Abstract

Environmental sustainability constitutes an important part of the political and educational context in China as it strives to move toward an ecological civilization. However, there is limited literature documenting the ways in which sustainability is embedded in higher education (HE) teaching. This qualitative research involves interviews and focus groups with 30 faculty in Business and Economics disciplines at three high-ranked Chinese Universities and offers an original exploration of how they include environmental sustainability in their teaching, and the opportunities and challenges they encounter. The findings are significant in suggesting that a broad range of sustainability concepts and aligned pedagogies are incorporated but that political and institutional culture, limitations on obtaining research data, constraints on curriculum design, and individual beliefs are significant barriers to implementation. Strategies employed by faculty to embed sustainability are investigated and reviewed in the context of the ‘theory of the second best’, previously used in UK research.

Introduction

Education for sustainable development (ESD) comprises a key strand of the international response to pressing environmental, economic, and social issues. UNESCO (Citation2016, para 1) defines ESD as ‘empowering learners to make informed decisions and responsible actions for environmental integrity, economic viability and a just society, for present and future generations, while respecting cultural diversity’. Embedding sustainability in teaching requires delivering relevant content, drawing on approaches, such as systems thinking, interdisciplinarity and critical analysis, and developing ‘pedagogical innovations that provide interactive, experiential and real-world learning’ (Lozano et al. Citation2017, 2). There is some evidence that education contributes to pro-environmental behaviors (Cotton and Alcock Citation2013; Meyer Citation2015), with university attendance having a significant positive association with commitment to environmental sustainability when compared to other adult transition pathways (Cotton and Alcock, Citation2013). However, it has also been argued that education can lead to the mindset that steers students toward an ‘individualism, materialism and hyper-rationality’ which ultimately leads to overconsumption of resources (Wals and Benavot Citation2017, 407). These issues play out differently in distinct contexts indicating a need for research into how ESD is embedded in divergent disciplines and cultural settings (Wang Citation2015, 65), and it is this that motivated our study in the Chinese context.

China presents a unique case due to its specific political and development trajectory characterized by communist philosophy, rapid economic growth, and concurrent impacts on environmental quality (Wang and Che Citation2007; Pan Citation2018). The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been addressing these issues through environmental reform and ‘Ecological Civilisation’, a term popularized by President Hu Jintao in 2007 and President Xi Jinping in 2013 (cited in Goron, 2018) and written into the Chinese constitution in 2018. The ‘ecological’ references the belief that nature is foundational to life systems and should not be subject to exploitation (Kuhn Citation2016), and ‘civilisation’ sits neatly within the CCP language of ‘spiritual civilization’ (Hansen and Liu Citation2018). Ecological civilization seeks to complement the western concept of sustainable development (environmental, economic, and social) with ‘specific features of Chinese political civilisation, aspects of Chinese governance, and core elements of the Chinese sustainable economic development agenda’ (Kuhn Citation2019). Higher education (HE), encompassing both teaching and research, is identified as critical to the successful implementation of China’s aspirational environmental reforms (Zhang Citation2010), which include building a new era of ecological civilization to promote ‘a beautiful China’ and realize ‘the Chinese Dream’ (Pan Citation2018, 3). President Xi explicitly discusses the symbiotic relationship between economic development and ecological protection, stating that ‘We prefer green water and green hill to golden hills and silver mountains’ (Pan Citation2018, 2), and the 13th governmental ‘five-year plan’ was hailed as ‘the greenest yet’ (Marinelli Citation2018). Alongside this vision of a sustainable society, however, is a sense that the term ‘ecological civilisation’ may have been harnessed for political goals and has the potential to metamorphose into a form of ‘green capitalism’ or political ‘greenwashing’ (Goron 2018).

Complicating sustainability discussions in China is the widespread resistance to expression of divergent viewpoints. There exist very strong constraints on public discussion of civil society, civil rights, universal values, legal independence, press freedom, the privileged capitalistic class, and the historical wrongdoings of the Party (‘The seven no’s’ described in Farrar Citation2013), which impact on teaching about sustainability. These constraints affect educators at all levels, with Lam (Citation2013) noting that faculty who do not observe this edict can be penalized. There is a risk therefore that rhetorical support for eco-civilization will not translate into support for environmental sustainability in the curriculum, or that a narrow conception of ESD might prevail.

Chen (Citation2019) notes that since the turn of the millennium ‘the pursuit of ecologically sustainable development has been increasingly incorporated into the policies and programs of Chinese higher education’ (1088). Encouraged and funded by the Ministries of Environmental Protection (MoEP) and Education (MoE) two strategies for embedding have emerged: Several prestigious universities have developed expertise in ESD (including Tongji, Beijing Normal, Tsinghua, Renmin, and Fudan) and more widely, universities have developed sustainability-related content for students. Chinese educators have adapted existing educational philosophies, such as Confucianism to provide a culturally nuanced conceptualization of ESD (Perez and Shin Citation2016) and more than 50% of Chinese Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) have implemented ESD curricula since 1997 (Niu, Jiang, and Li Citation2010). Both Confucianism – especially the latter thinkers who emphasized an ecological turn (Tu Citation2001) – and Taoism, with its focus on compassion, harmony, and cooperation (Zu Citation2019) offer helpful ways of thinking about human-nature connections and sustainability which set the context for the development of sustainability in China.

It has been claimed that a lack of strategic planning for ESD in China has led to low institutional capacity (Han Citation2015). Xiong et al. (Citation2013) claim that 19% of HEIs have no provision and that, where developments have taken place, they are concentrated in Agriculture, Forestry, and Engineering disciplines or presented in generic introductory modules. ESD pedagogies promoted by UNESCO (Citation2009), including participatory decision making, critical thinking, and problem solving are limited in conventional teaching in China (Yang, Lam, and Wong Citation2010; Wong, Long, and Elankumaran Citation2010). These factors may constrain the extent to which faculty in different disciplines see ESD as relevant (Li Citation2013) and may even lead to active resistance (Zhao and Zou Citation2015).

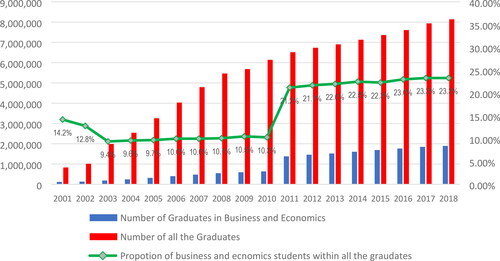

China’s HE sector is considerable, consisting of over 2600 universities and 26 million students (National Bureau of Statistics of China Citation2017), with Economics and Business disciplines being large and growing areas for study (see ). According to the Catalogue of Undergraduate Courses of General Higher Education published by the Ministry of Education (2021), there are 23 majors within the discipline of economics and 40 majors within the discipline of business. By the end of 2018, the number of graduates in business and economics in China was 1.893 million (including students with bachelor’s and master’s degree, and diploma), compared with 1.378 million in 2011, a cumulative increase of 515,000. The statistics show that business and economics accounted for 23.3% of the total number of graduates in 2020, and the proportion has shown a steady increase in a decade (National Bureau of Statistics of China Citation2021).

As well as being important due to the high student numbers in Business and Economics disciplines in China, we argue that these subjects offer a crucial context for ESD research and practice, since they focus on production, allocation, use of goods and services, and organizational management and decision-making. Current economic and business practices are largely embedded in neo-liberal capitalist forms of production and consumption which favor exponential economic growth based on the exploitation of finite resources. This takes place in a global context of rising population, middle-class consumer demand, and expanding industries (Meadows, Randers, and Meadows Citation2004). These processes have a disproportionate and often negative impact on people and the environment and are particularly acute in countries experiencing newly advanced economic development, of which China is a classic example. Re-prioritizing business and economics practices are of paramount concern therefore, and HE can (and should) play an important role in educating future leaders in these disciplines (Fryxell and Lo Citation2003).

The extent to which Business and Economics disciplines in China have taken up the ESD challenge is questionable. Du, Su, and Liu (Citation2013) claim both subjects are weak at cultivating students with values and skills favorable toward sustainability. Xiong et al. (Citation2013) presented a ‘Green Curriculum’ audit of Chinese HE in which Economics ranked 8th of 12 disciplines, and Wong, Long, and Elankumaran (Citation2010, 16) argue that Chinese ‘Business schools need to be more aggressive in informing students that sustainability is indispensable to the profitability equation’. There are recognized tensions between Confucian educational norms and advocated sustainability pedagogies, and Fryxell and Lo (Citation2003, 60) argue that Chinese Business schools are ‘resource constrained in using active and involving pedagogies’. Comparative research by Huang and Wang (Citation2013) suggests that Chinese business schools are less likely to offer sustainability-related courses than those in the US. However, this research was based on published information about curricula which does not always reflect what happens in practice. There is also considerable evidence that business schools outside of China have failed to foreground sustainability in their practices (Edwards et al. Citation2020), hence there is merit in exploring where the opportunities for its inclusion might occur.

Despite the importance of ESD in Chinese HE, there is a paucity of literature about how it is embedded into specific disciplines by faculty operating under these conditions (Han Citation2015; Zou et al. Citation2015). Our research addresses this gap by exploring how faculty in Economics and Business disciplines conceptualize and negotiate ESD in their practice. To explore these issues, the research team focused on the following questions:

How do Chinese faculty in Economics and Business disciplines understand sustainability in the context of their discipline?

How do they integrate sustainability into curricula?

Methodology

This research utilized an instrumental case study approach (Stake Citation1995), involving qualitative methods (interviews and focus groups) as befits a complex, multi-layered issue, such as sustainability. The research was carried out in three Chinese universities chosen to reflect (Xiong et al. Citation2013; Wu and Zheng Citation2008) findings that sustainability is better embedded when the institution is in an Eastern major city, funded by the Ministry of Education and holds membership of the reform initiative groups, Project 211 and 985 ().

Table 1. Sample.

Ethical approval was obtained through the lead author’s institution prior to any data collection taking place. Informed consent was given by all participants through verbal agreement in response to an information sheet to avoid the necessity for storing signed consent forms with the names of participants included. Care was taken to ensure anonymity for the participants given the political context in which they were working. Recruitment took place via gatekeepers at each institution who arranged access. Data collection was conducted in China by the UK authors and took place in English and Chinese; in the latter cases via an (institutionally selected) translator.

The schedule for all interviews was piloted prior to data collection which prompted extensive critique of the implications of concept translation, language, cultural difference, and the cultural other (Savvides et al. Citation2016). The final schedule was a semi-structured format which introduced faculty to a list of sustainability-associated concepts and asked them to identify the extent to which these were embedded into their teaching (). To allow respondents to articulate their own culturally relevant conceptions of sustainability as related to their discipline, definitions of sustainability, and of the concepts were not provided.

Table 2. Sustainability concepts.

The interviews also explored personal beliefs about sustainability, resources for ESD, curriculum content, pedagogy, and student engagement. Each interview lasted between one and two hours and was digitally recorded and transcribed. Data were analyzed collaboratively by the research team, undertaking a rigorous thematic analysis using the constant comparative method to draw out cross-cutting themes (Silverman Citation2005). This involved detailed coding of the transcripts, with codes being mapped against research questions in the first stage. Once codes had been agreed, coding was undertaken by two individuals independently who compared their findings and resolved any discrepancies through discussion. This was followed by a collaborative analytic process of reading and re-reading data within and across codes, mapping against the research questions and looking for similarities and relationships between phenomena to create robust understandings about faculty ESD beliefs and practices.

A limitation of this study is its relatively small sample size (30 faculty were involved in total). However, the rich data elicited offer strong insights into the experiences of faculty at these universities. It is important to note that the universities studied were all prestigious institutions which cannot be said to reflect the situation across the very diverse Chinese HE sector. Many of the faculty interviewed will have obtained their PhDs in western countries or have other experience of working overseas so this is a very particular group. However, the Chinese government’s strategy for introducing reform (including ESD, see Wu and Zheng Citation2008) consistently involves embedding into top-ranked institutions with anticipated diffusion to other levels. What happens in these universities is therefore of wider interest and, given the limited research in this area, the research findings offer original insights.

Results

Results from the interviews are presented aligned with the two research questions. Extracts from the interviews are given using the coding (case: interviewee number).

Research Question 1: How do Chinese faculty in Economics and Business disciplines understand sustainability in the context of their discipline?

RQ1a: Sustainability, environment, and development

Respondents talked about a tension between environmental protection and development when explaining their understanding of sustainability. Frequently, faculty understood sustainability primarily as an environmental quality issue (referring explicitly to local pollution issues for example). 11/20 interviews saw environmental degradation as a necessary part of economic development (Grossmann and Krueger 1993), and respondents in 8/20 interviews identified the ‘West’ as successfully achieving both advanced development and environmental quality:

For most large countries [the Kuznets curve applies]. For some small countries I think it is different, but for large countries like China, we cannot escape.(1:1)

There appears to be a conflict between economic development and environmental protection but look at Europe. There is harmony. (2:10)

There was an acceptance that mainstream economic and business theories were developed within democratic free-market settings at a point in history when environmental degradation was less pronounced, and that this was quite distinct from the current situation in China. However, despite the potential for developing new theories, there was little appetite for such work:

Chinese environmental economists, including myself, we only contribute to policy … I don’t think it’s time for us to have a new theory about this. The West are very successful in this area. (2:6)

Surprisingly, given the high status of the universities and faculty involved, 4/20 interviews demonstrated an apparent lack of confidence in generating sustainable development theory. Nonetheless, 10/20 reported that sustainable development would continue to influence disciplinary content in China, confirming the importance of environmental considerations in teaching:

Attention to environmental issues is increasing in China. More environmental topics are added to the Business syllabus every year…the sustainability word is being constantly repeated. (3:1)

This interest was attributed by 14/20 to government policies which, since the 11th Five Year Plan (2006–2010), have encouraged sustainable development and green economy initiatives including Green Gross Domestic Product. Respondents identified growing popular discontent with poor environmental conditions as also being influential (8/20).

RQ1b: Key concepts in sustainability for business and economics

We were keen to allow our interviewees to express their own understandings of sustainability, so we did not offer a definition of either this term, or the key concepts we shared with them (see ). A hard copy of this table was used as a prompt for conversation in the interviews, offering us a deeper understanding of the elements of sustainability which most resonated in this context. Whilst most respondents expressed the view that sustainability was important, 6/20 interviewees stated that none of the sustainability concepts () were relevant to their discipline. Amongst others, the most frequently mentioned concepts were Interdependence, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and growth. Faculty from both disciplines reported using these concepts; however, those from Environmental Economics and Business were most familiar with them. When talking about Interdependence of society, economy, and environment, there were frequent references to the balance or perceived trade-off between environment and economic growth, and surprisingly few references to the green economy:

We need to compromise. It’s not that environmental is everything. Because people personally need to survive. Especially in the poorer area. They first need a job and then think about environmental protection. (2:8)

This issue was in sharp relief in the Chinese context, where many of the population still live in poverty with little access to good healthcare and education.

Key issues of resource depletion and pollution (of air, water, and soil) in China were raised repeatedly (8/20) across a range of interviews:

No one can escape! Different parts of China suffer with water and soil pollution to different degrees, this has caused pollution of agricultural products, but everyone suffers with air pollution. (3:3)

Overall, the Economists were more likely to discuss concepts in terms of resource use, supply and demand, and growth and profit (rooted in neo-classical economic principles, Weintraub (Citation2007)). Business faculty was more familiar with social dimensions, such as CSR which they saw as key to the discipline. Rights and responsibilities, Human capital and Equity, and justice were less cited by all.

RQ1c: Sustainability and Chinese culture

The importance placed on interdependence by respondents may have been linked to Chinese cultural norms, such as ‘harmony’, which was mentioned frequently by interviewees. The second-ranked concept, CSR, has been linked explicitly in the literature with Taoism (Zu Citation2019), so it may be that these concepts aligned well with the cultural perspectives of respondents. Several respondents specifically mentioned the similarity between Chinese culture and sustainability:

Before, sustainable development, I think if you look at the culture of Chinese, Asian histories, there is a lot of sayings that almost the same, about sustainable development. (2:1)

In traditional Chinese culture, sustainable development is actually very important – even more important than current profit. So, in Chinese culture it says, ‘you can’t take all you can get because you have to leave some for future generations’. (2:10)

Inter-generational equity resonated with many respondents as it tapped into concerns about family which are strong in Chinese culture. Indeed, some respondents felt that there would be value for international ESD communities of learning more about Chinese culture and context:

Maybe we will export my country’s culture and values to the world. (2:6)

However, one felt that the influence of traditional culture had been weakened, undermining some of these traditional beliefs connected to sustainability, such as inter-generational equity:

In traditional Chinese culture, sustainable development is actually very important – even more important than current profit. So, in Chinese culture it says, ‘you can’t take all you can get because you have to leave some for future generations.’ But I feel the Chinese culture has been interrupted … We lost our traditional values, but we haven’t established new ones. (3:10)

It’s important to note, however, that our participants were faculty members in economics and business majors which are westernized disciplines – and most respondents had engaged in some education in the west. This may have impacted on their perceptions of classical Chinese philosophy.

Research Question 2: How do Chinese faculty in Economics and Business disciplines integrate sustainability into curricula?

RQ2a: Teaching about sustainability

There were varied responses from faculty about how important sustainability was for their curriculum, and this influenced how (and whether) they attempted to integrate it in the curriculum. Economists were more likely to state that sustainability was not relevant (aside from Environmental Economists). In Business, there were many more examples relating to ethical business products and practices:

CSR is very close to our discipline because it serves households and businesses in the economy …we pay attention to social responsibility and environment. (2:5)

We have a chapter named ‘Business ethics and social responsibility’ e.g. consumption, bribery, cheating, aggressive financial objectives vs social responsibility and contribution to the nation state and society’. (3:4)

However, faculty in 12/20 interviews stated that students should learn about sustainability irrespective of discipline and in each location identified first-year introductory modules on civic life that might include sustainability (13/20):

Every student should know about it. We have a course called ‘ideological and moral cultivation and foundation of law’ it is a core course and students have a topic in that about sustainable development or similar. (3:2)

Faculty also discussed different pedagogic approaches they use for teaching about sustainability in their discipline. Although lecturing was preferred (20/20), interactive pedagogies, such as class discussions, role play, presentations, and group work were reported frequently (13/20). However, there were no reports of fieldtrips, placements or internships, and some respondents noted that students struggled with interactive approaches. 5/20 interviews made links to employability where prospects were in a very specific ‘green’ field but 6/20 claimed there was no link between sustainability and employability.

Although it is useful for human beings to know about this it is not useful for their careers. Depending on what sort of job they do, it’s not really considered very professional. (3:2)

It’s evident that there were very mixed views as to whether and how sustainability should be included in the curriculum.

RQ2b: Contextualizing sustainability in the Chinese context

In all cases, faculty used overseas textbooks and it was noted in 14/20 interviews that sustainable development had begun to appear in these, in contrast to Chinese textbooks:

The last chapter of the textbooks is always about environmental governance. (2:9)

Even if in the Chinese textbooks some of this is covered it will be a section of one chapter at most. Chinese books will only cover sustainable topics in a limited way. (3:3)

A common approach was to use the textbook as a baseline but to incorporate teaching of specific case studies which were from a Chinese context to make the discipline more accessible and relevant to students, though one had written their own textbook to contextualize theory in a Chinese context:

If you teach a course on development economics, you start with the international but use local papers … Chinese examples, Chinese stories, Chinese research. (1:6)

Faculty had variable autonomy to influence the curriculum. In Case 1, curricula were decided by local committees and delivered primarily through textbooks. In Cases 2 and 3 (the more research focused HEIs), textbooks formed only part of the repertoire and there were more examples of local case studies (11/20) or real-world issues (8/20).

We frame the corruption as a service issue … We use this framework to show why corruption occurs and why it is an issue in China. We have lots of supply and lots of demand! (2:7)

I pay more interest to climate change and fair trade because in China we really suffer from air pollution, so we need to find new source of energy. (3:8)

The need to contextualize sustainability was the inverse problem to that often encountered in western contexts, where efforts are being made to internationalize the curriculum. In China, the need was to localize the curriculum to make it more accessible to Chinese students.

RQ2c: Opportunities and challenges for integrating sustainability in the curriculum

Where faculty did have more control over the curriculum, individual beliefs about the relevance of sustainability could manifest in curriculum content, and faculty with strong personal beliefs about the importance of sustainability were more likely to find opportunities to integrate it:

There’s no regulation, nothing from the department to say I must teach [sustainability], I just choose to because it is important. (2:4)

However, several consistent barriers to integration were reported. Faculty in 10/20 interviews reported that obtaining reliable datasets was fraught with difficulty and this had implications for their ability to teach about business and economics issues – especially when Chinese case studies were needed to contextualize the (mainly US or UK) textbooks in use:

The government hide the data on purpose. We don’t have a complete database to work on and study. Environmental data is confidential. It’s impossible to say what is serious. (2:2)

The government cannot get enough information from the firms. The firms hide information to let policy be ineffective. The government has intentions to hide information and not let the public have the facts. (2:9)

There were solutions to this issue, with respondents describing ways of accessing additional data online often through international websites, but faculty were often uncertain about the reliability of different online sources:

We only get information from the website but we don’t know whether it’s true or not. Audio or some newspapers they are all related to the government, so they speak in one tongue. But we can hear a different voice online. We don’t know if it’s true, but we hear voices. (2:2)

In addition, social justice themes were taught infrequently with 5/20 interviews referring to restrictions on curricula content and 4/20 describing subversive responses to this:

You cannot say that the policy of the Chinese government is not good, you cannot criticise communism…you can joke about politics with students, but you cannot put this on the PowerPoint slides. (3:1)

We can’t talk publicly too much about some of the concepts in China. We can’t talk about the rights and responsibilities between government and people in China. You can talk, like chat, but you don’t make public or teach about it. (2:2)

Other content was less provocative but still controversial. For example, values are integral to understanding and teaching about sustainability, but these were rarely seen as appropriate for inclusion (3/20), instead being considered part of students’ development as ‘good’ citizens outside a formal educational context. It was clear that there were distinctive Chinese ways of thinking – for example around respecting others’ opinions and authority which influenced the way in which they approached teaching about contested issues.

Discussion

Our findings both challenge and support elements of the extant literature. The data indicate that sustainability was often understood in quite a narrow way by faculty in our study, and that environmental protection and development were often viewed as in tension. This aligns with previous research – e.g. Sylvestre, Wright, and Sherren (Citation2013) in Canada, which noted the prevalence of a view of sustainability as ‘a zero sum game’ – so this is clearly not a view that is specific to the Chinese context. The findings also indicated that the Business curriculum was seen as more cognate with ESD than economics, though across both disciplines there were examples of ESD commitment from faculty. Our findings on the most popular content for inclusion in the business curriculum echo earlier research by Huang and Wang (Citation2013) in terms of interest in CSR – but contrast with their findings in illustrating less enthusiasm for teaching about ethics and environmental stewardship. Overall, we found a relatively limited range of sustainability concepts being considered within both disciplines.

We found some evidence – even within this group of faculty with significant western educational experience – of a nuanced Chinese understanding of sustainability reflecting cultural norms, such as harmony, balance, and inter-generational equity. This is similar to the sustainability-related discourses identified by Liu et al. (Citation2018) in their analysis of Chinese newspaper articles, suggesting that the views of faculty are influenced by the wider cultural milieu. Liu et al. (745) argue that:

This discourse was created by the CCP through a strong network among the economic, environmental and social dimensions of sustainability based on the traditional idea of “harmony,” to underpin its regime. To affirm the benefit of adding Chineseness in the notion of sustainability, this Chinese discourse of sustainability is declared to be more advanced than the sustainable development concepts created in the West.

Within our dataset, we can identify a tension between this idea of ‘harmony’ between the different dimensions of sustainability which emerges in some places – and the expressed conflict between environment and development which appears elsewhere. It is possible that the intermingling of western and Chinese conceptions of sustainability leads to an apparent dissonance between the ideal of living in harmony with the environment versus the reality of being in a fast-developing country. Further work to explore faculty understandings of sustainability in different disciplinary and national contexts would be of interest to offer a wider perspective on sustainability understandings and norms in HE.

In terms of integrating sustainability into the curriculum, faculty had mixed views about the relevance to their discipline and how (if at all) sustainability concepts should be included in teaching. A range of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for inclusion of environmental sustainability were cited, and greater use of interactive pedagogies than the literature might suggest. There was evidence of active pedagogies in use – as advocated for learning sustainability content (Longhurst et al. Citation2014). However, there were no reports of deliberately aligning sustainability content and pedagogy or ‘authentic experiential learning’ in the form of fieldtrips, placements, or internships. Links between sustainability and employability were not identified by many of our participants, indicating that there may be less pressure on faculty to focus on sustainability skills than in some other contexts (see Ryan and Cotton Citation2013). However, current debates about Chinese graduates’ readiness for the job market, including the claim that they lack ‘soft skills’ (Molnar, Wang, and Gao Citation2015) may enhance links between sustainability and employability in future. Another push in this direction might come from the Chinese government’s increasing commitment to both Application Oriented Education and Ecological Civilization, focusing on solving the issues caused by climate change, on energy transformation, and on cultivating the renewable energy sector (Wang-Kaeding Citation2018).

Faculty ‘perceptions and attitudes greatly influence how students learn and think about at the world around them’ (Li Citation2013, 29). Yuan and Zuo (Citation2013) report that Chinese faculty ranked sustainable curricula the least important factor in a green university and were no more knowledgeable about sustainable development than other stakeholders including students, parents, and alumni (see also Duan and Fortner Citation2005). Overall, our findings suggest that ESD is finding its way into the curriculum but is not yet legitimately accepted and adopted by all faculty or universities. There remain structural barriers to integrating sustainability into the business and economics curriculum in China. Whilst some of these replicate issues identified in other international settings, others are specific to the Chinese context. Arguably, one of the greatest needs for faculty in China, as in other countries, are programs for faculty professional development in sustainability literacy. Considering these findings, the authors recommend embedding sustainability in educational development work – which is a fast-developing field across China. This would open up opportunities within curricula for embedding ESD and allow faculty to explore the alignment between sustainability and employability.

To help understand the constraints that limit further embedding of sustainability in HE, it is useful to consider the ‘theory of the second best’ (Lipsey and Lancaster Citation1956, 7). This economic theory was first used in a sustainability context by Cotton et al. (Citation2009), and has subsequently been drawn on to help understand a range of sustainability issues (e.g. Baughan Citation2015). It offers a conceptual structure which helps explain how adaptation of ESD teaching can offer a rational response to constrained circumstances. As Cotton et al. (Citation2009, 730) note:

…if the first-best state is unattainable, it may be more productive to adopt the next-best alternative than to strive to maintain the conditions relevant to the first best.

In the UK context, issues such as the prevalence of didactic teaching approaches, and concerns about relevance to the discipline emerged as curbs on the ‘ideal state’ of fully transformative ESD practice. In the Chinese context, these issues remain but others (such as the lack of available local data and case studies as well as the restrictive political context) emerge, leaving faculty with difficult choices to make about how much risk they are prepared to take in terms of pushing the boundaries of allowable curriculum content.

Access to data and restrictions on what can be taught are part of the wider institutional and social milieu and are not easily remedied; however, recent research emerging from China illustrates the ways in which academics are negotiating these conditions (Feng and Newton Citation2012; Lam Citation2013) as well as the restrictions on teaching about politically controversial issues, such as civil society, civil rights, and universal values (Farrar Citation2013). Hao and Guo (Citation2016) discuss various ways in which faculty conform to, and resist, constraints on academic freedom – and describe an ‘ideal-type’ role of ‘establishment/organic’ intellectuals, whose primary loyalty is to the party-state (a position echoed by several participants in our research). However, there is some evidence of the ‘non-establishment/professional’ roles being played by faculty in our study: while not necessarily in wholehearted support of government policy, they maintain a safe distance from politics and focus narrowly on their discipline. Hao and Guo (Citation2016, 1048) quote professors who explain that ‘It’s better if we don’t touch on sensitive issues in class or in writing’, and this was clearly the position of some of our interviewees. Arguably, however, this limits opportunities to conduct the wider inter-disciplinary and creative thinking and collaboration that might constitute a ‘first best solution’ in this context. It certainly limits ability to include the full range of potential ethical issues in the business curriculum (discussion of corruption or human rights for example), and there is only limited evidence of faculty using the kind of interactive, experiential pedagogic approaches which are appropriate for teaching about sustainability or controversial issues (Cotton et al. Citation2007).

It may be that a second-best solution is to be found here in ‘obedient autonomy’, a concept introduced by Evasdottir (Citation2004) in her ethnographic study of archaeology students and faculty in China, and subsequently used by Hao and Guo (Citation2016). Evasdottir (Citation2004, x) describes obedient autonomy as ‘a self-directed control over change that takes effect only through the concerted effort to achieve and maintain a discourse of order and immutability’. In our study, the role of ‘obedient autonomy’ can be seen in faculty who, for example, use informal discussion with students to incorporate potentially controversial issues. They (wisely) do not directly confront the system, however, as Hao and Guo (Citation2016, 1045) write: ‘The individual effects change by participation in the system and not in its destruction’. Interestingly, this has strong echoes of the Cotton et al. (Citation2009) study in which (whilst the UK context is significantly less constrained than here) the use of covert methods to incorporate sustainability into the curriculum was revealed. In the light of recent UK government guidance that warns teachers against using resources from anti-capitalist organizations and certain environmental campaign groups, such as Extinction Rebellion (Mohdin Citation2020), strategies for maintaining academic freedom within an ever-more authoritarian culture may become increasingly pertinent.

Future research in this field could usefully explore the extent to which these findings are representative of other disciplines in Chinese HE. Understanding more about how ESD is realized in the world’s largest HE sector is of obvious interest to scholars. The recent and growing interest in international comparisons of ESD progress also offers potential to ascertain whether the experiences of faculty in Business and Economics in other national contexts align with those recorded here.

Conclusion

In this article, we have argued that the integration of sustainability into Business and Economics disciplines in Chinese HE can be viewed as a ‘second best solution’ to a constrained context. Illustrated here are rational and creative responses by faculty to a situation where they may be required to take on multifaceted identities to conduct their work. The concept of sustainability as relevant to the business and economics disciplines is revealed as important but also risky, in terms of the political constraints on educators, and thus problematic for faculty and students to engage with. Although this study was focused on only these two disciplines in three institutions, a number of the findings are potentially transferable to other subjects or other universities, as faculty in China work under similar constraints.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

J. Winter

Professor Jennie Winter is a Professor of Academic Development at Plymouth Marjon University, UK. She is a National Teaching Fellow and serves on the editorial board for several pedagogic research journals. Professor Winter is a Principal Fellow of the UK HE Academy and represents the Staff and Educational Development Association (SEDA) on their Research and Scholarship committee. She is interested in a range of academic development themes including student voice, education for sustainable development and evidencing the impact of educational development. Significant recent work includes national research projects on evaluating the impact of educational development and student academic representation in UK HE. Professor Winter undertakes educational development overseas including in the USA and China and her research has been utilized by the European Commission, presented at international conferences and by invite to selected institutions. You can find out more about her work here: https://www.marjon.ac.uk/about-marjon/staff-list-and-profiles/winter-jennie.html. . .

J. Zhai

Dr Junqing Zhai is an associate professor at the School of Education, Zhejiang University, China. He has a doctorate from King’s College London, which focused on pedagogies in informal science settings. Prior moving back to China, Junqing worked as a research fellow at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, where he had the opportunity to explore inquiry-based teaching and learning in school science classrooms. Junqing’s current work concerns reconnecting urban children to nature through outdoor learning in botanical gardens.

D. R. E. Cotton

Professor Cotton is Director of Academic Practice at Plymouth Marjon University, UK. She is a Principal Fellow of the UK Higher Education Academy (PFHEA), and a National Teaching Fellow, and was selected by the UK government Office for Students to work as an assessor and panel member on the UK Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF). She has a doctorate from Oxford University, which focused on teaching controversial environmental issues, and is a popular invited speaker having delivered workshops and keynotes on higher education in Europe, China, the US, and South Africa. Professor Cotton sits on the editorial board of three journals, has contributed to upwards of 25 projects on pedagogic research and development, and produced more than 70 publications on a wide range of HE teaching and learning issues including sustainability education, widening participation, and internationalization of higher education. She works as a consultant for Eurasia University in Xi’an, China. You can find out more about her publications here: https://scholar.google.co.uk/citations?hl=en&user=XWbHd_UAAAAJ. . .

Notes

1 Practicalities of gaining access meant that focus groups had to be used in this HEI. Owing to the difficulty of identifying individual contributors, each focus group is treated as a single source in reporting, hence references to 20 ‘interviews’ for ease of reading, though 30 individuals were involved.

References

- Baughan, P. 2015. “Sustainability Policy and Sustainability in Higher Education Curricula: The Educational Developer Perspective.” International Journal for Academic Development 20 (4): 319–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1070351.

- Chen, X. 2019. “Harmonizing Ecological Sustainability and Higher Education Development: Wisdom from Chinese Ancient Education Philosophy.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 51 (11): 1080–1090. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2018.1501677.

- Cotton, D. R. E., M. F. Warren, O. Maiboroda, and I. Bailey. 2007. “Sustainable Development, Higher Education and Pedagogy: A Study of Lecturers’ Beliefs and Attitudes.” Environmental Education Research 13 (5): 579–597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701659061.

- Cotton, D., I. Bailey, M. Warren, and S. Bissell. 2009. “Revolutions and Second-Best Solutions: Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (7): 719–733. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802641552.

- Cotton, D. R. E., and I. Alcock. 2013. “Commitment to Environmental Sustainability in the UK Student Population.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (10): 1457–1471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.627423.

- Du, X., L. Su, and J. Liu. 2013. “Developing Sustainability Curricula Using the PBL Method in a Chinese Context.” Journal of Cleaner Production 61: 80–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.01.012.

- Duan, H., and R., F. Fortner. 2005. “Chinese College Students’ Perceptions about Global versus Local Environmental Issues.” The Journal of Environmental Education 36 (4): 23–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.36.4.23-58.

- Edwards, M., P. Brown, S. Benn, C. Bajada, R. Perey, D. Cotton, W. Jarvis, G. Menzies, I. McGregor, and K. Waite. 2020. “Developing Sustainability Learning in Business School Curricula – Productive Boundary Objects and Participatory Processes.” Environmental Education Research 26 (2): 253–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1696948.

- Evasdottir, E. E. S. 2004. Obedient Autonomy: Chinese Intellectuals and the Achievement of Orderly Life. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

- Farrar, L. 2013. “China bans 7 topics in university classrooms.” The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/China-Bans-7-Topics-in/139407

- Feng, L., and D. Newton. 2012. “Some Implications for Moral Education of the Confucian Principle of Harmony: Learning from Sustainability Education Practice in China.” Journal of Moral Education 41 (3): 341–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2012.691633.

- Fryxell, G., and C. W. H. Lo. 2003. “The Influence of Environmental knowledge and values on Managerial Behaviours on Behalf of the Environment: An Empirical Examination of Managers in China.” Journal of Business Ethics 46 (1): 45–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024773012398.

- Goron, C. 2018. “Ecological Civilisation and the Political Limits of a Chinese Concept of Sustainability.” China Perspectives 4: 39–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.8463.

- Grossman, G. M., and A. B. Krueger. 1993. “Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement.” In The Mexico-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, edited by P. M. Garber, 13–56. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Han, Q. 2015. “Education for Sustainable Development and Climate Change Education in China: A Status Report.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 9 (1): 62–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408215569114.

- Hansen, M., and Z. Liu. 2018. “Air Pollution and Grassroots Echoes of “Ecological Civilization” in Rural China.” The China Quarterly 234: 320–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741017001394.

- Hao, Z., and Z. Guo. 2016. “Professors as Intellectuals in China: Political Identities and Roles in a Provincial University.” The China Quarterly 228: 1039–1060. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741016001442.

- Huang, S. K., and Y. L. Wang. 2013. “A Comparative Study of Sustainability Management Education in China and the USA.” Environmental Education Research 19 (1): 64–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.687046.

- Kuhn, B. 2016. “Sustainable Development Discourses in the P.R.” Journal of Sustainable Development 9 (6): 158–167. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v9n6p15.

- Kuhn, B. 2019. Ecological Civilisation in China. DOC Research Institute. https://doc-research.org/2019/08/ecological-civilisation-china-berthold/.

- Li, J. 2013. “Environmental Education in China’s College English Context: A Pilot Study.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 22 (2): 139–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2013.779124.

- Liu, C., L. Chen, R. Vanderbeck, G. Valentine, M. Zhang, K. Diprose, and K. McQuaid. 2018. “A Chinese Route to Sustainability: Postsocialist Transitions and the Construction of Ecological Civilization.” Sustainable Development 26 (6): 741–748. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1743.

- Lam, W. 2013. Xi and China’s Seven Taboos. Bonn, Germany: Deutsche Welle, Made for Minds. Accessed 25November 2021. https://www.dw.com/en/opinion-xi-and-chinas-seven-taboos/a-16870412

- Lipsey, R. G., and K. Lancaster. 1956. “The General Theory of Second Best.” The Review of Economic Studies 24 (1): 11–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2296233.

- Longhurst, J., L. Bellingham, D. Cotton, V. Isaac, S. Kemp, S. Martin, C. Peters, et al. 2014. Education for Sustainable Development: Guidance for UK Higher Education Providers. London: QAA Publication.

- Lozano, R., M., Y. Merrill, K. Sammalisto, K. Ceulemans, and F., J. Lozano. 2017. “Connecting Competences and Pedagogical Approaches for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: A Literature Review and Framework Proposal.” Sustainability 9 (10): 1889–1904. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101889.

- Marinelli, M. 2018. “How to Build a ‘Beautiful China’ in the Anthropocene. The Political Discourse and the Intellectual Debate on Ecological Civilization.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 23 (3): 365–386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-018-9538-7.

- Meadows, D., R. Randers, and D. Meadows. 2004. Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co.

- Meyer, A. 2015. “Does Education Increase Pro-Environmental Behaviour? Evidence from.” Ecological Economics 116: 108–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.04.018.

- Mohdin, A. 2020. “Legal threat over anti-capitalist guidance for schools in England.” The Guardian, 1st October 2020. Accessed 06 October 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/oct/01/legal-threat-governments-anti-capitalist-guidance-schools-political

- Molnar, M., B. Wang, and R. Gao. 2015. “Assessing China’s Skills Gap and Inequalities in Education.” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1220. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2017. “China statistical yearbook number of enrolments of formal education by type and level.” http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2017/indexeh.htm

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2021. Catalogue of Undergraduate Courses of General Higher Education. Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road, New Delhi, India: Ministry of Education.

- Niu, D., D. Jiang, and F. Li. 2010. “Higher Education for Sustainable Development in China.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 11 (2): 153–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371011031874.

- Pan, X. 2018. “Research on Xi Jinping’s Thought of Ecological Civilization and Environment Sustainable Development.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 153: 062067. Accessed 06 October 2020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/153/6/062067/pdf

- Perez, A., and M. H. Shin. 2016. “Study on Learning Styles and Confucian Culture.” Indian Journal of Science and Technology 9 (1): 1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i47/101908.

- Ryan, A., and D. Cotton. 2013. “Times of Change: Shifting Pedagogy and Curricula for Future Sustainability.” In The Sustainable University: Process and Prospects, edited by S. Sterling, L. Maxey, and H. Luna, 151–167. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Savvides, N., J. Al-Youseff, M. Colin, and C. Garrido. 2016. “Methodological Challenges: Negotiation, Critical Reflection and the Cultural Other.” In Revisiting Insider-Outsider Research, edited by M. Crossley, L. Arthur, and E. McNess, 113–129. Providence, RI: Bristol Papers in Education: Comparative and International Studies. Symposium Books. doi:https://doi.org/10.15730/books.93.

- Silverman, D. 2005. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Stake, R. E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. London: Sage.

- Sylvestre, P., T. Wright, and K. Sherren. 2013. “Exploring Faculty Conceptualizations of Sustainability in Higher Education: Cultural Barriers to Organizational Change and Potential Resolutions.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 7 (2): 223–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408214526491.

- Tu, W. 2001. “The Ecological Turn in New Confucian Humanism: Implications for China and the World.” Daedalus 130 (4): 243–264. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20027726?origin=JSTOR-pdf

- UNESCO. 2009. ESD Currents: Changing Perspectives from the Asia-Pacific. Bangkok, Thailand: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2016. “What is ESD”? https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development/what-is-esd

- Wals, A. E. J., and A. Benavot. 2017. “Can we Meet the Sustainability Challenges? The Role of Education and Lifelong Learning.” European Journal of Education 52 (4): 404–413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12250.

- Wang, G., and Y. Che. 2007. “Integration of Environment Education and TEFL: A Perspective of Global Education.” Journal of Kunming University of Science and Technology 7 (1): 61–65. https://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-KMLS200701014.htm

- Wang, W. 2015. “An Exploration of Patterns in the Practice of Education for Sustainable Development in China: Experience and Reflection.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 03 (05): 64–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2015.35010.

- Wang-Kaeding, H. 2018. “What does Xi Jinping’s new phrase ‘ecological civilization’ mean”? The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2018/03/what-does-xi-jinpings-new-phrase-ecological-civilization-mean/

- Wong, A., F. Long, and S. Elankumaran. 2010. “Business Students’ Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility: The United States, China, and India.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 17 (5): 299–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.216.

- Weintraub, R. E. 2007. “Neoclassical economics”. The Concise Encyclopaedia of Economics. https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc1/NeoclassicalEconomics.html

- Wu, B., and Y. Zheng. 2008. “Expansion of Higher Education in China: Challenges and Implications.” Briefing Paper 36. Nottingham: University of Nottingham China Policy Institute. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/iaps/documents/cpi/briefings/briefing-36-china-higher-education-expansion.pdf.

- Xiong, H., D. Fu, C. Duan, C. Liu, X. Yang, and R. Wang. 2013. “Current Status of Green Curriculum in Higher Education of Mainland China.” Journal of Cleaner Production 61: 100–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.06.033.

- Yang, G., C. C. Lam, and N. Y. Wong. 2010. “Developing an Instrument for Identifying Secondary Teachers’ Beliefs about Education for Sustainable Development in China.” The Journal of Environmental Education 41 (4): 195–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960903479795.

- Yuan, X., and J. Zuo. 2013. “A Critical Assessment of the Higher Education for Sustainable Development from Students’ Perspectives: A Chinese Study.” Journal of Cleaner Production 48: 108–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.10.041.

- Zou, Y., W. Zhao, R. Mason, and M. Li. 2015. “Comparing Sustainable Universities between the United States and China: Cases of Indiana University and Tsinghua University.” Sustainability 7 (9): 11799–11817. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su70911799.

- Zhang, T. 2010. “From Environment to Sustainable Development: China’s Strategies for ESD in Basic Education.” International Review of Education 56 (2–3): 329–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9159-7.

- Zhao, W., and Y. Zou. 2015. “Green University Initiatives in China: A Case of Tsinghua University.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 16 (4): 491–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2014-0021.

- Zu, L. 2019. “Purpose-Driven Leadership for Sustainable Business: From the Perspective of Taoism.” International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 4 (1): 1–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-019-0041-z.