?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article advances the literature on the spatial patterns of EU support by arguing that the relationship between regional inequality and EU trust is not linear. We posit that, to fully understand this relationship, we should systematically investigate three dimensions of regional inequality, i.e., regional wealth status, regional wealth growth, and regional wealth growth at different levels of wealth status. Using individual-level survey data for EU27 countries and the UK from 11 Eurobarometer waves (2015–2019), we show that a non-linear association exists whereby poor and rich European regions tend to trust the EU more compared to middle-income regions, and that within-region over-time growth is associated with higher levels of EU trust. We demonstrate that the association between growth and EU trust is more pronounced among poor and middle-income regions compared to rich regions. Our findings have implications about the nature of public Euroscepticism and the ways in which to address it.

Introduction

Globalisation and the transformation of global capitalism from industrialisation to the knowledge and innovation economy have created winners and losers not only at the individual level, but also at the subnational regional level (Broz et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2021). In Europe, regions have experienced different socio-economic conditions, and have different levels of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), employment, and productivity (e.g., Dijkstra et al., Citation2020; MacKinnon et al., Citation2022; McCann, Citation2020; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). Indeed, regional economic context varies substantially across European countries and over time (Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023). On the one hand, some regions have experienced concentrated high-wage high-skill employment, better quality of public services, and overall better prospects for inter-generational mobility. These regions have been able to prosper and adjust in the knowledge economy. On the other hand, other regions have felt the negative effects of globalisation, deindustrialisation, and demographic shrinkage. They have faced more long-term pressures resulting from the decline of manufacturing employment, are more exposed to international economy, and are more vulnerable to trade shocks, e.g., to imports from China or low-income countries (Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018; Nicoli et al., Citation2022). These regions have become disconnected from knowledge and innovation, and tend to have lower levels of pay, skill, and educational achievement (MacKinnon et al., Citation2022). Such (poor-er) regions tend to be caught in income traps (Martin et al., Citation2021; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018).

The European Union (EU), which is often viewed as a case of regional globalisation, has sought to address this regional economic heterogeneity through structural and cohesion funds (Chalmers & Dellmuth, Citation2015; Rodríguez-Pose & Dijkstra, Citation2021). Yet, EU funds have also shaped regional inequalities and contributed to a widening gap between EU regions (e.g., Heidenreich & Wunder, Citation2007). Regional wealth differentials tend to account for Eurosceptic voting and institutional distrust (Díaz-Lanchas et al., Citation2021; Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021; Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023; Schraff, Citation2019). While there is strong longitudinal variation in the relationship between subnational economic conditions and support for European integration (Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023), overall, the literature suggests that in the period following the financial crisis citizens living in lagging behind regions are more likely to express EU discontent (Díaz-Lanchas et al., Citation2021; Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021; Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023). Individuals living in communities negatively affected by globalisation translate their frustration with their socioeconomic disadvantage into support for Eurosceptic parties and EU distrust (Lenzi & Perucca, Citation2021). In sum, this is the manifestation of the ‘revenge of the places that do not matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). However, this overlooks the fact that EU discontent has also been observed among rich (Dijkstra et al., Citation2020) as well as those middle-income regions which receive insufficient compensation from the EU (Schraff, Citation2019).

To account for this paradox, this article advances the literature on the spatial patterns of EU support by arguing that the relationship between regional inequalities and EU discontent is more nuanced and its non-linearity needs to be accounted for. By considering the relationship as linear whereby a change in a region’s wealth yields a corresponding increase in EU support, extant research has paid less attention to a key type of region, i.e., the middle-income region, where – as we show below – EU institutional distrust is concentrated and is higher compared to poor or rich regions. Using individual-level survey data for EU27 countries and the UK from 11 Eurobarometer waves between 2015 and 2019, we take into consideration variation across time, regions, and individuals. We posit that to fully understand the relationship between regional economic circumstances and EU trust we should systematically investigate three dimensions of regional inequality, i.e., regional wealth status, regional wealth growth, and regional wealth growth at different levels of wealth status. We show that, first, a non-linear association exists whereby poor and rich European regions tend to trust the EU more compared to middle-income European regions. Second, we propose that individuals compare their region to its own past and potential future trajectory; and demonstrate that within-region over-time growth is associated with higher levels of EU trust. Third, we show that the association between growth and EU trust is much more pronounced among poor and middle-income regions compared to rich regions.

By considering the subnational foundations of international politics, this article yields substantial theoretical and empirical insights that account for the complex relationship between economic inequality and EU support. First, we go beyond extant literature (Díaz-Lanchas et al., Citation2021; Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021; Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023) by focusing on the non-linear relationship between wealth levels and EU trust. In so doing, we highlight the importance of uncovering the dynamics of EU support in middle-income regions which are often found in a regional development trap and lack EU funding. This suggests that we need to revisit the commonly-held distinction between ‘losers’ (poor) and ‘winners’ (rich) of globalisation, which conceals a third type of region in which institutional distrust is more pronounced. Second, we examine regional inequality not only in ‘static’ terms related to wealth status, but also in ‘dynamic’ terms, accounting for the over-time economic trajectory within each region. We thus demonstrate that it is the prospects associated with wealth growth, such as economic opportunity, upward economic mobility and economic status improvement that matter in terms of EU trust. Third, by considering growth trajectories at different levels of wealth status, we show that the ability to retain a level of economic dynamism, especially in poor and middle-income regions becomes translated into EU support. This suggests that the mechanism behind the link between regional inequalities and political distrust is more complex than the ‘revenge of the places that do not matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018; see also MacKinnon et al., Citation2022; Martin et al., Citation2021).

Taken together, our findings establish the importance of examining EU trust through these three different dimensions of regional inequality. Focusing on the subnational context allows us to integrate economic and cue-taking approaches to the analysis of public support for European integration (for a review, see Hobolt & De Vries, Citation2016). Citizens make sense of politics through their lived experiences. Due to its proximity, when affected economically, the regional context provides a very strong cue to individuals that allows us to better understand patterns of trust in the EU. By implication, we suggest that theories of EU attitudes that rely on heuristics (see Anderson, Citation1998; De Vries, Citation2018; Ejrnæs & Jensen, Citation2019; Ejrnæs et al., Citationin press) should not only differentiate between different levels of wealth at the country level (see Talving & Vasilopoulou, Citation2021), but also between different levels of regional economic development. This is because the dynamics of support for the EU at the subnational level are fundamentally different. Our findings therefore have implications about the nature of public Euroscepticism and the ways in which to address it.

The regional wealth divide and EU trust

How does regional economic inequality influence EU trust? In this article, we start from the premise that citizens make sense of politics through their lived experiences and take cues from their surrounding community (cf. De Vries, Citation2018; Ejrnæs & Jensen, Citation2019; Talving & Vasilopoulou, Citation2021 on national-level heuristics). Spatial context can act as an information shortcut or heuristic device (Cho & Rudolph, Citation2008). People who live in the same place tend to have common experiences, which shape their political opinions and behaviours (Maxwell, Citation2019). Community experiences, social interactions, and everyday casual observations of their surroundings inform their economic cost–benefit calculations and political opinions (Ethington & McDaniel, Citation2007). Citizens tend to be responsive to their collective economic circumstances. These localised economic experiences give rise to different narratives through the prism of which individuals make sense of the political world (Gartzou-Katsouyanni et al., Citation2022).

One of the EU’s priorities is regional development. Its competences over subnational conditions have increased over time with the implementation of a series of regional spending and investment policies. For example, the European Structural and Investment Funds seek to address regional economic inequalities by strengthening the economic, social, and territorial cohesion in EU. Research suggests that this policy has yielded positive economic growth returns of investment in poor EU regions (for a discussion, see Rodríguez-Pose & Dijkstra, Citation2021). However, EU structural funds have also been criticised for being allocated following party-political considerations or for offering insufficient compensation, thus often widening regional inequalities (Bouvet & Dall’erba, Citation2010; Dellmuth, Citation2011; Dellmuth et al., Citation2017; Heidenreich & Wunder, Citation2007; Schraff, Citation2019). Using evidence from household-level income data for more than 2.4 million survey respondents in Europe during 1989-2017, Lang et al. (Citation2022) find that the EU’s cohesion policy tends to primarily improve incomes of rich and highly skilled households, rather than improving regional economic disparities.

Regional economic inequality has implications on individuals’ material and psychological well-being (Cramer Walsh, Citation2012; Hochschild, Citation2016; Munis, Citation2022). The spatial unevenness of development across EU regions can give rise to feelings of economic insecurity and regional resentment related to wealth differentials. Material well-being can also be a source of psychological well-being. Changes to regional living standards can be associated with concomitant psychological processes related to different prospects of economic opportunity. These spatial economic imbalances become translated into different patterns of trust in the EU. To account for the relationship between EU trust and regional inequality, we systematically examine three dimensions of spatial inequality, i.e., regional wealth status, regional wealth growth, and regional wealth growth trajectories at different levels of wealth status.

We commence by examining the ‘static’ relationship between regional economic wealth status and EU trust. Utilitarian models of EU support suggest that both poor and rich regions would express EU support, yet for different reasons. Both types of regions enjoy benefits from European integration. On the one hand, assuming that the EU is associated with economic prosperity, individuals residing in rich regions – the winners of globalisation and Europeanisation – are more likely to express trust in the EU. Prosperity is associated with improved future expectations (Díaz-Lanchas et al., Citation2021), and citizens reward institutions for positive economic outcomes (e.g., Eichenberg & Dalton, Citation1993). Indeed, following the financial crisis, citizens are more likely to express EU support in wealthier regions (Dijkstra et al., Citation2020; Martin et al., Citation2021; Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018, see also Dellmuth, Citationforthcoming). On the other hand, poor regions (similar to poorer member states) are more likely to benefit from EU compensation mechanisms, for example EU regional funds, which suggests that they are also likely to support the EU (Anderson & Reichert, Citation1995; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2005). EU funding can – partially – mitigate economic disparities and the negative effects of globalisation, and regional EU funding tends to be associated with EU support (Chalmers & Dellmuth, Citation2015). Based on analyses at the electoral district level, for example, Rodríguez-Pose and Dijkstra (Citation2021) show that EU regional investment reduces the share of voters for Eurosceptic parties. This suggests that people living in both rich and poor regions are likely to support the EU, albeit for different reasons. While individuals residing in rich regions are likely to trust the EU due to positive economic outcome evaluations, those living in poor regions are likely to trust the EU due to the potential benefits from EU compensation mechanisms.

This theoretical framework suggests that the relationship between regional wealth and EU trust in not linear whereby a change in a region’s wealth yields a corresponding increase in EU support. We posit that the relationship between EU trust and regional wealth status is curvilinear. The differentiation between rich and poor regions also serves to highlight the relevance of a third type of European region, i.e., the middle-income region. Our intuition is that EU trust will be low in middle-income regions, and comparatively lower than both in rich and poor regions. Here we draw upon economic geography literature, which proposes that middle-income regions often experience stagnation and are found in a regional development trap. Such regions ‘have experienced lengthy periods of low growth, weak productivity increases, low employment creation, or even employment loss’ and face significant challenges to (re-)gain their economic dynamism (Diemer et al., Citation2022, p. 788). In addition, Schraff (Citation2019) shows that middle-income regions tend to be cut-off from the bulk of EU funding. Therefore, despite being in a development trap, there is insufficient compensation from the EU that would allow moving up to a higher-income level.

Economic insecurity generates psychological reactions – specifically anger – that spur discontent (Rhodes-Purdy et al., Citation2021). Stagnation at the middle-income level becomes translated into lack of opportunity for improvement and ultimately into a feeling of regional resentment, i.e., a ‘sentiment that one’s region is not treated well by those from other regions, whether these are elites or citizens’ (De Lange et al., Citation2023, p. 2). This ties in with literature that suggests that it is not objective economic hardship per se, e.g., living in an objectively poor region, that entails disillusionment with the status quo. Besides, poor regions are more likely to benefit from EU structural funds (Schraff, Citation2019). Rather, it is relative deprivation, concerns about maintenance of wealth, and the risk of experiencing economic adversity (often with insufficient compensation) that may spur political discontent (e.g., for the individual level, see Im et al., Citation2019; Kurer, Citation2020). This suggests that the relationship between regional wealth status and support for the EU is not linear. We hence hypothesise:

H1: Poor and rich European regions tend to trust the EU more compared to middle-income European regions.

Extant research has focused on regional comparisons to the richest region in the country (Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021), the mean regional growth of a country (Díaz-Lanchas et al., Citation2021), or compared to a benchmark set by the GDP average of EU-10 higher-income established democracies (Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023). This raises the question as to which region citizens use as a reference point to compare their own situation against (see also, Schraff & Pontusson, Citationforthcoming). In this article, we assume that individuals consider the (dis-)advantages of a place relative to its own trajectory. Citizens evaluate their region to its own past and potential future direction, and this comparison of utility is much more relatable and directly links to one’s everyday experiences. We propose that larger within-region over-time growth is associated with higher levels of EU trust. Since there is very little decline in growth (most regions grow over time), we distinguish in the analysis between no/small, moderate, and large growth.

As above with H1, growth has implications for material and psychological well-being. Economically, the effects of larger upward economic movement are visible and tangible at the community level, for example through public services improvement, better-quality access to facilities, increasing innovation and learning, a better prospect of improving skills and education, and becoming more competitive in terms of attracting investment. Communities that experience a larger upward trajectory can also provide a source of psychological well-being. People who live in growth regions tend to experience better economic opportunities and have different views compared to those who live in declining or stagnating regions (McCann, Citation2020, p. 257).

Therefore, in contrast to individuals who live in areas that experience decline and express feelings of resentment and a general lack of political engagement (Broz et al., Citation2021; De Lange et al., Citation2023; Díaz-Lanchas et al., Citation2021; Florida, Citation2021; Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021; MacKinnon et al., Citation2022; Rodríguez-Pose et al., Citation2023), residents of up-and-coming regions should be experiencing hope and enthusiasm at the prospect of economic opportunity and welfare improvement. This is in line with literature that finds an association between sustained economic growth in a region and EU support (Lenzi & Perucca, Citation2021; López-Bazo, Citation2021), especially within Europe’s catch-up regions in the post-recession period (Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023). In terms of Eurosceptic voting, Dijkstra et al. (Citation2020, p. 747) demonstrate that ‘places that have experienced long-term above-average economic growth tend to vote less for parties opposed to European integration than those that have undergone relative economic decline’. Therefore, we go beyond examining wealth status in static terms and focus on the dynamic aspect of wealth growth. We hypothesise that:

H2: Larger regional economic growth is associated with higher levels of trust in the EU.

Our logic here also follows the economic-psychological mechanism. Economically, an upward trajectory in regions that need it most is likely to make a much more significant, visible, and potentially faster difference in the immediate living context, for example in terms of infrastructure, services, human capital, competitiveness, employment, and innovation. In other words, compared to rich regions, the translation between regional economic growth and prosperity on the ground is quicker and more tangible (see also Schraff, Citation2019 who finds that those poor areas that are heavily funded from the EU are less Eurosceptic).

Psychologically, economic dynamism relative to past performance within these poor and middle-income regions may be interpreted as decreasing the risk of stagnation and/or offering a pathway out of the regional development trap. This sentiment of transitioning from a low to middle and from a middle- to high-income region increases expectations of opportunity and a sentiment of hope and enthusiasm for better prospects. Retaining a level of economic dynamism despite the fact that they do not live in wealthy regions suggests that there is a ‘way out’, which bolsters opportunities for upward mobility and economic status improvement, and as such EU support. We therefore hypothesise:

H3: EU trust is likely to be higher among poorer and middle-income European regions that are experiencing growth compared to rich regions that are experiencing growth.

Data and methods

The analysis focuses on variation across regions. We test our hypotheses using individual-level survey data for EU27 countries and the United Kingdom (UK) from 11 Standard Eurobarometer waves between 2015 and 2019. The period accounts for the recovery phase from the 2008 economic and financial crisis in most EU countries, with relatively similar and favourable conditions (Lenzi & Perucca, Citation2021). It also covers the 2015 European migrant crisis and the 2016 UK EU membership referendum, but not the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 or the UK’s official exit from the EU on 31 January 2020. The standard Eurobarometer survey follows a multi-stage national probability sample design. With approximately 1,000 randomly selected respondents from each country per survey wave, our final dataset comprises 305,262 cases. The full list of survey waves and variables included in the analysis appears in Table A in the Appendix.

The dependent variable is Trust in the EU, measured in the Eurobarometer using a dichotomous question, asking whether respondents tend not to trust (0) or tend to trust (1) the EU. The trust indicator measures the concept of diffuse support for the EU (e.g., Gabel, Citation1998) and has been shown to be robust to alternative operationalisations (e.g., Armingeon & Ceka, Citation2014; Harteveld et al., Citation2013). ‘Don’t knows’ are excluded from the analysis.

To test the relationship between EU trust and regional economic conditions, we include an annual measure of regional gross domestic product (GDP) in purchasing power standard (PPS) per inhabitant, retrieved from the Eurostat database and, where needed, amended using data from national statistics offices.Footnote1 Regional GDP is a proxy for standard of living, including for overall performance of the local economy in terms of incomes, profits, rents, and wealth (McCann, Citation2020, p. 258). GDP expressed in PPS is intended for geographical comparisons as it eliminates the differences in price levels between regions. Calculations on a per inhabitant basis allow for the comparison of regions that are significantly different in absolute size. Altogether, GDP per inhabitant in PPS is the key variable for determining the eligibility of regions in the framework of the EU's structural policy.Footnote2

We matched the GDP data with survey data using variables in Eurobarometer indicating either NUTS 1 or NUTS 2 levels, depending on the regional GDP data availability.Footnote3 Where GDP at NUTS2 levels was not accessible, the GDP value for NUTS1 is used instead. We use the original GDP variable to measure regional wealth level (H1, H3) and calculate relative economic change from to measure wealth improvement (H2, H3) (see also Dijkstra et al., Citation2020; Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023). Wealth levels reflect long-term economic fortunes across regions and recent changes refer to benefits that regions have experienced over the past few years (Adler & Ansell, Citation2020). A 5-year change was chosen instead of annual growth rate to filter out noise from short-term fluctuations (Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023), and to capture significant changes that people have noticed and can still remember (Lechler, Citation2019). We also test the robustness of our results using shorter growth time lags (Figures D (t-3) and E (t-1) in the Appendix). Both wealth-related variables are modelled as curvilinear, i.e., using their respective squared terms, since we expect the relationships to be non-linear.

Our models control for a list of individual-level indicators, including two well-established predictors of EU attitudes: domestic political support (e.g., Armingeon & Ceka, Citation2014; Harteveld et al., Citation2013) and economic perceptions (e.g., McLaren, Citation2006; Talving & Vasilopoulou, Citation2021). Domestic political trust is measured through trust in the national government (0 = tend not to trust, 1 = tend to trust). To measure economic perceptions, we use the Eurobarometer question asking respondents their expectations for the next twelve months when it comes to the economic situation of their country (1 = worse, 2 = same, 3 = better). The literature suggests that national identity is also an important driver of attitudes towards the EU (e.g., Carey, Citation2002; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018). To measure the concept of identity, the Eurobarometer survey uses different questions that are inconsistent across survey waves. We selected the question that appears most frequently (in 8 out of 11 waves covered in our study) and that asks respondents to indicate how attached they feel to their country. The variable is recoded as 0 for respondents who feel attached to their country and as 1 for those who do not. To maximise the number of waves covered in the analysis, we first run all models without the identity variable and then repeat the exercise using models that include the identity question (Models 1a-5a, Table E in the Appendix). We also control for other conventional determinants of political trust (e.g., Hooghe & Marks, Citation2005), including respondents’ level of education (number of years spent in full-time education; recoded into 0 = no full-time education, 1 = up to 15 years, 2 = 16-19 years, 3 = 20 years or more), occupational status (0 = not working, 1 = working), ideological leaning (0 = left, 10 = right), and demographic characteristics (age, gender). At the national level, we control for GDP per capita in PPS, provided by Eurostat (e.g., Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021). For the descriptive overview of all variables, see Table B in the Appendix.

Due to the dichotomous nature of our dependent variable, we use logistic regression modelling. The analysis employs clustered robust standard errors to allow for correlation within regions, with individuals (n = 305,262) nested in regions (n = 200). Year fixed effects are included to account for unobserved heterogeneity over time. We also run robustness tests using multilevel models where individuals are nested in region-years which are nested in country-years (Models 1b-5b in Table E in the Appendix).

Results

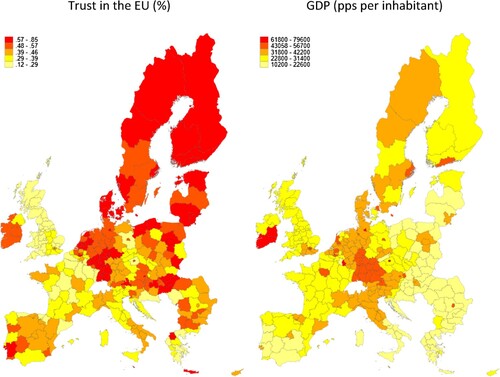

We begin with the descriptive overview of our key variables and exploring their regional patterns. In the overall sample, 48 per cent of respondents tended to trust the EU on average. Levels of EU trust have been relatively stable over time, being lowest at 44 per cent at the onset of the European migrant crisis in 2015 and highest at 51 per cent at the height of Brexit negotiations in 2018. In contrast to institutional trust, regional economic circumstances demonstrate a continuous upward trend over time. With the overall sample mean of 28,805 PPS per inhabitant, average regional GDP grew from 27,260 in 2015 to 31,117 in 2019. Both indicators, however, demonstrate vast spatial differences. plots their regional distribution in 2019, the latest time point in the period under observation. Trust in the EU varied in 2019 from 12 per cent in the Yorkshire and the Humber region in the UK to 85 per cent in Salzburg in Austria. The lowest average GDP in 2019 was recorded in the North-western region of Bulgaria (10,200 PPS per inhabitant) and the highest in Luxembourg (79,600 PPS per inhabitant). Descriptive data also show that regional economic status is not necessarily linearly linked to institutional EU trust. For example, trust levels during the observed time period are relatively low in some above average wealthy European regions, such as Carinthia in Austria (18 per cent on average) or Saxony in Germany (26 per cent), and high in some relatively poor regions like Southwestern Bulgaria (63 per cent) or South-West Oltenia in Romania (65 per cent).

Figure 1. Regional distribution of the dependent and independent variables. Source: Eurobarometer waves, 2019. Notes: For countries where data on NUTS2 level were not accessible, NUTS1 was used instead.

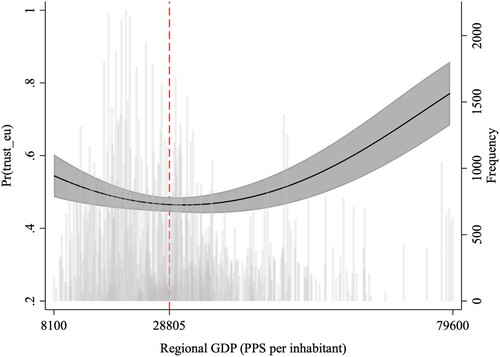

To test H1, we regress trust in the EU on regional GDP in PPS per capita. Control variables are also included (Model 1 in Table C in the Appendix). The results in demonstrate that the relationship between EU trust and regional wealth status is non-linear: EU trust levels are highest among affluent regions of Europe, remain more modest in poor regions, but are lowest in middle-income regions. The predicted probability of trusting the EU is 78 per cent for individuals from the region with the highest income and 54 per cent for people from the region with the lowest income in the sample (Luxembourg in 2019 and North-western Bulgaria in 2015, respectively). However, middle-income regions lag behind, with only 47 per cent likelihood of trusting the EU for mean regional wealth levels (red dashed line in ). Differences between all three regions are statistically significant at the 5 per cent level (Χ2 = 0.00). Results remain robust when controlling for national identity or using multilevel modelling (Table E in the Appendix).

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of trust in the EU, at different levels of regional wealth status. Notes: The histogram reflects the frequency distribution of regional wealth. Source: Eurobarometer waves, 2015—2019.

The findings are similar if, instead of using the continuous income variable, we look at differences between wealth groups. For this, we split the sample into three largely equally sized groups based on the frequency distributions of regional GDP. The first third of respondents, i.e., those who live in regions with the lowest GDP per inhabitant, were assigned into the category ‘poor’, the second third into ‘middle-income’, and the final third into ‘wealthy’ regions. The results indicate that individuals living in middle-income regions are significantly less likely to trust the EU than those residing in poorer regions (Model 2 in Table C and Figure A in the Appendix). Although the differences between the middle-income and wealthy regions do not appear statistically significant at the 0.05 level, this exercise confirms that the association between regional wealth status and EU trust is non-linear. Taken together, the analysis largely supports H1. Europeans from economically advantaged and disadvantaged regions tend to trust the EU more compared to those living in middle-income regions, although the extent of these differences depends on how we operationalise the regions’ socioeconomic position.

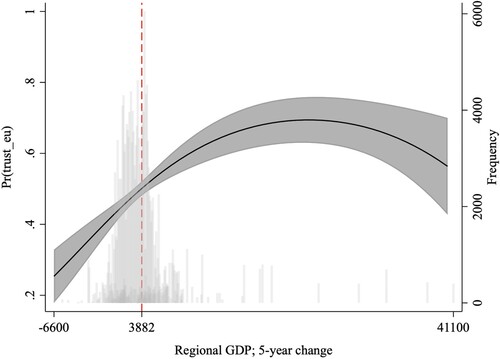

Our H2 posits that trust in the EU rises with regional economic growth. To test this, we run a model of EU trust where the independent variable is a 5-year change in regional GDP. Results provide support for our expectation (Model 3 in Table C in the Appendix). As shown in , EU trust levels generally rise as regional wealth grows. The association is not linear, although the non-linearity seems to be driven by the low number of observations towards the upper end of the scale (see histogram in ).Footnote4 Highest trust probabilities are recorded in regions that have witnessed moderate or large wealth increase, although they start declining again in regions with very large wealth growth, potentially indicating a ceiling effect. More specifically, the probability of trusting the EU is 25 per cent for the region that during the observed period went through the largest negative change in wealth (Groningen in the Netherlands in 2018) and 55 per cent for the region that witnessed the largest positive change (Southern Region of Ireland in 2019). For a region with mean growth (red dashed line in ), the likelihood of trusting the EU is 50 per cent. The latter region is not statistically different from regions with the largest growth (Χ2 = 0.51). Results are robust to controlling for national identity and using multilevel modelling (Table E in the Appendix).

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of trust in the EU, at different levels of regional wealth growth. Notes: The histogram reflects the frequency distribution of regional wealth growth. Source: Eurobarometer waves, 2015—2019.

Again, we check the validity of these results by examining regional groups. Using a similar logic as earlier, we split respondents into three more or less equally sized groups of economic change: regions that have experienced no or little wealth growth compared to the previous five years, those having gone through moderate growth and regions that have witnessed large growth. Results in Model 4 in Table C and in Figure B in the Appendix indicate that there are statistically significant differences between all three groups, and that regions with little or no income improvement are least likely to trust the EU. The probability of trusting the EU rises as regional income increases – thus confirming H2 – although in a non-linear manner, reaching a ceiling in regions with very large wealth growth.

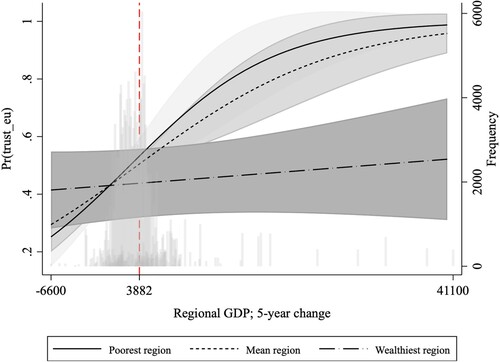

Finally, we hypothesised that EU trust is highest among poorer and middle-income regions that have experienced wealth growth (H3). To test this, we interact regional wealth status with wealth growth. Results in Model 5 in Table C in the Appendix indicate that the interaction effect is statistically significant in a negative direction, suggesting that the higher the regional income, the smaller the effect of income growth on EU trust levels. illustrates these findings. While poor and middle-income regions start out with relatively low likelihood of trusting the EU, predicted probabilities rise as they experience more wealth growth. In rich regions, on the other hand, political trust remains stable, no matter how large the growth in income. Looking at the extremes of the scale, experiencing large as opposed to no or little wealth growth increases the probability of trusting the EU by 74 percentage points in poor regions, from 25 to 99 per cent. Similar patterns appear for middle-income regions, where moving from no or little wealth growth to large wealth growth increases the likelihood of trusting the EU from 29 to 96 per cent. In both cases, the change is statistically significant at the 0.05 level (Χ2 = 0.00). Variation, however, is much smaller and not statistically significant for affluent regions where the probability of trusting the EU is 41 per cent in regions with no or little growth and 52 per cent in regions that have experienced large growth (Χ2 = 0.38). Results are similar in robustness tests controlling for national identity and using multilevel modelling (Table E in the Appendix).

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of trust in the EU, by regional wealth status and wealth growth. Notes: The histogram reflects the frequency distribution of regional wealth growth. Source: Eurobarometer waves, 2015—2019.

To corroborate these findings, we, again, zoom in on regional groups. We combine three wealth status groups with three groups of wealth growth. The resulting nine groups distinguish between poor, middle-income and affluent regions that have experienced either no or little, moderate, or large growth. Results are displayed in Figure C and in Model 6 in Table C in the Appendix. We observe that while there is a tendency for income growth to increase EU trust for regions of all income levels, poor regions clearly stand out. Experiencing wealth growth increases the probability of trusting the EU more among poor, but also middle-income regions compared to rich regions (see also pairwise comparison in Table D in the Appendix). Thus, the analysis confirms H3 by showing that income growth boosts EU trust among poor and to a certain extent also among middle-income regions, but much less so in wealthy European regions.

Taken together, our analysis shows that the relationship between regional wealth status and EU trust is non-linear: Europeans from middle-income regions are least likely to trust the EU (H1). However, trust is not only a function of wealth status but also wealth growth. Larger income growth generally yields higher probabilities to trust the EU (H2), although there seems to be a ceiling effect in regions that have experienced very large growth. We also find that institutional trust is dependent on the combination of wealth status and wealth increase. The likelihood of trusting the EU is highest in low or middle-income regions that experience larger growth (H3). In rich regions, EU trust is not dependent on wealth growth.

Discussion

In this article, we have put forward and empirically tested a theoretical framework of how regional wealth affects EU trust. We have added nuance to this complex relationship by considering three dimensions of regional inequality, i.e., regional wealth status, regional wealth growth, and regional wealth growth at different levels of wealth status. Our focus on these three dimensions allows us to provide a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between regional inequality and EU trust. We have highlighted the importance of concentrating our attention on the ‘middle-income’ region, considering within-region over-time growth, and accounting for the differential effects of growth on EU trust among poor, middle-income, and rich regions. Our findings contribute to the emerging literature on the political consequences of the uneven patterns of social and economic development across EU regions (see also Díaz-Lanchas et al., Citation2021; Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021; Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023), and help explain the counter-intuitive finding that Euroscepticism can be observed across different levels of regional economic development.

We have empirically demonstrated that the association between wealth status levels and EU trust is not linear. By considering the relationship as linear, extant research has paid less attention to a key type of region, i.e., the middle-income region where EU institutional distrust is concentrated. We have shown that Euroscepticism is not a poor region phenomenon, rather it is primarily found in the regions that are stuck in the middle, i.e., in a development trap. Our findings speak to the need to recognise the diversity in the ‘places that do not matter’ (McKay et al., Citation2021, Citation2023) and that scholarship should reconsider the perhaps oversimplified distinction between ‘losers’ (poor) and ‘winners’ (rich) of globalisation. This binary distinction conceals a third type of region in which institutional distrust is pronounced. In summary, our article suggests that EU distrust is more complex than the ‘revenge of the places that do not matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018).

Regional geography is important not only in static but also in dynamic terms. We have argued that individuals assess their regional wealth in relative terms, specifically by comparing the economic prosperity of their region to its own past and potential future trajectory. It is therefore their immediate lived experiences in the community – and how these change – that provide strong cues for opinion formation. A trajectory of economic growth, especially among the low and middle-income regions, is strongly associated with EU trust. This suggests that we should not be viewing Euroscepticism at the regional level as a syndrome of malaise associated with poor economic outcomes, but rather as a syndrome of stagnation. Or in other words, a positive economic outlook that brings with it a strong sense of economic opportunity and a sentiment of economic status improvement becomes translated into EU support.

By focusing on the growth and prospects for growth, our findings shed light on the apparent counter-intuitive finding that Euroscepticism can be simultaneously found in relatively wealthy and much less prosperous areas (Dijkstra et al., Citation2020; Los et al., Citation2017; McCann, Citation2018; Schraff, Citation2019). It is, we argue, the problem of stagnation and lack of growth that accounts for this puzzle. Relatedly, Dellmuth and Chalmers (Citation2018) argue that regional economic needs and fit are important in terms of the EU’s regional spending. We add to this discussion by specifically pointing out the importance of focusing on middle-income regions that are found in development traps as well as the need to grow at both low and middle-income levels. While acknowledging that political discontent is a multi-faceted phenomenon, our findings suggest that territorial intervention in the EU’s middle-income regions as well as policies that visibly improve the trajectory of economic growth of poor and middle-income regions could have beneficial political consequences, specifically on political trust which is central to good governance (OECD, Citation2017).

In summary, our article has assessed the relationship between regional inequalities and EU distrust. Future work could extend our framework that focuses on the middle-income region by examining other forms of political dissatisfaction, such as distrust in national institutions, anti-establishment attitudes, and policy outputs (e.g., Ejrnæs et al., Citationin press; see also Vasilopoulou & Halikiopoulou, Citation2023). We have accounted for the temporal dynamics in the relationship between regional inequality and EU distrust (see Dijkstra et al., Citation2020) using systematic statistical analyses, which consider both individual- and context-level data. Our findings are robust as we have controlled for important confounders at the individual level that relate to EU support, such as domestic political trust, economic perceptions, and national identity. Future research could examine whether the associations vary as a function of individual-level characteristics. For example, Chalmers and Dellmuth (Citation2015) find that the relationship between EU transfers and EU support is moderated by European communal identity. Research could test the extent to which regional affluence moderates the relationship between individual-level utility and identity considerations and EU trust (e.g., Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2019, Citation2020). Future research could leverage on country-level variation, by comparing whether the association between regional wealth and EU trust holds the same across different countries, e.g., does living in a poor or middle-income area of a poor country (e.g., in the Southern or Eastern peripheries) yield similar results as living in a comparable area in a well-off country (e.g., the European North)? Lastly, future research could examine patterns of EU trust as a function of within-region wealth diversity and/or intraregional centre-periphery dynamics. For example, new research shows that there are vast wealth discrepancies within regions with place-based funds boosting the incomes of highly skilled individuals across regional levels of wealth (Lang et al., Citation2022).

Overall, this article seeks to provide a bridge between utilitarian and cue-taking approaches, by analysing how individuals’ economic cost–benefit calculations are informed by their everyday influences experienced at the regional community context. In so doing, we have provided further evidence that EU distrust is rooted in spatially concentrated economic factors. More broadly, our findings contribute to the literature on globalisation backlash (Walter, Citation2021) by showing how the regional level of governance needs to be accounted for when understanding patterns of support for international cooperation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lisa Dellmuth, Mads Dagnis Jensen and Dominik Schraff as well as the participants of the ‘Regional Inequality and Political Discontent in Europe’ workshop held in Copenhagen in October 2022 for their insightful comments and recommendations. We would also like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers of the Journal of European Public Policy. All errors or omissions remain our own.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (519.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data and Replication files: available online at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/W1GW7A

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sofia Vasilopoulou

Sofia Vasilopoulou is Professor of European Politics at the Department of European and International Studies, King’s College London.

Liisa Talving

Liisa Talving is Research Fellow in Comparative Politics at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies, University of Tartu.

Notes

1 UK Office for National Statistics, German Federal Statistical Office and Italian National Institute of Statistics.

3 NUTS 1 level was used for Cyprus, Germany, Estonia, Hungary ('Central Hungary' only), Italy, Luxembourg, Latvia, Malta, Poland, United Kingdom. NUTS 2 level was used for Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Greece, Ireland, Spain, France, Hungary, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, Slovenia, Slovakia.

4 Results are similar when we use t-3 and t-1 time lags of the growth term (Figures D and E in Appendix).

References

- Adler, D., & Ansell, B. (2020). Housing and populism. West European Politics, 43(2), 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1615322

- Anderson, C. J. (1998). When in doubt, Use proxies. Comparative Political Studies, 31(5), 569–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414098031005002

- Anderson, C. J., & Reichert, M. S. (1995). Economic benefits and support for membership in the E.U.: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Public Policy, 15(3), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00010035

- Armingeon, K., & Ceka, B. (2014). The loss of trust in the European Union during the great recession since 2007: The role of heuristics from the national political system. European Union Politics, 15(1), 82–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116513495595

- Bouvet, F., & Dall’erba, S. (2010). European regional structural funds: How large Is the influence of politics on the allocation process? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(3), 501–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02062.x

- Broz, J. L., Frieden, J., & Weymouth, S. (2021). Populism in place: The economic geography of the globalization backlash. International Organization, 75(2), 464–494. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000314

- Carey, S. (2002). Undivided loyalties. European Union Politics, 3(4), 387–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116502003004001

- Chalmers, A. W., & Dellmuth, L. M. (2015). Fiscal redistribution and public support for European integration. European Union Politics, 16(3), 386–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515581201

- Cho, W. K. T., & Rudolph, T. J. (2008). Emanating political participation: untangling the spatial structure behind participation. British Journal of Political Science, 38(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000148

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018). Global competition and brexit. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000685

- Cramer Walsh, K. (2012). Putting inequality in Its place: Rural consciousness and the power of perspective. American Political Science Review, 106(3), 517–532. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000305

- De Lange, S., van der Brug, W., & Harteveld, E. (2023). Regional resentment in The Netherlands: A rural or peripheral phenomenon? Regional Studies, 57(3), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2084527

- Dellmuth, L. M. (2011). The cash divide: the allocation of European Union regional grants. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(7), 1016–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.599972

- Dellmuth, L. M., & Chalmers, A. W. (2018). All spending is not equal: European Union public spending, policy feedback and citizens’ support for the EU. European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12215

- Dellmuth, L. (Forthcoming). Regional inequalities and political trust in a global context. Journal of European Public Policy, this issue.

- Dellmuth, L. M., Schraff, D., & Stoffel, M. F. (2017). Distributive politics, electoral institutions and European structural and investment funding: Evidence from Italy and France. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(2), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12433

- De Vries, C. E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the future of European integration. Oxford University Press.

- Díaz-Lanchas, J., Sojka, A., & Di Pietro, F. (2021). Of losers and laggards: the interplay of material conditions and individual perceptions in the shaping of EU discontent. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 14(3), 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab022

- Diemer, A., Iammarino, S., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2022). The regional development trap in Europe. Economic Geography, 98(5), 487–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2022.2080655

- Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2020). The geography of EU discontent. Regional Studies, 54(6), 737–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603

- Eichenberg, R. C., & Dalton, R. J. (1993). Europeans and the European Community: the dynamics of public support for European integration. International Organization, 47(4), 507–534. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300028083

- Ejrnæs, A., & Jensen, M. D. (2019). Divided but united: explaining nested public support for European integration. West European Politics, 42(7), 1390–1419. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1577632

- Ejrnæs, A., Jensen, M.J., Schraff, D., & Vasilopoulou, S. (in press). Regional inequality and political discontent in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy.

- Ethington, P., & McDaniel, J. (2007). Political places and institutional spaces: The intersection of political science and political geography. Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.080505.100522

- Florida, R. (2021). Discontent and its geographies. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 14(3), 619–624. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab014

- Gabel, M. (1998). Interests and integration: Market liberalization, public opinion, and European union. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Gartzou-Katsouyanni, K., Kiefel, M., & Olivas Osuna, J. J. (2022). Voting for your pocketbook, but against your pocketbook? A study of brexit at the local level. Politics & Society, 50(1), 3–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329221992198

- Harteveld, E., van der Meer, T., & de Vries, C. (2013). In Europe we trust? Exploring three logics of trust in the European Union. European Union Politics, 14(4), 542–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116513491018

- Heidenreich, M., & Wunder, C. (2007). Patterns of regional inequality in the enlarged Europe. European Sociological Review, 24(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm031

- Hobolt, S. B., & De Vries, C. (2016). Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science, 19(1), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157

- Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in their Own land. The New Press. book.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2005). Calculation, community and cues. European Union Politics, 6(4), 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116505057816

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Im, Z. J., Mayer, N., Palier, B., & Rovny, J. (2019). The “losers of automation”: A reservoir of votes for the radical right? Research & Politics, 6(1), 1–7.

- Kurer, T. (2020). The declining middle: Occupational change, social status, and the populist right. Comparative Political Studies, 53(10-11), 1798–1835. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020912283

- Lang, V., Redeker, N., & Bischoff, D. (2022). Place-based policies and inequality within regions. OSF Pre-print. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/2xmzj

- Lechler, M. (2019). Employment shocks and anti-EU sentiment. European Journal of Political Economy, 59, 266–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2019.03.005

- Lenzi, C., & Perucca, G. (2021). People or places that don’t matter? Individual and contextual determinants of the geography of discontent. Economic Geography, 97(5), 415–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1973419

- Lipps, J., & Schraff, D. (2021). Regional inequality and institutional trust in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 60(4), 892–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12430

- López-Bazo, E. (2021). Does regional growth affect public attitudes towards the European Union? The Annals of Regional Science, 66(3), 755–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-020-01037-8

- Los, B., McCann, P., Springford, J., & Thissen, M. (2017). The mismatch between local voting and the local economic consequences of Brexit. Regional Studies, 51(5), 786–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1287350

- MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., O’Brien, P., Ormerod, E., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2022). Reframing Urban and Regional ‘Development’ for ‘Left behind’ Places. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab034

- Martin, R., Gardiner, B., Pike, A., Sunley, P., & Tyler, P. (2021). Levelling up left behind places: The scale and nature of the economic policy challenge. Routledge.

- Maxwell, R. (2019). Cosmopolitan immigration attitudes in large European cities: Contextual or compositional effects? American Political Science Review, 113(2), 456–474. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000898

- Mayne, Q., & Katsanidou, A. (2023). Subnational economic conditions and the changing geography of mass euroscepticism: A longitudinal analysis. European Journal of Political Research, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12528

- McCann, P. (2018). The trade, geography and regional implications of Brexit. Papers in Regional Science, 97(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12352

- McCann, P. (2020). Perceptions of regional inequality and the geography of discontent: Insights from the UK. Regional Studies, 54(2), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1619928

- McKay, L., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2021). Political trust in the “places that don't matter”. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 642236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.642236

- McKay, L., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2023). What is the geography of trust? The urban-rural trust gap in global perspective. Political Geography, 102, 102863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102863

- McLaren, L. M. (2006). Identity, interests and attitudes to European integration. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Munis, B. K. (2022). US over here versus them over there … literally: Measuring place resentment in American politics. Political Behavior, 44(3), 1057–641078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09641-2

- Nicoli, F., Walters, D. G., & Reinl, A. K. (2022). Not so Far east? The impact of central-eastern European imports on the brexit referendum. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(9), 1454–1473. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1968935

- OECD. (2017). Trust and public policy: How better governance can help rebuild public trust. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en

- Rhodes-Purdy, M., Navarre, R., & Utych, S. M. (2021). Populist psychology: Economics, culture, and emotions. The Journal of Politics, 83(4), 1559–1572. https://doi.org/10.1086/715168

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Dijkstra, L. (2021). Does cohesion policy reduce EU discontent and Euroscepticism? Regional Studies, 55(2), 354–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1826040

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., Terrero-Davila, J., & Lee, N. (2023). Left-behind versus unequal places: interpersonal inequality, economic decline and the rise of populism in the USA and Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbad005

- Schraff, D. (2019). Regional redistribution and Eurosceptic voting. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(1), 83–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1394901

- Schraff, D., & Pontusson, J. (Forthcoming). Falling behind whom? Economic geographies of right-wing populism in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, this issue.

- Talving, L., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2021). Linking two levels of governance: Citizens’ trust in domestic and European institutions over time. Electoral Studies, 70, 102289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102289

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Halikiopoulou, D. (2023). (2023). Democracy and discontent: institutional trust and evaluations of system performance among core and peripheral far right voters. Journal of European Public Policy, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2023.2215816

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Talving, L. (2019). Opportunity or threat? Public attitudes towards EU freedom of Movement. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(3), 805–102823. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1497075

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Talving, L. (2020). Poor versus rich countries: a gap in public attitudes towards fiscal solidarity in the EU. West European Politics, 43(4), 919–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1641781

- Walter, S. (2021). The backlash against globalization. Annual Review of Political Science, 24(1), 421–444