Abstract

The present study explores how school improvement in combination with a teacher professional development (TPD) project influenced the implementation of education for sustainable development (ESD) in five Swedish schools, when employing a whole school approach. Interviews were conducted with three teachers from each school. Shulman and Shulman’s four forms of capital for capacity building were used as a framework for the data analysis. The impact of the project on the schools’ pedagogical activities varied considerably between the schools. The transformative potential in ESD was realized to a greater extent in the schools characterized by high levels of moral capital – i.e. trust – than in the schools characterized by more individual and traditional ways of working. Three general conclusions concerning ESD implementation are drawn: 1) Prior to launching a whole school project for ESD, it is desirable to make an inventory of the capacity building capital at participating schools, and to identify contextual factors constituting external pressure on the building of capital. 2) The school improvement project and the TPD need to be locally adjusted to the available capital. 3) A strategy for adapting the project to the various external pressures needs to be developed.

1. Introduction

The gap between policy and practice regarding ESD has been recognized since decades (Goodlad Citation1997; Stevenson Citation2007). One way to bridge the gap is through Teacher Professional Development (TPD), but research has shown that the effects of TPD are often temporary (Desimone Citation2009). However, based on the whole school approach (Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp Citation2019), TPD is deemed an important precondition for school improvement. The characteristics of successful TPD for ESD are thus of particular interest, and a basic assumption is that TPD for ESD must include not only environmental and sustainability issues, but needs to highlight the conditions affecting the outcome of the teaching and learning process as well. In the present study, the perspective is broadened and a School Improvement project that included TPD was developed, in which all teachers and school leaders were engaged in a whole school approach, aiming at bridging the gap and developing transformative ESD practices. A whole school approach towards ESD is suggested to involve all stakeholders within a school: students, parents, teachers, school leaders, and to focus teaching on authentic problems in the wider society thereby transforming the school itself into an agent of change in a sustainable direction (Henderson and Tilbury Citation2004). The goals of transformative ESD are set as a) acquisition of responsible environmental behavior and b) active citizens’ participation (Eilam and Trop Citation2010). The theoretical framework of fostering communities of teachers as learners (Shulman and Shulman Citation2009) was applied in this study, along with Shulman’s conceptual scheme of capital for capacity building. The latter was used to describe how the different types of capital, i.e. curricular capital, moral capital, technical capital, and venture capital, developed and interrelated in the participating schools as they progressed in their school improvement process, from what Fullan (Citation2001) describes as the initiation phase toward implementation, and in the long run attaining the goal of institutionalization of ESD.

2. Background

For several decades, the international policy level has stipulated ”more education” when the issue of how to achieve sustainable development (SD) was raised. In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted 17 sustainable development goals (SDG) with the ambitious aim of ”transforming the world”, education being a key driver for achieving the goals. Hence, the concept of SD occurs frequently in curricula in the syllabi of different school subjects around the world. The UN has been pushing ESD as a key task for education worldwide for almost five decades (UN Citation1992; UNESCO-UNEP 1975; UNESCO Citation1978; Citation2004) and renewed attention to the ESD mission was induced after the launch of Agenda 2030 (UNESCO Citation2017). The ESD call is also present in the Swedish national curricula and syllabi issued by the Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket Citation2011, 2013). The curriculum for the nine-year compulsory school is goal-oriented, and one of the overall aims concerns sustainable development stating that schools are responsible for ensuring that each student, on completing compulsory school, “has obtained knowledge about the prerequisites for a good environment and sustainable development” (Skolverket Citation2011, 12). Further, sustainable development is explicitly addressed in different syllabi of many school subjects such as Biology, Chemistry, Civics, Crafts, Home and Consumer Studies, Geography and Religion.

However, evaluations show that work on sustainability issues is poorly developed in many Swedish schools and the answer as to which schools implement ESD systematically seems to be random (Boeve-de Pauw Citation2015; Gericke, Manni, and Stagell Citation2020; Naturskyddsföreningen Citation2014, Citation2018). There is also great uncertainty among teachers about the meaning of the concept of sustainable development (Borg et al. Citation2014). The examples illustrate a discrepancy between policy and practice regarding ESD. This policy-practice gap was noticed as early as the 1990s, and has been internationally debated ever since (Goodlad Citation1997; Stevenson Citation2007). In order to bridge the gap, the Swedish Government recently commissioned the Swedish National Agency for Education to highlight how the schools’ ESD documents and strategies link to the national goals and to the SDG in Agenda 2030 (SOU Citation2019, 13) and as a result, course material regarding ESD for in-service training of staff has recently been produced (Skolverket Citation2020).

Several Swedish municipalities have also launched TPD programs, aiming to improve ESD. Given the resources invested in implementation efforts and the complexity of ESD, we find it particularly important to evaluate the outcome of such TPD initiatives. A recent Swedish study identifies four main criteria characterizing successful implementation of ESD in schools: collaborative interaction and school development, studentcentred education, cooperation with local society, proactive leadership, and continuity (Mogren and Gericke 2017a, 2017b). However, most of the Swedish schools included in a further study experienced difficulties in attuning the school organization to the need to include the ESD perspective (Mogren and Gericke Citation2019). Hence, a project using a whole school approach was launched, in which TPD was aligned with the local school improvement process of facilitating ESD implementation, and these implementation processes are investigated in the present study.

3. Aim and research question

The aim of the study is to establish the influence of the ongoing school improvement process and TPD on the implementation of ESD and to identify contextual circumstances facilitating or hindering the implementation of ESD in terms of the theoretical framework on four forms of capital needed for capacity building (Shulman and Shulman Citation2009). The specific research question guiding the study is: How are different forms of capital for capacity building expressed when teachers talk about their school and the TPD program they participate in?

4. Theoretical framework

4.1. School improvement and Capital for capacity building

Research on school improvement focuses on strategies and processes that schools apply to improve teaching and student performance (Håkansson and Sundberg Citation2016). School improvement processes comprise different phases: initiation, implementation, and institutionalization (Fullan Citation2001). These processes take time, a short-term process lasting between 1 and 2 years, a medium term between 3 and 4 years, and a long term project continuing for 5 years or longer (Bellei et al. Citation2016). The combined TPD and school improvement project in focus in this article covered three years aiming for implementation and beginning the institutionalization phase of ESD. However, the data of this study were collected about one and a half year after the start of the project, i.e. half way through the project.

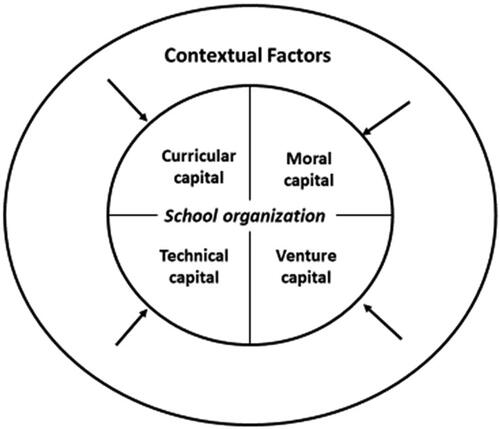

The present study focuses on how ESD can improve schools’ capacity to prepare students to cope with environmental, social, and economic challenges related to sustainable development, and is based on the view that different forms of social capital is a useful metaphor for capacity building in schools – as societal institutions (A. Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012; Shulman and Shulman Citation2009). Capital in social and educational contexts refers to a quality or an asset that can be exchanged for any desirable educational condition or a desired change in the school. Drawing on Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1970) and Putnam (Citation2001), D. H. Hargreaves (Citation2001) highlights the school’s potential role as an institution, producing social capital by inducing trust and norms of reciprocity between individuals. During the following decades, variations of the capital metaphor, i.e. human capital, decisional capital, and professional capital, have been suggested as key components of school improvement (Campbell, Lieberman, and Yashkina Citation2016; Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012; Jones and Harris Citation2014). The common denominator is that capital is always desirable for school improvement, and it can be accumulated as well as applied.

Besides the connotations of capital, a range of other key components in school improvement are presented in the literature. To varying degree, these concepts reflect the four forms of capital needed for schools’ capacity building, as suggested by Shulman and Shulman (Citation2009). Curricular capital relates to different aspects of knowledge that are important to achieve the intended school improvement. Moral capital is about wanting to change teaching in the direction of a shared vision. Technical capital relates to the doing, how theory and vision are transformed into the teacher’s teaching and venture capital is about daring the risk to reconsider previous forms of teaching and school organization. Thus, we find the capital model to be a comprehensive framework and a useful tool for identifying and analysing changes and progress in an ongoing TPD project. In the following section we show the relevance of the model by linking the four forms of capital to research on school improvement from recent decades.

4.1.1. Curricular capital

Curricular capital concerns subject-specific knowledge, but also systemic and policy-related knowledge both on the teachers’ level and on the schools’ organizational level. Newmann, King, and Youngs (Citation2000) highlight the need of not only focusing on the knowledge and skills of individual teachers but also to include the whole organizational capacity of the school, involving the professional community, program coherence, technical resources, and principal leadership. With such a whole school approach, teachers’ curricular knowledge is adapted to changes in the outer world and in the local context in order to enhance both cognitive and moral development among students (Hargreaves Citation2001). This approach also aligns with the dual aims of the Swedish Education Act, i.e. children and students shall ”obtain and develop knowledge and values” (SFS 2010:800, ch. 1 § 4).

As sustainable development includes ecological, social, and economic dimensions, we need complementary perspectives to enhance ESD. Starratt (Citation2007) expresses this by stressing that humans are involved in both the natural, the social and the cultural worlds. Curricular capital in the form of sustainability knowledge thus needs not only to be based on physical, but also on social and mental ontologies. According to Redman, Wiek, and Redman (Citation2018), sustainability education needs to focus more on procedural knowledge linked to action and less on subject-specific knowledge, in order to unleash the transformative potential. Hence, when sustainability is treated as a field that is less defined by the topics it addresses (resources, energy, water, food, education, etc.) than by the styles of thinking, knowledge, values, and attitudes it embraces (Redman, Wiek, and Redman Citation2018), it is obvious that the balance between knowledge and values cannot be neglected. Ethical considerations about what is desirable for sustainable development thus presuppose priorities between different values, which puts the moral capital in focus.

4.1.2. Moral capital

Shulman and Shulman (Citation2009) conclude that achievement of collegial learning requires moral capital in the form of a shared vision. A ”highly developed and articulated vision serves as a goal toward which teacher development is directed, as well as a standard against which one’s own and others’ thoughts and actions are evaluated” (Shulman and Shulman, 2). Visions are built on values and specific values associated with sustainable development are freedom, equality, solidarity, tolerance, and respect for nature (UN Citation2000). Starratt (Citation2005) adds that respect is the root principle behind many ethical ”don’ts”. Because we respect ourselves, other people, and the environment, we should not do X, Y and Z. But responsibility also emphasizes our positive obligations to care for each other. The responsibility ethic reminds us that it is not enough to avoid doing harm. We are obliged to do good (Starratt Citation2005, 6).

In line with Starratt, Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman (Citation2011) highlight the values of thinking and futures thinking as key components for guiding activities at all school levels in the desired sustainability direction. Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp (Citation2019) specify a holistic vision, shared by teachers and leaders and comprising both teaching activities and learning outcomes, as the core of the moral capital. Including such a shared value component in collaborative learning may act as a trigger for changing teaching practices, thereby ameliorating student learning (Avalos Citation2011; Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp Citation2019). However, the shared values first need to be identified, which recalls that before starting a school improvement project teachers must have a reasonably solid idea of what they want to do, that they trust each other and that there is a state of confidence among teachers as well as parents and administrators (Starratt Citation2005, 81-82). The interaction between these components determines the shape of the technical capital.

4.1.3. Technical capital

The technical capital relates to how teaching is carried out. How teachers engage in a complex pedagogical and organizational practice and transform a common vision into a “functioning, pragmatic, reality” (Shulman and Shulman Citation2009, 2). Thus, the technical capital aligns with the curricular capital and the moral capital. The overarching challenge that Starratt (Citation2007) identifies is the obligation to connect the school’s learning agenda with the moral agenda of the whole generation of learners, both as individuals and as a human community of ”us”. Teachers often miss that connection because they regard the school’s learning agenda ”as an end in itself, rather than as a means for the moral and intellectual ‘filling out’ of learners as human beings” (Starratt Citation2007, 167). To overcome this, it is vital that the TPD program encourages a shift from problem - to solution-oriented learning, facilitating hope and being an agency for change among the students (Boone Citation2015; Hicks and Holden Citation2007; Ojala Citation2012). This means replacing the technical capital of outdated instructor-centred programs with active-learning approaches combining real world experiences and reflections (Brundiers and Wiek Citation2011; Freeman et al. Citation2014; Redman Citation2013). In this way, teaching can also support the students’ need to generate the four kinds of meaning that Starratt (Citation2003, 161) discerns as essential: personal, public, applied and academic meaning.

Research on the relationship between what teachers learn in local TPD and how they consequently change their instructional practice, manifests the importance of instructional program coherence, a common framework for curriculum, instruction, assessment, and learning climate (Newmann, King, and Youngs Citation2000). A clear focus on such coherence may bridge the differences between how individual teachers apply the outcome of TPD in their respective subjects.

4.1.4. Venture capital

Venture capital nourishes teachers’ dedication to their mission and commitment to the vision. Teachers involved in a TPD for ESD therefore need to be motivated to learn before they will fully immerse themselves in learning activities (Power and Goodnough Citation2019, 2). A conceived mismatch between one’s vision and one’s performance can function as a trigger to learn or – if too great – can discourage learning and replace hope with despair (Hammerness et al. Citation2005). Conclusively, any analysis of school improvement requires the inclusion of internal and external factors that may influence the intended outcome (Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp Citation2019). How teachers reflect on the background, the process, and the outcome of their TPD for ESD is consequently of central interest. Shulman and Shulman (Citation2009) stress the centrality of regular and structured occasions for metacognitive reflection among teachers to help them become more conscious of their disposition, including their sources of venture capital, and to develop their interpersonal competence, the ability to work well in teams and with a range of stakeholders (Brundiers and Wiek Citation2011).

4.2. Teacher professional development in ESD

Redman, Wiek, and Redman (Citation2018) summarize design principles for realization of the transformative potential in TPD for ESD. To begin with, they find it important to target key competencies in sustainability, such as curricular capital regarding systems thinking, futures thinking, values thinking, strategic thinking, and venture capital in the form of interpersonal competence. This is, according to Timperley (Citation2008), necessary in order to develop an understanding deep enough to meet the complex demands of teaching when practices based on traditions are being reconsidered. It is also important to ensure that TPD activities do not become rare exceptions to the ordinary activities at school. Other researchers (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2009; Popova, Evans, and Arancibia Citation2016) underscore the importance of long-term duration with frequent contacts, maintaining the growth of venture capital. Redman, Wiek, and Redman (Citation2018) highlight that teachers need time to convert their new ideas into practice.

Using Shulman and Shulman (Citation2009) four types of capital as theoretical framework, allows for identifying common aspects of school improvement theories, formulated with other key concepts. As shown in , Shulman and Shulman’s four categories of capital for capacity building are consistent with a) the criteria of transformative TPD programs for sustainability education according to Redman, Wiek, and Redman (Citation2018), b) the ESD whole school approach (Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp Citation2019) and c) an ethical school (Starratt Citation2005). Likewise, this comparative meta-analysis provides a satisfactory validation of Shulman and Shulmans’ (Citation2009) theoretical framework, which justifies its general usefulness. The present study focuses on the framework of the four forms of capital, as it relates to the teaching practices rather than suggests specific desired outcomes, thus consistent with the analytical research design of thematic analysis employed in the study.

Table 1. A comparison between Shulman and Shulmans’ theoretical framework of four capitals (2009) with the frameworks of: continuous TPD for sustainability (Redman, Wiek, and Redman Citation2018); Whole school approaches (Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp Citation2019) and an ethical school (Starratt Citation2007).

5. Material and method

5.1. The Swedish school system

Grades 1-9 (age 7-16) are compulsory in Swedish schools. They are regulated by a national curriculum, which is the same for all schools. Grades 10-12, (age 17-19) upper secondary education, are voluntary, but completed by nearly all students. Upper secondary school is organized in nationally regulated academic or vocational programs, either preparing students for tertiary education or for an occupation.

5.2. The case

In 2016, a midsized town in Sweden launched a school improvement program aiming at developing ESD. The initiative stemmed from a need to improve teaching and learning on environmental and sustainability issues, the ambition being to improve the overall quality by adopting a whole school approach. The schools therefore needed “to increase the capacities of educators and trainers to more effectively deliver ESD”, the wording of the UNESCO. (Citation2014, 15) global action plan for ESD. The municipal school authorities invited schools to partakein a three-year combined school improvement and TPD program using a whole school approach for ESD. The underlying aim was to institutionalize ESD through a school improvement process by engaging all the stakeholders, i.e. teachers, students, school leaders, school board and other staff. The TPD part of the project consisted of teachers collaborative work, also including seminars with external experts that should support “bottom-up” initiated processes, aiming at strengthening interdisciplinary teaching and learning in order to improve students’ knowledge about SD-related issues and also their well-being. Five schools joined the project. illustrates the large differences between the five schools, in terms of student population, level of education and the local context. In each school, the entire school team participated, i.e. all teachers, school leaders, and other staff.

Table 2. Description of the participating schools.

Two school developers with more than ten years of teaching experience at other schools in the municipality, and actively conducting ESD research (not authors of this article), served as the project management team and were employed by the municipality to implement the project. They were, in other words, neither teachers at any of the schools in the implementation project, nor involved in the data collection or data analysis of our study. Before the project started, the school developers had, in a pilot study, mapped improvement areas in each school by interviewing teachers and school leaders with the aim to identify local needs and to find out to what extent the schools fulfilled UNESCO’s components of a quality ESD: participatory decision-making, applicability, variety of methods, local relevance, critical thinking, and interdisciplinary work.

Two of the schools were particularly keen on participating in the project: the primary school (# 3) and the residential area school (# 2). In the primary school, the initiative to partake in the project was initiated by the teachers from a bottom-up perspective, with support from the principal. In the residential area school (# 2), it was the other way around, an eager principal with support from parts of the staff. In the upper secondary (# 5), the rural (# 4), and the multicultural school (# 1), participation was rather a result of “top-down” management, based on agreements between the school leaders and the municipal school authority.

The joint project of school improvement and TPD ran for slightly less than three years, and included six collective seminars (once each semester) for all staff members at all schools. In these TPD seminars, external teachers and specialists engaged in scaffolding ESD learning experiences for the teachers from the five schools. The external teachers came from other universities, school agencies, NGOs from Sweden and Norway, and were recognized authorities on these issues. The first seminar introduced the teachers to the concepts of SD and ESD, including the three dimensional model of SD and the various aspects of teaching approaches in ESD, as outlined in the present paper. The second seminar built further on the theoretical framework of ESD, addressing the question of why teaching ESD is important, while the third seminar focused on choice of content and competencies required for ESD. The fourth seminar offered varying examples of ESD initiatives, and focused on cross-curricular collaborations as an approach for implementation. The last two seminars were conducted after the present study was completed. Between the collective seminars, the teachers introduced ESD into their regular teaching, with the aid of the school improvement process at their schools, which is described in the following paragraphs.

In order to engage the teachers in commencing ESD in the local school improvement process, one teacher at each school was appointed as facilitator of the bottom-up approach, with 20% of working hours allocated for this duty.

On a monthly basis, each school organized local meetings with the teachers at the school, led by the facilitators at the respective schools (nine meetings each year). The meetings were meant to be incentives for driving the ESD implementation from a bottom-up perspective, and were founded on local needs that had been identified and discussed among the teachers.

As the whole school approach was applied to the project of implementing ESD, additional measures were taken to involve all stake holders in the school (school board, school leaders, teachers, and students) during the process (Henderson and Tilbury Citation2004). To this end, supplementary meetings between project management and school management, and between project management and school facilitators respectively, were arranged three to four times each semester. The meetings involving school management addressed possible institutional obstacles to the ESD implementation, and the meetings involving the facilitators aimed at supporting them in their work to encourage their fellow teachers in their efforts to implement ESD locally.

5.3. Data collection

Three teachers from each school were interviewed, i.e. in total 15 interviews were conducted. At each school, one of the interviewed teachers acted as facilitator, i.e. the link between the school and the research team, all of them sharing the responsibility to plan and coordinate the TPD project locally at their school. The facilitator informed his/her colleagues about the interview request, and the first two colleagues showing interest were scheduled for interview. All interviews were conducted during five weeks during the third semester, after 19 of the planned 36 months of the project.

The interviews followed a semi-structured manuscript (Kvale and Brinkman Citation2009) with broad opening questions and more specified follow-up questions. Eleven women and four men were interviewed, all but one with more than ten years of experience as teacher. Their median age was approximately 50 years. Each interview lasted 35-50 min and was recorded with a voice recorder. All interviews were transcribed word by word by a professional transcriber, each interview generating 15-20 pages plain text for the analysis.

The interviews were divided into three main sections. The first section concerned the local school context, i.e. characteristics of the school culture, including relations between colleagues, and relations to students and their parents. The second section dealt with teachers’ experience of and opinion about previously implemented school improvement projects, while the third section investigated teachers’ views and experiences of the ongoing TPD project.

The analysis encompassed all three sections, as teachers’ experiences from the past often affected how they related to the ongoing project. For the purposes of the analysis, it was hence not meaningful to delimit the three sections; they were considered an intertwined foundation for reflective interpretation.

5.4. Analysis

The analysis was thematic (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) and comprised three stages: coding, thematization, and reflexive interpretation. In each analytical stage, the computer software NVivo 11 was used to organize the data into coding categories and themes. The coding resulted in excerpts, representing the most meaningful interview statements regarding the four forms of capital for capacity building as presented in the taxonomy, i.e. curricular capital, moral capital, technical capital, and venture capital (Shulman and Shulman Citation2009). In this stage, the approach was deductively derived from the theoretical framework, aiming to search and categorize utterances representing each form of capital. In the next stage, the reading inductively focused on finding salient themes in each of the four coding categories. These themes are presented in the results as sub-categories to the four forms of capital. Finally, the excerpts were interpreted from a reflexive-pragmatic approach (Alvesson Citation2011) with the ambition to consider the subject from different angles, avoiding anticipating a certain perspective. The excerpts included in the article were selected in accordance with representativeness.

5.5. Limitation of the study

As the interviews were conducted with teachers that showed an interest in being interviewed, there might be a risk of selection bias. However, a willingness to be interviewed regarding an ongoing TPD does not in itself indicate belonging to either the most enthusiastic or the most critical group. Rather, our impression is that the interviewees represented a category united by a desire to share both positive and negative reflections and it is thus difficult to judge the direction of possible selection bias.

6. Results

The results include excerpts from the interviewed teachers’ responses, followed by a number and letter identification. The numbers 1-5 after each excerpt refer to the school in question, and the letters a, b, and c refer to one of the three interviewees at each school. The main results are also summarized in .

Table 3. Summary of indicative results. Themes within each category are bolded, illustrative excerpts are italicized.

6.1. Curricular capital – to know

This domain refers to teachers’ knowledge related to ESD and how this could be aligned with the curriculum and with strategies and policies relevant to the TPD project. Specific knowledge about the students and their context was also included in this category. The two most obvious themes were knowledge about the 17 SDG, often referred to as the global goals by the teachers, and a dominating focus on content rather than on aims and skills. It was furthermore evident that the ongoing project had generated learning opportunities, ensued from reflecting on their own and colleagues’ teaching.

6.1.1. Global goals

The SDGs are by far the most common reference in teachers’ comments on how to execute the TPD-project. All five schools related their planning of ESD teaching activities to any or many of the 17 Global Goals. Particularly in the upper secondary school, this seemed to be the model for implementing ESD. In the beginning of a new semester, teachers strived to identify how they could connect one or more of the global goals to their modules and work areas during the school year. Each classroom is wallpapered with the global goals (5 b). A common way was to tie a specific issue to one of the Global Goals. When we worked with water the other day, we touched on the global goal to ensure access to water and sanitation for all (4 b). The teacher regarded the connecting of various issues to the global goals as an inspiring and easily accessible method for implementing ESD.

6.1.2. Focus on content

According to the Swedish Education Act (SFS 2010:800, ch. 1 § 4), the overarching aim of education is that students shall “acquire and develop knowledge and values”. Fundamental values and overall goals, including environmental, international, and ethical perspectives, are presented in the first and second sections of the general Swedish national curriculum, while syllabuses for each subject are presented separately (Skolverket Citation2011, 2013). Each syllabus is divided into aims and abilities, core content, and knowledge requirements for grades A-E. An overall impression of the five participating schools was that when teachers linked the TPD project to the steering documents, referring to knowledge rather than values, and to core content rather than aims and abilities. This content from civics […] it is very clear in this syllabus what content we have to teach (1c). Justifying bridges between global goals and school subjects was a matter of aligning the goals with the content in each subject. Then we have checked our core content and knowledge requirements (2c). When teachers collaboratively planned how to incorporate aspects of sustainability in courses in the upper secondary school, they look very closely at the core content, so you don’t work transdisciplinary very often (4a).

6.1.3. Learning opportunities

Although it was hard to identify a clear vision and a shared direction in the project, most teachers perceived themselves as part of a learning organization, and that the project had fuelled learning opportunities. However, local traditions in the schools appeared to have great impact as well. In the residential area school, the interviewees conveyed that teachers were not used to jointly reflecting on their teaching. No, [I] have never done that (2 b). Collegial reflection was more common in the other schools, and the TPD project seemed to reinforce an already ongoing exchange of ideas between teachers. We are used to discuss pedagogical issues … now we reflect on such issues even more (4a). In the multicultural school, where the initial focus of the TPD project was on improving students’ language skills, the teachers’ awareness of the importance of mother tongue had strengthened substantially: … so now everybody in this school knows what research says about the importance of mother tongue, and they didn’t know that when the project started (1a). The primary school introduced the use of two teachers in each class. This twin-teacher system generated a multitude of occasions for self-reflection and learning on a daily basis. Previously you were alone; maybe you could speak with colleagues, but they didn’t know what had happened in the classroom and … it’s harder to help someone when you don’t share the experience (3c).

6.2. Moral capital – to want

The moral capital facilitated teachers’ engagement in collaborative work in two of the schools, and was based on a shared vision put into operation, permeating the organization. However, the analysis also revealed a predominant uncertainty in three of the schools about what a vision in the TPD project actually entails. I don’t think everyone has a real grasp of what this will be (1c). None of the teachers expressed a clear vision of ESD being shared by all teachers in the school and with real impact on lesson planning and school organization. In the rural school, the project had so far not been noticeably integrated into the organization: We are part of the project, but it really hasn’t got any place in the organization, if you understand; things happen but not coordinated (4c). One partial exception was the multicultural school, where the facilitator ran the project as a language development project because the students’ linguistic level needed to be raised before the environmental and societal intentions of the TPD project could be implemented.

The lack of a shared vision in the three schools means that the currency of moral capital was indeterminate. The process had no distinct direction; something, unclear what, was waiting for implementation. Notwithstanding, there was no negative attitude or rejection to the idea of a vision for ESD. There were rather various circumstances that prevented and limited a vision from becoming operational. A recurring justification was that change takes time. … it’s on its way. It is about a changed mindset on what education should be … and that takes time (3 b). The intended change was thus postponed rather than a contemporary ongoing process. Futures thinking was also absent in teacher talk: I don’t know anything about what it (the TPD project) will mean next year (5 b). This doesn’t mean that there was a general lack of moral capital in the schools, but – speaking metaphorically – the moral capital was not invested in the ESD account. Thus, it is vital to identify the characteristics of present moral capital as it may generate a spill over, energizing the TPD program.

The two themes appearing in the material from two schools were pedagogical consensus and supportive principals.

6.2.1. Pedagogical consensus

Moral capital thrives through consistent application of an agreed pedagogical structure, including routines and a shared approach to teaching and learning. This was noticeable in schools 1 and 3, when highlighting the necessity of strict routines and shared methods: We are very accustomed to our pedagogy, how we should work; it is very different from other schools (1c). The teacher justified the strict structure with reference to the students’ various linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Another sign of moral capital in the multicultural school was the shared view that the demands placed on individual teachers were greater than one individual could cope with, and consequently they were all prepared to support each other. It’s okay to say” Help! What a troublesome lesson I had! […] It’s okay to relieve the pressure (1a). A teacher in school 3 expressed similar thoughts: We had to support each other very much over the years; sometimes too little staff and difficult conditions. I would say that the will to collaborate is deeply rooted in the school (3c). This school was furthermore characterized by an ambition to raise the level of internal conversation to a level that developed the teaching and learning activities: We do not get stuck in controversies like different ways of thinking, and I believe and hope that everyone feels that we are supporting each other (3 b).

Although not yet established as a noticeable/significant part of teaching and learning, a relatively positive attitude to TPD was noticed: We are in this project for two years now, and I think it happens more often than before (1c). In the remaining schools, the attitude to TPD was more cautious or questioning and the teachers seemed to work more individually, withoutinsights into their colleagues’ doings. The teachers here knew little about what was going on in classrooms other than their own. No, I have never done that, seen another teacher teach (2 b). Beside pedagogical consensus in schools 1 and 3, the role of the principals in building moral capital was also a distinguishable theme.

6.2.2. Supportive principals

Teachers from the two schools with pedagogical consensus gave examples of support from principals. In the primary school, the principal acted as a game changer: She turned the whole boat, and attained a positive change throughout the school (3c) and We have been listened to (3 b). In the multicultural school, a new principal rather had the role as manager of an uncontested commitment with a guarantee of continuity: It takes time for her (the new principal) to adjust to how such a school works (1 b). The rural school did not show such an independent attitude toward the principal. Now, we’ve got a new principal, and we don’t yet know what she wants, where we are heading (4a). In schools 2, 4 and 5, the principals’ roles were less obvious, and teachers desired more active control from the principal: I want the principal to make plans for PD days when we can discuss forms of interdisciplinary collaboration (2a). This was symptomatic, as the overall view/vision of the TPD program was more obscure in these schools. It was particularly evident in the upper secondary school, where the teachers did not see the principal as the main source of moral capital for the implementation of the TPD project: But then, I can’t put words on what kind of strategy there is […] I hope they know what strategy they (the principals) have (5a).

6.3. Technical capital – to do

Technical capital relates to what teachers actually do when they transform their vision (moral, venture, and curricular capital) of environmental and sustainability issues into teaching activities in a practical setting. When characterizing teaching, we distinguished between a) traditional academic subject teaching, conducted by individual teachers within the frame of a specific subject, b) multidisciplinary teaching, where several teachers collaborate on a specific theme, c) multidimensional teaching that introduces different scales for time and space, and d) emotional teaching that engages students emotionally (Eilam and Trop Citation2010). The analysis revealed that in practice, science teachers and teachers with multidisciplinary competence most often combined education in SD with teaching in single subjects. During limited periods of time, however, there were ambitious examples of multidisciplinary teaching conducted as theme works, while only few examples of multidimensional and emotional teaching were observed.

6.3.1. Single subject teaching

We don’t work multidisciplinarily very often (4a) is a statement from a teacher in the rural school that holds true also for the residential school. An explicit explanation was based on the conviction that single subject teaching is more time efficient: You run your own race. Everything goes so fast; the wheels are just spinning so you can’t (collaborate) (4 b). Science teachers connecting their subjects with SD issues is no surprise. Statements in that direction were formulated with self-evident emphasis: I mean, in my subjects, SD is a knowledge-based goal, as in biology and chemistry. I mean, it’s about environmental protection and biodiversity and all that … in my subjects, it has been natural all the time (1c). However, other teachers were also linking their subjects to sustainability issues. In home economics: But this year we work with health and equality, so in my subject [home economics] it has been quite easy (2c) and in handicraft, where sustainability issues were applied to thrift in terms of materials, such as not choosing wood from rainforests. In the upper secondary school, it was even more accentuated; teachers individually planned and inserted ESD moments into their ordinary teaching. Utilizing the SDGs had been an organizing principle and a tool for teachers’ planning of subjects where SD is not as established as in science subjects: Since the guidelines are that we should integrate SD into our courses, it was quite appropriate to use these 17 global goals as a starting point. It makes it easier to find out how SD can be visible in any subject (5 b).

6.3.2. Multidisciplinary and thematic teaching

Thematic teaching during a limited period in collaboration between teachers of different subjects was a common way to implement ESD in three of the compulsory schools, while the upper secondary school gave priority to ESD in single subjects. The main organizing principle among the upper secondary school teachers was based on shared knowledge and interests in each single subject. However, an alternative multidisciplinary principle was emerging: … a small group that I’m joining, we are interested in how to work multidisciplinary in a structured way […] it’s an idea for the future […] haven’t made any changes in the business yet … (5a). While multidisciplinary collaboration rarely occurred in the upper secondary school, it was occasionally arranged in the compulsory schools. One of the themes appearing in the residential area school was food: …sports and home economics cooked food in the forest, in maths they calculated food prices, in mother tongue they wrote debate articles on food habits, and in science they learned about the digestion process (2c).

A desire for more multidisciplinary project work was obvious but restricted by a perceived lack of time: The principal wants, we also want, but we think the time is short (2c). Another aspect of the contradiction between ambition and outcome was expressed by the same teacher: It’s double-edged … first an intense period of three weeks, like now we concentrate on it, then we drop it […] I think we should work like this all the time (2c). What qualifies the various multidisciplinary themes as related to SD is seldom stated explicitly but exists between the lines in statements like this from a teacher in the primary school: … relate more closely to the surrounding world … the students feel it’s for real (3a). A teacher in the rural school defined the desired learning outcome of ESD as being able to evaluate different things, thus becoming good at assessing, and being able to raise their voice in a good way (4c). That compelling formula was put into practice when students in grade two argued for a safer traffic solution in the vicinity of the school and convinced the local politicians to carry out the change.

6.3.3. Multidimensional and emotional teaching

Historical and future dimensions were not prominent when teachers talked about their teaching in connection with SD. Nor were multiple levels of scale. An exception was noted in the primary school and its theme children in the world. The theme included multiple scales, i.e. children’s conditions locally, a comparison with other countries, and globally. Moreover, a historical dimension, regarding childhood in Sweden one hundred years ago, was included at the rural school. Another multidimensional project was presented by the same teacher, called ”The green gold”, about forests in Sweden and in the world, today and in the past. What made that project memorable was a tangible example on emotional learning: … they had to sit quite still and quiet, pick out a tree and look, listen, and smell, thus using all their senses […] it worked and the children found it really exciting (4a). Otherwise, emotional teaching was largely missing.

6.4. Venture capital – to dare

Individual motivation and strong personal commitment are essential when working for a common vision based on shared moral capital. There are many reasons why teachers adopt a new vision but whatever the main reason is, it needs to be combined with a reluctance to accept status quo (Shulman and Shulman Citation2009). The venture capital category refers to the embedded answers to questions such as where does the will to change come from? And why is a teacher willing to jeopardize the routine business as usual? The venture capital appearing in the interviews was most often linked to explicit aims of the TPD project, mainly global goals and climate change, but also to the well-being of the students. The themes emerging were needs of the students, inspiration from colleagues, and expectations from parents.

6.4.1. Needs of students

In the primary and the multicultural schools, a particularly strong engagement in the students’ entire life situation was momentous to the teachers. The mission to raise their well-being appeared to be of great import to teachers in these two schools. The students’ own experiences and daily digital contact with some of the world’s most conflict-struck areas, made the outside world constantly present in the corridors and classrooms: …when there is war somewhere, then we have direct insight from the kitchen table into how relatives are affected in other countries. … You live in the whole world when you have students from every corner of the world (1c). In the multicultural school, the TPD project revolved around the students’ need to develop their language skills. The language is the key; every teacher in this place feels the importance of that, every single one (1a). This teacher thought that a deep and genuine interest, and engagement in the students as persons, are prerequisites for building strong relations. This is linked to one of the purposes of the TPD project, i.e. increased well-being among the students.

6.4.2. Inspiration from colleagues

Inspiration from colleagues was most prominent in the primary and the multicultural schools. The pedagogical consensus shown in the moral capital in these two schools was an obvious source of inspiration in the daily work: I get very many ideas from what others do and share with me (3a). A shared humble insight that one needs support from one another to solve the challenges at work meant that taking part in others’ experiences was close at hand, as was reflecting on their own teaching: We are totally unpretentious, and we must be. Otherwise, we will not be able to handle such a situation, so I want to say that we are very good at learning from each other and sharing ideas with each other (1a).

6.4.3. Expectations from parents

In the two schools with many immigrants, the teachers expressed that they generally felt that the students’ parents had great trust and confidence in them, which they believed contributed to their own sense of devotion to the assignment: The vast majority of parents are very appreciative to work with … they are grateful for the job we do (3c). A teacher from the multicultural school confirmed: This is probably the areas where trust in the school is strongest (1a). In an unpretentious working environment, where colleagues readily give and receive support, gaining the confidence of the parents in combination with the trust of the students appeared to be decisive for the venture capital that the teachers conveyed. The relation to the parents was more sporadic and distant in the upper secondary school, because of age of the students but was still characterized by trust: There is a commitment in a positive way. An expectation that their children get a professional education; quite a few of the students have parents who studied here themselves (5a).

6.5. Summary of results

Curricular capital embraced a clear focus on how to link single subjects to the SDGs. Overall, it was more common to view SD as a single subject issue than as a multidisciplinary challenge. Moral capital emerged mainly as a) signs of pedagogical consensus regarding teachers’ challenges in the two schools with a great share of students with a mother tongue other than Swedish, and b) as facilitating conditions created by supportive principals. Venture capital, i.e. what motivates the teachers to dare and to struggle, was found in a) teachers’ social commitment to the students, b) strong and continuous support from colleagues, and c) positive expectations from the students’ parents. This also characterized the technical capital, in practical teaching, see for a summary of the results.

A comparison between the schools showed that the multicultural and primary schools shared strong elements of moral capital in the form of collegial trust and collaboration, as well as principals that provided stability and continuity. The moral capital was here turned into an innovative and rather optimistic approach to TPD in ESD, with students’ needs and supportive colleagues as the richest sources of venture capital. The curricular capital was linked to research regarding the importance of mother tongue, but also to continuous collegial reflection based on experiences from teaching with two teachers in the same classroom. The residential area school displayed quite a casual laissez-faire attitude, including a rather vague departure from the principal’s standpoint. Teachers in the rural school conveyed a rather ambiguous picture with elements of emerging collaborative reflection on pedagogical issues related to the TPD, but also clear indications that the perceived stress prevented them from benefitting from the intentions of the TPD project. In the upper secondary school most teachers worked individually, aiming to complete their shares of ESD with a subject-specific connection to any of the SDG (see ).

7. Discussion

The findings indicate that the TPD at half-time had not yet brought about significant changes in teaching, nor collaboration between colleagues, except for thematic projects linked to SDG and an ambition to develop language teaching in one of the schools. An overall reason behind the weak impact may be that the emphasis in the TPD was primarily on information dissemination and organizational adaptation, while there seemed to be a deficit in teachers’ opportunities for reflexive exchange of doubts, convictions, and experiences regarding all aspects of sustainability and ESD. This signals that the participating schools had not undergone the recommended shift from the information-deficit model of education (Redman Citation2013) to a focus on action-promoting procedural knowledge. So, even though the TPD touched on the key-competencies in ESD (Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman Citation2011), these competencies seemed to have had only limited impact on the daily practice.

7.1. Curricular capital – business as usual

The curricular capital reported by the teachers was predominantly dominated by subject-specific knowledge, grounded on subject content. The key components, values thinking, and futures thinking, grounded on multidimensional and emotional teaching, were more or less absent. Thus, Starratt’s (Citation2007) call for knowledge on what it means to be a part of the social and cultural worlds and to generate different meanings (personal, public, applied and academic) seemed not to characterize the teaching more than sporadically. This implies that the transition from teaching sustainability by describing a range of problematic issues, to problematizing the styles of thinking, knowledge, values, and attitudes embraced, as recommended by Redman, Wiek, and Redman (Citation2018), was only partially implemented. The predominance of content learning at the expense of moral development may also be considered as hampering the fulfilment of the whole school approach, according to Starratt (Citation2005). The teachers more or less carried on business as usual, while adapting the new teaching in accordance with the TPD project, within existing frames.

The interviews did not support an interpretation of multidisciplinary teaching as a function of TPD. In the primary schools this might rather be explained by multiple subjects being taught there, and that primary school teachers generally are able to make plans for whole days. In the light of what Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman (Citation2011) specify as key competencies in sustainability, teachers in the multicultural and primary schools showed notable presence of interpersonal competence in terms of ability to initiate, facilitate, and support different types of collaboration, including teamwork and stakeholder engagement in sustainability issues. Systems thinking, values thinking, and futures thinking, as by Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman (Citation2011) advocate, were on the other hand basically absent in teachers’ utterances in all schools. We relate the strong content component in the curricular capital to the prediction of Newmann, King, and Youngs (Citation2000, 273): ”[It] is possible that future efforts to align curriculum and instruction more tightly with new state assessments may pose a threat to program coherence”. Such new state assessments were broadly implemented in the Swedish schools as a reaction to bad performance in PISA-tests 2010 and 2012. We conclude that after 2010, the national strong focus on PISA-assessment and subject specific grading, have had a much greater impact on the curricular capital than policy ambitions to develop ESD and may thus explain the prevailing focus on subject-specific content learning. Education turning into an international competition in terms of conducting ”business as usual”, rather than engaging in an emancipatory process aiming to fundamentally reconstruct society in a sustainable direction, would diminish the local scope for fundamental transformation. The influence of TPD on ESD is hence further affected by political and economic factors at the system level, in addition to the local factors centred on in the present study.

An implication is that a TPD for ESD needs to problematize how value content in the steering documents can be concretized and included in assessment. This would reduce the risk of ESD being perceived as a voluntary add-on activity.

7.2. Moral capital – the need to build trust

The results show that the moral capital created strong collegial relations, especially in schools 1 and 3. This was most clearly expressed in strong trust and a propensity to both give and receive support from colleagues. It is however difficult to determine to what extent this can be attributed to the TPD. The apparent lack of a common vision on ESD among the teachers, as a standard for evaluation of one’s own and others’ thoughts and actions (Shulman and Shulman Citation2009), suggests a weak influence from TPD regarding the moral capital. This conclusion is also supported by teachers’ frequent references to a long-standing collegiality as a source of their moral capital. Hence, metaphorically speaking – the moral capital was not always invested in the ESD account but related to other visions. Therefore, it is important to identify the characteristics of moral capital at a school when conducting school improvement and TPD projects as it may generate a spill over, energizing the vision of the project, in this case ESD implementation. The uncertainty about the vision also indicates that the moral capital is insufficient in reconsidering traditional teaching practices, which, according to Timperley (Citation2008), is required to release the transformative potential in ESD.

Reflection on shared values thus seems in need of being upgraded in the TPD, as it might function as a trigger among teachers involved in collaborative learning. However, the interviewed teachers overall expressed much fewer reflections on the values at stake in ESD than on content aspects. This might indicate a fundamental obstacle to improving the capacity of schools to really fulfil the whole school approach as this, according to Hargreaves (Citation2001), is a matter of both cognitive and moral/value development among students.

Trust was the most prominent value in the study and an important source of trust was the colleagues’ daily and spontaneous reflections on the most demanding elements of their work. This trust could function as the shared value component that may act as a trigger for changing teaching practices (Avalos Citation2011; Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp Citation2019). However, in school 1, with the richest moral capital, the energy of change was reserved for a language project that was largely driven by a dedicated facilitator. The absence of values thinking and futures thinking in the interview responses indicates that the TPD had so far not challenged the participants’ perceptions of these key components in ESD. This may indicate a too generous offer from the TPD organizers to the teachers to interpret the call for bottom-up perspectives entirely on the basis of local preferences. Being anxious not to control from the top, the TPD organizers left room for local teachers and facilitators with an articulated agenda, more or less related to sustainability, to shape the content. One way to avoid this would be to place the values in the foreground. For example, following Starratt (Citation2005), using the concept pair responsibility and respect for recurrent reflection on how these values can be operationalized in different educational settings.

7.3. Technical capital – the lack of instructional program coherence

Regarding technical capital, the research review identified two main challenges when transforming an educational vision including ethical values to a functioning reality in the classroom. First, following Starratt (Citation2005), it is important to view the schools’ learning agenda not as an end in itself but as a means for moral and intellectual growth. Second, it is necessary to achieve instructional program coherence (Newmann, King, and Youngs Citation2000; Mogren and Gericke Citation2019). The challenge here is to reconsider previous assumptions about how teaching should be conducted and changed accordingly in curricula, instructions, and assessments. Our empirical evidence suggests that the schools have so far avoided reconsideration and instead channelled the TPD outcome into limited thematic projects with little impact on the teaching between these projects, not aligning curriculum and assessment to instruction. An exception was the language development project in school 1.

The interviews also showed that the teachers had so far had insufficient time to transform their new sustainability knowledge into local practice as recommended by several authors (Brundiers and Wiek Citation2011; Freeman et al. Citation2014). Insufficient time for joint reflection and planning and project definition, not being explicit and uniformly comprehended at the local school level. explains this shortcoming in the implementation.

The dominance of subject-specific learning and the deficit of multidisciplinary, multidimensional and, in particular, emotional learning (Eilam and Trop Citation2010) suggests that Starratt’s (Citation2007) call to connect the school’s intellectual learning agenda with the students’ moral agenda and their true authentic selves, remains to be performed. The example from the rural school, on how to solve the problem of traffic dangers near the school, showed how the recommended shift from problem-centred to solution-oriented learning can be carried out in an authentic setting in the school’s vicinity. The key to bridging the gap between the problem and the solution seems to be to channel the emotions that the problem gives rise to among the students. In this case, the teacher used the technical capital to deal with the children’s outrage in the face of the value conflict between preserving trees and protecting children from traffic. This is a textbook example of how to create hope out of despair, as advocated by Boone (Citation2015), Hicks and Holden (Citation2007) and Ojala (Citation2012). The lack of more similar examples indicates a reluctance to change from traditional instructor-centred teaching to active learning and to combine real-world experiences and reflections as recommended by Freeman et al. (2014).

7.4. Venture capital – spending the savings on other ventures

The interviews revealed limitations in the venture capital when the TPD project started, and the tendency during the ongoing project was rather pending and reserved than enthusiastic. Lack of motivation prevents learners from being immersed in learning activities (Power and Goodnough Citation2019). If teachers are still eager to learn, it is only logical that they should compensate for the lack of sustainability motivation with motivation linked to other, more immediate aspects of teaching. They would use their savings of venture capital instead of making new. This is a plausible explanation of the strong engagement for the language development project in school 1. Such a strategy may also protect teachers from despair as a result of a perceived mismatch between the vision in the TPD-project and their own performance (Hammerness et al. Citation2005). It is safer to channel the energy and spend the venture capital on a well-known agenda than to run the risk of losing the capital on immature start up ideas. The sceptical attitudes to previous TPD projects, conveyed by some of the teachers, also provide a basis for such a strategy. A well performed language development project may also result in the development of interpersonal competence (Brundiers and Wiek Citation2011), but it will hardly compensate for the lack of structured occasions for metacognitive reflection that, according to Shulman and Shulman (Citation2009), are necessary to develop awareness of the teachers’ own sources of venture capital. However, the deep trust between colleagues, which was expressed in schools 1 and 3, shows that spontaneous reflection on a day-to-day basis can also generate strong venture capital. However, this would be a vulnerable model for school improvement because it rests on lasting relationships between interchangeable colleagues.

To summarize the discussion, a high level of moral capital appears to be crucial for establishing ESD as a whole school approach, i.e. trust between employees, and between employees and other school actors. If not present, this should be specifically attended to in the school improvement process. Further, the TPD program must be aligned and coherent with the instruction program at the participating schools, and if facilitators are used in the ESD implementation process, they need to be heavily supported and aligned with the routines and structures of the local instructional program.

8. Concluding discussion

The analysis of the four forms of capital revealed that the participating schools were far from reaching institutionalization of ESD. The school improvement process, including the TPD, had endured the initiation phase, and the first stages of the implementation phase were just under way. Although the time span of the project was rather short, less than two years, these results were discouraging, as the project (judged from the context description) was indeed very ambitious and well-organized, utilizing the whole school approach (Henderson and Tilbury Citation2004), and included all levels of the school organization. The TPD program accompanying the project, did not seem to further push it forward, in spite of facilitators integrating it into the school improvement process. Furthermore, the many interactions and exchanges of knowledge between the stakeholders in the project, along with the bottom-up approach, were expected to empower the participants, but apparently did not speed up the process. These findings raises the question of what lies behind this meagre outcome. What can be learned from this?

First of all, we need to recognize that the nature of a school is a very important factor for success in school improvement projects, and several of the participating schools had recognized a need for school improvement before entering the project. This might indicate prior existing problems in some of the project schools that could explain the identified problems in implementing ESD. Our theoretical framework disclosed that the curricular capital had grown during the project, but it was only partly exchanged for technical capital, i.e. transformative teaching. Instead, the results of the interviews show that teachers primarily continued their subject teaching (business as usual), merely adding thematic teaching to the repertoire, the reason being a lack of moral capital, that is, a common vision of what to accomplish. As a consequence, teachers lacking, to quote Starratt (Citation2005, 81), a ”reasonably solid idea of what they want to do”, might, as they unreflectively follow old habits, dutifully take part in the TPD workshops, without fundamentally reassessing the school’s mission. If teachers are predominantly accustomed to ”view the learning agenda of the school as an end in itself” (Starratt Citation2007, p, 167), rather than as a means for moral and intellectual growth of the learners as human beings, the teachers will continue to prioritize content learning about the physical world, not addressing the transformative aspects of multidimensional and emotional learning. Consequently, although some teachers in the project recognized the need to consider expectations from students and parents, the venture capital was in most schools not large enough to be exchanged for technical capital. Shulman and Shulman (Citation2009) framework of capital for capacity building has so far served well to describe the outcomes of the whole school project. Even so, the question why TPD in combination with the school improvement project did not yield sufficient capital to overcome the obstacles arising during the project, remains unanswered if only the schools’ internal capital at hand is addressed.

Based on our data, we could see that a plausible cause might be the contexts in which the participating schools were embedded, locally in the confined school context, but also in the wider, societal and national context, including the interrelationship between them. The context exerts an external pressure on the school organization at all levels. External pressure can be defined as different contextual or social changes outside the school’s mandate, yet needed to be taken into consideration by school stakeholders (Ball et al. Citation2011). For example, in the multicultural school, 80% of students were immigrants, with the language issue exerting a major external pressure on the moral capital (what was considered important and a shared value in that school), as well as the venture capital (what was possible to do). The external pressure was actually so strong at this school that the moral capital brought about a renegotiation (locally) of the project from ESD to language learning. In a second example, the external pressure of new grading systems and demand for assessment, largely ignored in the TPD for the ESD implementation, caused the ESD to be regarded as lying beyond the scope of the instructional program coherence. A third example is the rural school, in which the municipality before and during the project acted as external pressure by replacing the school leadership twice, making moral capital a deficit.

The analysis made it clear that the whole school project in the present study did not include a mechanism that could accommodate and account for the consequences of contextual external pressures in either a school improvement process or a TPD program. Three main conclusions were drawn from the study: 1) Before launching a whole school project for ESD, it is desirable to a) make an inventory of how the different types of capacity building capital appear at each specific school, and b) identify the contextual factors exerting external pressures on the building of different forms of capital. 2) The school improvement project and the TPD need to be locally adapted to the capital at hand in the participating schools. 3) A mechanism needs to be developed for the project in order to align it with the consequences of the external contextual pressures.

As can be deduced from these conclusions, Shulman and Shulman (Citation2009) conceptual scheme of capital for capacity building ought to be further developed to include contextual factors in the considerations. proposes a revised model for capital for capacity building, illustrating that contextual factors affect the different types of capital.

Figure 1. A model for capital building in schools, calling attention to the external pressure (see arrows) of contextual factors on the development of the different forms of capital.

In conclusion, capital building needs to be analysed before a school improvement process and TPD are initiated, in order to adapt the interventions in accordance with the capital at hand and to identify any capital in need of development. Furthermore, and of utmost importance, contextual factors possibly hindering the development of the lacking capital must be identified. During the implementation phase of developing capital for capacity, the school improvement process and the TPD ought to be developed in a manner that takes the contextual pressures on the school into consideration. In developing a whole school approach, great efforts were made to accommodate most suggestions found in the research on ESD implementation and TPD. Nonetheless, it appears that too little attention was paid to the contextual circumstances outside the schools’ direct influence, and these need to be examined by the school stakeholders. Further research on school improvement is much required, and it is recommended that future projects pay more attention to contextual circumstances.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (588.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Niklas Gericke

Niklas Gericke is Professor in Science Education, and Director of the SMEER (Science, Mathematics and Engineering Education Research) research Centre at Karlstad University in Sweden and visiting professor at NTNU in Trondheim, Norway. His main research interests are biology education and sustainability education from conceptual, teaching as well as implementation perspectives.

Tomas Torbjörnsson

Tomas Torbjörnsson, PhD, Senior Lecturer in Geography Education with a specialisation in Education for Sustainable Development. Department of Geography, Media and Communication, Karlstad University, Karlstad, Sweden.

References

- Alvesson, M. 2011. Intervjuer: Genomförande, tolkning och reflexivitet [Interviews: Performance, Interpretaion and Reflexivity]. Malmö: Liber.

- Avalos, B. 2011. “Teacher Professional Development in “Teaching and Teacher Education" over Ten Years.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (1): 10–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007.

- Ball, S. J., M. Maguire, A. Braun, and K. Hoskins. 2011. “Policy Actors: Doing Policy Work in Schools.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (4): 625–639. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2011.601565.

- Bellei, C., X. Vanni, J. P. Valenzuela, and D. Contreras. 2016. “School Improvement Trajectories: An Empirical Typology.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 27 (3): 275–292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2015.1083038.

- Boone, C. 2015. “On Hope and Agency in Sustainability: Lessons from Arizona State University.” Journal of Sustainability Education 10: 1–10. http://www.jsedimensions.org/wordpress/content/on-hope-and-agencyinsustainability-lessons-from-arizona-state-university_2015_11/.

- Borg, C., N. Gericke, H.-O. Höglund, and E. Bergman. 2014. “Subject- and Experience-Bound Differences in Teachers’ Conceptual Understanding of Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 20 (4): 526–551. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.833584.

- Bourdieu, P., and J. Passeron. 1970. La reproduction: Éléments pour une théorie du système d’enseignement [Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture]. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brundiers, K., and A. Wiek. 2011. “Educating Students Inreal-World Sustainability Research: Vsion and Implementation.” Innovative Higher Education 36 (2): 107–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-010-9161-9.

- Campbell, C.,. A. Lieberman, and A. Yashkina. 2016. “Developing Professional Capital in Policy and Practise: Ontario’s Teacher Learning and Leadreship Program.” Journal of Professional Capital and Community 1 (3): 219–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-03-2016-0004.

- Darling-Hammond, L., R. C. Wei, A. Andree, N. Richardson, and S. Orphanos. 2009. “State of the Profession: Study Measures Status of Professional Development.” Journal of Staff Development 30 (2): 42–67.

- Desimone, L. M. 2009. “Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures.” Educational Researcher 38 (3): 181–199. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140.

- Eilam, E., and T. Trop. 2010. “ESD Pedagogy: A Guide for the Perplexed.” The Journal of Environmental Education 42 (1): 43–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00958961003674665.

- Freeman, S., S. L. Eddy, M. McDonough, M. K. Smith, N. Okoroafor, H. Jordt, and M. P. Wenderoth. 2014. “Active Learning Increases Student Performance in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (23): 8410–8415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111.

- Fullan, M. 2001. The New Meaning of Educational Change. London: Routledge.

- Gericke, N., A. Manni, and U. Stagell. 2020. “The Green School Movement in Sweden – past, Present and Future.” In Green Schools Movements around the World: Stories of Impact on Education for Sustainable Development, edited by A. Gough, J. C. Lee, and E. P. K. Tsang, 309–332. Cham: Springer.

- Goodlad, J. 1997. In Praise of Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Håkansson, J., and D. Sundberg. 2016. Utmärkt skolutveckling: Forskning om skolförbättring och måluppfyllelse [Excellent School Development: Research on School Improvement and Goal Fulfillment]. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Hammerness, K., L. Darling-Hammond, J. Bransford, D. Berliner, M. Cochran-Smith, M. McDonald, and K. Zeichner. 2005. “How Teachers Learn and Develop.” In Preparing Teachers for a Changing World, edited by L. Darling Hammond and J. Bransford, 358–389. San Fransisco: Jossey Bass.

- Hargreaves, D. H. 2001. “A Capital Theory of School Effectiveness and Improvement.” British Educational Research Journal 27 (4): 487–503. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920120071489.

- Hargreaves, A., and M. Fullan. 2012. Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. New York: Teachers College Press and Ontario Principals’ Council.

- Hargreaves, A., and I. Goodson. 2006. “Educational Change over Time? The Sustainability and Nonsustainability of Three Decades of Secondary School Change and Continuity.” Educational Administration Quarterly 42 (1): 3–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X05277975.

- Henderson, K., and D. Tilbury. 2004. Whole-School Approaches to Sustainability: An International Review of Sustainable School Programs. Australian Research Institute in Education for Sustainability (ARIES) for The Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government. http://kpe-kardits.kar.sch.gr/Aiforia/international_review2.pdf

- Hicks, D., and C. Holden. 2007. “Remembering the Future: What Do Children Think?” Environmental Education Research 13 (4): 501–512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701581596.

- Jones, M., and A. Harris. 2014. “Principals Leading Successful Organisational Change: Buildning Social Capital through Disciplined Professional Collaboration.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 27 (3): 473–485. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-07-2013-0116.

- Kvale, S., and S. Brinkman. 2009. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun [The Qualitative Research Interview]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.