Abstract

Early Childhood Education in general, and Early Childhood Education for Sustainability in particular, have dominantly relied on an ontological framework that privileges children’s agency. This paper challenges this dominant narrative by attuning to the everyday ways in which children are moved by the weather within a multitude of weather assemblages. It attempts to illustrate how ‘learning’ could be achieved when bodies come in relation with, and are able to be affected by, other bodies. Drawing on ideas from post-qualitative research orientation that highlights weather-generated data, the paper elucidates how the weather acts on and comes into relation with humans and non-human bodies. It contends that noticing and engaging with the vitality of weather offers possibilities for creating affects and that this potentially leads to an attunement towards ecological sensibility. Notions such as ‘vital materiality’ and ‘lively assemblages’ are discussed as a possibility to go beyond an anthropocentric understanding of the weather, which could pave the way towards a more relational ontology as a basis for emphasizing human’s ‘inter and intra-dependence’ with non-human nature, and hence, arguably, sustainable living.

Introduction

The recognition of the link between environmental education and early childhood education (ECE) began with the belief that the foundation for life-long attitudes and values for pro environmental behaviour are laid down during the earliest years of life (Carson Citation1965; Tilbury Citation1994; Wilson Citation1992). Ever since, several approaches have been employed to involve and engage children with environmental and sustainability issues. Some of these include: the knowledge-based approach (Tilbury, Coleman, and Garlick Citation2005); the immersive learning approach influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s classical work which promotes children’s learning in ‘nature’ (Rousseau Citation1979); the political dimension of environmental education influenced by Paulo Freire’s critical theory; and more recently, the notion of participation, children’s agency and their ability to experience and critically engage with environmental and sustainability issues (Arlemalm-Hagser and Davis Citation2014; Caiman and Lundegård Citation2014; Davis and Elliott Citation2014). Although the aforementioned four approaches have positively impacted environmental education for multiple decades, they have not challenged the essentialist ontological assumption that separates the child from the non-human nature. The ontological and epistemological premises of these approaches solely rely on human agency and subjectivity (i.e. emphasize the intentional, conscious and learning child subject), and disregard the agentic characteristics of non-living matter and forces.

In this paper, I seek to challenge this ontological separation by noticing the agentic power of the weather and how it affects other agentic human and non-human bodies within an assemblage. I use Bennett’s notion of vitality and lively assemblages (Bennett Citation2010) to refute this separation and relocate the power of the weather within mobile sets of relations. The paper explores the idea that early childhood pedagogy can benefit from recognizing and engaging with the vitality and agentic characteristics of the weather. In doing so, I explore ECEfS (Early Childhood Education for Sustainability) pedagogies that might emerge when we recognize and shift the focus from the individual human child cognitively learning ‘about’ the weather from a distance, to children learning to be affected by the weather within lively weather-child assemblages.

I locate my study within new materialist (Bennett Citation2010) thinking with a particular focus on Bennett’s (Citation2010) notion of vital materiality. While doing so, I duly acknowledge earlier studies that inspire and influence my conceptual engagement with the vital materiality of weather and its relationship with other human and non-human bodies. These studies (Rooney’s in particular) have laid the conceptual foundation which has paved the way for this study to expand the theorization of weather by adding rich empirical narratives on the basis of children’s everyday encounters with the weather. These earlier conceptualizations include: rethinking climate as entanglement (Verlie Citation2017); the notion of weathering (Neimanis and Walker Citation2014); immersion in the influx of weather (Ingold Citation2010); and children’s relationship with the weather (Rooney, Citation2018a). In particular, by providing further empirical narratives, the study builds on two recent early childhood studies (Rooney Citation2018a, Citation2018b) that highlight the significance of children’s relationships with the weather and its significance for environmental pedagogy.

This paper draws on ideas from post-qualitative thought, particularly (Nordstrom Citation2015) concept of data assemblage, which allows for the de-centring of the human child as an object of inquiry. Doing this has helped me recognize and attune to the agentic characteristics of the weather as it comes in relation with humans and non-human bodies and creates affects within an assemblage. Drawing on weather-generated data (i.e. the affects created/induced by the weather), I indicate how weathering forces interact with other vital bodies in lively weathering-child assemblages, in a Swedish preschool. The particular group I focused on consisted of sixteen children and three teachers who granted me their consent to join and follow them, take notes and record different encounters. Children’s consent was obtained both through parents’ signature on a consent letter as well as the children’s own willingness to let me join the group.

The article is organized as follows. In the first section, I offer a brief overview of previous studies and approaches to weather within ECE. In the second section, I conceptualise weather as a vital force, a lively actant that constantly comes into relation with bodies forming an assemblage and creating affects, enmeshed with bodily feelings, emotions, memories and imaginations. This section also outlines the key concepts I use and connects weather with (Bennett Citation2010) notion of vitality and lively assemblages. The third section presents ideas from post-qualitative inquiry and the concept of data assemblage (Nordstrom Citation2015), which indicates how weather generated data emanated from a mundane bodily encounter with the weather. The subsequent section offers weather encounter vignettes with their description and analysis. In the conclusion, I suggest the need to utilize the untapped pedagogical possibilities in shifting from learning about the weather, as something external and separate to us, to learning with lively weather-child assemblages.

Approaches to weather within ECE

Weather has been approached in various ways in early childhood education. For instance, relationships among various meteorological conditions, affective states and behavior in young children (Lagacé-Séguin and d’Entremont Citation2005), outdoor play space and the weather (Ergler, Kearns, and Witten Citation2013), weather and how it shapes preschool pedagogical routine (Hatcher and Squibb Citation2011), children’s understanding and misconception of the weather and physical science (Henriques Citation2002) and learning weather as part of understanding natural science (Inan, Trundle, and Kantor Citation2010). Apart from these research orientations, a widely employed practical approach has been to address weather through structured pedagogical activities.

The aforementioned approaches consider weather as either a condition for different activities or as something external that we can learn about, i.e. as part of natural science. None of these studies highlight the entanglement of weather and children. Notable exceptions are Rooney’s (Citation2018a, Citation2018b) two key articles on weather, which have both laid the conceptual foundation and served as a springboard for this paper. By drawing on (Ingold Citation2010) conceptualisation of ‘weather-worlds’ (Rooney Citation2018a), highlighted human-weather entanglement and how children learn with the weather and the pedagogical significance of child-weather relations. She argued that children’s affective and sensory encounters with the weather have the potential to offer new insights and a pedagogical basis for addressing climate change in early childhood education without being limited by anthropocentrism (Rooney Citation2018a). While emphasizing the need to build connection with places, she argued for new possibilities for environmental education that pays attention to more-than-human encounters (Rooney Citation2018a). However, as Rooney (Citation2018a) points out, the weather in ECE is generally approached in a limited and reductionist manner.

In her second article, Rooney (Citation2018b) employs a walking ethnographic methodology and explores the various ways children engage with the weather and the potential of such engagement for revealing wider human-weather entanglement. Drawing on empirical cases of child-weather entanglement, the study shows how attending to the diverse range of more-than-human lifetimes and scales that the children encountered, offers alternative modes of responding/attentiveness to the environment (Rooney Citation2018b). She argues that by paying attention to the elemental effects of weather, through bodily and affective encounters, a foundation can be created for open attentiveness in responding to human-induced climate change now, and into the future (Rooney Citation2018b).

Rooney’s work is situated within Ingold’s (Citation2010) conceptualisation of a ‘weather-worlds’ framework and highlights weather as an inevitable part of children’s entangled relations with the wider environment. Taking Rooney’s work further, I take an ontological departure and highlight the agentic characteristics of the weather, its enmeshment with bodies, both human and nonhuman, its entanglement with imaginations, inherited discourses and its invoking of affects and particularly its relations with human and non-human bodies within assemblage thinking. In doing so, I draw on Bennett’s theorization of vital materiality and focus on the ways in which its agency (weather as an actant) is manifested within the encountered child-weather assemblages. This leads to a reconceptualization of weather assemblage pedagogy and the learning spaces it creates by serving as a catalyst for bodies to be affected differently by other bodies. While Rooney emphasized the pedagogical significance of learning with the weather, I expand this concept and empirically explore possibilities for the ‘learning’ that might happen when bodies become affected by and intermingled more bodies than they were before.

Re-conceptualizing weather as assemblage

Despite being an everyday topic that we use continuously (at home, work, traveling or at a bus station), weather is an under-theorized and under defined term. Gibson (1979) as cited in Ingold (Citation2007, 532) describes it as being how ‘the atmospheric medium is subject to certain kinds of changes that we call weather’. In a broader sense, weather refers to the wider planetary system of dynamic, interactive elements and atmospheric forces that constantly shape and reshape the surface of the earth and its inhabitants (Grady Citation1999; Vannini et al. Citation2012). As it is a ubiquitous force, we are always both with the weather and in the weather; it surrounds us and we are nested in it. Yet nevertheless, weather is not something outside us- humans interact with it, help form it though our actions, attend to particular aspects of it humans become mingled with and enmeshed with the weather as inseparable parts of a ‘weather-world’ (Ingold Citation2007).

Being a dynamic phenomenon, it constantly changes its pattern and manifests itself in a multitude of elemental characteristics such as rain, thunder, storm, heat, wind, etc. Given its active, lively and agentic characteristics and its inevitable presence in every sphere of life, it is essential to be ecologically sensitized and attuned to the scale, significance and force of weather and the process of weathering. Weathering, having a time element, is a term that refers to the active, agentic and lively characteristics of the weather as it brings about physical changes. Ingold (Citation2015, 71) defines weathering as, ‘what things and persons undergo on exposure to the elements’. Yet Rooney (Citation2018a, 182) argues that, ‘time is co-constituted; shaped or made through ongoing weather encounters…’ so that, ‘we understand ourselves as implicated in the weathering of the world – something we cannot extract ourselves from’. Weather is decidedly not just an exterior buffeting us and containing us, but is also something we actively contribute towards, both in terms of human influenced climate change (carbon emissions) and also something with which children are emotionally invested. ‘Weather is often intimately entangled with the way the children engage in the worlds and times of other species’, (Rooney, Citation2018b, 185). ‘Space’, as Gannon contends (Citation2016, 78), ‘is not inert and empty but animate, animating, always a lived and living space’.

Despite Rooney’s (Citation2018a) work that highlights human-weather entanglement, how to understand and engage with the vibrancy of weather and how to learn to be affected by it is a less explored/theorized subject in the school context at large and in ECE in particular. Scholars in other fields have highlighted weather as a phenomenon that is entangled with every sphere of life and humans’ everyday activity. Neimanis and Walker (Citation2014) argue that weather is not just ‘a thing’ but an experience: something we intimately ‘do’ daily, as an embodied experience. Ingold (Citation2011, 115) indicates that humans are not related to the bigger climate in a ‘closed objective form’ but rather through their ‘common immersion’ in the generative fluxes of the weather-world. Moreover, a situated place study by Gannon (Citation2016) elucidates humans’ enmeshed relationship with other matter and forces indicating that affective attunement to everyday weather has potential for building a sense of place in our local neighborhood. Gannon’s work particularly influences my thinking about the affective aspects of weather.

Thinking through Bennett’s notion of vitality materiality, I consider weather as vital force, a lively actant, which is everywhere, all the time, albeit not as something wholly external to humans-we also, along with other bodies and forces, make the weather. Bennett offers a critique of the traditional understanding of matter which considers non-living matter as passive and lifeless entities that simply await and receive action and direction from agentic and rational humans (Bennett Citation2010). Vitality refers to ‘the capacity of things-water, storms, land, flora, fauna, and the elementals in all their permutations to impede or block the will and designs of humans and to act as agents with forces, intentionalities, propensities or tendencies of their own’ (Bennett Citation2010, 2). Thus, Bennett argues that non-living materials are vital and lively and have the power to act, create affect/effect, alter the course of events, and hence make a difference in the world. While characterizing the vitality and agency of non-living matter, she borrows and builds on Latour’s notion of an actant within an assemblage, i.e. a non-human actor.

Of course, Bennett is not merely reverting to ‘a vitalism in the traditional sense’ (Bennett Citation2010, pxiii), but acting against a tendency to see the material as, ‘detach [ed] … from the figures of passive, mechanistic’ (Bennett Citation2010, xiii), to ‘turn the figures of “life” and “matter” around and around, worrying them until they start to seem strange’ (ibid, vii), to ‘emphasize, even overemphasize, the agentic contributions of nonhuman forces (operating in nature, in the human body, and in human artifacts) in an attempt to counter the narcissistic reflex of human language and thought’ (ibid, p xvi).

Bennett points out that vital materiality isn’t within each separate actant, but is a relational ‘swarm of vitalities at play’ (Citation2010, 32). The agency is distributed and it swarms, or intensifies when bodies, forces, materialities come together in an assemblage. Bennett explains that all actants within the swarm are agentic with their own unique efficacy, trajectory and causality. Efficacy, for Bennett, refers to ‘the creativity of agency, to a capacity to make something new appear or occur’ (ibid, 31). ‘A body’s efficacy or agency always depends on the collaboration, cooperation, or interactive interferences of many bodies and forces’ (ibid, 21). Trajectory refers to an agent’s ‘directionality or movement away from somewhere even if the toward-which it moves is obscure or even absent’ (ibid, 32), and causality refers to the ‘contingent coming together of a set of elements’ and bodies (ibid, 34).

Drawing on Deleuze and Guattari and Latour’s notion of assemblage, Bennett introduces the notion of ‘agency of the assemblage’ (ibid, 20), which sees agency beyond the moral human subject and highlight its distributive nature across a swarm of simultaneous actants and vital materialities. Hence, Bennett’s notion of agency ‘does not posit a moral subject as the root cause of an effect’ (ibid, 31), but rather a collection of actants and bodies within lively assemblage. She defines an assemblage as ‘an ad hoc grouping of diverse elements, of vibrant materials of all sorts’ which helps us to understand agency ‘as a confederation of human and nonhuman elements’ and bodies (ibid, 23). She argues that we humans are in an inextricable enmeshment with this web of forces that she describes as an assemblage.

Bennett argues that assemblages are constituted of affective bodies, which she describes as ‘associative bodies within an assemblage which are continuously affecting and being affected by other bodies while entering a relationship, an assemblage’ (ibid, 21). As highlighted by her, ‘the more kinds of bodies with which a body can affiliate, the better. As the body is more capable of being affected in many ways and of affecting external bodies…so the mind is more capable of thinking. Therefore, bodies enhance their power in or as a heterogeneous assemblage’ (ibid, 23).The notion of affective bodies has informed me to look into the affect created within weathering-child assemblage and the thinking it might provoke.

As indicated above, scholars approached weather differently. Neimanis and Walker (Citation2014) highlighted humans’ embodied experiences and relationships with the weather while Ingold (Citation2011) and Gannon (Citation2016), respectively highlighted the affective and emplaced relationship with the weather. Thinking through the intersection between the weather and Bennett’s notion of vitality and lively assemblages has helped me to extend and reconceptualize the ongoing child-weather relationships at the preschool. In doing so, I see weather as a constitutive vital force acting within a human-non human assemblage (Bennett Citation2010). This conceptualisation allows me to see child-weather relationships beyond the limits of only ever thinking about the agentic child, but rather enmeshed within lively assemblages of agentic forces and bodies. Besides, Bennett has reminded us that whether we recognize/experience it or not, the force of matter (e.g. weather) exists, and can and does thwart human intentional agency, such that humans are enmeshed with it as one part inseparable from the whole.

Data assemblage

Drawing on ideas from post-qualitative thought, I use Nordstrom’s (Citation2015) concept of data-assemblage which allows me to assemble data from different weather encounters and weather-generated vignettes. As pointed out by Nordstrom (Citation2015), ‘Data assemblage is a dynamic onto-epistemological entity in which the constitutive lines open up new ideas of thinking about data in a study and what that data can do and become’ (p.166). One way of carrying out a post-qualitative inquiry, as indicated by St. Pierre (Citation2018, 9) is to ‘begin with the fortuitousness of the encounter (not with method) that guarantees the necessity of what it forces us to think’. My inquiry began with the data that emerged from my random bodily encounter with a rain shower in a stormy morning which elicits and lends itself to the emergence of multiple other forms of encounters and data.

While walking from the tram station to the preschool, I was encountered, caught, and confronted by the rain, which drenched me quickly. I wanted shelter but I was already late to join the preschool group. Having forgotten my umbrella, there was no alternative other than exposing myself to the brisk wind and the slanted rain that was trickling down my face. My hands were cold and my backpack was soaked. I lingered in the moment and needed more time to try to dry myself off before joining the group (Field Note, March 2017).

The aforementioned physical encounter with the weather becomes a pivotal point and agentially changed/influenced me, and eventually the research process as well. The weather continued pulling my attention which agentially formed the research project. As a post qualitative enquirer, at the outset of the research, I did not have a predefined non-human aspect to focus on. My broader interest was to explore how to engage and learn-with the agentic characteristics of the non-human world. I was only thinking with concepts (such as assemblage) while experimentally engaging with the world. Weather became a focus of inquiry as a result of the aforementioned encounter with a rain that produced affects in me and forced me to think.

The same morning, the topic of weather came up in the conversation among the children and the teachers in connection to an electricity problem in the preschool. During the conversation, Sofia (one of the 15 children in the group) was describing her encounter with the storm, the wind and the rain as she was walking to the preschool with her mother (see the story in the vignette below). I followed Sophia and shared the story of my own physical encounter with the weather. The topic of weather had continued to linger in my mind while nudging me to recall my previous engagement with the weather. My readings on weather (Rooney Citation2018a; Neimanis and Walker Citation2014; Howard Citation2013; Ingold Citation2011) and the weather workshop I attended, added an impetus. I was also drawn to the morning calendar routine which I did not pay due attention to and passed by during several visits to the preschool. These all emerging lines of thoughts agentially influenced me and I began to be attuned to and write/record different discursively and materially (bodily encounter) manifested weather vignettes.

In Bennett’s terms, the weather is seen as agentially influencing me in my choice of research, not by positing an intention to the weather but in terms of foregrounding a material effect as an important part of learning- both the learnings of preschool children and myself as a researcher- not as some annoying externality, to be tidied away and excised. Weather items continued to pile up and different forms of materially and discursively generated weather events entered the data assemblage. The assembled data formed a dynamic line of thought offering varieties of data (Nordstrom Citation2015).

Hence, attending to my own physical encounter with rain on a stormy morning rhizomatically, allowing a multiplicity of nonhierarchical influences, elicited different weather encounters which led me to think of ‘data as an assemblage’ (Nordstrom Citation2015, 167) of different forces: some human (children, teachers and myself) and some non-human (different elements of weather, slide/metal, flashcards, weather charts…etc.) which will be shown in the vignettes below. The vignettes presented below are narrative snapshots of the weather-child assemblages. Although the fieldnote captures the human position on weather as an external force, I tried to pay attention to and become attuned with the affects that the force of weather created in me, the children and other non-human bodies. The different vignettes are analyzed and discussed in light of the aforementioned (Bennett Citation2010) core concepts such as material vitality, ‘lively assemblage’, ‘distributed agents’, ‘swarms of vitalities’, ‘efficacy’, ‘trajectory’ and ‘causality’.

Vignette one: the storm

The rain and wind that I encountered on the stormy morning came up in the conversation among the children and the teacher. That day was not a typical day for the preschool. The electricity went off for a couple of hours and, as a result, the children had to come in from outdoor play for an early lunch so that they could eat the delivered food while it was still warm. Some children started asking why the electricity went off. This question led to a whole-class discussion on what made the electricity go off. The teacher put the question back to the children and they started to speculate. Sofia made a connection between the storm/thunder and the electricity:

‘I think it is the thunder that makes it go off. Me and my mummy were walking to school and we saw a storm. I was scared, my mum said it is thunder, it was super loud and there was lightning! Then we started running because it was windy and rainy. It was super cold and I got wet. Then we saw the rainbow’. Daniel, who came to school in his father’s car, joined the conversation and said: ‘I was sitting inside daddy’s car. I didn’t hear the thunder and didn’t see the light, but my dad saw lightning. I was only a little bit wet when I come out of the car and walked to the school’. Entering the conversation, and making associations with the vacation he had just taken, Max said: ‘I don’t like the thunder because it didn’t let me go on the plane. So, we told the thunder to stop. Then, when the thunder listened to us and stopped, we could go. So, the wind and the thunder make me feel sad’ (Field Note, March 2017).

The storm-preschool assemblage brings to life the discussion about the power outage. Within this assemblage, agency is distributed among the weather, teachers and children. The weather is altering the preschool routine, the teachers are also acting and navigating through the new condition and the children are also reacting to the situation verbally (through narratives and utterances of their present and past experience), affectively and physically (bodily movements).The storm disables the electricity, and the absence of electricity, in turn, brings about a change in lunch time. The storm ‘impede[s] or block[s] the will and design of humans and acted as agents’ (Bennett Citation2010, 2). While exercising its power, the storm messes with human ‘control’ (Bennett Citation2010) and disrupts the school routine, instead creating an alternative pathway for the day, i.e. eating lunch well before the school’s normal time. However, this effect is not a mere effect of the storm, but occurs in connection with the other actants: the electricity, the school, teachers and children.

The potency of the storm captivated the children and triggered a lively conversation with the teachers. The encounter made Sofia notice the agency of the storm and she associated it with the blackout. She figured out that the storm, which she attributed to the sound of thunder, can actually turn off the electricity and influence what is happening at the preschool, i.e. can thwart human control. As the trajectory (Bennett Citation2010) of the assemblage brings in time in a non-linear way, the children also started to remember the different things they did in the past. Thus the storm, as part of the weather, enters into the meaningful narratives of the children as something inextricably linked to fundamental aspects of their lives.

Moreover, the storm enlisted various affects in the children and adults, i.e. being scared, frightened in Sofia and sadness in Max. While being enveloped in the storm, Sophia had a multisensorial engagement with the wind, rain, thunder and lightning. As her narrative account brings her body into the assemblage, she indicates that she was walking, running, feeling scared, cold and getting wet, which highlights the bodily relationship with the different atmospheric elements. The capacity and power of her body are affected both in a decreasing (as she got soaked in the rain) and increasing (as she is urged to run) manner. Hence, the stormy morning and its whirlwind vitality produces different feelings and actions in and with Sofia. Indeed, the storm becomes a mnemonic and causative thread on which to hang the narrative of the day, something, as Gannon (Citation2016) writes, that ‘shapes … thinking, feeling, and being’ (78).

Shaping its own unique trajectory (Bennett Citation2010), the agentic weather brings about a response in Daniel and his father who alter their means of travel to the school. The weather had already formed a precondition for Daniel and his father to go to school by car so that they can mitigate the cold, rainy and stormy day. This indicates how the agentic power of the weather catalyzes humans to be agentic and creative modifiers of their environment through how we move and travel, Daniel’s day is mingled with the rain, altered, into ‘it makes’, him ‘other than [he] …would be elsewhere’ (Gannon Citation2016, 86).

The recounted storm experiences affected Max’s trip and created a feeling of sadness. Max made the connection with the agency of the storm and his life beyond preschool (e.g. vacation). Max recognized the power of the storm in preventing him from flying, but still held onto faith in human will to control it by re-establishing the supremacy of human agency. Yet despite this, Max ‘telling the thunder to go’, it remains a central and vivid part of the day in Max’s telling, something affective, ‘that makes me feel sad’, a reminder that they could have had to adjust their plans beyond a simple delay.

Daniel and Max’s case illustrates the weather’s agency and its ontological and epistemological implication for weather pedagogy, i.e. the need to learn how to be affected by the weather and the need to remain attuned to the affects it creates in/with us. Although it’s only a small example, the children powerfully and emotionally recount how thunder and rain affect their lives and this discussion can be opened up into a more general sense of what Ingold terms ‘becoming knowledgeable’. Knowledge is grown along the myriad paths we take as we make our ways through the world in the course of everyday activities, rather than assembled from information obtained from numerous fixed locations. Thus it is by walking along from place to place, and not by building up from local particulars, that we come to know’ (Ingold Citation2010, S121).

Vignette two: the hot slide

It was a warm day in May and the children were playing in the playground behind the preschool…. Some children wanted to use the slide, but the metal had become so hot from the sun, that they could not actually sit on it. The children were amazed and started shouting to friends to come and feel the metal. Captivated by the scenario, I felt the metal and it was indeed very hot. Noah knew and commented that it was the sun that heated the metal. The children began to come up with ideas on how they could still use the slide despite its hotness. Noah took off his fleece and wrapped it around his bottom so that he would actually come down the slide without being burnt by the heat. Tom was sliding on his shoes instead of sitting on his bottom, and other children continued doing the same as they came down the slide (Field Note, May 2017).

The interactive interference among the three affective bodies (Bennett Citation2010, 21): the children, the metal and the heat, are collectively coming together in their porosity producing different affects and effects. While exercising its agency and efficacy (Bennett Citation2010), the sun heated the metal which resulted in preventing the children from using the slide and forced them to creatively think of alternatives. The power of the sun thwarted humans’ design (Bennett Citation2010) and impeded the children’s will to go down the slide. This challenge caused by the heat prompted the children to problem-solve, which in turn provoked sensory response by the children, who adjusted their bodies differently in order to accommodate the heat.

The children are being affected within the material assemblage. A ‘swarm of vitalities’ (Bennett Citation2010, 32) from the sun, the slide, the children’s bodies, the shoes and the fleece come together with their porosity (Malone Citation2018) and create a different outcome. As the children’s bodies and the hot slide came into contact, a blockage caused by the radiation of vitalities (Bennett Citation2010) arising from the slide was experienced. The slide was ‘heated’ by the heat and as a result refused to be ‘slid’ down by the children, which implies that agency is shared and co-constituted by all the actors: the child, the heat and the slide. The efficacy of the hot metal creates a space for creativity by forcing the children to think of an alternative and remain resilient and come up with ‘strategies’ that would allow them to deal with the obstacle and go down the slide without being burnt. Hence, the heat, in collaboration with other affiliated bodies (the slide, the shoes, the children’s bodies and the fleece) has urged the mind to be creative. It offers the children a way of knowing that is based on being alive and acutely aware of changes in the environment, on the effects it has on their choices and their bodies.

As weather is a dynamic phenomenon that shifts in different time/space assemblage, the interacting bodies could have been produced differently if the children were all on the same slide in January during winter. Different affective bodies could have entered and existed in the assemblage. The children would have wanted different clothes and shoes, and the slide might have been frozen instead of being hot. So, in the above vignette, rather than the agentic child having an encounter with the heat and forming a relationship with it, or instead of perceiving the heat as the object of the conversation that can be experienced, assemblage thinking allows children to engage with it as an actant with its own thing power and agency. If the educators had recognized the agency of the weather, this point of encounter could possibly be expanded for pedagogical purposes and utilized as a teaching and ‘learning’ moment in an explicit manner. Yet, the implicit ‘learning’ and the affects produced are already in place albeit not being intentionally done by the teacher.

Vignette three: the sun-tanned girl

Sara (a white Nordic girl) just came back to preschool from vacation in Spain and was sharing her experience with her friends. The change (tan) in her face has captured her friends’ attention, and they commented on her ‘new’ appearance. Tom said: ‘You look like Natasha’. Natasha is an Indian girl with ‘colored’ skin. John wondered and asked: ‘Why are you like that?’ pointing towards Sara’s face. Sara explained that she and her family got tanned since it was too warm is Spain. She also said ‘it was sunny all the time and the sun makes “ouchy” in my eyes’…. (Field Note, May 2017).

As Sara’s body and the mediterranean sun simultaneously come together in their porosity, an effect and affect is produced as a result of a shared agency between the sun and Sara’s skin. While enacting its agency, the sun burnt Sara’s body and changed its colour, remaining imprinted and marked on the body, thus making agential to attract other children’s attention. The physicality of it extends the sensory mode into visual recognition of the sun’s agency. The vitalities arising from the sun also produced an affect by causing pain in Sara’s eye. These affect and effect are clear indicators of the material manifestation of the sun and the porousness and vulnerability of Sara’s body. It is the shared agentic interaction of Sara’s body with the sun that transforms the flesh and creates a new appearance which produced her in a different way in composition with some of the other children who are noticing the transformative effect of suntan.

This short narrative is offered again not as a definitive account of children’s experience or even a particular girl in a particular time. Her understanding and framing of the event may change after all, (her understanding as well as her skin may become weathered or time tempered). It is offered rather as an example of how our sense of the world and understanding can be opened up and questioned, disrupting the sense of otherness associated with ethnicity for example.

Even though the children notice the change in Sara’s skin colour, they do not automatically associate it with the sun. John’s question ‘Why are you like that?’ implies he is baffled and did not make the connection between the sun and her browner face. For John, who was not in Spain, and didn’t experience the sun’s heat, this assemblage has altered his conception towards a more general apprehension of the sun’s vital force. John and Tom do not have a clear visual recognition of the sun’s agency when they look at Sara’s burnt face. Thus, they interpret it differently until Sara explains and brings the sun into their consciousness.

However, the sun not only changes Sara’s skin colour, but also renders her identity as a Nordic white girl ambiguous. She has become more like an Indian girl. Hence, this weather-child assemblage produced racialized discourse indicating skin pigmentation (due to melanin production) as a cultural signifier not just a bodily change. The agency of the racialized discourses captivated John and Tom and even tend to obscure their understanding of the sun’s agency.

The assemblage triggers new production of knowledge through the discussion about the sunburn. It is the joint vital characteristics of Sara’s skin and the sun that bring about the tanned face which captured the children’s attention and became the topic of discussion among the children. When John asks why Sara’s face changes, she makes the connection with the sun. So, there is a point of learning that is happening in the space that was opened up as a result of the potency of the sun and the potency of racialized discourses. It is the intersection of both vitalities (one material and one discursive) that is potent. Besides, as (Bennett Citation2010) points out, it is the ‘interference’ between different bodies and forces that brings about the efficacy.

Although the preschool in focus incorporates weather activities in its structured curriculum, the agency of the weather-child assemblage, as described in the three vignettes above, is not being used for pedagogical purposes. The vignettes elucidate the distributed agency within weather-child assemblages and how children are always learning in their interaction with the elements. However, it is not evident that the educators are attuned to assemblage thinking and notions of generative distributed agency. Thus, there is a risk that this kind of learning remains unnoticed. There has been a nearly exclusively child-centric focus on formal and deliberate pedagogy instead of opportunities to open up the children’s understanding to how human bodies are inextricably linked to climate and material forces-whether this is heat from the sun, amount of pollutants in the air, or the rising of sea levels or any other number of factors. By these means, children’s and adults’ day-to-day living, breathing, thinking, dreaming and interacting can become entangled with a greater whole that of the earth and its ecosystem, opening new ways of learning. One notable traditional weather pedagogy used at the preschool is during the so-called ‘calendar time’, described in the vignette below.

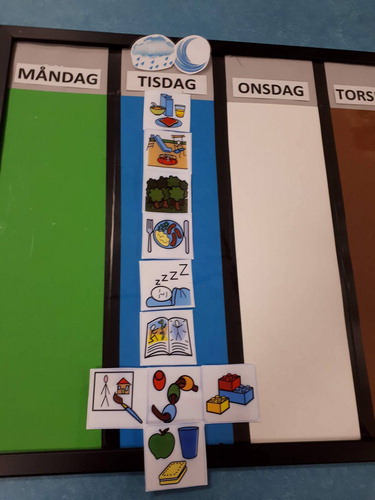

Vignette four: the weather calendar routine: regulated weather encounter

The group nominated Jack as ‘the weather person’ for the day. The teacher asked him to go to the window and see what the weather looks like outside. Jack walked to the window and looked outside. He came back to the circle and told the group that it was rainy and windy. Jack picked the ‘rainy’ and ‘windy’ flash cards and put them up on the weather chart. Sara said it was a bit foggy and insisted on adding the ‘foggy’ flash card. However, the children and the teacher discussed as a group and agreed not to add the foggy flashcard. The group sang the ‘what is the weather like today’ song as a group. They continued to talk about what kind of clothes they need and where to go and play outside. (Field Note, March 2017).

The calendar routine is a major part of the daily morning pedagogical routine, where teachers and children sit in a circle and carry out a range of activities which include: making observations about the weather; teaching children about science of weather by classifying and recording it; discussing the daily weather; and singing and reading about the weather and the seasons in general. While the calendar time activity takes place inside, ‘the weather’ is located as something outside that children can learn about it and actively construct their meaning (cognition) from a distance. The children have to look through the window to see ‘the weather’. The activity is done with the help of a Weather Chart (see below) and different flash cards representing different types of weather. As indicated in below, two flash cards: ‘rainy’ and ‘windy’ were chosen to represent the weather on that particular Tuesday. It was not always easy for the class to agree on the classification representing the day’s weather. That Tuesday, Sara insisted on adding the ‘foggy’ flashcard in addition to the ‘windy’ and ‘rainy’ cards indicated. However, it was what the majority of children agreed on, as reconciled by the teacher, that was put on the chart.

The activity imposes order on the weather as an elemental force that is beyond our control (Bennett Citation2010) and gives a sense of mastery and control over it (Strengers and Maller Citation2017) by knowing it from a distance. This approach is human-centric and solely focuses on human agency, which unintentionally reinforces the human-weather divide. In doing so, it externalizes the weather and thus perpetuates the false nature/culture divide by implying that weather is something happening ‘out there’. However, as we humans are immersed in the influx of weather (Ingold Citation2010); there is no discrete easily demarcated outside to weather as it is a massive force that we are inevitably nested in. The children are having direct bodily experiences with the elements, albeit mediated through human structures and technologies (i.e. indoor/shelter and heating). However, what is emphasized is not the inside weather but rather what is ‘out there’. The fact that the activity takes place in a purpose-built and protected indoor environment is in itself an indication of our desires to control it by mediating its effects on our bodies, but that mediation, in itself, is evidence that we are always operating within some form of human-weathering assemblage - direct or mediated.

It’s very much a model of weather as being outside the window, outside of us, yet despite its calendared nature, despite being inside looking out, there are all sorts of ways that the children can learn about themselves as ‘weather worlds’: how the light affects mood, how the fog or rain or snow affects transport, how over time the temporal effects of climate and human made climate change produce large effects in society.

As Gannon argues, ‘Focusing on little weather events might seem trivial, when such large events are reshaping life for us and all others on earth, and the earth itself. For example, climate change, ocean acidification, global warming, and all sorts of bizarre weather events in this era we are coming to call “the Anthropocene” all demand our attention. This is part of a post human turning to matter, and a rethinking of what matters’ (Gannon Citation2016, 87).

Despite the anthropocentric gaze of the calendar routine, the discursive force of the linguistic signifiers are still vibrant actants within the assemblage. The ‘reconciled’ and recorded weather is a determinant factor when it comes to what kind of clothes to put on, where and when to go outside and what sort of outdoor activity to think of and plan for the remaining day, which implies that the weather is an agentic and determinant factor shaping the course of the day. There was an occasion when, due to a rainy morning, a plan to go to the forest was replaced by a plan involving a playground as the forest was assumed to be a ‘bad/muddy/dirty’ place if it rains. Here, the effect of rain made the surface of the earth/the soil in the forest ‘inconvenient’ for outdoor activity. Following the change of outdoor plan, a teacher commented, ‘We will hopefully have “nice” weather tomorrow and go to the forest’. The fact that they cannot go to the forest or have to stay ‘inside’ because the weather outside is ‘bad’, means that they are having an encounter with the agency of the weather. Hence, the weather, coupled with the view of the teacher, is inhibiting/altering the group’s course of action. Thus, the weather’s agentic power is enacted in the geographies of the event as the children stay indoors and chart the weather because it powerfully affects the adults’ decisions to keep them ‘inside’ and thus warm and dry.

In cases where children wonder about the weather or the kind of clothes they need to put on, the adults direct them to look at the weather chart that is set up in the morning. At times, teachers and children also check and measure the weather condition on devices such as smartphones and iPads to see the forecast and also to compare with previous days. These measurements are performed due to the need to manage the weather by modifying our behaviour, and to possibly mitigate its agential effects by putting on extra clothes, staying inside, wearing thicker clothes or having heating/cooling, etc.

As such, the calendar routine is rather typical of what goes on in most educational setting: being inside is the default and so normalized that the weather becomes invisible. It attempts to induct children into scientific method of observation, classification and recording, and thereby ‘‘knowing about’ and ‘managing’ the weather from a distance. However, these attempts to (scientifically) manage and predict the weather are another sign of humans’ tendency to succumb to weather’s massive power. The ‘scientific’ and educational approach, e.g. the calendar routine, relies on language and linguistic modifiers (such as rainy, sunny, windy…etc.) which limits the way we relate with and understand the weather. This approach unintentionally forces us to reduce, categorize and disentangle from the beginning. Although the calendar routine appears to be highly regulated and controlled, the weather is still agentic and urges the preschool group to think and act differently, i.e. the weather is ultimately beyond human control though it can be meteorologically predicted. These sessions could be utilized as a way for children and adults to become attuned to an eco-system of which they’re a part, not apart, of a greater whole in which they are inextricably entangled.

Lively assemblage pedagogies: a possible way forward

Although early childhood curricula and educators do not regularly recognise the aforementioned child-weather events, children are always already learning within the lively weather assemblage. More formalized pedagogies tend to externalize weather, and implicitly assume that we can separate ourselves from the neglected or unnoticed assemblage by introducing the children to classifying, recording and, in a sense, controlling weather.

Likewise, the wider “climate science today may be based in seemingly detached,disembodied, neutral observations” (Verlie Citation2017, 568).This is an inherently anthropocentric, narcissistic viewpoint that positions human as stewards (Taylor Citation2017) and fixers of the problem. However, we humans are an active part of the phenomenon itself. There is no discrete boundary where weather and climate can be treated as entirely controlled phenomena. Arguably, the idea of the weather as something outside us and detached from us is part of the pathology. By excessively emitting carbons, humans are affecting climate and weather by making the former hotter and the latter more erratic and extreme in many parts of the world. Yet, we can’t ultimately control it-apart from some technological effort to seemingly protect ourselves from climate shifts and extreme weather events, which may have some beneficial effect. Nevertheless, the weather is always with us and we humans need to learn to echo and attune with the agentic power of the weather rather than attempt to control it. Therefore, apart from trying to ‘echo and attune with the agentic power of the weather’, the effects of human-induced climate change mean that there may be also other actions humans should be taking to lessen the impacts of climate change and associated erratic weather events. This further entails that fostering an ecological sensitivity and caring attitude would then become important, not only because of our vulnerability to weather, but also because of human entanglement in, and effect on, weather events.

Ingold (Citation2010) presents an alternative model of human learners, and as humans we should all be learners, to navigate the world. ‘As inhabitants of this zone we are continually subject to those fluxes of the medium we call weather. The experience of weather lies at the root of our moods and motivations; indeed it is the very temperament of our being. It is therefore critical to the relation between bodily movement and the formation of knowledge’ (Ingold Citation2010, S122).

What the children are learning in the calendar pedagogy can be seen as an extension of conventional empirical analytical climate science which conveys the message that we humans can know and even predict the weather from a distance because we are smart and in control. The types of learning in the other vignettes are more closely aligned to children learning to see the world as something in which they are already implicated and entangled. In times when extreme weather events are increasing as a result of climate change, attunement to the vitality of weather might lead to attunement to climate change. Thus, attuning to the vitality of weather and understanding the fragility, permeability and vulnerability of our bodies as affected by the force of the elements has the potential to lead to ecological sensitivity and possibly caring about climate change.

Looking at the learning spaces created in the storm, slide and sunburn vignettes, it is important to consider changing our mindset from controlling/managing weather to remaining attuned to its vibrancy and learning with the lively weather-child assemblage. A pedagogy based upon a shift towards learning with weather-child assemblages (of human and non-human bodies) might pave the way towards a wider ecological awareness of humans as one amongst other lively vitalities.

Doing this requires teachers within the Early Childhood Education for Sustainability (ECEfS) field to rethink and organize their activities as emergent and relational so that all actors (humans and non-humans bodies) are coming into play within an assemblage without being constrained by predefined subject areas and prescribed goals. Teachers need to realize that knowledge is not necessarily the exclusive domain of human subjects, and work with considerable openness to cultivate their own and the children’s ‘ability to discern nonhuman vitality’ (Bennett Citation2010, 14), as this opens up spaces for a different way of knowing and being in the world that is more relational and affective. If teachers notice, and foreground material vitality, such as the weather, they could turn the pedagogical gaze towards the ways in which the weather world that we are living in is constantly affecting and impacting our bodies and our surroundings.

For instance, returning to the hot slide vignette above, what would happen if the teacher was there, having that ‘experience’ or affect with the slide and purposely introducing a metacognitive perspective to the event? In that case, it is not only the children who get to know the sun/heat but they are reciprocally affected by its agency and this makes the learning and experience more explicit. Hence, teachers need to be attuned to the distributed agency of the vibrant weather assemblages and know how to utilize it for pedagogical purposes, and put that message out to the children not only explicitly but also in the influential hidden curriculum of their pedagogy. By modelling ‘experience’ and openness to the elements, teachers can become a powerful force for attuning to vital materialities of bodies. This suggests that ‘learning’ could be achieved when bodies are able to be affected differently by other bodies (e.g. when a hot slide generates new behaviours in vignette two), or when they come into relation with different bodies (e.g. a Mediterranean sun in vignette three).

Hence, extending (Rooney’s Citation2018a) earlier recommendation, I suggest that there is a need to challenge the pedagogy that focuses on the cognitive (weather as a concept) and broaden it to a pedagogy that embraces humans’ enmeshment and vulnerability with vital materiality. Such pedagogies are particularly important in early childhood education where socio-cultural and developmental pedagogy, which seek to promote a conscious meaning-making process, have remained dominant. Although it is not evident that it is utilized as such, the calendar time implicitly acknowledges our enmeshment by teaching cognitive skills to understand and respond (by choosing suitable clothes and activities to do) to weather. Hence, teachers can turn around dominant pedagogies, such as the calendar routine, and utilize them as a tool to recognize and attune with the agency of the weather.

Learning could still include much that would be recognizable as children interrogating phenomena and attempting to make meaning but from within an understanding of themselves as enmeshed within those phenomena. Ingold (Citation2010) discusses how the ground, a concept that at first seems simple and linear, becomes on closer examination filled, variegated, and vibrant. There is no discrete line. I’d like to argue that the vignettes indicate an approach to Early Years Education that similarly complicates, makes strange and deconstructs any simple boundary between humans and the weather, learners and the world.

ECEfS that picks up on children’s attunement to weather through lively assemblages of human and non-human vital materialities, might provide a way into a more enmeshed/embedded way of being in the world that might be critical in creating a more sustainable world. The aforementioned shift towards assemblage thinking may well be useful and illuminating in future ECEfS pedagogies and practices and perhaps beyond, as children and educators locate themselves as enmeshed in a wider vibrant world. As Rooney (Citation2018a) writes, ‘To weather’ then is to be both resilient and ethically accountable. It is also to acknowledge the interconnectedness of our actions as well as our more-than-human mutual fragility and vulnerability’ (187). More work of this kind is needed to understand the implications of such child-weather assemblage pedagogy for teaching and learning and finding of such spaces that invite such attunement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Arlemalm-Hagser, E., and J. Davis. 2014. “Examining the Rhetoric: A Comparison of How Sustainability and Young Children’s Participation and Agency Are Framed in Australian and Swedish Early Childhood Education Curricula.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 15 (3): 231–244.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Caiman, C., and I. Lundegård. 2014. “Pre-School Children’s Agency in Learning for Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 20 (4): 437–459.

- Carson, R. 1965. The Sense of Wonder. New York: Harper and Row.

- Davis, J., and S. Elliott. 2014. Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: International Perspectives and Provocations. London: Routledge.

- Ergler, C., R. Kearns, and K. Witten. 2013. “Seasonal and Locational Variations in Children’s Play: Implications for Wellbeing.” Social Science & Medicine 91: 178–185. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.034.

- Gannon, S. 2016. “Ordinary Atmospheres and Minor Weather Events.” Departures in Critical Qualitative Research 5 (4): 79–89. doi:10.1525/dcqr.2016.5.4.79.

- Grady, W., ed. 1999. Bright Stars, Dark Trees, Clear Water. New Hampshire: David R. Godine.

- Hatcher, B., and B. Squibb. 2011. “Going outside in Winter: A Qualitative Study of Preschool Dressing Routines.” Early Childhood Education Journal 38 (5): 339–347.

- Henriques, L. 2002. “Children’s Ideas about Weather: A Review of the Literature.” School Science and Mathematics 102 (5): 202–215.

- Howard, P. 2013. “Everywhere You Go Always Take the Weather with You: Phenomenology and Pedagogy of Climate Change Education.” Phenomenology & Practice 7 (2): 3–18.

- Inan, H. Z., K. C. Trundle, and R. Kantor. 2010. “ Understanding Natural Sciences Education in a Reggio Emilia‐Inspired Preschool.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 47 (10): 1186–1208.

- Ingold, T. 2007. “Earth, Sky, Wind, and Weather.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13 (s1): S19–S38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00401.x.

- Ingold, T. 2010. “Footprints through the Weather-World: Walking, Breathing, Knowing.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 16 (s1): S121–S139. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2010.01613.x.

- Ingold, T. 2015. The Life of Lines. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. New York: Routledge.

- Lagacé-Séguin, D., and M.-R. d’Entremont. 2005. “Weathering the Preschool Environment: Affect Moderates the Relations between Meteorology and Preschool Behaviors.” Early Child Development and Care 175: 379–394.

- Malone, K. 2018. Children in the Anthropocene: Rethinking Sustainability and Child Friendliness in Cities. London: Palgrave.

- Neimanis, A., and R. Walker. 2014. “Weathering: Climate Change and the “Thick Time” of Transcorporeality.” Hypatia 29 (3): 558–575.

- Nordstrom, S. 2015. “A Data Assemblage.” International Review of Qualitative Research 8 (2): 166–193. doi:10.1525/irqr.2015.8.2.166.

- Rooney, T. 2018a. “Weather Worlding: Learning with the Elements in Early Childhood.” Environmental Education Research 24 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1217398.

- Rooney, T. 2018b. “Weathering Time: Walking with young children in a changing climate.” Children’s Geography. 17:2. 177-189 doi:10.1080/14733285.2018.1474172.

- Rousseau, J. J. 1979. Emile, or On Education (1762). Translated by Allan Bloom. New York: Basic Books.

- St. Pierre, Elizabeth A. 2018. “Post Qualitative Inquiry in an Ontology of Immanence.” Qualitative Inquiry 25 (1): 3–16.

- Strengers, Y., and C. Maller. 2017. “Adapting to ‘Extreme’ Weather: Mobile Practice Memories of Keeping Warm and Cool as a Climate Change Adaptation Strategy.” Environment and Planning A 49 (6): 1432–1450.

- Taylor, A. 2017. “Beyond Stewardship: Common World Pedagogies for the Anthropocene.” Environmental Education Research 23 (10): 1448–1461.

- Tilbury, D. 1994. “The Critical Learning Years for Environmental Education.” In Environmental Education at the Early Childhood Level, edited by R. Wilson, 11–13. Washington DC: North American Association for Environmental Education.

- Tilbury, D., V. Coleman, and D. Garlick. 2005. A National Review of Environmental Education and Its Contribution to Sustainability in Australia: school Education. Canberra, ACT: Department of the Environment and Heritage.

- Vannini, P., D. Waskul, S. Gottschalk, and T. Ellis-Newstead. 2012. “Making Sense of the Weather: Dwelling and Weathering on Canada’s Rain Coast.” Space and Culture 15 (4): 361–380.

- Verlie, B. 2017. “Rethinking Climate Education: Climate Entanglement.” Educational Studies 53 (6): 560–572.

- Wilson, R. A. 1992. “The Importance of Environmental Education at the Early Childhood Level.” International Journal of Environmental Education and Information 12 (1): 15–24.