ABSTRACT

Do basic administrative arrangements in the national public sector affect the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), and if so, how? AMR, one of humanity’s most pressing challenges according to the World Health Organization, is typically caused by factors inherent to the natural sciences. In this paper, however, we investigate the indirect causal effect of politics and administration on the management of AMR. In a mixed-methodological approach drawing on a panel regression combined with 46 semi-structured interviews with senior bureaucrats and experts from all member states of the European Union (EU), we derive four distinct clusters of countries in AMR governance. The analysis shows that politico-administrative arrangements in the EU follow a north-to-south and east-to-west pattern in the prevalence of AMR. We apply institutional theories of path dependency and administrative autonomy to explain such ‘worlds’ of AMR governance.

Introduction: taking institutions from explanandum to explanans

This paper explores an intriguing pattern of comparative national performance on a significant public health issue where differences in institutional design appear to be closely associated with policy outcomes. Our analysis suggests that those differences in institutional design and governance have an independent explanatory capacity on policy performance when we control for a variety of economic and social factors.

In some ways, this pattern should only be expected. Understanding public policy or public administration is first and foremost a matter of understanding institutional arrangements (Weaver & Rockman, Citation1993). Institutions reflect, and reproduce, dominant social norms of appropriate behaviour (March & Olsen, Citation1989). Also, administrative traditions and sector-specific features continue to shape preferences on institutional design. In a comparative perspective there is evidence that the same policy sector tends to have similar institutional arrangements in different countries (Peters, Citation2021).

Yet, the observation that the organisation of government and nature of the interaction between politicians and public servants determine to some degree the systemic performance of government warrants a comparative discussion on the ramifications of institutional design. This is in part because institutional factors are important in their own right as elements of a political and democratic system and in part because they shape key aspects of public administration like autonomy, integrity in relation to the political leadership, and discretion for professionals and experts to promote expertise-based objectives and measures.

The empirical context we explore is the work in the European Union (EU) member states to mitigate antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a major public health concern across the world. AMR refers to bacteria that have developed resistance to antibiotics caused by excessive consumption of antibiotics in human healthcare, livestock food production, and environmental spill (Scott et al., Citation2019). Resistant pathogens spread easily across the globe through international travel and trade, requiring essentially all governments to do their part and to help coordinate international efforts to use antibiotics prudently (WHO, Citation2015). These problems are exacerbated in some countries by a lack of knowledge or resources to monitor the consumption of antibiotics and the prevalence of resistant bacteria. An international group of public health experts recently concluded in The Lancet that AMR ‘has emerged as one of the leading public health threats of the twenty-first century’ (Murray et al., Citation2022), estimated to have caused close to 5 million deaths globally in 2019 and projected to cause around 10 million deaths annually from around year 2050 (see also O’Neill, Citation2014).

The prevalence of AMR varies significantly across Europe. A recent report from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) states that

the reported AMR percentages for several bacterial species-antimicrobial group combinations varied widely among countries, with a north-to-south and west-to-east gradient evident. In general, the lowest AMR percentages were reported by countries in the north of Europe and the highest by countries in the south and east. (ECDC, Citation2022, p. 27)

Intriguingly, the north-to-south and east-to-west divide in AMR corresponds closely with differences in the institutional relationships between politics and administration. Indeed, our expert interviews, which will be presented in detail below, offer a consistent observation that the relationship between politics and administration is ‘key’ to understanding the efforts and approaches to address the AMR problem. Further, the interviewees’ statements dovetail with established ideas of European administrative traditions (Peters, Citation2021). For example, the ‘Napoleonic’ cases of Southern Europe and the Nordic cases of Northern Europe stand out distinctly. Further, the Central and Eastern European countries that have had a history of authoritarian control and administrative histories that are different from Western Europe, also constitute a distinct set of systems. This begs the question whether, and if so how, administrative arrangements in the national civil service make a difference for managing AMR.

The regional differences of AMR management suggest that administrative traditions continue to influence contemporary governance. Moreover, they strengthen the notion that context matters (cf. Pollitt, Citation2013). Many of the contextual factors that scholars seek to eliminate in quantitative research designs may be directly or indirectly consequential for the performance of political and administrative institutions.

Instead, central to our argument is the notion of ‘the causes of the causes’. While the development of AMR is straightforward, referring to an excessive consumption of antibiotics in medicine and livestock production, such outcomes are embedded in complex governance arrangements. Fundamentally, the governance challenge of AMR is to fully understand the causal chain ranging from local individual consumption to the aggregate, global prevalence of resistant bacteria; how to manage such interconnections across jurisdictional levels and borders; and how to mitigate the consequences for public health.

A top civil servant and leading AMR expert (Dame Sally Davies) in Europe described the situation in an interview with the present authors thus: ‘the biggest problem with AMR is not the science – it is the governance. And it is the market failure which means we do not get the investments we need in the private sector into solutions’. Or, as Peter Davey (Citation2015, p. 2931) proclaimed in his 2015 Garrod Lecture ‘Why is Improvement Difficult?’, it is time to embrace the 40 years of knowledge of AMR, but to ‘look beyond antimicrobial prescribing to evidence from the social sciences about how to change behaviour’.

Institutions and AMR

Before examining how politics and administration are related to AMR, it is important to outline what AMR refers to. AMR means that resistant bacteria develop and spread in subsets of resistant genes in both the natural environment and in clinical settings, primarily caused by excessive use of antibiotics in human medicine and livestock production. It thus follows an evolutionary microbiological procedure, where bacterial resistance occurs when antimicrobials interact with their targets through either gene mutation or through horizontal gene transfer (Martínez & Baquero, Citation2014). The transmission of AMR occurs in an almost uncontrolled fashion between humans, animals and the environment (Larsson & Flach, Citation2022) as well as across national boundaries, exacerbating problems of coordinated intervention.

Transmissions are driven by a myriad of factors which current space prevents us from summarising. Scholars emphasise basic factors such as pollution (Larsson & Flach, Citation2022), improper handling of unused drugs (Anwar et al., Citation2020), production of antibiotics in wastewater (Larsson, Citation2014) and contamination in aquaculture (Cabello et al., Citation2016). Indirect factors driving AMR transmission include population size and density and institutional factors such as hospital sanitation (Collignon et al., Citation2018; Dancer, Citation2014), low public awareness, excessive consumption, and public demands (Davis et al., Citation2018; Ebert, Citation2007), and inert and malfunctioning ‘prescription cultures’ (Charani et al., Citation2013). Previous research has also demonstrated strong positive associations between corruption at the sub-regional level in Europe and the hospital usage of antibiotics (Rönnerstrand & Lapuente, Citation2017; see also Collignon et al., Citation2015).

How can we think of the explanatory capacity and causal mechanism of politico-administrative institutional arrangements to address the prevalence of AMR? Addressing these questions is difficult, not least because ‘institutions’ encompasses both structures and formal and informal rules and ‘hidden orders’ (Della Porta & Vannucci, Citation2012) that persist in path dependent fashion (Thelen & Steinmo, Citation1992). In addition, institutions are devoid of agency (Emmenegger, Citation2021), or could be seen as arenas for agency (Hall, Citation1986), and therefore cannot directly cause the flow of resistant bacteria. At the same time, agency is often a fundamental driver of institutional change, which means that institutional analysis, despite its structural orientation, needs to find ways of considering the role of agency (Emmenegger, Citation2021; Thelen, Citation2004).

Institutions also shape behaviour by inculcating certain values in their members; a logic of appropriateness in March and Olsen’s terms (Citation1989). Individuals learn the values and routines of organisations, and thereby learn how to make the ‘right’ decisions. In the AMR policy domain there are a number of sets of alternative, and potentially contending, professional values which may have a bearing on their decisions and actions; health professionals, clinical staff such as medical doctors, epidemiologists and microbiologists as well as agriculture specialists and public servants are all involved in AMR work. In addition, these professional groups are connected to international networks that may perceive the problems, and especially the solutions, differently.

Finally, institutions may facilitate or prevent political and administrative agency and interactions between the two spheres of government. Constitutional rules and historically embedded practices set effective boundaries on some forms of agency while prescribing other forms. For instance, close linkages between politics and administration increases the probability of political control over the administration, just as agencies operating at arm’s length from the political leadership enjoy more latitude for the agency’s expertise.

In the present comparative analysis, we expect public health officials to have relatively similar perspectives on the AMR issue across the countries, given similarities in training. Public servants should be expected to be the most different, given long-standing differences in the styles and autonomy of these officials (Peters, Citation2021).

Again, however, these individuals whose behaviours determine outcomes for AMR policy tend to be members of several institutions, each of which will have its own institutional logic (Thornton et al., Citation2012). To the extent that these alternative institutional logics conflict with one another the capacity for concerted and effective institutional action will be diminished. Similarly, the presence of formal and informal institutions within this policy domain may also influence the executive capacity to make and deliver effective public services (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004).

The fundamental point here is that the capacity of countries to make and deliver effective policies for AMR depends on their institutions and the individuals embedded within those institutions. Whether agency is driven by a logic of consequentiality, emphasising expected utility, or a logic of appropriateness (March & Olsen, Citation1989) where social norms prescribe behaviour, institutions shape individual behaviour and agency more broadly.

The administrative echelon of government that is our primary focus is highly institutionalised in formal law and social rules. For instance, administrative and constitutional law serves most political orders with clear formulations on the role of the bureaucratic organisation vis-à-vis citizens and their nominal masters, which guide bureaucrats to swift and accurate action just as much as it serves the public with stability and predictability in the exercise of public power (Carelli and Peters, Citationforthcoming).

While practices and tasks are often amended, and public authorities undergo significant modernisation in response to developments in society, the basic bureaucratic patterns typically remain over long time periods. Those inherited rules and procedures may not, however, be appropriate for coping with policy issues that involve complex scientific detail. Further, a fragmented institutional structure that has grown up and become well-institutionalised over time may make coherent action in dealing with such issues more difficult. We will return to explaining these institutions in greater detail in the Theory section below.

This very brief discussion on the significance of institutions in shaping social, political and administrative behaviour provides several pointers and ideas on how we should approach the issue of how variables normally associated with the social sciences relate to the prevalence of AMR. So far, research has had a predominantly quantitative approach when studying global patterns and causes of AMR (e.g., Murray et al., Citation2022). The main message – and indeed the most alarming finding – here is that AMR is most prevalent in low-income countries which lack many of the basic institutional arrangements required to control antibiotic consumption and ensure stewardship. For instance, the global spread of AMR is linked to poor hospital sanitation, overcrowded cities, and ‘bad governance’ (Collignon et al., Citation2018).

However, large-N analyses tend to contrast very different contexts with rather different specific challenges to AMR, producing powerful statistical findings but where contextually defined causal mechanisms are absent; associations between variables may be highly significant but, we suggest, also require a deeper understanding of precisely which factors produce such correlations. Therefore, uncovering the critical causal mechanisms requires not only the degree or quality of government charged with AMR policy but also the heterogeneity of institutional governance arrangements, particularly the relationship between politics and administration.

In order to address this analytical problem, the present analysis draws on a mixed methods approach that enables us both to provide robust quantitative evidence on the association between AMR prevalence and institutional variables as well as qualitative interview data to place the quantitative evidence in context and to explore causal mechanisms. Thus, we employ different methods to address different analytical tasks, and then align the findings from those different analyses into a joint analysis drawing on the combined strengths of quantitative and qualitative methods and analyses.

The next section outlines the theory and analytical framework of analysis. We then discuss the data and method in detail before we proceed to the quantitative and qualitative analyses. The paper closes with a concluding discussion.

The four ‘worlds’ of politics and administration in the EU

We mentioned earlier ECDC’s observation that the AMR situation in the EU can best described with a north-to-south and a west-to-east gradient (ECDC, 2022, p. 27). AMR is least prevalent in the northern and western countries in the Union and most prevalent in the southern and Central and Eastern (CEE) European states. This categorisation of EU member states corresponds closely with the different administrative traditions on the European continent. These traditions could be seen as clusters of norms and values pertaining to the relationship between the political leadership and the public service (Peters, Citation2021).

Drawing on the administrative traditions theory – a predominantly institutional theory – and the institutional arrangements and politico-administrative relationships in the four regions of the EU, we create four coherent analytical models, or ‘worlds’, of AMR administration. The basic research question of the paper is whether there exists a causal relationship between these different models of AMR governance and administration and the prevalence of AMR.

The different ‘worlds’ of AMR administration represent generalisations of the features of the countries in their respective regions. Thus, we should expect no country to present a perfect example of that ‘world’, but also that the countries in that category share some basic, significant feature related to institutional setup, the relationship between politicians and public servants, or the degree of political control of the public service more broadly. The categorisation also stipulates that these features set the countries in a ‘world’ distinctly apart from those in other ‘worlds’. These ‘worlds’ are also impacted by their membership in the EU, which might be expected to have some homogenising influence on their behaviour. There may have been some impact by the EU, but here and in other studies many of the inherited patterns of behaviour do survive (Ongaro, Citation2009; Rugge, Citation2012). We will now describe the four different ‘worlds’ according to three dimensions: administrative institutional arrangements; administrative autonomy; and politico-administrative relationships.

Administrative institutional arrangements

Following institutional theory as previously discussed, we assume that the institutional arrangement of a public service shapes action within that administration and its exchanges with the political leadership. We thus stipulate that the overarching institutional arrangement of the state shapes to a significant degree the scope and latitude of administrative action in relation to the political leadership. Put slightly differently, this dimension describes how the state is administered to execute legislation and regulations; to uphold a provision of public goods; and to ensure expertise in public policy design.

The most common arrangement throughout Europe is the system of government agencies. These are relatively permanent executive institutions in the state machinery, although their specific function varies across countries (see for instance Bach et al., Citation2012). Agencies in most countries are products of New Public Management reform during the 1980s and 1990s with the objective to separate the policy-making and executive roles of traditional ministries into departments charged with the former role and agencies tasked with the latter role (see Pollitt et al., Citation2004; Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2017). These agencies also have become more important, and more visible, following the COVID pandemic.

However, in some Central and East European countries, e.g., Bulgaria, Croatia, Poland and Slovenia, public health programmes are not delivered by executive agencies but by ministries charged with drafting and implementing policies and programmes. The ministry is supported and advised by a fairly small public health institute which is not a line organisation.

Administrative autonomy

There is no shortage of studies on administrative autonomy in the scholarly literature (see e.g., Aberbach et al., Citation1981; Overeem, Citation2005; Peters, Citation2018). The fundamental principle sustaining administrative autonomy, as outlined by Weber and Wilson, is that the political aspects of issues should be separated from the administrative aspects of those issues. The administrative process should be guided by values such as legality, due process, impartiality and accountability and should not be subject to political pressure. While there is a broad understanding of the merits of this arrangement across the liberal democratic countries, the institutional framework sustaining administrative autonomy varies extensively across European states, both in terms of its form and extent (Verhoest et al., Citation2004, Citation2010).

Administrative autonomy is particularly important when dealing with issues related to science or technology (see Carpenter, Citation2001). While administrative autonomy may have a variety of dimensions, e, g. budgets or personnel decisions, in the present analysis policy autonomy is the key aspect of autonomy. There must always be some form of review of these decisions, determining the legality of the substance and process. The key question is whether the public service has both the autonomy to initiate actions as well as the capacity to enforce measures.

Furthermore, administrative autonomy is a prerequisite for transnational expert networks to efficiently coordinate and share data and information on the AMR situation. The EU Treaty defines public health as a matter of ‘national competence’ which means that it is up to the Member States to ensure coordination. Again, addressing problems of high complexity that can spread quickly across national borders requires experts to be able to coordinate, formally and informally, across regions (Carpenter, Citation2001). This is particularly significant in the public health sector where politicians often lack the knowledge to decide the medically appropriate course of action to take in response to emerging issues (Carelli & Pierre, Citation2022). At the same time, since elected officials often find themselves taking the blame for interventions suggested by the public health agency – we need only think of the Covid pandemic lockdowns – politicians have frequently overruled the public health experts when their advice and actions were seen as too invasive to the public. Thus, while there is much to suggest that expertise agencies require, and are granted, more autonomy than other types of agencies (see Carpenter, Citation2001), that autonomy is not unconditional.

Politico-administrative relationships

Governments need to be able to control that the public service is undertaking action that has been adopted by decision makers. At the same time, the public service operates in a constitutional framework emphasising legality, due process and accountability. The EU member states differ with regard to how their governance arrangements strike the balance between administrative autonomy and political control. We will use three different stylised models – Advice, Dialogue, and Command – to describe the overall nature of the interactions between the political leadership and the civil servants.

‘Advice’ in the typology refers to the ‘bottom-up’ provision of advice to elected officials by specialised civil servants. While there are significant sources of expertise in the corporate and non-profit sectors (Hustedt, Citation2018), the public service is a key player in the policy process providing knowledge and information to politicians. Moreover, the provision of policy advice varies in both style and substance, from routinised feedback mechanisms to ad hoc advice on specific issues. And again, we note the tendency towards an increasing politicisation of policy advice and the political role of advisors.

‘Dialogue’ denotes an interactive relationship between politicians and public servants which could be initiated by either party. It refers to a non-hierarchical exchange of views and ideas which can be either issue-specific or part of a more long-term continuous discussion on policy and strategy.

‘Command’, finally, refers to a relationship where the political leadership, following very limited interaction with the public service, gives the bureaucracy firm directives with only a minimum of administrative latitude. This model is thus a strict hierarchical relationship between politics and administration.

Linkages to actors

Most of the literature on administrative traditions focuses on the upper levels of the public bureaucracy. Managing AMR, however, depends heavily on the behaviour of individual doctors far from the apex of power who may not be public employees.These dispersed actors are crucial for the implementation of programmes to reduce AMR. What mechanisms can link our findings on varying levels of AMR in European countries to the differences among administrative arrangements?

We argue that there are two mechanisms that make this linkage more or less successful. The first is that some administrative systems, especially those in Northern Europe, have corporatist legacies, with agencies making decisions about health policy involved medical associations and other relevant stakeholders into the decision process. These stakeholders are involved in, and co-opted into, the decision. The second and related mechanism is that physicians and other medical personnel are more likely to trust the government in some settings than in others, with the CEE countries for historical reasons having lower level of trust, and therefore lower levels of compliance with directives from government.

Data and method

The analysis draws on a mixed-method approach to investigate the relationship between politics, administration and AMR prevalence. The quantitative analysis helps locating patterns and confirming the direction of the relationship, and a basic indication of the coefficient’s effect size. Interviews provide additional contextual evidence that enhances our understanding of causal mechanisms and help us eliminate issues of omitted variable bias and reversed causality in the quantitative analysis. Next, we therefore turn to describe our choice of variables and estimation strategies for both the quantitative and qualitative analysis, as well as what limitations they bring for drawing conclusions from the empirical material.

Variables

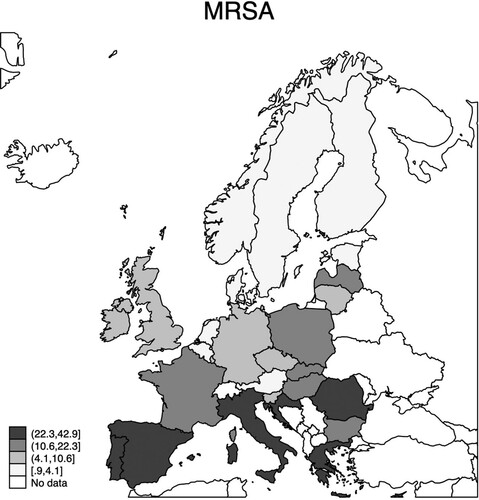

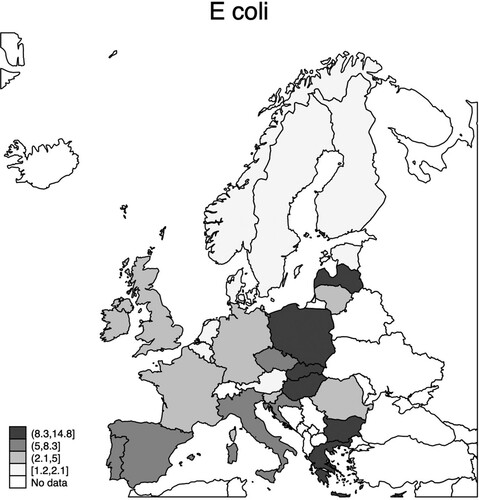

‘AMR’ refers to an aggregate of several bacterial strains and we take use of two of the most alarming ones; the averages of prevalence of resistance of (1) Escherichia coli (E coli) and (2) Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aereus (MRSA) to third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones. Logarithms are used for both variables. All data is gathered from EARS-net, a data-sharing network under the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Furthermore, we use an aggregate measure of antibiotic consumption, as standardised within the framework of EARS-net (ATC group J01). This refers to a total consumption (community and hospital sector) of antibacterials measured as ‘defined daily doses’ (DDD) per 1000 inhabitants per day. The data is mainly based on sales of antimicrobials in the country, or in combination with reimbursement data. While the standardisation has improved significantly during the last years, there are still some compatibility issues in the reporting of data across the countries. These issues are thoroughly discussed in ECDC (2021).

Previous research has found support for governance indicators to affect the prevalence of AMR. Most significantly, corruption, which can be argued to represent the opposite of government quality (cf. Rothstein, Citation2011) is strongly correlated with AMR (see Collignon et al., Citation2018; Rönnerstrand & Lapuente, Citation2017). The capacities to govern and administer the state is also, we argue, a result of the basic configuration of the state. Particularly the forms and extent to which the executive branch can steer its institutions should impact indirect causes of AMR prevalence, as argued in the previous sections.

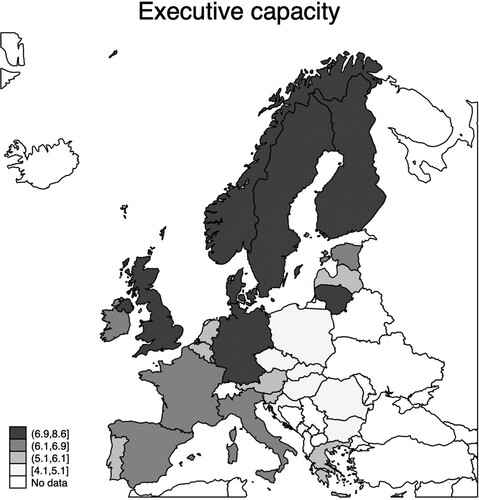

Therefore, to complement the qualitative typology of the four worlds of politics and administration in Europe, we adopt an index of Executive Capacity compiled by the Bertelsmann Stiftung including the following items: steering capability, policy implementation and institutional learning. In that order, these variables refer to (1) the roles of strategic planning and expert advice, the effectiveness of interministerial coordination and regulatory impact assessments, and the quality of consultation and communication policies; (2) the government’s ability to ensure effective and efficient task delegation to ministers, agencies or subnational governments; and (3) the government’s ability to reform its own institutional arrangements and improve its strategic orientation. The data which varies from 1–10 is included in the Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI), Bertelsmann Stiftung.

This composite measure is therefore concerned with governance quality rather than governance categories per se, but its construct embraces more governance aspects that relate directly to the present study than merely ‘control of corruption’ or impartial administration. Interpreting these scores must be done with some caution, since they are perception-based. However, both Bertelsmann and V-Dem have robust validation systems in place to minimise bias. The Appendix (Figure A and Table A2) presents descriptive data for each country and variable, supporting the classification of the ‘four worlds’ of politico-administrative arrangements in relation to AMR.

In addition, we add some other higher-level variables to control for alternative factors that might influence the focal relationship and that have been found in previous studies (e.g., Collignon et al., Citation2018). These are GDP per capita (logarithm); total antibiotic consumption; control of corruption; political decentralisation measures (local and regional government); level of electoral democracy; and a civil society index.

These factors are hypothesised to influence the prevalence of AMR. First, the total consumption of antibiotics is assumed to relate to AMR, but as Collignon et al. (Citation2018) have demonstrated, such a relationship is not linear; increasing the consumption of antibiotics does not increase the spread of resistant pathogens per se, but is rather amplified by poor sanitation and hygiene in hospitals and other institutional factors, which themselves can be the outcome of high degrees of corruption and low economic development (cf. Rönnerstrand & Lapuente, Citation2017). The economy is further expected to be negatively linked to AMR as managing the issue is related to significant public expenditure. Lastly, the quality of democratic institutions enhances the transparency and scrutiny of antibiotic prescription and bacterial outbreaks, which is why we assume it to be directly related to lower prevalence of AMR. Similarly, given antibiotics’ widespread diffusion in society we expect the capability and quality of decentralised governance to influence the overall governance and prevalence of AMR.

Estimation strategy

The purpose of our model is to understand how the basic configuration of the politico-administrative arrangement affects the prevalence of AMR across heterogeneous units (countries). Simple linear models fail to take such hierarchical features into account which can lead to misleading estimates and ultimately poorly informed suggestions for policy and future research (Beck & Katz, Citation1995, Citation2007). Instead, the choice often falls between either fixed and random effects models (cf. Gelman & Hill, Citation2007, p. 20), where the choice between the two involve trade-offs in bias and variance, and where sample size strongly influences the superiority of one over the other (Clark & Linzer, Citation2015).

Particularly in instances where independent variables are somewhat invariable, or ‘sluggish’ (Clark & Linzer, Citation2015, p. 403; Plümper & Troeger, Citation2007) over time and where the number of units and observations are limited, the choice of model should be carefully informed by the theoretical model under investigation. Our theoretical framework presupposes gradual or almost stationary within-unit variation and consists of 29 countries over nine years, suggesting that adopting a fixed-effect model would reduce important context and heterogeneity. Fixed effects models cannot handle the circumstance that time-invariant processes can affect time-varying variables (Bell & Jones, Citation2015, p. 139), which is an unreasonable assumption in many theories of higher-level institutional processes.

We therefore apply a random-effect panel model to fit the data. This is the suggested model by Clark and Linzer (Citation2015), given how our data is constituted. While fixed effects are ‘safe’ to use as they subtract context, random effects face the issue of omitted variable bias, i.e., that any other variable than the ones included are causing the variation in Y. Indeed, we acknowledge that our quantitative application has limited causal leverage to directly explain the prevalence of AMR. Determining the exact causality of AMR prevalence would require more nuanced identification strategies on the micro and meso-level. Our mixed methodology provides a plausible causal analysis between core variables and their underlying motivational bases according to key stakeholders in AMR governance. We thus stipulate that basic politico-administrative arrangements contain some causal weight over AMR; a conjecture informed by multiple interviews with AMR experts who concordantly emphasise the fundamental role of the state’s institutional relationships in dealing with antibiotics, and that these relationships vary depending on the administrative tradition.

Interviews

In our mixed methods approach, we therefore support the quantitative analysis with qualitative evidence generated from 46 semi-structured interviews with senior public servants and experts working with AMR policy in their respective country. All EU27 member states plus Norway and UK are included in the interview series. Due to travel restrictions in 2021 and 2022 the interviews were conducted digitally. The interviews aimed at generating nuanced and informed evidence on politico-administrative relationships and institutional arrangements and to support explanatory analysis.

All interviews were recorded and transcribed manually. The data was subsequently compiled into a comparative companion with material from each country and interviewee. This material of approximately 150 pages was then assessed by the whole research team and extracted into central analytical themes related to AMR governance. This extraction was enabled by the standardised interview guide (see Appendix) used in data collection.

Explaining AMR prevalence in the EU

The procedure of grouping countries into four regional clusters was made with reference to our own collected data and to well-established analytical frameworks for comparing European public administrations (Peters, Citation2021). In the Appendix, we further demonstrate how the core variables employed yield strong regional clusters which motivate our comparative approach. The regional clusters are defined as the following: Scandinavia (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden); Western Europe (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and the UK); Southern Europe (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, and Spain); Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia). The main variables are illustrated in below.

and report on the potential effect of several institutional factors on the prevalence of E coli and MRSA. The first finding is that they are both negatively associated with executive capacity, meaning that AMR seems to thrive in contexts where governments have little capacity to govern. In the most basic univariate regression, one unit increase in executive capacity (ranging 1–10) yields a 19 percentage points decrease in E coli. The corresponding model for MRSA is not significant but nonetheless negative.

Table 1. Random effects panel regression model (E coli). Years: 2013–2021.

Table 2. Random effects panel regression model (MRSA) Years: 2013–2021.

When adding control variables in models 2 (respectively for and ), the same negative association persists. Interestingly, the relationship between executive capacity and MRSA is significant when we add control variables, suggesting that there is a suppressed relationship between the two. Model 2 in shows that executive capacity is significantly associated with MRSA when including antibiotic consumption, which means that the focal relationship is dependent on the variable.

Total consumption of antibiotics in community and hospitals is strongly significant in both models. Increasing one unit of consumption (DDD/1000 inhabitants) leads to an increase of E coli and MRSA with 2.1 and 3.6 percentages, respectively. Furthermore, as expected, corruption and GDP per capita are strongly associated with both variables. More control of corruption and more resources reduce the prevalence of AMR.

None of the decentralisation variables – i.e., local or regional government – yield any significant associations with AMR. However, the level of democracy is significant at the 0.01-level for the prevalence of E coli, suggesting a 2.9 percentage decrease when democracy is increased by 0.01 on a scale from 0-1. This might be related to differences in how these two bacteria proliferate in societies – and in turn how they are monitored and deliberated among the public. While E coli is a comparably common bacterium, typically acquired from food, and harmless in most cases, MRSA has fewer outbreaks in most European societies and is primarily transmitted within hospitals (Mulani et al., Citation2019). However, future studies should further investigate the relationship between various resistant bacteria and levels of democracy. In addition, the civil society index is significant in both models and predicts positive associations with AMR. In other words, a 0.01 increase in civil society means an increase of 2.14 and 1.48 percentages of E coli and MRSA, respectively.

These results lend support for the previously established relationship between institutional quality and the prevalence of AMR (cf. Collignon et al., Citation2018). Controlling for several variables and adopting a composite measure with elements that relate directly to the various politico-administrative arrangements in Europe, we have demonstrated that more capabilities to execute policies, to coordinate state actors, and to gather expertise in the policy process are significantly associated with AMR. We now turn to explain in more detail how this relationship is upheld by specific mechanisms inherent to the politico-administrative relationship in the ‘four worlds’.

The regional dimension

The four ‘worlds’ of administration we study are characterised by different institutional arrangements and relationships between the political and administrative levels in the public health sector. In this section, we use qualitative evidence to generate a deeper understanding of the institutional dimension of AMR work in these four regions of the EU. We discuss how the three variables mentioned earlier – institutional arrangements, administrative autonomy and politico-administrative relationships – play out in the different regions and how those patterns can be linked to regional performance in the AMR work. With that analysis in hand, we then integrate the quantitative and qualitative evidence to further probe the question about linkages between institutional variables and the prevalence of AMR in the EU member states.

Scandinavia

Institutional arrangements. The emblemic feature of public administration in the Scandinavian region is the long history of autonomous agencies (Peters, Citation2021). This applies particularly to Sweden and Finland and to a somewhat lesser degree to Denmark and Norway where ministerial control is more marked. Most notably in Finland and Sweden, agencies are line organisations responsible for the bulk of policy implementation and – in collaboration with regions and cities – public service delivery. In Sweden, autonomous agencies have a history over several centuries. Agencies are managerial in their modus operandi but embedded in a legalistic administrative culture (see Dahlström & Lapuente, Citation2022).

Alongside the formal institutional arrangements there are structures and processes in place to ensure horizontal and vertical coordination of AMR measures, such as the Danish National Antibiotic Council or ‘the coordinating mechanism against AMR’ in Sweden.

Administrative autonomy. The Scandinavian countries have the most extensive administrative autonomy of the four groups of countries. This pattern is even more present in the public health sector than across all policy areas. However, agencies are line organisations; they report to a parent department and are tasked with policy implementation. The agencies’ role in implementation is in part to oversee regional and local authorities’ service delivery.

Politico-administrative relationships. The degree of political control over the public service in the Scandinavian region has been fairly low in international comparison although it appears to have increased somewhat over the past decade as part of post-NPM administrative reform. In the public health sector, our interviewees state that elected officials tend to seek a dialogue with experts rather than imposing their preferences. Politicians are clearly involved in the AMR work although less knowledgeable than the experts which means that AMR measures are to a large extent driven by experts.

Western Europe

Institutional arrangements. Western Europe presents a somewhat diverse institutional setup. With the exception of the federal Germany and Belgium, this region displays more centralised government than the Scandinavian region with strong ministries supported by specialised agencies. While there is extensive administrative autonomy, agencies are less operative than their equivalents in the Scandinavian region. The point of gravity of policy making and implementation is clearly with the ministries while agencies and specialised institutes provide expertise and advice.

The more hierarchical governance of AMR in Western Europe compared to the Scandinavian region may help clarify tasks and responsibilities but it also exacerbates challenges related to horizontal coordination. In order to address this problem, Austria for instance has several working groups to coordinate across jurisdictional borders while France has an inter-ministerial committee. France also devotes significant effort to coordinate across different institutional levels. Smaller unitary states like Luxembourg and Ireland perform better in these respects than the federal Germany and Belgium. It is intriguing to note the widespread use of networks even in highly centralised like France. A French senior public servant and AMR expert stated in an interview: ‘Networks and coordinating committees become all the more important because of the centralized and hierarchical structure of the public sector and of the French society … You need networks to support the hierarchy’.

Administrative autonomy. Overall, the Western European EU member states are characterised by extensive administrative autonomy. The main difference between this region and the Scandinavian region is that there seems to be an expectancy in the more centralised Western region on the political leadership to initiate and drive issues and to interfere in the administration’s work if deemed necessary.

Politico-administrative relationships. While our interviewees describe the relationship between politicians and the public service mainly as a dialogue, it appears as if the political side of that dialogue carries more weight than the administrative side. Political interference raises fewer eyebrows in these countries than it would in the Scandinavian countries. That said, politicians appear to be engaged and keen to hear the experts’ views on AMR issues.

The level of political involvement in the AMR work varies across this region. The key observation here is whether the political presence actually promotes the AMR work. While that seems to be the case in general, some experts do suggest that a low level of political involvement might not always be a bad thing as it means that the experts’ suggestions will not be overruled (incidentally a sentiment shared with a Scandinavian interviewee).

Southern Europe

Institutional arrangements. The southern European states exhibit a number of similarities in their basic administrative-institutional arrangements (Di Mascio & Natalini, Citation2015; Kickert, Citation2011; Ongaro, Citation2009). These similarities typically refer to a centralised and hierarchical system of government, a dominance of legalism in the procedural norms of the administration, and of varying degrees of politicisation (Peters, Citation2021). Notwithstanding these similarities we must certainly acknowledge some degree of heterogeneity in the region. For instance, Malta and Cyprus are, except being relatively small and sparsely populated islands, often referred to as hybrid administrative systems with roots from several administrative traditions such as the Napoleonic, Anglo-Saxon and Eastern European (Camilleri, Citation2018, p. 728; Mallouppas & Stylianides, Citation2018, p. 152).

Despite the dominance of unitarism in these countries, they also comprise significant degrees of decentralisation. The most obvious example here is Spain, with its 17 autonomous regions responsible for a large share of the AMR governance. Similarly, Italy has a de facto system of regionalised healthcare, making AMR management partly dependent on the quality of regional government. Thus, as interviewees from both these countries maintain, much of the central government agencies’ roles refer to coordinating the regions. However, the issue of regionalism remains intact since, as one Spanish respondent claims, ‘there are currently little consequences for not prescribing according to [central] guidelines in the regions’. The same pattern is evident in Italy, where there ‘is not a strong commitment and a lack of training in antimicrobial stewardship in many hospitals’. Also, the central government agency Istituto Superiore di Sanità provides scientific assistance to the regions to implement actions, but, as the respondent claims, ‘the regions are not receiving much from the central government in terms of resources’.

Administrative autonomy. Administrative autonomy is not substantial in the Southern European states. Instead, hierarchical control defines the relationships within the bureaucracy and from the stable of political masters, leaving individual bureaucrats with little room for manoeuvre. Hence, bureaucratic action is more structured by the political mandate, at least de jure; in reality, patronage and other informal rules are also expectant to influence and shape political control.

A Portuguese respondent provides telling insights on the present issue. Since top-level politicians are the most dominant agenda-setting and authority-delegating actors, their prioritisation tends to follow the degree of issue urgency, thus undermining the relevance of more long-term issues like AMR. The respondent refers to this issue as a ‘universal problem’ in the relationship of politics and administration in Portugal.

Politico-administrative relationships. Although these countries are characteristically steered by political command, they do also comprise a fair share of policy dialogue and advice. As one respondent from Portugal maintains, ‘both political and technical [expert] drive is important, but the former perhaps more’, or even more pointedly in Malta where ‘there is a two-way street communication between agency and ministry with advice and signalling on an almost continuous basis’. Overall, experts and senior bureaucrats in these settings are expected to push the issue of AMR higher on the agenda, as the Maltese respondent argued: ‘scientists and experts need to drive AMR up on the agenda. It is up to them to push and convince politicians’.

Greece deserves special attention because of its insufficient administrative arrangements to manage AMR. Several interview respondents claim that it lacks basic coordination over AMR; that collected data is not being used by relevant authorities; that private hospitals refuse to participate; and that there is no list of tasks for involved authorities. There has, however, existed political engagement with good results in the establishment of professional networks. Nonetheless, these networks are ‘easily abandoned, and the expertise and training, as well as the infrastructure, were all lost’.

Central and Eastern Europe (CEE)

Institutional arrangements. In some ways this is the most heterogeneous of the four groups. While Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania share the Soviet Union legacy, which according to our interviewees still looms large, their administration does also share some features with the Scandinavian and West European countries. For instance, Estonia has implemented extensive New Public Management reform which is rather rare in this region (Dan & Pollitt, Citation2015; but see Drecshler & Randma-Liiv, Citation2016).

The institutional arrangement of the AMR sector in the CEE countries is dominated by powerful Ministries of Health or a similar jurisdiction. Ministries embody policy making as well as implementation. They are usually supported by an Institute of Public Health reporting to the Ministry and, when requested, advising on public health issues. However, institutes are not line organisations and thus only marginally involved in policy making or implementation. This, in turn, means that their funding is limited. Essentially all the AMR experts we have interviewed in this region voice a frustration with a lack of resources – staff, funding, surveillance capacity, lab facilities, etc. – to support their AMR work. Coupled with overall low levels of administrative autonomy (see below), this institutional arrangement thus offers experts less input on policy issues and less operative capacity, particularly compared to northern and western European countries.

Administrative autonomy. Given these institutional arrangements, administrative autonomy is rather curtailed in the CEE countries. In the AMR sector, institutes of public health harbour much of the AMR expertise but given the limited remit of the institution their capacity to act independently of the parent Ministry is very limited. Thus, the AMR experts’ perhaps only option to address AMR issues is to secure the Ministry’s attention, and resources, for the action that they believe should be implemented.

Politico-administrative relationships. The relationship between the political level and the AMR expertise mainly found in the public health institutes could best be described as political control. The lack of resources mentioned earlier is largely explained by a very low interest among the political leadership in AMR. ‘I do not think that the word “AMR” means anything to the current minister’, say an interviewee in one of the Baltic states; ‘there is no political leadership in the AMR field in Slovakia’, argues a Slovak senior AMR expert; and in Poland an AMR expert says that ‘the people in the Ministry of Health don’t understand the problem’. With only little variation, this pattern is found across all the CEE countries. Politicians ignore the AMR problem in part because it is not believed to be a vote-winning issue; in part because addressing it appropriately is costly; and in part because the payoff is long-term.

Perhaps the only thing that can stir CEE politicians’ interest in the AMR issues is communications from the EU, the ECDC or the WHO. Agency and institute staff across the region testify to the capacity of these transnational organisations to push politicians into action. Often, such action means contacting AMR experts for advice on how to respond to international communications or asking them to draft responses. Thus, an EU bureaucrat has far more influence on, say, a Slovak elected official than a Slovak AMR expert Table 3.

Table 3. Four worlds of public administration in the AMR sector.

Concluding discussion

The key finding in this article is that basic politico-administrative arrangements affect the prevalence of AMR in the European states. This association holds when controlling for several confounding variables such as antibiotic consumption, the level of democracy and control of corruption. 46 elite interviews with AMR national experts and senior civil servants in the EU member states support and contextualise those findings. In essence, respondents’ views of their specific domestic administrative challenges corroborate the macro analysis of administrative systems and traditions. Consequently, such classification corresponds with the prevalence of AMR, leaving us with intriguing patterns of four distinct ‘worlds’ of AMR governance in Europe.

We now need to elaborate the causal mechanism sustaining that association. Administrative autonomy appears to be integral to the impact of institutional arrangements on AMR performance. In the Scandinavian and West European regions, experts are based in line executive, autonomous agencies and can for the most part launch programmes they believe to be required, sometimes after an approving nod from the political leaders. Administrative autonomy is ensured by the institutional division between departments and agencies and Weberian norms of a separation of politics and administration. This extensive autonomy mitigates the effects of the low political salience of AMR since agency rests largely with experts in the civil service.

In the Southern European countries, administrative autonomy is more curtailed compared to the Scandinavian and West European EU member states. While line agencies are politically controlled, there is a dialogue between the administration and the political level. That said, the administration is not expected to design, let alone launch programmes without the approval by the political leadership. When administrative officials and their institutions are not expected to take initiatives and political leaders do not appear to be very concerned with AMR, dialogue cannot compensate for the dysfunctionality of the institutional politico-administrative interaction.

In the CEE countries, finally, AMR experts in public health institutes have very limited operative autonomy and resources to roll out what they believe to be appropriate measures to address the AMR problem. Such authority rests squarely with the Ministry. The problem there is that AMR has very low salience; politicians appear to be only moderately interested in addressing the problem. Thus, while experts cannot implement necessary programmes, the political leadership lacks the inclination to do so. The end result in the CEE countries is that programmes to curb antibiotics use and promote AMR stewardship in hospitals are few and far between. The causal mechanism rests on the combined outcome of institutional arrangements that are common in the Southern European and CEE countries and the low political salience of the AMR issue; those actors who want to act cannot while those who can will not.

Thus, the low salience of AMR becomes a problem when administrative autonomy is restricted. In systems where that autonomy is extensive, low salience may actually have some positive consequences as it opens up for administrative action designed by AMR experts in the administration (Carelli & Pierre, Citation2022). The combined effects of different degrees of autonomy thus impact the extent and direction of AMR work which, in turn, may contribute to the stronger performance of the Scandinavian and West European countries.

There are two caveats to this argument. First, we do not suggest that this pattern is the only explanation of the differences in AMR prevalence across the EU, or that it is even one of the most important factors; we only suggest that, as the empirical analysis show, institutional arrangements do make a difference and that the causal mechanism is related to different degrees of administrative and expert autonomy. Secondly, while it seems clear that the executive agencies in Scandinavian and Western Europe can use their autonomy to mitigate the effects of the low salience of AMR, we must also note that there are significant variations in the degree of autonomy both within these regions and between the regions. More research is required to fully uncover the causes of the different levels of performance in the AMR sector. Our findings indicate that many basic institutions inherited from the past continue to shape administrators’ latitude for action.

The issue of AMR offers several insights into contemporary European governance and how it can be created and sustained more broadly. Contrary to the common view of civil servants as mere executors of public policy, AMR politics and administration illustrate how the administrative level of government can take central positions in the domestic political process. For instance, it is intriguing to note that essentially all our respondents argue that senior civil servants and experts own much of the agency in the AMR sector, pushing politicians to take their part of the responsibility to arrest the development of AMR.

Concerning the crucial component of politicisation in the politico-administrative relationship, our findings yield three distinct variations; one in which politicisation appears to be virtually absent; one in which it induces or enables the public administration to act; and one where it enables politicians to control administrators to not act. Such ‘reversed politicisation’ questions current dichotomous notions of politicisation that merely embraces the (non-) existence of political control, and rather identifies that the purpose of politicisation is decisive for the nature of political control over the administration. We believe there is considerable potential in further investigating this issue in both conceptual and applied research designs.

We thus encourage future research to continuously examine the persistence and changeability of basic politico-administrative arrangements and how they shape the preconditions for governance over issues that are not directly related to politics and administration, but rather lurking in the background as a cause of the causes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (570.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their close reading of the paper and helpful comments. We also thank our research team mates Elina Lampi, Josefine Ogne and Björn Rönnerstrand for comments on previous drafts of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jon Pierre

Jon Pierre is Professor Emeritus in Political Science at the University of Gothenburg.

Daniel Carelli

Daniel Carelli is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the University of Gothenburg.

B. Guy Peters

B. Guy Peters is Maurice Falk Professor of American Government at the University of Pittsburgh.

References

- Aberbach, J. D., Putnam, R. D., & Rockman, B. A. (1981). Bureaucrats and politicians in western democracies. Harvard University Press.

- Anwar, M., Iqbal, Q., & Saleem, F. (2020). Improper disposal of unused antibiotics: An often overlooked driver of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy, 18(8), 697–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2020.1754797

- Bach, T., Niklasson, B., & Painter, M. (2012). The role of agencies in policy-making. Policy and Society, 31(3), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2012.07.001

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082979

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (2007). Random coefficient models for time-series-cross-section data: Monte Carlo experiments. Political Analysis, 15(2), 182–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl001

- Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2015). Explaining fixed effects: Random effects modeling of time-series cross-sectional and panel data. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(1), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2014.7

- Cabello, F. C., Godfrey, H. P., Buschmann, A. H., & Dölz, H. J. (2016). Aquaculture as yet another environmental gateway to the development and globalisation of antimicrobial resistance. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(7), E127–E133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00100-6

- Camilleri, E. (2018). Malta. Public administration characteristics and performance in EU 28. European Commission.

- Carelli, D., & Peters, B. G. (Forthcoming). Administrative law and bureaucratic autonomy in a comparative European perspective. In K.-P. Sommermann, A. Krzywón, & C. Fraenkel-Haeberle (Eds.), The civil service in Europe: A research companion. Routledge.

- Carelli, D., & Pierre, J. (2022). When the cat is away: How institutional autonomy, low salience, and issue complexity shape administrative behavior. Public Administration, https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12912

- Carpenter, D. P. (2001). The forging of bureaucratic autonomy: Reputation, networks and policy innovation in executive agencies. Princeton University Press.

- Charani, E., Castro-Sanchez, E., Sevdalis, N., Kyratsis, Y., Drumright, L., Shah, N., & Holmes, A. (2013). Understanding the determinants of antimicrobial prescribing within hospitals: The role of ‘prescribing etiquette’. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 57(2), 188. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit212

- Clark, T., & Linzer, D. (2015). Should I use fixed or random effects? Political Science Research and Methods, 3(2), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2014.32

- Collignon, P., Athukorala, P., Senanayake, S., & Khan, F. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance: The major contribution of poor governance and corruption to this growing problem. PloS One, 10(3), E0116746. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116746

- Collignon, P., Beggs, J., Walsh, T., Gandra, S., & Laxminarayan, R. (2018). Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: A univariate and multivariable analysis. The Lancet: Planetary Health, 2(9), E398–E405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30186-4

- Dahlström, C., & Lapuente, V. (2022). Comparative bureaucratic politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 25(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-102543

- Dan, S., & Pollitt, C. (2015). NPM can work: An optimistic review of the impact of new public management reforms in central and Eastern Europe. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1305–1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.908662

- Dancer, S. (2014). Controlling hospital-acquired infection: Focus on the role of the environment and New technologies for decontamination. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 27(4), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00020-14

- Davey, P. (2015). The 2015 garrod lecture: Why is improvement difficult? Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 70(11), 2931–2944. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkv214

- Davis, M., Whittaker, A., Lindgren, M., Djerf-Pierre, M., Manderson, L., & Flowers, P. (2018). Understanding media publics and the antimicrobial resistance crisis. Global Public Health, 13(9), 1158–1168. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1336248

- Della Porta, D., & Vannucci, A. (2012). The hidden order of corruption: An institutional approach. Ashgate.

- Di Mascio, F., & Natalini, A. (2015). Fiscal retrenchment in Southern Europe: Changing patterns of public management in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain. Public Management Review, 17(1), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.790275

- Drecshler, W., & Randma-Liiv, T. (2016). In some central and eastern European countries, some NPM tools May sometime work: A reply to Dan and Pollitt’s ‘NPM can work’. Public Management Review, 18(10), 1559–1565. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1114137

- Ebert, S. (2007). Factors contributing to excessive antimicrobial prescribing. Pharmacotherapy, 27(1), 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.27.10part2.126S

- EDC. (2022). Antimicrobial resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net) - annual epidemiological report 2021. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Stockholm: ECDC.

- Emmenegger, P. (2021). Agency in historical institutionalism: Coalitional work in the creation, maintenance and change of institutions. Theory and Society, 50(4), 607–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-021-09433-5

- Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multi-level/hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, P. A. (1986). Governing the economy: The politics of state intervention in Britain and France. Oxford University Press.

- Helmke, G., & Levitsky, S. (2004). Informal institutions and comparative politics: A research agenda. Perspectives on Politics, 2(4), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592704040472

- Hustedt, T. (2018). Policy design and policy advisory systems. In M. Howlett, & I. Mukherjee (Eds.), Routledge handbook of policy design (pp. 201–211). Routledge.

- Kickert, W. (2011). Distinctiveness of administrative reform in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain: Common characteristics of context, administrations and reforms. Public Administration, 89(3), 801–818. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01862.x

- Larsson, J. D. G. (2014). Pollution from drug manufacturing: Review and perspectives. Philos, 369(1656), 20130571.

- Larsson, J. D. G., & Flach, C. (2022). Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 20(5), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00649-x

- Mallouppas, A., & Stylianides, T. (2018). Cyprus. Public administration characteristics and performance in EU28. European Commission.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions. Free Press.

- Martínez, J. L., & Baquero, F. (2014). Emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance: Setting a parameter space. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences, 119(2), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009734.2014.901444

- Mulani, M. S., Kamble, E. E., Kumkar, S. N., Tawre, M. S., & Pardesi, K. R. (2019). Emerging strategies to combat ESKAPE pathogens in the era of antimicrobial resistance: A review. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00539

- Murray, C., Ikuta, K., Swetschinski, L., Aguilar, G., Gray, A., Han, C., Bisignano, C., Rao, P., Wool, E., Johnson, S., Chipeta, M., Fell, F., Hackett, S., Haines-Woodhouse, G., Hamadani, B., Kumuran, E., McManigal, B., Agarwal, R., Akech, S., … Naghavi, M. (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. The Lancet (British Edition), 399(10325), 629–655.

- O’neill, J. (2014). Antimicrobial resistance: Tackling a crisis for the wealth of nations. Review on antimicrobial resistance. www.amr-review.org (Retrieved 2023-09-02).

- Ongaro, E. (2009). Public management reform and modernization: Trajectories of administrative change in Italy, France, Greece, Portugal and Spain. Edward Elgar.

- Overeem, P. (2005). The value of the dichotomy: Politics, administration, and the political neutrality of administrators. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 27(2), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2005.11029490

- Peters, B. G. (2018). The politics of bureaucracy (7th ed.). Routledge.

- Peters, B. G. (2021). Administrative traditions: Understanding the roots of contemporary administrative behavior. Oxford University Press.

- Plümper, T., & Troeger, V. E. (2007). Efficient estimation of time-invariant and rarely changing variables in finite sample panel analyses with unit fixed effects. Political Analysis, 15(2), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpm002

- Pollitt, C. (Ed.) (2013). Context in public policy and management. Edward Elgar.

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2017). Public management reform. Oxford University Press.

- Pollitt, C., Talbot, C., Caulfield, J., & Smullen, A. (2004). Agencies: How governments do things through semi-autonomous organizations. Palgrave.

- Rönnerstrand, B., & Lapuente, V. (2017). Corruption and the use of antibiotics in regions of Europe. Health Policy, 121(3), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.12.010

- Rothstein, B. (2011). The quality of government: Corruption, social trust, and inequality in international perspective. University of Chicago Press.

- Rugge, F. (2012). Administrative traditions in Western Europe. In B. G. Peters, & J. Pierre (Eds.), Sage handbook of public administration (2nd ed, pp. 228–240). Sage.

- Scott, H. M., Acuff, G., Bergeron, G., Bourassa, M. W., Simjee, S., & Singer, R. S. (2019). Antimicrobial resistance in a one health context: Exploring complexities, seeking solutions, and communicating risks. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1441(1), 3–7.

- Thelen, K. (2004). How institutions evolve: The political economy of skills in Germany, britain, the United States, and Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- Thelen, K., & Steinmo, S. (1992). Historical institutionalism in comparative politics. In S. Steinmo, K. Thelen, & F. Longstreth (Eds.), Structuring politics (pp. 1–33). Cambridge University Press.

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure and process. Oxford University Press.

- Verhoest, K., Peters, B. G., Bouckaert, G., & Verschuere, B. (2004). The study of organisational autonomy: A conceptual review. Public Administration and Development, 24(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.316

- Verhoest, K., Roness, P., Verschuere, B., Rubecksen, K., & MacCarthaigh, M. (2010). Autonomy and control of state agencies: Comparing states and agencies. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weaver, R. K., & Rockman, B. A. (Eds.). (1993). Do institutions matter?: Government capabilities in the United States and abroad. The Brookings Institution.

- WHO. (2015). Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. www.who.int (Retrieved 2023-09-02).