Abstract

In many coastal areas of Japan, local fishermen manage fish and other marine resources in a sustainable manner. Such areas are referred to as Satoumi. In this study, we focused on Hinase Junior High School in Okayama Prefecture, Japan, which is implementing a proactive marine education program in collaboration with local fishermen to maintain Satoumi. We conducted semi-structured interviews with the students (n = 108; thirty-six students in each grade [seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-graders]) at Hinase Junior High School. Using the grounded theory, we identified students’ perceptions of this program as well as of the sea. The results revealed that the program appears to have changed students’ perceptions, such as recognizing the importance of the sea and eelgrass as well as their behavior such that they no longer throw waste into the sea. The higher the grade level was, the more that students felt close to and were willing to care for the sea. Our study suggests that the program has helped to develop individuals who are knowledgeable about the fishing community of Hinase, fishermen’s roles, and activities that would contribute to biodiversity conservation and who are motivated to conserve Satoumi in the future.

Introduction

Biodiversity conservation in coastal areas and conservation of the coastal and marine environment are designated global goals, such as the Aichi Biodiversity Targets (CBD Citation2010) and Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Citation2015). Japan is a maritime nation that is surrounded by the ocean and has developed throughout history by using marine resources (Makino Citation2011). To achieve sustainable development in this country, it is essential to manage marine resources and coastal areas in a sustainable manner (Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet Citation2013). In many coastal areas of Japan, local fishermen and community residents manage fish and other marine resources in a sustainable manner. Such areas are referred to as Satoumi and are defined as ‘a coastal area where productivity and biodiversity have increased through human interaction’ (Yanagi Citation2010). The Satoumi concept was proposed as an analogy of the Satoyama concept, defined as a mosaic of ecosystems including farmlands, grasslands, woodlands, paddy fields, wetlands, and human settlements, which caught worldwide attention particularly when the Satoyama Initiative was established at UNESCO in 2009 (Cetinkaya Citation2009; IPSI Citation2017). Recently, the concept and definition of Satoumi have become accepted worldwide and are increasingly discussed at international conferences to encourage proper management of the oceans and coastal areas (Matsuda Citation2010; Yanagi Citation2013).

In Japan, local fishing communities have been affected by aging and depopulation. Meanwhile, the number of fishermen has decreased significantly from 238,000 in 2003 to 167,000 in 2015 (Japanese Fisheries Agency Citation2015). Faced with various issues such as the decreasing number of fishermen and increasing marine pollution, the sustainable conservation and management of Satoumi require understanding, support, and active participation of the general public (including local residents) (Tanaka Citation2014; Sakurai et al. Citation2016a; Sakurai, Ota, and Uehara Citation2017). Education is needed to help increase people’s understanding of and interest in the oceans. Article 28 ‘Enhancement of Citizen’s Understanding of the Oceans, etc.’ of the Basic Act on Ocean Policy enforced in 2007 set forth the government’s responsibility to promote academic and social education with regard to the oceans (Ocean Policy Research Institute Citation2010; Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet Citation2013). It is particularly important to offer marine education to children in coastal areas who are likely to be responsible for managing Satoumi in the future (Network for Coexistence with Nature Citation2016); however, in practice, schools do not have enough teachers and educational materials to do so (Sakai Citation2013). This trend is similar all over the world; ocean and aquatic concepts are insufficiently taught and treated in K-12 (from kindergarten to high school) curriculum materials and textbooks, while educational research is rarely conducted to explore students’ understanding of ocean science and/or the effectiveness of marine education (Lambert Citation2005; Tran, Payne, and Whitley Citation2010; Markos et al. Citation2017). To promote marine education, efforts must be made to develop a marine education curriculum, collect information about advanced projects in Japan, and construct a theory about the value and effectiveness of marine education (Research Group for Ocean Industry Citation2011; Sakai Citation2013).

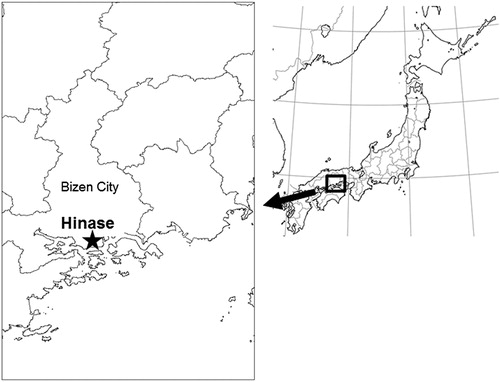

In this study, we focused on Hinase Junior High School (HJHS) in Bizen City () in the Okayama Prefecture, which is implementing a proactive marine education program in collaboration with local fishermen and a non-profit organization. Our research question was ‘how would students’ perceptions about the program and sea differ depending on their grade?’ The goal of this research was to understand how participating in this program would affect students’ perceptions of the sea by interviewing junior high school students. To thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of the program, studies of various stakeholders, including students, teachers, and school administrators, are recommended that would utilize various data collection methods such as interviews, focus groups, surveys, and observation (Rossi, Lipsey, and Freeman Citation2004; Ernst, Monroe, and Simmons Citation2009). To understand the pure impact of the program, it is also recommended to conduct an (quasi-)experimental or longitudinal study (Rossi, Lipsey, and Freeman Citation2004; Ernst, Monroe, and Simmons Citation2009). In this study, considering the limits of time and budget, we focused on conducting one-time interviews with students regarding their perceptions of the sea and the program to understand part of the effectiveness of this program. These findings will enable us to discuss the role and significance of marine education to (i) achieve sustainable conservation and use of the marine environment and (ii) develop human resources to manage the marine environment in the future. It will also provide valuable information to schools across Japan, as well as all over the world, that wish to launch similar initiatives or that are already providing marine education and desire to improve their curricula.

Previous studies on the effectiveness of marine education in primary and secondary education

Few studies on the effectiveness of marine education have been done compared with other areas of environmental education, such as forest education and eco-friendly action (e.g. recycling) in Japan. One such study reviewed the literature regarding nature experience activities in a waterside environment (Chiashi and Tomago Citation2013). This study verified the influence of activities on participants’ awareness (e.g. passion for living, self-identity, and self-efficacy) and determined the educational effectiveness for people from elementary school students to adults; however, it did not include specific findings on the effectiveness of marine education on junior high school students (Chiashi and Tomago Citation2013). A case study conducted by Tomago (Citation2015) involved developing an ocean literacy questionnaire for children aged 10 to 15 and verified the educational effectiveness of seaside nature experience activities on elementary and junior high school students. The case study showed that the survey provided reliable criteria; the longer the program was, the more the participants’ interest in nature increased (Tomago Citation2015). Hirai (Citation2011) examined the effectiveness of an ocean literacy program on elementary and junior high school students and explained how an experience-based classroom program to learn about the oceans (developed in the U.S.) was also effective in Japan in stimulating interest and deepening knowledge. Meanwhile, Kanzaki and Sasaki (Citation2010) showed the effects of a hydrosphere environmental education program using a flathead mullet (Mugil cephalus). Although these studies have revealed the effectiveness of marine education programs to a certain level, most previous studies (Kanzaki and Sasaki Citation2010; Hirai Citation2011; Tomago Citation2015) were based on a single questionnaire survey with predetermined answer scales to measure effectiveness.

The lack of research on the effectiveness of marine education programs for students as well as the dearth of ocean science topics in K-12 classrooms are mentioned all over the world, including North America (Lambert Citation2005; Plankis and Marrero Citation2010; Tran, Payne, and Whitley Citation2010) and Europe (Markos et al. Citation2017). In North America, ocean literacy, such as knowledge regarding the ocean, the relationship between the ocean and the earth, and organisms in the ocean, has been established as a science education criterion for K-12 (Ocean Literacy Network Citation2015); however, a limited number of studies have been conducted to evaluate how educational programs could contribute to acquiring ocean literacy (Tran, Payne, and Whitley Citation2010; Markos et al. Citation2017). Similar to cases in Japan, most of these studies conducted to evaluate marine education programs were based on a quantitative approach using questionnaire surveys with answers predetermined by surveyors (Guest, Lotze, and Wallace Citation2015; Markos et al. Citation2017). Meanwhile, it should be noted that much of the previous research mentioned above focused on non-formal learning, meaning the programs were not necessarily combined or included in the overall school curriculum. The experience-based marine education program that lasts for three years and is implemented as a formal learning program (program established as part of the school curriculum) may have various educational effects on students. Moreover, the program implemented at HJHS is different from most programs studied in the previous research in terms of students’ continuous commitment to the sea as well as the collaboration with fishermen. Therefore, there are limits in gathering diverse feedback based solely on fixed-format quantitative studies (e.g. questionnaires).

One of very few studies that used both quantitative and qualitative approaches to understand the change in students’ ocean literacy awareness and their behaviors revealed that a program, even as short as one semester, could improve students’ knowledge and intent to change their behaviors (Plankis and Marrero Citation2010). In reality, after taking the course, the Students’ Ocean Literacy, Viewpoints, and Engagement Scores, including their knowledge of and concerns for oceanic environmental problems, increased, while the interviews revealed that certain students expressed their willingness to protect the ocean (Plankis and Marrero Citation2010). However, because this was not a longitudinal study, the long-term impact (such as more than a year) on students’ knowledge and behaviors through a lengthy educational program remains unexplored.

Theoretical background

We used and followed the grounded theory to design and conduct the study. The grounded theory is an approach to collecting initial data without any preconceived category or hypothesis and is useful for interpreting data in their social and cultural context (Grix Citation2002; Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015). The grounded theory is suitable in a situation where little is known about the topic and/or a new outlook is needed to develop ideas (Grix Citation2002). Because students at Hinase Junior High School experience an intensive and continuous experience-based collaborative marine education program, they are expected to have various levels of awareness about the sea (e.g. learning the importance of conserving the sea and marine biodiversity) and local community (e.g. learning about the role of fishermen in managing Satoumi). To understand this variance in students’ perceptions, which is our research goal, we believed that a questionnaire with answers predetermined by surveyors (e.g. agree, disagree) is inappropriate. Instead, we followed the grounded theory process and started by asking general questions to students, which would allow us to develop relevant ideas from the data (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007; Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015). In this sense, our research approach could be categorized as inductive. We tried to draw conclusions based on direct observations of empirical evidence that are not necessarily driven by hypothesis.

Methods

Context of study: marine education program at Hinase Junior High School

In the latter half of the 1800s, it is estimated that 90% of households were engaged in the fishing industry in Hinase Town () in Bizen City in Okayama Prefecture (Tanaka Citation2014). Hinase, a fishing village, was nicknamed ‘Hinase Sengen Ryoshi-machi’ (literally ‘a town of 1,000 fishermen’). In the Seto Inland Sea on which Hinase is located, inflows of industrial and domestic wastewater caused eutrophication in the 1950s, resulting in frequent red tides and a temporary decrease in catches (Yanagi Citation2010). In response, local fishermen took the initiative to conduct a voluntary experiment of sowing seeds of eelgrass (Zostera marina L.), which provides a nursery ground and shelter for fish (Yanagi Citation2013). They started to sow eelgrass seeds in 1985, and the eelgrass beds that had once decreased to 12 ha recovered to 120 ha in 2008, successfully leading to increased catches (Tanaka Citation2014). The fishermen’s initiatives to conserve the coastal areas and to increase productivity and biodiversity, in particular, were heavily evaluated. Today, Hinase is known as a model case and icon of Satoumi (Inoue and NHK Satoumi Interview Group Citation2015; Sakurai et al. Citation2016b; Mizuta and Vlachopoulou Citation2017).

Hinase Junior High School (HJHS), which is the only junior high school in Hinase Town, is located approximately one minute on foot from the coast. Traditionally, the school has offered various classes and activities related to the sea. In the 1930s, the school had long-distance ocean swimming competitions (Personal Communication; Teacher of HJHS), although this is no longer practiced today. In the 2000s, the school started to offer experience-based education program in which students collaborated with fishermen to clean harvested oysters (Crassostrea gigas) (Hinase Junior High School of Bizen City of Okayama Prefecture and Network for Coexistence with Nature Citation2016). In Japan, it is rare for a junior high school to have an experience-based marine education program in collaboration with local fishermen as part of the curriculum (Research Group for Ocean Industry Citation2011). Instead of allowing students to randomly experience sea-related initiatives, the junior high school organized annual marine education classes. The school continued to improve the program to involve students of all grades in the classes. In 2013, the school reformed the program with the concept of New Integrated Studies (the Period for Integrated Studies) introduced by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, in which schools are responsible for determining their own education content. The Period for Integrated Studies aims ‘to enable students to think in their own way about life through cross-synthetic studies and inquiry studies while fostering the qualities and abilities needed to find their own tasks, to learn and think on their own, to make proactive decisions and to solve problems better while at the same time acquiring the habits of studying and thinking and cultivating their commitment to problem solving and inquiry of activities in a proactive, creative and cooperative manner’ (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan Citation2011). As of 2016, the themes and learning contents are clearly defined for each grade at HJHS, and marine education classes are offered throughout the year. The marine education program at HJHS has the following five education targets: (1) To learn about the community: to understand Hinase’s basic industry by experiencing the fishing process; (2) To learn that restoring eelgrass beds helps revitalize the ecosystem as well as the local community, strengthens the future of Hinase, and contributes to the global environment; (3) To learn the importance of work; (4) To develop a sense of attachment and pride in the hometown, and (5) To provide opportunities to communicate with local residents (Hinase Junior High School of Bizen City of Okayama Prefecture and Network for Coexistence with Nature Citation2016; Personal Communication; Teacher of HJHS).

The details of the program are as follows. The goal for seventh grade (the first year of junior high school) is to learn about eelgrass. In April, they attend general presentations about the fishing industry in Hinase that are given by older students (eighth- and ninth-graders). In May, they attach oyster seeds to scallop shells. In June, they collect drifting seaweed (eelgrass). In September, they conduct interviews with local fishermen and fishery science institute staff, etc. In October, they sort and sow eelgrass seeds. In November, they conduct an interim observation of the growth of oysters. In February, they wash, process, and taste the oysters. The eighth-graders’ mission is to promote the significance of eelgrass. In April, they give presentations about the fishing industry in Hinase to seventh-graders. In June, they collect drifting eelgrass, grow eelgrass in water tanks, and observe the growth. In October, they explain to seventh-graders how to sort and sow eelgrass seeds. In February, they compile the results of learning about eelgrass. The ninth-graders’ mission is to analyze the importance of eelgrass and create a vision of the future for Hinase. In May, they visit Okinawa Prefecture, the southern part of Japan, on a school excursion to learn about the marine environment. Then, they collect drifting eelgrass and compile the results of the marine education program.

Study items

In this study, we conducted an interview to understand students’ perceptions of the sea and local community as well as their perceptions about the marine education program. In addition, we tried to understand how students’ perceptions would differ depending on their grade, which could imply differences based on the lengths of time they experienced the program. We used semi-structured interview techniques (Barriball and While Citation1994; Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015) and prepared certain questions in advance; however, in principle, we asked students to talk freely as much as they wanted. Based on the grounded theory, we believed that a qualitative technique would suit the objective of this research and asked students to express their subjective views in their own words (Tani and Yamamoto Citation2011; Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015). We asked general questions such as ‘what are features of Hinase’s sea?’ to understand their perceptions of the sea (detailed information for each item is shown in ). We understand that cognitive factors could be classified and categorized into various areas, such as attitudes, values, beliefs, and behavioral intentions in the social psychological field. However, narrowing or classifying students’ potential responses into these cognitive factors before the interview could limit our ability to understand students’ variances in their perceptions. For example, for perceptions of the sea, students’ answers could concern their beliefs (e.g. what they believe about the sea), attitudes (e.g. whether they like or dislike the sea), or behavioral intentions (e.g. whether they want to participate in conservation activities) or other. Following the grounded theory approach, we tried to avoid starting the interview with specific assumptions (such as students’ answers being categorized into specific attitudes and/or beliefs). Our aim was to extract different views. In addition, students could discuss biological, social, cultural, or any other aspects of the sea, and we let the students talk freely. Since we did not differentiate attitudes or beliefs beforehand, we used the word ‘perception’ to collect all types of information. On the other hand, in the Discussion part of this paper, we elaborated on how students’ responses could be connected, such as knowledge and/or behavioral intentions.

Table 1. Question items.

The semi-structured interview allowed us to obtain valid and reliable data by clarifying unclear words and gathering more information, if necessary, during the group interview (Barriball and While Citation1994; Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015).

We conducted the group interview after school. Students were divided into 12 groups (each group consisting of three students) for each grade (seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-graders) (). We took approximately 20 min to interview each group. In 2016, we interviewed 12 groups of seventh-graders and 12 groups of eighth-graders on April 20 and 12 groups of ninth-graders on April 27. In total, we interviewed 108 students (36 seventh-graders, 36 eighth-graders, and 36 ninth-graders), which was more than half the total number of students (195) at HJHS. We asked the school staff to select students who were available after school on these days. We aimed to understand the long-term impact of the marine education program of HSHS by categorizing and comparing students by grade, speculating that their perceptions and motivation to engage in marine conservation could be different because of the duration of the education program they received (their grade level). We understand that this cross-age study could not be regarded as a longitudinal study. The cross-age study describes the characteristics that exist in each group at one specific point in time and does not provide the same data as a 3-year longitudinal study nor identify the relationship between the results observed (e.g. the differences in perceptions of the sea between seventh-graders and ninth-graders does not necessary mean that seventh-grader perceptions will change in such ways after two years).

Table 2. Number of students in groups interviewed in each grade.

Before this study, the authors participated in the marine education program (e.g. collecting drifting eelgrass) at HJHS for one year in 2015 and observed the students’ reaction, and we conducted interviews with teachers at HSHS and local fishermen to understand the contents and goals of these activities. While we understand that standardized questionnaire items, such as the Ocean Literacy questionnaire for 10–15-year-old children (Tomago Citation2015) and Students’ Ocean Literacy Viewpoints and Engagement (SOLVE; Plankis and Marrero Citation2010), exist and were tested in previous studies – because our goal was to collect various opinions and feedback from students and not to simply measure certain fixed items – we prepared open-ended questions. Open-ended questions were designed based on observations of the marine education program, interviews with teachers at the junior high school and local fishermen. In March 2016 (one month before the study was conducted), one of the authors (Sakurai, R) conducted a pilot test with 15 students (eighth- and ninth-graders) at HJHS to make sure that these question items were valid for the purposes of our study and that the students understood the meaning of each question.

Based on the result of this pilot test, we developed eight questions for students of all grades, including students’ perceptions of Hinase’s sea and the relationship between the sea and their lives. For eighth- and ninth-graders, we asked two additional questions regarding their perceptions of the marine education program at the school. In this paper, we report the results for six questions () that are closely related to the effectiveness of the marine education program. For example, while we asked students the names of species that live in Hinase’s sea in the interview – since the marine education program did not specifically teach students about each species in detail – we judged this question was inappropriate for this paper. It should be noted that not all students responded to every question because we used a technique to allow students to talk freely. Therefore, the total number of responses does not match the number of students surveyed. We recorded interviews so that we could check the nuances of interactions between respondents and interviewers and validate the completeness of the information collected. In summarizing the results, we indicated students’ responses by grade in the tables. For those responses that several students mentioned, we categorized them into keywords. To objectively categorize the keywords for students’ responses, once one of the authors coded the results, the two other co-researchers (co-authors) checked the responses and categories to make sure all agreed with the coding. Tables are shown with these coded keywords in the left column; those with the highest frequencies are shown at the top of the table, while those with lower frequencies are shown in the bottom. We showed keywords that were mentioned by at least two students in the same grade in the tables. While we collected data based on a qualitative interview, allowing students to answer freely on the topic, we analyzed the data based on the frequencies of keywords. In this sense, our research utilized a mixture of qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Results

Regarding the features of Hinase, the largest number of seventh-graders mentioned nature (e.g. the sea and mountains), which was followed by the number of students who mentioned oysters. The largest number of eighth-graders mentioned oysters or oyster okonomiyaki (local dish). Most of them (10 students) responded that oysters are tasty. Although many seventh-graders mentioned oysters, only one student responded that oysters are tasty based on experience. The largest number of ninth-graders mentioned abundance, as did seventh-graders. While many seventh-graders mentioned only the sea and mountains, many ninth-graders discussed the relationship between nature and people (i.e. a place where people live in harmony with the sea). Many ninth-graders also mentioned that people in the community are kind. Two ninth-graders responded, although the frequencies are lower than for other responses, that Hinase is a unique community that offers a marine education program as part of the school curriculum ().

Table 3. What are the features of Hinase?

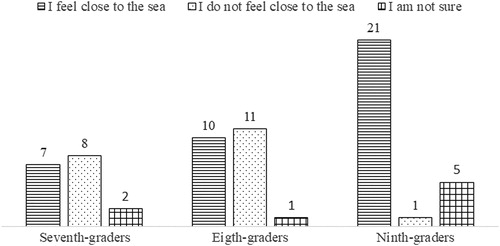

As to whether they feel close to the sea, the number of seventh- and eighth-graders who felt close to the sea was almost the same as those who did not. Most ninth-graders responded that they felt close to the sea; very few students responded that they did not. Regarding perceptions of the sea, the largest number of seventh-graders responded that it is dirty (with floating debris, etc.). The largest number of eighth-graders mentioned eelgrass, followed by the number of students who responded that the sea is inhabited by various fish. Many ninth-graders responded that the sea is dirty, as did the seventh-graders. Many ninth-graders mentioned activities to restore eelgrass beds as well. ( and )

Table 4. What are the features of Hinase’s sea? (Responses of students in multi-grades gave).

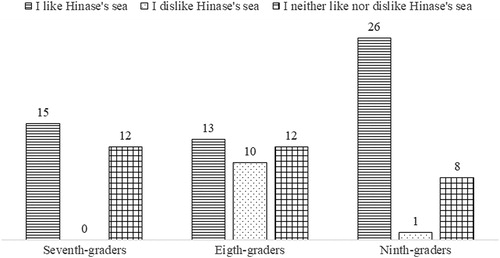

The number of seventh- and eighth-graders who responded that they liked the sea was almost equal to the number who responded that they neither liked nor disliked it. Meanwhile, most ninth-graders responded that they like the sea; the number was twice that of eighth-graders who responded that they like the sea. Many of the eighth- and ninth-graders like the sea because they enjoy swimming and fishing. Several ninth-graders responded, although the frequencies of the words used are lower than other words, that they can work on marine activities through Integrated Studies (at HJHS) and that the sea invigorates Hinase; no seventh- or eighth-graders responded in this manner. Meanwhile, many eighth-graders responded that they disliked the sea because it is dirty or smells bad. Many of the seventh-graders who neither liked nor disliked the sea responded that they do not visit the sea or that the sea is irrelevant. Few eighth- and ninth-graders responded in this manner ( and ).

Table 5. Reasons that students like or dislike Hinase’s sea.

Regarding the perception of fishermen, the largest number of eighth- and ninth-graders mentioned the physical features of the fishermen (e.g. strong and muscular), while the largest number of seventh-graders mentioned the fishermen’s role (e.g. catch fish and oysters). Many eighth- and ninth-graders mentioned the psychological features of fishermen (e.g. they are kind [in helping to learn], they are communicative and sociable), while only a limited number of seventh-graders mentioned this. Similarly, several eighth- and ninth-graders showed empathy for fishermen (e.g. the work seems to be hard, concern about their health) while only few seventh-graders responded so. ()

Table 6. What is your perception of fishermen? (Categorized by the fishermen’s role, physical features, psychological features, and empathy toward the fishermen).

Regarding the perception of the program, the largest number of eighth- and ninth-graders responded that the work was hard and physically demanding, which was followed by (i) the number of eighth-graders who responded that they recognized the hard work and difficulties of fishermen, and (ii) the number of ninth-graders who responded that they had fun. In each grade, several students responded that they felt a sense of accomplishment. ()

Table 7. What is your perception of the marine education program?.

Finally, regarding the changes in the students’ perceptions of the sea after attending the marine education classes at the school, the largest number of ninth-graders as well as a certain number of eighth-graders responded that they had become motivated to keep the sea clean and restore the environment. Many eighth-graders responded that they learned about the effectiveness of eelgrass and became interested in the sea. Many ninth-graders responded that they no longer throw waste into the sea. ()

Table 8. How did your perception of the sea change after attending the marine education program at the school?.

Discussion

Impacts of the program from the perspective of environmental education

This study showed that junior high school students in higher grades who received a longer marine education had more knowledge about marine biodiversity and ecosystem (such as how the restoration of eelgrass beds contributes to the ecosystem) and the relationship between people and the sea. The survey was conducted in April, when seventh-graders had spent only about three weeks at school after admission; they had not yet received marine education, and so their perceptions of Hinase were mostly vague (e.g. the sea, nature, and oysters).

While the number of seventh and eighth grade students who felt close to the sea was similar (n = 7 for seventh-graders and n = 10 for eighth-graders), a majority of ninth-graders (n = 21) responded that they felt close to the sea probably because they had continuously participated in the marine education program and engaged in conservation and management of the sea. Ninth-graders could explain the relationship between people and the sea in detail (e.g. Hinase as a place where the community is closely related to and live in harmony with the sea). Meanwhile, seven eighth-graders mentioned that activities to restore eelgrass beds occur in the area when explaining the feature of Hinase’s sea, which was not mentioned by any of the seventh-graders. In addition, students in higher grades were able to discuss the sea and Hinase based on their experiences (e.g. oysters are tasty). This implies that students’ affinity for Hinase’s sea increased from experiencing various activities in the marine education program.

As for the perception of fishermen, twelve eighth-graders and fifteen ninth-graders mentioned the psychological features of fishermen, such as how fishermen are kind in helping the students learn more, which could be explained by the fact that they had often communicated with fishermen through the marine education program for two years. Seventh-graders had not attended the marine education program and had few opportunities to directly communicate with the fishermen, which may be why fewer students in seventh grade mentioned the psychological features of fishermen. Communication may help students deepen their understanding of fishermen’s personalities.

The marine education appears to have changed perceptions (e.g. recognition of the importance of the sea and eelgrass) of several students (n = 9 for eighth-graders, n = 5 for ninth-graders) as well as their motivation to keep the sea clean and restore the environment (n = 6 for eighth-graders and n = 17 for ninth-graders). Nine ninth-graders also mentioned that they changed their behaviors (no longer throw waste into the sea). The students’ statements show that several years of continuous involvement in managing the local sea and communicating with people helped change their perceptions.

Impact of the program beyond traditional environmental education scope

By looking at the students’ responses, it seems that the five education targets of the marine education program at HJHS have been met to some extent. Several students (as explained below) provided answers, as shown in Tables and , relating to the five educational targets of the marine education program at HJHS.

To learn about the community: ‘I was glad to learn that these activities help clean the sea and benefit Hinase’ (Four students provided comments related to this target).

To learn that activities to restore eelgrass beds help revitalize the ecosystem: ‘I have learned about the sea, including the effectiveness of eelgrass, and recognized its importance and issues’ (Fourteen students provided comments related to this target).

To learn the importance of work: ‘I now feel grateful to fishermen’ (Ten students provided comments related to this target).

To develop a sense of attachment and pride in their hometown: ‘I have become motivated to keep the sea clean and restore the environment’ (Twenty-three students provided comments related to this target).

To provide opportunities to communicate with local people: ‘The activities helped increase communication with fishermen and other people in the community’ (Two students provided comments related to this target).

Meanwhile, students’ responses such as ‘It is my turn to protect the sea environment’ suggests that the marine education program at the school has increased students’ sense of ownership of the sea and potentially helped develop human resources who will continuously work on the sea in the future. This corresponds to the findings of recent studies regarding residents’ attitudes and behavioral intentions for coastal conservation; increasing people’s sense of attachment to the coast could increase their willingness to conserve the area for the future generations (Kudryavtsev, Stedman, and Krasny Citation2012; Sakurai et al. Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Sakurai, Ota, and Uehara Citation2017).

Satoumi is defined as a coastal area where the rich marine environment has been restored through human interaction and the biological aspects of ecological services have often been frequently discussed (Yanagi Citation2010). However, our study implies that Satoumi offers not only biological parts but also the cultural and non-material benefits of ecosystem services as well, such as providing a space for interaction both between people and nature and among people. Satoumi provides opportunities where various stakeholders interact, and this is one of the important processes for achieving Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), an education that leads to community building (Furihata and Takahashi Citation2009; The Japanese Society of Environment Education Citation2014). It is believed that the marine education program at HJHS creates and uses opportunities where various people collaborate and help develop human resources who are knowledgeable about the fishing community of Hinase, fishermen’s roles, and activities that would contribute to biodiversity conservation and aim to conserve Satoumi in the future.

Potential of ‘Satoumi Education’ for sustainable coastal community development

Our interviews and analysis revealed the various perceptions mentioned by students and some characteristics and tendencies based on their grades (different years of experiencing marine education program).

Of the few evaluation studies on marine education, the majority attempted to understand the effects of programs on participants’ perceptions of the ocean using a predetermined questionnaire (Lambert Citation2005; Guest, Lotze, and Wallace Citation2015; Markos et al. Citation2017); however, it should be noted that as long as researchers use those fixed items/criteria, it is difficult to determine the potential and extent of the impact of such marine education programs. For example, our study found that students felt appreciation for fishermen and recognized their connection with nature and people in the region after the program; however, such factors have not been presented as evaluation criteria in any of the previous studies regarding ocean literacy to the best of the authors’ knowledge.

For an environmental education program to be effective in raising students’ awareness of a local marine ecosystem, deepening their understanding of their relationship with nature and people, and potentially developing human resources who will continue to manage the natural environment in the future, the program needs to be designed and implemented based on the cultural and traditional setting of the area (Kudryavtsev, Stedman, and Krasny Citation2012; Sakurai, Ota, and Uehara Citation2017). Interactions between local fishermen and the sea, such as their increasing both biodiversity and productivity and creating a Satoumi landscape through collecting and sowing eelgrass seeds, could be unique to Japan and perhaps to the Hinase region (Mizuta and Vlachopoulou Citation2017). The marine education program at HJHS was effective in changing students’ perceptions of the sea through learning about the ecological and social aspects of the local environment, and the historically specific features of Satoumi management. Thus, we believe that the program implemented at HJHS could be called ‘Satoumi Education’, different from ocean literacy education, which mainly focuses on (or focused on, according to previous studies [Cummins and Snievely Citation2000; Plankis and Marrero Citation2010; Markos et al. Citation2017]) increasing students’ knowledge of ecological services/ecological aspects of the marine environment. Thus, the Satoumi Education program implemented at HJHS could serve as a model case for (i) schools in coastal areas across Japan and (ii) sustainable management of coastal areas where people coexist with nature.

In this study, we were not able to study the thorough effectiveness of the marine education program, which requires researchers to conduct a study with not only students but also teachers and other stakeholders. Such a study should utilize various research designs, including a pre-post study with the same students or an experimental study with control and treatment groups. Our study was rather to explore students’ perceptions of the sea and the program through the cross-grade comparison. To evaluate the effectiveness of these programs that are unique to the traditional local landscape, aiming not only to increase students’ learning but also to achieve sustainable coastal community development, a new set of evaluation criteria specifically measuring Satoumi Education should be developed, while an approach such as the experimental design study could be adopted to reveal the pure impact of the program.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the teachers and staff at Hinase Junior High School, particularly T. Fujita and Y. Oda, for their support for this research. We also thank K. Nakagami and T. Yanagi for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ryo Sakurai

Ryo Sakurai is an associate professor at the College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University. His research interests are evaluations of environmental education programs, social psychology, and human dimensions of wildlife management and coastal management.

Takuro Uehara

Takuro Uehara is an associate professor at the College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University. His research interests are ecological economics and system dynamics.

Taisuke Yoshioka

Taisuke Yoshioka is a senior researcher at the Research Organization of Open Innovation and Collaboration, Ritsumeikan University. His research interests are social dimensions of transportation and coastal management.

References

- Barriball, K. L., and A. While. 1994. “Collecting Data Using a Semi-Structured Interview: A Discussion Paper.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 19: 328–335.

- Brinkmann, S., and S. Kvale. 2015. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- CBD. 2010. “Aichi Biodiversity Targets.” Accessed July 5, 2016. https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/

- Cetinkaya, G. 2009. “Challenges for the Maintenance of Traditional Knowledge in the Satoyama and Satoumi Ecosystems, Noto Peninsula, Japan.” Human Ecology Review 16 (1): 27–40.

- Chiashi, K., and H. Tomago. 2013. “Nature Experience Activities in the Waterside Environment and Educational Effects of Marine Education.” (in Japanese). Accessed February 12, 2017. http://www.ymfs.jp/project/culture/survey/002/pdf/ymfs-report_20130329.pdf

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2007. Research Methods in Education. 6th ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cummins, S., and G. Snievely. 2000. “The Effect of Instruction on Children’s Knowledge of Marine Ecology, Attitudes toward the Ocean and Stances toward Marine Resource Issues.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 5: 305–324.

- Ernst, J. A., M. C. Monroe, and B. Simmons. 2009. Evaluating Your Environmental Education Programs. Washington, D C: North American Association for Environmental Education.

- Fisheries Agency. 2015. “Chapter 2: Trend of Fishery after 2014 in Japan.” (in Japanese). Accessed July 21, 2016. http://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/j/kikaku/wpaper/H27/pdf/27suisan-gaiyou-2.pdf

- Furihata, S., and M. Takahashi. 2009. Introduction to Current Environmental Education. Tokyo: Tsukuba Shobo . (in Japanese).

- Grix, J. 2002. The Foundations of Research. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guest, H., H. K. Lotze, and D. Wallace. 2015. “Youth and the Sea: Ocean Literacy in Nova Scotia, Canada.” Marine Policy 58: 98–107.

- Hirai, K. 2011. “Development of Ocean Literacy Program and Its Evaluation.” Memoires of Study in Aquatic and Marine Environmental Education 4 (1): 128–164 . (in Japanese).

- Inoue, K., and NHK Satoumi Interview Group. 2015. Satoumi Capitalism: Japanese Society Driven by the Principle of Living in Harmony. Tokyo: Kadokawa Shinsho . (in Japanese).

- IPSI. 2017. “Satoyama Initiative.” Accessed May 10, 2017. http://satoyama-initiative.org/

- Kanzaki, K., and T. Sasaki. 2010. “Influence of the Hydrosphere Environmental Education Program Using Flathead Mullet (Mugil Cephalus) on Participating Children.” Journal of Hydrosphere Environmental Education 3: 1–30 . (in Japanese).

- Kudryavtsev, A., R. C. Stedman, and M. E. Krasny. 2012. “Sense of Place in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 18 (2): 229–250.

- Lambert, J. 2005. “Students' Conceptual Understandings of Science after Participating in a High School Marine Science Course.” Journal of Geoscience Education 53 (5): 531–539.

- Makino, M. 2011. Fisheries Management in Japan: Its Institutional Features and Case Studies. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Markos, A., T. Boubonari, A. Mogias, and T. Kevrekidis. 2017. “Measuring Ocean Literacy in Pre-Service Teachers: Psychometric Properties of the Greek Version of the Survey of Ocean Literacy and Experience (SOLE).” Environmental Education Research 23 (2): 231–251.

- Matsuda, O. 2010. “Chapter 8 Disseminating Satoumi to the World.” In New Usage of Coastal Areas as Satoumi, edited by Yamamoto, T., 102–118. Tokyo: Kouseisha Kouseikaku Co., Ltd. ( in Japanese).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. 2011. “Chapter 5: The Period for Integrated Studies.” Accessed February 5, 2017. http://www.mext.go.jp/component/english/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2011/03/17/1303755_012.pdf

- Mizuta, D. D., and E. I. Vlachopoulou. 2017. “Satoumi Concept Illustrated by Sustainable Bottom-up Initiatives of Japanese Fisheries Cooperative Associations.” Marine Policy 78: 143–149.

- Network for Coexistence with Nature. 2016. School of Forests and Oceans: The First Step for Active Learning. Tokyo: Nihon Bunkyo Shuppan . (in Japanese).

- Ocean Literacy Network. 2015. “Principles and the Scope and Sequence.” Accessed January 30, 2017. http://oceanliteracy.wp2.coexploration.org/ocean-literacy-framework/principles-and-concepts/

- Ocean Policy Research Institute. 2010. Grand Design for Marine Education in the 21st Century (Junior High School Edition): Curricula and Unit Plans regarding Marine Education. Tokyo: Ocean Policy Research Institute . (in Japanese).

- Plankis, B. J., and M. E. Marrero. 2010. “Recent Ocean Literacy Research in United States Public Schools: Results and Implication.” International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education 1 (1): 22–51.

- Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. 2013. “Basic Plan on Ocean Policy.” Accessed August 9, 2016. http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/kaiyou/kihonkeikaku/130426kihonkeikaku_je.pdf

- Research Group for Ocean Industry. 2011. “Report regarding the Survey on the Current Status of Marine Education.” (in Japanese). Accessed February 5, 2017. http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/kaiyou/chousa/kaiyoukyouiku.pdf

- Rossi, P. H., M. W. Lipsey, and H. E. Freeman. 2004. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach. 7th ed. California: Sage.

- Sakai, E. 2013. “A Scenario for Promoting Ocean Education in the Japanese School System: Targeting the Next National Curriculum Reform.” Maritime Traffic Study 62: 3–12 . (in Japanese).

- Sakurai, R., T. Ota, and T. Uehara. 2017. “Sense of Place and Attitudes towards Future Generations for Conservation of Coastal Areas in the Satoumi of Japan.” Biological Conservation 209: 332–340.

- Sakurai, R., T. Ota, T. Uehara, and K. Nakagami. 2016a. “Factors Affecting Residents’ Behavioral Intentions for Coastal Conservation: Case Study at Shizugawa Bay, Miyagi, Japan.” Marine Policy 67: 1–9.

- Sakurai, R., T. Ota, T. Uehara, and K. Nakagami. 2016b. “Public Perceptions of a Coastal Area among Residents around Hinase Town of Okayama Prefecture: Analysis Based on Location of Residence.” People and Environment 42 (18): 26 . (in Japanese).

- Tanaka, T. 2014. “Satoumi with Eelgrass and Oyster: Hinase Town of Okayama Prefecture.” Journal of Survey Research and Information ECPR 1: 21–26 . (in Japanese).

- Tani, T., and T. Yamamoto. 2011. Easy-to-Understand Qualitative Social Surveys. Process ed. Tokyo: Minerva Shobo . (in Japanese).

- The Japanese Society of Environment Education. 2014. Environmental Education and ESD. Tokyo: Toyokan . (in Japanese).

- Tomago, H. 2015. “Effects of Practical Marine Training on Ocean Literacy of Participants. a Doctoral Dissertation Submitted to Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology.” Accessed February 26, 2017. https://oacis.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=repository_action_common_download&item_id=1099&item_no=1&attribute_id=20&file_no=3

- Tran, L. U., D. L. Payne, and L. Whitley. 2010. “Research on Learning and Teaching Ocean and Aquatic Sciences.” National Marine Educators Association Special Report 3: 22–26.

- United Nations. 2015. “Sustainable Development Goals.” Accessed May 10, 2017. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Yanagi, T. 2010. Creation of Satoumi. Tokyo: Kouseisha Kouseikaku Co., Ltd . (in Japanese).

- Yanagi, T. 2013. Japanese Commons in the Coastal Seas: How the Satoumi Concept Harmonizes Human Activity in Coastal Seas with High Productivity and Diversity. Tokyo: Springer Japan.