ABSTRACT

Research on policy learning has shown that actors can learn in inadequate modes. To better understand policy learning failures and possible remedies, we ask how and why inadequate learning environments occur and how they can be changed. Building on the varieties of learning approach, we distinguish between perceived and functional actor certification and problem tractability. On this basis, we introduce a typology of learning mode misfits and indicative adjustments and revisit previous case studies from this perspective. We then apply the concept to a case of policy learning in a socio-technical transition, arguing that learning environments in socio-technical transitions tend to overvalue actor certification and problem tractability and require recalibration towards reflexivity. Assessing the effects of participatory co-creation interventions on technology development in precision grassland farming in two living labs in Germany, we provide evidence that decentral arenas and participatory experimentation facilitate learning by coequal actors scrutinising problems.

Introduction

Learning is commonly expected to entail improvement. By learning something, one would hope to increase knowledge or skills. Unfortunately, this cannot be taken for granted, neither in general nor in the case of policy learning, where the outcomes of learning are not necessarily new or improved (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013). Research building on the varieties of learning approach often refers to policy learning as ‘the updating of beliefs’ (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2013, p. 600). Recently, work in this tradition has highlighted that policy learning processes sometimes lead to or reinforce policy failure (Dunlop, Citation2017; Dunlop et al., Citation2020). In this perspective, policy learning takes place in one of four learning modes, depending on either high or low degrees of actor certification (i.e., levels of authority concentration) and problem tractability (i.e., causal understanding of the situation). This allows to ask when and how actors might learn in ‘wrong’ modes (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2016). Building on further evidence of distorted learning processes (Beach et al., Citation2021; Millar, Citation2020), we take up and paraphrase this question: How and why do policy learning processes take place in inadequate learning modes? To address this question, we develop the notion of learning mode misfits, i.e., constellations that are prone to produce suboptimal learning outcomes due to the learning actors’ over- or undervaluation of problem tractability and/or actor certification.

The analytical usefulness of a systematization of learning mode misfits within the varieties of learning approach is illustrated by revisiting cases of learning failure documented in previous research. We then apply the conceptual framework to investigate learning mode misfits and possible remedies in the field of socio-technical transitions, i.e., processes of a fundamental reorientation of complex ensembles of policy, technology, markets, infrastructure, science and culture (Geels & Schot, Citation2007). We first show that socio-technical transitions are characterised by a tendency towards overvaluation of problem tractability and actor certification, before we analyse how a living lab intervention in a particular case of technology development reduced both dimensions of overvaluation.

The argument proceeds as follows: Section 2 revisits the literature on policy learning and varieties of learning. Section 3 introduces the concept of learning mode misfits and indicative corrections. Section 4 elaborates why problem tractability and actor certification tend to be overvalued in socio-technical transitions. Section 5 introduces a paradigmatic case – learning processes related to innovations in precision grassland farming. Section 6 presents the findings and distinguishes four modes of reflexive learning, before Section 7 discusses implications, potential shortcomings and future research on varieties of learning.

Policy learning and the varieties of learning approach

Literature reviews on policy learning (Moyson et al., Citation2017) often rely on the heuristic by Bennett and Howlett (Citation1992) who organised research on the subject along the question: Who learns what (and how) to what effect? The subjects of learning can be either individuals or collectives. Learning by individuals has been investigated to understand belief change among those who take or influence decisions in the policy process (Pattison, Citation2018). Collective or ‘organizational’ learning is a distinct phenomenon at a different level, starting and interacting with individual learning (Argyris & Schön, Citation1978). Its analysis requires approaches that include the transition between individual and organisational learning (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013). At each level, the respective ‘environments’ constitute conditions of learning processes (Riche et al., Citation2021). For example, learning in governments (Etheredge & Short, Citation1983) and administrations with their general jurisdiction and formalised structures will exhibit different dynamics (Bennett & Howlett, Citation1992) than learning in less structured, but substantially focused policy communities or networks (Heclo, Citation1978). Another perspective on the subject of learning has been established in the varieties of learning approach by investigating attributes of actors within a learning collective. Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2013) distinguish learning contexts or learning environments with different ‘certification of actors’, depending on homogeneous or heterogenous distribution of authority within the learning group. Under low certification, learning subjects are more or less equal regarding ascribed expertise or decision-making power. High certification, however, implies the prevalence of legitimate authorities based on either knowledge or power and creates asymmetric learning situations. While this distinction is applicable across levels of learning subjects (Moyson et al., Citation2017), micro-foundations remain a relevant issue for varieties of learning research (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2018a).

The object of learning constitutes – at least in the field of policy studies – the broadest strand of literature. McConnell’s (Citation2010) typology of policy success and failure in terms of politics, programmes, and processes helps to further differentiate policy learning (Howlett, Citation2012).

Learning on politics or political learning – a concept pioneered by May (Citation1992) – involves not so much learning on content or implementation of policies, but learning on how to advocate policies in debates and how to obtain desired positions. Recent work has addressed the relation between policy-oriented and power-oriented learning (Trein & Vagionaki, Citation2022).

Learning on policies or programmes has become a topic in research on advocacy coalitions and policy paradigms. The advocacy coalition framework (Sabatier, Citation1987) focuses on policy-oriented learning as the updating of beliefs in light of new information and knowledge, which then may exert influence on the actors’ policy preferences (Moyson, Citation2017). Policy-oriented learning is typically slow and limited in scope (Sandström et al., Citation2021) and, like lesson drawing (Rose, Citation1991), restricted to instrumental aspects of learning (Bennett & Howlett, Citation1992). Rather than scrutinising actors’ policy core beliefs, selective learning may even reinforce them (Weible et al., Citation2023). Changes in the ideational framework of a policy, which embodies beliefs about the types of problems that require political intervention, the goals to be pursued by public policy, and adequate policy instruments (Hall, Citation1993), are empirically rare, but far-reaching if they occur (Vogeler, Citation2019). Such changes require social learning, which involves the policy goals as object of learning rather than merely revising policy instruments or their calibration to achieve a given set of policy goals. This often entails a re-evaluation of the ideational foundations. Such a ‘paradigm shift’ is usually preceded by a broadening perception of policy failure and a change in the locus of authority (Hall, Citation1993), which typically involves a change in government. Different from Hall’s original notion, paradigm shifts often unfold over longer periods of time through the accumulation of incremental change (Coleman et al., Citation1996; Feindt & Flynn, Citation2009; Oliver & Pemberton, Citation2004).

Learning on processes refers to the execution or implementation of policies. Any well-intended programme can fail without sufficient resources, capable staff and clear competencies (Bennett & Howlett, Citation1992). This research line emphasises government learning (Etheredge & Short, Citation1983). But while the ability of governments to learn has remained an important topic in the literature (Bandelow, Citation2008), research on intra- and interorganisational learning has to a large degree migrated to organisational research (Holmqvist, Citation2016).

The varieties of learning approach focuses on the problem dimension of policy learning. Here, participants analyse causes of policy success and failure. Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2013) suggest that the difficulty of this task depends on the respective ‘problem tractability’, which constitutes one fundamental dimension to distinguish different modes of learning, besides actor certification. In situations of high tractability, drivers of policy success and failure tend to be less contested and learning typically occurs as the result of stakeholder interactions in the policy process. In contrast, with low tractability, solutions that are widely assumed to work are not readily available, which opens up the scope of problem analysis and policy prescription.

Combining the dimensions of actor certification and problem tractability, four modes of learning can be distinguished (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2022): learning in epistemic contexts (high certification/low tractability), learning in reflexivity (low certification/low tractability), learning as by-product of bargaining (low certification/high tractability), and learning in hierarchy (high certification/high tractability). Following Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2018b), epistemic learning describes a situation in which problems are hard to understand and even harder to solve, but credible and communicative experts are available to take the role of the teacher, i.e., to decide knowledge claims with legitimate authority. In the reflexive learning mode, problems are difficult, while certified actors are lacking, which levels sources of knowledge and opens up the licence to raise and contest knowledge claims. In response, participation, deliberation and experimentation are needed to develop solutions and settle disputes. If a plurality of equitable actors meets a situation where problems are relatively unambiguous and suitable policies are available, typically few cognitive claims are contested. Then, bargaining dominates policy-making interactions and provides insights on actors’ preferences and the costliness of agreements. Finally, a learning context may be characterised by clear-cut problems and unevenly certified actors creating a hierarchy. Learning then typically focuses on how to bend or escape these hierarchies and on sanctions for cases of defection.

To what effect does policy learning occur? In case of a re-evaluation of former solutions in the face of evolving problems, one effect of learning could be revised solutions. This might include organisational change, strategy change, and, most importantly, policy change at the level of instruments, goals or instrument calibrations. However, neither are all instances of change necessarily an effect of learning as long as the outcomes are not traced back to the process of learning (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013), nor does learning per se automatically result in observable change (Bandelow et al., Citation2019). Linking the object to the effect is challenging in empirical policy learning research. A frequent issue in discussions about operationalisation (Crow et al., Citation2018) is that change might be an indicator of, but does not necessarily equal learning (May, Citation1992). Furthermore, Heikkila and Gerlak (Citation2013) question the expectation that the outcome of learning always constitutes an improvement, while in reality learners might draw ‘wrong’ lessons, e.g., by choosing options that lack effectiveness, efficiency or legitimacy. Studies within the varieties of learning approach have investigated such negative learning effects (Dunlop et al., Citation2020; Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2016). However, relating policy learning to shortcomings instead of benefits does not necessarily imply advocating neglected policy alternatives (Dunlop, Citation2017) and, of course, those affected might disagree with the assessment of policy makers and authoritative experts. Apart from the need to link learning outcomes to policy change, concepts are missing to diagnose inadequate learning situations and identify strategies to improve them. We turn to the latter task in the following section.

Inadequate learning environments and a typology of learning mode misfits

Different policy learning modes can exhibit specific strengths and weaknesses that are rooted in their respective characteristics (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2018a). But is it also possible that a policy learning mode is inadequate because it does not match the contextual conditions? Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2016) have investigated this question with regard to the European Commission. Their analysis showed that the Commission, based on political considerations, opted for bargaining and hierarchy modes in the European Semester. However, the conditions for these modes were not met as the problems were not sufficiently tractable. Using slightly different dimensions and modes of learning, Millar (Citation2020) argues that in closed institutional contexts a presumed high tractability/certainty of problems leads to technical learning, while a low tractability/certainty induces epistemic learning. In her case study of Canadian hydraulic fracturing, a re-shaping of the institutional context towards an enhanced perception of uncertainty resulted in stricter regulatory outcomes. Studying the epistemic learning mode in the case of bovine tuberculosis management in England, Dunlop (Citation2017) described the intricate interplay of epistemic communities and government agencies, which in this case led to policy failure due to insufficient linking of evidence to policy alternatives. How epistemic authorities can fail in epistemic learning has been documented for the European Banking Union by Beach et al. (Citation2021), drawing on the concept of analogous reasoning, i.e., the tendency to interpret current events as variations of previous experiences. Finally, Dunlop et al. (Citation2020) have investigated learning failure in the case of the Brexit negotiations, when the British government tested several learning modes unsuccessfully, until settling on the mode of bargaining, which was nonetheless inadequate because it neglected the highly uncertain effects of leaving the EU.

These studies of learning in inadequate modes seek to improve our understanding when, how and why policy learning fails, which in turn would allow to improve learning processes. We contribute to this work by conceptualising such inadequate modes against the background of three axioms. Our first axiom is that learning modes emerge from the learning actors’ implicit or explicit perception of the learning environment. The latter, as suggested by the varieties of learning approach (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2018a), is characterised by varying degrees of actor certification and problem tractability and can be illustrated by the respective causal logics and styles of interaction (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2022). On the dimension of tractability, policy makers need to evaluate problems: If the latter are sufficiently understood and can be addressed by available solutions, policy makers will opt for a competitive style of interaction and follow a logic of consequence or habit. If, however, problems are not well understood and ‘good’ policy alternatives are missing, policy makers could engage in cooperative ‘puzzling’ (Heclo, Citation1974) based on a logic of appropriateness or cognition (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2022), although they may also get involved in epistemic competitions. On the dimension of certification, policy makers need to evaluate roles that could create an asymmetry in claims to authority. In epistemic contexts, ‘teachers’ can claim a certification based on epistemic authority; in hierarchies, ‘leaders’ can distinguish themselves based on rules (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2022).

Against this background, our second axiom posits that problem characteristics and actor roles are contingent and can be contested. This has already been observed by McNutt and Rayner (Citation2018, p. 771) for the symmetric mode of reflexive learning, which is ‘unstable and subject to constant pressure for routinization that clarifies the role of learners and teachers’. Vice versa, in epistemic environments it is possible that teachers face contestation and more symmetric environments of puzzling are instituted. Such a shifting between learning modes can be generalised along both dimensions. Depending on the degree of actor certification and problem tractability, learning environments can be adapted and also change from hierarchy to negotiation (and back), from epistemic to hierarchical contexts (and back), or from bargaining to reflexivity (and back).

Finally, our third axiom posits that a mismatch is possible between the learning mode chosen by the policy makers in a given situation and the learning mode suitable for generating functional learning outcomes under these conditions. The certification of actors might be defined as higher or lower than functional for learning and for the legitimacy of the outcome. Likewise, the tractability of problems could be presumed higher or lower than suitable, undermining the ability to arrive at well-working and efficient solutions. Whenever one dimension is either over- or undervalued, this discrepancy constitutes a learning mode misfit. (Nota bene: Whether such a misfit exists, can be contested from a participant perspective and assessed from an observer perspective, using established criteria of expertise and scientific knowledge evaluation.) Based on these conceptual considerations, four types of learning mode misfits can be derived, building on and extending the varieties of learning approach.

Overvaluation of actor certification: In this situation, some actors are attributed a leading role in solving a problem and settling cognitive or moral claims, although a more equal consideration of perspectives or competencies would be more adequate. The distinguished positions of the certified may have been legitimately acquired and proven advantageous through useful advice or judicious decisions in other contexts. Yet, for the task at hand, integrating different or additional sources of knowledge and power would be necessary. This type of misfit therefore manifests as a tacit lack of plurality in epistemic or hierarchical contexts.

Undervaluation of actor certification: This learning mode misfit occurs in situations in which actors are assigned equal roles in contributing to a learning process, e.g., through speaking time or voting rights, in attempts to integrate different sources of knowledge or to meet the requirements of power relations. However, if some actors are held back in contributing collectively useful capabilities to give advice or foment decisions, their lack of certification creates an underutilisation of these analytical and problem-solving capacities. This type of misfit can be referred to as a tacit lack of guidance in contexts of reflexivity or bargaining.

Overvaluation of problem tractability: Often, policy problems turn out to be trickier than they appear. In contexts in which problems are perceived as clearly linked to identifiable causes that can be reasonably addressed, actors may run the risk of overlooking factors with different social, temporal or spatial dimensions. Frames and narratives might spur unreasonable simplifications. The above-mentioned differentiation between instrumental and social learning exemplifies that different levels of learning matter. If problem tractability is overvalued, the scope of admissible knowledge claims or contestation is more limited than reasonably justifiable. In order to improve learning results, the complexity of problems would have to be acknowledged. This type of misfit represents a tacit lack of insight in contexts of bargaining or hierarchy.

Undervaluation of problem tractability: This learning context is characterised by an overly broad scope of contestation over knowledge claims. As a result, policy deliberations become more complicated than justified. Although issues could be clearly defined and efficient and effective policy solutions would be available, decision-making is delayed, e.g., by talking up partial aspects and developing speculative theories when action could be taken. This type of misfit emerges as a tacit lack of ease in epistemic or reflexivity contexts.

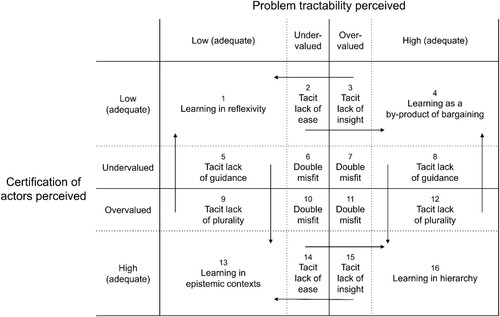

The four types of learning mode misfits are summarised in . In areas 1, 4, 13 and 16, the learning mode is a reasonable match for the condition. In areas 2, 3, 14 and 15, over- or undervalued problem tractability meets reasonable actor certification. In areas 5, 8, 9 and 12, problem tractability is reasonable, but actor certification over- or undervalued. In areas 6, 7, 10 and 11, both types of misfits occur simultaneously. For example, learning in the mode of reflexivity in a context in which high actor certification and problem tractability would be adequate implies a tacit lack of guidance and a tacit lack of ease since both dimensions are undervalued (area 6). Learning mode misfits can be resolved by adapting the learning environment in a way that is more adequate to the policy context. In , the arrows indicate how a learning environment would need to be shifted to better match the context conditions. Double misfits require a shift towards the diagonally opposite learning mode. For example, area 6 represents an inadequate reflexive learning environment that could be improved by increasing the certification of competent experts or leaders and the acknowledgement of problem tractability, as represented by a shift to area 16.

Figure 1. Typology of learning mode misfits in the varieties of learning approach (Source: authors’ compilation, adapted from Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2013, p. 55), and building on Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2013, p. 603).

Diagnosing a learning mode misfit requires a standard of ‘appropriate’ actor certification or problem tractability. As policy processes are characterised by a plurality of stakeholders, interests, values, and perspectives, we should not expect one ‘true’ evaluation of certification or tractability, but a plurality of assessments subject to epistemic or political contestation (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2016; Millar, Citation2020). It is therefore possible that ‘teachers’, ‘leaders’ or collectives deliberately or unconsciously choose unsuitable learning modes, e.g., for political reasons or due to ideational or institutional path dependence (Pierson, Citation1993). Wherever learning environments follow a purposeful self-serving design, this could be regarded a case of political learning (May, Citation1992) which aims less at successfully navigating a political environment than at shaping it. Policy makers may seek to establish a learning mode that does not fit the requirements of successful learning but favours learning processes and outcomes which they prefer. Learning on how to achieve the design of such a learning environment may be understood as a (second order) political learning process.

Learning mode misfits can be identified from different social, material and temporal perspectives. In the social dimension, we distinguish in particular between a participant and an observer perspective, in the material dimension between actor certification and problem tractability, and in the temporal dimension between ex-ante, simultaneous and ex-post claims. Participants’ claims about learning mode misfits are likely to be contested and carry political implications. Analysing such claims and their effects would be an interesting avenue for future research on policy learning.

In this paper, we focus on an ex-post analysis of learning modes from an observer perspective to identify possible dysfunctionalities, i.e., ineffective, inefficient, or illegitimate learning outcomes which result from inadequate learning environments. However, we must assume that a learning mode misfit is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition. While the concept of learning mode misfits addresses the adequacy of a policy learning environment to the policy context, the notion of dysfunctional policy learning refers to the capacity of policy learning (at the level of learning processes and learning environments) to produce effective, efficient and legitimate policy results (at the level of policy outputs and outcomes). We expect inadequate policy learning environments, i.e., learning mode misfits, to create conditions for dysfunctional policy learning, leading to policy failure, although the causal links must be further established through case studies (Zaki et al., Citation2022).

To understand the links between inadequate policy learning environments and policy failure, we can either trace forward the effects of learning mode misfits, or we can identify cases of policy failure, using ineffective, inefficient, or illegitimate policy outcomes as a starting point, and trace back the underlying learning environments to assess possible learning mode misfits. To assess policy learning environments and learning outcomes, criteria are required to identify faulty lessons as well as over- and undervaluation of the learning situation. Deficient learning outcomes may be characterised by the generation of policy alternatives that are ineffective, inefficient or illegitimate (Scharpf, Citation1997) or by an overall lack of policy alternatives available (Dunlop, Citation2017). Over- and undervaluation can be assessed by generating data on the learning subjects’ perception of the learning environment and probing it for (1) a possible lack of teachers (McNutt & Rayner, Citation2018) or leaders vs. inadequate top-down teachings or commands and for (2) problem accounts neglecting aspects, interactions, or side effects vs. signs of saturation of problem deliberation. Whether a specific learning mode constitutes a misfit requires careful assessment of the policy context. For example, a top-down straightforward learning environment that scores high on certification and tractability indicates a hierarchical learning mode, for which a potential overvaluation needs to be shown on each dimension.

The typology of learning mode misfits improves our conceptual understanding of learning environments, possible shifts and potential links between policy learning processes and outcomes. This can be illustrated by revisiting the five cases from the beginning of this section. The case of hydraulic fracturing in British Columbia and Nova Scotia (Millar, Citation2020) can now be understood as suffering from tacit lack of insight. Problem tractability is initially perceived as high in both jurisdictions, limiting learning to technical aspects. However, shifting the learning context towards low problem tractability in Nova Scotia fostered social and political learning. Regarding policy learning in the European Semester, the European Commission aimed to address learning mode misfits when shifting the context of learning towards hierarchy (and back) after witnessing a tacit lack of guidance (or plurality) in negotiations with Greece (or France respectively). Yet, this case suffered from a tacit lack of insight in both learning modes as there were no viable policy solutions available (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2016). The investigation of context shaping by the British government in the aftermath of Brexit (Dunlop et al., Citation2020) shows that reflexivity might have been the most appropriate learning mode. However, the necessary openness and trust were absent. Therefore, seemingly easy solutions were prescribed top-down in a mode of hierarchy and later – after running aground a tacit lack of plurality in 2017 – in a mode of bargaining. Yet, none of these learning modes generated successful outcomes because their contexts did not allow for an open-minded and trustful consideration of alternatives, which constituted a tacit lack of insight.

Analogous reasoning as in the case of the European Banking Union could represent a situation in which a tacit lack of insight occurs within epistemic learning due to heuristics derived from similar but different problems from the past (Beach et al., Citation2021). Similarly, insufficient capacities in translating knowledge into practical solutions – which caused policy failure in disease containment in English cattle farming – do not necessarily show that actors learn in an inadequate mode, but might also indicate that epistemic learning needs to be improved to provide useful policy proposals in time (Dunlop, Citation2017). At the same time, a tacit lack of plurality is part of both cases as the involvement of further actors would have opened up the learning process to question established but insufficiently justified knowledge claims and to generate further policy alternatives.

Learning mode misfits in socio-technical transitions

An important area of policy-making where learning mode misfits are particularly likely are socio-technical transitions, i.e., interdependent processes of change in technological development and social practices that alter system elements and relations to a degree that affects their fundamental paradigms and logic of operation (Geels & Schot, Citation2007). Examples are the reorientation of the transport or housing sectors towards sustainability. Due to the involved collective action problems and their far-reaching implications, socio-technical transitions are highly political endeavours (Kenis et al., Citation2016; Smith & Stirling, Citation2010). Previous work has pointed to this area of research as relevant for policy learning, for example regarding the protection of novel innovations (Boon & Bakker, Citation2016) or the role of feedback loops for actor reorientations and market success (Geels & Ayoub, Citation2023). While successful learning about new technologies needs to be embedded in learning on social dimensions (Kivimaa & Sivonen, Citation2023), overcoming established practices and habits also requires unlearning (Van Mierlo & Beers, Citation2020).

Socio-technical transitions constitute learning environments that are prone to biases in the perception of actor certification and problem tractability. Continued application of well-established solutions to problems which have become more complex amounts to an overvaluation of problem tractability. Crediting experts with epistemic authority even if the necessary capacities for effective problem-solving have shifted leads to overvaluation of actor certification. Learning contexts around emerging technological innovations (Stirling, Citation2010) often focus on narrow technological aspects so that problems might appear more tractable than justified, while actor certification based on scientific and technological expertise is overvalued at the expense of broader perspectives on social and economic implications.

Socio-technical system transitions are complex, non-linear, indeterminate processes that require a holistic perspective since problems cannot be isolated and solved once and for all (Wagenaar, Citation2007), while actors holding authoritative positions may ‘simply do not know what is going on or, even worse, have no way of knowing it’ (Wagenaar, Citation2007, p. 27). Neglect of system complexity leads to overvaluation of problem tractability and actor certification. The relevance of this problem is corroborated by the omnipresence of ‘wicked problems’ (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973), i.e., ambiguous issues that lack evident causes, substantial knowledge or evaluative standards and therefore cannot be addressed by relying on evidence or objectivity (Daviter, Citation2019). Climate change as a ‘super wicked problem’ (Levin et al., Citation2012) illustrates this dilemma: Actors developing solutions are driven by short-term self-interest discounting the long-term future, while approaches to develop solutions address a linear and predictable world. In the terminology of learning mode misfits, policy learning in complex system environments is likely characterised by a tacit lack of insight and a tacit lack of plurality.

However, many innovation concepts, e.g., in the context of digitalisation (Lühmann & Vogelpohl, Citation2023), suggest blueprint solutions that simply need to be implemented. Technology-centred strategies to address wicked problems entail two simplifications. First, focusing on technological solutions implicitly narrows down the scope of problem considerations, e.g., by providing narratives of reasonable uses, authorised users and legitimate purposes, which imply high tractability. Second, technological innovators are presented as authorities on the innovation’s ‘correct’ use, implying high actor certification that is, however, biased towards an established in-group. The ensuing learning mode misfits in socio-technical regimes and sustainability transitions – tacit lack of plurality and tacit lack of insight – imply restricted forms of interaction (Van Mierlo & Beers, Citation2020) and actor access (Goyal & Howlett, Citation2020). These exclusionary effects tend to constrain the consideration of relevant dimensions of effectiveness and efficiency of solutions and reduce the legitimacy created through the policy learning process.

Case study: material and methods

To illustrate the usefulness of the typology of learning mode misfits, we now turn to a case study from a socio-technical transition context: the introduction of precision farming technologies in grazing systems in Germany. The underlying collective action problem is the long-term decline in the economic viability of extensive grazing systems which have important functions for biodiversity in agricultural landscapes (Bengtsson et al., Citation2019). Farmers have responded by keeping their cattle in stables rather than on meadows, by intensifying grassland management (using pesticides, artificial fertilisers, specially-bred grass varieties), converting grassland into arable land, or land abandonment. Public payments for extensive grassland management and grazing under the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) stabilised some market niches but did not offset broader economic trends (Pe'er et al., Citation2020). European and national policies now promote digital technologies to improve the economic viability and ecological performance of grasslands and to enhance animal welfare (European Commission, Citation2020).

Digitalisation, i.e., the combined use of IT technologies, sensors, robotics and automatisation, is often hailed as a transformative pathway to improve the sustainability and economic viability of industries with negative environmental externalities and business models rooted in an economic area of cheap and abundant resources. ‘Digital agriculture’ is a summary term for the quickly evolving digitalisation on farms, inter alia to combine remote access to fine-grained real-time data on agricultural production processes with artificial intelligence and big data applications (Klerkx et al., Citation2022). The predominant aim is to increase resource efficiency through more targeted use of inputs and other interventions, as summarised in concepts like ‘precision farming’ or ‘precision livestock farming’.

‘Precision grassland farming’ is the application of this concept in the areas of grassland cultivation and pasture-based animal husbandry. Its core technologies are sensors that measure the location and health data of animals, virtual fencing systems, remote sensing techniques deploying drones or satellites, and decision support systems that draw on the generated data and provide user interfaces which pre-structure and recommend management decisions. Detailed measurement and analysis of processes in plants, animals and agro-ecological systems improve the information basis for human interventions. ‘Smart farming’ innovations promise solutions that facilitate grassland cultivation and help to improve economic viability. Yet, critical research has questioned this story of technology as panacea. Precision agriculture is not completely new, but rooted in established practices (Duncan et al., Citation2021). Consequently, it does not transcend long-standing inequalities and power relations, but rather reproduces and potentially reinforces them (Hackfort, Citation2021). Data ownership, for example, favours IT providers over farmers (Bronson & Knezevic, Citation2016). The problem that the innovation is meant to address is often reduced to control and optimisation of cultivation processes. Predominant farming systems and practices that create significant negative external effects are not questioned, but taken for granted. As an implication, ‘smart farming’ approaches induce learning modes with inadequately high problem tractability and actor certification, corresponding to area 11 of . Therefore, the typology of learning mode misfits would suggest to move towards area 1 (reflexive learning) by taking measures to reduce problem tractability and actor certification.

Our empirical case examines an ongoing attempt to transform a technology-driven innovation process into a reflexive learning process. The GreenGrass project aims to develop and implement precision grassland farming innovations in several pilot areas in Germany. Parallel participatory co-creation processes were established in these areas to create an environment for reflexive learning that acknowledges complexity more extensively and allows actors to interact on a par. This participation in an ongoing socio-technical transition allows to adjust learning processes by reducing problem tractability and actor certification. This way, we can investigate the shifting from hierarchical learning to learning in reflexivity.

It should be noted that our approach differs from previous case studies which have identified learning modes and learning mode shifts to discover misfits and link learning modes to learning outcomes. The co-creation of interventions allows us to analyse shifts of learning modes by ‘doing’ them. Such an inquiry is rooted in the tradition of participatory action research (Chevalier & Buckles, Citation2019). It allows to reduce actor certification by following a transdisciplinary approach and to reduce problem tractability by embedding the technological innovation in the broader socio-technical system context (Rogers et al., Citation2013).

Two German study regions were selected to maximise variance regarding context characteristics. The Solling region in the South of Lower Saxony is geographically characterised by a low mountain range with comparatively small and dispersed paddocks, including hillside locations with difficult access and pervasive scrub encroachment. Only 42 and 49 percent of farms in the districts of Northeim and Holzminden were full-time occupations in 2010 (Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder, Citation2011). Landscape and nature protection as well as tourism are relatively important in the region. Direct marketing of meat products is significant, but experienced difficulties during the Covid-19 pandemic. The region Havel Lowlands in the West of Brandenburg consists of flatlands spread out along the river Havel. The quality of soils is mixed, with often overly high or low humidity, making grassland cultivation a relatively attractive option. Post-socialist agrarian structures include many comparatively large farms which are often organised in specialised branches, including e.g., energy production and nature conservation. The different characteristics of the study regions ensure that findings reflect multiple characteristics of grassland farming systems.

In each region, a living lab infrastructure was established. Living labs are forms of transdisciplinary research that aim to include practitioners in each step of a research process linked to the establishment of a social or technological innovation (Bulkeley et al., Citation2016). Our two living labs were based on networks of relevant practitioners (Compagnucci et al., Citation2021) representing the regional agro-ecosystem (McPhee et al., Citation2021). This included grassland farmers, public administrators, nature and landscape conservationists, animal welfare officers, veterinarians and regional business developers. Initially, a core group of four to six practitioners was constituted as a committee referred to as ‘living lab board’. Between autumn 2020 and spring 2022, seven virtual group discussions of approximately two hours were conducted in the living lab boards. In July 2021 and May 2022, two full-day on-farm practice workshops were conducted, with the participation of further invited practitioners from the region, e.g., from grassland-based value chains. Scientists working on three core technologies of precision grassland farming (virtual fences, remote sensing and decision support), as well as on their ecological, economic and regulatory contextualisation, discussed their research. provides an overview on the fieldwork activities.

Table 1. Overview on collected material from fieldwork conducted between 2020 and 2022.

The three precision farming technologies were introduced to participants, who examined, tested and discussed the current state of development. During the investigation period, all technologies were in a conceptual or prototyping stage, which allowed to engage with drafts, physical components and early results. The interactions were designed to influence the further research and design process. Thereby, the innovations served as boundary objects (Star & Griesemer, Citation1989): They are ontologically stable but semantically fluid to acquire different meanings for participants with different interests. Regarding remote sensing technologies, for example, images provided by drones provide a common point of reference for debate, which at the same time allows for various interpretations, thereby opening up multiple perspectives on grassland farming issues (Kleinschroth et al., Citation2022). Other studies have similarly highlighted the usefulness of utilising agricultural innovations as boundary objects (Klerkx et al., Citation2012) to create a context of reflexivity (Metze & Van Zuydam, Citation2018). They allow for participatory experimentation, focusing activities on subjects without predetermining them, thereby initiating a process of scrutinising problem tractability.

In the case study, interactions between participants on technologies were documented through audio recordings and field memos. Protocols document the course and results of events and entail transcripts of most verbal statements by participants. This material was coded inductively (Saldana, Citation2021) to identify instances of interaction on the technologies between participating scientists and practitioners. The coding system was developed based on manifest themes of these interactions, but in a second step of coding also drew on latent evaluative criteria utilised in the developers’ responses to contributions by practitioners.

Findings

The living lab interventions in our case study aimed to address learning mode misfits in technology-centred solutions to collective action problems that suffer from tacit lack of plurality and tacit lack of insight. Our analysis shows how problem tractability and actor certification were reduced.

Through the non-hierarchical mode of interaction in the living lab, scientists had to respond to practitioner utterances. They used three evaluative criteria in doing so: relevance, novelty and feasibility. On this basis, we inductively identified four styles of reflexive learning (see ) enabled by a learning environment with low problem tractability and actor certification.

Table 2. Four styles of reflexive learning under reduced tractability and certification.

(1) Reconsidering scopes: In this style of reflexive learning, practitioners contribute aspects that scientists do not regard as relevant at the current stage of development. A typical response points out that the practitioners’ suggestions are beyond the scope of current research. This might appear as distancing science from practice by invoking epistemic authority. Yet, the inclusion of ideas and visions beyond current ambitions forces scientists to reflect the scope and limitations of their work from other perspectives. Furthermore, conceptualizations of the use environment of innovations become more complex, including possible feedback effects beyond the intended functions and effects. Reconsidering scopes can be illustrated by responses to the concept of virtual fencing (Sources 01, 02, 04, 05, 06, 07), which entails equipping animals with GPS-based tracking devices that compare the position of the animal with predefined virtual borders. If an animal approaches or crosses this border, it receives an auditive signal or electric stimulus to induce a return to the predefined area. Practitioners raised two sets of concerns: First, escaping animals might suffer or cause harm, e.g., by entering a highway, with ensuing liability and insurance issues. Second, virtual fences affect only the equipped farm animals, but do not prevent trespassing by humans, dogs or predators:

Practitioner: Personally, I think it is an insurance issue. For example, the herd is on a pasture close to a highway. In the middle of the night, the wolf shows up. The herd runs off without physical fences protecting it. How can the farmer ensure that the insurance takes effect in the event of a car accident? (Source 01, translated from German by the authors)

(2) Aligning visions: This style of reflexive learning describes an interaction in which practitioners’ claims are evaluated by scientists as relevant, but already known and well-considered, though not in the specific context. Such an interaction can imply low problem tractability and actor certification. Treating the technological innovations as boundary objects implies that practitioners are treated as an independent and valuable source of knowledge. Their perspectives and contributions not only enhance complexity, but are also necessary to understand how the innovations could become relevant for potential users. Aligning visions in our case is exemplified by the issue of grass growth monitoring (Sources 02, 04, 05, 08). Remote sensing provides information on biomass growth on grasslands at spatial resolutions that are lower but more easily accessible when based on satellite data and higher but harder to acquire when based on data from drones. Both types of data allow real-time assessments of plots regarding their suitability for grazing or cutting and can thereby support management decisions. Practitioners were familiar with this line of reasoning from arable farming and spontaneously suggested to utilise the technology for grasslands. Technology developers, however, already pursued this goal:

Practitioner: We know from arable farming that the industry increasingly offers to provide satellite-based information, e.g., the Leaf Area Index, and that applications are based on this. Something similar would be appropriate here.

Scientist: Yes, that is exactly what our software aims at. Those are ecological and agronomical information. Using drones and satellites, we can get this information. (Source 02, translated from German by the authors)

(3) Managing expectations: In this style of reflexive learning, practitioner input is regarded as relevant and novel, but less feasible by scientists. Discussing limitations contributes to manage practitioners’ expectations. Still, collecting and assessing requirements and adjustments based on practical knowledge is useful for further development. It implies low certification and low tractability since practitioners’ suggestions are acknowledged and systematically recorded, opening the design process for additional perspectives and experiences. An example is the integration of additional data sources into a decision support software (Sources 02, 06, 08, 09). The application was expected to address several tasks, most importantly describing the current state of grassland and livestock based on data from virtual fencing collars and remote sensing systems, but also conducting optimisation calculations to support management decisions. Designed as a management instrument, it also provides an interface for positioning virtual fences. While practitioners were creative in imagining use cases, they focused on the integration of additional data like the position of animals to extend monitoring and to include further parameters into yield estimates. The scientists perceived the integration of animal movement data to display grazing patterns and to derive management recommendations as creative and meaningful, but also as challenging to implement:

Practitioner: Integrating patterns of movement of the animals would be very interesting. Where are the animals at night? Where do they stay at which time of the day? This would allow to identify intensity on the land.

Scientist: I would like to add immediately that currently it is not planned to integrate that in the software. One reason is that doing this would of course include generating rather high volumes of data. (Source 02, translated from German by the authors)

(4) Co-creating innovations: In this style of reflexive learning, scientists and practitioners agree on the relevance, novelty and feasibility of a suggestion. In our case study, typically practitioners proposed alterations to the scientific innovation in order to enhance its practical value, which scientists assessed as feasible. One example are design suggestions for the virtual fencing devices with which the animals are equipped to enable GPS-based tracking and signalling (Sources 03, 05, 06, 09). Designed as collars, these most tangible boundary objects could be inspected, carried around and tested by participants during on-site trials. During and after the hands-on presentation, ideas and concerns were generated by practitioners regarding possible utilizations. But also design issues like weight and fit with the size of individual animals were considered. If collars were too tight or too loose, animals might be trapped in brushwood when branches get caught in the device – a concern known from physical fencing. Regarding the collar’s functioning, battery life and water resistance were discussed:

Practitioner A: What if it [the collar] is under water in the troughs? […] If we have a large trough and they [the animals] are drinking, it will be under water.

Scientist A: We did not have any problems with that.

Practitioner B: But if they [the animals] are drinking from a large basin or a lake, it [the collar] goes completely under water. […]

Scientist B: It is waterproof – the device. […]

Practitioner A: But water-repellent or waterproof?

Scientist A: Yes, indeed. It meets the standard. It is definitively water-repellent. (Source 05, translated from German by the authors)

Discussion and conclusion

Building on the varieties of learning approach, this paper introduced the concept of learning mode misfits based on the two dimensions of actor certification and problem tractability. This allowed to distinguish four types of learning mode misfits which originate in over- or undervaluation of actor certification and problem tractability: a tacit lack of plurality, guidance, insight, or ease. Combinations of misfits in the two dimensions provide twelve different types of inadequate learning modes which require different remedies. One learning mode misfit, a combination of overvaluation of certification and tractability, is likely to occur in contexts of socio-technical transitions. The typology of misfits would suggest here to enable reflexive learning by reducing inadequate problem tractability and actor certification. In order to realise and thereby investigate this remedy, a co-creation intervention of precision grassland farming technologies was analysed. Living labs, building on extensive actor networks, and the use of technology concepts and prototypes as boundary objects opened up the learning process and enabled reflexive learning. An inductive analysis of the interactions between participating practitioners and scientists found four distinct styles of reflexive learning: reconsidering scopes, aligning visions, managing expectations, and co-creating innovations. These four modes reflect different assessments of the relevance, novelty and feasibility of stakeholder suggestions by scientists. Hence, the case demonstrates how inclusive learning arrangements can principally reduce inadequate actor certification and problem tractability and thereby shift from a hierarchical to a reflexive learning environment.

Our results suggest that problem tractability and actor certification are interdependent. A tacit lack of plurality can be addressed by opening up learning processes where participants meet as equals, but this implies multiplying the sources of legitimate knowledge claims and objections. Vice versa, a tacit lack of insight requires opening up the problem description, which will lead to more complex system descriptions and the call to involve further actors who then cannot be reduced to passive receivers of solutions, but need to be empowered as co-creators of knowledge and design. Understanding problem tractability and actor certification as interdependent resonates with previous findings on epistemic learning. Analogous reasoning (Beach et al., Citation2021) results from an overvaluation of problem tractability, but a pluralisation of perspectives would challenge incumbent epistemic authorities. Similarly, capacity constraints interrupt the link between reasoning and crafting policy solutions (Dunlop, Citation2017), which could be addressed by pluralising the policy design process. Our research also ties in with earlier work on learning and legitimacy. The joint experimentation with innovations reverberates with calls to engage in prototyping of technologies and policies to foster interactive and reflexive learning processes (Sanderson, Citation2002). Instead of limiting an investigation of learning processes to their input and output legitimacy, a shaping of learning environments towards more engaging and participatory contexts also contributes to enhanced throughput legitimacy (Schmidt, Citation2013).

Given the complexity and variety of learning processes, our argument is unavoidably limited in at least four respects. First, although it has been shown that the concept of learning mode misfits is highly useful to conceptualise shifts between learning modes documented in existing case studies, further applications of the concept in genuine cases of policy learning are needed. Competing interests and diverging ideas – though also relevant in socio-technical transition – may be even more pronounced in other policy areas. Second, the links between inadequate learning environments (learning mode misfits) and ‘bad’ learning outcomes (policies lacking effectiveness, efficiency and/or legitimacy) need to be further investigated. Establishing links between specific learning mode misfits and specific types of policy failure would allow to identify patterns and sources of dysfunctional learning modes. Third, our proposition that actor certification and problem tractability are overvalued in contexts of socio-technical transitions needs to be empirically tested, also for other technocratic policy-making contexts. This is particularly important as our material is limited to a learning environment already shaped by living labs and boundary objects and therefore captures the shift rather than the initial misfit. At the same time, future research should also investigate contrasting cases with tacit lack of guidance or ease where expertise is insufficiently valued and problems are over-complicated by pointless deliberation. Finally, anchoring our distinction between different styles of reflexive learning in experts’ assessments indicates that resource and knowledge asymmetries remain significant even if actor certification is reduced. We expect such asymmetries to also matter in other participatory contexts, in particular where learning is structured around a proposition made by experts. Future research should therefore not only extend to different types of learning mode misfits, but also to possible deficiencies within each mode of policy learning. Case studies are therefore a promising avenue for developing a fuller understanding of all varieties of policy learning.

Acknowledgements

We thank the organisers and participants of the Policy Learning Workshop at the IWPP 3 in Budapest in 2022, who provided helpful feedback on an earlier version of this paper. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for instructive comments and suggestions that helped improving the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Malte Möck

Malte Möck is a research associate in the Agricultural and Food Policy Group at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Peter H. Feindt

Peter H. Feindt is a professor and head of the Agricultural and Food Policy Group at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

References

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley.

- Bandelow, N. C. (2008). Government learning in German and British European policies. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 46(4), 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2008.00805.x

- Bandelow, N. C., Vogeler, C. S., Hornung, J., Kuhlmann, J., & Heidrich, S. (2019). Learning as a necessary but not sufficient condition for major health policy change: A qualitative comparative analysis combining ACF and MSF. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 21(2), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2017.1393920

- Beach, D., Schäfer, D., & Smeets, S. (2021). The past in the present—The role of analogical reasoning in epistemic learning about how to tackle complex policy problems. Policy Studies Journal, 49(2), 457–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12372

- Bengtsson, J., Bullock, J. M., Egoh, B., Everson, C., Everson, T., O'Connor, T., O'Farrell, P. J., Smith, H. G., & Lindborg, R. (2019). Grasslands—More important for ecosystem services than you might think. Ecosphere, 10(2), e02582. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2582

- Bennett, C. J., & Howlett, M. (1992). The lessons of learning: Reconciling theories of policy learning and policy change. Policy Sciences, 25(3), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138786

- Boon, W. P. C., & Bakker, S. (2016). Learning to shield – Policy learning in socio-technical transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 18, 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.06.003

- Bronson, K., & Knezevic, I. (2016). Big data in food and agriculture. Big Data & Society, 3(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716648174

- Bulkeley, H., Coenen, L., Frantzeskaki, N., Hartmann, C., Kronsell, A., Mai, L., Marvin, S., McCormick, K., van Steenbergen, F., & Voytenko Palgan, Y. (2016). Urban living labs: Governing urban sustainability transitions. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 22, 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.02.003

- Chevalier, J. M., & Buckles, D. J. (2019). Participatory action research (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Coleman, W. D., Skogstad, G. D., & Atkinson, M. M. (1996). Paradigm shifts and policy networks: Cumulative change in agriculture. Journal of Public Policy, 16(3), 273–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00007777

- Compagnucci, L., Spigarelli, F., Coelho, J., & Duarte, C. (2021). Living labs and user engagement for innovation and sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 289, 125721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125721

- Crow, D. A., Albright, E. A., Ely, T., Koebele, E., & Lawhon, L. (2018). Do disasters lead to learning? Financial policy change in local government. Review of Policy Research, 35(4), 564–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12297

- Daviter, F. (2019). Policy analysis in the face of complexity: What kind of knowledge to tackle wicked problems? Public Policy and Administration, 34(1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076717733325

- Duncan, E., Glaros, A., Ross, D. Z., & Nost, E. (2021). New but for whom? Discourses of innovation in precision agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values, 38(4), 1181–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10244-8

- Dunlop, C. A. (2017). Pathologies of policy learning: What are they and how do they contribute to policy failure? Policy & Politics, 45(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557316X14780920269183

- Dunlop, C. A., James, S., & Radaelli, C. M. (2020). Can’t get no learning: The Brexit fiasco through the lens of policy learning. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(5), 703–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1667415

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2013). Systematising policy learning: From monolith to dimensions. Political Studies, 61(3), 599–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00982.x

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2016). Policy learning in the Eurozone crisis: Modes, power and functionality. Policy Sciences, 49(2), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-015-9236-7

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2018a). Does policy learning meet the standards of an analytical framework of the policy process? Policy Studies Journal, 46(S1), S48–S68. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12250

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2018b). The lessons of policy learning: Types, triggers, hindrances and pathologies. Policy & Politics, 46(2), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230059735521

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2022). Policy learning in comparative policy analysis. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 24(1), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2020.1762077

- Etheredge, L. S., & Short, J. (1983). Thinking about government learning. Journal of Management Studies, 20(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1983.tb00197.x

- European Commission. (2020). Strategic plan 2020–2024 – Agriculture and rural development. Retrieved August 14, 2023, from https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2020-10/agri_sp_2020_2024_en.pdf.

- Feindt, P. H., & Flynn, A. (2009). Policy stretching and institutional layering: British food policy between security, safety, quality, health and climate change. British Politics, 4(3), 386–414. https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2009.13

- Geels, F. W., & Ayoub, M. (2023). A socio-technical transition perspective on positive tipping points in climate change mitigation: Analysing seven interacting feedback loops in offshore wind and electric vehicles acceleration. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 193, 122639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122639

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2007). Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, 36(3), 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

- Goyal, N., & Howlett, M. (2020). Who learns what in sustainability transitions? Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 34, 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.09.002

- Hackfort, S. (2021). Patterns of inequalities in digital agriculture: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(22), 12345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212345

- Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

- Heclo, H. (1974). Modern social politics in Britain and Sweden: From relief to income maintenance. Yale University Press.

- Heclo, H. (1978). Issue networks and the executive establishment. In A. King (Ed.), The new American political system (pp. 87–124). American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Heikkila, T., & Gerlak, A. K. (2013). Building a conceptual approach to collective learning: Lessons for public policy scholars. Policy Studies Journal, 41(3), 484–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12026

- Holmqvist, M. (2016). A dynamic model of intra- and interorganizational learning. Organization Studies, 24(1), 95–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840603024001684

- Howlett, M. (2012). The lessons of failure: Learning and blame avoidance in public policy-making. International Political Science Review, 33(5), 539–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512112453603

- Kenis, A., Bono, F., & Mathijs, E. (2016). Unravelling the (Post-)political in transition management: Interrogating pathways towards sustainable change. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 568–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1141672

- Kivimaa, P., & Sivonen, M. H. (2023). How will renewables expansion and hydrocarbon decline impact security? Analysis from a socio-technical transitions perspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 48, 100744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100744

- Kleinschroth, F., Banda, K., Zimba, H., Dondeyne, S., Nyambe, I., Spratley, S., & Winton, R. S. (2022). Drone imagery to create a common understanding of landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning, 228, 104571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104571

- Klerkx, L., Jakku, E., & Labarthe, P. (2022). A review of social science on digital agriculture, smart farming and agriculture 4.0: New contributions and a future research agenda. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 90–91(1), 100315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2019.100315.

- Klerkx, L., van Bommel, S., Bos, B., Holster, H., Zwartkruis, J. V., & Aarts, N. (2012). Design process outputs as boundary objects in agricultural innovation projects: Functions and limitations. Agricultural Systems, 113, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2012.07.006

- Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., & Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences, 45(2), 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0

- Lühmann, M., & Vogelpohl, T. (2023). The bioeconomy in Germany: A failing political project? Ecological Economics, 207, 107783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107783

- May, P. J. (1992). Policy learning and failure. Journal of Public Policy, 12(4), 331–354. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00005602

- McConnell, A. (2010). Policy success, policy failure and grey areas in-between. Journal of Public Policy, 30(3), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X10000152

- McNutt, K., & Rayner, J. (2018). Is learning without teaching possible? The productive tension between network governance and reflexivity. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(6), 769–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2014.986568

- McPhee, C., Bancerz, M., Mambrini-Doudet, M., Chrétien, F., Huyghe, C., & Gracia-Garza, J. (2021). The defining characteristics of agroecosystem living labs. Sustainability, 13(4), 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041718

- Metze, T. A. P., & Van Zuydam, S. (2018). Pigs in the city: Reflective deliberations on the boundary concept of Agroparks in The Netherlands. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(6), 675–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2013.819780

- Millar, H. (2020). Problem uncertainty, institutional insularity, and modes of learning in Canadian provincial hydraulic fracturing regulation. Review of Policy Research, 37(6), 765–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12401

- Moyson, S. (2017). Cognition and policy change: The consistency of policy learning in the advocacy coalition framework. Policy and Society, 36(2), 320–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1322259

- Moyson, S., Scholten, P., & Weible, C. M. (2017). Policy learning and policy change: Theorizing their relations from different perspectives. Policy and Society, 36(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1331879

- Oliver, M. J., & Pemberton, H. (2004). Learning and change in 20th-century British economic policy. Governance, 17(3), 415–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00252.x

- Pattison, A. (2018). Factors shaping policy learning: A study of policy actors in subnational climate and energy issues. Review of Policy Research, 35(4), 535–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12303

- Pe'er, G., Bonn, A., Bruelheide, H., Dieker, P., Eisenhauer, N., Feindt, P. H., Hagedorn, G., Hansjürgens, B., Herzon, I., Lomba, Â., Marquard, E., Moreira, F., Nitsch, H., Oppermann, R., Perino, A., Röder, N., Schleyer, C., Schindler, S., Wolf, C., .... Lakner, S. (2020). Action needed for the EU common agricultural policy to address sustainability challenges. People and Nature, 2(2), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10080

- Pierson, P. (1993). When effect becomes cause: Policy feedback and political change. World Politics, 45(4), 595–628. https://doi.org/10.2307/2950710

- Riche, C., Aubin, D., & Moyson, S. (2021). Too much of a good thing? A systematic review about the conditions of learning in governance networks. European Policy Analysis, 7(1), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1080

- Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Rogers, K. H., Luton, R., Biggs, H., Biggs, R., Blignaut, S., Choles, A. G., Palmer, C. G., & Tangwe, P. (2013). Fostering complexity thinking in action research for change in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 18(2), 31. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05330-180231

- Rose, R. (1991). What is lesson-drawing? Journal of Public Policy, 11(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00004918

- Sabatier, P. A. (1987). Knowledge, policy-oriented learning, and policy change. Knowledge, 8(4), 649–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164025987008004005

- Saldana, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Sanderson, I. (2002). Evaluation, policy learning and evidence-based policy making. Public Administration, 80(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00292

- Sandström, A., Morf, A., & Fjellborg, D. (2021). Disputed policy change: The role of events, policy learning, and negotiated agreements. Policy Studies Journal, 49(4), 1040–1064. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12411

- Scharpf, F. W. (1997). Games real actors play: Actor-centered institutionalism in policy research. Westview Press.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and Legitimacy in the European Union revisited: input, output and ‘throughput’. Political Studies, 61(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x

- Smith, A., & Stirling, A. (2010). The politics of social-ecological resilience and sustainable socio-technical transitions. Ecology and Society, 15(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03218-150111

- Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley's Museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

- Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. (2011). Agrarstrukturen in Deutschland. Einheit in Vielfalt. Regionale Ergebnisse der Landwirtschaftszählung 2010.

- Stirling, A. (2010). Keep it complex. Nature, 468(7327), 1029–1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/4681029a

- Trein, P., & Vagionaki, T. (2022). Learning heuristics, issue salience and polarization in the policy process. West European Politics, 45(4), 906–929. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1878667

- Van Mierlo, B., & Beers, P. J. (2020). Understanding and governing learning in sustainability transitions: A review. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 34, 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2018.08.002

- Vogeler, C. S. (2019). Yet another paradigm change? Narratives and competing policy paradigms in Brazilian labour market policies. Policy and Society, 38(3), 429–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2019.1652954

- Wagenaar, H. (2007). Governance, complexity, and democratic participation. The American Review of Public Administration, 37(1), 17–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074006296208

- Weible, C. M., Olofsson, K. L., & Heikkila, T. (2023). Advocacy coalitions, beliefs, and learning: An analysis of stability, change, and reinforcement. Policy Studies Journal, 51(1), 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12458

- Zaki, B. L., Wayenberg, E., & George, B. (2022). A systematic review of policy learning: Tiptoeing through a conceptual minefield. Policy Studies Yearbook, 12(1), 1–52. https://doi.org/10.18278/psy.12.1.2.