?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

How do national regulatory agencies (NRAs) use digital practices to empower consumers for e-participation in regulatory processes? To address this question, we designed a novel framework to comprehensively capture digital practices adopted by NRAs across the key regulatory procedures, including consumer information provision, communication, education, and rule-making, which we conceptualise as two-way relational mechanisms. To measure the scope of digital regulatory practices, we derived composite digital scores for 236 NRAs across 42 EU and OECD countries, based on coding the regulators’ websites and social media accounts. We also developed a new multidimensional construct of organisational capacity to explain the variation in the adoption of digital regulatory practices among NRAs with sole – and multi-sectoral competencies in five economic markets, ranging from utilities to financial services. Our findings show significant regional divergence in the adoption of digital regulatory practices by NRAs from the old and new EU member states, as well as the significant effect of NRA’s reform experience, resources allocations, sectoral competencies, and in-house capabilities on their digital scores. This study offers implications for both improving the effectiveness of regulatory procedures through consumer-oriented digital transformation, as well as government initiatives for enhancing digital trust and e-participation in economic regulation among consumers.

Introduction

Over the past decade, economic regulators have invested considerable resources in adopting digital practices that aim to enhance consumer e-participation in regulatory processes. The organisations use digital technologies to provide consumers with information and education and to facilitate consumer feedback, account holding, and dispute resolution. The increased reliance on these practices reflects the wider digitalisation of government (e.g., Verhoest et al., Citation2024), including public sector interactions with citizens (e.g., Lindgren et al., Citation2019). Moreover, digital technologies have helped economic regulators respond to a particular challenge they faced; namely, how to centre their work more on the interests and input of consumers. Regulators still consider competition a key means to promote the interests of consumers, but have felt both a need and external pressure to take up a more active role by empowering consumers in markets and engaging more with consumer input in the regulatory process (e.g., Blakelock & Turnpenny, Citation2022; Stern, Citation2014; Waddams Price, Citation2018).

The adoption of digital practices for consumer e-participation represents a substantial change in the way economic regulators work. For instance, the move to online consultation procedures introduces new challenges such as how to cope with mass comments (Balla et al., Citation2022). As for the relationship between regulators and consumers, digital practices convey a promise of easy, cost-effective, scalable, and mutually beneficial interaction, and even though our understanding of the impact of e-government on attitudes like trust is limited (e.g., Mahmood et al., Citation2019), citizens do expect the availability of digital channels for interaction with government organisations. At the same time, such interaction requires digital access, skills and confidence, which means that it may not be equally available to different categories of consumers (cf. Robinson et al., Citation2015; Van den Berg et al., Citation2020). Consumer e-participation also depends on awareness of regulators and regulatory processes, which may not be warranted, or may at least be variable (e.g., Farina et al., Citation2011).

Yet, for any of these questions to be fully addressed, we first need to understand how and to what extent regulators adopt digital practices for consumer e-participation, and how we can understand the adoption of these practices. As we will show, consumer e-participation comes in different shapes and forms, and its scope depends on the economic and institutional context; all of which matters for an appreciation of the practices’ normative and positive implications. In this study, we seek to improve our understanding of consumer e-participation by conducting a cross-national and cross-sectoral analysis of the digital practices of economic regulators, and by tracing their adoption back to organisational capacity, controlling also for the sector – and country-specific environment.

Our study makes three important contributions. First, we conceptualise digital practices for consumer e-participation in economic regulation. Second, we develop a multidimensional conceptualisation of the organisational capacity of economic regulators and formulate propositions on its relationship with the adoption of digital practices. Third, we systematically collect and analyse data on the digital practices and the organisational capacity of 236 economic regulators operating in the 42 member states of the European Union (EU) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Our focus on EU and OECD members allows us to assess the variation in digital practices across regulators who interact regularly with each other in a transnational contextFootnote1 but are embedded in distinct institutional settings.

By making these contributions, we seek to address two main gaps in the literature. First, our study complements the literature on e-government in general, and digital interactions between the public sector and citizens in particular. The government practices facilitating these interactions have been conceptualised and operationalised (e.g., Frach et al., Citation2017; Lindner et al., 2019; Puron-Cid et al., Citation2022; Verhoest et al., Citation2024), and the barriers to interaction have been assessed (e.g., Pérez-Morote et al., Citation2020; Van den Berg et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, empirical studies have provided insight into selected interactions such as the impact of the digitisation of benefit systems (Larsson, Citation2021), digital public service encounters in welfare-to-work programmes (Breit et al., Citation2021), and the use of dashboards to empower citizens in ‘smart cities’ (Matheus et al., Citation2020). Yet, the policy field of regulation has been notably absent from analyses of public sector interactions with citizens, even though regulatory policies and decisions affect many aspects of citizens’ lives, especially in their capacity as consumers. Our conceptualisation and cross-country comparison of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation are aimed to address this gap.

Second, we seek to add to the emerging literature on the digitisation of (economic) regulation. This literature has shown that regulators rely increasingly on digital tools to engage with regulatees and enhance regulatory monitoring and enforcement processes (e.g., Coglianese, Citation2020; Ulbricht & Yeung, Citation2022; Zeranski & Sancak, Citation2020). Furthermore, a study of a newly created platform called ‘Regulation Room’ reported that e-participation in consultation procedures can be enhanced by providing citizens with more accessible consultation documents, embedded videos, and the option to add comments to documents and ask questions via a blog (Farina et al., Citation2011). Yet, to the best of our knowledge, there is no literature yet that systematically and comparatively captures and analyses regulators’ digital practices for consumer e-participation.

Before we proceed, two key concepts need to be clarified. First, by economic regulators, we mean those ministerial divisions and independent agencies that are responsible for economic regulation. Regulation refers here to the intentional intervention by public organisations in the economic activities of private companies, involving binding standard setting, monitoring, and sanctioning (see Koop & Lodge, Citation2017, p. 105), whilst the adjective economic points to those forms of regulation that are aimed at market creation and the correction of market failure. Our sample includes regulators in the areas of competition policy and energy, water, communications, postal services, railway, and financial market regulation. Second, by consumers, we mean citizens in their capacity as current or potential customers in those markets that are overseen by economic regulators, with the concept of citizen referring to a country’s adult and adolescent population, regardless of people’s legal status.

Our paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we develop a new framework of regulator-consumer interaction via digital platforms. In the study design section, we introduce the novel coding scheme for the data collection and the operationalisation of two key constructs, i.e., digital regulatory practices and multidimensional organisational capacity. We subsequently discuss our findings on the relationship between the regulators’ digital practices and their organisational capacity and formation, as well as the variation across regions, countries, and sectors. In the final section, we draw conclusions for regulatory practice and public policy. Supplementary materials and the detailed analysis of regulators’ organisational capacity are provided in the online Appendix.

Towards a new framework of digital regulator-consumer interaction

Establishing two-way relational mechanisms via digital platforms to empower consumer e-participation in economic regulation

The lack of research on the extent of digitalisation of regulatory institutions and their role in facilitating consumer e-participation is striking, given the novel theorising advanced in the literature on the digitalisation of private institutions (e.g., Hanelt et al., Citation2021; Hinings et al., Citation2018) and multi-disciplinary theoretical approaches developed in e-government research (e.g., Bannister & Connolly, Citation2015; Rana et al., Citation2015; Verhoest et al., Citation2024; Wirtz & Daiser, Citation2018).

Moreover, the increasing institutional pressures to digitise citizen-centred services in public sectors (Bennich, Citation2024), conveyed by national governments and supra-national agencies over the last decades, coincided with a more active deployment of supervisory technologies by regulatory agencies, frequently named as SupTech or RegTech (e.g., Aktas & Roland, Citation2021; Grassi & Lanfranchi, Citation2022; Zeranski & Sancak, Citation2020). Although past studies have acknowledged the challenges and value of digital adoption to enhance perceived legitimacy and collaborative end-user involvement – e.g., based on trust-building, shared goals, and information exchange among the stakeholder groups (Gil-Garcia et al., Citation2019; Wouters et al., Citation2023) – the growing adoption of digital tools in regulatory practice has not yet been adequately conceptualised (and measured) so that their effectiveness for consumer participation in regulatory processes could subsequently be assessed in research and digital policy initiatives.

This study addresses the highlighted conceptual and methodological shortcomings in the field of economic regulation by (1) developing a new analytical framework integrating the stakeholder perspective to comprehensively capture digital instruments or mechanisms deployed by national regulatory agencies (NRAs) to enhance the involvement of consumers into regulatory processes – which we define as digital regulatory practices, (2) carrying out a cross-sector comparative analysis of digital regulatory practices towards consumer e-participation in economic regulation across the EU and OECD member states, and (3) conceptualising the multidimensional construct of organisational capacity to explain the variation in the adoption of digital practices by economic regulators endowed with diverse combinations of organisational capabilities and resources.

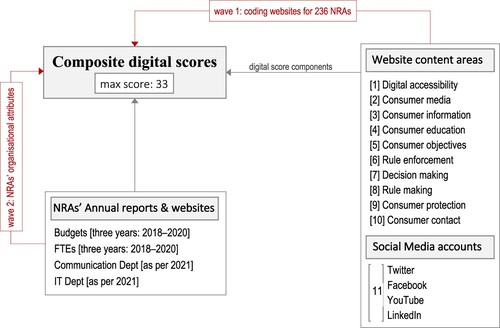

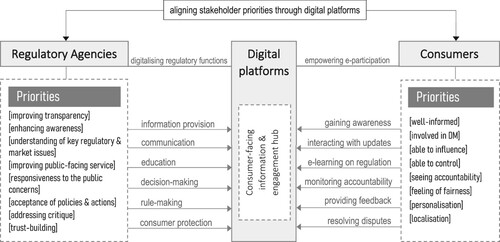

To enhance the concept of a ‘digital regulator’ that has emerged in the recent literature on regulation of rapidly digitalising economies (Van Loo, Citation2017), we centre our analytical framework on the adoption of digital practices used by regulators to interact with consumers via digital platforms, the basic form of which are the organisational websites and social media. In line with the theoretical perspective on stakeholder participation in collaborative processes (Freeman, Citation1984; Mitchell et al., Citation1997; Polonsky et al., Citation2003; Riege & Lindsay, Citation2006), we conceptualise that the digitalisation of the key regulatory procedures of information provision, communication, education, decision – and rule-making, and consumer protectionFootnote2 can facilitate the establishment of two-way relational mechanisms for regulator-stakeholder engagement through digital platforms ().

Figure 1. Regulators’ websites as digital information and engagement hubs for consumer e-participation in economic regulation.

By adopting this relational perspective on regulator-consumer interaction, we aim to advance the conventional approach in the economic regulation literature confined to theorising ‘informed consumer’ decision-making and information disclosure as a key regulatory tool (Pappalardo, Citation1997; Sunstein, Citation2012; Van Loo, Citation2017). We achieve this by developing a novel multidimensional approach to analysing the adoption of digital regulatory practices that include a comprehensive array of the key regulatory procedures beyond one-way consumer information provision. Although we do not measure actual consumer participation, this multidimensional approach enables us to explicitly conceptualise the varying extent of consumer involvement in the processes of economic regulation facilitated by distinct digital regulatory practices, which we further define as consumer e-participation in regulatory processes.

Regulators can harness the societal power of digital technologies not only to meet the requirements on information disclosure and transparency to facilitate information exchange among stakeholder groups (Verhoef et al., Citation2021), but also enable more effective knowledge-based social participation (Piskur et al., Citation2014) and foster stakeholder collaboration (Gil-Garcia et al., Citation2019; Scholl & Scholl, Citation2014) within their regulated sectors. By co-performing mandated functions through digital platforms, economic regulators can, consequently, improve their service delivery (Gil-García & Pardo, Citation2005; West, Citation2004) and the agility in their responsiveness to dynamic market environments (Vaia et al., Citation2022).

From a regulatory standpoint, the consumer-facing information and engagement hubs with improved digital accessibility and interactivity offer a powerful tool to align the priorities of different stakeholder groups – a central challenge in the digitalisation of public services (Gil-García & Pardo, Citation2005). In contrast to the traditional hub-and-spoke or contractual models of the stakeholder-agency theory (e.g., Hill & Jones, Citation1992), establishing interactive regulator-consumer processes via digital hubs can significantly enhance their perceived usefulness (Rana et al., Citation2012), mutual trust building, and uptake on the side of consumers (Welch et al., Citation2004), subsequently leading to their collaborative participation in the regulatory process. From the market governance perspective, reducing information asymmetry among a diverse range of stakeholders in economic regulation can be an effective remedy against market failures (Sunstein, Citation2012; Tirole, Citation2015), enabling regulators to indirectly curtail unfair practices, such as mispricing, non-competitive corporate behaviour, short-term political pressures and rent-seeking, and windfall profiting during times of crisis.

Furthermore, knowledge-based interaction among the main stakeholders within the regulatory system (i.e., the industry, state, and citizens), facilitated by digital regulatory hubs, can also prevent the control of the regulatory processes by either of these parties and the imbalance of market power. Democratisation of the regulatory process through digital adoption by involved stakeholders can improve accountability and transparency of regulatory decision-making (Scholl & Scholl, Citation2014), subsequently strengthening the independence of regulatory institutions and securing their legitimacy within the national and regional institutional system.

In line with the construct of increasing social participation (Piskur et al., Citation2014), we further conceptualise that regulators can adopt digital practices to empower increasing levels of consumer involvement in the regulatory process: from (1) visiting regulators’ websites for news releases, (2) interacting with specialised consumer information on the dedicated webpages or consumer portals, (3) joining e-learning programmes on educational portals created by regulators to transform consumers’ roles in the market, (4) gaining understanding of sector-specific legislations and monitoring regulatory decisions on individual cases published as website databases, (5) actively contributing to rule-making process and providing feedback on policy drafts, (6) gaining sovereignty in resolving disputes with businesses and the regulator itself, to (7) directly contacting regulators via website forms and social media. Therefore, we define all seven levels of consumer interaction with the regulators’ digital information and engagement hubs as consumer e-participation in regulatory processes ().

Although we do not aim to capture the uptake on the side of consumers, regulators’ practices adopted to designing their digital information and engagement hubs can significantly change the extent of consumer e-participation in the regulatory processes, which has also been supported by the vast literature on repeated consumer interactions with organisational websites and their perceived utility and empowerment (e.g., Alden et al., Citation2016). In order for researchers and policy-makers to meaningfully estimate the varying extent of consumer involvement in the regulatory processes, it is important to measure and analyse the adoption of digital practices by economic regulators that would comprehensively encompass the key regulatory procedures, which we set as a prime focus for this study.

We aim to overcome the acknowledged methodological shortcomings in the public administration literature on digital adoption (e.g., Bannister & Connolly, Citation2015; Yildiz, Citation2007), by developing a consistent measure of the scope of digital regulatory practices adopted by regulators across all key regulatory procedures that can facilitate consumer e-participation, whether specified in the mandates or voluntarily set by the regulatory agencies as part of their organisational goals. These digitally-enhanced regulatory procedures specifically include: media communication, consumer information provision, consumer education, rule-enforcement, rule-making, consumer protection, and consumer contact ( and ). With this multidimensional approach, we capture a comprehensive range of digital mechanisms that be adopted by regulators to enhance consumer e-participation in economic regulation. This is important for understanding how regulators digitise their key regulatory procedures towards consumers, and, more broadly, the extent of digital transformation of the regulatory process that is relevant to empowering consumers for involvement in economic regulation.

To create a consistent and comparable measure of digital regulatory practices adopted by economic regulators in cross-country settings, we introduce a new scheme to code the digital procedures for consumer e-participation made available by regulators on their websites and social media, which enables us to (1) measure the level of adoption of digital regulatory practices by economic regulators with a composite digital score across the specified regulatory procedures, and (2) to systematically compare the adoption levels, as measured with composite digital scores, among the regulators with supervisory powers across major economic sectors and across countries ().

Figure 2. Conceptual framework: the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation.

To create these composite digital scores for individual regulators, we develop a detailed mapping of relevant content areas on the regulators’ websites that can facilitate consumer e-participation ( and online Appendix B). We further code these websites areas across a large sample of economic regulators operating in five economic sectors, including competition authorities, and 42 EU and OECD countries (Tables A1–3, online Appendix). Mapping the differences in adoption levels among national regulators (as measured with regulators’ composite digital scores) enabled us to estimate the gaps in the available digital regulatory procedures for consumer e-participation in economic regulation across the new and long-time EU member states, and, more generally, the pre-conditions for ‘participatory regulation’ (Haber & Heims, Citation2020) in countries with diverse economic and institutional legacies.

The adoption of digital regulatory practices: the role of regulators’ organisational capacity

Although the adoption of digital technologies in regulatory practices enables new cost-effective channels to improve regulatory quality, gaps in organisation-specific capabilities may hinder the agile transformation of regulatory institutions within the integrated economic environment.

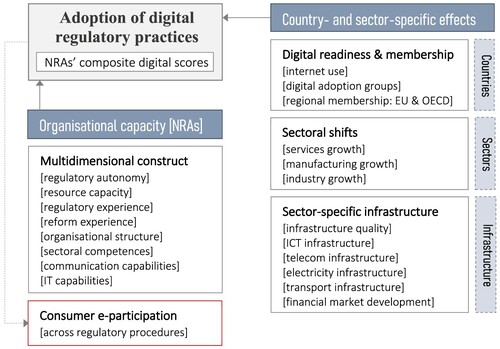

Following the multi-level frameworks of organisational innovation adoption (Frambach & Schillewaert, Citation2002) and contingency models of innovation attributes (Gopalakrishnan & Damanpour, Citation1994), we conceptualise that digital adoption levels are determined by a wide range of digital-related organisational characteristics, which may significantly vary across countries and sectors. To explain the patterns of variance in digital regulatory practices, we hypothesise and model the effects of organisational attributes, while controlling for sector – and country-specific environment (). Despite the vast legacy of the organisational capacity literature, with a number of capacity assessment frameworks developed for private organisations (Baser & Morgan, Citation2008; Cox et al., Citation2018), at the time of writing, we have not identified any coherent organisational capacity models specifically developed for regulatory agencies.

Therefore, we harness insights from the strategic management and public administration literature to create a multidimensional construct of organisational capacity for regulators, as it defines the adaptive ability of regulators to learn new ways of performing their mandated functions and organisational goals, pro-actively adopt these innovative practices, and embed them within existing regulatory processes. Specific to the operations of regulators, we complement external and internal dimensions of organisational capacity (Christensen & Gazley, Citation2008; Fowler & Ubels, Citation2010) relevant to the adoption of innovative digital practices and engagement with heterogeneous stakeholder groups ().

Regulatory autonomy

Traditional to both the public management and regulatory governance literature (Christensen & Lægreid, Citation2007; Ibsen & Skovgaard Poulsen, Citation2007; Lægreid & Verhoest, Citation2010; Larsen et al., Citation2006; Verhoest, Citation2010), we include a measure of regulatory autonomy, which is a key prerequisite to regulators’ openness to experiment with innovative practices. Independent decision-making is an enabling attribute of self-effective leadership that instils greater internal receptivity towards innovating routine regulatory practices, in contrast to external institutional stimulus underpinning ‘forced innovation adoption’ (Ram & Jung, Citation1991); whereas the lack of autonomy was widely acknowledged as a major deterrent to innovation adoption by the innovation norm frameworks (Feldman, Citation1989; Gieske et al., Citation2016; Russell & Russell, Citation1992). Pro-innovation leadership would enable independent regulatory agencies to transform their service delivery (Bekkers et al., Citation2014; West, Citation2004) and strengthen their commitment to digitally enhance interactive processes for multi-stakeholder engagement. The pro-change attitude represents an innovation-enabling norm that was linked to intra-organisational acceptance and continued use of innovative digital practices (Frambach & Schillewaert, Citation2002). This would, in turn, enhance regulators’ ability to independently decide for adopting new digital practices ahead or in absence of government and industry pressures for digitalisation and maintain their leadership positions in digital regulation at the international level.

The autonomy of economic regulators is, in itself, a multi-faceted concept (Verhoest et al., Citation2004), intertwined with other dimensions of organisational capacity as outlined further on, and we primarily aim to capture the legally granted independence of regulators, as it reflects the implemented governance arrangements for independent decision-making, transparency and balanced commitment to multiple stakeholder groups, which are comparable across countries and sectors. We, therefore, consider the regulatory autonomy as one of the key innovation enablers, and postulate that:

Proposition 1: Decision-making autonomy of regulators is positively associated with the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation.

Resource capacity

Organisational access to resources provides a core capacity for non-profit organisations as it constitutes the bottom-line assets for regulators to effectively perform their functions and adopt innovative digital practices. Originally underpinned by the resource-based view (Barney, Citation1991; Barney et al., Citation2001), the role of resource capacity in organisational innovation has been long integrated within the multi-level frameworks of organisational innovation adoption (Frambach & Schillewaert, Citation2002); and past studies found that the size of organisational resources was positively associated with innovation adoption, albeit to a lesser extent for public organisations (Damanpour, Citation1992).

In the regulatory context, human capital is an important component of resource capacity, not only in the form of the availability of experts for routine regulatory tasks, but also as regulators’ managerial capacity and pro-innovation leadership to reconfigure internal digital governance systems and implement a new vision for digitalisation of the regulatory procedures. Rooted in the transformational leadership theory (e.g., Bass, Citation1985), enhanced managerial capacity can function as an innovation enabler, attenuating the impact of budgetary shocks and other environmental pressures on the performance of supervision duties and delivery of public programmes (Andrews & Boyne, Citation2010; Krueathep et al., Citation2010; O'Toole & Meier, Citation1999, Citation2010).

Access to enhanced human capital can be a particularly advantageous resource endowment for regulators that were established as new institutional entities in the recent digital era, as human capital capacity underpins other constructs of innovation-enabling norms and superior external engagement practices of public organisations (Teodorovicz et al., Citation2023). Superior management capacity, transformational leadership vision, and pools of expertise can buffer newly-formed regulators against adverse political and industry pressures, enabling them to swiftly adapt to the emergence and diffusion of new digital models and improve the fit with stakeholder expectations.

Furthermore, digital governance frameworks repeatedly emphasised the role of organisational human capital in designing the components of digital systems, for both private and public services (Scholl & Scholl, Citation2014), and, importantly, bringing them into interaction with stakeholders. This view also resonates with the innovation management frameworks (e.g., Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990; Zahra & George, Citation2002), advocating that human capital can enhance an organisational absorptive capacity, which is especially important for newly-formed regulators that cannot capitalise on longer operational experience and priorly accumulated knowledge.

Financial or budgetary capacity, nonetheless, remains an important determinant of regulators’ capability and commitment to implement new digital practices, which we combine with the dimension of human capital. Regulatory budgets constitute a more complex measure of organisational resources compared to revenues generated by private firms, especially in the cross-country and cross-sectoral context with distinct national budgetary systems for economic regulation. The impact of budget size (and its increases or cuts) on innovation adoption is intertwined with the notion of financial autonomy of regulators (Wassum & De Francesco, Citation2020), and their synergetic impact defines the regulator’s ability to generate own revenues and allocate budgeted resources to implementing new digital vision. In contrast to past studies that used organisational size as a predictor of organisational innovation (Camisón-Zornoza et al., Citation2004; Damanpour, Citation1992), we conceptualise that the access to increased financial resources for regulators may alter their motivation and commitment to enhance digital engagement with other stakeholder groups. We, therefore, complement the resource-based arguments with the innovation norms frameworks, and postulate that:

Proposition 2a: The resource capacity of regulators, including both the financial and human resources, is positively associated with the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation.

Proposition 2b: Access to enhanced human capital and increased financial resources is more important for newly-formed regulators in adopting digital regulatory practices, compared to agencies with longer regulatory experience.

Regulatory experience

Building and leveraging managerial capacity for creating public value is closely related to the organisational experience of regulatory agencies – a traditional proxy for dynamic capabilities in the strategic management literature (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000; Teece, Citation2007; Winter, Citation2003); though its multifaced nature was largely overlooked by the regulatory governance studies which predominantly focused on regulators’ age (e.g., Maggetti, Citation2007). The time span of independent decision-making and setting organisational priorities, including the digitalisation of regulatory procedures, indeed reflects regulators’ ability to integrate their resource base and operational capabilities, and re-configure those over time in response to exogeneous innovation pressures from digitalising economies and societies, and sustain their independent digital vision under changing political agendas. However, the length of regulatory operations since the establishment of an agency is not the only dimension of its organisational experience; thereby, we enhance the analysis by incorporating the measure of organisational reforms.

The reforms of national regulatory systems were commonly coupled with creating new or transforming existing agencies, either as a response to supra-national regulatory initiatives or on a course of transforming domestic policies. The impact of regulatory reforms on the adoption of digital practices by regulators reflects a complex interplay of endogenous and exogeneous changes, which we capture with a regulator-specific measure of reform experience. The impact of re-organisations on digital adoption has incited conflicting interpretations in the strategic management and organisational change literature (Edwards, Citation2000; Poole & Van de Ven, Citation2021). On the one hand, organisational restructuring can create a major challenge for building a long-term managerial capacity and implementing an innovative digital vision, especially when government mandated changes are undertaken with cost saving objectives and lead to re-structuring of regulators’ governing boards. Moreover, the repeated re-organisations of regulators can act as an innovation deterrent, which can disrupt the realisation of their long-term strategies, including the digitalisation of regulatory procedures.

On the other hand, organisational transformations – either in the form of regulatory mergers or re-organisations, – can create a strategic change momentum (Barker et al., Citation2018; Beck et al., Citation2008) and provide effective incentives for traditionally more sluggish public organisations to adopt innovative digital practices and foster digital linkages to the key stakeholder groups. Regulatory reforms during the recent era of pro-active digitalisation across regulated sectors and citizen-centric state governance programmes may enhance regulators’ internal receptivity towards digitising regulatory procedures, compared to the regulators that were established in the pre-digital era, without any further re-organisations, and may have fewer incentives to reconfigure their routine practices and adapt their long-term vision towards digital adoption. This positive effect on digital adoption, however, may depend on whether the regulator developed sufficient managerial capacity and budgeted financial resource to integrate a new digital vision when overcoming the hurdles of transition periods. Hence, we consider the complementarity between organisational change, human capital, and financial resources committed to digital transformation as an enabler for digital adoption, and postulate that:

Proposition 3a: The reform experience of regulators is positively associated with the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation.

Proposition 3b: Access to enhanced human capital and increased financial resources is more important for regulators with reform experience, when adopting digital regulatory practices, compared to regulatory agencies that continued their regulatory activities without re-organisations.

Organisational structure

The resulting organisational structure is crucial to the regulator’s ability to strike a balance between the autonomy to implement new digital vision, the access to core resources needed to accomplish digital transformation, and sustaining balanced linkages with the key stakeholder groups. The structural theories of innovation have suggested that less formalised and centralised organisational structures with lower levels of bureaucratic control, while endowed with greater organisational complexity and functional differentiation, can facilitate innovation adoption (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, Citation1998; Frambach & Schillewaert, Citation2002; Zaltman et al., Citation1973).

Specific to the governance arrangements within national regulatory systems, regulators can be established with stand-alone organisational structures and independent governance boards or be integrated within hybrid, i.e., semi-autonomous structures. Independent agencies linked to executive government bodies, or operating as part of the organisational hierarchy of a parent organisation, may experience more bureaucratic control which, in result, can limit the regulators’ autonomy to initiate digitalisation and commit resources, subsequently, inhibiting innovation adoption. In the course of mergers and re-organisations, previously independent agencies can be absorbed by other agencies or government bodies and function as departmental units without own budgets and independent governance boards.

Whereas the semi-autonomous structures allow regulators to draw upon larger pools of resources and digital vision of the parent organisation; a greater bureaucratic control within centralised and formalised organisational designs can constrain the regulator’s capacity for leadership in adopting innovative digital practices vis-à-vis its fully autonomous peers in other sectors and countries. Hence, we consider the independent organisational structure with a lower degree of bureaucratic control as an enabler of digital innovation, and postulate that:

Proposition 4: The independence of organisational structure is positively associated with the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation.

Sectoral competences

The regulatory reforms and organisational transformations are frequently complemented with changes in regulators’ sectoral competences and mandated powers, the scope of which may have a profound effect on the adoption of digital regulatory practices. In line with the structural theories of innovation (e.g., Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, Citation1998; Russell & Russell, Citation1992), a greater organisational complexity and functional differentiation of multi-sector regulators can lead to synergy realisation based on knowledge exchange between sector-specialised divisions, and, subsequently, facilitate innovation adoption. Furthermore, regulatory agencies with granted multi-sectoral competences can leverage their more central position within national institutional systems and a diversified pool of in-house expert knowledge to lead in the digitalisation of regulatory practices. However, the innovation-enabling effect of the instrumental power of multi-sector regulators may depend on their managerial capacity to coordinate the knowledge exchange and diffusion of innovative digital practices across sectoral units within the organisational structure.

Conversely, a stronger power position within the national governance system, granted and secured by the national legislative framework, can instil organisational inertia towards adopting new digital practices and skew managerial incentives towards private rent-seeking. This barrier to pro-active digital adoption can be particularly discernible in countries with lower levels of transparency in regulatory processes and less experience of democratic governance. We follow the knowledge-based approach to adopting innovative digital practices and, hence, postulate that:

Proposition 5: Multi-sector competencies of regulators are positively associated with the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation, albeit with significant differences between old and new EU member states.

Organisational capabilities

Related to the human capital capacity as an enabler of organisational innovation adoption, establishing dedicated departments for stakeholder communication and IT support enhances regulators’ capacity to adopt new digital practices (Bullen et al., Citation2007; Goh & Arenas, Citation2020; Pang et al., Citation2014; Wehmeier & Winkler, Citation2013). Communication and IT capabilities can also feed into other constituent components of regulatory capacity, such as greater organisational complexity and experience, exerting positive synergetic effects on absorptive capacity (Cuevas-Vargas et al., Citation2022). The in-house communication capability of regulatory agencies constitutes a particularly important reputation – and legitimacy-enhancing tool, enabling them to effectively convey their mission to key stakeholders and build competence-based trust with the public. Communication departments can transform traditional stakeholder communication tools or mandated information discloser functions into a digital communication strategy that can be wired into the strategic design of regulatory information hubs, and effectively diffuse new digital practices across the supervision departments.

Developing in-house IT capabilities can be a long process especially for less agile public organisations, which traditionally underinvest in their IT infrastructure and lag behind in the digitalisation of their core functions. Once upgraded, regulators’ IT departments can speedily reshape the legacy IT infrastructure, innovate new consumer-facing regulatory portals, and deploy up-to-date digital functionalities across regulatory platforms. Dedicated digital transformation departments can experiment with interactive website designs and collect metrics of consumer e-participation, increasing regulators’ responsiveness to new digitalisation targets and the effectiveness of regulatory actions – both at the back – and front-end of regulatory activities. Furthermore, the specialised digital communication and digital transformation departments embedded within regulators’ organisational structures are indicative of a receptive organisational culture and the organisation's readiness for change (Frambach & Schillewaert, Citation2002). Such intra-organisational receptiveness, along with the continued use of digital technologies, can lead to the pro-active digitalisation of regulatory practices towards consumer e-participation. Hence, we postulate that:

Proposition 6: The in-house communication and IT capabilities of regulators are positively associated with the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation.

Study design

Sampling approach: consumer markets across geographically and institutionally diverse economies

To measure and analyse the scope of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation, we created a new dataset comprising a total number of 236 national regulatory agencies involved in economic regulation. To this end, we accomplished two waves of the data collection and merged the digital scores of regulators with their organisational attributes.

The sampling process started with selecting market sectors that have a major impact on citizens’ well-being and potential for consumer participation in regulatory process, and, at the same time, render a more standardised representation across diverse country economies, avoiding sectors with resource – or location-determined specialisation, such as maritime transport or the fishing industry. In result, the dataset construction evolved around six consumer-frontend service sectors: energy utilities, water utilities, telecommunication services, passenger rail transportation, postal services, and financial services, also including competition authorities with regulatory powers in consumer markets, which often share regulatory functions with sector-specific agencies (online Appendix Table A1).

We extended the data sampling across the second dimension to include all 27 EU member states, and 15 non-EU countries which are OECD members, to make digital regulatory practices comparable within the EU-regulated area and across five other regions (online Appendix Table A2). The focus on the OECD members, with higher rates of consumer e-participation, digitalisation of service sectors, e-government development, and democratic performance will allow collecting best regulatory practices and foster spillovers to catching-up countries outside of the OECD club. Importantly, we included the complete range of EU countries to achieve the comparability in the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation in economic regulation within the EU regulatory area, and, particularly, estimate the differences in (1) the available digital regulatory procedures for consumer e-participation and (2) the role of multidimensional organisational capacity across the new and long-time EU member states.

Within these sectors and countries, we applied two criteria to sampling organisations: (1) it must be mandated to regulate prices and service quality in a sector, i.e., defined as economic regulation (e.g., Decker, Citation2015; Joskow & Rose, Citation1989; Posner, Citation1974), and (2) it must be a national – or federal-level agency (i.e., excluding sectoral regulators at sub-national level). The competencies of the selected economic regulators were allowed to overlap with other types of regulation, such as social, safety, and environmental objectives, though not to be solely focused on these. Table A1 in the online Appendix summarises the selection criteria across all sectors.

The total sample included 236 national economic regulators, 193 of which are sector-specific regulators, whereas 43 regulatory agencies have broader mandates across two or more sampled sectors. The multi-sector regulators are dominant in postal services (86.5 per cent), telecommunication services (76.8 per cent), water services (59.1 per cent), while the energy and financial sectors, as well as antitrust behaviour, are largely supervised by sole-domain regulators. The regulatory independence in decision-making is more equally featured across sectors, with a higher number of ministerial units only among the rail regulators (16.7 per cent). The country distribution for both sole-sector and multi-sector agencies depicts the national regulatory systems within and beyond the EU, also characterising how many agencies in a country have independence in making regulatory decisions (online Appendix Table A2).

Data collection (wave 1): estimating composite digital scores of economic regulators

The first wave of data collection focused on coding the website content of the sampled economic regulators and their adoption of social media accounts (), which we conceptualise as digital information and engagement hubs that can improve consumer awareness and facilitate consumer e-participation in economic regulation (). To develop the coding scheme, we identified 11 content areas on regulators’ websites which can be used as digital channels to foster consumer engagement with information resources available on regulators’ websites (areas 1–7), consumer e-participation in regulatory processes (areas 8–9), as well as consumer interaction with regulators via digital platforms (online Appendix Table B1).

Each of these content areas is related to a regulatory procedure either legally defined in the statutes, such as information provision, decision-making, rule-enforcement, and consumer protection, or pursued by regulators as part of their organisational objectives, e.g., creating media pages, educational programmes, and directly engaging with consumers via helplines, web-chats, and social media accounts. and Table B1 (online Appendix) reflect the composition of the coded digital scores linked to the regulatory procedures adopted by the sampled economic regulators and regulatory outcomes. This detailed mapping of regulatory procedures (see online Appendix B) is essential for capturing the variation in digital mechanisms adopted by economic regulators, reflecting a comprehensive range of priorities () that incentivise consumers to e-participate in economic regulation.

Data collection (wave 2): creating the multidimensional construct of organisational capacity

To account for organisational capacity as a source of variation of regulators’ website content scores (), we proceeded with a second wave of data collection (). Within public and private management fields, the organisational capacity of public service and non-profit organisations has been defined as an inherently multidimensional construct – i.e., a set of organisational attributes measuring structure, resources, strategies, and processes – both internal and external – that affect organisational ability to perform its core functions, develop, and improve (Christensen & Gazley, Citation2008).

To operationalise the organisational capacity of regulators, we defined one external and seven internal organisational attributes that may specifically affect the regulator’s ability to adopt digital practices for consumer e-participation, and, at the same time, be standard to operations of regulators across all sampled sectors. The internal capacity dimensions include: (1) allocated financial resources, (2) allocated human resources, (3) organisational experience, (4) organisational structure, (5) competences, (6) communication, (7) IT capability, and the external dimension captures (8) the level of regulator’s autonomy (online Appendix Table C1).

We collected the data on each organisational capacity attribute for 236 economic regulators; both waves of data collection were accomlpished during 2021. Further details on the operationalisation of regulators’ organisational capacity and sources are provided in the online Appendix C.

Estimation strategy

Although past studies acknowledged that the role of organisational factors and their interaction with digital adoption is hard to assess, especially for public services in cross-country settings (e.g., Seri & Zanfei, Citation2013), we developed an estimation strategy to examine the role of the operationalised multidimensional construct of organisational capacity in the adoption of digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation, as measured with regulators’ digital scores. To analyse the variation in digital practices adopted by economic regulators , across sectors

and countries

, and formally test the associative propositions (1–6), we build the following model:

(1)

(1) The dependent variable

reflects the individual digital scores assigned to each economic regulator, based on the web-coding scheme (online Appendix Table B1). Accordingly, the dependent variable is constructed as a sum of individual binary and categorical codes (Indices 1–11) that measure the scope of digital practices adopted by regulators, approximating the extent of digitalisation of regulatory processes for consumer e-participation.

The construct was included in the model as a set of independent variables measuring: (1) regulatory autonomy (

and

), (2) independence of organisational structure (

), (3) organisational experience (

and

), (4) resource capacity (

and

), (5) sectoral competences (

and

), and (6) in-house communication and IT capabilities (

and

). The operationalisation of each dimension is defined in Table C2 (online Appendix C); whereas the online Appendix D provides the detailed analysis of the organisational capacity of the sampled economic regulators in relevance to their digital scores. The propositions (1–6) that conceptualise the relationships between the digital scores of regulators and their digital-related organisational capacity attributes were estimated using an OLS regression method (). To account for heterogeneity, we included the country and sector fixed-effects in each model and further conducted robustness checks by (two-way) clustering standard errors at the sector and country level.

The control variables identify two groups of country – and sector-specific effects, of which the operationalisation and data sources are specified in Table C3 (online Appendix C). The first group includes country-level variables that control for: (1) digital readiness among country populations (

and

), as a proxy for varying pressures from the public to digitalise citizen-centred regulatory institutions, and (2) regional membership (

and

), as a proxy for institutional differences which we use to quantify the divergence in digital regulatory practices within and beyond the EU regulatory area. To estimate the varying effectiveness of the EU regulatory initiatives for consumer e-participation across old and new member states, we further test interaction effects between the constructs of organisational capacity and the EU membership categories.

The second group includes a set of sector-level indicators that control for (1) shifts in the sectoral composition of the EU and OECD economies, accounting for the varying growth in service economies and their financialisation that may drive regulatory priorities towards consumers, and (2) the quality of sector-specific infrastructure, whereby the regulators of the capital-intensive industries of the advanced economies may seek more pro-active involvement of consumers in regulatory decision-making via digital platforms, as the financialised clients of sectoral infrastructure. The additional model specifications for sector-level effects are provided in the online Appendix E (Tables E1–2).

Data analysis and findings

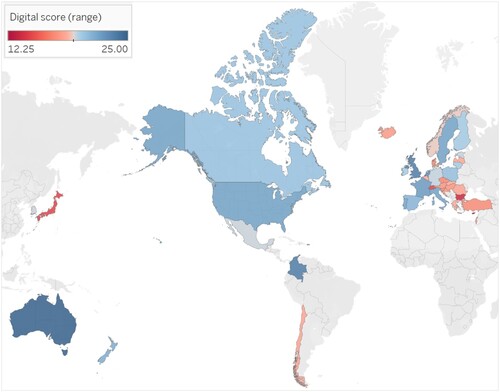

Mapping the variation in the digital scores among economic regulators

To account for differences in the national regulatory designs, we calculated the average digital score for each country, as a mean of all individual scores obtained by its sector regulators (). The calculated average country scores are distributed within a wide range: from the minimum of 12.3 (Cyprus) to maximum of 25 (Australia), depicting the high variability in the digitalisation of regulatory procedures for consumer e-participation (). The digital scores of individual regulators are even more widespread, ranging from the minimum of 3 (the Registrar of Occupational Retirement Benefit Funds, Cyprus) to the maximum of 29 (the Federal Telecommunications Institute in Mexico), showing large gap in the adoption of digital regulatory practices among the countries and individual regulators.

Table 1. The adoption of digital regulatory practices: cross-country variation.

Notably, none of the countries reached the maximum score of 33, with an average digital score of 19.2 across the entire sample of 236 regulators (equating to 58.1 per cent of the maximum score), whereas 25.2 per cent of the sector regulators attained digital scores below the mid-value of 16.5 (relative to the maximum score of 33). Out of 42 sampled countries, only half attained digital scores above the sample average, which is unexpectedly low given that 88.1 per cent of our sample are the developed OECD economies with established digital governance frameworks for public services and institutionalised consumer protection policies.

The EU member states that joined before 2000 are the best performing country group that achieved the highest average digital score of 20.2, as well as featuring the highest minimum and maximum individual scores, and the lowest standard deviation among the sector regulators (2.91 vs. the sample average of 4.71). The EU initiatives for building citizen-centric models and digital public services since late 1990s resulted in higher levels of up-take among the EU regulators; though the gap in adoption of digital regulatory practices between the old and new member states is striking.

Despite receiving the dedicated budgeting support for implementing digital initiatives from the EU-level agencies, the average digital score of the new-joiner group (17.7) remained 1.5 points below the sample average and 2.5 points below the average score of the old member states. The digital scores were also more widely dispersed among individual sector regulators in countries which joined the EU after 2000 (std. dev. of 4.25), highlighting notable divergence in the digitalisation of regulatory institutions and the adoption of citizen-centred practices. Importantly, the new member states scored below the sample average in the adoption of digital practices for each regulatory procedure, apart from providing information for consumers on how to contact the regulator and embedding the digital functionality for directly contacting the regulator via its website (e.g., a web-chat), in which the new joiners scored just above the average level.

Does the organisational capacity affect the adoption of digital regulatory practices?

In order to explain the observed variability in the adoption of digital practices for consumer e-participation by the regulators across different regions and sectors, we proceed with testing the effects of regulators’ organisational capacity and its interplay across different organisational formation groups (). The detailed analysis of organisational formation and the multidimensional organisational capacity of the sampled economic regulators is provided in the online Appendix D.

We captured the multidimensional nature of organisational capacity of the sampled regulators by creating separate measures for each of the constitutive constructs; that is, regulatory autonomy, resource capacity, organisational experience, organisational structure, sectoral competences, communication and IT capabilities (online Appendix Table C2). Subsequently, we tested their effect on the adoption of digital regulatory practices across individual regulators with OLS models estimated at the level of individual regulators, while controlling for country – and sector-specific effects (). The dependent variable is defined as the composite digital score obtained by each regulator across all coded content areas on the regulators’ websites.

Table 2. The effect of regulators’ organisational capacity and country membership on the adoption of digital regulatory practices.

Regulatory autonomy

Even though the operational objectives of regulatory agencies are confined by the legislative frameworks and regulators remain accountable to the state executive offices, we found the significant effect of the regulatory independence in decision-making on their pro-activeness in adopting digital regulatory practices (Models 1–9, ). This result is consistent with past research in public management that underscored the importance of decision-making autonomy for organisational innovation (Demircioglu & Audretsch, Citation2017; Feldman, Citation1989; Wynen et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the relationship between regulatory autonomy and digital scores remained significant after controlling for the regulators’ organisational hierarchy and semi-autonomous structures that approximate the extent of self-management among the sector regulators. Unexpectedly, however, the independence of regulators’ organisational structure did not prove to be related with more pro-active adoption of digital practices for consumer e-participation, challenging the arguments of the structural innovation theories in the regulatory context.

The effect of regulatory independence in decision-making also remained significant after we controlled for institutional pressures from higher levels of digital readiness among the country populations and government incentives for early digitalisation of public services. These findings underscore the importance of the autonomy of regulatory institutions in implementing citizen-centric policy designs and involving consumers in policy-making across economic sectors. The effects of other organisational attributes were more nuanced, given the contrasting interpretations in the management literature and diverse digital practices adopted by national regulators, particularly, within the EU regulatory area.

Regulatory experience

The longer span of regulatory experience under the current statutory duties did not seem to bring a significant advantage for adopting digital practices, even though it is positively associated with regulators’ digital scores (Model 1, ). The resource-based argument did not hold in the context of digitalisation of regulatory institutions. Although the length of organisational operations can facilitate the build-up of expert knowledge in sector regulations and rule-making experience, the economic regulators did not seem to leverage this capability to create comprehensive information hubs on their website. The insignificant relationship between the regulators’ experience and digital scores, however, is not surprising given the intensity of regulatory reforms over the last two decades (see online Appendix C for a detailed discussion).

The reform experience since the onset the digitalisation efforts in public services, indeed, proved to have a significant effect on the adoption of digital regulatory practices among the sector regulators, though in diverse ways (Models 2–4, ). The regulators formed by taking over the duties of a predecessor were able to lead in implementing a digital vision for consumer participation, compared to the regulators that were established in the pre-digital era (before 2000) and, evidently, had fewer incentives to digitalise their information provision and transform their websites into the hubs for consumer engagement.

The hurdles of post-merger integration did not prove to be a limiting factor for the regulators that were formed through merging stand-alone sectoral regulators, as these also obtained significantly higher scores compared to the regulators that were established before 2000 and continued their operations without re-organisations. The merged regulators were able to leverage the internalised cross-sectoral expertise, bundled regulatory resources and powers to promote a wider implementation of participatory regulation across sectors. The lower coefficient compared to the re-organised regulators, however, may reflect a toll of post-merger transitions.

Although organisations that were newly established during the digital era tend to adopt a more consumer-oriented outlook and be more digitally driven, the regulatory ‘start-ups’ were evidently not created with a strong digital vision for consumer participation. The newly-formed regulators significantly lagged in adopting digital regulatory practices and information provision across regulatory procedures on their websites compared to the regulators that were established in the pre-digital era.

This finding is alarming, as it questions either the rationale behind the national regulatory reforms or the approach of newly-formed regulators towards implementing the EU directives and e-governance frameworks. Unexpectedly, the availability of digital technologies and functionalities across industries and public services did not enable the newly-formed regulators to overcome the lack of experience in the sector supervision and constraint resources, particularly in the countries with limited tradition of independent regulatory institutions. To clarify this gap, future research can collect more fine-grained evidence on digital leadership and diffusion across different organisational groups.

Financial resource capacity

The effect of resource capacity has been exhaustively covered in the management literature, though it remains a double-edged sword for developing innovative organisational practices. Financial resource constraints can create barriers for adoption of digital practices within organisations, or, under different conditions, drive the digitalisation of organisational processes as a cost-efficient strategy to improve service delivery. For regulatory agencies, the effect of the resource capacity has another layer of complexity, as not all regulators are independent of the state budget and have revenues of their own.

Our sample represents a diverse mix of financially independent authorities (e.g., the BaFin in Germany, the Institute for Regulation in Luxembourg, and the Regulatory Authority for Energy in Greece) and those that do not have financial autonomy to allocate their fee-raised revenues and commit financial resources to strategies outside of their statutory duties, especially if the digitalisation of consumer information provision is not incentivised by monitoring institutions. At the same time, we noted regulatory agencies with dedicated digitalisation funds within their budgets, e.g., the Regulatory Authority for Broadcasting and Telecommunications in Austria.Footnote3 Besides, the size of the resource capacity of regulatory agencies also depends on the scope of their sectoral competencies, and whether they implement infrastructure investment projects.

Contrary to past research, the effect of budgetary capacity on the adoption of digital practices by regulators proved to be insignificant (Model 4, ), as the overall budget amounts do not reflect the scope of funds dedicated to regulatory digitalisation and consumer initiatives. The regulators established before the year of 2000 were the only group that benefited from larger budget allocations, as it was confirmed by a positive coefficient of the interaction term (Model 1, ). Given the budgetary expansion that we noted across a large number of countries (online Appendix Table D4), our finding raises questions on the priorities behind budget rises, if these have not yet translated into the wide-spread adoption of digital practices for participatory regulation. To verify these findings, future research can specifically capture the scope of resources allocated for digitalisation of regulatory processes and consumer engagement projects.

Table 3. The interaction effects between regulators’ resource capacity, reform experience, and country membership.

Human resource capacity

Human capital capacity plays a different role in service-centred organisations, as the pool of expert knowledge is the key resource for enhanced information provision across multiple regulatory procedures. The availability of niche expertise in sectoral regulation was found to vary across countries (e.g., Banks, Citation2005), as the independent sector regulators face challenges to balance the skill-sets and leverage the cross-team expertise, while attached agencies and ministerial unites are often under the threat of over-staffing and absorbing the staff from ministries.

Despite the underlying complexities, the effect of human capital, as measured with a number of FTEs, on the regulators’ adoption of digital practices for consumer participation was positive and strongly significant (Model 3, ). Along with the insignificant effect of financial resources, this finding amplifies the importance of organisational leadership to create a digital vision on regulatory activities and leverage internal human capital to implement it with consumer objectives in sight. The importance of human capacity remained significant and positive for all regulator formation groups, except for those regulators which were newly-formed after the year of 2000 (Model 2, ). This may indicate a lag in the ability of newly-formed regulators to leverage larger pools of existing expertise for consumer objectives and building their digital leadership.

Sectoral competences

The efficiency of multi-sectoral regulation was acknowledged in past research, particularly for smaller economies and converged industries (Karnitis, Citation2015; Karnitis & Virtmanis, Citation2011; Lyon & Li, Citation2004; Valiente, Citation2014), covered in our sample. The impact of cross-sectoral regulatory design on the digitalisation of regulatory practices, however, is not straightforward. The regulator’s ability to pool cross-sectoral competencies may reduce information asymmetries in monitoring the performance of market sectors, given the effective coordination and communication systems established between the sectoral divisions. The cross-divisional synergy realisation can facilitate the digitalisation of regulatory processes and enhance information provision for consumers via digital channels. The reduced autonomy of sector-specialised supervision and divisional status within the organisational structure of multi-sector regulators, however, may reduce incentives for regulators to pro-actively adopt innovative practices. This accentuates the importance of transformational leadership and digital vision to coordinate the adoption of digital practices across sectoral divisions within multi-sector regulators.

The multi-sector regulators in our sample are a diverse group, established predominantly in the EU regulatory area after 2000, either through re-organisations of predecessor regulators, mergers, or as new institutional entities, with different scopes of resource capacity across regional groups (online Appendix Table D3). The five super-regulators with sectoral competences consolidated by competition authorities tend to have higher digital scores, e.g., the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (27), the New Zealand Commerce Commission (27), and Spanish National Commission for Markets and Competition (24). The multi-utility regulators were also effective in digital adoption, with digital scores above the sample mean: the Latvian Public Utilities Commission (23) and the German Federal Network Agency (20). The average digital score of the 27 integrated telecom and postal regulators also reached above the sample average (21).

Compared to regulators with supervision competences in a single sector, the digital scores of the multi-sector regulators were more narrowly concentrated around the mean, though with two outliers: the multi-utility regulators in Bulgaria and Malta. Across the diverse regulatory designs within the sampled sectors, the regulators with multi-sector competences obtained significantly higher digital scores (Model 5, ); and this effect sustained for super-regulators with a larger number of sectors within their authority (Model 6, ). Given the diverse resource capacity among the multi-sectoral regulators, our finding re-enforces the importance of cross-divisional coordination and information exchange for the enhanced adoption of digital practices across regulatory procedures.

Communication capabilities

Information provision is a standard statutory requirement of regulatory agencies; however, with enhanced communication and IT capabilities the regulators can transform the routine reporting process into a digital strategy for stakeholder engagement. Consistent digitalisation of information provision across the key regulatory procedures can create multiple digital channels for consumers to interact with regulatory information on the regulators’ websites and social media accounts and participate in the regulatory processes. Regulators with stand-alone communication departments can leverage their in-house capabilities to integrate the statutory information provision with consumer digital communication strategy, enhancing their digital capacity.

The Competition Council in Latvia, for instance, developed the digital communication strategy to reach consumer audiences with a variety of digital tools on regulatory topics, with a strategic vision to promote the competition culture and communicate the authority’s decisions.Footnote4 The Competition Council in Luxembourg launched the awareness-raising and communication advocacy programme via its website and social media; whereas the Luxembourg Institute for Regulation implemented a digital communication strategy with the support from its Electronic Communications Department. Indeed, the relationship between the in-house communication capabilities and adoption of digital regulatory practices is significant across all model specifications (Models 1–9, ), and even greater for those regulators that created dedicated digital communication departments.

IT capabilities

Complementing communication capabilities with in-house IT support can create synergies enabling regulators to develop innovative approaches towards participatory regulation. The overwhelming evidence on benefits of IT-enabled capabilities within private and public organisations (Li et al., Citation2022; Mergel et al., Citation2009, Citation2019) has direct implications for adopting innovative digital practices and building public engagement capabilities by independent regulatory agencies. Even though the previous studies considered the IT functions within regulatory agencies to be diminished, dissolved across divisional structures, and under-resourced (e.g., Banks, Citation2005), we found numerous examples of advanced digitalisation programmes launched by the sector regulators within recent years.

The Financial Sector Supervisory Commission (CSSF) in Luxembourg, for instance, incorporated the 4.0 strategy to transform its core organisational functions and establish real-time information exchanges with its stakeholders; while the digital transformation of the Authority for Communications Guarantees (AGCOM) in Italy followed a more technical approach and prioritised the development of ‘digital administration’ services and integrated data systems for its operations.Footnote5

Indeed, the regulators with stand-alone IT departments within their organisational structures tend to have significantly higher digital scores, and especially those with the dedicated digitalisation or digital transformation departments (Models 1–4, ). Future research could complement both sources of digital transformation capabilities within regulatory agencies, and capture the effects of outsourcing IT functions by sectoral regulators, as we noted the cases of external contracts for IT services in annual reports of regulators, e.g., the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets followed an outsourcing strategy for its IT services.Footnote6

Regional divergence in digital regulatory practices

The regulatory landscapes of the sampled EU and OECD countries have evolved along the distinct paths of re-organising existing regulators and developing new institutions, which endowed their regulatory states with different resource capacity, digital capabilities, and consumer-oriented outlook (online Appendix Tables D1–3). The nation-specific efforts in building regulatory capacity and adopting digital regulatory practices has contributed to a notable regionalisation, as we found the significant differences between the regional groups in the allocated budgets for economic regulation, available regulatory expertise, and digital scores (online Appendix Table D4). The gaps in digital adoption between the regions were defined by higher priorities towards consumer education and protection of the non-EU countries, and higher levels of transparency in regulatory decision-making and encouraging consumers to participate in rule-making process among the EU member states.

The member states that joined the EU before 2000 obtained a higher digital score (average per group), as their regulators were more effective in building up their digital capabilities, while concurrently maintaining lower costs of economic regulation per capita. This advantage in adopting digital regulatory practices for consumer e-participation, however, did not prove significant against the non-EU countries (Model 7, ). The EU regulatory harmonisation indeed proved a ‘slow strategy forward’ (Egan, Citation2001), as we found significant disparities in the adoption of digital regulatory practices between the old member states and new joiners. Even after implementing the pre-accession requirements for market competition and transposing the EU directives in the post-accession stage, the regulators in the new member states lagged in their information provision across all regulatory procedures and obtained significantly lower scores compared to both the old EU member states and the non-EU countries.

Overall, digital technologies seem to effectively create new channels to spread participatory regulation given the diverse institutional legacy of the countries in our sample. This innovation-enabling effect, however, was significantly lower in the EU new-joiners with distinct institutional backgrounds in transforming their regulatory systems. Multi-sectoral regulatory design, however, proved to be more effective for adopting digital practices among the EU’s new joiners, as their multi-sectoral regulators obtained a higher average digital score (21.1) and a positive coefficient of the interaction term, in sharp contrast to their sole-sector regulators (Model 3, ).

The level of economic development and embedded democratic institutions of the OECD countries do facilitate the adoption and diffusion of digital regulatory practices, as evident from the significant difference between the most developed countries that became OECD members before 2000 and the least developed (non-OECD) economies in our sample (Model 8, ). In contrast to the EU’s new joiners, the new OECD members were as effective in the adoption of digital regulatory practices as the long-time OECD members (Model 8, ). Digital technologies allowed the catching-up economies which joined the OECD club more recently (after 2000) to close the gap in participatory regulation with the established economies. Once the level of economic development, among other institutional factors, is improved, digital technologies facilitated the adoption and diffusion of consumer-oriented regulatory practices among the OECD new-joiners (Model 9, ). This finding confirms that the sectoral development and institutionalised democracy are prevailing in their effect on digital participatory regulation compared to the formal efforts to harmonise the legislative base and regulatory regimes.

Fit with consumers’ digital readiness

The significant variation in the adoption of digital regulatory practices were formed under the pressure of the improving consumer digital readiness and changing sectoral composition within the EU and OECD economies. The effect of consumer digital readiness, as measured with the average internet use percentage over 10 years prior to coding the regulators websites (2010–2019), was positive across all sectors, but not significant given the divergent regulatory priorities to consumer e-participation that we observed among regional groups. By contrast, the multi-sectoral regulatory design more effectively facilitated the fit between digitising their consumer-centred regulatory practices and consumers’ digital norms. Among the sector-specific regulators, however, only the financial supervisory authorities were significantly more receptive towards consumer digital pressures (Models 2–9, ).

Table 4. The effects of consumer digital readiness on the adoption of digital regulatory practices, by sector.

The sampled OECD and non-OECD countries were catching-up with digital use among their populations at different speeds, and to capture this effect, we classified the countries into three digital adoption groups: (1) the first adopters which had the internet use rate above 50 per cent of their populations by 2000, (2) the early adopters with 50 per cent of their population regularly using internet by 2005, and (3) the late adopters that reached the 50 per cent internet use threshold only by 2010. Both early and late adopters proved to have lower digital scores among their sector regulators compared to the countries that were first to reach a wide internet usage rate.