ABSTRACT

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 resulted in the largest refugee crisis in Europe since WWII. Using a unique panel conjoint experiment on refugee policy preferences carried out in Germany, Poland and Hungary just before and after the onset of the war in Ukraine, we show a heterogenous response to the influx of refugees from Ukraine across the three countries: no change of policy preferences in Germany, moderate change in Hungary and a significant change in Poland. Our results have direct implications for the development of a common EU asylum policy, as even though the countries persistently diverge on the preferred mode of asylum seekers’ allocation, with Germans favouring relocation and Poland and Hungary the status quo, the results highlight the scope for consensus rooted in shared preference for the asylum seekers’ unrestricted access to the labour market. This dimension consistently emerges as the most important policy dimension in all three countries before and after the outbreak of war.

Introduction

In early 2022, following the outbreak of war in Ukraine, millions of Ukrainians crossed the country’s western border, with around 1.5 million seeking shelter in Poland, 1 million in Germany and 750,000 in Hungary.Footnote1 They were met with an unprecedented wave of grassroots solidarity and support across all three of these EU Member States (e.g., 0.38 per cent of GDP in private transfers towards refugees in Poland [Baszczak et al., Citation2022]), which stands in stark contrast to the popular perception of Polish and Hungarian citizens as xenophobic and opposing immigration (Barna & Koltai, Citation2019; Thérová, Citation2023; van der Brug & Harteveld, Citation2021). The most often used explanation for this paradox is that Ukrainian refugees are a ‘different kind of refugee’ than those who constituted the majority of asylum seekers in 2015, and as such they are perceived more as in-group than out-group members by the receiving societies (De Coninck, Citation2020; Paré, Citation2022).

In this paper, we ask whether the outbreak of war in the EU-neighbouring country – Ukraine – and the resulting unprecedented influx of refugees has had an effect on citizens’ refugee policy preferences in Germany, Poland and Hungary. Recent literature shows that general attitudes towards immigrants and asylum seekers as a group tend to be stable over time (Dennison et al., Citation2023; Kustov et al., Citation2021; Lancaster, Citation2022; Stockemer et al., Citation2020), yet there is also considerable evidence for a negative backlash following an increase in asylum seekers’ arrivals (Hangartner et al., Citation2019; Liebe & Schwitter, Citation2021; Jäckle & König, Citation2017; Nordø & Ivarsflaten, Citation2022). Much less is known about the dynamic of refugee policy preferences, and the current refugee crisis has created conditions different to the previous, 2015, refugee crisis in terms of proximity of war and refugees’ ethnic and socio-economic profiles. Using unique data from a conjoint experiment focused on refugee policy carried out on nationally quota-representative samples in Germany, Poland and Hungary immediately before and after the outbreak of war, we address the question about the stability and change of refugee policy preferences in the context of the war in Ukraine and the resultant refugee crisis in three European countries that reacted very differently to the previous refugee crisis of 2015, and whose position towards Russia in the context of the current crisis also differs, even though they all applied unified policy measures to Ukrainian refugees. Our results show that citizens in all three countries had very similar – fairly open and hospitable – preferences on refugee policy already prior to the outbreak of the war, and the influx of refugees from Ukraine has left these preferences unchanged in Germany, but led to a varying degree of change in Hungary and Poland. We also show that after the outbreak of war, in Germany citizens who believe that Ukrainian war refugees should receive special treatment do not differ in their refugee policy preferences from those who want equal treatment of all war refugees, while in Poland and Hungary these expectations to an extent structure refugee policy preferences. Our results are broadly consistent with recent research on Europeans’ preferential treatment of Ukrainian refugees (Bansak et al., Citation2023; Moise et al., Citation2024, Pepinsky et al., Citation2022), but we also show different dynamics of policy preferences in each country. Beyond that, our results have direct implications for the development of a common EU asylum policy, as they highlight the scope for consensus rooted in the asylum seekers’ open access to the labour market, which is consistently the most important policy dimension in all three countries before and after the outbreak of war.

Refugee policy in the European Union

The previous refugee crisis in 2015 revealed a deep rift among Member States in respect to refugee policy, with some governments (e.g., Poland and Hungary) openly refusing to assist the overburdened Member States by accepting relocated refugees, while others (e.g., Germany) decided to keep their borders open (Goodman & Schimmelfennig, Citation2020; Zaun, Citation2022). The anti-immigration and anti-refugee political discourse – racialising and emphasising the ‘otherness’ of refugees – had been employed by the right-wing populist Law and Justice and Fidesz parties in, respectively, Poland and Hungary to mobilise voter support (Bíró-Nagy, Citation2022; Krzyżanowski, Citation2020; Pszczólkowska, Citation2022), while in Germany public discourse focused on the volume of immigration and management issues, and refugee policy became more liberal than ever before (Fotopoulos & Kaimaklioti, Citation2016; Funk, Citation2016; Laubenthal, Citation2019). The 2022 refugee crisis spurred an entirely different response from the governments in Warsaw and Budapest, while Berlin continued its liberal policy and ‘welcoming culture’ approach. The change in the political stance of the Polish and Hungarian governments and the high level of grassroots support for Ukrainian refugees across Europe have been interpreted as an example of ethnically motivated hypocrisy, especially in the context of an ongoing humanitarian crisis at the Poland-Belarus border or the plight of refugees trying to reach Europe by crossing the Mediterranean Sea or via the so-called Balkan Route (De Coninck, Citation2020; Klaus & Szulecka, Citation2023; Kyriazi, Citation2022; Paré, Citation2022; Thérová, Citation2023; Tondo, Citation2022). This view seems to be corroborated by the Polish and Hungarian governments’ renewed protests against the relocation mechanisms based on the New Pact on Migration and Asylum discussed by the EU Parliament in June 2023 (Tilles, Citation2023). Despite the similarly EU-sceptical positions of Poland and Hungary and welcoming policy towards Ukrainian refugees, they differ in their attitudes towards Russia, with Poland consistently anti-Russian and Hungary openly pro-Putin (Durakçay, Citation2023; Zoltan, Citation2023).

Refugee policy dimensions

Given the politicisation of the management of asylum seekers’ flows during the 2015 refugee crisis (Gianfreda, Citation2018; Krzyżanowski, Citation2020; Triandafyllidou, Citation2018), research on immigration and refugee policy preferences has focused predominantly on the issues of control over admission of asylum seekers, thus eliciting opinions on border control and relocation mechanisms, but also family reunification and agreements with third countries (Abdelaaty & Steele, Citation2022; Heizmann & Ziller, Citation2020; Jeannet et al., Citation2021; Van Hootegem et al., Citation2020). Based on this research, as well as the literature on drivers of backlash against asylum seekers’ increased presence in the receiving countries more broadly (Kustov, Citation2023a), and the currently available policy options across the EU Member States (Jeannet et al., Citation2021), including the key provisions of the EU Temporary Protection Directive, several policy dimensions come to the forefront as most salient: (i) allocation of asylum seekers among the Member States, (ii) control of EU borders, (iii) asylum seekers’ access to the labour market, (iv) asylum seekers’ freedom of movement, and (v) the policy cost for an average taxpayer. Previous research has found varying support for proportional allocation of asylum seekers (Letki et al., Citation2023), conditional on the consequences of reallocation for the number of asylum seekers accepted by a given country (Bansak et al., Citation2017). However, the currently proposed New Pact on Migration and Asylum includes also an option of fiscal solidarity – taking financial responsibility for failed asylum applicants’ return to their country of departure instead of accepting relocated refugees, although this solution has not found much support in Europe (Letki et al., Citation2023). It has also been found that Europeans are generally in favour of increased border control, as they want to limit the number of refugees (Jeannet et al., Citation2021), and that an increase in border control conditions the willingness to accept relocated asylum seekers (Vrânceanu et al., Citation2023). Despite refugees and asylum seekers being perceived as labour competition by some social groups (Malhotra et al., Citation2013), there is evidence for wide support across Europe for their full participation in the labour market, consistent with concerns over a refugee-related welfare strain on the receiving societies (Letki et al., Citation2023). Consistent with research identifying perceptions of refugees and asylum seekers as a threat, both culturally and in terms of security (Kende et al., Citation2019), Europeans generally prefer them to live in a designated place and enjoy only limited freedom of movement (Letki et al., Citation2023). Finally, policy cost is a relevant factor, as European citizens would like to spend as little as possible on supporting refugees (Letki et al., Citation2023).

However, all the studies cited above were carried out before the current refugee crisis, and so far there is no evidence as to how the outbreak of war and the resultant inflow of refugees, as well as the introduction of the Temporary Protection DirectiveFootnote2 – that gives Ukrainian refugees residence rights along with access to the labour market and to welfare – have affected European citizens’ preferences regarding key dimensions of refugee policy. The only study that assesses general levels of support for the Temporary Protection Directive over time shows positive attitudes that declined with time, indicating an initial ‘rallying’ around support for Ukrainian refugees (Moise et al., Citation2024). However, both waves of the study conducted by Moise et al. (Citation2024) were carried out after the outbreak of war; thus, they lack a benchmark for capturing the effect of war.

Dynamics of preferences under the crisis

With the exception of the work of Moise et al. (Citation2024), where respondents were asked about general support for the Temporary Protection Directive, there is virtually no research on the dynamics of refugee policy preferences in the context of a crisis, even though the experience of economic strain related to the increased presence of refugees in the receiving countries, direct contact in everyday situations, as well as a change in policy and political messaging on the issues of asylum are all likely to affect the public’s expectations in respect to refugee policy. Results from research on the stability and change of more general attitudes towards immigrants and asylum seekers are fairly mixed. On the one hand, recent studies demonstrate that attitudes towards immigrants are remarkably stable over time and resistant to major political and economic shocks, such as the 2008 recession, Brexit, the 2015 refugee crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic (Dennison et al., Citation2023; Lancaster, Citation2022; Kustov et al., Citation2021; Stockemer et al., Citation2020). In addition, experimental research corroborates conclusions about the stability of immigration attitudes based on surveys by showing that they are generally unsusceptible to informational cues (Barrera et al., Citation2020; Hopkins et al., Citation2019).

On the other hand, there is considerable evidence for short-term increases in negative attitudes and behaviour towards refugees and asylum-seekers under the strain of their influx into the receiving country (Hangartner et al., Citation2019; Jäckle & König, Citation2017; Liebe & Schwitter, Citation2021; Nordø & Ivarsflaten, Citation2022), while panel studies covering long periods of time suggest that exogenous shocks allow political actors to affect the salience of the immigration issue and to mobilise segments of the right-wing electorate around negative sentiments by questioning asylum seekers’ deservingness (Bíró-Nagy, Citation2022; Kustov, Citation2023b; Kustov et al., Citation2021; Schmidt-Catran & Czymara, Citation2023; van der Brug & Harteveld, Citation2021). There is also evidence that anti-immigration political appeals get traction among some segments of the electorate, while other groups do not prioritise this policy dimension (Kirkizh et al., Citation2022; Kustov, Citation2023a). Studies taking into account the impact of the war in Ukraine show that an overall acceptance of refugees has significantly increased since its outbreak, and that the driving force behind that is the presence of Ukrainian refugees (Bansak et al., Citation2023; Moise et al., Citation2024). On the other hand, attitudes are stable in that asylum seekers’ language skills, gender, professional qualifications and religion are the driving factors behind their acceptance in the receiving countries both before and after the outbreak of war (Bansak et al., Citation2023).

However, the 2022 war and the resultant refugee crisis are distinctive in comparison with previous events (such as the 2008 economic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic or even the 2015 refugee crisis) in three important and interrelated aspects. First, they present an unprecedented degree of an immediate military threat – in March 2022, 86 per cent Poles, 84 per cent Germans and 67 per cent Hungarians thought that war in Ukraine was a threat to their national security, according to a poll conducted by TGM Research.Footnote3 Second, they have provoked a uniquely unanimous policy response from the Member States in terms of opening borders to refugees and providing special provisions for their access to the labour market and freedom of movement around the EU (Bosse, Citation2022; Freudlsperger & Schimmelfennig, Citation2023), even though their relations with Russia differ between generally pro-Ukraine Germany and Poland on the one hand, and the pro-Putin stance of Hungary on the other. Finally, the refugees crossing the Eastern EU border since February 2022 have a different ‘profile’ from those arriving in Europe during the previous migration waves.

Overall, previous research suggests that while the 2015 refugee crisis provoked a short-term backlash against refugees and asylum seekers in a number of Western European countries, the current crisis is likely to have a different effect given more favourable attitudes towards European refugees with good language and professional skills. Importantly, there is virtually no research on how the specific circumstances of war in Ukraine have affected refugee policy preferences in the receiving countries.

Expectations on treatment of war refugees and policy preferences

Previous research shows that who the asylum seekers are is crucial for the willingness of the public in the receiving countries to accept them and for the shape of refugee policy that can elicit public support. Previous work has precisely documented Europeans’ and North Americans’ preferences regarding the ideal immigrant and asylum seeker: the most preferred profile is that of a woman, Christian, with good professional and language skills (Adida et al., Citation2018; Bansak et al., Citation2016; Hainmueller & Hopkins, Citation2015; Sobolewska et al., Citation2017; Weiss, Citation2013), and these preferences have not been affected by the war in Ukraine (Bansak et al., Citation2023). The 2015 refugee crisis has contributed to creating a public perception of an asylum seeker as a young Muslim man with poor education and language skills, posing a cultural, economic and security threat, and as such representing everything that the ‘preferred’ asylum seeker is not (Dancygier et al., Citation2022; Ward, Citation2019).Footnote4 This threatening profile was subsequently exploited by conservative and right-wing political parties mobilising political support around the issue of immigration flows control (Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2022).

The refugee crisis following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 has challenged the refugee profile coined in the public discourse during the 2015 refugee crisis. By mid-February 2023, Member States had received approximately 4.7 million war refugees, whose ‘profile’ was an almost exact match for the preferences captured by the research cited above: in most countries at least 70 per cent of adult refugees from Ukraine are women, and while there are no complete statistics on their socio-economic profile, available data suggests that at least 60 per cent of Ukrainian refugees have a Master’s degree or higher, while their professional skills are largely relevant for the European labour market.Footnote5 Even though the fact that around a third of refugees are children makes their mothers’ and carers’ labour market participation fairly difficult, a recent survey in Poland shows that around 55 per cent of Ukrainian refugees’ income comes from employment and 45 per cent from welfare support (Górny & Kaczmarczyk, Citation2023), while their participation in the labour market is relatively high in comparison with other recently arrived refugee groups (an EU average is 25 per cent for refugees in the first five years of their stay, and while in Germany only 17 per cent of Ukrainian refugees work, in Poland this number is as high as 70 per cent [McMahon, Citation2023]).

Given the change in the socio-economic and ethnic profile of refugees arriving in Europe, policy preferences might have changed not as a result of an exposure to the refugee crisis per se, but as a result of a different refugee profile post-February 2022. This expectation is supported by the fact that Ukrainians are consistently preferred over other groups of asylum seekers, such as Syrians, Afghanis or Iraqis (Bansak et al., Citation2023; Moise et al., Citation2024, Pepinsky et al., Citation2022), while political messaging tends to portray refugees from the Global South as ‘economic migrants’ and contrast them with the ‘genuine’ and ‘familiar’ refugees from Ukraine (Klaus & Szulecka, Citation2023; Kyriazi, Citation2022; Paré, Citation2022). Therefore, we expect that whether respondents expect preferential treatment for Ukrainians or want equal treatment of all war refugees, structures their refugee policy preferences after the outbreak of war.

To summarise, the main contribution of this article centres on two research questions, namely (1) Have refugee policy preferences in Germany, Poland and Hungary changed as a result of the outbreak of war in Ukraine and the resultant influx of refugees? and (2) Do refugee policy preferences differ among Europeans depending on whether they expect preferential treatment for Ukrainian refugees or not? While answers to these questions contribute to our grasp of the current refugee crisis, they also have broader implications for our understanding of more general citizen expectations on refugee policy and how they can be addressed by a common asylum policy design.

Materials and methods

In this study, we use data collected during an online survey experiment on quota-representative national samples in Poland, Germany and Hungary prior to and after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. The three listed countries represented radically different levels of openness during the 2015 refugee crisis. They have also experienced a substantial influx of refugees from Ukraine, following the Russian invasion.Footnote6 Our initial survey was carried out between 11 January and 11 February 2022 (N = 958). Following the onset of the war in Ukraine and the emergence of a refugee crisis we carried out second fieldwork between 25 April and 12 May 2022. The second wave consisted of two independent groups of respondents: (i) a new quota-representative national sample collected in each of the three countries (N = 1280) and (ii) re-contacted respondents who took part in the first wave of the study (N = 817).Footnote7 The first wave was a part of a larger survey carried out in 10 Member States (N = 16,976): Germany, Poland, Hungary, Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Bulgaria, Croatia, Slovenia and Austria, but we faced budget constraints for the repeated study in April/May. Thus, we decided to focus on those countries in our sample that were most exposed to the refugee crisis following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and, more broadly, exposed to the flow and settlement of migrants and refugees in recent years across the EU.Footnote8 We have not pre-registered any hypotheses in respect to the second wave of the study.

In our analysis we make two types of comparisons: first, to track the dynamics of policy preferences over time we investigate the data from two nationally representative and independently collected samples and compare the responses collected in the first wave (i.e., before the outbreak of the war) with the second wave of the study (i.e., after the outbreak of the war). Second, we test the within-respondent dynamic of policy preferences and analyse the change in the responses of respondents who took part in the first wave (before the war) and decided to answer our call to complete the survey again, after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine (the analysis included in the Appendix).Footnote9 It is important to note that these ‘re-contact respondents’ are not included in the independent samples data from the second wave of the survey described above, as these samples result from two separate (although concurrent) data collection processes (for details of sample construction see the Appendix).

Finally, in this article, we use two components from our survey: a conjoint experiment on preferences towards refugee policy conducted both before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and a question focusing specifically on the influx of Ukrainian refugees added to the second wave of the survey (for details on the conjoint experiment see the Pre-Analysis Plan at https://osf.io/dxkzn). It is noteworthy that the second wave of the survey mirrored the first wave in all aspects, bar the questions on special treatment of refugees added at the very end of the second survey (i.e., where the first wave of the survey ended).

Conjoint experiment

We elicited preferences towards refugee policy through a fully randomised conjoint experiment, which is a design routinely used to study attitudes towards immigrants and asylum seekers (Adida et al., Citation2019; Bansak et al., Citation2016; Hainmueller & Hopkins, Citation2015) as well as general policy preferences (Bechtel et al., Citation2020; Nicoli et al., Citation2020), and more recently also immigration and refugee policy preferences (Jeannet et al., Citation2022; Vrânceanu et al., Citation2023; Letki et al., Citation2023). In our conjoint experiment we have included five policy attributes based on the recent European Commission’s Flexible Solidarity policy proposal (i.e., New Pact on Migration and Asylum) and previous research on refugee policy (Bansak et al., Citation2017; Jeannet et al., Citation2021), as outlined in an earlier section on refugee policy in the European Union.Footnote10 These are: (i) allocation of refugees among Member States, where the available options are status quo, relocational solidarity (Member States help other Member States overburdened with asylum applications by accepting relocated asylum applicants) and fiscal solidarity (Member States help overburdened Member States by paying for the failed applicants to be returned home), (ii) EU border control – maintaining the current level or increasing it, (iii) refugees’ right to work – no right to work, right to take any job or right to take a job no one else wants, (iv) refugees’ freedom of movement within the country or being confined to a special place, and (v) three levels of the policy’s yearly cost for an average household. Incidentally, two out of three ‘domestic’ policy dimensions reflect the key provisions of the EU Temporary Protection Directive that has granted Ukrainian refugees unlimited access to the labour market and full freedom of movement within the EU. As a result, our conjoint experiment closely captures refugee policy options currently in place across EU Member States. summarises the attributes and their levels.

Table 1. Overview of the policy profile attributes and levels.

The conjoint was placed at the beginning of the survey – following a general introduction, quota-related demographic questions, and a short explanation of the terms ‘refugee’ and ‘refugee policy’. Respondents were asked to choose six times one policy profile from a set of two and rate each of them on a scale from one to seven (Figure S.1, in the Appendix, shows an example of a choice set). The design results in a full factorial of 108 different policy profiles, and the experiment included overall 42,504 profiles (3542 respondents x 12 profiles) shown to respondents – both the representative samples and the re-contact sample – in Germany, Poland and Hungary, who made a total of 21,252 choices (3542 respondents x 6 choices), on average making a choice and assigning a rating for each possible policy profile 394 times. Following each choice, respondents were asked to rate each compared policy on a scale from ‘1’ (very bad) to ‘7’ (very good). Given the comparative character of our inferences, for policy preferences analysis we depict and discuss Marginal Means (MM), rather than Average Marginal Component Effects (AMCE) (Leeper et al., Citation2020). MM > .5 for a given policy attribute will indicate that respondents are in favour of this attribute, MM < .5 will indicate that they disfavour it, while MM = .5 will mean that they are indifferent about it. For the investigation of within-respondent dynamics of preferences, we use policy ratings.

Results

Preferences on refugee policy before and after the outbreak of war in Ukraine

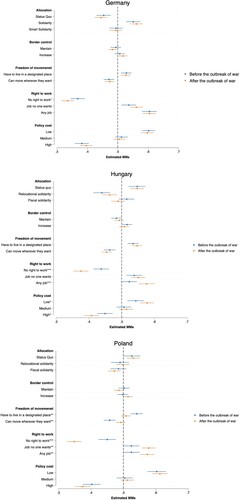

Based on the independent samples data, shows a similar structure of refugee policy preferences (with the exception of allocation of asylum seekers) across the three countries. It also shows a remarkable stability of policy preferences in Germany despite the outbreak of war in Ukraine and an inflow of war refugees between the survey waves into the respective countries, while in Hungary and Poland there is evidence for preferences becoming more favourable towards asylum seekers’ freedom of movement and labour market access. In Germany both before and after the outbreak of the war, respondents’ choices are driven predominantly by the asylum seekers’ right to work. German respondents disfavour when people under the asylum procedure have no right to work (ßbefore = .369, p < .001, 95% CIs (.345, .392) and ßafter = .335, p < .001, 95% CIs (.315, .356)) and this is the only dimension where Germans’ preferences changed as a result of the outbreak of war (at p = .028). They are equally supportive of asylum seekers having full access to the labour market before and after the outbreak (ßbefore = .604, p < .001, 95% CIs (.580, .628) and ßafter = .604, p < .001, 95% CIs (.582, .626)), and so are they equally positive about them having access only to jobs German citizens are not interested in (ßbefore = .537, p = .003, 95% CIs (.513, .560) and ßafter = .561, p < .001, 95% CIs (.541, .582)). Also low cost is a desired policy feature (ßbefore = .602, p < .001, 95% CIs (.580, .623) and ßafter = .598, p < .001, 95% CIs (.576, .619)), while a high cost discourages from choosing a policy profile (ßbefore = .382, p = .003, 95% CIs (.513, .560) and ßafter = .396, p < .001, 95% CIs (.541, .582)). Germans prefer asylum seekers to remain closed in designated facilities (ßbefore = .528, p = .001, 95% CIs (.511, .545) and ßafter = .527, p = .001, 95% CIs (.512, .542)) and would not like a policy giving them freedom of movement (ßbefore = .471, p = .001, 95% CIs (.454, .488) and ßafter = .473, p = .001, 95% CIs (.458, .489)). Finally, EU-level policy dimensions seem to have a weaker impact on policy choice than domestic ones: EU border control is irrelevant for policy choice before the war (ßbefore = .494, p = .458, 95% CIs (.477, .511) for maintaining the current level of control and ßbefore = .506, p = .458, 95% CIs (.490, .523) for increasing it), and becomes weakly significant after the outbreak of war, with respondents favouring an increase of control (ßafter = .517, p = .015, 95% CIs (.503, .531)) and disfavouring the current level of control (ßafter = .483, p = .001, 95% CIs (.469, .497)). Finally, while Germans do have clear preferences regarding allocation policy, these effects are arguably weak: they disfavour the status quo (ßbefore = .454, p < .001, 95% CIs (.430, .477) and ßafter = .445, p < .001, 95% CIs (.424, .466)) and would like to see a policy including relocational solidarity (ßbefore = .551, p < .001, 95% CIs (.528, .574) and ßafter = .561, p < .001, 95% CIs (.540, .583)), while their choices are unaffected by the fiscal solidarity option (ßbefore = .494, p = .618, 95% CIs (.472, .517) and ßafter = .494, p = .546, 95% CIs (.474, .514)).

Figure 1. Refuge policy attributes and the probability of accepting the policy by respondents before and after the outbreak of war – independent samples in Germany, Hungary and Poland: descriptive summary of attributes’ levels computed with Marginal Means. Two nationally quota-representative and independently drawn samples (before and after the war). Dots with horizontal lines are point estimates from linear least squares regressions; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals computed from robust standard errors clustered by respondent. *** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05 Table displaying underlying results, respectively for Germany, Hungary and Poland in both waves, is available in the Appendix in Tables S.2, S.3 and S.4.

In Hungary refugee policy preferences are broadly similar to Germany, albeit not as stable. First, before the outbreak of war policy choice was driven by access to the labour market, cost and – unlike in Germany – allocation, followed by freedom of movement and EU border control. As a result of the outbreak of war, labour market access and policy cost gained more influence on the policy choice, leading to a convergence of preferences among Hungarian respondents (with the exception of allocation) with German respondents. Before the outbreak of war Hungarians disfavoured policy barring asylum seekers access to the labour market, and this preference became stronger after the outbreak of war (ßbefore = .437, p < .001, 95% CIs (.414, .461) and ßafter = .375, p < .001, 95% CIs (.352, .399), difference significant at p < .001). They were equally supportive of them being able to take up jobs Hungarians were not interested in both before and after the outbreak of war (ßbefore = .538, p = .002, 95% CIs (.514, .562) and ßafter = .550, p < .001, 95% CIs (.529, .572)), and were supportive of them having full access to the labour market before the war and became even more in favour of this option after the outbreak of war (ßbefore = .523, p = .058, 95% CIs (.499, .547) and ßafter = .576, p < .001, 95% CIs (.552, .601), difference significant at p = .001). They also became more in favour of policies that were less costly (ßbefore = .543, p = .001, 95% CIs (.518, .568) and ßafter = .578, p < .001, 95% CIs (.556, .599), difference significant at p = .022), more discouraged by a high policy cost (ßbefore = .449, p < .001, 95% CIs (.425, .473) and ßafter = .408, p < .001, 95% CIs (.386, .430), difference significant at p = .013), and remained indifferent to medium-level cost (ßbefore = .507, p = .546, 95% CIs (.484, .530) and ßafter = .514, p = .181, 95% CIs (.493, .536)). Before and after the outbreak of war Hungarians were equally favourable towards asylum seekers living in a designated place (ßbefore = .535, p < .001, 95% CIs (.518, .552) and ßafter = .547, p < .001, 95% CIs (.531, .563)) and disfavoured policies allowing them to move around freely (ßbefore = .463, p < .001, 95% CIs (.445, .481) and ßafter = .454, p < .001, 95% CIs (.438, .470)). Before the outbreak of war they were supportive of an increase of EU border control and not favourable towards maintaining it at the current level (ßbefore = .516, p = .040, 95% CIs (.501, .532) and ßbefore = .516, p = .040, 95% CIs (.501, .532), respectively), but after the outbreak of war their policy choices were no longer affected by the level of EU border control dimension (ßafter = .508, p = .295, 95% CIs (.493, .522) and ßafter = .492, p = .295, 95% CIs (.478, .507), respectively). Finally, in terms of allocation of asylum seekers, Hungarians consistently favour the status quo (ßbefore = .547, p < .001, 95% CIs (.522, .572) and ßafter = .547, p < .001, 95% CIs (.526, .568)) and do not favour relocational solidarity (ßbefore = .439, p < .001, 95% CIs (.414, .465) and ßafter = .463, p = .002, 95% CIs (.441, .486)), while being consistently indifferent about fiscal solidarity (ßbefore = .515, p = .202, 95% CIs (.492, .538) and ßafter = .489, p = .307, 95% CIs (.468, .510)).

Finally, in Poland policy preferences before the outbreak of war were largely similar to Hungary, yet the most important factor was policy cost, followed by access to the labour market and freedom of movement, with, interestingly, EU border control and relocation playing only a minor role. Both before and after the outbreak of war Poles strongly favoured low-cost policies (ßbefore = .603, p < .001, 95% CIs (.574, .631) and ßafter = .613, p < .001, 95% CIs (.589, .636)) and disfavoured high-cost ones (ßbefore = .403, p < .001, 95% Cis (.375, .430) and ßafter = .375, p < .001, 95% CIs (.352, .398)). In the area of access to the labour market, before the war Poles were not in favour of a policy giving no right of work to the asylum seekers, and this preference became significantly stronger after the outbreak of war (ßbefore = .450, p < .001, 95% CIs (.423, .477) and ßafter = .348, p < .001, 95% CIs (.326, .370), difference significant at p < .001). In terms of asylum seekers’ access to any job available or to jobs that Poles were not interested in, before the war Polish respondents were moderately in favour of these solutions, with both effects narrowly missing the conventional statistical significance level (ßbefore = .524, p = .060, 95% CIs (.499, .550) and ßbefore = .525, p = .051, 95% CIs (.500, .549), respectively). After the outbreak of war both versions of labour market access gained significantly more support (ßafter = .574 for ‘any job’, p < .001, 95% CIs (.552, .596) and ßafter = .578 for ‘job no one wants’, p < .001, 95% CIs (.557, .599), respectively), with differences between the waves significant at p = .003 for ‘any job’ and p = .002 for ‘job no one wants’. Before the outbreak of war respondents were supportive of asylum seekers’ living in a designated place and against their moving around freely (ßbefore = .541, p < .001, 95% CIs (.523, .559) and ßbefore = .458, p < .001, 95% CIs (.439, .476), respectively), but this dimension became irrelevant after the outbreak of war (ßafter = .508, p = .277, 95% CIs (.494, .522) and ßafter = .492, p = .278, 95% CIs (.478, .507), respectively), with both changes statistically significant (p = .002 for ‘living in a designated place’ and p = .007 for ‘moving around freely’). EU border control did not significantly affect policy choice before the war (ßbefore = .502, p = .799, 95% Cis (.485, .519) for ‘maintain’ and ßbefore = .498, p = .799, 95% Cis (.482, .514) for ‘increase’), but after the outbreak of war Poles significantly disfavoured maintaining the current level (ßafter = .486, p = .047, 95% CIs (.471, .500)) and favoured increasing border control (ßafter = .515, p = .047, 95% CIs (.500, .529)). Finally, in terms of allocation of asylum seekers among the EU Member States, Poles – like Hungarians and unlike Germans – consistently favour the status quo (ßafter = .526, p = .052, 95% CIs (.500, .530) and ßafter = .530, p = .004, 95% CIs (.510, .550)). However, they are indifferent towards relocational solidarity in both waves (ßbefore = .490, p = .456, 95% CIs (.462, .517) and ßafter = .498, p = .845, 95% CIs (.478, .518)) and became against fiscal solidarity in the second wave (ßbefore = .485, p1 = .221, 95% Cis (.460, .509) and ßafter = .472, p = .004, 95% CIs (.453, .491)).Footnote11

The analysis reported above has been replicated with the use of re-contact data to test the within-respondent dynamic of policy preferences. For this purpose, we have used policy ratings given by respondents on a scale from 1 to 7, where ‘1’ indicates a policy is ‘very bad’ and ‘7’ indicates ‘very good’. Comparison of average ratings of particular policy attributes based on the policy ratings made by the same respondents before and after the outbreak of war shows a strikingly high degree of within-respondent preference stability in Hungary (where no effect is statistically significantly different between the two waves) and little change in Germany, where only fiscal solidarity, full access to the labour market and high policy cost are rated higher after the war. In contrast, in Poland almost all policy dimensions are rated higher after the outbreak of war, with the exception of fiscal solidarity and asylum seekers’ restricted access to the labour market (see Table S.5 in the Appendix), which is consistent with the comparison of independent samples with the use of forced-choice outcome variable, discussed above.

Overall, the comparison of independent samples and analysis of within-respondent dynamics of refugee policy preferences provide evidence for the considerable stability of preferences in Germany, moderate change in Hungary, and a significant change in Poland. Access to the labour market is the most important policy dimension in all three countries, accompanied by a preference for limits on freedom of movement, which in Poland after the war becomes irrelevant for policy choice. No country supports fiscal solidarity either before or after the outbreak of war, while status quo is disfavoured by Germans, favoured by Poles and Hungarians, and the war has no effect on these preferences. Germans would like to see relocational solidarity, Hungarians disfavour this policy solution, while Poles are indifferent about it. The effect of the remaining dimensions is similar across countries and stable over time.

Unequal treatment of refugee groups and policy preferences

When indicating refugee policy preferences during the second wave of our survey, respondents in the three countries were referring to a radically different reality than during the first wave. Not only was this amidst a refugee crisis significantly larger even than in 2015, but also the refugees were different from those arriving during the previous crisis. Given evidence about more favourable attitudes towards Ukrainians than to other groups of refugees, it is important to understand whether the structure of policy preferences differentiates respondents expecting preferential treatment for Ukrainians from those expecting all groups of war refugees being treated the same. To this end, we asked the respondents in the second wave of our survey whether [A] Refugees escaping from the war in Ukraine should receive privileged treatment from [COUNTRY] government, in comparison with other war refugees, or [B] All refugees escaping from war in various countries should be treated by [COUNTRY] government the same way. We believe that those who agree with option A when indicating their policy preferences apply them to Global South war refugees (as Ukrainian refugees constitute a separate category deserving special treatment), while those who agree with option B indicate preferences for a policy that would apply to all war refugees, irrespective of their background.Footnote12

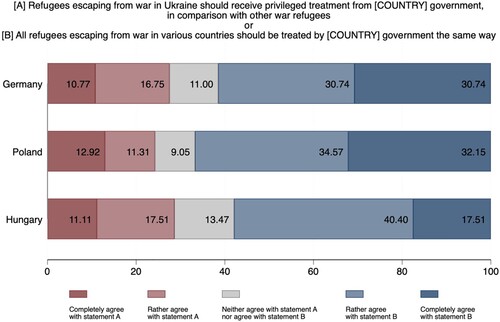

While public opinion on whether there should be one policy for all war refugees or Ukrainian refugees should be treated better than everyone else differs between countries (χ2 = 37.814, p ≤ .001), the majority of respondents in all three countries strongly or moderately agreed with statement B, i.e., that all refugees should be treated the same (Germany: 61.52 per cent, Poland: 65.87 per cent, Hungary: 57.49 per cent), while a minority agreed with statement A (Germany: 28.97 per cent, Poland: 23.56 per cent, Hungary: 28.61 per cent) ().

Figure 2. Public opinion on preferential treatment of Ukrainian refugees, representative wave 2 sample. Germany N = 421, Poland N = 416, Hungary N = 374.

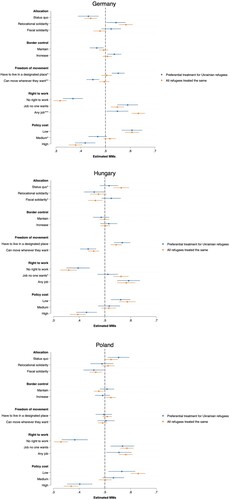

presents refugee policy preferences after the outbreak of war, subsetting the analysis by whether respondents expect preferential treatment for Ukrainian war refugees or want all war refugees treated in the same way. The results reveal that despite an overall divergence of opinion about the treatment of various groups of war asylum seekers, specific policy preferences do not differ much between the two groups. In Germany respondents have different preferences in respect to freedom of movement (ß = -.044, p = .012, 95% CIs (-.079, -.010) for ‘designated place’ and ß = .048, p = .017, 95% CIs (.015, .081) for ‘can move wherever’), full access to the labour market (ß = .092, p < .001, 95% CIs (.042, .142) for ‘any job’) and policy cost (ß = .050, p = .023, 95% CIs (.007, .093) for ‘medium’), but these are differences of degree and not direction, with the exception of freedom of movement, which is irrelevant for policy choice among respondents expecting equal treatment for all war refugees. In Hungary differences are also limited, as respondents who do not differentiate between war refugees based on their country of origin are significantly more in favour of the status quo (ß = .053, p = .029, 95% CIs (.006, .101)) and against fiscal solidarity (ß = -.071, p < .004, 95% CIs (-.118, -.023)), while the other group is indifferent to these dimensions, and respondents preferring equal treatment of war refugees are more in favour of full access to the labour market (ß = .051, p < .04, 95% CIs (.003, .100)). In Poland there are no statistically significant differences related to whether respondents expect equal treatment for all war refugees or differentiate them in relation to their region of origin.

Figure 3. Refuge policy attributes and the probability of accepting the policy by respondents after the outbreak of war in Ukraine: descriptive summary of attributes’ levels computed with Marginal Means. Recontact samples interviewed before and after the outbreak of war. Dots with horizontal lines are point estimates from linear least squares regressions, error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals computed from robust standard errors clustered by respondent. *** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05 Tables displaying underlying results, respectively for Germany, Poland and Hungary, are available in the Appendix in Tables S.6, S.7 and S.8.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper we have analysed how the outbreak of war in Ukraine and a resultant influx of European refugees have affected popular preferences on refugee policy. Previous literature on the dynamics of attitudes towards refugees and asylum seekers in Europe provide evidence for both attitude stability and a negative backlash in reaction to an inflow of asylum seekers, and the specificity of the current refugee crisis in terms of geographical proximity of war, refugees’ ethnic and socio-economic profiles, and a liberal policy applied to them by the EU Member States suggest that the dynamic of refugee policy preferences may differ from what might be expected based on the 2015 experience. We have used unique data collected immediately prior to and after the outbreak of war in Ukraine referring to citizen preferences on a number of EU- and domestic-level refugee policy dimensions. Our complex experimental design allowed us to pin down the similarities and differences between countries, as well as to study stability and change of policy preferences in response to the outbreak of war. In addition we analysed whether differences of expectations on treatment of refugees from different regions of the world structure policy preferences.

A key insight from our study is that citizens’ response to the refugee crisis is not uniform across the three countries we have studied, i.e., Germany, Hungary and Poland. In Germany, where policy was open and accommodating already in 2015, preferences did not change in reaction to the outbreak of war in Ukraine. In Hungary, where the government rejected asylum seekers’ re-allocation in 2015 and the dominant public rhetoric has been that of anti-immigration and anti-refugee sentiments, racialising and emphasising the ‘otherness’ of refugees, respondents after the outbreak of war became somewhat more open to asylum seekers’ having access to the labour market and stopped favouring an increase of EU border control. But in Poland, where the pre-war preferences and government position on asylum were similar to Hungary, but where the largest per-capita influx of refugees was experienced under the liberal conditions of the Temporary Protection Directive in 2022, a considerable change in asylum policy preferences occurred. Poles became significantly more favourable towards asylum seekers’ labour market participation and were not driven in their policy choices by the issue of limits on refugees’ freedom of movement – the two policy dimensions that coincide with the solutions introduced by the Temporary Directive for Ukrainian refugees. However, our analysis of the structure of policy preferences in respect to whether respondents expect preferential treatment of Ukrainians or want all war refugees treated equally show that this change is unlikely to reflect solely favourable attitudes towards Ukrainian refugees, instead suggesting a more liberal approach towards refugees overall (Bansak et al., Citation2023; Moise et al., Citation2024).

These results are consistent with research on the evaluations of the Temporary Protection Directive and show that despite a preference for Ukrainian refugees over other groups (Bansak et al., Citation2023; Moise et al., Citation2024; Pepinsky et al., Citation2022), there has been an overall increase in positive attitudes towards asylum seekers. The results are also consistent with research showing the relevance of the level of EU border protection for support for other policy features (Jeannet et al., Citation2021; Vrânceanu et al., Citation2023). While we are unable to systematically link changes in policy preferences that occurred in Poland to political and media discourse, a comparison of Poland with Hungary suggests that the respective governments’ attitudes towards Russia likely have influenced citizens’ reactions to the war and refugee crisis.

Interestingly, the Ukrainian refugee crisis did not change allocation policy preferences in any of the three countries, as they remain consistently polarised, with German respondents preferring relocation and Hungarian and Polish respondents preferring the status quo, and none being in favour of fiscal solidarity. The lack of change in preferences towards asylum seekers’ allocation mode may seem puzzling, especially in the case of Poland, which under these new circumstances would qualify for relocating refugees from Poland rather than accepting relocated ones from other EU Member States. There may be a number of reasons why this is the case, from the political elite’s anti-EU and anti-immigration discourse to the experience of ad-hoc relocation of Ukrainian refugees without any permanent commitments, to the increasing (among Polish respondents) relevance of EU border protection.

Our research has focused on the short-term reactions to the outbreak of war, and we are unable to link the observed dynamics of refugee policy preferences to exposure to media and political discourse. Nevertheless, the stability of preferences in Germany and the varying degrees of change in Hungary and Poland suggest that a specific combination of political factors with refugee crisis exposure correspond to the dynamics of citizen policy preferences. Equally importantly, our results show that despite the duality of discourse and legislation on refugees in Europe since the outbreak of war, citizens’ preferences on refugee policy are not strongly differentiated along the lines of refugees’ origin, which is highly relevant in relation to previous research showing asymmetrical potential for political mobilisation on the issue of asylum across different groups (Barrera et al., Citation2020; Kustov, Citation2023b; Kustov et al., Citation2021; Lancaster, Citation2022; van der Brug & Harteveld, Citation2021). Finally, our results have direct implications for the development of a common EU asylum policy, as they highlight the scope for consensus rooted in access to the labour market, which is consistently the most important policy dimension over time in all groups in all three countries.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Paweł Kaczmarczyk for his comments, Artem Graban for research assistantship and Daniel Przastek, the Dean of the Faculty of Political Science and International Studies, University of Warsaw, for securing funding for the 2nd wave of the study. We would also like to thank three anonymous Reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at Political Science Seminar, Nuffield College, University of Oxford, University of Groningen Political Economy Colloquium, Opening of Research Network on Ukrainian Migration, UNU-MERIT, United Nations University, Maastricht and IMISCOE Annual Conference 2023, Warsaw.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Replication data and code are available at https://osf.io/7ymxf/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Natalia Letki

Natalia Letki is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Political Science and International Studies and Centre for Excellence in Social Sciences at the University of Warsaw.

Dawid Walentek

Dawid Walentek is senior post-doctoral researcher at Ghent Institute for International and European Studies, Ghent University.

Peter Thisted Dinesen

Peter Thisted Dinesen is Professor of Political Science at University College London and the University of Copenhagen.

Ulf Liebe

Ulf Liebe is Professor of Sociology and Quantitative Methods at the Department of Sociology, University of Warwick.

Notes

2 Council Directive 2001/55/EC – a policy designed for exceptional circumstances already in 2001, yet never employed before 2022.

4 Official statistics show a more balanced composition of arrivals: ‘According to UNHCR data, of the total of 1 015 078 refugees and migrants who arrived in the EU by sea in 2015, 58% were men, 17% women and 25% children (gender not specified). (…) On 1 March 2016, UNHCR figures showed that of the 130 110 arrivals by sea since 1 January 2016, 47% were men, 20% women and 34% children. Demographic profiling by REACH in February 2016 also shows that the majority (65%) of groups traveling on the Western Balkans route were families, whilst men traveling alone represented one fifth (21%) of the total.’ (Shreeves, Citation2016)

6 Hungary lags behind the other two countries, in absolute and relative numbers of Ukrainian refugees received, following an IMF Blog entry (see: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/12/15/europe-could-do-even-more-to-support-ukrainian-refugees).

7 In the first wave, the sample in each of the three countries included a control group and 4 treatment groups; only the control group is used for the country-level comparisons of preferences before and after the outbreak of the war – for details please consult the Pre-Analysis Plan in the Appendix.

9 Please note that the re-contact of participants from the first wave of the survey and collection of a new and representative sample took place at the same time, in April and May 2022.

11 For a detailed analysis of the variation in preferences by subgroups (country, gender, age, education, financial situation, ideology and national vs European identity), please consult (Letki et al., Citation2023)

12 For obvious reasons, respondents could not be asked such a question during the first wave of the survey. However, we did ask a series of questions capturing respondents’ degree of ethnocentrism (for the detailed description of our measure of ethnocentrism, see the Appendix). It is relevant to note that the pre-war level of ethnocentrism is a strong predictor of post-outbreak preferences in respect to special treatment of refugees from Ukraine in the re-contact sample (ß = -.186, p = 0.000, 95% CIs (-.229, -.142)), where higher levels of ethnocentrism in the first wave of the study are linked to a higher likelihood of treating Ukrainian refugees as a special category that deserves preferential treatment in the second wave of our study.

References

- Abdelaaty, L., & Steele, L. G. (2022). Explaining attitudes toward refugees and immigrants in Europe. Political Studies, 70(1), 110–130. doi:10.1177/0032321720950217

- Adida, C. L., Lo, A., & Platas, M. R. (2018). Perspective taking can promote short-term inclusionary behavior toward Syrian refugees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(38), 9521–9526. doi:10.1073/pnas.1804002115

- Adida, C. L., Lo, A., & Platas, M. R. (2019). Americans preferred Syrian refugees who are female, English-speaking, and Christian on the eve of Donald Trump’s election. PLoS One, 14(10), 1–24. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222504

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2016). How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers. Science, 354(6309), 217–222. doi:10.1126/science.aag2147

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2017). Europeans support a proportional allocation of asylum seekers. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(7), 1–6. doi:10.1038/s41562-017-0133

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2023). Europeans’ support for refugees of varying background is stable over time. Nature, 620(7975), 849–854. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06417-6

- Barna, I., & Koltai, J. (2019). Attitude changes towards immigrants in the turbulent years of the ‘migrant crisis’ and anti-immigrant campaign in Hungary. Intersections East European Journal of Society and Politics, 5(1), 48–70.

- Barrera, O., Guriev, S., Henry, E., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2020). Facts, alternative facts, and fact checking in times of post-truth politics. Journal of Public Economics, 182. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.104123

- Baszczak, Ł, Kiełczewska, A., Kukołowicz, P., Wincewicz, A., & Zyzik, R. (2022). How Polish society has been helping refugees from Ukraine. Polish Economic Institute.

- Bechtel, M. M., Scheve, K. F., & van Lieshout, E. (2020). Constant carbon pricing increases support for climate action compared to ramping up costs over time. Nature Climate Change, 10(11), 1004–1009. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-00914-6

- Bíró-Nagy, A. (2022). Orbán’s political jackpot: Migration and the Hungarian electorate. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 405–424. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853905

- Bosse, G. (2022). Values, rights, and changing interests: The EU’s response to the war against Ukraine and the responsibility to protect Europeans. Contemporary Security Policy, 43(3), 531–546. doi:10.1080/13523260.2022.2099713

- Dancygier, R., Egami, N., Jamal, A., & Rischke, R. (2022). Hate crimes and gender imbalances: Fears over mate competition and violence against refugees. American Journal of Political Science, 66(2), 501–515. doi:10.1111/ajps.12595

- De Coninck, D. (2020). Migrant categorizations and European public opinion: Diverging attitudes towards immigrants and refugees. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(9), 1667–1686. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1694406

- Dennison, J., Kustov, A., & Geddes, A. (2023). Public attitudes to immigration in the aftermath of COVID-19: Little change in policy preferences, big drops in issue salience. International Migration Review, 57(2), 557–577. doi:10.1177/01979183221134272

- Durakçay, F. A. (2023). Hungary’s position on the Russia-Ukraine war and its implications for cooperation in the Visegrad group. Eurasian Research Journal, 5(4), 7–26. doi:10.53277/2519-2442-2023.4-01

- Fotopoulos, S., & Kaimaklioti, M. (2016). Media discourse on the refugee crisis: On what have the Greek, German and British Press focused? European View, 15(2), 265–279. doi:10.1007/s12290-016-0407-5

- Freudlsperger, C., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2023). Rebordering Europe in the Ukraine War: Community building without capacity building. West European Politics, 46(5), 843–871. doi:10.1080/01402382.2022.2145542

- Funk, N. (2016). A spectre in Germany: Refugees, a ‘welcome culture’ and an ‘integration politics’. Journal of Global Ethics, 12(3), 289–299. doi:10.1080/17449626.2016.1252785

- Gianfreda, S. (2018). Politicization of the refugee crisis?: A content analysis of parliamentary debates in Italy, the UK, and the EU. Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 48(1), 85–108. doi:10.1017/ipo.2017.20

- Goodman, S. W., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2020). Migration: A step too far for the contemporary global order? Journal of European Public Policy, 27(7), 1103–1113. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1678664

- Górny, A., & Kaczmarczyk, P. (2023). Between Ukraine and Poland. Ukrainian migrants in Poland during the war (Technical report). Center for Migration Studies.

- Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2015). The hidden American immigration consensus: A conjoint analysis of attitudes toward immigrants. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 529–548. doi:10.1111/ajps.12138

- Hangartner, D., Dinas, E., Marbach, M., Matakos, K., & Xefteris, D. (2019). Does exposure to the refugee crisis make natives more hostile? American Political Science Review, 113(2), 442–455. doi:10.1017/S0003055418000813

- Heizmann, B., & Ziller, C. (2020). Who is willing to share the burden? Attitudes towards the allocation of asylum seekers in comparative perspective. Social Forces, 98(3), 1026–1051.

- Hopkins, D. J., Sides, J., & Citrin, J. (2019). The muted consequences of correct information about immigration. The Journal of Politics, 81(1), 315–320. doi:10.1086/699914

- Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (2022). Politicising immigration in times of crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 341–365. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853902

- Jäckle, S., & König, P. D. (2017). The dark side of the German ‘welcome culture’: Investigating the causes behind attacks on refugees in 2015. West European Politics, 40(2), 223–251. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1215614

- Jeannet, A. M., Heidland, T., & Ruhs, M. (2021). What asylum and refugee policies do Europeans want? Evidence from a cross-national conjoint experiment. European Union Politics, 22(3), 353–376. doi:10.1177/14651165211006838

- Kende, A., Hadarics, M., & Szabó, Z. P. (2019). Inglorious glorification and attachment: National and European identities as predictors of anti- and pro-immigrant attitudes. British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(3), 569–590. doi:10.1111/bjso.12280

- Kirkizh, N., Froio, C., & Stier, S. (2022). Issue trade-offs and the politics of representation: Experimental evidence from four European democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 63(4), 1009–1030.

- Klaus, W., & Szulecka, M. (2023). Departing or being deported? Poland’s approach towards humanitarian migrants. Journal of Refugee Studies, 36(3), 467–488. doi:10.1093/jrs/feac063

- Krzyżanowski, M. (2020). Discursive shifts and the normalisation of racism: Imaginaries of immigration, moral panics and the discourse of contemporary right-wing populism. Social Semiotics, 30(4), 503–527. doi:10.1080/10350330.2020.1766199

- Kustov, A. (2023a). Do anti-immigration voters care more? Documenting the issue importance asymmetry of immigration attitudes. British Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 796–805.

- Kustov, A. (2023b). Testing the backlash argument: Voter responses to (pro)immigration reforms. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(6), 1183–1203.

- Kustov, A., Laaker, D., & Reller, C. (2021). The stability of immigration attitudes: Evidence and implications. The Journal of Politics, 83(4), 1478–1494. doi:10.1086/715061

- Kyriazi, A. (2022). Ukrainian refugees in Hungary: Government measures and discourse in the first year of the war. In MIDEM Annual Report.

- Lancaster, C. M. (2022). Value shift: Immigration attitudes and the sociocultural divide. British Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 1–20. doi:10.1017/S0007123420000526

- Laubenthal, B. (2019). Refugees welcome? Reforms of German asylum policies between 2013 and 2017 and Germany’s transformation into an immigration country. German Politics, 28(3), 412–425. doi:10.1080/09644008.2018.1561872

- Leeper, T. J., Hobolt, S. b., & Tilley, J. (2020). Measuring subgroup preferences in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 28(2), 207–221. doi:10.1017/pan.2019.30

- Letki, N., Walentek, D., Dinesen, P. T., & Liebe, U. (2023). Not the mode of allocation but refugees’ right to work drives European citizens’ preferences on refugee policy. West European Politics. online first.

- Liebe, U., & Schwitter, N. (2021). Explaining ethnic violence: On the relevance of geographic, social, economic, and political factors in hate crimes on refugees. European Sociological Review, 37(3), 429–448. doi:10.1093/esr/jcaa055

- Malhotra, N., Margalit, Y., & Mo, C. H. (2013). Economic explanations for opposition to immigration: Distinguishing between prevalence and conditional impact. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 391–410. doi:10.1111/ajps.12012

- McMahon, P. (2023). Poland’s hospitality is helping many Ukrainian refugees thrive. The Conversation, March 2. https://theconversation.com/polands-hospitality-is-helping-many-ukrainian-refugees-thrive-5-takeaways-200406.

- Moise, A. D., Dennison, J., & Kriesi, H. (2024). European attitudes to refugees after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. West European Politics, 47(2), 356–381. doi:10.1080/01402382.2023.2229688

- Nicoli, F., Kuhn, T., & Burgoon, B. (2020). Collective identities, European solidarity: Identification patterns and preferences for European social insurance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(1), 76–95. doi:10.1111/jcms.12977

- Nordø, ÅD, & Ivarsflaten, E. (2022). The scope of exclusionary public response to the European refugee crisis. European Journal of Political Research, 61(2), 420–439. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12464

- Paré, C. (2022). Selective solidarity? Racialized othering in European migration politics. Amsterdam Review of European Affairs, 1(1), 42–61.

- Pepinsky, T., Reiff, Á, & Szabo, K. (2022). The Ukrainian refugee crisis and the politics of public opinion. Evidence from Hungary.

- Pszczólkowska, D. (2022). Poland: What does it take for a public opinion coup to be reversed? International Migration, 60(4), 221–225. doi:10.1111/imig.13041

- Schmidt-Catran, A. W., & Czymara, C. S. (2023). Political elite discourses polarize attitudes toward immigration along ideological lines. A comparative longitudinal analysis of Europe in the twenty-first century. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 49(1), 85–109. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2132222

- Shreeves, R. (2016). Gender aspects of migration and asylum in the EU: An overview. Briefing, EPRS European Parliamentary Research Service.

- Sobolewska, M., Galandini, S., & Lessard-Phillips, L. (2017). The public view of immigrant integration: Multidimensional and consensual. Evidence from survey experiments in the UK and the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(1), 58–79. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2016.1248377

- Stockemer, D., Niemann, A., Unger, D., & Speyer, J. (2020). The “refugee crisis,” immigration attitudes, and euroscepticism. International Migration Review, 54(3), 883–912. doi:10.1177/0197918319879926

- Thérová, L. (2023). Anti-immigration attitudes in contemporary Polish society: A story of double standards? Nationalities Papers, 1(2), 387–402.

- Tilles, D. (2023). Poland condemns EU migration and asylum pact agreed by the European Council. Notes from Poland, June 9. https://notesfrompoland.com/2023/06/09/poland-condemns-eu-migration-and-asylum-pact-agreed-by-european-council/.

- Tondo, L. (2022). Embraced or pushed back: On the Polish border, sadly, not all refugees are welcome. The Guardian, 4.

- Triandafyllidou, A. (2018). A “refugee crisis” unfolding: “Real” events and their interpretation in media and political debates. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16(1-2), 198–216. doi:10.1080/15562948.2017.1309089

- van der Brug, W., & Harteveld, E. (2021). The conditional effects of the refugee crisis on immigration attitudes and nationalism. European Union Politics, 22(2), 227–247. doi:10.1177/1465116520988905

- Van Hootegem, A., Meuleman, B., & Abts, K. (2020). Attitudes toward asylum policy in a divided Europe: Diverging contexts, diverging attitudes? Frontiers in Sociology, 5(35), 1–16.

- Vrânceanu, A., Dinas, E., Heidland, T., & Ruhs, M. (2023). The European refugee crisis and public support for the externalisation of migration management. European Journal of Political Research, 62(4), 1146–1167.

- Ward, D. G. (2019). Public attitudes toward young ImmigrantMen. American Political Science Review, 113(1), 264–269. doi:10.1017/S0003055418000710

- Weiss, J. C. (2013). Authoritarian signaling, mass audiences, and nationalist protest in China. International Organization, 67(1), 1–35. doi:10.1017/S0020818312000380

- Zaun, N. (2022). Fence-sitters no more: Southern and Central Eastern European Member States’ role in the deadlock of the CEAS reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(2), 196–217. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1837918

- Zoltan, A. (2023). Politicizing war: Viktor Orbán’s right-wing authoritarian populist regime and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In G. Ivaldi, & E. Zankina (Eds.), The impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on right-wing populism in Europe (pp. 168–185). European Center for Populism Studies.