ABSTRACT

Theorists of the transnational cleavage, defined as a political reaction against European integration and immigration, also regularly conceptualise international trade preferences as a component of this contemporary societal divide. Yet empirical analyses of this cleavage focus on the former two topics, while trade and the transnational cleavage has not been systematically investigated. Making use of a new item in the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey that measures party support for protection of domestic producer groups versus support for trade liberalisation, we examine the applicability of explanations for European integration positioning for the topic of trade. The results show that party positions on international trade correlate with parties’ underlying two-dimensional ideology: parties of the economic left and culturally conservative parties support trade protection. The findings advance previous studies on the transnational cleavage and party positioning on trade, and demonstrate the continued importance of economic factors in driving patterns of trade protection.

Introduction

In the World Trade Organization’s annual report (Citation2020, p. 108), Director-General Roberto Azevêdo maintained: ‘Historically high levels of trade-restrictive measures are hurting growth, job creation and purchasing power around the world’. Even more recently, the leaders of several prominent radical right parties in Europe, such as Marine le Pen in France and Giorgia Meloni in Italy, have mobilised on protection of domestic producer groups (Startin, Citation2022, pp. 433–434; Zulianello, Citation2022), attempting to take ownership of a form of economic nationalism (Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018, Citation2019). Thus, after decades of running trade in relative quiet, the mid-2010s has seen a sharp rise in contestation of economic globalisation (see Dür, et al., Citation2023). In a recent article, Walter argues that ‘[t]o understand the increasing contestation and politicization of globalization-related issues, we need to look at the supply side of politics’ (Walter, Citation2021, p. 426). We follow this and related calls (see, e.g., De Vries et al., Citation2021) by focusing on the role of political parties in understanding how the contestation and politicisation of international cooperation unfolds in the field of trade.

We account for varying patterns of party positioning on trade protection versus liberalisation using an ideological cleavage perspective (Bartolini & Mair, Citation2007; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018; Lipset & Rokkan, Citation1967), rooted in an understanding of international cooperation contestation driven by ideologically extreme challenger parties (De Vries & Hobolt, Citation2020). Theorists of the transnational cleavage in contemporary European societies see trade preferences as an important component of this transnational divide:

The perforation of national states by immigration, integration and trade may signify a critical juncture in the political development of Europe no less decisive for parties and party systems than the previous junctures that Lipset and Rokkan (Citation1967) detect in their classic article. (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018, p. 109)

We depart from and complement work on the transnational cleavage by explicitly focusing on the positions of political parties in Europe on the issue area of trade liberalisation versus trade protection, which allows us to more rigorously explore a component of the transnational cleavage in contemporary Europe. Core insights from the theorists of the transnational cleavage are that party positioning on questions of European integration and immigration are rooted in parties’ broader ideological profiles. We extend a similar logic to party positioning on international trade via the multidimensional framework that has been used to explain positions on European integration (De Vries & Edwards, Citation2009; Hooghe et al., Citation2002; Hutter et al., Citation2016). Our argument emphasises the foundations of opposition to trade in economic left extremity and in cultural conservatism, the latter measured by the GAL-TAN (Green, Alternative, Libertarian – Traditional, Authoritarian, Nationalist) dimension. Focusing on the supply side of political party offerings answers recent calls for party-based explanations of politicisation of international cooperation and is central to the organisational component of cleavage theory (Bartolini & Mair, Citation2007). By doing so, we shed further light on the centrality of parties’ core ideology in their positioning on trade protection, and build on recent theoretical insights that highlight the political entrepreneurial strategies of challenger parties to understand the contestation of international cooperation (De Vries et al., Citation2021).

Our article further aims to facilitate the convergence of literatures on multidimensional party competition and international political economy (IPE), with a specific emphasis on the politics of trade. While the latter increasingly incorporates the supply of party positions in theories and empirical analyses of the backlash against globalisation (e.g., Bisbee et al., Citation2020; Burgoon & Schakel, Citation2022; Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018, Citation2019; Walter, Citation2021), there remains an emphasis on voter demand rather than party supply. Much of both literatures concentrates on radical right parties at the expense of other party families, and relatively few studies in both subfields examine the underlying ideological foundations for party positioning on international trade, rather than broader measures of globalisation or the transnational cleavage.

Making use of a new and underexplored item in the most recent wave of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) on party positioning in Europe for the year 2019, we show that party positions on the question of trade liberalisation versus protection follow a broadly similar pattern to European integration: while centre-right, centre-left and liberal parties largely embrace trade liberalisation, radical left and radical right parties are less enthusiastic about the liberalisation of trade, albeit for different reasons. Parties towards the left fringe are driven mainly by economic ideology, while parties to the very right are driven by cultural concerns.

Our findings highlight important similarities and differences between party positioning on European integration and trade. As expected, the economic and cultural ideologies of political parties are relevant for party positioning on both trade and the question of European integration, but parties’ economic ideology is strongly connected with positioning on trade, whereas the cultural ideology of a party has become more strongly associated with positions on the European Union (EU) (Jolly et al., Citation2022). This illustrates that the transnational cleavage, while strongly associated with the GAL-TAN dimension, encompasses more than cultural politics, that there is also an important economic core to this cleavage (De Vries, Citation2018). The strong correlation between the economic ideology of a party and positioning on trade emphasises the enduring relevance of distributional competition for the transnational cleavage in Europe, and invites more direct engagement from scholars of political economy in examining the transnational divide in contemporary European societies.

Political parties and the politics of trade

Although trade liberalisation increases economic growth on average, certain groups are more exposed to higher levels of competition from abroad and therefore stand a greater risk of lower wages or losing their jobs (Rommel & Walter, Citation2018). Thus, international trade is held to be a central part of societal changes that pit winners of globalisation against losers (e.g., Kriesi et al., Citation2012), and European politics has been transformed by this increasing contestation of globalisation (but see also, Langsæther & Stubager, Citation2019). International cooperation and integration have challenged national sovereignty, increased migration, and promoted economic liberalisation, leading to conflict over globalisation (Kriesi et al., Citation2006, Citation2008; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019). One version of this argument uses the terms ‘cosmopolitans’ against ‘communitarians’ (De Wilde et al., Citation2019, p. 3); those who support open borders against those who prefer them closed, universal norms versus cultural particularism and the acceptance of supranational authority against defense of the nation state (ibid.). The rise of the transnational cleavage is a response to how these reforms have shaped political and economic developments at the expense of the cultural and economic security of distinct groups of European citizens (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018, p. 110). This new cleavage has been conceptualised in various ways, but there are three core components driving conflict: immigration, integration, and trade (De Vries, Citation2018; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018; Kriesi et al., Citation2008).

The emphasis in the transnational cleavage literature has been on the increasing salience and intertwining of immigration and European integration for political competition; this body of scholarship is party-based and particularly attentive to cultural politics (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018; Jackson & Jolly, Citation2021; Treib, Citation2021). These processes can be seen as an example of a broader politicisation of globalisation or denationalisation (Colantone & Stanig, Citation2019; De Wilde et al., Citation2019; Kriesi et al., Citation2006, Citation2008; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019; Trubowitz & Burgoon, Citation2022; Walter, Citation2021; Zürn & De Wilde, Citation2016). While much of the analysis related to the transnational cleavage in Europe examines cultural politics (De Vries' (Citation2018) study of the Netherlands is a prominent exception), the liberalisation of trade policy is also a key aspect of the European integration project as well as globalisation more generally.

Indeed, in international political economy (IPE), a similarly large body of work, focuses on the effects of globalisation, and a main preoccupation in this literature has been to theorise the distributional effects of trade as well as its political consequences. Traditional models have tended to focus either on sectoral exposure to trade competition or on skill-set as the main determinant of preferences about economic globalisation (e.g., Gourevitch, Citation1986; Rogowski, Citation1989). Later developments of trade theory refined the assumptions of both sector and factor-based conflict, differentiating between, for instance, tradeable and non-tradeable sectors (e.g., Hays et al., Citation2005; Jensen et al., Citation2017), the competitiveness of firms (e.g., Melitz, Citation2003) or institutional conditions (e.g., Baccini et al., Citation2022). Yet the emphasis within the IPE literature still tends to be on citizen demand or country-level differences, emphasising the economic dimension.

As the purpose of our article is to examine how parties position themselves on the trade component of the transnational divide, we draw upon both bodies of work to inform our expectations of how distributional as well as broader societal effects of globalisation may contribute to the patterns of trade protection among European parties. More specifically, we argue that the ideological correlates of party positioning on European integration correspond to party positions in the more specific issue area of trade liberalisation versus protection of domestic producers.

We build from the well-documented evidence that party positioning on European integration requires a multidimensional framework in order to understand opposition to the European Union (EU) (Braun et al., Citation2019; Hooghe et al., Citation2002; McElroy & Benoit, Citation2012; Rovny & Edwards, Citation2012). Parties that oppose European integration on economic grounds tend to come from the far left, while cultural opposition to the EU is concentrated in the ‘new right’ which espouses a traditional, authoritarian, and nationalist ideology (De Vries & Edwards, Citation2009). This stands in contrast to the majority of centre-left, centre-right, and liberal parties that tend to take a positive stance towards the EU.

Voters for the radical left and radical right party families differ in fundamental respects related to comparable differences between mainstream left and right supporters. Still, these radical party voters (left and right) often come from similar social strata, and the party families share aspects of nationalism, Euroscepticism, and populism (Rooduijn et al., Citation2017, p. 537). This is consistent with the idea that the economic, cultural, and institutional factors related to public discontent with international cooperation should not be treated in isolation. It further aligns with the growing number of contributions from political economy that link the rise of radical right and radical left parties and anti-globalisation backlash to the combination of both economic and cultural factors (Burgoon & Schakel, Citation2022; Colantone & Stanig, Citation2019; Trubowitz & Burgoon, Citation2022; Walter, Citation2021). Additionally, research on individual trade preference formation increasingly incorporates cultural, ideational and psychological factors to explain variation in attitudes towards trade (e.g., Ehrlich & Maestas, Citation2010; Hainmueller & Hiscox Citation2006; Mansfield & Mutz, Citation2009; Margalit, Citation2012).

People tend to view international cooperation as a ‘package of openness’ that encompasses both economic and non-economic aspects, which ‘provides political entrepreneurs with some flexibility in choosing how to frame the threats of international cooperation and to focus on those elements that are more salient for voters’ (De Vries et al., Citation2021, p. 315). Following the template of party-based opposition to European integration, we supplement the demand-side focus in much of the IPE literature by incorporating this emphasis on political entrepreneurship, in the form of far left and far right challenger parties, and the idea that their patterns of opposition to trade are multidimensional.

Political parties located toward the extreme left of the economic left-right dimension will be opposed to trade liberalisation. These parties remain critical of capitalism and see trade liberalisation as part of a larger deregulatory framework anathema to their core ideology (Braun et al., Citation2019; March & Mudde, Citation2005). In addition, low-skilled workers remain a core constituency for radical left parties, who look to the left for protection from economic globalisation (Walter, Citation2010). Dancygier and Walter (Citation2015, p. 23), for instance, report that they ‘consistently find that skill remains a significant determinant of preferences about the globalization of labor’. Whether they belong to tradable or non-tradable sectors, low-skilled workers are more often adversely affected by trade liberalisation, compared to high-skilled (Rommel & Walter, Citation2018).

Even amidst the constraints of globalisation pressures, we anticipate enduring differences between the trade positions of parties based on their economic left-right ideology. According to Milner and Judkins, while parties of the left have tended to be more pro-protection, ‘[i]ncreasing exposure to international markets makes all parties, regardless of their partisan location, less favorable to protectionism’ (Citation2004, p. 114), a finding in line with the neoliberal convergence argument that globalisation reduces differences between mainstream left and right parties (Haupt, Citation2010; Huber et al., Citation2001). Yet others highlight the importance of left-right ideological differences in understanding the resilience of national autonomy in the global economy (Garrett, Citation1998), and emphasise the relevance of partisan differences for particular types of policy responses to globalisation (Engler, Citation2021). Independent of ideological commitment, radical left economic parties have potential electoral incentives to play up their anti-trade positions (De Vries et al., Citation2021). If centre-left parties take trade liberalising positions, this could be perceived as a move to the political centre at the expense of left-wing supporters and allow left challenger parties to more clearly differentiate themselves from mainstream social democratic parties (Allen, Citation2009; Arndt, Citation2013; Karreth et al., Citation2013). We therefore hypothesise that:

H1: Parties towards the left pole of the economic left-right dimension are more pro-protection than other parties.

Two dimensional models of party competition have become increasingly common in analyses of European politics, concurrent with widespread recognition that party stances on the cultural dimension have ramifications for questions of substantial economic import, such as European integration (see, e.g., Beramendi et al., Citation2015; De Vries & Marks, Citation2012). We know that both radical right and radical left parties tend to be more anti-globalisation than their mainstream counterparts and that these differences are particularly pronounced for GAL-TAN-related topics like immigration and the EU (Burgoon & Schakel, Citation2022). And while it is not entirely clear to what extent trade protection should be equated with nationalism (see Donnelly, Citation2023 on this point), some highlight nationalism as a common factor in the Eurosceptic stances of both the radical right and radical left party families (Halikiopoulou et al., Citation2012). Moreover, in theorising the emergence of the transnational cleavage, often associated with cultural politics, scholars frequently include the question of international trade as a component of the concept (De Vries, Citation2018, p. 1541; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018, p. 109; Jackson & Jolly, Citation2021, pp. 318–319).

In one of the few studies to disaggregate globalisation into its constituent parts, globalisation, especially in the form of trade, was associated with growing vote shares for radical right parties in Western Europe from 1990 to 2018 (Milner, Citation2021). This suggests that the politicisation of trade is ‘good politics’ from the perspective of the radical right. Turning to the policies on offer, a recent overview of the economic supply of five European populist radical right parties emphasises a shared mix of economic populism and sovereigntism (Ivaldi & Mazzoleni, Citation2020). These authors show that while some populist radical right parties such as the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and Swiss People’s Party espouse trade liberalising positions, the three radical right parties that they analyse within the European Union (FN in France, FPÖ in Austrian, and the League in Italy) consistently oppose free trade and multilateral trade agreements like the Transnational Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and EU–Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) (ibid). In addition, analysis of the election manifestos of seven right wing populist parties in Western Europe between 2005 and 2015 reports ‘a unified “nativist” response to the global financial crisis both in terms of welfare chauvinism and economic protectionism’ (Otjes et al., Citation2018). Building from this logic we posit that protection for domestic producers and workers rather than a preference for trade liberalisation is an expression of economic nationalism (Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018, Citation2019). We thus hypothesise that:

H2: Parties towards the Traditional/Authoritarian/Nationalist pole of the cultural dimension are more pro-protection than other parties.

In general, we expect differences between ideologically centrist and extreme parties, similar to the patterns in party positioning on the EU. Ideology is not the only factor that might account for differences in positioning on international trade, however. Larger parties (in terms of vote share) and governing parties, in particular, must navigate between responsible policy and ideological principles (Bardi et al., Citation2014; Mair, Citation2009). Budgetary constraints and balancing between different priorities contribute to moderation among incumbents. Opposition parties are freer to operate with absolutes, particularly those with little to no governing experience (De Vries & Hobolt, Citation2020; Van de Wardt et al., Citation2014). In the case of trade, international agreements, and EU membership especially, entail additional restraints on policy alternatives. Kinski, Citation2018, for example, showed how governing status affected the rhetoric of national parliamentarians during the Euro crisis. MPs from parties with governing responsibilities were more likely to take into account the interests of other European countries. Her findings echo other studies that underline how interdependencies affect governing parties more than the opposition (Bardi et al., Citation2014; Rose, Citation2014).

The electoral size of a party should also be of relevance to its positioning on trade, as shown in previous studies (Milner & Judkins, Citation2004). First, other things being equal, larger parties are more likely to be included in governing coalitions and thus face the pressures described in the preceding paragraph. But whether in or outside of the government, bigger parties almost by definition must manage larger and more diverse electoral constituencies, cutting across different industries and occupations, forcing trade-offs between the support base of mainstream parties. When considering not only the tactical response to challenger party competitors, but also the economic context, choosing a path of protection is not straightforward for large, mainstream parties. Raising tariffs (or more often introducing other non-tariff barriers to trade) might protect domestic manufacturers, but companies and their employees who rely on export or are part of larger global value chains are likely to suffer. This is a dilemma that mass political parties have to face, with the tendency to push larger parties to less autarkic trade positions.

Case, data and methods

Trade is an exclusive EU competence, which raises the question if the positions of domestic political parties are of relevance to trade politics? We believe that they are. First, the high level of supranational integration on trade should amplify the relevance of the ideological correlates regarding parties’ positioning on European integration, given the well-documented relationship between economic left extremity or culturally TAN extremity and opposition to European integration. Second, even though the Commission sets the agenda on trade for the EU, a primary role of the Commission is also to understand what is politically feasible for the EU (Hooghe, Citation2012), which necessitates an awareness of domestic politics within the member states. Moreover, the Council must both sign off on any trade agreements made by the Commission and also closely surveils the Commission through the Trade Policy Committee. Finally, there are several examples of domestic contestation having an impact on the trade policy making processes in Brussels, not only in the context of negotiating free trade agreements, but also more recently on legislation on trade protective measures such as screening of foreign direct investment (e.g., Chan & Meunier, Citation2022).

To investigate the politics of trade liberalisation and protection among European political parties, we use data from the latest Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) (Jolly et al., Citation2022). The CHES surveys estimate the positions of political party leadership across Europe, and increasingly other regions of the world (Martínez-Gallardo et al., Citation2022; Struthers et al., Citation2020). The core of CHES focuses on Europe and party positions on European integration, major dimensions of party competition, such as economic left-right and a cultural dimension referred to as GAL-TAN, and more specific policy issues, such as party stances on international trade, which we use in this article.

Central variables in the CHES data have been subjected to extensive reliability and validity tests (Bakker et al., Citation2015; Hooghe et al., Citation2010; Polk et al., Citation2017), and the data are now widely used by scholars of European integration, party competition, and representation. The 2019 wave of CHES that we use includes 421 political scientists, experts in political parties and/or European integration. It was fielded in the winter/spring of 2020 and provides information about the positioning of 277 parties across 32 European countries, where we focus on the EU members, including United Kingdom which was still a member at the time the survey was conducted.

Several studies that have investigated the partisan politics of trade and globalisation use manifesto data to identify party positions (e.g., Burgoon, Citation2012; Lacewell, Citation2017; Milner & Judkins, Citation2004). Many of these also use measures of parties’ anti-globalisation stances that go beyond trade. In one recent article, Burgoon and Schakel (Citation2022) demonstrate how what they call anti-globalisation nationalism has increased over time. However, their measure of anti-globalisation nationalism encompasses several aspects of globalisation, including attitudes toward the EU, international cooperation in general, patriotism, multiculturalism and protectionism. In this paper, we zoom in on the specifics of economic globalisation, others having shown that this is distinct from broader measures of globalisation (Mader et al., Citation2020). Here, we follow those that suggest that if recent trends in nationalism have a large economic component (cf. Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018, Citation2019), then trade plays a prominent part. Protection of domestic actors versus trade liberalisation is at the centre of this debate.

The information we have about the trade policy preferences of political parties is heavily dependent on data from the Manifesto Research on Political Representation (MARPOR) project, which provides coded party programmes across parties in most European countries (Volkens et al., Citation2019). Despite the documented value of manifesto-based data on party positions (McDonald et al., Citation2007; Volkens, Citation2007), the information it provides is necessarily limited to what parties choose to say about a topic in manifestos (Benoit & Laver, Citation2006, Citation2007; Marks et al., Citation2007). Issue competition models of party politics expect political parties to emphasise topics that highlight their electoral strengths and to minimise attention to issues that divide their electorate (De Sio & Weber, Citation2014; Green-Pedersen, Citation2019; Pinggera, Citation2021). Much like European integration (cf. Green-Pedersen, Citation2012), the question of trade protectionism/liberalisation also generates tensions within mainstream parties (see, e.g., Oesch & Rennwald, Citation2018). Previous studies have shown that some parties, and social democrats in particular, tend to obscure their position on trade in manifestos (Lacewell, Citation2017). If parties choose not to speak about their position in trade policy or emphasise only some aspect of it, we may not be getting the full picture on party positioning for trade policy. To illustrate the challenge, for 36 mainstream parties across 17 European democracies, the average manifesto included just 0.67 per cent of its text to statements related to trade/protection (Honeker, Citation2022, p. 16).

While expert surveys have their own limitations (McDonald et al., Citation2007; Volkens, Citation2007), their flexibility, both temporal and substantive, make them an attractive option for the purposes of this article. As long as researchers can identify a sufficiently large stock of respondents with expertise in the topic and willingness to answer questions, expert surveys can productively probe party positions on such internally divisive topics. Thus, the CHES provides a promising complementary path to investigating the patterns of trade protection among European parties.

Party positions on trade protection vs. liberalisation

Our outcome variable is taken from the 2019 CHES dataset and is called protectionism, which is measured on a scale from 0 to 10, denoting the extent to which parties favour trade liberalisation or protection of domestic producers. 0 indicates the position most in support of trade liberalisation, while 10 corresponds to the strongest support for the protection of domestic producers.

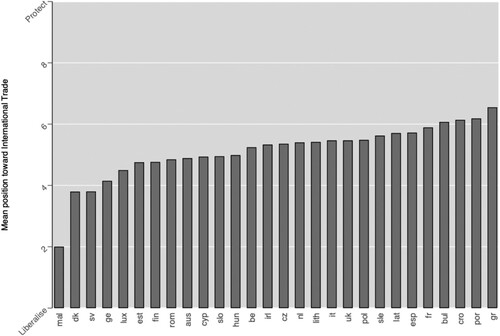

shows the mean position of parties on international trade at the country level, measured on the scale from strongly favours trade liberalisation (0) to strongly favours protection of domestic producers (10). The mean across all countries is 5.2. We include this figure because analysts highlight the presence of large differences between countries, with some more heavily reliant on foreign trade than others. In the words of Baccini et al. (Citation2022, p. 2): ‘While in some countries popular concerns over the welfare effects of trade liberalization are widespread and have generated marked protectionist responses from elected representatives, in other countries the opposition to trade liberalization has been much less intense’. Among the countries that are on the trade liberalising side of the scale, we find countries with open economies, such as Luxembourg, Denmark and Cyprus.Footnote2 At the other side of the scale, we find countries that score lower on trade openness, for example France, Spain and Greece. However, there are also free traders among those who score above the mean, such as the Netherlands and Belgium, but also Latvia and Lithuania. Without exaggerating the differences between these countries, points to a need to also look within countries to account for the variation. As we discuss in more detail below, our modelling strategy allows us to examine the impact of political party ideological positions both across and within countries, which facilitates more careful analysis of country-level differences.

Figure 1. Party positioning on international trade, country means.

Note: Political party positions on trade protection in the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey data. 0 = strongly favours trade liberalisation; 10 = strongly favours domestic producers.

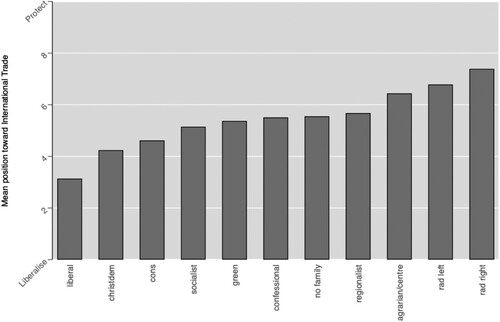

In , we present the variable organised by the party family categories included in the CHES data, organised from the most pro-liberalisation party family to the most pro-protection.Footnote3

Figure 2. Party positions on trade protection in Europe, party family means.

Note: Political party positions on trade protection in the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey data. 0 = strongly favours trade liberalisation; 10 = strongly favours domestic producers.

visualises several relevant pieces of information. First, the distribution of party families on this question largely corresponds with expectations. For example, the Liberals are the party family that most clearly favours trade liberalisation, which is consistent with the ideological perspective of this group of parties. Agrarian parties are amongst the most protectionist parties, which is in line the with a sector model approach to trade. In Europe, many agrarian parties will represent farmers wary of import competition, who are more likely to demand protection (Thies & Porche, Citation2007). Moreover, the Radical Right is the most protectionist of the party families, as expected, more strongly opposed to trade liberalisation than even the Radical Left, which is in line with the implications of our two hypotheses.

Turning to the major mainstream party families, the Conservatives, Christian Democrats, and Social Democrats all fall between the extremes of the Liberals and Radical Right, but are also all located on the pro-trade liberalisation side of the scale. Consistent with the findings of Milner and Judkins (Citation2004), the central tendency of the Social Democrat party family is more protectionist than is the case for the parties of the mainstream right, but these differences are rather small, which provides support for the idea that the differences between the mainstream right and left on trade are not substantial (e.g., Haupt, Citation2010). Taken together, provides evidence that the CHES protectionism question captures meaningful variation in party positions on trade liberalisation, and that the pro-protection position of the Radical Right party family stands in stark contrast to the generally pro-liberalisation positions of mainstream European political parties. We now proceed to a more extensive analysis of these data.

Independent variables

In the analysis, we investigate how the broader ideology of political parties correlates with support for trade liberalisation versus protection of domestic producer groups. We decompose the overall ideology of political parties into an explicitly economic dimension and a separate dimension pertaining to cultural politics, which the CHES research group refers to as GAL-TAN.Footnote4 The economic left-right question ranges from 0 to 10, with 0 corresponding to the most extreme left position and 10 as the extreme right position. The GAL-TAN (Green/Alternative/Libertarian-Traditional/Authoritarian/Nationalist) question is also on a 0–10 scale, where 0 represents the most liberal/postmaterialist position and 10 is the most traditional/authoritarian position.

Note that if we had operationalised party ideology via the question measuring a party’s general left-right ideology, we would expect a curvilinear relationship between pro-protection stances and ideology. This is because the left parties in general tend to be those that are economically extreme, whereas the ‘right’ parties in the general left-right measure are increasingly parties that emphasise cultural politics. We choose to operationalise the ideologies of parties in two dimensions, one economic and one cultural, to be able to say more about how the specific features of party ideologies relate to trade positions. This also leads to our linear expectations, where economically right-wing parties will be more in favour of trade liberalisation, and culturally authoritarian parties will favour protection of domestic actors. Having introduced and described our primary variables of interest, we move on to our central analysis.

Analysis

We now examine the ideological correlates of party positions on international trade. Our theoretical expectations lead us to estimate sparse models focusing on the economic left-right dimension, and the cultural dimension, as measured by GAL-TAN. Because countries differ in their exposure to and dependence on international trade, we estimate multilevel linear models with random effects for country, which allow us to explore the explanatory power of ideology within and across countries (Bell & Jones, Citation2015). We do this by including country-level mean ideological positions, weighted by vote share, in order to estimate within and between effects in the same models. At the party level, we include country-demeaned party positions to measure the within-country effects (Rovny et al., Citation2022).

The models presented in support our core expectation that party positioning on international trade is significantly associated with the economic and cultural ideology of parties, consistent with the idea that trade forms a part of the transnational cleavage. First, in line with our first hypothesis, trade position is strongly influenced by economic ideology across model specifications. Within countries, economically left-wing parties favour trade protection over liberalisation. We also report a significant country-level effect: countries in which political parties are more positioned to the economic left tend to resist the liberalisation of international trade. In Model 1, we also control for government status of a party, given the expectation that parties in governing coalitions will have less flexibility and more external constraints, and therefore be less staunch in their opposition to trade liberalisation. Looking at the effect of government participation, i.e., being a member of a governing coalition at the time of the survey, in the simplest specification (Model 1), governing status reaches conventionally accepted levels of statistical significance, and substantively points in the expected direction with governing parties less likely to favour protection than opposition parties.

Table 1. Ideological correlates of trade positioning for political parties in Europe.

We next highlight that across model specifications we consistently find support for our second hypothesis, which expected a strong relationship between culturally conservative, TAN ideology and pro-protection positions on international trade. Unlike economic left-right ideology, while the coefficients for the between-country effects of GAL-TAN ideology are positive, as expected, they are not large nor are they statistically significant. This suggests that there is not a systematic difference in the trade positions of parties in countries where the party system on the whole is more or less culturally conservative. Put differently, these results indicate that the explanatory power of GAL-TAN ideology is at the party rather than country-level. Our ability to disentangle these effects stems from our model’s simultaneous estimation of between and within country differences.

We explore the relationship between party size, government status, and positioning on international trade further in Models 2 and 3. In addition to ideological and government/opposition variables, Model 2 includes a variable for the vote share of the party. We first note that our core ideological variables remain statistically and substantively significant at levels comparable to Model 1. Additionally, the size of a party is statistically significant, with the substantive interpretation that larger parties are less prone to protection than smaller parties, controlling for ideology. Yet in Model 2, government participation is statistically insignificant. Thus it appears to be party size rather than government status that is of more relevance for party positioning on international trade according to our first two models, corroborating the findings of Milner and Judkins (Citation2004, p. 111).

We probe these findings further in Model 3, in which we interact the ideological variables with the dichotomous variable that measures the government status of a party, testing the potential moderating effect of incumbency. We also control for party vote share, given the expectation that larger parties will need to build broader electoral coalitions and will therefore be less opposed to trade liberalisation, as reported in Model 2. In Model 3, the central results concerning economic left-right and GAL-TAN ideology and party size remain substantively similar to the coefficients reported in Models 1 and 2.

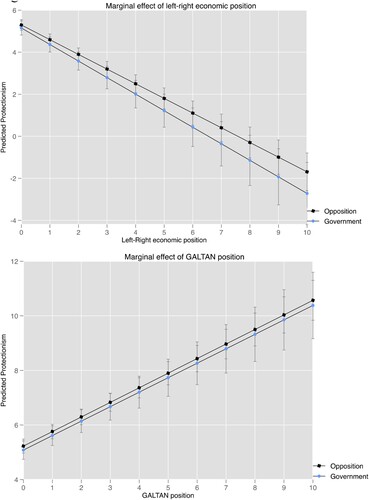

Turning to the interaction between ideology and government participation, we note that the coefficients on the interactions in Model 3 are statistically insignificant, suggesting that the effects of ideology on parties’ trade positions are not systematically different for government and opposition parties. Yet, as Brambor et al. (Citation2006, p. 74) caution ‘one cannot determine whether a model should include an interaction term simply by looking at the significance of the coefficient on the interaction term’. We thus graph these marginal effects in . The top panel of continues to show a substantively similar effect of economic left-right ideology on protectionism, independent of government status. Further, we report no significant difference between the effect of cultural ideology for government and oppositional party positioning on international trade. This is readily apparent in the bottom panel of , which shows a uniform effect of cultural conservatism on the international trade positions of political parties, both those in government and those in opposition. More generally, and to repeat the key finding, across model specifications, economic leftness and cultural conservatism are significantly associated with more protectionist positioning on the question of international trade for political parties in Europe. We thus report support for the two hypotheses we set out to test in this article.

Figure 3. The effects of ideology and government status on trade protection (from Model 3).

Note: Figure made using the plottig graphic scheme (Bischof, Citation2017).

Our analytical strategy followed recommendations to use within-between random effects models in multilevel analysis because they model the heterogeneity at both the cluster (level 2) and observation (level 1) level (Bell et al., Citation2019). In our case, this relates to variation at both the country and party-level, which is important because political parties are nested within countries that differ in a variety of features, most notably for our purposes their dependence on trade. Our results at the country level provocatively indicate that country-level differences in the economic left-right position of the party system are statistically significant in their association with individual party positions on the question of trade liberalisation, but that party system-level GAL-TAN positioning is not. In a final step, we examine the durability of these findings when we directly model specific country-level differences of relevance to our outcome variable. Given the small number of level 2 observations, we are limited in the number of country-level variables that we can include and thus choose to focus on the importance of trade for a country as measured by World Bank data on trade as a percentage of GDP for 2019.Footnote5 The results are summarised in Model 4 of and continue to support our central findings. In particular, while there is a slight increase in R2 and an even smaller decrease in the intraclass correlation, indicating that Model 4 is a marginally better fit than the previous three models, there is no change to our substantive variables of interest and we continue to find support for our two hypotheses.

These results complement and expand upon earlier studies of party positioning on (anti-) globalisation. First, they suggest that trade follows a similar pattern as the other components frequently used to measure globalisation, which include position on the EU, immigration and multilateralism, as well as international cooperation more generally. This applies to the literature on the transnational cleavage, as well as the body of work on political parties in international political economy (e.g., Burgoon & Schakel, Citation2022; De Vries et al., Citation2021; Milner, Citation2021; Walter, Citation2021). Second, our findings add to this picture by explicating the factors that account for variation between parties. While previous studies have shown that radical right and radical left parties are staunch anti-globalists compared to mainstream parties, the drivers behind their respective opposition to trade have not been made explicit. As our study shows, these parties are moved by different rationales, the left primarily by economic concerns and the right largely by cultural factors. Although we depart from similarly grounded theoretical arguments, providing an empirical demonstration of this difference, on trade specifically, is important. Our findings suggest that while the effect of radical right and radical left policies are similar, because their underlying principles are not identical there is still not a common nationalist agenda on trade (cf. Engler, Citation2021; Garrett, Citation1998; Hays, Citation2009). At the same time, larger parties are more in favour of free trade, which adds to the debate about the convergence in positions among centre-left and centre-right parties (Haupt, Citation2010; Milner & Judkins, Citation2004). While our study does not consider the impact of neo-liberal pressure, it does suggest an effect of larger parties, who are also more likely to be in government, having to navigate between ideology and pragmatism.

Conclusion

Understanding the positioning of political parties on economic globalisation is important because the electoral successes of the radical right have contributed to a mainstreaming of their ideologies (Mudde, Citation2019), with protection from international trade a visible component of several high-profile electoral campaigns, e.g., Marine Le Pen’s 2022 contest for the presidency in France or Giorgia Meloni in Italy (Startin, Citation2022; Zulianello, Citation2022). What is more, the exogenous shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war in Ukraine and subsequent geo-political volatility have ushered in an era of re-onshoring and renewed discussions of ‘strategic autonomy’ (Aggestam & Hyde-Price, Citation2019; Jacobs et al., Citation2023; Meunier & Nicolaidis, Citation2019).

The aim of this article was to investigate the patterns of trade protection among European political parties, and to examine the extent to which party positions on international trade are empirically consistent with the emergence of the transnational cleavage in European societies. Theorists of the transnational cleavage regularly conceptualise international trade preferences as a component of this contemporary societal divide, along with immigration and European integration. Yet, empirical analyses exclusively focus on the latter (De Vries, Citation2018; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018; Jackson & Jolly, Citation2021). The literature on international political economy focusing on parties also largely relies on composite measures, combining trade with various other measures of globalisation (Burgoon & Schakel, Citation2022; Walter, Citation2021). Building on the theoretical foundations on European integration and the transnational cleavage, we argued that the positioning of political parties on the question of trade protection versus trade liberalisation should also be informed by parties’ overarching economic and cultural ideologies.

We examined these expectations via an item on trade positions included for the first time in the 2019 wave of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) on party positioning in Europe. As anticipated, party positions on international trade correlate with more general party ideology in much the same way that they do for European integration. More specifically, parties of the economic left are more likely to support protection of domestic industries, as are parties that are culturally conservative. Larger parties, those more likely to be in government, are more in favour of trade liberalisation, in comparison to smaller parties, suggesting that it is challenger parties (De Vries & Hobolt, Citation2020) of the extreme economic left and cultural conservatives that attempt to politicise trade.

Of note is the importance of economic ideology for party positions on trade. In one sense, this should not surprise us; trade is an integral aspect of economic politics. But the international aspect of trade and its close conceptual alignment with immigration and European integration, also clearly indicate the relevance of what can be broadly referred to as cultural politics in unpacking party positions on trade. Thus, we see consistent relevance of GAL-TAN ideology within countries across model specifications. Yet, the economic left-right ideology of parties is a stronger predictor of trade positions, which runs counter to immigration and EU politics (cf. Jolly et al., Citation2022). Moreover, when comparing the between country effects, it is only the overall economic left-right position of the party system, not GAL-TAN, that appears to be systematically related to party positioning on international trade. We thus provide cross-national empirical support for the argument that economics plays a large role in the politics of the transnational cleavage (De Vries, Citation2018), signalling the importance of the distributional effects of economic globalisation (cf. Walter, Citation2010). In other words, economic considerations linked to trade are key drivers of the current anti-globalisation backlash (cf. Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018, Citation2019), although it is an issue that in public debates at least, is being promoted by radical right parties with a distinct nationalist agenda. This could have important implications for how mainstream parties ultimately decide to confront anti-establishment mobilisation on trade policy and other forms of multilateral cooperation from challenger parties.

We currently lack CHES data over time which would allow us to say more about responsiveness dynamics, an essential aspect of these relationships. What is more, the CHES item remains a rather blunt instrument for measuring trade preferences in parties. Finally, post-pandemic politics as well as Europe’s relations with Russia after its invasion of Ukraine have upended the conventional conversation surrounding trade and reliance upon global value chains since the last CHES wave. This speaks to both the continued relevance of international trade as a topic of study and the need for more fine-grained measures of party positioning on trade and small n qualitative case studies. Our hope is that we can use the framework developed in this article to continue to map and ultimately explain what might make mainstream parties jump on the protectionist bandwagon or become more vocal about their support for free trade, perhaps by finding alternative strategies to address the concerns of their voters.

Acknowledgements

Author order is alphabetical; both contributed equally to this article. Earlier versions of this article were presented at Lund University’s European Union Research Group, and at ‘Reacting to the Contestation of Trade Policy in the Transatlantic Area’ workshops, online and in Salzburg, Austria. We thank all participants for their comments. We further thank J. Robert Basedow, Ryan Bakker, Dirk De Bièvre, Shawn Donnelly, Andreas Dür, Niels Gheyle, Scott Hamilton, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks, and anonymous referees for valuable feedback. We are grateful to Alexander Dannerhäll for excellent research assistance. We further acknowledge support from the Norwegian Research Council grant number 303100 and the Swedish Research Council grant number 2016-01810.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jonathan Polk

Jonathan Polk is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Lund University.

Guri Rosén

Guri Rosén is an Associate Professor at Oslo Business School, Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet) and an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Oslo.

Notes

1 Part of the reason that the positions of parties on trade did not enter the analysis was the fact that the CHES item was only included in the survey for the most recent round in 2019, well after initial theoretical and empirical examination of the transnational cleavage began.

2 Using the measure trade as a percentage of GDP (The World Bank, Citation2019).

3 We follow the party family classification scheme of the CHES trend file codebook. The CHES classification is based on Hix and Lord (Citation1997) and the Derksen classification for Central/Eastern Europe. For more information, see chesdata.eu.

4 Exact question wordings for both dimensional questions are included in the appendix.

5 This variable also has important limitations as a measure of trade exposure because EU member states trade primarily with one another and this intra-EU trade is unaffected by EU trade policy.

References

- Aggestam, L., & Hyde-Price, A. (2019). Double trouble: Trump, transatlantic relations and European strategic autonomy. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(S1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12948

- Allen, C. S. (2009). Empty nets’ social democracy and the ‘catch-all party thesis’ in Germany and Sweden. Party Politics, 15(5), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068809336389

- Arndt, C. (2013). The electoral consequences of third way welfare state reforms: Social democracy’s transformation and its political costs. Amsterdam University Press.

- Baccini, L., Guidi, M., Poletti, A., & Yildrim, A. (2022). Trade liberalization and labor market institutions. International Organization, 76(1), 70–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000138

- Bakker, R., De Vries, C., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2015). Measuring party positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2010. Party Politics, 21(1), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812462931

- Bardi, L., Bartolini, S., & Trechsel, A. H. (2014). Responsive and responsible? The role of parties in twenty-first century politics. West European Politics, 37(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887871

- Bartolini, S., & Mair, P. (2007). Identity, competition and electoral availability: The stabilisation of European electorates 1885–1985. ECPR Press.

- Bell, A., Fairbrother, M., & Jones, K. (2019). Fixed and random effects models: Making an informed choice. Quality & Quantity, 53(2), 1051–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-018-0802-x

- Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2015). Explaining fixed effects: Random effects modeling of time-series cross-sectional and panel data. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(1), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2014.7

- Benoit, K., & Laver, M. (2006). Party policy in modern democracies. Routledge.

- Benoit, K., & Laver, M. (2007). Estimating party policy positions: Comparing expert surveys and hand-coded content analysis. Electoral Studies, 26(1), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2006.04.008

- Beramendi, P., Häusermann, S., Kitschelt, H., & Kriesi, H. (eds.). (2015). The politics of advanced capitalism. Cambridge University Press.

- Bisbee, J., Mosley, L., Pepinsky, T. B., & Rosendorff, B. P. (2020). Decompensating domestically: The political economy of anti-globalism. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(7), 1090–1102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1678662

- Bischof, D. (2017). New graphic schemes for stata: Plotplain and plottig. The Stata Journal, 17(3), 748–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1701700313

- Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpi014

- Braun, D., Popa, S. A., & Schmitt, H. (2019). Responding to the crisis: Eurosceptic parties of the left and right and their changing position towards the European union. European Journal of Political Research, 58(3), 797–819. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12321

- Burgoon, B. (2012). Partisan embedding of liberalism: How trade, investment, and immigration affect party support for the welfare state. Comparative Political Studies, 45(5), 606–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011427132

- Burgoon, B., & Schakel, W. (2022). Embedded liberalism or embedded nationalism? How welfare states affect anti-globalisation nationalism in party platforms. West European Politics, 45(1), 50–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1908707

- Chan, Z. T., & Meunier, S. (2022). Behind the screen: Understanding national support for a foreign investment screening mechanism in the European Union. Review of International Organizations, 17(3), 513–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09436-y

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018). The trade origins of economic nationalism: Import competition and voting behavior in Western Europe. American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), 936–953. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12358

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2019). The surge of economic nationalism in Western Europe. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 128–151. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.128

- Dancygier, R., & Walter, S. (2015). Globalization, labor market risks, and class cleavages. In P. Beramendi, S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt, & H. Kriese (Eds.), The politics of advanced capitalism (pp. 133–156). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Sio, L., & Weber, T. (2014). Issue yield: A model of party strategy in multidimensional space. American Political Science Review, 108(4), 870–885. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000379

- De Ville, F., & Gheyle, N. (2023). How TTIP split the social-democrats: Reacting to the politicisation of EU trade policy in the European parliament. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2223226

- De Vries, C. E. (2018). The cosmopolitan-parochial divide: Changing patterns of party and electoral competition in The Netherlands and beyond. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(11), 1541–1565. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1339730

- De Vries, C. E., & Edwards, E. E. (2009). Taking Europe to its extremes: Extremist parties and public Euroscepticism. Party Politics, 15(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068808097889

- De Vries, C. E., & Hobolt, S. B.. (2020). Political entrepreneurs. Princeton University Press.

- De Vries, C. E., Hobolt, S. B., & Walter, S. (2021). Politicizing international cooperation: The mass public, political entrepreneurs, and political opportunity structures. International Organization, 75(2), 306–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000491

- De Vries, C. E., & Marks, G. (2012). The struggle over dimensionality: A note on theory and empirics. European Union Politics, 13(2), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116511435712

- De Wilde, P., Koopmans, R., Merkel, W., Strijbis, O., & Zürn, M. (eds.). (2019). The struggle over borders: Cosmopolitanism and communitarianism. Cambridge University Press.

- Donnelly, S. (2023). Political party competition and varieties of US economic nationalism: Trade wars, industrial policy and EU-US relations. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2226168

- Dür, A., Hamilton, S., & De Bièvre, D. (2023). Reacting to the politicization of trade policy. Journal of European Public Policy.

- Ehrlich, S., & Maestas, C. (2010). Risk orientation, risk exposure, and policy opinions: The case of free trade. Political Psychology, 31(5), 657–684.

- Engler, F. (2021). Political parties, globalization and labour strength: Assessing differences across welfare state programs. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 670–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12413

- Garrett, G. (1998). Global markets and national politics: Collision course or virtuous circle? International Organization, 52(4), 787–824. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550752

- Gourevitch, P. A. (1986). Politics in hard times: Comparative responses to international economic crises. Cornell University Press.

- Green-Pedersen, C. (2012). A giant fast asleep? Party incentives and the politicisation of European integration. Political Studies, 60(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00895.x

- Green-Pedersen, C. (2019). The reshaping of West European party politics: Agenda-setting and party competition in comparative perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Hainmueller, J., & Hiscox, M. J. (2006). Learning to love globalization: Education and individual attitudes toward international trade. International Organization, 60(2), 469–498.

- Halikiopoulou, D., Nanou, K., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2012). The paradox of nationalism: The common denominator of radical right and radical left euroscepticism. European Journal of Political Research, 51(4), 504–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02050.x

- Haupt, A. B. (2010). Parties’ responses to economic globalization: What is left for the left and right for the right? Party Politics, 16(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068809339535

- Hays, J., Ehrlich, S., & Peinhardt, C. (2005). Government spending and public support for trade in the OECD: An empirical test of the embedded liberalism thesis. International Organization, 59(2), 473–494. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818305050150

- Hays, J. C. (2009). Globalization and the new politics of embedded liberalism. Oxford University Press.

- Hix, S., & Lord, C. (1997). Political parties in the European union. St. Martin's Press.

- Honeker, A. (2022, October 28-29). Populist right success and mainstream party adaptation: The case of economic globalization. Paper prepared for presentation at the International political economy society 2022 conference.

- Hooghe, L. (2012). Images of Europe: How commission officials conceive their institution's role. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 50(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02210.x

- Hooghe, L., Bakker, R., Brigevich, A., De Vries, C., Edwards, E., Marks, G., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. (2010). Reliability and validity of measuring party positions: The Chapel Hill expert surveys of 2002 and 2006. European Journal of Political Research, 49(5), 687–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01912.x

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. J. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310

- Huber, E., Huber, M. E., & Stephens, J. D. (2001). Development and crisis of the welfare state: Parties and policies in global markets. University of Chicago press.

- Hutter, S., Grande, E., & Kriesi, H. (eds.). (2016). Politicising Europe: Integration and mass politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Ivaldi, G., & Mazzoleni, O. (2020). Economic populism and sovereigntism: The economic supply of European radical right-wing populist parties. European Politics and Society, 21(2), 202–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2019.1632583

- Jackson, D., & Jolly, S. (2021). A new divide? Assessing the transnational-nationalist dimension among political parties and the public across the EU. European Union Politics, 22(2), 316–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520988915

- Jacobs, T., Gheyle, N., Ville, F. D., & Orbie, J. (2023). The hegemonic politics of ‘strategic autonomy’ and ‘resilience’: COVID-19 and the dislocation of EU trade policy. Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13348

- Jensen, J. B., Quinn, D. P., & Weymouth, S. (2017). Winners and losers in international trade: The effects on US presidential voting. International Organization, 71(3), 423–457. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818317000194

- Jolly, S., Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2022). Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2019. Electoral Studies, 75, 102420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102420

- Karreth, J., Polk, J. T., & Allen, C. S. (2013). Catchall or catch and release? The electoral consequences of social democratic parties’ march to the middle in Western Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 46(7), 791–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012463885

- Kinski, L. (2018). Whom to represent? National parliamentary representation during the eurozone crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(3), 346–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1253764

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Dolezal, M., Helbling, M., Höglinger, D., Hutter, S., & Wüest, B. (2012). Political conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2006). Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 921–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge University Press.

- Lacewell, O. P. (2017). Beyond policy positions: How party type conditions programmatic responses to globalization pressures. Party Politics, 23(4), 448–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815603241

- Langsæther, P. E., & Stubager, R. (2019). Old wine in new bottles? Reassessing the effects of globalisation on political preferences in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 58(4), 1213–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12332

- Lipset, S. M., & Rokkan, S. (1967). Cleavage structures, party systems, and voter alignments: An introduction. In S. M. Lipset & S. Rokkan (Eds.), Party systems and voter alignments: Cross-national perspectives (pp. 1–64). The Free Press.

- Mader, M., Steiner, N. D., & Schoen, H. (2020). The globalisation divide in the public mind: Belief systems on globalisation and their electoral consequences. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(10), 1526–1545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1674906

- Mair, P. (2009). Representative versus responsible government. MPIfG Working Paper 09/8. Cologne.

- Mair, P., & Mudde, C. (1998). The party family and its study. Annual Review of Political Science, 1(1), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.211

- Mansfield, E. D., & Mutz, D. C. (2009). Support for free trade: Self-interest, sociotropic politics, and out-group anxiety. International Organization, 63(3), 425–457.

- March, L., & Mudde, C. (2005). What's left of the radical left? The European radical left after 1989: Decline and mutation. Comparative European Politics, 3(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110052

- Margalit, Y. (2012). Lost in globalization: International economic integration and the sources of popular discontent. International Studies Quarterly, 56(3), 484–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2012.00747.x

- Marks, G., Hooghe, L., Steenbergen, M. R., & Bakker, R. (2007). Crossvalidating data on party positioning on European integration. Electoral Studies, 26(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2006.03.007

- Martínez-Gallardo, C., Cerda, N. D. L., Hartlyn, J., Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Bakker, R. (2022). Revisiting party system structuration in Latin America and Europe: Economic and socio-cultural dimensions. Party Politics.

- McDonald, M. D., Mendes, S. M., & Kim, M. (2007). Cross-temporal and cross-national comparisons of party left-right positions. Electoral Studies, 26(1), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2006.04.005

- McElroy, G., & Benoit, K. (2012). Policy positioning in the European Parliament. European Union Politics, 13(1), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116511416680

- Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

- Meunier, S., & Nicolaidis, K. (2019). The geopolitization of European trade and investment policy. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(S1), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12932

- Milner, H. V. (2021). Voting for populism in Europe: Globalization, technological change, and the extreme right. Comparative Political Studies, 54(13), 2286–2320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414021997175

- Milner, H. V., & Judkins, B. (2004). Partisanship, trade policy, and globalization: Is there a left-right divide on trade policy? International Studies Quarterly, 48(X), 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.00293.x

- Mudde, C. (2019). The far right today. John Wiley & Sons.

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press.

- Oesch, D., & Rennwald, L. (2018). Electoral competition in Europe's new tripolar political space: Class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right. European Journal of Political Research, 57(4), 783–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12259

- Otjes, S., Ivaldi, G., Jupskås, A. R., & Mazzoleni, O. (2018). It's not economic interventionism, stupid! reassessing the political economy of radical right-wing populist parties. Swiss Political Science Review, 24(3), 270–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12302

- Pinggera, M. (2021). Congruent with whom? Parties’ issue emphases and voter preferences in welfare politics. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(12), 1973–1992. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1815825

- Polk, J., Rovny, J., Bakker, R., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Koedam, J., Kostelka, F., Marks, G., Schumacher, G., Steenbergen, M., Vachudova, M., & Zilovic, M. (2017). Explaining the salience of anti-elitism and reducing political corruption for political parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill expert survey data. Research & Politics, 4(1), 2053168016686915. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168016686915

- Rogowski, R. (1989). Commerce and coalitions: How trade affects domestic political alignments. Princeton University Press.

- Rooduijn, M., Burgoon, B., Van Elsas, E. J., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2017). Radical distinction: Support for radical left and radical right parties in Europe. European Union Politics, 18(4), 536–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517718091

- Rommel, T., & Walter, S. (2018). The electoral consequences of offshoring: How the globalization of production shapes party preferences. Comparative Political Studies, 51(5), 621–658.

- Rose, R. (2014). Responsible party government in a world of interdependence. West European Politics, 37(2), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887874

- Rovny, J., Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2022). Contesting Covid: The ideological bases of partisan responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. European Journal of Political Research, 61(4), 1155–1164.

- Rovny, J., & Edwards, E. E. (2012). Struggle over dimensionality: Party competition in Western and Eastern Europe. East European Politics and Societies, 26(1), 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325410387635

- Startin, N. (2022). Marine Le Pen, the Rassemblement National and breaking the ‘glass ceiling’? The 2022 French presidential and parliamentary elections. Modern & Contemporary France, 30(4), 427–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639489.2022.2138841

- Struthers, C. L., Hare, C., & Bakker, R. (2020). Bridging the pond: Measuring policy positions in the United States and Europe. Political Science Research and Methods, 8(4), 677–691. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.22

- The World Bank. (2019). World Bank national accounts data. Trade (% of GDP). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS

- Thies, Cameron G., & Porche, S. (2007). The political economy of agricultural protection. The Journal of Politics, 69(1), 116–127.

- Treib, O. (2021). Euroscepticism is here to stay: What cleavage theory can teach us about the 2019 European Parliament elections. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1737881

- Trubowitz, P., & Burgoon, B. (2022). The retreat of the west. Perspectives on Politics, 20(1), 102–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720001218

- Van de Wardt, M., De Vries, C. E., & Hobolt, S. B. (2014). Exploiting the cracks: Wedge issues in multiparty competition. The Journal of Politics, 76(4), 986–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381614000565

- Volkens, A. (2007). Strengths and weaknesses of approaches to measuring policy positions of parties. Electoral Studies, 26(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2006.04.003

- Volkens, A., Krause, W., Lehmann, P., Matthieß, T., Merz, N., Regel, S., & Weßels, B. (2019). The manifesto data collection. Version 2019b. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR).

- Walter, S. (2010). Globalization and the welfare state: Testing the microfoundations of the compensation hypothesis. International Studies Quarterly, 54(2), 403–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00593.x

- Walter, S. (2021). The backlash against globalization. Annual Review of Political Science, 24(1), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102405

- World Trade Organization. (2020). Annual report. World Bank Publications. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/anrep_e/anrep20_e.pdf

- Zulianello, M. (2022). Italian general election 2022: The populist radical right goes mainstream. Political Insight, 13(4), 20–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/20419058221147590

- Zürn, M., & De Wilde, P. (2016). Debating globalization: Cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as political ideologies. Journal of Political Ideologies, 21(3), 280–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2016.1207741

Appendix

Chapel Hill Expert Survey on party positioning in Europe, ideological question wordings:

Economic left-right:

LRECON = position of the party in 2019 in terms of its ideological stance on economic issues. Parties can be classified in terms of their stance on economic issues such as privatition, taxes, regulation, government spending, and the welfare state. Parties on the economic left want govern- ment to play an active role in the economy. Parties on the economic right want a reduced role for government.

0 = extreme left:

5 = center:

10 = extreme right

GAL-TAN:

GALTAN = position of the party in 2019 in terms of their views on social and cultural values. ‘Libertarian’ or ‘postmaterialist’ parties favour expanded personal freedoms, for example, abortion rights, divorce, and same-sex marriage. ‘Traditional’ or ‘authoritarian’ parties reject these ideas in favour of order, tradition, and stability, believing that the government should be a firm moral authority on social and cultural issues.

0 = Libertarian/Postmaterialist

:5 = center:

10 = Traditional/Authoritarian