Abstract

This article introduces key features to the background, themes and implications of three collections available in Environmental Education Research that focus on climate change education and research. The problems and perils of scholarship and inquiry in this area are highlighted by contrasting these with some of the possibilities and potentials from a broad range of studies published in this and related fields of study, for example, in understanding who is doing the teaching and learning in climate change education, and in identifying the conceptual, policy and economic drivers and barriers related to its uptake. Key points for debate and action are identified, including for so-called ‘pyro-pedagogies’ and ‘practice architectures’, and the various philosophical, political and phenomenal aspects of climate change education that are likely to affect its prospects, at this moment and into the immediate future.

The need of the hour

The notion that climate change education is crucial to redirecting teaching and learning in the face of today’s climate emergency is now widely established and accepted (see UNFCCC Citation1992; UNESCO Citation2009, Citation2010; UNESCO and UNFCCC Citation2016).

Yet despite broad agreement among experts, citizens, educationalists and activists about:

its necessity within a suite of prevention, mitigation and adaptation strategies (see Berkhout, Hertin, and Gann Citation2006; Stern Citation2006; Schlesinger et al. Citation2007; Anderson Citation2010; Kagawa and Selby Citation2010; UNESCO and UNEP Citation2011; Jickling Citation2013), and

a need to focus on ensuring strategic (rather than piecemeal) action (IPCC 2014, 95–96, 108, UNFCCC Citation2012; UNESCO Citation2019a),

… there can appear to be little consensus in public, political and academic spheres about:

what should and shouldn’t happen in climate change education, be that day-by-day or over the longer term,

who is responsible for ensuring quality climate change education takes place,

how to bring about change in educators’ practices to ensure climate change education is educational, fit for purpose, and effective,

the intended and unintended outcomes of the currrent provision and reach of climate change education on those involved in it, as well as those beyond it, and

what and how to assess, evaluate and research climate change education

(see Hicks and Bord Citation2001; Schreiner, Henriksen, and Kirkeby Hansen Citation2005; Selby Citation2009; Swim et al. Citation2009; Bangay and Blum Citation2010; CitationTaber and Taylor 2009; Marcinkowski Citation2009; Pruneau, Khattabi, and Demers Citation2010; Anderson Citation2012; Selby and Kagawa Citation2013; Chang Citation2014; Wibeck Citation2014; Shepardson et al. 2017; Young Citation2018; Busch, Henderson, and Stevenson Citation2019; Gleason Citation2019; Krasny and DuBois Citation2019; McKenzie Citation2019, UNESCO Citation2019b; Monroe et al. Citation2019; Reid Citation2019a, UNESCO Citation2019b).

In this issue of Environmental Education Research, we highlight a suite of responses to these challenges from environmental education research and researchers, as well as their colleagues and critics. We start with a broad sketch of climate change education in this essay, highlighting aspects of the contemporary moment, and then introduce some of the key contributions and challenges raised by recent scholarship on environmental, sustainability and climate change education.

Why ‘climate change education’ isn’t simply ‘climate education’

To grasp something of the origins, drivers and dynamics of the situation outlined above, we should identify some of the hard truths about climate change education that must be faced in and beyond 2019.

First, it is now over a quarter of a century after the agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC Citation1992).

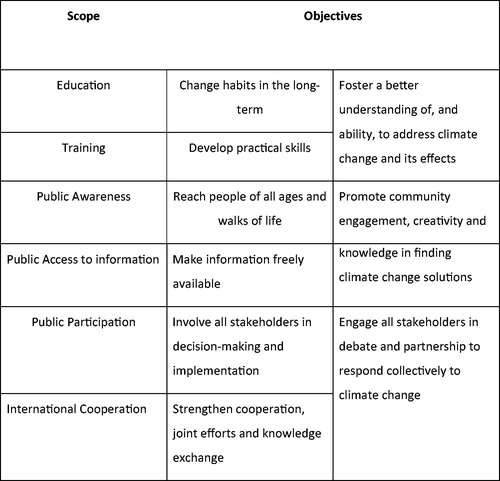

Article 6 of the Convention established the necessity of climate change action in multiple sectors, including education, training and public awareness (UNFCCC Citation1992, p.10). Alongside Articles 4—e.g., in 1.i, to ‘Promote and cooperate in education, training and public awareness related to climate change and encourage the widest participation in this process, including that of non-governmental organizations’—5 (on research and systemic observation) and 6 (on education, public awareness and training, in a.i and a.ii), the UNFCCC prioritised 6 key areas of activity: education, training, public awareness, public access to information, public participation, and international cooperation ().

Figure 1. Action for climate empowerment guidelines—scope and objectives (Source: UNESCO and UNFCCC, 2016, p. 3, based on UNFCCC, 2005, Article 6).

Together, these 6 areas for action would be supported primarily through various levels of government tasked with directing and supporting educational standards and provision, public goods and services in the non-formal and informal education sectors, and last but not least, voluntary action. However, the lack of substantial progress on these tasks and fronts over more than two decades has to be recognised as a key factor in both the frustration felt and deliberations undertaken, which lead to Article 12 of the Paris Accord (UNFCCC Citation2015, 10). Therein, the key need was restated, namely that:

Parties shall cooperate in taking measures, as appropriate, to enhance climate change education, training, public awareness, public participation and public access to information, recognizing the importance of these steps with respect to enhancing actions under this Agreement.

Article 6 of the 1992 Convention was also refocused at Paris, and purposefully so, to stress ‘Action for Climate Empowerment’ (ACE) (UNESCO and UNFCCC Citation2016). Climate change education (CCE) efforts were brought into the spotlight too via the COP meetings through ‘Education Day’, in parallel with those for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For the latter, these included specific attention to Target 13.3, climate action, with its focus on improving education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning, and to a lesser extent, targets and indicators for 4.7 on education for sustainable development, 16 on peace, justice and strong institutions, 12.8 on information provision, and 13.1 on strengthening resilience and adaptive capacities. In addition, we should note a range of wider proposals and programs, which are either related (e.g. a 'Global Action Programme' (GAP) on 'Education for Sustainable Development' (ESD), UNESCO Citation2017a), separate (e.g. ‘Climate Change Education for Sustainable Development’, Mochizuki and Bryan Citation2015) or composite (e.g. ‘Education for Sustainable Development Goals’ (ESDGs), UNESCO Citation2017b) to the above.

As argued in the foreword and introduction to UNESCO’s (2017b, 1, 7) ‘Education for Sustainable Development Goals’:

The momentum for ESD has never been stronger. Global issues—such as climate change—urgently require a shift in our lifestyles and a transformation of the way we think and act. To achieve this change, we need new skills, values and attitudes that lead to more sustainable societies.

ESD does not only integrate contents such as climate change, poverty and sustainable consumption into the curriculum; it also creates interactive, learner-centred teaching and learning settings.

Indeed, in supporting the promotion of the ACE Guidelines at the COP23 meeting in Bonn, and in order to signal how ‘Climate change is a thematic focus across all five Priority Action Areas of the Global Action Programme (GAP) on ESD,’ under the banner of ‘Changing minds, not the climate: the role of education,’ UNESCO (Citation2017c, unpaginated), stated:

Education is a key vector to prepare societies for global changes. It plays a critical role in achieving sustainable development goals and putting into practice a global agreement on climate change.

Education plays a paramount role in raising awareness and promoting behavioural change for climate change mitigation and adaption. It helps increase the climate change mitigation and adaptation capacity of communities by enabling individuals to make informed decisions.

The heads of UNESCO and UNFCCC agree that education provides the skills people need to thrive in the new sustainable economy, working in areas such as renewable energy, smart agriculture, forest rehabilitation, the design of resource-efficient cities, and sound management of healthy ecosystems. Perhaps most important, education can bring about a fundamental shift in how we think, act, and discharge our responsibilities toward one another and the planet. [emphasis added]

Yet, when progress is reviewed at events such as the UN’s ACE Dialogues (e.g. McKenzie Citation2019) or is highlighted and scrutinized in evaluations of the Doha Work Programme on Article 6 (e.g. https://unfccc.int/event/7th-dialogue-on-action-for-climate-empowerment), it is clear that provision of CCE nationally, regionally and internationally is found wanting in many regards.

First, it remains far from being a requirement or capability of core educational institutions or professionals, starting with those that claim their work is aligned with advancing this particular work or that of the Sustainable Development Goals more broadly, let alone every institution or professional living in and through ‘climate chaos’ (see also Hicks and Bord Citation2001; Jickling Citation2013; Laessøe and Mochizuki Citation2015; Wynes and Nicholas Citation2017; Verlie Citation2019).

Equally, we can recognise the vast majority of beginning to experienced educators are (still) not required to engage in professional preparation or learning related to CCE (e.g. Berger, Gerum, and Moon Citation2015; UNFCCC Citation2018; UNESCO Citation2019; Benavot et al. Citation2019). Compounding this, the focus of most educators’ professional accreditation, development, evaluation, and research and development over recent decades has remained on other matters, the legacy and promulgation of which, it has been widely argued, continues to contribute to the deepening climate crisis, as do the funding and policy priorities of many education ministries, providers, practitioners, and research associations (Fortner Citation2001; Kagawa and Selby Citation2010; Hamilton Citation2011; Blum et al. Citation2013; Branch Citation2018; Busch, Henderson, and Stevenson Citation2019; cf. OECD Citation2019).

In the meantime, public debate about climate change action intensifies, and paradoxes persist, including about the roles of education and educators in contributing to both the problems and any solutions to the climate crisis. These challenges are familiar to environmental educationalists, educators and researchers, the crux of which is often framed as a reflexive question: namely, whether education is the best means to address socio-ecological issues, including when local and national sectors and provisions are so often ill-thought, underfunded, overstretched, and undervalued already (Jensen and Schnack Citation2006; Stevenson Citation2007; Hayden et al. Citation2011; Bieler et al. Citation2018)?

For some, such considerations will essentially boil down to hard choices, such as, on what education policymakers (still/should) have to put on the back burner, so to speak, if the energies and passion of educators and learners are to be focused on the task at hand (Moser and Dilling Citation2004; Laessøe et al. Citation2009; Stevenson et al. Citation2014; Krasny and DuBois Citation2019)? For others however, such consultations and their considerations risk wasting yet more time: aren’t they also/really a part of a heady mix of displacement activities, double think and bad faith (Foster Citation2008; Citation2015; Selby and Kagawa Citation2010; Waldron et al. Citation2019), relaying a broad-based and deep-seated reluctance to unlearn and relearn the purposes and practices of education in the face of a climate crisis (Lotz-Sisitka Citation2010; Marcinkowski Citation2009; Shepardson et al. Citation2012)? In other words, we have to ask, what have we come to believe, experience and expect of education, while global warming has advanced—or rather, is it ultimately a question of a change of many hearts, minds and actions that is required, and urgently so? Surely it is time for radical change, some argue, not accommodation and certainly not ‘business-as-usual’ either in or beyond these times (McCaffrey and Buhr Citation2008; Selby and Kagawa Citation2013; Huckle and Wals Citation2015)? While put very differently, is an end-in-view actually that of working towards ensuring we can imagine and experience a time when CCE is no longer necessary, for young to old, apart from as a form of history?

Of ‘pyropedagogies’ and ‘practice architectures’

The trope, ‘Our House is on Fire’, is regularly invoked by Greta Thunberg, the Swedish teenager and public face of the School Strike for Climate [Skolstrejk för klimatet] movement since August 2018. The slogan signals a vivid sense of both the necessity for action and attributions of responsibility for the current predicament. It can also be used to raise direct questions about the adequacy of strategies of action and inaction, including in education about climate change, be that intra-generationally or inter-generationally framed.

On 25 January 2019, at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, Thunberg (Citation2019, 24) ended her speech by saying:

Adults keep saying we owe it to the young people to give them hope.

But I don't want your hope.

I don't want you to be hopeful.

I want you to panic.

I want you to feel the fear I feel every day.

And then I want you to act.

I want you to act as if you would in a crisis.

I want you to act as if the house was on fire.

Because it is.

At the EU Parliament, 16 April 2019, Thunberg reworked the metaphor to embrace the need for concerted and collective action, suggesting:

Our house is falling apart. The future, as well as what we have achieved in the past, is literally in your hands now. But it's still not too late to act. It will take a far-reaching vision. It will take courage. It will take a fierce determination to act now to lay the foundations where we may not know all the details about how to shape the ceiling. In other words, it will take ‘cathedral thinking’.

In invoking both burning and building, there is some pertinence to the ironies of both the timing and allusions in this reasoning for education, and climate change. Note, for example, that the day before this speech, a catastrophic fire engulfed Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral. In the immediate aftermath, many rallied to promise support to redress the loss of an architectural feat and (inter)national treasure. A building founded and renewed over centuries for a clear purpose, Notre Dame has supported a community and remained a focal point dear to the hearts, lives and imaginations of many over generations, near and far. Billionaires were quick to make huge pledges to help fund any rebuilding, while the Catholic Church, individuals and various groups in and beyond France lined up to make other donations and offers of support, in preparation for the government’s decisions about what to fund and prioritise. At least in theory, and at time of writing, this particular feature and symbol of Paris now has a ‘pledge pot’ currently in excess of 1 billion US$—even if some dispute whether this is enough to fund a rebuild, where monies directed at ‘Paris’ should really be spent, and whether the money will actually materialise (Cerullo Citation2019).

The analogy, of course, is crude. But it serves to ask will similar degrees, orders and pathways of commitment happen for climate change education, as a key feature of ‘climate action’ or ‘action for climate empowerment’? In fact, to a planet some would claim has always required an environmental education for living justly and sustainably in ‘our common home’ (Pope Francis, Citation2015), the case should be clear about educators ensuring a broader and deeper sense of relationship with oikos (cf. Pachamama), in ways that supplant the focus and metrics of economic thinking in the education sector to those capable of responding to the current climate crisis too (see Pope Francis, Citation2015, 209–215, on ‘educating for the covenant between humanity and the environment’). In fact, in June 2019, Pope Francis addressed the leaders of some of world’s biggest multinational fossil fuel companies in the Vatican (Harvey and Ambrose Citation2019, unpaginated), ... and another irony emerged?

Pope Francis has declared a global climate emergency, warning of the dangers of global heating and that a failure to act urgently to reduce greenhouse gases would be ‘a brutal act of injustice toward the poor and future generations’.

‘Future generations stand to inherit a greatly spoiled world. Our children and grandchildren should not have to pay the cost of our generation’s irresponsibility’, he said, in his strongest and most direct intervention yet on the climate crisis. Indeed, as is becoming increasingly clear, young people are calling for a change.

As noted in this newspaper report, there were again, ‘no pledges to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, and [they] set no timetable for action’ (ibid.).

Intergenerational ethics and education: necessary but insufficient?

Such gaps and disconnects between ethics, awareness, intention, beliefs, commitments and action, also call into question whether any sense of ‘progress’ is unduly influenced by newsworthiness and pledges (Corner and Randall Citation2011; Jickling Citation2013), be those of the devout, billionaires or for that matter, national non-binding commitments for climate change education during the COP meeting process. The situation is also a familiar story for environmental educators and education researchers too, e.g., on gaps and disconnects between environmentally-related emotions, beliefs, meanings and convictions (Maiteny Citation2002), or attitudes and behaviours (Kollmuss and Agyeman Citation2002; Marcinkowski and Reid Citation2019). So, in this and related collections, we include examples of how these may be understood, limited and/or reconciled, and whether action through education might sometimes be better approached through other means (e.g., Wibeck Citation2014; Stevenson, Peterson, and Bondell Citation2019; Topp, Thai, and Hryciw Citation2019 Dillon Citation2019). While given the rhetorics associated with Thunberg and Francis, this might also include probing concomitant initiatives and effects that develop and articulate both a hope and a vision for how climate change and education can be brought into productive alignment, such that actions do speak louder than words (e.g., Fortner et al. Citation2000; Nisbet Citation2009; Ojala Citation2012a).

Three collections

Working backwards, in this issue, we explore some of the possibilities and potentials, as well as problems and perils that researchers have raised about this in Environmental Education Research. While preceding this collection are two other distinct, but related collections of research articles published over recent years, many of which illustrate some of the ‘edifices of education’ that may need to burn to the ground before more sustainable ‘practice architectures’ can emerge (Kemmis and Mutton Citation2012)?

In brief, the first of our collections was a Virtual Special Issue on climate change and education in 2017, drawing on key and (then) forthcoming research articles addressing aspects of their intersection in the journal, since 2010 (Box 1). The Virtual Special Issue was launched on Education Day (16 November) at the UN climate change conference in Bonn (COP23, 6–17 November 2017), by Alan Reid (Editor) and Marcia McKenzie (Associate Editor) from the journal. Met with healthy levels of interest in person and online in the studies and implications of the work, our response at the Journal was to curate two follow-up collections in the journal, both published in Volume 25. Some (marked with *) from the Virtual Special Issue, are included in this issue, whereas others which were either in review or subsequently accepted, can be found here too or in Volume 25, Issue 5.

Box 1. Table of contents for the Virtual Special Issue—Climate Change and Education, Environmental Education Research

Balancing the tensions and meeting the conceptual challenges of education for sustainable development and climate change—Blum et al. (Citation2013)

Responses to climate change: exploring organisational learning across internationally networked organisations for development—Boyd and Osbahr (Citation2010)

A review of the foundational processes that influence beliefs in climate change: opportunities for environmental education research—Brownlee, Powell, and Hallo (Citation2013)

Development and validation of the ACSI: measuring students’ science attitudes, pro-environmental behaviour, climate change attitudes and knowledge—Dijkstra and Goedhart (2012)

Harnessing homophily to improve climate change education—Monroe et al. (Citation2015)

Understanding and communicating climate change in metaphors—Niebert and Gropengiesser (Citation2013)

Beyond individual behaviour change: the role of power, knowledge and strategy in tackling climate change—Kenis and Mathijs (Citation2012)

Normalizing catastrophe: an educational response—Jickling (Citation2013)

Development and validation of the anthropogenic climate change dissenter inventory—Bentley, Petcovic, and Cassidy (Citation2019)*

Identifying effective climate change education strategies: a systematic review of the research—Monroe et al. (Citation2019)*

Textbooks of doubt: using systemic functional analysis to explore the framing of climate change in middle-school science textbooks—Román and Busch (Citation2016)

Enhancing learning, communication and public engagement about climate change—some lessons from recent literature—Wibeck (Citation2014)

Geographical process or global injustice? Contrasting educational perspectives on climate change—Waldron et al. (Citation2019)*

Hope and climate change: the importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people—Ojala (Citation2012b)

Significant life experiences, motivations and values of climate change educators—Howell and Allen (Citation2019)*

Conceptualizing climate change in the context of a climate system: implications for climate and environmental education—Shepardson et al. (Citation2012)

Together, the historic studies, those collated in Issue 5 and the current issue, help illustrate a range of questions researchers and scholars have been pursuing over the last decade. Such questions were initially flagged by Reid at the launch of the Virtual Special Issue, and have been redeveloped and republished here as Reid (Citation2019b). Running the gamut of why climate change education has emerged, where to look for critical analysis of practice and new directions in the philosophy, policy, and practice of this and cognate areas, and what research and researchers have to offer debates about capacity building, awareness, participation and action strategies1, we trust all three collections offer a timely and provocative call to reflection and action about climate change and education, and help us address the questions noted in Box 2. These might include in discussions and responses to COP meetings, critique and planning at ACE Dialogues, as well as in local and regional events to address climate change and education priorities1.

Box 2. Examples of key questions about climate change education (Source: Reid Citation2019b)

What is climate change education expected to accomplish?

Are current approaches to climate change education sufficient to the task?

What can be said about climate change education based on research evidence?

What hasn’t yet been researched adequately, or enough, in relation to climate change education?

On what grounds should climate change education be assessed and evaluated?

In more detail, the articles in the Virtual Special Issue were selected to illustrate how some of the design principles, actual forms and substance of climate change education programs have come into being, as well as vary tremendously. In the current issue, Monroe and colleagues (2019) take stock of this plurality, using a literature review to distil whether some CCE strategies are more effective than others. They argue those that increase 'program success', are:

focused on making climate change information personally relevant and meaningful for learners

have activities or educational interventions designed to engage learners.

Their review also identifies four additional themes in teaching strategies (p. 801), ‘that may help move learners beyond the basics of climate science:

Educators used deliberative discussion to help learners better understand their own and others’ viewpoints and knowledge about climate change.

Learners were given the opportunity to interact with scientists and to experience the scientific process for themselves.

Programs were specifically designed to uncover and address misconceptions about climate change.

Learners were engaged in designing and implementing school or community projects to address some aspect of climate change’.

They conclude their review stating:

Very few articles in our collection, however, embraced the goal for climate change education articulated by Kagawa and Selby (Citation2010, 4): ‘the learning moment can be seized to think about what really and profoundly matters, to collectively envision a better future, and then to become practical visionaries in realizing that future.’ In addition, we identified very few educational programs that intentionally approached climate change from both social and science disciplines (multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, or transdisciplinary).

The analysis offered by Monroe et al. (Citation2019) is echoed in some of the latest round of publications offered by environmental educators and researchers to practitioners, particularly those trying to establish a quality evidence base for practice and guidance in this area. As Henderson (Citation2019) notes in a book review including in this issue on two examples of recent texts (Communicating Climate Change: A Guide for Educators, by Armstrong, Krasny, and Schuldt (Citation2018), and Young’s (2018) Confronting Climate Crises through Education: Reading Our Way Forward), educators and researchers have sought ‘to move climate change education away from earlier and simplistic versions of information transmission and toward a more socially complex form. They accomplish this by rooting climate change education practices in findings from environmental psychology and communication that suggests that how people understand climate change is related to their individual values and the framing narratives of their broader social communities’ (p. 989). As Henderson concludes, we are now witnessing the expansion of ‘the conception of climate change education away from what’s broadly seen as a failed emphasis on the notion that individual action alone is sufficient for dealing with climate change at scale’, coupled with an increasing use of ‘education to stimulate a broader stirring of an ecological consciousness in learners […] using that newfound understanding to affect change beyond individual actions and instead toward broader climate impacts at scale’ (p. 989).

Such points made by Monroe, Henderson and colleagues are typical of a deeper questioning in this field of research and practice regarding whether any form of CCE can be uniformly assumed to be a good thing, sparking further questions of what environmental educators have to bring to the table and might well need to leave behind, in a range of formal and informal settings, when responding to the climate crisis (see also Monroe, Oxarart, and Plate Citation2013, 2015; Lambert and Bleicher Citation2014; Stylinski et al. Citation2017). This is because, as expressed in other contributions to the collections (e.g. Brownlee, Powell, and Hallo Citation2013; Kunkle and Monroe Citation2019; Howell and Allen Citation2019), education and educational researchers must consider why different approaches to CCE seem to take root, blossom and/or whither, and in this, maintain a focus on whether and how they actually foster learning (see also McBean and Hengeveld Citation2000; Walsh and Cordero Citation2019; Lawson et al. Citation2019; Ignell, Davies, and Lundholm Citation2019; Topp, Thai, and Hryciw Citation2019; Ouariachi et al. Citation2019). This may also be contrasted with those programs or initatives feeding, generating or disrupting climate inaction, despair or amotivation (Pruneau, Khattabi, and Demers Citation2010; Dillon Citation2019), be that at the time of the 'educational event', and/or within lifelong or lifewide learning, such as when we consider research on the short and longer term effects of the capacity or limitations to a program, activity, life experience or the action competence it promises (Busch, Henderson, and Stevenson Citation2019).

As noted in Box 3, for UNESCO (2017, 11), a starting point might be to view learning outcomes for CCE as framed by the ‘cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioral’. Nevertheless, these terms should not be treated as a universal prescription: as Monroe et al. (Citation2019) note, good education practice often recognises the value of engaging in deliberative discussions, addressing misconceptions, and implementing school or community projects, and of course, likely varies depending on ‘audience segmentation’. Or as Brownlee, Powell, and Hallo (Citation2013) note, we can’t ignore the effects of psychological, human-evolutionary, and social–ecological processes. They also highlight the significance of place as a connector for climate change learning (see also Schweizer, Davis, and Thompson Citation2013), while Howell and Allen (Citation2019) emphasise the significant of place, relationships and significant life experiences within and beyond educational settings, in the forming or reforming of climate change educators, especially in relation to their motivations and valuing of social justice and/over the biosphere. (The argument might also be extended to consider experience of and with disciplinary, interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches to education, Ho and Seow Citation2017).

Box 3. Learning objectives for SDG 13 ‘Climate Action’ (Source: UNESCO Citation2017b, 36–37, Table 1.2.13, Box 1.2.13a. Box 1.2.13b)

Table 1.2.13 | Climate Action | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Cognitive learning objectives

The learner understands the greenhouse effect as a natural phenomenon caused by an insulating layer of greenhouse gases.

The learner understands the current climate change as an anthropogenic phenomenon resulting from increased greenhouse gas emissions.

The learner knows which human activities—on a global, national, local and individual level—contribute most to climate change.

The learner knows about the main ecological, social, cultural and economic consequences of climate change locally, nationally and globally and understands how these can themselves become catalysing, reinforcing factors for climate change.

The learner knows about prevention, mitigation and adaptation strategies at different levels (global to individual) and for different contexts and their connections with disaster response and disaster risk reduction.

Socio-emotional learning objectives

The learner is able to explain ecosystem dynamics and the environmental, social, economic and ethical impact of climate change.

The learner is able to encourage others to protect the climate.

The learner is able to collaborate with others and to develop commonly agreed-upon strategies to deal with climate change.

The learner is able to understand their personal impact on the world’s climate, from a local to a global perspective.

The learner is able to recognize that the protection of the global climate is an essential task for everyone and that we need to completely re-evaluate our worldview and everyday behaviours in light of this.

Behavioural learning objectives

The learner is able to evaluate whether their private and job activities are climate friendly and—where not—to revise them.

The learner is able to act in favour of people threatened by climate change.

The learner is able to anticipate, estimate and assess the impact of personal, local and national decisions or activities on other people and world regions.

The learner is able to promote climate-protecting public policies.

The learner is able to support climate-friendly economic activities.

Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives

1. Learning objectives for achieving the SDGs

Box 1.2.13a. Suggested topics for SDG 13 ‘Climate Action’

Greenhouse gases and their emission

Energy, agriculture and industry-related greenhouse gas emissions

Climate change-related hazards leading to disasters like drought, weather extremes, etc. and their unequal social and economic impact within households, communities and countries and between countries

Sea-level rise and its consequences for countries (e.g. small island states)

Migration and flight related to climate change

Prevention, mitigation and adaptation strategies and their connections with disaster response and disaster risk reduction

Local, national and global institutions addressing issues of climate change

Local, national and global policy strategies to protect the climate

Future scenarios (including alternative explanations for the global temperature rise)

Effects of and impacts on big eco-systems like forests, oceans, glaciers and biodiversity

Ethics and climate change

Box 1.2.13b. Examples of learning approaches and methods for SDG 13 ‘Climate Action’

Perform a role-play to estimate and feel the impact of climate change related phenomena from different perspectives

Analyse different climate change scenarios with regard to their assumptions, consequences and their preceding development paths

Develop and run an action project or campaign related to climate protection

Develop a web page or blog for group contributions related to climate change issues

Develop climate friendly biographies

Undertake a case study about how climate change could increase the risk of disasters in a local community

Develop an enquiry-based project investigating the statement ‘Those who caused the most damage to the atmosphere should pay for it’

What next for climate change education and research, when and in what ways?

Returning to some of our opening themes, reflecting on these studies should open up a host of questions about what educators have learnt and might need to (un)learn as a profession, as well as what needs investing in, and divesting.

Some of the conversations with work published here and in other scholarship might be with those engaged in researching ‘edutainment’, social movements, social marketing, and other pseudo- or para-educational spheres of action. For Cantell et al. (Citation2019), key questions that need to be addressed concern the adequacies of models, structures, programs and communications for capacity building on CCE (see again, ). Earlier, Blum et al. (Citation2013) identified that education policy and practice for CCE at state, national, regional and international levels works better together than in silos or when one level pulls against the other, and that too may require different senses of scope and approaches to modelling and building CCE, testing it, enactions, evaluations—and research. On reviewing and appraising current provision (e.g. Chang and Pascua Citation2017; McKenzie Citation2019), in asking whether CCE activities foster learning and assessing efforts to embed that, we might also consider do/must they also displace teachers’ own prior or ongoing curriculum development efforts attuned as these are, perhaps, to local conditions and needs? In other words, will transforming local education into a CCE aligned with, say, multinational or international concerns, be what ‘best practice’ in education (only?) means, particularly if it is largely with an eye to what is sanctioned as such by some external (or distant) body, e.g. the UN’s CC:Learn (https://www.uncclearn.org/), or the Alliance for Climate Education (https://acespace.org/)?

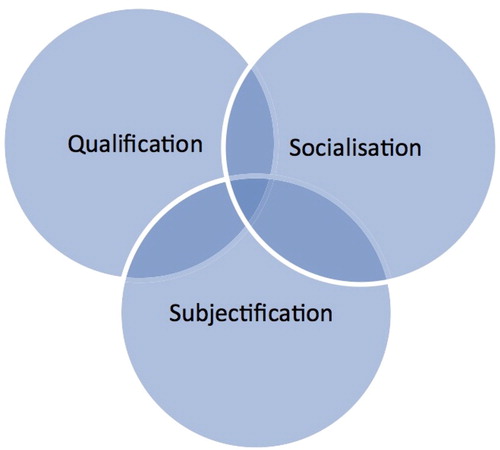

Ways to address such conundrums have included attempts to draw on and apply Biesta’s (Citation2013) account of the three functions of education and the domains of educational purpose, to reflect on these and related challenges for education () (see Nguyen Citation2019; Singer-Brodowski et al. Citation2019). (In fact, we drew on this too, when launching the Virtual Special Issue at COP23.)

Figure 2. Three functions of education, and their intersections (Source: Biesta, Citation2013).

To elaborate briefly, for Biesta (Citation2013), the content, weighting and intersections matter for the three domains:

The qualification domain concerns ‘the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and dispositions.’

In the context of CCE, qualification might involve providing participants with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that allow them to ‘do something’—e.g., knowing why climate change is something important to address in their lives, and those of others.

The socialization domain is about ‘the ways in which, through education, we become part of existing traditions and ways of doing and being.’

In the context of CCE, socialization, whether explicitly or implicitly, might be concerned with integrating individuals into existing social, cultural and political orders through the transmission of norms and values—e.g., learning to work with others to advance solutions to climate change problems in the local to wider communities they are a member of.

The subjectification domain refers to the ‘subjectivity’ or ‘subject-ness’ of those we educate.

In the context of CCE, subjectification might focus on positioning students as ‘subjects of initiative and responsibility rather than as objects of the actions of others’—e.g., appreciating how climate change challenges affect the horizons for justice in my/your life, and the choices I/you can make to take action, mindful of the dynamics and context of my and others’ lives too.

Biesta (Citation2013) maintains that all three domains are important for education, but he is particularly concerned with how educators, educationalists and education policy makers treat the subjectification function. In fact, he defines any ‘education worthy of the name’ as ‘education that is not only interested in qualification and socialization but also in subjectification’ (p. 139). This is because the process of subjectification is pregnant with the promise of bringing something radically new into a broken world. The new is something that cannot be foreseen or legislated; by its very nature it will require risk-taking and draw on the weakness inherent in education to afford anything radical. Thus for CCE, it might well mean: not just knowing the facts about climate change or how people feel in the face of it (one part of the qualification function), but rather, ensuring climate change education addresses people’s rights to be free of oppressions created by climate injustices, including being able to live lives they have good reason to imagine and choose, i.e. that will foster rather than inhibit sustainability, equity, and authenticity in their lives as well as those in their communities. This is because in addressing the relationship among the three domains, Biesta (Citation2013) suggests, ‘Even if we are “just” trying to give our students some knowledge, we are also impacting on them as persons—to have knowledge will, after all, potentially empower them—and, in doing so, we are also representing particular traditions, for example by communicating that this particular knowledge is more useful or valuable or truer than other knowledge’ (p. 78).

Thus one way of interpreting the intersections in for CCE, is to note that more environmental knowledge on its own, does not lead to changes in attitudes or behavior (Dijkstra and Goedhart Citation2012), while as Wibeck (Citation2014) shows, understanding for qualification or socialisation is not necessarily the same as its engagement and possible transformation through subjectification. (This has echoes in the findings of Kenis and Mathijs (Citation2012), in evidence of ‘strategy skepticism’ among their study participants: as a consequence of a lack of confidence in individualistic actions, learners may omit strategic reflection on broader spheres and possibilities of collective and emergent forms of agency or actions.)

So to return to Box 3, it isn’t controversial for advocates or educators to ask that we ‘unite behind the science,’ as Greta Thunberg argued in her recent speech to the National Assembly in Paris (23 July 2019). But considering the functions of education, the focus might shift to which senses and practices of science, the social sciences, humanities and/or arts? And which should count in CEE objectives, topics, approaches and methods (Reid Citation2019b)? For instance, in terms of learning objectives and topics, social and educational research has already highlighted the critical role of learning about social norms and framings in directing curriculum and relationships to the more-than-human world (e.g. Norgaard Citation2006; Doherty and Clayton Citation2011; Ojala Citation2012b, Jickling Citation2013; Marshall Citation2014). In light of this, on the one hand, it shouldn’t be surprising to find ‘collective avoiding’ and ‘emotion management’ associated with fears of ontological insecurity, experiences of trauma, helplessness and guilt, or in threats to individual and collective senses of identity. On the other though, what was, is and could become norms and frames are also implicated and ripe for (re)consideration when increasing ecological literacy and sense of place, or in the widening of ethical responsibility to challenge consumerism, or in promoting emotional resilience and empowerment at individual, community and systems levels (Hung Citation2017). Because as Ojala (Citation2012b, 625) notes, for the joint livelihood of people and planet, ‘hope is not only a pleasant feeling but could also work as a motivational force, if one controls for denial’?

Equally, for Maslin (Citation2013, 138 and 140), what's needed in collective approaches to education and capacity building through and beyond our cultural and socio-political institutions is clear:

We must not pin all our hopes on global politics, clean energy technology, and geoengineering—we must prepare for the worst […] and adapt. If implemented now, much of the cost and damage that could be caused by changing climate can be mitigated. However, this requires nations and regions to plan for the next 50 years, something that most societies are unable to do due to the very short-term perspective of political institutions. This means our climate issues are challenging the vary way we organize our society. Not only do they challenge the concept of the nation-state versus global responsibility, but also the short-term vision of our political leaders. To answer the question of what we can do about climate change—we must change some of the basic rules of our society to allow us to adopt a much more global and long-term sustainable approach.

We return to these points below, but meanwhile, with Morton (Citation2013), it might even become more a matter of aligning educational leadership with ontology, and engagement with epistemology, to ensure good edugovernance strategies rather than shaming tactics, when he states (p.183):

Reasoning as the search for proof only delays, and its net effect is denial. … the trouble with the … reason-only approach … is that human beings are currently in the denial phase of grief regarding their role in the Anthropocene. It’s too much to take in at once. Not only are we waking up inside a gigantic object, like finding ourselves in the womb again, but a toxic womb—but we are responsible for it. And we know that we are really responsible simply because we understand what global warming is. We don’t really need reasons—reasons inhibit our responsible action, or seriously delay it.

Indeed, Morton (Citation2013) has also noted: ‘I am one of the entities caught in the hyperobject I here call global warming’, (p.3), that ‘Hyperobjects provoke irreductionist thinking’, (p.19) and the situation we find ourselves is akin to ‘the feeling that we humans are playing catch-up with reality’ (p.21) (see also Saari and Mullen Citation2018, on implications for research in this field).

Climate change and an ethics of education + an education in ethics?

Chang’s (Citation2015, 183) relatively recent editorial on climate change education and research though, eschews any conceptual or theoretical privileges, concluding with the observation that how one approaches:

teaching climate change would need to balance between developing learners who can critically engage new information about the phenomena as well as being empathic individuals who are committed to take action to make their living environment a better one.

Yet for Kagawa and Selby (Citation2010, 241) this position is unlikely to do sufficient justice to what is at stake: ‘In the face of runaway climate change nothing short of a lived paradigm shift is needed’. Their edited collection is a watermark in thinking about CCE, arguing (pp. 241–243) among other things that:

Education can only help allay a threatening condition by addressing root causes

Climate change education needs to happen within interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary frames

There can be no ethical and adequately responsive climate change education without global climate justice education

The educational response to climate change needs to be both local and global

Wherever it takes place, climate change education needs to be a social and holistic learning process

There is the need for educators to urgently and radically rethink through the implications of the invisibility and uncertainty of climate change.

In one of the contributions to that collection, Hoffmann (Citation2007, 7) is cited to warn:

Global warming needs a response that isn’t only at the level of managing an environmental problem to ensure the planet is just about liveable on in the years to come—it needs one that addresses the essential un-freedom, suffering and misery within the present global system.

[used as an epigraph to Lotz-Sisitka, Citation2010, 71]

Education then, will have a clear role in ‘net zero’ intiatives (as flagged by the SDGs and UNFCCC), but we cannot avoid the ethical and questions about the ethics of education (again, see Jickling Citation2013). For Simovska and Prøsch (Citation2016), the urgency of addressing climate change though, shouldn’t be treated as a trump card to corral education into a particular form or direction. Rather, what is at stake when treating education as a ‘silver bullet’ or ‘panacea’ for the climate crisis is the further risk of it becoming ‘un-educational’ too (p. 644), as can be found in other rapid responses to ‘crisis’ that then seem to result in an often singular or narrow educational response, e.g. a focus on behaviour change:

It is not the task of schools to solve societal problems. However, within the logic of critical perspectives on education, educational work with key societal issues (Klafki, Citation2005), including health and sustainability (Schnack, Citation2000, Citation2008), does belong within the domains of schooling. Moreover, if the purpose of education is more than formal qualification and socialization (Biesta, Citation2006, Citation2013) and also includes ‘rupture in the order of things’ (Ranciére cited in Biesta, Citation2013, 84) to allow space for subjectification, real-world oriented aims and participatory pedagogies, i.e., those related to … sustainability education … are worth considering.

It is our view that the articles in this journal on the issue of CCE are some of those worth considering in 2019, as they offer a diversity of scholarly thinking and research about climate change and education that supports both a pluralistic and experimental approach. Taken together, they illustrate a range of possible foci and approaches to education and education research too (Busch, Henderson, and Stevenson Citation2019), from what may be regarded as the 'traditional' (e.g. measurements and surveys of conceptions and practices, construct analysis, policy evaluation and critique, ethnographies and interviews, applications of theory, model development, action research) to the 'avant garde' (e.g. post-human inquiries and others with other-than-anthropocentric ends-in-view). While in spiralling across a variety of scales of time and space, power and personhood, and methods and methodologies, they variously touch on, nudge and rework aspects of the following:

educator and learner questions, concepts, beliefs, values, adaptive capacities, networks, actions, interactions and intra-actions, and contexts for climate change education (e.g. Boyd and Osbahr Citation2010; Shepardson et al. Citation2012; Brownlee, Powell, and Hallo Citation2013; Shealy et al. Citation2019; Devine-Wright, Devine-Wright, and Fleming Citation2004; Sezen-Barrie, Miller-Rushing, and Hufnagel Citation2019a; cf. Dove Citation1996; Leiserowitz Citation2006; Whitmarsh Citation2009; Porter, Weaver, and Raptis Citation2012; Blum et al. Citation2013; Öhman and Öhman Citation2013; Plutzer et al. 2016; Kolleck et al. Citation2017; Verlie and CRR 15 Citation2018),

the influence of everyday life, cultural to transcultural and subcultural norms, class, gender, age, personal beliefs, emotions, imagery and metaphors, information seeking and representations, consensus claims, risk perception, coping strategies, friends, parents and family in building or dissipating concern (Sternäng and Lundholm Citation2012; Boyd and Osbahr Citation2010; Kenis and Mathijs Citation2012; Niebert and Gropengiesser Citation2013; Stevenson, Peterson, and Bondell Citation2019; cf. Bord, O'Connor, and Fisher Citation2000; Leiserowitz Citation2004; Citation2006; Moser Citation2007; Hulme Citation2009; Leiserowitz, Maibach, and Roser-Renouf Citation2009; Myers et al. 2012; Adger et al. Citation2013; Cook et al. Citation2013; Otieno et al. Citation2014; Byrne et al. Citation2014; Meeusen Citation2014; Capstick et al. Citation2015; Theobald et al. Citation2015; Pearse Citation2017; Kunkle and Monroe Citation2019),

the role of evidence, argumentation, reasonableness, ideologies such as climate change denial, mental models and biases, cognitive challenges in comprehending visual representations and metadata projections, and expertise in designing and evaluating educational activities and communications about climate change (Shepardson et al. Citation2012; Bentley, Petcovic, and Cassidy Citation2019; Sezen-Barrie, Shea, and Borman Citation2019b; Waldron et al. Citation2019; Hestness, McGinnis, and Breslyn Citation2019; cf. CRED Citation2009; CitationTaber and Taylor 2009; Dunlap and McCright Citation2011; Möser and Dilling Citation2011; Whitmarsh Citation2011; Kahan Citation2013; Niebert and Gropengiesser Citation2013; Moser Citation2016),

strategies to identify 'leadership’ in thought, education and politics, polarizations, disconnects, skepticism and obstacles (Boon Citation2010; Stevenson et al. Citation2014; Ojala Citation2015; cf. Forter 2001; Nisbet and Kotcher Citation2009; Gonzalez-Gaudiano and Meira-Cartea Citation2010; Hoffman Citation2011; Sterman Citation2011; Whitmarsh Citation2011; Kahan et al. Citation2012),

niche and common constructs and foci, such as climate literacy, climate justice, carbon footprints, human and more-than-human rights, communication frames, professional preparation and development, instructional designs and experiments, textbooks and materials, and adaptive designs for diverse participants (Román and Busch Citation2016; Siegner and Stapert Citation2019; Stapleton Citation2019; cf. Pruneau et al. Citation2003; McCaffrey and Buhr Citation2008; Whitmarsh Citation2008; Maibach et al. Citation2010; Akerlof, Bruff, and Witte Citation2011; Corner and Randall Citation2011; Hart Citation2011; Skamp, Boyes, and Stanisstreet Citation2013; Hestness et al. Citation2014; Busch and Román Citation2017; Drewes, Henderson, and Mouza Citation2018; Meehan, Levy, and Collet-Gildard Citation2018),

education policy development, and barriers and critique, when faced with climate change as a ‘wicked problem’, ‘super wicked problem’, or ‘hyperobject’ (McKenzie Citation2019, Saari and Mullen Citation2018; cf. Lorenzoni, Nicholson-Cole, and Whitmarsh Citation2007; Hamilton Citation2011; Morton Citation2013; Laessøe and Mochizuki Citation2015; Moyson, Scholten, and Weible Citation2017; UNFCCC Citation2018).

To return to a point raised by Jickling (Citation2013, 174), stepping back from the manifold complexity, options and detail will require addressing not just the ‘science and technology’ but also the ‘art and humanity’ of recent inquiries and activities in this space, as CCE speaks to a complicated phenomenon (even a ‘hyperobject’, in Morton’s terms):

In a certain way, environmental researchers and/or educators are also involved in [these] ideological struggle[s], whether they want it or not. Their position is not easy. On the one hand, they cannot claim to make ‘objective’ judgments. On the other hand, they cannot neglect this terrain either, as they then risk allowing for it to be occupied by movements, governments or companies that also have other interests than the ‘common good’. Maybe the task of researchers and/or educators can be to try to make the range of possible analyses, visions and strategic options visible and to make their assumptions, effects and implications explicit.

Resonating with themes raised by Biesta, Jickling (Citation2013) goes on to state (ibid.):

Good education that can enable change, and that can transcend the status quo, requires non-conformism and risk. … ‘We should not regret our inability to perform a feat which no one has any idea how to perform. Having performed one, it is there as an example’ (Richard Rorty, cited in Saul Citation2001, 77). And, with such examples, we may enable learners to tackle the ‘impossible’.

Some studies that represent the ‘low hanging fruit’ of CCE inquiry, are argubly small-scale studies of educator and learner concepts and perceptions, use simplistic Knowledge-Attitude-Behaviour models, or don’t check embedded assumptions that might need to be set to one side (see Reid Citation2019a). On the latter, for example, guidelines that draw on NOAA’s version of climate literacy will likely and largely remain those of a subset of science literacy, and are both framed and languaged as such (see also Box 3); the obvious question to ask is can the humanities, arts and social sciences help reimagine a 'climate literacy' for these times (Reid Citation2019b, Siegner and Stapert Citation2019), or even rework this with notions drawn from contemporary concepts of emotional literacy, maturation and intelligence in ‘self formation’ (e.g. Powell et al. Citation2019, Verlie Citation2019)?

Equally, Wibeck (Citation2014, 387) recommends that ‘scholars of environmental education focus critical attention on how practice addresses senses and spheres of agency; sociocultural factors; and the complexities of developing scientific literacy given the interpretative frames and prior understandings that are brought to bear by the public in non-formal education settings’. So to achieve this, we might also need to move away from a single to multiple sense of literacy, from concerns with micro to macro scales, and from relying on short to longer term studies. While as these collections show, there are plenty of single program evaluations to wider phenomenological and policy-level critiques (including their intersections and interactions) available, and they do illuminate the multipliers and diminishers for the (dis)connections between education, economic and environmental policies and practices (Busch, Henderson, and Stevenson Citation2019).

As a further case in point, the journal has yet to receive a research study on the economics of climate change education, or on the various conditions of ‘security’ for it to take place, or those that track its impacts on the very conditions often treated as the horizon for evaluation, i.e. climate change and education (see Lotz-Sisitka Citation2010). In this, it might not simply be a question of determining how much is invested in CCE in comparative terms (as with the indicators for the IPCC, UNFCCC or SDGs), but could be in relation to budgets and budgeting as a whole, in education and environment, or for sustainability? Take, for example, the global valuation of ecosystem services. If these are valued at approx. $145 trillion per year for 2011 (using 2007 $US), but are declining in value by 2-14% (Costanza et al. Citation2014), this trend will multiple and magnify experiences of precarity, especially in the context of a climate crisis. Yet noting that these services ‘contribute more than twice as much to human well-being as global GDP’, then strategic action in conservation, social justice and education could work hand-in-hand to mitigate such trends? This might be through concerted action in relation to ACE, SDG4.7 and climate change education, but also in treating education and training as central to any ‘Green New Deal’, and so forth.

To conclude, as Kenis and Mathijs (Citation2012, 58) put it:

closing the ‘gap’ between knowledge and action does not in the first place—at least not in the case of environmentally aware citizens—require a further raising of people’s knowledge of the environmental problem as such. What seems to be needed, is the knowledge of root causes, visions on alternatives and especially strategies to reach these.

While Zylinska (Citation2014, 9) in her ‘Minimal Ethics for the Anthropocene’, is perhaps less circumspect:

Life typically becomes an object of reflection when it is seen to be under threat. In particular, we humans have a tendency to engage in thinking about life (instead of just continuing to live it) when we are made to confront the prospect of death: be it the death of individuals due to illness, accident or old age; the death of whole ethnic or national groups in wars and other forms of armed conflict; but also of whole populations, be it human or nonhuman ones.

Buildings burn, as do forests. How one responds to these events is a measure of what education we have had, what we’ve been schooled in, and what we want to contribute to in this world. Our last words go to environmental educators and researchers. Laessøe et al. (Citation2009) note that some CCE scholars and researchers see themselves (or like to be regarded as) innovators and critics, while for others, it is largely as experts, documenters and/or agents. For the first, as we trust we show in these collections, their quest is unlikely to be that of deferring judgement or action until comprehensiveness in CCE research is secured, but using current evidence well to find and pursue renewed purposes for education in and for these times.

The role of the expert too, can be reimagined, particularly if it is at risk of folding back into being too narrow, arm-chairish or esoteric. Fires on the margins can soon spark major events, as with the SDGs and ESDGs, but also quite literally in the case of Notre Dame and this summer’s fires in the forests of South America. For researchers-as-documenters, dwelling on the state of the art and new possibilities could serve to generate 'subjectifications' in ways that could culminate in ‘new wine’ that can’t be contained by ‘old skins’, particularly if ‘pyro-pedagogies’ and ‘practice architectures’ are brought into consideration too? Finally, we have researchers-as-agents in interactive knowledge development with other stakeholders. On this, Wallace-Wells argues that in confronting the climate crisis ‘we need to fight to make the world the one we want to live in rather than giving up hope before the fight is really over’ (Tucker Citation2019). With this in mind, because education is always-already about learning organisations, learning systems, learning from experience and inquiry, and new horizons for learning and teaching, then perhaps it is to Wallace-Wells’ horizon, relying as it does on translational, mediational and relational values in practice, that will prove most crucial in mobilizing and improving research and practice in CCE?

Acknowledgements

Ideas and themes for the three collections have emerged from various conversations and presentations over the past decade, starting with a series of workshops reflecting on education’s role in responding to the ‘menace of global warming’ (Monbiot Citation2006). Initial thematics were presented in ‘Nobody ever rioted for austerity: education and the climate change debate’ during the author’s sabbatical from University of Bath, UK, hosted by Monash University, Australia (2009). They were further crystallised in the AHRC’s ‘Site, Performance and Environmental Change symposium’ (http://performancefootprint.co.uk/documents/glascove/alan-reid/), and the first climate change education symposium at the American Educational Research Association (2015) in Chicago, on ‘The Failure to Act: Climate Change Injustice, Denial, and Education’ (http://tinyurl.com/k8obvg8). The broadening of the work then took shape during a second sabbatical, hosted at Nicole Ardoin’s Social Ecology Lab, Stanford University (April 2017), and ongoing work with her on NAAEE’s eePRO research and evaluation and climate change education groups, and throughout the co-convening of the research strand of the World Environmental Education Congress, Vancouver (September 2017) and research symposium of the North American Association for Environmental Education Conference, in Washington DC (October 2017). This work, and especially comments from members of the Global Environmental Education Partnership, all contributed to the launch of, and follow-up to, the Virtual Special Issue at COP23 Bonn (November 2017), with additional inputs from Marcia McKenzie. Special thanks for sparks and steers along the way go to Essi Aarnio-Linnanvuori, Soraya Bozetto, KC Busch, Chew-Hung Chang, Justin Dillon, Jo Ferreira, Rachel Forgasz, Dee Heddon, Julia Heiss, Joe Henderson, Martha Monroe, Mahesh Pradhan, Kartikeya Sarabhai, Bill Scott, Venka Simovska, Kathryn Stevenson, Adriana Valenzuela Jimenez, Blanche Verlie, and Hilary Whitehouse.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alan Reid

Alan Reid edits the international research journal, Environmental Education Research, and publishes regularly on environmental and sustainability education (ESE) and their research. Alan's interests in research and service focus on growing traditions, capacities and the impact of ESE research. A key vehicle for this is his work with the Global Environmental Education Partnership, and via NAAEE's eePRO Research and Evaluation group. Find out more via social media, pages or tags for eerjournal, and his ORCID entry.

Notes

1 For example, “Action on Climate Change Through Education,” EECOM 2019, advertised as Canada’s ‘first national environmental education conference with a focus on climate change education’ (https://eecom.org/eecom-2019/).

References

- Adger, W. N., J. Barnett, K. Brown, N. Marshall, and K. O'Brien. 2013. “Cultural Dimensions of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation.” Nature Climate Change 3(2): 112–117. doi:10.1038/nclimate1666.

- Akerlof, K., G. Bruff, and J. Witte. 2011. “Audience Segmentation as a Tool for Communicating Climate Change.” Park Science 28(1): 56–64.

- Anderson, A. 2010. Combating Climate Change Through Quality Education. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

- Anderson, A. 2012. “Climate Change Education for Mitigation and Adaptation.”Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 6(2): 191–206. doi:10.1177/0973408212475199.

- Armstrong, A. K., M. E. Krasny, and J. P. Schuldt. 2018. Communicating Climate Change: A Guide for Educators. Ithaca, NY: Comstock Publishing Associates.

- Bangay, C., and N. Blum. 2010. “Education Responses to Climate Change and Quality: Two Parts of the Same Agenda?” International Journal of Educational Development 30(4): 359–450. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.11.011.

- Benavot, A., M. McKenzie, C. Chabbott, A. Smart, M. Sinclair, J. Bernard, J. H. Williams and N. Chopin. 2019. The Transitions Project: Education for sustainable development and global citizenship, From pre-primary to secondary education. Technical Report (August). Paris: UNESCO.

- Bentley, A. P. K., H. L. Petcovic, and D. P. Cassidy. 2019. “Development and Validation of the Anthropogenic Climate Change Dissenter Inventory.” Environmental Education Research 25(6): 867–882. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1250150.

- Berger, P., N. Gerum, and M. Moon. 2015. “Roll up Your Sleeves and Get at It!” Climate Change Education in Teacher Education.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 20: 154–173.

- Berkhout, F., J. Hertin, and D. M. Gann. 2006. “Learning to Adapt: Organisational Adaptation to Climate Change Impacts.” Climatic Change 78(1): 135–156. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9089-3.

- Bieler, A., R. Haluza-Delay, A. Dale, and M. McKenzie. 2018. “A National Overview of Climate Change Education Policy: Policy Coherence between Subnational Climate and Education Policies in Canada (K-12).” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 11(2): 63–85. doi:10.1177/0973408218754625.

- Biesta, G. 2006. Beyond Learning: Democratic Education for a Human Future. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Biesta, G. 2013. The Beautiful Risk of Education. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Blum, N., J. Nazir, S. Breiting, K. Chuan Goh, and E. Pedretti. 2013. “Balancing the Tensions and Meeting the Conceptual Challenges of Education for Sustainable Development and Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 19(2): 206–217. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.780588.

- Boon, H. J. 2010. “Climate Change? Who Knows? A Comparison of Secondary Students and Pre-Service Teachers.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 35(1): 104–120. doi:10.14221/ajte.2010v35n1.9.

- Bord, R. J., R. E. O'Connor, and A. Fisher. 2000. “In What Sense Does the Public Need to Understand Global Climate Change?” Public Understanding of Science 9(3): 205–218. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/301.

- Boyd, E., and H. Osbahr. 2010. “Responses to Climate Change: Exploring Organisational Learning across Internationally Networked Organisations for Development.” Environmental Education Research 16(5–6): 629–643. doi:10.1080/13504622.2010.505444.

- Branch, G. 2018. Climate Education Funding in Washington. Oakland, CA: National Center for Science Education. https://ncse.com/news/2018/03/climate-education-funding-washington-0018732.

- Brownlee, M. T. J., R. B. Powell, and J. C. Hallo. 2013. “A Review of the Foundational Processes That Influence Beliefs in Climate Change: Opportunities for Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 19(1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.683389.

- Busch, K. C., and D. Román. 2017. “Fundamental Climate Literacy and the Promise of the Next Generation Science Standards.” Teaching and Learning About Climate Change: A Framework for Educators, edited by D. P. Shepardson, A. Roychoudhury, and A. S. Hirsch, 120–133. London: Routledge.

- Busch, K. C., J. A. Henderson, and K. T. Stevenson. 2019. “Broadening Epistemologies and Methodologies in Climate Change Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 25(6): 955–971. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1514588.

- Byrne, J., M. Ideland, C. Malmberg, and M. Grace. 2014. “Climate Change and Everyday Life: Repertoires Children Use to Negotiate a Socio-Scientific Issue.” International Journal of Science Education 36(9): 1491–1509. doi:10.1080/09500693.2014.891159.

- Cantell, H., S. Tolppanen, E. Aarnio-Linnanvuori, and A. Lehtonen. 2019. “Bicycle Model on Climate Change Education: Presenting and Evaluating a Model.” Environmental Education Research 25(5): 717–731. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1570487.

- Capstick, S., L. Whitmarsh, W. Poortinga, N. Pidgeon, and P. Upham. 2015. “International Trends in Public Perceptions of Climate Change over the past Quarter Century.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 6(1): 35–61. doi:10.1002/wcc.321.

- Center for Research on Environmental Decisions (CRED). 2009. The Psychology of Climate Change Communication: A Guide for Scientists, Journalists, Educators, Political Aides, and the Interested Public. New York: Columbia University. https://guide.cred.columbia.edu.

- Cerullo, M. 2019. “French Billionaires Slow-Walk Donations to Rebuild Notre Dame.” CBS News, 5 July. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/notre-dame-fire-update-big-donors-delay-fulfilling-pledges-to-rebuild-notre-dame/.

- Chang, C. 2014. Climate Change Education: Knowing, Doing and Being. New York: Routledge.

- Chang, C. H. 2015. “Teaching Climate Change – A Fad or a Necessity?” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24(3): 181–183. doi:10.1080/10382046.2015.1043763.

- Chang, C., and L. Pascua. 2017. “The State of Climate Change Education – Reflections from a Selection of Studies around the World.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 26(3): 177–179. doi:10.1080/10382046.2017.1331569.

- Costanza, R., R. de Groot, P. Sutton, S. van der Ploeg, S. J. Anderson, I. Kubiszewski, S. Farber, and R. K. Turner. 2014. “Changes in the Global Value of Ecosystem Services.” Global Environmental Change 26: 152–158. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002.

- Cook, J., D. Nuccitelli, S. A. Green, M. Richardson, B. Winkler, R. Painting, R. Way, P. Jacobs, and A. Skuce. 2013. “Quantifying the Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming in the Scientific Literature.” Environmental Research Letters 8(2): 024024–024027. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024.

- Corner, A., and A. Randall. 2011. “Selling Climate Change? the Limitations of Social Marketing as a Strategy for Climate Change Public Engagement.” Global Environmental Change 21(3): 1005–1014. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.05.002.

- Devine-Wright, P., H. Devine-Wright, and P. Fleming. 2004. “Situational Influences upon Children’s Beliefs about Global Warming and Energy.” Environmental Education Research 10(4): 493–506. doi:10.1080/1350462042000291029.

- Dijkstra, E.M., and M.J. Goedhart. 2012. “Development and Validation of the ACSI: Measuring Students’ Science Attitudes, Pro-Environmental Behaviour, Climate Change Attitudes and Knowledge.” Environmental Education Research 18(6): 733–749. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.662213.

- Dillon, J. 2019. “University Declarations of Environment and Climate Change Emergencies.” Environmental Education Research 25(5): 613–614. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1646022.

- Doherty, T. J., and S. Clayton. 2011. “The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change.” American Psychologist 66(4): 265–276. doi:10.1037/a0023141.

- Dove, J. 1996. “Student-Teacher Understanding of the Greenhouse Effect, Ozone Layer Depletion and Acid Rain.” Environmental Education Research 2(1): 89–100. doi:10.1080/1350462960020108.

- Drewes, A., J. Henderson, and C. Mouza. 2018. “Professional Development Design Considerations in Climate Change Education: Teacher Enactment and Student Learning.” International Journal of Science Education 40(1): 67–89. doi:10.1080/09500693.2017.1397798.

- Dunlap, R., and A. McCright. 2011. “Organized Climate Change Denial.” In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society, edited by J. Dryzek, R. Norgaard, and D. Schlosberg, 145–160. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fortner, R. W. 2001. “Climate Change in School: Where Does It Fit and How Ready Are We?” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 6(1): 18–31.

- Fortner, R. W., J. Y. Lee, J. R. Corney, S. Romanello, J. Bonnell, B. Luthy, C. Figuerido, and N. Ntsiko. 2000. “Public Understanding of Climate Change: Certainty and Willingness to Act.” Environmental Education Research 6(2): 127–141. doi:10.1080/713664673.

- Foster, J. 2008. The Sustainability Mirage: Illusion and Reality in the Coming War on Climate Change. London: Earthscan.

- Foster, J. 2015. After Sustainability: Denial, Hope, Retrieval. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Francis, P. 2015. Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home. Papal Encyclical Letter.

- Gleason, T. 2019. “Towards a Terrestrial Education: A Commentary on Bruno Latour’s down to Earth.”Environmental Education Research 25(6): 977–986. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1649369.

- Gonzalez-Gaudiano, E., and P. Meira-Cartea. 2010. “Climate Change Education and Communication: A Critical Perspective on Obstacles and Resistances.” In Education and Climate Change: Living and Learning in Interesting Times, edited by D. Selby and F. Kagawa, 13–34. Oxon: Routledge.

- Hamilton, L. C. 2011. “Education, Politics and Opinions about Climate Change Evidence for Interaction Effects.” Climatic Change 104(2): 231–242. doi:10.1007/s10584-010-9957-8.

- Hart, P.S. 2011. “One or Many? the Influence of Episodic and Thematic Climate Change Frames on Policy Preferences and Individual Behaviour Change.” Science Communication 33(1): 28–51. doi:10.1177/1075547010366400.

- Harvey, F., and J. Ambrose. 2019. "Pope Francis declares 'climate emergency' and urges action." The Guardian Friday 14 June. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jun/14/pope-francis-declares-climate-emergency-and-urges-action.

- Hayden, M., R. Houwer, M. Frankfort, J. Rueter, T. Black, and P. Morteld. 2011. “Pedagogies of Empowerment in the Face of Climate Change Uncertainty.” Journal for Activist Science and Technology Education 3(1): 118–130.

- Henderson, J. 2019. “Learning to Teach Climate Change as If Power Matters.” Environmental Education Research 25(6): 987–990.

- Hestness, E., J. R. McGinnis, and W. Breslyn. 2019. “Examining the Relationship between Middle School Students’ Sociocultural Participation and Their Ideas about Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 25(6): 912–924. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1266303.

- Hestness, E., R. C. McDonald, W. Breslyn, J. R. McGinnis, and C. Mouza. 2014. “Science Teacher Professional Development in Climate Change Education Informed by the Next Generation Science Standards.” Journal of Geoscience Education 62(3): 319–329. doi:10.5408/13-049.1.

- Hicks, D., and A. Bord. 2001. “Learning about Global Issues: Why Most Educators Only Make Things Worse.” Environmental Education Research 7(4): 413–425. doi:10.1080/13504620120081287.

- Ho, L.C., and T. Seow. 2017. “Disciplinary Boundaries and Climate Change Education: Teachers' Conceptions of Climate Change Education in the Philippines and Singapore.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 26(3): 240–252. doi:10.1080/10382046.2017.1330038.

- Hoffman, A. J. 2011. “Talking past Each Other? Cultural Framing of Skeptical and Convinced Logics in the Climate Change Debate.” Organization and Environment 24(1): 3–33. doi:10.1177/1086026611404336.

- Hoffmann, M. 2007. “The Day after Tomorrow: Making Progress on Climate Change.” Radical Philosophy 143: 2–7. https://www.radicalphilosophyarchive.com/wp-content/files_mf/rp143_commentary1_dayaftertomorrow_hoffman.pdf

- Howell, R. A., and S. Allen. 2019. “Significant Life Experiences, Motivations and Values of Climate Change Educators.”Environmental Education Research 25(6): 813–831. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1158242.

- Huckle, J., and A. E. J. Wals. 2015. “The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: Business as Usual in the End.”Environmental Education Research 21(3): 491–505. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1011084.

- Hulme, M. 2009. Why We Disagree About Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hung, R. 2017. “A Critical Trilogy of Place: Dwelling in/on an Irritated Place.” Environmental Education Research 23(5): 615–626. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1182624.

- Ignell, C., P. Davies, and C. Lundholm. 2019. “A Longitudinal Study of Upper Secondary School Students’ Values and Beliefs regarding Policy Responses to Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 25(5): 615–632. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1523369.

- IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Core Writing Team, edited by R. K. Pachauri and L. A. Meyer. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

- Jensen, B. B., and K. Schnack. 2006. “The Action Competence Approach in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 12(3–4): 471–486. doi:10.1080/13504620600943053.

- Jickling, B. 2013. “Normalizing Catastrophe: An Educational Response.” Environmental Education Research 19(2): 161–176. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.721114.

- Kagawa, F., and D. Selby (Eds.). 2010. Education and Climate Change: Living and Learning in Interesting Times. New York: Routledge.

- Kahan, D. 2013. “Making Climate-Science Communication Evidence-based - All the Way down.” In Culture, Politics and Climate Change: How Information Shapes Our Common Future, edited by D. Crow and M. Boykoff, 203–220. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kahan, D. M., E. Peters, M. Wittlin, P. Slovic, L. L. Ouellette, D. Braman, and G. Mandel. 2012. “The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks.” Nature Climate Change 2(10): 732–735. doi:10.1038/nclimate1547.

- Kemmis, S., and R. Mutton. 2012. “Education for Sustainability (EfS): Practice and Practice Architectures.” Environmental Education Research 18(2): 187–207. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.596929.

- Kenis, A., and E. Mathijs. 2012. “Beyond Individual Behaviour Change: The Role of Power, Knowledge and Strategy in Tackling Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 18(1): 45–65. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.576315.

- Klafki, W. 2005. Dannelsesteori Og Didaktik – Nye Studier [General Education and Didaktik – New Studies]. 2nd ed. Århus: Klim.