ABSTRACT

Rapid urbanisation presents multiple opportunities, but also poses challenges for equitable distribution of gains from socio-economic developments. This systematic review explored the role of social inclusion within the urban sustainability agenda.

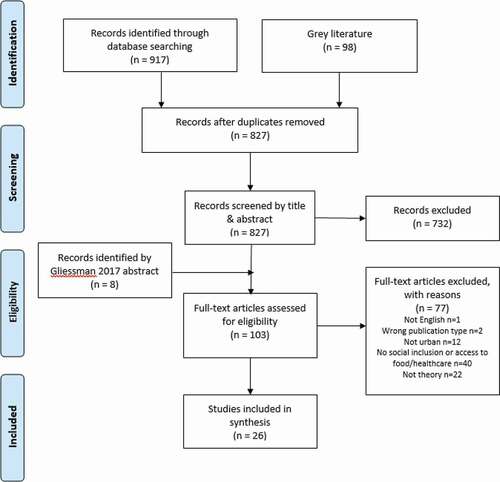

Sustainable urban developments were conceptualised as comprising environmental, spatial, social and economic perspectives; and social inclusion as entailing access to core services (healthcare) and resources (food). A search of five databases and grey literature returned 1,015 articles; 26 papers were included following screening using pre-determined criteria. Data was analysed thematically. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations were followed.

Most included studies were from North America and few were from Africa and Asia. More empirical than conceptual studies were found, and more focused on food than healthcare. Social inclusion was generally included within the urban sustainability but was often an autonomous component, rather than mainstreamed, within urban sustainability. Social inclusion was mostly related to multiple elements of sustainability, with the greatest focus on combinations of environmental, social and economic opportunities for under privileged groups. However, less consideration was given to gender, ethnicity and other aspects of intersectionality. Multiple theories contributed to transferability of lessons.

Key policy implications include prioritising the most vulnerable socially excluded populations, ensuring equal representation in urban planning, designing people-centred systems, building partnerships with communities, considering socio-cultural-political-economic contexts, and recognising both intended and unintended effects. More research is needed in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) on the role of social inclusion in achieving sustainable development, using cross-disciplinary approaches.

Introduction

The world is rapidly urbanising, with 50% of the population in Asia and 43% of the population in Africa already living in cities in 2018 (UN DESA Citation2018). Urbanisation presents multiple opportunities for socio-economic development and shaping the quality of life for billions of urban dwellers (Murali et al. Citation2018) especially in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Environmental and social demands also create new challenges for individuals and institutions within the contexts of major social, technical and political changes (Gomes and Hermans Citation2018; GPSC World Bank Citation2018; European Commission Citation2020). Urbanisation also affects progress towards achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations Citationn.d.), particularly Goal 11 (Sustainable cities and communities), but also Goals 10 (Reduced inequalities), 3 (Good health and well-being) and 2 (Zero hunger) which emphasise the importance of equitable distribution of socio-economic opportunities of urban development. While frameworks for understanding and improving sustainable urban developments are becoming increasingly available (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Cohen Citation2017; GPSC World Bank Citation2018; European Commission. Citation2020), the degree to which the urban sustainability agenda considers and promotes social inclusion is less well-understood.

Definitions of sustainable urban developments or urban sustainability emphasise maintaining and improving quality of life for all population groups (Wu and Wu Citation2010; Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Turcu Citation2013; Huang et al. Citation2015; Cohen Citation2017; UN DESA Citation2018). Four underlying constructs or components of urban sustainability can be discerned from the literature: ecological or environmental, comprising issues of pollution and climate conscience (Turcu Citation2013; Chaudhary et al. Citation2018; Eme et al. Citation2019), socio-cultural and spatial, including distribution and access to spaces and resources (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Turcu Citation2013; Cohen Citation2017; El Bilali et al. Citation2019; Hailemariam et al. Citation2019), economic, including financial, business and employment-related issues (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Turcu Citation2013; Cohen Citation2017; Eme et al. Citation2019), and institutional and political, which include local facilities, services and partnerships (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Turcu Citation2013; Cohen Citation2017; Hailemariam et al. Citation2019). While there is a general lack of a unified framing (Cohen Citation2017), approaches to implementing urban sustainability include collective objectives for cities (Cohen Citation2017; UN DESA Citation2018) and principles for neighbourhood developments (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Turcu Citation2013). Specific ways of ensuring urban sustainability include developing partnerships and sense of community, providing access to basic resources and services, building resilience, and ensuring spatial heterogeneity in occupying urban spaces – all without leaving a burden on future generations of communities (Wu and Wu Citation2010; Turcu Citation2013; Huang et al. Citation2015; Cohen Citation2017; UN DESA Citation2018).

Social inclusion has become an increasingly common, albeit contested term (O’Donnell et al. Citation2018). It essentially entails the process of improving the terms of participation in society for social groups that experience disadvantage, through enhancing opportunities, access to resources, voice, and respect for rights on which individuals and groups take part in society (United Nations Citation2016; O’Donnell et al. Citation2018; Mir et al. Citation2020; Uzochukwu et al. Citation2020; WHO Citationn.d.). Social inclusion results in productive, cohesive and safer societies, with less social tensions and violent conflicts (United Nations Citation2016). It is a key social determinant of well-being, with significant economic and social gains determined by the degree to which individuals and groups access public services (such as healthcare and education), and resources (such as land and the labour market) (Gerometta et al. Citation2005; United Nations Citation2016). Social exclusion, an opposite of inclusion, is driven by dynamic and multi-dimensional processes (WHO Citationn.d.) encompassing unequal power relationships interacting across four dimensions (economic, political, social and cultural) and across individual, household, group, community, country and global levels (Mir et al. Citation2020; Uzochukwu et al. Citation2020; WHO Citationn.d.). The conceptual relationship between social exclusion and health is related to urban/rural residence, especially in older adults (Dahlberg and McKee Citation2018).

Access to services (such as healthcare) and resources (such as food) are themselves complex and multi-faceted phenomena. Access to healthcare is shaped by multiple socio-cultural, economic, infrastructural and physical influences including availability of affordable healthcare within responsive health systems (George et al. Citation2015; United Nations Citation2016; WHO; WHO, UN-Habitat Citation2016; Mirzoev and Kane Citation2017; Javanparast et al. Citation2018; Fenny et al. Citation2019). The concept of food security entails everyone’s continuous physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life; it also encompasses availability, stability, accessibility and utilisation of food (Weiler et al. Citation2015; WHO; WHO, UN-Habitat Citation2016; Moragues-Faus and Carroll Citation2018; El Bilali et al. Citation2019).

In this systematic review, we explore whether and how sustainable urban developments recognise and address social inclusion. This paper should be of interest and relevance to academics who are interested in advancing the understanding of inter-relationships within sustainable developments agenda, and policymakers and funders who are interested in ensuring the best value for money from their decisions and investments into sustainable urban developments.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted within a broader SINC-Urban study, which sought to synthesise evidence on the role of social inclusion within sustainable urban development in LMICs, to inform engagements with relevant policymakers and other key stakeholders in Nigeria and Vietnam.

The objective of this review was to understand the degree to which social inclusion is considered within sustainable urban developments, addressing two questions:

What is the role of social inclusion within urban sustainability?

Which theories underpin the consideration of social inclusion within urban sustainability?

We defined sustainable urban development as improving the quality of life in urban contexts through environmental, economic, socio-cultural, institutional, and political aspects, whilst ensuring access to basic resources and services, resilience, spatiality, and without leaving a burden on future generations. Social inclusion is understood as participation in, and access to, services (specifically healthcare) and resources (specifically food and nutrition) amongst all populations, particularly disadvantaged and marginalised groups. We interpreted the term ‘theory’ flexibly, to include both substantive (social) science theories and conceptual frameworks articulating programme theories (Mehdipanah et al. Citation2015).

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations (Moher et al. Citation2009), and the Cochrane guidance for conducting systematic reviews were followed (Higgins et al. Citation2020). PROSPERO protocol registration CRD42020165008.

A rapid literature review was conducted to identify the knowledge gaps, develop our working definition of urban sustainability and criteria for the systematic review. We included all study types and grey literature published in English since 2000 (to capture the sustainability agenda since the start of the Millennium Development Goals). Specific inclusion criteria were evidence of: (i) theories to rationalise changes to (ii) an urban environment to enable (iii) equitable access to healthcare or food, as a reflection of social inclusion. We included studies of individuals or groups irrespective of age, ethnicity, gender or their socio-economic status.

The search strategy was guided by database index terms and text words for the following search concepts: urban sustainability, social inclusion and theories (see sample strategy in ). Medline, Web of Science, Scopus, CAB Abstracts and Transport Database were searched in January 2020, followed by searches for grey literature in the global development websites (3ie website, WHO IRIS, the World Bank Open Knowledge Repository) in February 2020. Data from all regions were explored, but only English language full texts were included.

Table 1. Sample search strategy

The screening was conducted in two stages using Rayyan QCRI software (Ouzzani et al. Citation2016). First, titles and abstracts were divided and independently screened for eligibility by five review team members, with 20% of the samples from each member co-screened to ensure consistency. Then, the full text screening stage was divided between four team members with each text screened by at least two researchers. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussions between relevant members.

The initial searches identified 1,015 records, which were reduced to 827 after removing duplicates. Further eight records were identified within one record (Gliessman Citation2017). Screening by title and abstract identified 103 articles eligible for full-text review. Studies were excluded on the basis of language (n = 1), wrong publication type (n = 2), no urban context (n = 12), no attention to social inclusion or access to food/healthcare (n = 40), and no theory (n = 22). The details are documented in the PRISMA flow diagram (), and 26 studies were included for data extraction and analysis.

Data was extracted in tabular format in Microsoft Excel. The extraction template was initially piloted on two records, then three reviewers independently extracted data from each study the spreadsheet. Data retrieved from each study included publication details (author, year, study type, location); component of urban sustainability; theory used; access to healthcare/food, and target population(s).

The extracted data were analysed thematically, using a qualitative narrative synthesis approach (Snilstveit et al. Citation2012). Data analysis was conducted by three authors, structured around the two review questions and components of our working definitions of urban sustainability and social inclusion.

Quality assessments were performed on all articles using JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute) critical appraisal checklists. All papers were included. On average, the articles scored 78.4%, and included urban sustainability elements and substantive theories. One record (Boschmann and Kwan Citation2008) had unclear data extraction and critical assessment methods in its research synthesis, but was still included as the theoretical approaches to accessing food or healthcare were described in detail.

Results

There were slightly more empirical (13/26) than theoretical and conceptual (9/26) studies (see ). More papers focused on South America and global research (5/26) compared with Asia (2/26) and Africa (4/26). Twice as many empirical studies were reported from South America (4/26) than from Asia and Africa, respectively (2/26 each), only one regional conceptual paper was from Asia. The majority focused on access to food rather than healthcare, with 10/26 focused on conceptual frameworks whilst 5/26 focused on substantive theories.

Table 2. Studies by geography, access, and group identified

Results are summarised in , and are elaborated next by our review questions.

Table 3. Summary of studies included in the review

Consideration of social inclusion within urban sustainability

Published research focusing solely on individual aspects of urban sustainability was limited (environment and social/spatial 3/26 each, economic 2/26, and no papers on institutions). Geographically, most papers focused on North America (7/26), rather than Africa, Asia or South America. Most papers (16/26) focused on combinations of environmental, social, and economic opportunities for under-privileged social groups. There were more of these studies from Asian and African cities. Social inclusion was most often explored in relation to environmental aspects of urban sustainability (12/26). Combinations of environmental and social/spatial (8/26) and environmental & social & economic (8/26) were also frequently covered. However, coverage of social and spatial aspects of urban sustainability were the sole focus in fewer (4/26) papers, and only 2/26 papers focused on economic approaches to ensuring urban sustainability.

Different aspects of social inclusion were included in 21/26 papers, with most research reported from the Americas (11/26) and multiple countries (5/26). More studies focused on access to food (16/26) rather than healthcare (5/26) and 5/26 covered both access to food and healthcare. Similarly, more articles focused on environment and social sustainability for nutritional need than for access to health (6/26 and 1/26, respectively). Most papers covering access to food focused on North America, with only one paper being from Africa. There was no literature on access to healthcare within contexts of urban sustainability from Africa, and only one from Asia. In the articles that did address healthcare in urban environments, most (3/26) were conceptual.

One paper illustrated two distinctive approaches to ensuring accessibility: location (place) accessibility, and individual (personal) accessibility, drawing on a theory of justice (Boschmann and Kwan Citation2008). From the sustainable urban developments perspective, such an approach is similar to the need to provide meaningful livelihood opportunities to all urban inhabitants while maintaining its natural resource base, and not compromising the quality of its natural environment (Cohen Citation2017). We also found that a survey of European cities revealed that social inclusion questions had a lower response, indicating either the lack of information or limited actions by these cities (De Cunto et al. Citation2017). The authors found that the third sectors and the private sector and schools were better engaged in promoting social equity through education training and research, than regional central and local governments.

Overall, approaches to ensuring social inclusion within urban sustainability were found to be either plural (i.e. covering a mixture of disadvantaged groups), prioritising specific disadvantaged groups, or focused on all population groups. Examples of specific populations were – women and girls who were mostly constrained by poor slum infrastructure and limited human rights (Corburn and Karanja Citation2016), landworkers and food retailers in relation to food production and distribution (Donald Citation2008; Matteucci et al. Citation2016). Further specific disadvantaged groups included those on low-incomes, unemployed, with limited education, without fixed housing, and non-registered populations as key at risk groups for obesity and target groups for food security interventions in urban contexts (Rojas et al. Citation2011; Zhou et al. Citation2017). Older people were not specified; youth was only featured in one study, covering environmental and social elements (Yi et al. Citation2015). Less explicit attention was given to diverse populations, such as ethnic and religious minorities.

While there is substantial research on access to healthcare more generally, studies relating to urban sustainability are scarce. Among studies which did have such a focus, one related the WHO’s ‘Health in All’ policies to different SDGs in the context of urban transport planning (Ramirez-Rubio et al. Citation2019), drawing on an application of the SDG framework which highlighted the importance of government food subsidies for residents of urban slums (WHO and WHO, UN-Habitat Citation2016). Another study highlighted the links between inadequate sanitation and disease, social, economic, and human rights for women and girls as the most vulnerable in urban slums (Corburn and Karanja Citation2016). The ecological public health model was used to explore underlying structures of urban environments relating to public health and social equity in terms of lack of water, precarious public lighting, and transportation (Bentley Citation2014).

Theoretical underpinnings of social inclusion within urban sustainability

Multiple theories and conceptual frameworks underpinned consideration of social inclusion within urban sustainability. We found that 8/26 were theoretical, 17/26 were conceptual, and 1/26 combined the two approaches. Most papers (18/26) built on existing theories and 7/26 papers developed new frameworks or theories. Most papers (16/26) used practical conceptual frameworks, 7/26 used substantive social science theories, and 3/26 used both. Most studies related theories to high-income countries or adopted a global approach to understanding urban sustainability. A few empirical studies focused on Asia (2/26), Africa (2/26) and South America (4/26). Only one conceptual paper focused on Asia (3.85%), and none related to African or South American contexts.

An Urban Political Ecology approach can help understand how the transformation of urban landscapes and ecosystems constitutes a co-evolutionary process where technological and institutional interventions interact with values, imagination, and ecological processes, to produce new ‘socio-natures’(Moragues-Faus and Carroll Citation2018). A socio-ecological focus can specifically highlight the interplay of power, politics, income and place in understanding causes of poor health outcomes. The current notion of Urban Resilience (i.e. capacity of individuals and groups to survive, adapt and grow) often lacks adequate acknowledgement of the political economy of urbanisation, which is socially unjust (Béné et al. Citation2017). The concept of Socially Sustainable Urban Transportation (SSUT) was found to improve the understanding of equitable access to urban opportunities and minimise social exclusion, through highlighting urban structures of opportunity and ways to maximise benefits (Boschmann and Kwan Citation2008).

A Forest Transition Theory has supported understanding of rural-urban migration and how low-income landworkers are affected by progressive adjustment of agriculture to reduce the land needed for increasing food produce (Matteucci et al. Citation2016). An Affordance Theory (Chemero Anthony Citation2003, Citation2009; Stoltz and Schaffer Citation2018) considers the relations between individuals and urban green spaces to analyse their salutogenic (i.e. health and wellbeing) potential. An application of Theory of Land Use related obesity incidence with 5 socio-economic factors – low-income households, people in long-term unemployment; people without elementary school education, households without fixed housing, and non-registered population – and showed that people in neighbourhoods with more green spaces and institutional land have greater accessibility to health facilities (Zhou et al. Citation2017).

A concept of Urban Agriculture (i.e. the growing plants and rearing of livestock within or near towns/cities), along with a related concept of Edible City Solutions, was explored more in the Americas and the Middle East (Rojas et al. Citation2011; Matteucci et al. Citation2016; Oyuela and Van Der Valk Citation2017), and found to benefit food security, social integration and social cohesion (Cinà and Khatami Citation2017; Säumel et al. Citation2019; Zasada et al. Citation2020) and empower individuals and communities (Oyuela and Van Der Valk Citation2017). However, urban and peri-urban agriculture was found to play a relatively minor role in improving food provision and food cost reduction in Asia (Zasada et al. Citation2020).

A theory of Sustainable Food Capitalism helped to understand alternative food geographies and roles of transnational food retailers (Donald Citation2008) which can constrain affordability and accessibility of food for different socio-economic groups (Rojas et al. Citation2011). A Theory of Solidarity and Diverse Community Economies was proposed as a solution to the traditional constraints of capitalism (Loh and Agyeman Citation2019). The authors argued for application of an urban political ecology lens that can help transform the food economy for ‘communities of colour’ through reforming neo-liberalised policies and institutions, while at the same time building non-capitalist practices (Loh and Agyeman Citation2019).

A Social Practice Theory highlighted the importance of cultural, ethnic and religious identities in relation to inequities in food, water and transportation in the urban nexus in the neighbourhood of Novo Recreio, South America (Giatti et al. Citation2019). Similarly, key issues affecting health of aboriginal youth in Canada combined socio-economic, environmental and political issues (Yi et al. Citation2015). A Theory of Complex Adaptive Systems was used to understand cultural preservation in modernisation of food systems (Jiao et al. Citation2016). The only paper from Africa (Battersby Citation2019) assessed policies related to the concept of ‘food deserts’, concluding that the state’s antipathy towards informal food retailers was partly driven by racial segregation.

Two theories from food sciences can further understanding of the role of social inclusion within urban sustainability: Food Sovereignty and Food Citizenship. Food Sovereignty is a process of expanding democracy to regenerate local, autonomous, healthy, and ecologically sound food systems that respect the rights of people to decent conditions and incomes (Martin and Wagner Citation2018). Similar to health equity, Food Sovereignty can promote human thriving by equalising access to power and improving the flow of goods through the system (Weiler et al. Citation2015). Food Citizenship entails movement of individuals and organisations across the food system (Rojas et al. Citation2011). It is rooted in a belief that people, given the right conditions, want to and can improve the food system (Rojas et al. Citation2011), and would support a democratic, socially and economically just, and environmentally sustainable food system (Wilkins Citation2005). It recognises political and economic powers, and proposes a critical alternative to the current neoliberal model which favours market forces over equity considerations.

Specific attention was occasionally given to specific identities such as gender, disability, age or intersectional aspects of inclusion, though on the whole attention to these aspects appeared limited. One study focused on a trauma-informed social policy in the North America, which entails six core principles: safety, trustworthiness and transparency, collaboration and peer support, empowerment, choice, and the intersectionality of identity characteristics Hecht et al. (Citation2018) drawing on Bowen & Murshid’s framework (Citation2016). Attention to minority groups alongside socio-economic inclusion was also used in understanding ecological consequences of forest transition (Matteucci et al. Citation2016) and exploring food sustainability within school food systems (Rojas et al. Citation2011). A relational framework of place-based characterisation of informal settlements can help capture the forces contributing to existing urban health inequities, as was shown in the analysis of inter-relationships between inadequate sanitation and disease, social, economic and human rights for vulnerable women and girls within urban slums (Corburn and Karanja Citation2016).

Discussion

This systematic review set out to explore the role, and theoretical underpinnings, of social inclusion within the urban sustainability agenda. While previous reviews helped understand key guiding principles for sustainable urban developments (Luederitz et al. Citation2013) or approaches to assessment of urban sustainability (Cohen Citation2017), this review has pioneered a deeper understanding of the role of social inclusion within urban sustainability and should help decision-makers to ensure the best value for money from investments into sustainable urban developments.

Our overarching finding is that social inclusion is generally included within urban sustainability. For example, it constitutes parts of two (out of 15) principles of urban sustainability (Luederitz et al. Citation2013) and two (out of 30) objectives comprising five pillars of the Framework for Sustainable Cities (European Commission. Citation2020), or included within one of the four outcome dimensions in the Urban Sustainability Framework (GPSC World Bank Citation2018). However, the nature of conceptualisations of social inclusion suggests that understanding of its role differs greatly across contexts, and it can be regarded as a discrete and autonomous component rather than being mainstreamed. This echoes the current literature on social inclusion, which highlights its limited consideration within development literature (Mir et al. Citation2020).

This review was guided by four elements of urban sustainability from the literature: ecological or environmental (Turcu Citation2013; Chaudhary et al. Citation2018; Eme et al. Citation2019), socio-cultural and spatial (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Turcu Citation2013; Cohen Citation2017; El Bilali et al. Citation2019; Hailemariam et al. Citation2019), economic (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Turcu Citation2013; Cohen Citation2017; Eme et al. Citation2019), and institutional and political (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; Turcu Citation2013; Cohen Citation2017; Hailemariam et al. Citation2019). Social inclusion was mostly explored in relation to multiple elements of sustainability, with most papers covering environmental, social, and economic opportunities to under-privileged social groups, and less so in relation to social and spatial aspects or solely economic issues. Limited consideration was given to intersectional aspects of inclusion such as gender, ethnic and religious backgrounds, disability, migration status and age. Our findings also highlight that social inclusion entails addressing local underlying processes and interconnections (Turcu Citation2013) and permeating through multiple components of sustainability as well as individual, institutional and systemic levels of abstraction (Cohen Citation2017; Mir et al. Citation2020). Our results further emphasise the importance of prioritising those with greatest disadvantage and marginalisation, such as neglected ethnic and religious minorities within the UN’s Leave no one behind (LNOB) agenda (United Nations Citation2016; Mir et al. Citation2020; Uzochukwu et al. Citation2020).

A clear dominance of empirical literature suggests that scholars, and perhaps decision-makers, are more interested in practical explanations and lessons from implementation. This is understandable, given the applied nature of work on urban sustainability (Luederitz et al. Citation2013; GPSC World Bank Citation2018; European Commission. Citation2020). However, our findings also highlight the importance of robust theorisation as ways of ensuring a deeper understanding of how and for whom specific initiatives work to inform policies and programmes (Mehdipanah et al. Citation2015) through reflecting on, and ensuring, generalisability and transferability of experiences across the different contexts.

Five inter-related groups can be discerned in relation to theoretical conceptualisations of social inclusion within urban sustainability:

resilience theories such as Urban Resilience (Béné et al. Citation2017; Moragues-Faus and Carroll Citation2018) together with related concepts of Resilient Urban Food Systems (Hecht et al. Citation2018) and Socially Sustainable Urban Transportation (SSUT) (Boschmann and Kwan Citation2008);

social theories such as Social Practice Theory (Rojas et al. Citation2011; Yi et al. Citation2015; Giatti et al. Citation2019), Food Citizenship Theory (Rojas et al. Citation2011), and conceptualisations of intersectional characteristics within Food Deserts (Battersby Citation2019) and social and material flows across the Water-Energy-Food (WEF) urban nexus (Covarrubias Citation2019);

social and spatial theories such as Forest Transition (Matteucci et al. Citation2016) and Affordance Theories (Stoltz and Schaffer Citation2018), and the concepts of Urban Ecology (Bentley Citation2014), Urban Agriculture and Edible City Solutions (Rojas et al. Citation2011; Matteucci et al. Citation2016; Cinà and Khatami Citation2017; Oyuela and Van Der Valk Citation2017; Säumel et al. Citation2019; Zasada et al. Citation2020);

socio-economic theories such as Sustainable Food Capitalism (Donald Citation2008; Rojas et al. Citation2011); Theory of Solidarity and Diverse Community Economies (Loh and Agyeman Citation2019), and Food Sovereignty (Rojas et al. Citation2011; Martin and Wagner Citation2018); and

structural and target-driven theories such as a Complex Adaptive Systems (Jiao et al. Citation2016), the SDGs and Health in All Policies frameworks (Corburn and Karanja Citation2016; WHO; WHO, UN-Habitat Citation2016; Ramirez-Rubio et al. Citation2019) and indicators for a sustainable and resilient City Region Food System (Dubbeling et al. Citation2017).

This complementary and interdisciplinary body of knowledge highlights clear examples of social cohesion, empowerment and participation in improving access to resources and services. It arguably provides an excellent platform for advancing the conceptualisations and mainstreaming of social inclusion within the urban sustainability agenda.

There is a growing need for transforming urban environments into socially inclusive societies (Mir et al. Citation2020). Technology can be useful, but is not sufficient on its own (Bibri Citation2019) and one must factor in local, regional and global political cultures, geographical contexts, and governance regimes. Our results highlight six practical implications for improving the socially inclusive nature of future sustainable urban development policies.

First, a socially-inclusive urban sustainability agenda should prioritise the needs of the most vulnerable or disadvantaged such as women, deprived populations, ethnic minorities, migrants, and disabled people (United Nations Citation2016; Mir et al. Citation2020; Uzochukwu et al. Citation2020). Increased awareness and subsequent empowerment of local communities are critical, for example, a sustainable community urban food system should encompass social justice, food security and nutrition as key elements of territorial sustainability (Rojas et al. Citation2011; Carey and Dubbeling Citation2017; Dubbeling et al. Citation2017) to enhance the economic, environmental, and social environments (Rojas et al. Citation2011).

Second, policy measures and social movements have advocated, sometimes successfully, for more equal representation of all population groups in planning and organisation of services and mobilisation and allocation of resources (United Nations Citation2016). Such an approach can ensure that multiple perspectives are highlighted and considered in planning of sustainable urban developments to ensure that the needs of the most vulnerable and marginalised are heard, irrespective of gender, income, educational and cultural backgrounds of decision-makers (Rudolph et al. Citation2013; Carey and Dubbeling Citation2017).

Third, community-driven systems were proposed as a useful model for ensuring social inclusion, echoing findings from a study of food system sustainability within a Think&EatGreen@School community-based action research project (Rojas et al. Citation2011) and spatial assessment of urban scheme for agricultural activities (Cinà and Khatami Citation2017). The literature also shows that people-centred approaches can improve responsive and socially inclusive nature of health systems (Sheikh et al. Citation2014; Mirzoev and Kane Citation2017).

Fourth, strong partnerships between the public and the private sectors can leverage their complementary experiences in promoting equity through education, training and research as was shown in some European countries (De Cunto et al. Citation2017) where a combination of government, community groups and civil society organisations helped to forge an efficient and sustainable city food system that encompassed equity and social inclusion (De Cunto et al. Citation2017). It is important, however, to be cognisant of the profit-making agenda of some private sector agencies which may lead to leaving behind some population groups, for example, those who cannot afford specific services or products.

Fifth, any interventions should be cognisant of local socio-economic, cultural and political contexts. For example, the concept of food security entails a complex network of actors, processes and relationships to do with food production, processing, marketing, and consumption (Dubbeling et al. Citation2017), so it is critical to ensure its acceptability by all city residents with differing dietary habits, preferences and restrictions. A food desert policy narrative appears to be ill-informed by the lived experiences of food insecurity in African cities, and may therefore promote policy interventions that can erode rather than enhance its context-specificity within African urbanites (Battersby Citation2019). It is critical, therefore, to explicitly articulate key contextual facilitators and constraints of effective interventions (Mehdipanah et al. Citation2015) in exploring transferability of lessons across the different countries.

Sixth, approaches to understanding and improving social inclusion should consider both intended and unintended effects (Mehdipanah et al. Citation2015). City governments must plan for, and manage, the complex impacts of urbanisation on poverty, inequities, unemployment, transport, climate change, and politics. For example conserving and building home gardens can contribute to environmental and spatial while improving access to food (Zasada et al. Citation2020), but it can also improve people’s sense of belonging, desire to contribute to society, social cohesion and empowerment (Cinà and Khatami Citation2017; Oyuela and Van Der Valk Citation2017; Säumel et al. Citation2019; Zasada et al. Citation2020). Most literature posits food security in the nexus of environmental and socio-economic perspectives (Rojas et al. Citation2011; Dubbeling et al. Citation2017; Zhou et al. Citation2017; Covarrubias Citation2019), thus also highlighting the utility of cross-disciplinary approaches to understanding the complexity of intended and unintended effects.

Finally, we call for more research on the role of social inclusion specifically from LMICs, particularly the cross-disciplinary approaches. Genuinely socially inclusive sustainable urban developments require multi-sectoral approaches which target the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, and disaggregated data collection and analysis for different social and income groups would support this effort.

Study strengths and limitations

This study pioneered the comprehensive understanding of the role of social inclusion within sustainable urban developments. Our review was limited to studies published from 2000 onwards. While we did endeavour to capture important preceding resources through following up on references, we may have omitted some publications of significance. Our interpretations of sustainable urban developments and social inclusion focused on four key components of urban sustainability and access to food and healthcare. While our analysis was grounded in the current literature, we recognise that further elements of urban sustainability can be discerned, and the concept of social inclusion goes beyond access to services and resources. Our multidisciplinary team included experts from health sciences, food sciences, development studies and information specialists. We had more experts from health sciences, which may have resulted in enhanced scrutiny of health-related resources, and perhaps consequently greater number of excluded papers covering access to healthcare. However, our task-sharing and team meetings aimed to minimise this bias.

Conclusions

Social inclusion was generally present within urban sustainability agendas, but was often an autonomous component than being mainstreamed. Social inclusion was mostly related to multiple elements of sustainability, with most papers covering environmental, social, and economic opportunities to under-privileged social groups, and less so in relation to social and spatial aspects or solely economic or institutional issues, and with limited consideration of gender, ethnic and religious backgrounds, disability, migration status, age or other intersectional aspects. Multiple theories can deepen the understanding of social inclusion within urban sustainability agenda and contribute to transferability of lessons across countries. Key implications for policy and practice include prioritising the most vulnerable, ensuring equal representation of all population groups in decision-making and planning, designing people-centred and consumer-driven systems, building strong partnerships between governments, communities and civil society, considering socio-economic, cultural and political contexts in designing interventions, and recognising both intended and unintended effects. More cross-disciplinary research is needed on the role of social inclusion, particularly from LMICs.

Notes on contributions

TM, NW, YYG jointly conceived the study; NVK and JMW developed and implemented search strategy, updated the review documents, and completed the PRISMA diagram; KIT conducted the rapid review including initial searches; TM, KIT, NW, YYG and GM conducted screening, shared data analysis and wrote different sections; TM, KIT, NW, YYG, GM, NVK and JMW read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate assistance from Carolyn Czoski Murray (University of Leeds, UK) for sharing her expertise and specific advice on the choice of quality assessment tools

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Battersby J. 2019. The food desert as a concept and policy tool in African cities: An opportunity and a risk. Sustainability. 11(2):2. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020458.

- Béné C, Mehta L, McGranahan G, Cannon T, Gupte J, Tanner T. 2017. Resilience as a policy narrative: potentials and limits in the context of urban planning. Climate and Development. 10(2):116–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1301868.

- Bentley M. 2014. An ecological public health approach to understanding the relationships between sustainable urban environments, public health and social equity. Health Promot Int. 29(3):528–537. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat028.

- Bibri SE. 2019. On the sustainability of smart and smarter cities in the era of big data: an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary literature review. Journal of Big Data. 6(1):1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0182-7.

- Boschmann EE, Kwan M-P. 2008. Toward socially sustainable urban transportation: progress and potentials. Int J Sustain Transp. 2(3):138–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15568310701517265.

- Bowen EA, Murshid NS. 2016. Trauma-informed social policy: a conceptual framework for policy analysis and advocacy. Am J Public Health. 106(2):223–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302970.

- Carey J, Dubbeling M. 2017. City region food system indicator framework: assessing and planning sustainable city region food systems. Leusden (Netherlands): RUAF Foundation.

- Chaudhary A, Gustafson D, Mathys A. 2018. Multi-indicator sustainability assessment of global food systems. Nat Commun. 9(1):848. eng. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03308-7.

- Chemero A. 2003. An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecological Psychology. 15(2):181–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326969ECO1502_5.

- Chemero A. 2009. Radical embodied cognitive science. Cambridge (USA): MIT Press.

- Cinà G, Khatami F. 2017. Integrating urban agriculture and urban planning in Mashhad, Iran; a short survey of current status and constraints. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. 41(8):921–943. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1323818.

- Cohen M. 2017. A systematic review of urban sustainability assessment literature. Sustainability. 9(11):2048. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112048.

- Corburn J, Karanja I. 2016. Informal settlements and a relational view of health in Nairobi, Kenya: sanitation, gender and dignity. Health Promot Int. 31(2):258–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau100.

- Covarrubias M. 2019. The nexus between water, energy and food in cities: towards conceptualizing socio-material interconnections. Sustainability Science. 14(2):277–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0591-0.

- Dahlberg L, McKee KJ. 2018. Social exclusion and well-being among older adults in rural and urban areas. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 79:176–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.08.007.

- De Cunto A, Tegoni C, Sonnino R, Michel C, Lajili-Djala F. 2017. Food in cities: study on innovation for a sustainable and healthy production, delivery and consumption of food in cities. Brussels (Belgium): European Commission.

- Donald B. 2008. Food systems planning and sustainable cities and regions: the role of the firm in sustainable food capitalism. Reg Stud. 42(9):1251–1262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802360469.

- Dubbeling M, Santini G, Renting H, Taguchi M, Lançon L, Zuluaga J, De Paoli L, Rodriguez A, Andino V. 2017. Assessing and planning sustainable city region food systems: insights from two Latin American cities. Sustainability. 9(8):8. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081455.

- El Bilali H, Callenius C, Strassner C, Probst L. 2019. Food and nutrition security and sustainability transitions in food systems. Food and Energy Security. 8(2):e00154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.154.

- Eme PE, Douwes J, Kim N, Foliaki S, Burlingame B. 2019. Review of methodologies for assessing sustainable diets and potential for development of harmonised indicators. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16(7):1184. eng. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071184.

- European Commission. 2020. The Reference Framework for Sustainable Cities. A European Vision. Towards Green, Inclusive and Attractive Cities. [accessed 2020 27 December]. http://rfsc.eu/.

- Farrier A, Dooris M, Morley A. 2019. Catalysing change? A critical exploration of the impacts of a community food initiative on people, place and prosperity. Landscape and Urban Planning. 192: 103663.

- Fenny AP, Asuman D, Crentsil AO, Odame DNA. 2019. Trends and causes of socioeconomic inequalities in maternal healthcare in Ghana, 2003–2014. Int J Soc Econ. 46(2):288–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-03-2018-0148.

- George AS, Branchini C, Portela A. 2015. Do interventions that promote awareness of rights increase use of maternity care services? A systematic review. PLoS One. 10(10):e0138116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138116.

- Gerometta J, Haussermann H, Longo G. 2005. Social innovation and civil society in urban governance: strategies for an inclusive city. Urban Studies. 42(11):2007–2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500279851.

- Giatti LL, Urbinatti AM, Carvalho CM, Bedran-Martins AM, Santos IPO, Honda SO, Fracalanza AP, Jacobi PR. 2019. Nexus of exclusion and challenges for sustainability and health in an urban periphery in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 35(7):e00007918. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00007918.

- Gliessman S. 2017. Food planning and urban agriculture. 7th aesop sustainable food planning conference, Torino, Italy, october 2015. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. 41(8):885–886. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1343524.

- Gomes SL, Hermans LM. 2018. Institutional function and urbanization in Bangladesh: how peri-urban communities respond to changing environments. Land Use Policy. 79:932–941. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.041.

- GPSC World Bank. 2018. Urban sustainability framework. 1st. Washington (DC): Global Platform for Sustainable Cities. World Bank.

- Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, Drahota A. 2019. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implementation Science. 14(1):57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6.

- Hecht AA, Biehl E, Buzogany S, Neff RA. 2018. Using a trauma-informed policy approach to create a resilient urban food system. Public Health Nutr. 21(10):1961–1970. English. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018000198.

- Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, Welch V. 2020. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Huang L, Wu J, Yan L. 2015. Defining and measuring urban sustainability: a review of indicators. Landsc Ecol. 30(7):1175–1193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0208-2.

- Javanparast S, Windle A, Freeman T, Baum F. 2018. Community health worker programs to improve healthcare access and equity: are they only relevant to low- and middle-income countries? International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 7(10):943–954. doi:https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2018.53.

- Jiao W, Fuller AM, Xu SY, Min QW, Wu MF. 2016. Socio-ecological adaptation of agricultural heritage systems in modern China: three cases in Qingtian county, Zhejiang province. Sustainability. 8(12):1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121260.

- Loh P, Agyeman J. 2019. Urban food sharing and the emerging Boston food solidarity economy. Geoforum. 99:213–222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.08.017.

- Luederitz C, Lang DJ, Von Wehrden H. 2013. A systematic review of guiding principles for sustainable urban neighborhood development. Landsc Urban Plan. 118:40–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.06.002.

- Martin W, Wagner L. 2018. How to grow a city: cultivating an urban agriculture action plan through concept mapping. Agriculture & Food Security. 7(1):1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0186-0.

- Matteucci SD, Totino M, Arístide P. 2016. Ecological and social consequences of the forest transition theory as applied to the argentinean great chaco. Land Use Policy. 51:8–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.10.032.

- Mehdipanah R, Manzano A, Borrell C, Malmusi D, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Greenhalgh J, Muntaner C, Pawson R. 2015. Exploring complex causal pathways between urban renewal, health and health inequality using a theory-driven realist approach. Soc Sci Med. 124:266–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.050.

- Mir G, Karlsen S, Mitullah W, Bhojani U, Uzochukwu B, Okeke C, Mirzoev T, Ebenso B, Dracup N, Dymski G, et al. 2020. Achieving SDG 10: a global review of public service inclusion strategies for ethnic and religious minorities. Geneva (Switzerland): The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD).

- Mirzoev T, Kane S. 2017. What is health systems responsiveness? Review of existing knowledge and proposed conceptual framework. BMJ Global Health. 2(4):e000486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000486.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6(7):e1000097. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.B2535.

- Moragues-Faus A, Carroll B. 2018. Reshaping urban political ecologies: an analysis of policy trajectories to deliver food security. Food Security. 10(6):1337–1351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0855-7.

- Murali M, Cumming C, Feyertag J, Gelb S, Hart T, Khan A, Lucci P 2018. 10 things to know about the impacts of urbanisation: briefing papers. [updated Oct 2018; accessed]. https://www.odi.org/publications/11218-10-things-know-about-impacts-urbanisation.

- Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. 2016. Urban and transport planning, environmental exposures and health-new concepts, methods and tools to improve health in cities. Environmental Health. 15(1):S38.

- O’Donnell P, O’Donovan D, Elmusharaf K. 2018. Measuring social exclusion in healthcare settings: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 17(1):15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0732-1.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. 2016. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 5(1):210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

- Oyuela A, Van Der Valk A. 2017. Collaborative planning via urban agriculture: the case of Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. 41(8):988–1008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1331945.

- Ramirez-Rubio O, Daher C, Fanjul G, Gascon M, Mueller N, Pajin L, Plasencia A, Rojas-Rueda D, Thondoo M, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. 2019. Urban health: an example of a “health in all policies” approach in the context of SDGs implementation. Global Health. 15(1):87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0529-z.

- Rojas A, Valley W, Mansfield B, Orrego E, Chapman GE, Harlap Y. 2011. Toward food system sustainability through school food system change: think&EatGreen@school and the making of a community-university research alliance. Sustainability. 3(5):763–788. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su3050763.

- Rudolph L, Caplan J, Ben-Moshe K, Dillon L. 2013. Health in all policies: a guide for state and local governments. Washington (DC): American Public Health Association.

- Säumel I, Reddy S, Wachtel T. 2019. Edible city solutions—one step further to foster social resilience through enhanced socio-cultural ecosystem services in cities. Sustainability. 11(4):4. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040972.

- Sheikh K, Ranson MK, Gilson L. 2014. Explorations on people centredness in health systems. Health Policy Plan. 29(suppl2):ii1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu082.

- Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M. 2012. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. Journal of Development Effectiveness. 4(3):409–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2012.710641.

- Stoltz J, Schaffer C. 2018. salutogenic affordances and sustainability: multiple benefits with edible forest gardens in urban green spaces. Front Psychol. 9:2344. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02344.

- Turcu C. 2013. Re-thinking sustainability indicators: local perspectives of urban sustainability. J Env Plann Management. 56(5):695–719. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2012.698984.

- UN DESA. 2018. World urbanization prospects: the 2018 revision. Online ed. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. https://population.un.org/WUP/PUBLICATIONS/.

- United Nations. 2016. Leaving no one behind: the imperative of inclusive development. Report on the World Social Situation 2016.

- United Nations. n.d. Take action for the sustainable development goals. United Nations; [ accessed 2020 20 October]. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

- Uzochukwu BS, Okeke CC, Ogwezi J, Emunemu B, Onibon F, Ebenso B, Mirzoev T, Mir G. 2020. Exploring the drivers of ethnic and religious exclusion from public services in Nigeria: implications for sustainable development goal 10. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. (ahead-of-print). doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-02-2020-0036.

- Weiler AM, Hergesheimer C, Brisbois B, Wittman H, Yassi A, Spiegel JM. 2015. Food sovereignty, food security and health equity: a meta-narrative mapping exercise. Health Policy Plan. 30(8):1078–1092. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu109.

- WHO. n.d. Social inclusion and health equity for vulnerable groups. World Health Organization; [ accessed 2020 20 October]. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/social-determinants/activities/social-inclusion-and-health-equity-for-vulnerable-groups.

- WHO, UN-Habitat. 2016. Global report on urban health: equitable healthier cities for sustainable development. Kobe, Japan and Nairobi, Kenya: World Health Organization, United Nations Human Settlement Programme.

- Wilkins JL. 2005. eating right here: moving from consumer to food citizen. Agric Human Values. 22(3):269–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-005-6042-4.

- Wu JG, Wu T, editors. 2010. The business of sustainability. Vol. II. Great Barrington: Berkshire Publishing. Vol. II.

- Yi KJ, Landais E, Kolahdooz F, Sharma S. 2015. Factors influencing the health and wellness of urban aboriginal youths in Canada: insights of in-service professionals, care providers, and stakeholders. Am J Public Health. 105(5):881–890. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302481.

- Zasada I, Weltin M, Zoll F, Benninger SL. 2020. Home gardening practice in Pune (India), the role of communities, urban environment and the contribution to urban sustainability. Urban Ecosystems. 23(2):403–417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-019-00921-2.

- Zhou M, Tan S, Tao Y, Lu Y, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Yan D. 2017. Neighborhood socioeconomics, food environment and land use determinants of public health: isolating the relative importance for essential policy insights. Land Use Policy. 68:246–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.043.