of followers that an organisation has on Twitter. This variable is only an imperfect measure of a group's resources, but it does correlate with groups’ prominence, in the sense that Amnesty International has the largest number of followers in our sample whereas the European Packaged Ice Association is one of those with very few followers. Because of outliers, we take the natural logarithm of this variable (Follower count, log). Furthermore, we control for the (natural logarithm of the) number of tweets sent by an actor over the full period of analysis (Tweets sent (overall, log)). This is an indication of how important Twitter is for the group's activities. In addition, we include the number of tweets sent by a group in each specific month (Tweets sent (month, log)). This is potentially important as the smaller the number of tweets, the easier extreme values (either 0 or 100) on the dependent variable. Finally, we add year-fixed effects given the time trend that we saw in and . offers summary statistics for these variables.

Table 4. Summary statistics (Twitter analysis).

We again estimate the model using ordinary least squares regression. The main regression has the following form:

(3)

(3) where i is the individual group, t refers to the month, Ci is a vector of control variables,

are country fixed effects, and

is the error term. By including country fixed effects in all models, we reduce the comparison to variation within (rather than across) countries over time. This helps alleviate endogeneity concerns (see the discussion above) because if reverse causality was driving our results, we should see citizen groups in a country already focus on TTIP prior to politicisation, with the aim of increasing the salience of the topic. In other words, given our set-up, endogeneity should work to reduce the effects of the interaction term. To the extent that the interaction is sizeable, concerns about endogeneity will be alleviated. Given that the same organisations appear several times in the dataset, we cluster standard errors by organisation. In view of the right-skewed distribution of the dependent variable (see Figure A3 in the Appendix), we also ran models after taking its natural log, but without this changing the substantive results. For ease of interpretation, we thus report the models in which we retained the natural scale of the dependent variable.

presents the results from these models. The findings are in many ways similar to those shown in . In Model 4, Politicised environment has a positive and statistically significant coefficient, indicating relatively more tweets on TTIP from citizen groups in countries and time periods of high politicisation. The coefficient for Business association is negative, but not statistically significant. The negative and statistically significant coefficient for the interaction between these two variables means that the difference between citizen groups and business associations increases in a politicised environment.

Table 5. Regression analysis of Twitter data.

shows the effect of the interaction graphically. As can be seen, the share of tweets on TTIP increases for both citizen groups and business associations in a politicised environment. This increase is substantially larger for the former than the latter, however, augmenting the difference between the two types of actors. While this finding supports the hypothesis in the sense that lobbying strategies vary more across group types in a politicised environment, we do not see business associations hiding from the public eye as expected in the causal mechanism, but citizen groups seeking the limelight. The effect size that we show may seem small, as we are talking about single digit percentages of tweets sent on TTIP. Actually, however, it is impressive, as the difference between business associations and citizen groups in the politicised environment is around seven times as large as in the non-politicised environment.

Figure 5. Politicised environment × Business association (Twitter data).

Note: The figure is based on the results reported in Model 4 in . The whiskers indicate the 90% confidence intervals.

In Figure A4 in the Online Appendix, we provide results from a sentiment analysis of these tweets (carried out as described for above), which demonstrate the stark differences in sentiment between business associations and citizen groups. This disparity is also witnessed by the fact that only 19 tweets sent by business associations contained the ‘#StopTTIP’ hashtag, as compared to 1,825 tweets sent by citizen groups. This supports the causal mechanism set out above, which focuses on how citizen groups reflect (and of course also reinforce) the (negative) sentiment by the public once the agreement got politicised, whereas business associations found their preferences to be far away from public opinion in the countries in which the agreement got contested.

Model 5 in confirms that these findings are robust to controlling for other potential influences on the dependent variable. The coefficient for the interaction term remains negative and statistically significant. Two of the control variables, namely Tweets sent (overall, log) and Tweets sent (month, log), are statistically significant in this model. The former coefficient is positive, indicating that groups sending more tweets also exhibit a greater focus on TTIP, while the latter is negative, meaning that more tweets per month negatively correlates with a focus on TTIP.

We conducted three robustness checks for this analysis. For one, we excluded all groups that never tweeted on TTIP from the analysis (see Models 6 and 7 in ). Doing so only marginally changes the results, but the expected effect of the interaction term is a bit larger than in Models 4 and 5. Moreover, in Models 8 and 9 in we excluded all retweets from the analysis. That is, both the Percentage TTIP and the Tweets sent (month, log) variables are calculated omitting retweets. Retweets may not be as strong a signal of one's stance as original tweets. The findings, however, do not change substantively. Finally, we again ran a jackknife test, dropping one country at a time. In no case does this affect our substantive findings (see Figure A5 in the Appendix). Overall, the results from our analysis of Twitter data confirm those reported above based on survey evidence.

Conclusion

While many trade policy decisions experience little public attention, some trade negotiations or agreements become highly politicised. How does this politicisation affect the lobbying strategies of interest groups trying to influence policymaking? We have argued that politicisation exacerbates the differences in lobbying style between business associations, who mostly support the trade agreements under scrutiny, and citizen groups, who tend to oppose them. Concretely, citizen groups should be pushed in the direction of more outside lobbying, whereas business associations should face incentives to rely more strongly on inside lobbying.

We have carried out two empirical tests of the argument, uniquely combining survey and Twitter data. On the one hand, a survey of interest groups allowed us to assess the relative focus on outside and inside lobbying on politicised and non-politicised trade agreements. On the other hand, using Twitter data we investigated to which extent interest groups changed their relative focus on TTIP as this agreement became politicised. Although these two empirical tests rely on distinct data sources, both supported our key argument. Contrary to what we expected in our causal reasoning, however, the greater differences in lobbying strategies in the context of politicisation emerge less because of a move of business associations towards inside lobbying and more because of a strong move of citizen groups towards outside lobbying.

These findings fill a gap in our understanding of the politics of trade in the presence of politicisation (De Bièvre & Poletti, Citation2020). They indicate that once citizen groups start contesting a trade agreement, the process can feed upon itself, making it very difficult for business actors to regain control of the debate. In fact, business voices may get lost in the public sphere. There is also evidence that this process was at work not only in the cases studied here. In the debate on British exit from the EU, for example, the British business community also was less vocal than one would expect given its resources and the stakes at hand. This finding is important as on topics of high public salience, public opinion (which in turn may reflect outside lobbying) is likely a greater determinant of policy outcomes than inside lobbying (Culpepper, Citation2011). Still, it does not necessarily mean business defeat: while (much of) business lost with respect to TTIP, provisionally key parts of CETA have entered into force, as preferred by many business actors across Europe.

The results also add to research on interest group strategies (Dür & Mateo, Citation2016; Hanegraaff et al., Citation2016), showing how the difference in lobbying styles across different types of interest groups is not only conditional on the resources these groups have and the type of policy under consideration, but also the extent to which the policy is publicly contested. Testing our hypothesis using both survey and Twitter data also may indicate a methodological way forward for this literature, which has used both data sources but generally without combining them in a single study.

Future research might rely on a survey experiment with interest groups to further scrutinise our argument. It might also be possible to trace the change in lobbying strategy for individual groups as a trade policy decision becomes politicised. Finally, whereas here we have focused on business associations and citizen groups, future research might also study the strategies of other actors, especially firms. This paper thus is only a first step toward a better understanding of lobbying in the face of politicisation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (68.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Teodora Pavkovic for valuable research assistance and Dirk De Bièvre, Scott Hamilton and two anonymous reviewers for useful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Data availability statement

Full replication materials can be downloaded from the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NDHWMU.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The survey was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Salzburg (approval number 45/2016).

2 The exact wording of the question was: ‘Which trade agreement/negotiation has your organization been most active on (in the sense of monitoring it, trying to influence its negotiation or implementation etc.)? Please only indicate one.’

3 ‘In your efforts to influence the trade agreement/trade negotiations just mentioned, how important are the following activities for your organization?’

4 Several of the other negotiations/agreements mentioned are high-profile (e.g. the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement), but they are not contested in the sense that there is no set of actors trying to foster public opposition to them. They thus do not fit our definition of politicised.

5 and

hence are vectors of coefficients.

6 In the presence of interactions, the coefficients for the group types need to be interpreted for the case when Politicised environment takes on the value of 0, that is, the lobbying takes place in a non-politicised environment.

7 We downloaded the tweets using the academictwitteR R package (Barrie & Chun-ting Ho, Citation2021).

8 We exclude all non-English tweets from this analysis, as each language would require its own sentiment analysis.

9 We decided to omit months in which a group does not tweet at all, rather than setting all of these months to zero with respect to the shares variable.

10 Politicization may have started at different times in different countries. Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to determine individual starting points by country. Our results, however, are highly robust when moving the starting point two months back or two months forward (see Table A3 in the online appendix).

References

- Aaronson, S. A. (2001). Taking trade to the streets: The lost history of public efforts to shape globalization. University of Michigan Press.

- Barrie, C., & Chun-ting Ho, J. (2021). academictwitteR: An R package to access the Twitter academic research product track v2 API endpoint. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(62), 32–72. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03272

- Bauer, M. (2016). Manufacturing discontent: The rise to power of anti-TTIP groups, ECIPE Occasional Paper No. 02/2016.

- Bauer, R. A., De Sola Pool, I., & Lewis, A. D. (1972). American business and public policy: The politics of foreign trade. Atherton Press.

- Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D. C., Leech, B. L. (2009). Lobbying and policy change: Who wins, who loses, and why. University of Chicago Press.

- Berry, J. (1999). The new liberalism: The rising power of citizen groups. Brookings Institution.

- Beyers, J. (2004). Voice and access: Political practices of European interest associations. European Union Politics, 5(2), 211–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116504042442

- Caiani, M., & Graziano, P. (2018). Europeanisation and social movements: The case of the Stop TTIP campaign. European Journal of Political Research, 57(4), 1031–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12265

- Chalmers, A. W. (2013). Trading information for access: Informational lobbying strategies and interest group access to the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.693411

- Chalmers, A. W., & Shotton, P. A. (2016). Changing the face of advocacy? Explaining interest organizations’ use of social media strategies. Political Communication, 33(3), 374–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1043477

- Conrad, M., & Oleart, A. (2020). Framing TTIP in the wake of the Greenpeace leaks: Agonistic and deliberative perspectives on frame resonance and communicative power. Journal of European Integration, 42(4), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1658754

- Culpepper, P. D. (2011). Quiet politics and business power: Corporate control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- De Bièvre, D., Dür, A., & Hamilton, S. (in press). Reacting to the politicization of trade policy. Journal of European Public Policy.

- De Bièvre, D., & Poletti, A. (2020). Towards explaining varying degrees of politicization of EU trade agreement negotiations. Politics and Governance, 8(1), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i1.2686

- De Vries, C. E., Hobolt, S. B., & Walter, S. (2021). Politicizing international cooperation: The mass public, political entrepreneurs, and political opportunity structures. International Organization, 75(2), 306–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000491

- Duina, F. (2019). Why the excitement? Values, identities, and the politicization of EU trade policy with North America. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(12), 1866–1882. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1678056

- Dür, A. (2010). Protection for exporters: Power and discrimination in transatlantic trade relations, 1930-2010. Cornell University Press.

- Dür, A. (2019). How interest groups influence public opinion: Arguments matter more than the sources. European Journal of Political Research, 58(2), 514–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12298

- Dür, A., & De Bièvre, D. (2007). Inclusion without influence? NGOs in European trade policy. Journal of Public Policy, 27(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X0700061X

- Dür, A., & Lechner, L. (2015). Business interests and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. In J. Morin, T. Novotná, F. Ponjaert, & M. Telò (Eds.), The politics of transatlantic trade negotiations: TTIP in a globalized world (pp. 69–80). Ashgate.

- Dür, A., & Mateo, G. (2014). Public opinion and interest group influence: How citizen groups derailed the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(8), 1199–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.900893

- Dür, A., & Mateo, G. (2016). Insiders versus outsiders: Interest group politics in multilevel Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Dür, A., Mateo, G., & Anderer, C. (2019). Trade negotiation survey: Key findings, Unpublished report. http://tradepower.sbg.ac.at/survey_report.html.

- Eliasson, L. J., & Garcia-Duran Huet, P. (2018). TTIP negotiations: Interest groups, anti-TTIP civil society campaigns and public opinion. Journal of Transatlantic Studies, 16(2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794012.2018.1450069

- European Commission. (2015). Public opinion in the European Union, Standard Eurobarometer 83 (Spring). Brussels: Eurobarometer.

- European Commission. (2017). Public opinion in the European Union, Standard Eurobarometer 86 (Autumn 2016). Brussels: Eurobarometer.

- Gheyle, N., & De Ville, F. (2019). Outside lobbying and the politicization of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. In D. Dialer, & M. Richter (Eds.), Lobbying in the European Union: Strategies, dynamics and trends (pp. 339–354). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98800-9_24. (December 19, 2018).

- Hamilton, S. (in press). Dropping off the bandwagon: A puzzle for the resource mobilization perspective on civil society contestation networks. Journal of European Public Policy.

- Hanegraaff, M., Beyers, J., & De Bruycker, I. (2016). Balancing inside and outside lobbying: The political strategies of lobbyists at global diplomatic conferences. European Journal of Political Research, 55(3), 568–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12145

- Hathaway, O. A. (1998). Positive feedback: The impact of trade liberalization on industry demands for protection. International Organization, 52(3), 575–612. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550662

- Holzer, B. (2010). Moralizing the corporation: Transnational activism and corporate accountability. Edward Elgar.

- Hu, M., & Liu, B. (2004). Mining and summarizing customer reviews. Proceedings of the Tenth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pp. 168–177.

- Hübner, K., Deman, A., & Balik, T. (2017). EU and trade policy-making: The contentious case of CETA. Journal of European Integration, 39(7), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2017.1371708

- Hurrelmann, A., & Wendler, F. (in press). How does politicisation affect the ratification of “mixed” EU trade agreements? The case of CETA. Journal of European Public Policy.doi:10.1080/13501763.2023.2202196.

- Jarman, H. (2008). The other side of the coin: Knowledge, NGOs and EU trade policy. Politics, 28(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2007.00307.x

- Junk, W. M. (2016). Two logics of NGO advocacy: Understanding inside and outside lobbying on EU environmental policies. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(2), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1041416

- Kay, T., & Evans, R. L. (2018). Trade battles: Activism and the politicization of international trade policy. Oxford University Press.

- Keck, M. E., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. Cornell University Press.

- Kollman, K. (1998). Outside lobbying: Public opinion and interest group strategies. Princeton University Press.

- Kriesi, H., Tresch, A., & Jochum, M. (2007). Going public in the European Union. Comparative Political Studies, 40(1), 48–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414005285753

- Massicotte, P., & Eddelbuettel, D. (2022). GtrendsR: R Package.

- Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The spiral of silence: A theory of public opinion. Journal of Communication, 24(2), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1935). Politics, pressures, and the tariff: A study of free private enterprise in pressure politics, as shown in the 1929-1930 revision of the tariff. Prentice Hall.

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semisovereign people. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Schlozman, K. L., & Tierney, J. T. (1986). Organized interests and American democracy. Harper & Row.

- Stop TTIP. (2015a). ECI is closed – signature gathering continues.

- Stop TTIP. (2015b). ECI partner list.

- Weiler, F., & Brändli, M. (2015). Inside vs. outside lobbying: How the institutional framework shapes the lobbying behavior of interest groups. European Journal of Political Research, 54(4), 745–766. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12106

- Willems, E. (2022). No escape from the media gates? How public support and issue salience shape interest groups’ media prominence. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 10776990221124942. doi:10.1177/10776990221124942.

- Young, A. R. (2016). Not your parents’ trade politics: The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership negotiations. Review of International Political Economy, 23(3), 345–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1150316

- Zürn, M., Binder, M., & Ecker-Ehrhardt, M. (2012). International authority and its politicization. International Theory, 4(1), 69–106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971912000012