Abstract

Environmental learning is a lifelong, lifewide, and life-deep endeavor, much of which occurs in the spaces in between those that are studied, remarked upon, and documented. Within this everyday-life context, we examine the concept of learningscapes—intersecting sociocultural, intellectual landscapes where people learn about and undertake practices related to the environment understood as a holistic concept. Considering the affordances and constraints of the environment situated within this everyday-life context, we examine theoretical underpinnings and implications of making daily-life learning visible, while avoiding a doom-and-gloom approach to environmental practices. We end by highlighting research and practice opportunities within environmental learning, overall.

Introduction

Our lives are filled with a rich array of opportunities for learning about the environment: from decisions about what to eat and wear, to considering how we transport ourselves to and from work, to purchasing items to fill our homes, and choosing how, where, and with whom to spend time outside of professional or academic obligations. If we pay attention to feedback loops, recognizing how each action has ripples and consequences, such situations and choices remind us of the way that the world in its totality—from basic social, ecological, and economic interactions to more complex environmental issues, concerns, and policies—is comprised of numerous intersecting systems. Within the course of our everyday lives, our actions impact the world around us in small and large ways, as individuals situated within larger systems (Macnaghten Citation2003; Matson, Clark, and Andersson Citation2016).

Immersed in possibilities to ‘develop relationships with other living beings and the biophysical elements and phenomena of ecosystems’ (Sauvé Citation1999, 16), we primarily learn about environmental systems, and our roles within them, through daily-life activities that include but are not limited to direct observations, discussions, and decisions that occur in relationship with others (Gould et al. Citation2019; Rogoff Citation2003). Moving in, out, and through those activities allows for environmental learning in countless ways: through family life, media portrayals (e.g. watching television, surfing the Internet, reading newspapers and books, and discussing those with family, friends, and colleagues), direct experiences with the natural world, and/or settings and resources including, but not limited to libraries, recreational centers, museums, and parks (Barron Citation2006; Blewitt Citation2006; Heimlich and Falk Citation2009; Marsick and Watkins Citation1990, Citation2001; NRC Citation2009; Reid and Liu 2018; Spear and Mocker Citation1984; Tal and Dierking Citation2014).

At its most basic, ‘learning’ refers to the process of taking in data through our senses, processing those data, and using or applying the data in a variety of settings and milieus (Bloom Citation1976). Tal and Dierking (Citation2014) describe it as ‘cumulative, emerging over time through myriad human experiences’ and emphasize its lifelong nature, noting that, ‘experiences children and adults have in these various moments dynamically interact, influencing the ways individuals construct scientific understanding, attitudes, and behaviors’ (252). Heimlich and Reid (Citation2016) note that humans are constantly absorbing and processing information about our surroundings, including what we sense and how an environment makes us feel even if we are ‘not always cognizant of the world around [us] at any given point in time’ (749). Yet no single action or activity can be separated from another when imagining what counts as a ‘learning experience’ as we are constantly becoming and doing (Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Rogoff Citation1994; Tal and Dierking Citation2014).

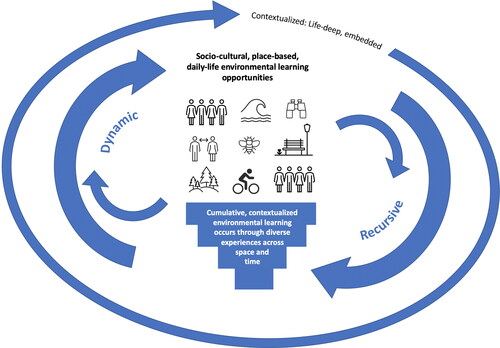

Learning, and environmental learning in particular, happens across a variety of biophysical and sociocultural settings, experiences, and contexts and is thus recognized as being lifewide; lifelong or occurring throughout the lifecourse; and life-deep, or influenced by one’s culture, values, beliefs, and ideologies (Gould et al. Citation2019; NRC Citation2009). Because of these ongoing, mediated aspects, learning processes and outcomes are subsequently and unavoidably influenced by, and in turn influence, values, beliefs, and ideologies (Gould et al. Citation2019; NRC 2009, 28; Rickinson Citation2006). Pollard (Citation2003) emphasizes that learning occurs in ‘layers of contextual influence’ stretching ‘from infancy to childhood, adolescence, youth adulthood, middle age, retirement, and old age’ (174). Lewin (Citation1935, Citation1936) uses the term ‘lifespace’ to describe the lifewide and life-deep totality of inner and outer forces that have brought a person to the current moment in life and create a canvas for related behaviors and decisions; similarly, Watson and Tharp (Citation1972) refer to learning as ‘any changes in acts or capacities that develop as a result of interaction with the environment’ (28). This ongoing, recursive interaction and processing in conscious and deliberate ways—as well as unconsciously and/or subconsciously—suggests endless possibilities for infusing, or perhaps more specifically recognizing and marking, environmental learning in everyday life ().

Figure 1. What are key aspects in our definition of learning? Learning as social, relational, dynamic, and recursive, occurring embedded within a sociocultural context.

Yet informal, non-formal, and incidental learning opportunities in everyday life remain underexamined and undertheorized in the environmental literature (Marsick and Watkins Citation1990, Citation2001, Citation2018; Spear and Mocker Citation1984; NRC Citation2009; Watkins et al. Citation2018). Such a framing amplifies learning moments by opening lines to conscious connections across experiences, issues, time, and space. By examining and attending to how, when, where, and why people learn about the environment—and what in the course of that learning motivates engagement in environmentally related everyday-life behaviors as well as longer-term practices—abundant opportunities emerge for co-creating the mutually desired environment of the future through individual and collective actions. Indeed, a person’s life is not comprised of ‘one environment,’ but rather a continuous flow of situations and settings to which an individual must adjust and that creates the context for action (Watson and Tharp Citation1972). We describe this holistic view as an individual’s learningscape (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2015; Heimlich Citation2019; Heimlich, Adams, and Stern Citation2017). In this frame, environmental learning is a dynamic, social endeavor, influenced by interactions among people as well as the broader sociocultural and biophysical contexts ( Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Marsick and Watkins Citation2018; Rogoff Citation1994; Vygotsky Citation1978).

Environmental learningscapes: lifelong, lifewide, life-deep

Holistic in nature, one’s learningscape is marked by intentional practice and reflection, creating a generative space where people can consider how they move through life and construct meaning within and among their myriad intersecting experiences. In this frame, learning—often incidental—occurs through social interactions such as those with family, friends, or even casual acquaintances, and through participating in activities in a variety of contexts, such as at work, while traveling, in the neighborhood, or inside the home (Gould et al. Citation2019; Marsick and Watkins Citation2018; NRC Citation2009). Making meaning of those experiences in context of past events and future expectations occurs through contemplation and attending to the shifts that occur within various social roles (Rogoff Citation2003).

Occasionally, people encounter particularly powerful learning experiences that stand apart from daily-life activities, marking a memory, punctuating a moment, motivating a desire for greater exploration, or prompting deeper reflection. Such moments—called variously mountaintop moments, peak experiences, or significant life experiences, among other related terms—may stand out immediately from the background of everyday life or may be marked in retrospect (Bergs et al. Citation2020; C’De Baca and Wilbourne 2004). They may emanate from the afterglow of a flow state (Csikszentmihalyi Citation1990) or unifying event (Ehlman, Ligon, and Moriello Citation2014; McCold Citation2008), or they may reflect the balance of complexity, tempo, and purpose that contribute to ‘savoring’ (Bryant and Veroff Citation2017).

Research documents that these outstanding experiences are, at times, reported to occur during physically or emotionally intensive endeavors, such as experiences that are immersive and that remove one from the physical or emotional context of day-to-day life (McDonald, Wearing, and Ponting Citation2009). They may also occur during, or result from, an intellectually stimulating and/or emotionally engrossing activity focused on a purpose larger that one’s self (Damon Citation2009; Damon, Menon, and Bronk 2003), such as an activist-related effort to preserve a local park or create greenspace. Such opportune moments might also occur during disruptions in one’s life routine, such as becoming a parent or grandparent (Bauer and Park Citation2010), or on the heels of another experience, such as moving houses, taking a new job, or retiring from fulltime work (Dai Citation2018). Those moments may capitalize on what some researchers call the ‘reset effect,’ marking a significant transition from a prior trajectory or creating an opening for a new interest to emerge (Azevedo 2011; Koo et al. Citation2020 ). Such events, and the related spikes in interest and motivation, can remove people from their everyday patterns, encourage reflection, and even catalyze change (Bauer and Park Citation2010; Baumeister 1994; Dai Citation2018; Koo et al. Citation2020). Psychological studies suggest that these moments of insight and elevation punctuate everyday life (Heath and Heath Citation2017), creating openings for learning about the environment in ways that are memorable, actionable, and—with appropriate support—sustainable.

Reexamining the fluid environmental learningscape frame attending to these punctuated experiences facilitates meaning-making in the interstitial spaces of everyday life (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2015; Lefebvre [1947] 1991). The notion of learningscapes embraces the range of places, settings, and social roles in which people learn about the environment. Such a perspective provides context through which people may become motivated to undertake environmentally related social practices, as well.

Although traditional perspectives on environmental learning often focus on formal contexts, this emphasis risks overlooking the expanse of other settings where environmental learning occurs daily. A broad approach does not preclude, but rather draws together, learning that may occur in a range of contexts, as those places represent the constellation of meaningful learning experiences that people encounter, deliberately or incidentally, in the course of daily living. Falk and Dierking (Citation2012, 1074) describe the science learning landscape as occurring, ‘beyond formal and informal educational institutions, [including in] the various media, libraries and other community-based resources and people’s hobby groups and workplaces.’ To this science learning landscape, we add the landscapes of opportunities for the arts, sports, dining, entertainment, history, and nature. Reid and Liu (2018) note the focal role the term ‘scape’ has when placed toward a particular element such as land/sound/smell/city/techno/and ethnoscape.Footnote1 Bringing these different perspectives together in a learningscape capitalizes on the breadth, depth, and constancy of learning, embracing the range of places, settings, and social contexts in which people learn about the environment and may be motivated to become involved in environmentally beneficial practices. To understand learning in this lifelong, lifewide, and life-deep conceptualization, it is important to contextualize within a person’s life and complex being (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2015; Lave and Wenger Citation1991).

Social roles: the individual in context

Social role theory (Biddle Citation1979, Citation1986), along with life-course theory (Elder Citation1998; Moen Citation1996), emphasizes that humans of all ages are complex socially oriented animals who operate within a ‘social environment’ and create ‘socially shared patterns of expectations for behavior’ (Newman and Newman 2017, 419; Pollard Citation2003). Entwined with cultural identities, such as ethnicity and heritage, and with a myriad of other individual attributes, such as gender and age, different roles—parent, child, teacher, student—facilitate the enacting of various aspects of oneself. Those delineated roles allow for various aspects of one’s life to be dominant at different times and interact (Biddle Citation1986; Heimlich, Adams, and Stern Citation2017; Newman and Newman 2017). A single individual can, for example, enact concurrent roles as a parent, member of particular cultural group, and community activist, when those roles intersect and interact as they play out within context, especially in complementary ways (Reid and Hardy Citation1999; Tiedje et al. Citation1990).Footnote2

People play many roles throughout their lives, and social role theory suggests that the individual in context influences the behaviors that one performs at any particular time (Biddle 1979, Citation1986). That context impacts where one directs attention and, relatedly, how one interprets an experience (Feather Citation1982). The effect role on one’s lens and interpretation of the experience then influences what is most likely to be learned (Heimlich, Adams, and Stern Citation2017, 118). People enact different aspects of themselves in different contexts (Biddle Citation1986) and, from a symbolic interactionist perspective, those social roles are perceived to be cultural objects, ‘recognized, accepted, and used to accomplish pragmatic interaction goals in a community’ (Callero Citation1994, 232). Wide-ranging and overlapping roles strongly influence how individuals move through their lifecourse, how they see themselves at any given time, and whether they have the self (Bandura Citation1986) or response efficacy necessary to engage in impactful environmentally beneficial practices (Maiman and Becker Citation1974; Milne, Sheeran, and Orbell Citation2000; Stanley and Maddux Citation1986).

Another theoretical area with implications for learning and action draws on theories of attention perception and cognitive schema. Studies in this realm provide evidence that learners enter the learning context holding a set of beliefs, values, and ideas based on prior experiences. Those prior affective underpinnings subsequently shape their expectations and impact the focus of their attention (Berlyne Citation1951, Citation1954; Feather Citation1982; Read, Vanman, and Miller Citation1997). In turn, this focusing affects the interpretation and filtering of educational experiences, messages, and resulting outcomes (Stylinski et al. Citation2017). Relatedly, research also documents that people attend to information sources with which they believe they share common perspectives. Consequently, they often fail to notice experiences and information that are misaligned with and/or contradict their held beliefs, values, attitudes, and knowledge (Doering and Pekarik Citation1996; Heimlich and Reid Citation2016).Footnote3

People seamlessly shift between social roles. Consider a parent with friends who are also parents. The adults can engage in a meaningful conversation, yet instantly shift attention to their children, then re-enter the adult conversation with a brief apology to reorient. Or consider the ways in which people rapidly shift from professional to peer to familial relations: As an individual moves from one social role to another, attention changes, and the data noticed are interpreted through a different set of lenses. Individuals in the same location, at the same time, can hold radically different perceptions of that moment and place, based on their differing roles at a given time. Social roles help people make sense of what they need or want to attend to in the moment.

Yet social roles can also constrain perceived learning as people consciously consider themselves to be ‘learners’ in relatively few settings. Thus, effectively enacting the role and identity of a learner may require more of an explicit marking of experience while moving through life, noting the many settings, interactions, resources, and opportunities of environmental learning. In turn, learningscapes—or the robust and holistic context in which those learning experiences occur—also influence the identity of the learner (Heimlich, Adams, and Stern Citation2017). Imagine, for example, that a parent and child walk to the local beach to play in the sand and admire the view as part of their weekend ritual. For the past few weeks, they have noticed an increasingly pungent scent emanating from the water, and this weekend they see an orange-tinged bubbly line on the shore. The child is mesmerized by the colored sand and curious about the cause, while the parent wonders whether these shifts signal a safety-related concern. They return home and seek information about the source and implication of these changes online. A brief internet search for the name of their beach plus ‘water quality’ returns several hits related to recently discovered sewage overflows and redirections in storm drains, raising contamination concerns among scientists and community activists. A local group called ‘Save Our Coast’ is leading the related studies and their findings contributed to the science reporter’s exposé, which ends with a call for greater accountability on the part of several adjacent businesses. Reading up on the nonprofit organization, the child and parent sign up for a beach cleanup that Save Our Coast is sponsoring, invite their neighbors to join them at the forthcoming event, and make a small donation to support the group’s efforts. In this example, the adult enacts social roles of parent, facilitator, learning partner, community advocate, connector, and environmental supporter, and the youth enacts roles of child, place-based learner, questioner, cleanup participant, and neighbor, among others.

As demonstrated here, and visible in similar situations, the social roles individuals enact contribute to the interpretation of an event, exchange, or experience in the learningscape. Specifically, shifting roles and lenses has implications for learning in the everyday world, particularly impacting how people make sense of complex, environmental issues, messages, and opportunities in the midst of the constant barrage of daily-life information.

Learning and everyday life

Various disciplines—including but not limited to psychology, philosophy, political science, anthropology, sociology, history, art, and the learning sciences— include streams of research dedicated to examining aspects of everyday life (Highmore Citation2002), with such studies exploring how individuals create structure and meaning in their lives (Adler, Adler, and Fontana Citation1987). Combining micro and macro perspectives facilitates understanding how larger-scale influences, such as politics, technology, and popular culture, might affect and interact with smaller-scale processes of daily life. This interplay is particularly relevant in relation to the environment where situations, trends, and challenges occur within a system, with every process and interaction connected. Therefore, actions taken at the macro-scale interact with micro-routines and habits; by extension, issues arising from those micro-scale actions impact the macro-scale, and vice versa (Neal and Murji Citation2015). Gibson et al. (Citation2014) discuss the embeddedness of sustainability in everyday life, using household activities as an example of the ways in which micro-decisions can have macro-scale effects. Illustrating how everyday decisions can align or break with larger environmental issues, environmental writer Thomashow (Citation1995) says, ‘Whether I choose to toast a bagel, or eat out at McDonald’s, or collect wild berries in the forest, my actions are much more complex than they initially appear. … Through the cumulative observation of dozens of such ordinary life activities, the patterns of ecological and political interconnection begin to emerge’ (136).

Philosopher and sociologist Lefebvre, in his three-volume series titled The Critique of Everyday Life (1991, 2002, 2005), describes ‘the residual,’ or ‘what is left over,’ when speaking of everyday life. He refers to the quotidian as a space that is easily overlooked, noting that such residuals occur beyond, above, within, and among other aspects of life that are highly structured, analyzed, and scheduled. For this reason, Lefebvre (1991) refers to everyday life as the locale where all life occurs, using this critique as a platform from which to study the social production of space, a subsequently productive line of work for space-and-place sociologists (e.g. Hayden 1997; Soja 1989).

Building on that early interest, a substantial portion of everyday-life scholarship has continued to occur within sociology, which includes a sub-specialty area of ‘everyday life studies’ (e.g. Adler, Adler, and Fontana Citation1987; Kalekin-Fishman Citation2013; Maffesoli Citation1989; Neal and Murji Citation2015; Sztompka Citation2008). This focus encompasses an interest in content as well as methods appropriate to studying everyday-life practices. (See, for example, Neal and Murji Citation2015.) Two review papers (Adler, Adler, and Fontana Citation1987; Kalekin-Fishman Citation2013) describe the overall arc of everyday-life studies research in sociology, noting that it does not derive from a single empirical perspective but, rather, provides a micro-orientation to the details of people’s lives, in contrast to the more-common macro-scale lens applied in classical sociological research and theory. Neal and Murji (Citation2015), in the Sociology special issue titled, ‘Sociologies of Everyday Life,’ note that, ‘it is apparent in micro social life [that] the banal and the familiar are co-constitutive of the wider complexities, structures, and processes of historical and contemporary social worlds’ (812).

Sociologists focusing on everyday-life studies (e.g. Adler, Adler, and Fontana Citation1987; Neal and Murji Citation2015) argue that the importance of this area of research lies in studying small-scale processes with a goal of generating more widely applicable insights and theory from those seemingly trivial happenings and patterns. Through this lens, the small, almost-indescribable, often-undetected moments constitute abundant opportunities for interacting with, learning about, and sparking interest in the environment, creating space for expansive, generative environmental learning opportunities. Incorporating the study of the everyday, and a better understanding of the processes of everyday life, offers a window into the scores of incidental experiences from which a person constructs meaning with the potential for growing environmental knowledge, attitudes, skills, and practices over the short, medium, and longer term (Heimlich and Reid Citation2016).

Another relevant area of the everyday-life literature derives from educational research that emphasizes the learning aspects, including how, when, where, why, and with whom people learn in the course of daily-life activities; how to enhance curricular relevance to learners’ out-of-school lives; and how to bring everyday-life experiences and concerns into both formal and informal settings (Blewitt Citation2006). In such instances, the important emphasis is not on what is learned, but rather on the individual’s need in that moment (Falk and Dierking Citation2010; Heimlich and Reid Citation2016).

This focus on and interest in connecting everyday learning with ongoing practices occurs in a number of subfields, including formal science education (e.g. Birmingham and Calabrese Barton 2014), adult education (e.g. Hamilton Citation2006), workplace education (e.g. Taylor, Evans, and Mohammed 2008), curriculum and instruction (e.g. Heath and McLaughlin Citation1994), early childhood education (e.g. Fleer and Hedegaard Citation2010; Hedgaard and Fleer 2019), music education (e.g. Batt-Rawden and DeNora Citation2005; Clark, Dibben, and Pitts 2009) and informal science learning (NRC Citation2009; Reid and Liu 2018), among others. The Journal of Research in Science Teaching, for example, published an issue on learning science in everyday life contexts (Tal and Dierking Citation2014), which included studies addressing cultural learning pathways (Bricker and Bell Citation2014), school–museum interactions (Kisiel Citation2014), science stories in the news (Polman and Hope Citation2014), and green festivals/carnivals (Birmingham and Calabrese Barton 2014).

Specifically focusing on environment-and-sustainability research, the everyday-life literature is slimmer. In their systematic reviews, sociologists Blake (Citation1999) and Myers and Macnaghten (Citation1998) lament the paucity of research in this vein. They highlight how little scholarship exists on how environment-and-sustainability-focused government programs and policies intersect with daily life. Blake, writing in 1999, described a ‘recent’ explosion of interest in exploring everyday environmental values of different members of society, as ‘both researchers and policymakers have increasingly acknowledged the key role that individual people play in the quest for sustainability’ (262). Although an increase in related literature followed that call for a short period, (e.g. Blewitt Citation2006; Gibson et al. Citation2014; Macnaghten Citation2003; Neal and Murji Citation2015), no sustained emphasis or unified program of research has emerged at the sociology/sustainability intersection.

Those who have highlighted everyday life within the environmental learning literature include Sauvé, who argues for considering environmental education beyond the definition of ‘education in, about, and for the environment’ (Lucas Citation1972/1991). Sauvé (Citation2002) notes, instead, that environmental education is about the human relationship to the environment, broadly defined. She describes reimagining human-environment relationships with one avenue being to reframe the environment as ‘a place to live,’ which focuses on ‘everyday life—at school, at home, at work, etc.’ (2). Sauvé (Citation2002) suggests that these connections are foundational to environmental education as they encourage people to ‘explore and rediscover one’s own surroundings, that is, the “here and now” of everyday realities, with a fresh look that is both appreciative and critical’ (2). She argues that work in this vein could aim to ‘develop a sense of belonging and encourage dwelling’ as ‘the local context is the first crucible for the development of environmental responsibility, in which we learn to become guardians, responsible users and builders of Oikos, our common “home of life”’ (2002, 2).

The interdisciplinary body of research focusing on significant life experiences (cf, Chawla Citation1999; Howell and Allen Citation2019; Tanner Citation1980; Wells and Lekies Citation2006) draws on developmental psychology, cultural anthropology, and the learning sciences to encourage reflection on meaningful aspects of one’s lifecourse. Scholarship in this vein explores areas such as what may have sparked an initial interest in environment, stewardship, and conservation and what processes, factors, and socio-environmental structures and contexts may have supported those initial interests as they emerged into more mature, fully formed interests and areas of deep dedication as adults. Chawla and Cushing’s (Citation2007) ‘Education for Strategic Environmental Behavior’ applies these principles of engagement to young people, drawing on Dewey (Citation1916, Citation1938), who emphasized the importance of incorporating everyday-life concepts into educational experiences such that those experiences become relatable, infused with meaning and purpose. Chawla and Cushing (Citation2007) consider those principles with regard to questions of democracy and participation for children, stating that, ‘children also need opportunities for collaborative decision-making in everyday life’ because those decision-making activities ‘enable young people to exercise control over their environment and other elements of their lives’ (442). Finally, Chawla and Cushing (Citation2007) detail everyday-life experiences that relate to responsible environmental behavior, such as positive experiences of nature, observing destruction of valued places, and reading books on nature and the environment, emphasizing that pathways to environmentally related civic engagement include ‘confrontations with social inequities and environmental problems, opportunities for collaborative decision-making from early childhood, and having one’s voice valued’ (443). This line of research, as exemplified in Chawla and Cushing (Citation2007), among others, emphasizes that environmental learning happens every day in a variety of contexts, yet is not necessarily part of everyone’s daily awareness.

Scholars from these fields and others—such as urban planning (e.g. Greed Citation2011), sustainable development (e.g. Vallance, Perkins, and Dixon Citation2011), and technology (Vannini Citation2009) to name a few—apply everyday-life lenses to studying place connections, motivation for place-protective behavior, support for participation, and related topics. These wide-ranging interests among researchers are motivated by the recognition that such a daily-life focus—or the in-between space, as Lefebvre calls it—reflects embodied experiences (Sauvé Citation2002; Payne Citation2006).

Learningscapes

The learningscapes framework offers one particularly powerful way to align perspectives of environmental learning with everyday life contexts. Learningscapes focus attention on how a person moves through life, with the potential for making meaning from, and learning across, among, and between myriad life experiences and social roles (Heimlich, Adams, and Stern Citation2017). The individual journey includes moving through the environmental learning ecosystem (Uden, Wangsa, and Damiani Citation2007) of formal, nonformal, and informal settings, such as parks, nature centers, zoos, gardens, arboreta, aquariums, agency and NGO programs, media encounters, and neighborly discussions, among others. Here, the term ‘ecosystem’ invokes imagery analogous to its ecological sense, but does not refer to a biological ecosystem; instead, the learning ecosystem incorporates the rich, connected enterprises of organizations, institutions, and relationships that provide the supporting structures for learning to occur (Wojcik, Ardoin, and Gould Citation2021). In contrast to the learning ecosystem, the learningscape is not limited to the ecosystem structure, but rather also includes personal, social, and physical interactions; it incorporates individual passions, needs, and opportunities. In this way, the learningscape is practically derived and relates to an individual’s life.

As life proceeds in a continuous manner, rather than in segments, learningscape framing recognizes that learning rarely happens as a result of a single experience; rather, it is cumulative and emerges over time through layered experiences (Tal and Dierking Citation2014). In retrospect, when recalling what was meaningful or shifted one’s trajectory, people often view or perceive incidents as a series of independent events. At other times, their memories compress time and activities, blending multiple experiences into one event (Flaherty Citation2000). This horizontal, lifewide learning and the subsequent compressing of time and experience occurs not only across experiences, but also within a visit or program such that the source of an understanding or discrete piece of information becomes obscured over time, blended into the larger whole (Mony and Heimlich Citation2008).

Although learning in its most holistic sense is continual, learning about any single thing is often sporadic and interrupted. People make meaning across and between life experiences and may not, without particular effort, consciously connect specific events. Each individual’s learningscape encompasses a mosaic of social roles, as well as the ways in which that person chooses to engage in society, structures, and institutions. Learningscape framing incorporates what individuals retain cognitively, affectively, and skill-wise from across those many experiences, then considers how they construct meaning, especially around understandings of and action on environmental issues (Heimlich and Reid Citation2016).

As Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) emphasize, ‘learning is not merely situated in practice—as if it were some independently reifiable process that just happened to be located somewhere. Learning is an integral part of generative social practice in the lived-in world’ (35). Ultimately, the learningscape complements learning across the lifecourse, suggesting that it is not curricular or sequential but, rather, sporadic and incidental. Environmental learning is not simply an awareness of learning about the environment (e.g. Marsick and Watkins Citation2001). Rather, people often believe, feel, know, and act without awareness, thus losing the opportunity for consciously connecting across time, space, experiences, and issues (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2015). In this context, the importance of environmental learning relates to helping people make meaning across and between life experiences as well as consciously connect specific events; or helping people become aware that, in everyday life, daily interactions and engagement with the natural and built environments the potential for learning exists. Therefore, environmental learning occurs most effectively when people become aware that ‘in every exchange, there is potential for new data, insights, or connections’ (Heimlich and Reid Citation2016, 752) to be made.

Why does this matter?

Considering learning and the lifecourse in this context challenges conventional assumptions about how we learn about the environment and the world around us. This conscious construction creates a way of organizing one’s experiences so that, as one moves through life, all experiences begin to either fit into one’s learningscape or dissettle the journey. This process focuses attention on organizing, providing a framework, and allowing for meaning-making rather than assuming a didactic knowledge transfer. Indeed, we refer to curation for authentic integration of learning theories into informal and incidental contexts and to aid in the seamless transition of formal environmental learning into everyday life. Gould et al. (Citation2019), for example, discover that, in settings such as farmers markets, people learn about the regional food system, community dynamics, the effects of weather patterns on local produce, and community-scale politics, among other personally relevant issues, topics, and opportunities. Research participants’ uptake and processing of this information occurs in a socially and culturally relevant setting by attending to and participating in activities authentic to their daily lives and roles as parents, neighbors, consumers, and voters. They then have immediate opportunities to take meaningful, impactful action, such as making an environmentally friendly purchase, discussing a topic of community importance with a friend or neighbor, or learning from a farmer about which local vegetables are or are not in season due to current patterns impacted by broader-scale environmental conditions.

Yet few people, if any, are cognizant of how the immediate moment builds on thousands of prior experiences interpreted through their many social roles leading to that learning. As Jarvis (Citation2009) notes, ‘a great deal of our everyday learning is incidental, preconscious, and unplanned’ (19). Similarly, Heimlich and Reid (Citation2016) point out that ‘one never knows when an idea or experience with the environment will add to understanding an issue, challenge something considered known, or delight, surprise, or affect one deeply’ (752). For decades, studies have documented that people ascribe the stimulus to the moment when they learned something and made a decision to act, falsely suggesting that the decision to change is sparked by a single event or piece of data, rather than recognizing the lengthy process leading to actual change or action (Prochaska and DiClemente Citation1982).

Considering learning in the more-continuous way also facilitates authentic integration of the learner-in-place (Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Rogoff Citation1994; Rogoff, Matusov, and White Citation1996), raises awareness of learning opportunities in everyday life (Macnaghten Citation2003), and situates the individual in everyday-life learning contexts (Falk and Dierking Citation2010). Supporting prior studies, our work with the Environmental Learning in the Bay Area project (Gould et al. Citation2016) reveals that the most commonly identified venues for learning about the environment, by people from all walks of life, are those involving family and friends. Research participants also secondarily identify media (including the Internet). These sources—family, friends, and media—are key and ubiquitous elements of everyday life. In Barron’s (Citation2006) paper on learning ecologies, she finds that people draw from a rich array of contexts, ‘each context being comprised of a unique configuration of activities, material resources, relationships, and the interactions that emerge from them’ (195), in supporting and pursing interests, or self-directed learning.

Using this learningscape frame, and recognizing that learning occurs in many settings, is intentional and unintentional, lifelong, lifewide, and life-deep across the lifecourse, provides environmental learning organizations such as science centers, natural history museums, zoos, and aquariums with an opportunity to be explicit about their language, conceptual frame, and the approach that they are using (Marsick and Watkins Citation1990; Wojcik, Ardoin, and Gould Citation2021). Many organizations are already beginning to integrate learningscape-type thinking into their teaching and learning (NRC Citation2009). Consider the botanical garden that organizes hundreds of community gardens and uses them to teach both nutrition and plant-science through experience and dialogue; or the many zoos that are increasing their focus on local species needing protection from mussels to bees with the intention of both helping protect the species while also bringing zoos’ field-based conservation work closer to home; or the nature center in an Important Birding Area that becomes an ongoing meeting place for local birding societies. Even so, the question remaining is how these organizations can better design experiences that foster learners’ authentic connection with environmental issues.

Taking the learningscape perspective and having organizations and institutions view learning in this way, foregrounds the fluidity of social roles as well as the multiplicity of individual roles. It also suggests the importance of designing for the intersection of peoples’ values, norms, roles, identities, and interests in nonformal and informal settings, and to consider how all these places, even with our best intentions, are actually, for many, incidental learning settings (Bricker and Bell Citation2014; NRC Citation2009).

Opportunities: implications for research, practice, and ourselves (as learners)

The everyday-life and learningscape framing opens possibilities for connecting the environment to people’s daily experiences in ways that are meaningful and relevant. In forced-choice studies and experiments, a continuum appears to exist with regard to how much people purport to care about the environment particularly when placed in comparison with numerous other pressing concerns (Gould et al. Citation2019). Yet if and when the environment is integrated into a person’s worldview, framed and emphasized as essential, forming the basis for all life on earth and the core from which all possibilities and bounties emanate, they then learn and recognize how crucial a healthy, functioning environment is to even the most basic levels of health and wellbeing. Such a reframe can be transformational and, in this new worldview, environmental education moves from a ‘nice to have’ to a ‘need to have’ (Morris Citation2019; Ardoin and Bowers 2021). It is seen as connecting lived, authentic experiences to critical messages and issues through empowerment and engagement.

Consider, for example, the farmers market or local grocery store. Each of those environments might be designed in a way that intentionally or unintentionally supports learning about the local food system, human community, and broader world through bridging immediate experiences with other daily-life experiences and roles with shared cognitive, affective, and behavioral opportunities. In this context, the social elements of learning are also essential: imagine if each of many diverse sites of interaction are designed to facilitate and encourage connected meaning-making and learning about the environment (NRC Citation2009; Oldenburg Citation1999, Citation2013). Those sites may include, but are not limited to, what Oldenburg (Citation1999) calls ‘third spaces,’ or those locales between home and work that address and help give ‘balance to the increased privatization of public life.’ These ‘Great Good Places,’ such as community centers, libraries, and coffee shops, provide space for fostering connection and supporting casual, informal gatherings.

For research

Everyday life learning in third spaces and elsewhere can motivate researchers and community members alike to think differently about what ‘learning’ looks like, how one might experience it on a daily basis, the role learning plays over the course of one’s lifetime, and—for researchers particularly—how one might effectively measure it. The learningscape frame requires that learning is conceptualized as a process and product of living. Everyday-life researchers, thus, focus on observation, discussion, and embedded assessment approaches because, similar to learning itself, it becomes challenging to separate the research from the practice of learning. Developing clear definitions of the input, process, and outcome variables is imperative, however, and, from those clear understandings of how one might operationalize the variables—such as what learning is and looks like—it becomes concurrently clearer, yet also at times more challenging, to ‘test’ the efficacy of interventions as everyday-life learning is relational, situated, individual, cumulative, and occurs over a lifetime. Because of its ever-changing nature, short-term measures, as currently designed and imagined, may not be appropriate (Brinkmann Citation2012); measures of longer-term outcomes and impacts are also needed to complement those that are more immediate.

Considering some alternative methods and ways of documenting learning in everyday life, we turn again to the sociological literature. Myers and Macnaghten (Citation1998) focus on people’s ‘daily talk’ about the environment, for example, attends to language in common settings such as pubs, markets, and buses. Moreover, they examine material culture in terms of government and NGO pamphlets and leaflets, inviting members of the public to react to these in focus groups, recording their subsequent reactions and discussions. Others use methods such as experience sampling (Hektner, Schmidt, and Csikszentmihzlyi 2007); in-home ethnography (e.g. Bean Citation2008; Heffner, Kurani, and Turrentine Citation2007); journaling (e.g. Picca, Starks, and Gunderson 2013); and photography (e.g. Bean Citation2008; Biggar and Ardoin Citation2017), in an attempt to offer authentic characterizations of, and reflections on, everyday life.

Challenges exist with these alternative approaches. People continuously and unconsciously play out social roles, either denying that they are enacting a particular role or later, upon reflection, suggesting that a particular role or action was out of their character (‘I can’t believe I did that,’ or ‘That really wasn’t like me’). In many settings, people may not realize that they are learning as, in their minds, learning is not a human activity, but rather the product of schooling (Rickinson Citation2006). The sporadic, fluid nature of learning creates a challenge in reflecting on experiences and pinpointing when and where one learned something. This leads to people wanting to find the ‘right’ or acceptable answer when describing a learning process (Mony Citation2007). Yet despite (or perhaps because of) these challenges, opportunities abound for researchers to be bold and creative, seeking to reimagine research questions that push against notions of ‘right answer’ thinking, and developing creative tools that facilitate exploration of this promising landscape.

For practice

When we consider what it means to learn in everyday life and across the lifecourse, we acknowledge that the potential for learning exists in every moment. Many consider learning to be a function of institutional practice—that is, as an individual interacts with an institution such as a nature center, botanical garden, or aquarium, learning occurs. Indeed, many societal institutions—such as schools and museums—are built around this frame. With our suggested reframe, we are not suggesting that these institutions lack importance; rather, we suggest that they serve a foundational role in the everyday-life learning system. They are trusted institutions, sought out as information sources and providers of essential third space. They are boundary organizations, functioning at the nexus of ‘science’ and the public dialogue, where the two collide to co-create the meaning of ‘environment’ and ‘science’ (Guston Citation2001; NRC Citation2009). Learningscapes lay bare the practical, necessary role for boundary organizations, such as museums, technology centers, and even backbone groups, which bring together people and organizations in a neutral, generative place where they can help guide the conversation in productive, meaning-making ways.

For those institutions, this framing may require a different self-conceptualization: not as the site for one-off visits or for weekend jaunts only, but rather as a continuous, critical part of the learning ecosystem. In developing on- and- offsite programming, the institutions can ask: What role does our institution play in the lifecourse across a variety of social roles? How might we function as a continual touchpoint throughout people’s lives?

While for some the same institution may represent a ‘home’ zoo, aquarium, community science center, or museum, for others it may be a place they visit only once, yet that memory becomes so powerful that it remains forever etched in their memory and connects with future learning and behavioral outcomes. If institutions conceptualize environmental learning from an ecological perspective, they might ask: Recognizing that we cannot—nor should we try to—be all things to all people, what niche do we hope to fill in visitors’ lives? How might we collaborate with other community providers, leveraging resources to create complementary, holistic environmental learning opportunities across the lifecourse? How might we contribute to the development of additive, meaningful pathways that are lifelong, lifewide, and life-deep?

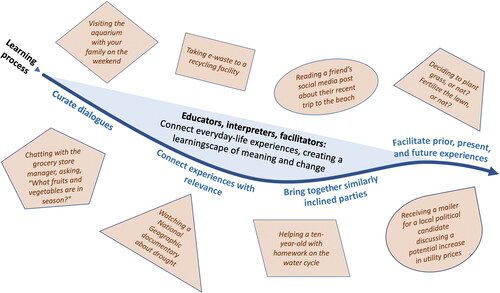

In these ways and others, learningscapes offer a special role for educators, interpreters, and facilitators to help make sense of the constant barrage of information streaming through people’s everyday lives. Educators in these settings can assist in curating dialogues, bringing together interested and similarly inclined parties, and facilitating prior, present, and future experiences and learnings. As an outcome, educators in incidental learning structures and experiences (and additionally—in an ideal world—in formal settings) help others critically consider the social role lens through which they interpret experience, and connect that experience with others that may have relevance ().

Figure 2. Everyday-life environmental learningscape: Educators and interpreters play influential roles in learningscapes, connecting everyday-life experiences through, for example, curating dialogues, facilitating experiences, and bringing together groups in ways that help make meaning and illuminate avenues to change.

Another way to consider application is in helping individuals connect the many experiences in their lives and facilitate meaning across experiences or helping individuals connect experiences and make meaning and learn cumulatively across and among all experiences (Heimlich, Adams, and Stern Citation2017). What we propose is not bound by the concept of ‘learning’ as contained in ‘schooling.’ In that construction, it becomes all-too easy to dismiss everyday-life contexts in favor of structured, formal learning. Yet daily-life experiences—where we learn to think, feel, process, develop skills around, and enact change in relation to environmental issues, often alongside our friends, family, and colleagues—occur in informal and real-world settings, throughout lifelong, lifewide, and life-deep contexts.

For learners

What does this everyday life emphasis within a learningscape context mean for learners? Rogoff (Citation1994) describes an authentic learning community in which learners and educators co-create the learning space. In this dialogical perspective (Rogoff Citation1994), everyday life is as much a part of the learning landscape as any formal or informal learning space, with the lines between contexts being as fluid as those between ‘teacher’ and ‘learner.’ When learners consciously engage in life as a learning experience, they bring a different intentionality to activities (Payne Citation2006).

The constellation of experiences that people may have as parents, visitors, workers, neighbors, community members, shoppers, and museum goers, among other diverse social roles, provides a plethora of possibilities for engaging with the world and connecting to environmental issues (Heimlich and Ardoin Citation2008). In this varied, yet interconnected, learningscape, people develop different repertoires of knowledge and skills, have a range of opportunities for taking action, and grow their community of family and friends who engage collaboratively in improving environmental conditions, locally and beyond, in the short and long term.

Conclusion: a rich learningscape of everyday opportunities

A broad-range approach to learning does not preclude, but rather draws together, learning that occurs in formal, nonformal, informal, and incidental contexts. Those places represent critical elements of the constellation of meaningful experiences that people encounter, deliberately or incidentally, in the course of daily living. Although traditional perspectives often privilege formal contexts (Rickinson Citation2006), this emphasis on structured settings may risk overlooking the myriad settings where environmental learning occurs on a daily basis.

Most importantly, this learningscape lens helps envision how humans are an integral part of, rather than separate from, broader social-ecological systems (Oakes et al. Citation2015; Tidball and Krasny Citation2011). While learning ecology and ecosystems approaches (e.g. Barron Citation2006; Bronfenbrenner Citation1977) place the person in the middle of the learning system, and depict how other aspects of the system act upon them, in the learningscape frame, everyday and incidental experiences provide the glue. The interstitial spaces where meaning is made become the most critical sites for everyday life learning, ensuring that what were previously unconnected, decontextualized scraps of experience become centered and contextualized. As people enact social roles while moving through everyday-life experiences, the learningscape provides structure and context, thus facilitating meaning-making.

By breaking from institutional roles and boundaries, people can, perhaps paradoxically, strengthen ties to institutions as well. People do not live within roles defined by institutional bounds such as parent here, employee there, and advocate on weekends. Rather, people move fluidly and continuously from one role to another, one setting to another.

Either intentionally or unintentionally, all kinds of socio-cultural institutions and norms have acted upon us, teaching us and reinforcing notions that learning is an isolated event, something that takes place within a school-based setting and structure. Yet the learningscape frame questions that assumption, highlighting the interconnectedness of learning experiences, emphasizing that relevance comes from connecting learning in an organic, dynamic, and holistic way to past and current experiences through constructing personal meaning (e.g. Tal and Dierking Citation2014). In this perspective, rather than erecting barriers, institutions serve to dissolve them and, even more importantly, to assist in making sense of learning moments by contextualizing them within the fabric of people’s experiences and lives. Within this view, learning expands from, ‘You’re in a nature center now,’ to, ‘This experience relates to your life in the lab, the office, at home, and in the community through these countless visible and invisible threads.’

This broadening of perspective encourages a changing vision of the role of institutions. No single institution meets all needs for every learner but, rather, each institution is part of the learning ecosystem. To understand and contextualize institutions within the everyday-life learning ecosystem requires a diverse body of literatures, research, and researchers to bring about a critical rethinking of environmental learning as, in the past, hard boundaries between fields, areas, and disciplines have prevented this fluidity. In light of current pressing environmental and societal issues, the time is ripe to (re)consider the learningscape for environmental learning research.

Following the National Research Council’s (2009) emphasis on lifelong, lifewide, and life-deep perspectives, the community has an opportunity to seamlessly connect environmental education research with that in the everyday-life sphere through a more sophisticated conceptualization not only of nonformal and informal spaces, but also of everyday-life spaces. Recognizing that it is in those interstitial spaces where people learn to become skilled, motivated community members who enact environmental behaviors, educators and researchers can more intentionally address those spaces by bringing awareness to connections across experiences to inspire environmental stewardship.

Equally important is helping learners bring their everyday experiences into discussions and considerations of issues or taking action around challenging ideas. None of the above are mutually exclusive, but rather, excitingly, they are mutually reinforcing. The environmental education community needs to help learners create explicit, seamless connections among the ordinary and the extraordinary moments of everyday life, alongside the structured and designed environmental messages we encounter daily.

Expanding the literature to embrace these broader perspectives on learning encourages and supports lifelong learners in discovering environmental education as part of the rich fabric of daily life, rather than something relegated to sixth grade or sleepaway camp. We encourage individuals to connect, make meaning, and learn about the environment and environmental issues cumulatively across and among all daily-life experiences as they move through and enact various social roles. As Heimlich, Adams, and Stern (Citation2017) prophecy, ‘Environmental education providers who make these connections explicit can help learners make connections to environmental issues, possibly leading to greater interest and action for engaging in sustainable living’ (118).

Indeed, interpreting environmental learning through the plethora of social roles encountered throughout the lifecourse and in everyday-life learning propels consideration of new methodologies, methods, approaches, settings, and colleagues. Such a re-conceptualization offers a fresh perspective on what environmental education is and can be, and connects environmental issues with people’s lives in ways that are deep, relevant, and meaningful. As such, environmental learning through everyday experiences has the opportunity to pique interest and engagement, build skills in context, and motivate participation in ongoing sustainable practices over the short and long term, for the benefit of society and the planet.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript grows from the authors’ decades’-long interest in lifelong and everyday-life learning. For discussion, support, and inspiration on this and related topics over the years, we especially thank Alison Bowers, Judy Braus, Justin Dillon, John Falk, Rachelle Gould, Elin Kelsey, Martha Monroe, Jason Morris, Alan Reid, Bill Scott, Arjen Wals, Mele Wheaton, Dilafruz Williams, and Deb Wojcik. For encouraging development of a keynote talk on this topic, we thank Cathlyn Stylinski and Ruth Kermish Allen. For editorial assistance, we thank Estelle Gaillard, Pari Ghorbani, and Marika Jaeger.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicole M. Ardoin

Nicole M. Ardoin is an associate professor at Stanford University, where she is the Emmett Family Faculty Scholar in the School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Sciences and the Sykes Family Faculty Director of the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources. She has a joint appointment in the Graduate School of Education and Woods Institute for the Environment. Nicole’s scholarship focuses on individual and collective engagement in sustainability behaviors and practices as well as people’s connections to place(s) and the ways in which those influence their relationships to each other, their communities, and the natural world.

Joe E. Heimlich

Joe E. Heimlich, Ph.D., is Senior Director for Research for COSI, a science center in Columbus, Ohio, and a researcher in COSI’s Center for Research and Evaluation. He is an Academy Professor Emeritus with The Ohio State University where he was an Extension Specialist in museums and organizational capacity building, served as the lead for environmental science with OSU Extension, and held appointments in the School of Environment and Natural Resources, the Environmental Science Graduate Program, and the College of Education and Human Ecology. Joe’s research focuses on lifelong learning about and in the environment, with interests in integration of social role, context, and conditions of the visit.

Notes

1 As another instantiation of “scapes,” Skamp discusses “learnscapes,” which focus on the intentional design and use of “natural or built, inside or outside” places, “located in, near, or beyond school grounds”—including but not limited to school gardens, ‘green’ playgrounds, and poetry corners, for example—to promote and support curricular-focused learning experiences (Skamp Citation2009, 93; Skamp and Bergmann 2001).

2 Role enhancement occurs when roles intersect and are compatible; role confusion or strain occurs when roles intersect but are not compatible or require a person to reset behaviors and expectations (Rozario, Morrow-Howell, and Hinterlong Citation2004). Role theory, more generally, and notions of role conflict, have been particularly influential and documented in the business literature (cf, Jackson and Schuler Citation1985; Parker, Morgeson, and Johns Citation2017).

3 One well-documented area of research in this realm relates to climate change: A number of studies find that people tend to seek out information in support of what they already believe (see Stylinski et al. 2017). Foundational work in this realm is discussed by psychologists such as Lord, Ross, and Lepper (Citation1979).

References

- Adler, P. A., P. Adler, and A. Fontana. 1987. “Everyday Life Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 13 (1): 217–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.13.080187.001245.

- Ardoin, N. M., and A. W. Bowers. 2021. “Environmental Education and Nature-Rich Experiences: Essential for Youth and Community Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond.” PACE Policy brief. December 9. https://edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/environmental-education-and-nature-rich-experiences

- Ardoin, N. M., and J. E. Heimlich. 2015. “Environmental Learning in Everyday Life.” In Keynote Plenary. North American Association for Environmental Education Research Symposium, San Diego, CA.

- Azevedo, F. S. 2011. “Lines of Practice: A Practice-Centered Theory of Interest Relationships.” Cognition and Instruction 29 (2): 147–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2011.556834.

- Bandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Barron, B. 2006. “Interest and Self-Sustained Learning as Catalysts of Development: A Learning Ecology Perspective.” Human Development 49 (4): 193–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000094368.

- Batt-Rawden, K., and T. DeNora. 2005. “Music and Informal Learning in Everyday Life.” Music Education Research 7 (3): 289–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800500324507.

- Bauer, J. J., and S. W. Park. 2010. “Growth is Not Just for the Young: Growth Narratives, Eudaimonic Resilience, and the Aging Self.” In New Frontiers in Resilient Aging: Life-Strengths and Well-Being in Late Life, edited by P. S. Frye and L. M. Keyes, 60–89. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Baumeister, R. F. 1994. “The Crystallization of Discontent in the Process of Major Life Change.” In Can Personality Change?, edited by T. F. Heatherton and J. L. Weinberger, 281–297. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/10143-012.

- Bean, J. 2008. 2008. “Beyond Walking With Video: Co-Creating Representation.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2008 (1): 104–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-8918.2008.tb00099.x.

- Bergs, Y., O. Mitas, B. Smit, and J. Nawijn. 2020. “Anticipatory Nostalgia in Experience Design.” Current Issues in Tourism 23 (22): 2798–2810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1669539.

- Berlyne, D. E. 1951. “Attention, Perception and Behavior Theory.” Psychological Review 58 (2): 137–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0058364.

- Berlyne, D. E. 1954. “A Theory of Human Curiosity.” British Journal of Psychology (London, England : 1953) 45 (3): 180–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1954.tb01243.x.

- Biddle, B. J. 1979. Role Theory: Expectations, Identities, and Behaviors. New York: Academic.

- Biddle, B. J. 1986. “Recent Developments in Role Theory.” Annual Review of Sociology 12 (1): 67–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.000435.

- Biggar, M., and N. M. Ardoin. 2017. “More Than Good Intentions: The Role of Conditions in Personal Transportation Behaviour.” Local Environment 22 (2): 141–155.

- Birmingham, D., and A. Calabrese Barton. 2014. “Putting on a Green Carnival: Youth Taking Educated Action on Socioscientific Issues.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 51 (3): 286–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21127.

- Blake, J. 1999. “Overcoming the ‘Value‐Action Gap’ in Environmental Policy: Tensions between National Policy and Local Experience.” Local Environment 4 (3): 257–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839908725599.

- Blewitt, J. 2006. The Ecology of Learning Sustainability, Lifelong Learning and Everyday Life. London, UK: Routledge.

- Bloom, B. S. 1976. Human Characteristics and School Learning. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Bricker, L. A., and P. Bell. 2014. “What Comes to Mind When You Think of Science? The Perfumery!": Documenting Science-Related Cultural Learning Pathways across Contexts and Timescales.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 51 (3): 260–285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21134.

- Brinkmann, S. 2012. Qualitative Inquiry in Everyday Life: Working with Everyday Life Materials. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1977. “Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development.” American Psychologist 32 (7): 513–531. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513.

- Bryant, F. B., and J. Veroff. 2017. Savoring: A New Model of Positive Experience. New York: Psychology Press.

- Callero, P. 1994. “From Role-Playing to Role-Using: Understanding Role as Resource.” Social Psychology Quarterly 57 (3): 228–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2786878.

- C’De Baca, J., and P. Wilbourne. 2004. “Quantum Change: Ten Years Later.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 60 (5): 531–541. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20006.

- Chawla, L. 1999. “Life Paths into Effective Environmental Action.” The Journal of Environmental Education 31 (1): 15–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00958969909598628.

- Chawla, L., and D. Cushing. 2007. “Education for Strategic Environmental Behavior.” Environmental Education Research 13 (4): 437–452. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701581539.

- Clark, E., N. Dibben, and S. Pitts. 2009. Music and Mind in Everyday Life. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1990. “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.” Journal of Leisure Research 24 (1): 93–94.

- Dai, H. 2018. “A Double-Edged Sword: How and Why Resetting Performance Metrics Affects Motivation and Performance.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 148: 12–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.06.002.

- Damon, W. 2009. Noble Purpose: Joy of Living a Meaningful Life. Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Foundation Press.

- Damon, W., J. Menon, and K. Cotton Bronk. 2003. “The Development of Purpose during Adolescence.” Applied Developmental Science 7 (3): 119–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_2.

- Dewey, J. 1916. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: MacMillan.

- Dewey, J. 1938. “Experience and Education.” Educational Forum 50: 241–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131728609335764.

- Doering, Z. D, and A. J. Pekarik. 1996. “Questioning the Entrance Narrative.” Journal of Museum Education 21 (3): 20–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.1996.11510333.

- Ehlman, K., M. Ligon, and G. Moriello. 2014. “The Impact of Intergenerational Oral History on Perceived Generativity in Older Adults.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 12 (1): 40–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2014.870865.

- Elder, G. H., Jr. 1998. “The Life Course as Developmental Theory.” Child Development 69 (1): 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x.

- Falk, J. H., and L. D. Dierking. 2010. “The 95 Percent Solution School is Not Where Most Americans Learn Most of Their Science.” American Scientist 98 (6): 486–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1511/2010.87.486.

- Falk, J. H., and L. D. Dierking. 2012. Museum Experience Revisited. New York: Routledge.

- Feather, N. T. 1982. Expectations and Actions: Expectancy-Value Models in Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Flaherty, M. G. 2000. A Watched Pot: How We Experience Time. New York: New York University Press.

- Fleer, M., and M. Hedegaard. 2010. “Children’s Development as Participation in Everyday Practices across Different Institutions.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 17 (2): 149–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10749030903222760.

- Gibson, C., C. Farbotko, N. Gill, L. Head, and G. Waitt. 2014. Household Sustainability: Challenges and Dilemmas in Everyday Life. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Greed, C. 2011. “Planning for Sustainable Urban Areas or Everyday Life and Inclusion.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Urban Design and Planning 164 (2): 107–119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1680/udap.2011.164.2.107.

- Guston, D. H. 2001. “Boundary Organizations in Environmental Policy and Science: An Introduction.” Science, Technology & Human Values 26 (4): 399–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/016224390102600401.

- Gould, R. K., N. M. Ardoin, M. Biggar, A. E. Cravens, and D. Wojcik. 2016. “Environmental Behavior’s Dirty Secret: The Prevalence of Waste Management in Discussions of Environmental Concern and Action.” Environmental Management 58 (2): 268–282.

- Gould, R. K., N. M. Ardoin, J. Thomsen, and N. Wyman Roth. 2019. “Exploring Connections between Environmental Learning and Behavior through Four Everyday-Life Case Studies.” Environmental Education Research 25 (3): 314–340.

- Hamilton, M. E. 2006. “Just Do It: Literacies, Everyday Learning and the Irrelevance of Pedagogy.” Studies in the Education of Adults 38 (2): 125–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2006.11661529.

- Hayden, D. 1997. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Heath, C., and D. Heath. 2017. The Power of Moments: Why Certain Experiences Have Extraordinary Impact. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Heath, S. B., and M. W. McLaughlin. 1994. “The Best of Both Worlds: Connecting Schools and Community Youth Organizations for All-Day, All-Year Learning.” Educational Administration Quarterly 30 (3): 278–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X94030003004.

- Hedgaard, M., and M. Fleer. 2019. Children’s Transitions in Everyday Life and Institutions. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Heffner, R. R., K. S. Kurani, and T. S. Turrentine. 2007. “Symbolism in California’s Early Market for Hybrid Electric Vehicles.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 12 (6): 396– 413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2007.04.003.

- Heimlich, J. E. 2019. “Queering STEM Learningscapes.” In W. Letts & S. Fifield (Ed.), STEM of Desire, 161–176. Boston: Brill Sense.

- Heimlich, J. E., and A. Reid. 2016. “Environmental Learning.” In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, edited by M. A. Peters, 1–6. Singapore: Springer-Verlag London Ltd.

- Heimlich, J. E., and J. H. Falk. 2009. “Free Choice Learning and the Environment.” In Free Choice Learning and the Environment, edited by J. H. Falk, J. E. Heimlich, and S. Foutz, 11–22. Lanham, MD: Altamira.

- Heimlich, J. E., and N. M. Ardoin. 2008. “Understanding Behavior to Understand Behavior Change: A Literature Review.” Environmental Education Research 14 (3): 215–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802148881.

- Heimlich, J., J. Adams, and M. Stern. 2017. “Nonformal Educational Settings.” In Environmental Education Review, edited by A. Russ and M. Krasny, 115–124. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Hektner, J. M., J. A. Schmidt, and M. Csikszentmihalyi. 2007. Experience Sampling Method. New York: SAGE Publications.

- Highmore, B. 2002. The Everyday Life Reader. New York: Psychology Press.

- Howell, R. A., and S. Allen. 2019. “Significant Life Experiences, Motivations and Values of Climate Change Educators.” Environmental Education Research 25 (6): 813–831. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1158242.

- Jackson, S. E., and R. S. Schuler. 1985. “A Meta-Analysis and Conceptual Critique of Research on Role Ambiguity and Role Conflict in Work Settings.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 36 (1): 16–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(85)90020-2.

- Jarvis, P. 2009. “Learning from Everyday Life.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Lifelong Learning, edited by P. Jarvis, 19–30. London, UK: Routledge.

- Kalekin-Fishman, D. 2013. “Sociology of Everyday Life.” Current Sociology 61 (5–6): 714–732. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113482112.

- Kisiel, J. F. 2014. “Clarifying the Complexities of School–Museum Interactions: Perspectives from Two Communities.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 51 (3): 342–367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21129.

- Koo, M., H. Dai, K. M. Mai, and C. E. Song. 2020. “Anticipated Temporal Landmarks Undermine Motivation for Continued Goal Pursuit.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 161: 142–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.06.002.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lefebvre, H. [1961] 2002. Critique of Everyday Life: Volume 2, Foundations for a Sociology of Everyday Life. Translated by John Moore. London, UK: Verso Press.

- Lefebvre, H. [1981] 2005. Critique of Everyday Life: Volume 3, From Modernity to Modernism (Towards a Metaphilosophy of Daily Life). Translated by Gregory Elliott. London, UK: Verso Press.

- Lefebvre, H. [1947] 1991. Critique of Everyday Life: Volume 1, Introduction. Translated by John Moore. London, UK: Verso Press.

- Lewin, K. 1935. Dynamic Theory of Personality. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lewin, K. 1936. Principles of Topological Psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lord, C. G., L. Ross, and M. R. Lepper. 1979. “Biased Assimilation and Attitude Polarization: The Effects of Prior Theories on Subsequently Considered Evidence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37 (11): 2098–2109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.11.2098.

- Lucas, A. [1972] 1991. “Environmental Education: What is It, for Whom, for What Purpose, and How?.” In Conceptual Issues in Environmental Education, edited by S. Keiny and U. Zoller. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Macnaghten, P. 2003. “Embodying the Environment in Everyday Life Practices.” The Sociological Review 51 (1): 63–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00408.

- Maffesoli, M. 1989. “The Sociology of Everyday Life (Epistemological Elements).” Current Sociology 37 (1): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001139289037001003.

- Maiman, L. A., and M. H. Becker. 1974. “The Health Belief Model: Origins and Correlates in Psychological Theory.” Health Education Monographs 2 (4): 336–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200404.

- Marsick, V. J., and K. E. Watkins. 1990. Informal and Incidental Learning in the Workplace. London, UK: Routledge.

- Marsick, V. J., and K. E. Watkins. 2001. “Informal and Incidental Learning.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 2001 (89): 25–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.5.

- Marsick, V. J., and K. E. Watkins. 2018. “Introduction to the Special Issue: An Update on Informal and Incidental Learning Theory.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 2018 (159): 9–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20284.

- Matson, P., W. C. Clark, and K. Andersson. 2016. Pursuing Sustainability: A Guide to the Science and Practice. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- McCold, P. 2008. “Protocols for Evaluating Restorative Justice Programmes.” British Journal of Community Justice 6 (2): 9–28.

- McDonald, M. G., S. Wearing, and J. Ponting. 2009. “The Nature of Peak Experience in Wilderness.” The Humanistic Psychologist 37 (4): 370–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08873260701828912.

- Milne, S., P. Sheeran, and S. Orbell. 2000. “Prediction and Intervention in Health‐Related Behavior: A Meta‐Analytic Review of Protection Motivation Theory.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30 (1): 106–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02308.x.

- Moen, P. 1996. “A Life Course Perspective on Retirement, Gender, and Well-Being.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1 (2): 131–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.2.131.

- Mony, P. R. 2007. "An Exploratory Study of Docents as a Channel for Institutional Messages at Free-Choice Conservation Education Settings." PhD diss., Ohio State University.

- Mony, P. R., and J. E. Heimlich. 2008. “Talking to Visitors about Conservation: Exploring Message Communication through Docent-Visitor Interactions at Zoos.” Visitor Studies 11 (2): 151–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10645570802355513.

- Morris, J. 2019. “The Story of Us: A Shared Narrative to Expand Our Movement.” Blog Post: Pisces Foundation, June 19. https://piscesfoundation.org/the-story-of-us-shared-narrative/.

- Myers, G., and P. Macnaghten. 1998. “Rhetorics of Environmental Sustainability: Commonplaces and Places.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 30 (2): 333–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a300333.

- National Research Council. 2009. Learning Science in Informal Environments: People, Places, and Pursuit. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.17226/12190.

- Neal, S., and K. Murji. 2015. “Sociologies of Everyday Life: Editors’ Introduction to the Special Issue.” Sociology 49 (5): 811–819. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038515602160.

- Newman, B. M., and P. R. Newman. 2017. Development through Life: A Psychosocial Approach. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Oakes, L. E., P. E. Hennon, N. M. Ardoin, D. V. D’Amore, A. J. Ferguson, E. A. Steel, and E. F. Lambin. 2015. “Conservation in a Social-Ecological System Experiencing Climate-Induced Tree Mortality.” Biological Conservation 192: 276-285.

- Oldenburg, R. 2013. “The Problem of Place in America.” In The Urban Design Reader, 285-295. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Oldenburg, R. 1999. The Great Good Place. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

- Parker, S. K., F. P. Morgeson, and G. Johns. 2017. “One Hundred Years of Work Design Research: Looking Back and Looking Forward.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 102 (3): 403–420. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000106.

- Payne, P. 2006. “Environmental Education and Curriculum Theory.” The Journal of Environmental Education 37 (2): 25–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.37.2.25-35.

- Picca, L. H., B. Starks, and J. Gunderson. 2013. “It Opened My Eyes” Using Student Journal Writing to Make Visible Race, Class, and Gender in Everyday Life.” Teaching Sociology 41 (1): 82–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X12460029.

- Pollard, A. 2003. “Learning through Life—Higher Education and the Lifecourse.” In Higher Education and the Lifecourse, edited by D. Watson and M. Slowey, 167–186. London, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.