?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Grounding on the theories of economic voting and political opposition, this paper investigates whether the Italian Local Labour Markets (LLMs) most affected by the Great Recession reacted in the ballot box voting against the domestic institutions or in favour of anti-European parties. We exploit a recent econometric technique in the counterfactual framework, which adopts a non-parametric generalisation of the difference-in-differences estimator. Our findings show a causal negative impact on the share of Berlusconi’s party, the incumbent party during the crisis, statistically significant in those LLMs with the lowest institutional quality and in the Centre and in the Islands of Italy. We find no causal effect on the anti-European vote whatsoever. People living in the LLMs that suffered the most the effects of the Great Recession used their vote to harm the party in charge, which they deemed responsible for the economic consequences, with a payback effect.

Introduction

Since the 2008 Great Recession, the Italian political landscape has witnessed a gradual but persistent shift towards populist and anti-European parties. A large plethora of studies have highlighted how the 2008 economic shock, together with globalisation and austerity measures, have worsened the pre-existing economic and social disparities in European countries. This situation gave the chance to populist and anti-European parties to gain consensus, supplying a people-centred rhetoric, able to catch the widespread feelings of discontent towards domestic and European institutions (Guriev & Papaioannou, Citation2022).

Nonetheless, when we move to sub-national contexts, the dynamics in play are not always as clear as the national ones (Ejrnæs et al., Citation2023). The recent deindustrialisation processes and the regional changes due to technological advancements and globalisation challenges have altered the regional economies, making it difficult to understand, at a first glance, the patterns of economic and territorial development (Heidenreich & Wunder, Citation2007). Studies have revealed how the regional decline and long periods of economic stagnation have been crucial in triggering feelings of abandonment and frustration, which translated into votes towards populist parties (Los et al., Citation2017). Moreover, austerity measures taken to mitigate the economic shock affected more strongly the countries with high public debt, further widening the public borrowing and debt (Hadjimichalis, Citation2011), like in the case of Italy. Whereas many studies focus on the European context, still little is known on the sub-national dynamics: how the economic, industrial and social structures influence the formation of political preferences and shape their beliefs on the domestic parties or European institutions (MacKinnon et al., Citation2022). The aim of this work is to focus on a specific case study, Italy, and measure the causal effect of the 2008 Great Recession on the political outcomes. Indeed, the Italian case is of particular interest as, over the past two decades, it has been hit by both waves of economic and debt crises, exacerbating in a political crisis, which created a fertile ground for populist and far-right parties, with the rise of the Lega (League), Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement) and Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) (Bobba & McDonnel, Citation2015).

This study is relevant and necessary nowadays, after fifteen years from the shock, for several reasons: (i) so far, most of the studies focused on the European perspective, while little is known of each specific sub-national context and how its economic and social pre-conditions influenced the reactions to the crisis; (ii) as many studies clarified how negative economic outcomes can lead people to more radical political preferences (Hernández & Kriesi, Citation2016; Panunzi et al., Citation2020), it is relevant to study how the crisis politically affected Italian territories to unveil potential consequences of turbulent times, especially nowadays, when we are facing multiple negative events at the same time such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russian-Ukrainian and the Middle-East conflicts and the energy crisis; (iii) Italy is an interesting case, as its North–South divide translates in within-country socio-economic heterogeneity, but also in different levels of institutional quality, which can affect the political outcomes in different ways; (iv) although the Italian case has a unique political scenario, this study and its methodological contribution can serve for comparative analysis with other European countries, which had similar experiences during the economic crisis such as Portugal, Spain and Greece; (v) finally, it can help differentiating between correlation and causation studies.

Our goal is to unveil the political consequences of the 2008 economic crisis, with particular attention to those places that were not able to resist the adverse economic shock. We look at the Italian Local Labour Markets (LLMs) defined on the basis of the proportion of commuters who cross the LLM boundary on their way to work (Italian National Statistics Institute, ISTAT).Footnote1 This unit of analysis is particularly apt to our study because it allows to capture the political votes induced by a change in the job market conditions, limiting a potential spillover effect: it is highly probable that an individual lives in a municipality but works in an another one accessible by commuting. In this case, we are able to take into account the possibility that an individual, for example, loses his job but lives and votes in another municipality.Footnote2 Exploiting a counterfactual framework, we investigate how these places reacted to the Great Recession in the political arena: whether they blamed the domestic party, i.e., non-voting for the incumbent party, and/or the European institution, i.e., voting for anti-European parties. We decide to investigate these two political outcomes, as the Great Recession involved both the national and European institutions, giving us the opportunity to fully understand the political consequences of the crisis.

The crucial step to reach this goal is identifying the LLMs that didn’t resist the shock. To this end, we rely on the literature on regional economic resilience. We use the concept of economic resistance, i.e., the first dimension of the dynamic process of resilience occurring during an adverse shock (Martin et al., Citation2016). Martin et al. (Citation2016) define resilience as a multidimensional concept which entails the exposure to a shock (risk), the reaction to it (resistance), the adaptation to it (reorientation) and the post-shock pathway (recoverability). We use the economic resistance, as the depth of reaction to a shock, which allows us to capture the severity and intensity of the recession in each unit of analysis, without using a simple year-to-year employment growth (Martin, Citation2012; Martin et al., Citation2016).Footnote3

This paper contributes to the literature in different ways. First, we study the local political response to the economic shock, at LLM-level, investigating both national and European sources of discontent. Second, this is one of the rare works analysing the causal impact of an economic shock on political discontent, going beyond the simple relationship between these two phenomena. To this end, we exploit a novel econometric technique expressly developed for time series cross-sectional (TSCS) data to identify and estimate the pure causal effect of interest. Finally, we investigate the heterogeneity of our results, exploring the role of the geographical context and institutional quality in this process, disentangling the total effect.

Our findings show that being less resistant to the crisis does have an impact on the incumbent party that was in charge during the years of the crisis, in those places with lower institutional quality and in the Centre and Islands of Italy up to the 4th election round after the shock, whereas it does not have a statistically significant causal effect on the anti-European vote. Then, people living in the LLMs that suffered the most the effects of the Great Recession reacted with a payback effect against the party in charge during the crisis, deemed responsible for their economic conditions.

The article goes as follows: Section 2 describes the theoretical background of our hypotheses; Section 3 explains the data and the methodology; Section 4 shows the results; Section 5 concludes.

Theoretical background

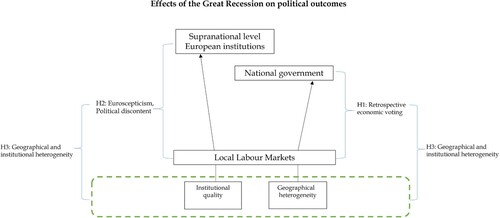

The aim of this work is to understand whether the impact of the 2008 Great Recession resulted in the opposition towards the internal system, i.e., the government in charge, and/or in the opposition towards the European institutions, as responsible for the policy implemented in the country (Mair, Citation2007). There are different literatures that investigate the impact of a negative economic shock on political outcomes. To formulate our hypotheses, we rely on two existing theoretical frameworks: the retrospective economic voting and the political discontent.

Starting from the theories of economic retrospective voting, the assumption is that rational voters support the incumbent parties when they perceive a positive national economy, while they punish the incumbent, voting for alternative parties, when they perceive they live in a bad national economic situation (Duch & Stevenson, Citation2008). Following Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (Citation2000), the existing economic conditions affect the electoral results, determining the future of the party in charge. Many studies show how the Great Recession resulted in protest votes against the incumbent, especially in Western countries and in those hit by fiscal problems (Bartels, Citation2014; Hernández & Kriesi, Citation2016; Kriesi, Citation2014). Bojar et al. (Citation2022), in a study on 15 European countries, find that the austerity measures implemented during the Great Recession had a major negative impact on the government popularity, as a sign of electoral punishment for the economic consequences of the crisis. To avoid this electoral punishment, the strategy of the incumbent governments is usually to avoid restrictive fiscal policies when approaching the elections (Hübscher & Sattler, Citation2017). However, in the case of the Great Recession, austerity measures couldn’t be avoided for too long, and it is possible that their implementation had a negative impact on the incumbents’ electoral results (Armingeon & Giger, Citation2008). As shown in a study by Hübscher et al. (Citation2018), when the government proposes austerity measures, their chances to be re-elected drop. In our study, focused on Italy, we therefore expect that the economic shock had a negative impact on the share of votes of the party that was in government in the wake of the Great Recession, as it might be considered responsible for the management of the crisis and for agreeing on the austerity measures taken at that time. In this regard, despite many studies on economic retrospective voting consider voters as myopic, looking only at the party’s performance close to the election (Healy & Lenz, Citation2014; Huber et al., Citation2012), several studies demonstrate the existence of a long-term effect. Stiers et al. (Citation2020), for example, find that voters in the Netherlands are assessing the government performance across a long-time period, using online information. Similarly, Cerqua et al. (Citation2021) find a positive effect in the municipalities affected by L’Aquila earthquake that persists even after ten years from the shock. Following the above considerations, our first intent is to test the potential negative effect of the Great Recession on the incumbent party’s popularity, over time.

Our first hypothesis is:

H1 – The LLMs most affected by the Great Recession blamed the incumbent party, that was in charge during the crisis, causing a decrease in its voting share in the following elections.

Negative economic outcomes and lack of trust towards the domestic institutions can indeed turn in favour of Eurosceptic parties, when people perceive that economic policies have been decided at supranational level, i.e., by European institutions (Nicoli, Citation2017). The manifestation of Euroscepticism can take two different forms: hard Euroscepticism, when the opposition is against the whole process of European integration; soft Euroscepticism, where the opposition is against a particular set of policies (Harmsen & Spiering, Citation2004; Szczerbiak & Taggart, Citation2002). Since during the crisis, national fiscal policies and austerity measures were highly influenced by European institutions, it’s likely that people, once lost the trust in their government, turned blaming and opposing the European institutions, voting for anti-European parties (Castelli Gattinara & Froio, Citation2014). Therefore, our attention is on the electoral results of parties belonging to the hard Euroscepticism, as capturing the effective political response and opposition towards the European institutions. Most of these studies, however, focus on European regions or countries and, using linear models, they are not able to capture the potential heterogeneity of the relationships within the different national contexts and, most importantly, they are not able to establish a causal connection. Therefore, considering the relevance of the European institutions at the time of the crisis and their pressure on implementing austerity measures, we explore the existence of a causal relationship between the 2008 economic shock and the rise of the anti-European vote over time, testing a second hypothesis:

H2– The LLMs most affected by the Great Recession blamed the European institutions causing an increase in the anti-European vote in the following elections.

H3 – The causal effects of the Great Recession on the votes for the incumbent party and anti-European parties show heterogeneity with respect to the geographical areas and institutional quality.

In the following Section 3, we present the data and the methodology used to test our hypotheses.

Data and methodology

Our unit of analysis is the LLM. LLMs are sub-regional geographical areas where the bulk of the labour force lives and works, and where establishments can find the largest amount of the labour force necessary to occupy the offered jobs. LLMs are defined on a functional basis, the key criterion being the proportion of commuters who cross the LLM boundary on their way to work. In Italy, in 2020, we have a total of 610 LLMs. In this framework, we use LLMs as the unit of interest to analyse the electoral outcomes registered during the economic crisis. Because our treatment is measured through the employment rate, it is fundamental to take into account the possibility that an individual lives in a municipality but works in another one. In this sense, LLM is the perfect definition for our measure, as a municipality-level or a NUTS3-level analysis would not capture these dynamics.

Our data have a panel structure, where for each LLM we have seven non-consecutive time-periods, that correspond to the election rounds of the national (Chamber of Deputies) and European elections. We include both national and European elections as they are more likely to represent the feelings of frustration or discontent of individuals. Because European elections are considered second-order elections, many scholars argued that they might also be used by voters to channel their discontent (Hobolt & De Vries, Citation2016). The following summarises the corresponding election for each period.Footnote4

Table 1. Election rounds.

The first main dependent variable is the Berlusconi’s party share of votes, as it was the incumbent party at the time of the crisis. It corresponds to the share of votes gained at each election by the party led by Silvio Berlusconi, namely Forza Italia (Come on Italy) and Il Popolo della Libertà (the People of Freedom).Footnote5 The second main dependent variable is the anti-European vote. It captures the hard Euroscepticism stream, defined following Nicoli (Citation2017), as the share of parties that have an orientation opposed to the European integration, namely that registered a value of the eu_position variable in the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES)Footnote6 lower than 3 (opposed, strongly opposed).Footnote7 For each election round that we consider, we use the definition in the closest CHES, to have a time-varying outcome variable and capture the evolution of the party orientation over time.Footnote8

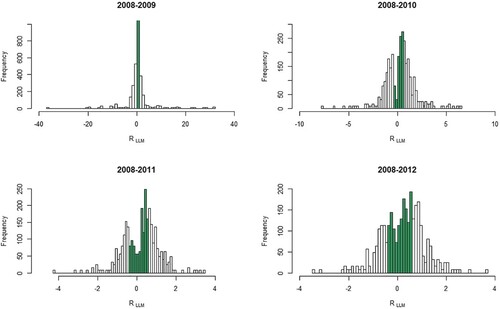

To build our treatment variable, we first define the economic resistance of each LLM (see Martin et al., Citation2016 and Lagravinese, Citation2015). We measure the economic resistance on the capacity of the LLM to react to the shock, using the employment rate (Faggian et al., Citation2018), which allows to capture their welfare and labour market conditions, especially considering the major job loss affecting Italy during the Great Recession. We choose the employment rate as the Italian local labour system is characterised by small and medium-sized enterprises and specifically in manufacturing, which in times of crisis is one of the first sectors to suffer and be affected (Barzotto et al., Citation2019).

Differently from the main literature, we calculate the LLM economic resistance () with respect to their specific geographical area (North-East, North-West, Centre, South, Islands), as studies have recognised that regional business cycles are not always in line with the national one (Mastromarco & Woitek, Citation2007; Owyang et al., Citation2009). In this way, we control for the potential heterogeneity in the national reaction, comparing LLMs’ resistance with their respective geographical area.

Formally,

(1)

(1) where

is the variation in the employment rate of the LLM and the

is the variation in the employment rate of the geographical area. This index is centred around 0.

Because we are considering a common crisis for the national territory, to identify a proper shock and to dichotomise the treatment variable, we calculate the ΔEt,t + k with t = 2008 and k = 1, … ,4 and we consider as treated units only LLMs having <0, i.e., LLMs which never recover in each year between 2008-2012. In addition, we also do not consider observations with

around zero (the threshold in the main analysis is set to

5 per cent) to compare LLMs hit by the crisis at different intensities.Footnote9 We also exclude from the analysis those LLMs that were affected by an earthquakeFootnote10 that registered a magnitude greater than 5 in the Modified Mercalli Intensity scale in the period under analysis, as it can be considered as a second shock that cannot be disentangled from the economic crisis.

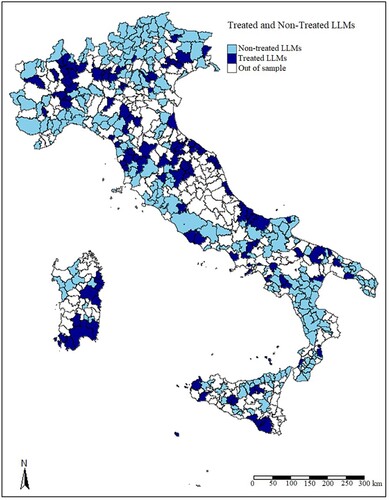

We end up with 121 treated LLMs and 223 non-treated LLMs. In this way, we are comparing those LLMs more affected by the economic crisis, that never recovered in the period under analysis (LLMs less resistant), with those LLMs which were more resistant with respect to their geographic area. The following depicts the geographical distribution of treated and not-treated units.

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of treated and not-treated LLMs.

Notes: the blue areas are the treated LLMs, defined as LLMs which never recover in the years between 2008 and 2012. The light-blue areas are non-treated LLMs defined as LLMs less affected by the crisis. The white areas are LLMs out of sample, because they are units with greater or less than 5% and/or units affected by an earthquake with a magnitude greater than 5 in the Modified Mercalli Intensity scale.

For each election round, we also collect control variables at the LLM-level, on the main economic and demographic characteristics. We have considered different sources of data: the Italian National Statistics Institute (ISTAT) dataset for all the demographic variables, the Statistical Register of Active Enterprises archive (ASIA) dataset for the total number of employees and for the employees in the manufacturing sector. As a measure of the Institutional Quality Index (IQI) we refer to Nifo and Vecchione (Citation2014), who build an indicator based on five pillars: voice and accountability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control and corruption. presents summary statistics for all the variables used as control covariates, and it shows how the mean of the pre-treatment covariates between treated and non-treated units is always statistically significant. Indeed, the key econometric challenge in analysing the effects of the economic shock is that LLMs more affected by this shock may systematically differ from unaffected LLMs.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

To identify proper counterfactuals for the affected LLMs, we use a recent evaluation technique proposed by Imai et al. (Citation2023), which consists of a non-parametric generalisation of the difference-in-differences (DiD) estimator developed for TSCS data.

In the proposed approach, we first select for each treated LLM a set of control LLMs, that resisted the economic shock and belong to the same geographical area (North-East, North-West, Centre, South or Islands). We refine this matched set, , by using the Mahalanobis distance matching, which assigns a positive weight to the set of 5 control units within

more similar to the treated unit in terms of pre-treatment trends of the outcome and control covariates. We use as pre-treatment covariates the lagged values of the total number of employees, the number of employees in the manufacturing sector, the real income per capita, the workforce rate, the population density, the share of elderly people, the share of foreigners, the electoral turnout, the degree of urbanisation, the share of the anti-European vote, the populist vote and the share of votes to Berlusconi’s party. For each treated LLM, we estimate the counterfactual outcome using the weighted average of the control units in the refined matched set. Finally, we compute the DiD estimate of the average treatment effect for the treated (ATT) for each treated observation and then average it across all treated observations, adjusting for possible time trends.

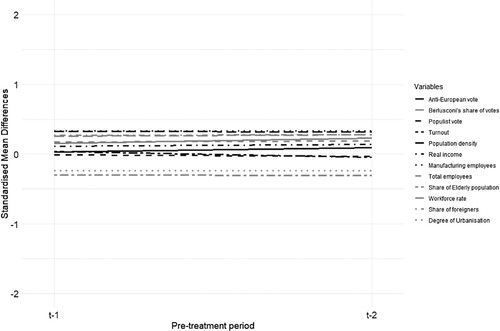

This method is based on three assumptions: absence of the carryover effect (Assumption 1), absence of an interference effect (Assumption 2) and parallel trend after conditioning on the treatment, outcome, and covariate histories (Assumption 3). The methodology and the assumptions are explained in more details in Section A1 of the Appendix.

This set of assumptions is arguably milder than those used by the most common methodologies adopted to analyse TSCS data, such as the linear regression models with fixed effects, dynamic panel models, matching methods, and the DiD estimator (Imai et al., Citation2023). In Section A2 of the Appendix, we verify that Assumption 3 is met to guarantee the robustness of the empirical analysis and we show the results of the covariate balancing plot in Figure A1 of the Appendix.

Results

We start testing H1, i.e., whether the less resistant LLMs manifested their disappointment towards the domestic institutions. In , we assess the impact of being more hit by the crisis on the share of Berlusconi’s party (Forza Italia/Il popolo della Libertà). Berlusconi’s party was the one in charge during the first years of the Great Recession. Il popolo della Libertà took office in 2008 and was in charge until 2011 when austerity measures had to be taken and Berlusconi resigned leaving the floor to a technical government led by Mario Monti. These facts might have caused disappointment in people that always supported his party, especially because it didn’t succeed in keeping the promise of avoiding the collapse of the Italian economy. Therefore, we want to test whether there has been a vote against Berlusconi’s party over the years after the crisis. In Panel A of , we depict the results of the main analysis, which show a negative relationship over time between the economic crisis and the vote for Berlusconi’s party, but without a significant causal effect. However, when we move to differentiate the effects, some heterogeneity exists. In Panel B, we show the heterogeneity in the causal effect in terms of institutional quality, measured through the IQI developed by Nifo and Vecchione (Citation2014).Footnote11 The LLMs in the first tertile of the institutional qualityFootnote12 reacted towards Berlusconi’s party, with a negative and significant effect at 10 per cent in the 2019 electoral round. This result is in line with the general findings of the literature on institutional quality (Agerberg, Citation2017; Ferrante & Pontarollo, Citation2022), and shows that it plays a role in shaping political preferences. This result also supports the idea that voters are not myopic but rather keep blaming the incumbent party over time. This could be explained also by the fact that Italian LLMs are not very flexible to shocks above all in the least developed LLMs (Celli et al., Citation2023), implying a slow reaction in the economic system and then in the voting choices. From a geographical point of view, Panel C shows the geographical heterogeneity. Whereas a non-significant but still negative effect is estimated for all the areas, a significant effect at 10 per cent level arises in the Centre in the first European and National rounds after the Great Recession and a negative significant effect at 5 per cent level for the Islands in the European 2019 round election. Moreover, the coefficients in the 2019 elections (both in Panel B and Panel C) are much greater than the other years, meaning that even seven years after Berlusconi’s resignation people living in the most hit areas still voted against his actions. Therefore, Panel B and C find that H3 is in part confirmed, and the geographical and institutional heterogeneity of the effects exists, even if it emerges weakly. The fact that we find evidence in European elections do not necessarily mean that our results are weaker than the evidence we find in the national election: indeed, following Fiorina (Citation1981) and Hobolt and Tilley (Citation2014), given the central role played by the European institutions during the crisis, European elections can be used to punish directly for the effect of the crisis, meaning for example to vote against a national party that played a role in the European policies.

Table 3. Impact of the great recession on Berlusconi’s share of votes.

These results are also supported by the news reported by the national newspapers during that period. During the three years of government between 2008 and 2011, Berlusconi had to deal with the consequences of the economic and financial crisis, to restore the Italian economy. Since the beginning, he adopted an optimistic vision and attitude, giving hope and promises to people that the whole system of banks and enterprises was solid and wouldn’t have suffered.Footnote13 However, his choices on the political economy didn’t succeed, worsening the Italian debt crisis and economy, which at the end of 2011 reached a spread of 574 points and put Italy at risk of bailing out. The pressure coming from Europe and the failure of obtaining the majority in the Chambers pushed Berlusconi to resign and leave the floor to a technical government led by Mario Monti.Footnote14 In the meanwhile, the continuing scandals, and legal investigations he was involved in, harmed his reputation and integrity, disappointing a large part of the electorate.Footnote15

Days before his resignation, people gathered in the main squares of the cities to protest against Berlusconi and ask for his resignation. They expressed their disappointment with banners showing ‘Stop now’, ‘Shameful Berlusconi’, ‘Go Home’ and similar ones to ask for his resignation.Footnote16 The same day of his resignation, groups of people gathered in the streets to celebrate the end of his government, hanging the Italian flag outside the houses and protesting against his behaviour.Footnote17 What we find, therefore, could be the result of disappointment due to several unmet promises coming from those places that suffered the most during the crisis and felt betrayed by the government. Worth mentioning, however, is that we do not find any significant effect in the Northern part of Italy, highlighting, once again, the remarkable differences between the North and the (Centre) South of Italy. Although this result may be further and deeper investigated in the future, we speculate on one potential explanation. One reason might be related to the industrial and entrepreneurial presence in the North and the support towards Berlusconi´s party. Indeed, Berlusconi was a well-known entrepreneur, with a prominent business career, who contributed to the financial and economic development of the Northern area, especially in the City of Milan. Therefore, it might be that the trust in him and in his party might have reduced the blame towards him for the consequences of the crisis.

Moving to H2, shows the results of the causal impact of the economic crisis in the less resistant LLMs on the vote for anti-European parties. Both in the main (Panel A) and in the heterogeneity analysis (Panel B and C), we don’t find any statistically significant results. Both H2 and H3, in this case, are rejected. These results show that once we turn to a non-parametric counterfactual approach, we do not find any statistically significant causal effect of being more affected by the Great Recession and reacting by voting for anti-European parties. Although the economic crisis has created a fertile ground for the ascent of populist and Eurosceptic parties like Movimento Cinque Stelle, Lega or Fratelli d’Italia, citizens living in places more hit by unemployment and with lower institutional quality didn’t use the Eurosceptic stance of these parties oppose the European institutions. Our analysis demonstrates, instead, that they rather opposed the domestic institutions as responsible for the negative consequences of the crisis, with a payback effect. We test the sensitivity of our main results to a set of robustness checks and summarise the results of interest in Section A3 of the Appendix.

Table 4. Impact of the great recession on the Anti-European vote.

Conclusions

Academic studies exploring the dynamics underneath the formation of political preferences need to readdress the attention towards local contexts. As many studies have highlighted the relevance of geographic inequalities in shaping people’s political attitudes, there is the urgency to shed light on the different sources and channels of political discontent arising in subnational contexts. Our study highlights how the Great Recession has exacerbated pre-existing territorial and institutional inequalities, worsening the economic conditions of many places in Italy, which in turn influenced and re-addressed citizens’ political preferences, with a reaction against the incumbent party. In contrast with most relevant studies at European level, which find positive correlation between negative economic conditions and support towards anti-European parties, when we look at the causal impact in the local context, this relationship does not hold, underlying the fact that there is a different dynamic underneath the formation of political preferences.

Despite the influence of European institutions being very present during the Great Recession, people kept their attention on the national environment and the behaviour of domestic institutions. We find a payback effect against Berlusconi’s party, which tells that voters are abiding, and even after many years from the crisis, they still shape their political beliefs on previous events, showing their disapproval in the ballot box. The North–South divide and the institutional heterogeneity coming out from our results, even if weakly, are a potential manifest of the need to address investments aimed at reinforcing the political trust and the democratic system in the most suffering local contexts. When the government is not able to cope with the consequences of a negative shock, such as the 2008 crisis, the ballot box becomes the only tool for people to express their disappointment against the incumbent parties, triggering a payback effect. This study, however, represents only part of the picture. Further research could address the potential role this payback effect has played in the following populist shift that occurred in the Italian elections in 2013, 2018 and 2022. Similar approaches could also be used in the future to test whether the management of Covid-19 affected the reactions against the incumbent in the following elections, focusing on the geographical and institutional heterogeneity, which might completely change the overall picture.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Editors Jeremy Richardson and Berthold Rittberger and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments. We are grateful to Augusto Cerqua for his suggestions on earlier versions of this work. We thank the participants to the 2023 AISRe Conference and the ‘Regional Inequality and Political Discontent in Europe’ workshop (Copenhagen Business School). Finally, we are grateful to Mads Dagnis Jensen, Anders Ejrnæs, Dominik Schraff and Sofia Vasilopoulou for inviting us to the special issue and for their great feedback and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Viviana Celli

Viviana Celli is currently a research fellow at the University Ca’ Foscari of Venice in collaboration with ISTAT. While writing this article, she was a research fellow in Economic Statistics at Sapienza University of Rome, Department of Social Sciences and Economics. Her research interests range from regional and labour policy evaluation to econometrics, economic and social sciences issues.

Chiara Ferrante

Chiara Ferrante is currently a Research Associate at the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI. While writing this article, she was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Spatial Dynamics Lab of the University College Dublin. Her research interests and expertise range from studies on political discontent and political geography to studies on innovation economics, smart specialisation policies and technology transfer.

Notes

1 The criteria used to determine Italian LLMs are similar to those used to define Metropolitan Statistical Areas in the United States or Travel to Work Areas in the United Kingdom.

2 The commuting phenomena is not captured by municipal nor NUTS-3 boundaries.

3 In the Data and Methodology section we provide more details on how resistance is computed.

4 We do not consider the 2009 European election as it falls within our treatment period.

5 Though the People of Freedom was in charge in 2008 as part of a coalition, we only take the share of votes belonging to Berlusconi’s party (People of Freedom), and not the entire coalition, as it was the main party and Berlusconi was the leader of the coalition and Prime Minister.

6 The CHES is a project on European politics led by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Centre for European Studies.

7 See Table A1 in the Appendix for details on the parties belonging to this category and their respective eu_position score.

8 2006 CHES for 2004 and 2006 elections; the 2010 CHES for 2008 and 2009 elections; the 2014 CHES for 2013 and 2014 elections; and the 2019 CHES for the 2018 and 2019 elections.

9 See Figure A2 in the Appendix for more details.

10 We exclude the LLMs affected by the 2009 earthquake in L’Aquila, the 2012 earthquake in Emilia and the 2016–2017 earthquakes in Central Italy.

11 We divided the IQI in tertiles defined based on the treated LLMs.

12 In the first tertile of IQI there are LLMs belonging to Regions of Centre, South and Islands.

13 See Il Sole 24 Ore (2008): https://st.ilsole24ore.com/art/SoleOnLine4/Italia/2008/12/berlusconi-crisi-mercati.shtml?uuid=e06e07e0-cd44-11dd-8f0b-bdce7f887965&DocRulesView=Libero

14 See la Repubblica (2014): https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2014/02/10/news/estate_2011_spread_berlusconi_bce_monti_governo_napolitano-78215026/

15 See Il Sole 24 Ore (2013): https://st.ilsole24ore.com/art/notizie/2013-09-30/governo-berlusconi-novembre-2011-194616.shtml?uuid=AbIeLogI&refresh_ce=1

References

- Agerberg, M. (2017). Failed expectations: Quality of government and support for populist parties in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 56(3), 578–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12203

- Alabrese, E., Becker, S. O., Fetzer, T., & Novy, D. (2019). Who voted for Brexit? Individual and regional data combined. European Journal of Political Economy, 56, 132–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.08.002

- Algan, Y., Guriev, S., Papaioannou, E., & Passari, E. (2017). The European trust crisis and the rise of populism. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2017(2), 309–400. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2017.0015

- Anderson, C. (1998). When in doubt, use proxies. Comparative Political Studies, 31(5), 569–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414098031005002

- Armingeon, K., & Giger, N. (2008). Conditional punishment: A comparative analysis of the electoral consequences of welfare state retrenchment in OECD nations, 1980–2003. West European Politics, 31(3), 558–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380801939834

- Bartels, L. M. (2014). Ideology and retrospection in electoral responses to the great recession. In N. Bermeo & L. Bartels (Eds.), Mass politics in tough times: Opinions, votes and protest in the great recession (pp. 185–223). Oxford University Press.

- Barzotto, M., Corò, G., Mariotti, I., & Mutinelli, M. (2019). Ownership and workforce composition: A counterfactual analysis of foreign multinationals and Italian uni-national firms. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, 46(4), 581–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-019-00114-0

- Bobba, G., & McDonnel, D. (2015). Italy – a strong and enduring market for populism. In H. Kriesi & T. S. Pappas (Eds.), Chapter 10 In European populism in the shadow of the great recession (pp. 163–179). ECPR Press.

- Bojar, A., Bremer, B., Kriesi, H., & Wang, C. (2022). The effect of austerity packages on government popularity during the great recession. British Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000472

- Bouvet, F., & Dall’erba, S. (2010). European Regional Structural Funds: How large is the influence of politics on the allocation process? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(3), 501–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02062.x

- Castelli Gattinara, P., & Froio, C. (2014). Opposition in the EU and opposition to the EU: Soft and hard euroscepticism in Italy in the time of austerity. In Institute of European democrats (Ed.), Rising populism and the European elections (pp. 178). IED.

- Celli, V., Cerqua, A., & Pellegrini, G. (2023). The long-term effects of mass layoffs: Do local economies (ever) recover? Journal of Economic Geography, 23(5), 1121–1144. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbad012

- Cerqua, A., Ferrante, C., & Letta, M. (2021). Electoral earthquake: Natural disasters and the geography of discontent (No. 790). GLO Discussion Paper.

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018). Global competition and brexit. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000685

- De Dominicis, L., Dijkstra, L., & Pontarollo, N. (2022). Why are cities less opposed to European integration than rural areas? Factors affecting the Eurosceptic vote by degree of urbanization. Cities, 130, 103937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103937

- De Vries, C. E., & Giger, N. (2014). Holding governments accountable? Individual heterogeneity in performance voting. European Journal of Political Research, 53(2), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12033

- Duch, R. M., & Stevenson, R. T. (2008). The economic vote: How political and economic institutions condition election results. Cambridge University Press.

- Ecker, A., Glinitzer, K., & Meyer, T. M. (2016). Corruption, performance voting and the electoral context. European Political Science Review, 8(3), 333–354. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773915000053

- Ejrnæs, A., Jensen, M. D., Schraff, D., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2023). Regional inequality and political discontent in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy.

- Ezcurra, R., & Rios, V. (2019). Quality of government and regional resilience in the European union. Evidence from the great recession. Papers in Regional Science, 98(3), 1267–1291. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12417

- Faggian, A., Gemmiti, R., Jaquet, T., & Santini, I. (2018). Regional economic resilience: The experience of the Italian local labor systems. The Annals of Regional Science, 60(2), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-017-0822-9

- Ferrante, C., & Pontarollo, N. (2022). The populist outbreak and the role of institutional quality in European regions. Scienze Regionali, 22(3), 337–366.

- Fingleton, B., Garretsen, H., & Martin, R. (2015). Shocking aspects of monetary union: The vulnerability of regions in Euroland. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(5), 907–934. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu055

- Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective voting in American national elections. Yale University Press.

- Giunta, A., Nifo, A., & Scalera, D. (2012). Subcontracting in Italian industry: Labour division, firm growth and the north–south divide. Regional Studies, 46(8), 1067–1083. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.552492

- Guiso, L., Herrera, H., Morelli, M., & Sonno, T. (2019). Global crises and populism: The role of Eurozone institutions*. Economic Policy, 34(97), 95–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiy018

- Guriev, S., & Papaioannou, E. (2022). The political economy of populism. Journal of Economic Literature, 60(3), 753–832. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20201595

- Hadjimichalis, C. (2011). Uneven geographical development and socio-spatial justice and solidarity: European regions after the 2009 financial crisis. European Urban and Regional Studies, 18(3), 254–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411404873

- Harmsen, R., & Spiering, M., Eds. (2004). Euroscepticism: Party politics, national identities and European integration. Editions Rodopi).

- Healy, A., & Lenz, G. S. (2014). Substituting the End for the whole: Why voters respond primarily to the election-year economy. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12053

- Heidenreich, M., & Wunder, C. (2007). Patterns of regional inequality in the enlarged Europe. European Sociological Review, 24(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm031

- Hellwig, T., & Samuels, D. (2007). Voting in open economies: The electoral consequences of globalization. Comparative Political Studies, 40(3), 283–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006288974

- Hernández, E., & Kriesi, H. (2016). The electoral consequences of the financial and economic crisis in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 55(2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12122

- Hirano, K., Imbens, G., & Ridder, G. (2003). Efficient estimation of average treatment effects using the estimated propensity score. Econometrica, 71(5), 1307–1338. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00451

- Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

- Hobolt, S. B., & De Vries, C. (2016). Turning against the Union? The impact of the crisis on the Eurosceptic vote in the 2014 European Parliament elections. Electoral Studies, 44, 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.05.006

- Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2014). Blaming Europe?: Responsibility without accountability in the European union. Oxford University Press.

- Huber, G. A., Hill, S. J., & Lenz, G. (2012). Sources of bias in retrospective decision making: Experimental evidence on voters’ limitations in controlling incumbents. American Political Science Review, 106(4), 720–741. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000391

- Hübscher, E., & Sattler, T. (2017). Fiscal consolidation under electoral risk. European Journal of Political Research, 56(1), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12171

- Hübscher, E., Sattler, T., & Wagner, M. (2018). Voter responses to fiscal austerity. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the European political science association, Vienna, 21–23 June.

- Imai, K., Kim, I. S., & Wang, E. (2023). Matching methods for causal inference with time-series cross-sectional data. American Journal of Political Science, 67(3), 587–605.

- Jensen, N. M., & Rosas, G. (2020). Open for politics? Globalization, economic growth, and responsibility attribution. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 7(2), 89–100.

- Kriesi, H. (2014). The political consequences of the economic crisis in Europe: Electoral punishment and popular protest. In N. Bermeo & L. Bartels (Eds.), Mass politics in tough times: Opinions, votes and protest in the Great Recession (pp. 297–333). Oxford University Press.

- Lagravinese, R. (2015). Economic crisis and rising gaps North-South: Evidence from the Italian regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsv006

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2000). Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 183–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.183

- Los, B., McCann, P., Springford, J., & Thissen, M. (2017). The mismatch between local voting and the local economic consequences of Brexit. Regional Studies, 51(5), 786–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1287350

- MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., O’Brien, P., Ormerod, E., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2022). Reframing urban and regional ‘development’ for ‘left behind’ places. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab034

- Mair, P. (2007). Political opposition and the European union. Government and Opposition, 42(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2007.00209.x

- Martin, R. (2012). Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbr019

- Martin, R., Sunley, P., Gardiner, B., & Tyler, P. (2016). How regions react to recessions: Resilience and the role of economic structure. Regional Studies, 50(4), 561–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1136410

- Mastromarco, C., & Woitek, U. (2007). Regional business cycles in Italy. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 52(2), 907–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2007.04.013

- Nicoli, F. (2017). Hard-line euroscepticism and the eurocrisis: Evidence from a panel study of 108 elections across Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(2), 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12463

- Nifo, A., & Vecchione, G. (2014). Do institutions play a role in skilled migration? The case of Italy. Regional Studies, 48(10), 1628–1649. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.835799

- Owyang, M. T., Rapach, D. E., & Wall, H. J. (2009). States and the business cycle. Journal of Urban Economics, 65(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.11.001

- Panunzi, F., Pavoniz, N., & Tabellini, G. (2020). Economic shocks and populism: The political implications of reference-dependent preferences. CESifo Working Paper, 8539.

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

- Stiers, D., Dassonneville, R., & Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2020). The abiding voter: The lengthy horizon of retrospective evaluations. European Journal of Political Research, 59(3), 646–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12360

- Szczerbiak, A., & Taggart, V. (2002). The party politics of euroscepticism in EU member and candidate states. Sussex European Institute, Working Paper, 51.

Appendix

Table A1. Eurosceptic parties.

A1. Methodology and assumptions

An important step in this procedure is the choice of a non-negative integer F as the number of leads, which represents the outcome of interest measured at F time-periods after the shock, where F = 0 represents the contemporaneous effect. We selected F = 4 implying the treatment effect on the outcome 4 years after the treatment is administered. We select another non-negative integer L as the number of lags to adjust for. The choice must take into account the bias-variance trade-off: while a greater value improves the credibility of the unconfoundedness assumption, it also reduces the efficiency of the resulting estimates by reducing the number of potential matches. We chose L = 2. In this case, each t represents a particular election round.

Formally, we define the average treatment effects among treated (ATT) as:

where the treated LLMs are those which experienced the shock, i.e.,

and

. In this definition

is the potential outcome under a treatment change, whereas

represents the potential outcome without the shock, i.e.,

and

. In both cases, the rest of the treatment history, i.e.,

, is set to the realised history. In our case, δ(4, 2) represents the average causal effect of the economic crisis on the outcome, four election periods after the treatment, while assuming that the potential outcome depends on the treatment history up to two election periods earlier.

We then compute the DiD estimate of the ATT for each treated observation and then average it across all treated observation. Formally:

Assumption 1. Absence of the carryover effect.

It implies that the potential outcome for unit i at time t+F does not depend on the previous treatment status of the same unit after L time periods, i.e., . This implies that we allow for the possibility that past treatments affect future outcomes up to L years.

Assumption 2. Absence of an interference effect.

The potential outcome for unit at time

does not depend on the treatment status of other units, for example,

with

and for any

.

Assumption 3. Parallel trend assumption after conditioning on the treatment, outcome, and covariate histories.

where

is a vector of observed time-varying confounders for unit i at year t. Therefore, the conditioning set includes the treatment history, the lagged outcomes (except the immediate lag

), and the covariate history. Choosing a relatively large value of L (in our case L = 2) increases the credibility of a limited carryover effect and the parallel trend assumptions, while using data at the LLM level allows meeting the no-interference assumption.

A2. Covariate balancing

It is important to verify if Assumption 3 is met in order to guarantee the robustness of the empirical analysis. To this end, the non-parametric generalisation of the DiD estimator allows to examine the covariate balancing between treated and matched control observations. This enables the investigation of whether the treated and matched control observations are comparable with respect to observed confounders (Imai et al., Citation2023). The covariate balance plot is reported in Figure A1. The solid lines represent the balance of the two main lagged outcomes, the populist vote and the anti-European vote respectively, whereas the other lines show the balance of the other covariates. It clearly emerges that the level of imbalance remains stable across the 2 pre-treatment years and fully within the (1, 1) range of the standard deviation. It is important to notice that we use the same control variables for all empirical analyses, meaning that the covariate balance plot presented in Figure A1 is the same for all the main analyses presented below. As the level of imbalance for the lagged values of our variables stays relatively constant over the entire pre-treatment period, this demonstrates that the parallel trend assumption is satisfied and that we met the condition of balancing after the matching.

A3. Robustness checks

We test the sensitivity of our results to a set of robustness checks and summarise the results of interest in Table A1. First, we check the sensitivity of our estimates to the choice of the number of neighbours used as counterfactual units, using 3 and 7 neighbours, respectively. We also test the sensitivity of the main analysis using different matching and weighting methods to refine the matched set of control units. In the first case, we use the inverse propensity score weighting (IPW) method (Hirano et al., Citation2003), while in the second case, we use propensity score matching (PSM) (Rosenbaum et al. Citation1983). All these estimates are in line with those reported in the main analysis.

Table A2. Robustness checks for anti-European vote and Berlusconi’s share of votes.

In , we test the existence of a potential effect on other outcome variables. First, we test the effect on the share of vote of Lega (League), as it was part of the centre-right coalition at the time of the crisis (Lega Nord, at that time), together with Popolo della Libertà (Berlusconi’s party); and on the share of the incumbent party in charge at each election. We find no significant effects whatsoever, confirming the consistency of our results. Furthermore, we test our results also with respect to the party of Mario Monti ‘Scelta Civica’, who was created in 2013, after he led the technical government. Indeed, the austerity measures were implemented by Mario Monti in 2011, after Silvio Berlusconi resigned, having lost the absolute majority. Since Monti government was a technical government there were no elections. Thus, we test for the impact of the crisis on the votes for Monti’s party ‘Scelta Civica’ in the 2013 and 2014 elections and on the votes for the ‘Democratic Party’. Both resulted in no effect whatsoever. shows that there are no significant effects for all the alternative outcome variables tested.

Table A3. Robustness checks for other political outcomes.

Because the selection of the cut-off for the selection of the treated LLMs is an arbitrary choice, we test the sensitivity of our results, changing these values. In particular, we delete from the analysis LLMs with an in the range of

3% in the first case and

7% in the second attempt. As shown in , the results are in line with the main analysis for both outcome variables.

Table A4. Robustness checks with respect to the cut-off choice.

In order to verify the sensitivity of our results to alternative model specifications, we also run a robustness check using the standard DiD estimator. It is worth to note that, from the statistical point of view, this approach is less consistent with respect to our model choice. In , we show the results, which are coherent with our analysis. However, with this approach there is no matching between treated and non-treated units and therefore some coefficients in the Anti-European vote are significant, but this is most likely due to overestimation.

Table A5. Robustness check using DiD estimator.