Abstract

In many countries’ policy documents and curricula, teachers in the subject areas of science, social science and language are encouraged to collaborate on cross-curricular issues such as sustainable development (SD). This study is conducted in secondary schools (compulsory years 7-9) in Sweden and investigates the similarities and differences in the responses of ten teacher groups (forty-three teachers in total) to questions about their teaching contributions in their own subject areas to education for sustainable development (ESD). The overall aim is to understand how teachers of these three subject areas can contribute to cross-curricular teaching in teacher teams in the context of ESD. This is done by analysing the group responses from data collected in group discussions concerning the teaching dimensions what (content), how (methods) and why (purposes) in relation to ESD. We first analyse the teacher group responses and arguments regarding their contribution to ESD teaching from each subject area separately. Thereafter, we comparatively analyse how the different subject areas’ contributions overlap or complement each other in a potential collaborative ESD teaching. The results show that teachers from different subject areas stress different yet complimentary dimensions of teaching and perspectives of ESD. The implications for cross-curricular teaching in ESD are also discussed.

Introduction

There are many reasons for studying education for sustainable development (ESD) in the subject areas of science, social science and language due to its interdisciplinary nature. According to the Swedish national curriculum (Education Citation2011) for the nine-year compulsory school (7-16 years), teachers in all subjects and subject areas in years 7-9 are responsible for teaching and promoting sustainable development (SD). This is often done by individual teachers who try to teach in accordance with the ESD approach stressed in UN policy documents (UNESCO Citation2005; Citation2017). The same curriculum emphasises that teachers should collaborate on complex issues such as SD using a cross-curricular teaching approach. Teachers from different subject areas (such as science, social science and language) are expected by both peers and the school management to carry this out in practice. Language teachers, for example, are expected to teach sustainability issues collaboratively in order to make it possible for students to reach one of the sixteen common national goals for the compulsory school that explicitly address SD (Education Citation2011).

In this study, collaboration across subjects and subject areas in a secondary school context is called cross-curricular teaching (Hudson Citation1995). This is commonly practiced in secondary schools in Sweden and often takes the form of thematic units on common themes in which different types of subject area teaching meet. It was introduced into the Swedish school system in the early 1980s through the national curriculum that was in place at that time (Education Citation1980). SD and ESD have been two of the most typical thematic units that cross-curricular teaching has revolved around at the secondary school level. Very few studies have investigated this phenomenon, although some large-scale quantitative studies have been undertaken (Borg et al. Citation2012; Citation2014). The results from these large-scale studies show that there are subject-based differences in Swedish secondary teachers’ conceptual understanding of SD, as well as differences in their teaching approaches towards ESD. In this study we use qualitative methodology to zoom in on these interesting differences in order to expand them further and elucidate how teachers in different subject areas contribute to collaborative cross-curricular teaching.

We address this question by studying the differences and similarities in the teachers’ descriptions of the teaching dimensions what, how and why in order to discern how and why they consider their subject areas to be important and how they contribute, or could contribute, to cross-curricular ESD teaching. These three teaching dimensions are widely recognised in European educational research related to subject specialisation (i.e. Hopmann Citation2007; Sjoberg Citation2009) and are outlined by Klafki (Citation1995) as a way of discerning teachers’ instructional approaches. In this study we investigate them in relation to ESD. The what-dimension focuses on ESD-related subject matter and abilities, the how focuses on the methods and the collaborations and influences outside the local school context that are used in the teaching, while the why focuses on the teachers’ starting points and long-term purposes for their ESD teaching. Finally, we compare the results of the three teacher subject areas to determine whether and how their teaching coincides or differs. The main contribution of this study is to fill the gap in the ESD research field relating to how different subject area teachers contribute to ESD teaching. Often the E in ESD is forgotten and taken for granted in policy documents and research (Wals and Kieft Citation2010; Sund and Lysgaard Citation2013). This is the reason to use the term ESD teaching to underline the educational and didactical focus of this article.

Background

In this section we define ESD, discuss the importance of cross-curricula teaching and describe the Swedish context.

ESD

The concept or idea of ESD has often been contested in the research debate due to its strong link to policy (e.g. Hesselink, van Kempen, and Wals Citation2000; Jickling and Wals Citation2008; Wals and Kieft Citation2010; Sumner Citation2008). In international UN policy documents the concept of ESD in school reform and teaching practices has often been treated as unproblematic (Sund and Wickman Citation2008). In the Swedish steering documents, ESD is based on the discourse found in UN policy (Borg et al. Citation2014). Therefore, in this study we do not outline previous discussions about the contested concept of ESD, but instead take a pragmatic approach to the relevance of ESD and how it is understood by the teachers taking part in the study, which to a large extent stems from the curricula and societal discourse.

By educating citizens, and especially the younger generations in the formal schooling system, the hope has been to address the issue of SD (Bonnet, 1999). This hope led to the launch of the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development, overseen by UNESCO, and its further development into the current Global Action Plan (GAP). In response to this hope, ESD was launched as an approach to teaching and learning that promoted SD. Hence, a very specific long-term purpose is built into the concept of ESD that reflects the why-dimension. Since its inception ESD has developed from an idea into a global movement (Hopkins Citation2012) and the understanding of what it is or should be has evolved during the last decades. The UNESCO (Citation2013) definition of ESD is:

“Education for Sustainable Development means including key sustainable development issues into teaching and learning; for example, climate change, disaster risk reduction, biodiversity, poverty reduction, and sustainable consumption. It also requires participatory teaching and learning methods that motivate and empower learners to change their behaviour and take action for sustainable development. Education for Sustainable Development consequently promotes competencies like critical thinking, imagining future scenarios and making decisions in a collaborative way”

In this definition two essential features of ESD can be identified. The first deals with content, the what-dimension, and the second with the pedagogy or way of teaching, the how-dimension. These two essential features of ESD are recognised in the literature: ‘ESD continues to grow both in content and pedagogy and its visibility and respect have grown in parallel’ (Hopkins Citation2012, p. 2). As seen in the UNESCO definition, the ESD content covers diverse disciplines, such as climate change and consumption, thus requiring teachers to draw from multiple disciplines. In policy and research the disciplinary content of ESD is most often defined by the three dimensions of environment, society and economy (Giddings, Hopwood, and O'Brien Citation2002). However, n ESD teaching it is not clear how this multidisciplinarity of ESD content should be handled. This means that when investigating ESD teaching practices the what-dimension is important.

The second essential feature of ESD deals with teaching and learning, the how-dimension. In the UNESCO documents ESD is defined as a teaching approach that includes participatory teaching, scenario teaching etc. In line with this definition, in the research literature ESD pedagogy is often suggested to promote competences (Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman Citation2011) through progressive pluralistic teaching (Rudsberg and Öhman Citation2010; Pauw et al. Citation2015). Therefore, the how-dimension is important when investigating ESD teaching practices.

In their large-scale quantitative study of upper secondary teachers, Borg et al. (Citation2012) identify discipline-bound differences and teaching traditions. For example, they find that science teachers focus on facts, while social science teachers focus on developing student’s abilities. There are also clear differences in approaches to the what- and how-dimensions. In discussions about ESD I and ESD II, Vare and Scott (Citation2007a) contend that teaching needs both the what- and how-dimensions, because the one complements the other. This view is not always shared when implementing ESD in national curricula, where cross-curricula barriers guard the differences between content-based and competence-based approaches (Tschapka Citation2012). In practical terms, ESD I is subject-centered (the what), whereas ESD II focuses more on developing lifelong abilities (the how) that naturally require working with some kind of subject matter (Vare and Scott Citation2007a). This resembles Dewey’s (Citation1916/1999) position on the development of abilities or competences, where he regards the attempt to develop general abilities without a subject matter (the what) as impossible. It is suggested that addressing the choices of content and methods in ESD teaching promotes action competence for sustainability (Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010). The underlying idea is that ESD teaching should cover the complexity of SD issues and prepare students to become sustainable decision-makers in the future (Lijmbach et al. Citation2002). As a consequence, the why-dimension is important when investigating ESD teaching practices. In this study we investigate the three teaching dimensions of ESD to gain a more complete understanding of the ESD that is enacted in three different subject areas.

As already stated, there is strong support for ESD in the 2011 Swedish curriculum (Education Citation2011). The curriculum for the nine-year compulsory school is goal-oriented. One of the sixteen aims concerns sustainable development (Education Citation2011, p. 8):

“It is the responsibility of the school that all individual students can observe and analyse the interactions between people in their surroundings from the perspective of sustainable development.”

Statements like this occur in many of the national curricula and school plans developed by the United Nations (cf. policy ESD school plans developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, UNECE). The question is, how should teachers from different subject areas enact this goal together? This is addressed in the next section.

Cross-curricular teachers

One starting point for this study is that the disciplinary backgrounds and teaching aims developed in teacher education play an important role in forming different subject area teaching traditions (Borg et al. Citation2012). In some disciplines SD is part of the teaching tradition, while in others it is not (Stables and Scott Citation2002). For example, science and geography teachers recognise SD as an extension of the environmental education that is part of their core curriculum (Breiting Citation2000), while language teachers have tended to avoid teaching about SD (Borg et al. Citation2012). In this way, school subjects frame SD differently (Bernstein Citation1999) and teachers from these different frames could be said to teach ESD in various ways as discussed by Gericke et al. (Citation2020). The overall question under investigation in this study is: What kind of potential teaching could be enacted when teachers from these different subject areas come together to teach ESD in cross-curricular settings in secondary school? In educational research, these types of settings are sometimes called multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary, although both these terms are most often associated with upper secondary schooling, higher education and academic disciplines. In this study we therefore use the term cross-curricula teaching.

In the literature, cross-curricular, multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary arrangements are described as cornerstones of, and essential elements for, successful ESD teaching (e.g. Eilam and Trop Citation2010; Vare and Scott Citation2007a). Hence, it is important to investigate how different subject teachers can or do complement each other in this endeavour. The focus in this study is specifically on their potential teaching contributions and not on practical collaboration processes between individual teachers or curriculum integration as such, which are dealt with elsewhere, for example by Applebee, Adler, and Flihan (Citation2007), Drake (Citation1998), (McPhail Citation2018), MacMath (Citation2011) and Relan and Kimpston (Citation1993).

A school subject usually has its origins in one or more university disciplines. Biology is a clear example of a discipline with a one-to-one equivalent to school biology, while the school subject of civics is rooted in political science and national economics. Hence, school subjects are transformed from academic disciplines into school subjects in very different ways (Gericke et al. Citation2018). This makes studying cross-curricular topics such as ESD interesting. How do teachers of different subjects and subject areas enact these topics in their teaching? Is there an overlap? Are the teachers’ contributions complementary? These questions form the starting points for this study. As indicated in previous studies (Borg et al. Citation2012; Citation2014; Oulton et al. Citation2004), there are differences in teachers’ enactments of topics such as ESD in various school subjects.

The Swedish context

Some subjects in the Swedish secondary school are formed into subject areas, such as science, social science and language, where common aspects such as perspectives, knowledge production or teaching methods make it possible for one teacher to teach a group of related subjects. In Sweden it is common for a secondary school teacher to teach between two to four school subjects in years 7-9 (students aged 13-16 years). There are no single subject teachers in theoretical subjects. For example, science teachers often teach biology, chemistry, physics and mathematics (collectively called science studies), social science teachers teach civics, history, geography and religion (collectively called social study subjects) and language teachers often teach the Swedish language (first language) combined with a second language (English), or a third language such as German, French or Spanish. In this study we call these subject combinations a subject area. In the Swedish secondary school context, cross-curricular teaching involves collaboration between different subject areas, where, for example, teachers of science, social science and language are expected to work together on complex thematic issues such as ESD.

There is support for ESD and cross-curricular teaching in the 2011 Swedish curriculum, where guidelines for cross-curricular teaching are stressed: ‘Teachers should have opportunities to work along cross-curricular lines’ (Education Citation2011, p. 8). Moreover, in Sweden secondary school teachers are often organised in teacher teams consisting of teachers from the different subject areas teaching the same group of students. Generally speaking, these teacher teams could serve as good organisational structures for cross-curricula teaching, but in practice this can vary from school to school.

Aim of the study

The aim of the study is to investigate the potential teaching contributions to ESD from the three different subject areas of science, social science and language at secondary school level in cross-curricular settings. The study discerns the similarities and differences in the teaching contributions by analysing the teachers’ own descriptions of ESD teaching in terms of the content (what), methods (how) and purposes (why). The research question are:

1) What are the specific ESD teaching contributions to the different subject areas of science, social science and language?

2) How are these contributions unique and how do they overlap?

Methodology

Group discussions inspired by the focus group method were used to dynamically explore the research question in a way that challenged and discerned the views and positions of individuals in a social context (Osborne and Collins Citation2001). It is helpful to organise a group discussion around something that the participants have in common. The method also creates a good atmosphere, which in turn gives people confidence to discuss freely (Flores and Alonso Citation1995). The common strand in this case was that the participants were grouped according to their subject area teaching. This interview context thus offered a degree of support and security, as well as the option of listening rather than speaking. The kind of discussion that is created can deepen a common understanding and description of a common culture within a group (Flores and Alonso Citation1995), which in this study is the teaching of ESD in different subject areas. Moreover, semi-structured and open-ended group discussions are established methods for gathering data about teachers’ apprehensions of, and reflections on, their teaching practices (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009; Mishler Citation1986).

Research design

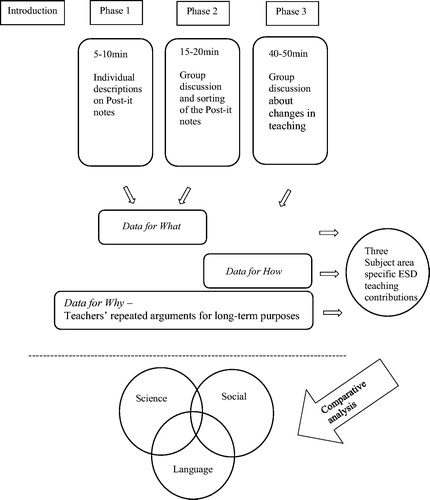

In order to answer the research question, group discussions with groups of teachers representing the subject areas of science, social science and language were conducted. Ten groups were invited to participate in the focus group discussions according to the three phase design outlined in . This design was developed for two reasons. First, we wanted to secure a shift between individual and group reflections in the group discussions so that all the teachers’ voices were heard and at the same time enabled them to make collaborative meaning of their ESD teaching. Second, we wanted to make sure that the teachers described their teaching in terms of the what, how and why dimensions. In addition, an interview guide was developed and used in order to steer the discussions towards these teaching dimensions. The entire group discussion lasted for between 80-100 min () and the sessions were audio- and video recorded. The group discussions were transcribed verbatim and the complete transcripts were analysed according to the what-dimension (on the teaching content and abilities and their relations to ESD) in transcripts from phases 1 and 2, the how-dimension (on how the teachers conducted their teaching) in transcripts from phase 3 and the why-dimension (on the teachers’ long-term purposes of their teaching) in the transcripts from all the three phases. The analysis was based on analytical questions that exposed important aspects of the teaching dimensions according to previous ESD studies, as described below. The results were treated as a group voice from teachers teaching a specific subject area. Finally, a comparative analysis was conducted in which the results from the three subject areas were compared in order to identify whether the various subject areas contributions overlapped or complemented each other in a potential collaborative ESD teaching.

Selection of teachers

Teacher groups from the subject area of science (chemistry, biology and physics), social science (civics, history, geography and religion) and language (Swedish [mother tongue], second language [English] and third language [German, French and Spanish]) were chosen from five secondary schools in two Swedish municipalities. We asked the principals to assess the availability of all teachers in the different subject areas. As a result, a total of 14 male and 29 female teachers volunteered to participate in the discussions. The teachers were then grouped into 10 teacher groups according to school and subject area, with between 3 and 10 teachers in each group. The distribution of the discussion groups in the different subject areas was four science (fifteen teachers in total), three social science (twelve teachers in total) and three language groups (sixteen teachers in total). The teachers in each group had worked for some years at the same school, had between 2-32 years of teaching experience and most of them had previously participated in some cross-curricular work. The groups were quite homogenous in the distribution of teaching experiences, professional backgrounds and knowledge about cross-curricular teaching. The discussions were conducted from March to November 2017.

Group discussion procedure and analysis – three phases

The group discussions were guided by specific questions (see below) and were developed into more open group discussions about different aspects of teaching as they progressed over the three phases. A more detailed description of the procedure is provided below and also in .

Phase 1

In this phase the aim was to gather data from the individual teachers in each group before the group discussion started. This ensured that each teacher’s voice was heard individually. The discussion leader (first author) introduced the group event and then everyone briefly introduced themselves to the discussion leader (the teachers already knew each other well). After the introduction the teachers were asked to individually and in silence write down their responses on post-it notes to the question: How do you think that your science/social science/language teaching contributes to the implementation of sustainable development in your school?

Each teacher had their own coloured post-it notes that were specific to them, which then made it possible to trace each teacher individually in the next step. On the whole the teachers needed 5-10 min to write down their answers and they completed between 4-20 notes each. Each teacher was then asked to read their responses aloud to the group and briefly explain what they meant.

Phase 2

In this phase the aim was to gather data from the teachers’ discussions without any interference from the discussion leader. Here, the teachers discussed and categorised their written responses on the post-it notes. Each group stood in front of a whiteboard, explained their responses to each other and stuck their post-it notes on the board. At first they put the notes up in a random fashion, but after a while some categories started to emerge and were agreed on. After about 15-20 min the notes were categorised according to the teachers’ own ideas about how they should be sorted. These categorisations were photographed and used as data, see for an example. The notes, categories and teacher discussions from phases 1 and 2, which together lasted for 30-40 min, constituted the data for responding to the what-dimension.

Figure 2. This picture show the six categories made by a group of social science teachers (translated from Swedish). From upper left to right the categories read: thematic work, actions at the local school, core content. From lower left to right the categories read: environmental awareness for life, teaching methods, reception and personal treatment.

Phase 3

In this phase the aim was to gather data about the teachers’ teaching. This was done by asking them about their teaching practices in relation to ESD, and how this had changed in the last ten years due to the curriculum changes in 2011 that included ESD and cross-curricula teaching. In the same way as in phase one, the teachers first reflected individually in silence for 4-8 min and made notes about their teaching practices. This initial individual part, before the group discussion, facilitated a broader variation of data about the changes in their teaching practices. In this phase the focus was on the teachers’ discussions about how their teaching was conducted and took around 40-50 min to complete. The data in this part mainly made the how-dimension visible.

The data was analysed using analytical aspects (see ) in order to identify the important characteristics of environmental and sustainability teaching (Sund Citation2008; Sund and Wickman Citation2011). The teachers’ ways of discussing these aspects highlighted the different methods and points of departure in the enactment of ESD teaching and were responses to the analytical question: How is the teaching in this specific subject area commonly conducted?

Table 1. Three analytical aspects relating to environmental and sustainability education that help researchers to make teachers’ methods and conduct of teaching more visible.

Summary of the three phases – Why

The teachers’ arguments about the long-term purposes of their teaching were discussed and referred to in relation to both the what- and how-dimensions. The data transcripts from all three phases constitute the data for the why-dimension.

Analytically we identified the why-dimension by looking for the teachers’ ‘anchor points’ (Nikel Citation2005). An anchor point is a verbal argument, often a term such as ‘awareness’ and ‘tools’, or specific expressions such as ‘they need to know the facts’ and ‘the students need to be personally involved’, that the respondents repeat during the discussions. Iterative readings of the data revealed patterns in the starting points for these repetitions. This in turn became an anchor point of departure for the teacher groups’ argumentation about why some repeated issues were particularly important. The anchor points formed a coherent context for long-term purposes, which in this study is seen as an illustration of what the teacher group regarded as the most important reasons for teaching ESD. These results were first summarised for each teacher group and then for each subject area in order to answer the analytical question: What does this teacher group, in this specific subject area, really care about together when discussing their ESD teaching? Or in short: What is their object of responsibility?

Limitations and validity

All research studies have their limitations. In this study we decided to use a reflexive ‘on-action’ design, instead of an ‘in-action’ design using observations, because we were also interested in the teachers’ incentives and purposes for their ESD teaching. The enacted curriculum, i.e. how the teachers actually taught in the classroom, was only indirectly studied in our design and was based on the teachers’ self-reports in the group discussions. It is known that there can be differences between what teachers say they do and what they actually do in practice in such a research design. In order to make a full and irrefutable study of teachers’ practices, the research design would need to contain interviews with teachers and students and also classroom observations (cf. Applebee, Adler, and Flihan Citation2007; Ross and Hogaboam-Gray Citation1998). This study looks at possible contributions from different subject areas to ESD teaching. From this point of view we think that the research design using teachers’ discussions is appropriate. The risk of social desirability is low because we did not ask the teachers how they collaborated today with other teachers. Instead, we identified the potential for collaboration based on what they said they did now in each subject area. Also, group discussions have been found to create a good atmosphere and often give people confidence to discuss freely (Flores and Alonso Citation1995).

A methodological limitation for generalising our results is the number of participating teacher groups. Also, the presentation of ‘group voices’ in this study could limit the possibilities to make intergroup comparisons. For example, the more experienced teachers’ voices are probably somewhat stronger than those of the less experienced teachers in discussions about the changes in teaching over the last ten years in phase 3. However, the less experienced teachers could both support and confirm the contemporary status of teaching in the specific subject area. Another example is that language teachers have different ‘individual voices’ for their starting points in first language teaching and second language teaching (Celce-Murcia Citation1991). Likewise, differences between ‘teacher voices’ within a subject area, for example in science between biology and physics, or in social science between geography and religion, are also possible. However, as the teachers of different school subjects in one subject area (e.g. biology and physics or geography and religion) are often the same individuals in a secondary school context in Sweden, we can assume that the differences within one subject area will be much less than those between different subject areas, thereby making the research design valid. Moreover, teachers in the different subject areas work together and build what we could call a community of practice (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). However, we encourage further studies into the differences in each subject area in order to obtain a more detailed and deepened picture.

The trustworthiness and validity of this study is strengthened because it builds on and further investigates previous findings in large-scale studies comparing similar groups of teachers representing subject areas (Borg et al. Citation2014). To increase the reliability, the iterative analysis process included co-coding and repeated author meetings, which kept the process moving towards a state of saturation (Bryman Citation2015). All the authors participated in the analysis and presentation of results in order to increase their reliability. This type of collective open iterative process helps to ensure that the study can be repeated by other research groups and that a good intersubjective scientific grounding can be reached.

Results

The comprehensive results of the what- and how-dimensions are presented first, followed by the why-dimension for each subject area, starting with the science subject area and ending with language. For each subject area the result is presented together with some examples and excerpts for the what, how and why. The excerpts are coded to show their origins in the different teacher groups. The science group is coded as Sc 1, the social science group 2 as So 2 and language group 3 as L 3 and so on. This means that the individual group variations are to some extent visible to the reader. Finally, a summary of what, how and why is presented to form a common picture of the teaching contribution to ESD from each of the separate subject areas.

Subject area of science

Four teacher groups participated in the subject area of science. The results from these groups show a slight variation in their responses.

What

On the post-it notes the teachers mainly wrote and discussed subject matter topics such as use of energy, energy production, fossil fuels, ecology, eutrophication, toxics and radiation, as well as global environmental issues such as global warming, acidification and UNESCO’s seventeen global goals. The content mainly related to the ecological perspective of ESD directly, such as eutrophication, or indirectly, for example the consequences of global warming on biodiversity.

There were some explicit expressions during the what-categorisation discussions about creating a factual foundation for individual choices:

“Knowledge base for own choice, influence of others, that pupils have enough knowledge to choose energy sources, know why they do that and the kind of influence this has at home.” [Sc 3]

Some topics were ecologically specific, but were mentioned as important for the development of a basic knowledge:

“That they understand that when you look at a food chain and a consumer disappears, they can at least see that this can also influence us … Having enough basic knowledge to be able to act. Yes, that’s the kind of person we want to be with and create.” [Sc 1]

The what-dimension was based on scientific facts that were mostly related to the ecological perspective.

How

In the first analytical aspect concerning the teaching methods that were used to develop individual or collective abilities, the teachers thought that teacher-centred teaching focused more on the individual student’s scientific knowledge. Methods for developing abilities for societal change were seldom mentioned. This implies that informed individual choices based on facts will solve many of the common societal problems. In the second analytical aspect regarding context and usefulness, the teaching was conducted using textbooks and the Internet as primary sources. The focus was on science to be used in the local school context. Teaching activities outside school context were rare. In the third aspect on power relations and student participation, the science teachers regarded the role of the student as quite marginal. The teachers said that they tried to stimulate students’ interests, but mainly as inspiration for a teacher-centred teaching that contained very few group work activities or group discussions. Hence, student influence and participation were not strong in these science groups. In actual fact the media influenced the teachers more than the students:

“The media affects how I plan my teaching and the kind of material I use to a greater extent than the students.” [Sc3]

Longer group discussions or work that could facilitate the development of more collective abilities were not common. Group work had become shorter and was more about understanding different opinions:

“Yes, there’s more small talk, turning around and checking with your neighbour, but group work in group work form that was common before is now obsolete because it’s no longer fruitful.” [Sc 1]

A question about information sources for teaching revealed details about teaching methods:

“Yes, but it’s me, or the textbook, I read more from that aloud now than I did five years ago in order to include those who are dyslexic. Films are also information sources, as are YouTube clips, that’s also a brilliant channel for this kind of thing” [Sc 4]

The teaching in this specific subject area was commonly classroom-based and teacher-centred. The focus was on transferring facts and developing students’ individual abilities in science subjects.

Why – the object of responsibility

The common object of responsibility for the science groups was Students’ scientific knowledge.

All the four science groups regularly and repeatedly discussed students’ scientific knowledge as their main objective. There was a concern that facts were lost in the new curriculum, where discussions about values and the new focus on abilities, such as reflection and critical thinking, were important.

“What I wrote [on the post-it] was that the new curriculum, the implementation is rather from more fact-based to less fact-based, more oriented towards abilities.” [Sc 3]

There was also some concern about the need for students to acquire knowledge that would help them to make good decisions in their everyday lives. The long-term purpose of the science teacher groups was to offer students a good knowledge base of facts for life.

“I tell them that if they have this knowledge they can have influence over what they buy and what they use and what they make use of, but also in the long-run how they vote in a general election.” [Sc 3]

Summary of the ESD teaching in the subject area of science

The science teachers’ content contribution to ESD teaching mainly consisted of topics relating to environmental problems. The what-dimension was most often related to ecological issues that reflected a lack of knowledge and that could be solved by learning more science. The teaching was focused on the subject knowledge and the main aim was to teach students factual and conceptual knowledge. The how, a teacher-centred teaching, did not give students many opportunities to develop action competence abilities. As students’ participation was limited, the implication is that teachers take account of students’ interests through previous teaching experiences and observations of students’ attitudes and opinions when planning and conducting their lessons. The why, the purpose of ESD teaching, was to offer students a good scientific factual foundation that would enable them to make good individual decisions on sustainability issues.

Subject area of social science

Three teacher groups participated in this subject area. The results from the discussions showed little variation in the responses.

What

On the post-it notes the teachers mainly wrote and discussed subject matter, such asglobalisation, sustainability, world trade, consumption, human rights, colonialism, the media, consumers’ rights, population growth but also the ecological effects of the use of natural resources, transport and climate change. Thematic work titles such as our city and become an entrepreneur also appeared on the notes. There were a lot of comments about learning outcomes, such as environmental awareness, how to behave and treat other people and the teachers highlighted generic skills such as co-operation, looking for information, analysing and critical thinking. The teachers connected topics such as demographics to sustainability and the environment:

“One working area is population development, demographics, also connected to consumption. It will be better in the world in the sense that the population will not infinitely increase, but that people will have better lives and … that consumption will therefore be at a higher level. How will this be sustainable? It will have an environmental feel to it.” [So 2]

The social science teachers connected social issues like trade to environmental issues:

“For example, we did the working area of business in year 8 around the global shopping bag. I mostly want to talk about the environment and I think this could be about the working environment and the living environment in different ways.” [So 3]

The social perspective was in focus in the content, but some comments related to the ecological perspective.

How

The teaching methods that were used were discerned through expressions about how they worked in group discussions with the consequences of climate change, saving humankind and social justice towards other people and cultures. Here, the development of individual abilities and being trained in collective situations were in focus. It was about using group work situations to develop a social action competence for individuals’ own use, starting with knowledge, a competence that was about developing perspectives, reasoning and source evaluation. It was rarely about changes in lifestyles, but there were strong hopes of educating good democratic citizens. The teaching was mainly connected to the local school in which some school projects were conducted, such as weighing food waste and keeping common spaces clean. Study visits, guest lectures and collaborative projects with or in the community were mentioned, such as local urban development projects. Student participation in group work during a lesson was common, whereas longer work over several lessons was rare. Student participation and interests were important aspects in the teaching. Role-play, such as investigative journalists, was used to maintain the students’ interest:

“One working moment in year 9 was when they had to pretend to be investigative journalists and try to find out how different things were made and what the working conditions for those making the things were like, you know football boots, clothes, bananas, coffee.” [So 2]

There were also examples of cooperation with the local community:

“Then I thought a lot about the projects where we collaborate with different external people, e.g. the municipality or companies and so on. We’ve also worked with projects with those at the end of year 9 this spring and there was one in year 7 called ‘Safe city [name]’.” [So 3]

The teaching methods focused on classroom-based activities where shorter group work was common. Tasks connected to the local school and surroundings occurred a couple of times each term. Student participation, influence and engagement were important in the everyday teaching.

Why – the object of responsibility

The common object of responsibility for the social science groups - Students themselves related to other people.

The social science teachers focused on and repeatedly discussed the students’ own well-being and especially that in relation to other people. ‘Other people’ often included both those outside the school and peers. There was a concern about individual students and their relations with people from other cultures. The long-term purpose of the social science teacher groups was to offer students good individual well-being and good relations with other people, which they regarded as prerequisites for a democratic citizenship:

“A democratic approach, it is after all democracy that provides the framework for how we act in both school and society so that we demonstrate a good democratic approach and attitude. It’s a way of working with sustainable development I think. You also work at being a good role model for young people. It’s about who you are. It’s not just about environmental thinking, but is also about how we manage each other, how we take care of each other. That’s also the social approach.” [So 1]

The relations between people were in focus, especially at a time of antidemocratic tendencies in Europe:

“I try to get them to be as good citizens as possible and all the time come back to, what I teach about – it might be religion, or geography, or history, you include things that can lead to being a good citizen and prevent the antidemocratic tendencies because they are growing on a global scale, well at least they are in Europe.” [So 2]

Summary of the ESD teaching in the subject area of social science

The social science teachers often regarded ESD issues as conflicts between human interests, such as the unfair global distribution of resources. Environmental problems and developmental challenges were more politically- and morally-oriented than simply learning factual knowledge. This indicated that these were political issues. The what-dimension was value- and ability-oriented towards analysing and critical thinking skills. Social science includes the entire spectrum of ESD perspectives. While the ecological perspective was mentioned, the main focus was on the social perspective. The economic perspective was discussed in relation to world trade, mainly as being globally connected and for spreading the idea of consumption as an important threat to sustainability. As ESD is anthropocentrically-oriented, human interests and developments were in focus. The politically-based perspective of ESD emphasised the importance of democracy in classroom activities, the how, through regular participation in group activities. Students were encouraged to develop their individual abilities, action competences and engage in democratic discussions about the development of a more sustainable society or world. The why-dimension of education was to strengthen the student’s well-being in relation to other people, as well as peers and people from other cultures.

Subject area of language

Three teacher groups participated in the subject area of language. The results from these groups showed only a minor variation in their responses.

What

On the post-it notes the teachers mainly wrote and discussed subject matter connected to ESD such as: climate change, energy and acidification, the climate effect of food, society and what was needed for shared concern, internationalisation and globalisation, news from the media and material from NGOs, e.g. World Wildlife Fund. They also discussed content more connected to language and countries: vocabulary and realia (about the specific countries where the actual language is spoken), comparing the livelihood conditions in different countries, texts about the surrounding world.

The language teachers commonly argued that language could be seen as a tool (reading, writing and speaking) for collaboration with and between other subject areas (usually using first language), for communicating with other people and for teaching about other cultures (usually using second language). There were some comparisons with other people’s livelihoods and some writings about the need for global recycling. Language perspectives, such as the diversity in people’s ways of relating to the surrounding world, were also mentioned. Personal development and the development of worldviews through the media on common issues like lifestyles and climate change were also regarded as important. Expressions about language working as a tool for science and social science collaborations were common in the discussions as well:

“[…] and perhaps using Swedish for different presentation forms, they should find the content from science or social science using Swedish as the tool so that the oral presentation will be as good as it can be”

[L 1]

Language teachers mentioned the ESD related content that was often found in the media:

“Encourage the students to be economical with and care for our common resources at school. Create discussion about different modes of transport and their effect on the climate. Read texts about the climate and energy consumption on the respective target language. I teach German and English. Draw attention to news about what is happening with the climate. Make the students aware of the choice of food and its effect on the climate and present solutions in the target language on sustainable development and in thematic work. .” [L 2]

How

In the first instance the teaching methods that were used, such as lecturing and small group discussions, aimed to develop individual abilities. There was a focus on individuals’ self-esteem, communicative abilities and worldviews. Communication with others was a strong focus for identity making – ‘Communication makes you a human’ [L 3]. The teaching context was classroom-based with regular support from the Internet and other ICT tools. The language teachers claimed that cross-curricular collaborations with science and social science were in place, where the focus was on promoting oral presentations. Some exchange programmes occurred outside the local school. The language teaching was rather teacher-centred, but the digitalisation of schools challenged the content and skills and created a need for a variation in methods. This need for variety sometimes put teachers in new and stressful situations where the external input made teachers feel out of control, but at the same time provided them with new opportunities. New updated content was available for argumentation and debates about issues such as climate change and recycling. Students learned foreign languages on their own and this played a major role in teaching. ICT tools gave teachers opportunities to leave the textbook and start thematic work about global issues in for example English:

“I often feel really steered by the textbooks in English but now I’m so sick and tired of them. I don’t want to work with them because they are so rigid and so limiting so that in English I’d now rather work in larger thematic areas. Everything from what happens in the world to the students’ own interests and also what they do in other subjects. So I try to find common points of contact and literature.” [L 1]

Different types of student cooperation, role-play and learning to listen to other students can contribute to an understanding of other people:

“Work for increased understanding, humility for people from different parts of the world, different social classes and so on. You think in different ways. Little moral dilemmas. Other people might not think like me. That you cooperate, learn to share and agree in pairs and in groups. That you test different roles. Listen instead of being the one who talks. Texts and discussions about the world around us, similarities and differences, understanding others and how that can contribute to sustainable development.” [L 2]

The teacher-centred teaching focused on the development of individual communicative abilities and was well connected to the global world by ICT tools. Student participation was important, but the teaching was still individual due to the ambition to offer individual learning opportunities that were adapted to the students’ specific language skills. The ICT tools used by the students during their leisure time helped to create a variation of language skills in the classroom, which was often challenging for teachers who were trying to offer each student communicative development.

Why – the object of responsibility

The common object of responsibility for the language teaching groups was Students’ emphasis on identity and communication.

The main concern for all three language groups was individual students and their relations with other people. The long-term purpose of the language teachers was to offer students good language skills that supported individual identity-making and communication with other people from different cultures in the world around them. The language teachers repeatedly returned to strengthening personal development and identity:

“I mean, like all language teachers I think that language is very important. Of course all subjects are important, but in some way it is important to make sure that students have a well-functioning language in order to strengthen them as people and that this would be useful in all subjects.” [L 1]

The teachers discussed the focus and the need for individual students’ personal development.

“P: The ability to discuss, the ability to express yourself, the ability to give a talk.

H: That was what I wrote on my notes …. Cooperation.

C: This is a bit more like self-knowledge I think.

L That’s what I think too

H: and personal development.

L: Individual circumstances.

L: It’s really all about working with the individual more than the language.” [L2]

Studies in language contributed to an international and global understanding of the conditions for human life.

“I wrote that language studies contribute to international understanding, that language increases the global aspect of human life, that language teaching helps student to given expression to ideas and signals, boils things down, social interaction, the ability to listen and interpret. You could say that communication is very important for sustainable development.” [L 3]

Summary of the ESD teaching in the subject area of language

The language teachers’ main contribution in their role as teachers of Swedish was to support the collaboration between science and social science in terms of reading, writing and presenting. The ESD-related content primarily concerned recycling and when people’s lifestyles and their consequences were regarded as threats to the natural world. Scientific knowledge was regarded as prescriptive and could indicate the best ways of living. This view resembled the views that were communicated by the media and adopted by the students. This included discussions about the economic perspective as important for achieving sustainability.

Here, the what-dimension was a mixture of language abilities such as reading and writing and normative value laden statements from science and social science about how to live ‘more ecologically correctly’. The teaching, the how, was quite teacher-centred, while the learning outcome was geared towards individual development. This was evident in discussions about the threats and possibilities of digitalisation and the desire to regain teacher control. Students were involved in argumentations, debates and discussions where they practised communication skills, but in the group discussions it was clear that the teachers wanted to be in control. There was a frustration about the great variation in students’ language skills. A strong teacher focus, especially in second language teaching, was on the individual student’s knowledge and identity-making. The why, or the long-term purpose of teaching, was students’ identity-making, personal development and communication with other people.

Summary of the contributions of the different subject areas to ESD teaching

The results of the what-, how- and why-dimensions are presented in .

Table 2. Summary of the contributions of the different subject areas to the ESD teaching dimensions.

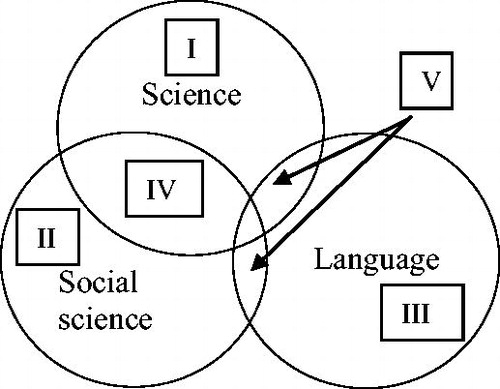

Comparative analysis

In order to make the potential contributions more visible from the results in each subject area we conducted a comparative analysis between the groups and the main contributions from each subject area. These are represented visually in . The circles represent the contribution of each subject area in the three teaching dimensions of ESD (what, how and why) according to our results. The overlap of the circles represents commonalities, i.e. where the different subject area teachers address similar issues. Hence, the overlap represents possible starting points for collaboration in cross-curricular teaching. The areas where there is no overlap represent issues that are only addressed in one subject area and is their unique contribution to ESD teaching.

Figure 3. The representation shows the different subject areas’ contribution to ESD. Each circle represents the three teaching dimensions of that particular subject area, and the overlap of the circles represents where the subject groups meet and address the same issues. The science and social science subject areas can collaborate in ESD teaching by means of curricular commonalities and ESD teaching traditions (segment IV). The scientific focus on facts (I) is an emphasis on the what-dimension. Social science teachers contribute political/ethical perspectives and the development of abilities in frequently used group discussions, which is an emphasis on the how-dimension (II). Individual action competence and the political nature of ESD issues, such as the ability to use knowledge in action to become a responsible democratic citizen, is enabled by a teaching that involves student participation, a how, through group work and discussion. Language teachers can offer an everyday view of ESD content with reading and writing tools that enhance collaboration (V). The important possible contribution of language is to offer possibilities for students’ personal development and identity-making (III), which is an emphasis on the why-dimension. The common aim for the subject areas is sustainability.

Unique contributions from each subject area

The science teachers primarily offered scientific facts, a what, that were mainly related to the ecological perspective, such as the consequences of energy use and production, eutrophication, radiation and global warming (I) (). The how was a transmissive type of teacher-centred teaching where science knowledge and abilities were the main aims. The purpose, why, was to teach students valuable knowledge that would automatically solve societal problems such as climate change. Social science primarily offered a what in the social perspective of ESD concerning social justice, international relations, politics, trade and peace. Social science also offered a how that differed from the teaching methods in science (II), for example through work on critical investigation and frequent group discussions about the consequences of climate change and social justice towards other people and cultures. The language teachers did not have a disciplinary ESD related content to offer from their teaching, although they often used common media content such as news and nature TV channels, a what, that was assumed to be close to students’ everyday lives. The teacher relation to ICT tools was twofold. The how was teacher-centred, where variation was a problem in that the ICT tools that were used could create major differences in students’ language skills. This made it difficult for teachers to keep up with the communication levels between the students in the classroom. However, ICT tools also created possibilities for teachers to connect the teaching to the world at large and gave students opportunities to practise communications with other cultures and to learn about differences in livelihoods. The main contribution to ESD from the language teachers was driven by their long-term purpose, the why-dimension, concerning students’ personal development. This enabled students to feel able and encouraged to participate in the general development of society (III).

Starting point for ESD collaboration - common contributions

The teachers from the science and social science subject areas could collaborate in ESD teaching by means of curricular commonalities and ESD teaching traditions. Both areas focused on the use of natural resources, energy production and environmental degradation (segment IV) (). Language teachers offered an everyday view of ESD content, such as recycling, healthy food and lifestyle issues. A common contribution starting in the subject area tradition was the offer of reading and writing tools that enhanced the ESD collaboration for all three subject areas (V).

Beside the commonalities, each subject area had a specific ESD focus and was thereby able to contribute to and complement each other through the content, methods, purposes and ESD perspectives that were used, as in collaborative teaching. Such cross-curricular settings offered students facts, opportunities to develop abilities through knowledge in action and support personal empowerment.

Discussion

The discussion starts by pointing to the relevance of cross-curricular ESD teaching to enhance action competence development. It further elaborates the different ways in which subject area teachers can work outside their disciplinary boundaries. Finally, the potential possibilities for cross-curricular teaching by teacher teams are discussed.

Cross-curricular teaching

The results show that there is a great potential for collaborations between teachers from the three different subject areas. Science and social science teachers seem to be able to work close together on a relevant ESD content that is supported by the core content in the curriculum, and that language teachers can offer important complementary media perspectives. The main contribution from the language area (mainly second language teaching) is the development of students’ communications and identity-making, both of which are crucial parts of ESD teaching (Jensen Citation2000). This is implicated by the language teachers’ focus on the object of care, the why-dimension, which is concerned with students’ personal development. Student centred teaching, or Dewey inspired progressivism, which places the student in an academic subject, is an important part of the teaching in the Nordic countries and is considered as a prerequisite for becoming an informed citizen (Oftedal Telhaug, Asbjørn Mediås, and Aasen Citation2006). In the case of language teachers, the learning outcome is student-centred. However, in the study it became clear that the language teachers’ teaching was also teacher-centred. This was also the case for the science teachers. All the teachers who took part in this Swedish study are presumably, in an international comparison working traditionally in a student-centred context, although the balance between student-centred teaching and learning outcome became most visible in the language teachers’ discussions about their contributions to ESD. This student-centred learning outcome on personal development is an important result of this study.

The large-scale quantitative study by Borg et al. (Citation2012) showed that all the three subject areas that are investigated in this study work in different teaching traditions. The results of our study show that ESD I is mainly promoted by science teachers, while ESD II is stressed by social science teachers and aligns with the discussion about ESD I and II complementing each other according to the yin & yang principle (Vare and Scott Citation2007a). The ESD I approach is more focused on behavioural change and according to Gress and Tschapka (Citation2017) needs to be complemented by an ESD II approach focusing on key competences and ‘narratives of empowerment’. In the process of developing action competence amongst students of sustainability, Jensen (Citation2002) suggests that self-esteem and self-confidence, which in this study are promoted by language teachers, should also be included as teaching goals. Hence, in this study the possible contributions from the subject area of language to students’ personal development and identity-making could be very important. In cross-curricular ESD teaching language teachers complement the ESD I and ESD II approaches stressed by the two other subject areas. This could be part of an ESD III approach as discussed by Vare and Scott in the early development of ESD approaches (Vare and Scott Citation2007b). In that way, this study also contributes to the possible development of ESD theory.

Weak ESD subject area framing enables more perspectives

In their group discussions the science and social science teachers discuss and respond comfortably about ESD teaching. They are confident about the curriculum content and the experience of teaching sustainability in their subject areas when addressing the what-dimension. In contrast, the language teachers are initially hesitant about their role in ESD teaching and need time to reflect on their contributions to ESD. In the group discussions first language teachers (who also teach a second language) mainly focus early in the group discussions on their role as facilitators in science and social science collaborations. They describe themselves as tools for reading information, writing articles, looking for information and making presentations on ESD issues. They do not really see how they can contribute to ESD teaching, although at the same time they do mention more diverse ESD content than the social science teachers. Language teachers often start ESD discussions in ecology about recycling, but also issues related to the economic perspective such as consumption supporting the development of personal image and lifestyles in social media. The language teachers also discuss issues that are communicated through the media on climate change, recycling and organic healthy food.

These findings are in line with two large-scale inquiry studies conducted with over 3000 upper secondary school teachers (Borg et al. Citation2012; Citation2014). The most pronounced subject-bound difference in these studies is that social science teachers recognise the ecological perspective (e.g. maintaining biological diversity and sustainable ecological processes and resiliencies) less than language teachers (Borg et al. Citation2014). Language teachers associate the economic perspective with SD to a greater extent than science and social science teachers, and the social perspective more than science (ibid.). The language teachers’ emphasis on the social perspective is important, in that in this study language teachers address this perspective to include identity-making and self-esteem. Social science teachers mention ecological issues in this study, but the focus is on the social perspective and the conduct of teaching emphasising the students’ development of generic ESD abilities.

When the science and social science teachers mention consumption related issues in the economic perspective they are more sceptical and negative than language teachers of the interests behind this type of thinking, particularly with regard to status and development. This is also supported by earlier research, which shows that science and social science teachers are not very concerned about this perspective. In contrast, when economic growth is mentioned the language teachers are more positive (Borg et al. Citation2014). This can be understood as language teachers being part of the discussions at a societal level through media coverage, where economic growth is part of the media discourse, while science and social science teachers are rooted in critical traditions within the subject areas (Hess Citation2002; Munby and Roberts Citation1998). In the light of those results, this study support the relevance of including the subject area of language in ESD due to secondary language teachers’ contributions to the economic perspective. The result of identity making and self-esteem, both of which are important in cross-curricular teaching on ESD has not been identified in previous large scale studies (Borg et al. Citation2012; Citation2014).

Stables and Scott (Citation2002) argue that only the most highly motivated teachers engage with ideas or frameworks outside their own disciplines. This can explain why closer collaborations between science and social science teachers are more likely to occur. Both subject areas are familiar with ESD from a knowledge perspective within their subject curricula, although language teachers do not really see themselves as part of this type of cross-curricular collaboration. In this study, the language teachers’ sense of a lack of relevance of ESD teaching gives the subject area a weak framing (Bernstein Citation1999) of the content through which a media view of SD can dominate and replace the subject tradition. This means that language can offer a broader view of SD than science and social science, both of which are more limited by their subject traditions. A weaker framing of the subject area in relation to ESD teaching also means that language teacher groups can embrace more perspectives. Science and social science can offer deeper and more critical perspectives, which from a student perspective may need to be complemented by a public media view of SD. In that way language teachers might link different ESD perspectives and especially provide a link between the societal discourse through the media of ESD to more critical standpoints such as those provided by science and social science teachers who are rooted in their disciplinary traditions. For example, Summers et al have shown that science teachers have a relatively narrow understanding of ESD (Summers, Corney, and Childs Citation2004).

The results of this study show that the different subject areas can complement each other in the cross-curricular teaching of ESD. They also show that the teachers of these subject areas seem to transform (Gericke et al. Citation2018) ESD differently into a teaching practice. For example, the science and social science teachers seem to transform aspects of ESD according to their scholarly disciplinary traditions, i.e. science teachers on science facts and social science teachers on the dichotomy between individual responsibility (action competence) and political responsibility, whereas the language teachers seem to transform ESD directly from the media, i.e. from a non-disciplinary discourse. Based on these findings, we argue that these different perspectives in combination have a greater potential to provide a holistic ESD in a collaborative cross-curricular teaching than would be the case if ESD is only taught in one or two subject areas independently.

Conclusion

This study aligns with other studies of cross-curricular settings in the sense that a number of trade-offs need to be considered at the school level (Applebee, Adler, and Flihan Citation2007). Science offers a scientific grounding of facts, and social science is important for repoliticising a policy level ESD used in curricula (Sund and Öhman Citation2018). In working with communicative democratic skills to develop an ESD action competence, students’ self-esteem and self-confidence should not be neglected or forgotten (Jensen Citation2002). In the process of cross-curricular ESD teaching, students’ individual identity-making is important and can help to make ESD knowledge relevant in students’ everyday use of and contributions to a more sustainable future. This could be language teachers’ important contribution to a cross-curricular collaborative work on ESD. According to Celce-Murcia regarding second language teaching (1991), the process of self-realisation and relating to and communicating with other people are two common teaching purposes. These two teaching purposes, or the why, can complement science and social science teaching. This complementation also applies to some differences in the what, due to various emphases on the three ESD perspectives (ecological, social and economic). The how shows differences in the use of group work in the classroom and in the practice of participatory collaboration approaches in the surrounding society. The results from this exploratory study show that the three subject areas complement each other well and emphasise the three dimensions of teaching that we have highlighted (the what, how and why), differently (). In short, each subject area has the potential to make significant contributions in collaborations to develop ESD in cross-curricular teaching teams.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by ROSE (Research On Subject-specific Education), Karlstad University and the Swedish Institute for Educational Research (grant 2017-00065).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Per Sund

Per Sund is a docent in science education at the department of mathematics and science education at Stockholm University, Sweden. He is also a Research fellow at Karlstad University 2017-2020. Per’s research interest is science education and environmental and sustainability education from a teacher’s perspective. He is involved in several research projects, including Research on subject education, ROSE. He is the former the link-convenor (2013-2017) of the Environmental and Sustainability Education Research Network, ESER (no: 30) collaborating within the European Educational Research Association, EERA. Per trains teachers and student teachers at national and international level.

Niklas Gericke

Niklas Gericke is professor in science education and Director of the research center SMEER (Science, Mathematics and Engineering Education Research) at Karlstad University in Sweden, and guest professor at NTNU in Trondheim, Norway. His main research interests are biology education and sustainability education. Much of his work relates to how the disciplinary knowledge is transformed into school knowledge and what impact these transformations have on teachers’ work and students’ understanding.

References

- Applebee, A. N., M. Adler, and S. Flihan. 2007. “Interdisciplinary Curricula in Middle and High School Classrooms: Case Studies of Approaches to Curriculum and Instruction.” American Educational Research Journal 44 (4): 1002–1039. doi:10.3102/0002831207308219.

- Bernstein, B. 1999. “Vertical and Horizontal Discourse: An Essay.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 20 (2): 157–173. doi:10.1080/01425699995380.

- Borg, C., N. Gericke, H. Höglund, and E. Bergman. 2012. “The Barriers Encountered by Teachers Implementing Education for Sustainable Development: Discipline Bound Differences and Teaching Traditions.” Research in Science & Technological Education 30 (2): 185–207. doi:10.1080/02635143.2012.69989.

- Borg, C., N. Gericke, H. Höglund, and E. Bergman. 2014. “Subject-and Experience-Bound Differences in Teachers’ Conceptual Understanding of Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 20 (4): 526–551. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.833584.

- Breiting, S. 2000. “Sustainable Development, Environmental Education and Action Competence.” In Critical Environmental and Health Education, edited by B. B. Jensen, K. Schnack, & V. Simovska, Vol. no 46, 151–166. Copenhagen: Research Centre for Environmental and Health Education. The Danish University of Education.

- Bryman, A. 2015. Social Research Methods. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

- Celce-Murcia, M. 1991. “Language Teaching Approaches: An Overview.” In Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, edited by M. Celce-Murcia. Boston, Massachusetts: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

- Dewey, J. 1916/1999. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: Free Press.

- Drake, S. 1998. Creating Integrated Curriculum: Proven Ways to Increase Student Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc.

- Education, S. N. B. o. 1980. Lgr 80, Läroplan för grundskolan [Curriculum for Compulsory School]. Stockholm: Liber Utbildningsförlaget.

- Education, T. S. N. A. f 2002. Sustainable Development in School. In. Retrieved from http://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=925

- Education, T. S. N. A. f. 2011. Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the leisure-time centre 2011 In. Retrieved from http://www.skolverket.se/2.3894/in_english/publications

- Eilam, E., and T. Trop. 2010. “ESD Pedagogy: A Guide for the Perplexed.” The Journal of Environmental Education 42 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1080/00958961003674665.

- Flores, J. G., and C. G. Alonso. 1995. “Using Focus Groups in Educational Research.” Evaluation Review 19 (1): 84–101. doi:10.1177/0193841X9501900104.

- Gericke, N., L. Huang, M. C. Knippels, A. Christodoulou, F. Van Dam, and S. Gasparovic. 2020. “Environmental Citizenship in Secondary Formal Education: The Importance of Curriculum and Subject Teachers.” In Conceptualizing Environmental Citizenship for 21st Century Education, edited by A. Hadjichambis, vol 4, 193–212. Environmental Discourses in Science Education. Cham: Springer.

- Gericke, N., B. Hudson, C. Olin-Scheller, and M. Stolare. 2018. “Powerful Knowledge, Transformations and the Need for Empirical Studies across School Subjects.” London Review of Education 16 (3): 428–444. doi:. doi:10.18546/LRE.16.3.06.

- Giddings, Bob, Bill Hopwood, and Geoff O'Brien. 2002. “Environment, Economy and Society: Fitting Them Together into Sustainable Development.” Sustainable Development 10 (4): 187–196. doi:10.1002/sd.199.

- Gress, D., and J. Tschapka. 2017. “Bridging Geography and Education for Sustainable Development: A Korean Example.” Journal of Geography 116 (1): 34–43. doi:10.1080/00221341.2015.1119874.

- Hess, D. E. 2002. “Discussing Controversial Public Issues in Secondary Social Studies Classrooms: Learning from Skilled Teachers.” Theory & Research in Social Education 30 (1): 10–41. doi:10.1080/00933104.2002.10473177.

- Hesselink, F., P. P. van Kempen, and A. Wals. 2000. ESDebate - International Debate on Education for Sustainable Development. Gland, Switzerland: The World Conservation Union

- Hopkins, C. 2012. “Twenty Years of Education for Sustainable Development.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 6 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1177/097340821100600101.

- Hopmann, S. 2007. “Restrained Teaching: The Common Core of Didaktik.” European Educational Research Journal 6 (2): 109–124. doi:10.2304/eerj.2007.6.2.109.

- Hudson, B. 1995. Group Work with Multimedia in the Secondary Mathematics Classroom. (Doctoral), Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom.

- Jensen, B. B. 2000. “Participation, Commitment and Knowledge as Components of Pupils’ Action Competence.” In Critical Environmental Education and Health Education, edited by B. B. Jensen, K. Schnack, & V. Simovska, Vol. 46, 219–238. Copenhagen: Research Centre for Environmental and Health Education. The Danish University of Education.

- Jensen, B. B. 2002. “Knowledge, Action and Pro-Environmental.” Environmental Education Research 8 (3): 325–334. doi:10.1080/13504620220145474.

- Jickling, B., and A. E. J. Wals. 2008. “Globalization and Environmental Education: Looking beyond Sustainable Development.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 40 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/00220270701684667.

- Klafki, W. 1995. “Didactic Analysis as the Core of Preparation for Instruction (Didaktische Analyse Als Kern Der Unterrichtsvorbereitung).” Journal of Curriculum Studies 27 (1): 13–30. doi:10.1080/0022027950270103.

- Kvale, S., and S. Brinkmann. 2009. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. “Situated Learning.” Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press

- Lijmbach, S., M. M. van Arcken, C. S. A. van Koppen, and E. J. Wals. 2002. “Your View of Nature is Not Mine!’: Learning about Pluralism in the Classroom.” Environmental Education Research 8 (2): 121–135. doi:10.1080/13504620220128202.

- MacMath, S. L. 2011. Teaching and Learning in an Integrated Curriculum Setting: A Case Study of Classroom Practices. (Doctor of Philosophy), Toronto: University of Toronto.

- McPhail, G. 2018. “Curriculum Integration in the Senior Secondary School: A Case Study in a National Assessment Context.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 50 (1): 56–76. doi:10.1080/00220272.2017.1386234.

- Mishler, E. G. 1986. Research Interviewing: context and Narrative. London, UK: Harvard University Press.

- Mogensen, F., and K. Schnack. 2010. “The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourse of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/13504620903504032.

- Munby, H., and D. Roberts. 1998. “Intellectual Independence: A Potential Link between Science Teaching and Responsible Citizenship.” In Problems of Meaning in Science Curriculum, edited by D. Roberts & L. Östman, 101–114. NY: Teachers College Press.

- Nikel, J. 2005. Ascribing Responsibility: A Study of Student Teachers’ Understanding(s) of Education, Sustainable Development, and ESD. Bath: University of Bath.

- Oftedal Telhaug, A., O. Asbjørn Mediås, and P. Aasen. 2006. “The Nordic Model in Education: Education as Part of the Political System in the Last 50 Years.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 50 (3): 245–283. doi:10.1080/00313830600743274.